Теги: weapons military affairs military equipment army soviet army

Год: 1978

Текст

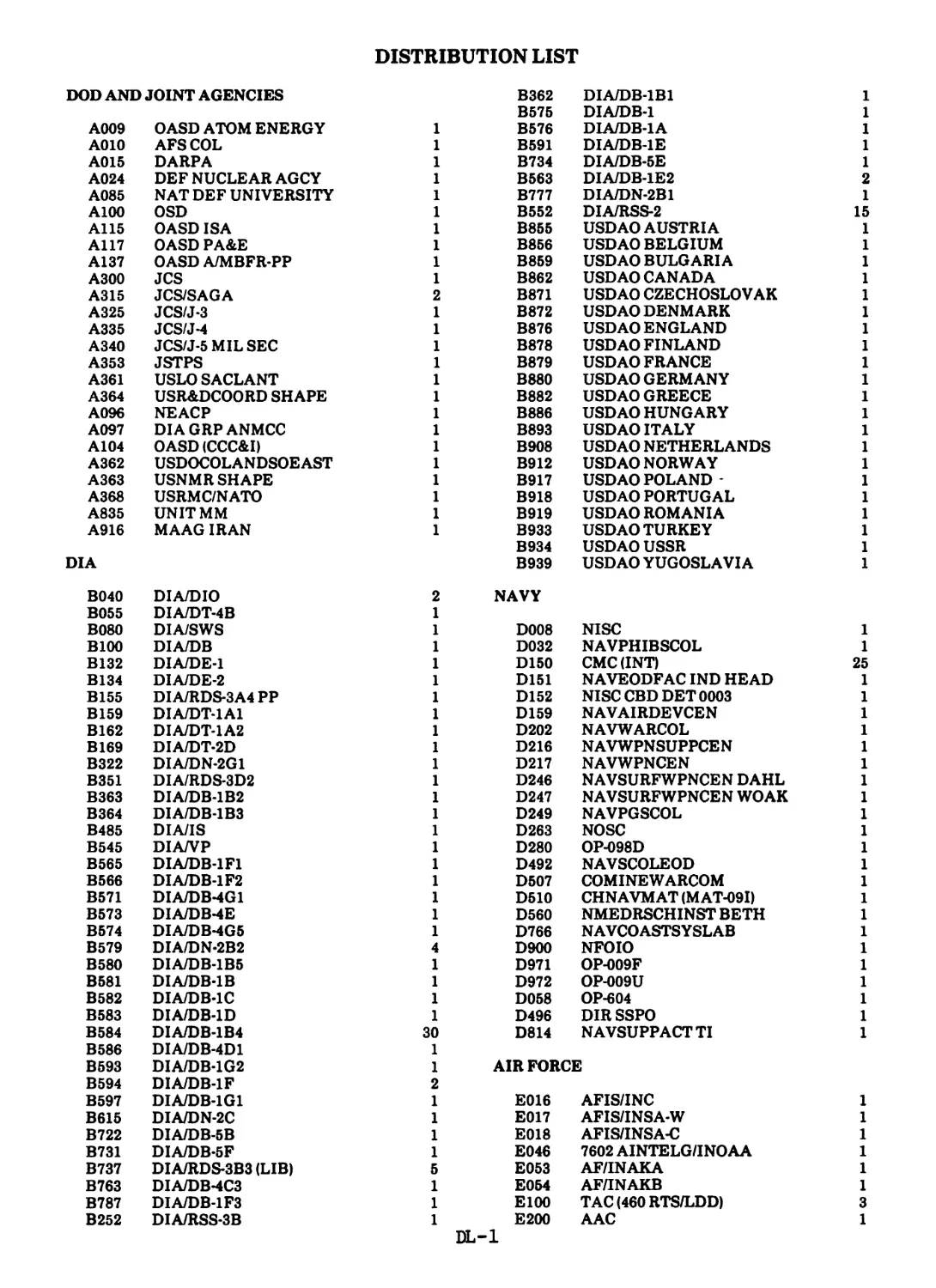

DDB-1100-197-78

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE REPORT

THE SOVIET

MOTORIZED RIFLE

BATTALION

SEPTEMBER 1978

THE SOVIET MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION

DDB-1100-197-78

Information Cutoff Date:

20 December 1977

This publication supersedes

Soviet Tactics: The Motorized Rifle Battalion,

AP-1-220-3-4-64, November 1964,

which should be destroyed.

This is a Department of Defense Intelligence Document

Prepared by the Soviet/Warsaw Pact Division,

Directorate for Intelligence Research, Defense Intelligence Agency

Author: Major Robert M. Frasche,

Tactics and Organization Section,

Ground Forces Branch

PREFACE

This study, a foilow-up to The Soviet Motorized Rifle Company

(DDI-1100-77-76), was written to familiarize the reader with the organization,

training, tactics, and equipment of the Soviet motorized rifle battalion (MRB). It

was especially written for troops, troop commanders, unit intelligence officers,

service schools, and others who require detailed knowledge of the Soviet MRB.

The study concentrates on the operations of those MRBs equipped with the

BMP (infantry combat vehicle). The organization, training, tactics, and equip-

ment of the BMP-equipped MRB are analyzed within the context of Soviet doc-

trine. Soviet tactical trends since the October I973 War are also considered. The

scope of the study is restricted to those operations (nuclear and nonnuclear) rele-

vant to northern and central Europe.

Studies which address in greater detail some of the subjects covered in this

text are as follows:

1. Soviet Offensive Doctrine: Combined Arms Operations Versus Antitank

Defenses (U), DDI-1100-138-76, July 1976.

2. Soviet Tactical Trends Since the October 1973 War (U), DDI-1100-160-77,

April 1977.

3. The Soviet Motorized Rifle Company (U), DDI-1100-77-76, October 1976.

4. Soviet Military Operations in Built-Up Areas (U), DDI-1100-155-77, July

1977.

5. Soviet and Warsaw Pact River Crossing: Doctrine and Capabilities (U)

DDI-1150-7-76, September 1976.

6. Evaluation of Soviet Night Combat Capabilities (U), DDI-1100-173-77,

February 1978.

7. Soviet Amphibious Warfare Capabilities (U), DDI-1200-74-76, May 1976.

8. Soviet Tactical Level Logistics (U), DDI-1150-0014-77, December 1977.

9. Soviet Field Artillery Tactics and Techniques (U), (DDB-1130-8-78-to be

published).

Addressees are requested to forward information which will supplement or cor-

rect this report. Questions and comments should be referred in writing to the

Defense Intelligence Agency (ATTN: DB-1B4), Washington, D.C. 20301.

SUMMARY

The Soviets stress the decisive nature of the offensive and emphasize the meeting engagement more than

any other type of offensive action. High rates of advance are anticipated from the actions of combined arms

units operating in conjunction with airborne, airmobile, and special operations forces in the enemy rear area.

Since the October 1973 War, the Soviets have placed even more emphasis on combined arms operations,

and have made numerous organizational and tactical adjustments to increase the survivability of their tank

forces. The tank remains the backbone of combined arms doctrine.

Though relatively small, the BMP-equipped MRB is highly maneuverable and possesses considerable

organic firepower, particularly in antitank weaponry. The MRB is often augmented by motorized rifle regi-

ment and/or divisional assets to form a heavily reinforced combined arms grouping to carry out a variety of

missions.

The battalion commander's age, education, and political awareness provide the theoretical basis for effec-

tive command. Frequent field training and lengthy peacetime command assignments partially offset his lack

of combat experience. Though technically well trained, the MRB commander often fails to exploit the strong

points of his men and equipment during field exercises. Moreover, his initiative is constricted within narrow

parameters by institutional and operational constraints.

Battalion-level training is highly centralized, stresses fundmentals, and results in effective battle drill.

"Moral-political" training, while boring for many, is probably effective. Training effectiveness is complicated

by the 2 year term of service.

The MRB is capable of conducting operations under special conditions, although the amount of such train-

ing varies according to geographic location and mission.

The BMP-equipped MRB normally operates as part of the regiment and is most effective when so

employed. Discrepancies between doctrine and practice have been noted in several types of MRB operations.

These discrepancies, along with constraints on battalion-level leadership, result in vulnerabilities which may

be exploited by Western commanders.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

SUMMARY................................................................................... V

CHAPTER!. INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1

CHAPTER 2. DOCTRINE, TACTICS, TRENDS.................................................... 3

Section A - Doctrine.................................................................... 3

Section В - Tactics..................................................................... 7

Section C - Tactical Trends Since The October 1973 War..................................12

CHAPTER 3. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE DIVISION AND MOTORIZED RIFLE REGIMENT....................13

CHAPTER 4. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION................................................25

Section A - Operational Principles and Missions.........................................25

Section В - Organization, Responsibilities, and Equipment...............................26

Section C - Command and Control.........................................................33

Section D - Battalion Rear Services.....................................................36

CHAPTERS. BATTALION LEVEL LEADERSHIP......................................................49

Section A - Introduction................................................................49

Section В - The Historical Perspective .................................................49

Section C - The Present ................................................................52

CHAPTERS. BATTALION TRAINING AND SUBUNIT TACTICS..........................................57

Section A - Training Philosophy and Objectives .........................................57

Section В - Training Schedules..........................................................57

Section C - Company and Section Training and Tactics ...................................59

Section D - Battalion Tactical Training ................................................69

Section E - Evaluation of Battalion Training ...........................................70

CHAPTER 7. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION IN COMBAT......................................71

Section A - Offensive Operations .......................................................71

Section В - Defensive Operations........................................................90

CHAPTER 8. THE MRB OPERATING UNDER SPECIAL CONDITIONS..................................103

Section A - General....................................................................103

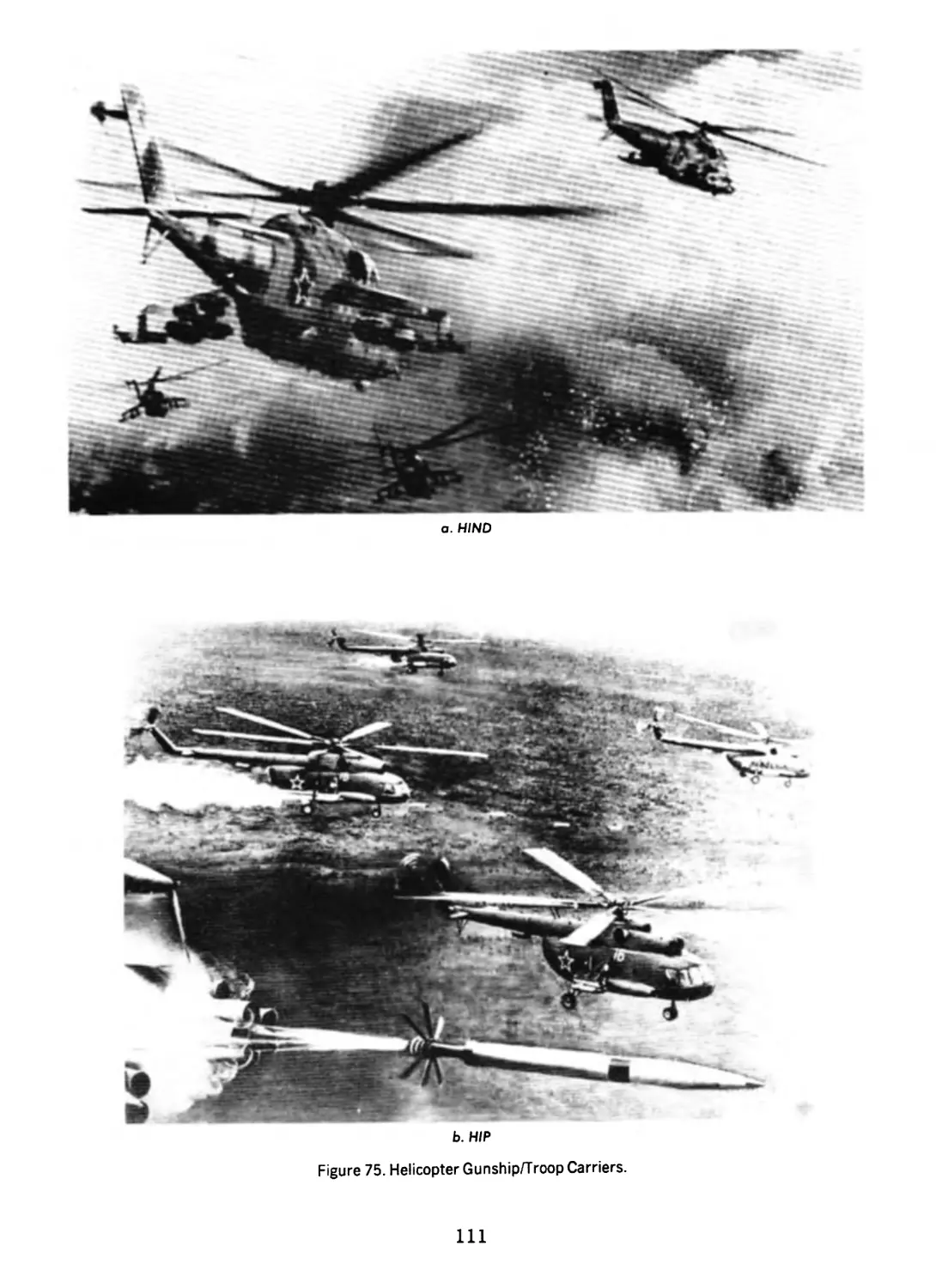

Section В - Combat in Built-up Areas...................................................103

Section C - Heliborne Operations.......................................................109

Section D - Water Barrier Operations ..................................................116

Section E - Night Combat...............................................................124

Section F - Seaborne Assault and Defense of a Coastline................................130

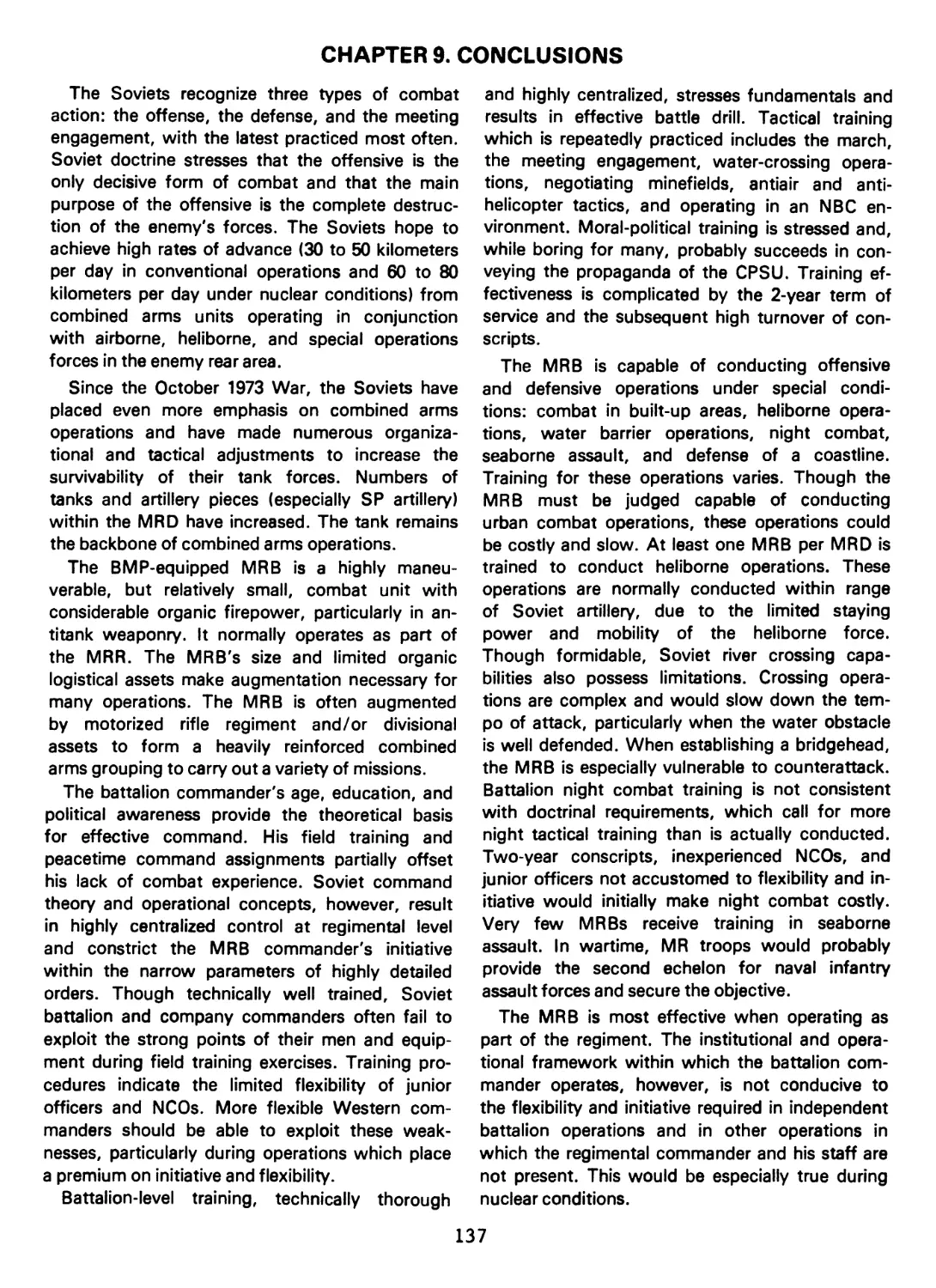

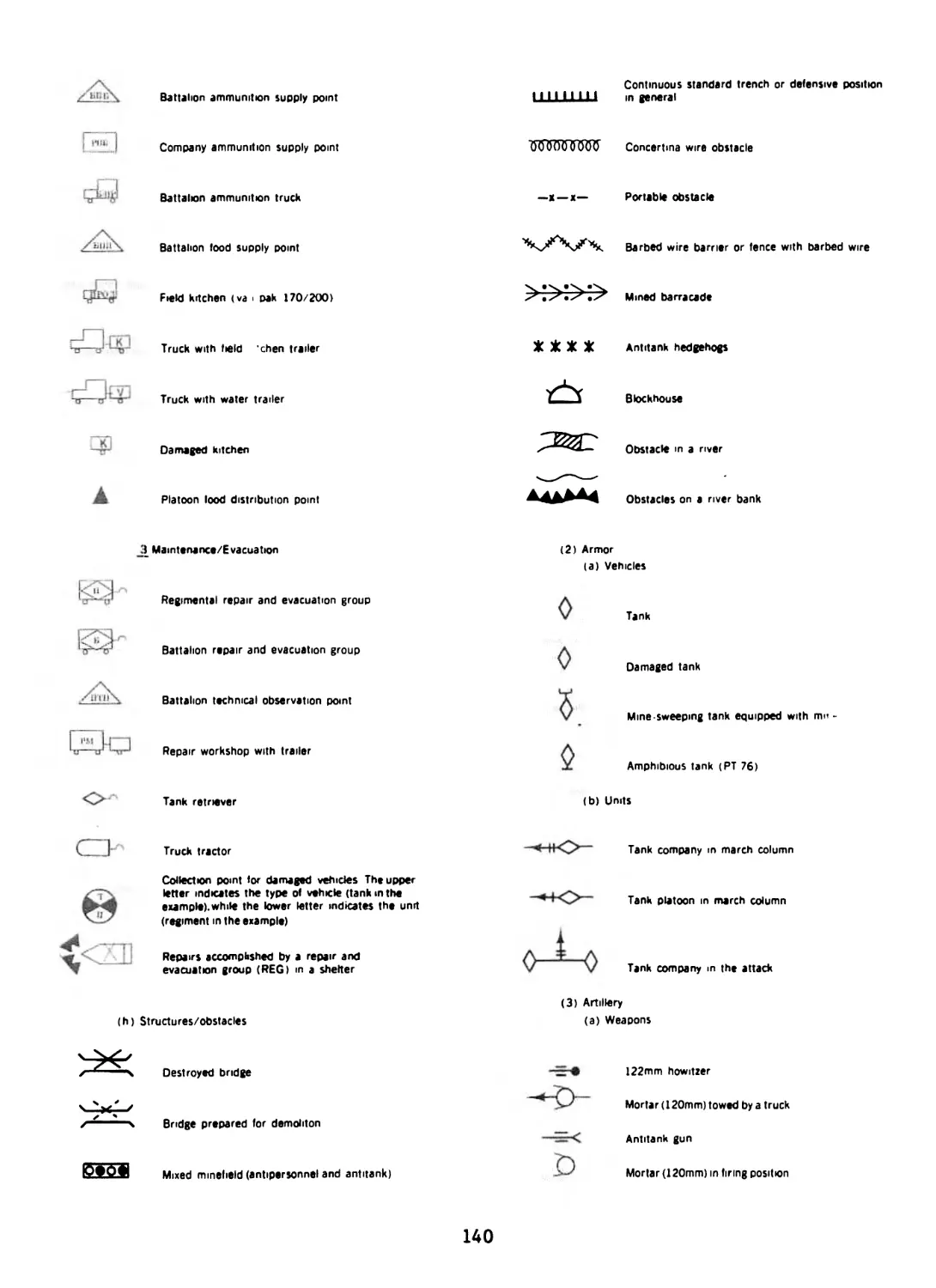

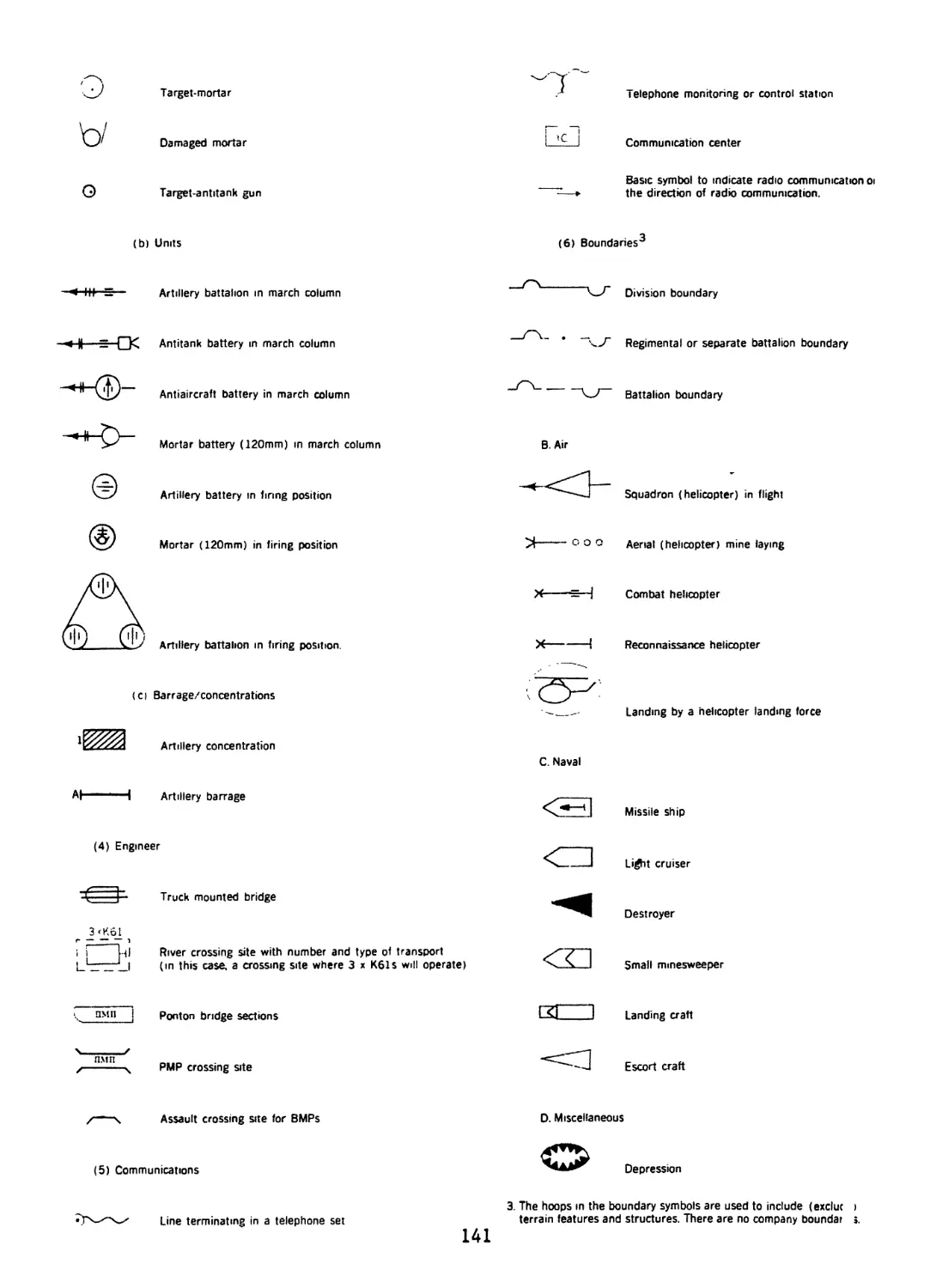

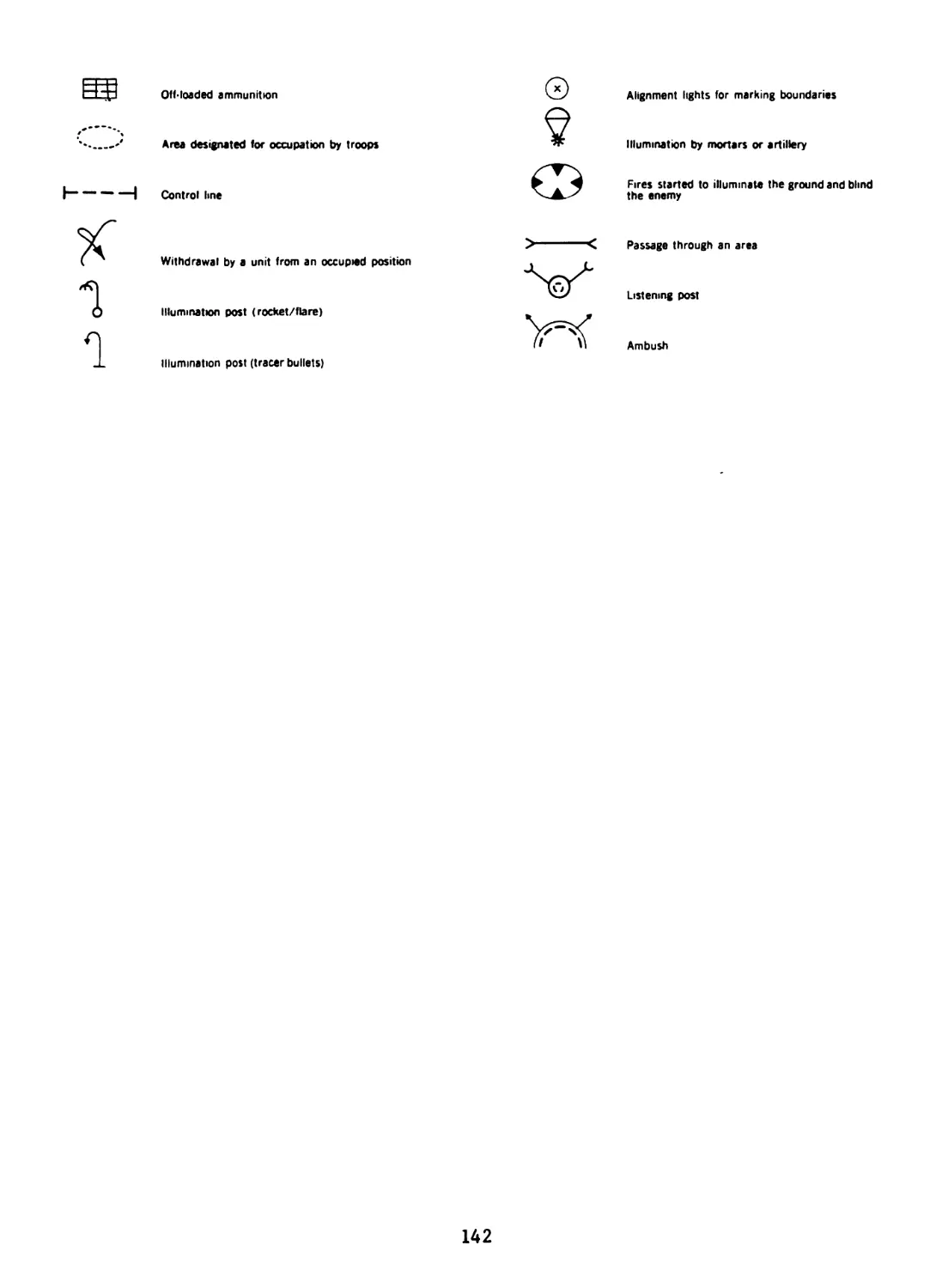

CHAPTER 9. CONCLUSIONS.................................................................I37

APPENDIX

Soviet Symbols...........................................................................139

vii

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Page

1. Soviet Offensive Doctrine Is Based on Combined Arms Combat ................................3

2. Airborne and Heliborne Troops Are Selectively Used To Maintain Offensive Momentum.........4

a. Airborne Drop in the Enemy Rear Area ..................................................4

b. Heliborne Forces Rush To Establish a Bridgehead........................................4

3. Basic Forms of Maneuver....................................................................5

a. Frontal Attack.........................................................................5

b. Shallow Envelopment (Single) ..........................................................5

c. Deep Envelopment (Double)..............................................................5

4. The Meeting Engagement.....................................................................6

5. Battalion Antitank Reserves Respond Directly to the Battalion Commander....................8

a. Antitank Reserves in a BTR-Equipped Unit ..............................................8

b. A BMP-Equipped Motorized Rifle Battalion Antitank Reserve..............................9

6. Traffic Regulators Aid Commanders in Controlling Their Units...............................9

7. The Regimental Chief of Artillery (on the right) Coordinates Regimental Artillery During

Phase One Fire...............................................................................10

8. High Performance Aircraft in Support of the Main Attack .................................11

9. The Motorized Rifle Division ............................................................13

10. The Motorized Rifle Division's Principal Weapons.........................................14

a. 76mm Divisional Gun, ZIS-3 ...........................................................14

b. 100mm AT Gun, M-55/T-12 ..............................................................14

c. 122mm Howitzer, M-1938/D-30...........................................................14

d. 122mm Rocket Launcher ВM-21 ..........................................................15

e. 152mm Howitzer, D-1...................................................................15

f. FROG TEL, FROG-7 .....................................................................15

g. GAINFUL TEL, SA-6.....................................................................16

11. The Motorized Rifle Division's Principal Equipment ......................................16

a. Truck, Mine Detector, Dim.............................................................16

b. Tracked Ferry, GSP....................................................................16

c. Pontoon PMP on KRAZ ..................................................................16

d. Tracked Amphibian, K-61 ..............................................................17

e. Mine Clearer BTR-50PK, M-1972.........................................................17

f. Minelayer, SP, Armored................................................................17

g. Truck, Decon, TMS-65..................................................................18

12. The Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped)..............................................18

13. Principal Weapons in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped).........................19

a. Medium Tank, T-62/64/72...............................................................19

b. 122mm SP Howitzer.....................................................................20

c. 23mm SP AA Gun, ZSU-23-4 .............................................................20

d. SAM (SA-9) GASKIN.....................................................................21

e. ATGM Launcher Vehicle AT-3 ......,....................................................21

*4 Principal Equipment in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped)........................21

a. Truck, Decon, ARS-14..................................................................21

b. Truck, Decon, DDA-66..................................................................21

c. Bridge, Tank Launched, MTU............................................................21

d. Bridge, Truck Launched, TMM...........................................................22

e. Ditching Machine

(1) MDK-2 ...........................................................................22

(2) MDK-2 in Operation...............................................................22

f. Dozer, BAT/BAT-M/PK-T.................................................................23

g. Mine Clearing Plow, KMT-4 ...........................................................23

h. Mine Layer, Towed, PMR-3 ............................................................23

i. Mine Roller, KMT-5...................................................................23

ix

15. The Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped) .............................................26

16. Principal Weapons and Equipment of The Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped) ..........

a. 120mm Mortar ...........................................................................

b. BMP.....................................................................................

c. Truck, UAZ-69 ..........................................................................

d. Truck, GAZ-66 ..........................................................................

e. Truck, ZIL130...........................................................................

f. Truck, Van, ZIL (Maintenance)...........................................................

g. Truck, POL (4,000 or 5,200 Liters)......................................................

h. Truck, Field Kitchen, Van PAK-200 ......................................................

i. Ambulance, UAZ-450 .....................................................................

j. Trailer-Mounted Field Kitchen, KP-125...................................................

17. Battalion Headquarters ....................................................................

18. The Motorized Rifle Company (BMP-Equipped)................................................

19. The Mortar Battery .......................................................................

20. The Communications Platoon ...............................................................

21. Representative Communications Net in a Motorized Rifle Battalion .........................

22. The Use of Line Communications by a Motorized Rifle Battalion in the Defense..............

23. Motorized Rifle Battalion Rear Service Elements in an Assembly Area ......................

24. Motorized Rifle Battalion Rear Service Support Elements During the March..................

25. Rear Service Support During the Attack ...................................................

26. Rear Service Support in the Defense.......................................................

27. The Supply Platoon........................................................................

28. Ammunition Resupply to the Companies in the Defense ......................................

29. Refueling the Motorized Rifle Battalion's Combat Elements During the March................

30. The Supply Platoon Delivering Food to Attacking Companies.................................

31. Division Bakery Personnel ................................................................

32. The Medical Aid Station ..................................................................

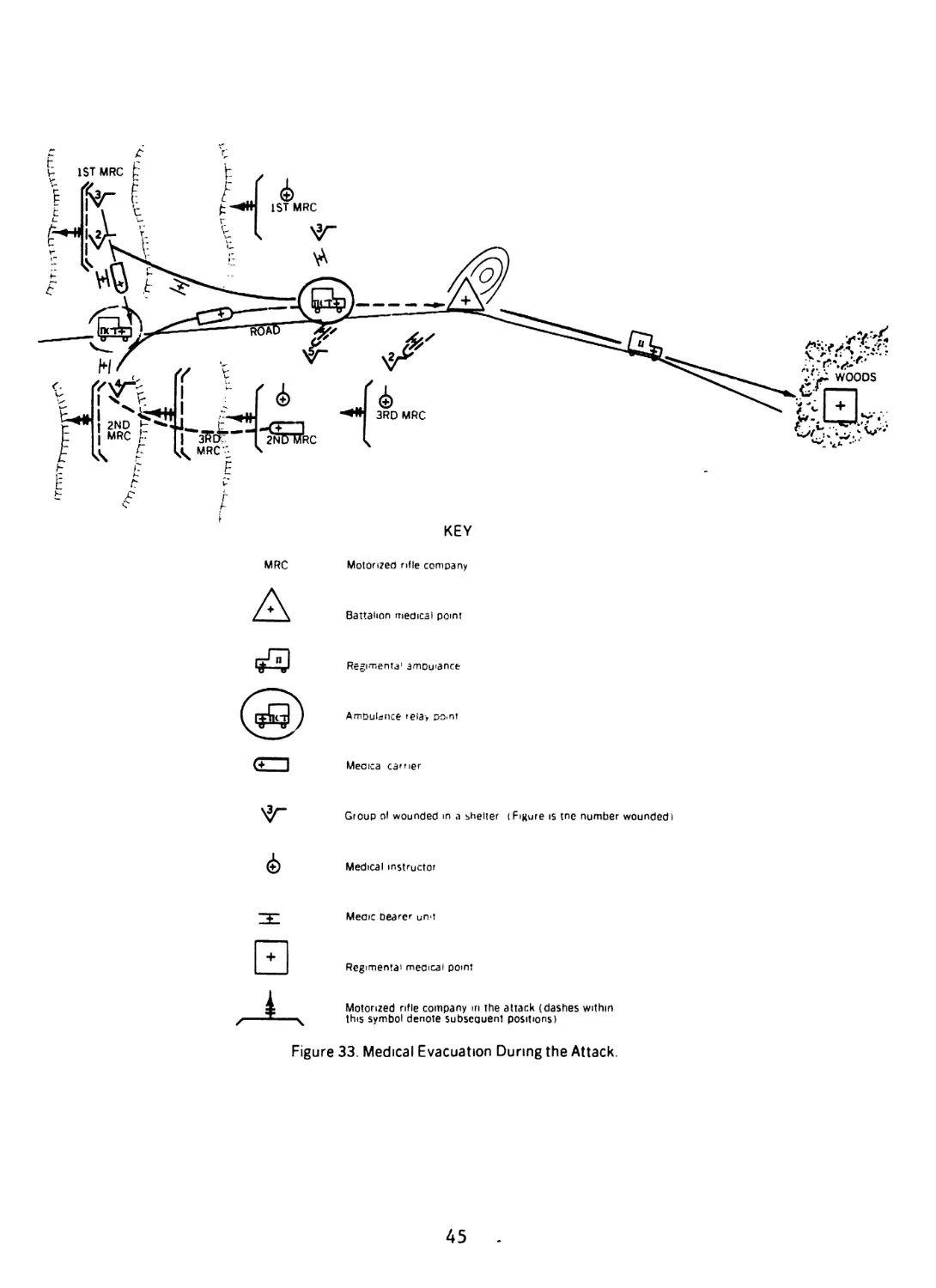

33. Medical Evacuation During an Attack.......................................................

34. The Repair Workshop ......................................................................

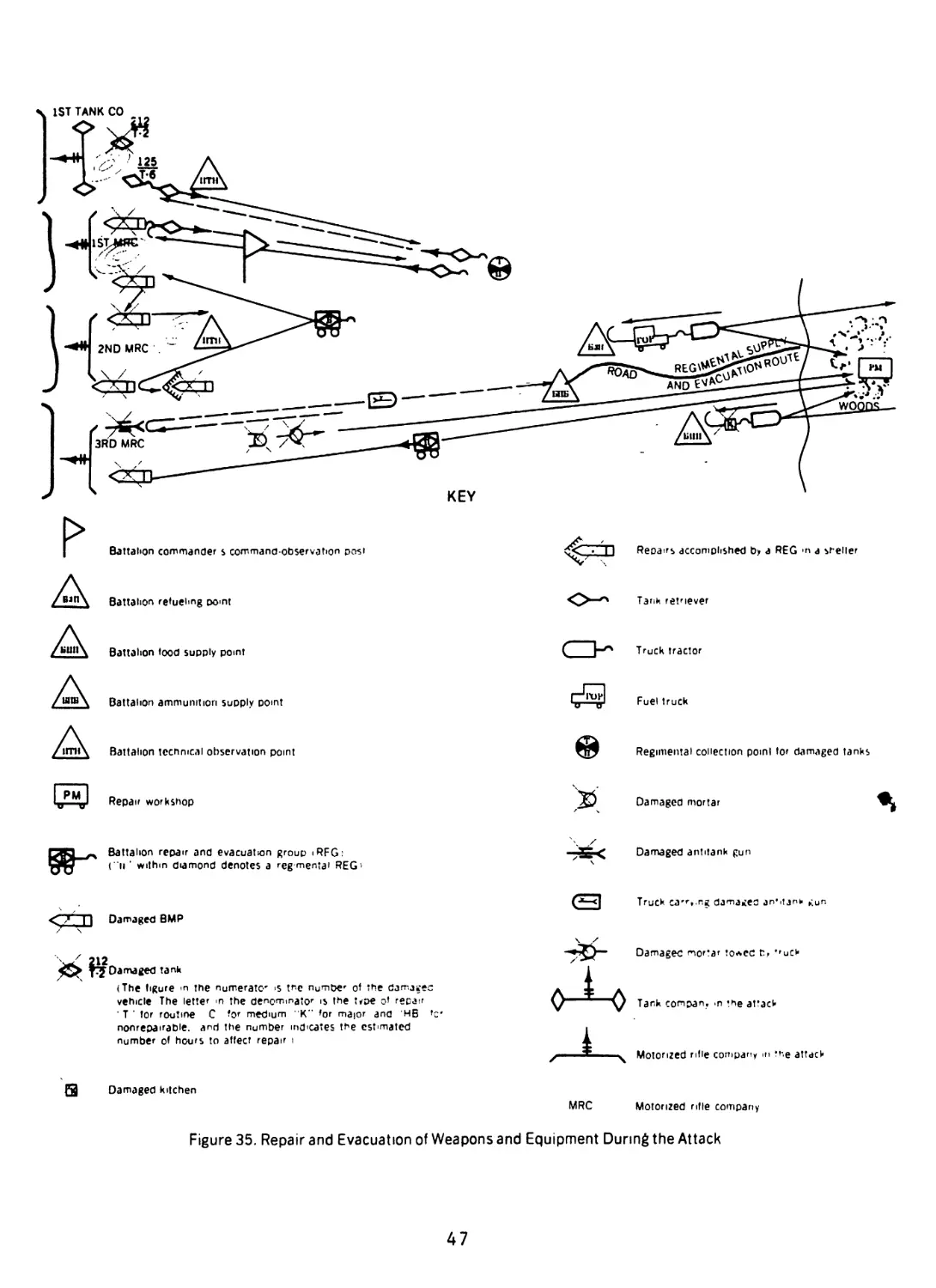

35. Repair and Evacuation of Weapons and Equipment During an Attack ..........................

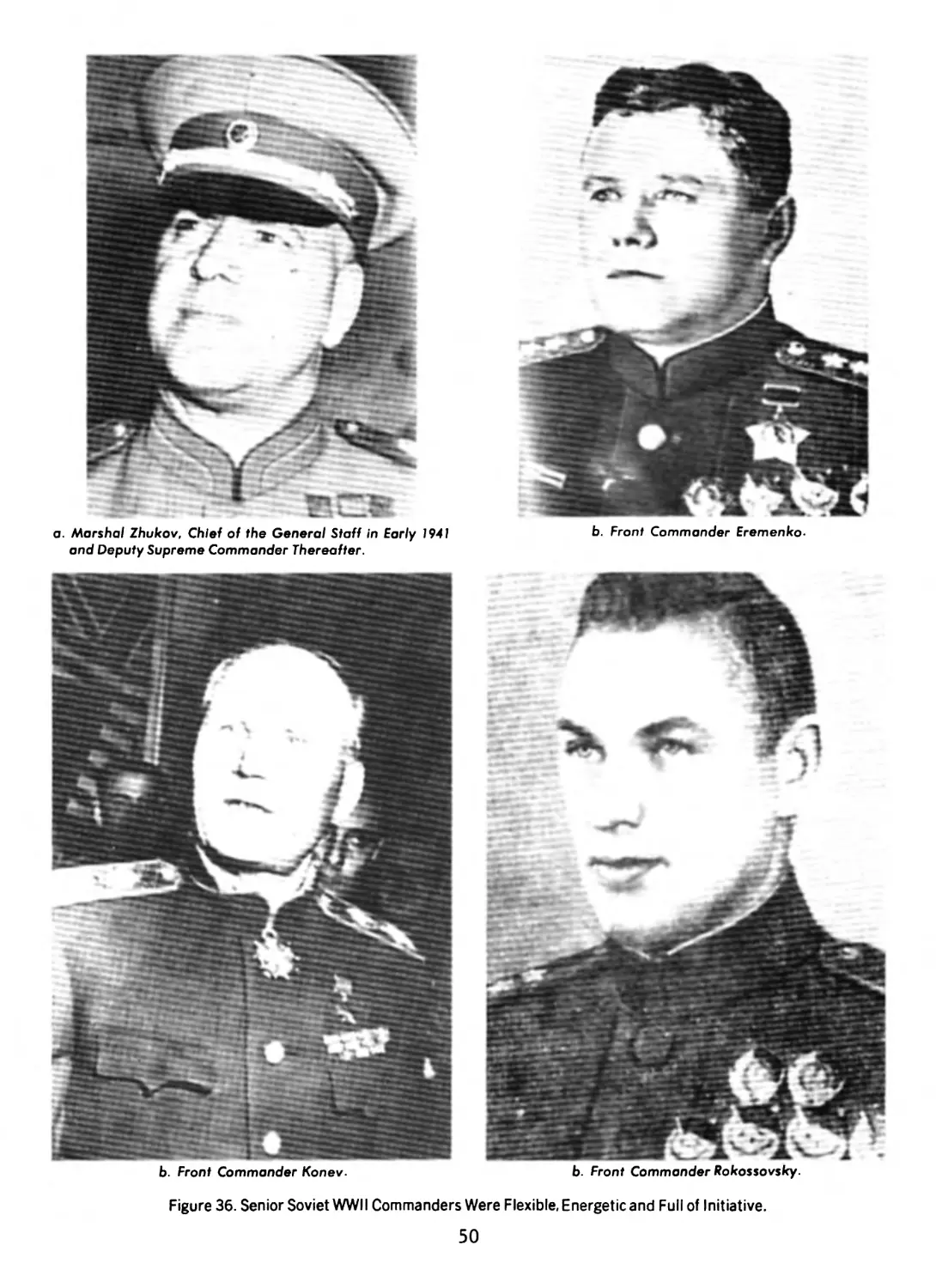

36. Senior Soviet WWII Commanders Were Flexible, Energetic and Full of Initiative ............

a. Marshal Zhukov, Chief of the General Staff in Early 1941 and Deputy Supreme Commander

Thereafter.................................................................................

b. Front Commanders Eremenko, Konev, Rokossovsky, and Timoshenko...........................

37. Until October 1941, The Unit Political Officer Had To Countersign The Commander's Orders..

38. Battalion Commanders Are Young Men with Considerable Peacetime Command Experience.........

39. The Regimental Commander and His Staff Exercise Tight Control Over

Subordinate Units..............................................................................

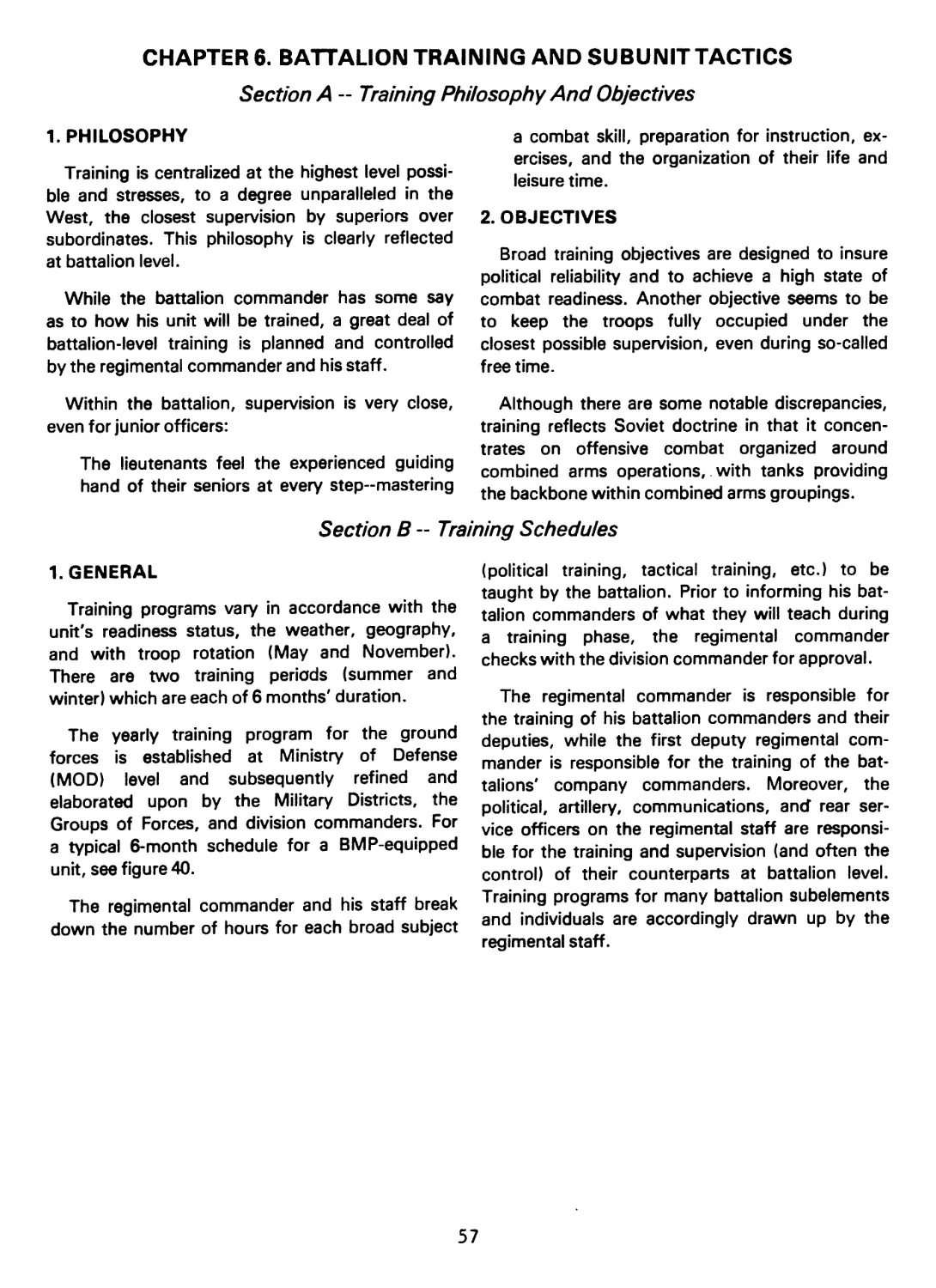

40. A Representative Six-Month Training Schedule for a BMP-Equipped Unit......................

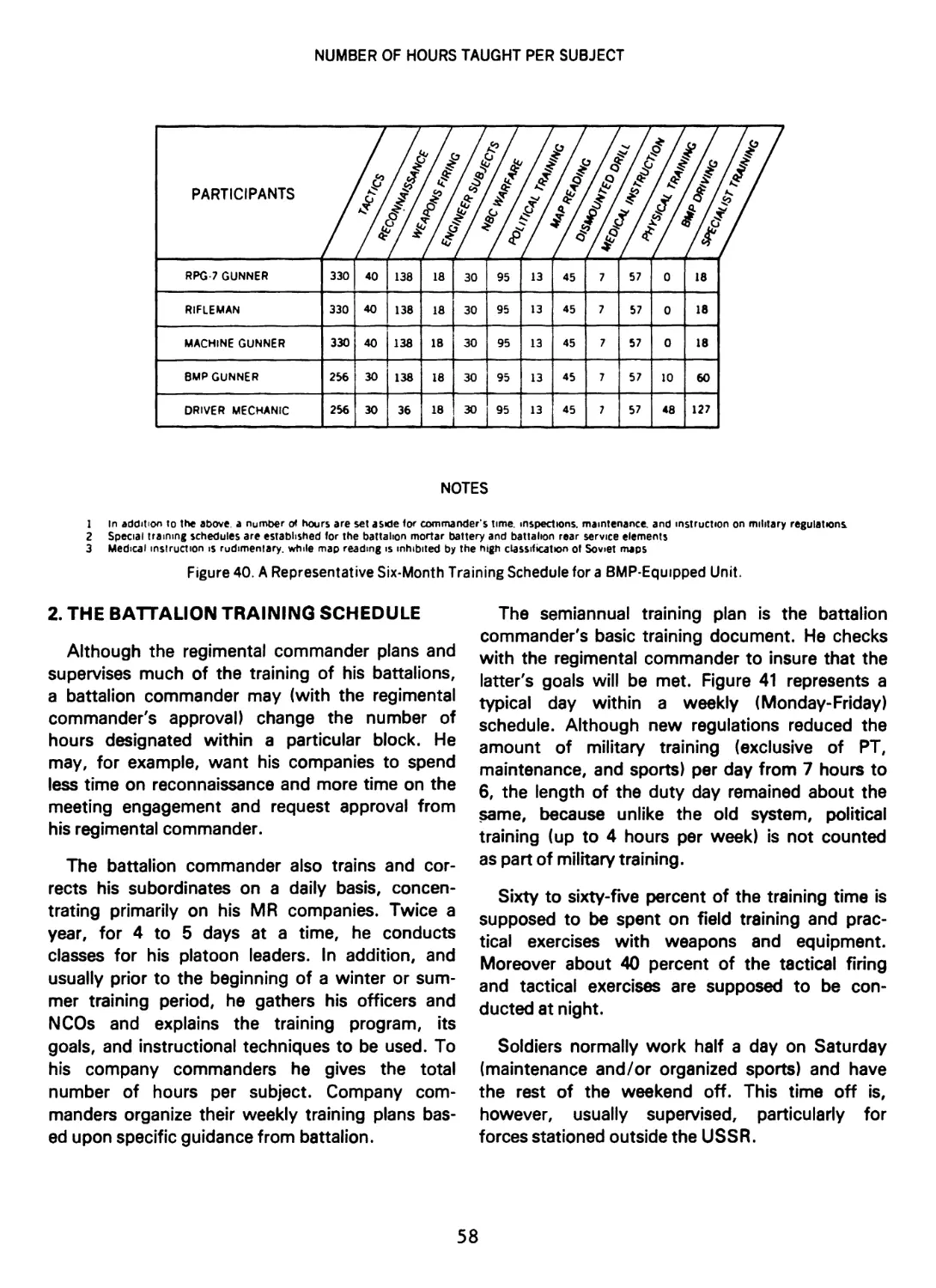

41. A Typical Week-Day Training Schedule......................................................

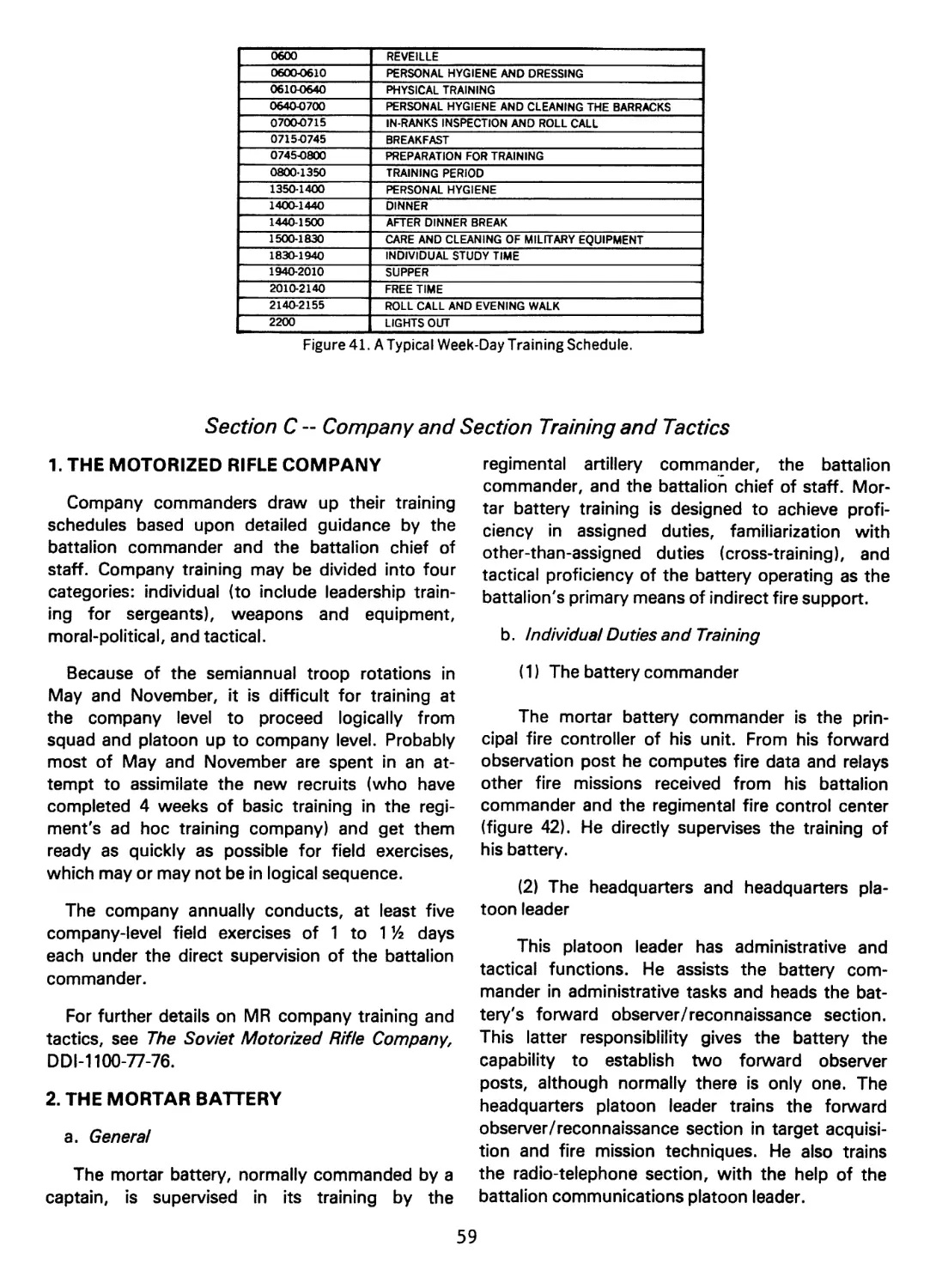

42. The Mortar Battery Commander at His Forward Observation Post..............................

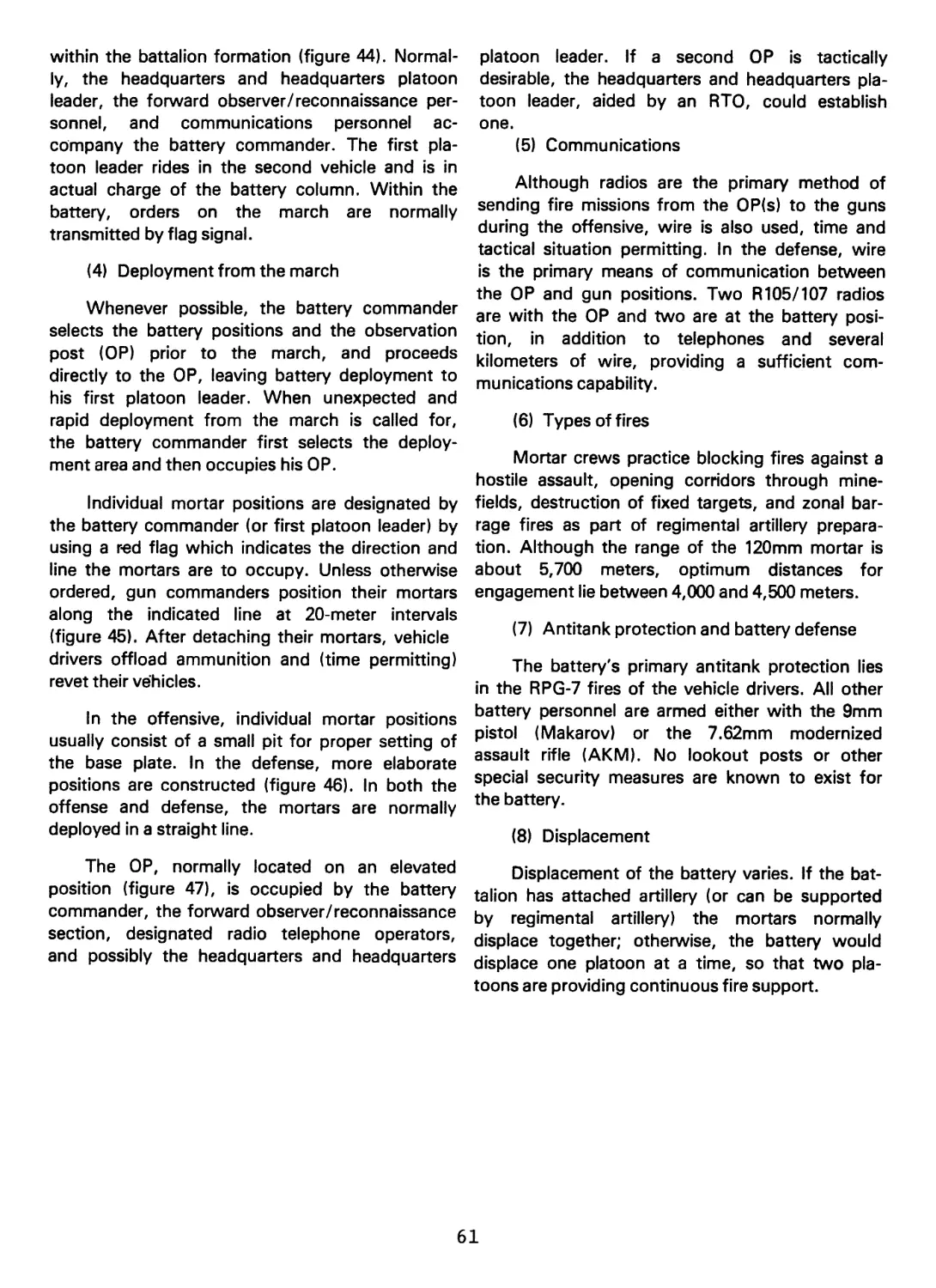

43. Flag Signals Used by the Mortar Battery ..................................................

44. The Mortar Battery During the March ......................................................

a. As Part of the Battalion Formation .....................................................

b. Battery March Order.....................................................................

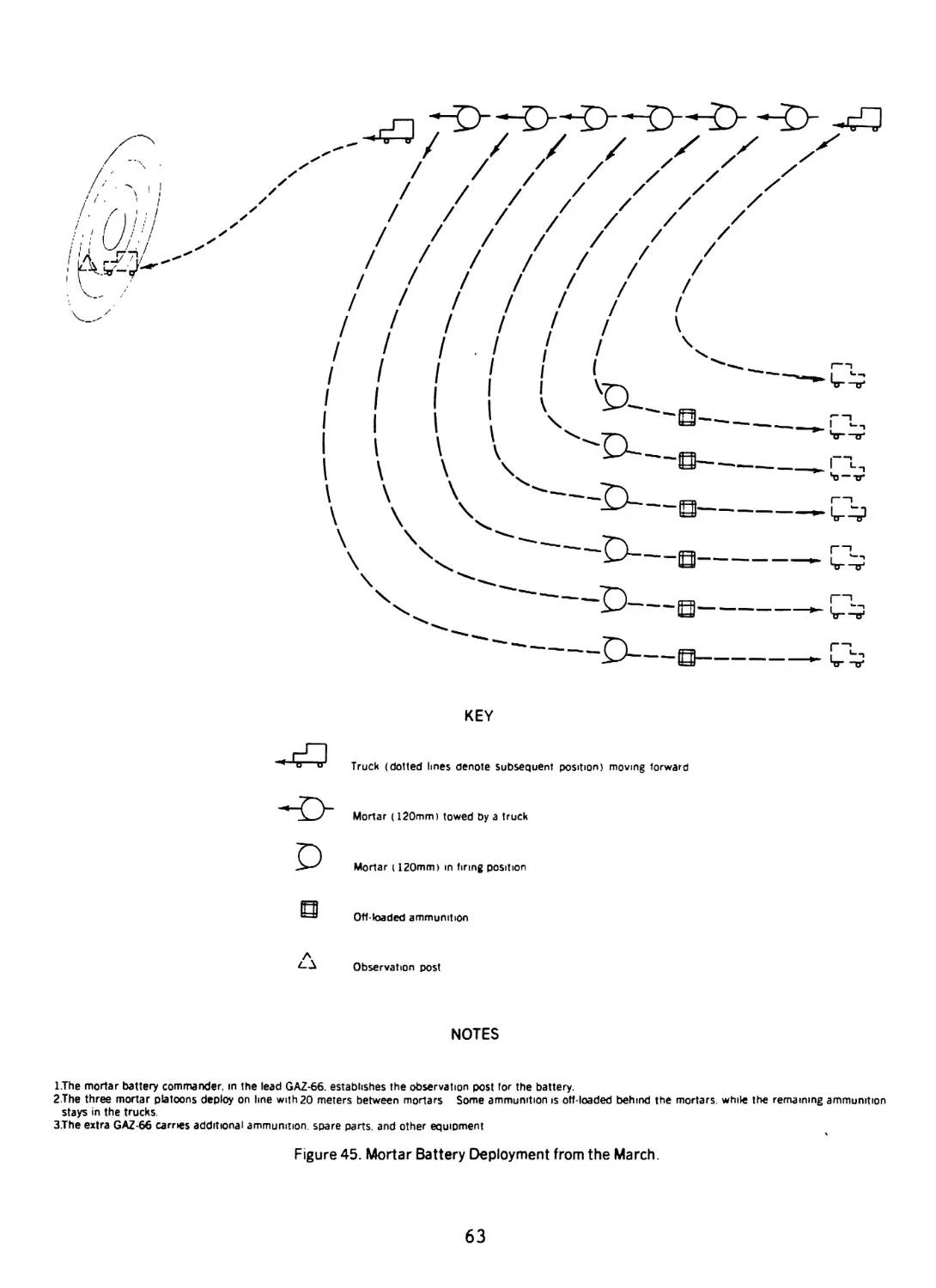

45. Mortar Battery Deployment from the March..................................................

33358 8 8^3 S 3 3 8 8 S S 3 3

x

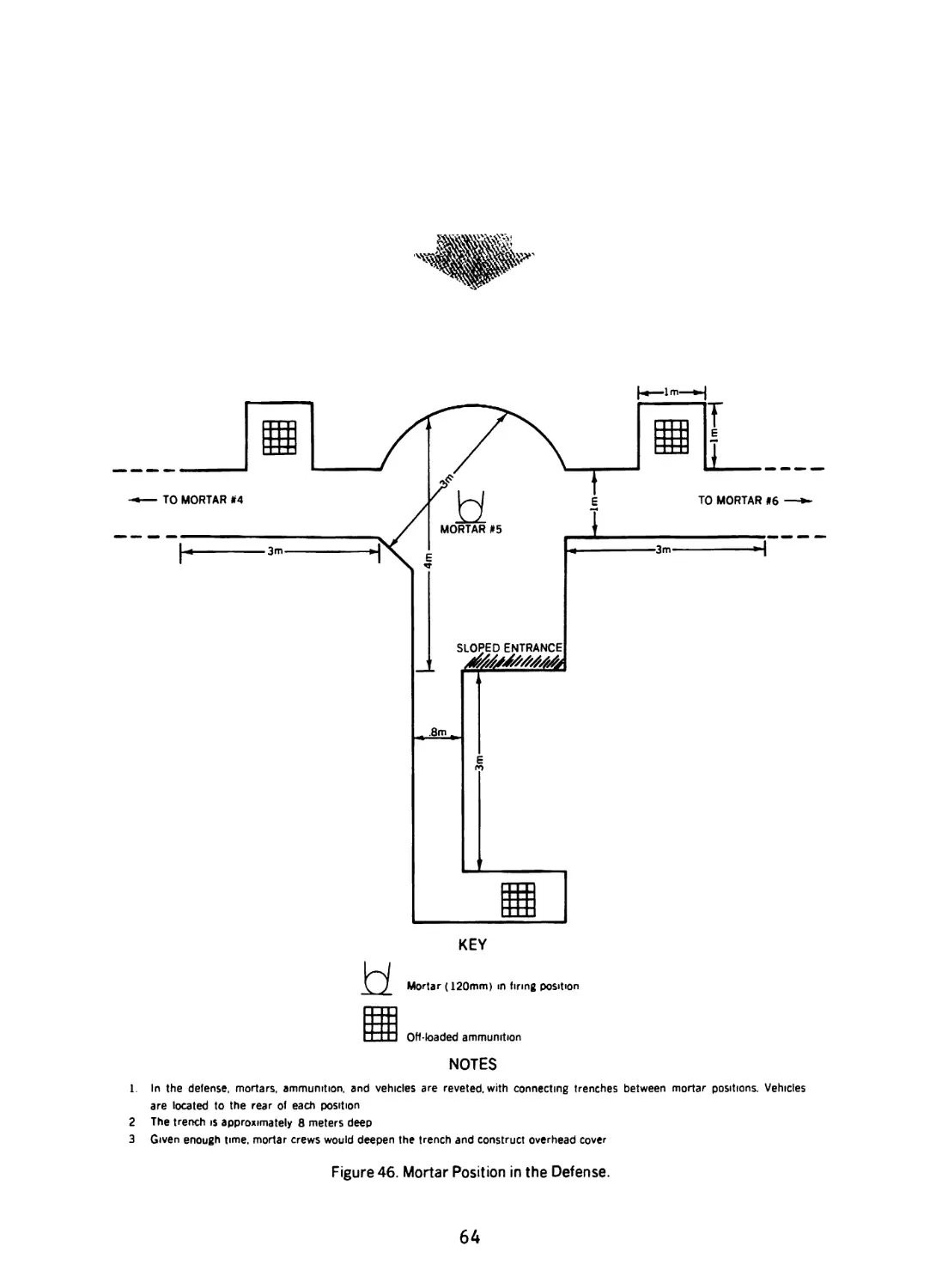

46. Mortar Position in the Defense.............................................................64

47. Operations of the Mortar Battery's Forward Observation Post................................65

48. Moral-Political Training in a Combined Arms Unit Prior to an Exercise .....................68

49. Combined Arms Combat.......................................................................69

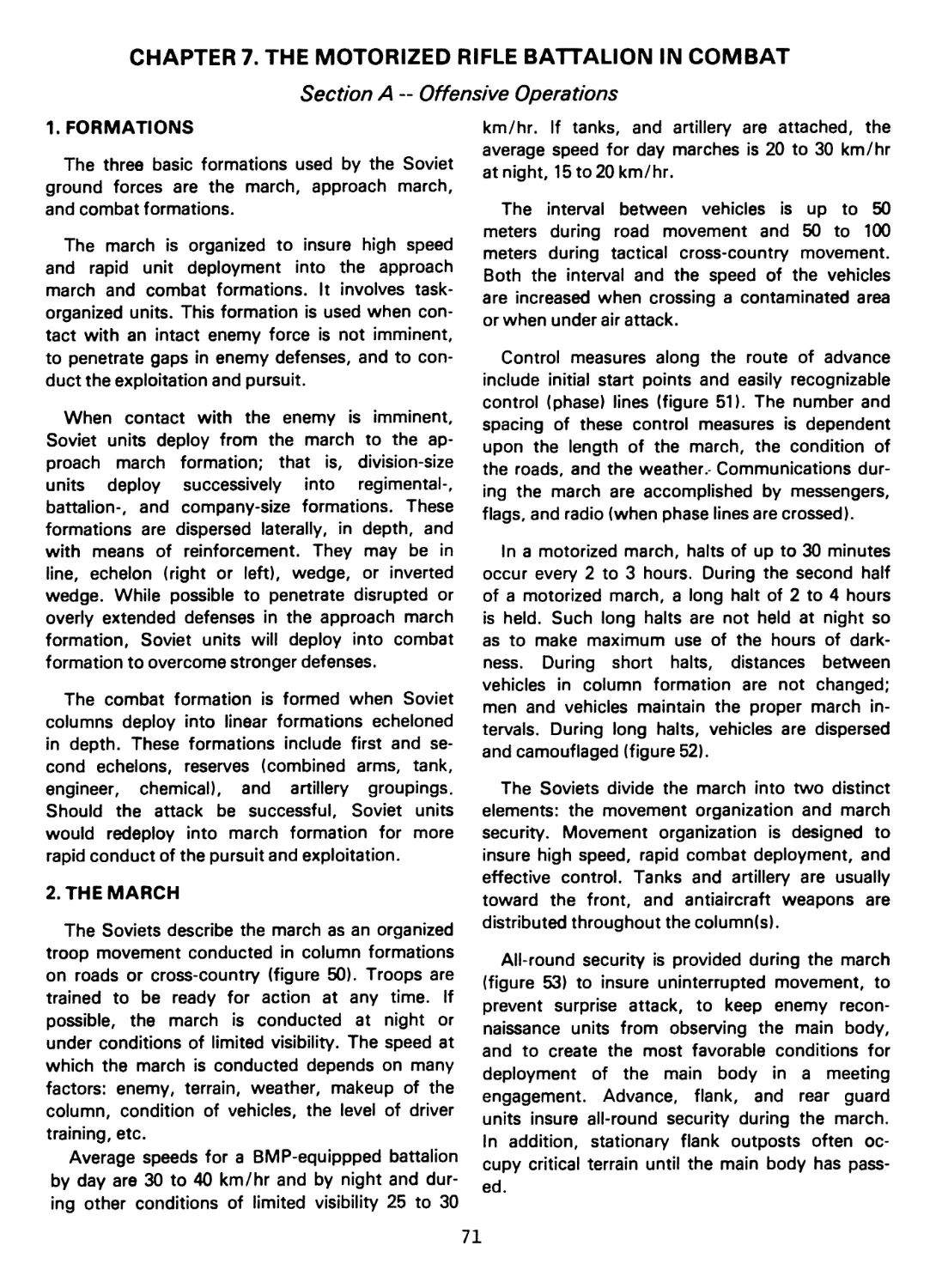

50. Tactical March Order of a Motorized Rifle Battalion........................................72

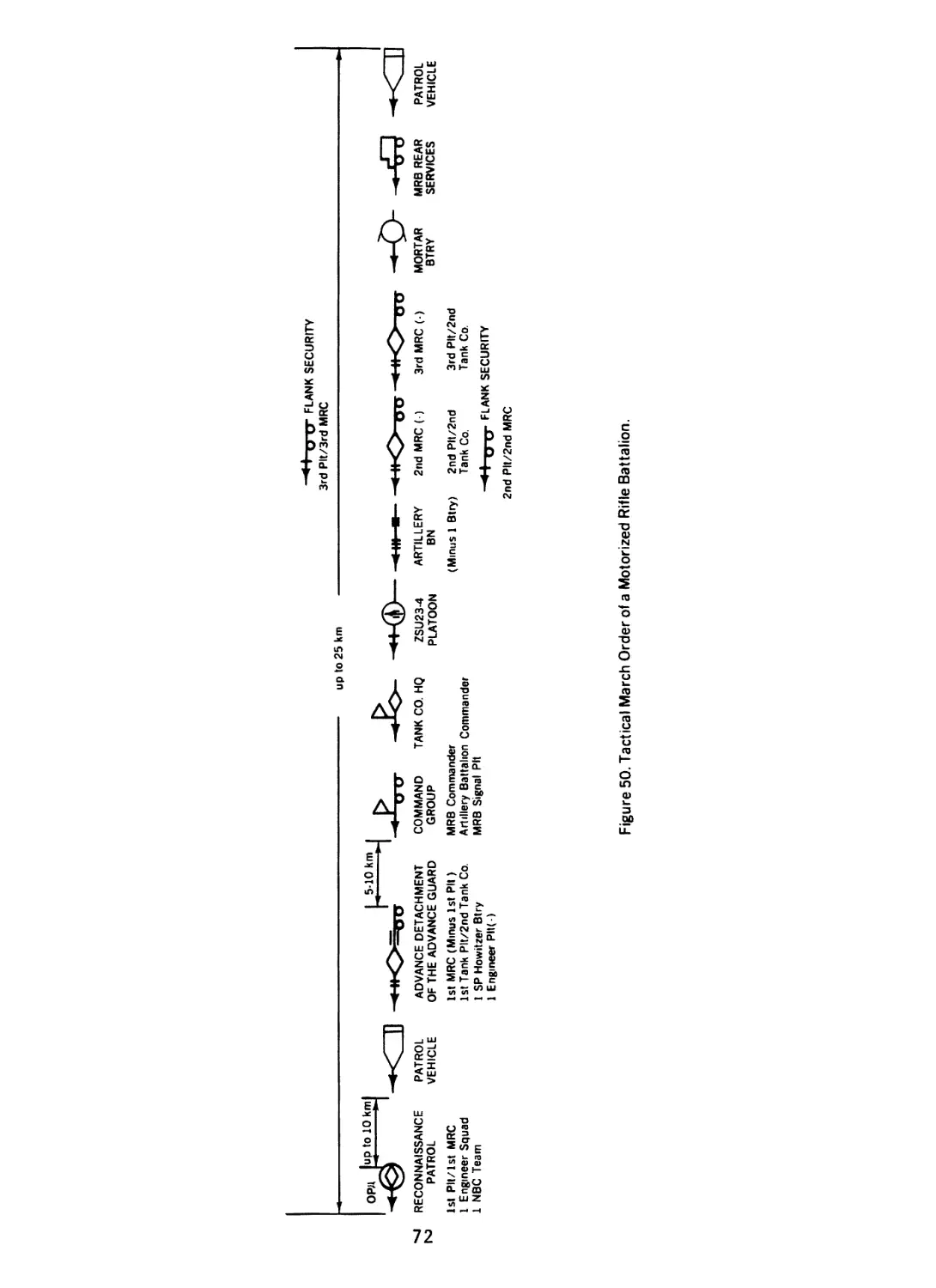

51. Control Measures During the March..........................................................73

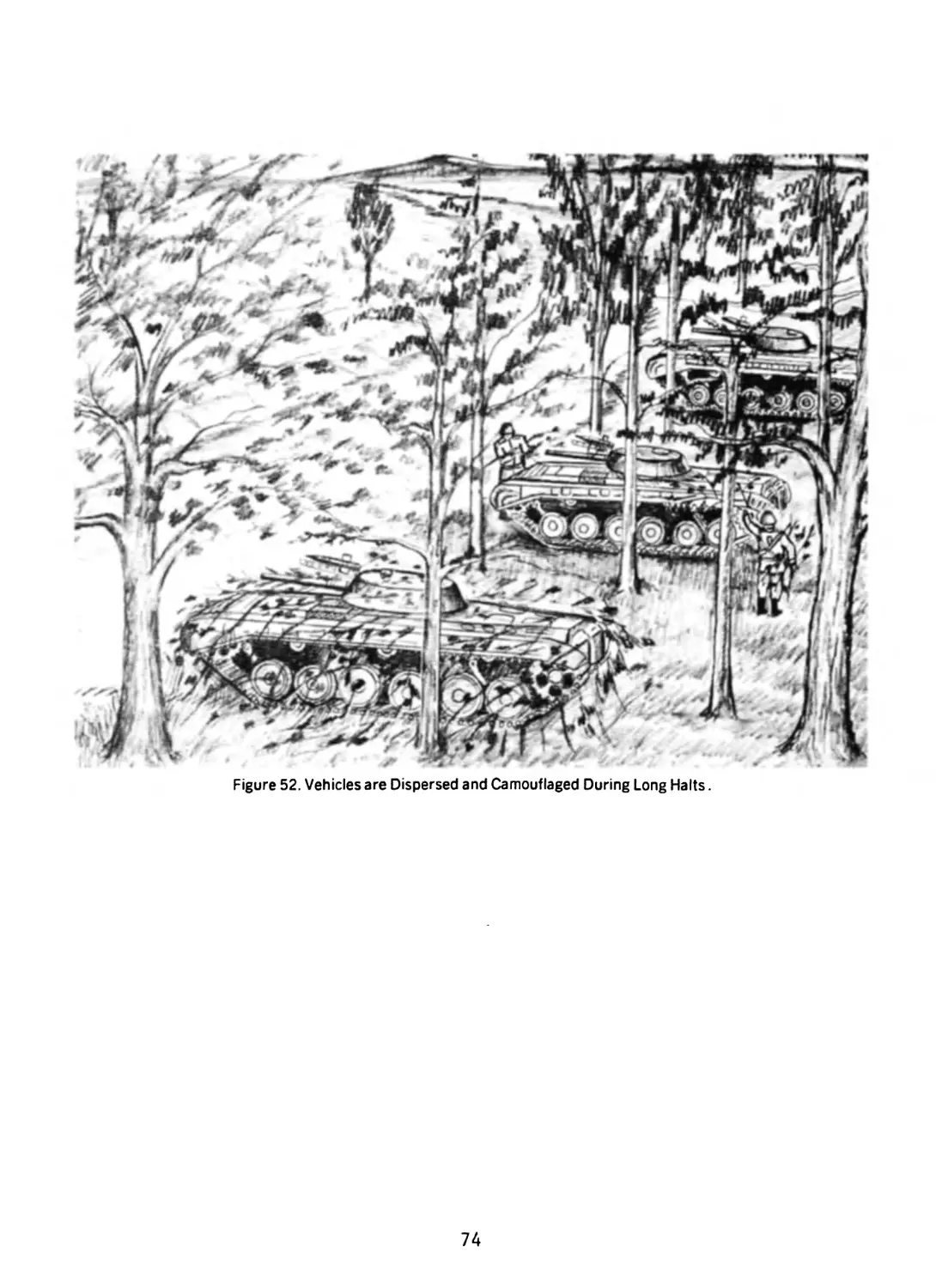

52. Vehicles are Dispersed and Camouflaged During Long Halts ..................................74

53. Security During the March..................................................................75

54. SA-7 Gunners Are The Motorized Rifle Battalion Commander's Primary Means of Air Defense....78

55. NBC Reconnaissance Is Conducted by Motorized Rifle Battalion Assets and/or by

BRDM-Equipped Specialists from Regiment ........................................................79

56. Chemical Personnel Marking a Contaminated Area ............................................79

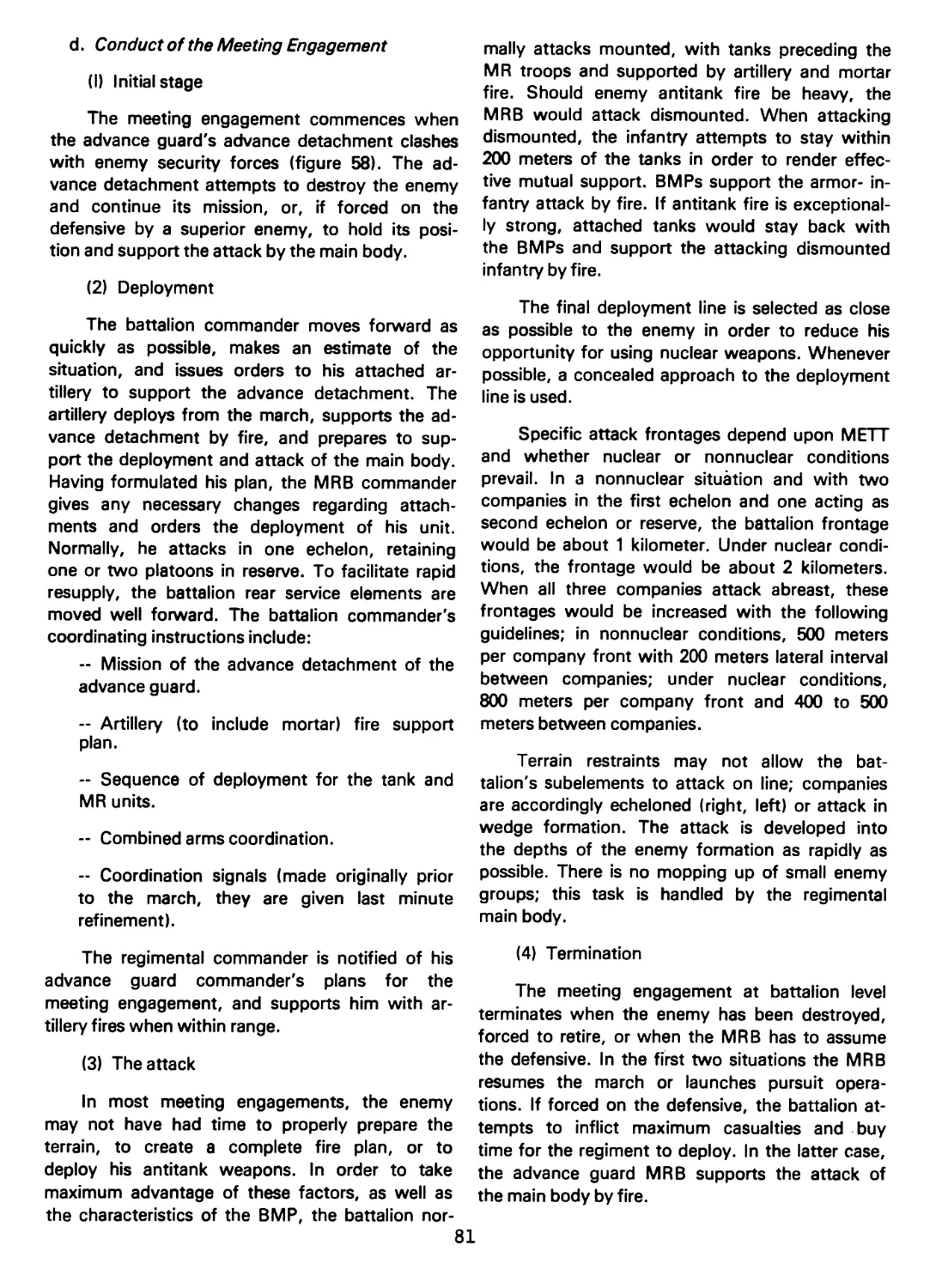

57. Conditions Leading to a Meeting Engagement.................................................80

58. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Conducting a Meeting Engagement.....................82

59. Soviet Figures for NATO Defensive Positions................................................83

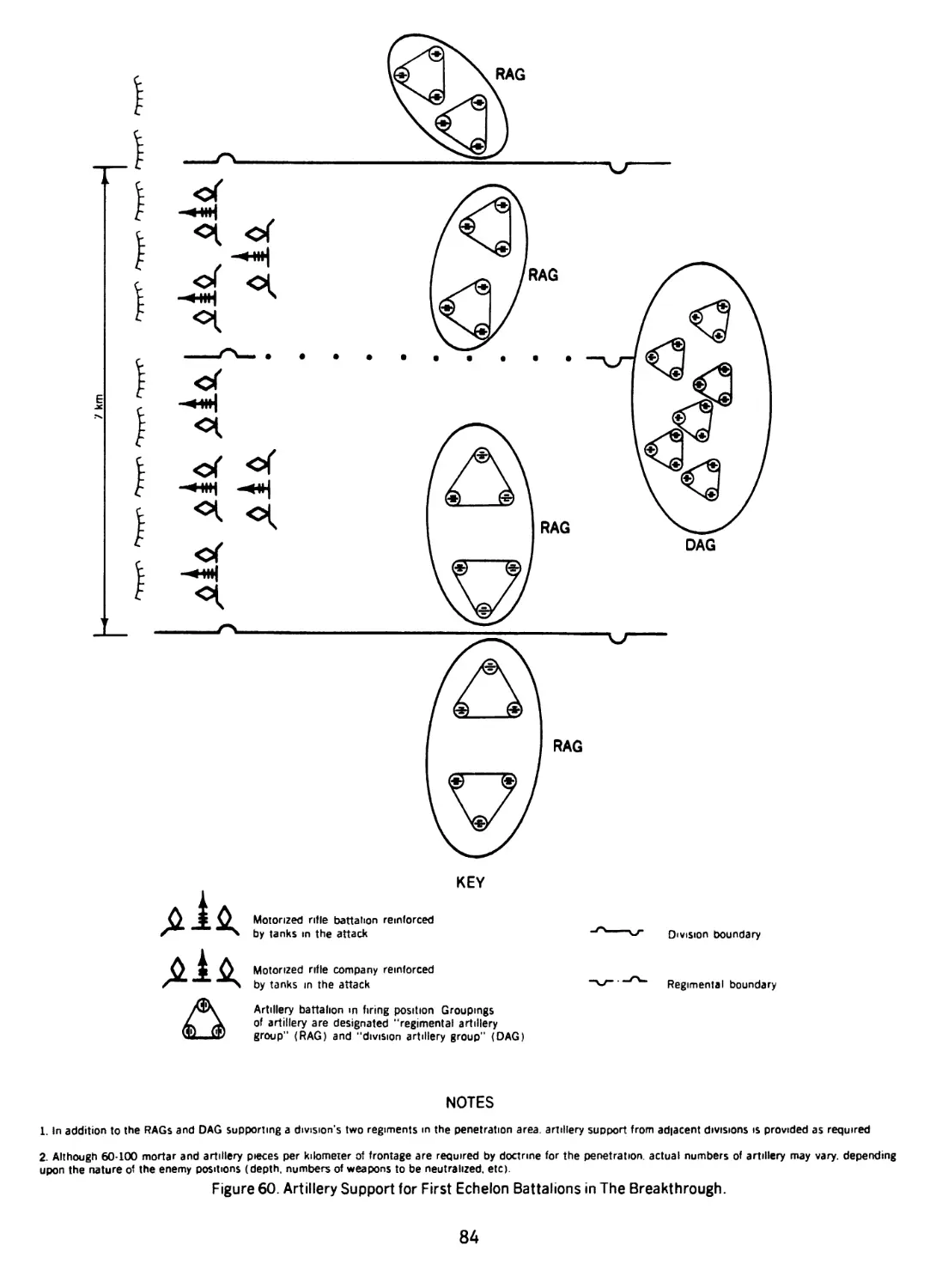

60. Artillery Support for First Echelon Battalions in the Breakthrough ........................84

61. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Deploying from the March to Participate in a Division

Breakthrough Operation .........................................................................88

62. UZ-2 Bangalore Torpedo.................................................................... 89

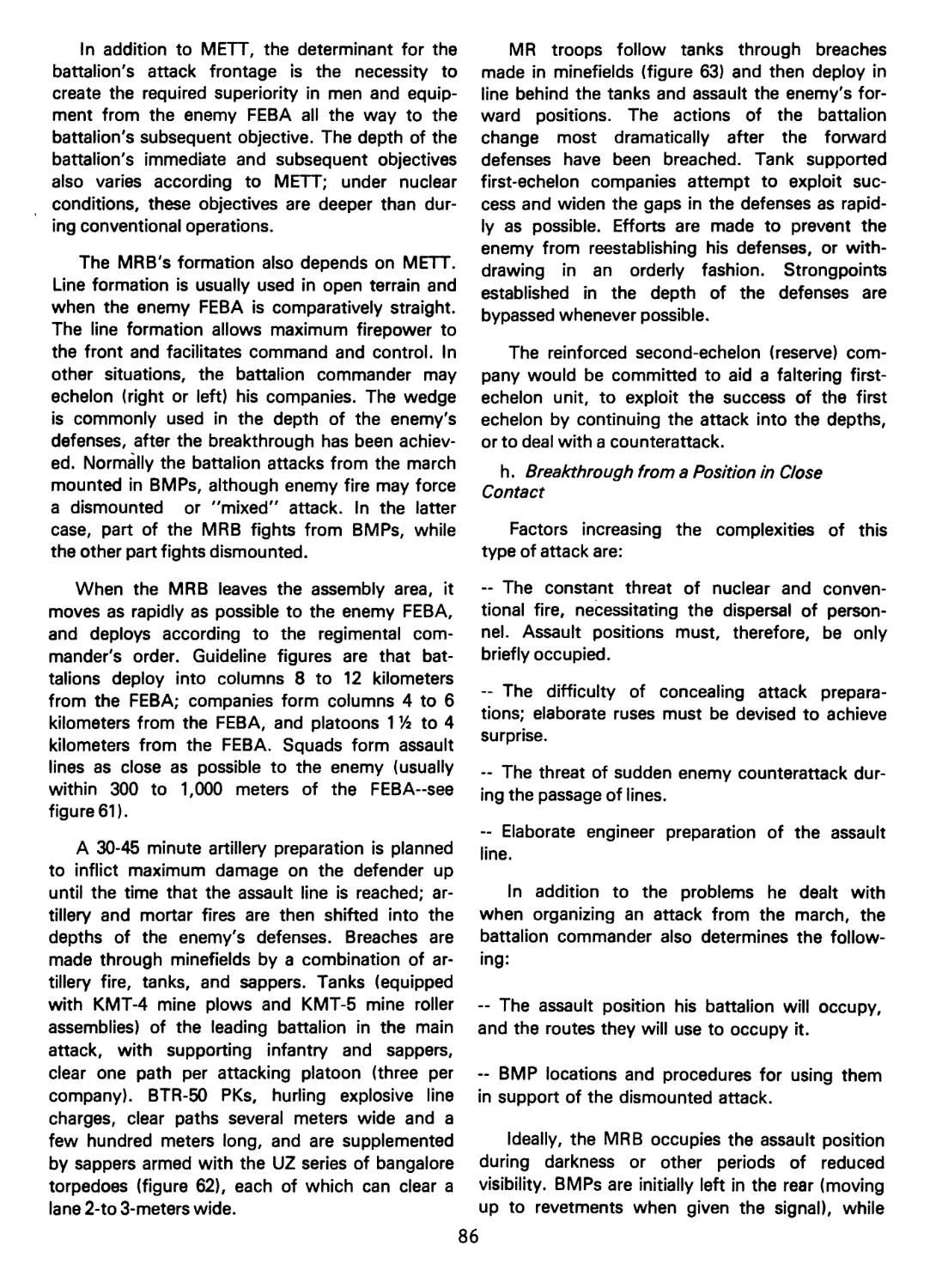

63. Tanks Clear Breaches Through Mine Fields for Motorized Rifle Troops.........................89

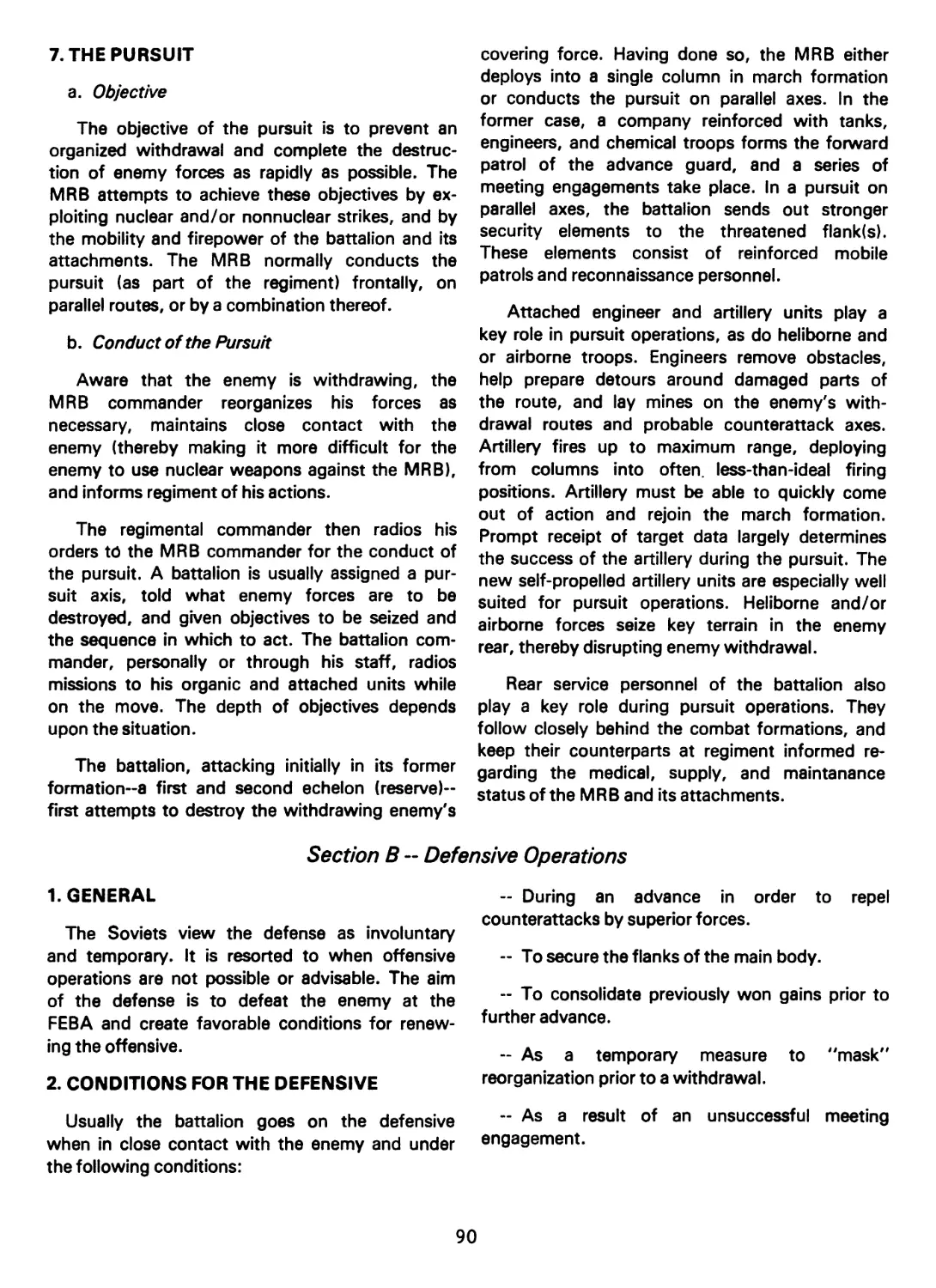

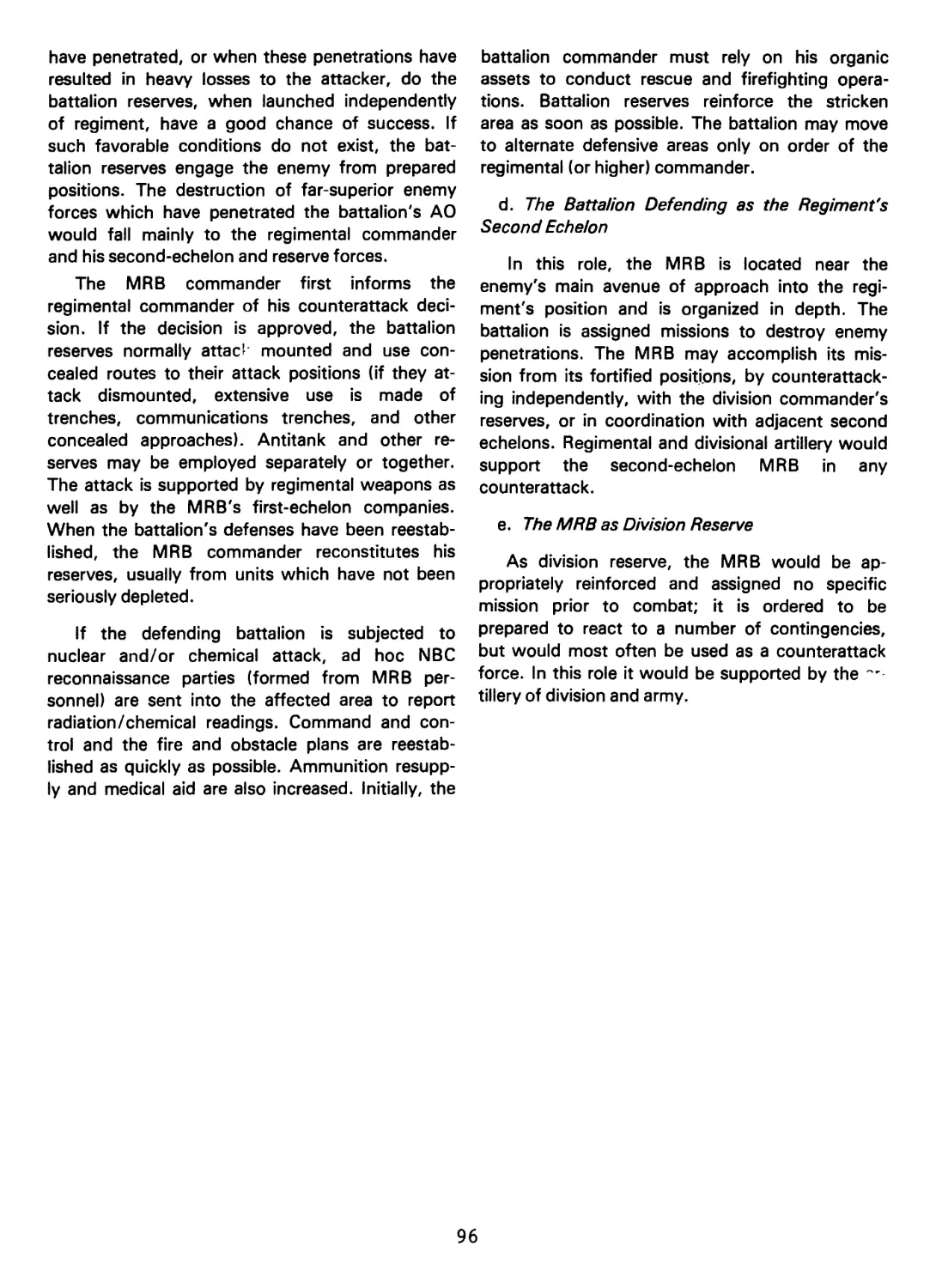

64. The Motorized Rifle Battalion in the Defense................................................94

65. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Acting as the Forward Area Security Force............97

66. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Acting as the Rear Guard During a Regimental Withdrawal ... 99

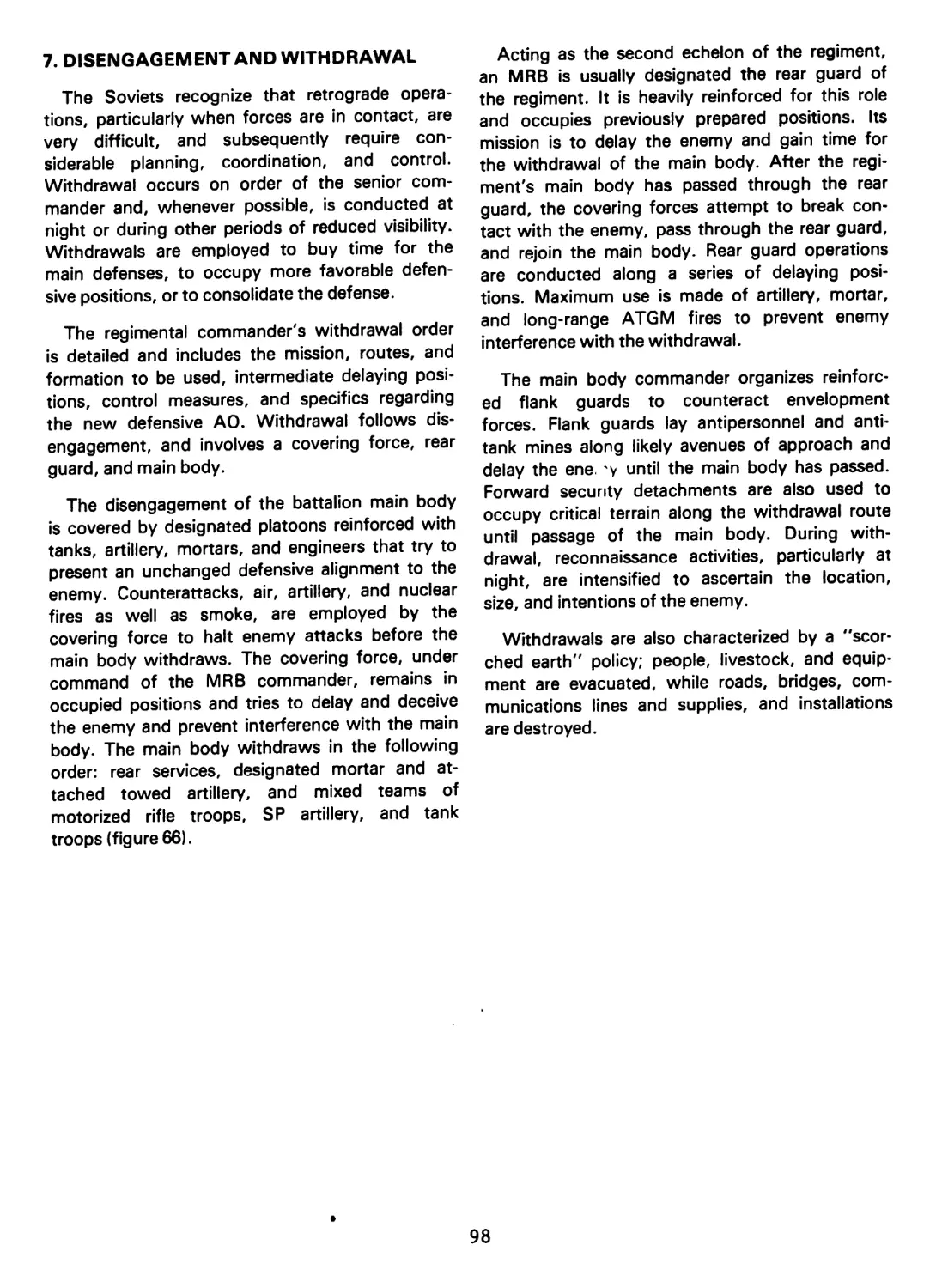

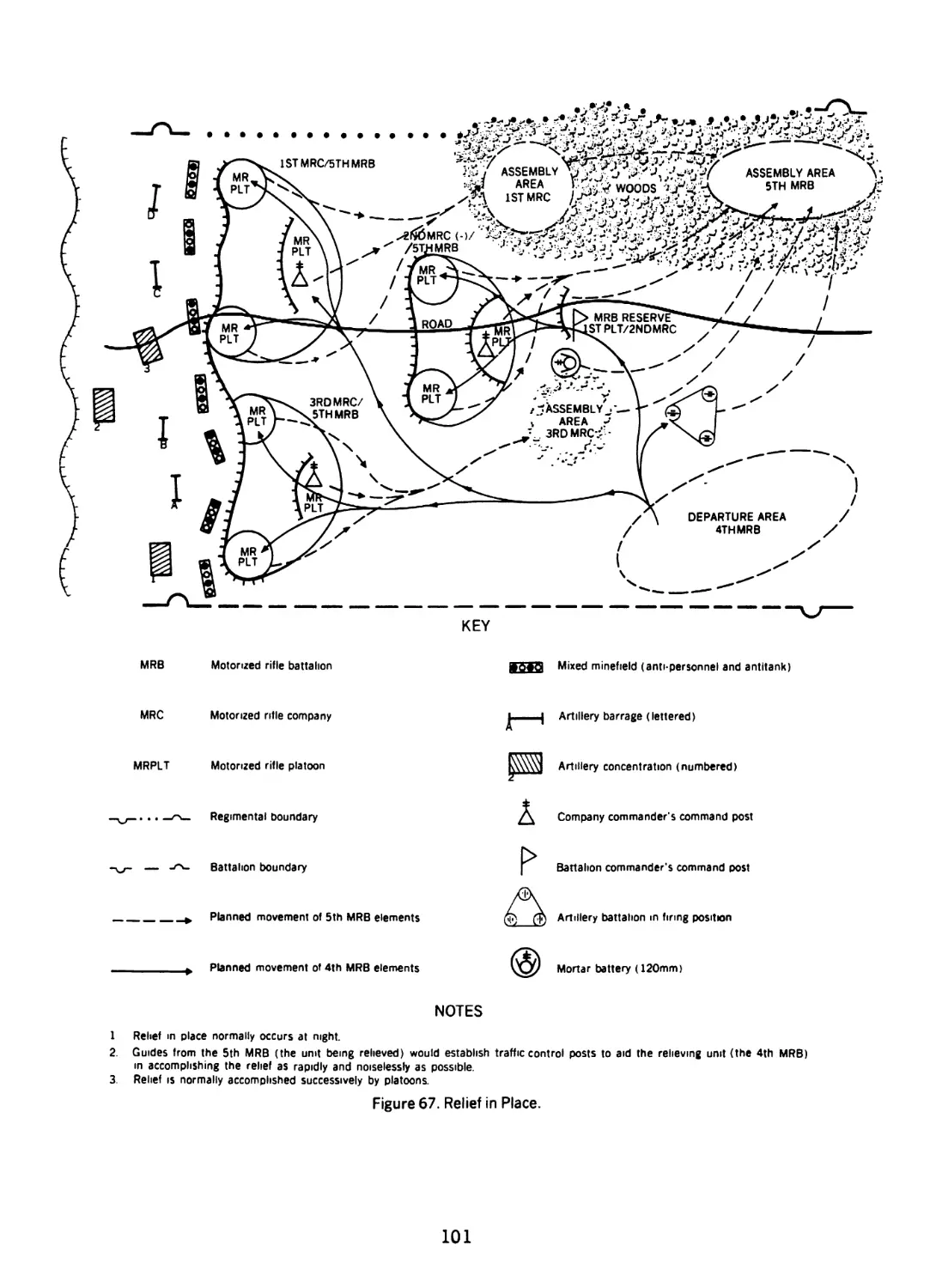

67. Relief in Place ..........................................................................101

68. The Urbanization Factor....................................................................юз

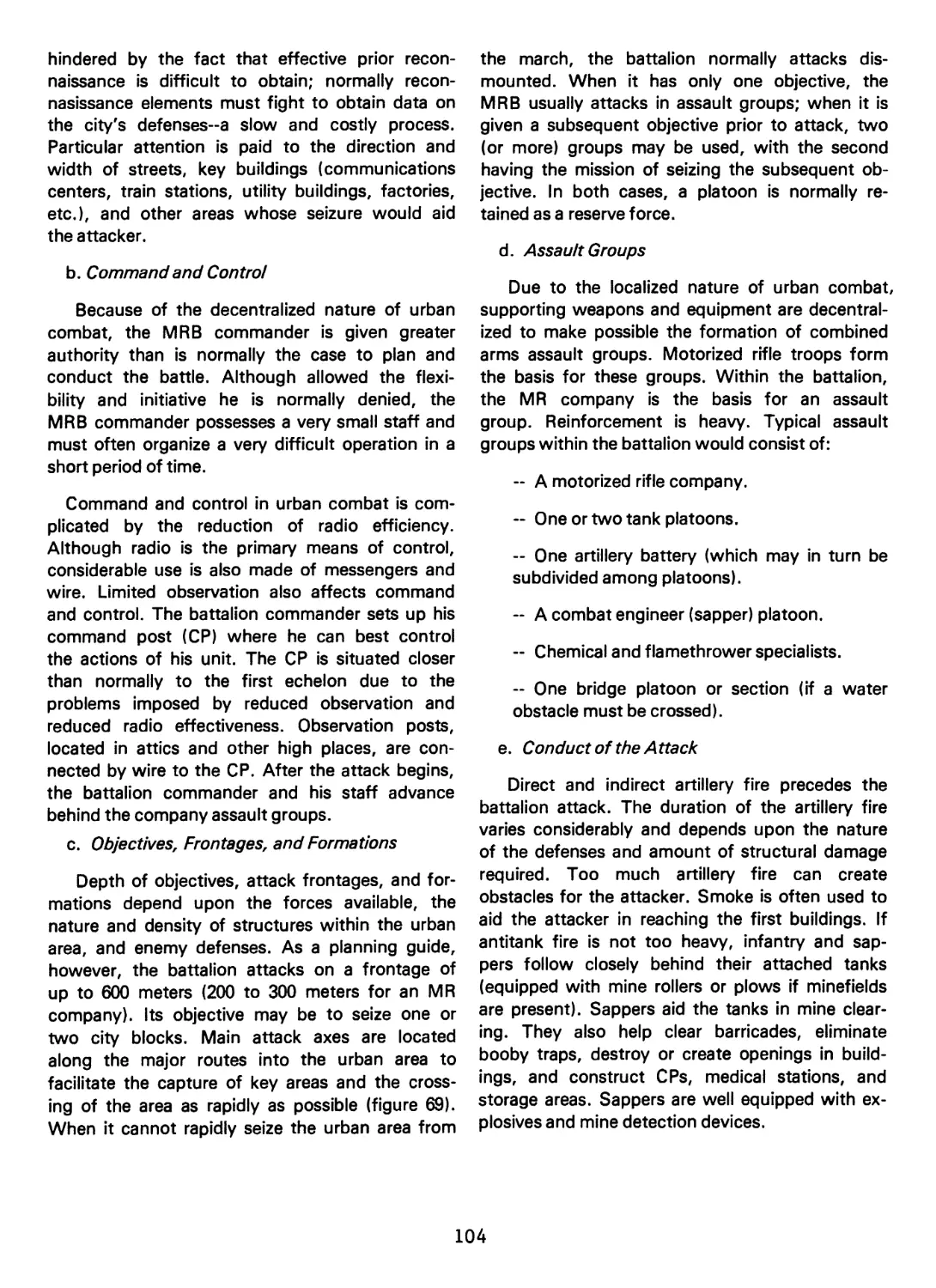

69. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Attacking a Built-Up Area..........................105

70. Combat-in-Cities Exercises................................................................106

71. Flamethrower Personnel Play an Important Role in Urban Combat.............................107

72. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Defending a Built-Up Area..........................108

73. A BTR-Equipped Motorized Rifle Battalion Preparing for a Heliborne Operation...............no

74. The FLOGGER Series Provide Air-Ground Support ............................................110

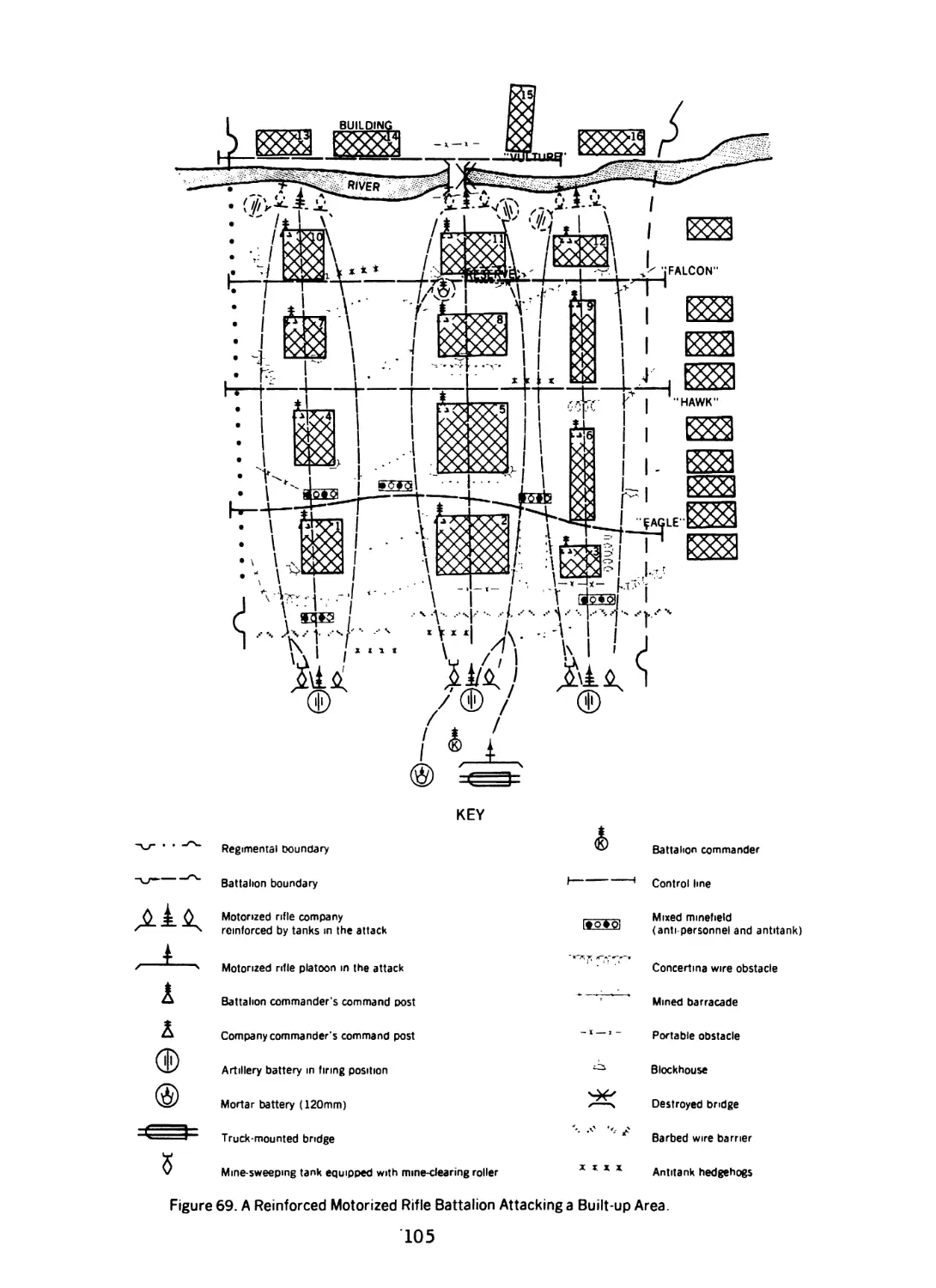

75. Helicopter Gunship/Troop Carriers ........................................................111

a. HIND .................................................................................. 111

b. HIP......................................................................................in

76. The HOPLITE Performs Tactical Reconnaissance..............................................112

77. The HIP Can Conduct Aerial Minelaying.....................................................112

78. The Heavy Transport Helicopter, HOOK ......................................................из

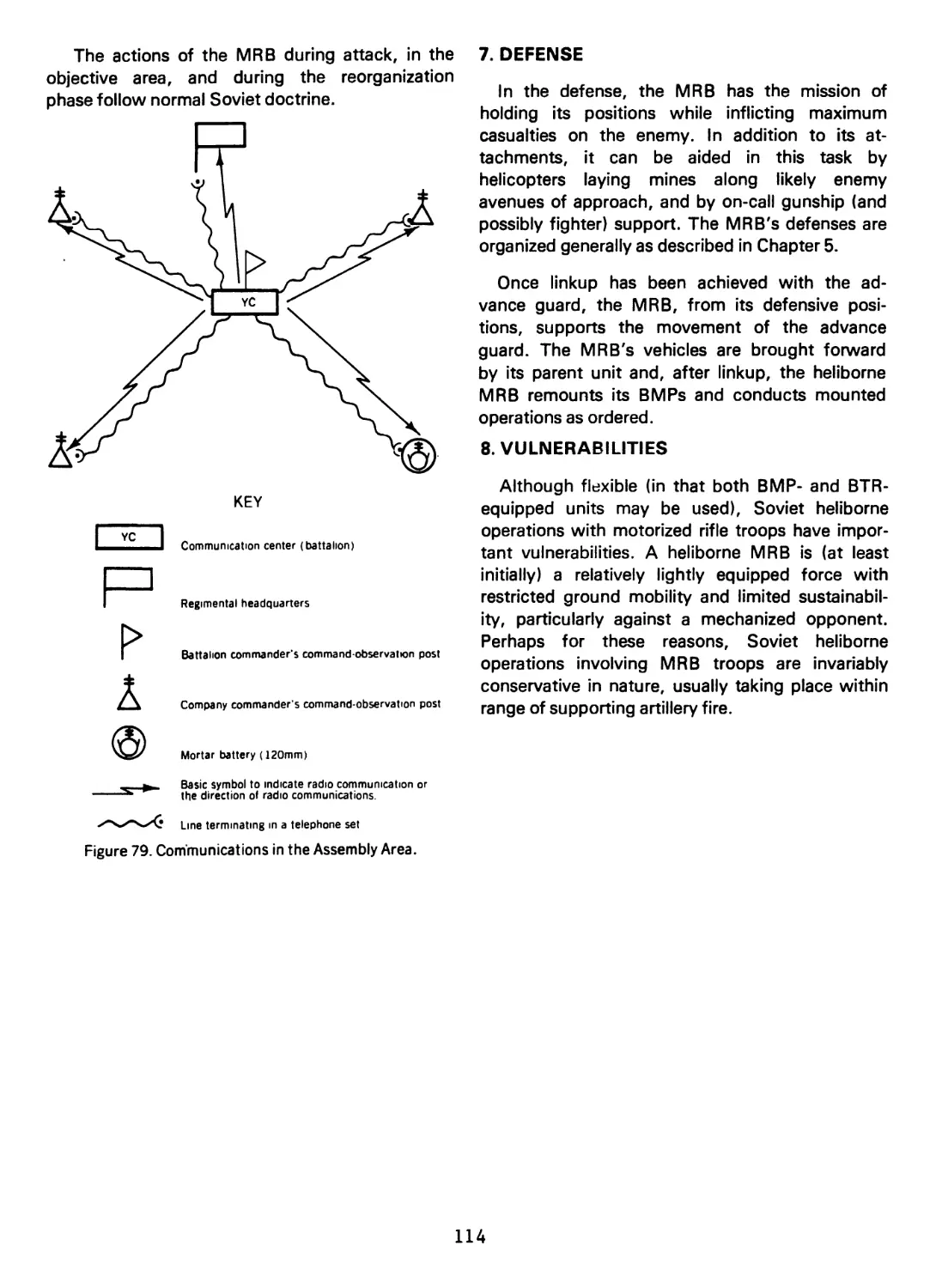

79. Communications in the Assembly Area ......................................................114

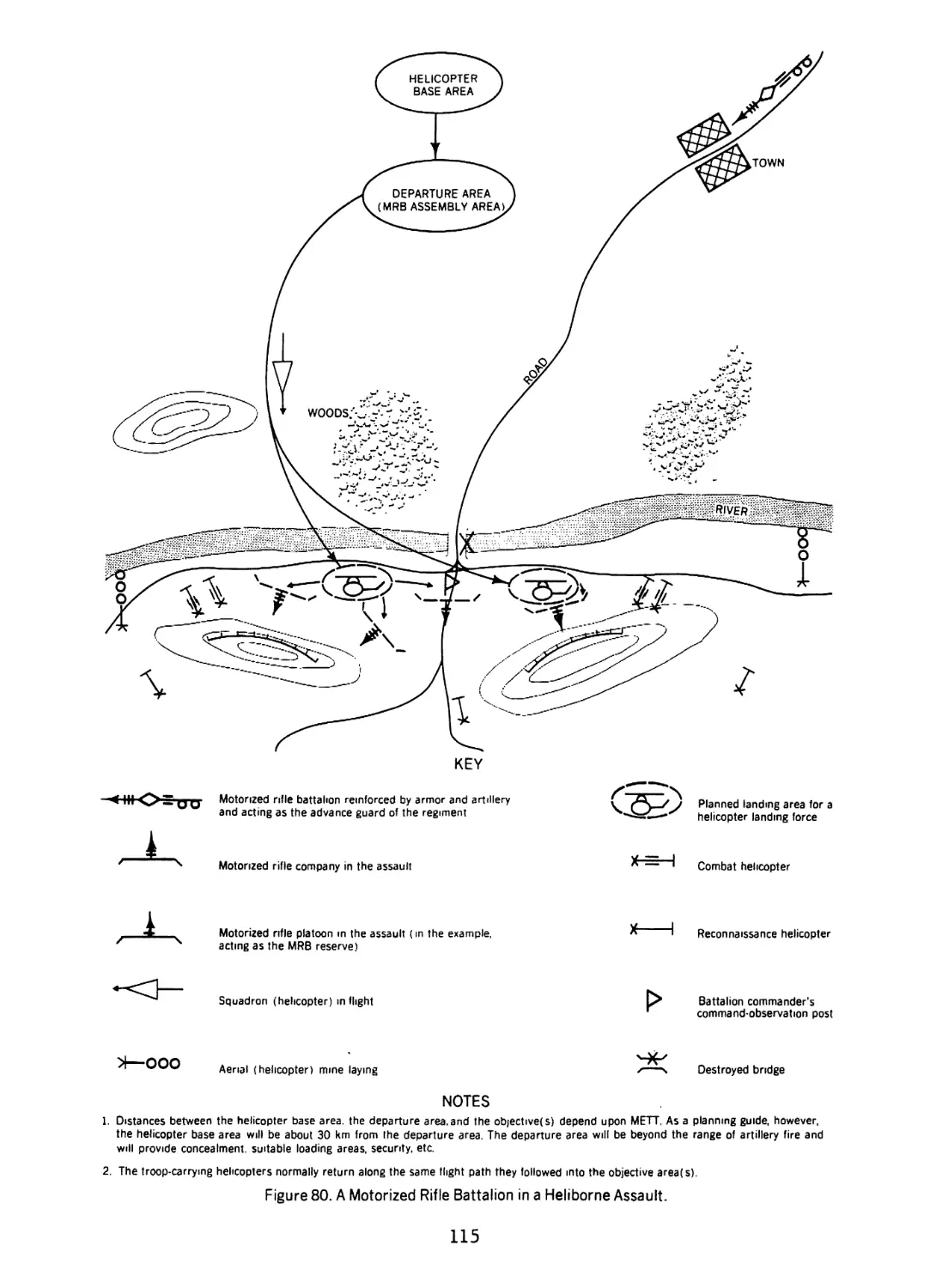

80. A Motorized Rifle Battalion in a Heliborne Assault........................................115

81. Reconnaissance of Both River Banks Usually Precedes the Main Assault......................117

82. The Senior Engineer Officer Controls the Crossing.........................................118

83. Self-Propelled Artillery and ZSU-23-4s Supporting a River Crossing........................119

84. T-62s Preparing for a River Crossing.................................................... 119

85. SA-7 Gunners Supplement Other Air Defense Weapons During a Water-Crossing Operation.......120

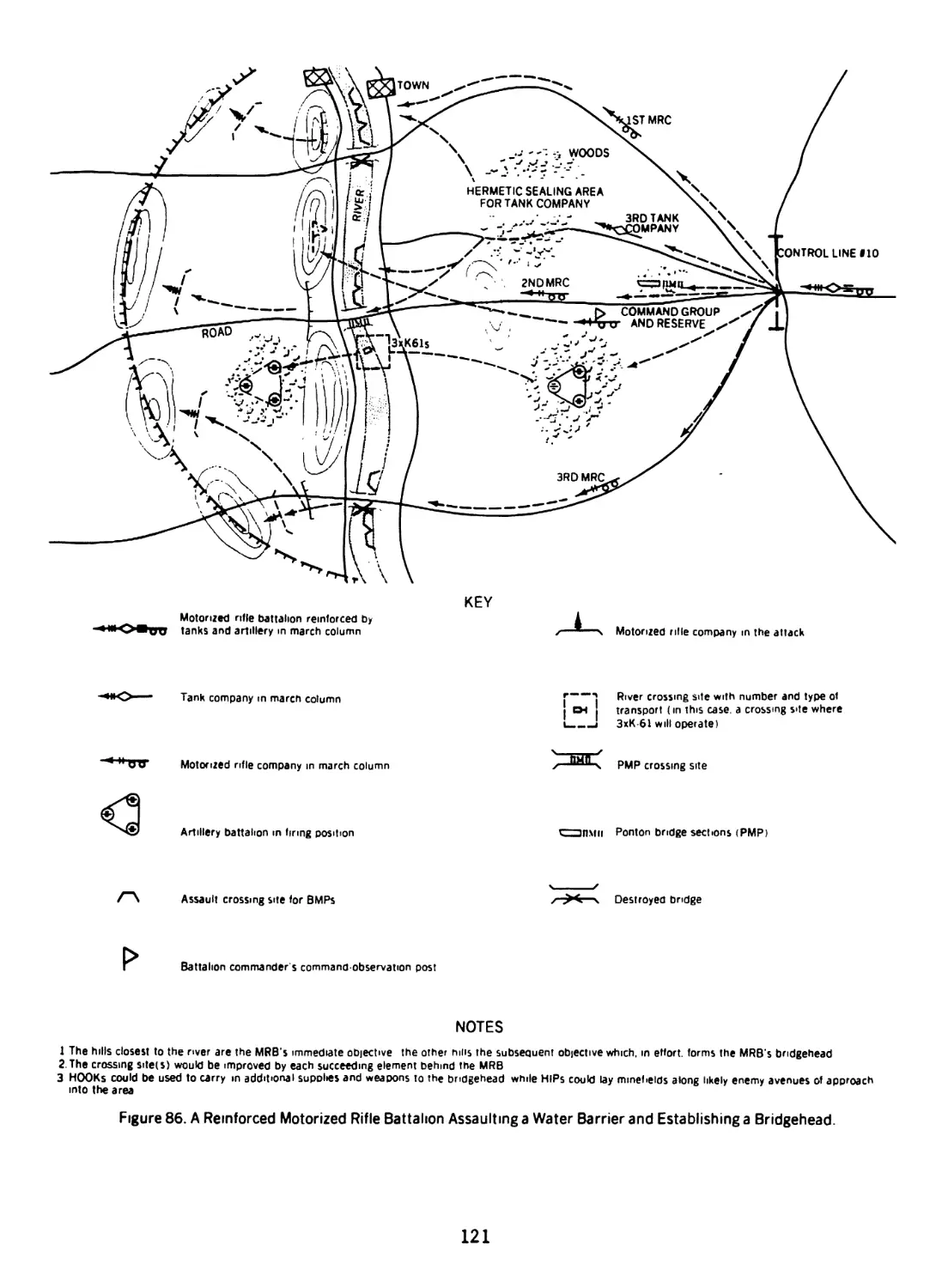

86. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Assaulting a Water Barrier and Establishing

a Bridgehead....................................................................................121

87. Attached Armor Rejoins Motorized Rifle Troops As Soon As Possible in a River-Crossing

Operation.......................................................................................122

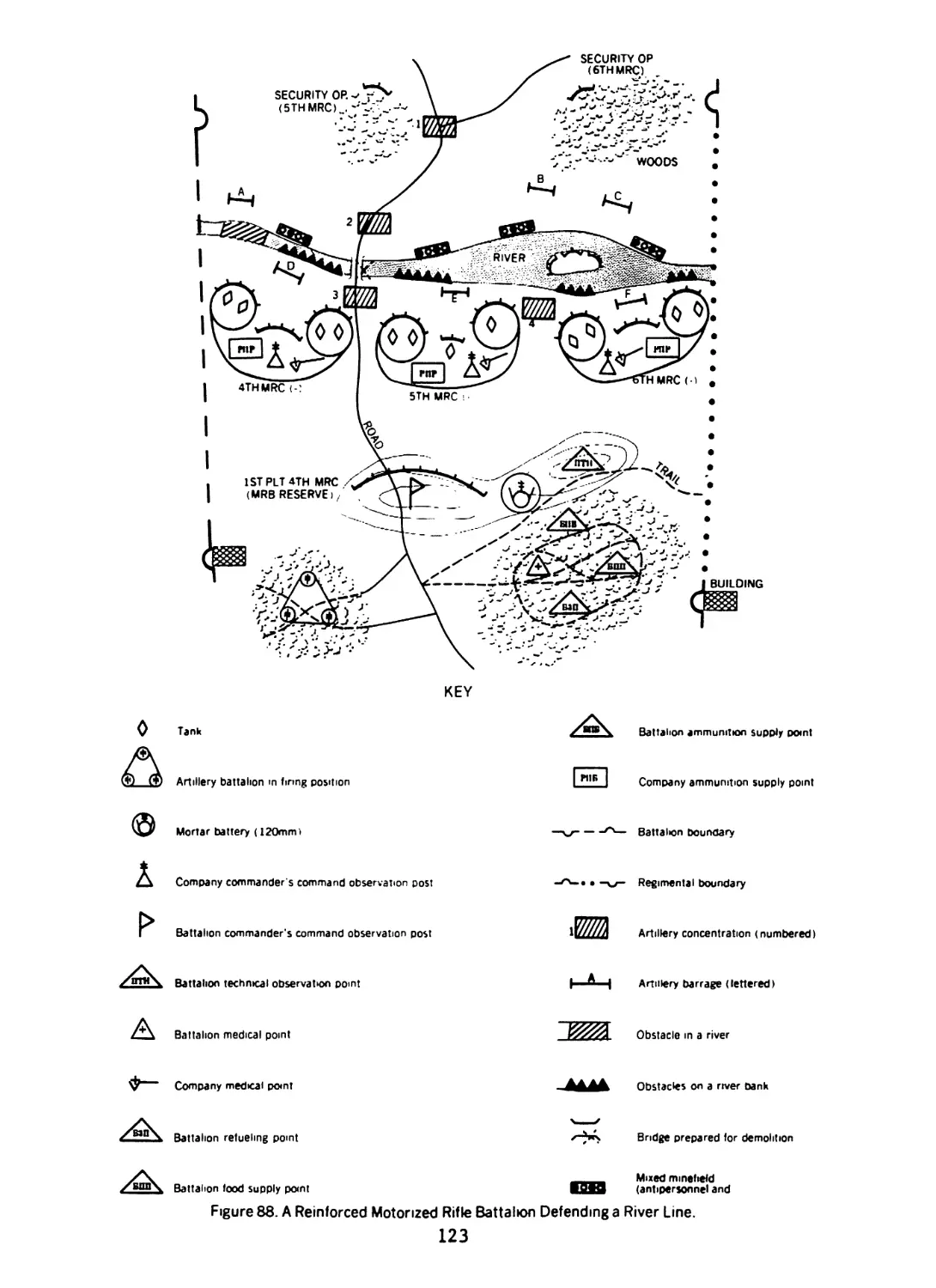

88. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Defending a River Line. ......................... 123

xi

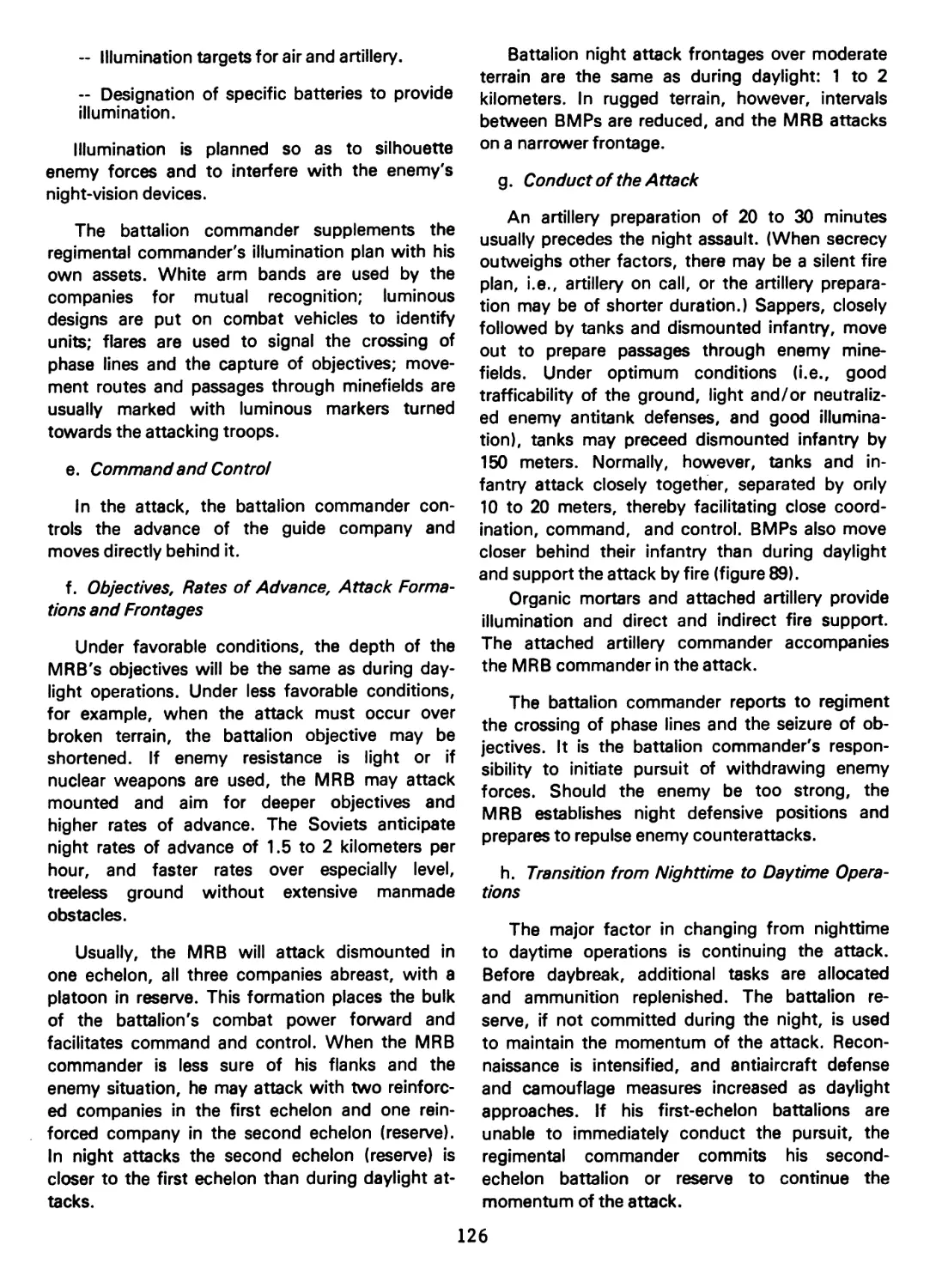

89. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Conducting a Night Attack ...................127

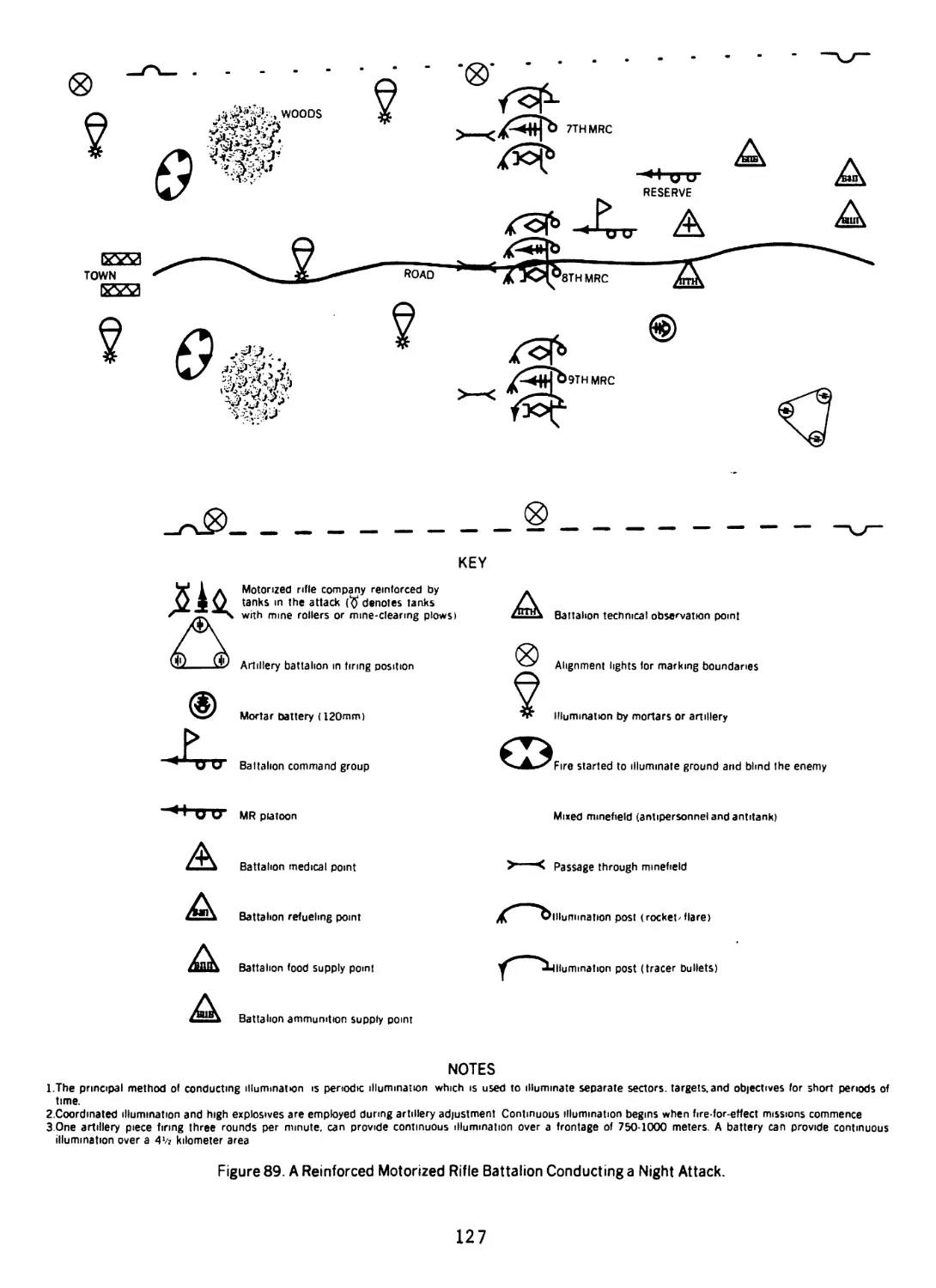

90. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion in a Night Defense...........................129

91. Naval Infantry on Parade in Moscow .................................................130

92. Naval Infantry Often Form the First Echelon in a Seaborne Assault...................131

93. Embarkation and Debarkation Points..................................................132

94. Amphibious Ships....................................................................133

a. ALLIGATOR Class .................................................................133

b. ROPUCHA Class....................................................................133

c. POLNOCNY Class...................................................................134

95. Amphibious Assaults May Be Conducted With Air Cushion Vehicles......................134

96. A Reinforced Motorized Rifle Battalion Conducting an Amphibious Assault.............135

xii

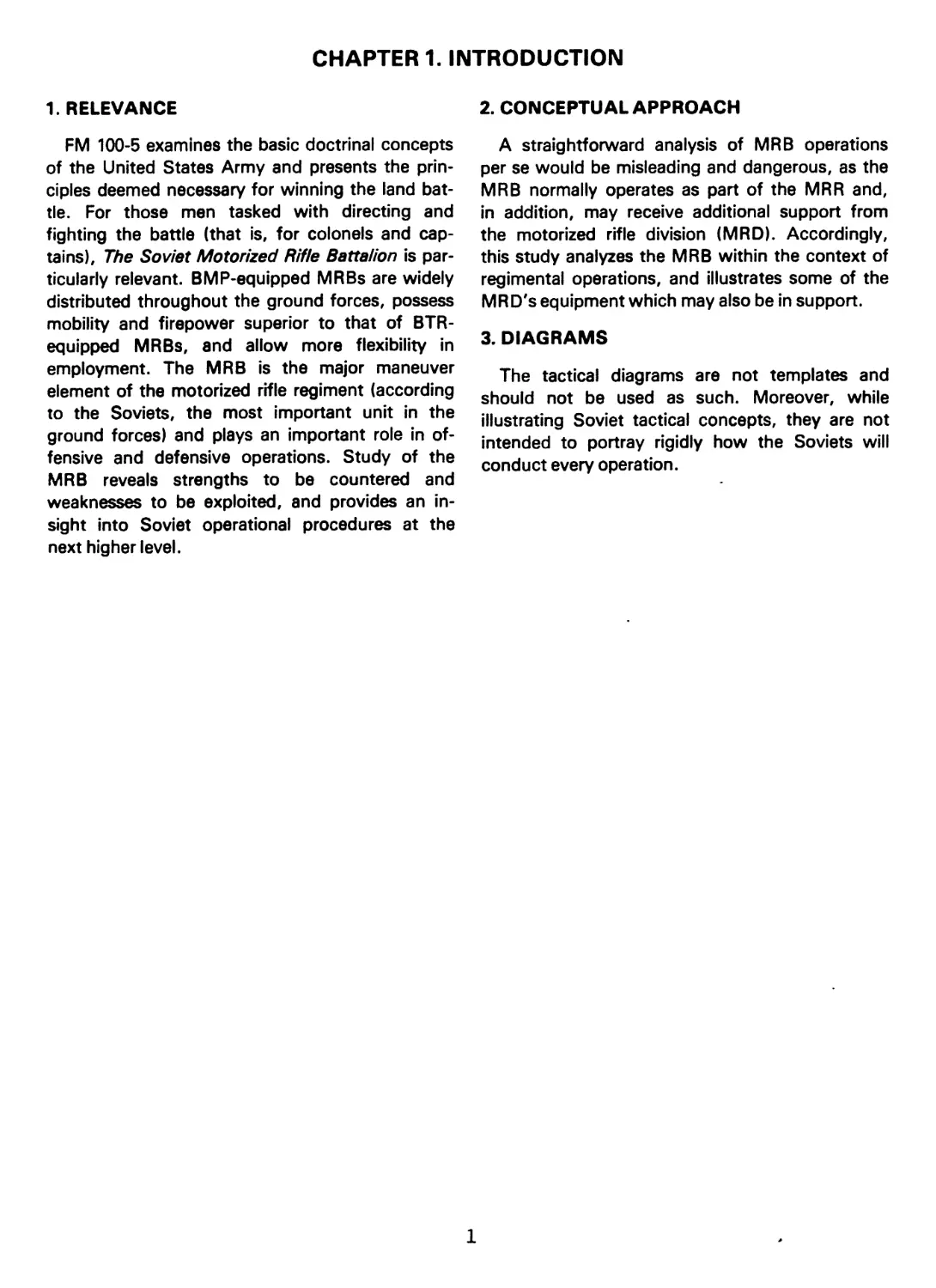

CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION

1. RELEVANCE

FM 100-5 examines the basic doctrinal concepts

of the United States Army and presents the prin-

ciples deemed necessary for winning the land bat-

tle. For those men tasked with directing and

fighting the battle (that is, for colonels and cap-

tains), The Soviet Motorized Rifle Battalion is par-

ticularly relevant. BMP-equipped MRBs are widely

distributed throughout the ground forces, possess

mobility and firepower superior to that of BTR-

equipped MRBs, and allow more flexibility in

employment. The MRB is the major maneuver

element of the motorized rifle regiment (according

to the Soviets, the most important unit in the

ground forces) and plays an important role in of-

fensive and defensive operations. Study of the

MRB reveals strengths to be countered and

weaknesses to be exploited, and provides an in-

sight into Soviet operational procedures at the

next higher level.

2. CONCEPTUAL APPROACH

A straightforward analysis of MRB operations

per se would be misleading and dangerous, as the

MRB normally operates as part of the MRR and,

in addition, may receive additional support from

the motorized rifle division (MRD). Accordingly,

this study analyzes the MRB within the context of

regimental operations, and illustrates some of the

MRD's equipment which may also be in support.

3. DIAGRAMS

The tactical diagrams are not templates and

should not be used as such. Moreover, while

illustrating Soviet tactical concepts, they are not

intended to portray rigidly how the Soviets will

conduct every operation.

1

CHAPTER 2. DOCTRINE, TACTICS, AND TRENDS

Section A -- Doctrine

1. GENERAL

2. OFFENSIVE PRINCIPLES

Soviet doctrine stresses that the offensive is

the decisive form of combat. To achieve success,

the Soviets stress high average rates of advance

(30-50 kilometers per day in nonnuclear situations

and 50-80 kilometers per day when nuclear

weapons are used) by combined arms units

(figure 1).

To achieve such high rates of advance, the

Soviets advocate the concentration of numerically

superior forces and firepower within selected sec-

tors; the use of airborne, heliborne, and special

operations forces throughout the depth of the

enemy rear area; and the achievement of surprise

(figure 2). Should nuclear/chemical weapons not

be used, conventional artillery would be used to

achieve the desired density of firepower. Soviet

writings stress the critical transition from non-

nuclear to nuclear operations, and frequently ex-

ercise going from one mode of combat to the

other.

Defensive concepts are less frequently describ-

ed and practiced. Although they acknowledge

that a particular situation may dictate defensive

action, the Soviets stress that the primary pur-

pose of the defense is to prepare for the resump-

tion of offensive operations as soon as possible.

Soviet offensive doctrine is based upon com-

bined arms operations, that is the closely coord-

inated efforts of the missile, tank, motorized rifle,

artillery, and combat support units. This doctrine

does not separate fire and maneuver; it seeks

ways to improve their integration and effec-

tiveness.

In forming combined arms groupings, the

Soviets do not cross-attach units as in some

Western armies. Within a Soviet motorized rifle

regiment for example, one tank company may be

assigned to a MRB, but that MRB will not, in

turn, assign one of its MR companies to the tank

battalion. In the Soviet Army, units are often at-

tached or placed in support of other units.

Attachments are more responsive to the com-

mander of the unit to which they are attached,

while units placed in support are controlled

through their parent unit commander.

The Soviets identify three types of combat

action--the meeting engagement,* the offense,

and the defense. The offense is further subdivid-

ed into the attack and its exploitation, and the

pursuit culminating in encirclement. The offensive

is conducted by maximizing maneuver, firepower,

and shock action. Approximately 80 percent of a

Figure 1. Soviet Offensive Doctrine Is Based on Combined Arms Combat.

•АлтюидЬ the meeting engagement is offensive in nature, the Soviets, in order to emphasize its importance, recognize it as a

xarate form of combat.

battalion's tactical training is offensive in nature,

a bias also reflected in the Soviet press.

a. Airborne Drop in the Enemy Rear Area.

b. Heliborne Forces Rush To Establish a Bridgehead.

Figure 2. Airborne and Heliborne Troops Are Selectively

Used to Maintain Offensive Monentum.

The Soviets define maneuver as the movement

of a force into a favorable position (in relation to

the enemy), from which it can launch an effective

attack. The frontal attack and the envelopment

are the basic types of maneuver described by the

Soviets, who clearly favor the latter (figure 3).

Envelopment is often employed in the meeting

engagement and generally whenever the enemy

has an assailable flank. Envelopment is also often

conducted in conjunction with a frontal attack

designed to pin down enemy forces.

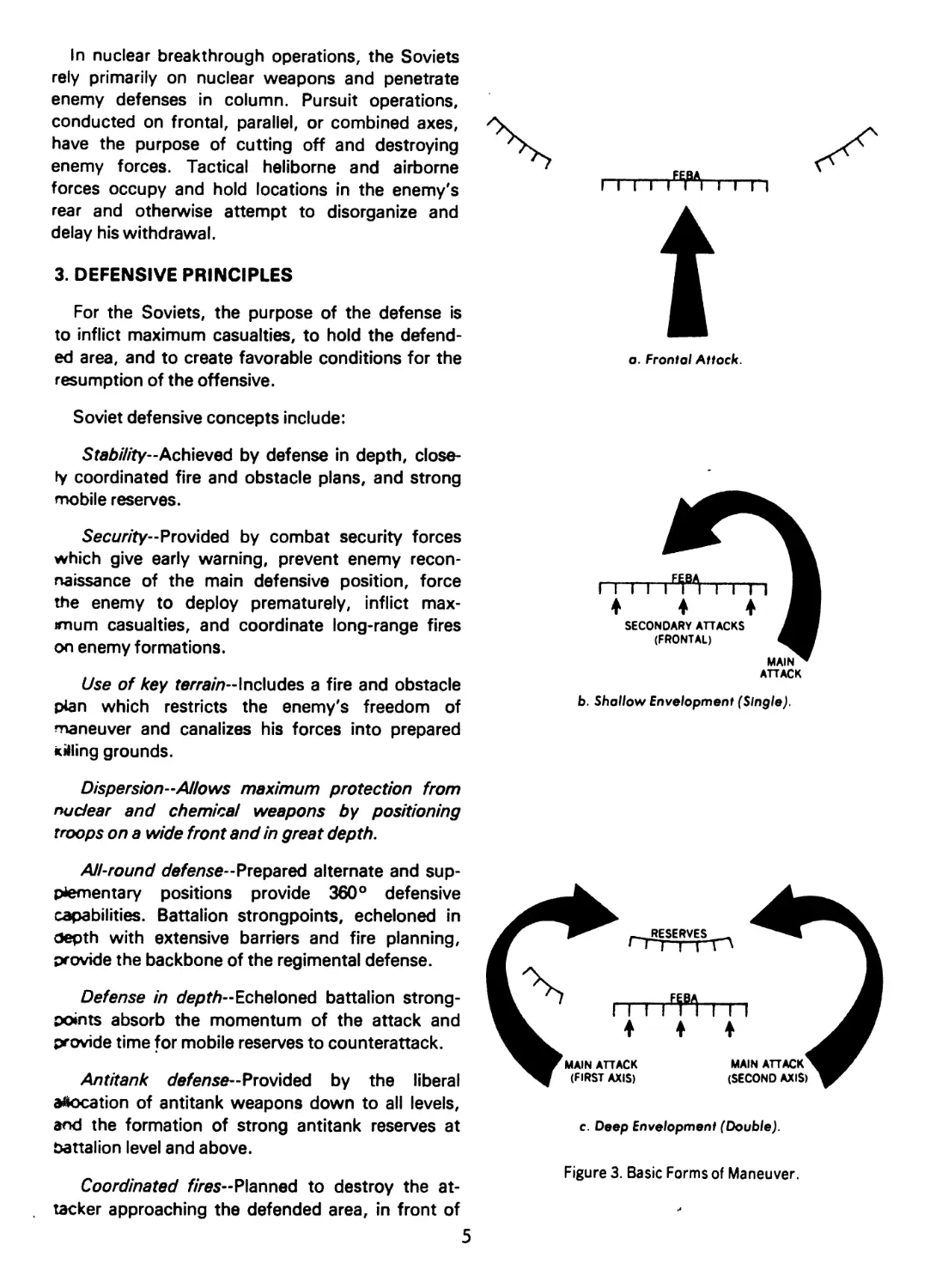

Because of their perceptions of the fluid nature

of modem war, the Soviets place more emphasis

on the meeting engagement (combat between op-

posing columns rapidly advancing toward each

other) than on any other form of offensive action

(figure 4). Meeting engagements require a high

degree of initiative because of their inherent

characteristics:

- The need to seize and maintain the in-

itiative.

- Freedom of maneuver, often with open

flanks.

- Combat on a wide front.

- Rapid troop deployment.

- Mobile, high speed combat.

Although the Soviets believe that their

numerous intelligence gathering means will help

commanders prepare for the meeting engage-

ment, they acknowledge that planning must often

be conducted with incomplete data on enemy

forces. Soviet commanders are encouraged to ag-

gressively seek meeting engagements and to

make rapid decisions based upon available in-

telligence.

Nuclear and nonnuclear breakthrough opera-

tions may be conducted against hasty, prepared,

or fortified defenses. In the breakthrough, the

Soviets envision penetration, accompanied

whenever possible by envelopment, the relegation

of pockets of resistance for destruction to

second-echelon formations, meeting engagements

with advancing enemy reserves, and pursuit of

withdrawing enemy forces. Against a prepared

defensive position, and when nuclear weapons

are not used, the Soviets concentrate a reinforced

battalion and the fire of 60-100 artillery pieces per

kilometer of breakthrough sector, while exerting

pressure all along the remaining portion of the

enemy defenses.

4

In nuclear breakthrough operations, the Soviets

rely primarily on nuclear weapons and penetrate

enemy defenses in column. Pursuit operations,

conducted on frontal, parallel, or combined axes,

have the purpose of cutting off and destroying

enemy forces. Tactical heliborne and airborne

forces occupy and hold locations in the enemy's

rear and otherwise attempt to disorganize and

delay his withdrawal.

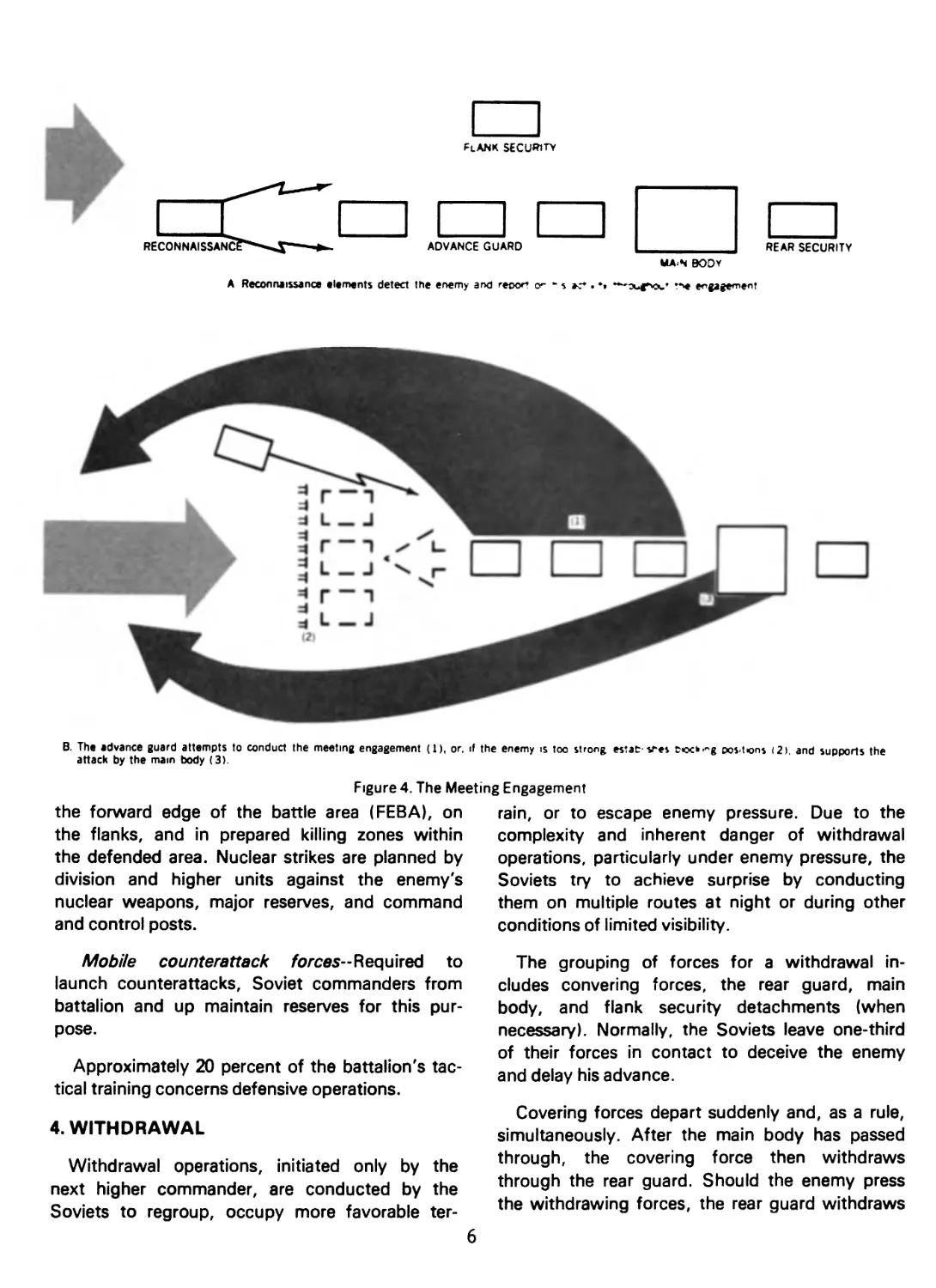

3. DEFENSIVE PRINCIPLES

For the Soviets, the purpose of the defense is

to inflict maximum casualties, to hold the defend-

ed area, and to create favorable conditions for the

resumption of the offensive.

o. Frontal Atfock.

Soviet defensive concepts include:

Sfab/7/ty-Achieved by defense in depth, close-

ly coordinated fire and obstacle plans, and strong

mobile reserves.

Secur/ty-Provided by combat security forces

which give early warning, prevent enemy recon-

naissance of the main defensive position, force

the enemy to deploy prematurely, inflict max-

imum casualties, and coordinate long-range fires

on enemy formations.

Use of key te/ra/h-lncludes a fire and obstacle

plan which restricts the enemy's freedom of

maneuver and canalizes his forces into prepared

killing grounds.

Dispersion-AHows maximum protection from

nudear and chemical weapons by positioning

troops on a wide front and in great depth.

АН-round defense-Prepared alternate and sup-

plementary positions provide 360° defensive

capabilities. Battalion strongpoints, echeloned in

oepth with extensive barriers and fire planning,

provide the backbone of the regimental defense.

Defense in cfepth-Echeloned battalion strong-

points absorb the momentum of the attack and

provide time for mobile reserves to counterattack.

Antitank defense— Provided by the liberal

aftocation of antitank weapons down to all levels,

and the formation of strong antitank reserves at

battalion level and above.

Coordinated ffires-Planned to destroy the at-

tacker approaching the defended area, in front of

c. Deep Envelopment (Double).

Figure 3. Basic Forms of Maneuver.

flank security

ADVANCE GUARD

MAN BODY

REAR SECURITY

A Reconnaissance elements detect the enemy and герои cr - s . ♦» ’M engagement

enemy is too strong estat ve$ tco^g posaons (2), and supports the

Figure 4. The Meeting Engagement

B. The advance guard attempts to conduct the meeting engagement (1), or, if the

attack by the main body (3).

the forward edge of the battle area (FEBA), on

the flanks, and in prepared killing zones within

the defended area. Nuclear strikes are planned by

division and higher units against the enemy's

nuclear weapons, major reserves, and command

and control posts.

Mobile counterattack /orces-Required to

launch counterattacks, Soviet commanders from

battalion and up maintain reserves for this pur-

pose.

Approximately 20 percent of the battalion's tac-

tical training concerns defensive operations.

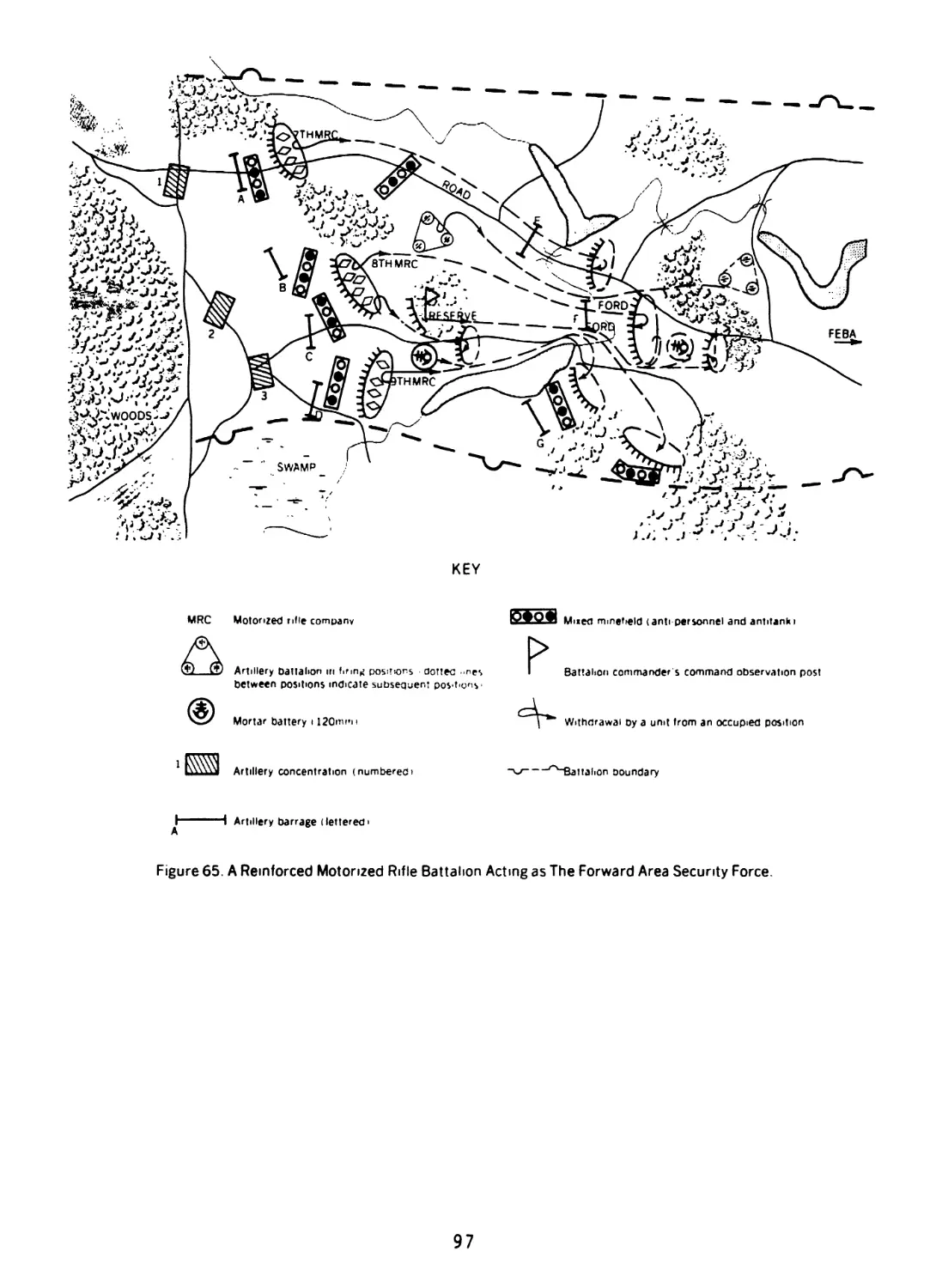

4. WITHDRAWAL

Withdrawal operations, initiated only by the

next higher commander, are conducted by the

Soviets to regroup, occupy more favorable ter-

rain, or to escape enemy pressure. Due to the

complexity and inherent danger of withdrawal

operations, particularly under enemy pressure, the

Soviets try to achieve surprise by conducting

them on multiple routes at night or during other

conditions of limited visibility.

The grouping of forces for a withdrawal in-

cludes convering forces, the rear guard, main

body, and flank security detachments (when

necessary). Normally, the Soviets leave one-third

of their forces in contact to deceive the enemy

and delay his advance.

Covering forces depart suddenly and, as a rule,

simultaneously. After the main body has passed

through, the covering force then withdraws

through the rear guard. Should the enemy press

the withdrawing forces, the rear guard withdraws

6

in a leapfrog manner, rendering mutual fire sup-

port. If the rear guard is successful, withdrawal of

the main body is unimpeded.

The rear guard occupies defensive positions

behind first-echelon defense forces. Subsequent

defensive positions are designated for the rear

guard, which conducts ambushes and erects bar-

riers as it withdraws to subsequent positions. The

rear guard moves to subsequent positions in a

leapfrog manner, rendering mutual support and

defending each position.

Prior to arrival of the rear guard in the newly

designated area of defense, reconnaissance

groups are formed. These groups conduct a

survey of the new area, determine the area to be

occupied by each unit, designate approach routes

to them, mark off any mined or contaminated

areas, and test the water. As the main body ap-

proaches the area, its subordinate elements are

met by guides from the reconnaissance groups

and are taken to their designated areas.

Security is organized as soon as the lead

elements close on the new defensive areas, and

engineering work is begun.

Section В - Tactics

1. GENERAL

In spite of the superior qualities of the BMP vis-

a-vis the BTR, we are not aware of any new

regulations governing employment of BMP-

equipped and BTR-equipped units. Soviet com-

manders still seem to be debating the tactical

employment of the BMP in an effort to maximize

its principal strengths vis-a-vis the BTR: superior

firepower (particularly antitank) and cross-country

mobility, and better crew protection. Training is

also being conducted to determine the optimum

use of BMPs operating in close coordination with

tanks and artillery.

The BMP's superiority over the BTR makes it

likely that the BMP-equipped units of a motorized

rifle division (MRD) will be assigned these key

roles:

- Reconnaissance.

- Use in the forward detachment.

- Positioning in the first echelon during

nuclear conditions, and/or if enemy defenses

have been sufficiently neutralized; otherwise

in the second echelon as an exploitation force

(The BTR-equipped regiment(s) would form

the MRD's first echelon).

- Operating on the main axis of attack.

2. ECHELONS AND RESERVES

a. General

In the West, there has been an overdramatiza-

tion of the Soviet deployment system, as well as

confusion* over how the system, particularly

echelonment, works. Basically, the Soviet system

of echelonment with "two up" and "one back" is

similar to our own and seeks the same effects in

the attack:

- Timely buildup of the attack effort.

- Beating the enemy in the use of corres-

ponding reserves.

- Preventing an overdensity of troops and

equipment (thereby denying the enemy

lucrative nuclear targets).

- Achieving high rates of advance by attacks

in depth.

And in the defense:

- Presenting the enemy with a series of

defensive positions.

- - Preventing an overdensity of troops and

equipment. The difference between the

Soviet and US systems concerns exactness in

terminology and preparation.

b. Definitions

The first echelon is the most important

echelon and normally consists of up to two-thirds

of the forces available. In the attack it comprises

the leading assault units; in the defense, it com-

prises the forward defense units on the FEBA.

By frequently writing "second echelon (reserve)," Soviet writers have contributed to the confusion.

7

The second echelon, normally consisting of

about one-third of the available forces, gives the

commander the capability to intensify the attack,

to shift rapidly the attack effort from one axis to

another, to repulse counterattacks, and to replace

heavily attrited first-echelon units.

The commanders of the first and second

echelons receive their missions prior to combat.

First-echelon commanders are assigned immediate

and subsequent objectives and an axis of further

advance, while second-echelon commanders

receive an immediate objective and an axis for

further advance. Commanders must get permis-

sion from the next higher commander to commit

their second echelon. A second echelon is not

committed in a piecemeal fashion.

Reserves clearly differ from echelons. When

the Soviets write "second echelon (reserve)/'

they are not equating the two; they mean that

sometimes a commander will have a second

echelon and at other times a reserve.

Starting at battalion level, commanders nor-

mally maintain reserves, usually consisting of less

than one-third of the forces available. Reserves

may be of several types (antitank, branch, com-

bined arms) and be employed separately or to-

gether. The commander of the reserve receives

no specific mission prior to battle, but must be

prepared to carry out a number of contingencies.

c. Employment of Echelons and Reserves

The commander's decision for the employ-

ment of his force depends upon METT.* For ex-

ample, because a hasty defense does not have

well-coordinated fire and obstacle plans, speed in

the attack, combined with maximum combat

power forward, is preferred to echeloning. Ac-

cordingly, a single echelon and a reserve would

most probably be used to attack a hasty defense.

Moreover, unless a commander receives

augmentation, he must weaken his assault

elements in order to have two echelons and a

branch or combined arms reserve. For this

reason, units at regimental level and above may,

when attacking in two echelons, have chemical,

engineer, and antitank reserves, but no motorized

rifle, tank, or combined arms reserve. If suitably

augmented, they may have two echelons plus

branch, combined arms, and/or other reserves.

Mission, enemy, terrain and weather, troops available.

The MRB is the lowest level where echelon-

ment occurs in the Soviet Army (the Soviets have

experimented with echelonment within com-

panies, but this practice has been discouraged by

general officers who wrote that such practice

dissipates the company's combat power and in-

creases the command and control problems of

the company commander).

When two echelons and a reserve are

employed, reserves for BTR- and BMP-equipped

battalions could consist of a designated MR unit

(normally a platoon), usually taken from the se-

cond echelon, or a platoon from an attached tank

company.

The antitank reserve of the BTR-equipped

MRB is normally its antitank platoon of manpack

SAGGERS and SPG-9s, while for a BMP- equip-

ped MRB it may be part of an attached tank com-

pany or an attached platoon of the MRR's an-

titank missile battery (figure 5). Both types of

reserves are usually under the battalion com-

mander's direct control.

Depending upon METT, the battalion's second

echelon (reserve) operates from 1 to 3 kilometers

behind the first echelon in order to avoid un-

necessary losses, while being close enough for

timely commitment to battle. When a second

echelon passes through a first echelon, the

former fights independently of the latter, and is

usually supported by fire from the first echelon.

Reserves and the second echelon are recon-

stituted as soon as possible following their com-

mitment.

a. Antitank Reserves in a BTR-Equlpped Unit.

Figure 5. Battalion Antitank Reserves Respond Directly

to the Battalion Commander.

8

Ь A BMP-Equipped Motorized Rifle Battalion Antitank

Reserve.

Figure 5. Battalion Antitank Reserves Respond Directly to

the Battalion Commander. (Continued)

3. COMMAND AND STAFF

a. Command

In the Soviet Army, position and branch are

more important than rank. It is not unheard of for

a commander to be junior to his chief of staff

and/or one or more subordinate commanders. A

Soviet major commanding a regiment could have

lieutenant colonels as his deputies. Moreover, the

combined arms commander commands attach-

ments, regardless of whether or not the com-

mander of the attached unit is superior in rank.

Should an artillery or tank battalion commanded

by a major or lieutenant colonel be attached to a

MRB commanded by a captain, the MRB com-

mander would command both battalions.

b. Chain of Command

To reconstitute a destroyed command ele-

ment, the Soviets first attempt to utilize the unit's

available assets. Should the battalion commander

&e incapacitated, he would normally be succeed-

ed by his chief of staff and the first MR company

commander (who is normally the senior company

commander), respectively. The battalion com-

mander may designate his political officer to be

his successor, since this man is well trained

militarily. The regimental commander may appoint

one of his staff officers to temporarily command

the battalion.

c. Staff

The battalion's chief of staff, the deputy com-

manders for political affairs and technical affairs,

and the heads of the various rear service elements

communicate with their counterparts at regiment,

thus relieving the battalion commander of many

administrative and supply details and allowing him

to concentrate on implementing regimental tac-

tical orders.

4. TRAFFIC REGULATORS

Extensive use of traffic regulators (figure 6) by

the Soviet ground forces is often interpreted as

indicating a weakness in mapreading skills.

Though mapreading seems to be a problem at the

lower levels due to a number of factors (see The

Soviet Motorized Rifle Company, DDI-1100-77-76,

October 1976, paragraphs 51-53), the extensive

use of traffic regulators may aid the achievement

of high rates of advance. Traffic regulators move

out with the advance guard battalion, and their

placement at key locations speeds up the move-

ment of Soviet columns by aiding commanders in

the control of their subordinate elements.

Because the Soviets move under virtual radio

silence during the march (preceding enemy con-

tact), traffic controllers are particularly useful.

They are also vulnerable. Moreover, if they are in-

capacitated, advancing columns may have dif-

ficulty.

£“Safi»k>’SSb

v '. - I

Figure6. Traffic Regulators Aid Commanders in Con-

trolling Their Units.

5. ATTACK TIME AND OBJECTIVES

In the Soviet Army the attack time (H-hour) is

the time the first man reaches the enemy FEBA,

whereas in most Western armies the attack time

refers to crossing the line of departure.

A unit is given intermediate and subsequent ob-

jectives and a direction for further attack. The

depths of these objectives depends upon METT

and whether or not nuclear weapons are used.

The unit's immediate objective includes the

enemy's forward positions; the subsequent objec-

tive, his reserves. The battalion's subsequent ob-

jective is included in the immediate objective of

the regiment; the subsequent objective of the

regiment is within the immediate objective of the

division, etc.

6. COMBINED ARMS OPERATIONS

Soviet emphasis on combined arms operations

has increased over the last 5 years. Motorized rifle

regiments and divisions and tank divisions are

units with an excellent mix of motorized rifle, ar-

tillery, tank, and engineer troops. Recently,

motorized rifle companies have been added to

tank regiments within tank divisions. These com-

panies may be the precursors of MR battalions

becoming organic to tank regiments. Combined

arms concepts and how they affect the MRB are

described below:

a. Tanks

A tank unit(s) is usually attached to or in sup-

port of a MRB. Normally, however, tanks are

placed in support, thus allowing the tank com-

mander to maintain control over his subunits.

Such an arrangement facilitates massing of pla-

toon and company fires on particular objectives.

When centralized control of tanks is not prac-

tical (for example, in combat in built-up areas and

in forests), however, tank platoons may be

decentralized and respond to MR company com-

manders.

b. Artillery

To achieve desired fire support in a

breakthrough, the Soviets form regimental, divi-

sional, and army artillery groupings (respectively

RAG, DAG, and AAG). An artillery grouping is

temporary in nature and consists of two or more

artillery battalions. When a RAG is formed it does

not include the MRR's organic artillery battalion.

The battalion is, however, normally placed in sup-

port of the MRR's subordinate motorized rifle bat-

talions. In some cases each of the artillery bat-

talion's batteries may be attached to a MRB. In

such cases, coordination of artillery fire is

accomplished by the artillery battery commander

(working with the MRB commander) under the

close supervision of the artillery battalion com-

mander (working with the MRR commander).

Artillery support for an offensive may be divid-

ed into three phases: preparatory fires (phase

one), fires in support of an attack (phase two),

and fires in support of operations within the

depths of the enemy's defenses (phase three).

The battalion commander's control over his

organic mortars and attached artillery varies with

each phase.

The MRB commander, though responsible for

the training and employment of his organic mor-

tar battery, does not always have control over

this unit. The regimental chief of artillery plans

and supervises the training of the mortar batteries

(as well as the regiment's antitank means) in the

regiment's subordinate battalions and supervises

execution of the fire plan by organic regimental

artillery, to include mortars (figure 7). Artillery fire

planning is centrally coordinated with flexibility

built in to allow for close support of maneuver

elements.

Figure 7. The Regimental Chief of Artillery (on the right)

Coordinates Regimental Artillery During Phase

One Fire.

During phase one, all artillery, including mor-

tars, and all weapons (tanks and antitank guns)

firing in the preparation, are centrally controlled

by means of a fire plan. During phase two, the

MRB's organic mortars are controlled by the

MRB. The attached artillery battery, while less

centralized, is responsive to requests for fires

from the MRB, while still being controlled by

higher headquarters. During phase three, attach-

ed artillery, with the senior commander's ap-

proval, could advance with the MRB to provide

close support. In the attack, the mortar battery

displaces according to the tactical situation (see

chapter 6 for details). Firing outside a maneuver

10

unit's boundaries is not permitted without ap-

proval from higher authority.

During training, when employed in an indirect

fire role, Soviet artillery (depending upon the type

of artillery being fired) will not fire within 300

meters of friendly troops mounted in APCs or

within 200 meters of friendly tanks. Artillery will

not fire within 400 meters of dismounted troops.

Artillery fired in the direct fire mode will fire much

closer. Peacetime fire restrictions would be con-

siderably reduced in wartime.

During the pursuit, attached artillery would

provide close support and on-call fires. Owing to

the speed of pursuit operations, a continuing bar-

rage of fire forward of the maneuver units is not

deemed practical.

c. Engineer

The proliferation, types, and quality of Soviet

engineer equipment complement their doctrine

stressing. high rates of advance. River-crossing

equipment, mineclearers, and minelayers are par-

ticularly impressive (see chapter 3).

There are two types of Soviet engineers: Sap-

per, or combat engineers found at regiment and

division, and more skilled engineers organized and

trained for specific missions. The latter type of

engineer is normally organic to army and front.

From his senior commanders, the MRB com-

mander receives engineer support to enable his

unit to cross natural and manmade obstacles, and

to construct defensive positions and barriers.

MRB troops are trained to perform some engineer

tasks such as building weapons emplacements

and trenches, emplacing and clearing mines by

hand, and camouflaging weapons and equipment.

d. Air Support

Direct air support to an MRB commander

would be a rarity, since the MR division com-

mander normally directs supporting air assets

through air liaison staffs. Forward air controllers

could, however, be assigned to a regiment attack-

ing on a division's main axis.

This is not to say that Soviet tactical air assets

would not be used to "prep" an area prior to an

MRB attack. For example, Soviet high- per-

formance aircraft (such as the FLOGGER series)

and or helicopter gunships often "prep" areas

prior to a river crossing, on the main axis of at-

tack, and in other selective operations (figure 8).

The MRB commander has no direct organic com-

munication with high-performance aircraft or at-

tack helicopters.

Figure 8. High Performance Aircraft in Support of the Main Attack.

11

Section С — Tactical Trends Since the October 1973 War

1. GENERAL

The October 1973 War had considerable impact

on the tactical doctrine of some Western coun-

tries, but did not cause any radical changes in

Soviet doctrine or tactics, in spite of a rigorous

examination of basic doctrinal principles. These

principles for the most part go back to World War

II, and remain the primary origin of current Soviet

doctrinal thinking. Soviet offensive doctrine, built

around the tank and envisioning high rates of ad-

vance, remains basically unchanged.

2. SOVIET ANALYSIS OF THE WAR

While impressed with the increased complexity

of modern defenses, the high expenditure of

munitions, and the lethality of antitank weaponry,

the Soviets were equally impressed by the

enhanced offensive capabilities presented by

mobile air defense systems and well-coordinated

combined arms operations built primarily around

the tank. It should be noted that in the 1973 war,

tank gunnery destroyed three to four times as

many tanks as did antitank missiles.

3. TRENDS SINCE THE WAR

Since October 1973, the Soviets have taken

numerous steps to increase the viability of their

tank forces and to allow for anticipated losses of

armored vehicles. They have increased the

numbers of tanks and artillery pieces (especially

self-propelled artillery! within the MRD, and are

stressing the use of combined arms units even

more than previously. Moreover, there are clear

indications that helicopters will be assigned a

greater role in offensive operations.

Nowhere are these trends more apparent than

in the operations of Soviet battalion and regimen-

tal combat groupings.

12

CHAPTER 3. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE DIVISION

AND MOTORIZED RIFLE REGIMENT

1. GENERAL

Although the MRB has considerable firepower,

it lacks sufficient organic combat and combat

support elements for many types of operations.

For this reason it usually operates as part of the

MRR. Since the MRB is normally reinforced or

supported by regiment, and sometimes by divi-

sion, the organizations and equipment of the

MRD and the MRR will be covered in this

chapter.

2. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE DIVISION

The MRD is a well-balanced unit possessing

sufficient combat, combat support, and combat

service support units to enable it to conduct a

variety of offensive and defensive operations

under conventional or nuclear conditions.

Although it normally operates as part of corps or

army, the MRD is fully capable of conducting in-

dependent operations. The MRD is organized as

shown in figure 9. The MRD's principal weapons

and equipment are shown in figures 10 and 11.

3. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE REGIMENT

Though capable of independent action, the

motorized rifle regiment normally operates as part

of a division. The division commander allocates

additional support to his regiments as required.

Regimental artillery, for example, may be reinforc-

ed with units from the division's artillery and

multiple rocket launcher battalions, forming a

regimental artillery grouping (RAG). The regimen-

tal commander requests nuclear fire support from

division.

The BMP-equipped MRR is organized as shown

in figure 12. Some of the regiment's principal

weapons and equipment are shown in figures 13

and 14.

*This unit I* only in a few MRDs.

Figure 9. The Motorized Rifle Division.

13

о. 76mm Divisional Gun, ZIS-3.

г

//>’

b. 100mm AT Gun, M-55/T-12.

c. 122mm Howitzer, M-1938/D-30.

FigurelO. The Motorized Rifle Division’s Principal Weapons.

14

d. 122mm Rocket Launcher BM-21.

e. 152mm Howitzer, D-l.

f. FROG TEL, FROG-7.

Figure 10. The Motorized Rifle Division’s Principal Weapons. (Continued)

A

15

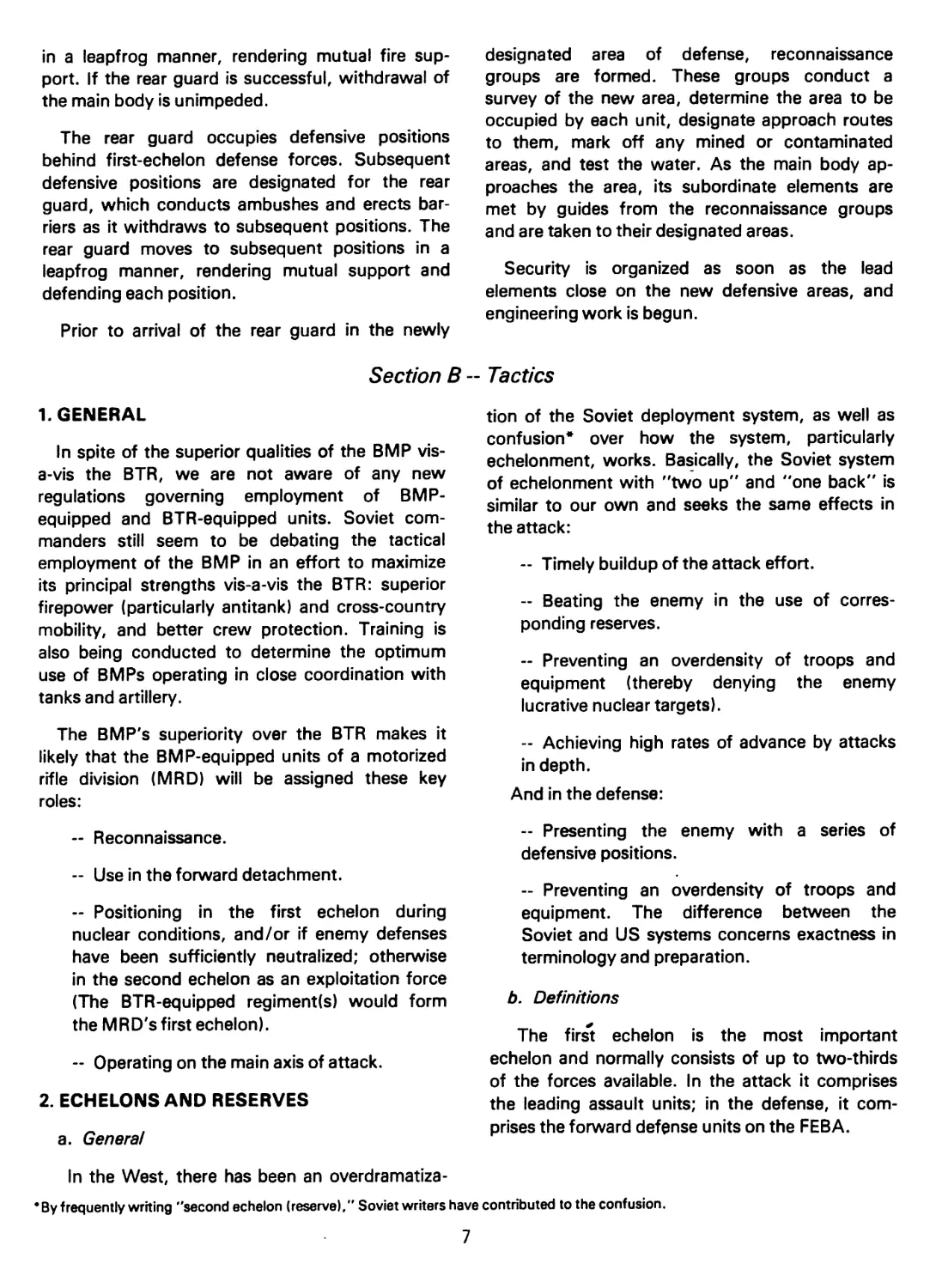

g. GAINFUL TEL. SA-6

Figure 10. The Motorized Rifle Division's Principal Weapons. (Continued)

c. Pontoon PMP on KRAZ.

Figure 11. The Motorized Rifle Division's Principal Equipment.

16

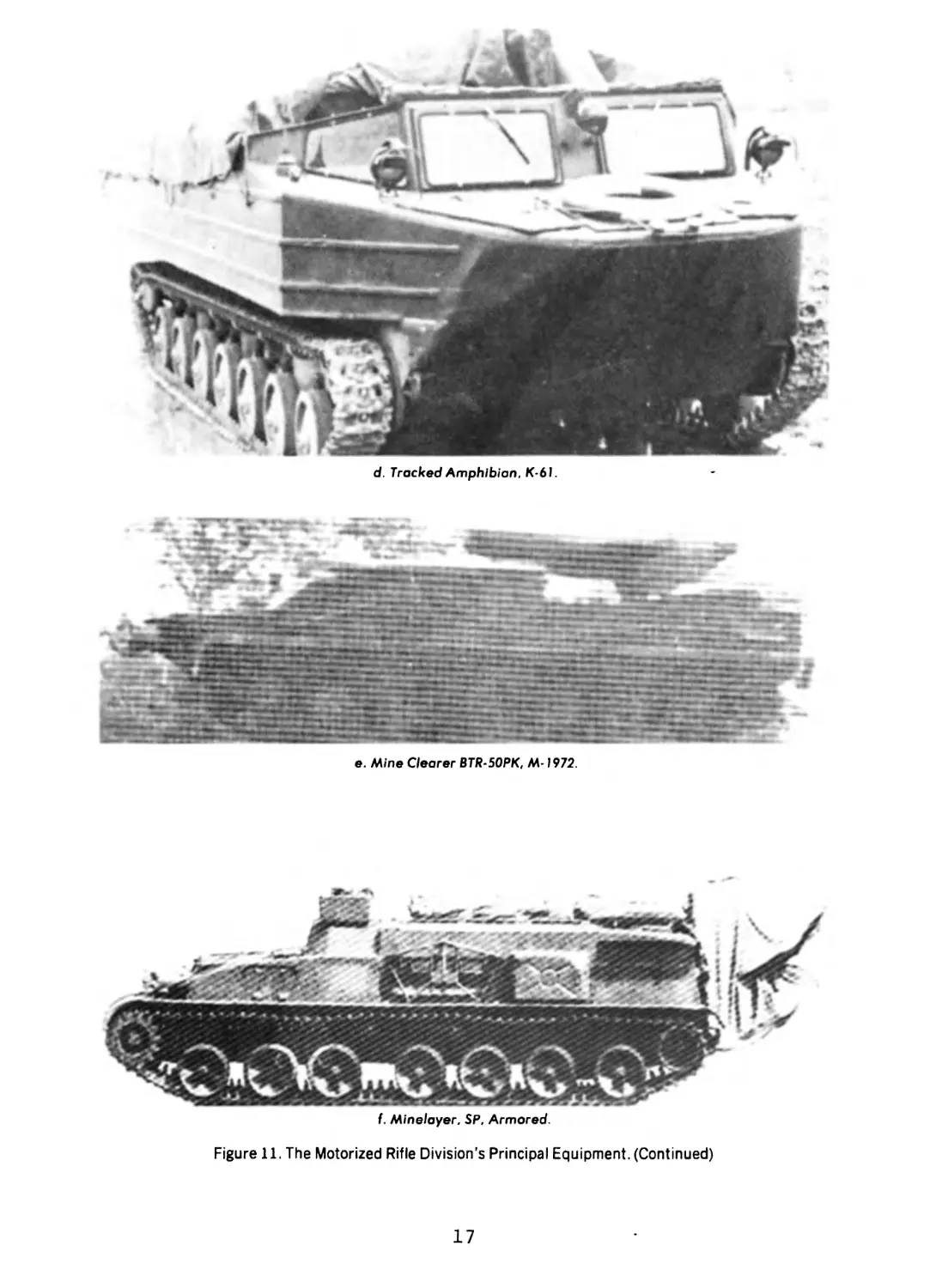

d. Tracked Amphibian. K-61.

e. Mine Clearer BTR-50PK, M-1972.

f. Minelayer, SP. Armored.

Figure 11. The Motorized Rifle Division’s Principal Equipment. (Continued)

17

g. Truck, Decon, TMS-65.

Figure 11. The Motorized Rifle Division’s Principal Equipment. (Continued)

Figure 12. The Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped)

18

a. Medium Tank, T-64 •

a. Medium Tank, T-72 *

Figure 13. Principal Weapons in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped).

19

c. 23mm SP AA Gun, ZSU-23-4.'

Figure 13. Principal Weapons in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

20

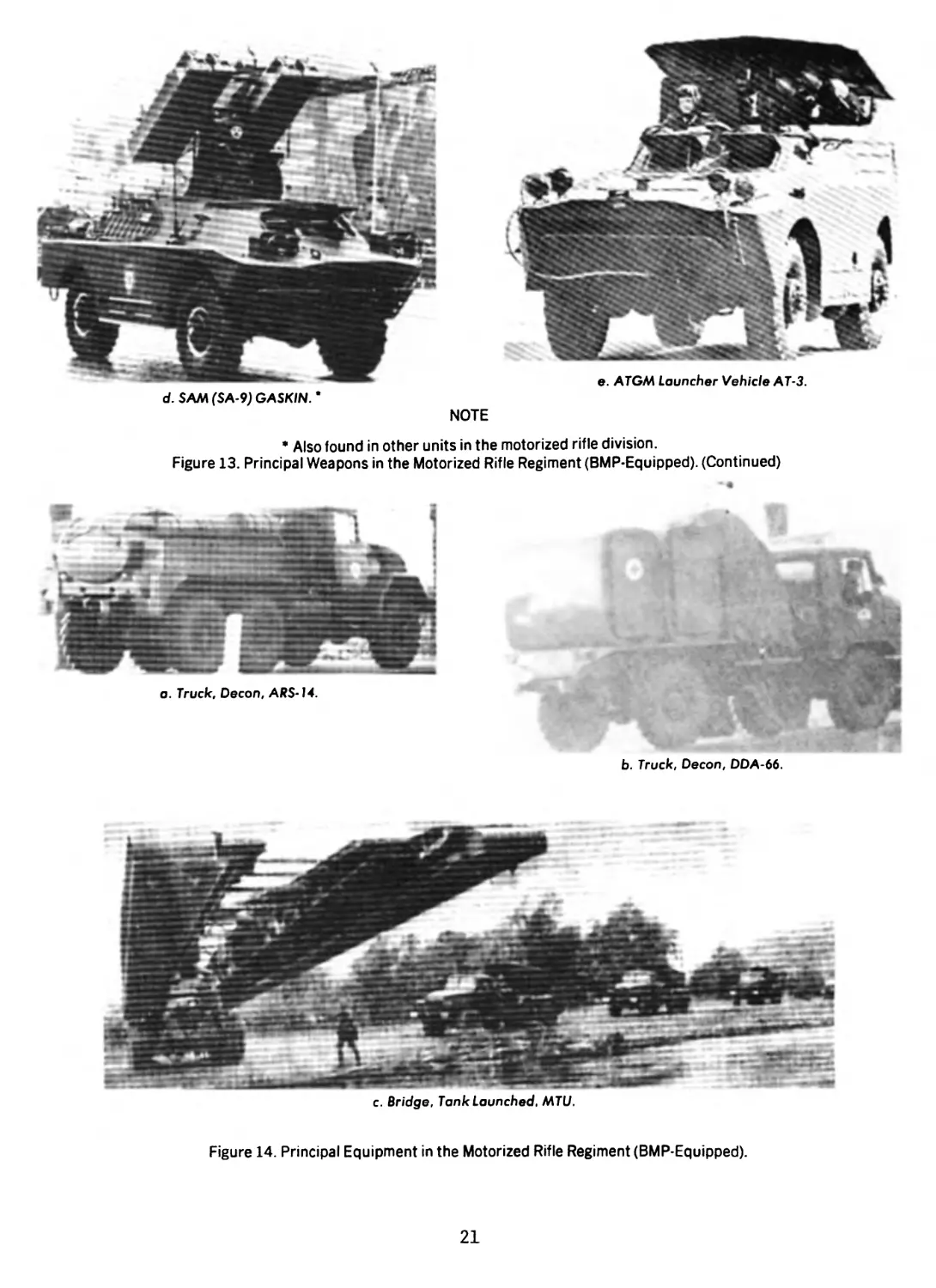

d. SAM (SA-9) GASKIN. *

NOTE

• Also found in other units in the motorized rifle division.

Figure 13. Principal Weapons in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

a. Truck, Decon, ARS-14.

b. Truck, Decon, DDA-66.

c. Bridge, Tank Launched, MTU.

Figure 14. Principal Equipment in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped).

21

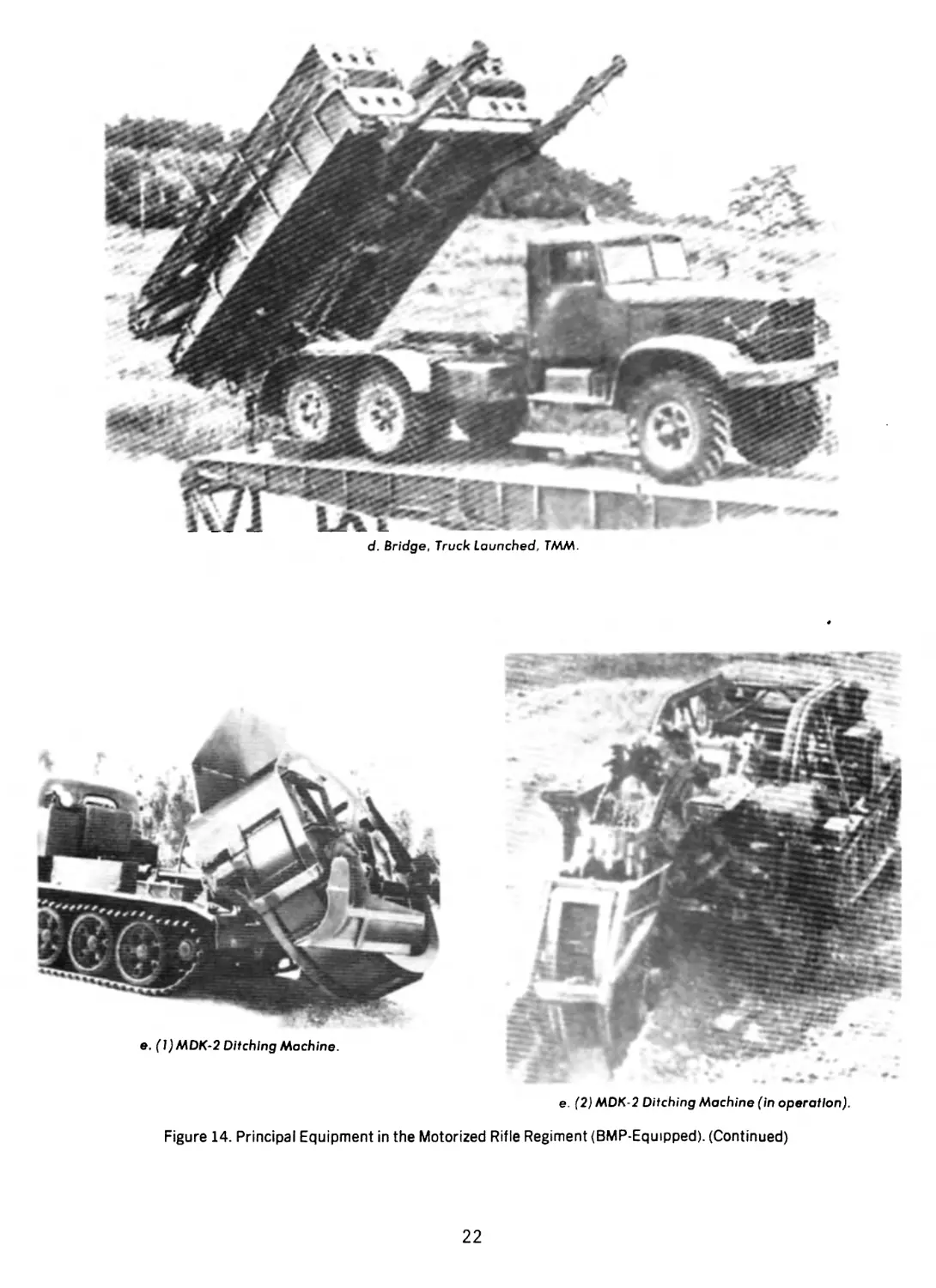

d. Bridge, Truck Launched, TMM.

e. (1) MDK-2 Ditching Machine.

e. (2) MDK-2 Ditching Machine (in operation).

Figure 14. Principal Equipment in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

22

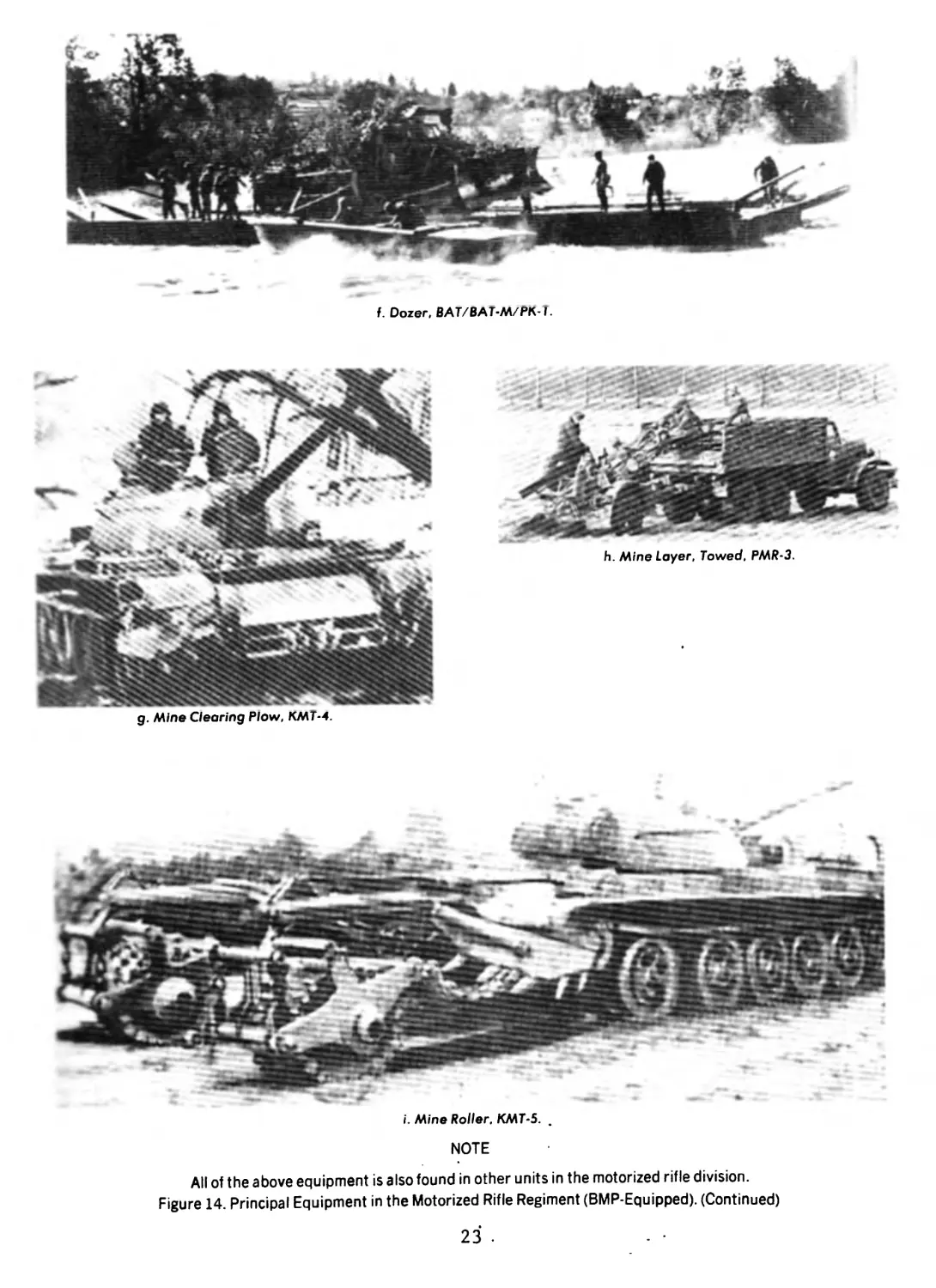

f. Dozer, BAT/BAT-M/PK-T.

g. Mine Clearing Plow, KMT-4.

i. Mine Roller. KMT-5. .

NOTE

All of the above equipment is also found in other units in the motorized rifle division.

Figure 14. Principal Equipment in the Motorized Rifle Regiment (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

23 .

CHAPTER 4. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION

Section A - Operational Principles and Missions

1. OPERATIONAL PRINCIPLES

Although it normally operates as part of the

regiment, the MRB may also be designated the

division reserve. In the latter role, the battalion

operates under the division commander. In addi-

tion to their normal operations, MRBs may also

participate in operations under special conditions

(see chapters).

Because it is relatively "light" in combat and

combat-support elements, the battalion is normal-

ly reinforced by regiment and/or division. This

augmentation may occur when the battalion acts

as a forward detachment, advance, flank, or rear

guard; when it attacks or defends in the first

echelon of the regiment; or when it conducts in-

dependent operations. For such operations, a

Soviet battalion commander could be allocated, in

addition to his own assets, one tank company* a

122mm howitzer battalion, an antitank guided

missile platoon, an antiaircraft missile and artillery

platoon, an engineer platoon, and a chemical pla-

toon.

2. MISSIONS

The mission of the MRB depends upon the role

it has been assigned within the regimental combat

formation. It may attack or defend as part of the

first echelon, be placed in the second echelon, be

designated as part of the division reserve, or be

assigned special missions. As part of the regi-

ment's first echelon in the attack, the battalion

would have the mission of penetrating enemy

defenses, neutralizing enemy troops and equip-

ment, and seizing and consolidating the enemy's

defensive positions. First-echelon battalions would

also take part in repelling enemy counterattacks

and pursuing a withdrawing enemy force. In the

defense, first-echelon battalions have the mission

of defeating or wearing down the enemy's initial

assault elements.

A second-echelon battalion may be given any

of the following missions:

- Assuming the mission of severely attrited

first-echelon units.

- Exploiting the success of the first echelon.

- Eliminating bypassed pockets of enemy

resistance.

- Counterattacking.

- Destroying enemy forces on the flanks and

in the intervals between axes of attack and in

the rear of attacking troops.

- Attacking in a new direction.

As a division reserve, the MRB would be given

no mission prior to combat, but would be

prepared to execute a number of contingencies:

- Repulsing enemy counterattacks.

— Combatting airborne landings.

- Replacing weakened first-echelon units

(rarely done).

- Intensifying the attack effort.

— Exploiting success.

The MRB may also be assigned a number of

special missions: forward detachment or recon-

naissance element (the MRB would be the basis

for a reconnaissance group) for division, advance

guard of the regiment, and flank or rear security

guard for the division (see chapter 7, section A,

paragraph 4 for further details). It may also be

given a variety of missions in heliborne operations

and, on occasion, in ship-to-shore operations.

•As part of the regiment's first echelon in a breakthrough operation, the MRB commander may be given more tank support.

25

Section В - Organization, Responsibilities, and Equipment

1. THE MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION

The organization and principal weapons and

equipment of the BMP-equipped MRB are shown

in figures 15 and 16. For a detailed list and photos

of weapons and equipment at company level, see

The Soviet Motorized Rifle Company,

DDI-11Q0-77-76.

NOTES

1. The battalion communications officer is a member of the battalion staff and the communications platoon leader.

2. The supply platoon loader, usually a Pnponhchik. Is also a member of the battalion staff.

3. The weapons and equipment of each subordinate sub-unit are listed in the appropriate paragraph

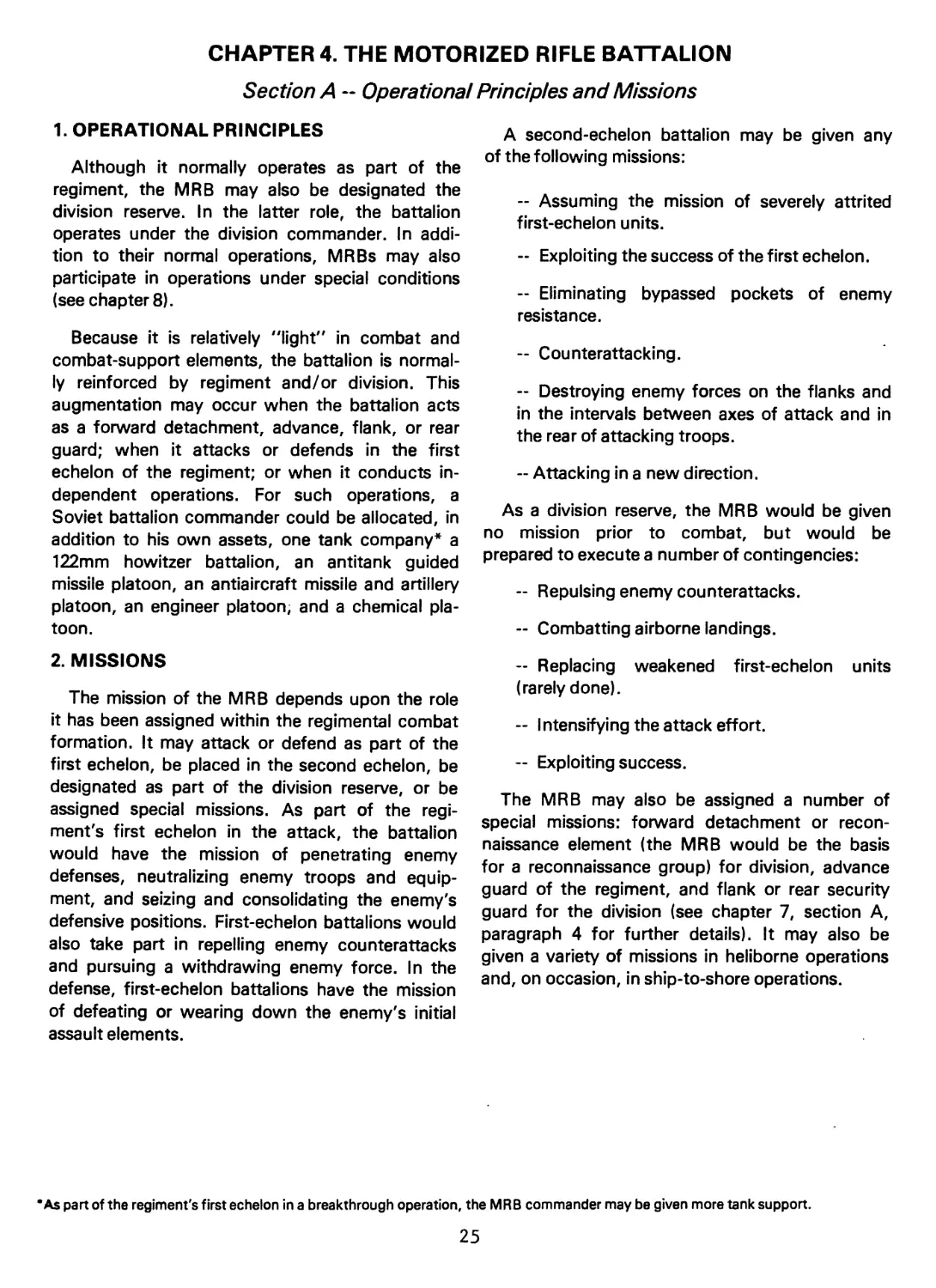

Figure 15. The Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped)

o. 120mm Mortar.

Figure 16. Principal Weapons and Equipment of the Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped).

26

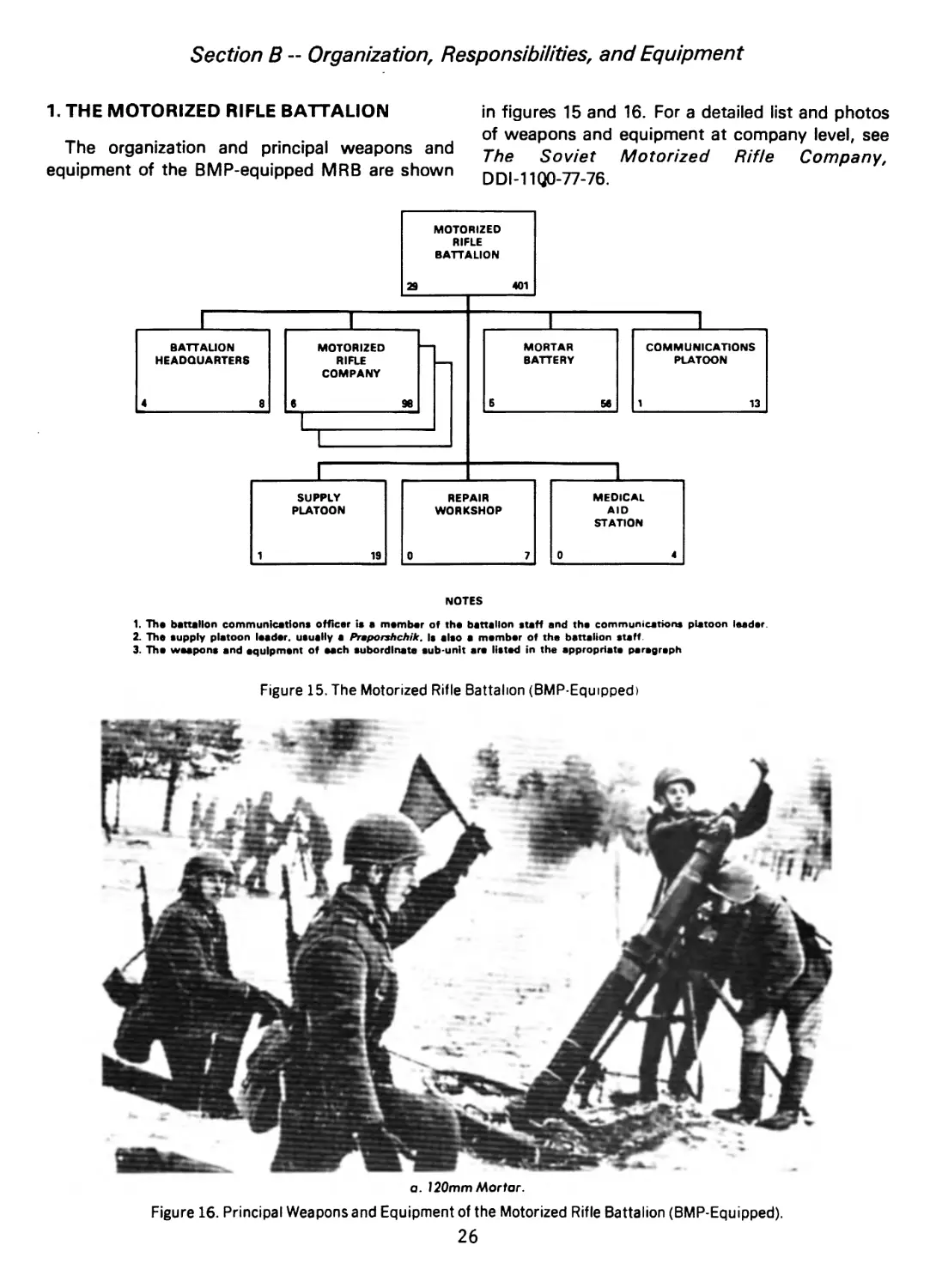

b. BMP.

с. Truck. UAZ-69.

Figure 16. Principal Weapons and Equipment of the Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

27

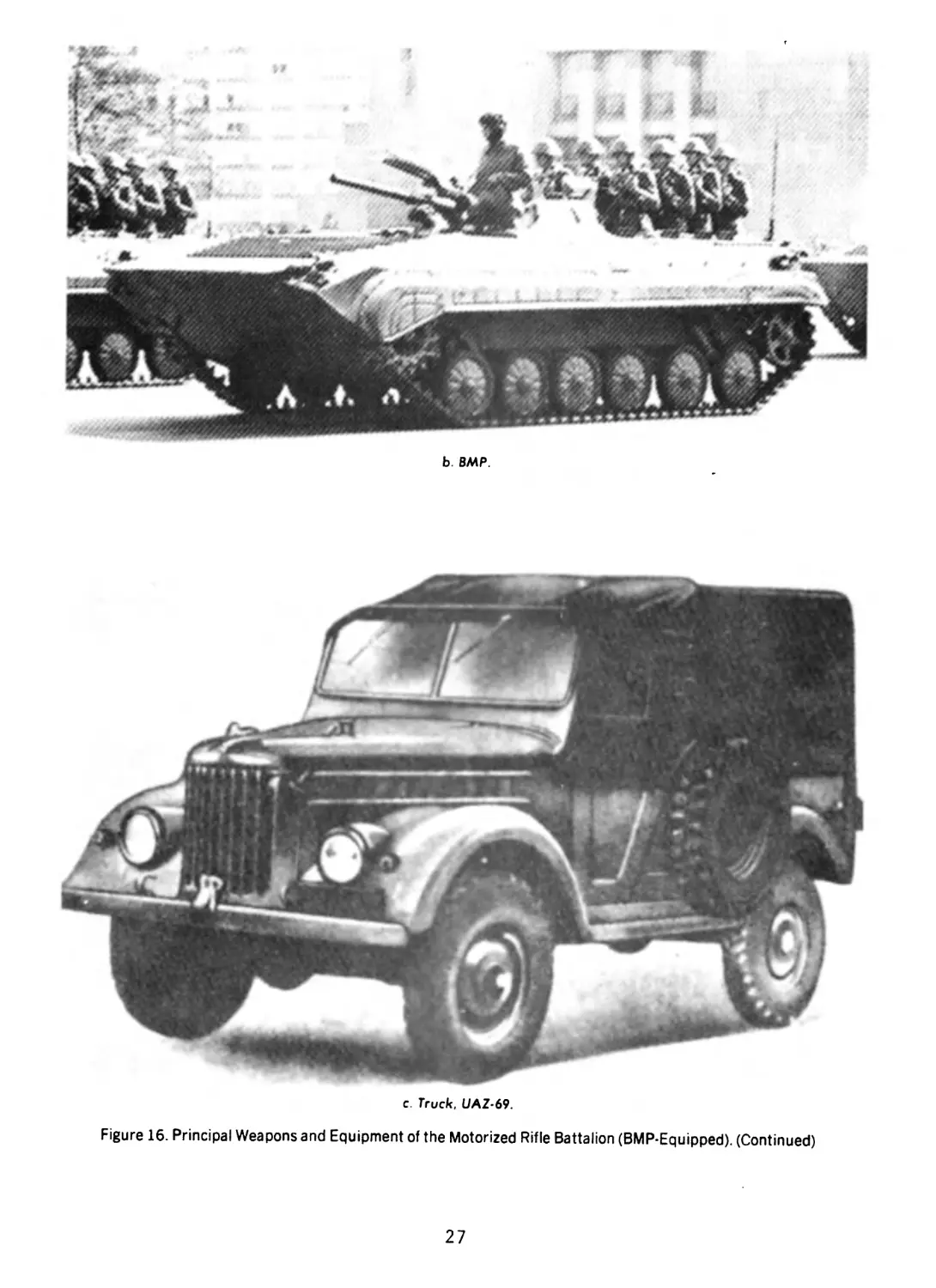

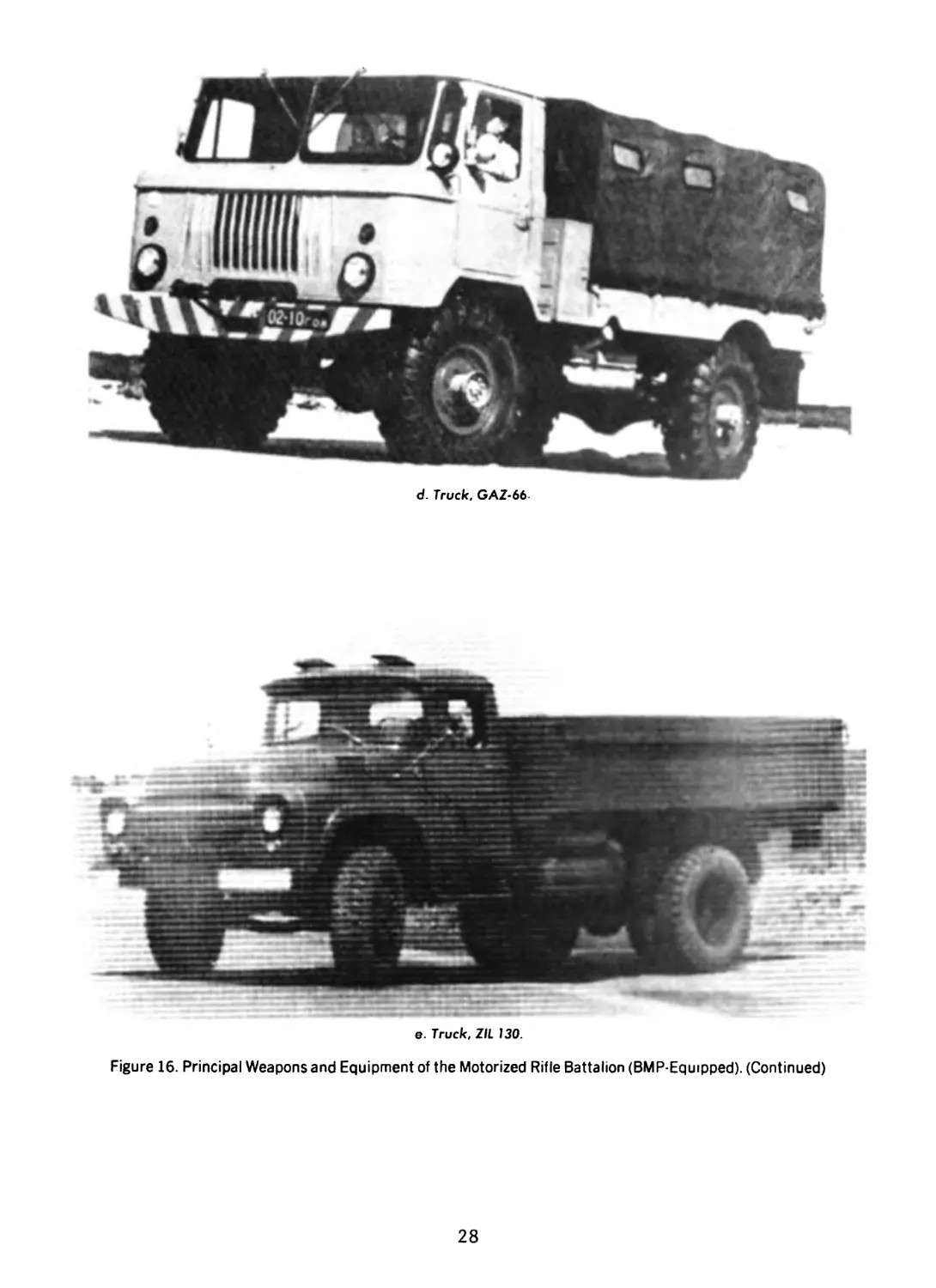

d. Truck. GAZ-66

e. Truck, ZIL 130.

Figure 16. Principal Weapons and Equipment of the Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

28

f. Truck, Van, ZIL (Maintenance).

g. Truck, POL (4,000 or 5,200 Liters).

h. Trucks, Field Kitchen, Van PAK-200.

Figure 16. Principal Weapons and Equipment of the Motorized Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

29

i. Ambulance, UAZ-450.

j. Trailer-Mounted Field Kitchen, KP-125.

Figure 16. Principal Weaponsand Equipment of the Motorized

Rifle Battalion (BMP-Equipped). (Continued)

2. SUBORDINATE ELEMENTS

a. The Battalion Headquarters

The battalion staff consists of six officers and

eight enlisted men (figure 17). Officer personnel

include the battalion commander, the battalion

chief of staff, the deputy battalion commander for

political affairs, the deputy battalion commander

for technical affairs, the battalion communications

officer (who is also the communications platoon

leader, and the supply platoon leader (a prapor-

shchik -roughly equivalent to warrant officer).

BATTAUON

HEADQUARTERS

4 8

WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT

9mm pistol, PM 4

7.62mm rifle. AKM 8

Armored personnel carrier

BMP-A......................................................... 1

ACV, BRDM/BTR-60/BMP 1

General purpose trucks

UA2 69/469 1

Truck. GAZ-66 1

Radios:

R-104m 2

R-106/107/147 2

R-123 2

R-126 _______________________________________________________— 1

R-311 1

NOTES

1. The communications platoon leader is also the battalion communi-

cations officer and is not reflected in the figure above.

2. The Praporshchik in charge of the supply platoon and the fald'scher

are also part of the battaRon staff, but are not listed above in order

to avoid confusion.

Figure 17. Battalion Headquarters.

(1) The battalion commander is responsible

for his unit's mobilization readiness, combat and

political training, education, military discipline,

and morale. He is also responsible for the unit's

equipment and facilities.

(2) The battalion chief of staff is the com-

mander's 'Tight arm." He has the authority to

give orders to all subordinate elements and in-

sures compliance with orders from the battalion

commander and higher commanders. The chief of

staff draws up the combat and training plans

(based upon the regimental plan and the battalion

commander's guidance) for the unit and insures

that they are carried out. He also insures that re-

quired reports are prepared and dispatched on

time to regimental headquarters. He is principal

organizer of rear service support for the battalion.

(3) The deputy battalion commander for

political affairs organizes and conducts political

training designed to rally the battalion's personnel

around the Communist Party and the Soviet

Government. He reports through the battalion

commander to the regimental political officer.

30

(4) The deputy battalion commander for

technical affairs supervises the battalion's

maintenance service element and reports directly

to the battalion commander or chief of staff. The

technical affairs officer is responsible for the com-

bat, political, and specialized training of rear ser-

vices personnel, and for the technical condition of

their equipment.

(5) The communications officer is a battalion

staff officer and the communications platoon

leader. It is his responsibility to train battalion per-

sonnel in signal procedures and to supervise com-

munications training of the battalion, to include

the conduct of classes for radio operators and

periodic inspections of communications equip-

ment. In combat, the battalion signal officer

receives instructions from the senior regimental

signal officer, as well as from the battalion com-

mander and chief of staff.

(6) The supply platoon leader may be a

praporshchik or senior NCO. He works closely

with the battalion chief of staff on all aspects of

battalion supply.

(7) Enlisted personnel in the battalion head-

quarters include a sergeant major and his driver, a

chemical instructor/dosimeter operator, a senior

medic (the feld'sher, who heads the medical sec-

tion, is a medical assistant whose skills fall

somewhere between those of a nurse and a

physician), two clerks, a driver and gunner for the

battalion commander's BMP, and a driver for the

chief of staff's APC.

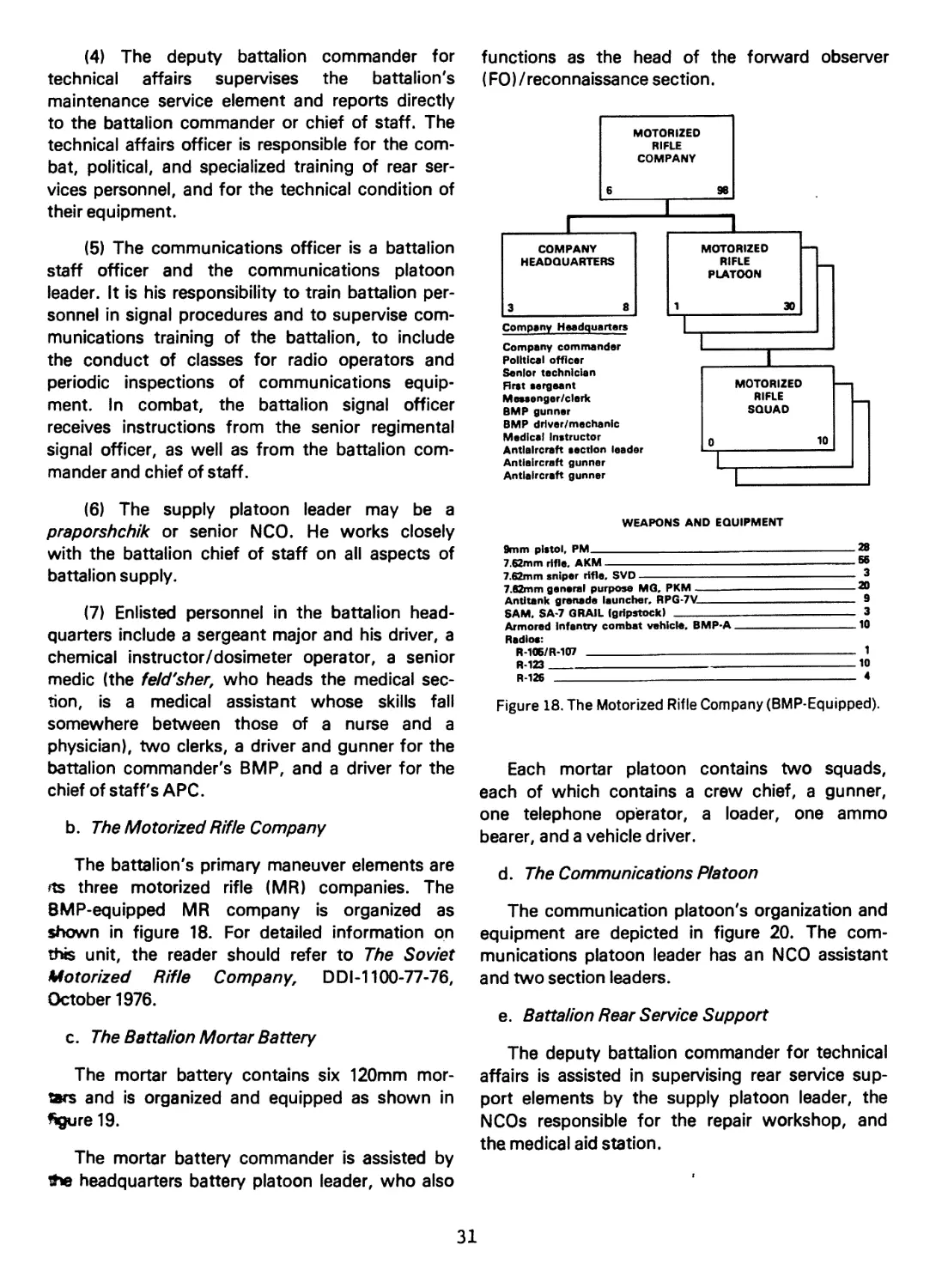

b. The Motorized Rifle Company

The battalion's primary maneuver elements are

fts three motorized rifle (MR) companies. The

BMP-equipped MR company is organized as

shown in figure 18. For detailed information on

this unit, the reader should refer to The Soviet

Motorized Rifle Company, DDI-1100-77-76,

October 1976.

c. The Battalion Mortar Battery

The mortar battery contains six 120mm mor-

tars and is organized and equipped as shown in

figure 19.

The mortar battery commander is assisted by

the headquarters battery platoon leader, who also

functions as the head of the forward observer

(FO) /reconnaissance section.

WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT

9mm pistol, PM 28

7.62mm rifle. AKM-----------------------------------------— 56

7.62mm sniper rifle, SVD------------------------------------ 3

7.62mm general purpose MG, PKM ------------------------------20

Antitank grenade launcher, RPG-7V--------------------—— 9

SAM. SA-7 GRAIL (gripstock) --------------------------------- 3

Armored Infantry combat vehicle, В MP-A----------------------10

Radios:

R-106/R-107 1

R-123____________________________________________________Ю

R -126 -----------------------—-------------------------- <

Figure 18. The Motorized Rifle Company (BMP-Equipped).

Each mortar platoon contains two squads,

each of which contains a crew chief, a gunner,

one telephone operator, a loader, one ammo

bearer, and a vehicle driver.

d. The Communications Platoon

The communication platoon's organization and

equipment are depicted in figure 20. The com-

munications platoon leader has an NCO assistant

and two section leaders.

e. Battalion Rear Service Support

The deputy battalion commander for technical

affairs is assisted in supervising rear service sup-

port elements by the supply platoon leader, the

NCOs responsible for the repair workshop, and

the medical aid station.

31

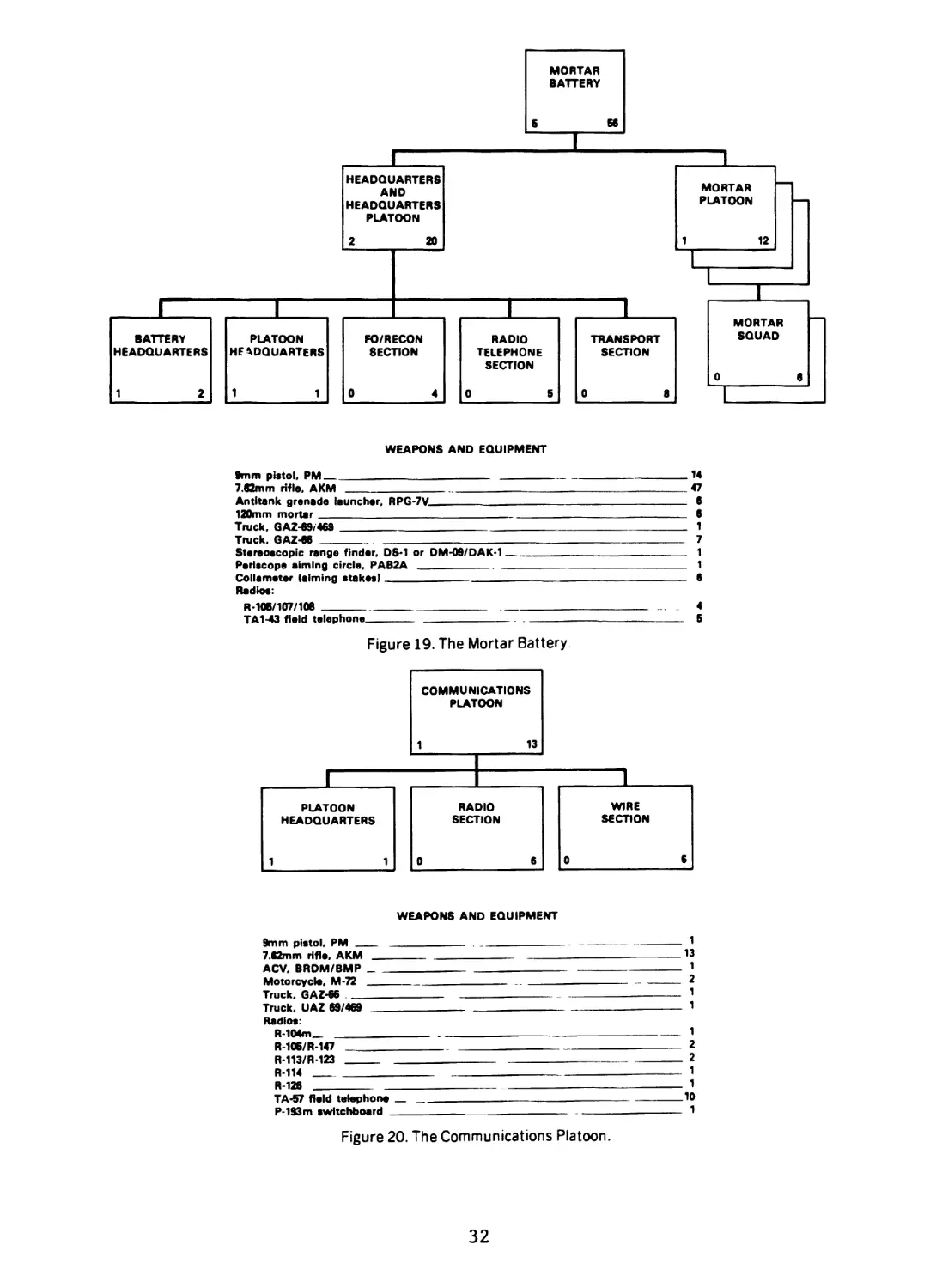

WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT

•mm pistol. PM___________________________________14

7.62mm rifle. AKM<7

Antitank grenade launcher. RPG-7V_________________6

120mm mortar 6

Truck. GAZ-69/469 1

Truck. GAZ-66 7

Stereoscopic range finder, DS-1 or DM-09/DAK-1--- 1

Periscope aiming circle, PAB2A 1

CoIla meter (aiming stakes)6

Radios:

R-106/107/106 ___________________________________ 4

TA1-43 field telephone--------------------------- 5

Figure 19. The Mortar Battery

WEAPONS AND EQUIPMENT

9mm pistol, PM ___________

7.62mm rifle. AKM 13

ACV, BRDM/BMP 1

Motorcycle. M-72 2

Truck. GAZ-66 1

Truck. UAZ 69/469 1

Radios:

R-104m_1

R-106/R-147 2

R-113/R-123 --------------------------- 2

R-114 1

R -126 1

TA-57 field telephone Ю

P-193m switchboard 1

Figure 20. The Communications Platoon.

32

Section С - Command and Control

1. COMMAND

The Soviets regard command as the exercise of

constant and effective control. The battalion com-

mander relies primarily upon his chief of staff, but

is reluctant to delegate authority, preferring to

make most decisions himself. Company com-

manders and the commanders of other organic

and attached units are closely supervised by the

battalion commander and/or the chief of staff.

2. CONTROL

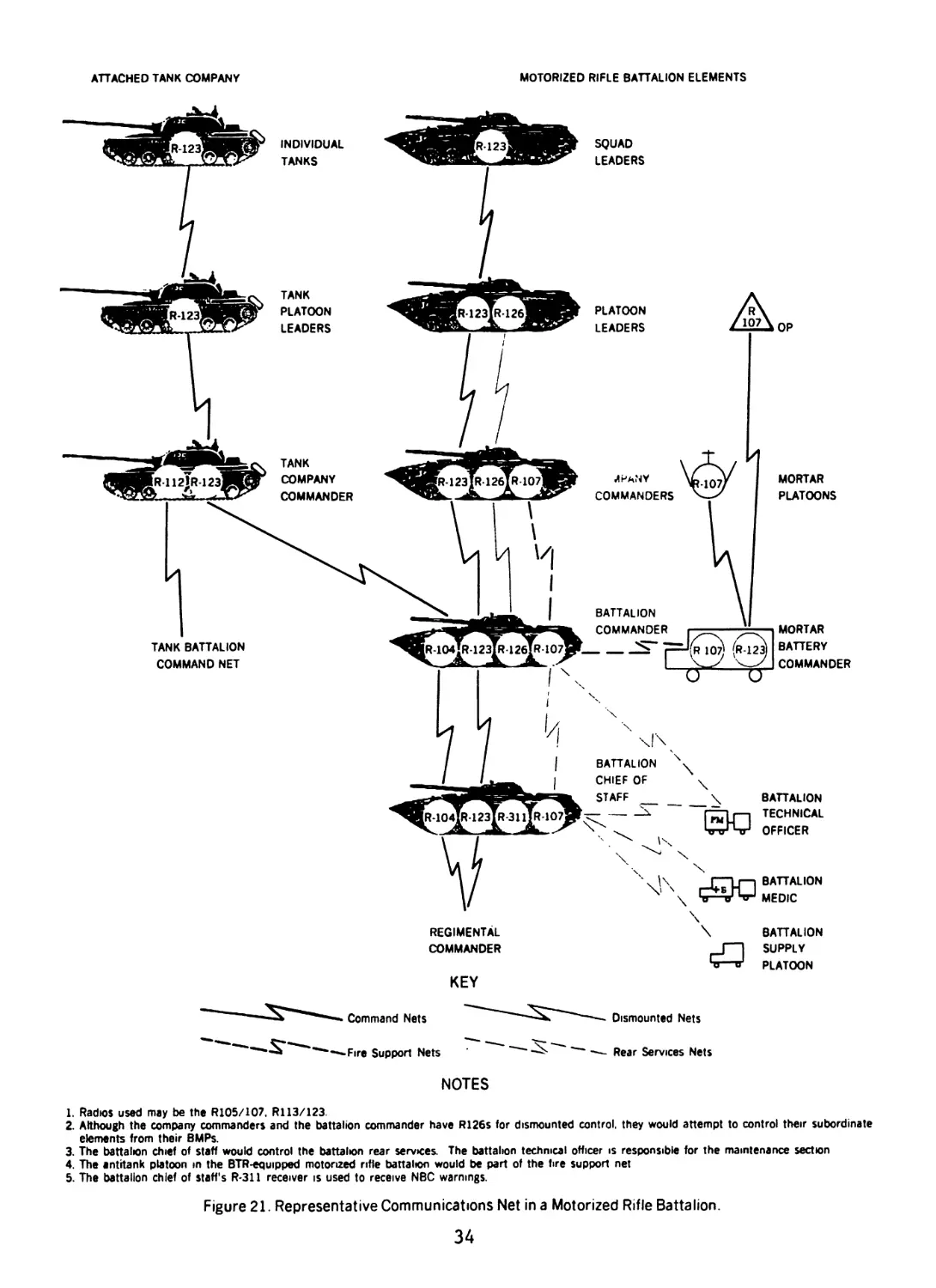

In the offensive, the primary means of control

of the MRB is radio, although messengers, per-

sonal contact between commanders, signal flares,

flags, and a variety of other methods are also

used. Prior to contact, radio silence is strictly

observed, excepting reports from reconnaissance

elements and the crossing of phase lines. A type

of battalion radio net is shown in figure 21.

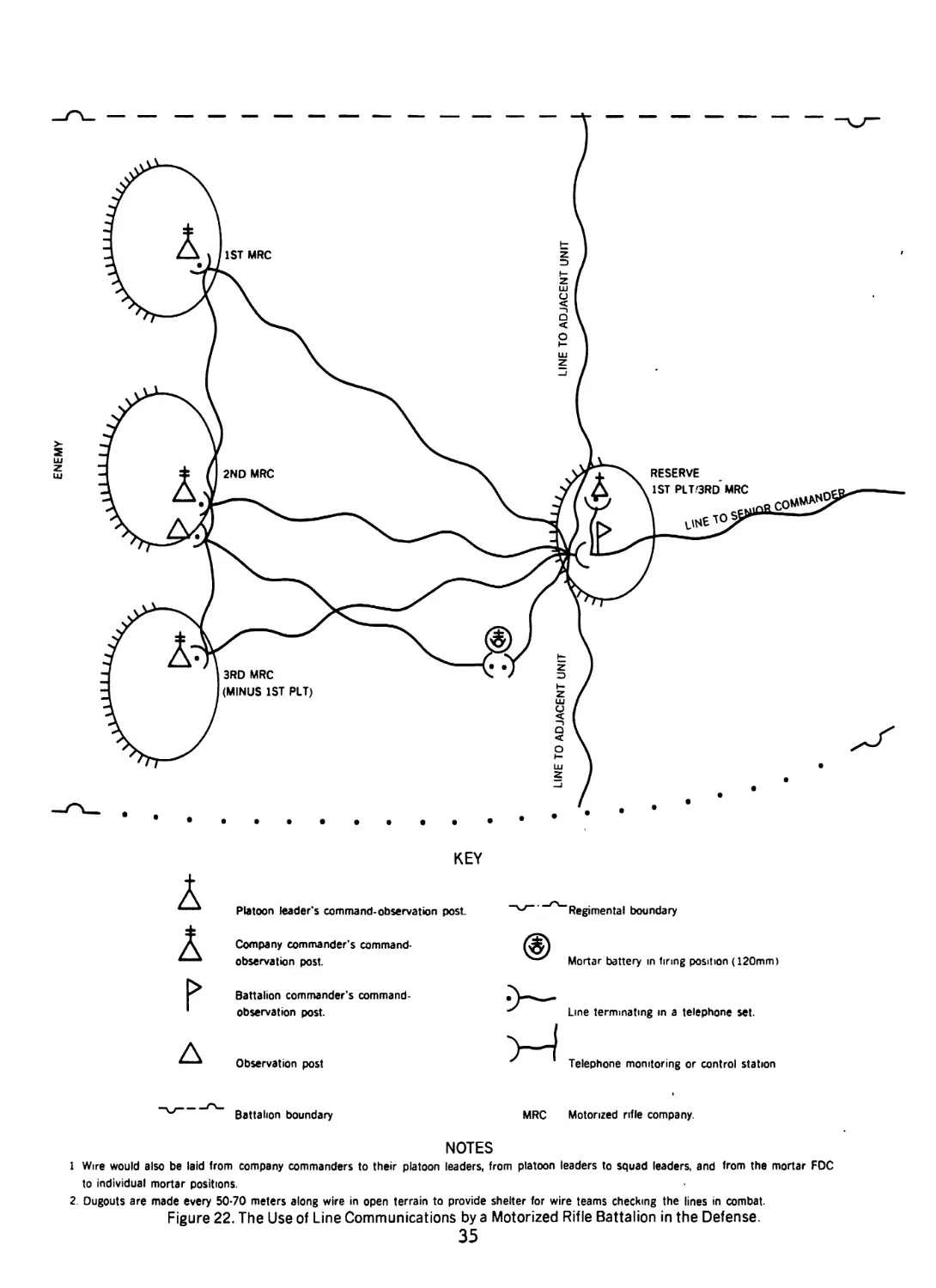

In the defense, the battalion relies primarily on

wire, although messengers, signal flares, and

radios are also used extensively. A battalion in the

defense would employ a wire system as shown in

figure 22.

33

ATTACHED TANK COMPANY

MOTORIZED RIFLE BATTALION ELEMENTS

REGIMENTAL

\ BATTALION

COMMANDER

SUPPLY

PLATOON

KEY

Command Nets

Dismounted Nets

Fire Support Nets

Rear Services Nets

NOTES

1. Radios used may be the R1O5/1O7, R113/123.

2. Although the company commanders and the battalion commander have R126s for dismounted control, they would attempt to control their subordinate

elements from their BMPs.

3. The battalion chief of staff would control the battalion rear services. The battalion technical officer is responsible for the maintenance section

4. The antitank platoon in the BTR>equipped motorized rifle battalion would be part of the fire support net

5. The battalion chief of staff's R-311 receiver is used to receive NBC warnings.

Figure 21. Representative Communications Net in a Motorized Rifle Battalion.

34

ENEMY

Observation post

Telephone monitoring or control station

Battalion boundary

MRC

Motorized rifle company.

NOTES

1 Wire would also be laid from company commanders to their platoon leaders, from platoon leaders to squad leaders, and from the mortar FDC

to individual mortar positions.

2 . Dugouts are made every 50-70 meters along wire in open terrain to provide shelter for wire teams checking the lines in combat.

Figure 22. The Use of Line Communications by a Motorized Rifle Battalion in the Defense.

35

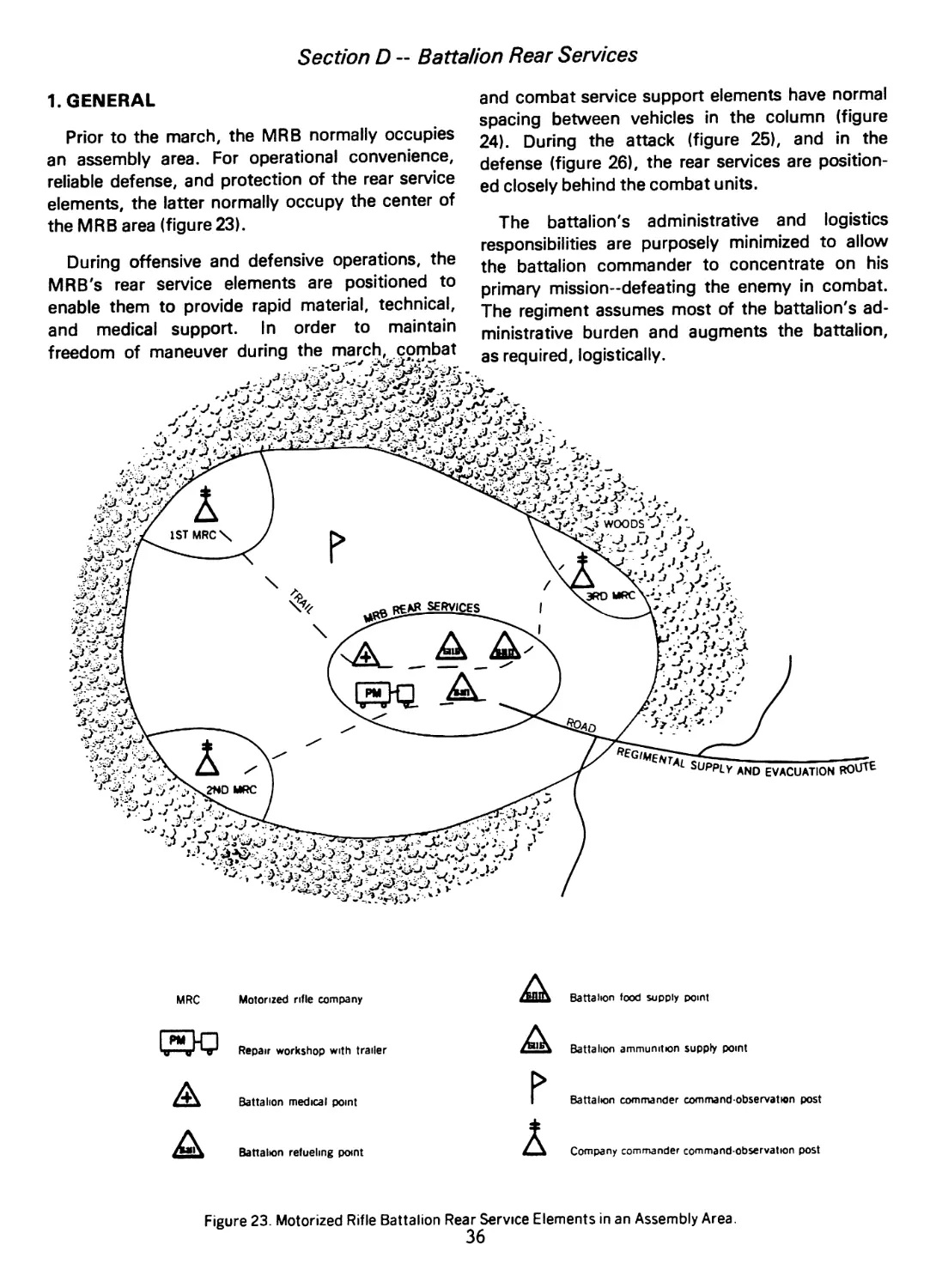

Section D - Battalion Rear Services

1. GENERAL

Prior to the march, the MRB normally occupies

an assembly area. For operational convenience,

reliable defense, and protection of the rear service

elements, the latter normally occupy the center of

the MRB area (figure23).

During offensive and defensive operations, the

MRB's rear service elements are positioned to

enable them to provide rapid material, technical,

and medical support. In order to maintain

freedom of maneuver during the march^ combat

1ST MRC\

3RD MRC

2ND MRC

Battalion food supply point

Repair workshop with trailer

Battalion ammunition supply point

Battalion medical point

Battalion commander com ma nd-observation post

Battalion refueling point

Company commander command-observation post

Figure 23. Motorized Rifle Battalion Rear Service Elements in an Assembly Area.

36

MRC Motorized rifle company

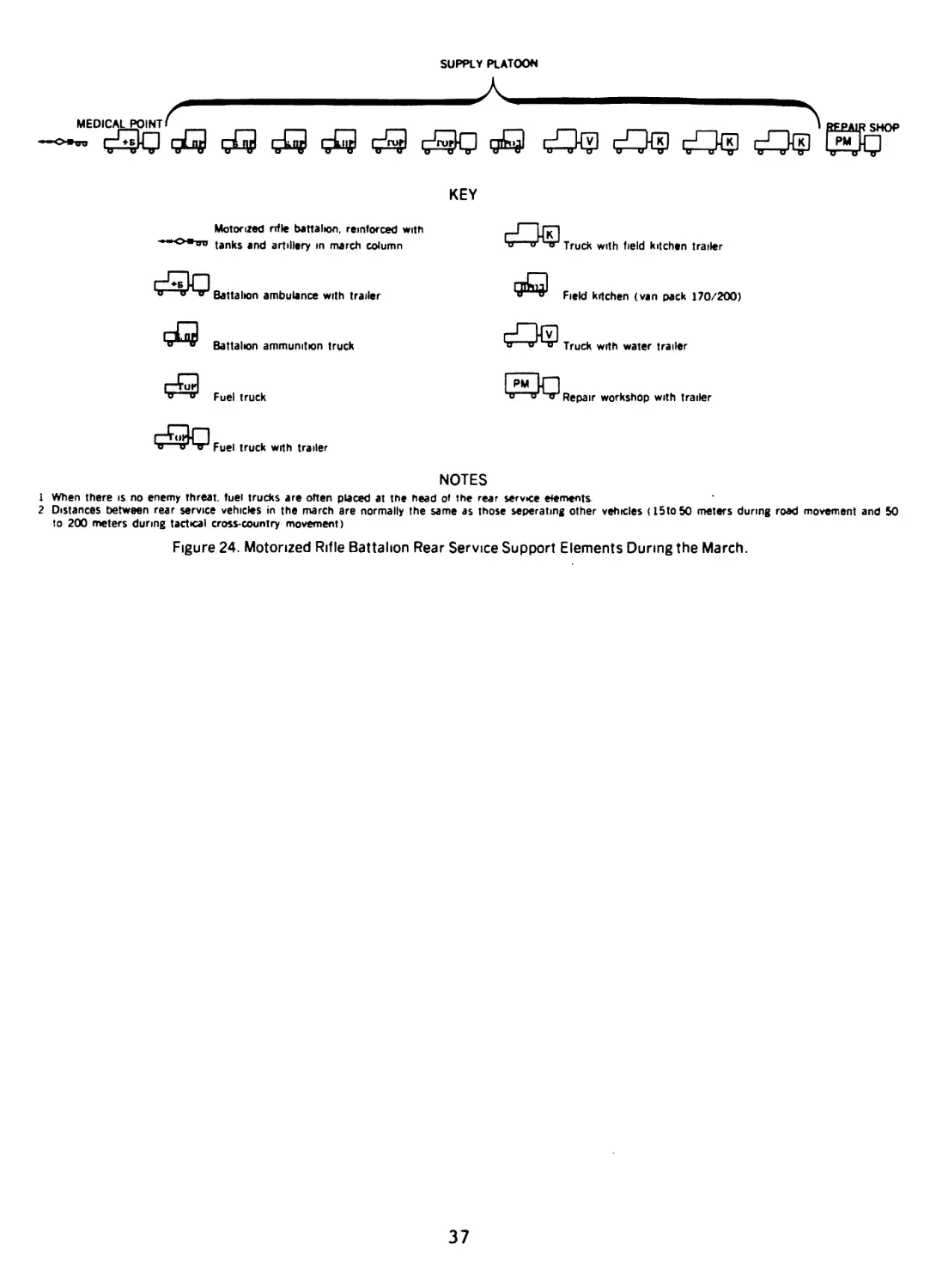

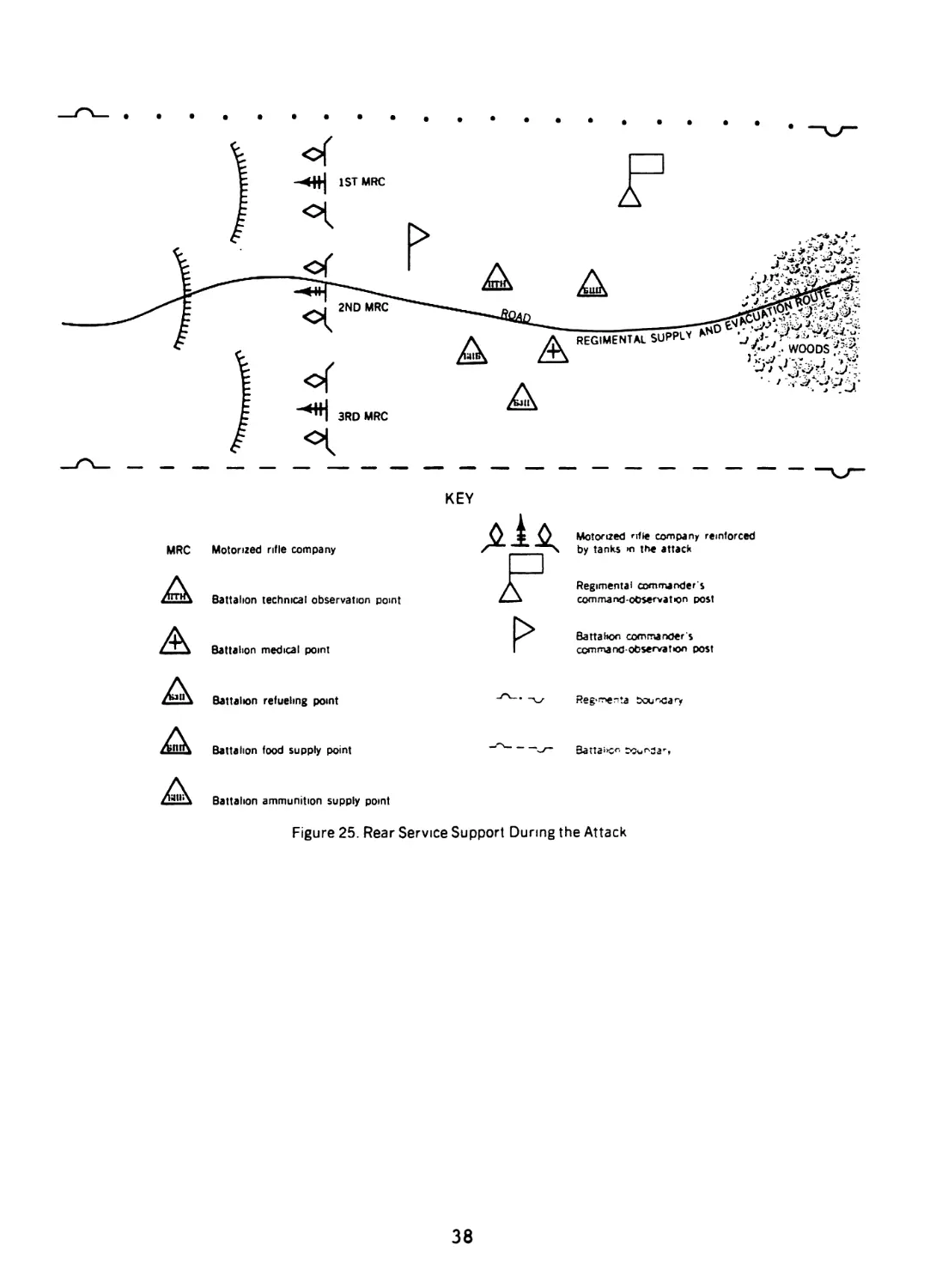

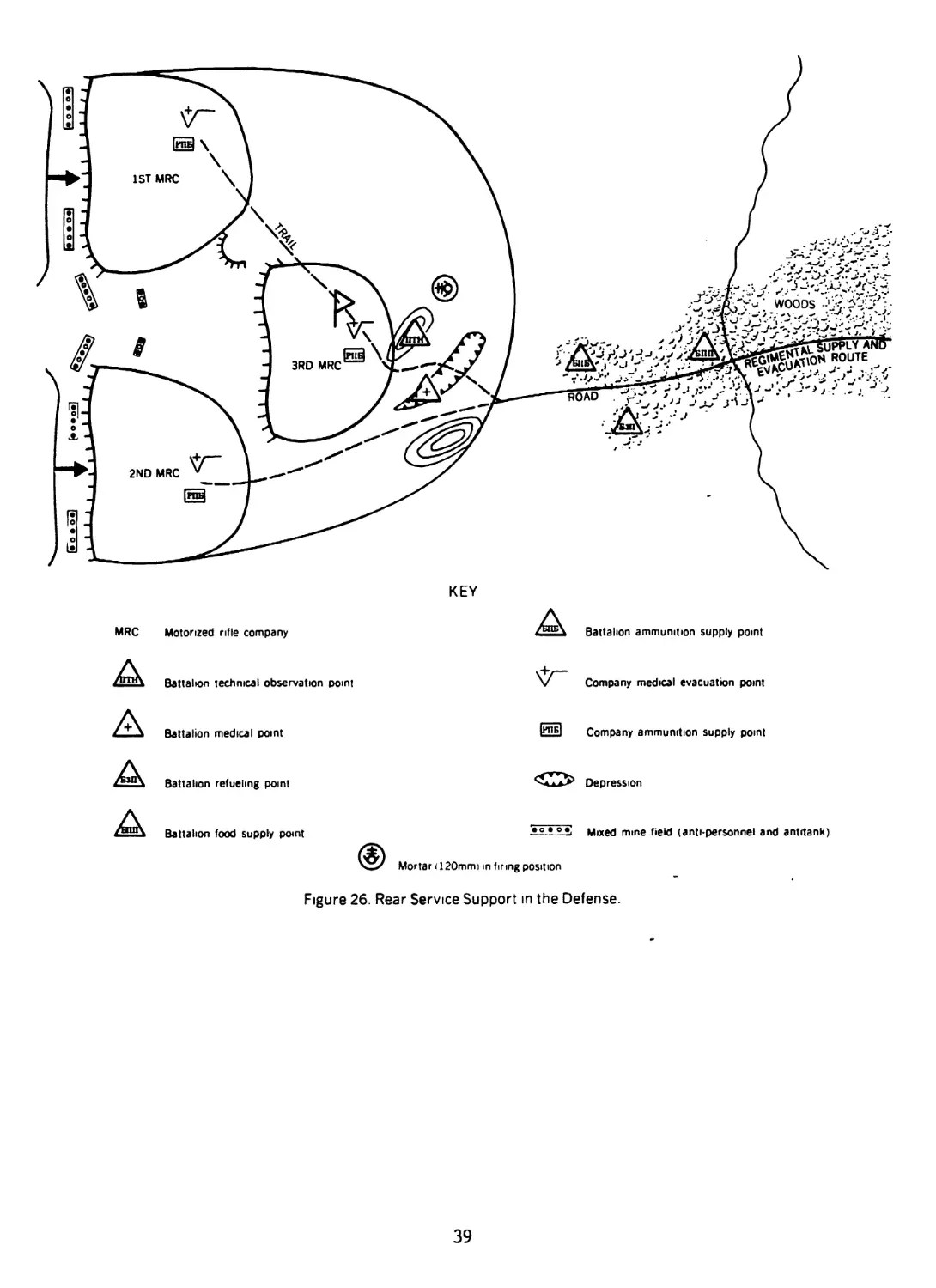

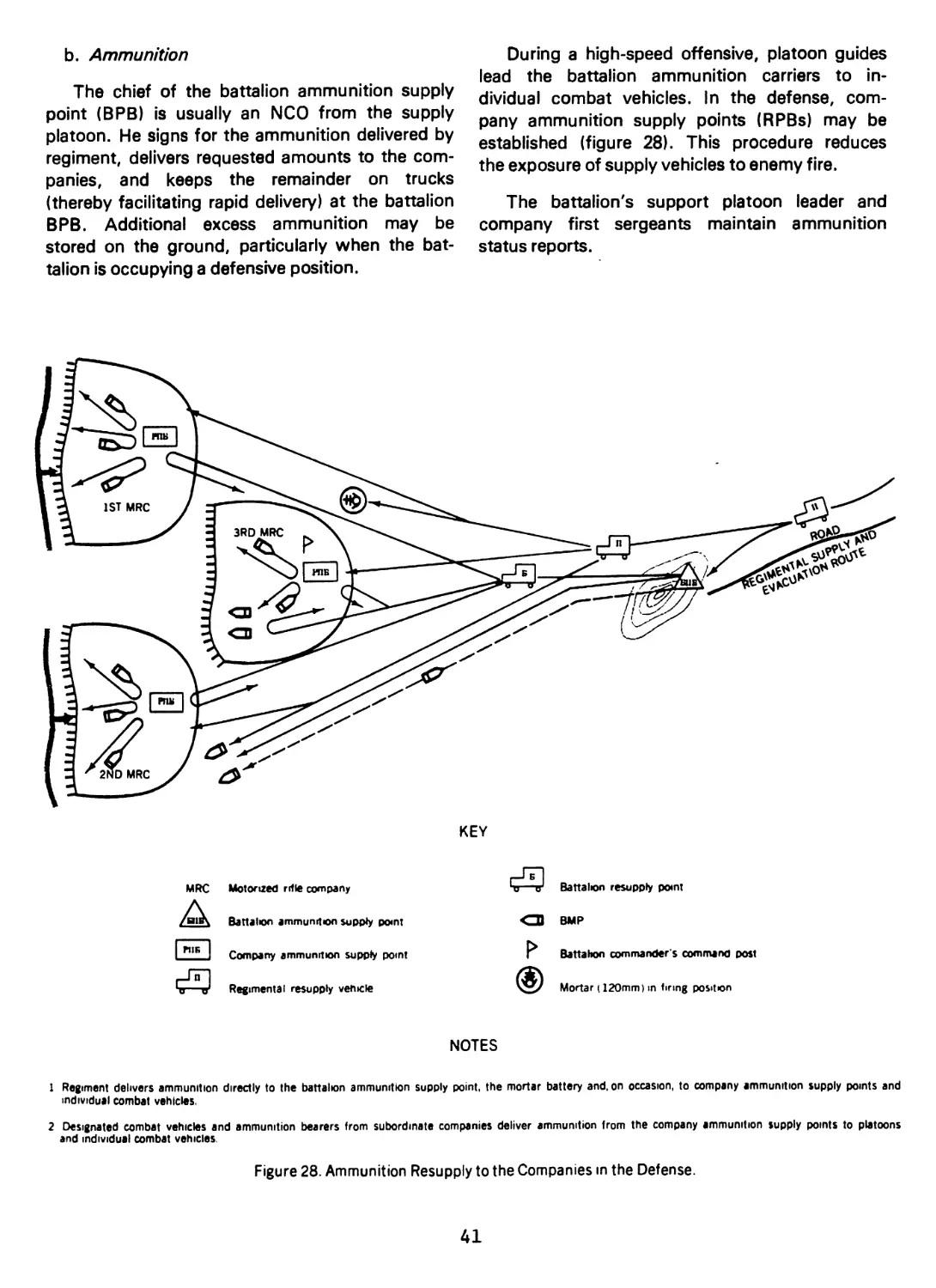

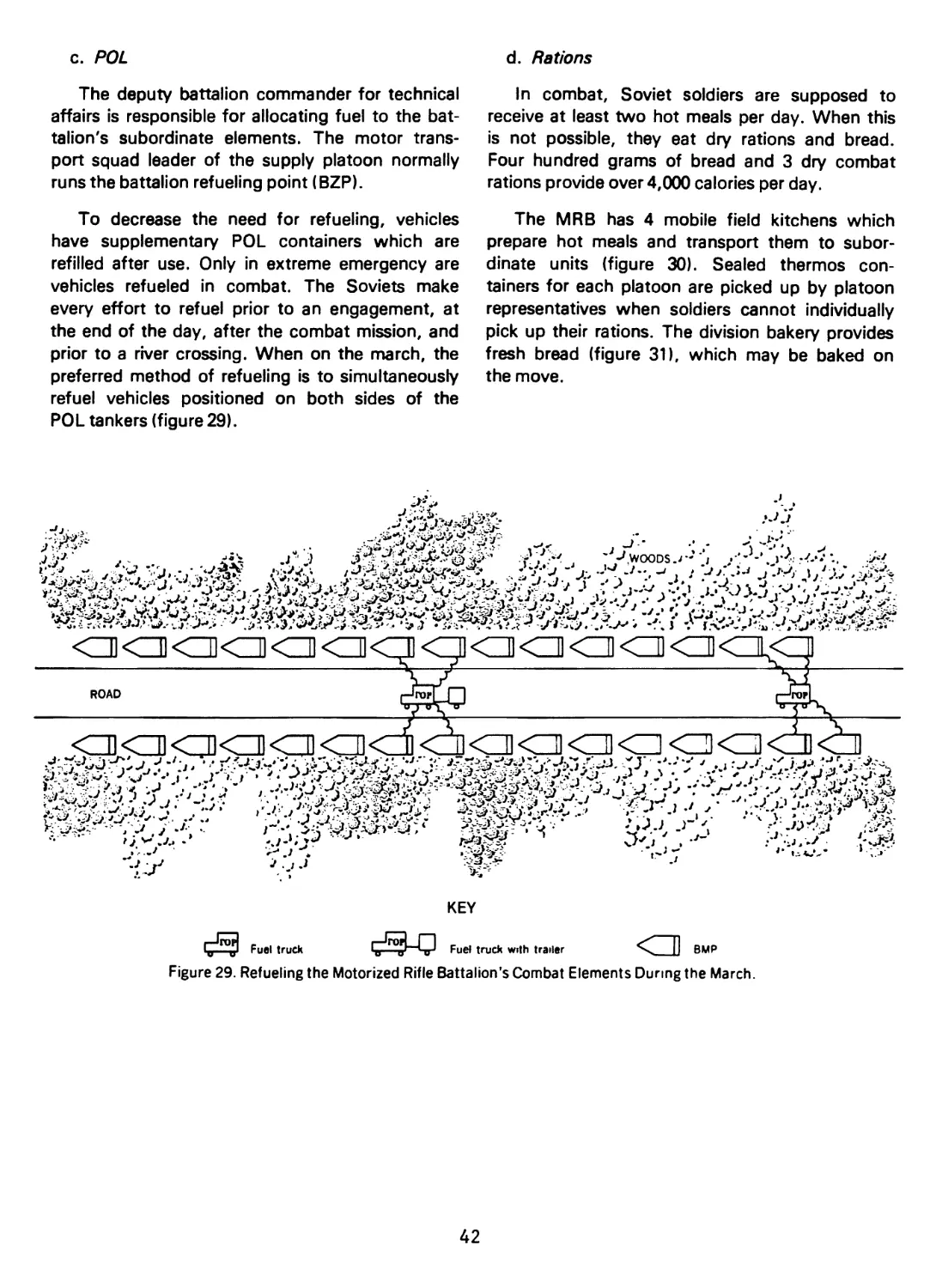

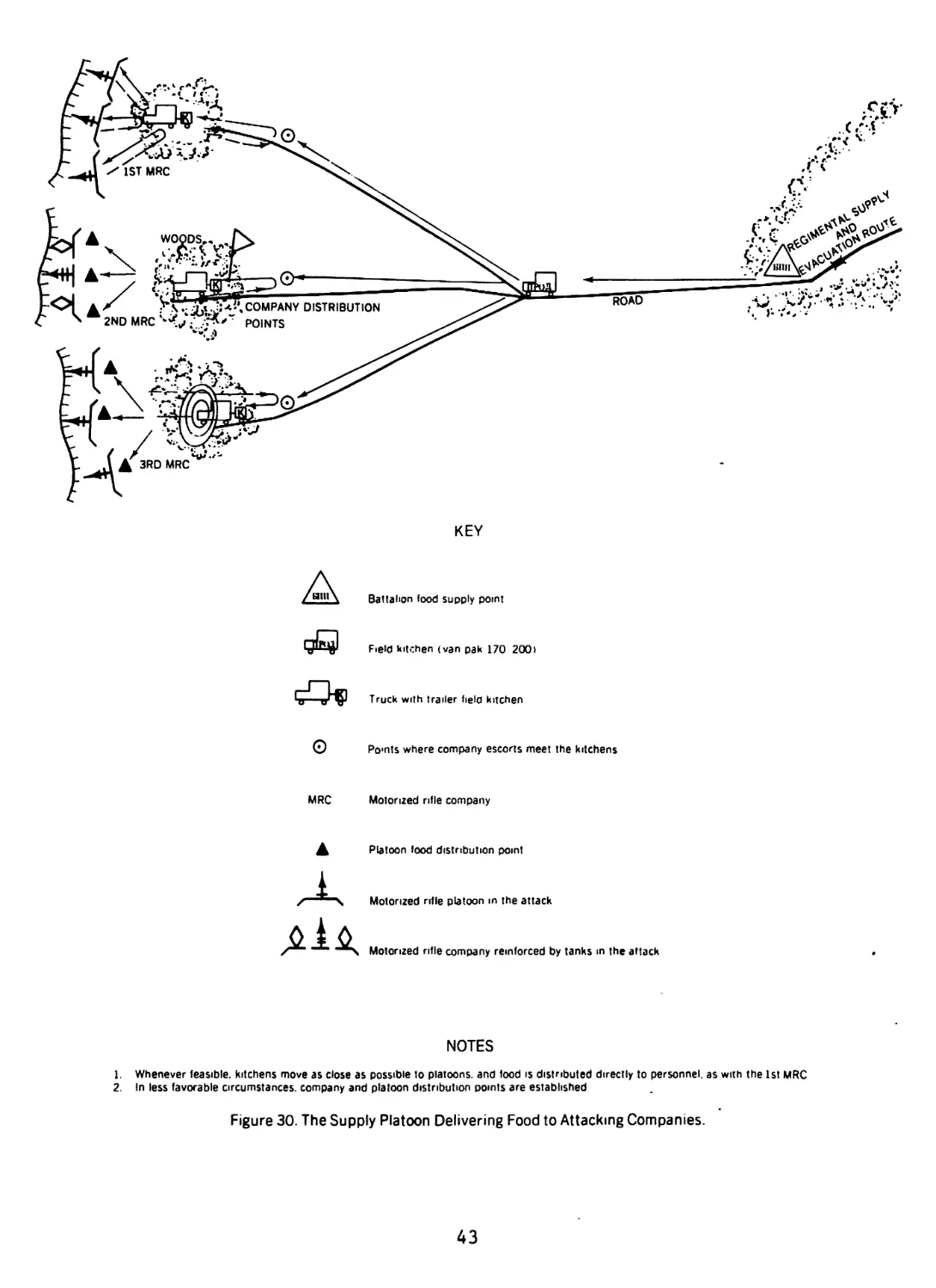

and combat service support elements have normal

spacing between vehicles in the column (figure

24). During the attack (figure 25), and in the

defense (figure 26), the rear services are position-

ed closely behind the combat units.

The battalion's administrative and logistics

responsibilities are purposely minimized to allow

the battalion commander to concentrate on his

primary mission-defeating the enemy in combat.

The regiment assumes most of the battalion's ad-

ministrative burden and augments the battalion,

as required, logistically.

5 WOODS J

PEAR SERVICES

SUPPLY PLATOON

KEY

Motorized nfle battalion, reinforced with

tanks and artillery in march column

UK

"J тг Truck with field kitchen trailer

Battalion ambulance with trailer

Field kitchen (van pack 170/200)

Battalion ammunition truck

Fuel truck

и u nr Truck with water trailer

| PM

и о Hr Repair workshop with trailer

Fuel truck with trailer

NOTES

1 When there is no enemy threat, fuel trucks are often placed at the head of the rear service elements

2 Distances between rear service vehicles in the march are normally the same as those separating other vehicles (15to5O meters during road movement and 50

to 200 meters during tactical cross-country movement)

Figure 24. Motorized Rifle Battalion Rear Service Support Elements During the March.

37

KEY

MRC Motorized rifle company

Battalion technical observation point

Motorized rifle company reinforced

by tanks m the attack

Regimental commander's

com ma nd-observation post

Battalion medical point

Battahon commander's

command-observation post

Battalion refueling point

Reg*menta boundary

Battalion food supply point

Batla>hor. covnaar,

Battalion ammunition supply point

Figure 25. Rear Service Support During the Attack

38

KEY

MRC Motorized rifle company

Battalion ammunition supply point

Battalion technical observation point

Battalion medical point

Company medical evacuation point

Company ammunition supply point

Battalion refueling point

Depression

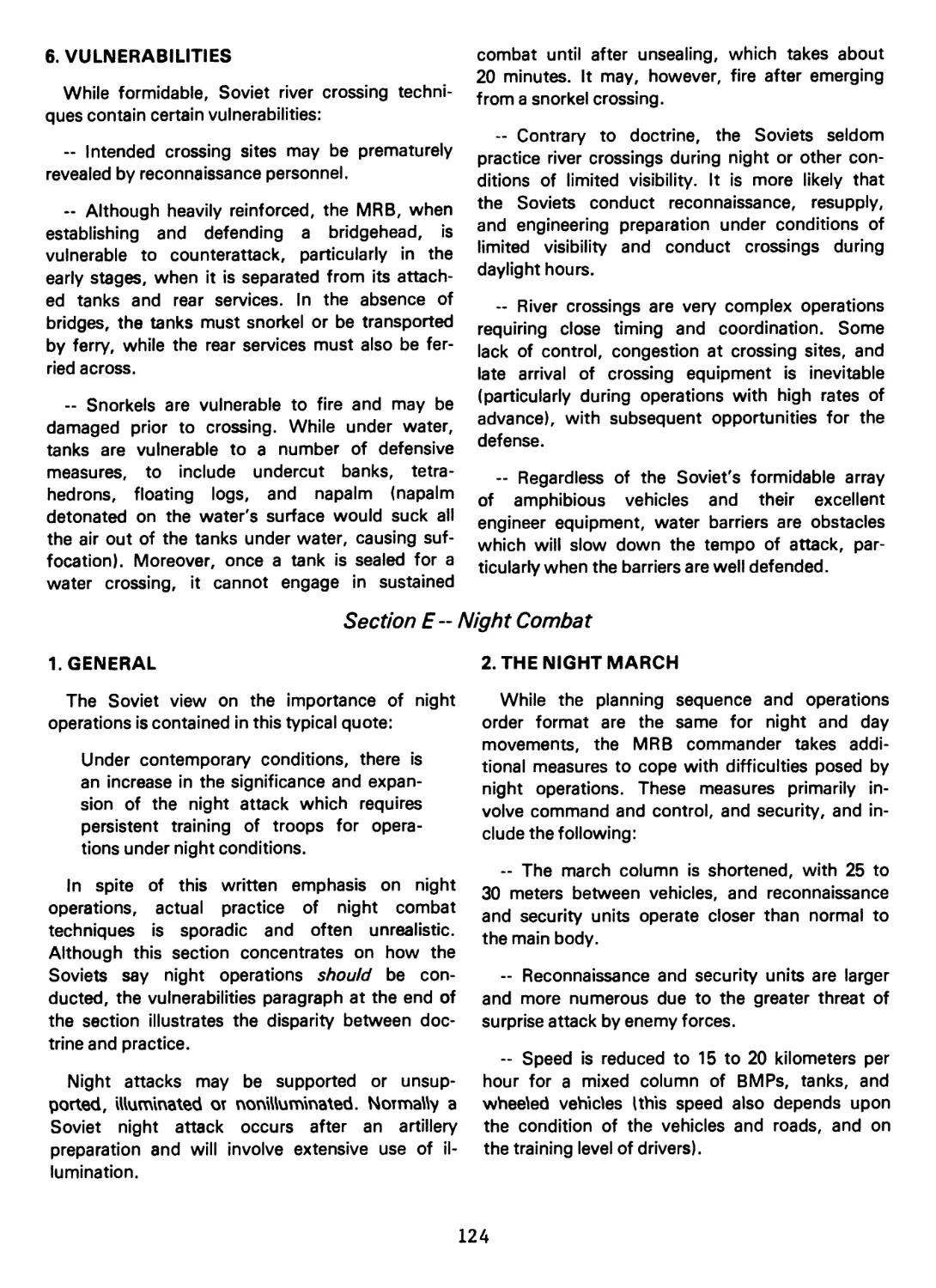

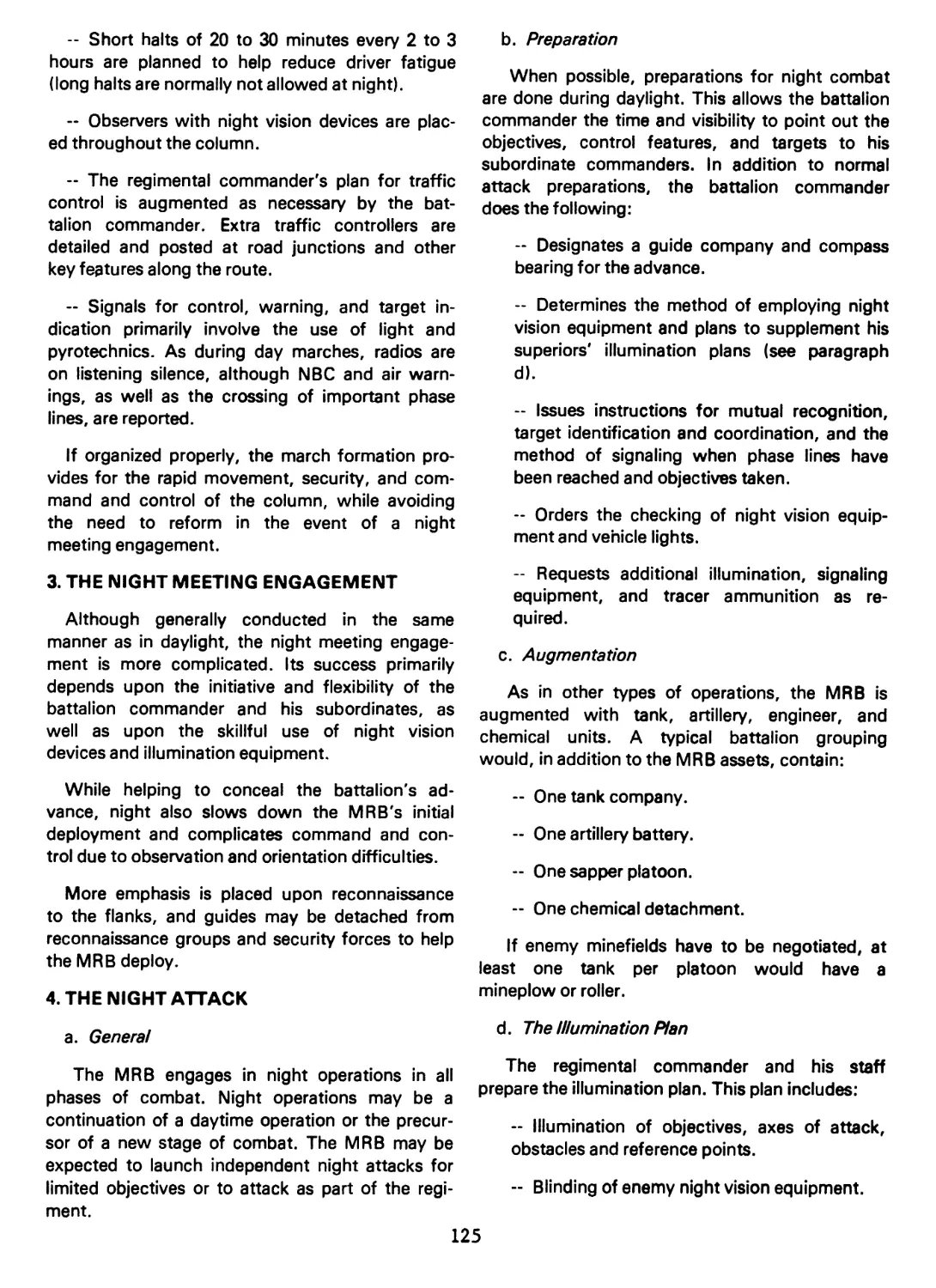

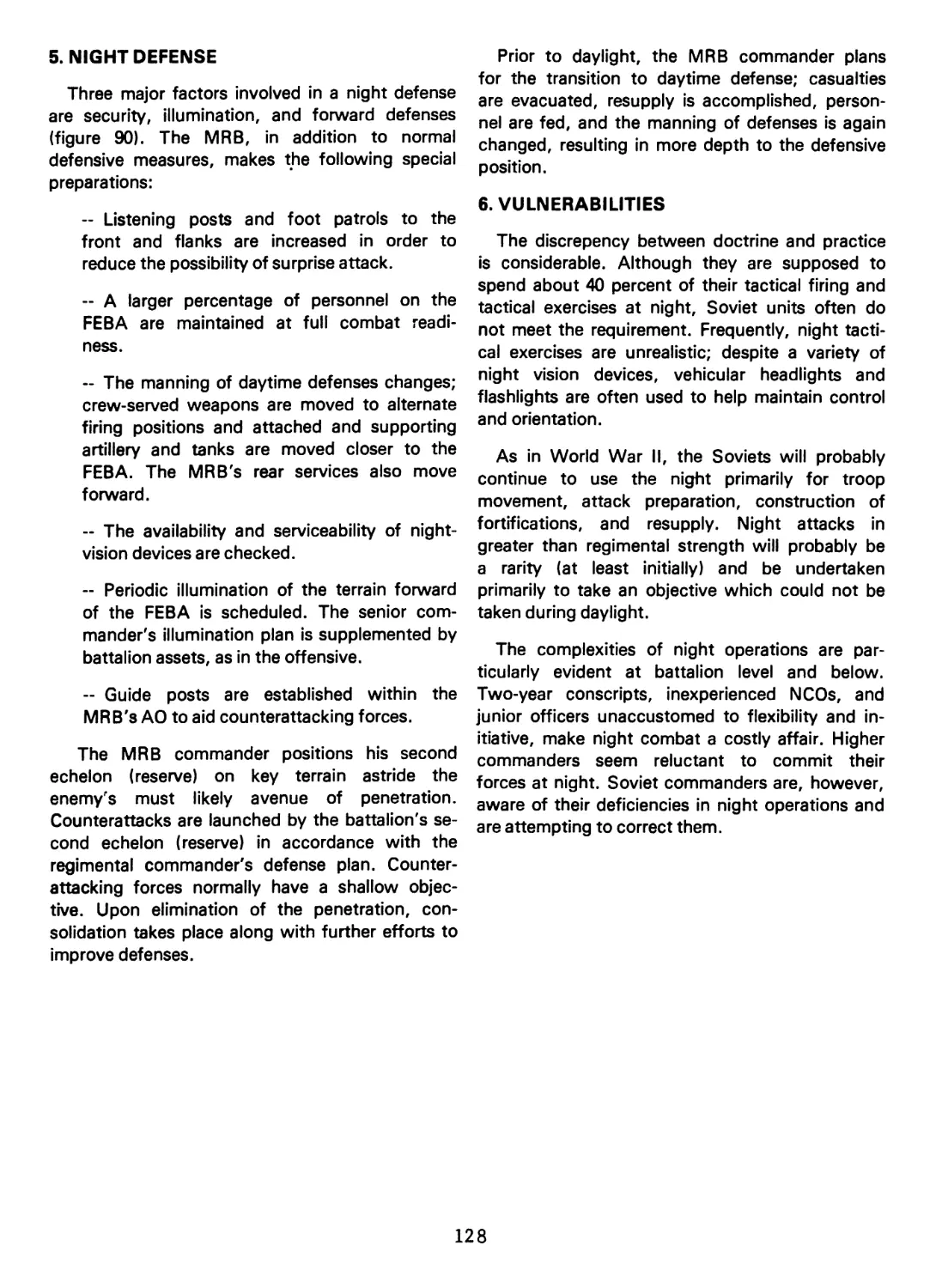

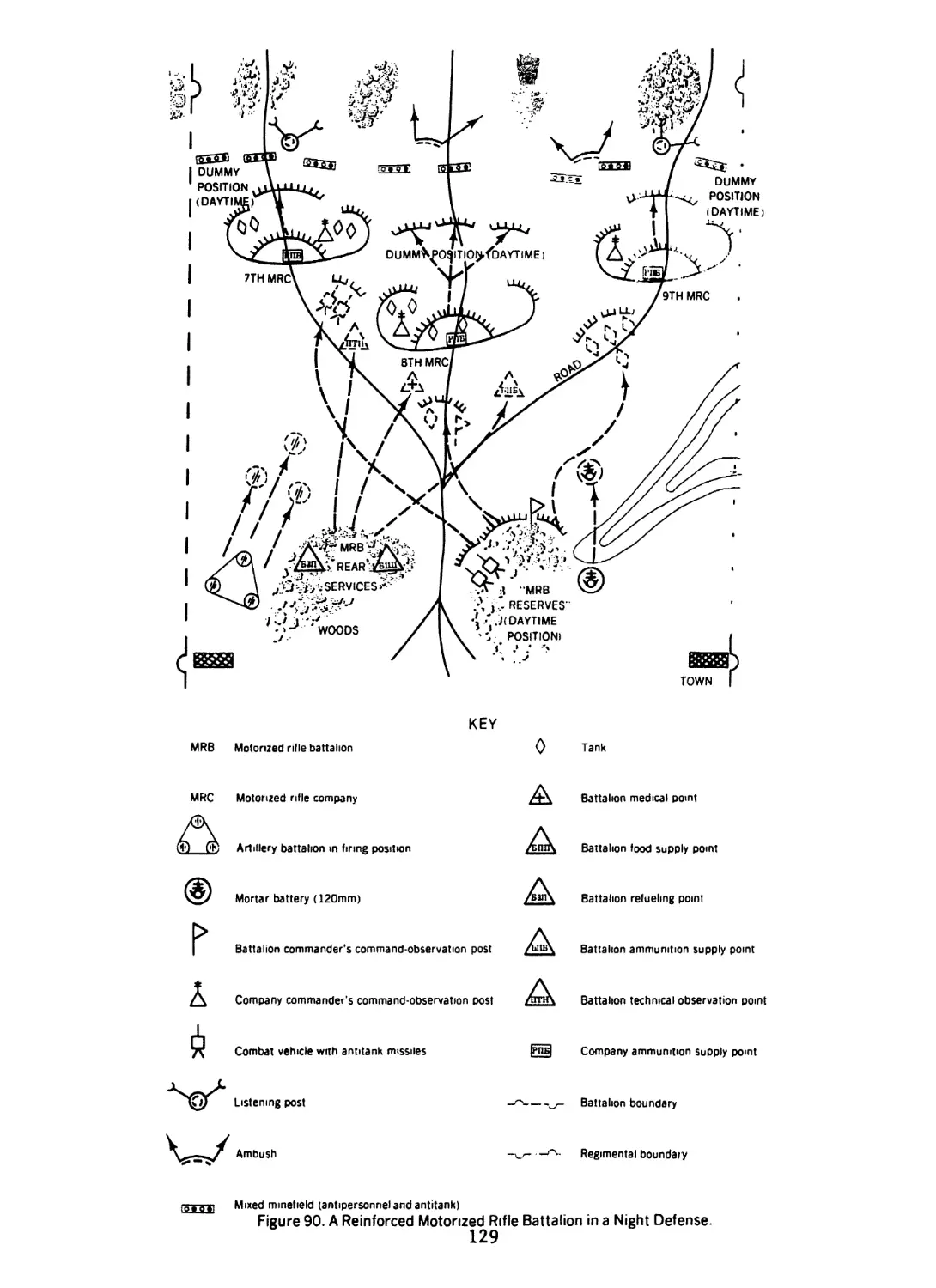

Battalion food supply point