Автор: Rajput R. K.

Теги: engineering mechanics mechanical engineering katson books publisher mechanical measurements

Год: 2013

Текст

1.

1.1 .

, 1.2.

l.3 .

f.4 .

1.5 .

1.6 .

GENERAL CONCEPTS .......................... 1 -31

Introduc tion to M ea ure ment and

In ·trumentation ... .. ...... ... ...... ........ ..... .......... 1

1. 1. l . Mea uremem ... . .... ........ . .. . ............. .. 1

1. 1. 2 . In ~trumentation ... ...... .......... ...... ...... 3

Significance of Measurements ...... ....... ....... 3

Standard of Mea urement . .... ... ... .. ............. 3

S.I . Units and Conver ion factor . .. .. ........... 4

Mechanical Measuremen ts ...... .... ... ..... .. .... 13

Method of Mea urement ........ ... ... ...... ... ... 14

L7. Modes of Mea urement ........ .. .... ... .. .......... 15

1.8. Generalised Meas uremen t ystem a nd

its Functional Elements ...... ....... ..... ........... 16

1.9. Instruments ...... ... .. .. .. ... ... ..... .. .... .... ... ......... 19

1.9.1. Introduction .. ........ ... ...... .. ........ ..... 19

1.9 .2 . Classification o f i nstruments ....... . 19

1. 9 .3 . Factors relating to selection of

ins truments .... ...... ........................ 23

1.9.4. F un ctions of in struments ........ ...... 23

1.10. Input-out put Configurations of Measuring

Instruments and M easuring systems .......... 24

1.11 . Applications of Mea urement Systems ..... 26

Highlights ............... ................................ ... 27

O~jective Type Questions .......................... 28

Theoretical Questions ............................... 30

2. STATIC AND DYNAMIC

CHARACTERISTICS OF

INSTRUMENTS

............................

32-98

2.1. Introduction ........... ........ ...... .... ....... ...... ... .. 32

2.2. Definitions Relating to Measuring

Instruments ...... ... .. .. ... ......... ....... .... ............ 3 2

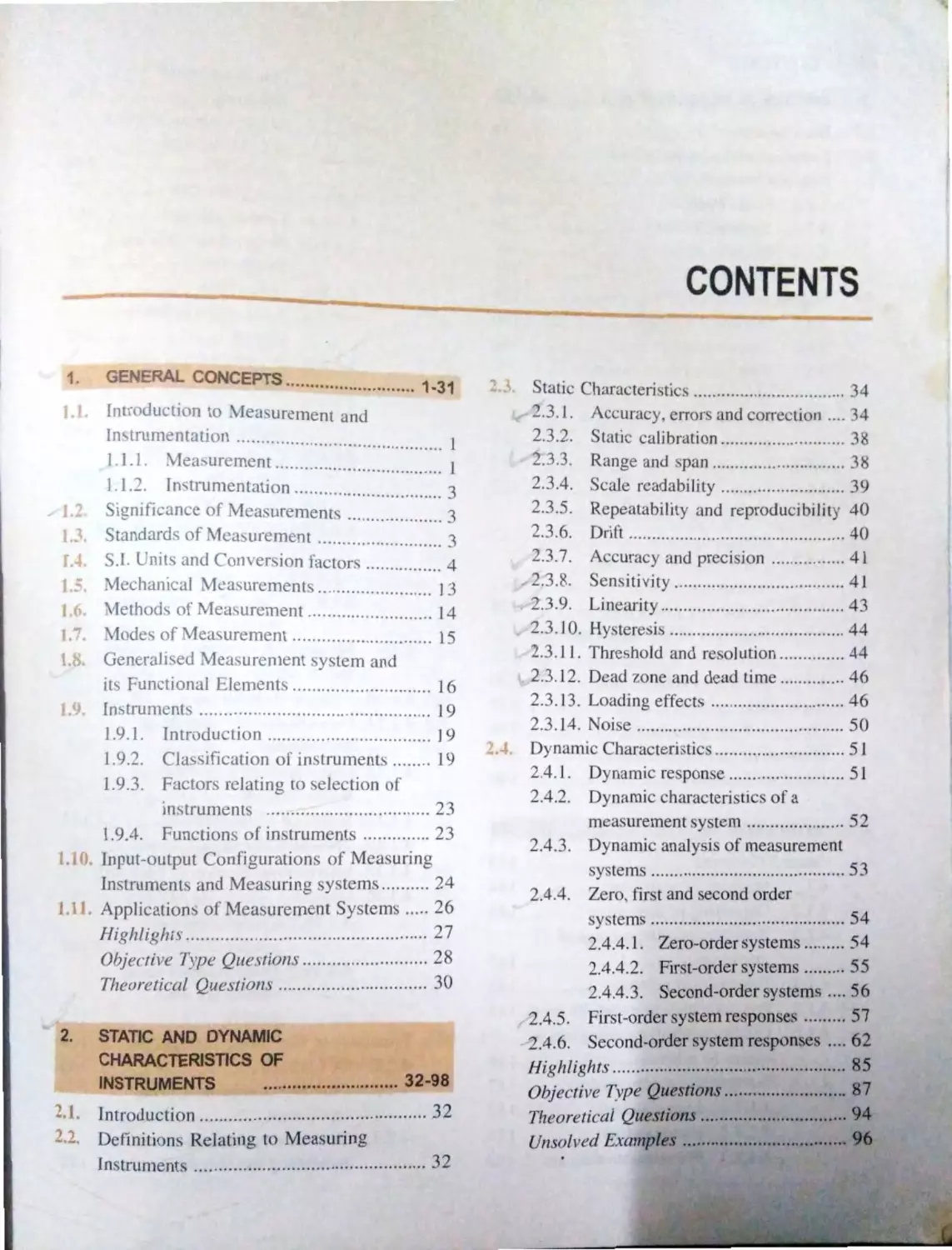

CONTENTS

.3 Static Characteri tics ... .. .... .................... .... 34

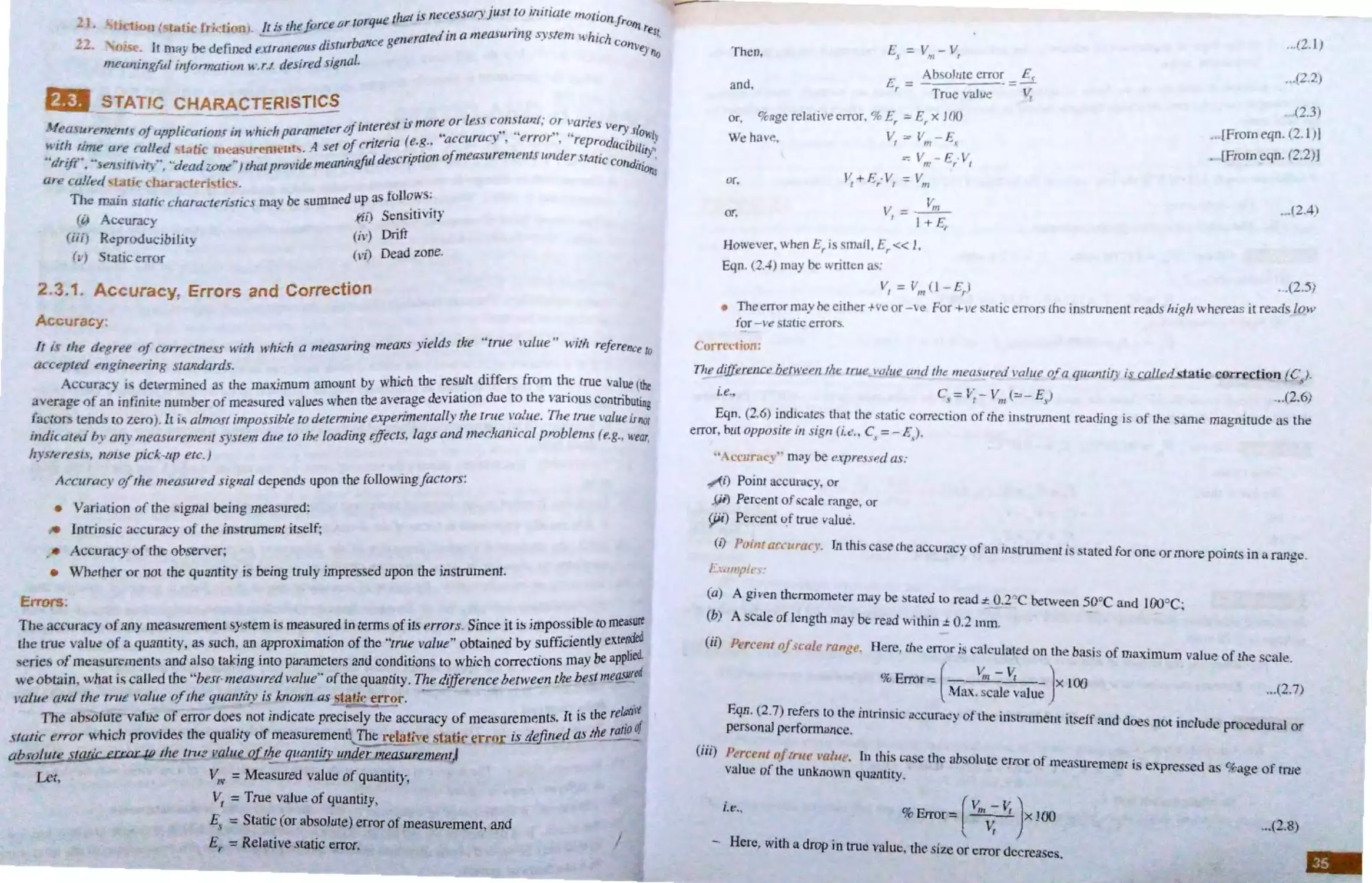

2.3.1. Accuracy, error and correction .... 34

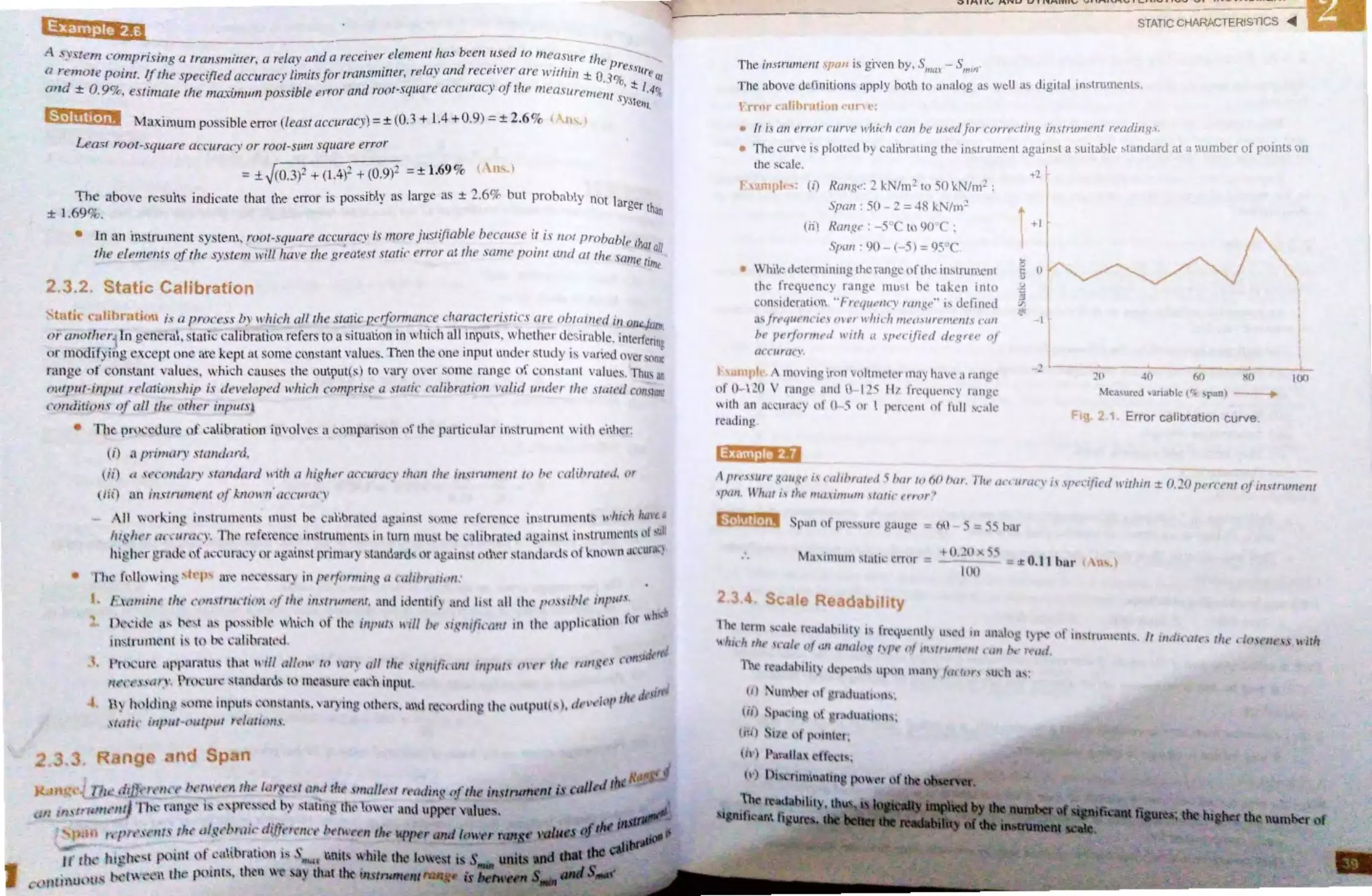

2.3.2. Static calibration ......................... .. 38

2.3.3. Range and span ............................. 38

2.3 .4. Scale readability ... ...... ................ .. 39

2.3.5. Repeatability and reproducibility 40

2.3 .6 . Drift ... .... .......... .... ...... ........... ......... 40

2.3.7. Accuracy and precision ................ 41

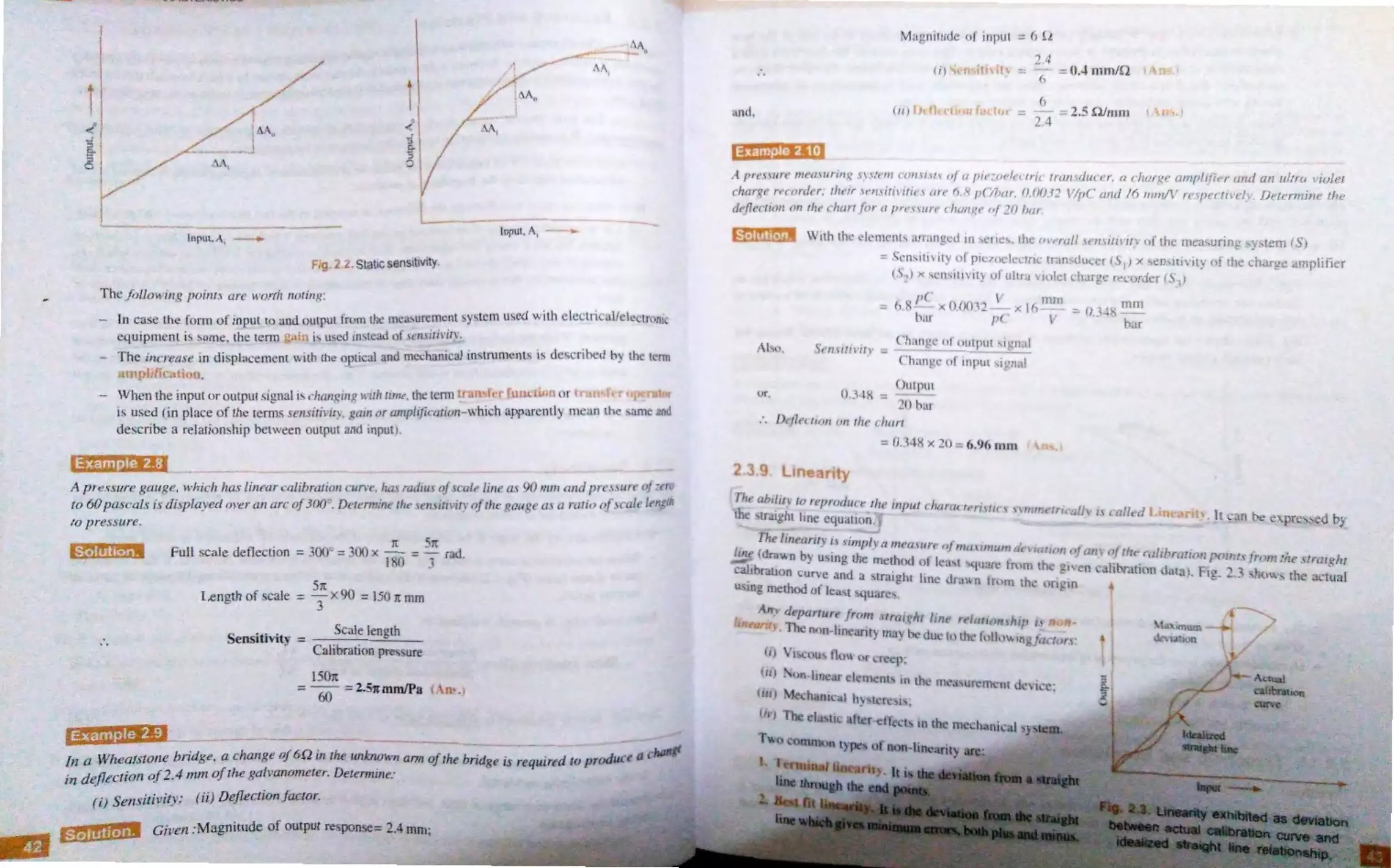

2.3 .8. Sensitivity ..................................... 41

2.3 .9. Linearity ........................ ........... .. ... 43

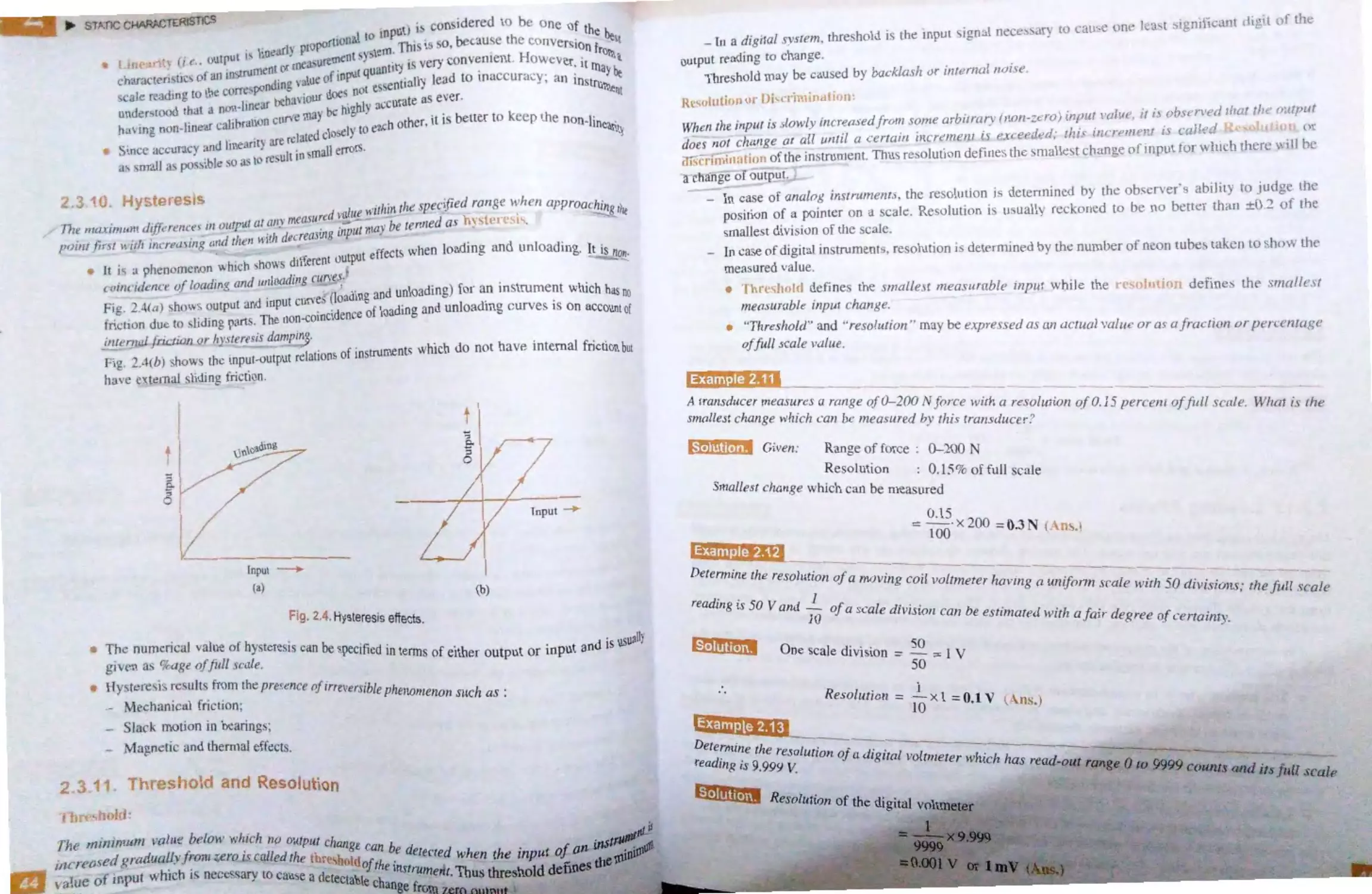

2 .3.10. Hysteresis ...................................... 44

2.3 .11 . Threshold and resolution .......... .... 44

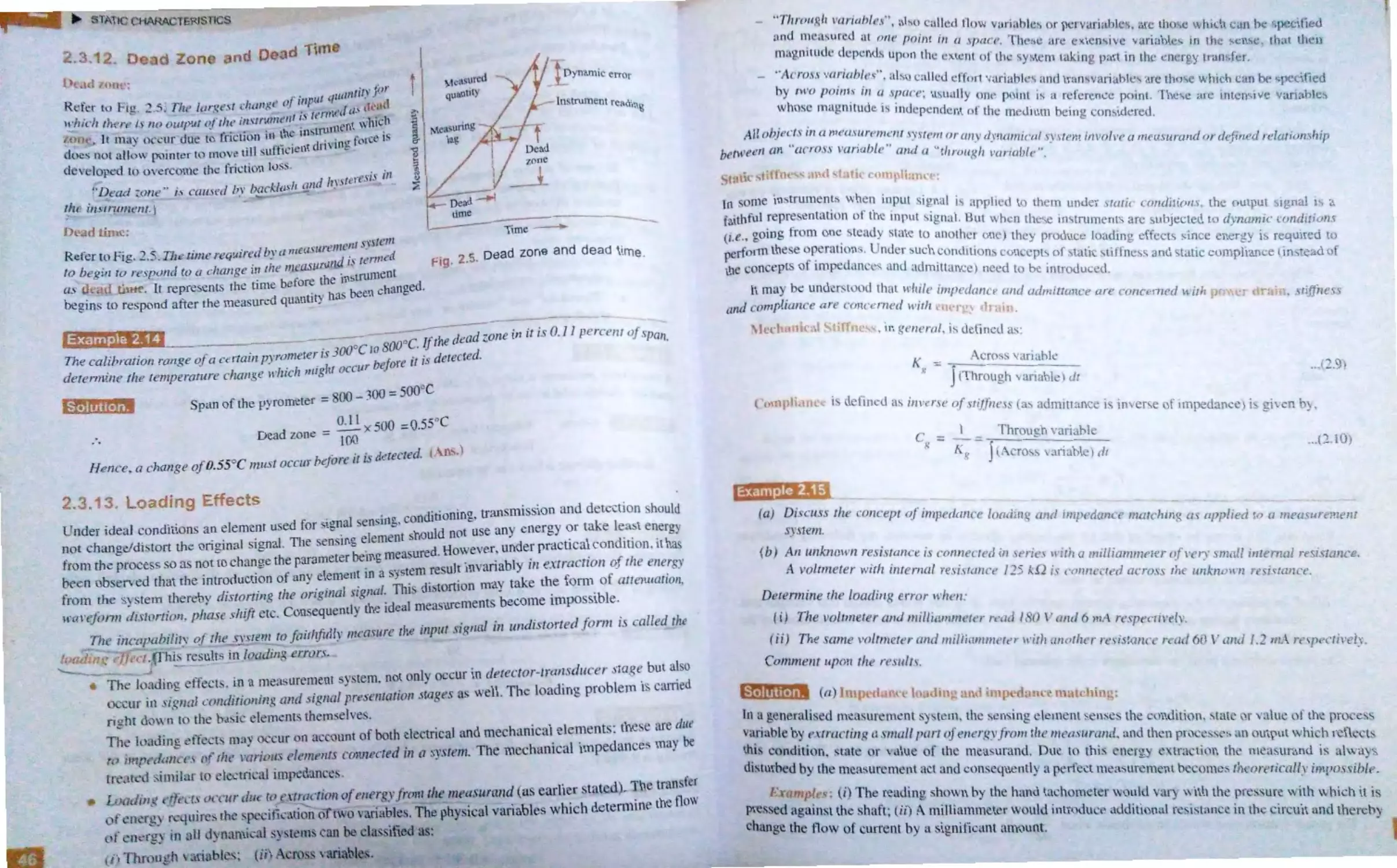

. , 2.3.12. Dead zone and dead time .............. 46

2.3.13. Loading effects .... ... .. ......... .... ..... .. 46

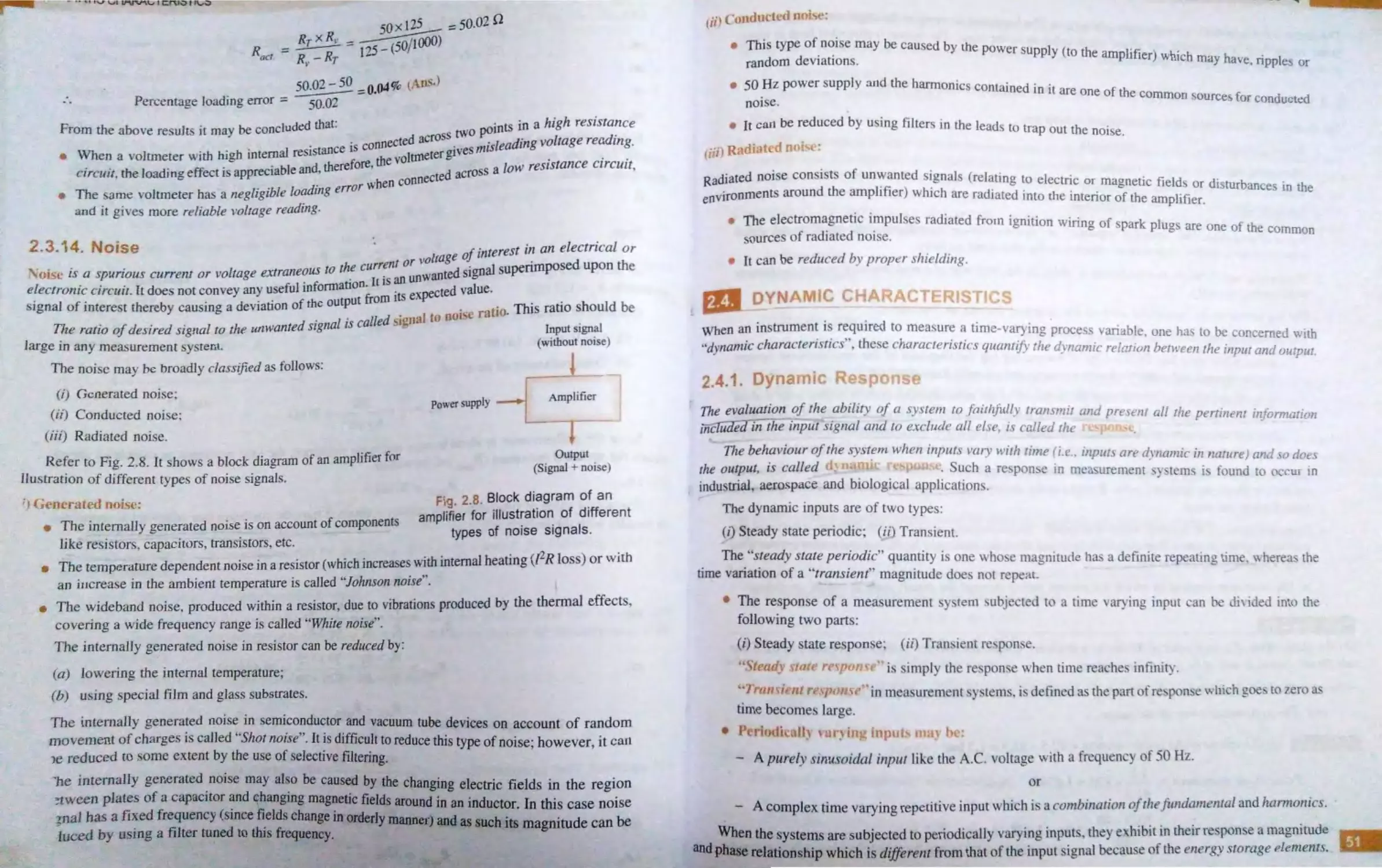

2.3 .14. Noise ..... ... .. ... ... ...... ............ ... .. .... .. 50

2.4 Dynamic Characteristics ........... ... .... ... ...... . 51

2.4.1. Dynamic re sponse ...................... ... 51

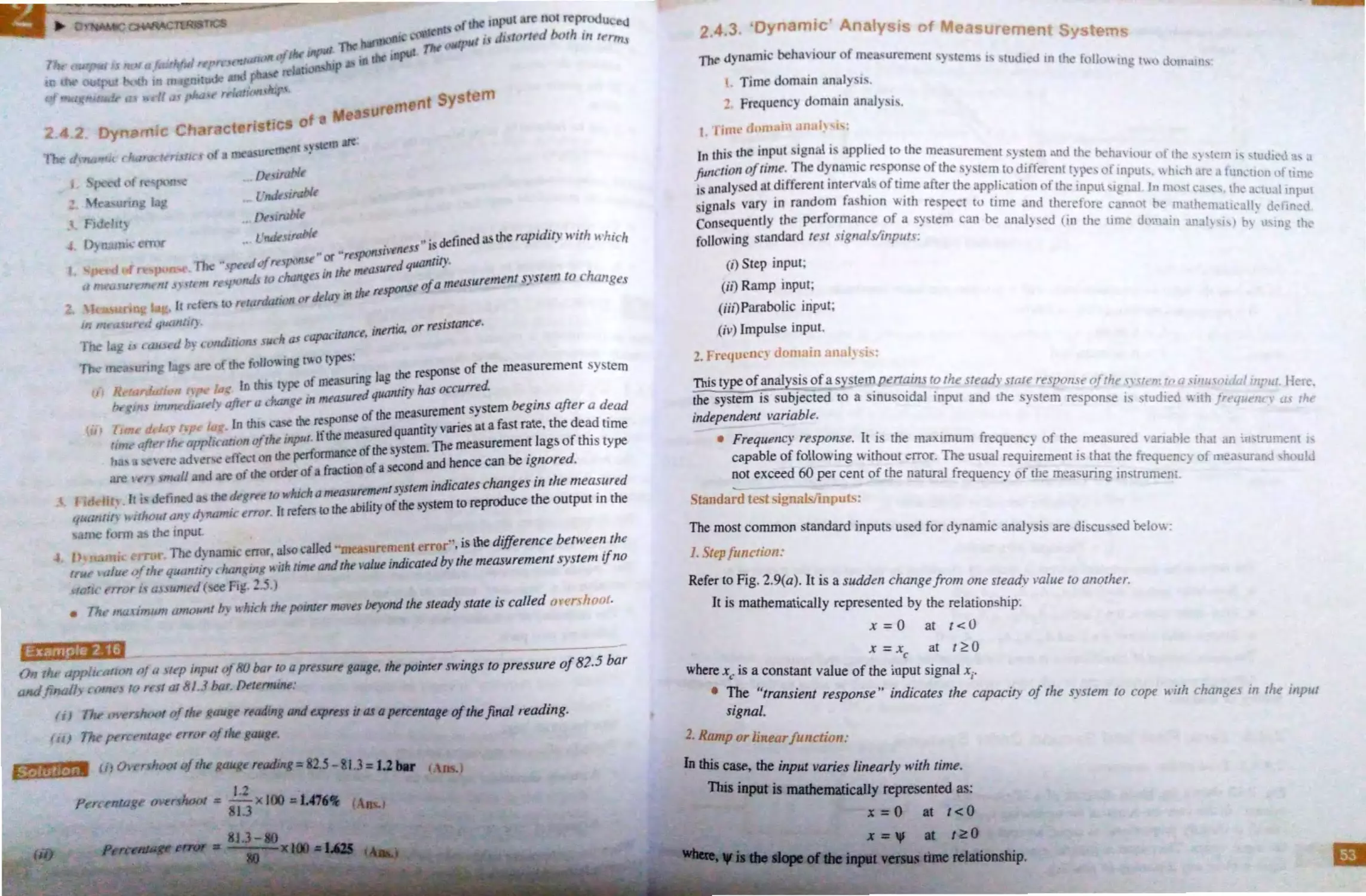

2.4.2. Dynamic characteristics of a

measurement system ..................... 52

2.4.3. Dynamic analysi of measurement

systems ...... .......... ........... .... ....... .... 53

2.4 .4 . Zero, first and second order

system ................. ......................... 54

2.4.4.1. Zero-order systems ......... 54

2.4.4.2. First-order systems ......... 55

2.4 .4 .3 . Second-order systems .... 56

,. 2 .4 .5 . First-order system responses ......... 57

-'2.4. 6 . Second-order system responses .... 62

Highlights .... .............................................. 85

Objective Type Questions .......................... 87

Theoretical Questions ............................... 94

Unsolved Examples ................... ............. 96

Vi CONTENTS

3.

.l

1..:..

-'· .

A.

4.

4.1 .

ERRORS IN MEASUREMENTS, ........ 99-142

Introduction ............................................... 99

Limiting (or Guarantee) Errors ......... ..... .... 99

Type. of E1rnrs ......................................... 105

3.3.1. Gros en-or ........................... .. ..... 106

.3 .2 . Sy. t matic error ...... ................... 106

3.3 .3. Random errors ............................. 107

Sources of Error ....................... ............... 108

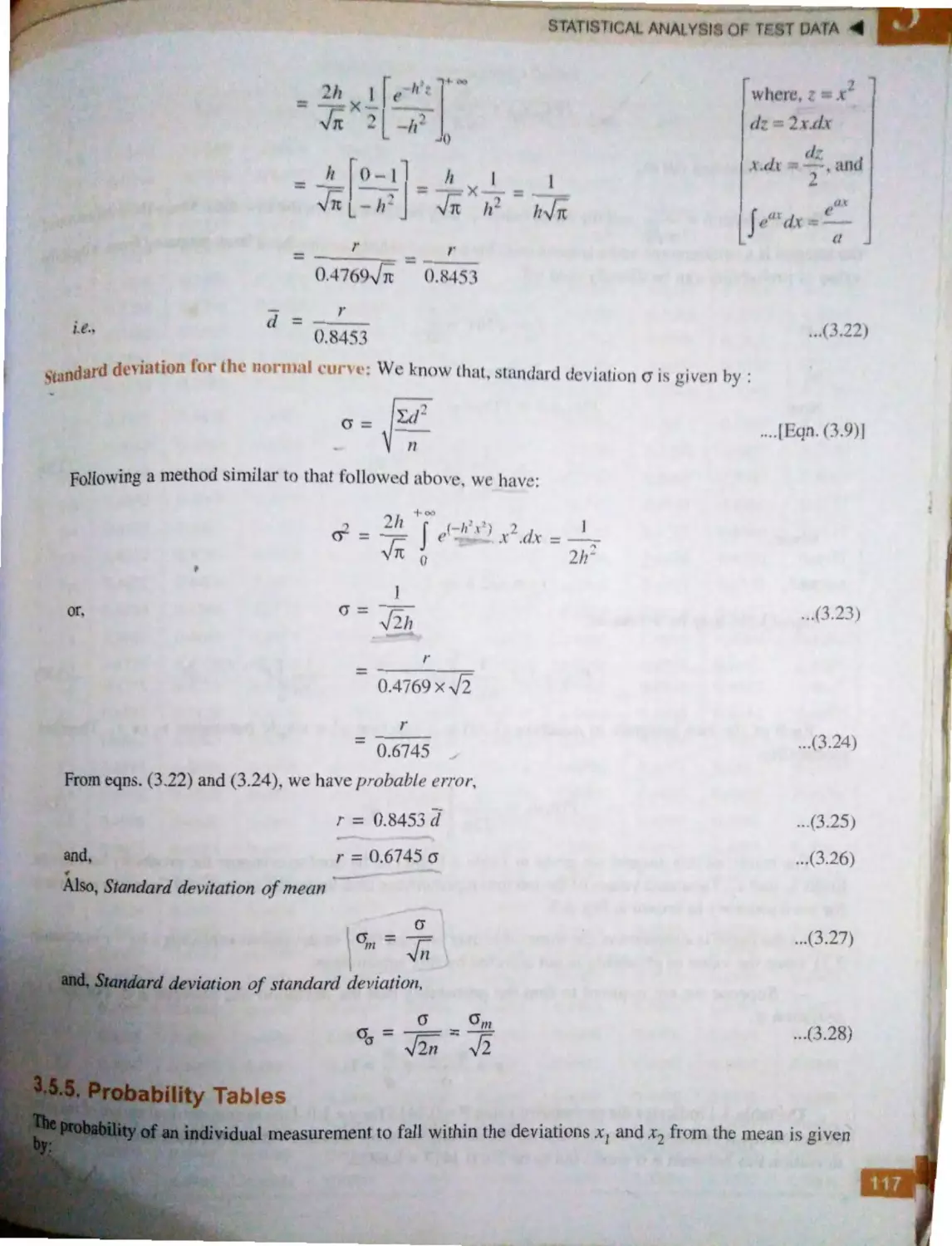

Statistical Analysi of Test Data ... ........... 108

3.5 .1. Statistical a erages ..................... 109

3.5 .2. Di persion from mean ................. 110

3.5 .3. Be t value from a sample

of reading ....... .................... ........ 111

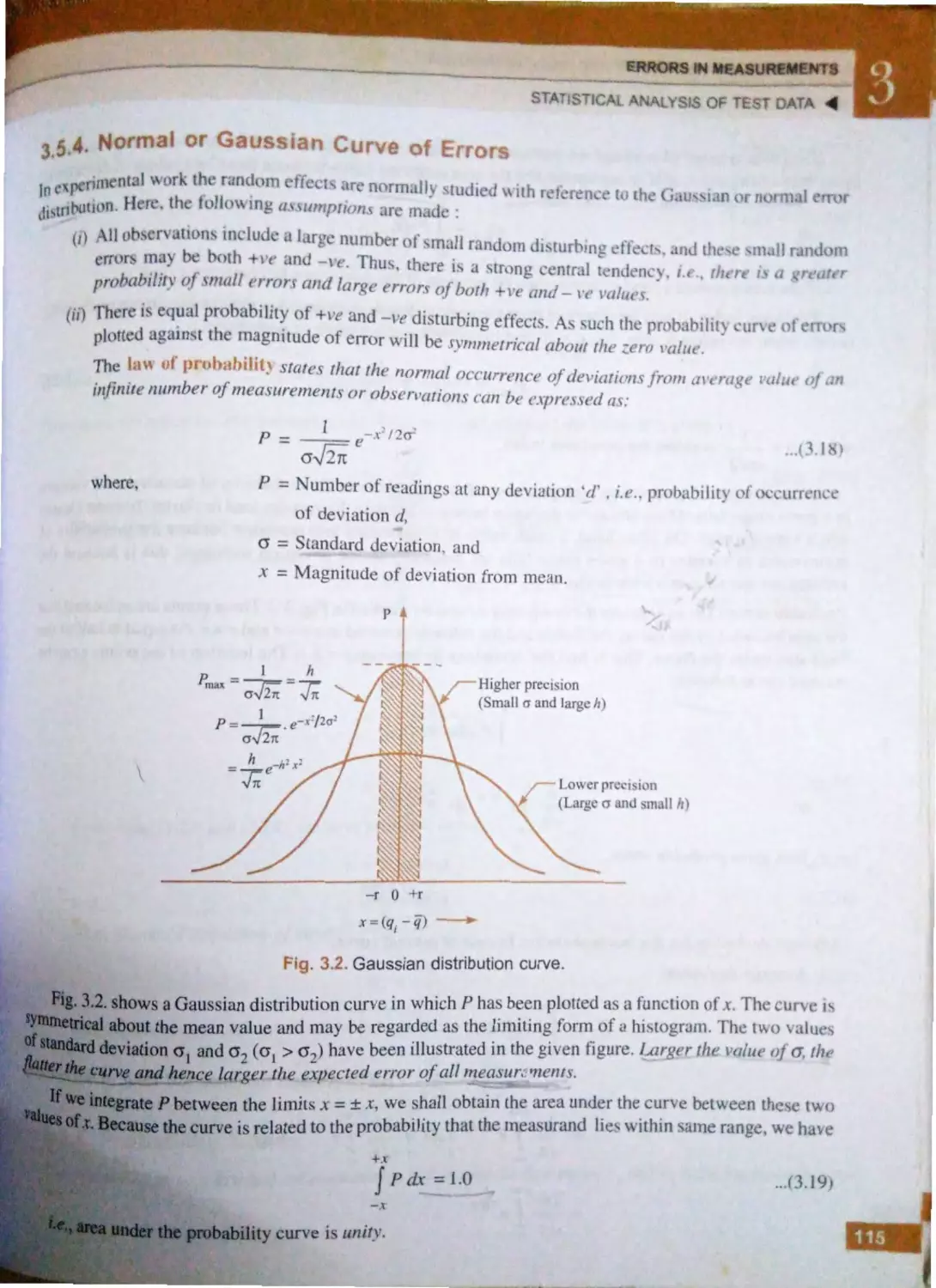

3.5 .4. Normal or Gau sian curve

of rrors .......... ............................. 115

3.5.5. Probability table ........................ 117

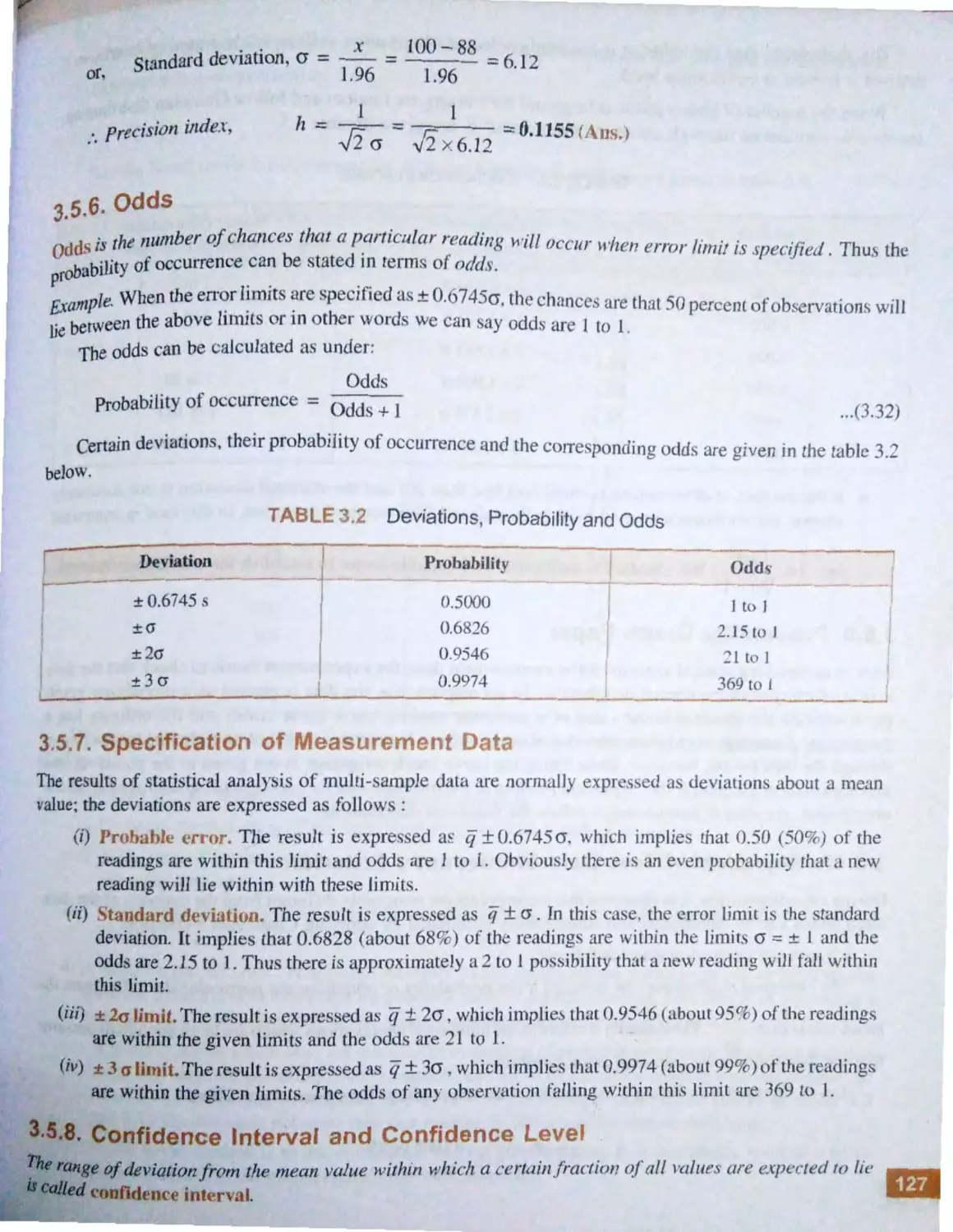

3.5 .6. Odds ............................................ 127

3.5.7. Specification of measurement

data .............................................. 127

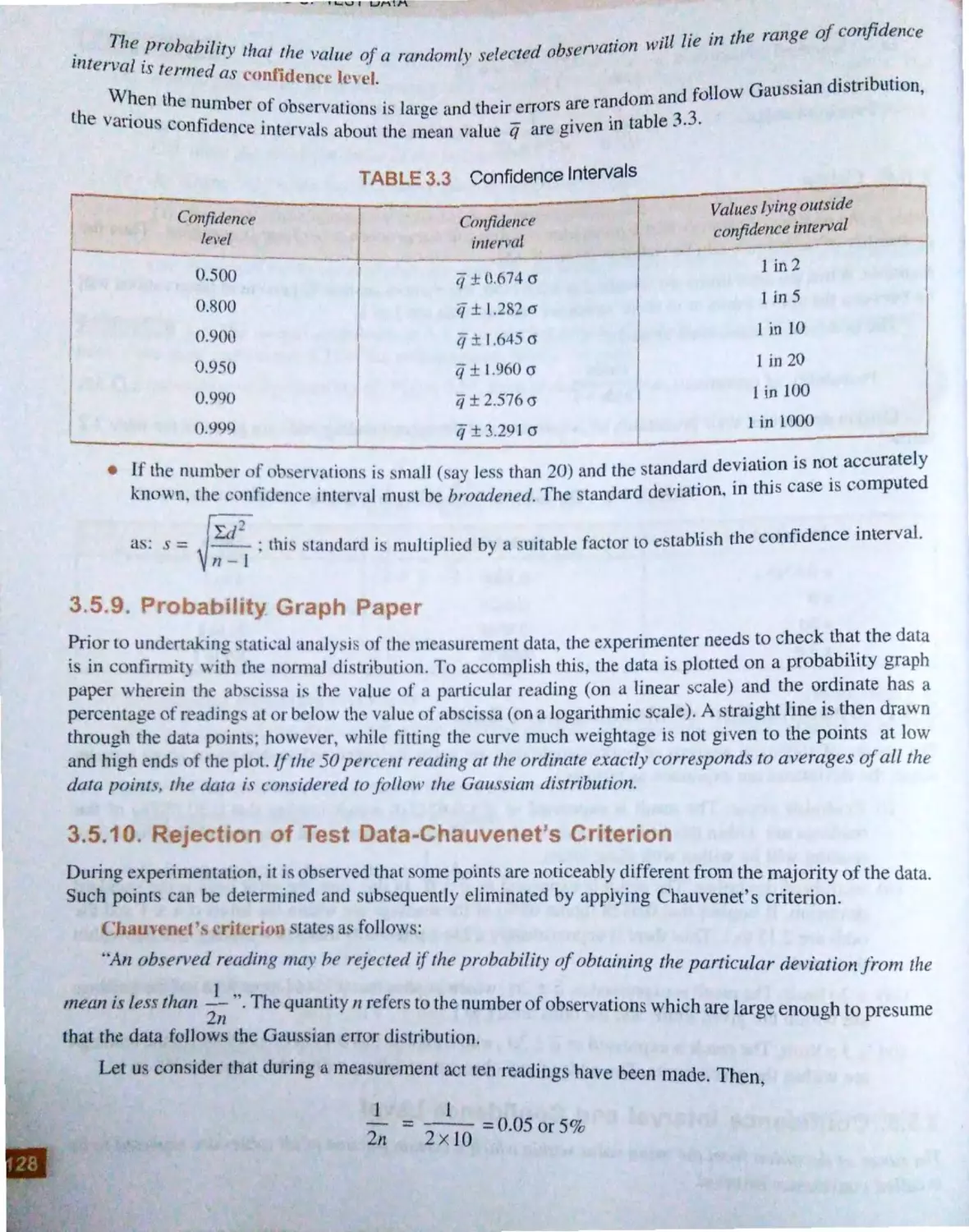

3.5.8. Confidence interval and

confidence level .......................... 127

3.5 .9 . Probability graph paper .............. 128

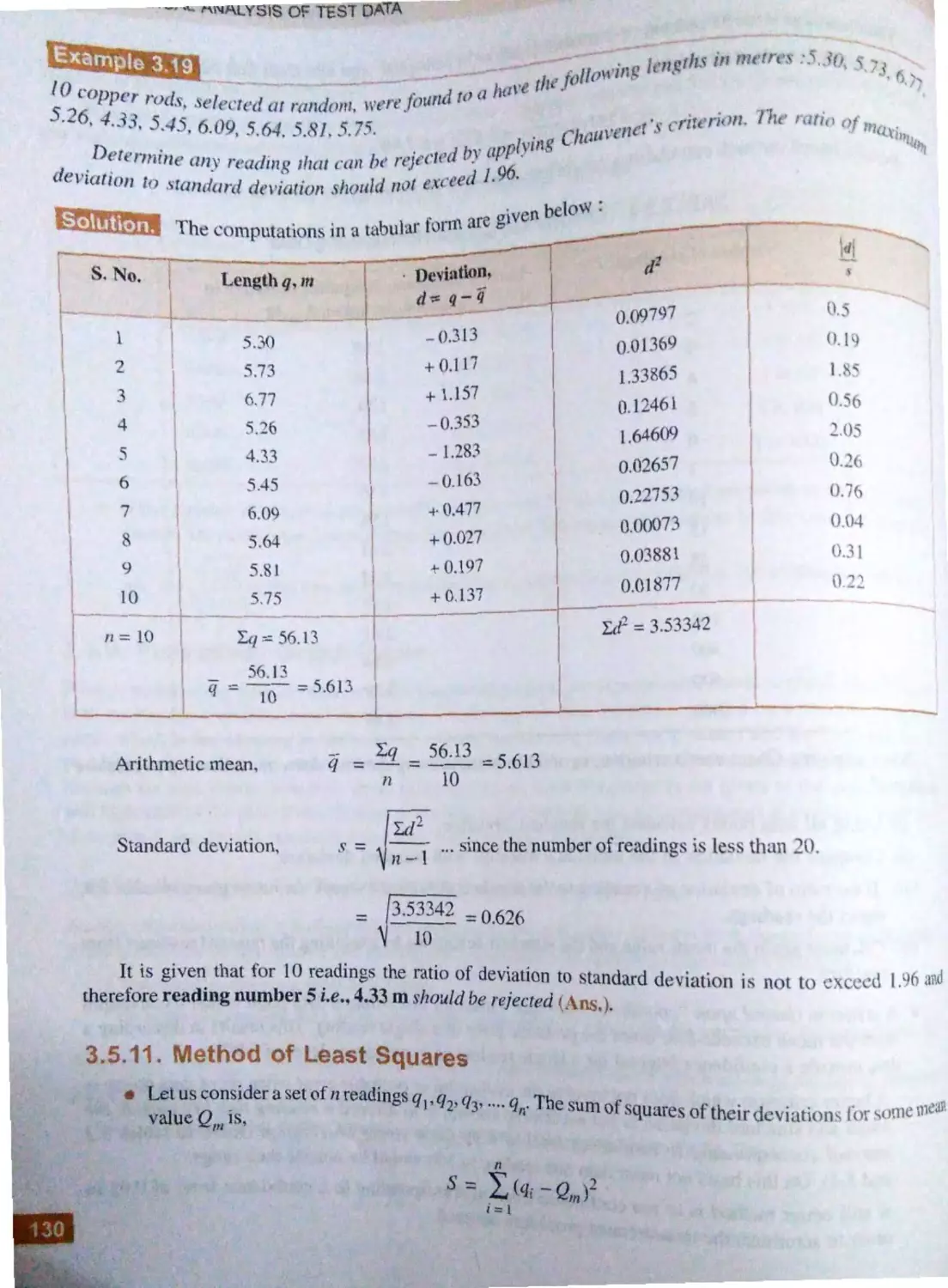

3.5.10. Rejection of test data-Chauvenet's

criterion ....................................... 128

3.5.11. Method of least squares .......... .... 130

Highlights ................................................ 135

Objective Type Questions ............. ......... .. 136

Theoretical Questions ............................. 139

Unsolved Examples ................................. 140

METROLOGY

.. .. ... ... ... ... .. ... ... 143-373

General Concepts .................................... 144

4.1 .1 . Meaning of metrology ........ ........ 144

4.1 .2 . Objectives of metrology ............. 144

4.1 .3 . Necessity and importance of

metrology .... .................... .. ........ .. 145

4.1.4. Dimensional accuracy ................. 145

4.1.5 . Precision measurement-Its need . 145

4.1 .6 . Quality control-metrology as a

means to achleve ......................... 146

4.1 .7 . Standards of measurements ..... .. .. 147

_4 .1.7 .1 . Line standard ................ 147

4.1 .7.2. End standard ................. 149

4.1.7 .3. Wavelength standard ... 150

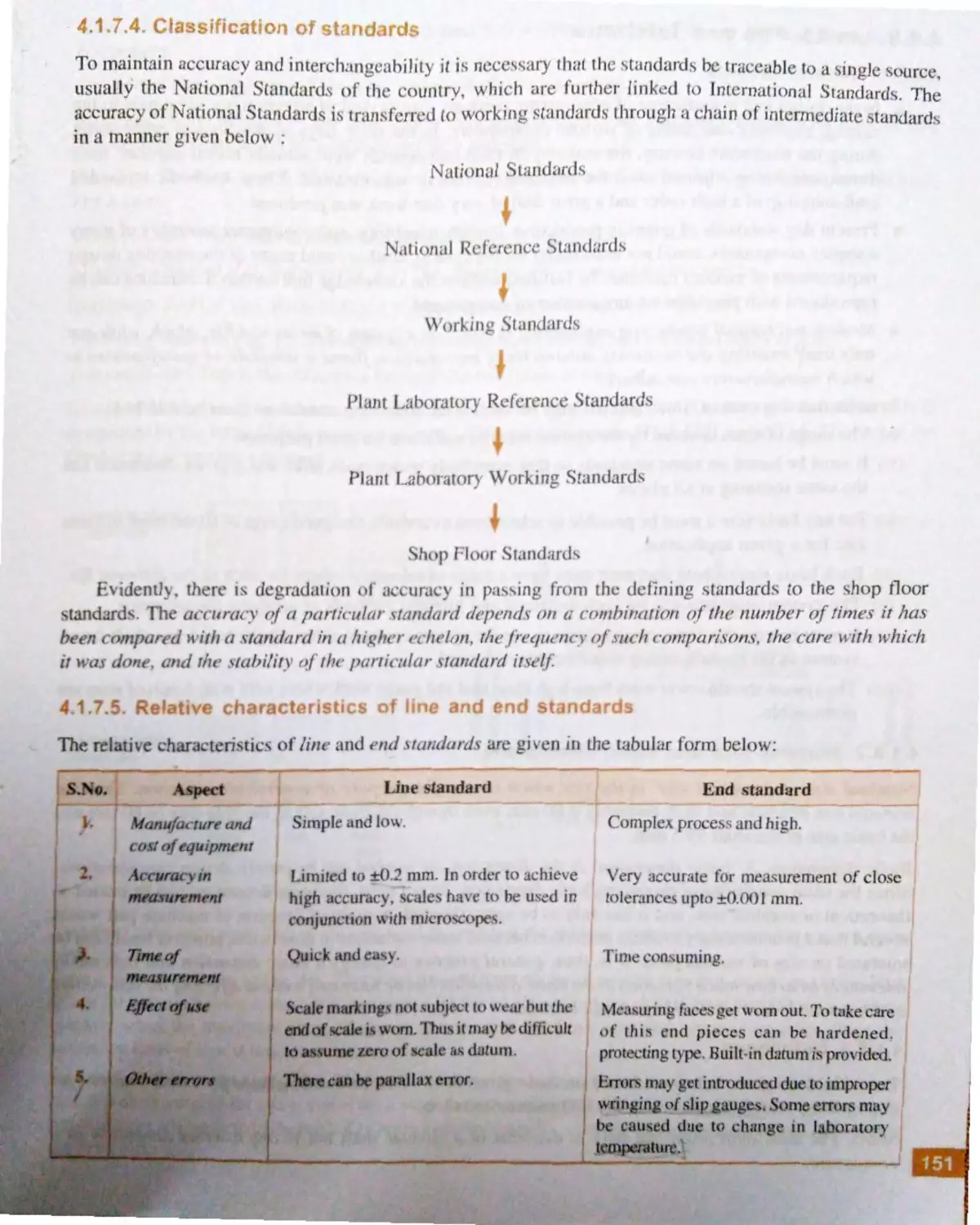

4.1. 7 .4. Cla ,sification of

standards .. .......... ......... .. 151

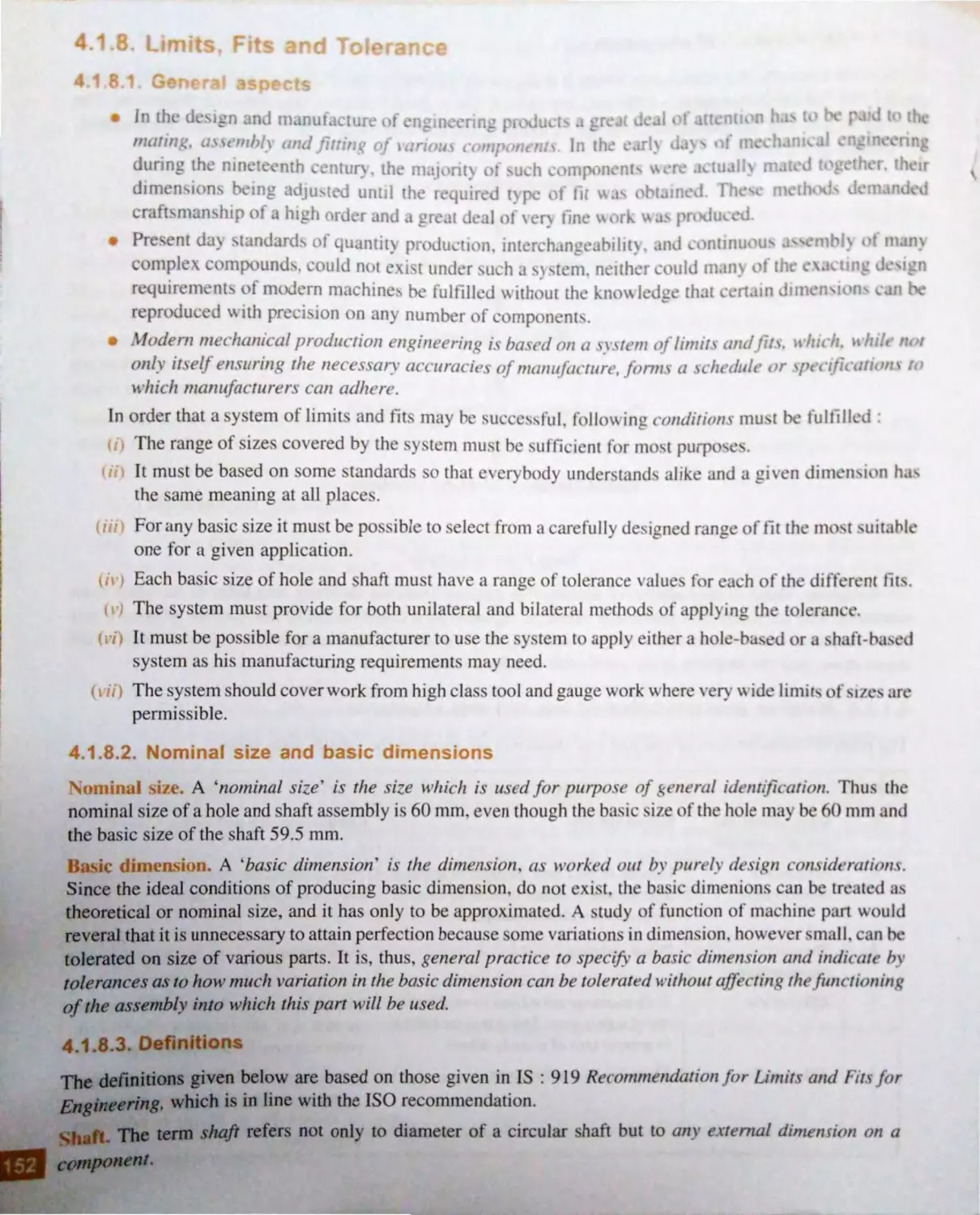

4.1 .7 .5. Relative characteri tics

of Line and End

standard..... •.... ·· ·...... ·.. ··

151

f 1.8 . Limits fits and tolerance ............. 152

4.l .8 .1 . General aspects ..... ........ 152

4_1_8

_

2, Nominal size and basic

dimensions ........ .... ....... l52

4.1.8.3 . Definitions .................... 15 2

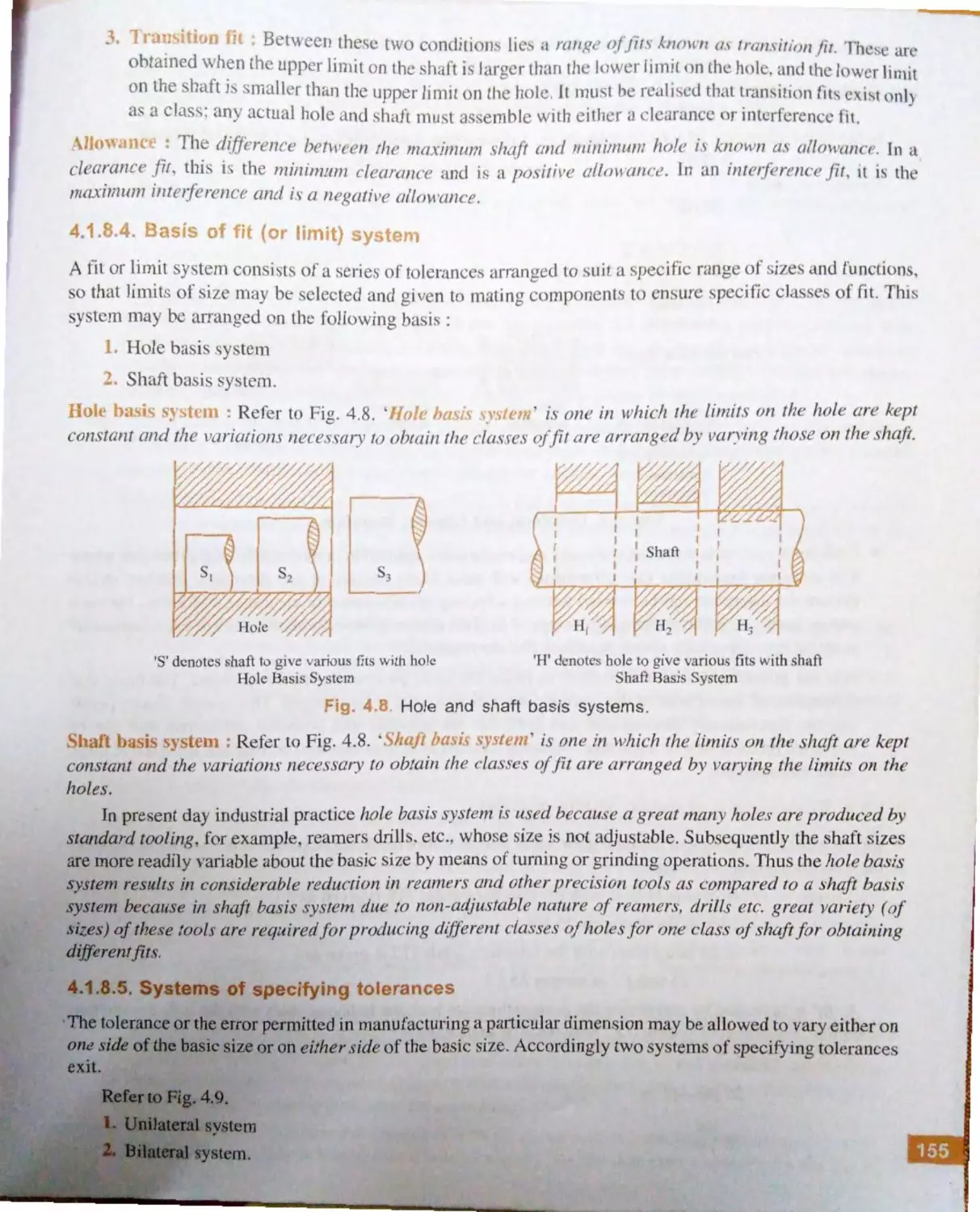

4.1 .8.4 . Basi s of fit (or limit)

system ....... ...... .............. 155

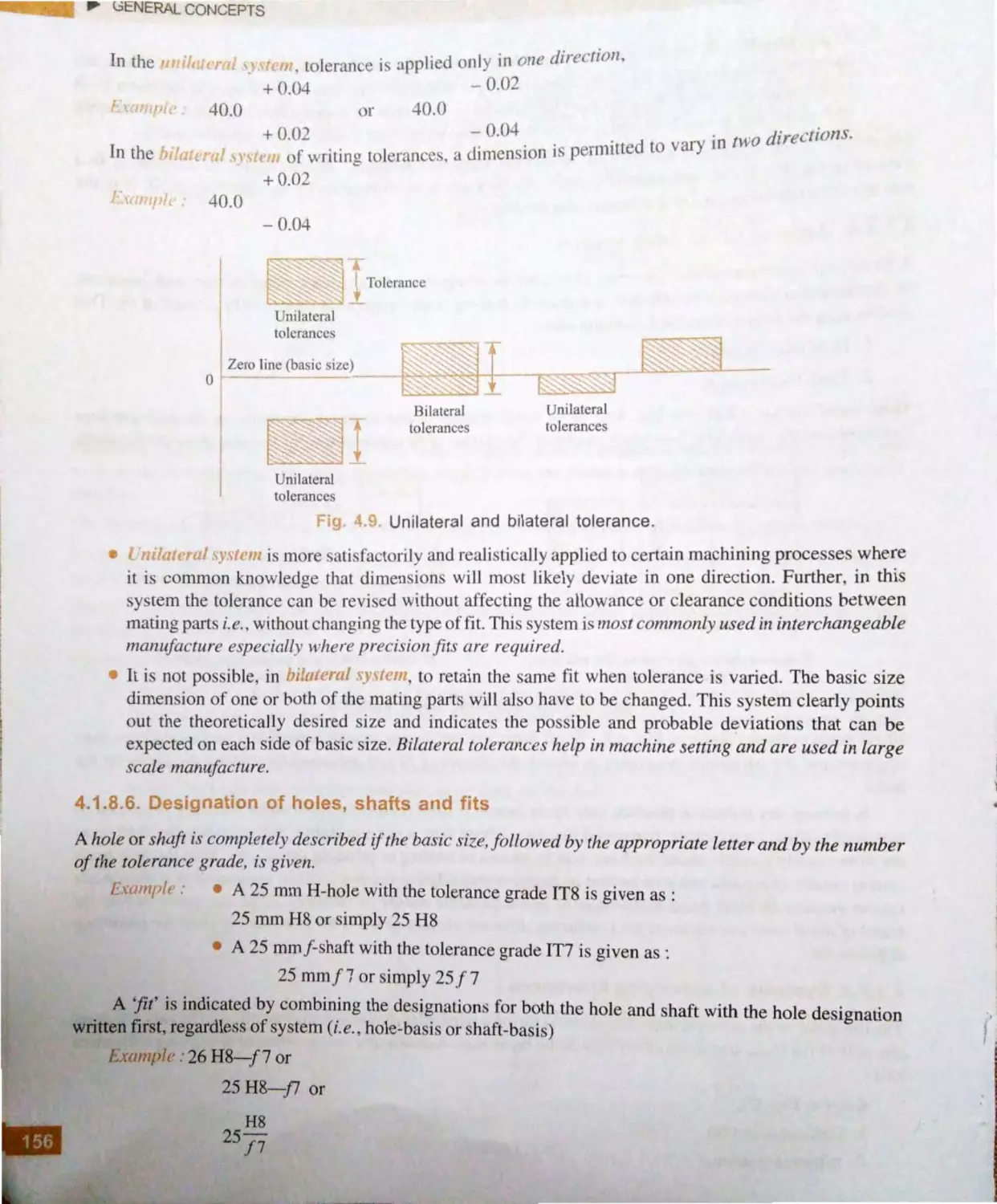

4 . l .8 .5. Systems of specifying

tolerances ..................... l 55

4 . l .8 .6 . Designation of holes,

shafts and fits ..... ... ... .. ... 156

4_1.8

. 7. Commonly used holes

and shafts ... ...... .. ........... 157

4.1 .8 .8 . The Newall system ....... 157

4 .1 .8 .9 . ISO system of limits and

fits ........... ...... ... ............. 157

4.1.8 .10. Types of fits .................. 157

4.1 .8.11 . Concept of interchange-

ability ..... ........ ....... ....... 158

4.1.9 . Methods of achieving precision

and accuracy ............................... 159

4.1 .10. Sources of errors .......................... 159

4.1.11 . Classification of measuring

instruments .................................. 161

4.1.12 . Classification of methods of

measurements ... ........................... 162

4.1 .13. Selection of instruments ............. 162

4.1 .14. Standardising organisations ....... 162

4.1.15. International System of Units (SI) 163

4.1.16. Gauges ......................................... 165

4.1.16.1 . Classification of

gauges .......................... 165

4 . 1 .16.2. Description of some

commonly used

gauges .......................... 165

4.2. Principles of Measuring Ii:istruments ....... I 69

4.2 .1. Definitions .................................. 169

4.2 .2. Classification of measuring

equipment ................................... 171

4.2 .3 . Technical specifications of

·

·

172

measunng mstruments .............. ..

l... li'lll ipl', 1)1 Ill (.'hll\i.d

m~asnri11' im,ll'llttH·tlf, . . ....... ....... I n

L-· t1. Ll <rIn thod ........,. ... .. l71

· L ·· 111ic- m tht d............. IM

l..Lt 'vr ·w awl screw-nt11

m ·thod .................. ...... .. I I

L l,5. Prin<.:ipl •. ·

of opti ·ul in.· tn1m uh I /(1

· L2... I .. R fl· ·tion ............. ,... .. . I l(,

I frnct ion ........ .. ... ...... I . tr,

] PllS 'S ......... , ......... ........ 17'K

-L..,.5.4. Int ·rf re n , , ................... I / 't',

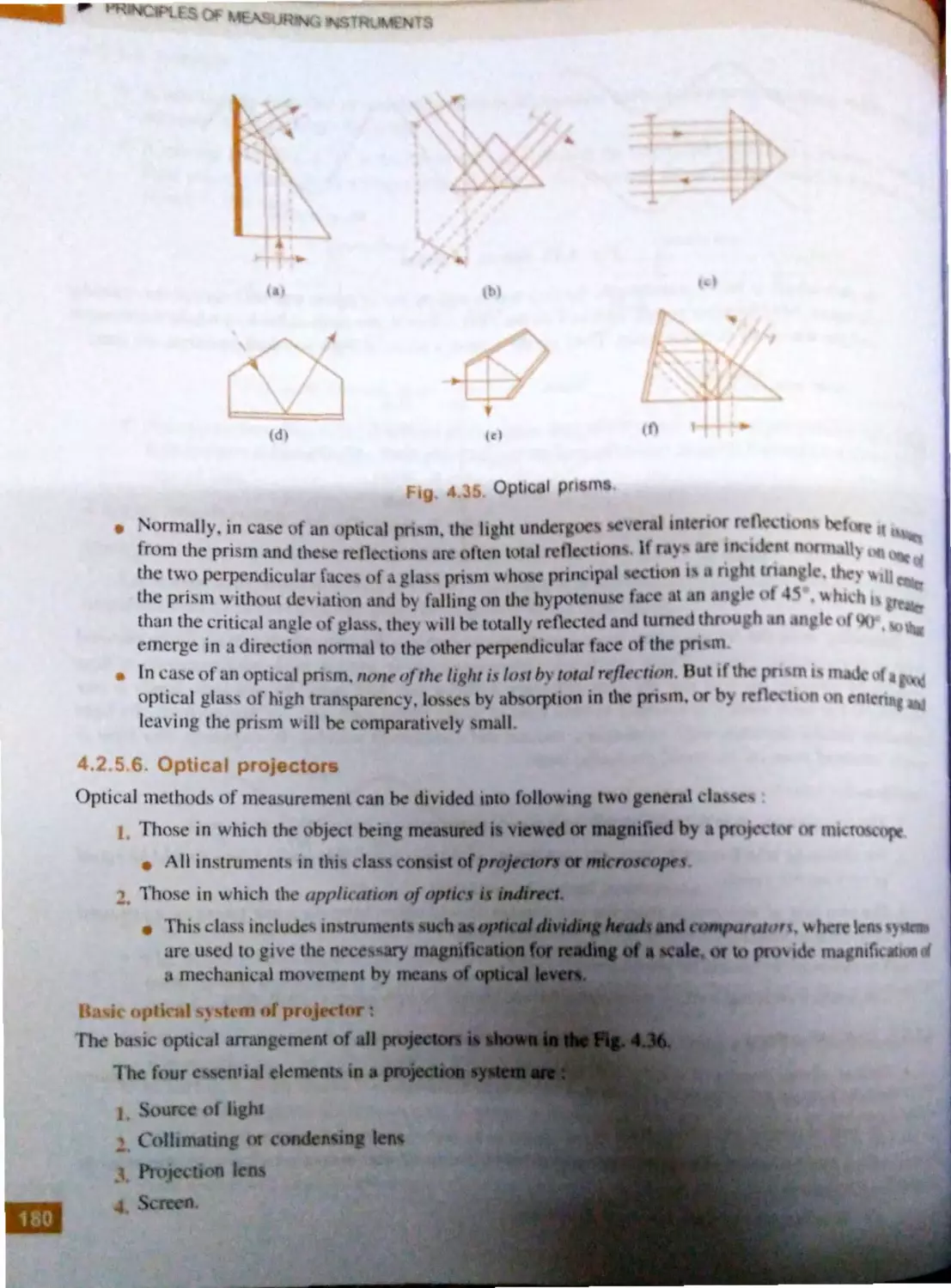

· ... ... 5. Opt il.:al pnl-im .. ...... ........ 17')

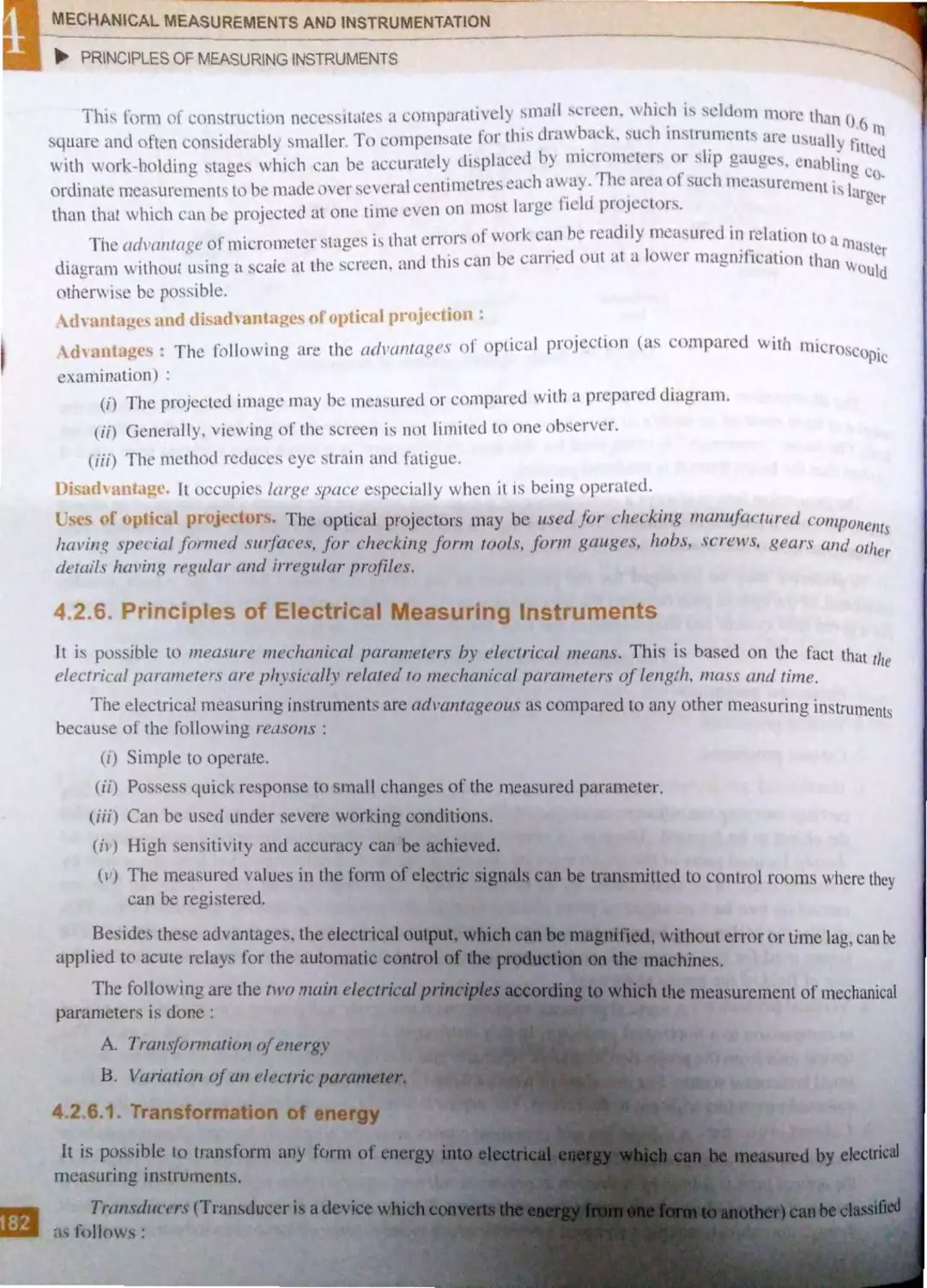

. ..6 . Optil .11 1mi ' ·ti..1r s ......... I HO

~rincipl ·s or 1' ·trim ! n1l·a. u, in1,

lllS(l'Ullk'lll. ................ . ..... ......... . .. I H

i. _. 6 .1 Transl' Hmation of

en·r•y ...... ..... .... ............ 182

.2.6 .~.

· 11 intion orcl ·ctrical

pa an, ·tt rs .. ......... ... ...... f 8

.2.6.3. Ell'~tri<.:a l 111 usurinp

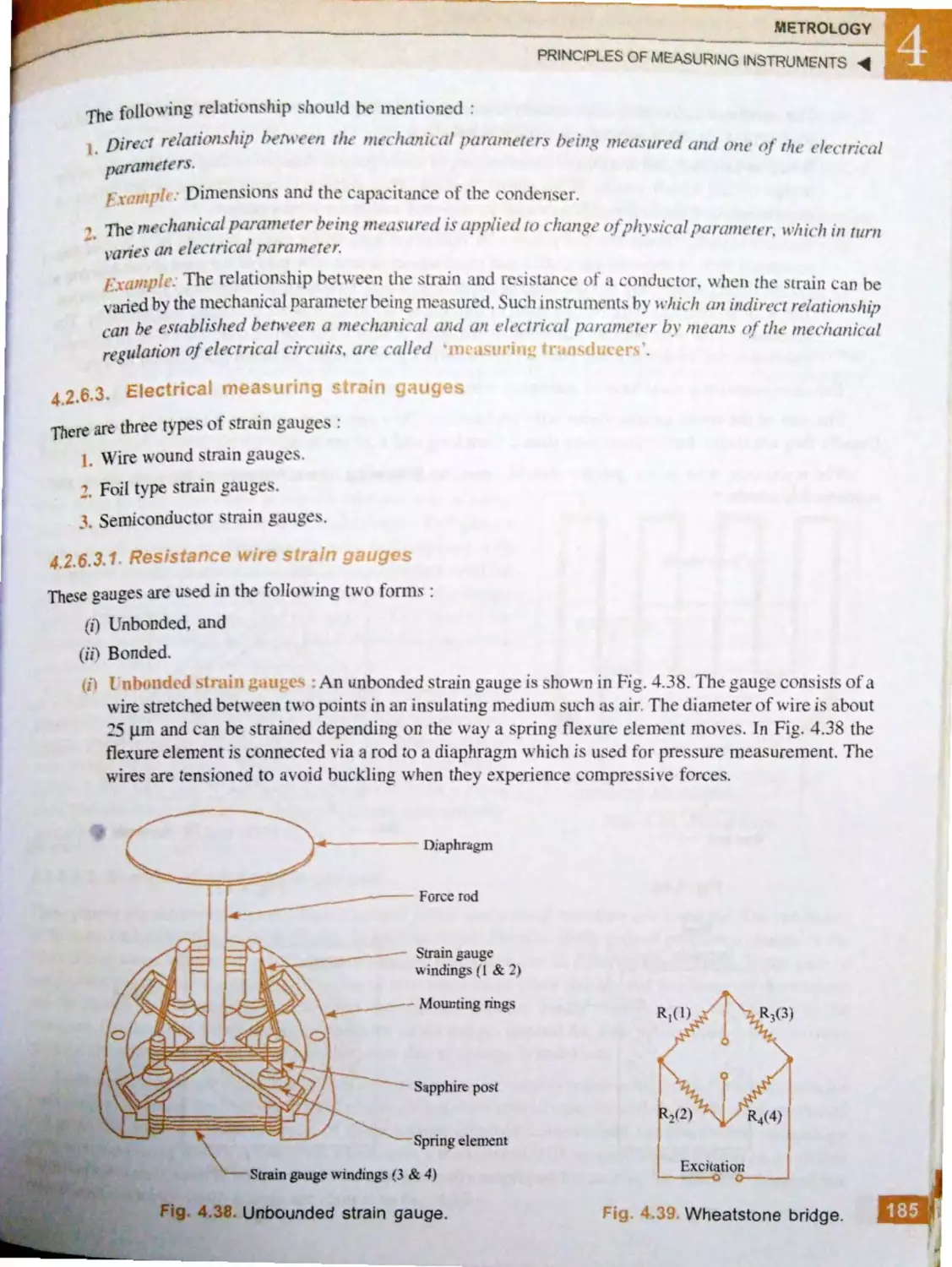

~trai n ' tllJt'S .. .. . ........ ... lX

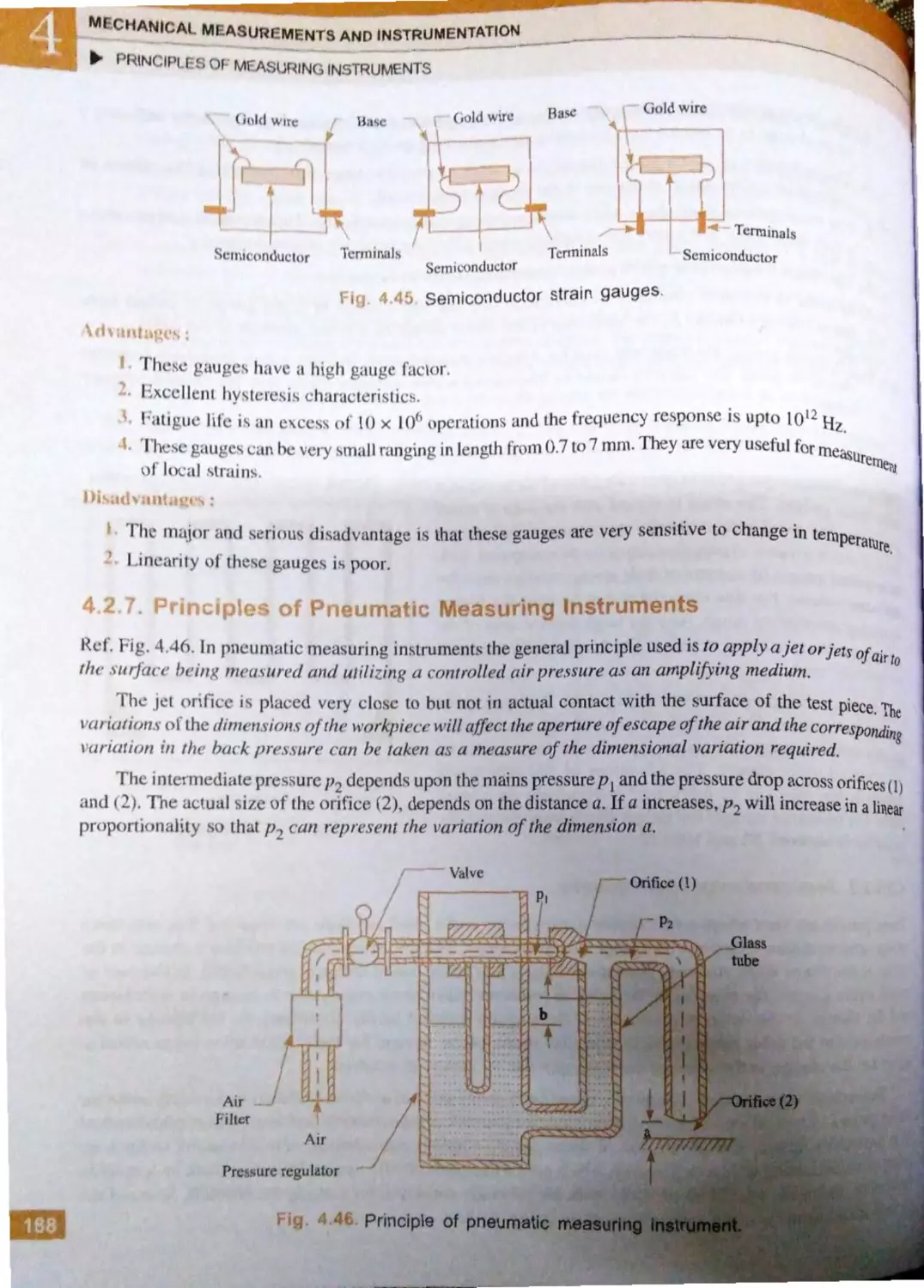

4..7. Pri nciples of pneu in a ti · mea~rn ini>

111 llUJllcnts ...................... ............ 188

Lin ar M a: urcments ..... ......................... J 8<J

4..3.1. En in ·cr 's sl ' ·I ru l .................... I 89

4.

·-·

alip rs ... ................ ................... I ) I

.3 ._.

t.:rni r calipers ..... ..... ................. I ) I

4.3 .3 . l. Introduction .. .......... ..... 19 1

4.3.3.2. Th .. Vcrni~ r prin ·ip lc ... 192

4.

.3.

.

Type. or Vcrni<:r

calip rs ..... .... ......... ..... .. 19]

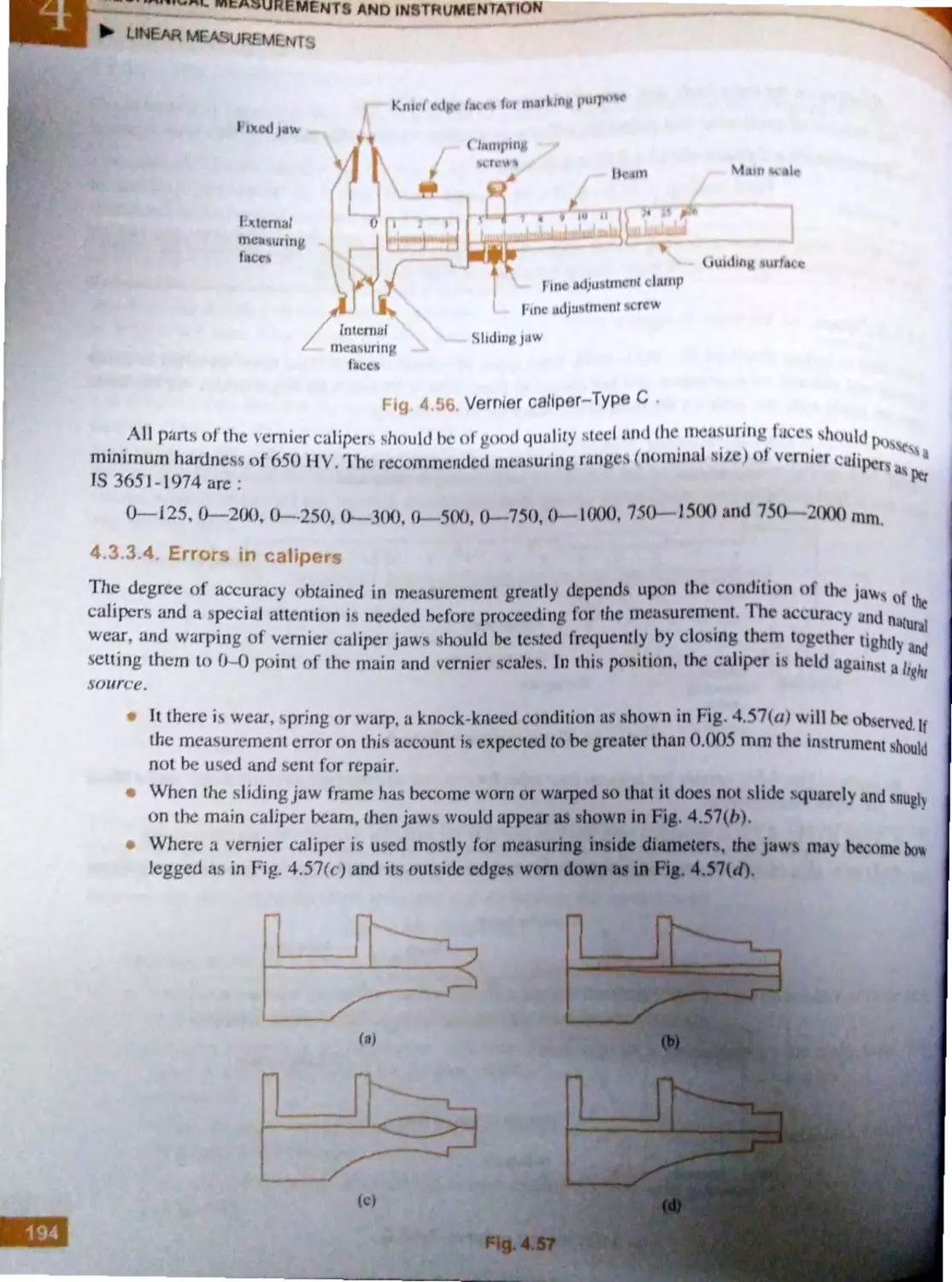

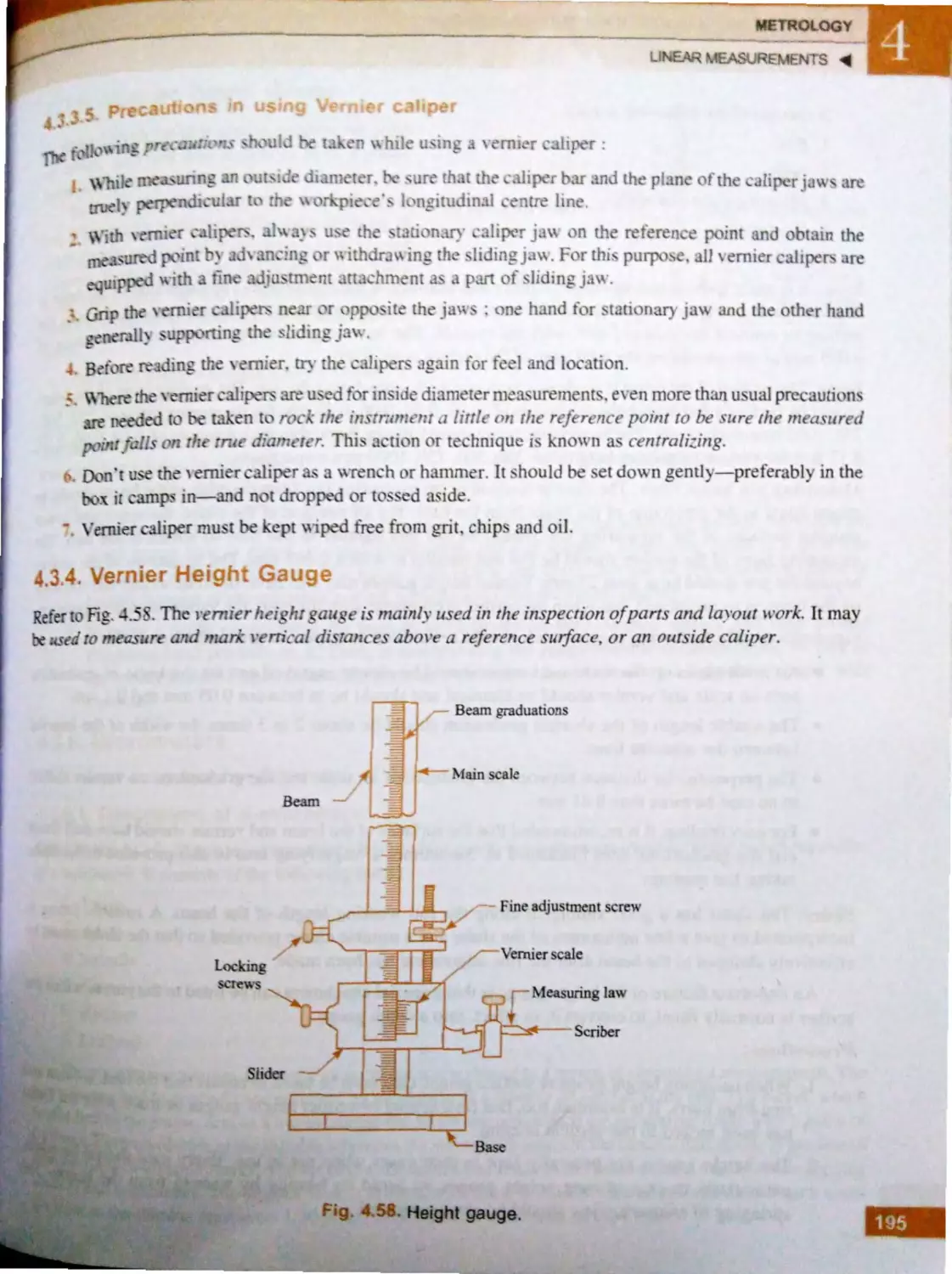

4.3.3.4. ErTo rs in a lip .. rs .. .... ..... 194

4.3.3.5. Pr cauti )OS in usi n r

Vernier caliper .............. 195

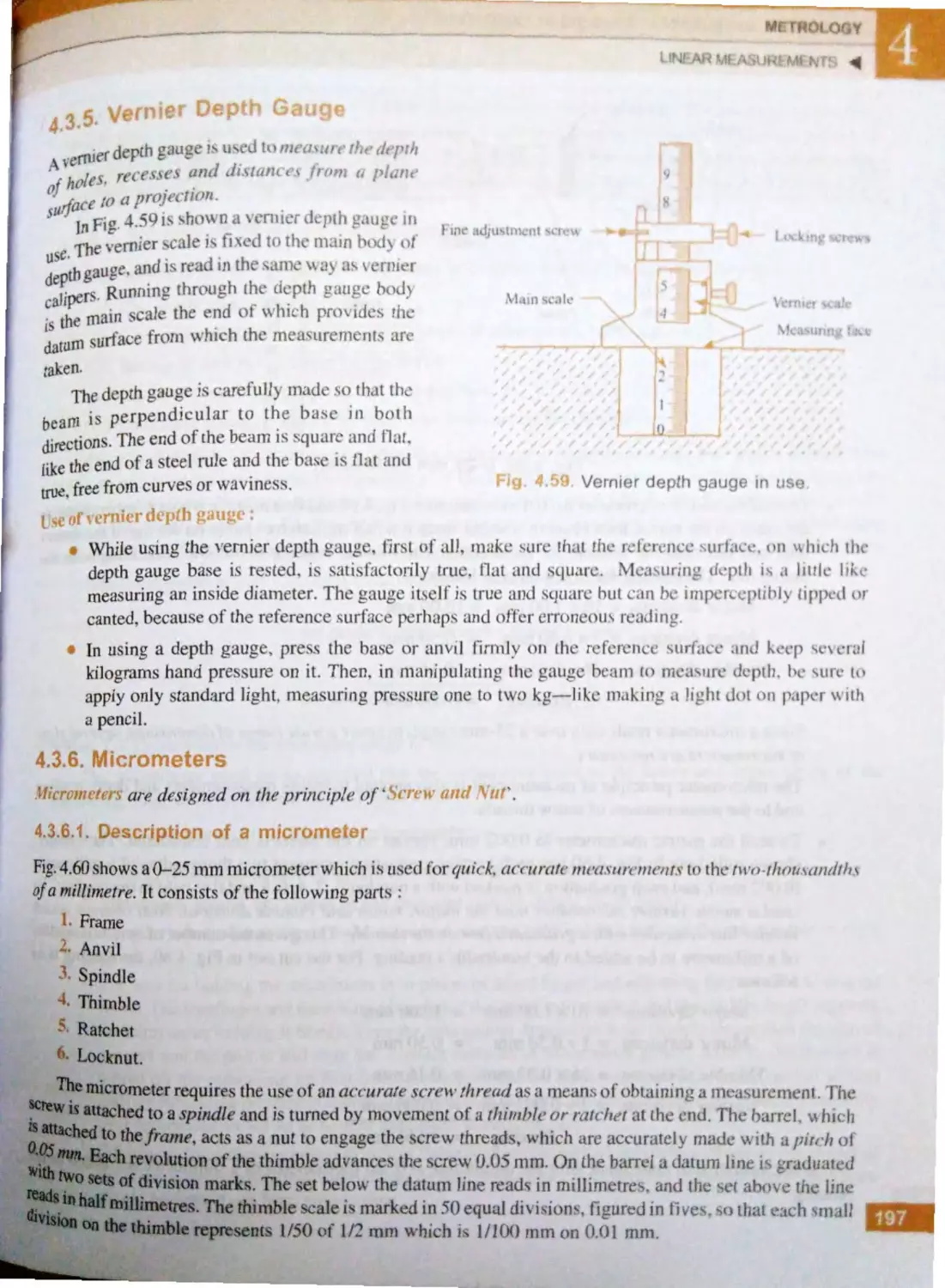

4,,3.4. Vernier h igh t gaug ... .. .... ......... 195

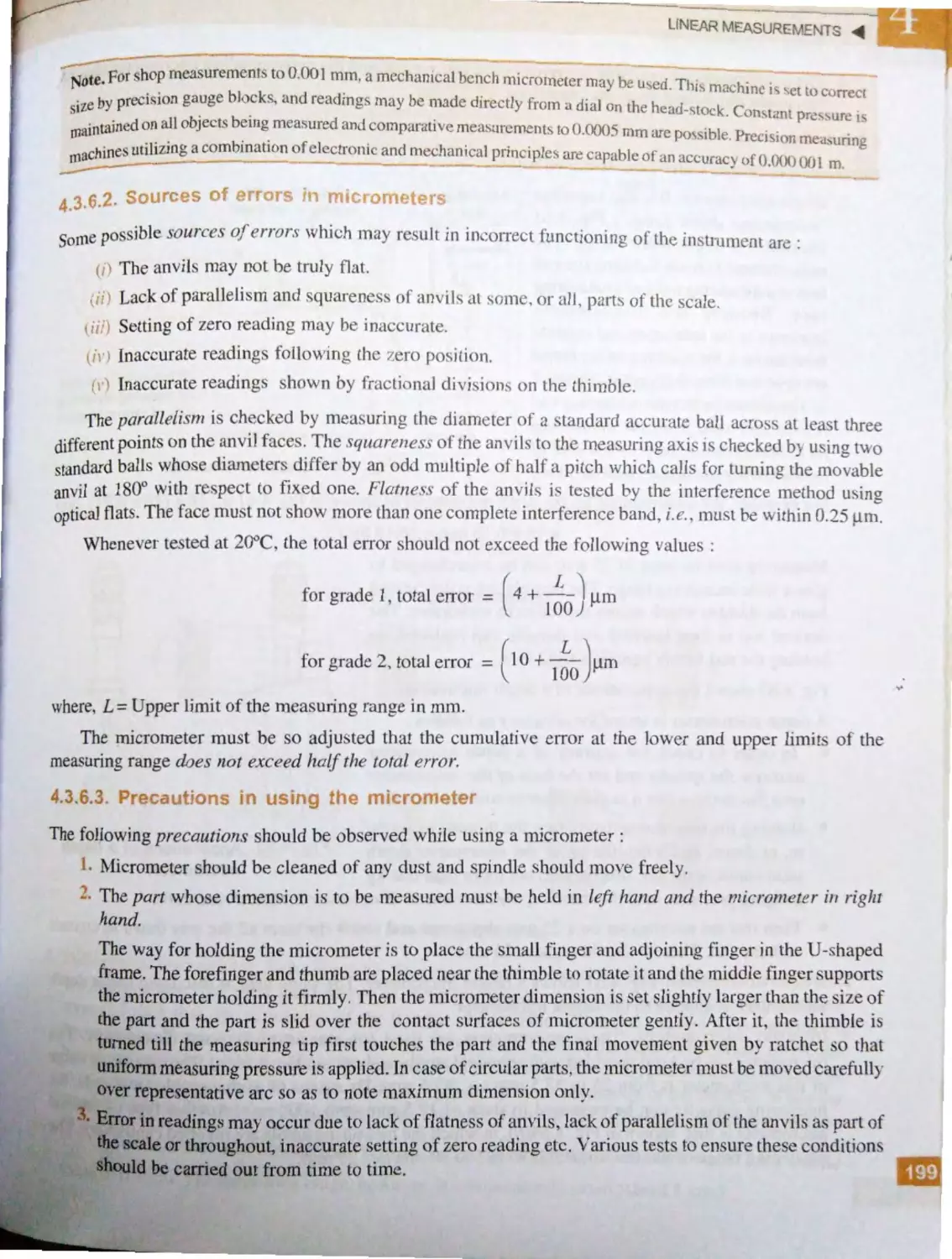

4.3.5. Vern ier de pth ga uge .... ... ...... ....... 197

4.3 .6 . Mi c rom tcr.............. .... .... ... ..... ... 197

4.3.6 .J. D ·scriprion of u

mi crom eter ...... ... .... ... .. .. 197

4.3.6.2. S ur csoferrors in

micro met r · ...... .... .... .... J99

4.3.6.3. Precautions in usin g the

micrometer .................. .. 199

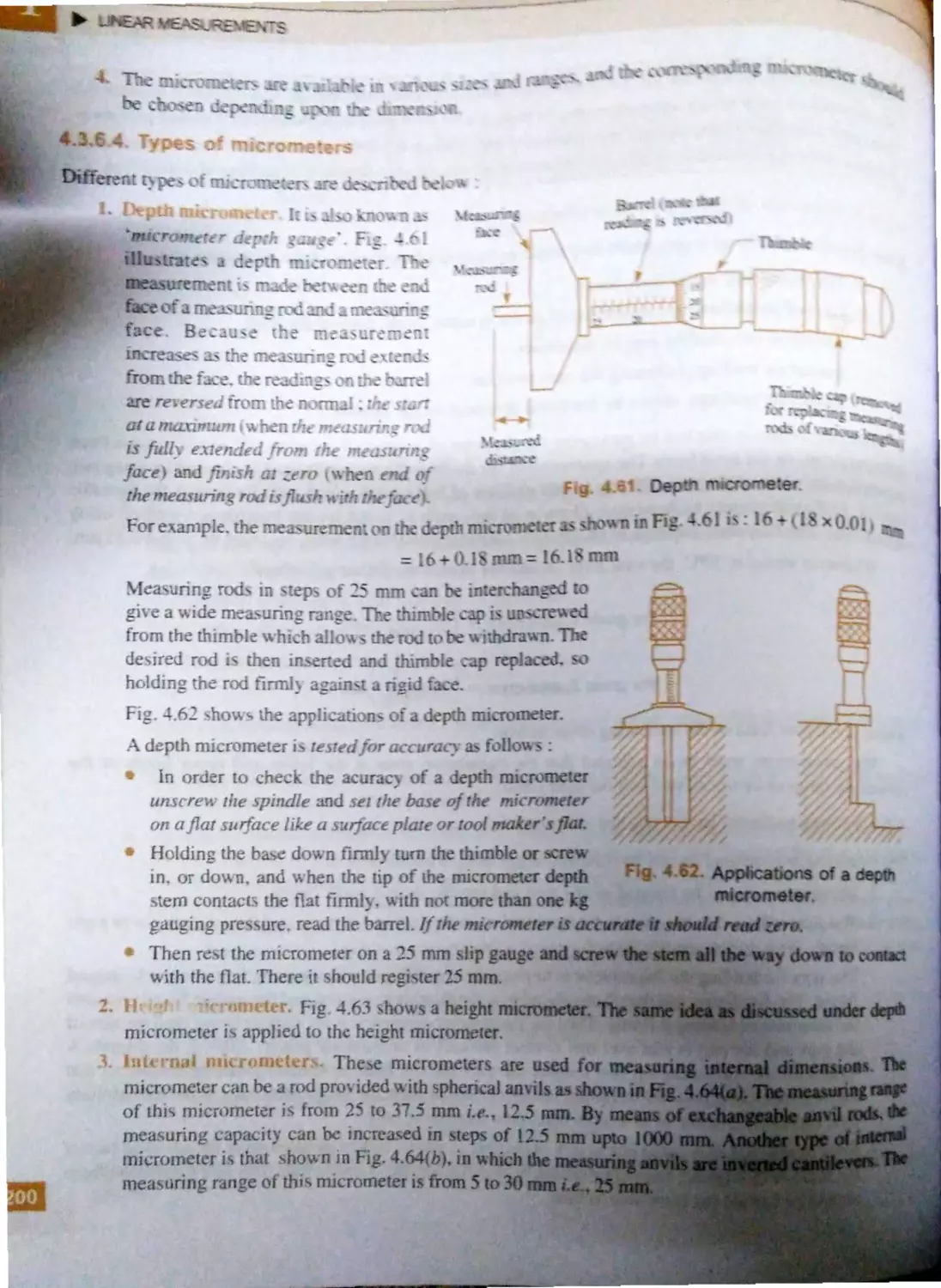

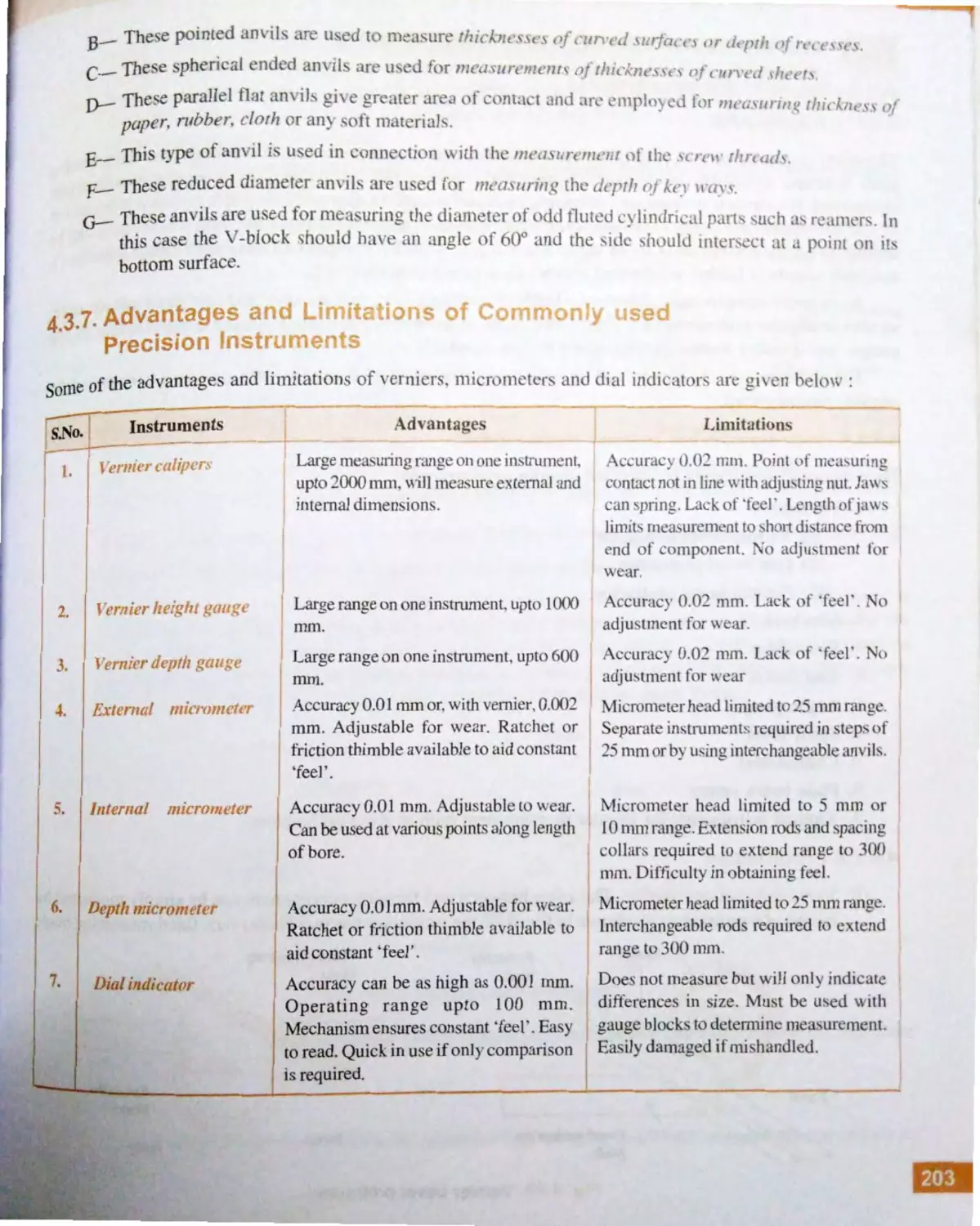

4.3 .6 .4. Type of micr meters .. . 200

4.3.7. Advantages and limitations of

commonly used precision

jnstruments ...................... ,. . . . . . .. . . . 203

r,In ·',

VII

,.

i\111uJiu :ind 'JHJJ , 1 , w11t11·111 1 r,, ,, ,,,,.,,., %'J4

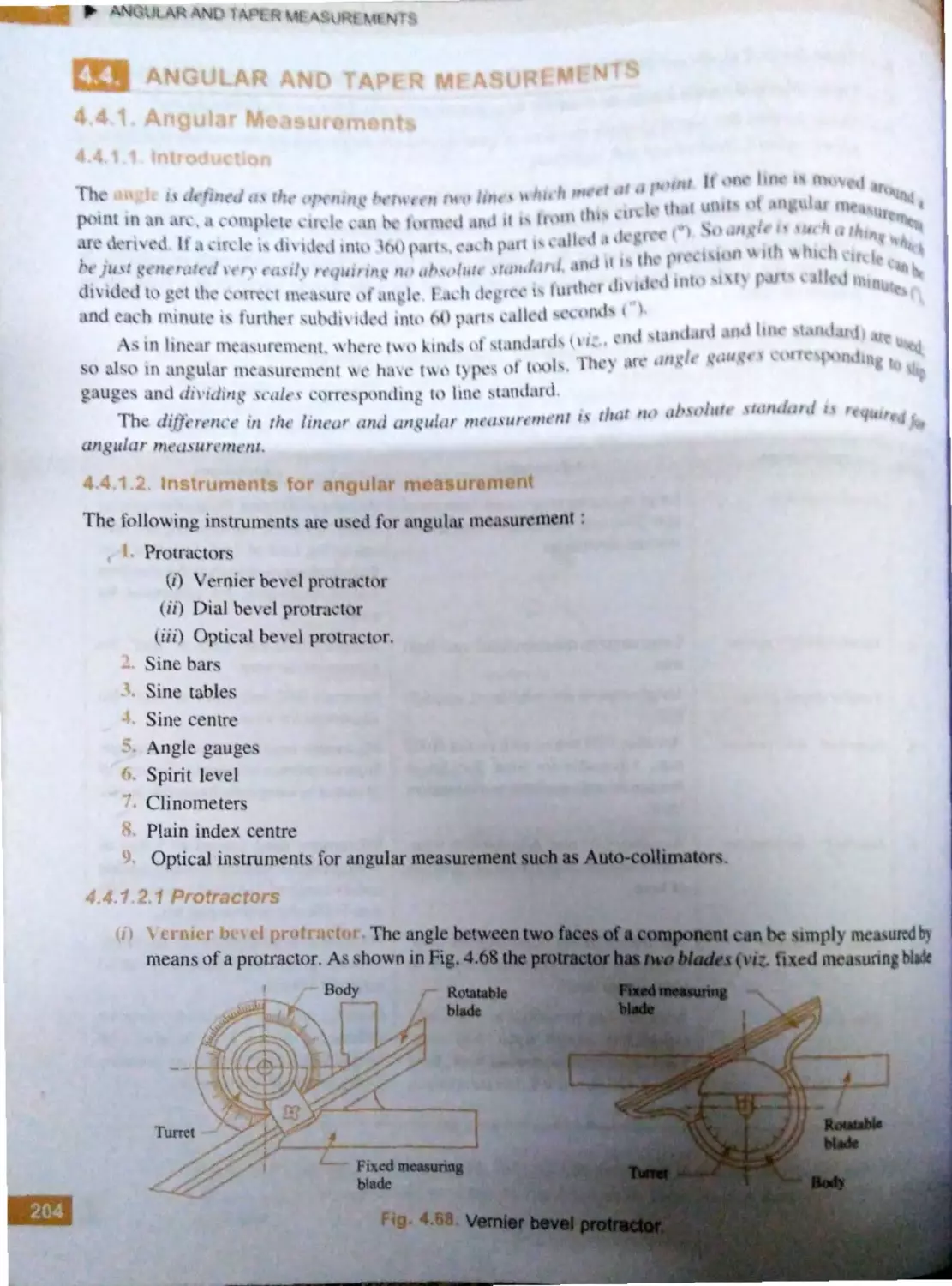

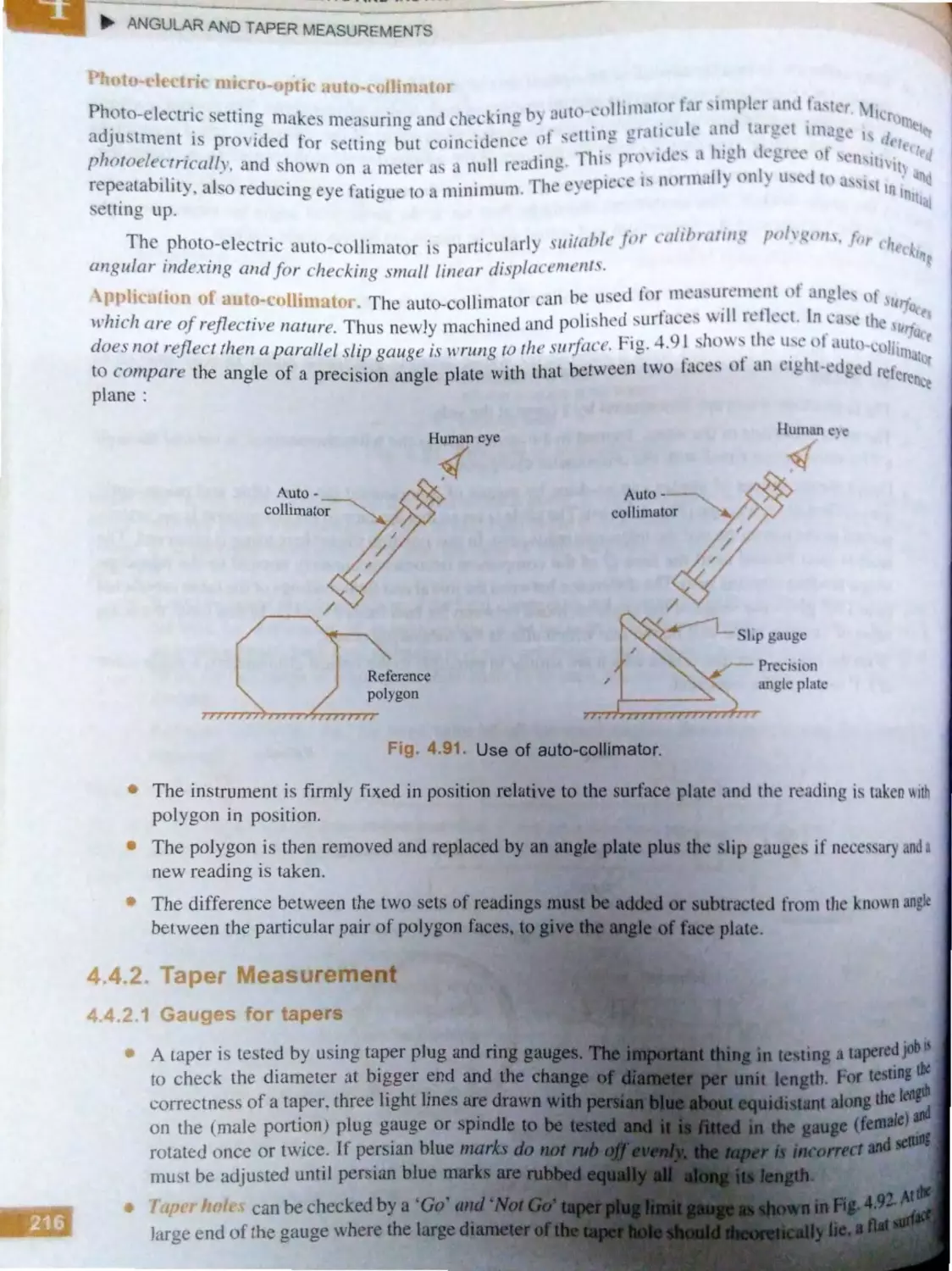

1J, I,. I . A1w1d·11 ir1 ·1110, 11,, 1,1 · ,

.,,111,,·,•· ;. <vi

I~,/1,I f. I,,1Iq,11, 1 I1'111 .

,.,,,

, ;)}1

4,tl.J .2, ft1 IJ1,H<:1 I' ji,1{11,Vt fr

101 ;~ ll 1•1 J<'Jtl ,,,.,,.,, ,,.,,

;)4

tl,,4.' ,

'J'HJ •J IJI( ;JI 11".0 l·t 1. ,

,••••, ,,., ,

?, (J

44..,I, <htf1' ''1j(,Jl:iJ ·1 ·

,m,, ,, /4ir,

4A.7. ." .. 'I',,,, 'j IHl 'I l lflf'

Ill' ti lltJII 1Jl•, ,.,, ,,,.,,,,,., ,, 2' %

•

1 ·('1 ·w 'I ltw:1d M ·a·,1J111wnt •., ..,.,.,,,.,,, ,. Z.2(J

4.. I . hllrlldu<. lioH , ... .... ,,.., . . , .,,,.,, .,.,,,, 2'L. <J

IJ .1.

.

c'la•1 ,i ii( :111, ,n ,,f 1hr (,Id' .o,,,, ...... i:z f.

J:l "tll' 11·1: ol ;11w J ltt.:}.s J, ,..,.,, .

..

'Z2

, 'pc :tJH .it,, 11 '. , ,fa •,,;re N 11111,; J , 222

•

J ,r m'> qi 11,,·ad·, ,.. _

,,,.,,, .. ,.. ,., .. ., ,. 22'

4. A I•, ror inLhn·ad ,.

........... ,, .. ,,,,. 22(,

4.5. 7. M ·a 1,UJ'lll , tlr Ill ~fll', (Jf :

.., ·

·w 1l1r •~d ................................ 22(,

..7. t. Lxt ·n wl ,<..

•wth··

JI )(

.,,..,.,. ...... 227

.5.7.2. l11l ·nwl.ere Nth ead

Il l · :,urc;J} ·t t ............... 2' 5

..8. S r ·w thr ·ad 1au , .., .. ........ ..... ...,. 23k

,..

icm M •, sur ·inent .. .............. , ................ 241

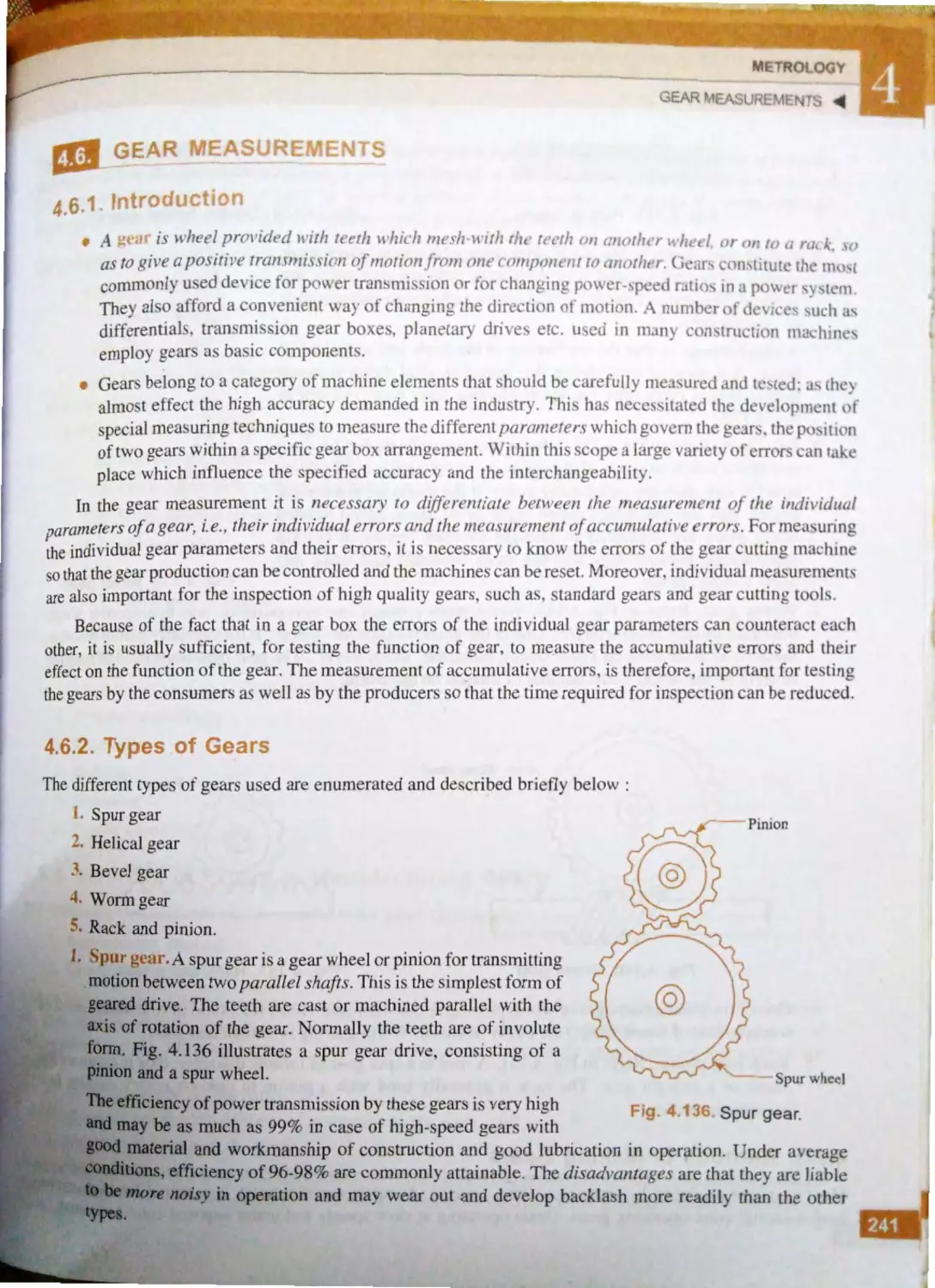

4AI. l11lroduc.,t io r1 ................................ 241

4.(,.2. Typ •~ of ,,c· n, ............................. 24 1

4.6 .

.

Mc1hc,<h, f

· kin,ge"r~,

....... ,,,. 242

4.6.4. So ircc!-. ol ·r o ~ in

manu fact uri

1car•; .................... 243

4.6.5. f orms >f μca r tee th ...................... 244

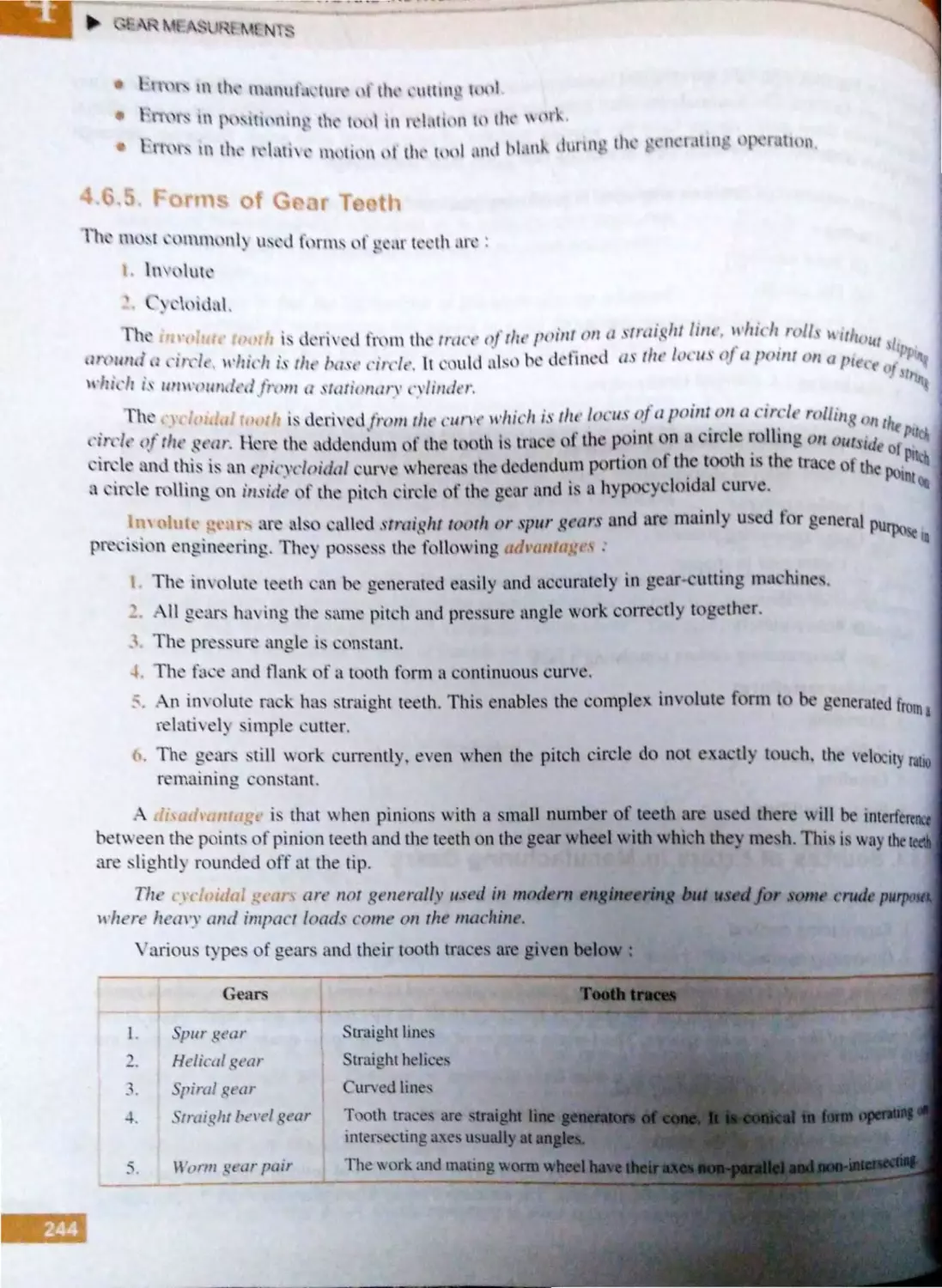

4. ).6. Involute curv · ....... .. ...... , .. ... .. ...... 245

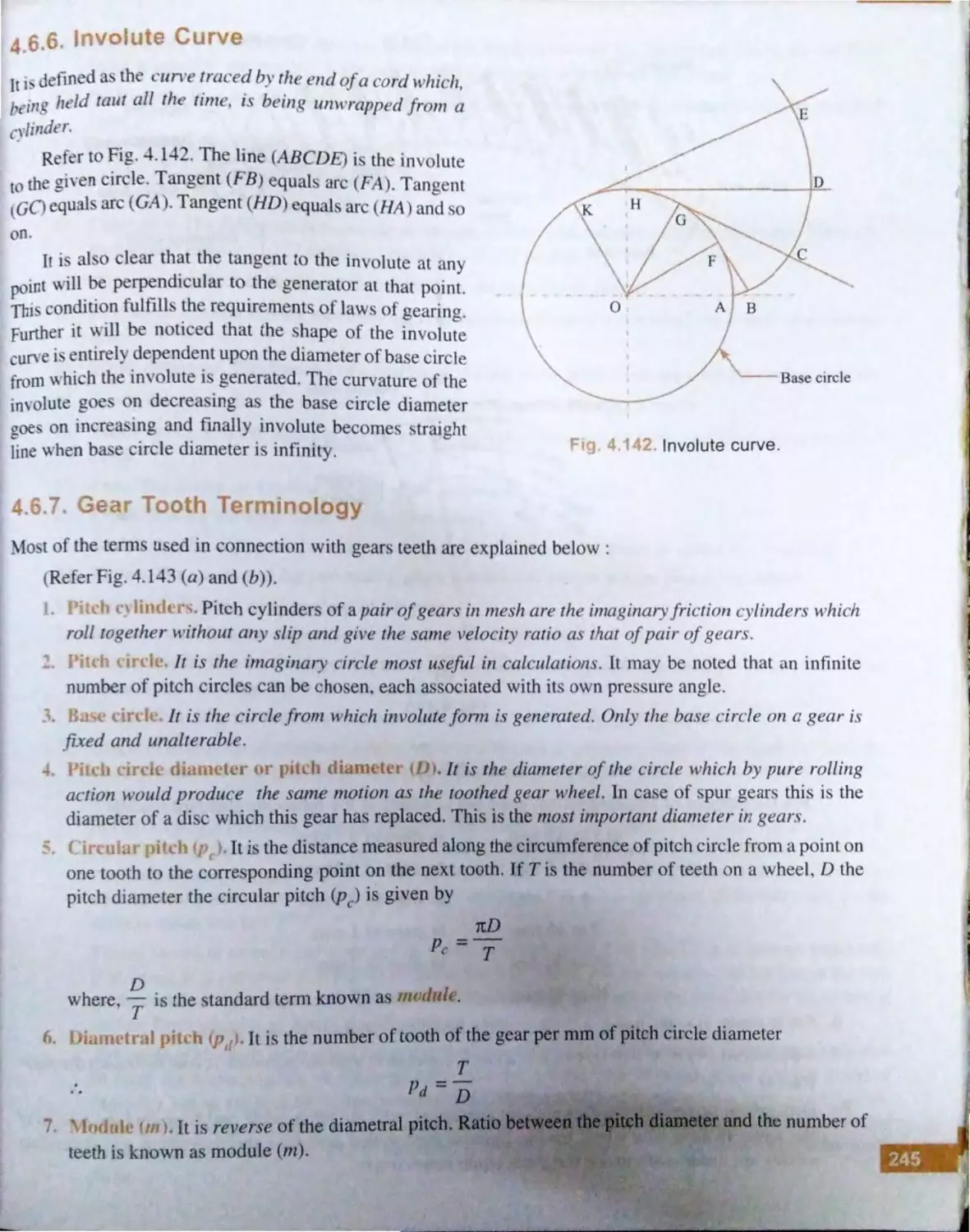

4 .(1 .7. (,car CJOlh te rm inology ...... ... ..... 245

.6.8. Measurement and tc~ting f

1i pur 1 ca r .......... .......... .. ........ .. ...... 249

4 6.8. 1. Measurement of woth

thickne~s ........ ..... .. ... . .... 249

4.6.8.2. Measurement f tooth

profile .. ... ................. ..... 252

4.6 .8 .3. Mea~urement f pitch ... 254

4. 6 .9. Gear errors .. ... .......... .................... 255

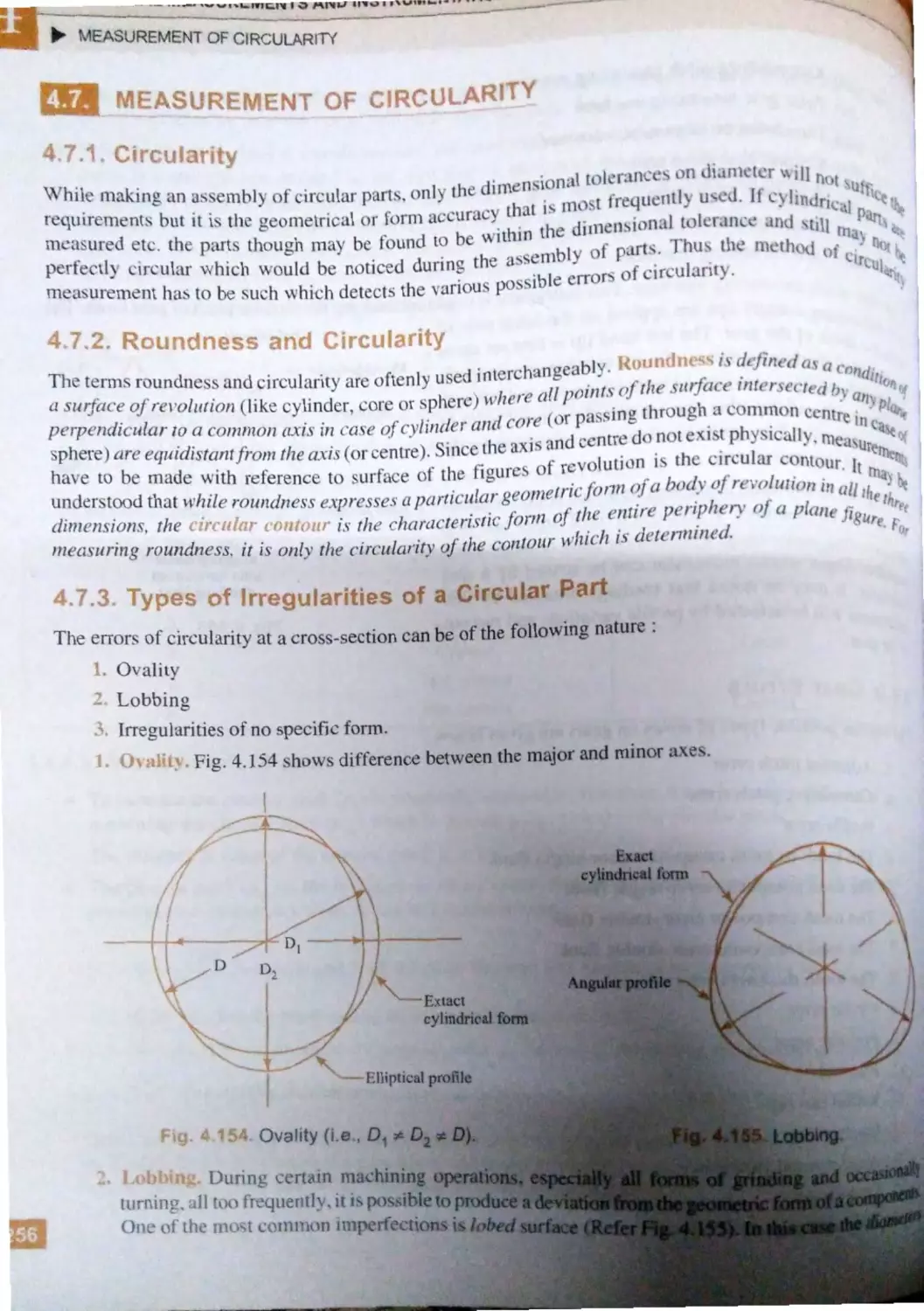

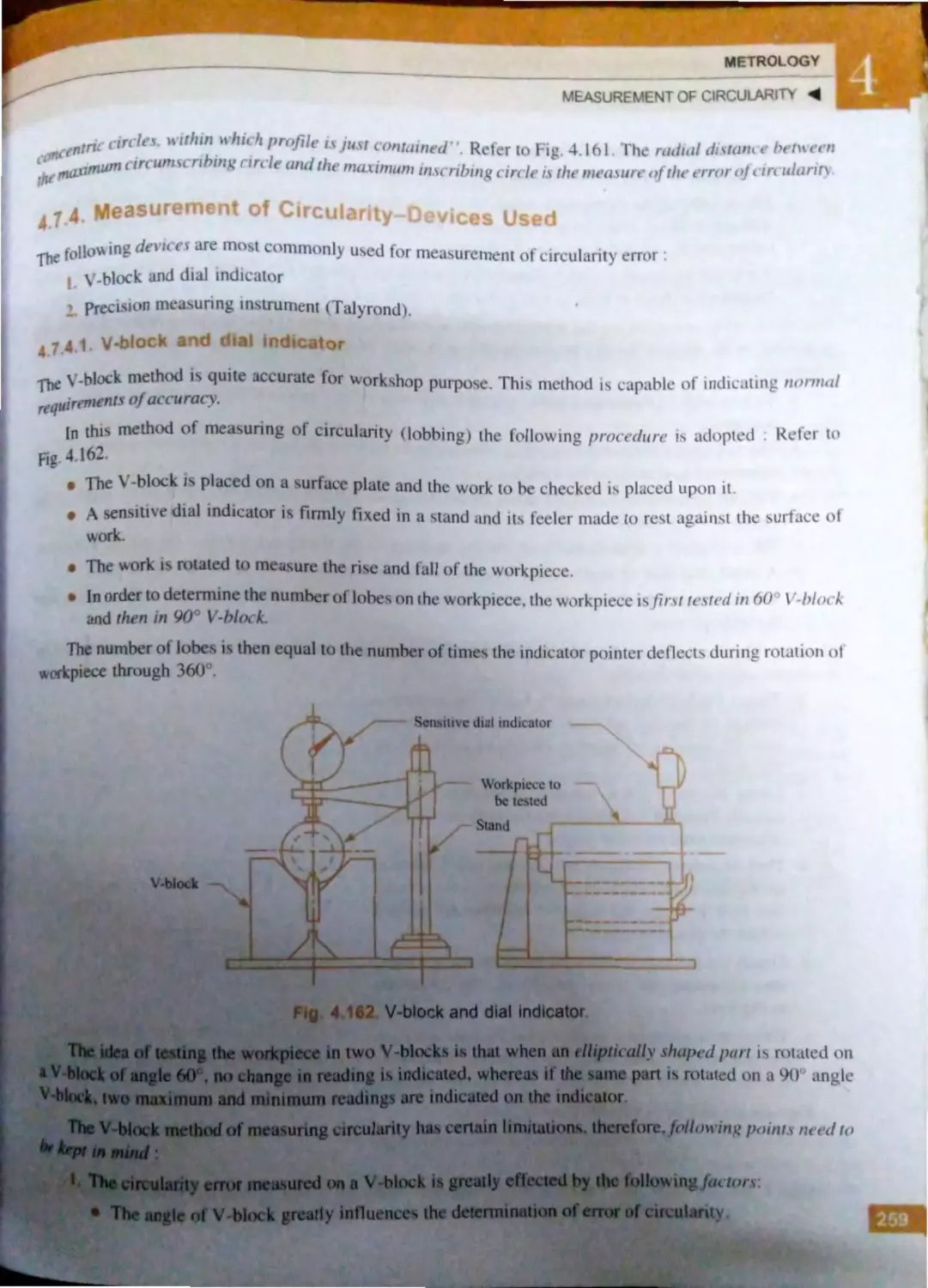

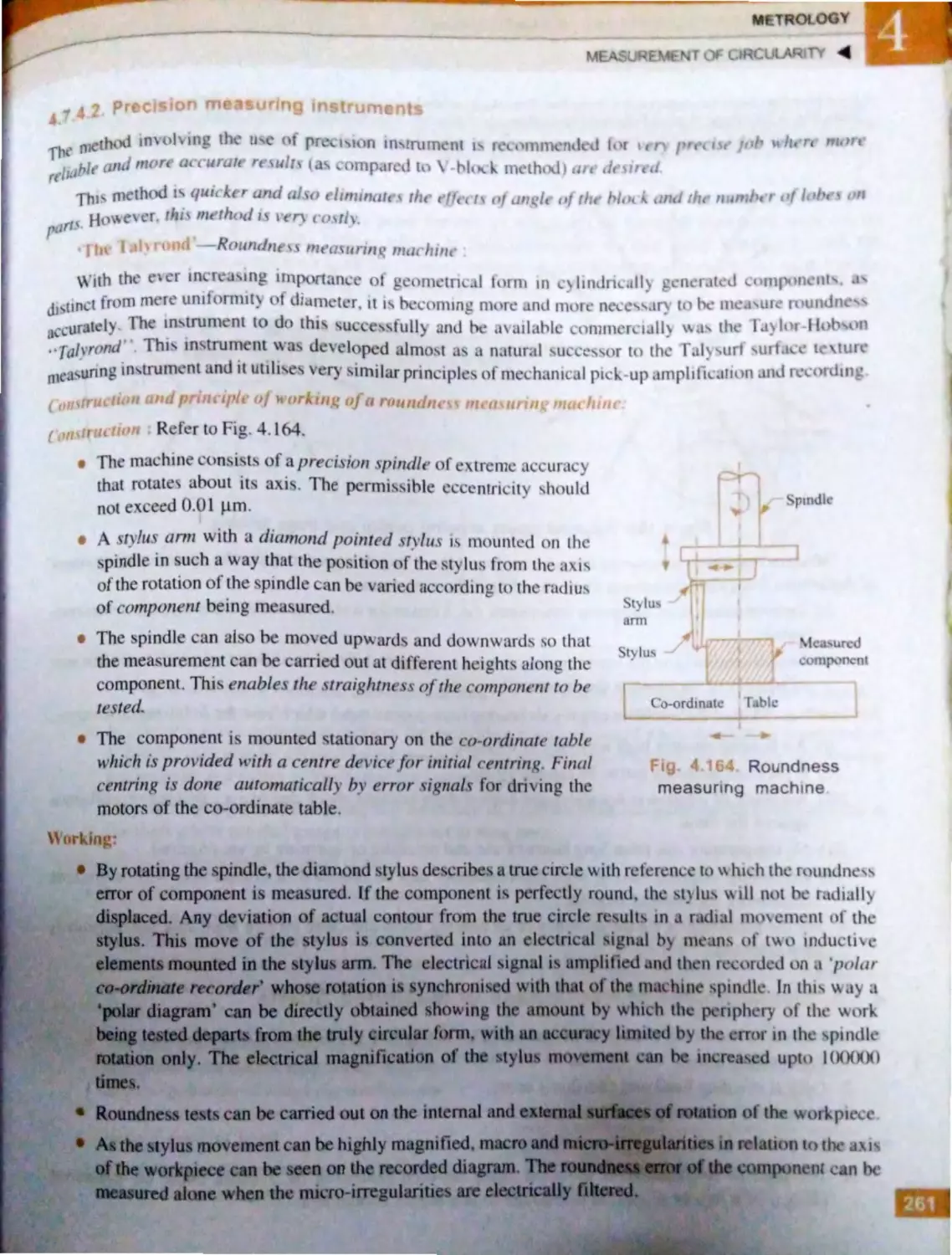

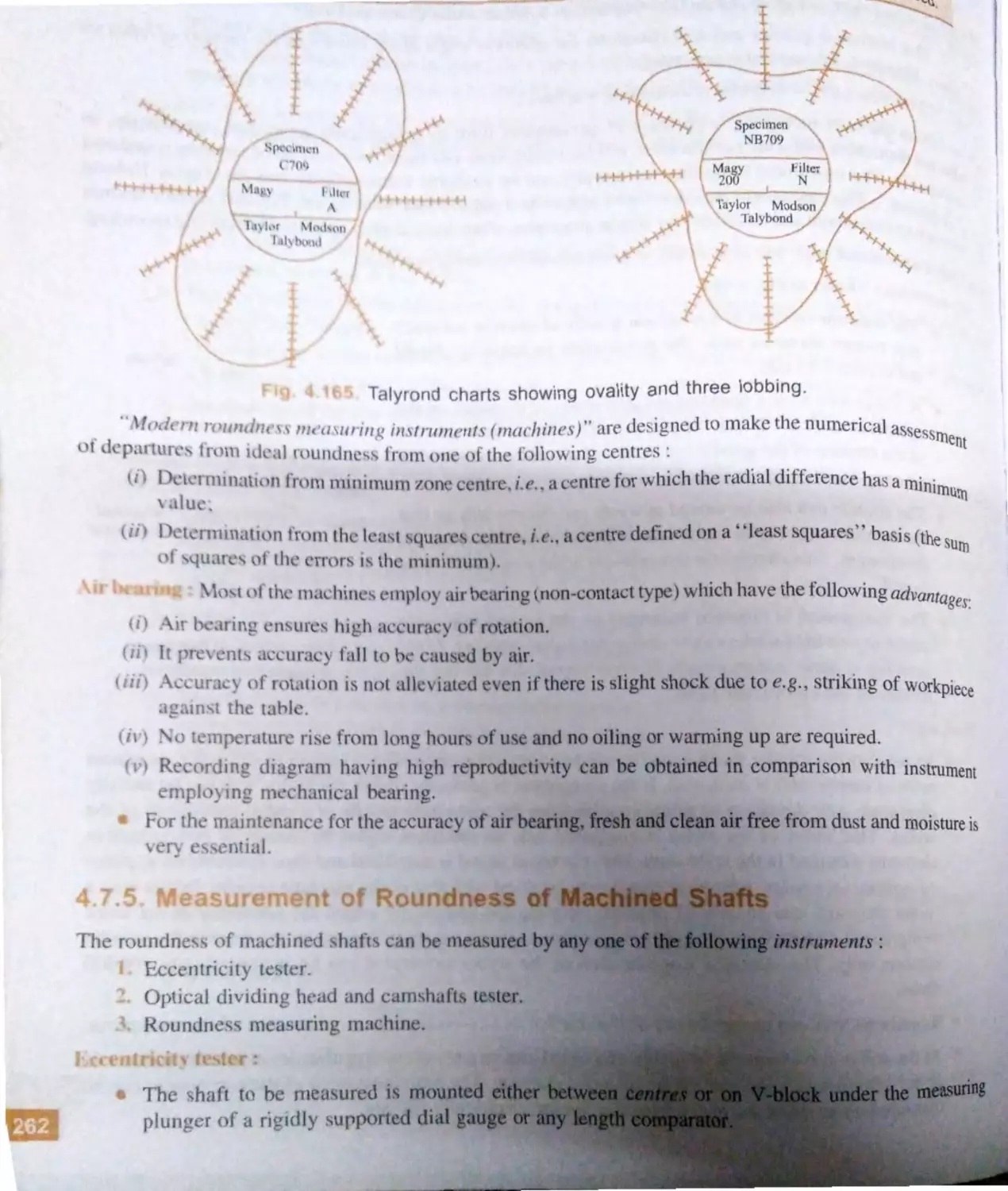

. 7 Mea sur ement of ircularity .................... 256

4.7. J. ircularity ............................... .... 256

4.7 .2 . Roundnes s and cfrcularity .......... 256

4.7 .3 . Types of i1Tcgularities of a

circu l ar part ...........................00••· 256

4.7 .4 . Measurement of circularity-

devices used .......................

4

... . .........

).

-L' .~.L Di· l ind, ·t11 r ............... _

1

➔

..,

comp·

·tt

r .... ........ ........ 2 7

. 5.3. ig

tc r ......... 1 6

.(

.:

.4. Joh

1kmor· . ..

2l

1.8.5.- .

ivmtg!-anddis-

' J ·antae-' ·

·m

·hanic, I

......... ......... 27

4 ..6. pti a]

4.(

.6. l.

.6..... ptic4' l k, er .................. 27 1

4. .6.3. imple pti ·a l

comparator ..................... 27 _

4.8.6.4 . ook pti al

comparato ............ .. ....... 272

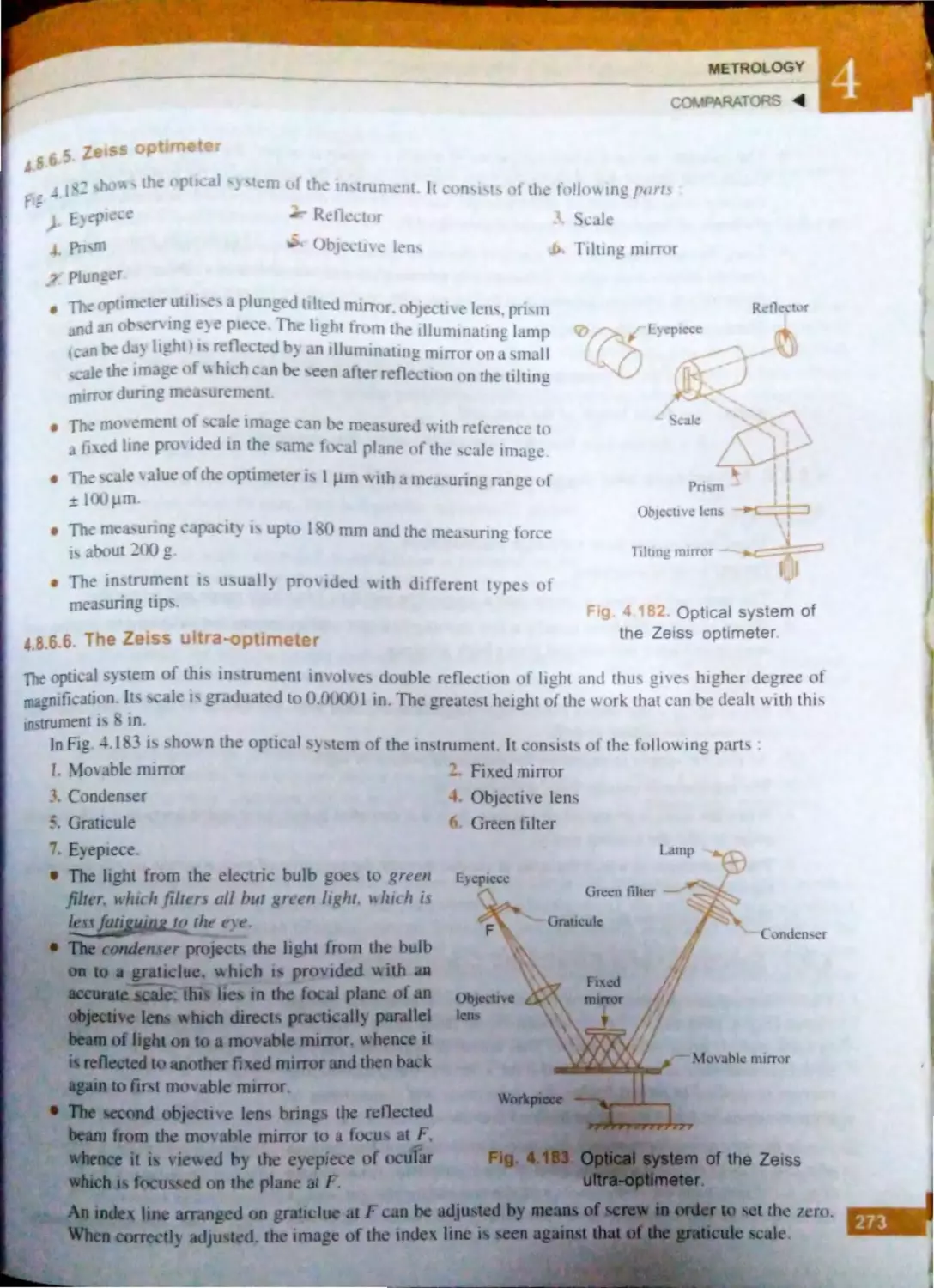

4 ..6 .5 . Zei~ optimet r .............. 27 3

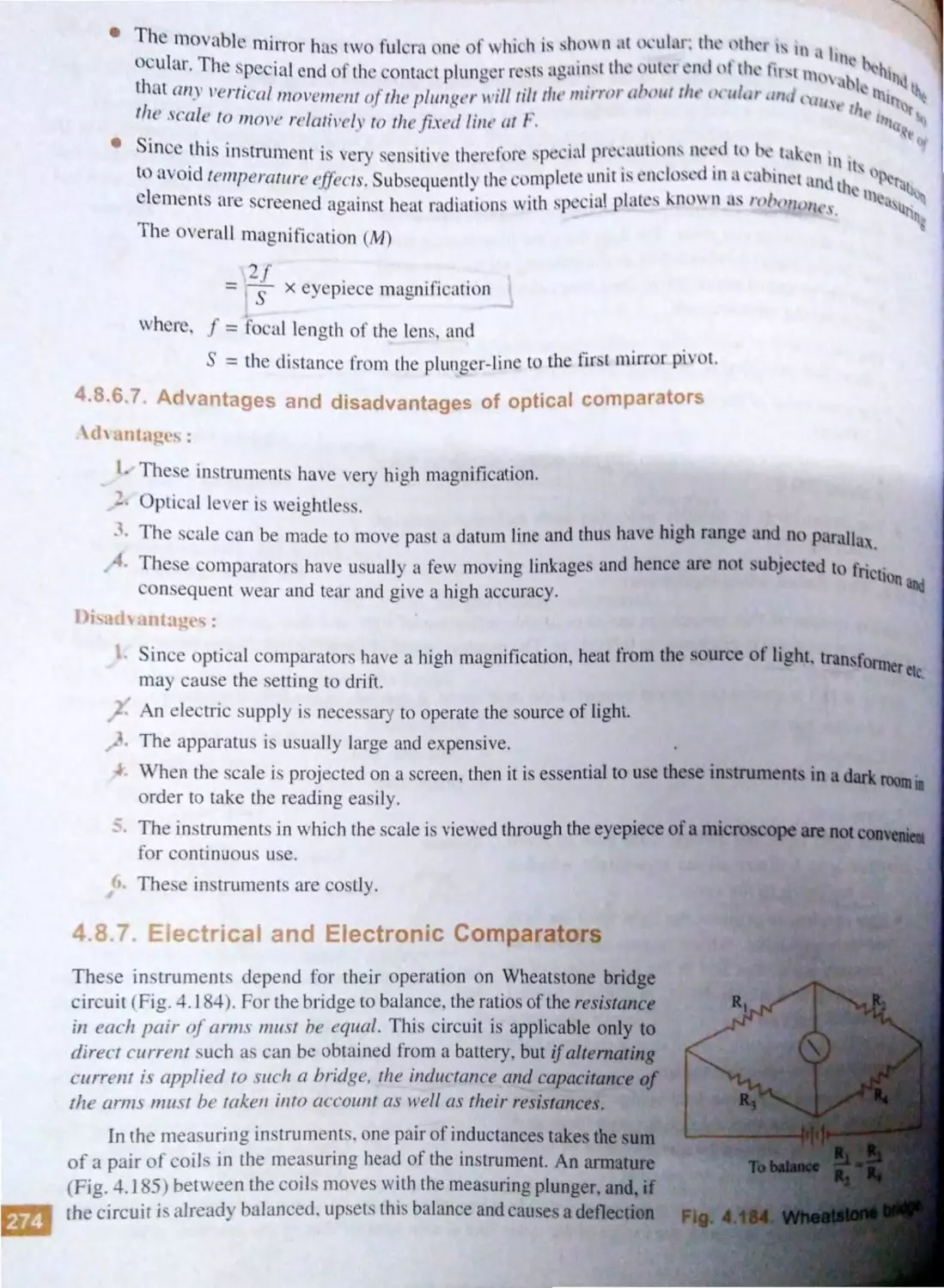

4 ..6.6. The Zei ultra -

optim ter ... .... ................ 273

4.8.6.7. d ntage~ , nd di.auvan-

tage of opti al

c mparat r~ ....... ... ... ...... _7

4. .7. El ctrical and electroni

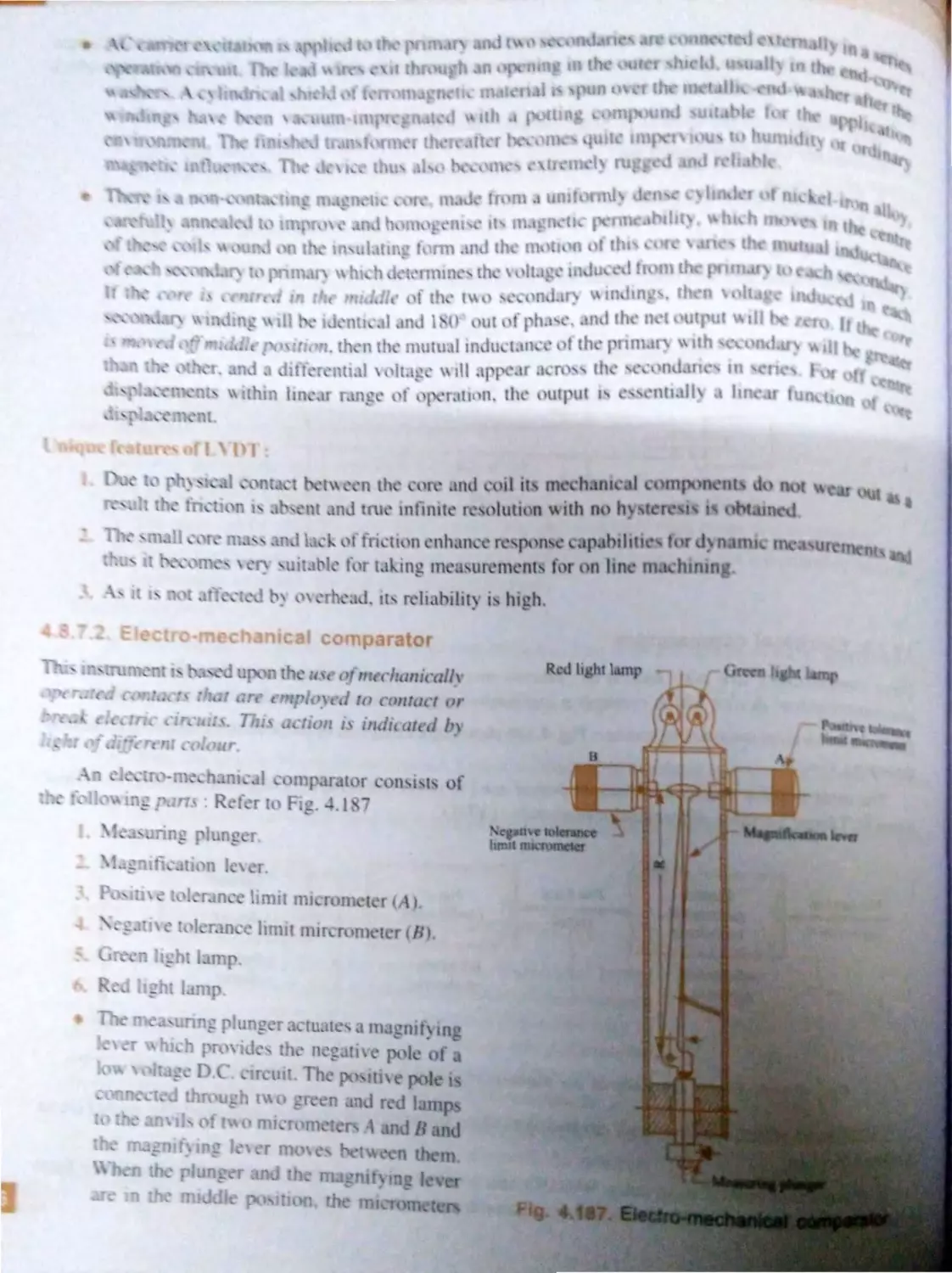

comparator ..... ........ .................. .. 274

4.8. 7 .1. El ctrical comparator ... 27 5

4..7.2 . El ctro-m chani J

comp rat or ... .... ...... ... .... . 76

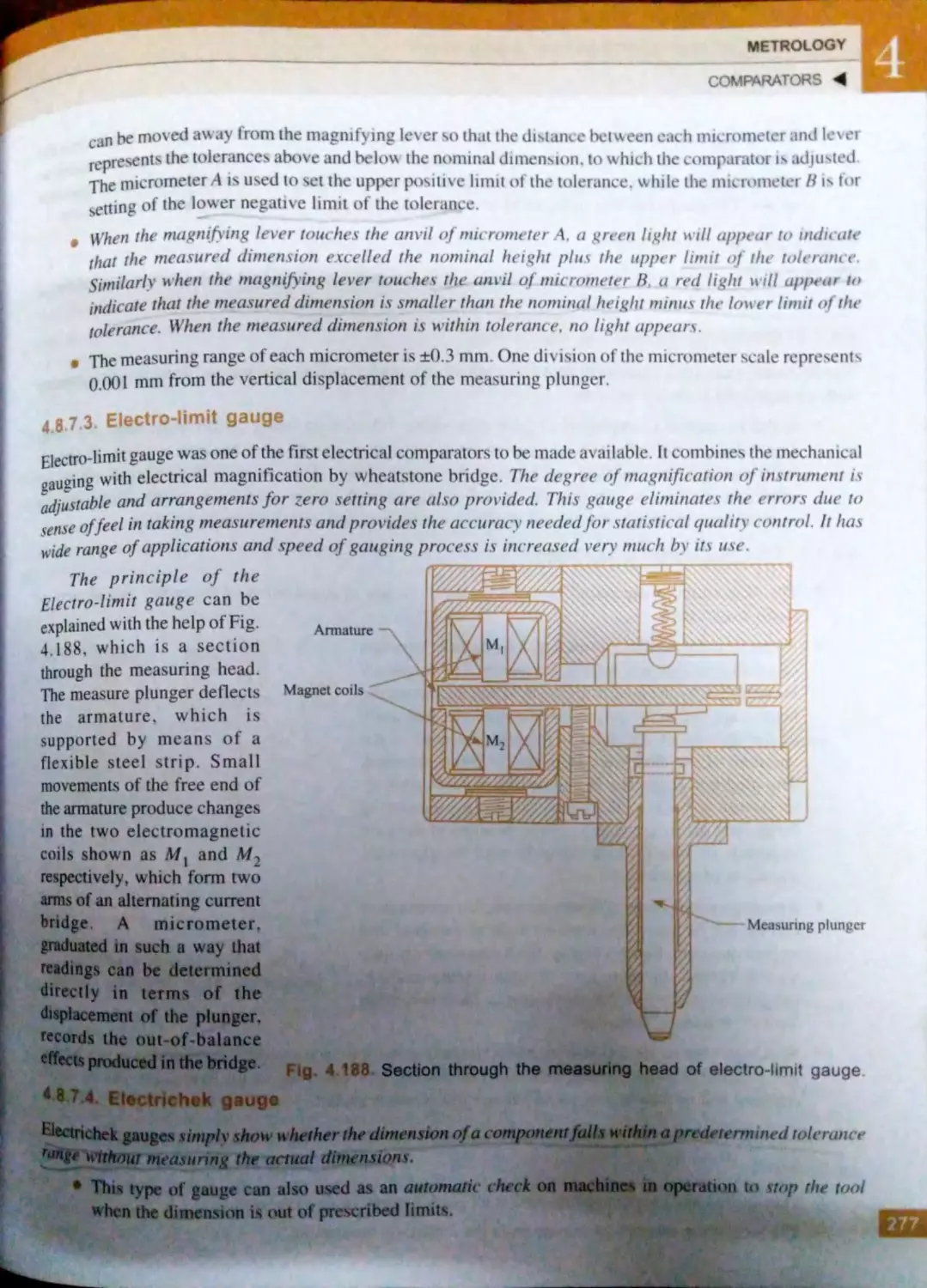

4 ..7 .3. Ele<.· tro-Jimit gaug .. ..... . 277

4..7 .4 . I ctrichek auge.-

. .... .... ... 77

4..7.5.

4.8 .7 .6. lectronic m a uring

quipm nl .... .......... . ... . .. .

..L

fini h

.. .... .

-.t- .9. _. l

- l.9. _ .....

.

.4. h

~·1m e ~n

lcn1th

t> tur

.9.6. lndicati 1n f ·u f

·

mb)I. u

4. .7.

4.10. pti ·al

4. J0. l. lntro<lu ·ri n ................°" •••

. j( ....

. JO.•.

. 10.

4.10.

4. IO._·-·

Itm·ntt.ls<fk..Jt

4.10.6. olJim tor ... ............... ............... 1 ·

4.10. - .

, utoc Him t r....... ........ - ...... ... ..

J11

4.1

.

trJl htne~ ". · fatne, .

quarns,nd

Parnileli m

... . .. ..... . .. . ... . .... ... ..... ......

-. 1l

..Ul.l. In rodu ti n .......... .............. ... ..... 31]

.+.1 l ,l,, .

trai Ohtnes. .................. . .............. _1 Ll

4.11 .2.1. Definition of , traightnc ..

of line in two plan ~.

.. .. 311

4.1 l.2.

.

traight edge ..... .... ....... 312

4 . 11 .2.3. Mea ·urement of

traightn s ..... .. ........ ... 313

4.1 1. 3 . Flatne s ............. ........................ 314

4 .11 .3 .1 . Definition ..... .. ............. 314

4.11.3 .2 . Flatness mea urernent.. 315

4 .11 .4 . Squareness ................................... 319

4.11 .4 .l . Engineer's squares ...... . 3 I 9

4.11 .4 .2 . Indicator method ...... ... 320

4.11 .4 .3 . Autocollimator

methods ....................... 321

4.11.5 . Parallelism ................................... 321

4.11.5 . 1 Different ca e of

paralleli rn of lines

and plane ... ............ ... .. 322

4.11.6 . Parallel motion ............................ 325

4.11 .6 .1 Ca e of parallel

motion ............. ............ 325

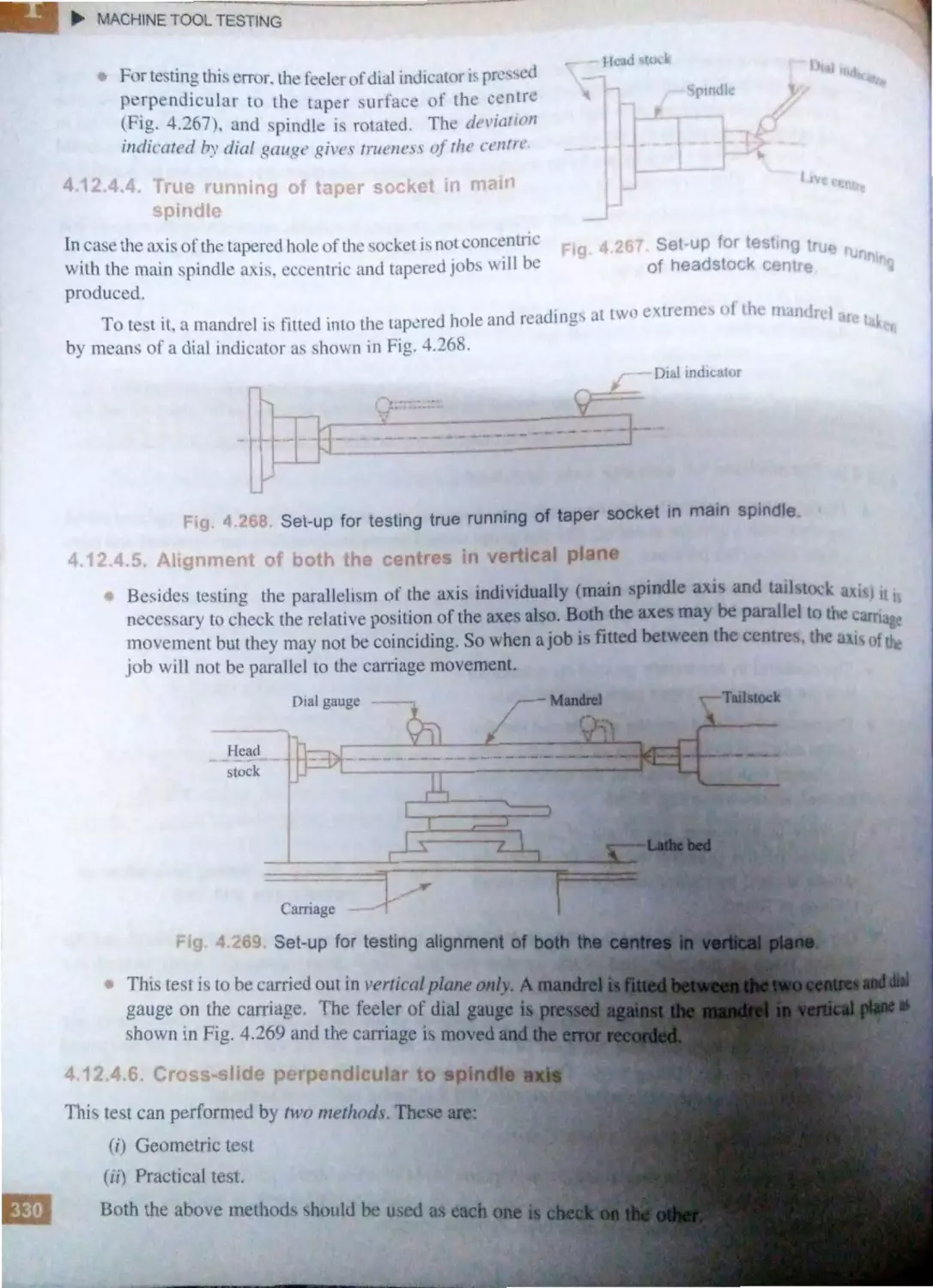

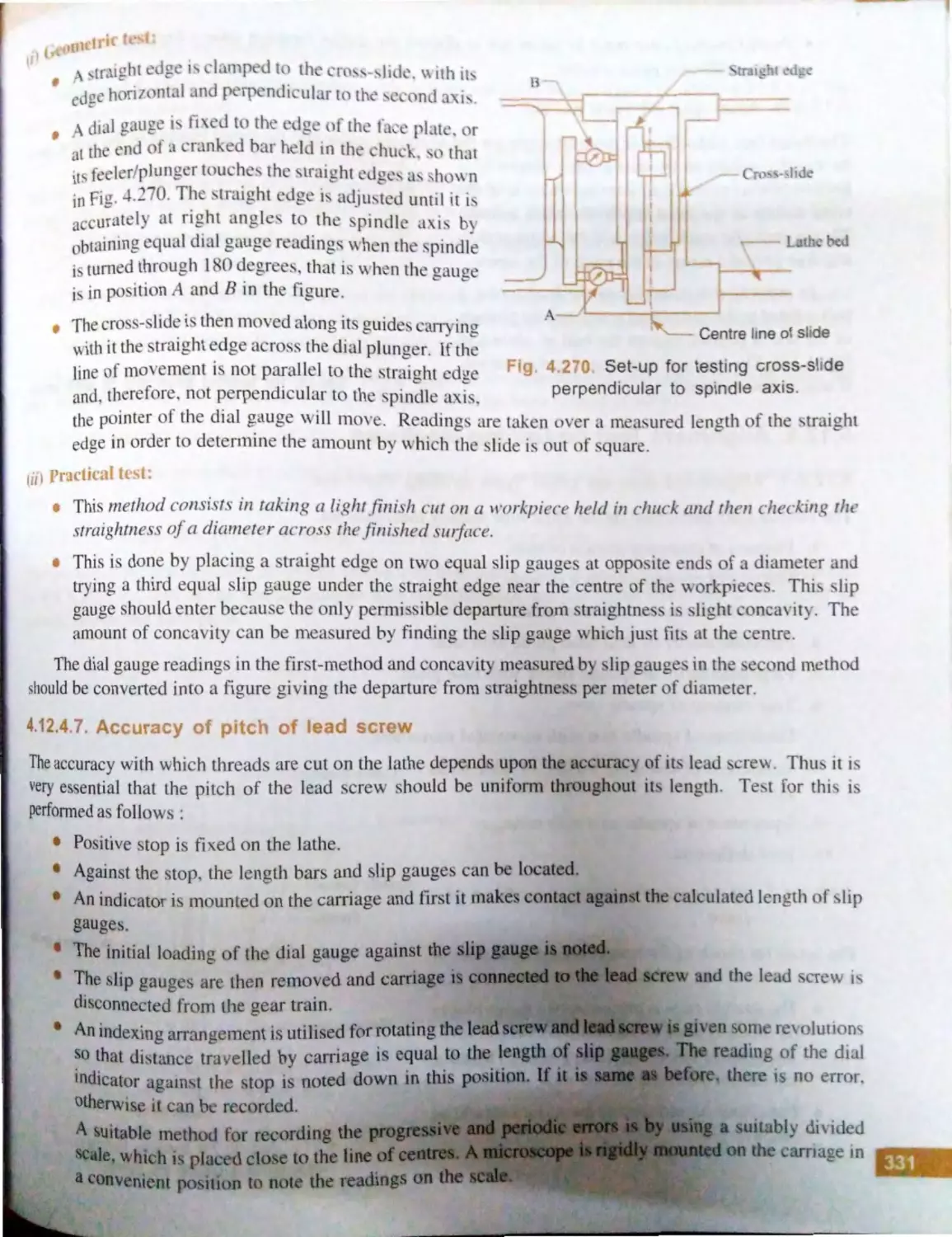

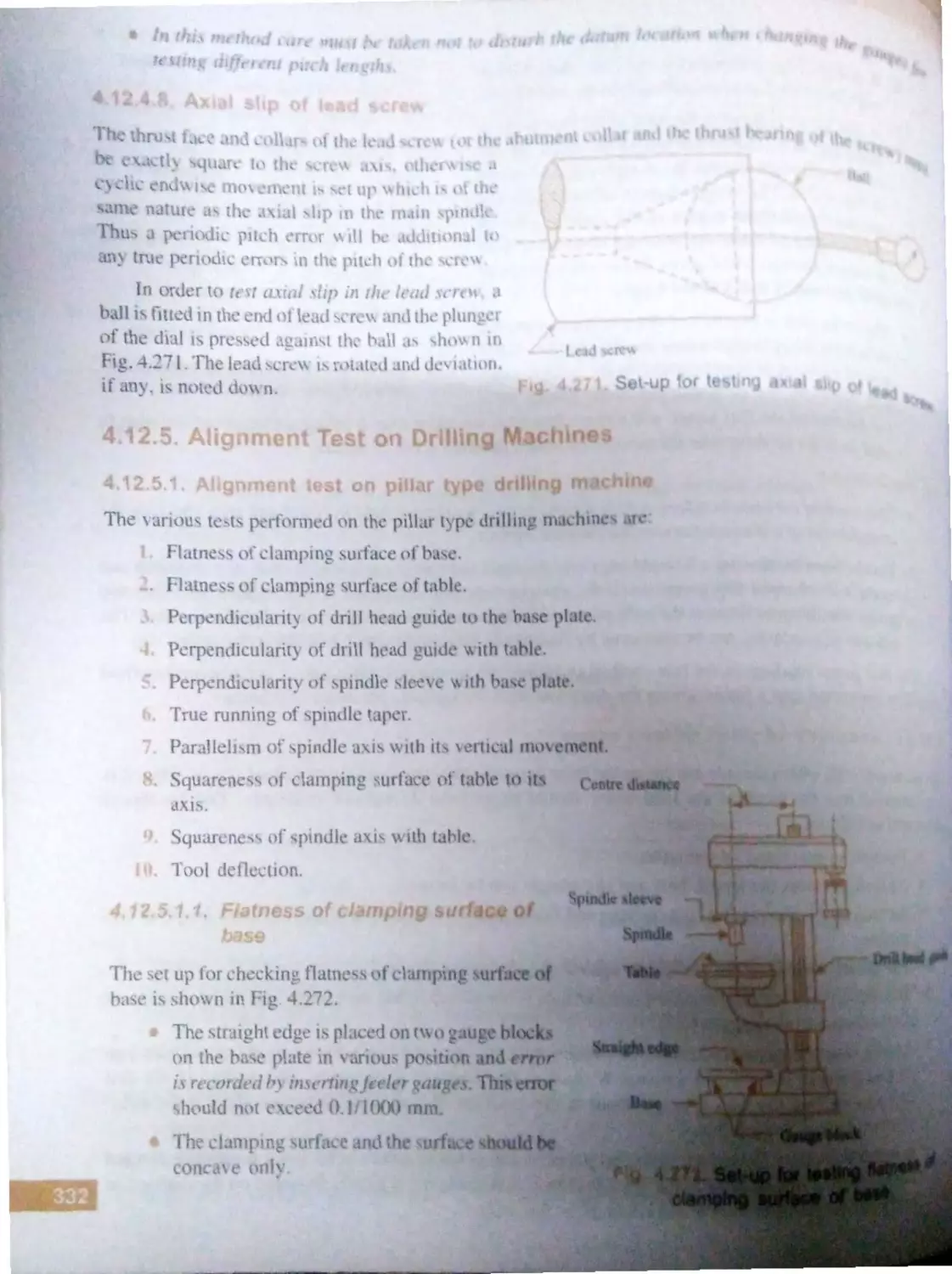

4.12. Machine Tool Testing .................. ... ........ 326

4.12.1 . Introduction ................................ 326

4.12.2 . Machine tool tests ........ ..... ..... ..... 327

4.12 .3. Instruments required for alignment

test .............................................. . 327

4.12 .4 . Alignment tests on lathe ............. 328

4.12 .4 .1 . Levelling of the

machine ....................... 328

4.12 .4 .2 . Parallelism of spindle

axis and bed ................. 329

4.12 .4 .3 . True running of

head-stock centre ......... 329

4.12 .4 .4 . True running of taper

socket in main

spindle ......................... 330

4.12 .4 .5 . Alignment of both the

centres in vertical

plane ............................ 330

4.12 .4.6 . Cross-slide perpendicular

to spindle axis .............. 330

. t 24, . , ( ·ur.c~ol'pnrhJJt

l

4.t ~-

.

ii1{1pl)

It ..lU

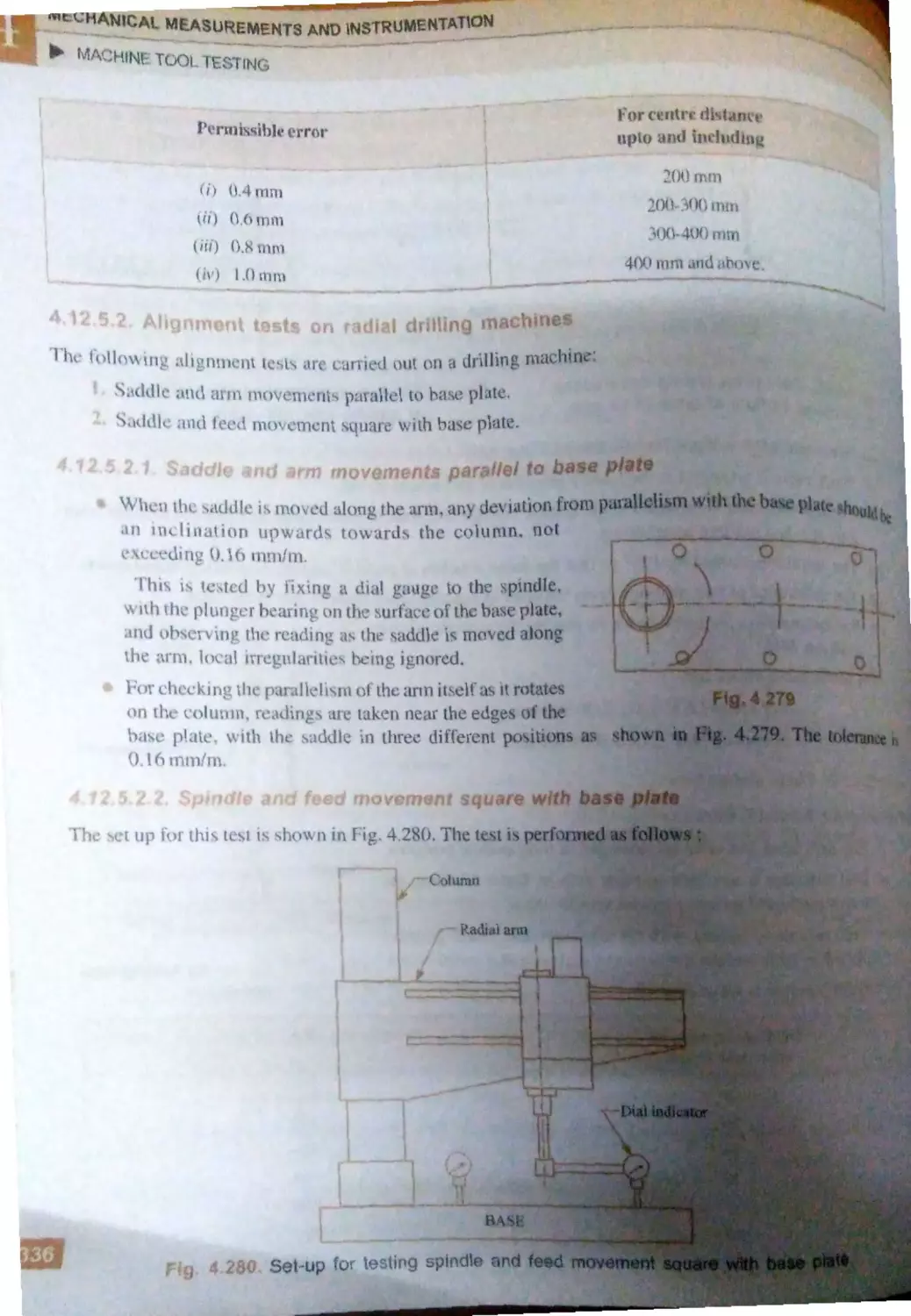

4.12 . . Ali nm ·nt t '"l ()ft dtitf11.1 •

m ·1c hint-;

... ..

.. .. ....

...

.. ...

. ....

-

~ L,•

4. ' - ·~.l. Itrnml'nth onpIIJ1

tYIedillin~madii ..s '

4.l .

·"·

hnm ·n tl ~t nt1r1fial

dnllin<1 rnadltn ·

..... , ..

·J

..J-.1

.6. Iinmnttest\t11

mill in 1 ma ·hin e ....... .. ..... ......... 3 7

4.12.6.l . E~ccntricity ol l \l n .ii

diamet r .. ...... ..... .. ... ..

7

4.12 .6 .2. Tru, unnin 7 of it t 'lll'll

tap r ............... .. .. ..... .... . : ~ !

4. J2.6.3. Work tubl · ~urfac · 1amtk I

with arb r rbin ' tm an.b

overann ........ .. ... .. .... .. ... ~ ~

4.12.6.4 . Surface par~llcl with

longituJinaJ movern ·nt J38

4. l2 .6 .5 . Traver: mov '111 ·nt paraJl ·I

with spindle axi~ . ... .. .. .. ,

.

(J

4.12.6.6. entral T-sll t, parnll •I

with lon gitudinal

mo cm nt .................... ~. 9

4.12.6.7.

ntral T-. Jot square ith

the arbor ...................... . ~ 40

4.12 .6 .8 . Te ·ton column ............ . 40

4.12 .6 .9 . Ov rarn1 pnrall J with

spindle ......................... 341

4.12.6.10. li 0 nm nt f th • main

pindlc with bor of th- .

bracket fth ov rnrm .34l

4.12 .7 . Ac pt ·m t t forsltlface

grinder. ..................................... 341

4. L . . 8 . Practical t sts ........... ................... 342

4.13 . Miscellany

................................. .... 342

4.1

. I . Profile projector ... ........ ...... ... . .. .. . . 2

4.13.2 . Co-ordinate measurin ma 'hin

(CMM) ......... .......... .................. 34.,

4.13.3. Combination set ........ , ................. 344

4.13.4 . Surface plat ................................ 344

4.13.5. Precaution and care/maint n· n

of commonly used measurin

in truments .................................. 4

········ ··· •···· ·· ·· ·" ····· · -

)

n ..... ... .. .. ......... .............. .... ... .. . 7--l

-Trn·du' r

······ ······· · ·•· ····· ...... . ....... .. . . ...... .. ... 75

6

:.4.1.

rtrandu·ere..... _7

El tro-

r

.... . ........

_7

hani.m

.... . ...

0

R·i.tancTra

... .. ...... ... ....... ... .. . 3

0

-.7.1.

p tenti

.. ...... ... . .... ..... ..... ...

.I

5.7.2. Th rm·

nd r :,,j ·urn

therm n1 ters ............ .. ........ .. ....... .

5..3.

· ariab1e lndu tan Tr n , due r ........... .

·-.

.1 . If- n rating type ........... .........

.

. J.1. El tromagn ti · type ... 3

5..1.2. El trod nami t pe ....

_

5.8.1. ~. Eddy urr nt t pe ......... _

,..

. 2. Pru i t_pe .......... ......... ............. 3

5.8 ..l.

'ariablrlutne

tran ducer ... .. ............. ..

-.l

. f ).....

•l,.

•I

..

.,I

~.1l h

:.1. ..

-

. 1• ......

.l~

·.- .

~-. 14. truin

.14.l.

,.l

·-·

11,ortialQ ·

..... .. .... ........

l n oll'ed · ampler .... .....,., . ..... .... . ..

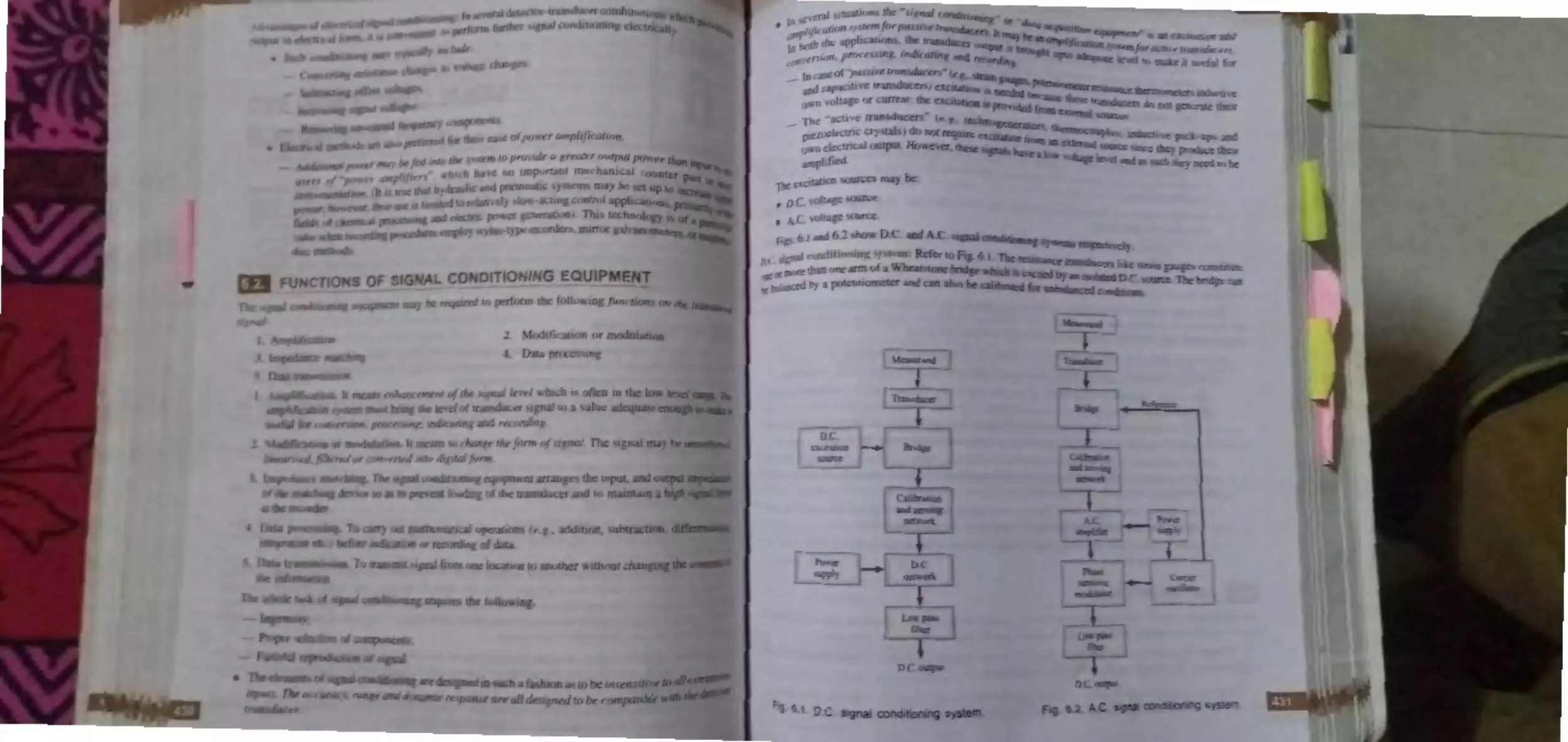

S NAL CO DfOONING AND

OAT. TRANSMISSION .................... 429-454

Intr )duction ...... .. ....... .... .......................... 4 ~9

.~.

Func tion . f Signal Conditionino

Equipment .. .. ...... .. .. ........................... ...... 4 _ O

.

A mp1ificnti n ............. ......................... . ... 432

6A. Ty p , f Amplifier. .......................... ...... . 433

...

1echani al mplifier · ........ ..... ...... .. ....... 433

,<i. Fluid Amplifier.·

...... ..... . .. .. ... . .. ............ .... 433

Opt ic a l amplifier ..... .... .. ... ... ................... 434

6. . Ele tri caJ and EI ctronic Ampli fiers .. ... .. 434

6.8 . l . De irable characteri s tics of

eJ ctronic am plifier ....... .. ... ....... 434

6.8.2 . Electronic amplification gain ..... 434

6. .3 . A .C . and D.C . amplifiers ............. 436

6 .8.4 . Modulated and unmodul ated

signals ......................................... 436

6.8 .5 . Integrated circui t (ICs) ....... ........ 437

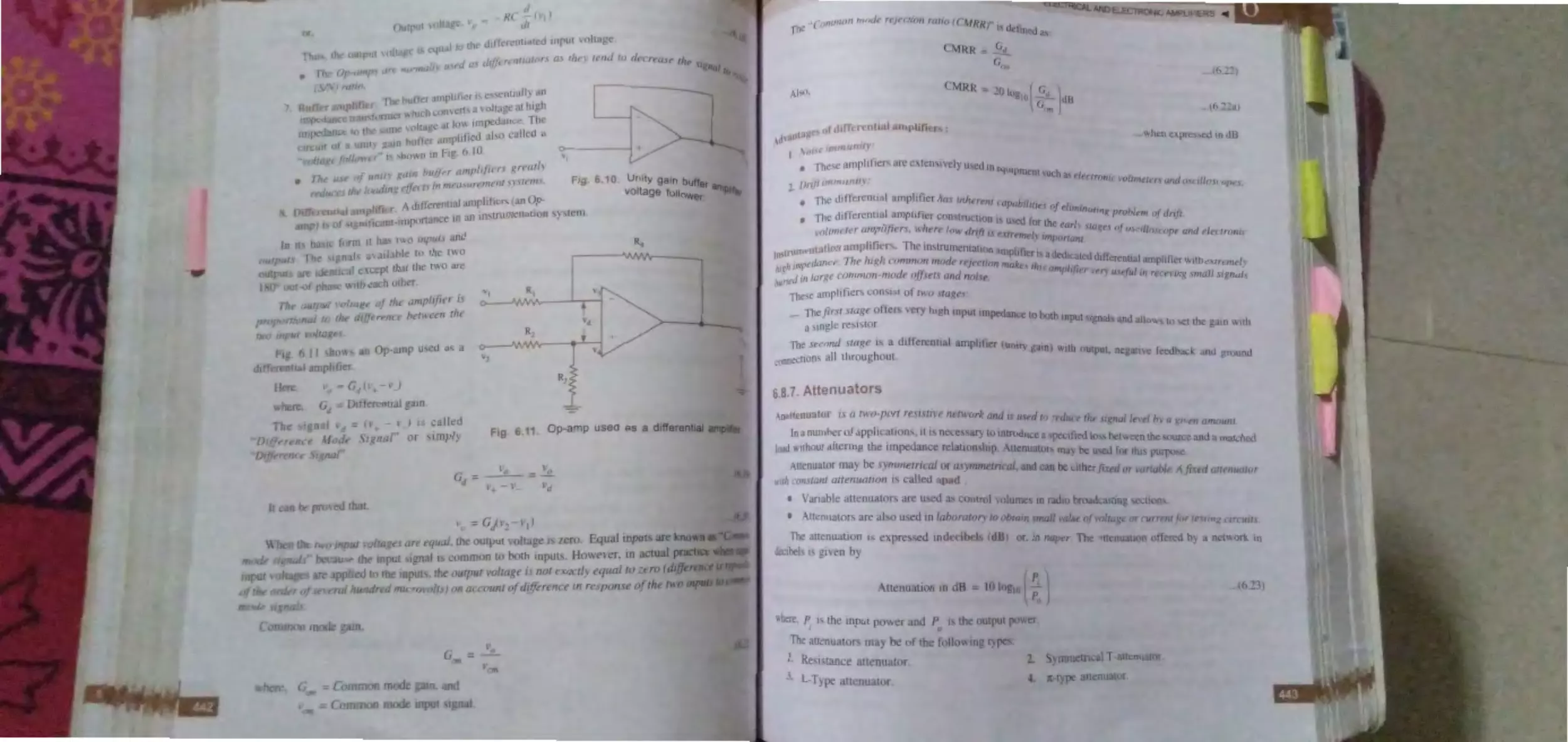

6.8 .6 . Operational amplifier (Op-amp) 437

6.8.6.1. Op -amp description ...... 438

6.8.6.2. Applications of Op-amp 439

6.8 .6.3 . Op -amp circuit used in

in trumentation ............ 439

6.8.7 . Attenuator .................................. 443

6.8 .8 . Filters

.................................. . ...

444

6.8.9. Input circuitry ............................. 445

6. 9. Signal Tran mission ................................ 446

6.9.l . Mechanical transrni sion ............ 447

6.9 .2 . Hydraulic transmission ............... 447

6.9.3 . Pneumatic transmi ion .............. 448

6.9 .4 . Magnetic transmission ................ 448

6.9.5 . Electric type of transmitters ........ 448

6. J0. Converters

..................... . ................ 449

6. ll. Telemetring

.... .. ............... .......... .... ... 449

Highlights

...................................... 450

Objective Type Qu estions ........... ...... .. ..... 450

Theoretical Questions ............. ... .......... ... 453

7. DISPLAY DEVICES AND

RECORDERS

........................ 455-498

7. . Introduction ............................................. 455

7. 2. EiectricaJ Indicating Instruments ............ 456

7 3. Essential Features of Indicating

Instruments .... .......................................... 458

A.

7.5.

CONTENTS xi

•

-1

•

4)9

7.3.l. Ddl etJn_ u ~ 1·e ... .. ..... ...... ... .... .

·

7.3 .2 . Conlrolli~g devic ·s

.. . ... ..... ........

5

Dr1n1p1·n 1 d ~ j~cs .... .. •• .. ·............ ..itO

7.3.J.

-

. 463

nalog l nstrum ·nb ...... ... ...... ••.. .. •..... ·..

7.4 l . Mo ing-iron in trumcnts

( mmcler anJ oltrn t --rsJ ......... 46_

7.4.1 . l. Altrnction type .. ... .. ..... . 4('L

7.4.1.2. R pulsion type ... .. ........ 464

7.4 . 1.3. Advantage<; and disad n-

tage:- .

of moving-iron

in~trumcnt~ ............... .. .. 465

7.4 .1 .4 . Source. of error .......... .. . 465

7.4.2. Moving-coil in . trum nt s ............ 466

7.4.2 . 1. Pe1manent- mag n e l moving-

coil type (PM MC)

instruments ... ........... ..... 466

7.4.2 .2 . Electrodynamic or dyna-

mometer in truments .. .. 473

7.4.3. Rectifier instruments .............. ..... 477

7.4.4 . Wattmeter ....... ..... ...... .............. .. 479

7.4 .5 . Megger ...................................... 480

7.4 .6 . EJectronic in ulation te ter ......... 481

7.4.7 . Multimeter (AYO) ........... ............ 48 l

7.4 .8 . Electronic voltmeter ............... ... 482

Digital In trument ..... .... .......... .. ............. 483

7 .5 .1 . Light emitting diode (LED) ........ 483

7.5.2 . Liquid crystal di pla (LCD) .... 4 5

7.5.3 . Numerical indicator tube (NIT). 485

7 .5.4 . Hot film bar tube ..................... ... 486

7.5 .5. Digclampter ................... ..... ...... ... 486

7.5.6. Digital tachometer for r .p.m .

mea urement. ................. ........... .. 486

7.6. Recorder ................... .. ........... .......... .... ... 487

7.6 . l. Types of recorders ....................... 487

(

7.6.2 . Strip chart recorder .... .... ............ 487

7.6 .3 . X -Y recorders .............................. 489

7.6.4 . Ultraviolet recorder ................... 489

7.6 .5. Magnetic tape recorder .... ........ .. 490

7.6 .6 . Cathode ray oscilloscope

(C.R .0 .)

....................................... 49 l

Highlights ................ ............. ................... 494

Objective Type Questions ........................ 495

Theoretical Questions ............................. 498

····· ····· ........ .... .

•

•

•

•

..

..

•

•

•

•

•

..

•

•

••

•

~....f

......... ......... .

~ ••••

Jl tlTl( !Tlt..'l I .. .............. ... ..

·

n ial m·m m1Ltcr. ...... ..... .. .

/.J .: . M till m ·tric Ii 1u1d ......... ............ 5 J

__

. 4. 1 - d antao ,~ dnd limitation >f

n an )111 tcr ................................. :- 1 -t.

Bell Gau~

-..

........ ......... . ...........................

514

8.:. M chanical Ciuuge<-.

................................ . 5 14

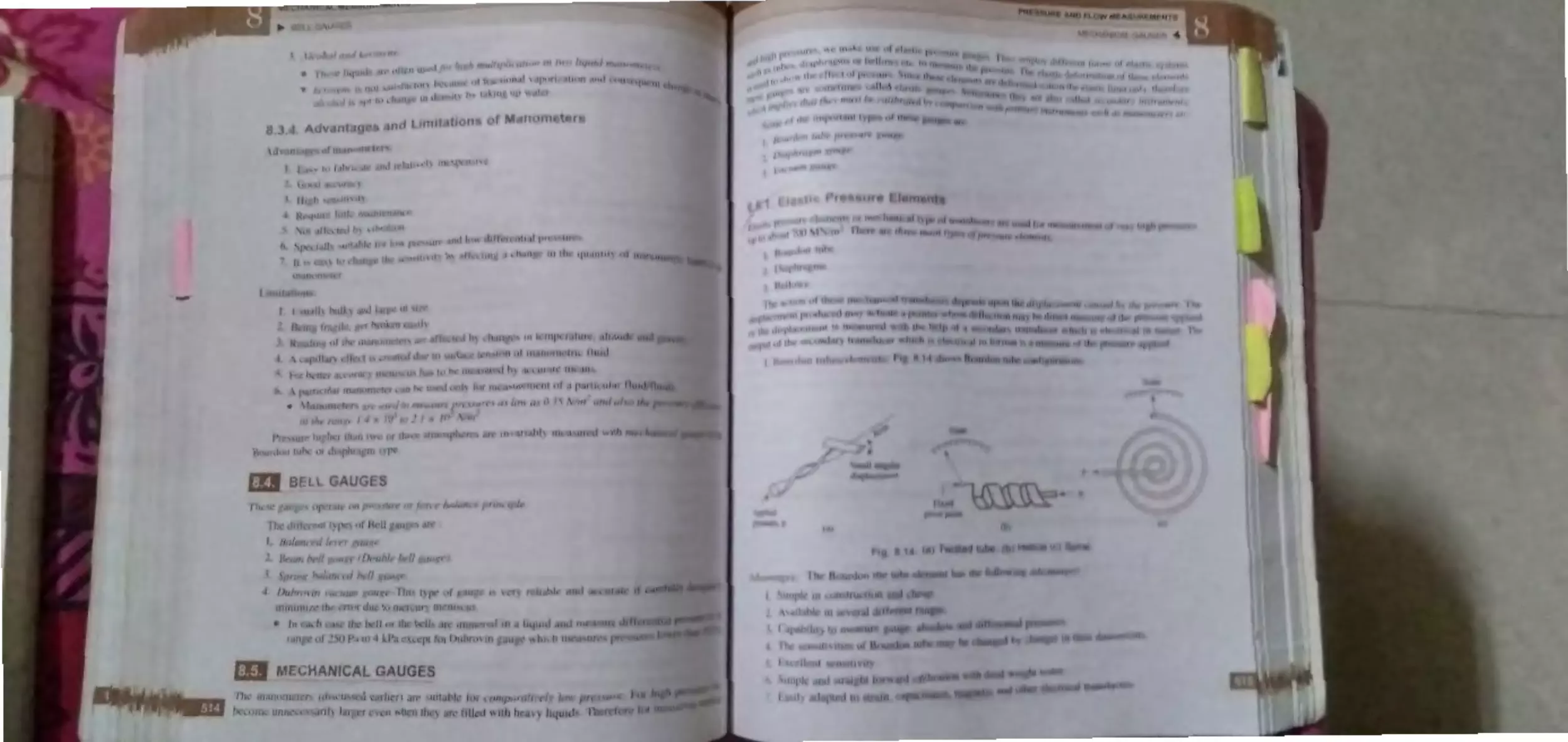

8.5. l. E!a'-;tic pre~ . ure de, 1c1 t\ ............ : I :'i

8.5.2 . Pre . ·urc g:augc1.,

..........................

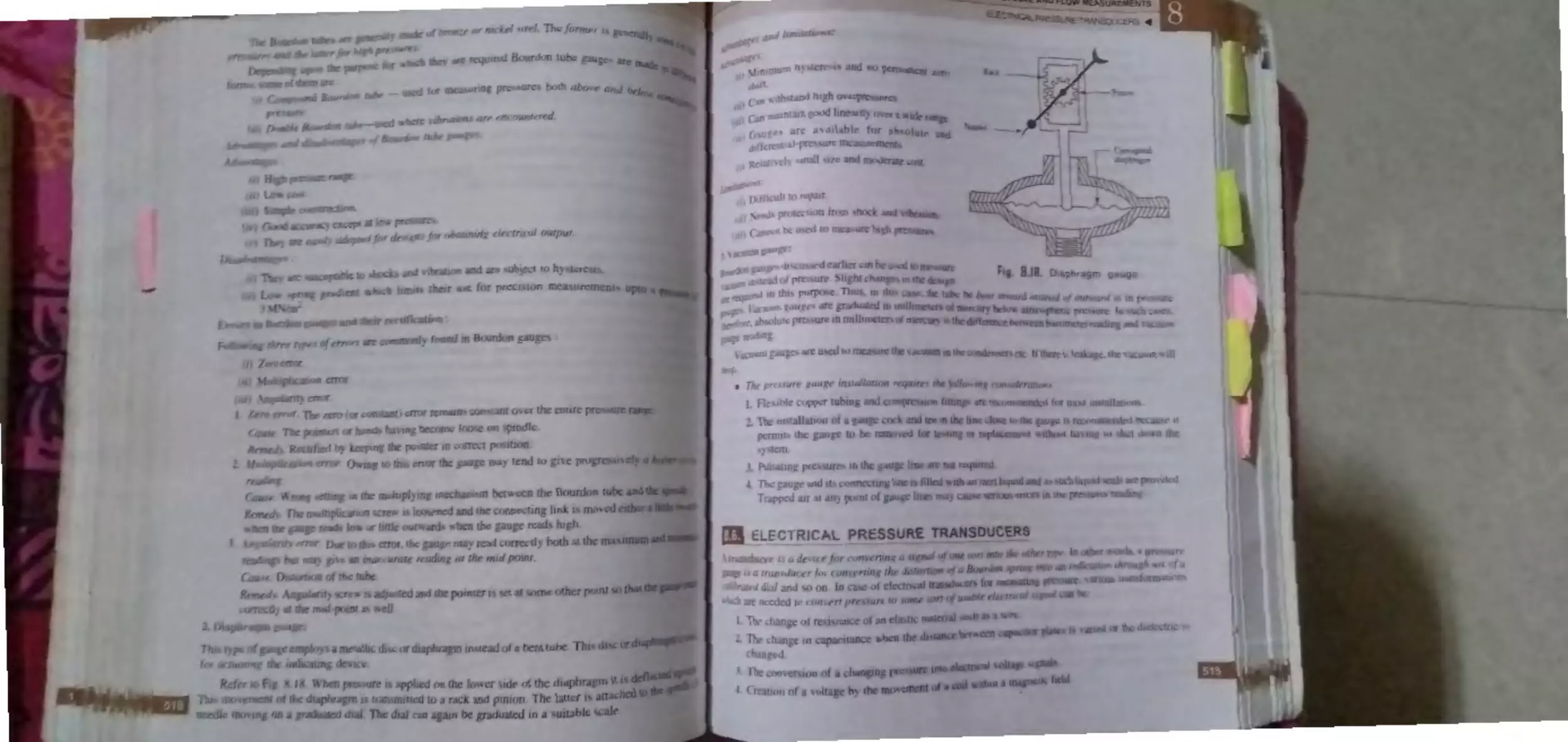

517

8.6. Electrical Pr s ure Tran- .duc ·r -,

..... ... .......

5I<

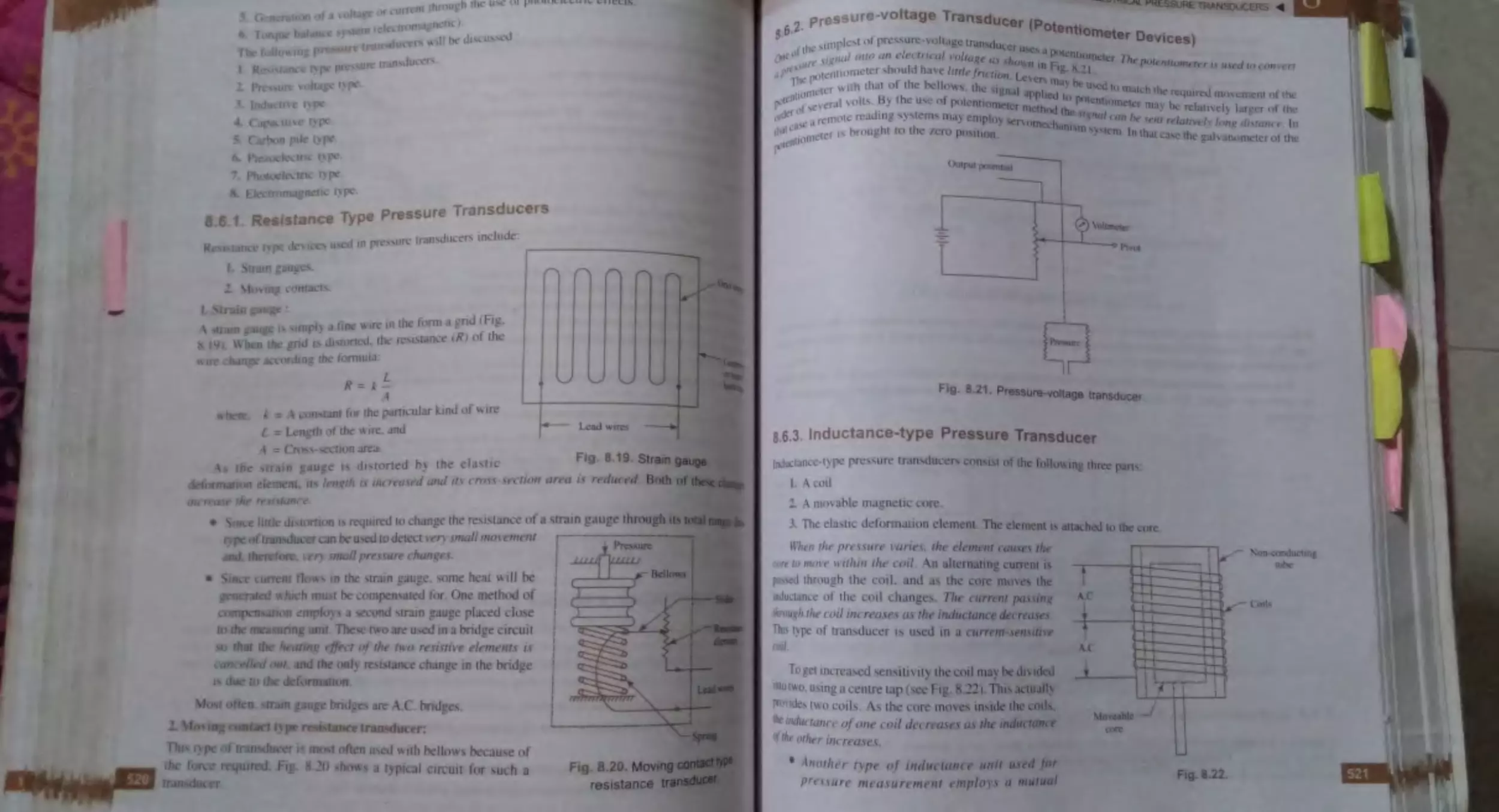

8.6.1. Re...,i. lance typ · pres ur~

tran du ·er...,

..................................

520

8.6.2 . Pressure-, olt, ge transducer~

(Potentiom ter de ic s) .............. 521

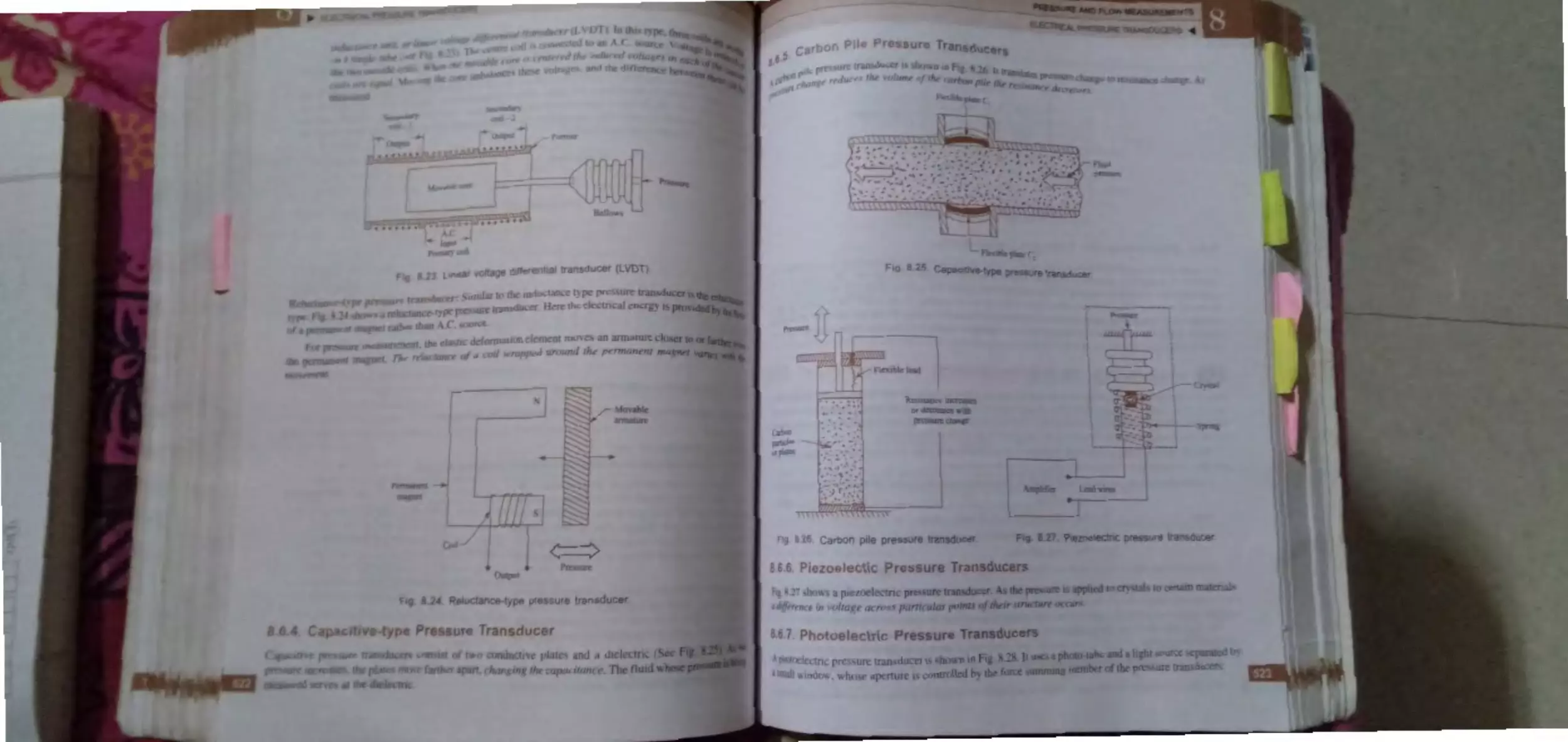

8.6.3 . Induct:.mcc-typ prcssur

transducer .................................... 521

8.6 .4 . Capacitiv -type pre:surc

tran . ducer ..................... ..... ........ .. 522

8.6 . 5. Carbon pipe pre. sure tran ·ducer. 523

8.6 .6. Piezoelectric pre. sure transducer 523

8.6.7 . Photoelectric pre. sure

transducers .................................. 523

8.6 .8 . Electromagnetic pres. ure

tran . ducer ..... ... ... ... ... .. ........ ... .... 524

8.7 Measurement of High Pre sures ...... ........ 524

8.8. Mea urement of Low Pre~su re (Vacuum) 52

8.8.l. Mcleod gauge ......... ..... ............... 526

8.8.2 . Thermal conducti ity gauges ..... 528

8.8 .2 .1 . Thermo ouple vacuum

gauge ............................ 5:...8

8.8.2.2. Pirani acuum gauge .... 529

8.8.3. Ionization gaug , ........................ 5 0

8.8.4. Radioacti c acuum meter ........ 5 _ l

8.9 . CaJibration of Pressure Mea urino

E.

quipment ...................................... ......... :3 l

8.9.1. Manometer~ ...... .. ............... ........ ..

-

l

8.9.2. D adw i...,btte,t ·r.

.... .......... .......

~31

• R<tamtc.ran

.1 . r otamet

8.I

.2. Elh \\. mek r ... ... .................... .. : .

.1

.

El 'ctrom·

_ncti·l\

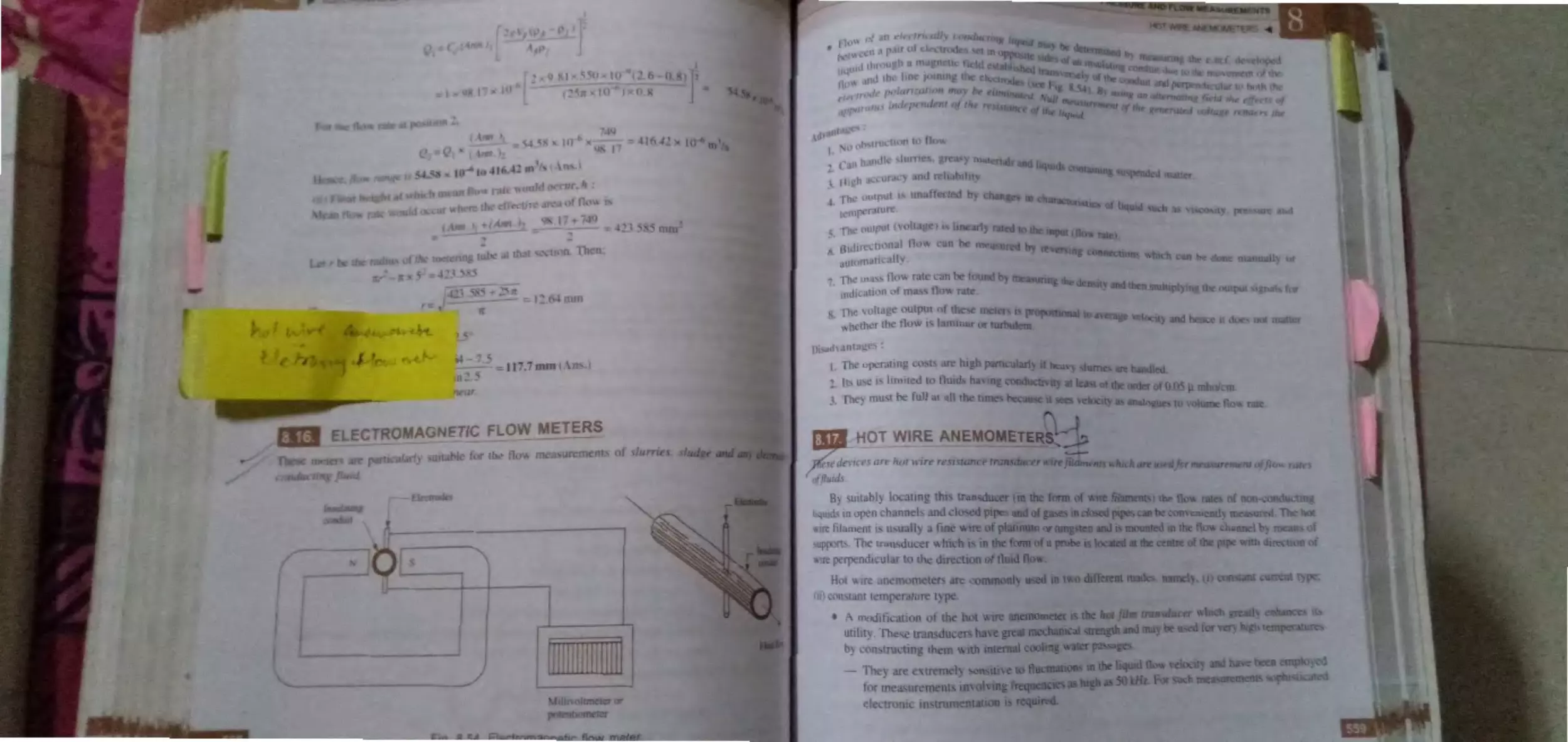

H.17 HotWjre

)lll t·r

..........................

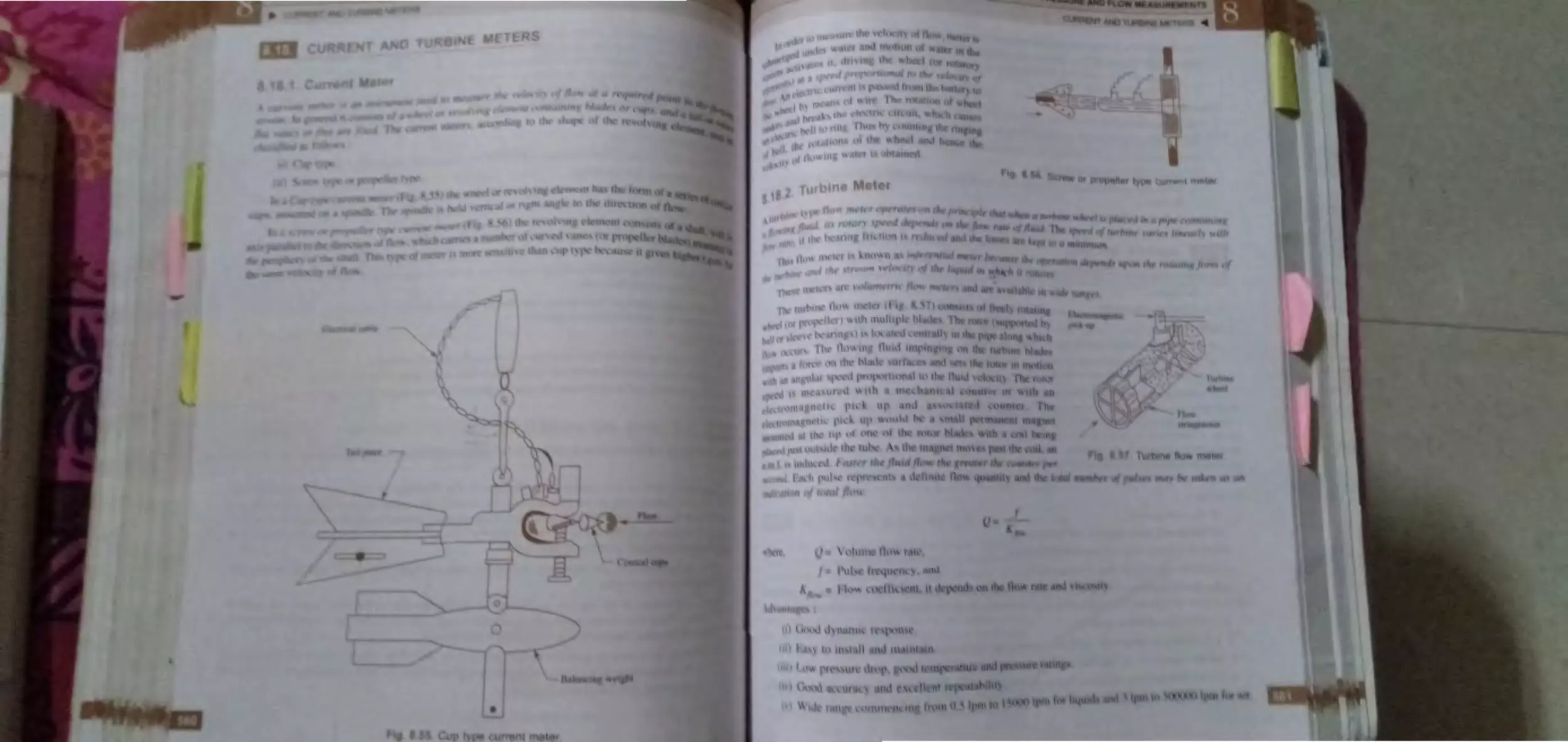

8. Cum.-: nt and urbin Ill\.:

·r

... ....... .... .... ..

8.1

. 1. Cu ff n m t "r .. ...... ........ .. ........ ... 60

. 18.2. Turbin n

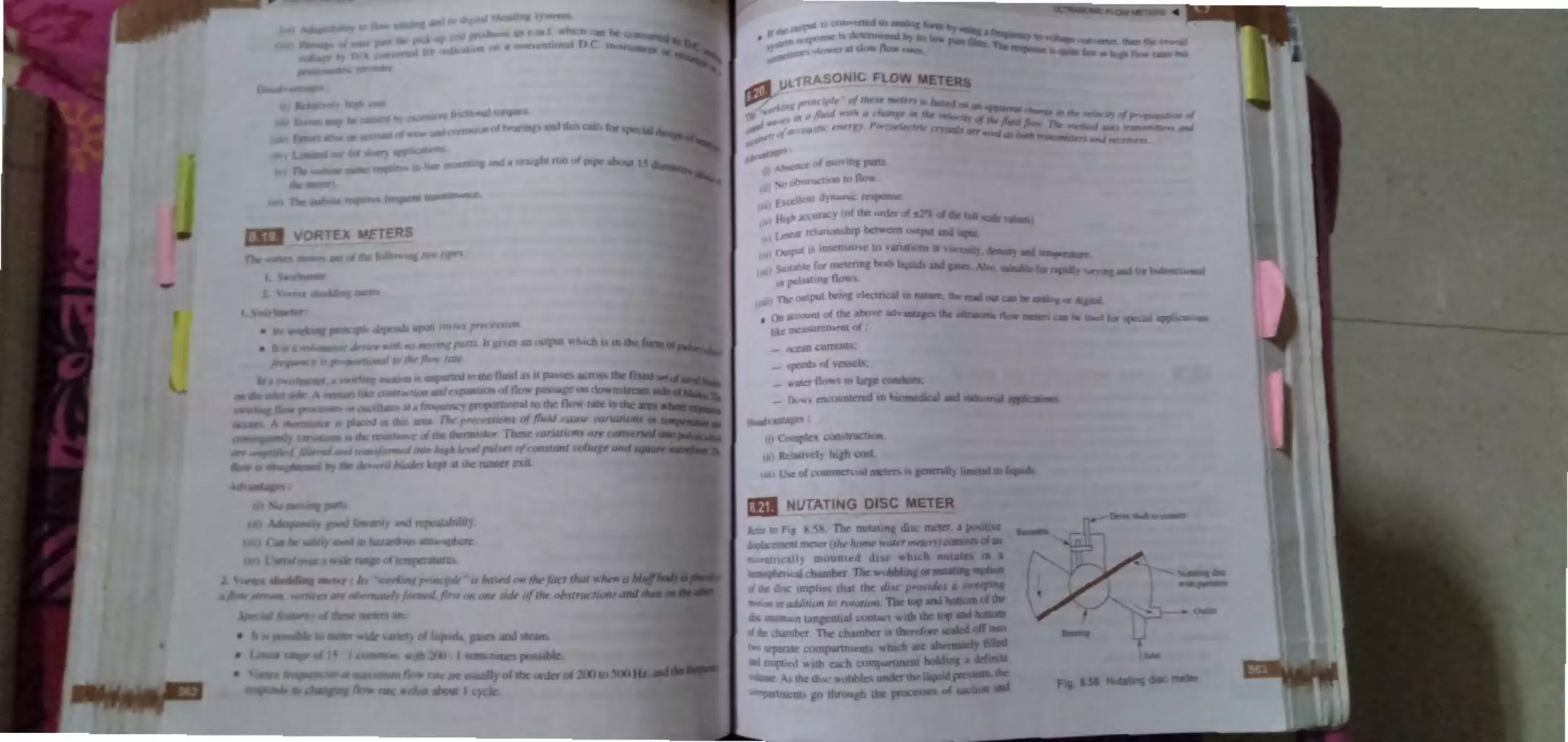

8.19. ort' ·, ete r: ...................... .... ............ ...

8.20. ltra~ nic

tt!r ...........................

8.21. utating

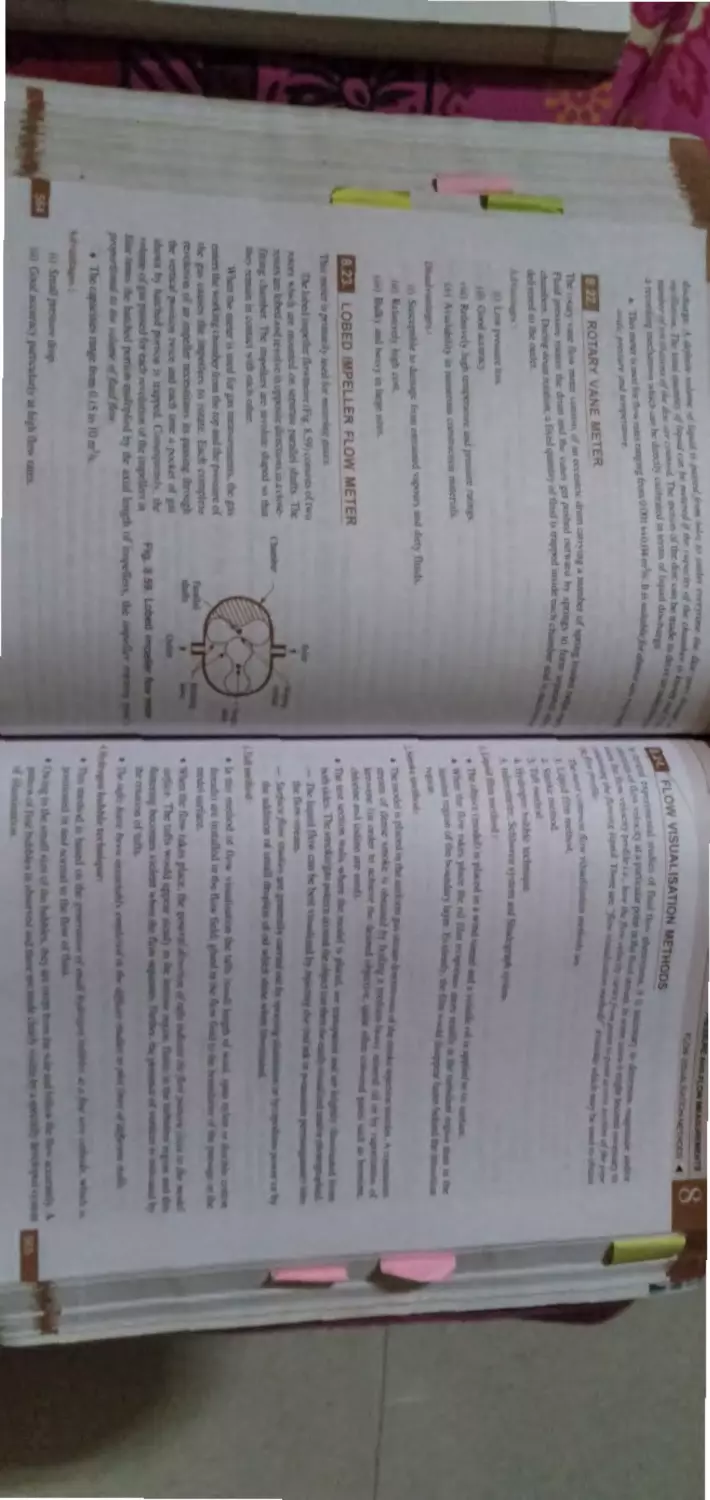

er ......... . .................... .

8.22. Rotary Van

r ................................ ..

.2,.Lbeum

.................. ...

8.2. Flow \i ·u

~ ...................

·ti:

Hi1;Jz/;ghr · ... .......... ................................. .

Tlicoretil al

Un:ofr d E.wmplcs ......... .. ...... .............. . , 576

9. TEMPERATURE

MEASUREMENTS

9.1. Introduction ..... .. .... .. ............ .. .. .., .. ... .... ... 571.J

9.2. The lnt rnational Pra 'tiv I ·mp )r, tur

Scale ........ .. ...................................... , . . . .

()

9h . T "mperJture

9.

.

E ·pc.m ion Therm lm kr .... .. .......... .......

9. .1 . Liquid-111 -0 "

r ..... .

9.

·-·

Bi t· lli

et t ............

Pr~ .ureTh rm 11ct r ............•.... ... .... .. .. :

t .5.1.

ur pre ur tlkrm

r .....

l.

·-·l..

:)

)}

l)

·· ·· · ·· ·· ·· ·· ·· ·············

{,t) l

. .. . ... ............. ... ( {) _

'lll~l(

.nit1 )fl, in

07

1(7

. , · ·· · ·············· 610

,·,,·

... . ....... .. ... ........ .........

6ll

.... ....... ..... ................ ..

1_

QUE

........................ 617-646

I..

0

J••.•

0. ),

CONTENTS xi

I(). _. ~

f . •1LL'h ni ·.11 ta~hom~tcr 6- 1

10.2. -

~.1

.., 1• ·tricdl tach 111 'ler .. 62...,

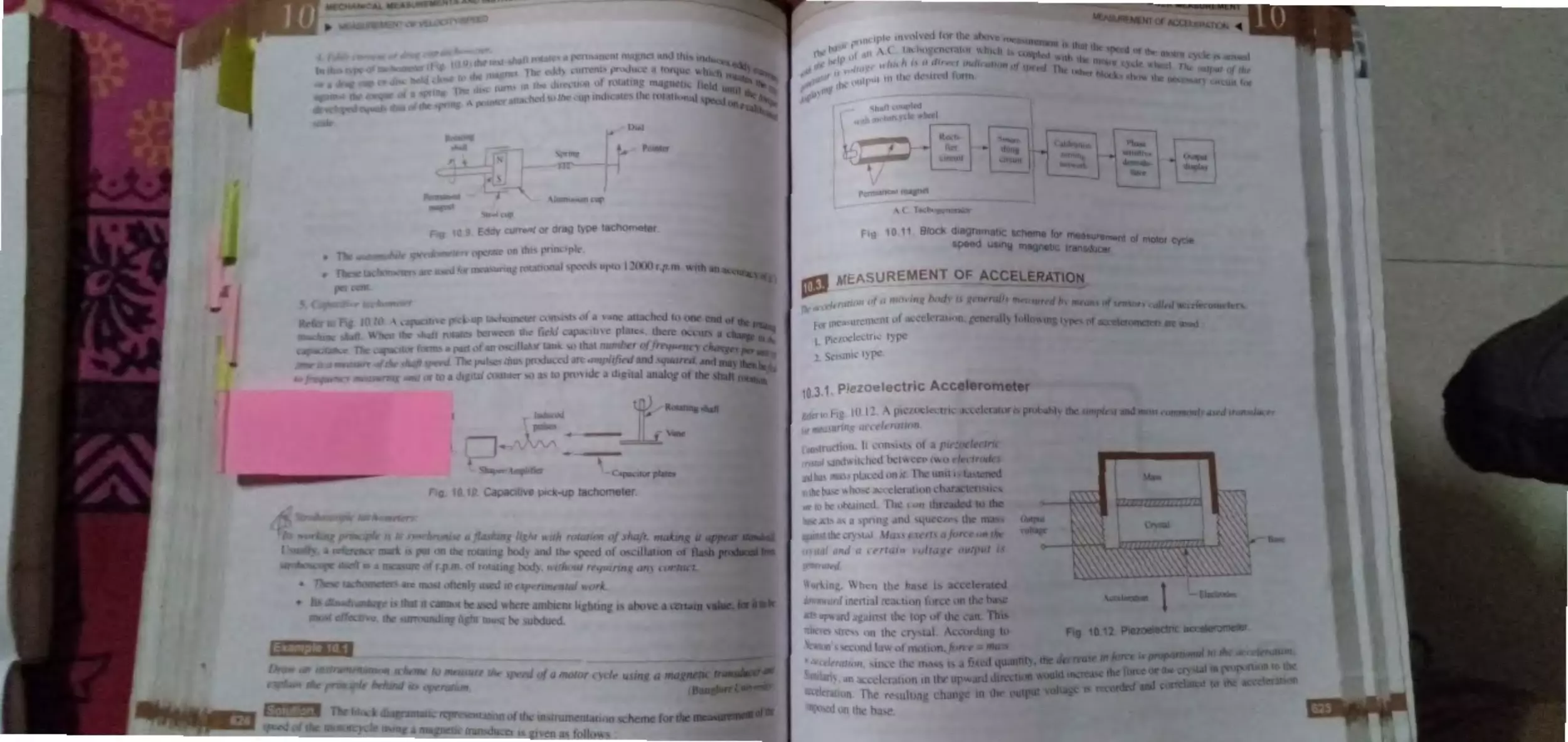

. k .1~ur 't1kn nf, ccdcration .......... ... ... 6- -

HU. I.. Pil•,w :I ·t.:tri • ·1c ·elcromet ~r ... ..... 6 _5

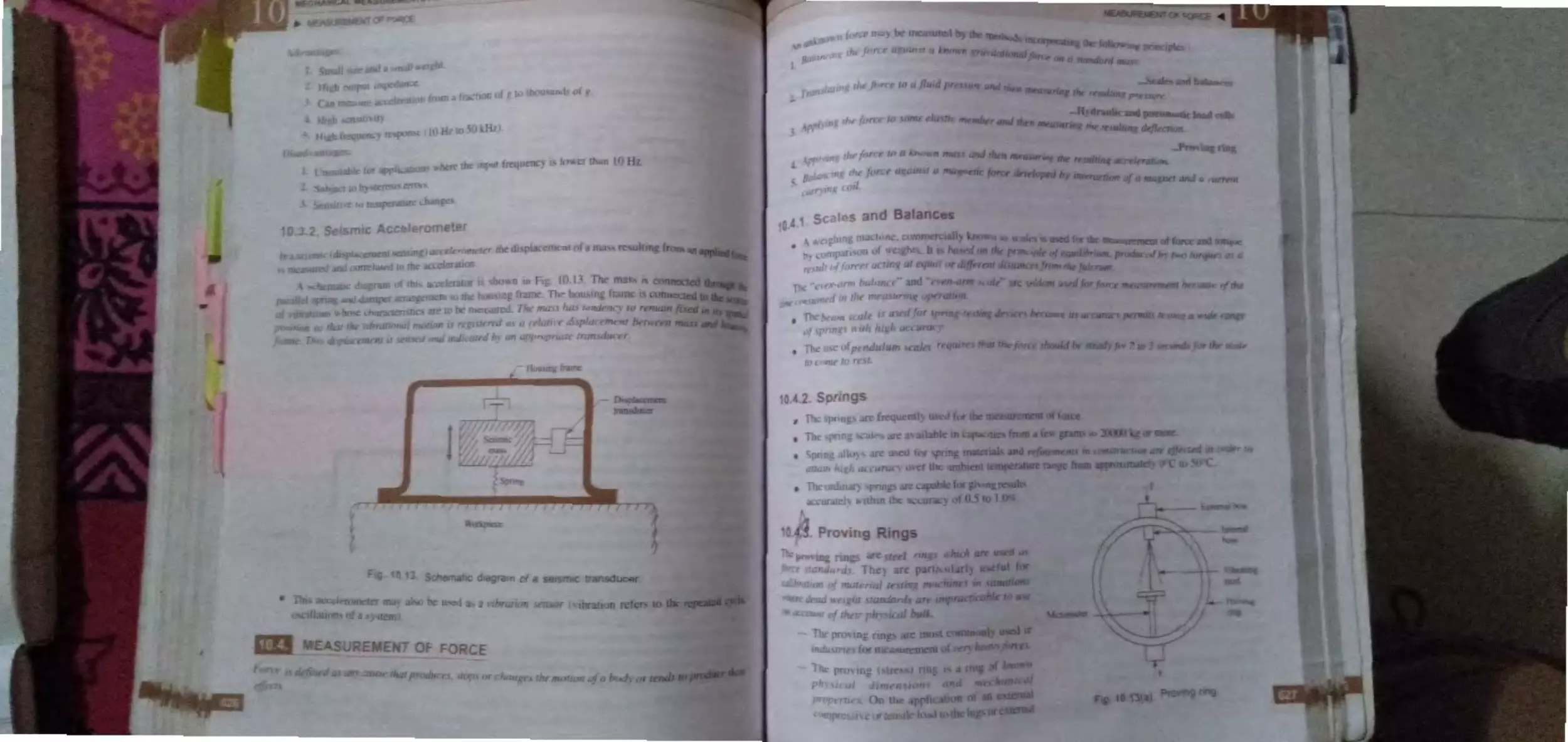

I0. · ..... . S •i:nu ttLcekromctcr ......... ...... .. 626

M';I, Ult'lll nlorhm: · ............................. 6_ 1

W.LI . S ·al :-, a11d halane·

.. ...... ...... .. ... ..

627

10. .2.,' iinp:~

.. ... .. ..... ...........................

6-7

·

6~7

ln...i .. . [ rO\,lllg rrng~ ... .. .. .. ... . ......... .........

-

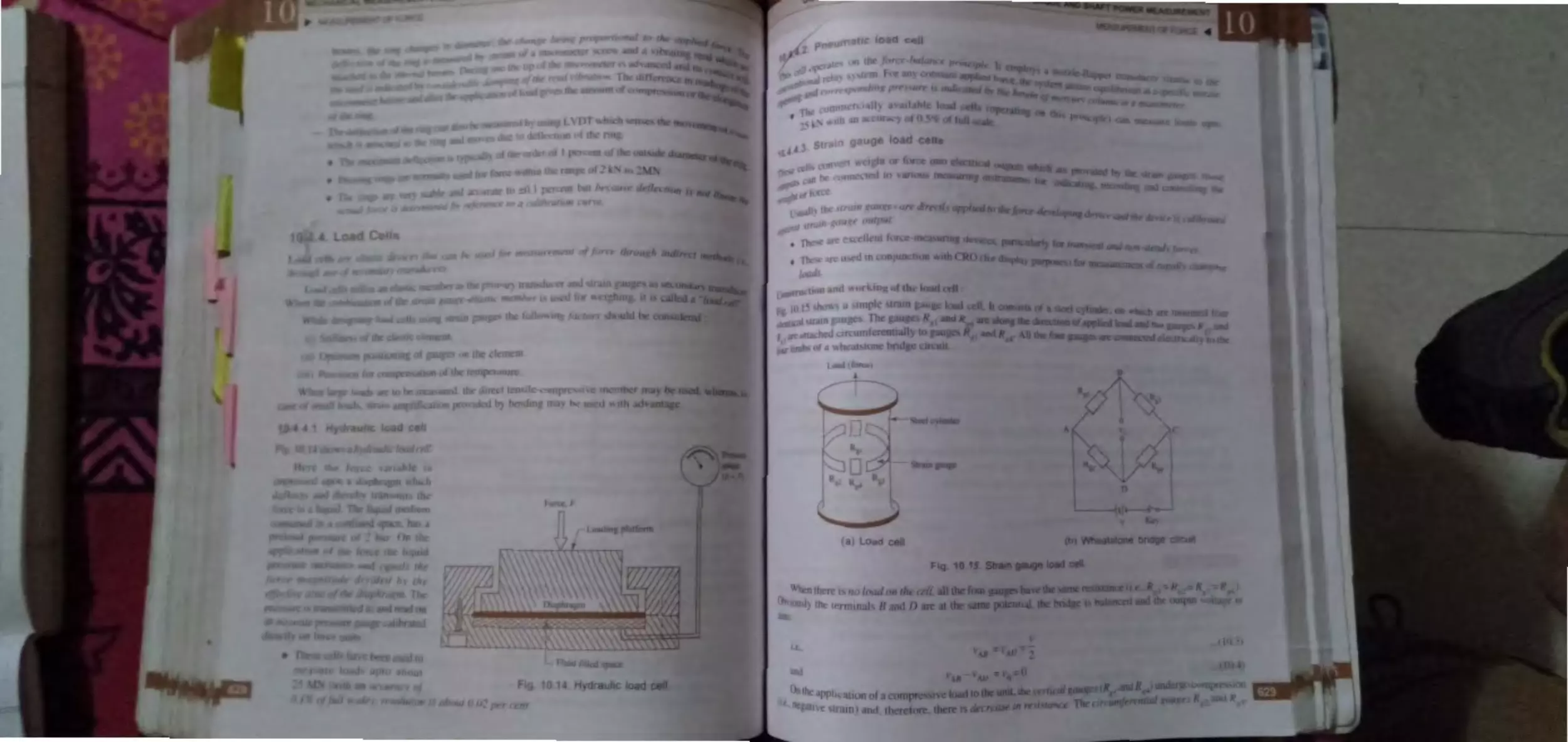

I 0.4 .4 . l t ad c It. .. .. .. .. ...... ........... .... ....... 62c

10.4A. l. Hydrnulic load c JI ...... 628

I 0.4 .4 .2. Pncnmaric load celJ ...... 629

I0.4 .4.3. Strain gauge load cells. 629

l0.4.4.4. Piewelcctric load cell .. 6 2

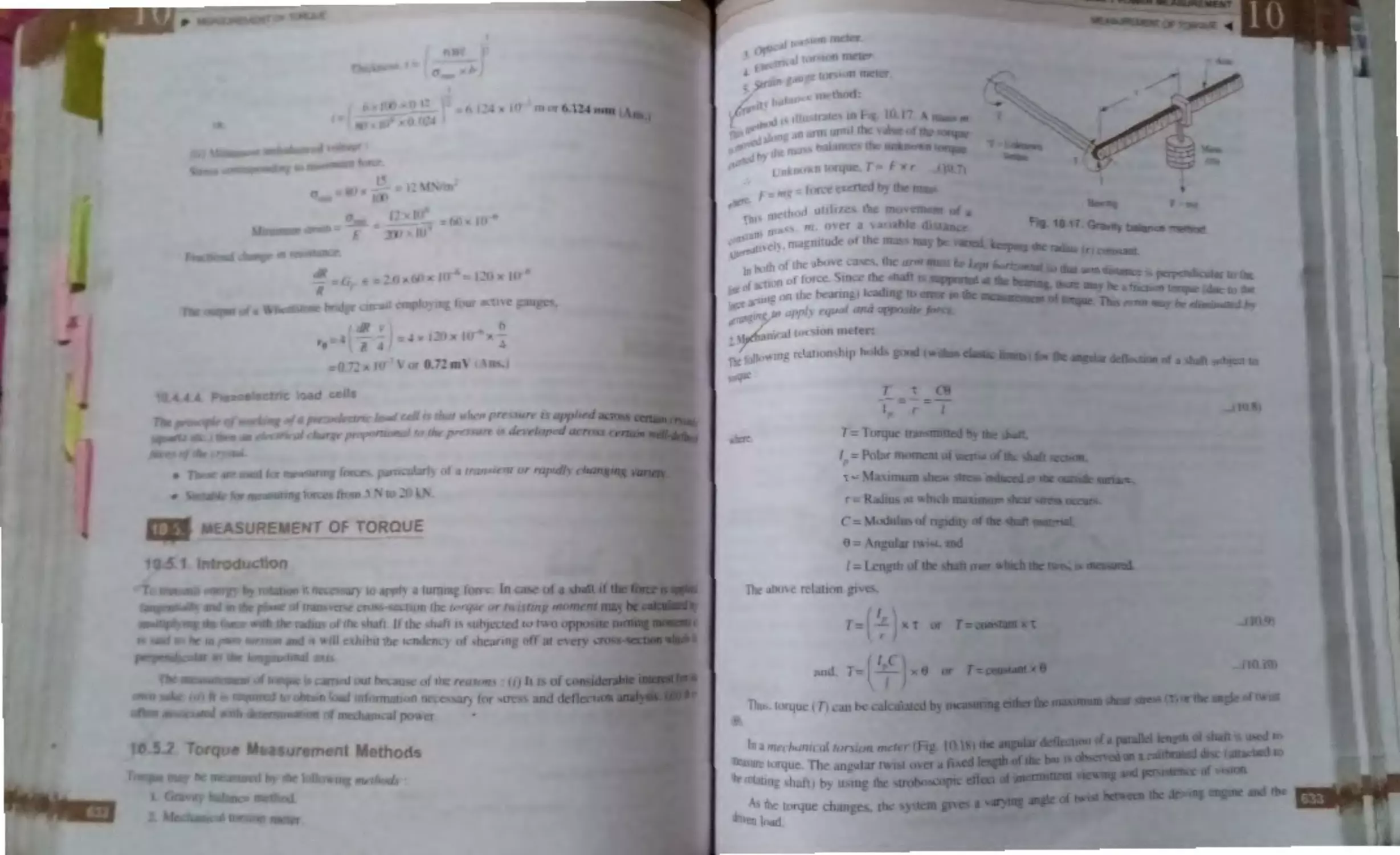

M ~,1 , ur 'ment of Torque .... ............ .......... 63 2

I0.) . l . Intr duction ............................ .. .. 6. - ,2

10.5 . ~ . Torque measurem nt m thods .... 632

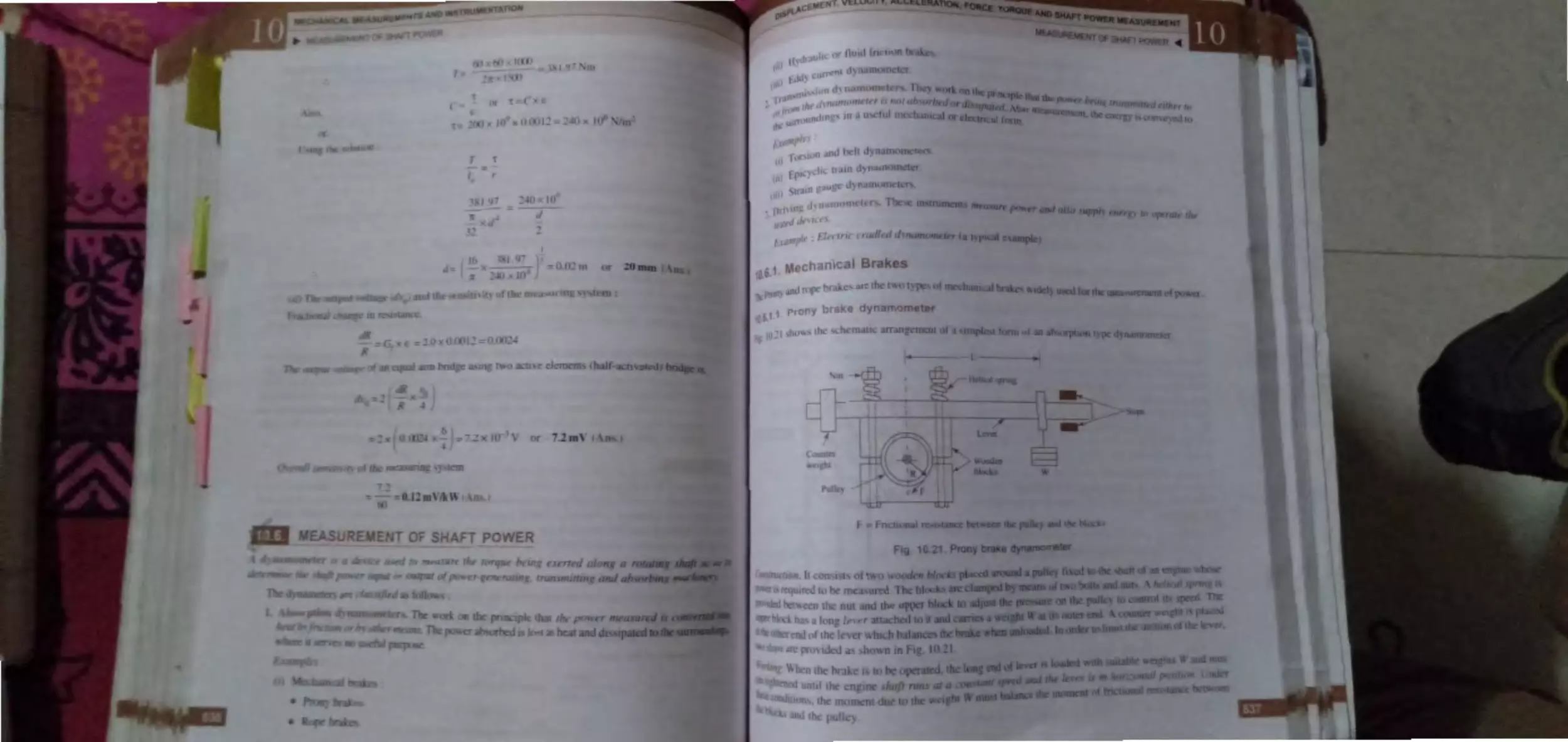

Measurement of Shaft Power ..... .......... .... 636

I 0.6 .1 . M chanical brake, ...................... 63 7

10.6. l . l . Prony brake

dynamom ter .. .............. 63 7

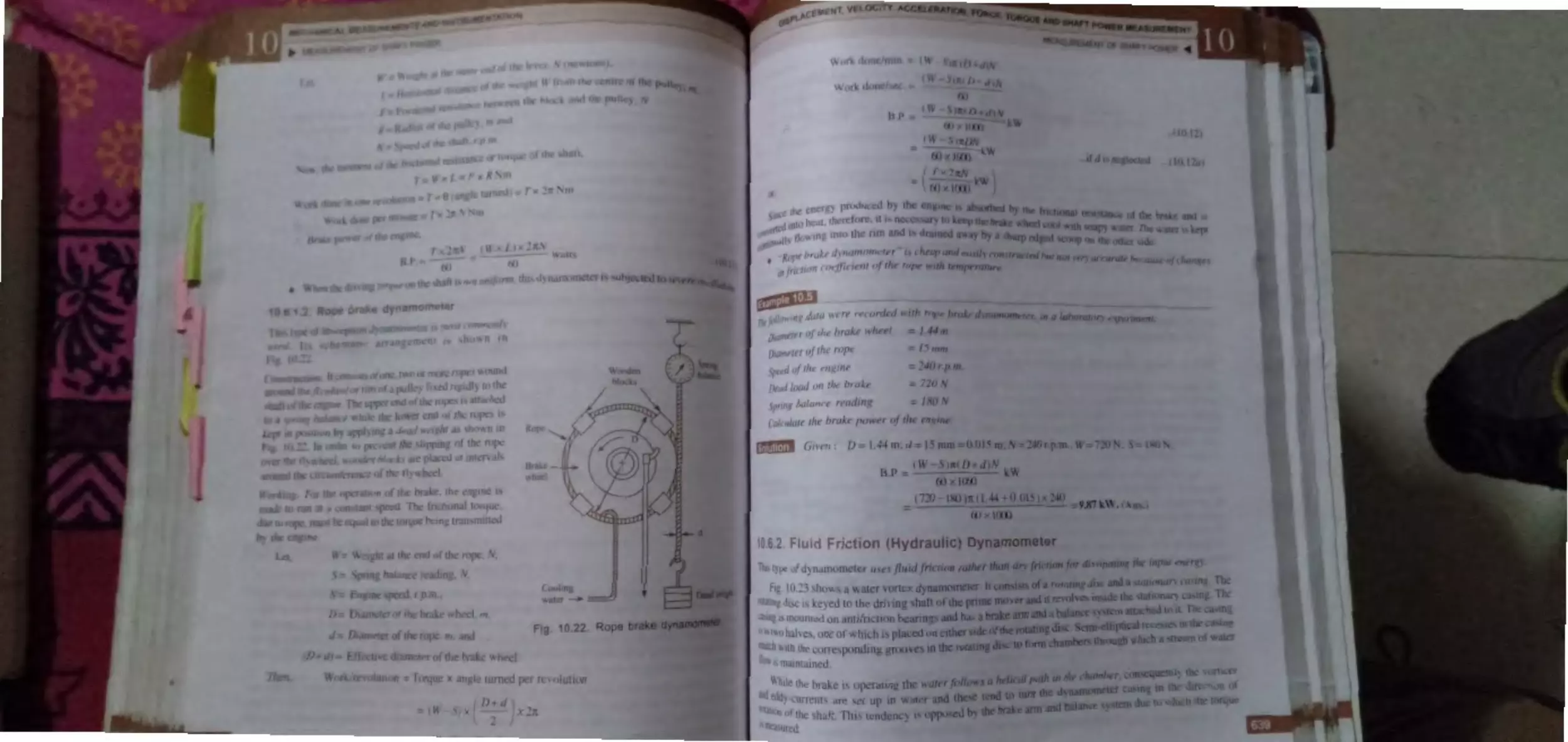

l ).6 .1 .-. Rope brake

dynamometer ... ... ...... .. .. 63 8

10.6.2. Fluid friction (hydraulic)

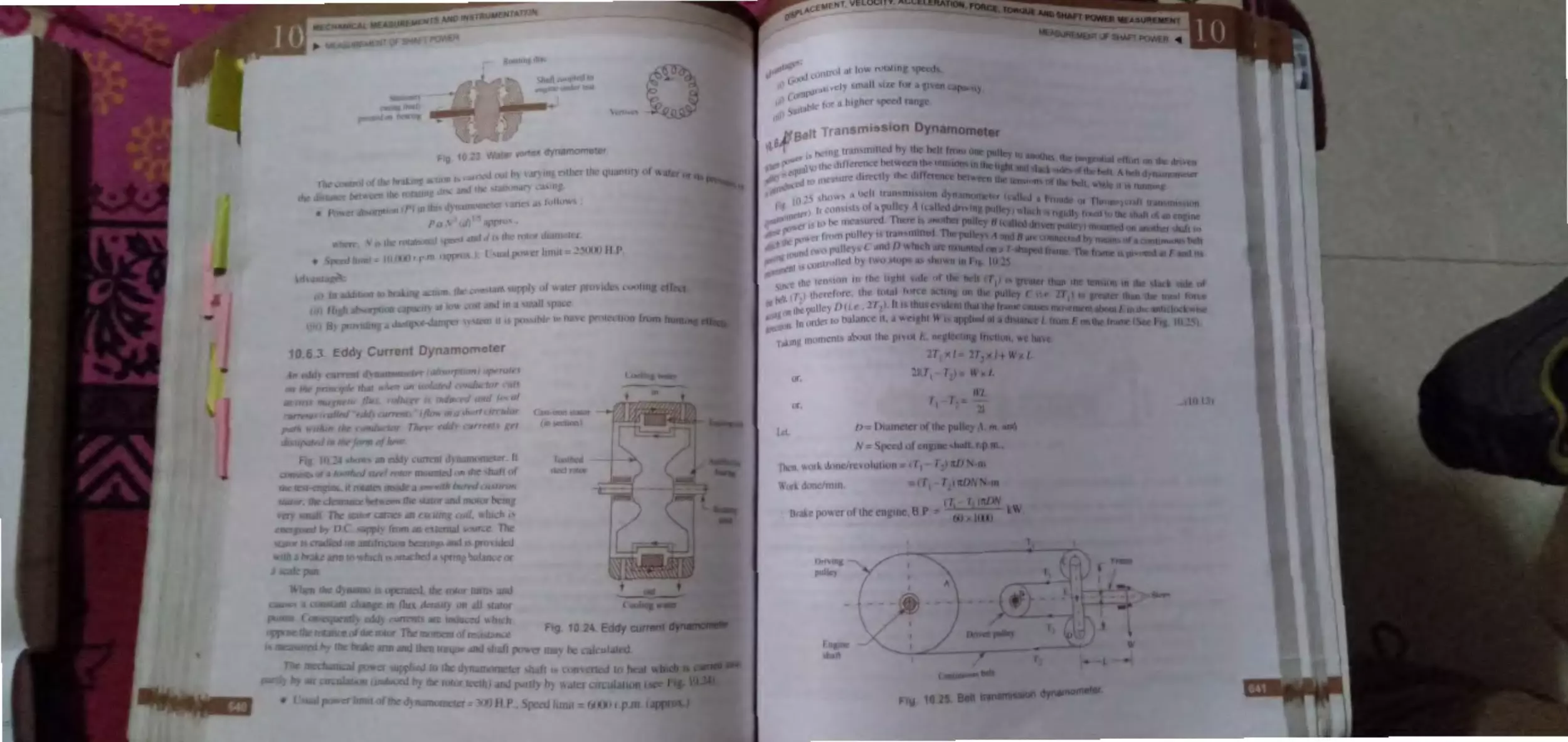

dynamometer ........................ .. .... 639

10.6 .

.

Edd cun-ent dynamom ter ... ... ... 640

I0.6.-L

B It transmission dynamomet r . 641

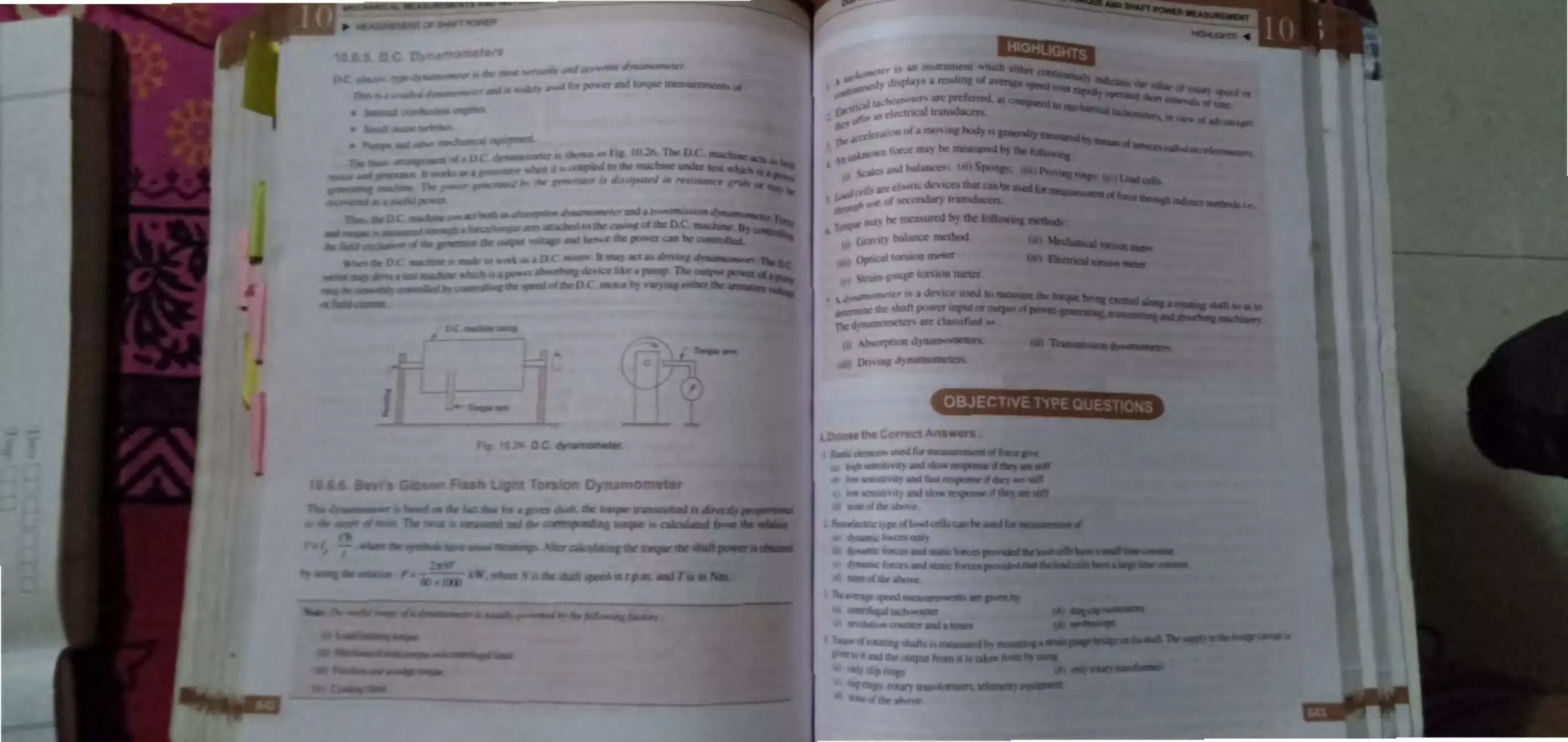

I0.6.5. D.C. d namom teL ....~ .......... . ..... 642

10.6.6. B L Gibson fla h light tor ion

d narnometer ................ .......... .. .. 642

Hi~hlighr ............. ...... .... ....... .... .... .... ...... 643

Obj ctiFe Type Que tions ....... ... . .. ..... ..... . 643

Theoretic zl Qu 'Stions ............. .. .............. 646

11. MISCELLANEOUS

MEASUREMENTS ........................ 647-708

I1. I. train Mea. urement an d Strain Gauge, .. 647

1i .1.1 . Introduction ......... ....................... 64 7

17

I l.1 .2 . Technique of train

1)

d .......... ... 19

t flinLar, "l ity..619

. f ·1n,=-ulnr lo ·i t. ' 6~0

measm·ement ............................... 648

11.1.3. R equi rements of a strain gauge ... 648

1 l.1 .4 . M chanica] train gauges .. ......... 649

l l.1.5 . Optical train gauge .................. 649

11.1 .6. Electrical train gauges ............... 649

•

•

CIHLlPmi

GENERAL CONCEP1S

•

•

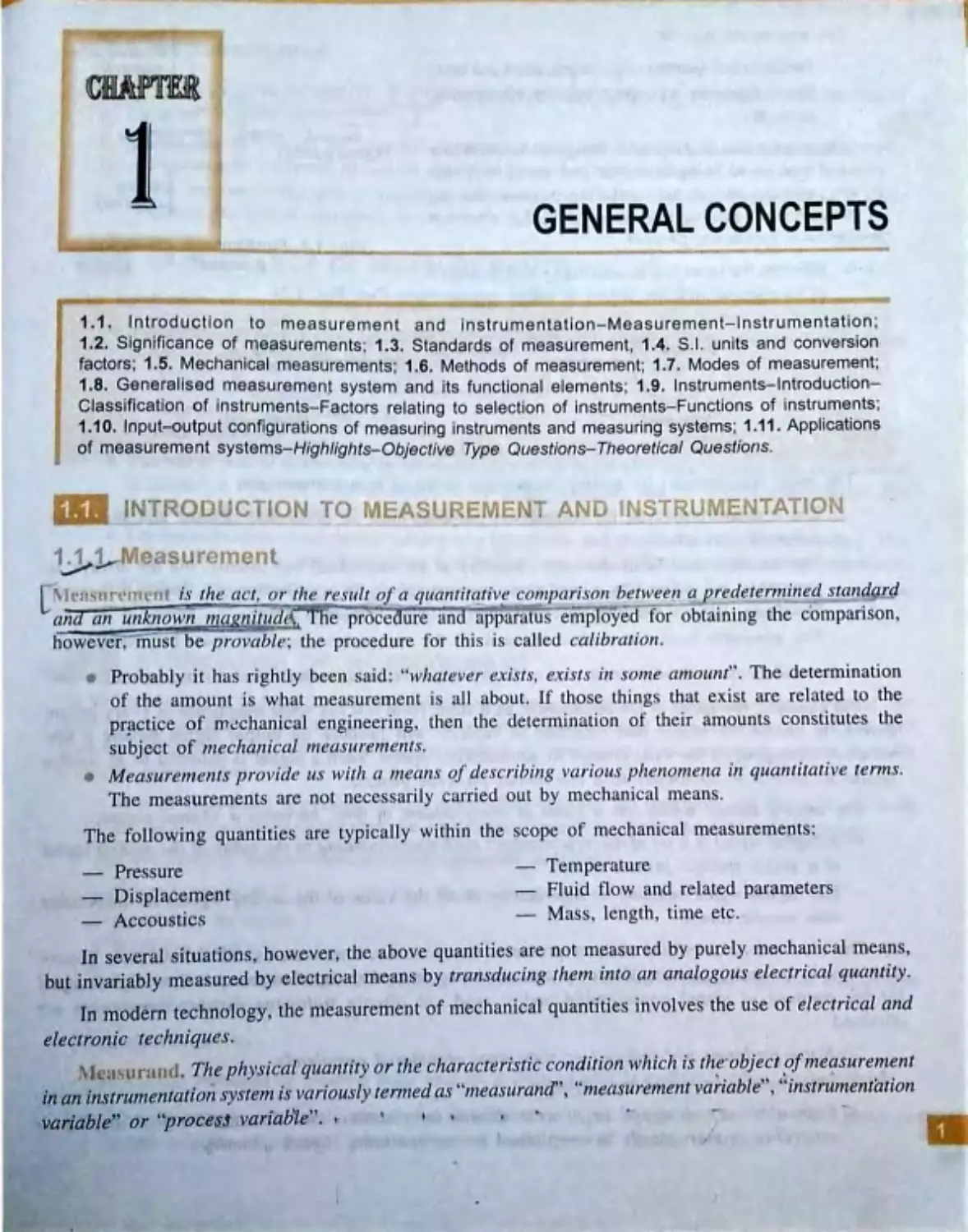

1.1. Introduction to measurement and instrumentation-Measurement- Instrumentation ;

1.2. Significance of measurements ; 1.3. Standards of measurement , 1.4. S .I . units and conversion

factors; 1.5. Mechanical measurements; 1.6. Methods of measurement; 1.7. Modes of measurement;

1.8 . Generalised maasurremen~ system and its functional elements; 1.9. lnstruments-lntroductioh-

Classiflcatlon of lhstruments- Factors relating to selection of instruments- Functions of instruments;

1.10 . Input-output configurations of measuring instruments and measuring systems; 1.11 . Applications

of measurement systems- Highlights- Objective Type Questions- Theoretical Questions.

•

1.1~~ easure1nent

't¢

L'\ ..••as,11·(~ ,e i ~ r ~z e,.gct ,_ . .~ ,- rli e result of a quantitqfiVf! co~pari s·on ~etwee ,1 a predetermirz eq staridarll

~n? atz I

unkno~,n ~ggg _piJ.uJl 1e proce ure an appar atu s employed for obtaining the comparison ,

howev er ; must be pro vable; th e procedur e for thi s is called cal·ibration.

Probably it has rightly been said: '' what eve r ex ist.~, exists in som e amoitnt'' . The determination

of tl1e amount is what measureme nt is all about. If tho se things that exist are rel ated to the

pr!lctice of mechanical e ngineering , th en the determination of their amounts con stitute s the

subject of m echanical ,nea s urem ents .

•

Measureme ,ie~· provide us wir/1 a rn ea,i s of deJ·cribing vcl ri ous pl1. enorn e11a iti quan.titative te rms .

The measurements are not necessarily carried ou,t by mech anical mean s .

The following quantities are typically within the scope of me chanic al measurements:

--

Prressure

Displacement

Accoustics

Temperature

Fluid flow and related parameters

Mass, length , ti1ne etc.

in several situations, however, the above qu•antities are not measured by purely mechanical means ,

out invariably measulied by electrical means by trant,·ducing then1 into an analogous electrical quantity~

•

In modetn technology, fue measurement of mechanica1 quantities involves the use of el ectrical and

electronic t~chniques.

.

McHsur~1,1,1 . The physical qua,itity or the character.istic condition whicl1 is th~·object ,of1neq.surement

in an instrumentati0n sy~,tem is variou~·ly termed as ''tneasi1.rand!' , ''measurernent variable'' , ''instru,nentation

vaniable'~ 01 ~'p:r:ocesJ va niable''. •

•

•

,

,

...

·

-

...

•

•

I

,

•

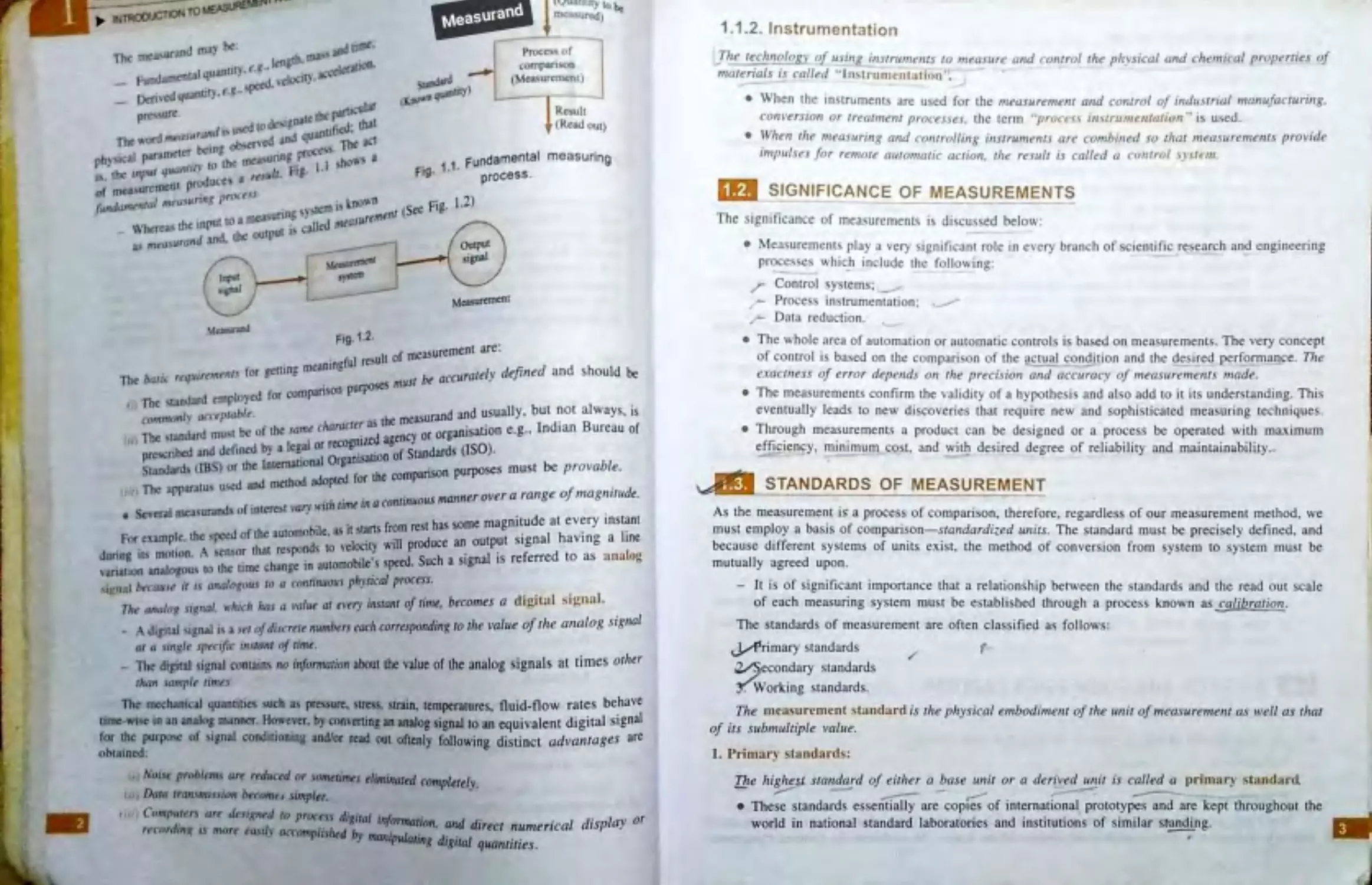

•

Procc , of

compa.ruon

( 1~ \UfCmt:Ot)

1 1 Fundamental

f ig. · · process.

measuring

~~, -,,.(il)COf

t>'iCCID

Fig. 1.2 -

1.2)

Mc:a9ffdl"ICOI

f easur~ment are:

.

meaningful rc~ult o m

The Jx11ic rt•,p11 re,nrntr for getting

-

" be accur01el)· dtftned a nd should be

•

0 purposes mu.11

The st.ind.ard emplo)cJ for companso

'

'"'";

11,,,1

,. cJ(',-~

1,r"blt.

the measurand and usually. but ~ot a lways, is

d.lrd mu1;1 be or' the same character as

or organisation e .g ., lnd1an Bureau of

, The: ,un

_

.

1 al or recogmud agency

pre\Cribtd 311d Jct1ned b} u cg_

isation of Standards (1S0) .

Sta~ (IBS) or the lntemauonal Orpn

•son purposes must be provable.

d··- ·'

_ ............~adoptedforthecompan

Th ann:untu, u~ iUIU mcuwu

if

.

d

(t,

c ,.,.

.

.

.

us manner over a range o 111agn1tu e.

r.

t • .... u•r'th lunt U1 Q cont1nuo

• Sc\'etal mta'iurJnds o tnttrCS 'a,., . .

.

.

.

fl est bas some magnitude at every in stant

For example. the peed of the automobile. as itls~ ~lml prroduce an output signal having a line

.

•

A

that responds to vc ooty w1

during 1tr. mouon.

!tCn..:i,or

.

b'l ,

..,. ..,. Such a signal is referred to as analog

\·aria11on analogou) to the time change ,n :iutomo I c_s st"'..v •

~..nJl b,cu"'" it ts analn,qnur r,, a fnnrinuous physical proctss.

,,.ht' anu/ao si,rnal, llh,rh hat a v,J/iw at n 'tT)' instant of limt, becon,es a digital ~ignal.

,,

"

.

.

.

al

_

A Jj~ial ,;ignal j1; a jtl af duerttt numbtrs each co"tspondzng to the va lue oftire arialog szgn ·

01 a rin,qle specific ,nttnnl of tilnt.

The digital signal contain, no infomration about the value of the analog signals at times other

than sampl, tim.r.,

The mechanical quantitie\ such ti pr~ -irc. stress, train. temperatures, fluid-flow rates behave

time•WIIC in an analog manner. However. by converting an analog signal to an cquivaJent digital signal

for the purpoltC of . iinaJ conduioning and/or read out oftenly following distinct ad,,antages are

obtained:

•

, J Nui" problr.ms an rtductd or JOmttimts elimUUll~ complerely.

< , Da111 tramnussian ~< "omtli simpler.

Computtn ar, dcsrgnt"d ro prore.u digital ln/"""'1Jio

.

recordini ,.s mnrt rasil) acromplishff by

.

n. ~ direct nun1er1 cal

manlpulalmg digital quantities.

displa)' or

1.1.2 . Ins trume ntation

. ,, .The tE!J.1lQ!2.K1. of LtJittR. u1 srr11n1e11rs ro ,neaJure a11d control the plt)'Sical and che111i< al r> ropenie~· of

n1arer1als i r ctilled " (n~lrt1me ntalic>n ".

• Whe n the instrument~ are u cd for the rneasuren1ent m,d co111rol of industrial ,n ,i11,ift1<:tt1 ri11g,

co111·ers1or, or 1rear1r1ent processes. the term " procei, 111 ~tr11n1r11tatiu11 ·• Jl) u,ed.

• \Vhe11 tl1e 11,easi,ring a,,d co111rol li11g ir1srn ,n1e11rs are co111bined so rl,at n1casure111e11r:r p ro 1·id<!

i111pulses f or re111<1le auron,aric acrio11, rl,e result is called a c.·,, , ,rr ol \)'\l('t11.

·1.2 . SIGNIFICANCE OF MEASUREMENTS

--

-

-

The sig nifi cance of measure ments il) discus)ed below :

• Mea surement s play a very signifi cant role in every branch of scientific r~ e nrch and e ngin ee ring

processes whic h i nclude th e fol lo\vi ng:

,r Control systems; _

,,-

Proce in strum ent ati on: _.. ,

-

Data redu cti on.

•

• Th e whole area of a ut omation or automatic control s is ba sed on mea sure ments. The very concept

of control is based on the compa riso n of the actual co ngi tion and the des ired performance . Tlie

e:racrn ess of error depends on tlie precision a11d accuracy of 1neasure111e111s ,nade.

• The meas urements co nftrrn the va lidi ty of a hypothesis and al so add to it its understanding. Thi s

eventually leads to new disco veri es that requ ire ne\V and sophisticated measuring techniques .

• Through measurem e nts a product can be designed or a process be operated \Vith ma,ximum

efficiency, minimum co t, and \vith desired degree of reliability and maintainability.

-

-

•

•

~ STANDARDS OF MEASUREMENT

As the measurement is a proces s of com pari son. therefore, regardless of our measurement metJ1od . we

mu st employ a basis of compari son-standardized u11i1s. The standard mu st be precisely defined , and

because different systems of units exist. the method of conve rsion fro m sys tem to ysten1 must be

mutually agreed upon.

-

It is of significant imp ortan ce thnt a relationship between the standards and th e read out scale

of each measuring system mu t be es tabli shed through a process known as _calib rq ripn_.

The stand ard s of me as urement are often classi fied as follo\v s:

J_ .A1rimary standards

/

f-

.

~ e c ondary tandard s

Y:Working stand ards .

Tl,e 111eas ureme nt s tandard is rl,e ph)•sical en1bodi111 enr of r/1e 11nir of111easure111e11t as well as that

of its subn,ultiple val,,e.

1. Primnrv standards:

•

Tlze /1ig/1esJ. sta11dard of eirl,er a base u11it or a derived ,,nit is called a primnn · . tand11rd

.......

-

.....,,,,,,,,,-

-

-

-----

.

~

-

~

__,.---

---

~

,,,

#'

• These standards essentially are copies of international prototypes and are kept throughout the

world in national standard Jaboratories and institutions of si milar st-anding.

,

'

• These ~tondurdilell unit. l\re:

-

Q11ite src,blt•

•

/11 \:{lriant

v·

-

No, relc,ti,·t• 1,u1 fi,,itt• . Ji

\Vhile setting up the prin1t\~ ·

standard~.

the follo,ving ptlint. are given due considerations:

I

4

(IlII

•

I.,4 •

,

Loni tin1e ~ tnbility of tl,e material.

Lo"' tcn,pcrnturc coe fficient .

'-"

No d<!teriorntion in it., chan1ctl'n tics

-

•

en\ 1ronmentnl c.~ondition~.

Rigidity of construction.

.._.,

_,,

./

_, ,,.

,, ith change$ in humidity. temperature and other

Ac:curac)r of n,u chining .

✓

Most sophisticated tcchniqu~ t\.1 ht: u~ed for ,n~a!.uring phy sical dimension~ ,vh1 ch determine

the :1ccur.1cy of the :- tandarJ.

• The prin1ury ~tandnrlb ,,,,,,,,,i1u1c!' tit« • 11/1,,nar,· ba~, .\ vj rtfr:rc•nrc.· and are u~cd for the PU'"Jl<'- . .c

of ..vt•r11i<'r1li1>n ,1,1 ,i l·c1lif1r,1tiot1 t>/ .,t ·c ·undtJn Jtt1rrtlt1rd,· " ,

-

Thes~ stundard:-.

have chc ··J,i.~ ht•.,1 pt>J,, 1l1/f! a, l'"''-'"".. but nn· ' '<'')'

1

•\JJr11., ,,.<' tel o,, n .i.nd

muintuin .

-

The prin1ary ~tantlurd s uru ,,,,, ,,,.,,,/,,/•le' j,,r u,c · c111tJi<lt· tht• 11atio ,u1l lt1br,rt1l1J1 tt ~

! .. ' t • 410,t11r, .. _, a,,riar{l,:

rTllt ~c..:tlnclury st-undunt:-

/>ri ,,,,,rv ,\tn11,l11r,l. , ~

.

-

ur~ the ,·, · (<'r< nc ~, . t t1libra1, · ,i 111,ul,1 ,J, cif' ., i g11r,I ,111d ,·, 1li /,rc11,•d .fr,,,n 11,t:

..,

•

Thl"SC nae sent f>t! t ii>di~ ~1lly lt> th~ n .1t1on ,t ,tandurJ latmr:1t,.,ric ~ for their ..:nlibrut1,1n l thc 1ntcnll1

l"lf ~n lit,ratiun dept?.nd, upon 1h~ nt:curac~ ;ind th~ tyre of ~tanclan:t lR·ing n1111nt :,incd).

•

T lt~$e ~tnndurtl are kC(ll hy the 111c. 1~Ul'CJ1k.'nt lubor:lt,1rirs. Jnd the indu,tn ul Of!!;1n1,ution~ t ,>

· heck and cnlibrt\ll' the ~l:ltt• n,1 l\>f'll!- tl"1r their a ('\tra"') ' and preci:..ion .

. \. \\ c,r1'.i 11 1t , t.t11clnrd,:

• 11\cst> st:1ndnrcl, ha\ c an :i~curucy ot ,,,,,, ,,rJc-r /11\\ ·rr ,~1 11 rh,11 ,,f tlict .\«1 t>ttcl,,r,· s tw,dard(.

• '1'ltl''~ nre the norn,ul :.landunl, ,vhach an· 11,«·d /,, tilt· " 'r>r!,•r., ,,,.J tc•cl1ri,,·,,,,1., ,, ·It<> ,1,·tiwll,

, 'tifl'\' ()Ill ti,,• ltlt'(l.\lll '<•ttlP-flI, .

•

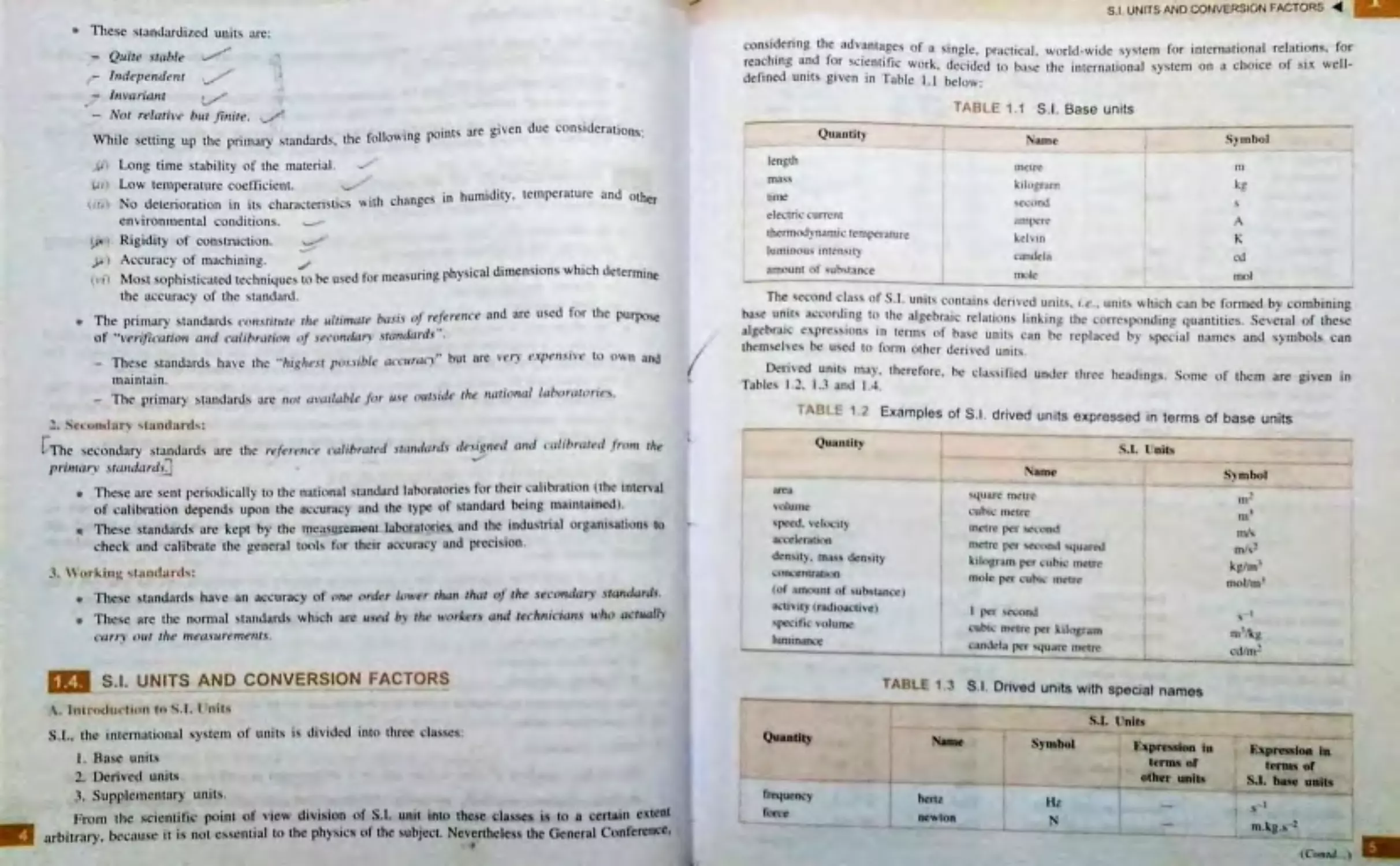

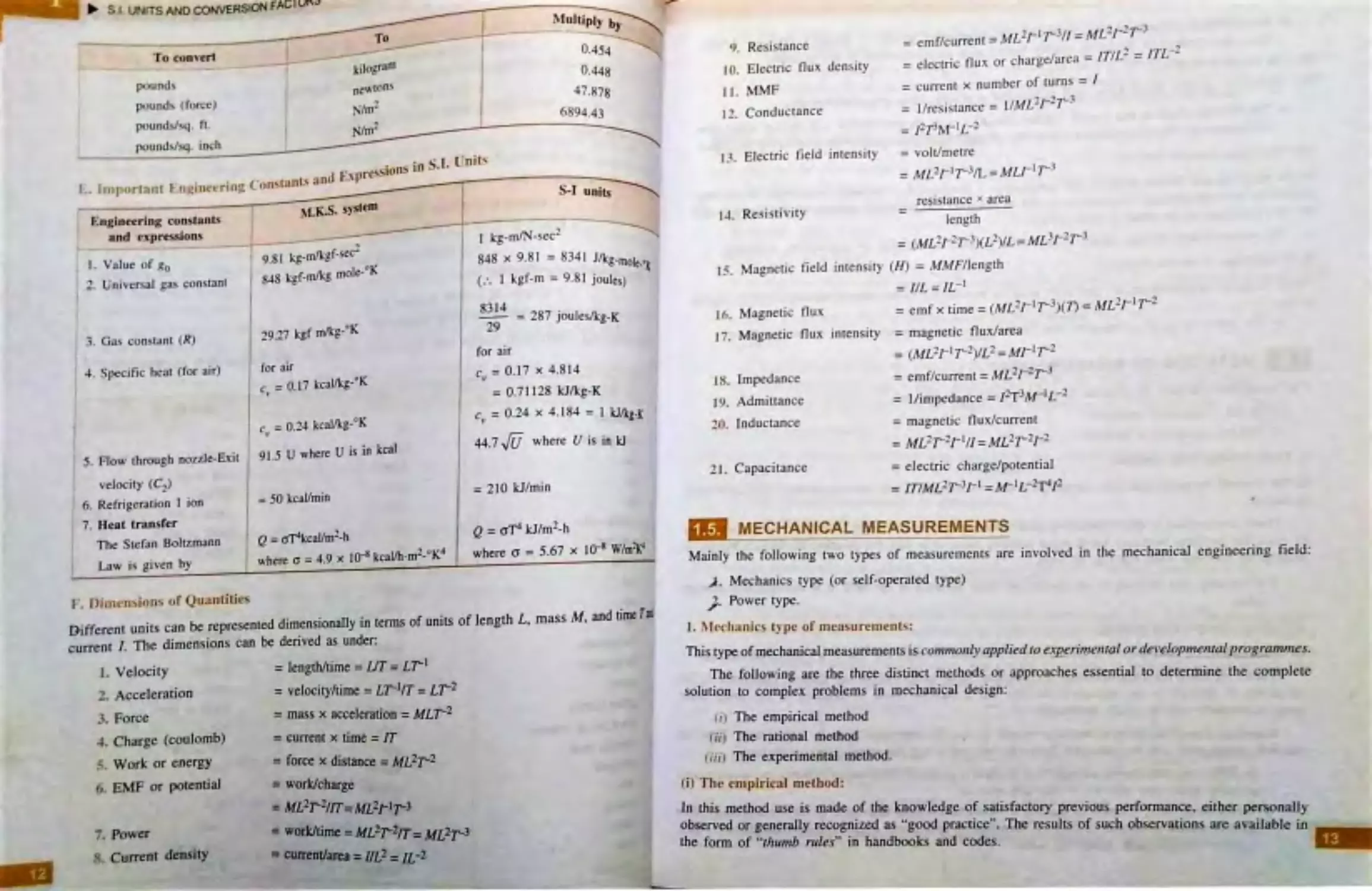

1.4 . S.I. UNITS AND CONVERSION FACTORS

I. Hu~~ unit,.

:?. l>oriv~tl u11i t.-.

.,. S upplc1nont ury

t- ..r«)m tl•lC ~c ie n1ifit" ptlint l>f ,•,cw &J1vi1'ion of S. I. unit intll t~' I .C cla~t - is ltl 8 crrtain txtclll

arhitrury. bt'cn,1?-i ~ i1 is nut e~icn1.ial tu the phy~ics t,f the subJcct. Ncvcnhc-lc . s the General Conten:nc:c.

,

..

•

•

S.I UNITS AND COt.SVERSION FACTORS ◄

con 1dering lhc advantage~ of

nct

.

1

,n., "n·• r,.

,••

'fj· 0

~•ng lc. pr;1c1ical. v .~

a rld-,v idc ,y. -, 1c!n1 fo r inl~rnotiunal relt1ti()n11. ror

re

::-- " u 1,lr sc 1cnt1 Jc \York d, .d

.1

d

efined unit, oiv. . T

·

cci cu lo ba,c thl.' .' intcrnalion:11 ,ystern on ;.1 choice ,,r ~•x wcll-

e en •n u.blc 1. 1 below:

f

I

Qllilntit)

nme

clt"Cln"· C\111\.'l\l

1hcm,,'ldyn,tm1c t<"n1pc1a1 urc

lunnnou, 1n1en!o.tl\.

. uno unc ot ...ub,1.111cc

TABLE 1.1 S .I . Base units

'l\fl)l.'

n1e1rc

kilopr-.i n1

,ecund

,1n1pcn.•

kct, ,n

cintlel.1

mole

S)1obol

m

kg

..

1-\

K

<:d

1.2 Exnmplos of S.I . drlved units expressed rn terms of base units

--

Quanllty

an-.,

, ,,tμu,c

,pc~d. ,~!.'I.ti)

1k,"CIt.·r .n~ 1,n

dcn,1l). 111.,,, di·n,,ty

,1ni.:cn1rJhun

(ol uuount of , u~ l.snc.::e 1

,4u.1rc ,u,,u c

~ uh11. n\clt~

1nr1r,· J)\·r ~ i.11nd

IIICll'C J 'I ~ ,.,n,1'-ttuJn.-,1

~ l ln~turn pt·r 11h11.• lllc-tn·

1na,IL· per ~ut, 1. _

Ill~ 11 .

-

-

. ,I.lTni1,

-

-

S"mhol

•

..

nt·

I\\\

rn/,

m,._'

kfltn '

fn(lfl rn I

• "ll\ ll) lf.WHl .&cll'!C)

I p..·r '{" nnJ

'~"'• lie \'olurnc

,

~ub11. n1ctrc ~• ~,h, r,1111

,

tun11n.mcc

n, '\.~

-

------------l

l~- -~ . uhl,•la pc, "tUo1tc nt<ln·

=:

-

""'' "':

__ _ _....,! ...__ __ -

-

-

TABLE 1... S I. Or,ved unit& with special names

•

nm

•

s•

s•a

--- --- --

,--------~-----,----------

S.I. l1nlh

N&JK

hcru

IW\\IOft

Symbol

•~PR•IMO ta

t era11 er

otlter units

,__ __...,. ,.,~,-~ ~

-

-

-

~la

tc,aa. .t

S-1 .

llldb

..

SIU

NIT S ANO CONVERSION FACTORS

GENERAL CONCEPTS

-

-

....

-

QuaaUt-y

-- --

-

-

Esprcs.,1011 In

,_

-

-

-

£xpress100

NUM

s ,•anbol

tem lS of

te11ns 1,

other unJts

s

or

I

.I.b~

-

.-

UllJta

.

I

tJrt's ure

Pa

Nl m2

n,-1

.kg.s-2

I

'

pu.~ 41

I

S .I. UNITS ANO CONVERSION FACTORS ◄

-

.

I .l . nit.,;

Quantll,,

-

-

,._

-

-

--

•

a nrue

Symhol

Expr~ . !>ion in

lerni.s ol

en~!'@,) , w ork.

-

-

S.J. hnse unit.Ii

qua11tity of

hon-c: J)O\\ er

joule

J

N .ID

n1

2.kg .5

-2

radia.n, n~.

'

qWlntil\· of

•

el~ lricil\'

J/s,

n1

2/kg.s -a

I

\\-an

,v

..

I electric charge

colournb

C

A.s

.A

elt!ctric ren.-. ion.

eleetric potential

I'

W/A

n1

2.kg. s --l ,A-l

volt

V

cupaciranee

farad

F

CN

m-2

.kg-t _s4

~ lectric resL~umce

I'

ohnl

n

VIA

m-2kg -3

·-

.s

.A-2

conducmncc

•

s

AN

m-2

.kg-ls3 I

s 1emens

.

-A~

magnetic fluA

weber

Wb

v.s .

m2.kg.s-2.A- I

magnetic flux density

tesla

T

\Vb/m2

kg.s..,2.A-1

inductance

henry

H

Wb/A

m2k g .s-2.A-2

lu minous fl ux

lumen

bn

-

cd.sr

illuminunce

lu:x

Ix

-

m-2

.cd.sr .

-

penni1tlvi ly

farad per 1nc1rc

•

-

I

current den,i1y

F/m

ni-l.kg-1

.~,'.A2

om~rc per i.qu.1rc metre

mn8Jlellc field , trcngth

Alm2

-

ampere per me1er

penneabiIi ty

Nm

-

henry per metre

molar e nergy

Him

k.,

.,

I joule per mole

m. !?,-::>--.A- ·

molarheat cap:u:ity

J/mol

m-2

.kg., -2

.moi-1

Joule per mole kelvin

J/(mol .K}

m-2

.kg.s-2

.K-1

.moJ-1

The S.I. u

•

•

•

.

~ 1LS assigned lo Lh1rd clnss called "S

.

,,.

-

units or as denved unit~. Refer Table I.S and l .

6

~pplementnry untLS may be regarded either as base

•

Quantity

S~I. Units

-

~

-

-

-

Name

I

Symb ol

pl ane angle

radian

f

rad

solid angle

steradian

j

I

sr

TABLE 1·5 S .I . Supplem entary units

TABLE 1.4 Examples of S .I . derived units expresse.d by means of special names

TABLE 1 .6

emen ry units

Examples of S.I. derived units formed by using s uppl

ta

•

-

'

S.l. Vnits

•

-

Quantity

Name

Symbol

Expression in

,,

tenns of

I'

S.I. base ,,nits

Quantity

S.L U nits

l

I

Nam,~

I

Symbol

ang ular velocity

raruan pe r seco nd

ang ul ar acceleration

rad/s

radian per second squared

I

rad/s2

dynamic viscosi 1y

pascal second

Pa.s

m-1

.kg.s-1

'

moment of force

metre oe.wton

N.m

m-2

. kg.s- 1

s urface tension

newton per metre

Nim

I;

kg.s- 2

heat fl ux density, irradiance

watt per: sq uare me tre

W/m2

kg.s -2

heat capaoity; entropy

jo ule per kelvin

J/K

m-2

.kg.s -1

. K-1

specific heat capacity.

specific entropy

joule per lcilogram kelvi n

J/(kg.K)

m-2 .s -2.g -1

speeifie energy

jo ule per kilogram

J/kg

m -2.s -2

I

thermal co nductivity

watt per metre kevin

W/(m. K)

m-1

.kg.s-3

.K-1

-

energy density

joule per cubic metre

J/m3

m-1

.kg,s-2

'

e lectric fi eld strength

volt per metre

Vim

m.kg .s2 .A- 1

I'

e lectric charge density

coloumb per cu'brc metre

CJm2

'-

m-3 .s .A

efeclric fl ux d ensity

colo umb per square metre

CJm3

m-2

.s .A

(Contd.. , )

ra.ruant intensity

watt per steraru an

W/sr

radiance

watt per saure metre steradian

W-m-2 .srl

l

-

Factor

Prefix

Symbol

i

-

Fact or

'

Prefix

I

I

Symbol

1ot2

I

tera

T

10-1

I

109

~

deci

a

I

giga

G

10-2

centi

106

.-

C

mega

M

J0-3

milli

I

103

m

,

kilo

k

l~

I

•

102

nucro

μ

hec10

h

10-9

nano

101

~

da

fl

10-12

•

pico

p

r

10- •s

'

fasnto

l

f

10- 18

all()

a

•

TABLE 1.7 S.I. prefixes

•

•

•

I

•

I

l of thennodynamic tempcr.ilt1re of th e triple~

273 16

•

..._ .

1.

nt• n .. it v in the perpendicular direction , of a SUrfact N

th~ c-an cl.a ,, ,,~ um1nou 1 ,

.,•

"'

I

f bl L 1-. . Av at 3 temlV'rature of freezing platinum under a p~

:a --- Jii.CUarc rnctrc IJ iJ w: ... 1,vu.,

r-

Hll).lJIXJ

I( I. 1~ nc ,,,n per ..quarc metre.

'fhc m,,I.: i, the a1n,1unt of ,ub,uinee of a y~1cm " 'hich conuii_ns as man y elemc~

·

oo12 i-,.,

•·arbon 11 When the mo le 1s used . the elemcn12r1.

en11t, ~

u-, thcrt ure att.1m, ,n

.

"'~· ...

-·

.

.

·-1

·

..___

t- --•

. . - · • m ay be- atom molecules. ions. electron s. other particles er

cn11t1e~ nUJ ~C ,111,;

pee, 1cu IUIU

•

~ tfted JtnUP1' tJf Ul!h particl~.

The nidaan i ~ the plane angle between two radii of a circle that c ut off on the cirdc

,n at\: equal in lt"n1th to the radiu .

.

~ -· The _ter.uhan is the M>lid angle which having its \fertcx ~ the _centre of a spbm.

CUI ,, ( an aRa tlf the ~urfk~ of the !iphcre cqu:il to that of a square with S1des of length equal

ta> the nadiu of the phcrc.

I ( 'ttj~~ _:

~~t•

. ~ newtnn cN) ,, a dcri~cd unit of force and is defined as the unit of force per second~

when titting on• m•~' of l kilogram gi- .:e s it an acc(:clerntion of one metre per second per second. SUl(r

,;eek, atiaft due to an~IY equal 9,81 mJs1: one kilogrmn force equals 9.81 newtons.

.. ,,. _.,

. T he ioule ,J, , a derived umt of energy, work or q~antity of heat and is defined :

it-. .,ort, done ~ a totce of one ne~ act 10 ~ to cause a dis~lac_ement of one metre. ~

defined mr c■pac;t)' to do wotk. A urut of cneray an nuclear physics as the electron vol~ (eV) rl

i c:lefiaed a lhe ca«SY aained by an electron in rising through a pptential d1f(erencc

••• mil.

I eV • 1.6021 x 10"19

~-

•

1 -n. wad <W) ii a •• of power (i.e .. 11te of doing work)

•

Power m.., . •

(or &Yl in_joules

time in secon&

Thu, I "ntl equ..11, I J<lule/- .ec .

I kilo\vott-hour (k\\ h> = 1000 \\.ill -hour-

= 3600000 JOU le- .

'1•

1

h ll,I , The coulon1b (C) ,, the deri ved unit ot ch=.1rf!c. Jl 1-. ucfin~d a., the qt1c11111r. _

"' el,•c·r, tciti

pnr,i11fl o ;:ive.n puint in a r1 rc1111 ...,,/, en a c1,rrn11 of I A 1, 111urnru1nc ·d fi,r I ,.·c 11nd.

where.

Q =cho rge in <.:<>ul otnb , .

/ ::: current 1n ampere,. and

t = time in ,ccon<h.

Q=I ·I

I coulomb repreM:nt, 6 .24 x 10 1h electron .

<Jhn, The oh1n (fl) i~ the unit of electric re istnncc und ,. _

de lined a c; tht· r t#\ista11 c.c i r1 \t l1 ic-}1a c.·cJ11,4;fa111

c urrer11 of I A ge11c r<1tes /, ear ,11 rite rate rif I \V{llt.

' -;il 111t: 11. The siemen is a unit o f electric conductance (i.e . . reciprocnl of r~i ~usnc:e ). Jf a ci"rcuit ha., a

resistance of 5 ohm . its conductance ic.. 0.2 'l iemens. A n1ort! commonly w.ed name for ~ic1nen is

ITUIO (U).

\ olt. The vo lt i a unit of potential di fference and electromotive fo rce . JI i~ dt:fincd a~ the <liffere11ct·

of pote111ia/ across a resistance of I ohm COrr)·i11g <1 curre111 of J a111pere.

llcrtz. The hertz (Hz) i a unit of frequency l Hz = I cycle per econd.

Itl,1-. . . .: -,,,,,\t r . lt is a practical unit of mechanical output. BHP (Briti tl horse po\\1er or brake horse

power) equals 746 \Vatts. The metric horse po\,·e r equals 735.5 \varts. To avoid con fus ion between BHP

and metric horse power, the mecbanicru output of machine · in S.I . units. i expres ed in \,,atL~ o r

kilowatts.

The salient features of S ~l . units are as follows:

l. Tt is a coherent syste m of units. Le.• product or quotient of a ny t,vo ba. e quantities re ults in

a unit resul1:1nt quantity. Fo r e.°'ample. unit length divided by unit time gi es unit velocity.

2. lt is a rationalised . ystem o f units, applicable to both. magnetism and electricity.

. ,. It is a non-gravatio nnl system o f units. ft clearly distinguishes between the units of mass and

,veight (force) ,vhicb nre kilogram and newton respectively.

4. All the units of the system can be derived from the base and supplementary units .

5. The decimal relationship between units of same quantity n1akes possible to express any small

or large quantity as a power of 10.

6. For any quantity there is one and only one S.l. unit. For example. Joule is the unit of energy

of aJJ forms such as mechanical, heat, chemical, electricaf and nuclear. Howeveri. kWh will also

continue to be used as unit of electrical ~nergy.

,\d,•ant.lt!.es or S.I . { 11its:

1. Units for many different quantities are related tfirough a series of simple and basic relationsbip.

2. Being an absolute system, it avoids the use of factor •g~ i~e . . acceleration due to gravity in

several expressions in physics and engineering. which had been a nuisance in all numericals in

physic-s and engineering.

~ Be•ng

•

..,·

d t "_ . of rationali sed JvfKSA sy~tem .

•

0 r.iuon.u,,cd sy~rem . it cn t- urcs u.LJ the o vo? 0e~·" '

1

n the

field, o f electriciL}' · mag netis1n. clecrricnl engineenng nod

electrons . .

4. Joul~ is the onJ) sole unit of energy of all forms n_nd " 'alt is lhe ole unit of power hence a I

of labour is saved in calculadu~.

Ot

5. J_t i~ a . coherent .!>Y'<tcm of units and mvolves only decimnJ co-efficients. Hence it is very

convenient and gu.ick ~v~tem for cuJcuJations .

<,. Jn elcctJicity. a1J the pra~tj<.:al uniL, like volL otrm. ampere. henry. farad, coulomb. j o ule and w

accepted in iodu. try antl labor3tories all over the " forld for ,vei l over a century have beco art

ub~olute in the,r own ri ght in lhe SJ. system without the need for any more prac ci caJ uni:e

IJi~ad,·antal-!e- . :

l . The non-S .J. Lime! units 'minute· and •hour· will still continue to be used until the clocks

w:.rches are u!J chungcd to kilo ~econds and mega seconds ere.

and

2. The .b~se unit kilogram ( kg) includes O prefix, which creates an ambiguity in the use

multiplrerb with grJJTJ .

of

3. ~( ~~i~ for energy. po\ver and pressure (i.e. . jouJe. watt and pascal) are too s_mall to be expressed

• 0 s cience a,nd rechnology and. therefore. in s uch cases the use of larger uni ts, s uch as MJ kW

k'Pa will have ro be made.

'

•

it. There ~lrt! di~ficulties with regard to developing ne\v S.r . units fo r apparent and reactive ener .

while Joule 1 • the uccepted unit for active energy in SJ. systems.

gy

0. ( :()fJ \ ~n,i<>O f·'Ul'tf)r'S

J. f -nrce:

I ne"•con = kg.m/sec2 = 0.012 kgf

I kgf=9.81N

J bar = 750.05 mm Hg =0.9869 atm = tOS N/m2

= J03 kg/m-sec2

I Nim = I pascal = I0-5 bar = J0-2 kg/m-sec2

Jntrn =760mmHg=l.03kgf/cm2=J.01325bar

= 1.01325 x JCP N/m2

""1. '''(>rk. Energ__\i or H eat:

•

J Joule :: I newton metre = I watt-sec

= 2.7778 x J0-7 kW-h = 0.239 caJ

= 0.239 x 10-3 kcal

I cal =4.I84 jouJe

= 1.)622 x Jo-6 kWh

I kcal =4.J84x J03joule =427kgfm

= 1.1622 x 10-3 kWh

J kWh = 8.6042 x 1(>3 cal = 860.42 kcal

= 3.6 x 106joules

I

J kgf-m =

427 kcal = 9.81jouJes

•

•

I

•

I

I

..

l watt =I joule/sec =0.86 kcal/h

I h.p. = 75 m kgf/sec. = 0.1757 kcal/sec.

= 735.5 \Vall

l k\V = 1000 W:lllS = 860 kcaJ/h

5. Specific t,cat:

l kcal/kg-°K = 4184 joulc./kg -K

6. Thermal conducti,

0

ity :

1 \\1atl/m-K = 0 .8598 kcal/h-m -°C

I kcal/h-m -°C = l .16123 watt/n1-K

= J.16 123 joules/s-m -K .

7. Heal transfer co-efficient:

l ,vatt/m2-K = 0 .86 kcaJ/m2-b -°C

1 kcal/ m2-h -°C =1.163 \Vatr/m2-K

.

The foll o\l,1in g conversion factors may be us ed to con vert the quanlities in no n S .I . units into S .I .

units.

To convert

"

a ngstroms

atmospheres

bars

Btu

Btu

circular mil s

cubic feet

dy nes

ergs

ergs

feet

foot-pounds

foot-po un ds

gauss

grams (force)

horse power (metric)

lines/sq. inc h

Maxwell

mho

,.

•

micron

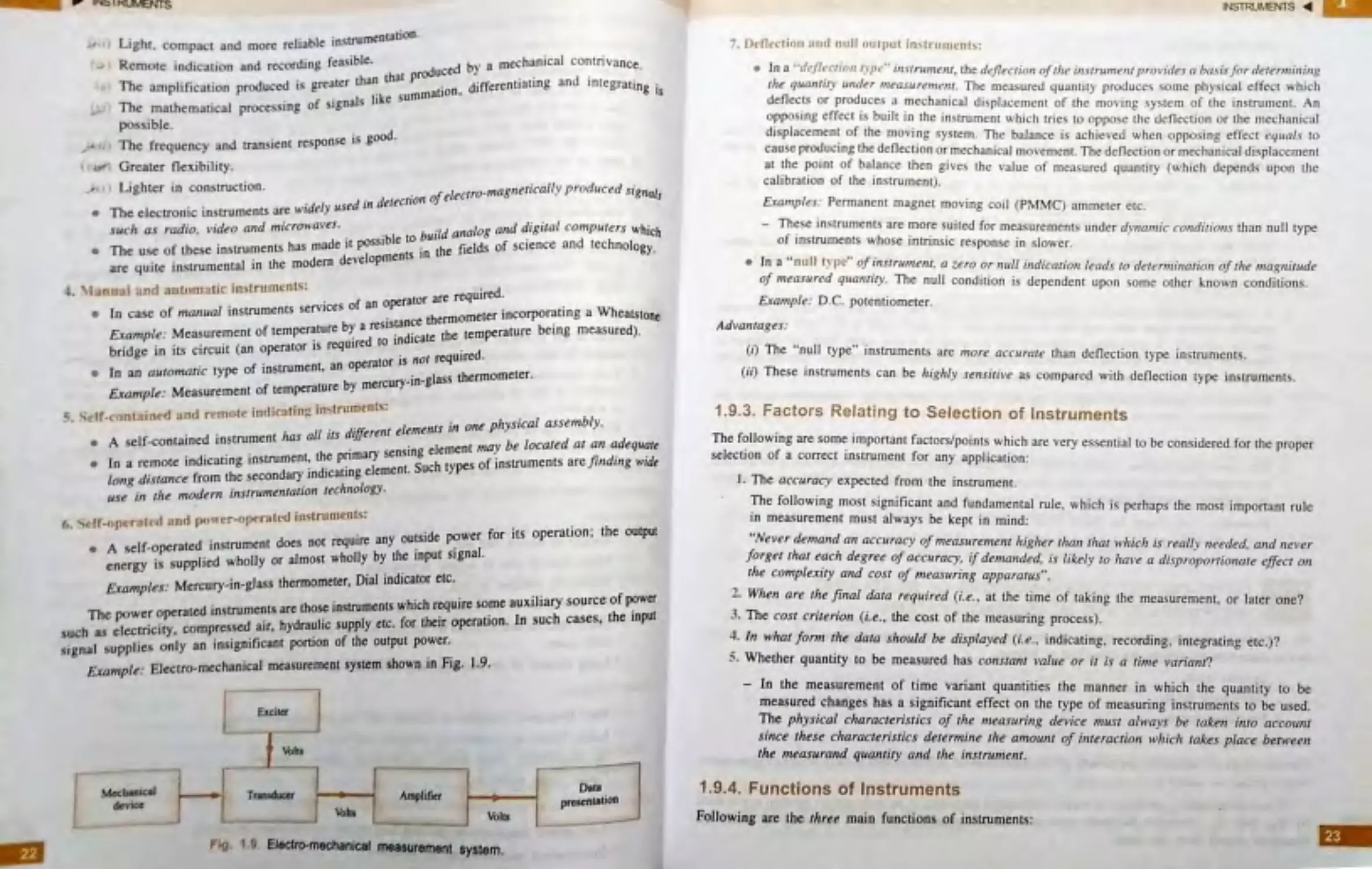

miles

mils

pouoclals

-

..

To

m

k g/m2

kg/m2

joules

kWh

newtons

joules

kWh

m

joule-s

kg-m

resta

newton

watts

tesla

webers

•

s1emens

metre

km.

an

newton

I•

-

-

M ultip ly by

10-10

1033 2

1.02 X 104

1054.8

2 .928 X lo-4

•

5.067 X 10-10

0 .02831

10-5

10- 1

0.2778 X 10-13

0.3048

1.356

0. 1383

Jo-'

9.807 X 10-3

735.5

).55 X 10-5

10-s

l

10-6

L.609

2.54 X J0-3

0.1383

.

[ To convert

-

To

.~ ---

___

,_

.. ___

J.il og,r -Jlll

~

~t ipty by

0 .454

0.448

47.878

6894.43

•

pound-;

()<)Und-. ( ron:e)

p<>und-./ ,(J. ft .

pounds/,q . inch

newton"

.,

1 fm-

·on .i·nS.I .Units

l• ress •

·

·

·

c· nst·~11~ nnd ~~p

~· Jr,lfJOr lanl f.11~llll'l•rtn~ ( _t

·

...

S-1 units

I

~ 1 .K.S- system

Engineering cons tants, _ _!----~---;------)~;:~:~--- --

and expr~ons

_

I

I kg-m/N-sec

2

IV

_,

f--

·-

I 9.81 kg-m/kgf-sw

848 x 9.81 = 8341 J/kg-moJ•.•i,

.

.uue

ox0

K

~·I\

0 _j8 kgf-m/kg mole-<>

kf

981

2. universaJ gal- constant

o-.

(:. J

·g

-m=

•

joules)

3. Gu.s constant (R)

4. Specific heat (for air)

5. Flow through nozzle--E .xit

velocity (C2)

6. Refrigeration I ion

7. Heat transfer

The Stefan Bo lLZIDann

Law is given by

for air

c = 0.17 kcaJ/kg-° K

I

c = 0.24 kcaJ/kg-<>K

,.

91.5 u where U is in kcal

= 50 kcal/min

Q = crT'kcaJ/m2-b

where a= 4.9 x 1~ kcal/h-m

1- °K

4

8314

.

29

= 287 Joules/kg-K

for air

C =0.17X4.814

I'

= 0 .71 128 kJ/kg-K

c,.=0.24 x 4.184 =1 kJ/kg-K

44.7 Ju \Yhere U is in kJ

= 2 10 kJ/min

Q =oT4 kJ/m2-h

where CJ = 5.67 x to-8 W/m2K.•

i,· . Oi 1 11 ~n:>i,,ns of Quantities

Different units can be represented dimensionally in terms of units of length L. mass M, and time T•

current /. The dimensions can be derived as under:

J . Velocity

= length/time =UT= L,

1

2. Aceeleration

3. Force

- 4_ Charge (coulomb)

5. Work or energy

6 . EMF er potential

7. Power

s. Current density

= velocity/time = LT-1/T = L,2

= mass x acceleration= MLT-2

= current x time = rr

= force x distance = ML2,2

= work/charge

=ML2r'l1rc =m2i-1r-3

= work/time= ML2r-2rr, = ML2T-3

= current/area= I/L2 = IL -2

9. Resistance

ro. Eleccric flu x density

=emf/c urrent= ML2, 1r--3I / =- M l? .J-

213

=elecuic Oux or charge/area = IT/l 1. = /TL-? .

=current x number of turns = I

= I/resistance = 1IML

1

f-

2

t3

TJ. MMF

12. Conductance

= !2T3rvr-• L-2

1.,. Electric field inten s ity = volt/metre

=ML2,1

,

3/L =MLJ- 11 3

•

resistance x area

L-t . Resis tivity

length

-

-

= (ML2, 21 3)(L2)/L=Ml31 21 3

Js. Magnetic fie ld in tensity (H) = N/MF/leagtb

= /IL=IL-1

16. Magnetic flu x

= emfx time=(ML2r

1

,

3

)(1) = ML

2

r

1

r-

2

J 7. Magneti c flux intens ity = magnetic flu x/area

= (ML1J- 11 2)/L2 = Mr1r-2

18. Impedance

= emf/current = ML

2

r2

,

3

19. Admittance

= I/ impedance= J2T3M -

1

L-

2

20. Inductance

= mag netic flux / current

=ML2,2

,

1//= ML21 2J-2

21. Capaci tance

= e lectric charge/potential

= fTIML2, 3J-1

=M- 1L- 2T4!2

-

MECHANICAL MEASUREMENTS

Mainly the following two cypes of meas urements are involved in the mechanical engineering field :

.J . Mechanics type (or self-operated rype)

}· Po\ver ty pe.

1. .\ .Jechanics t)' pe of m ea~ urements :

This type ofmechanical measurements is com111011l)1 appliedto experirnen1al orde'}elopmenral program111es.

The following are the three distinct methods or approache..s essential to deteanine the complete

solution to complex problems in mechanical design:

<1) The empirical method

cii) The rational method

•

t ;,, > The experimental method .

(i) T he empirical m ethod :

In this method use is made of the knowledge of s atisfactory previous performance, eitbe.i: personally

observed or generaJJy recognized as ..good practice... The results of s uch observations are available in

the form of •·thu,nb rules" in handbooks and codes.

13

'

11111: HQ)SQF

• Thimlhodh

.

~ :ill'-' in case of complex ystem •

.

e

.

o" c, er. c·ann or be rebed upon es,---

~

.

, des·

smce lhi me•L.oct 1- de . .

.

1L-A~

upon lhe Judgement of Lhe de- 1g nc r

1&11.

ur

o

-Stgn 2_s mainy ~

·

ii, '! he r ation.it mc-tb<ld :

Thi method i~ s tric:tJ} based upon well established scientific la\\' and relationsb ip .

• The rational method has a ' ~ f)· Jimjtc:d scope in arcJ!S of mechanical_eng i~e ~ng o th~ , . t

mcxhanic: and thermod}rnantics.. \\-ilere the a,·aiJ3biJity of la\\ and re) au o nsh1p~ i s r.ithcr ~

!iii, T he e, perimmt.af method:

·

ln the e,cpnjment.aJ d~ign method. the componenJ is designed ~-' · trial and _e " o r b~ed ~n eXis-,;,,

kno ~·l .edge and tM d~.rig,zed component is put 0 11 IM job . The mal are earned out intelLigenuy I

the interpretati on of the error is done " isely.

~

The e.°'"perime nlal design. infuc L requires the greatest application of engineering ingenuity.

2. Po"tt ~ -pe of ~le3Sllremeo~-:

These t)-pcs of measurements arc g eneral/)' used for monitoring ofoperational nzeasuremenr in co,u,-.

S)'JTem.

'ol

• 1ne entire area of au.1omarion and control is based upon power l)pe of measurement.s .

Q METHODS OF MEASUREMENT

The b~oag. class ification of methods of measurement is as foUo\\·s:

~ 1 comparison methods

.. . Indirect comparison methods.

J. Dir ttl comp.arfson method :

1n th.is metb:od the parameter to be measured is direcr!J· compared y.·iJh mher a primary· o r a secoruJar,

n~~

.

Di.feet comparison is quite commonly used for

ren:1enJts of length. However. for measweoll: ■

of mass the problem becomes much more intricate since iI is just 001 possible for human beinp ID

dis tinguish between \\1ide margins of ma s , .

•

Generali) . th:i method is not aJ\\·ays the most accurate or the best. it is no t sensitive enoup

also.

2. Jndir..-et c.:omparisf,n method:

ln this method the comparison i.s done with a sumdard through the use of a calibrat.t'd system.

These il»ethocb for me-45u.rements are used in th~ cases where lbe desired parameter to be

meaaor-ed i ~ diffi<·u/1 ro be mellJured dir-ectl)·, bur ii has got $0~ corr,/ation in tM some otl,a

partnnel4r H,·/uch can be e~il>· measured.

l::xampl-e: The eJiminat1on of bacteria in milk is directJ)' dependent upoo its temperature. Thus dr:

b~teria ~Jiminarion can ~ meaMlred indirectJ)· by measurin~ thL 1en,perat.url' of ,Ju milk.

-

In indir« I ~urement~ an e1npiricol relation is generally established between IM metulVOIIII'

a ctual/_ 11uuif' a,ul tlu: re Jults rho! ar~ desired.

• Wht:n che primary purpose of mak1og a mea-.11rewcm is co decemu~ quaJily of a produc:', •

'fUa4it~· sbowd be measured direcd>·· Huwe~er. in Ci5e direc.."t 11-eas11remear: is not~ . dlllt

indJr~,., mt,-, , .ure .oc:e 1 ~h<Mlld be made

··~--- -· ......--___ -------

• Tht• r11eas11rc.•111enr l \Jten1f

,n c,ist, rt!menr

·

U.Jt!d ' '' er1(l111,•,:n11g applic:nrio11 1ne1k c use of i11d irect n1t11hoth for

ptirpc,feJ

-

A me uren1ent ,,. lem

.

.

metbured \\' ·.i.

'

con,, t., o t a 1ra11ldt1c111l( elt 1nt>111 \, hich con ven, 1he quJnt,t) ' to be

tu, an ano/oqous J

/ Th'

IIi

.

means j11 the r, d

1.r:,,,, ·

'' ,,gna J ter being proce cd by orne i 111,: rn1ediate

n e to the end de\ice!> \\ h1ch pro, ,de t11e r;easurernent re ufL,;.

ffl MODE§ _9 F MEASUREMENT

Follo wing are the rl,ree mode, of

measurement

, ,J.,Pri mat) mea oremenc..

. ; .,' l_,.SecondaI) measurement ·

·'· Tertiat)· me.!! urement,.

I. Prima r) ffil· .t ~u rlmtnr,:

• In th1 c~e che SOLt"ltt 1

. . r eference srcmdards:.

,·a ltt' n/ a para1ttt>tcr ,s detcm 1111rd b_, con,paring it direct/)· i,·ith

• There • no cun,·er.~t<>n of mca.~ urand in ienn, of length.

/ _tum •/, \,-

t

I

•

,

~ffe~ huremenr of rime b)' counting the number of ,rroke of a clock

tr ' arcingof[\\olenehr h d

.

.

.

~i

"'

"

en erermanang the len~th of an object ,, ilh a ruJer.

(JJ ' arching of I\\o colou~ \\hen Judging ihe rempera~ure of o rt:d hor teeI.

1. ~ und:ir) n11:a., urc.:tnco(,:

TM indirec_t measureme,,rs in, ol,•i,,g .

1

-

one tran.r a tio11. tire called ' l'l·ond ur,

f.XUlll/J /c ,

_

•

Olt-a Urt:Ol l' nl~

,,, The pre <iUre measurement by manometers.

,,

The temperature me as urement by mercury- ,·n-gla,

rhc nnomeren..

.~.

fC:rti I~ lllt:J'IUrt U1eO(<,;

TM indirect nzeasurements tnl-'Ol vino •

r,

t•vn CrJn ver:ri{Jnf' art• rail ed te-rti"'--

1-Au,,,of ,

.

-

-

-

-

-

... .'

m J,ur emc-n l

•

..

The mea\uremcot of remperaLUre o f an o bjec t h \' therm

•

.

.

(Lemperdrure of o bject ) i\ tran,m ·,, d

h"

ocou plc (Fig. l .J J. The pnl1lar)• ignal

a func tion of the temptrature (fir:r ~ ro ta ~ ;;noc◊upl~ ~h1 h generate~ a ,·oltage whic h •~

a voltmeter throu"h a pa,r of w,·...e

rThan\ a11tJ con,c:r,ion,. Th~ \ ohugc in rum •~ applied t~

.

~•

•· ~-

e ,;econJ ·on,

·

h

~ruary ignaJ i) lrdJl mitred ro bra,n o f the! ob ~~er _t .!~1o n • l en voltaie iolc> length. ll1e

Temp

Pnma,y , 1p..J

flN

tran.lclto0

(The,,,..,. •11,pk)

Tatip tcM\ffltd

UJ1u \t1J1.

I \r,1~

'

I

~

~ SltPl,11

~

·onJ

lranJ.Clon

(\\.llDUdcrt

~

-

-

\ohap COD\cncd

l1\k'llcaath

Tertiary maaaoremen1. Mea1urament or temperature by a

Tct"l1.11)' , ipal

I Ob.cncr·Jo

~

--

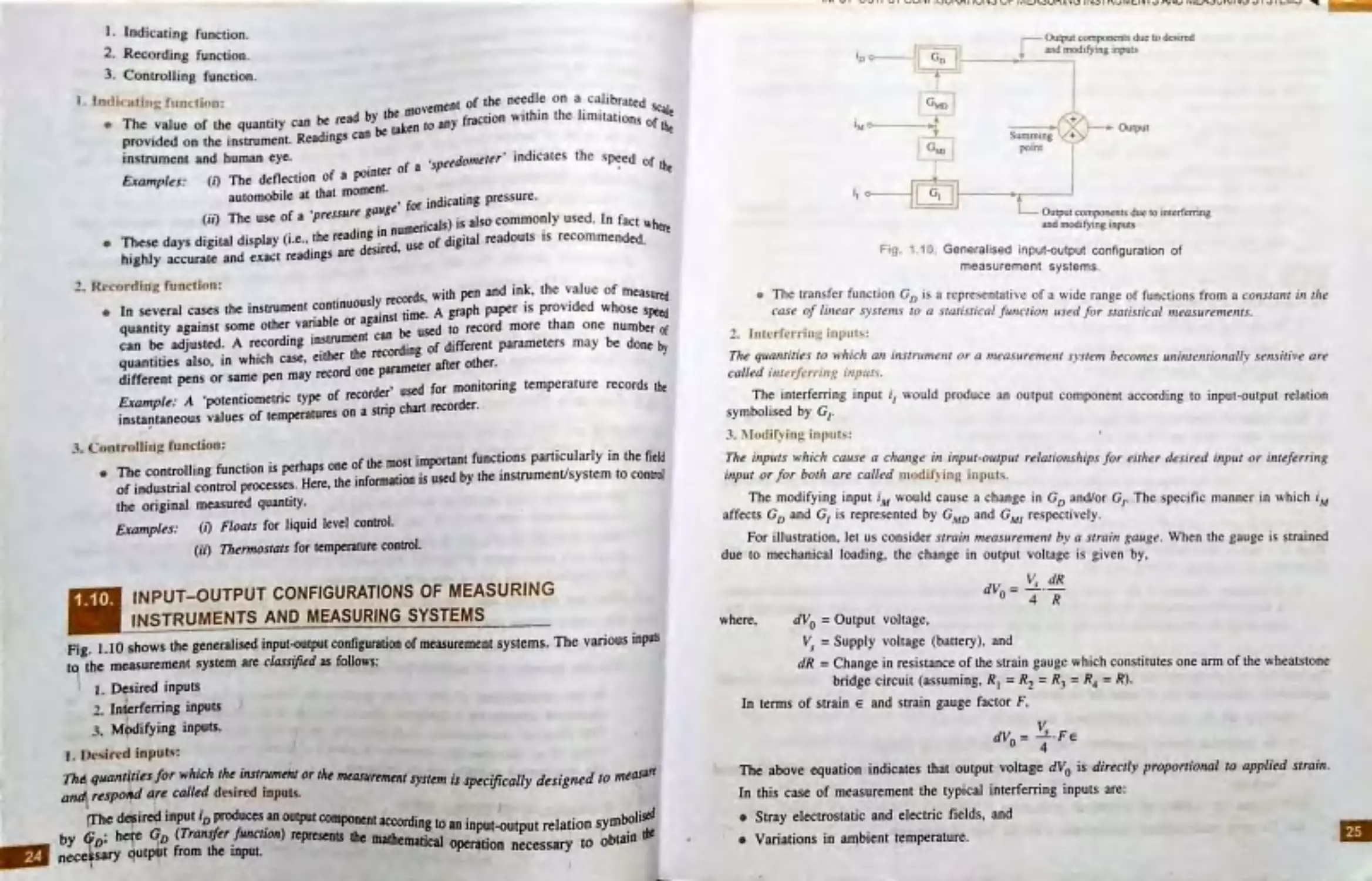

p bt:Nt:KALl~tD MEASUKf:Nlt N' ~T

~I~··· ,... ·-.. -

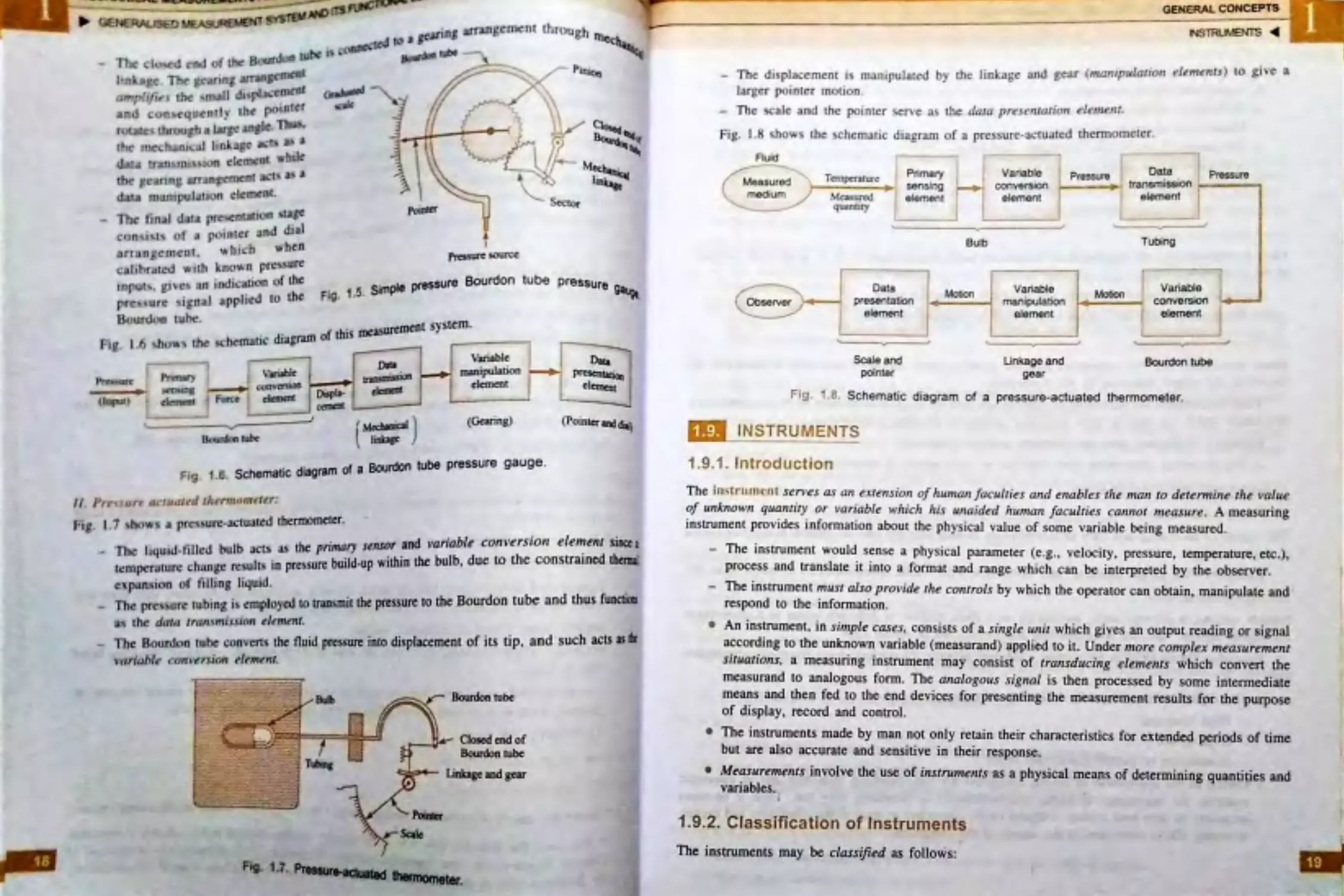

be pre •ure gtluge.

.

.

.,. b uBourdontu

.

(i , The n1easure111ent of st11t1c pres ure Y .

.

ft b rna ns of an elcctnc tach o1neter.

.

•

d of a rotat1n.g . sl1n Y

.

, , i The n1easure1nent of the spe~

ld t·tke-S place 1s ct1Ucd the l r .1,, \lu

•\ tion of n1eusur"1

•

tr

Tbe unit of a 1111.!as uring systcn1 ,,·here tnln!i a

or tr:111, ltttc,r .

d the)' include the ,vh o \e mn

.

.,,

·

f'\' s)r, ten1s an

.

.

..

.

gc or

•

•

Majority of n,eas ure1nent systen1 .u-e tcrtlU •

.

.

1 and clectro-pneu111au c 1nstru1nentli.

.

.

.

.

.

l~tro-n1echan1ca

me.chan1cul . e lectncal, pneumanc e

.

.

·ar egories:

di ,·d •d i11to foll(}\\'tng tu O <

Mea:sure1nent-s may al . o be 'i e

.

.

de,·i ce co111ac1s the co ntrolled mediu

.

, r ofthe n1eusunng ·

rn.

t . t ~t,1\t.,c.:t l) J>l: . ln this case the senso

.

r tl1e controlled medium.

h

or dc>e'\ 1101 co111ac

~-

,011-~ ontact l) pe. Here t .e sens

•

.

d otl1ers.

.

• I radioactive an

•

Non -contact mea · urements tnclude op11ca •

.

1.8 .

MEASURE

MENT SYSTEM AND ITS F1JNCTi0NAL

GENERALlSED •

ElE MENTS

-

___ __ ______

.

-

d \vith different cornponentc; (called ele111e111s).

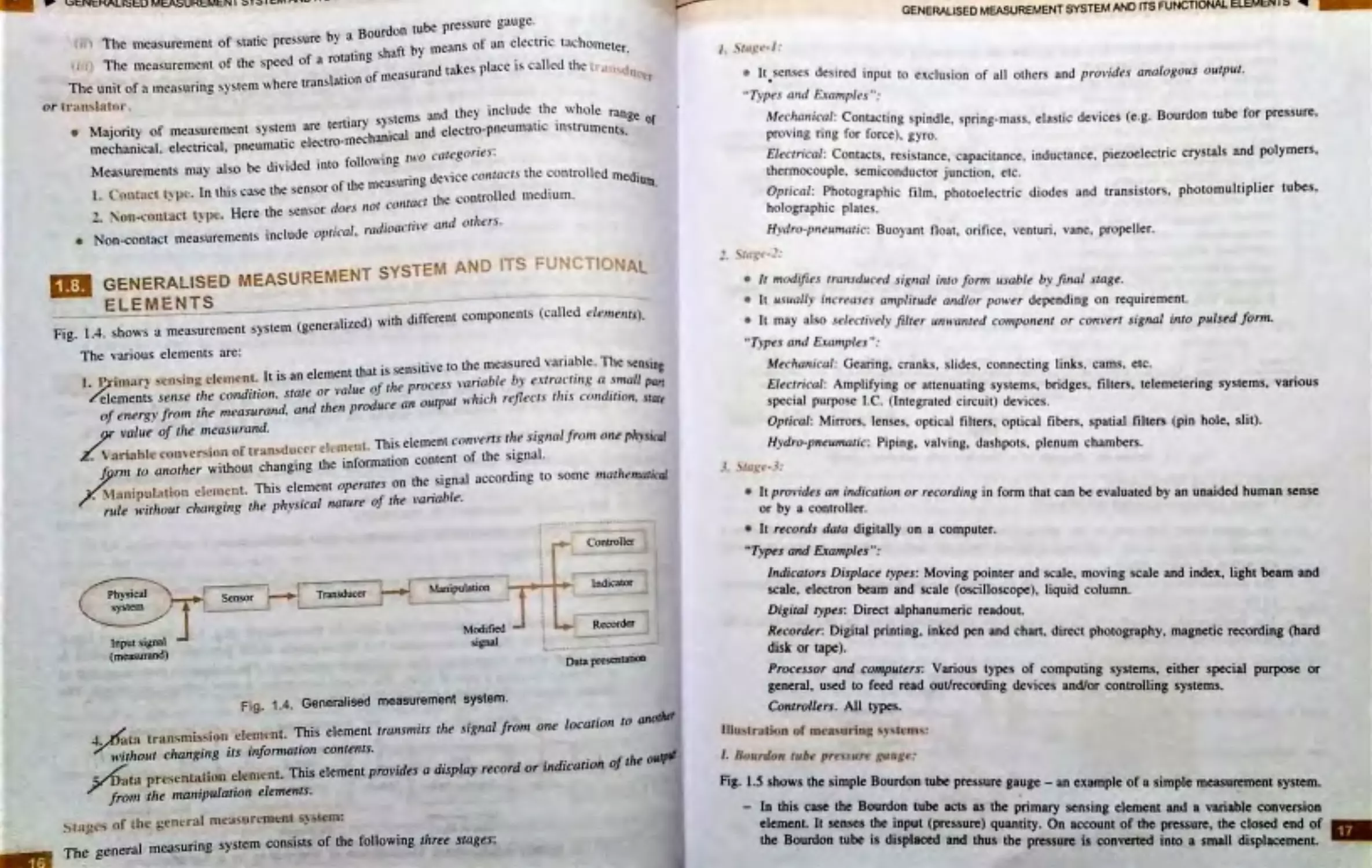

1..:1. sho\YS a measurement system (generali ze )

Fig.

-.

The vari o us elements are:

·

blT

.

,

·,n·ve to the measured var1a e . he ~ensing

I•

element that 1s sen.

.

t J::itn.1ri sensin g ele-1nenl. t ts an

/

cess variable bv e.-r rra ct111g a snwll pa,r

·

·

••

\'alue o r ie pro

·

.

..

elen1entS se11 se tire condtt1on. state or

J outpi,r ,,,lzich rej1ects 1l11 s co11d111 on. ltarr

of enttrgy from the nzeasurand. and then pr uce an

value of 1l1e n,easurand..

Th' 1

ment converts rh e sig11al f ro,n 011e ph)•siral

•

.

••

tnt>1\ t

isee

•

ariuhlc co11vcrs.1ot1oftran du.cer cl . _,

.

content of the s ignal.

•m hangino the t1u ormauo n

/j m1 10 anotlier Wt out c

e

h . . , , a c c ording to son1e marlzemarical

·

t nt operates on t e Sign'"

\lanipula ti<»l eiem ent. This e en1e

h.

'abl"'

·

·

I ·I a111r•oifte,an

~.

n,le ,virl1out clianging the P iys,,ca n

t

Rtiysical

system

Input signal

(measurand>

I

l

•

-

Transducc:r a

-

~ lAl l••r-

_H

I ..f 1.•- -in11lation

Scnsor

, c,___

_

___

JL_-

Modified

signal

Fig. 1

_

4 _ Generalised measurement system .

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

t

.... -

Controller

-

-

Indicator

Recorder

-

.

•

·--

--

•

Data p.escntatioD

4. at.a tran fillb I

c

.

:.r . ut changing its infomwt1on contents.

__ ..-1

wur,o

.

d . d " tion ofthe o,,,r-

t. element. 'Ibis element provides a d1splay recori or in ica

ata pr-e. .,;tnt.'l ttm

fr-c ,11 the manipulation elements.

~ ta ut.•s of the general measur~ruent S)~rem:

,:,

~

I A~~ uring srstem consists of the following three stages:

The gener,a m~

•

GENERALISED MEASUREMENT SYSTEM ANO rrs FUNCTIONAL EU:Mt:N I:) ~

/. .\t11,.:v-l :

•

It.senses desired inp ut to exc lu sion of all oLhers ttnd provides analogous o utput .

" T)ipes and Exanipfes ":

Mechanical : Con tacting spindle. s pring- mn.ss . elasti c devi ces (e.g. Bourdon tube for pressure,

pro,•ing ring for force). gyro.

Electrical : Co nta cts , resi. tance . capa citance. inductan ce . piezoelectri c cry stal s and polymerS,

thermocouple . semiconductor junctio n. etc.

Optical : Photog raphic film . photoelectric diodes and transistors . photomultiplier tubeS,

holographic pl ates .

Hydro-pne11n1atic: Buoyant fl oat, orifi ce. ve nturi . vane, pro peller .

• It modifies trwisduced signal into /om, ,,sable by final slage.

• lt usual/)· increases ampli111de and/or polver depending on requirement.

• It may also sclec tivel)' filtf!r un1i1anted con1pone111 or convert signal into pulsed form.

" T)·pes and £.xan,ples " :

Mecl1w1ic,1l: Gearing. cranks, slides. connecting links. cams. etc.

Electrical : Amplify1ng or attenuating systems, bridges . filters. telemetering system s. vari.ous

special purpo e I .C . (Integrated circuit) devices.

Optical: Mirrors. len ses . optical filters. o ptical fibers , s patial filters (pin hole. silt).

H)·dro -pne untaJic: Piping, valving, da.-i hpot s . plenum chambers .

3 tu~,• 1:

• It pro '1ides an indication or recordl'ng in form that can be evalu ated by an unaided human sense

or by a controller.

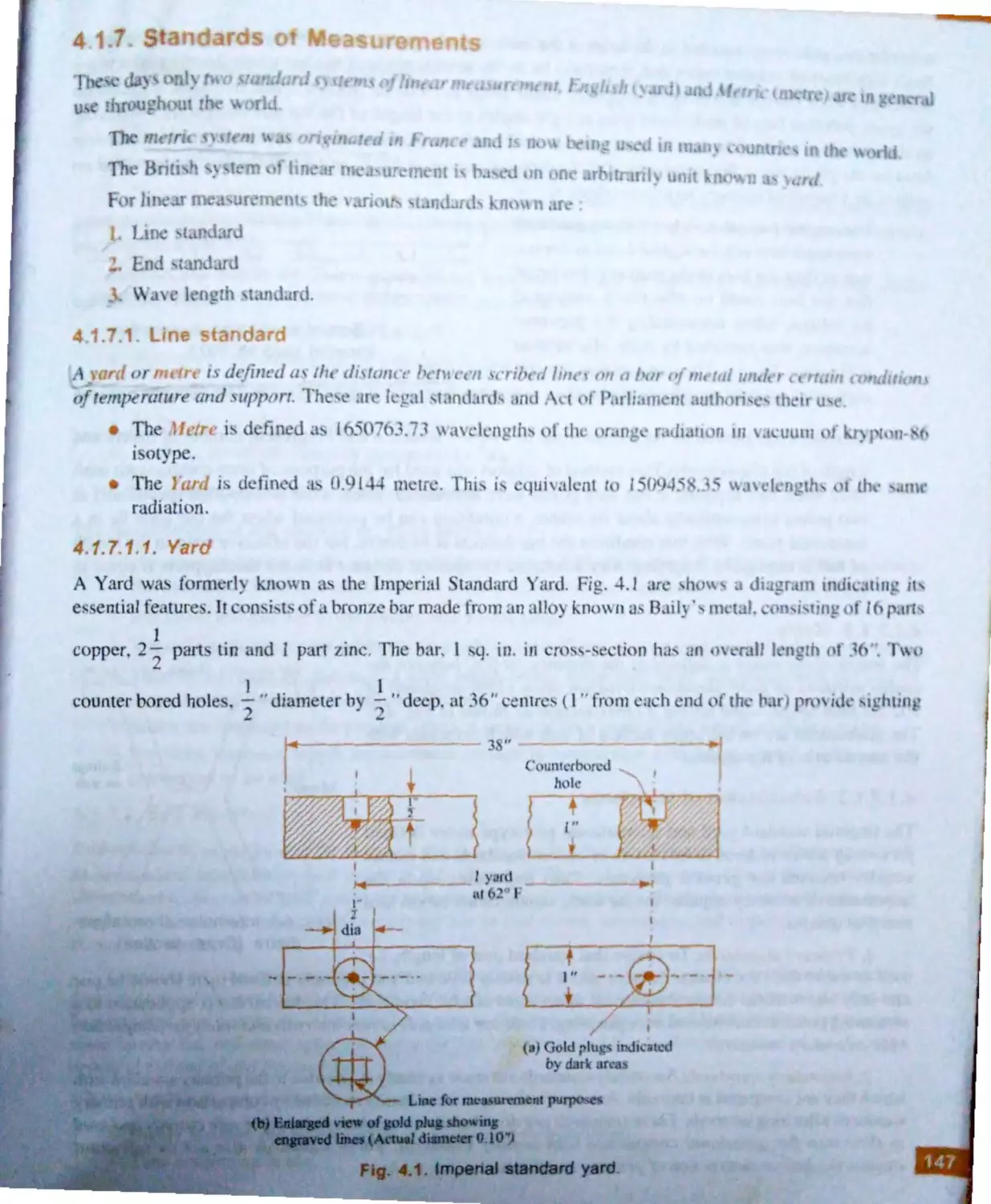

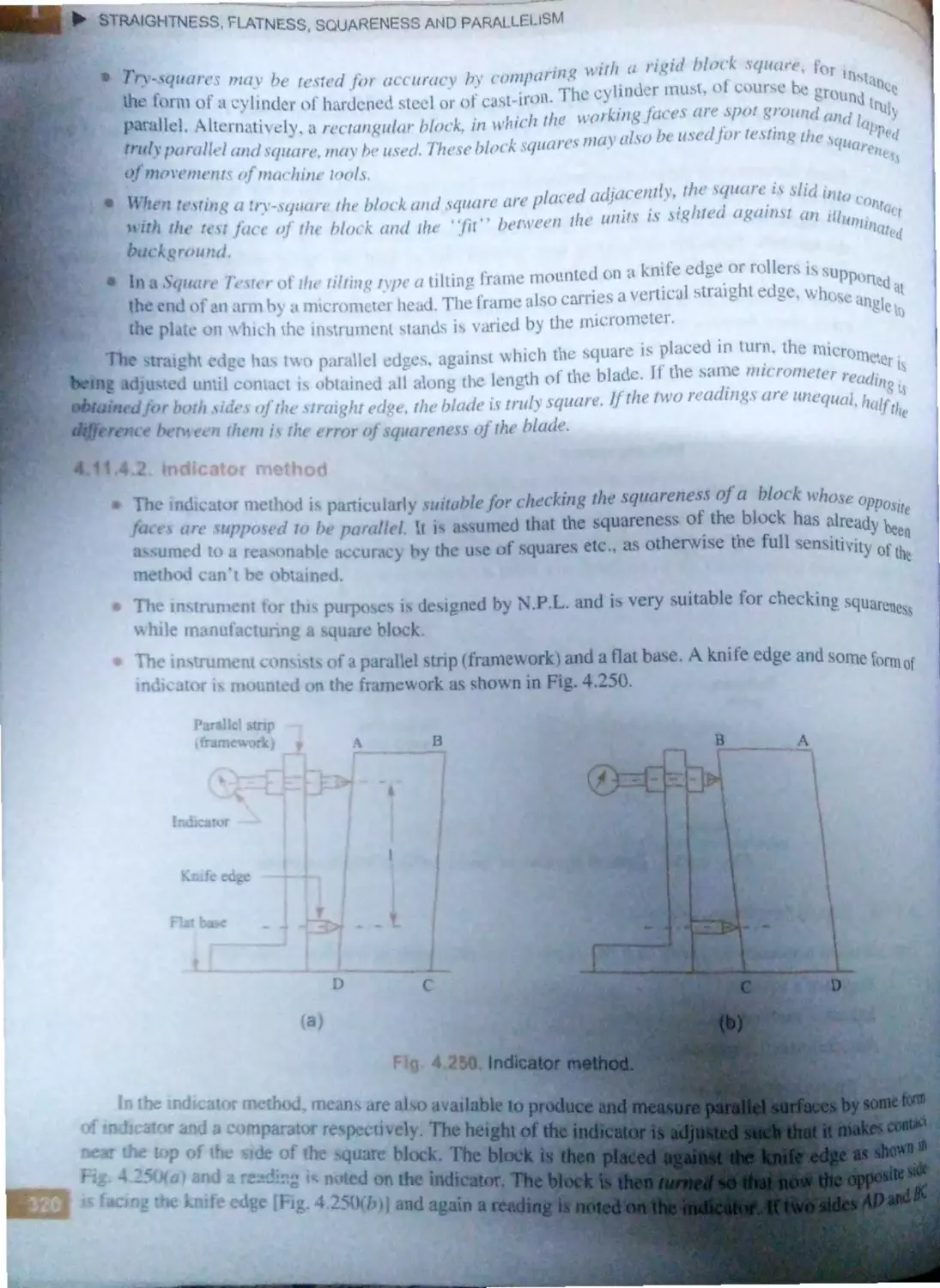

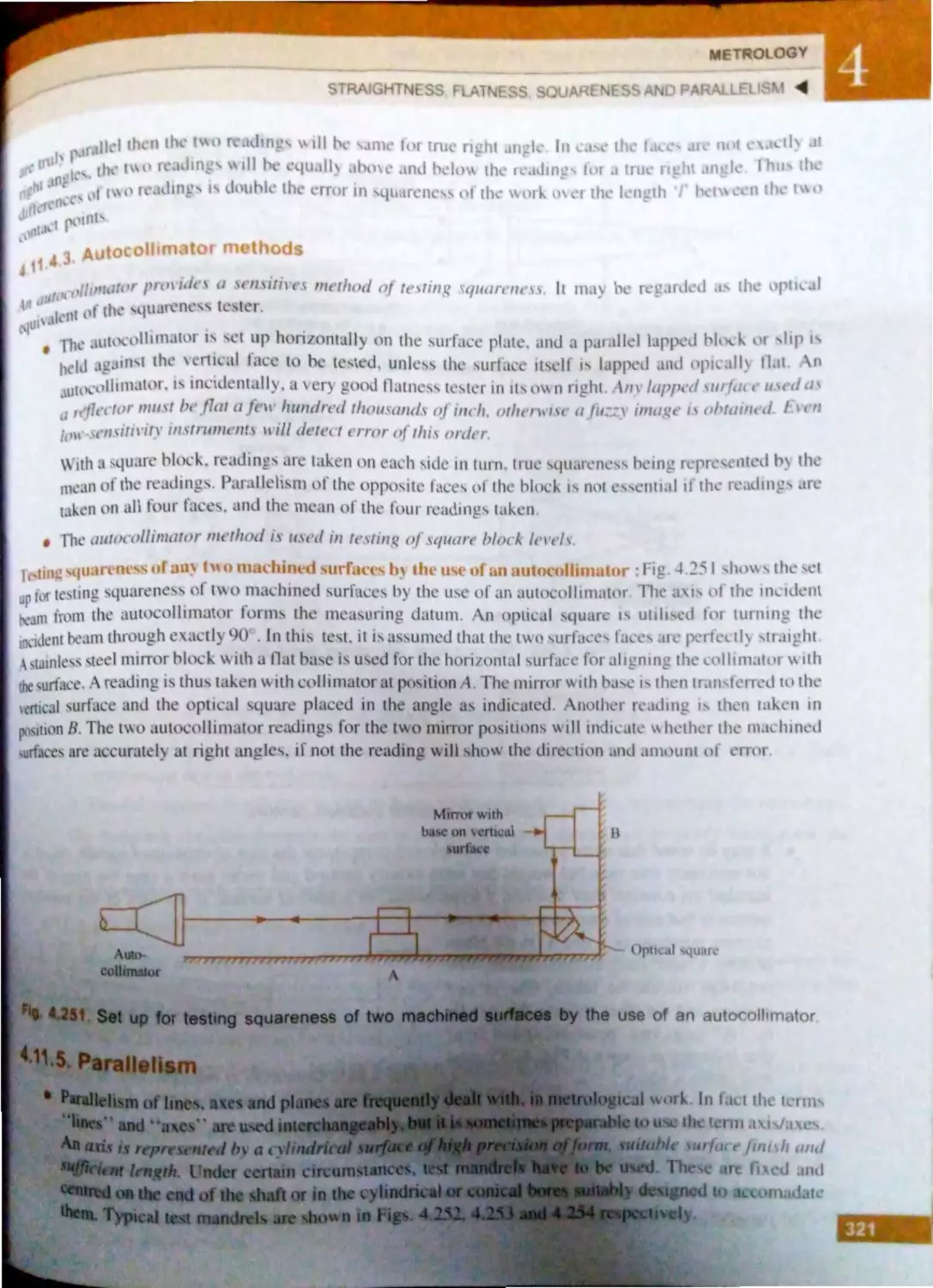

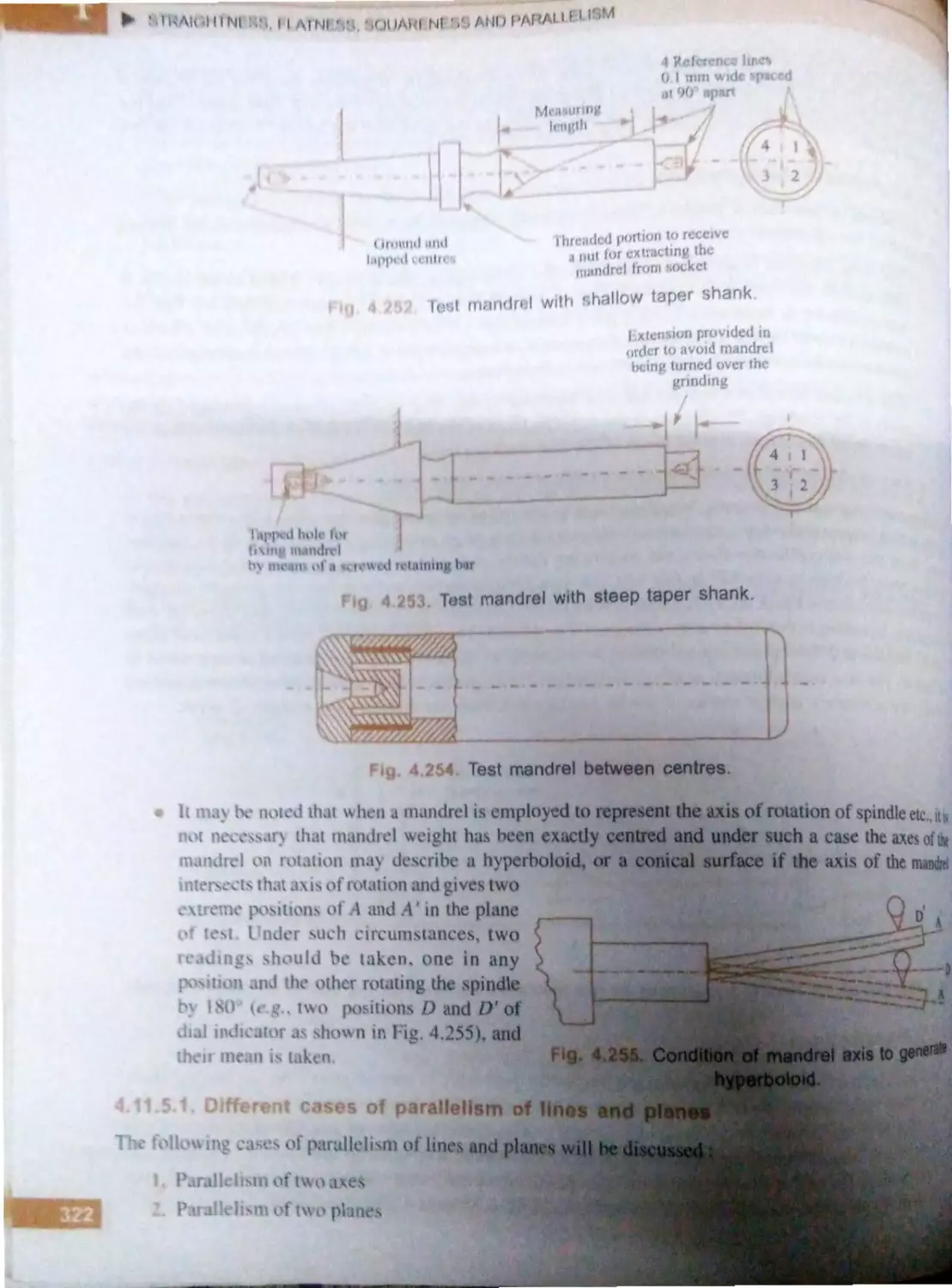

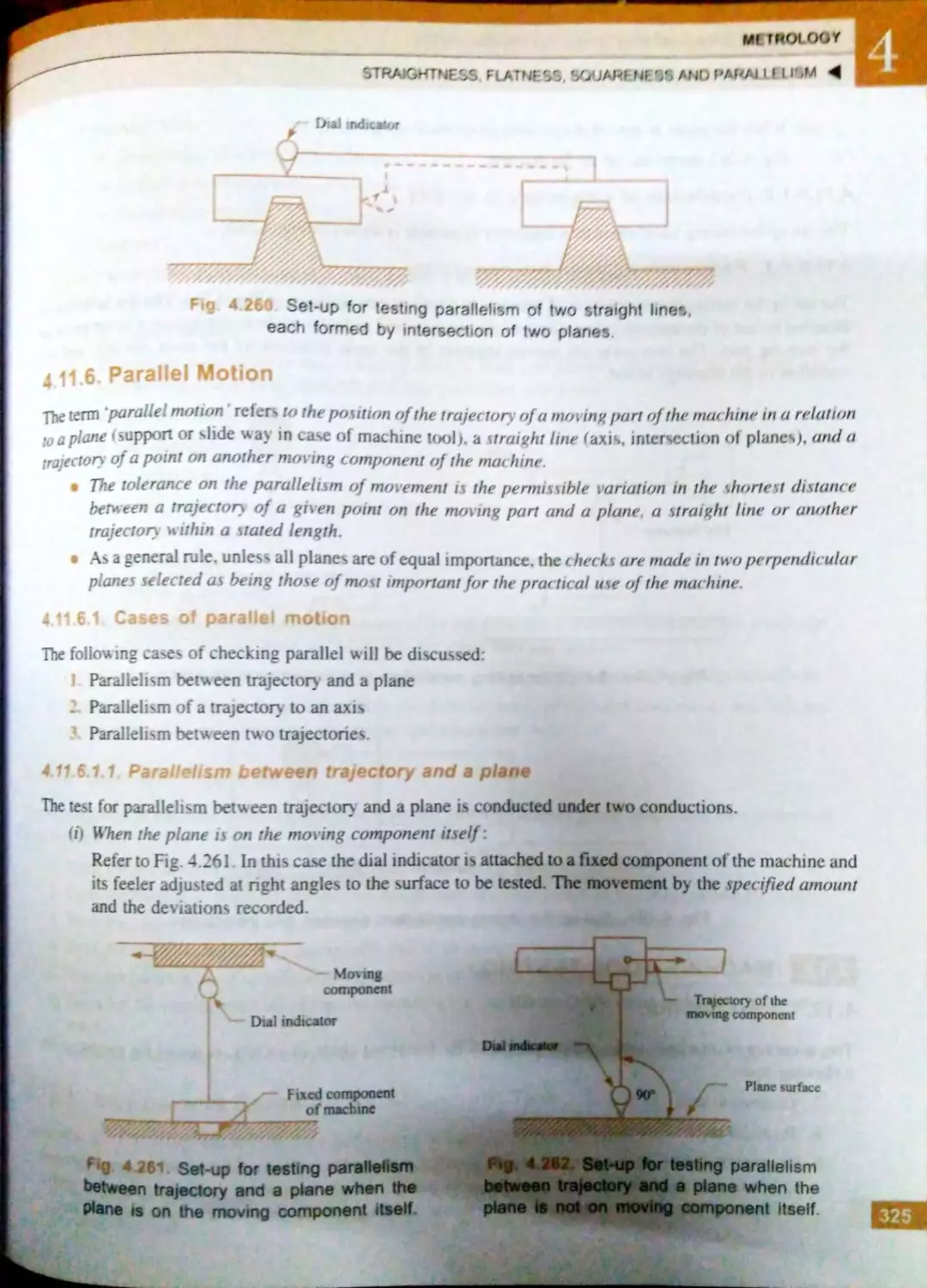

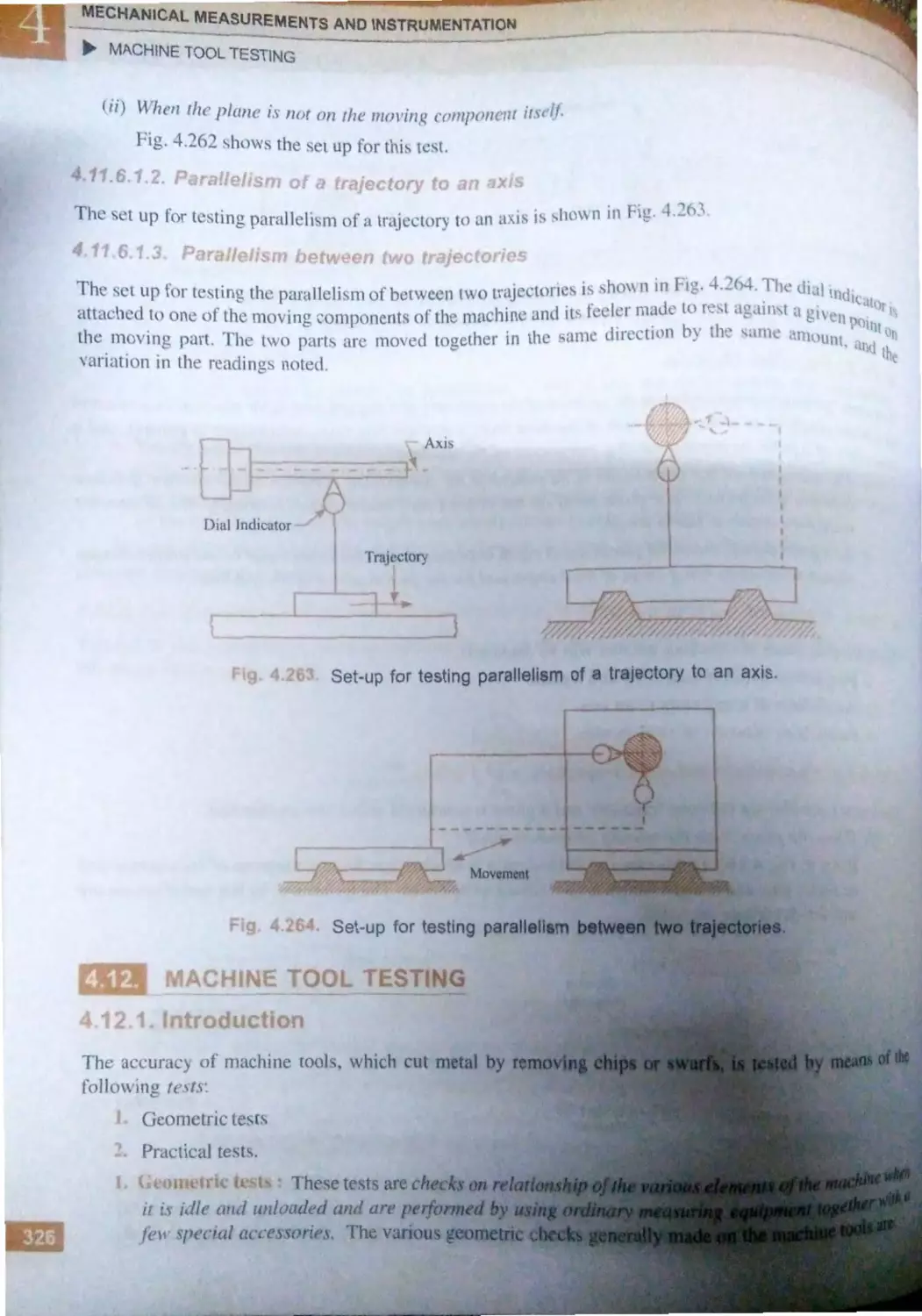

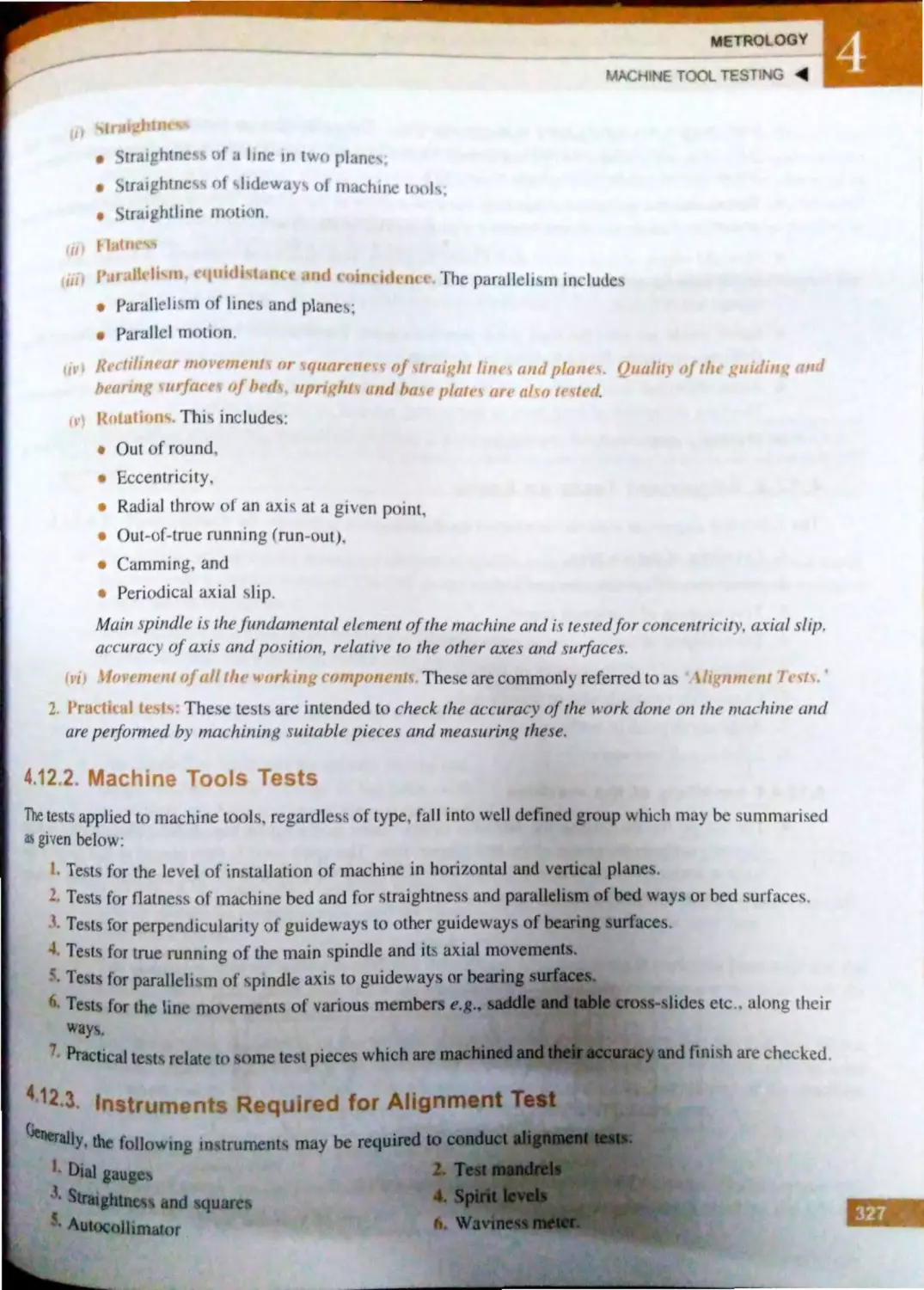

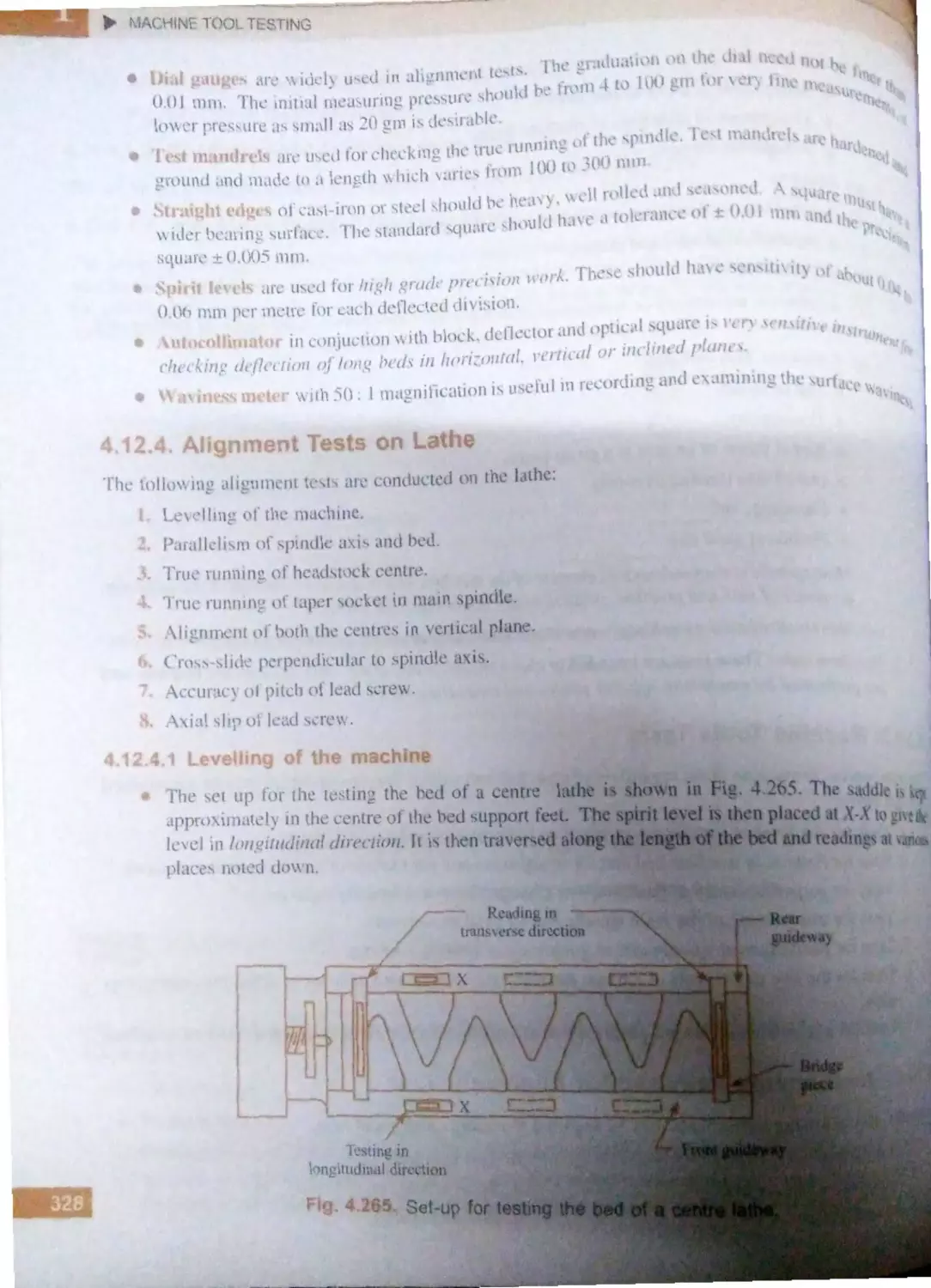

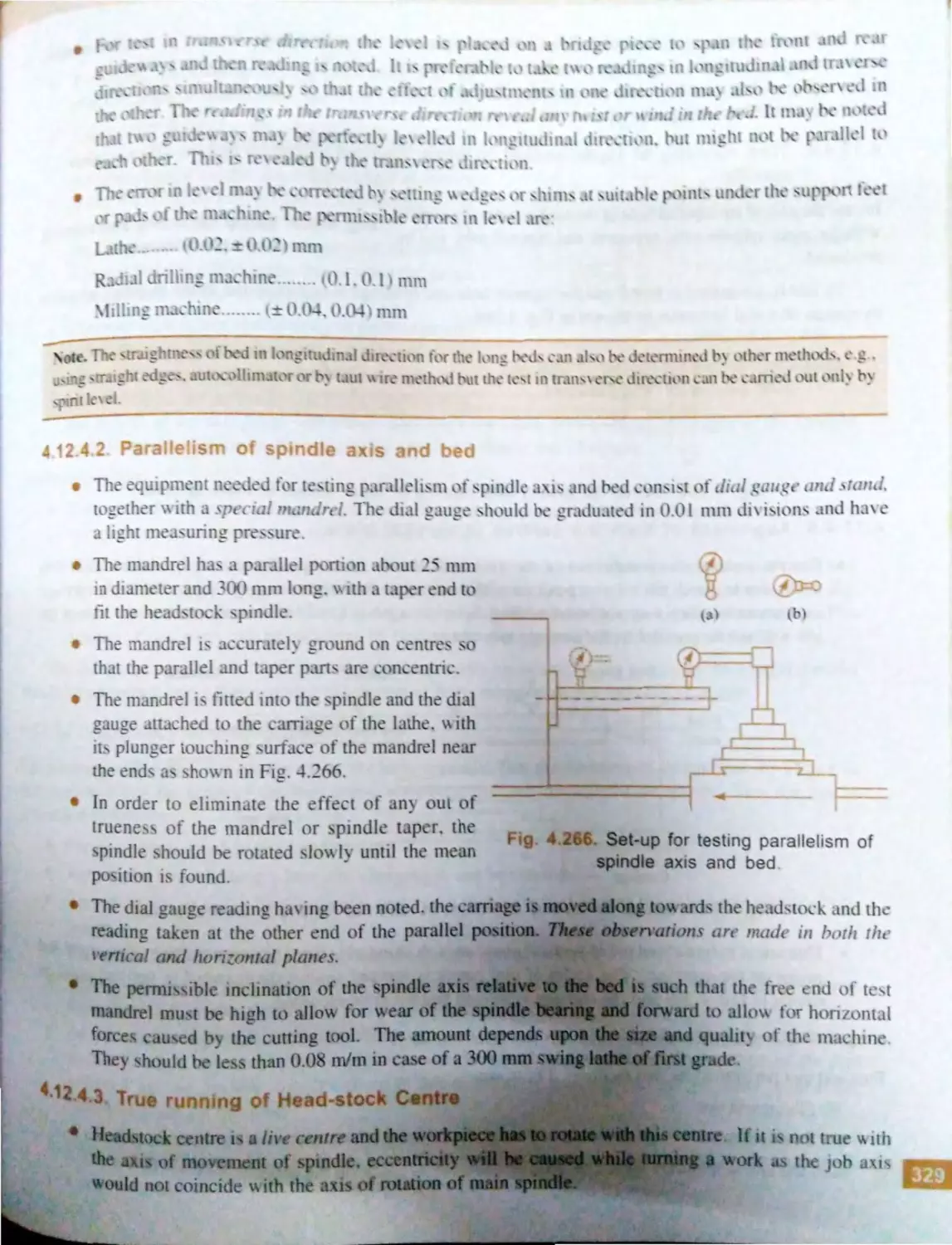

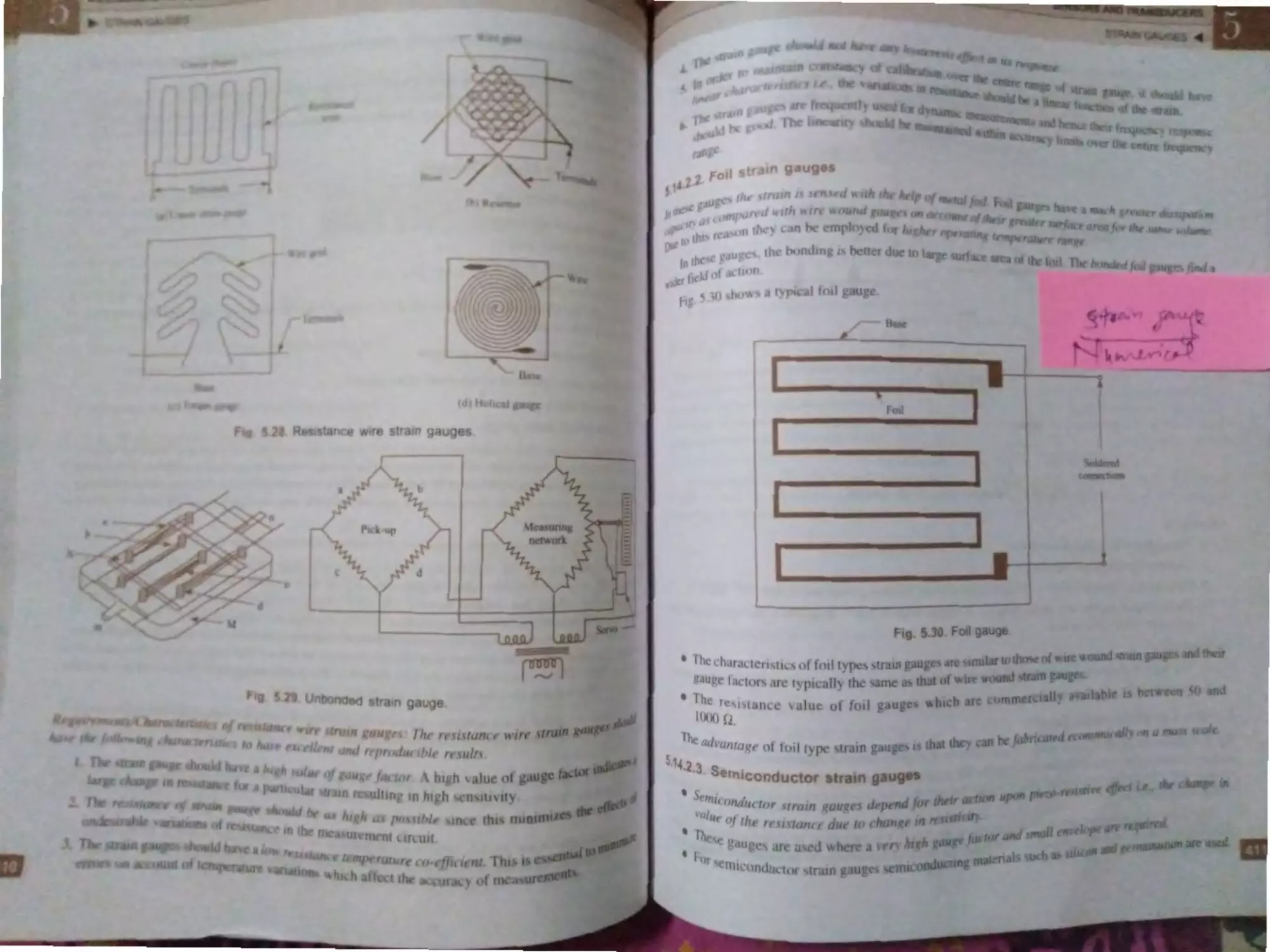

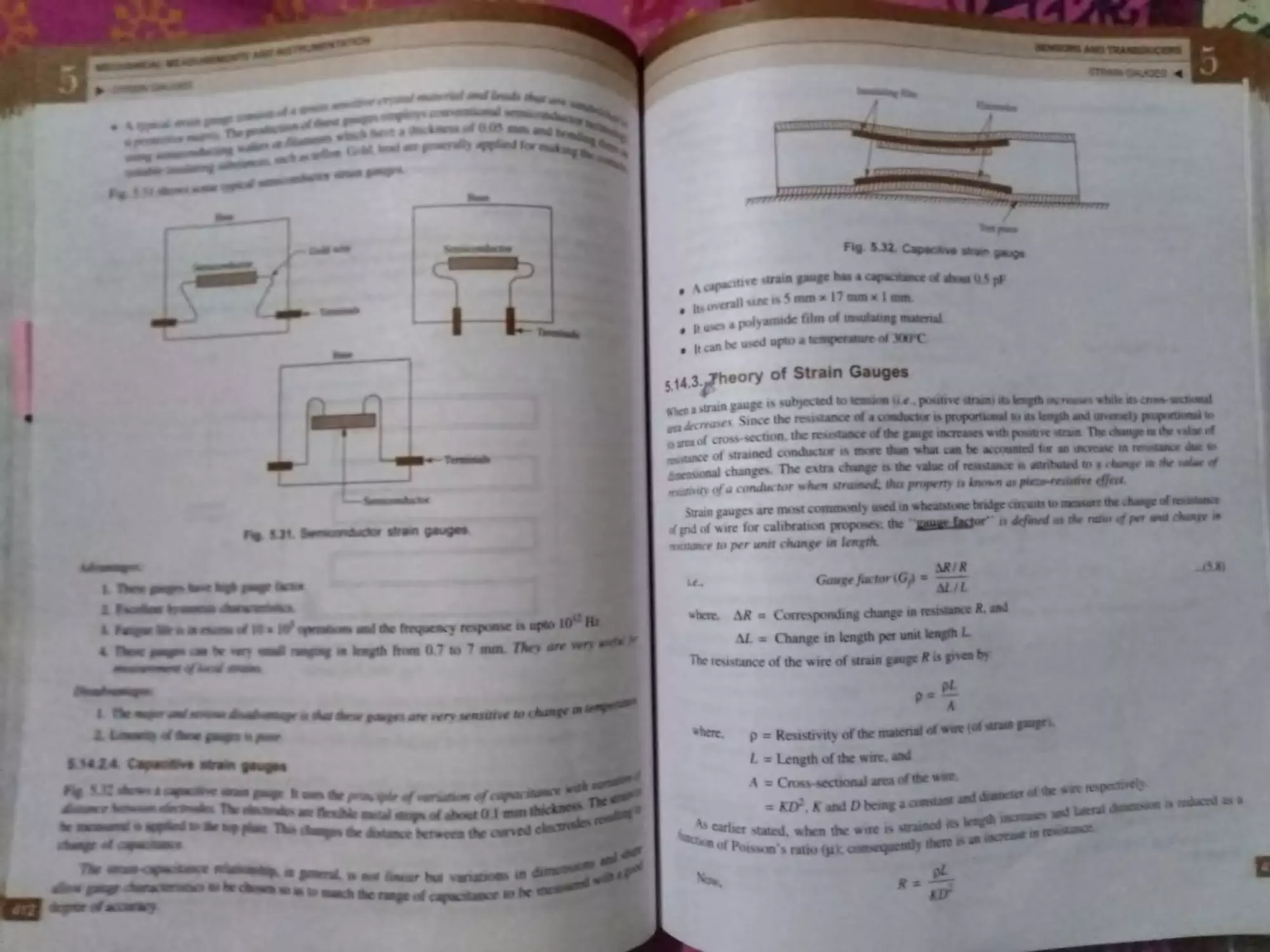

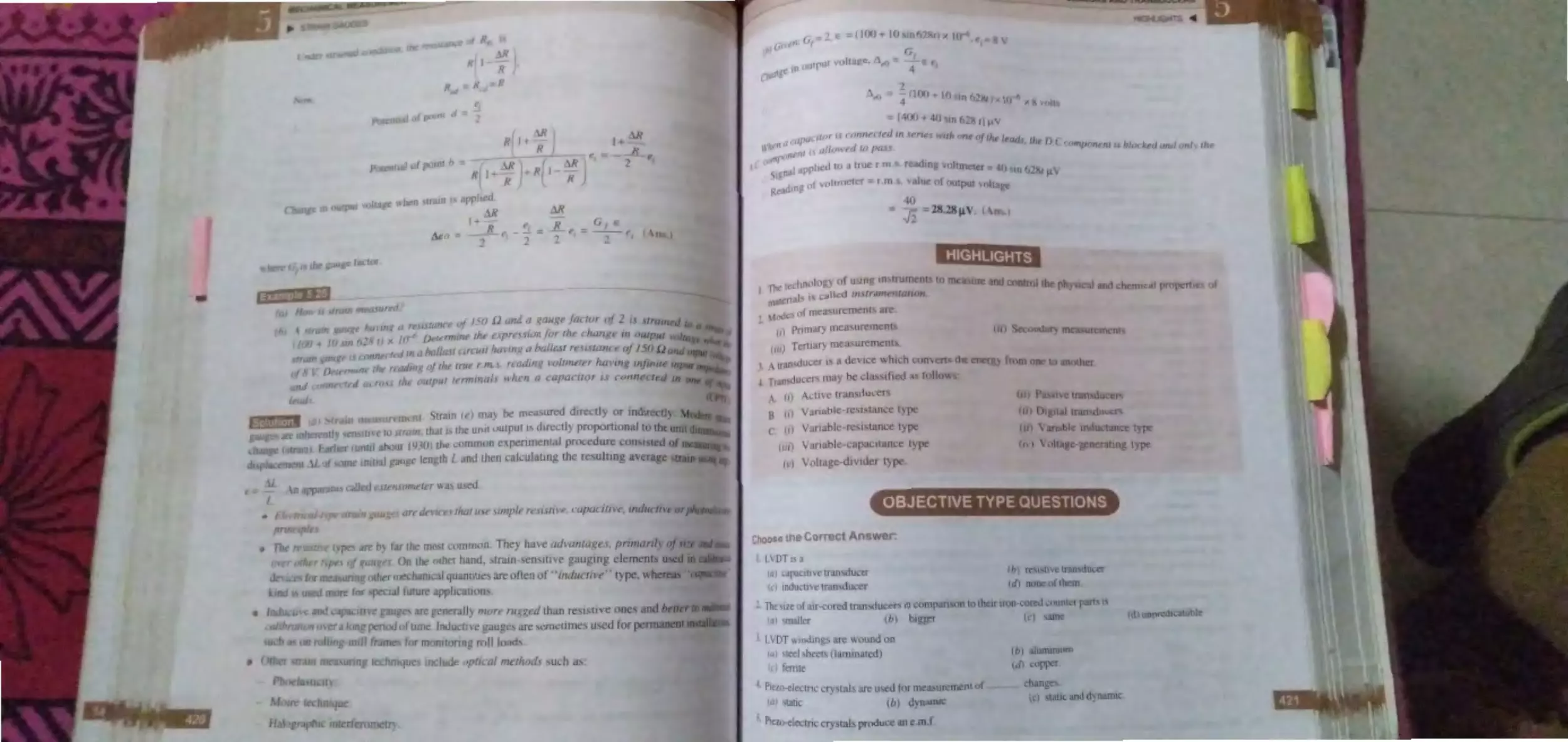

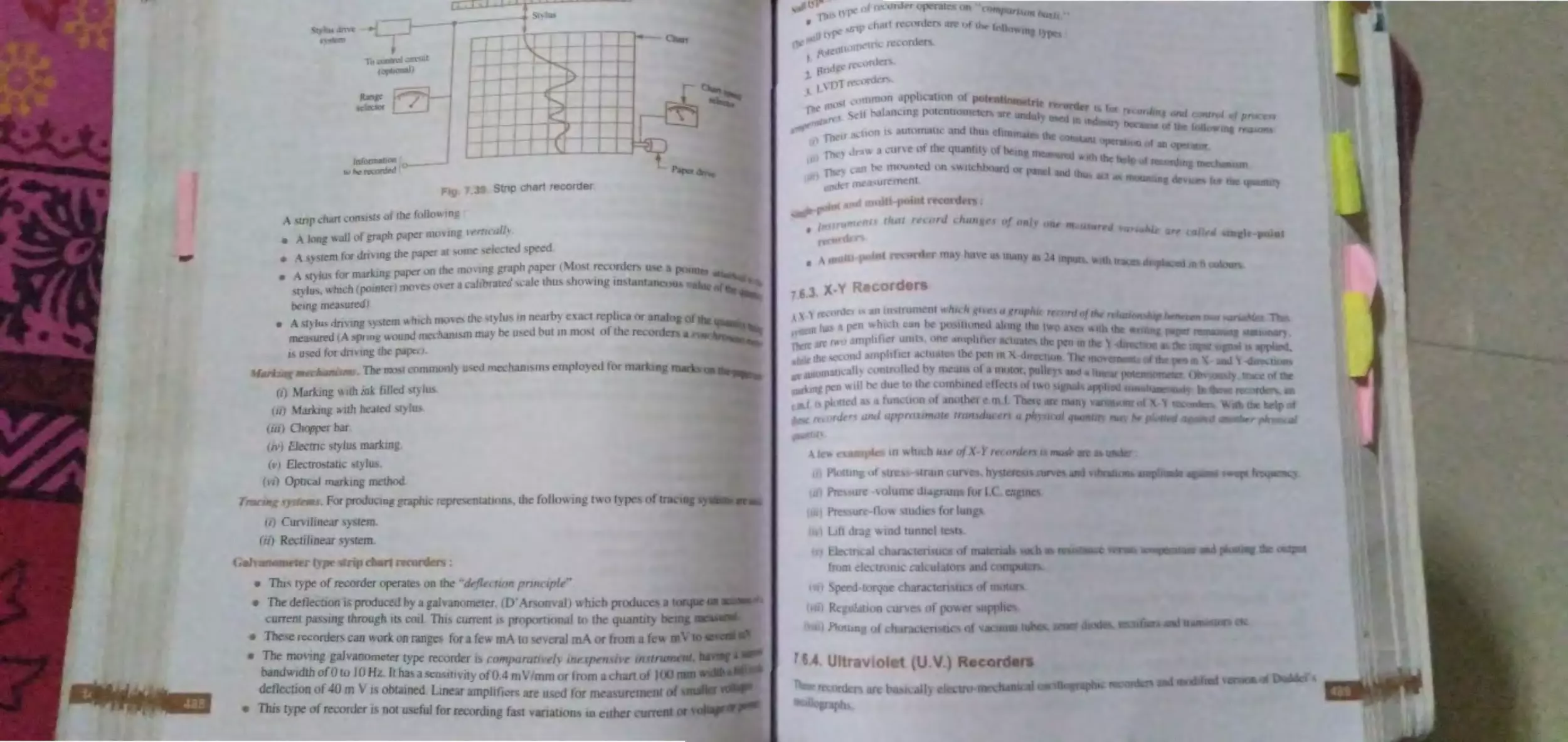

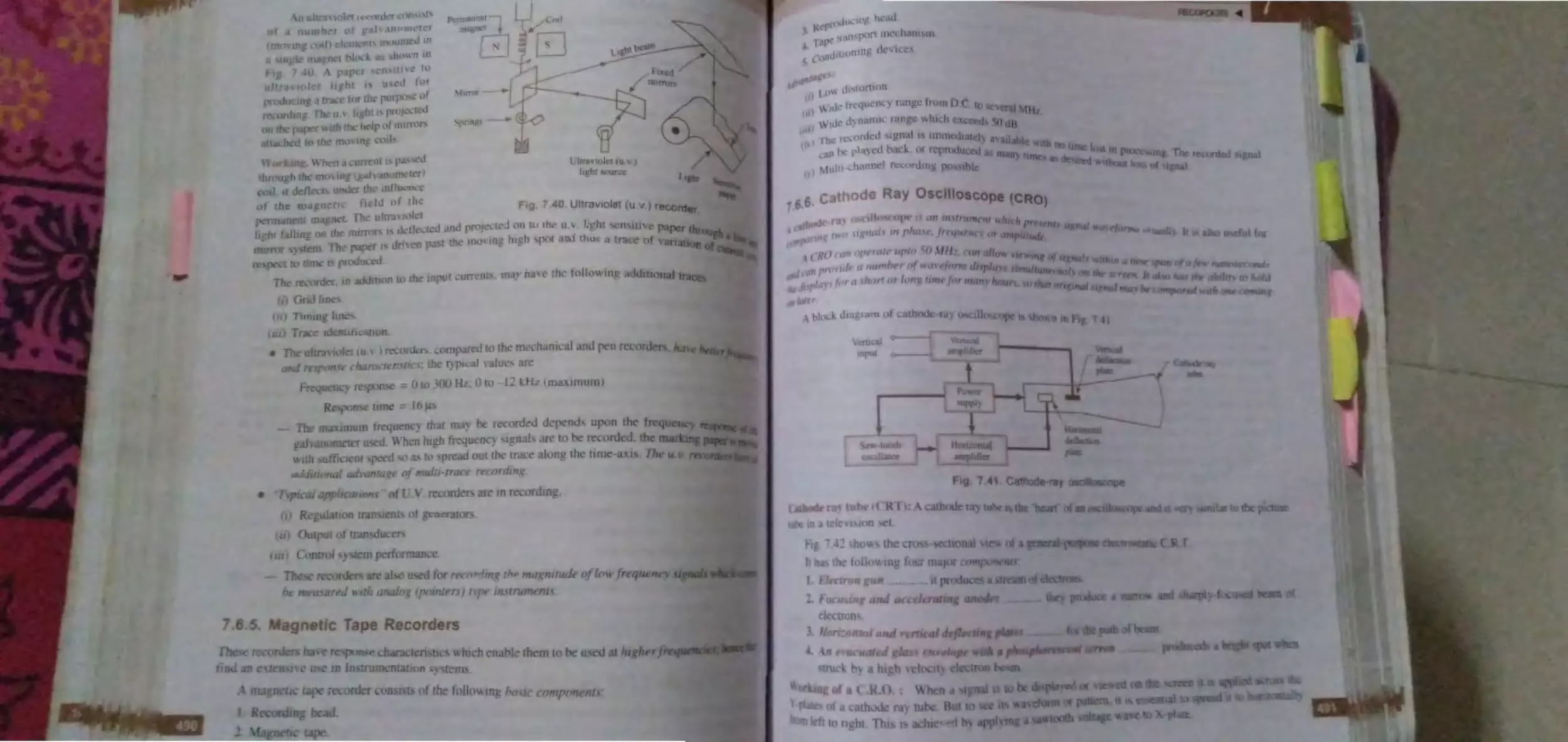

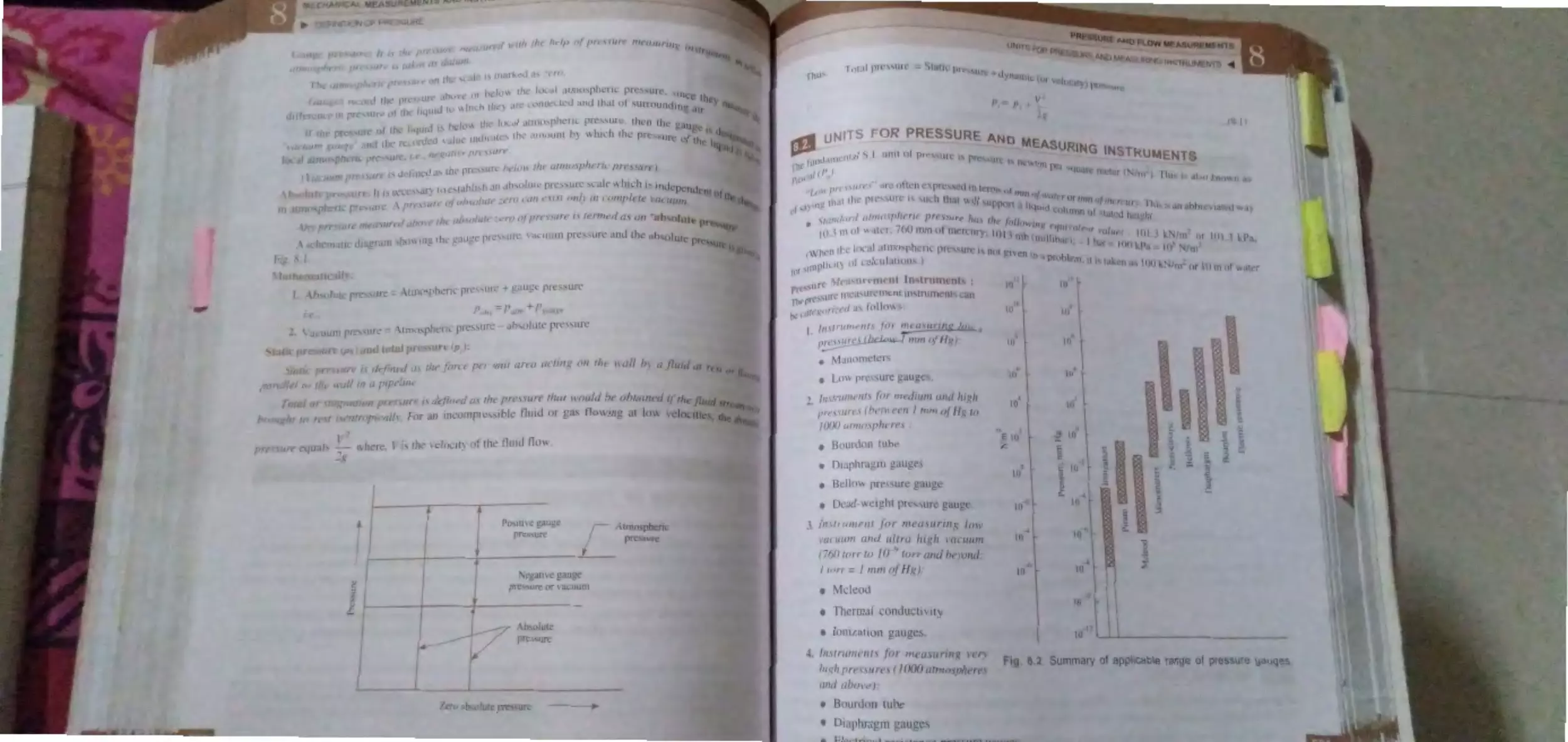

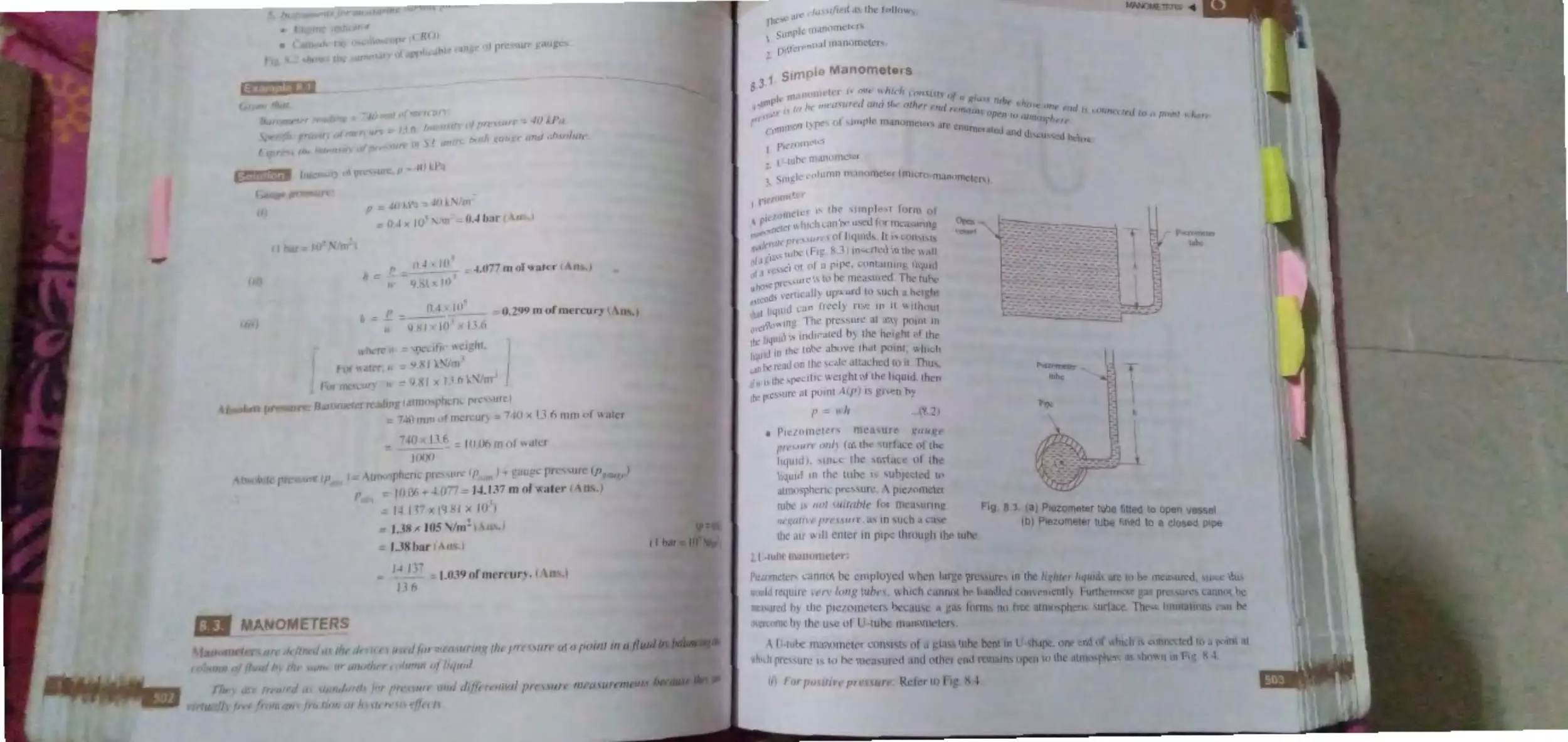

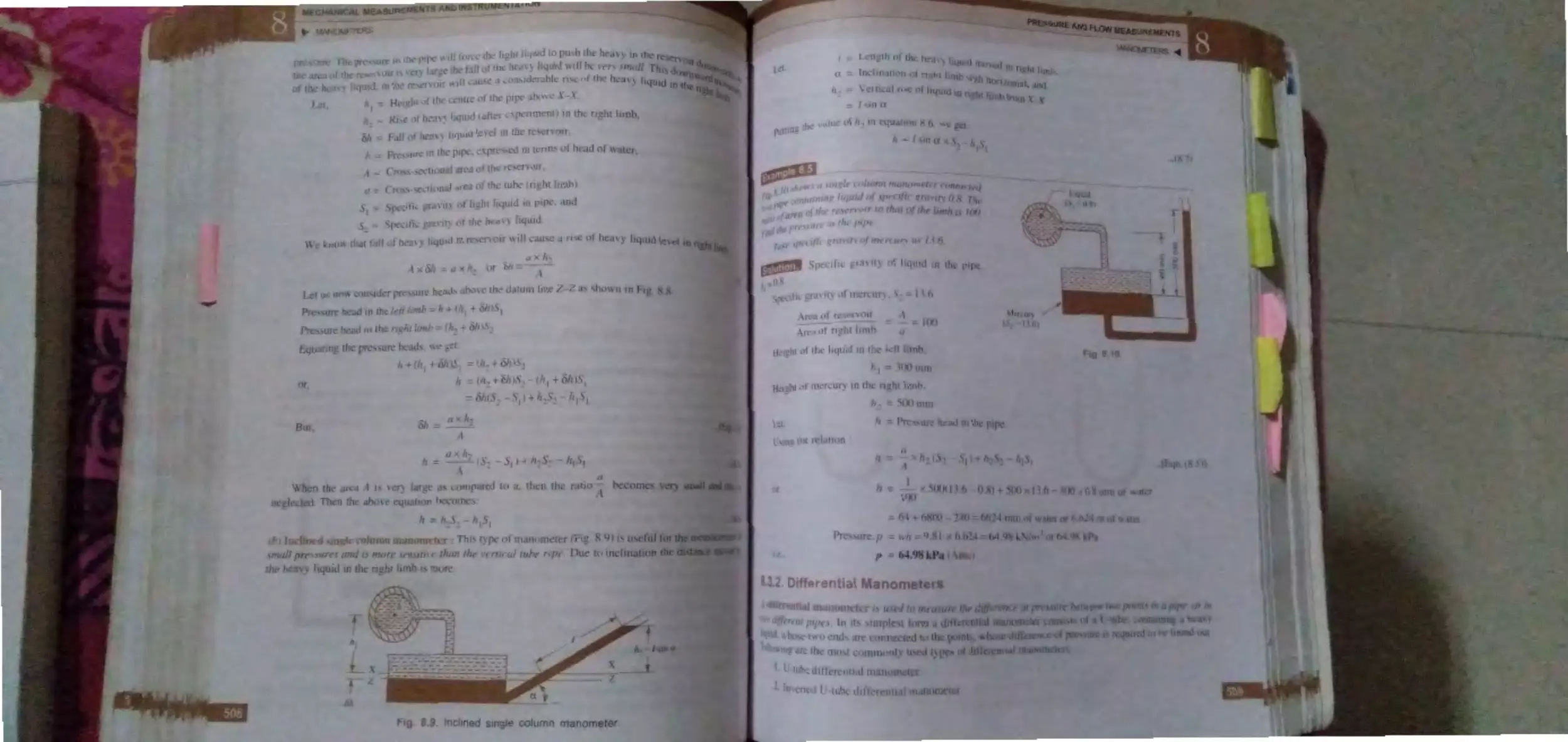

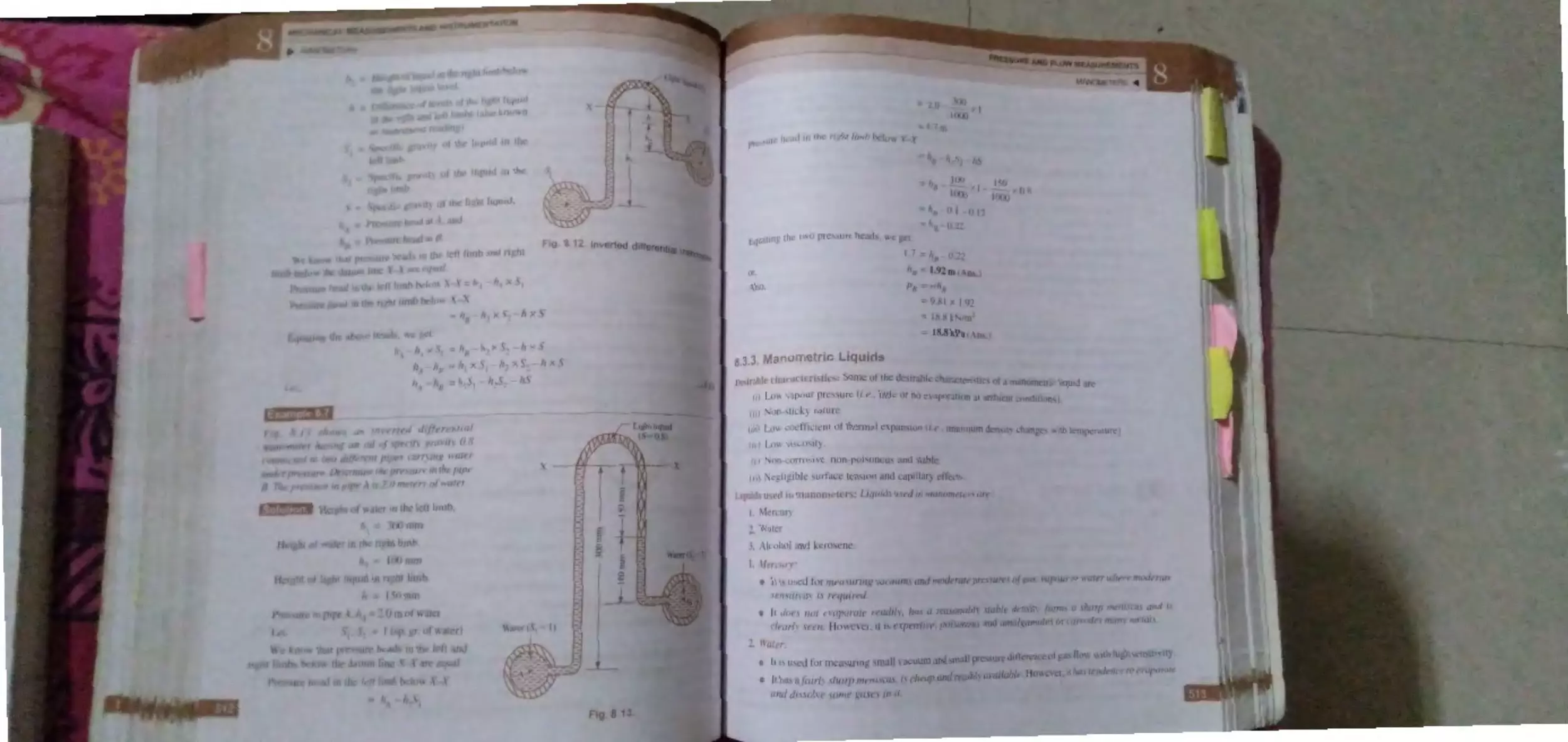

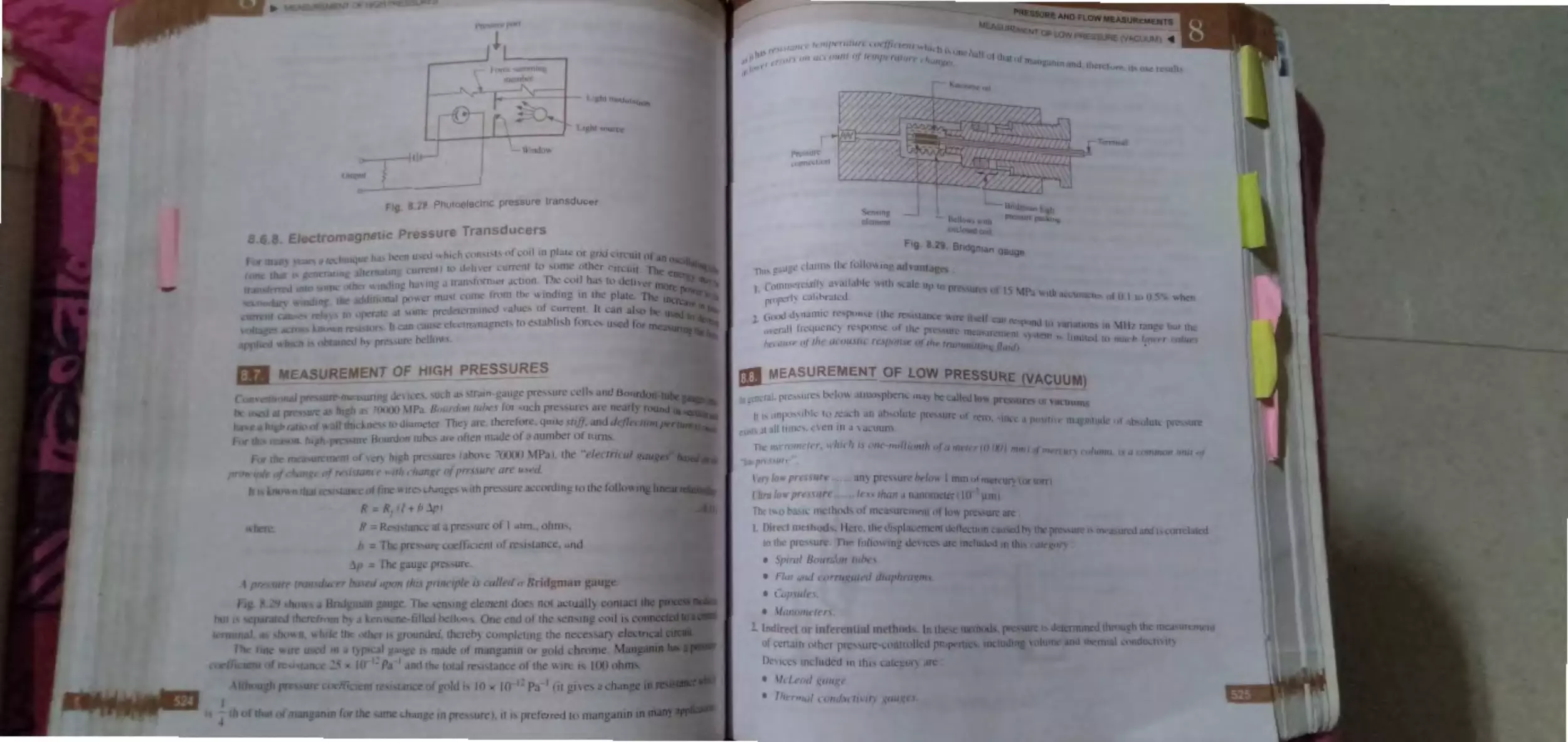

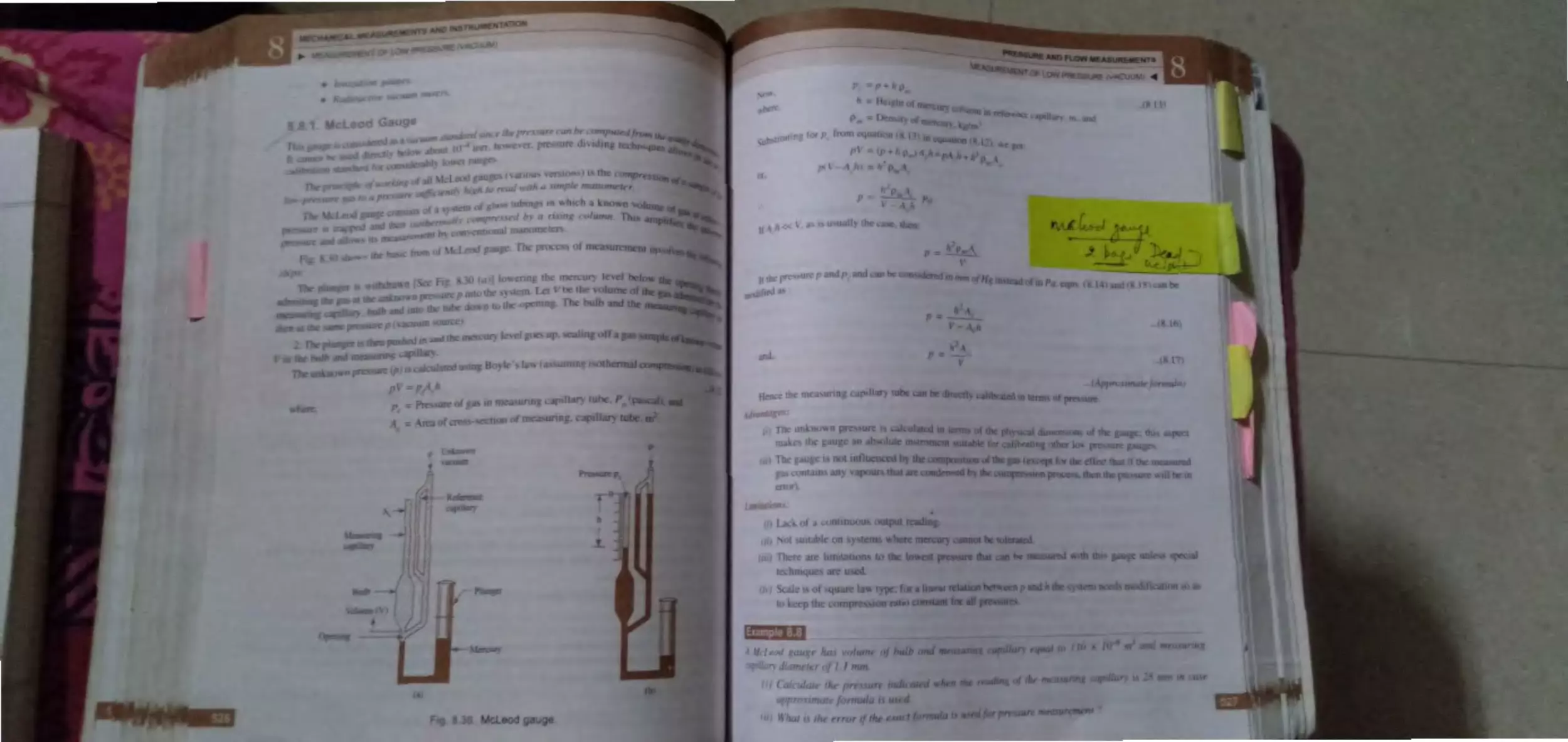

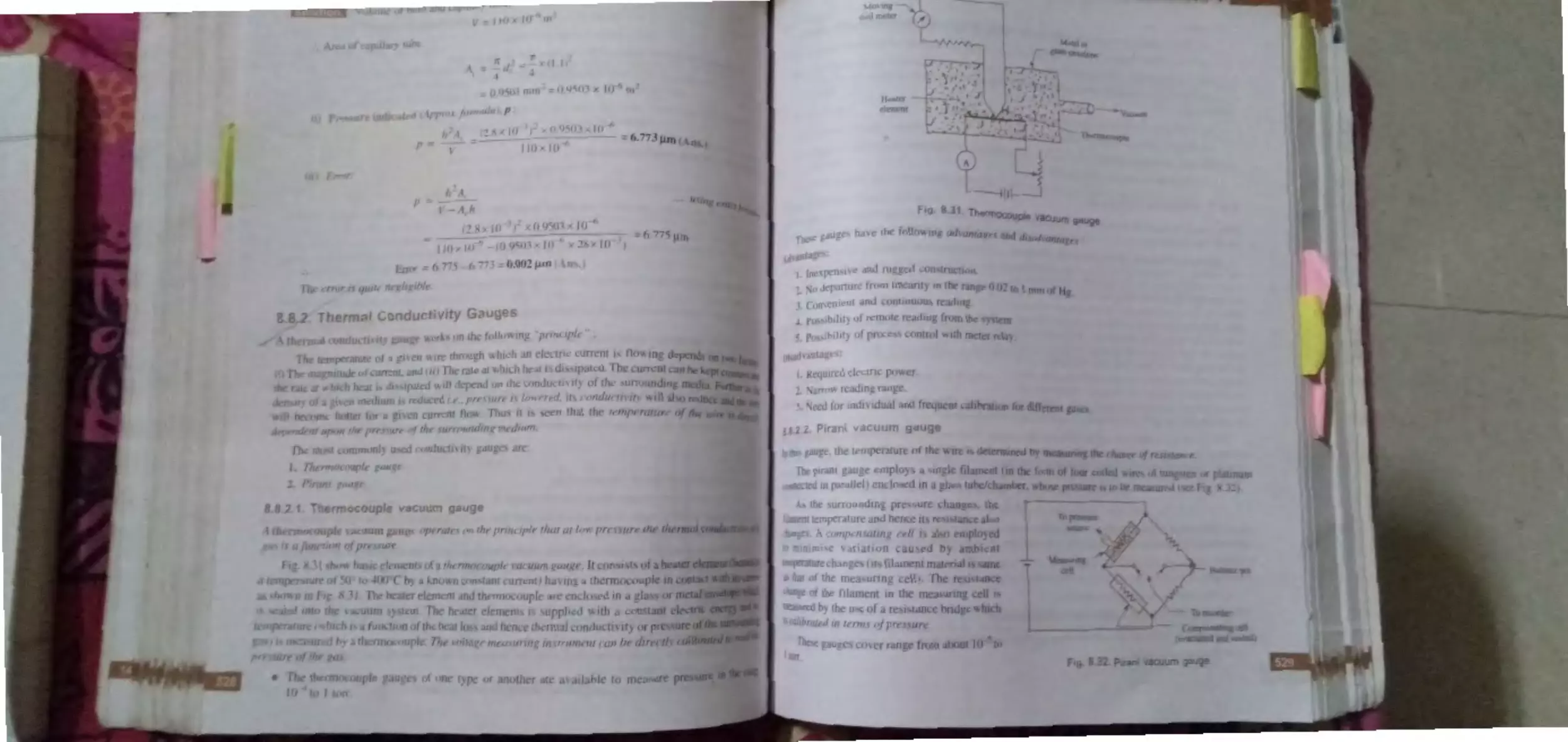

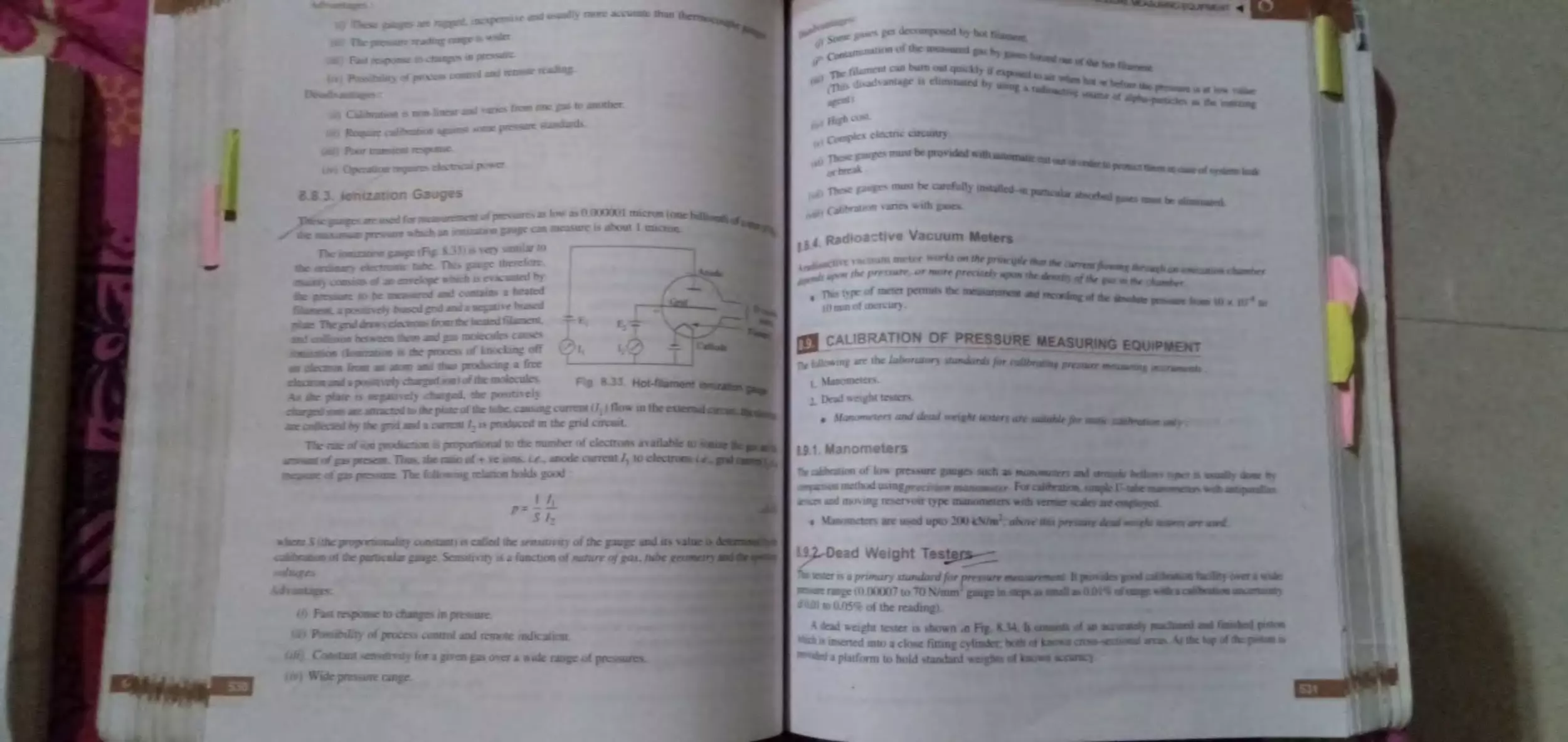

• It records daza digitally o n a computer.