Текст

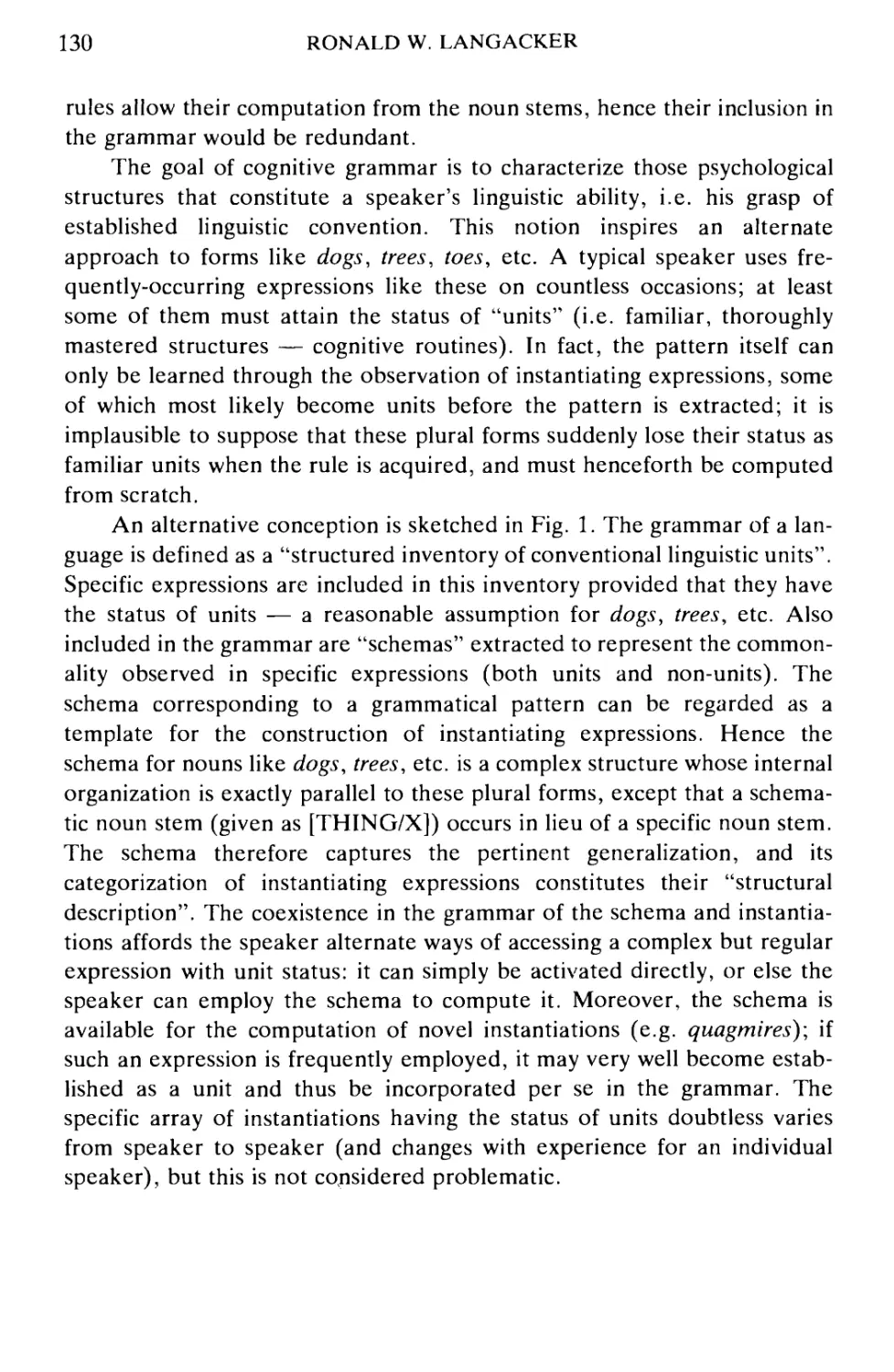

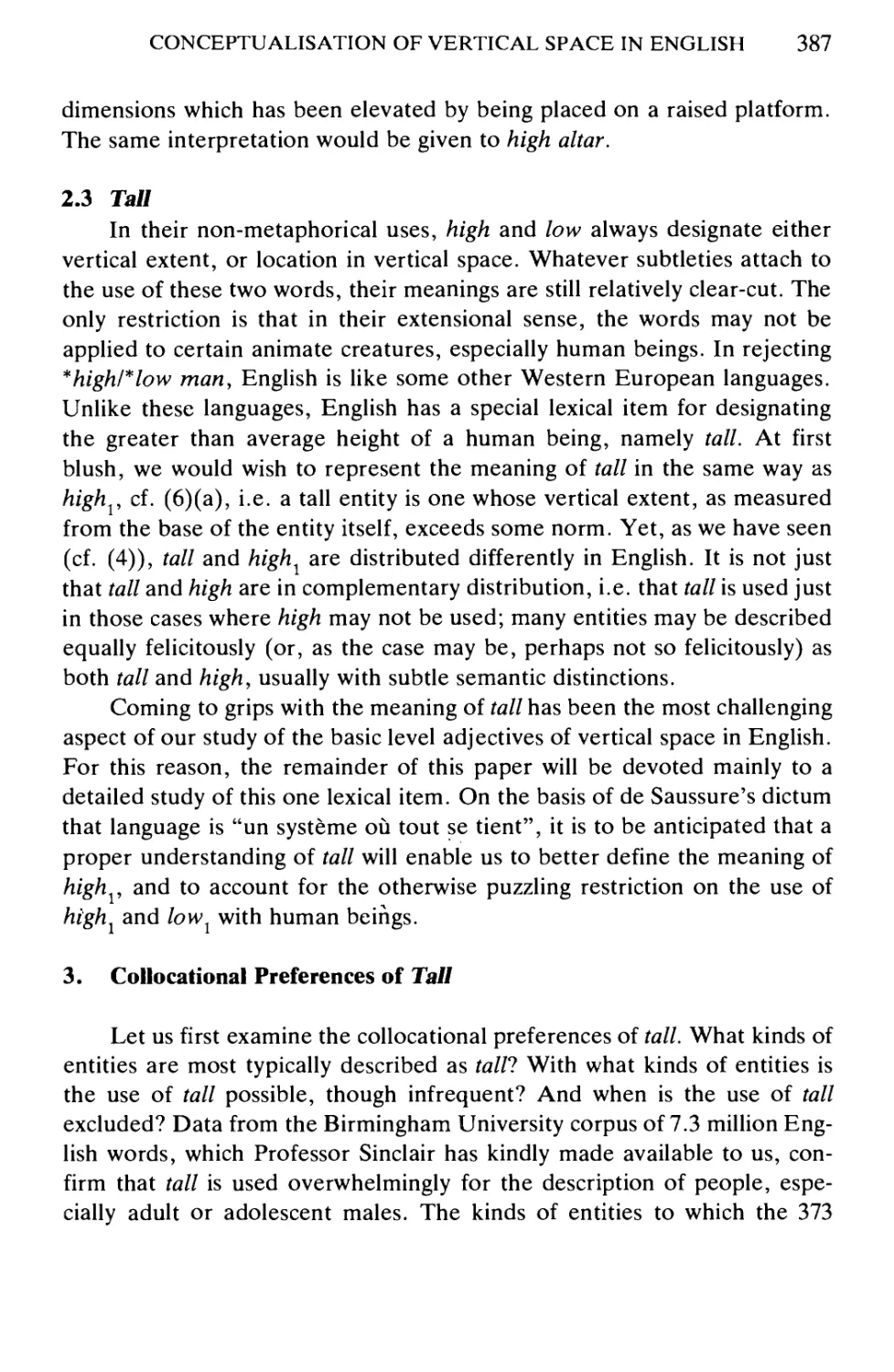

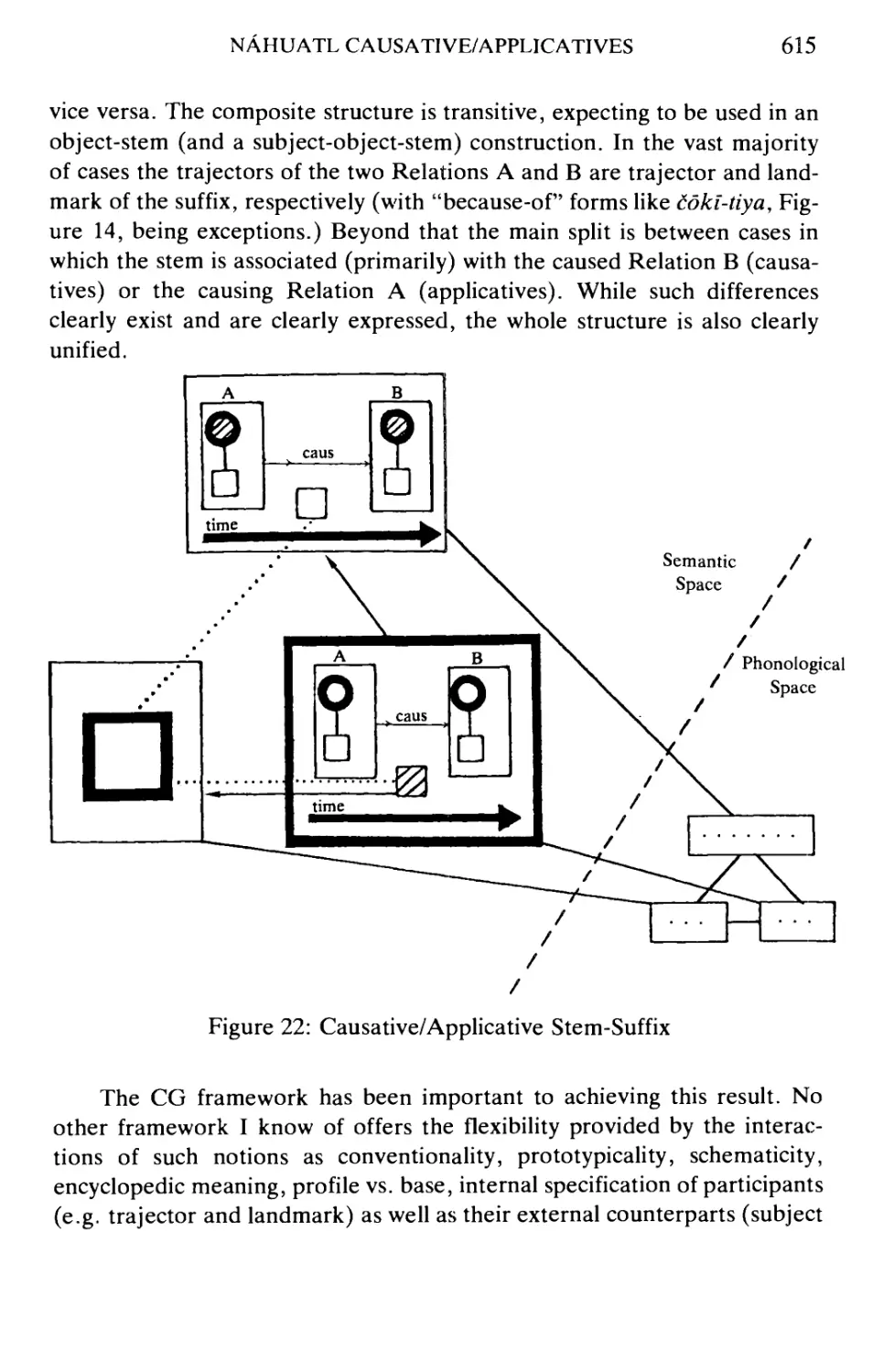

Cur nt Issues in Linguisti Theor o

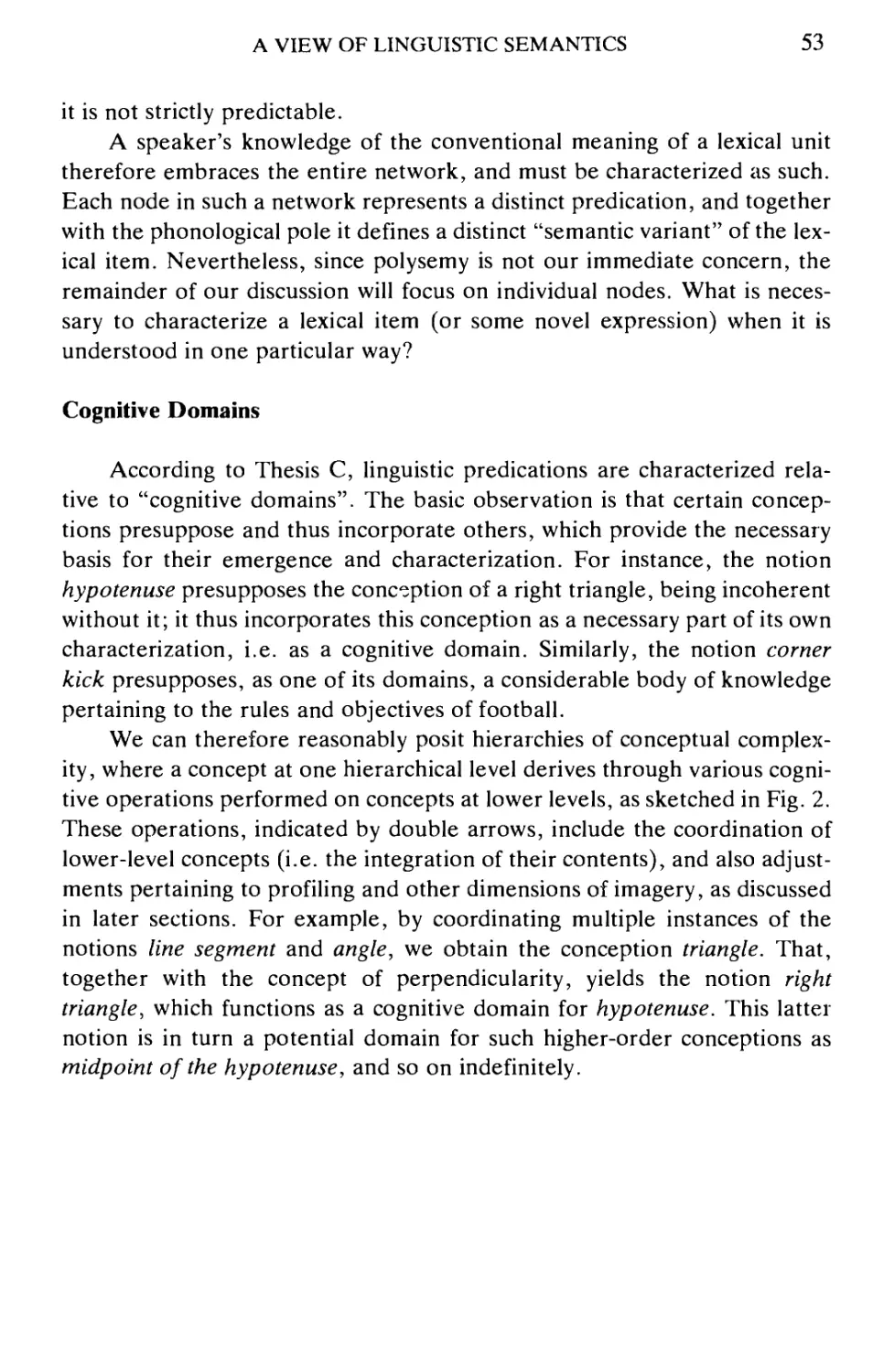

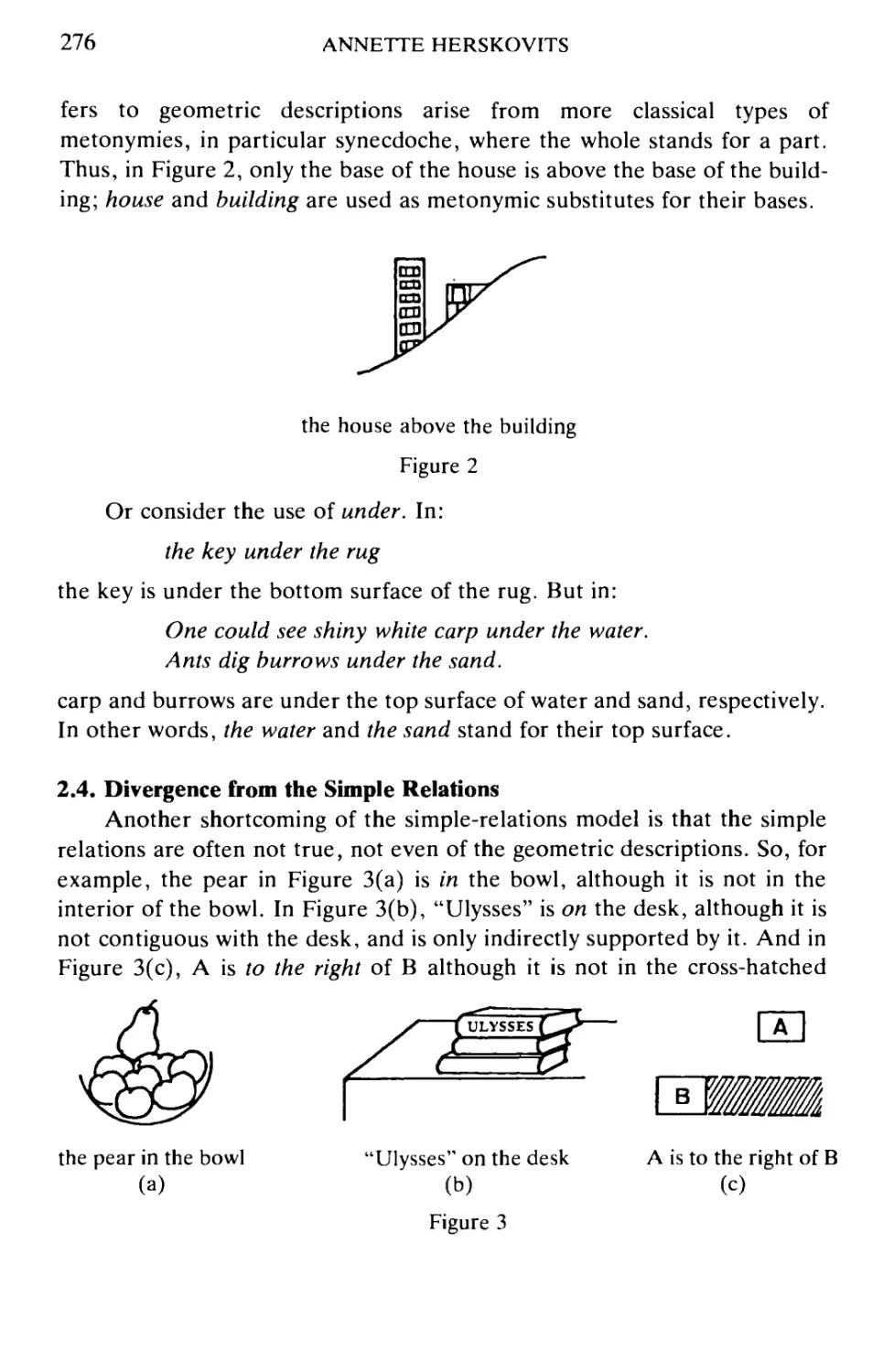

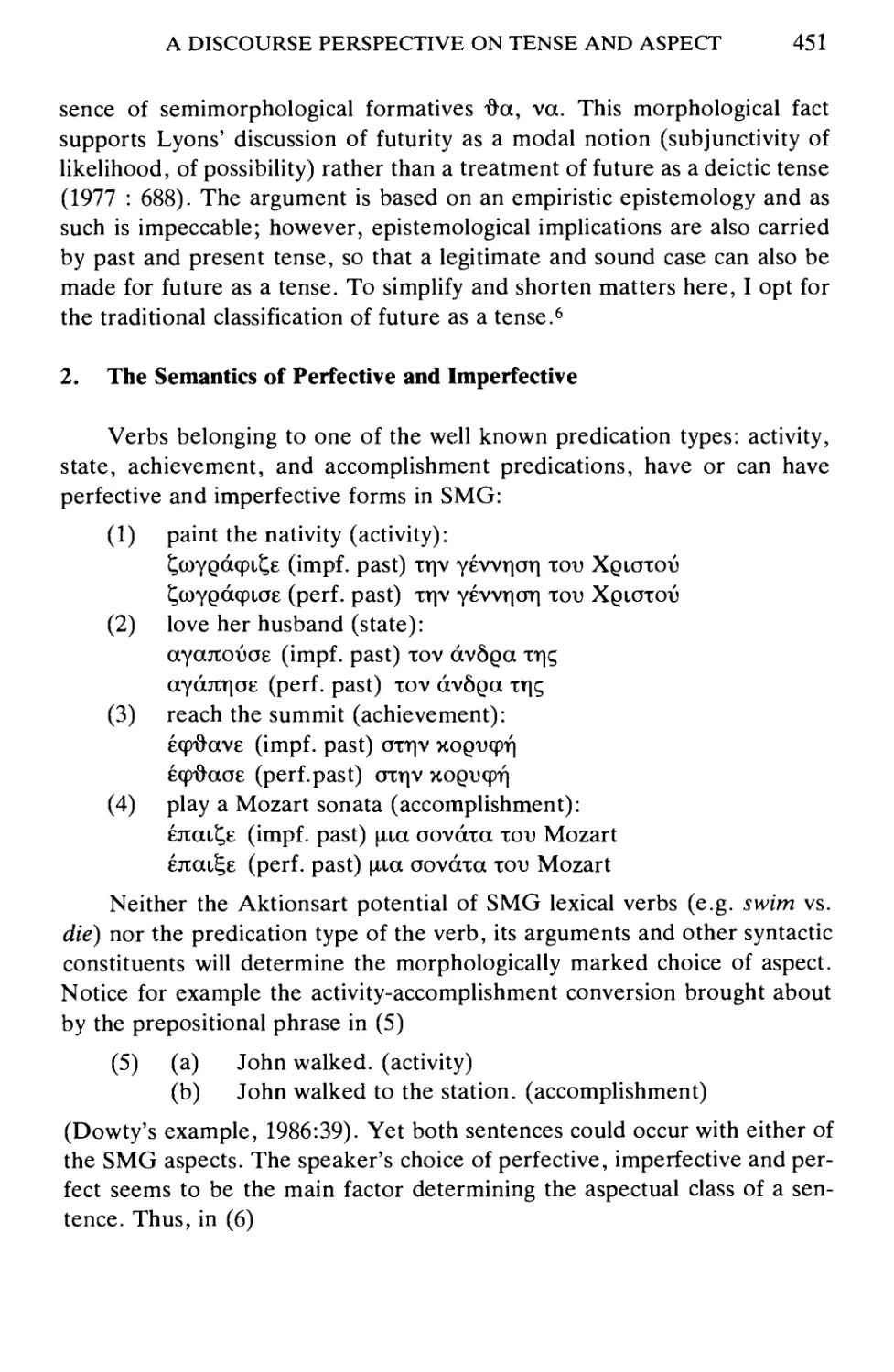

-L

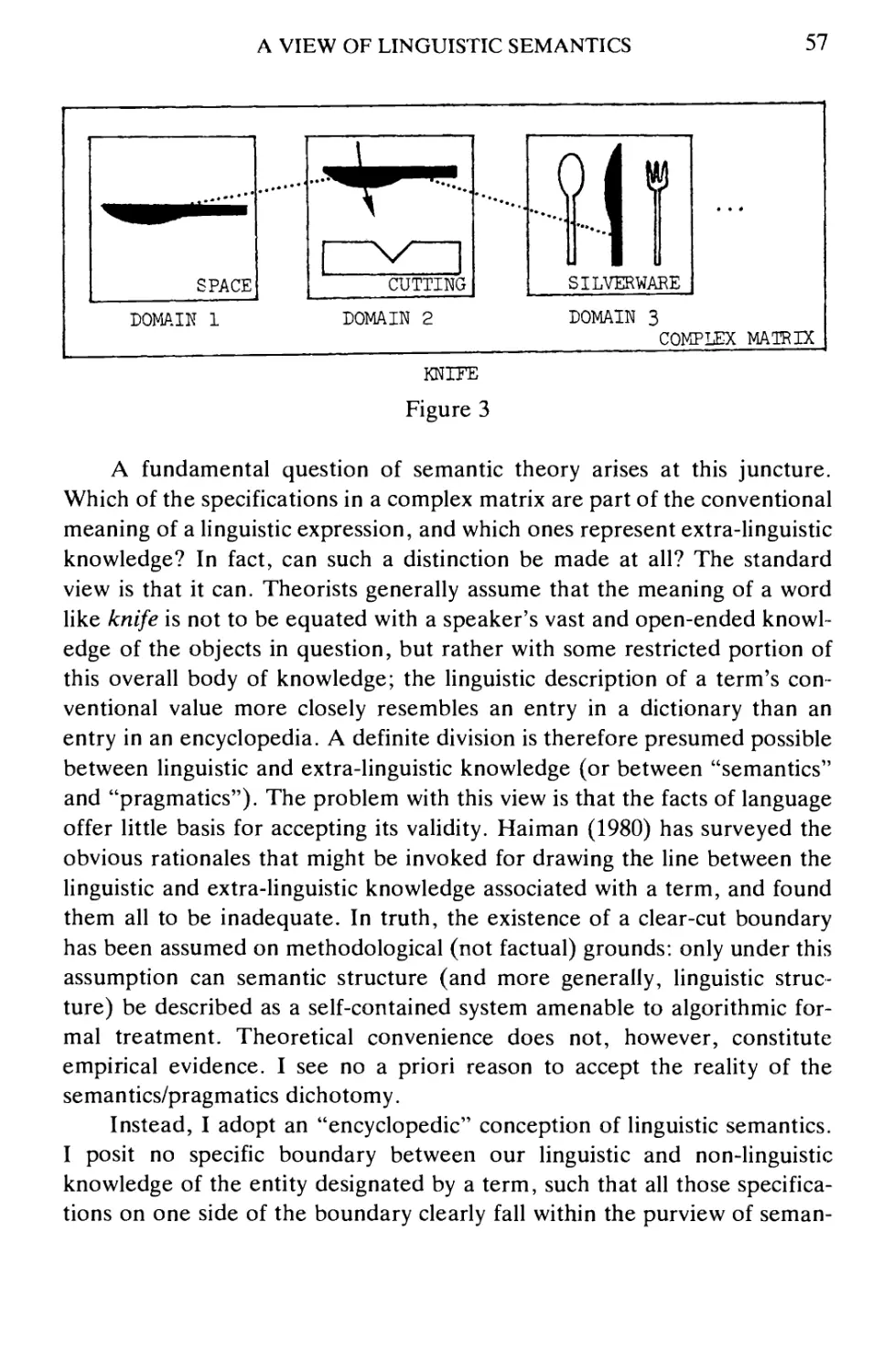

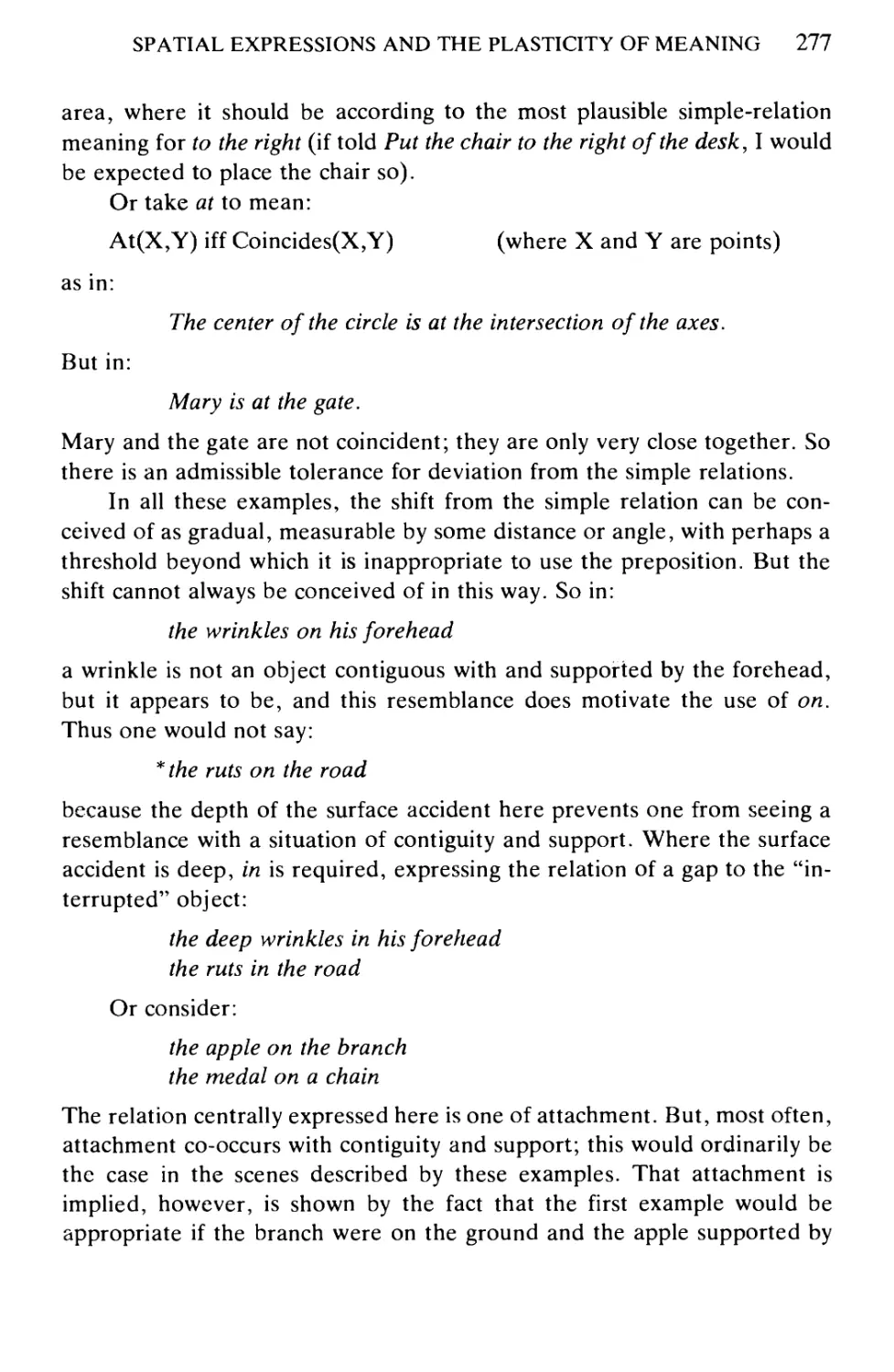

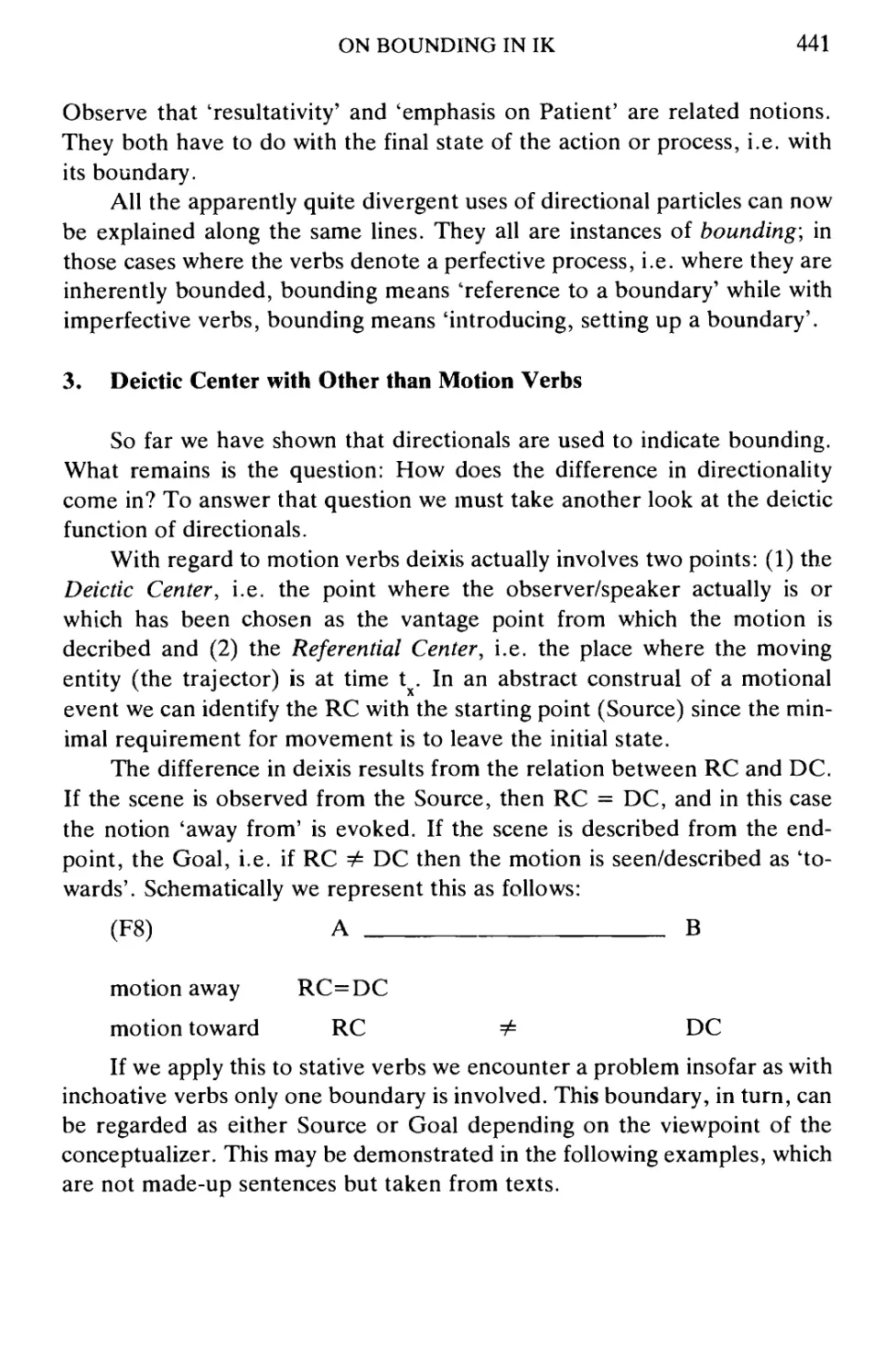

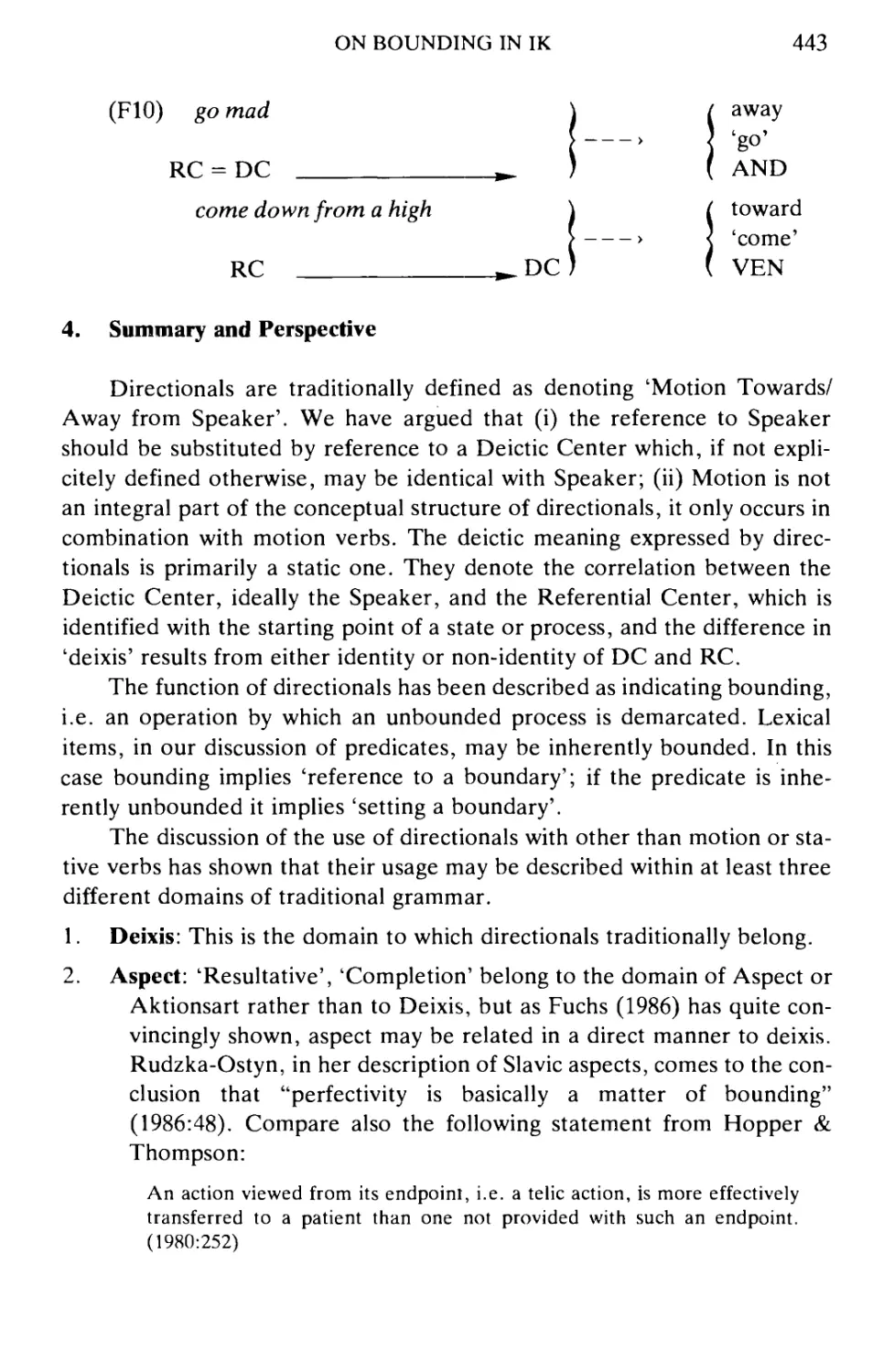

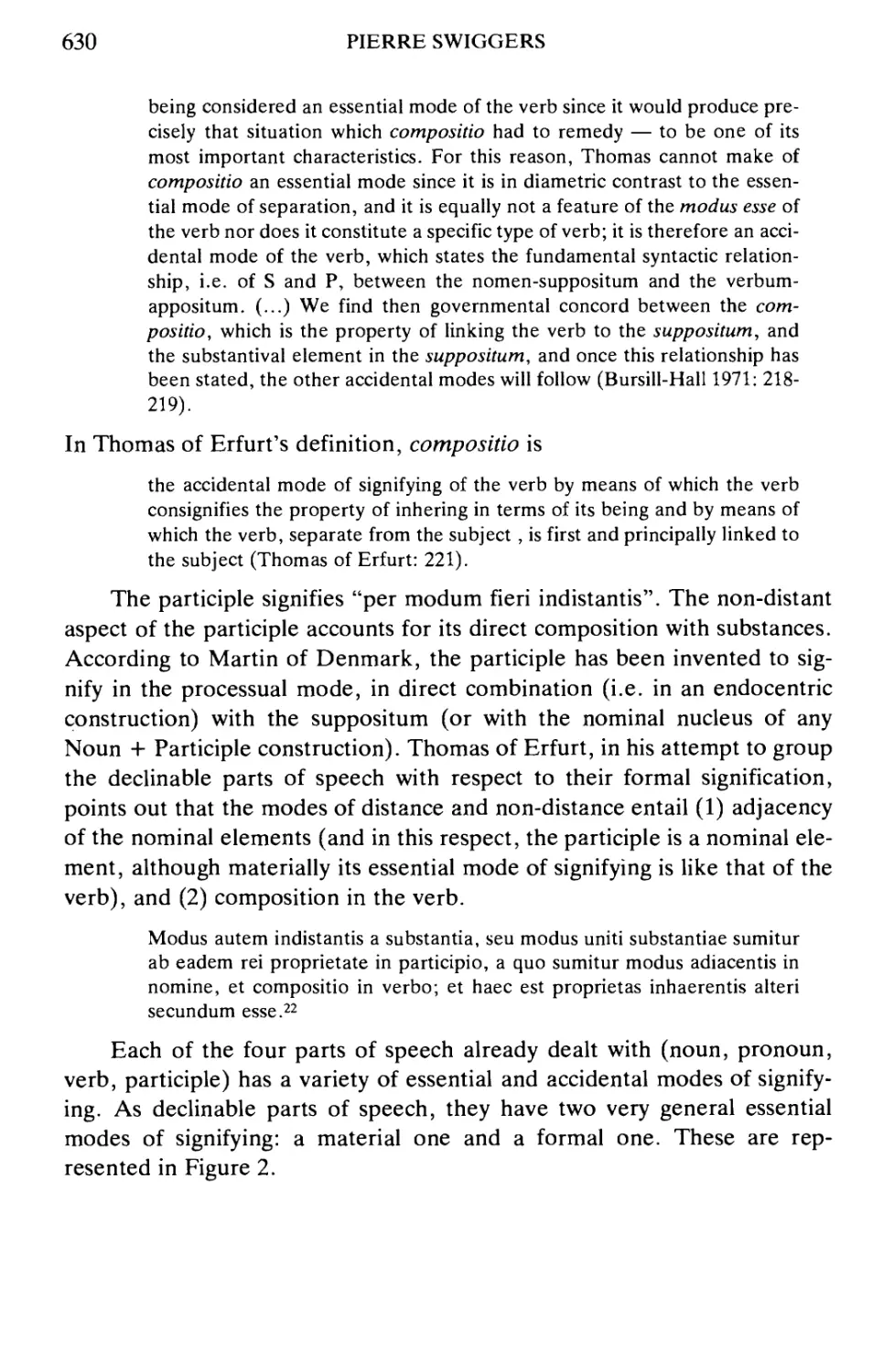

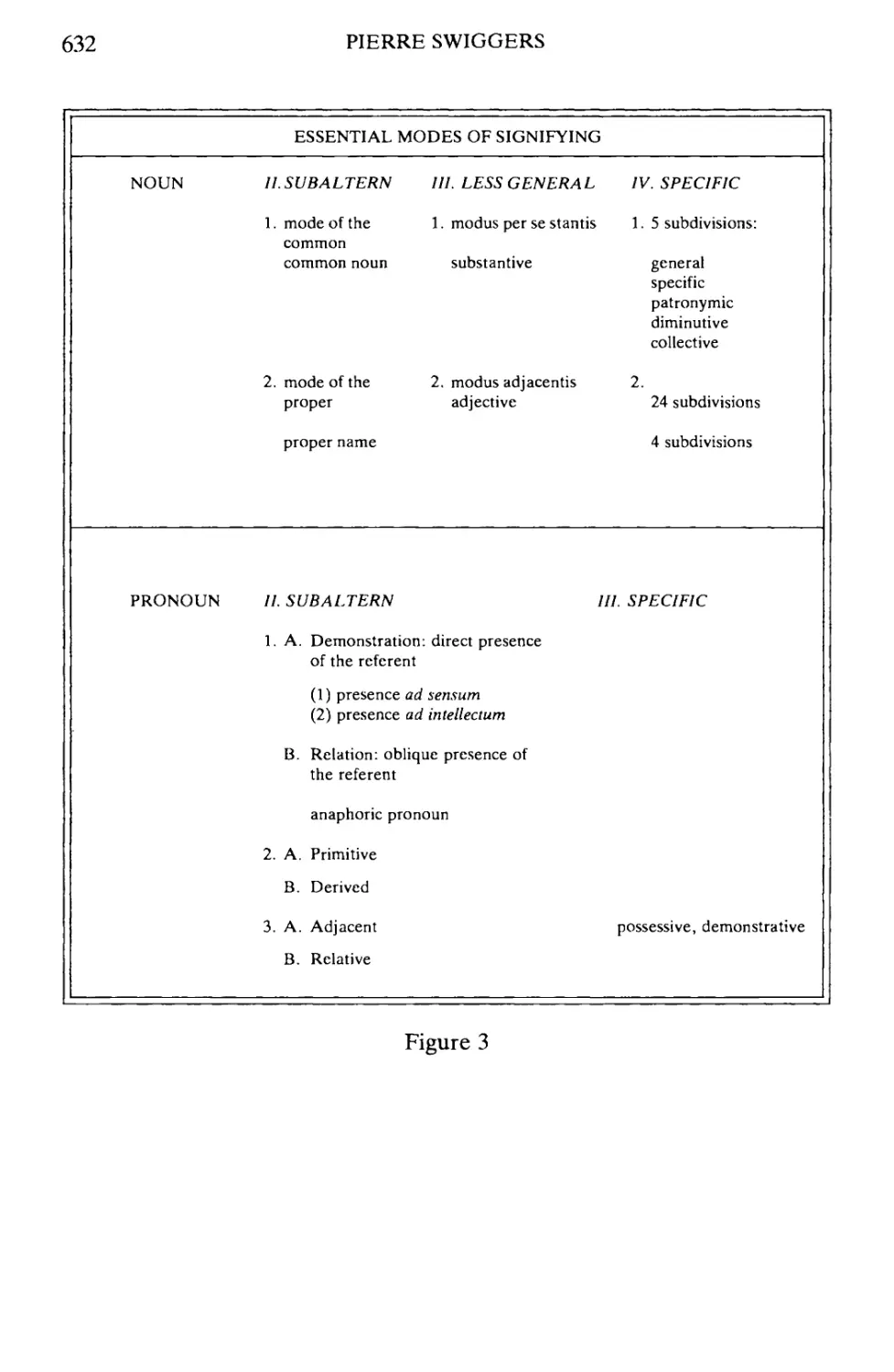

EDITED BY

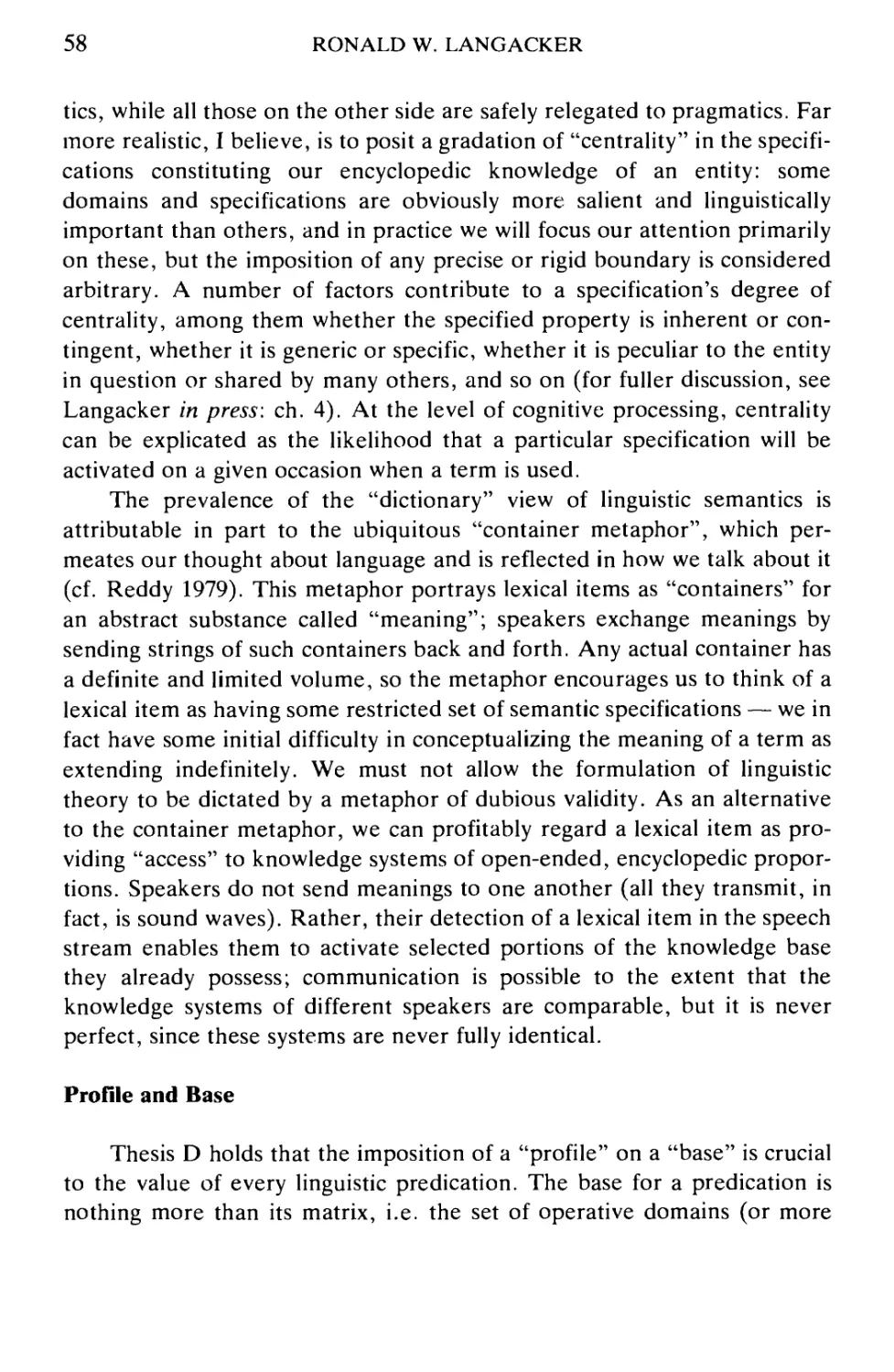

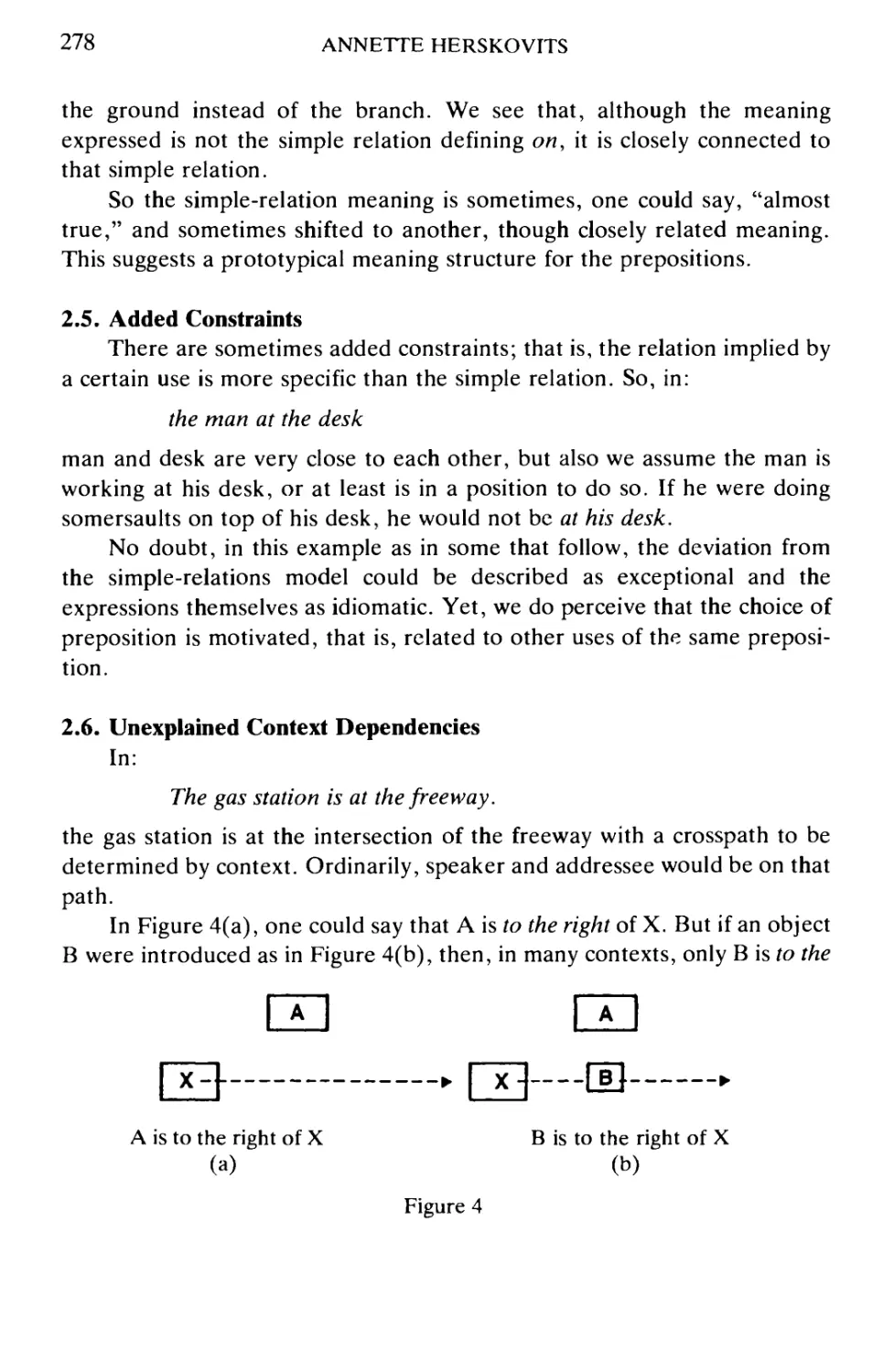

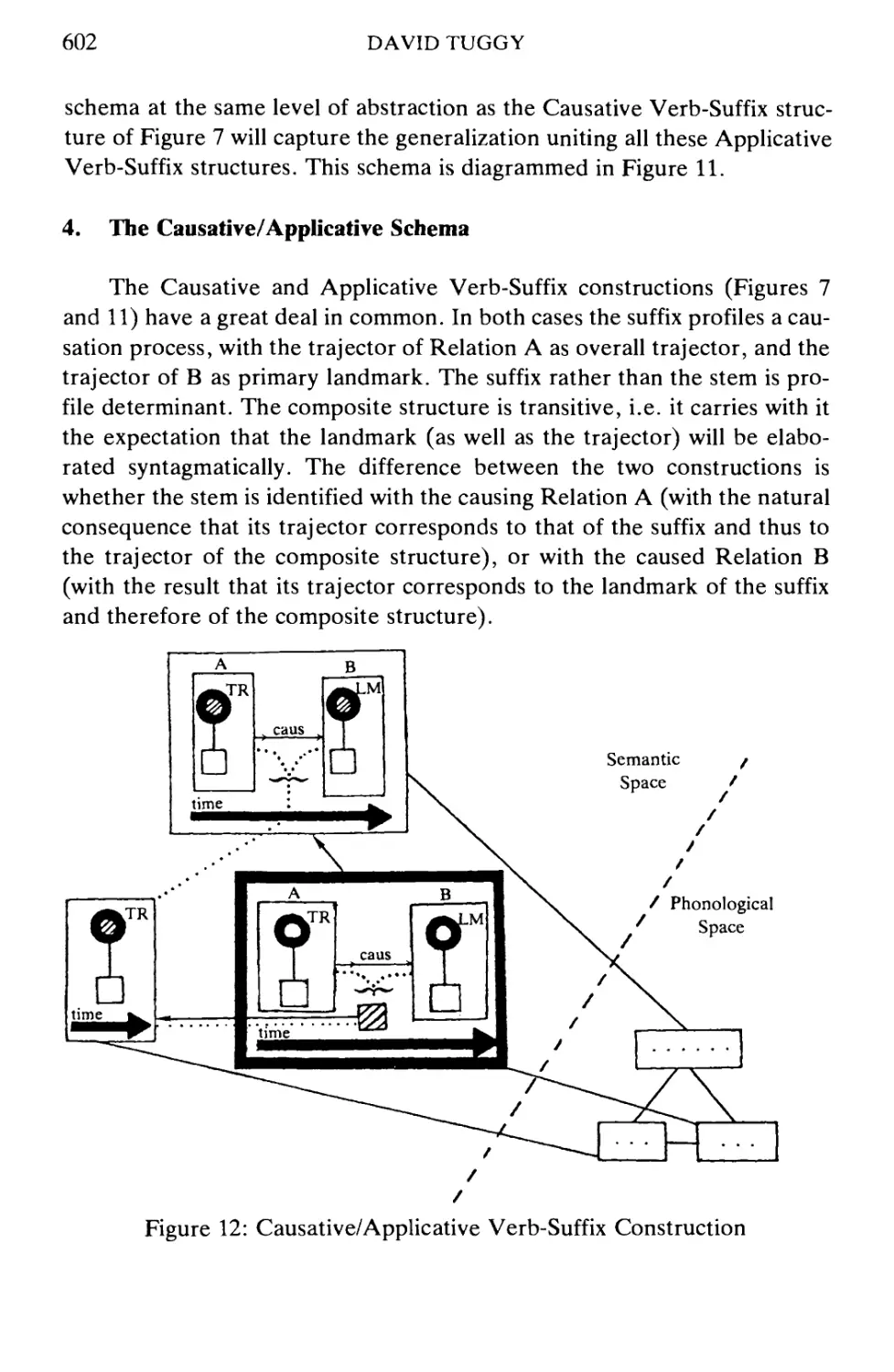

Br> n'dj Rud ka- si n

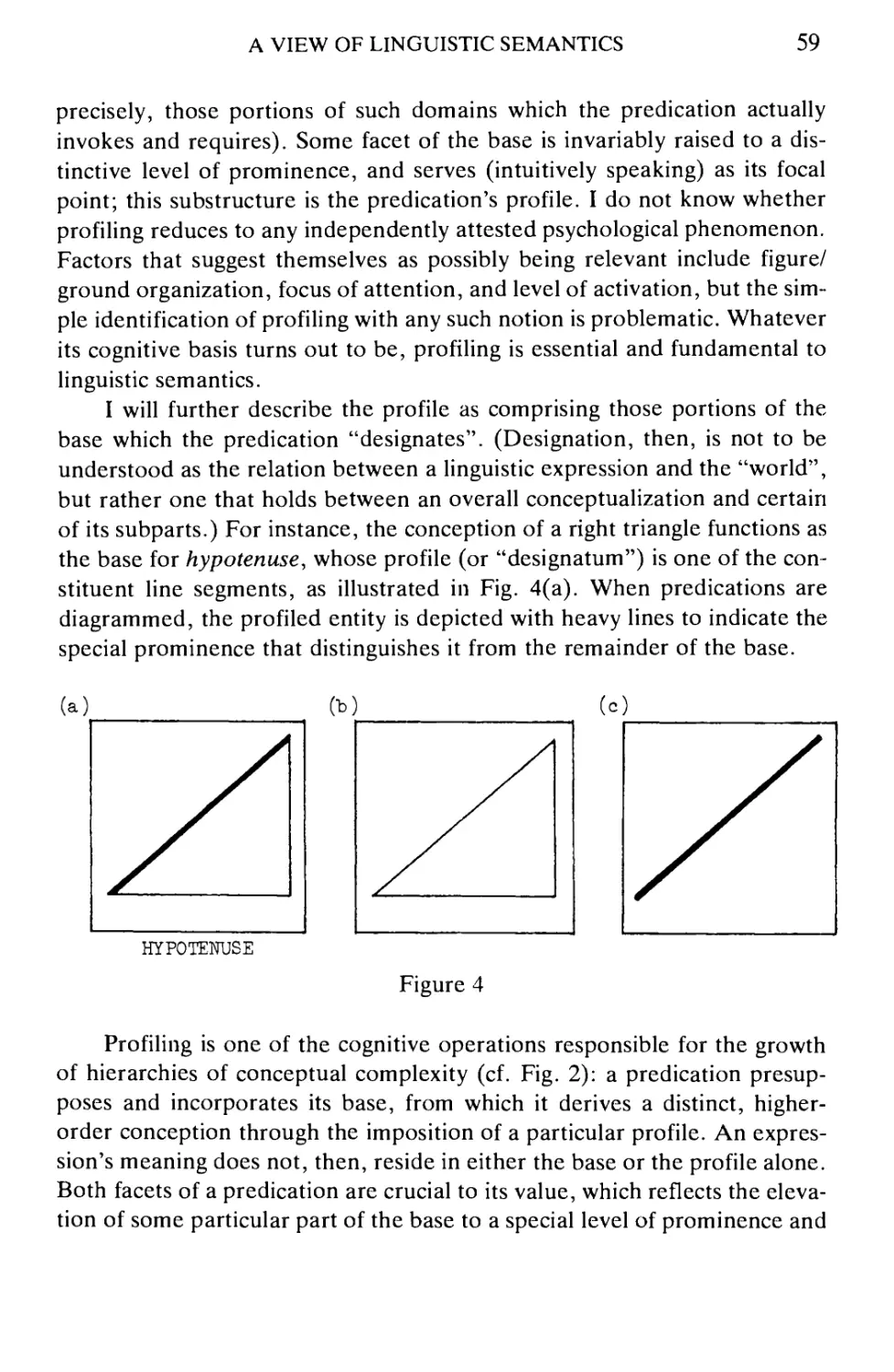

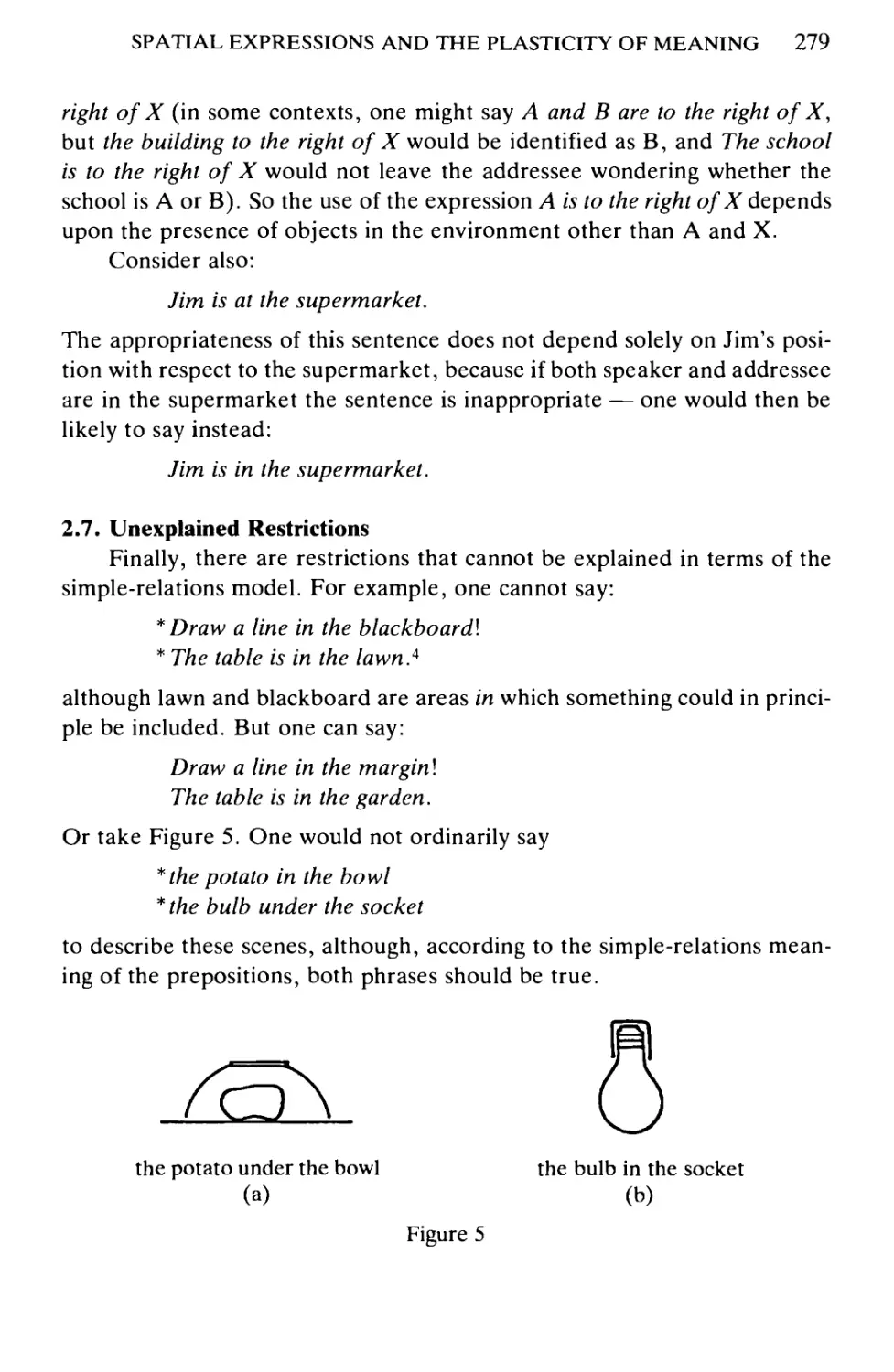

JOH BEN) INS PUBLISHI C CO P NY

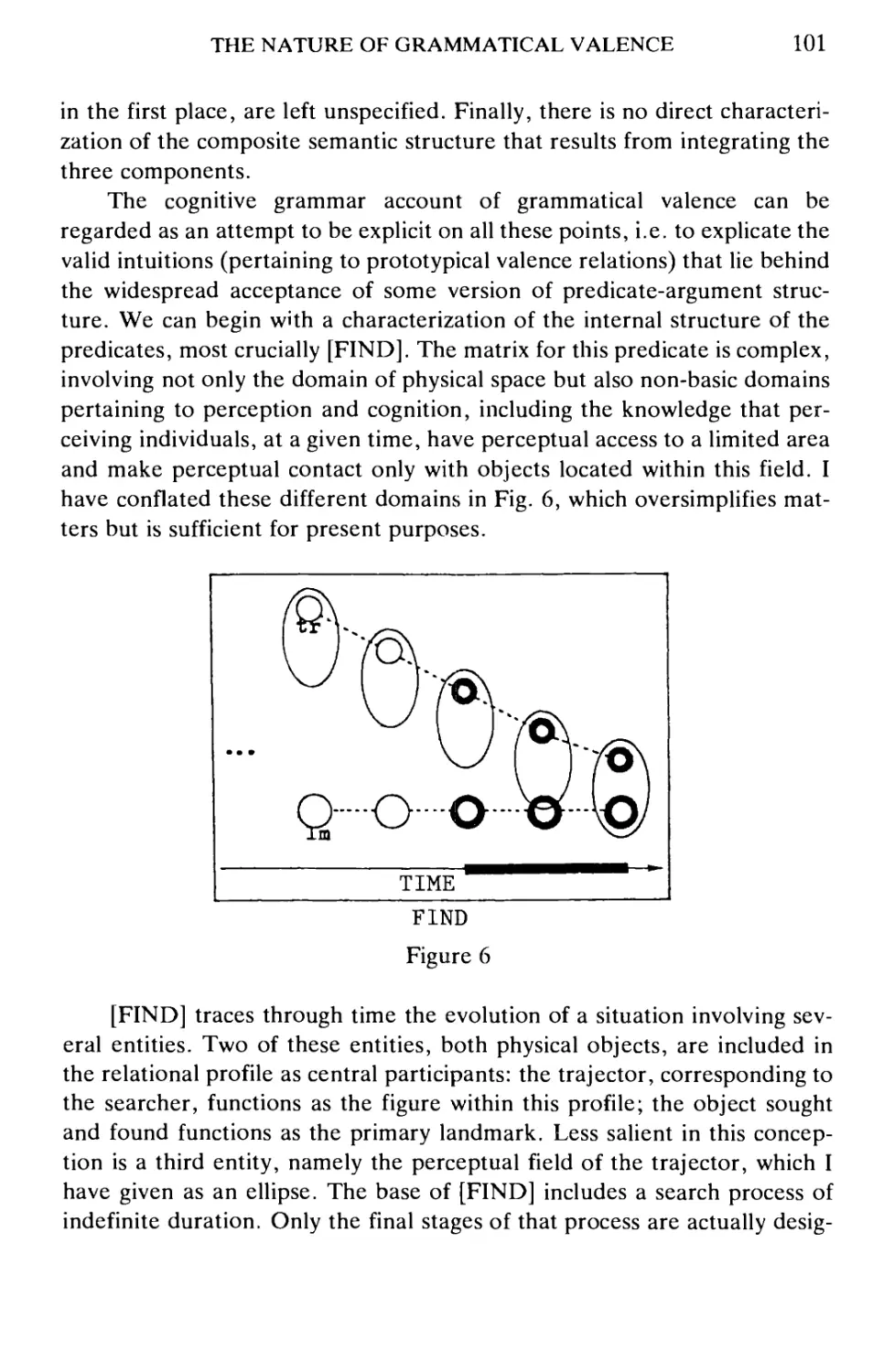

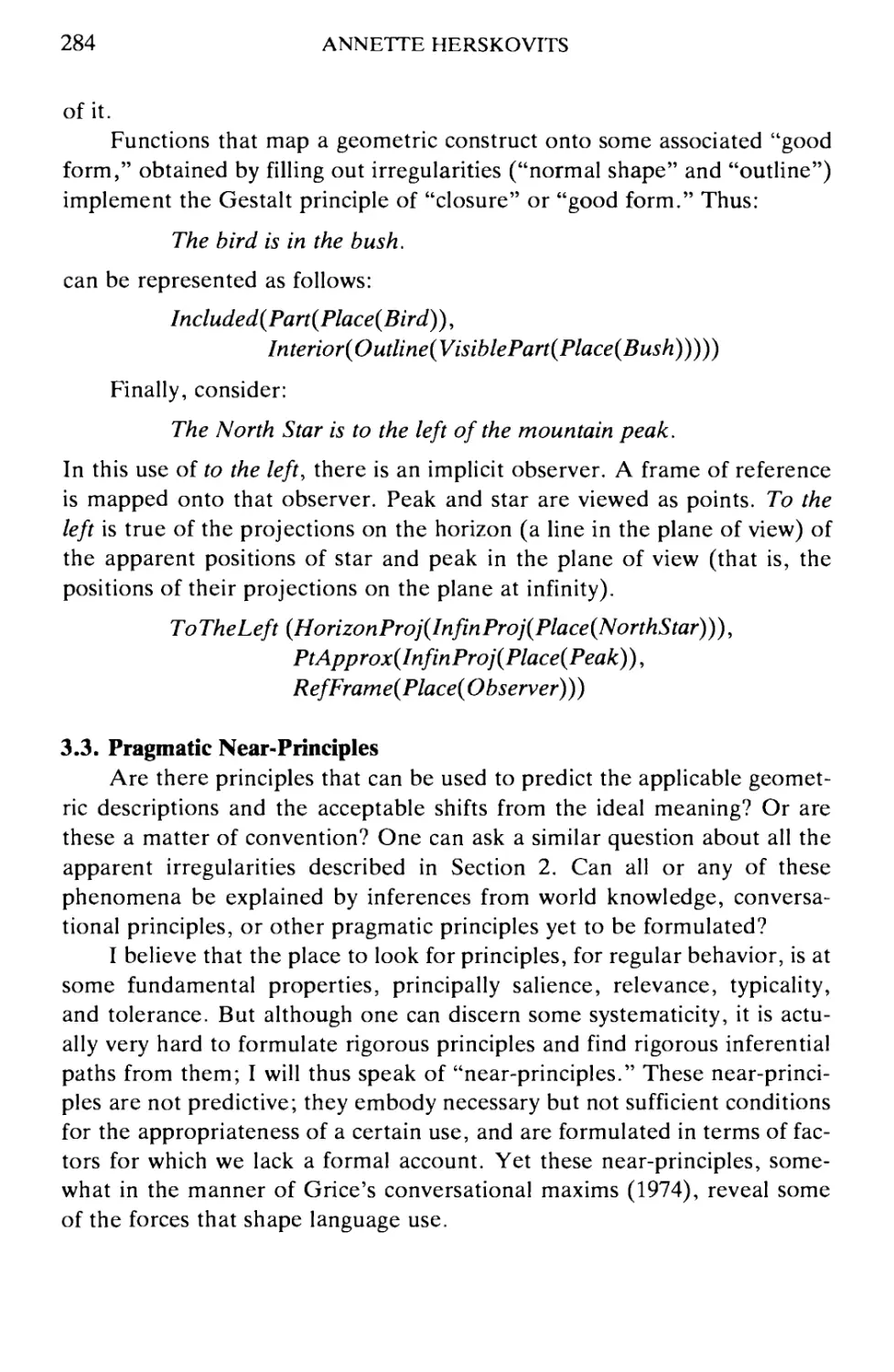

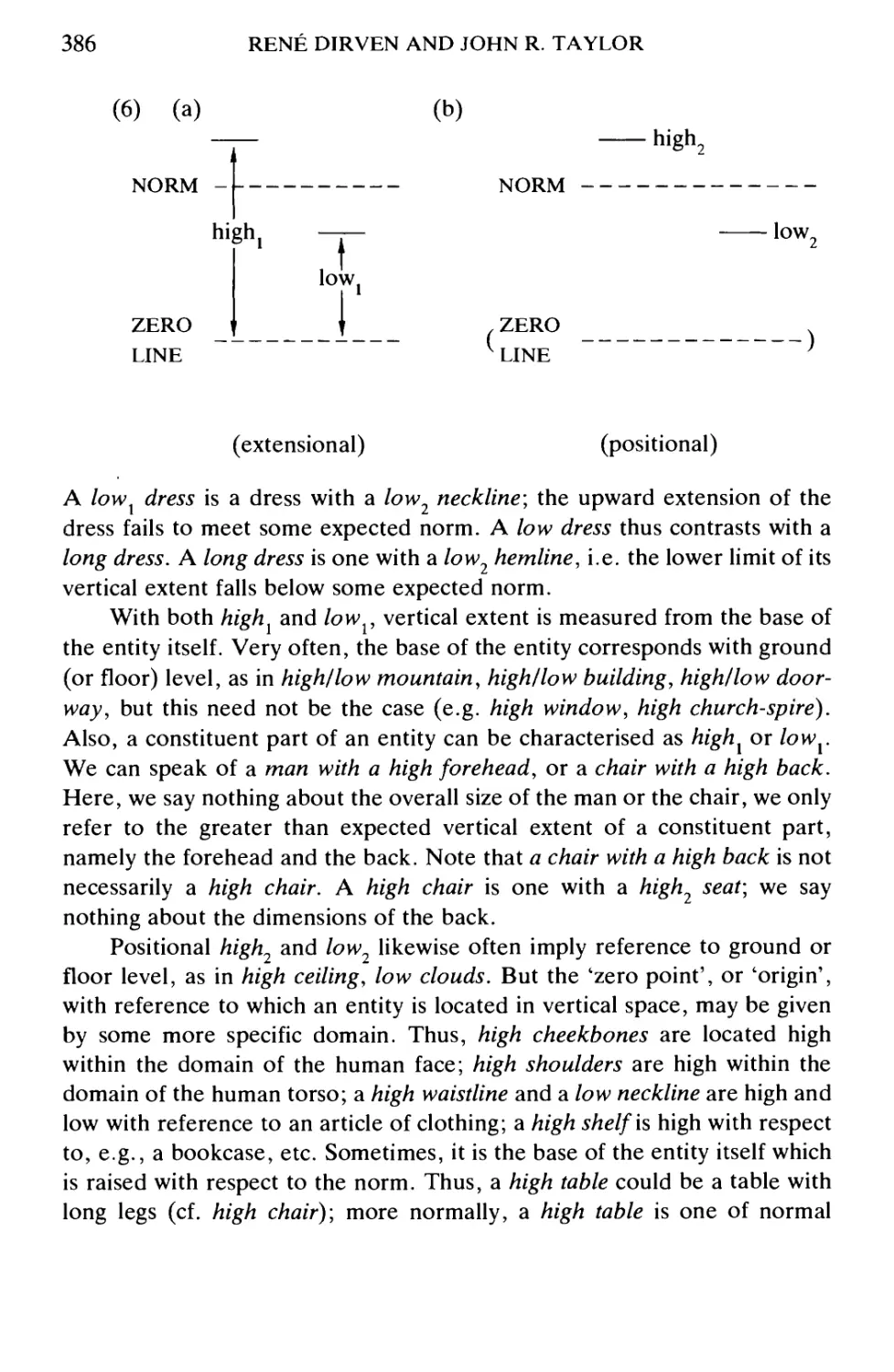

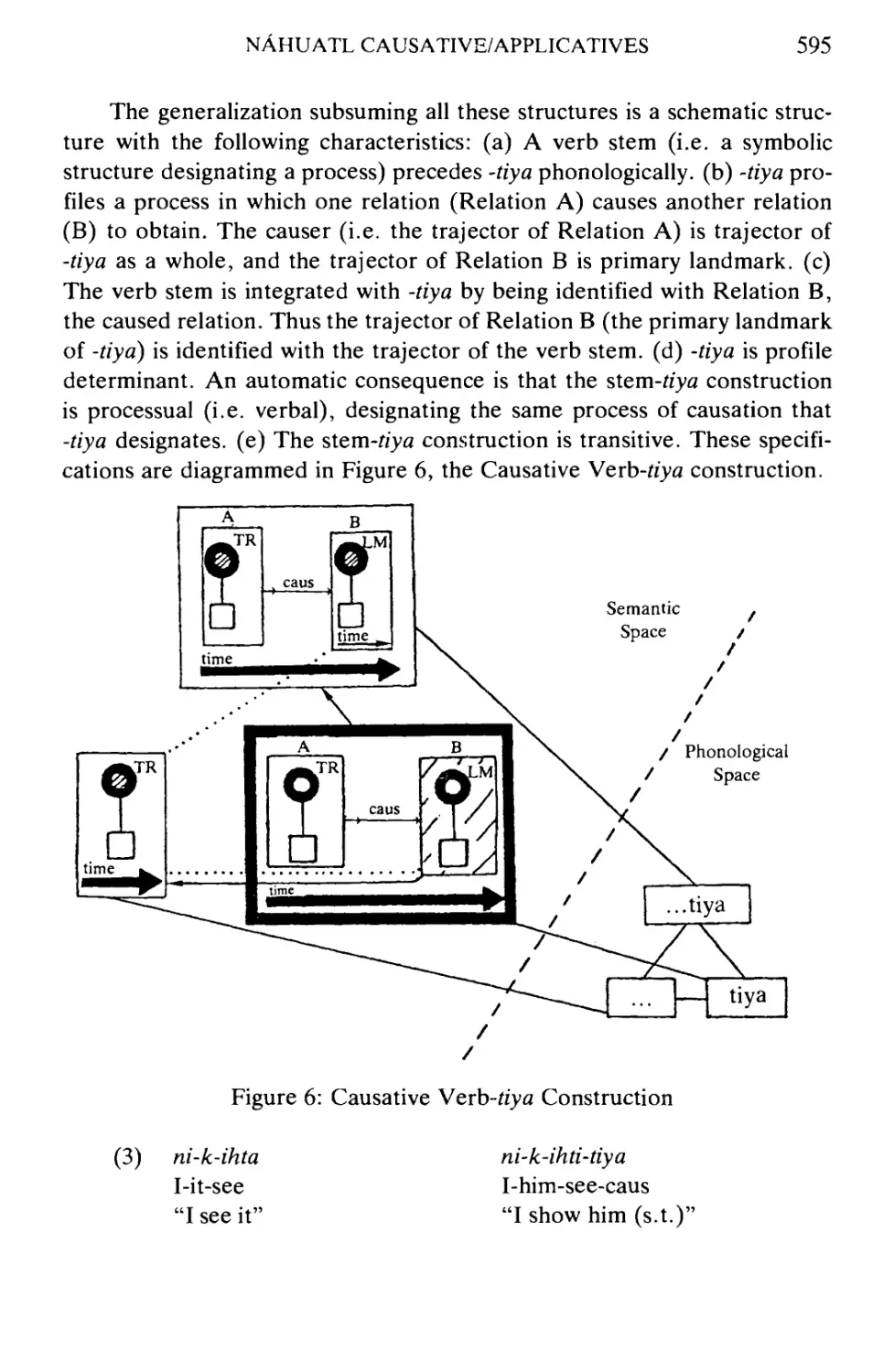

TOPICS IN COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS

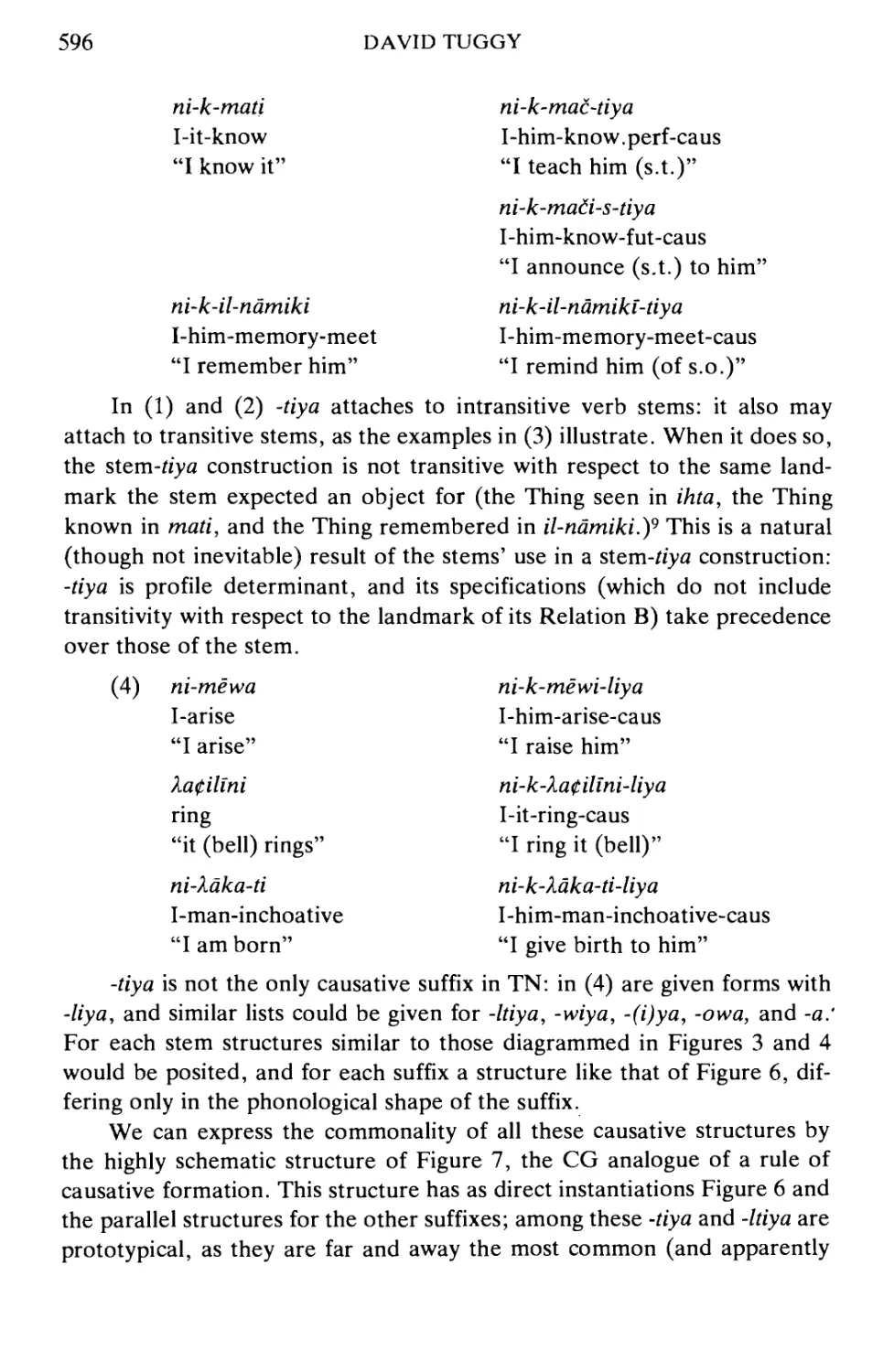

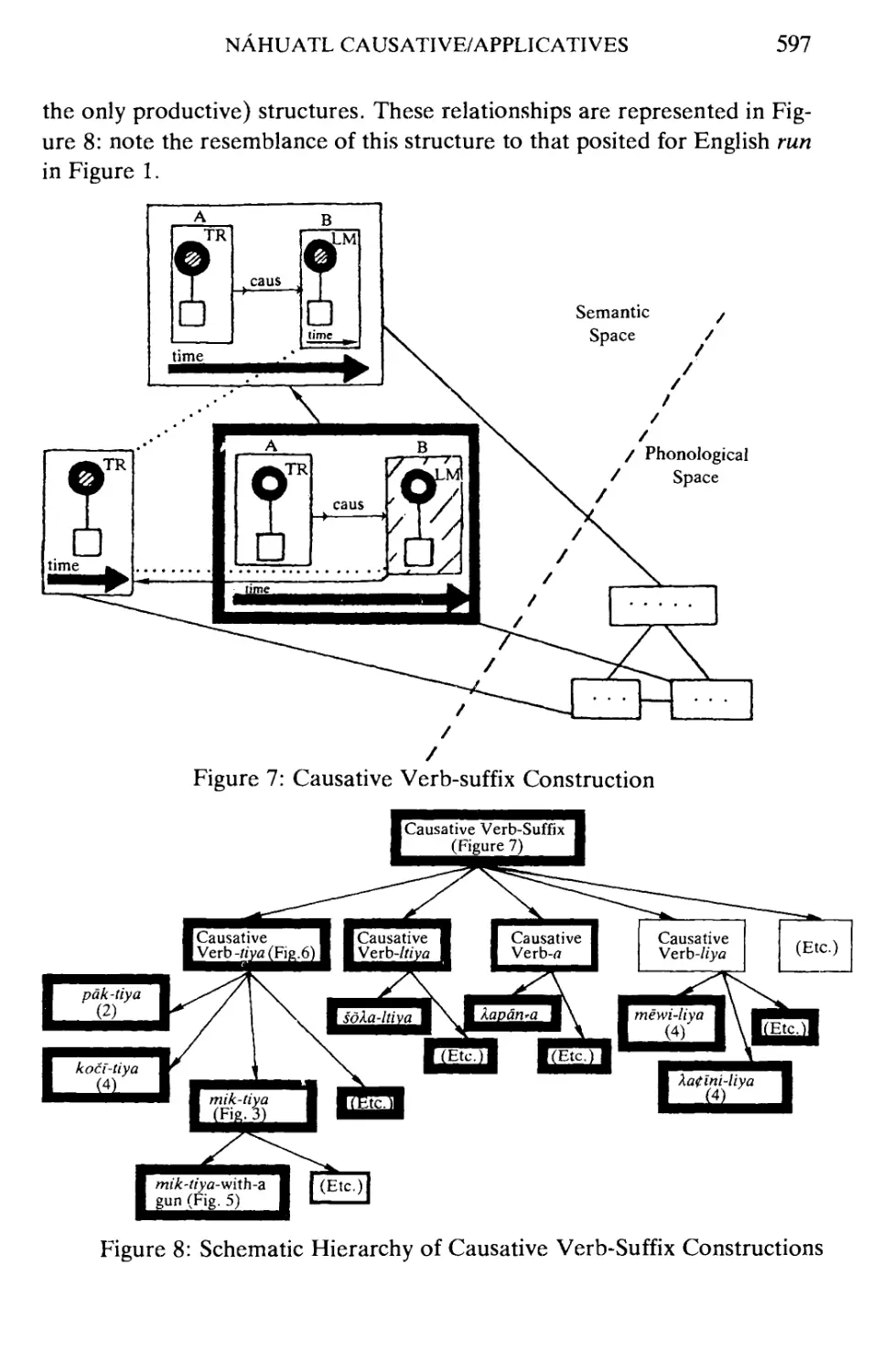

AMSTERDAM STUDIES IN THE THEORY AND

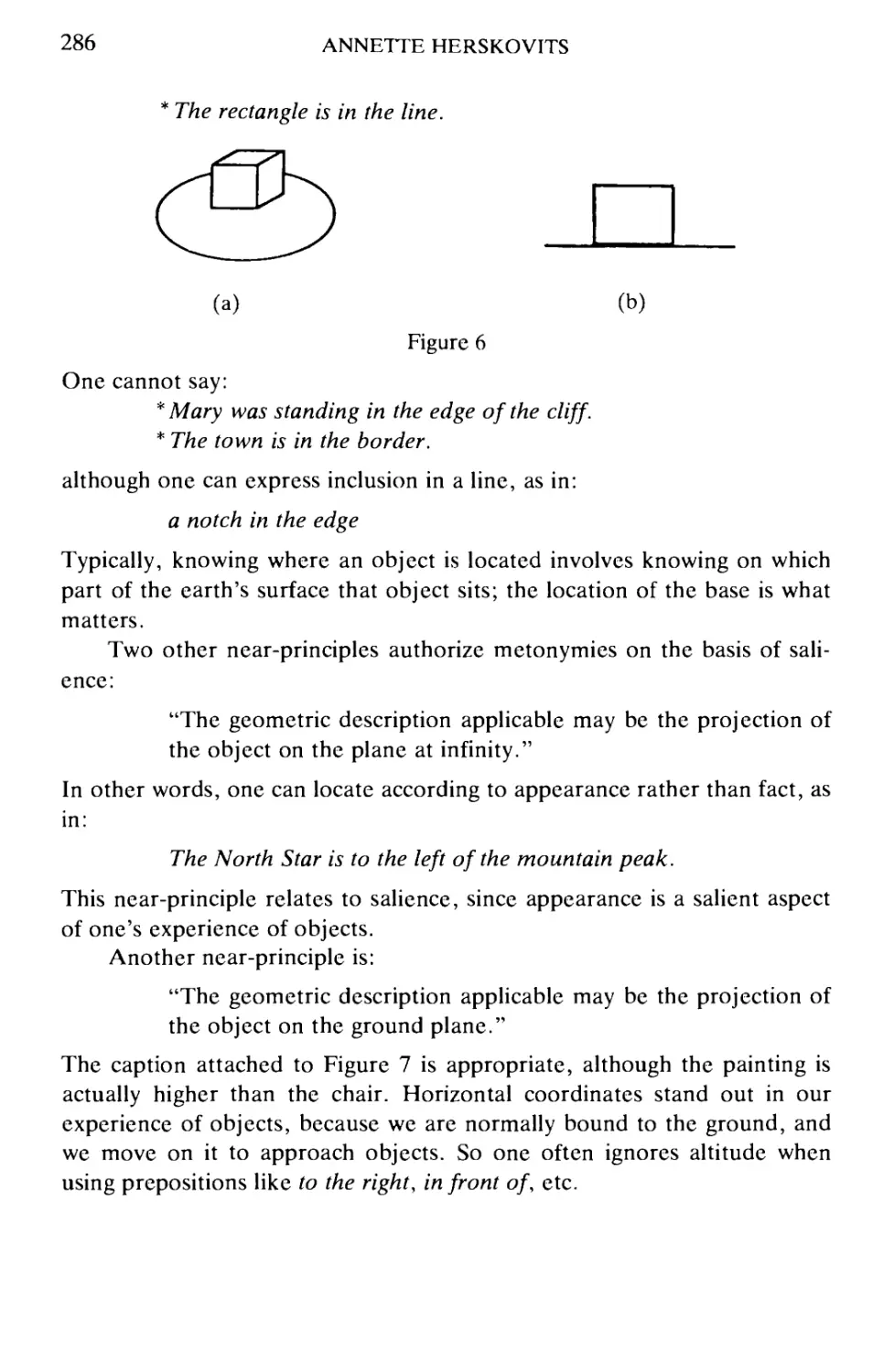

HISTORY OF LINGUISTIC SCIENCE

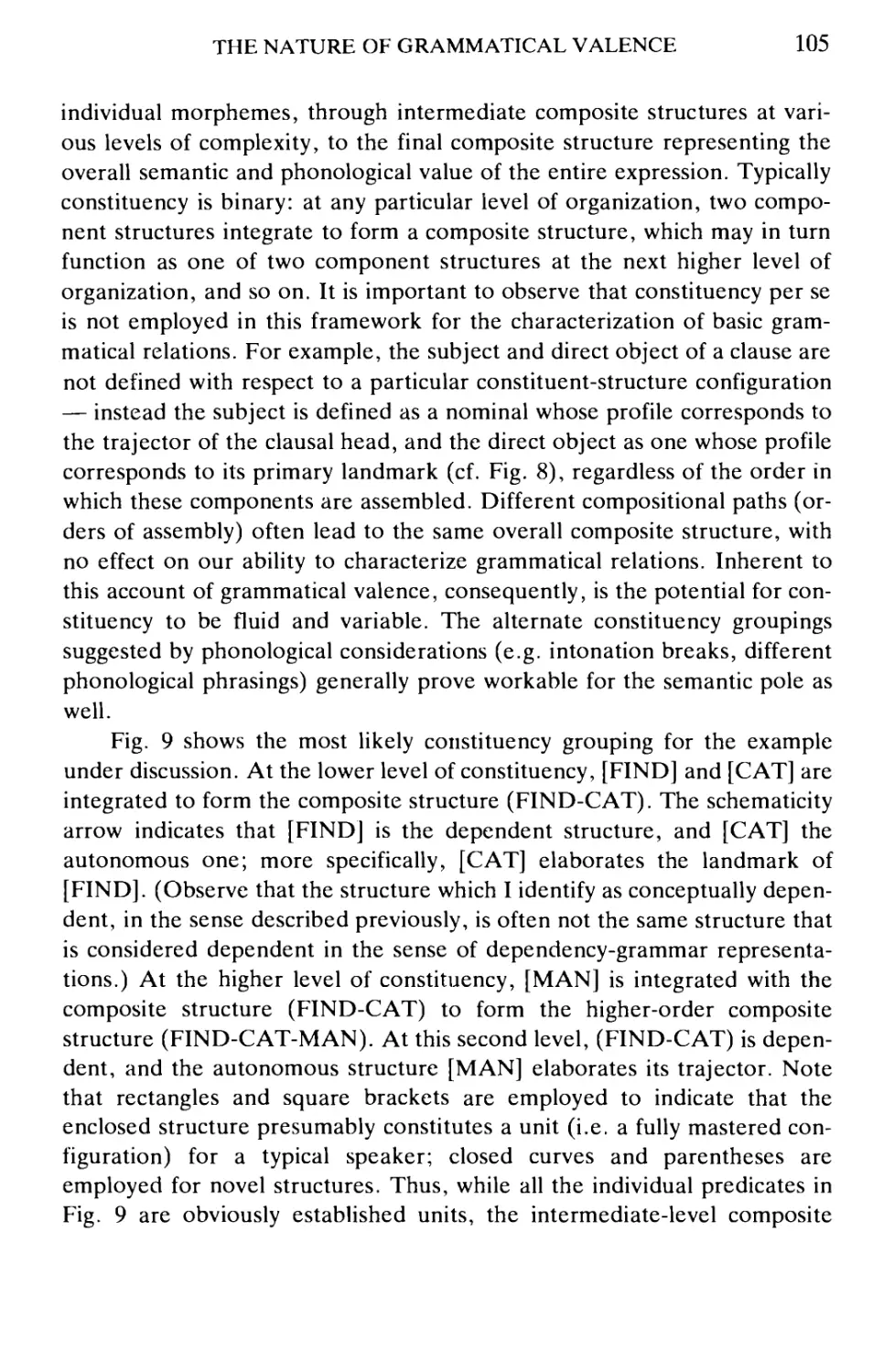

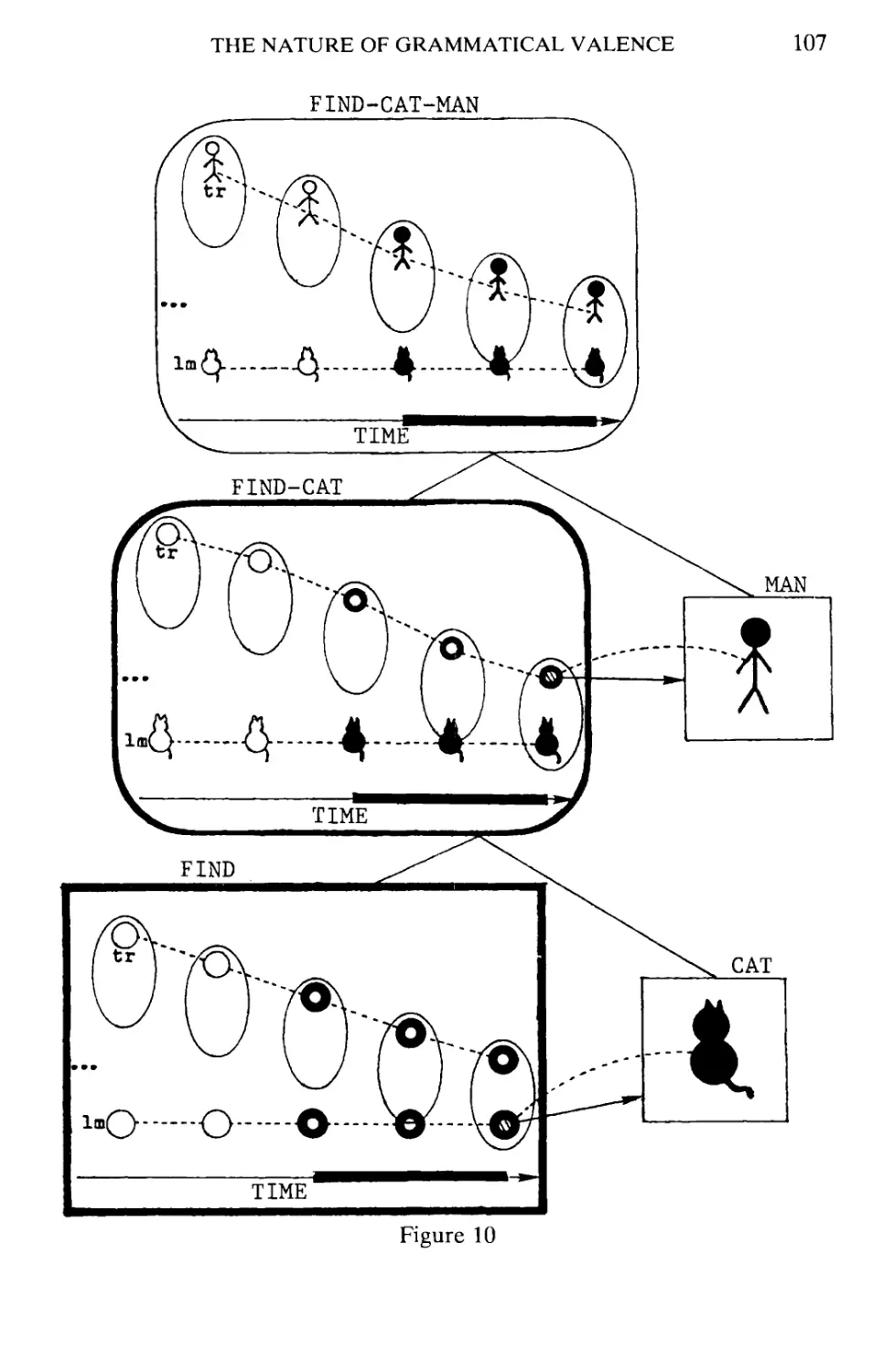

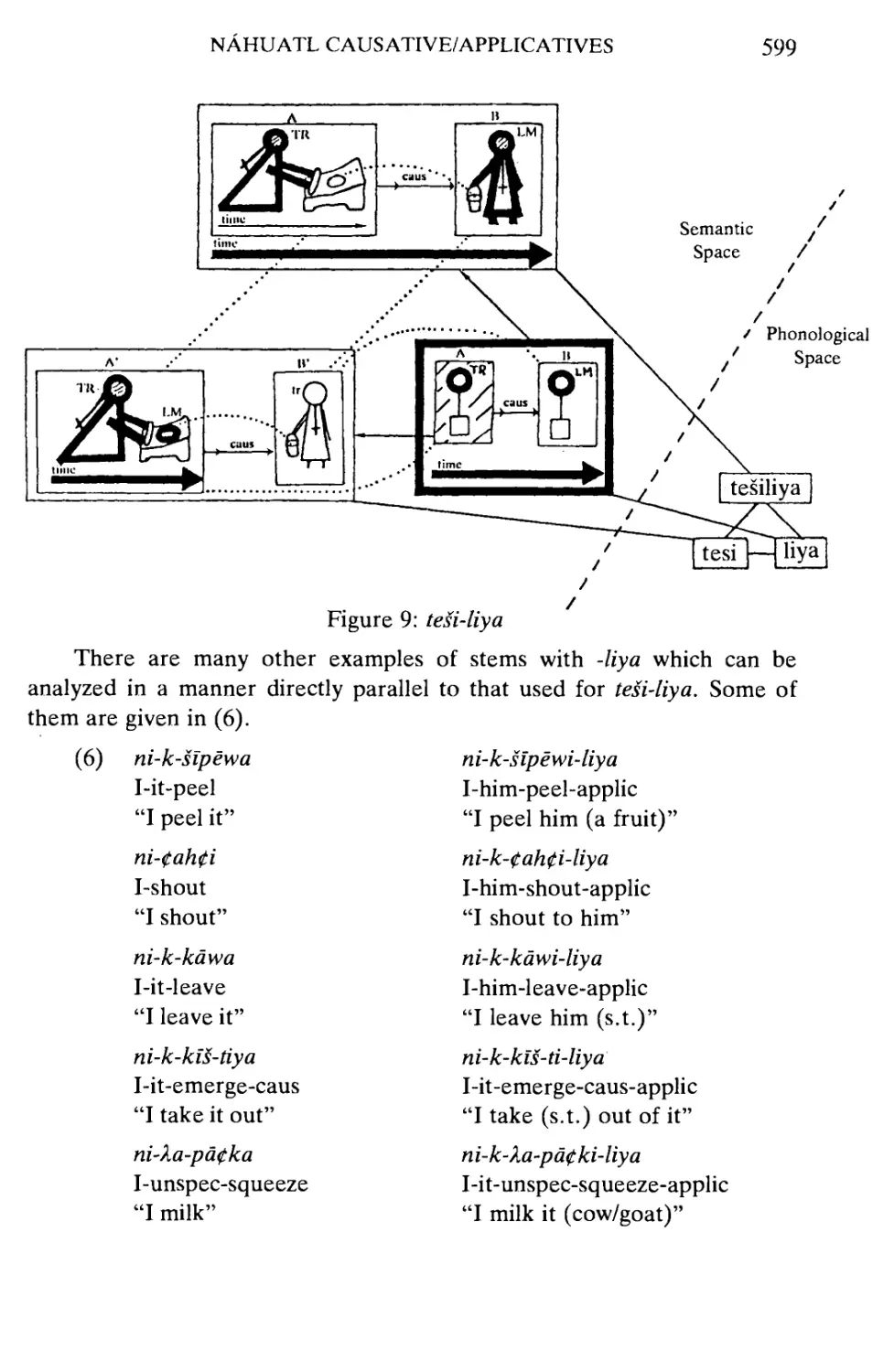

General Editor

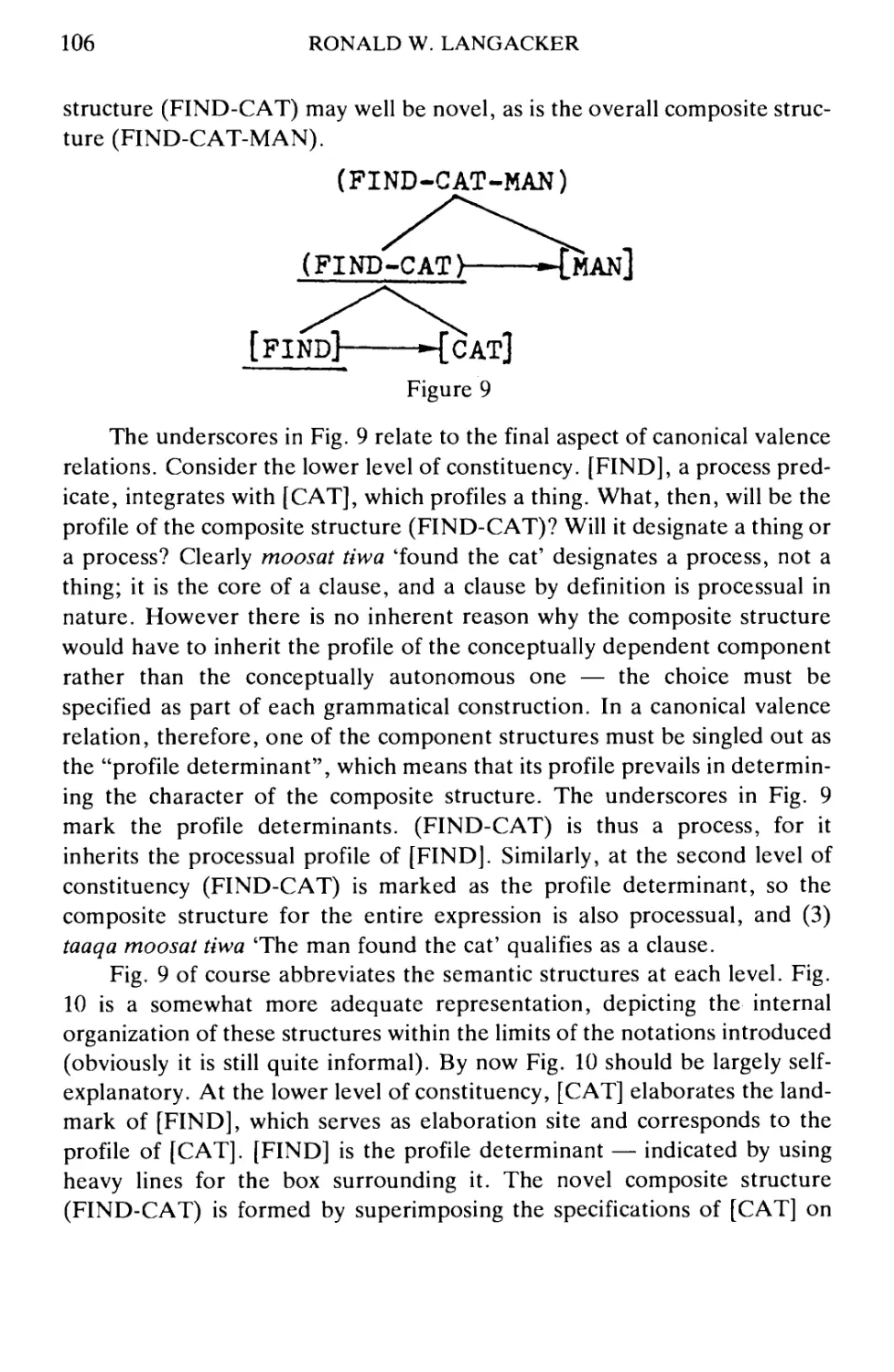

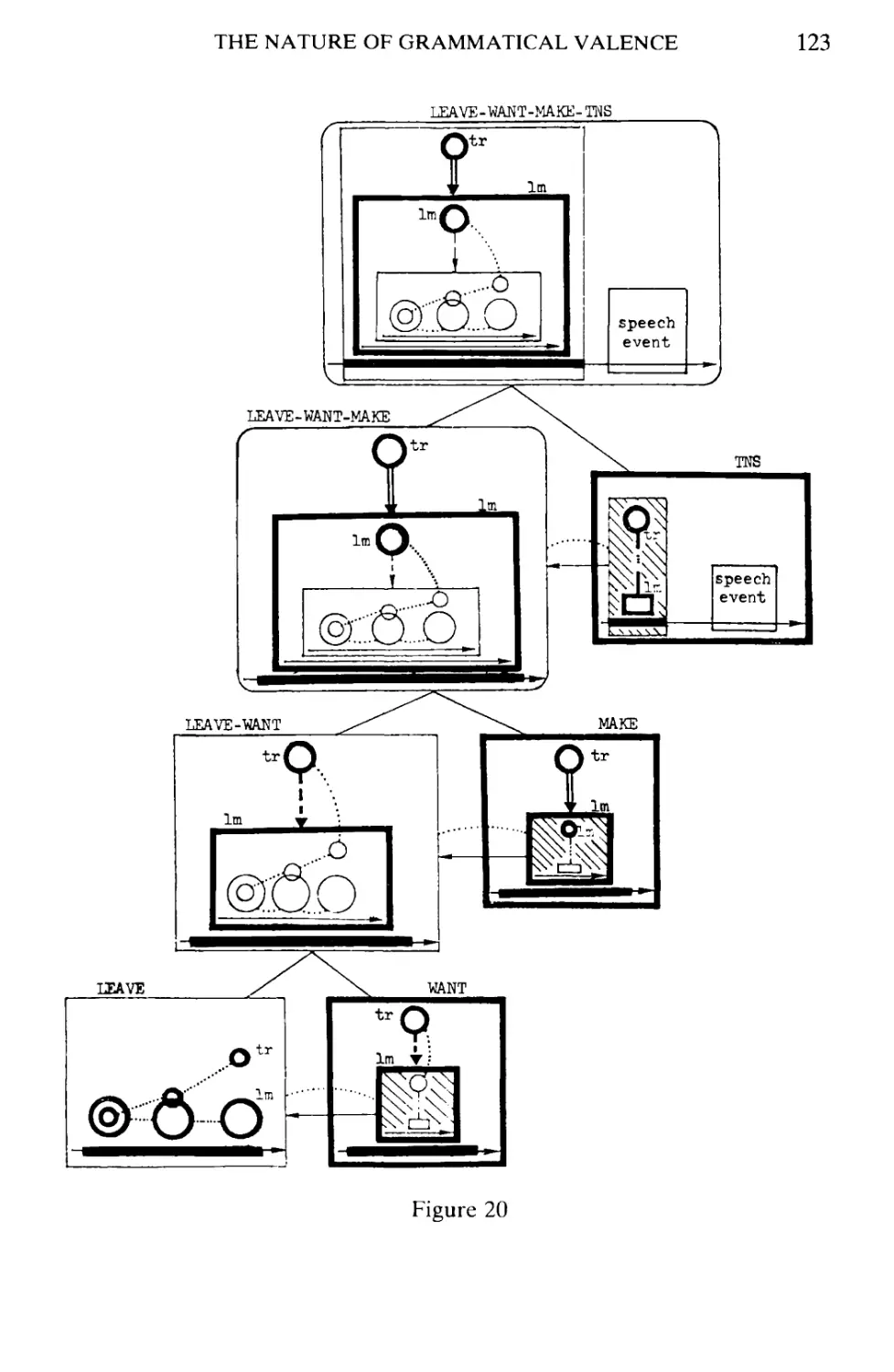

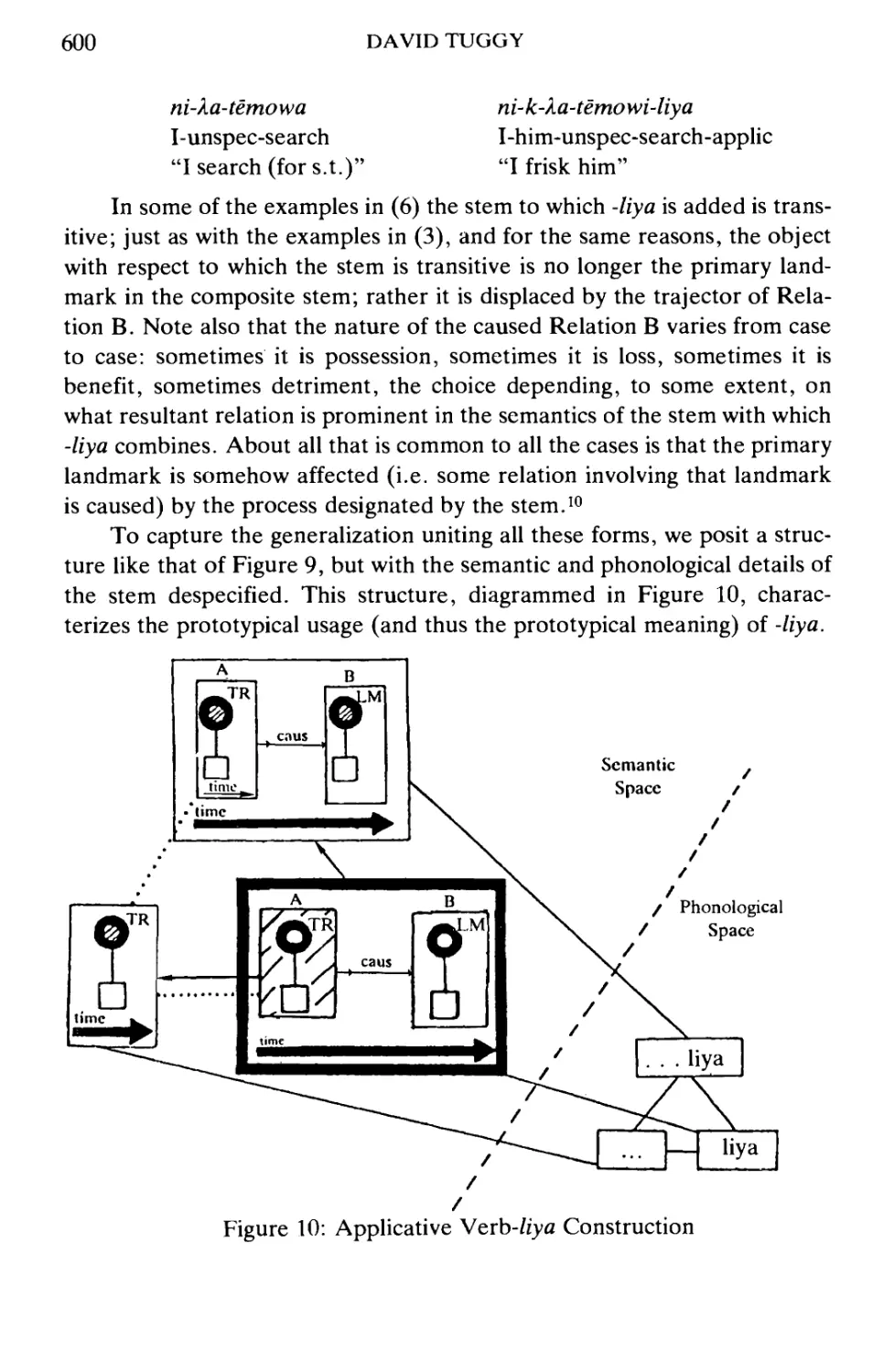

E.F. KONRAD KOERNER

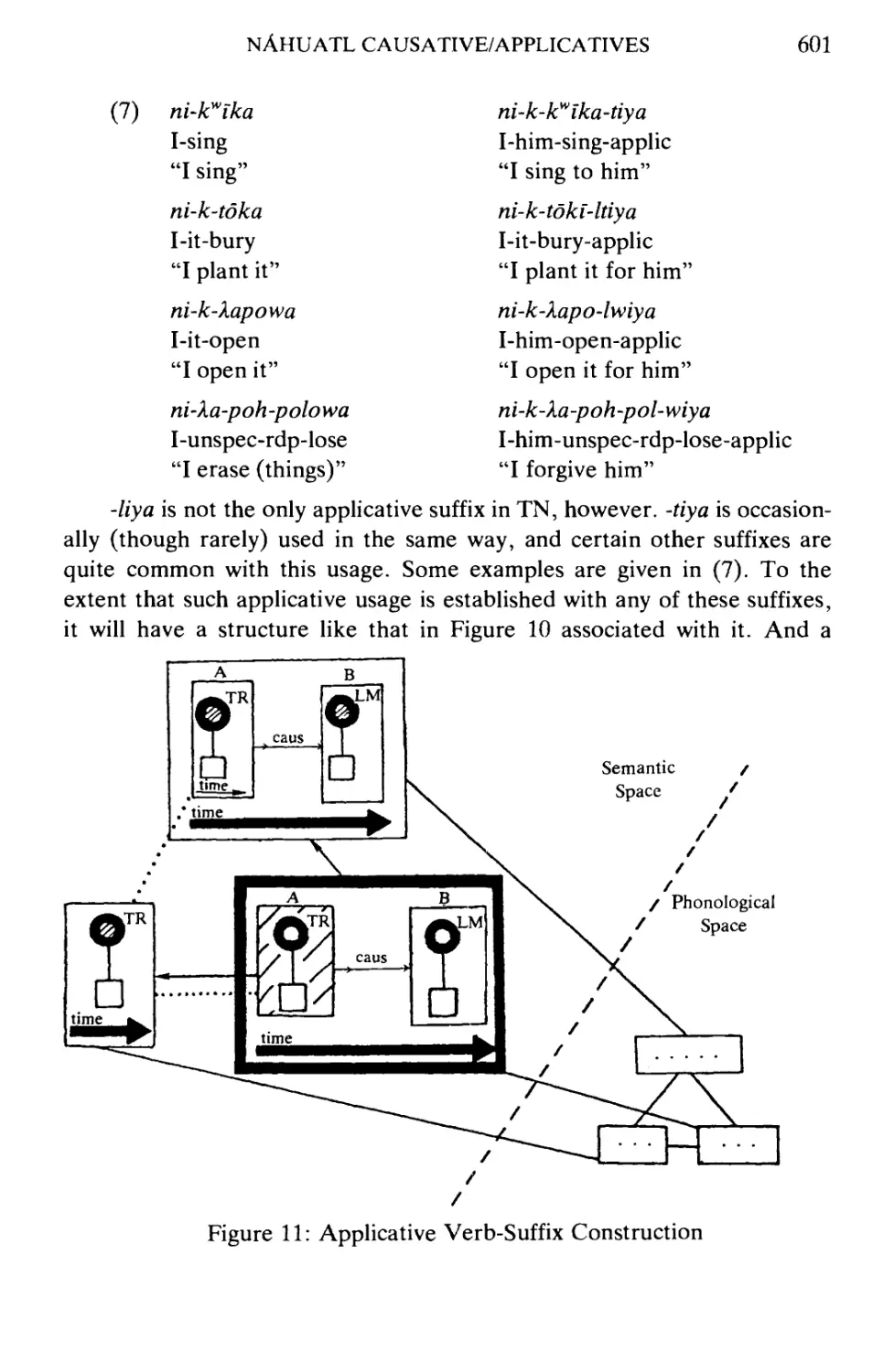

(University of Ottawa)

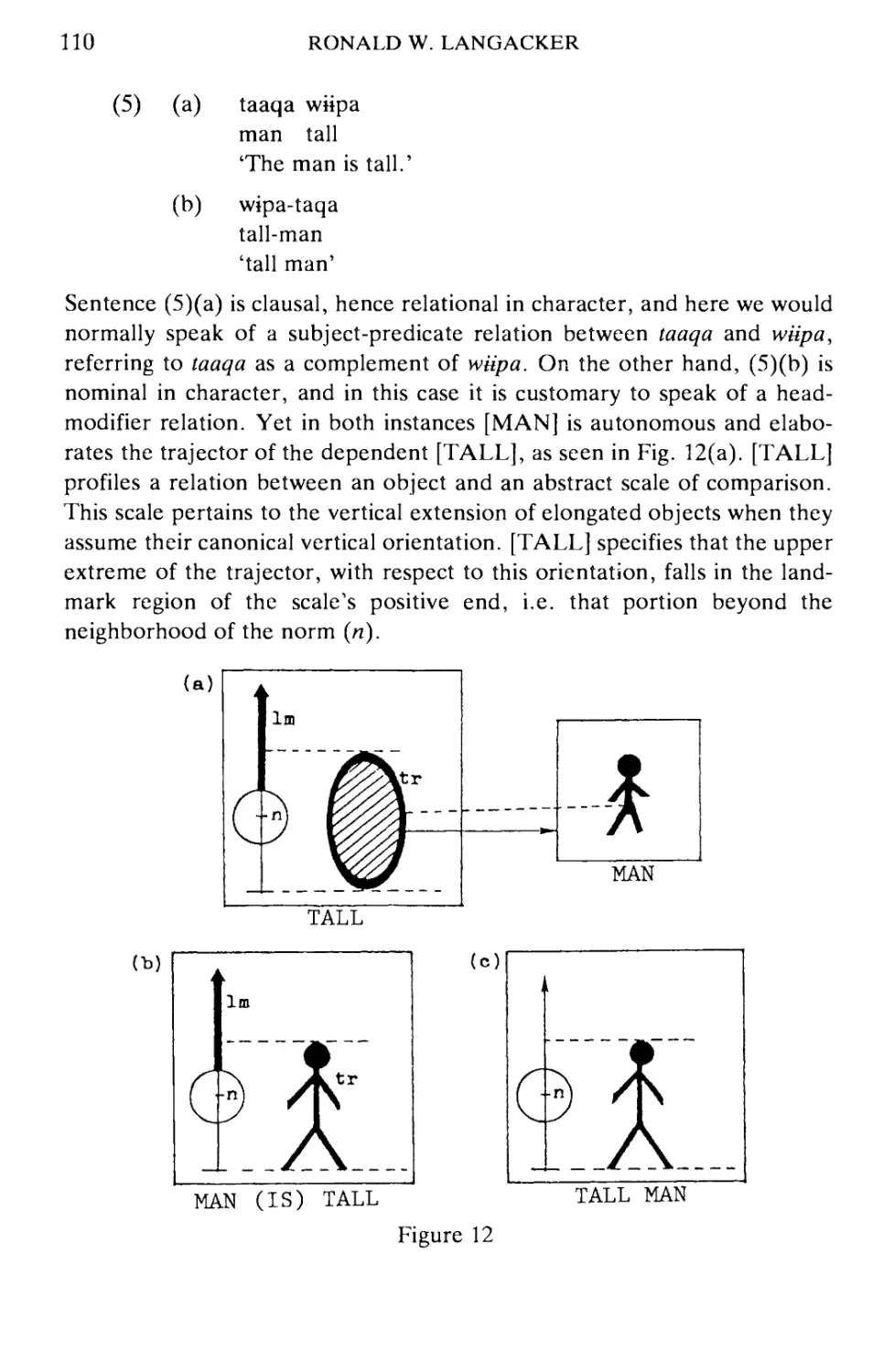

Series IV - CURRENT ISSUES IN LINGUISTIC THEORY

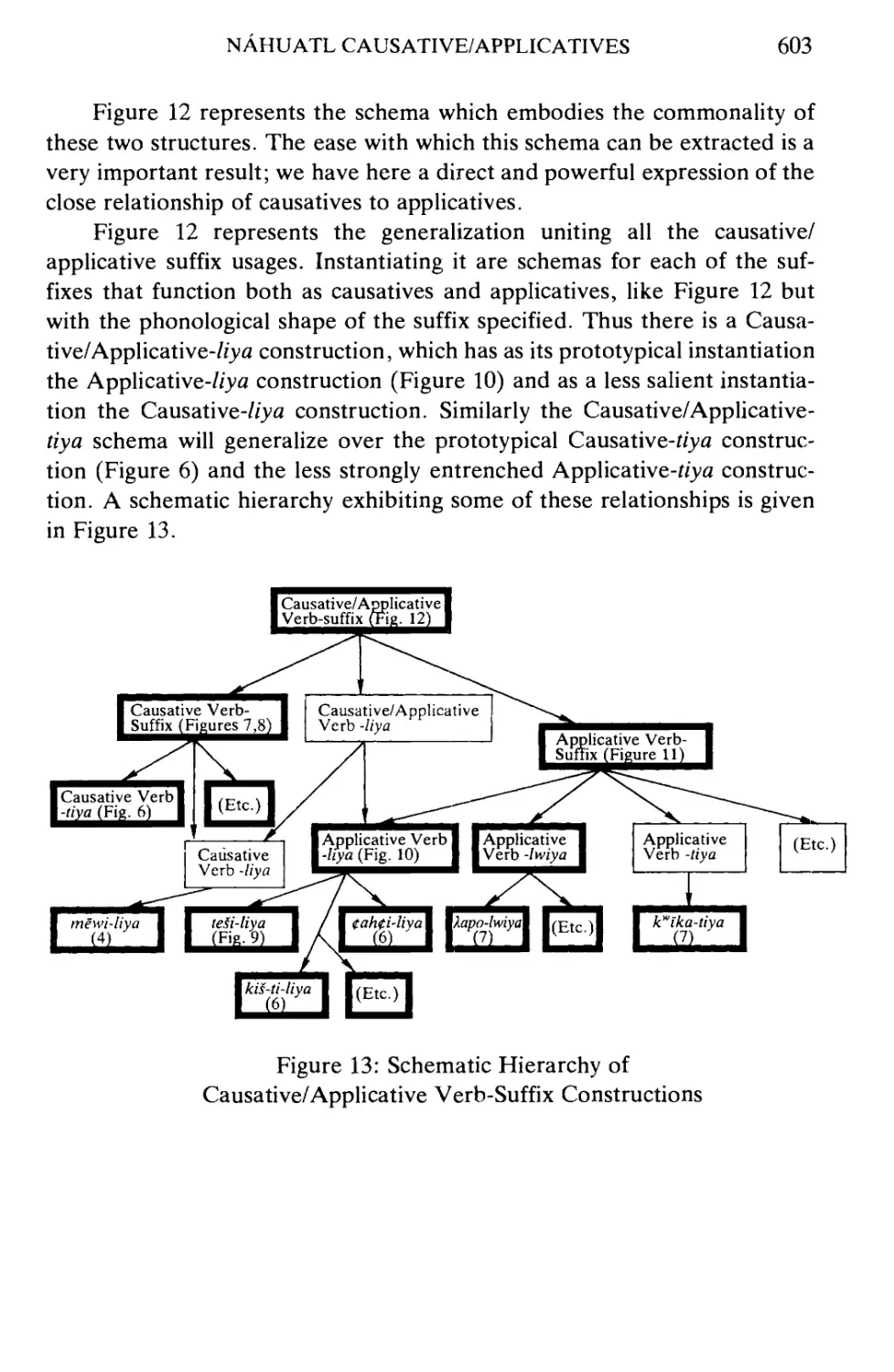

Advisory Editorial Board

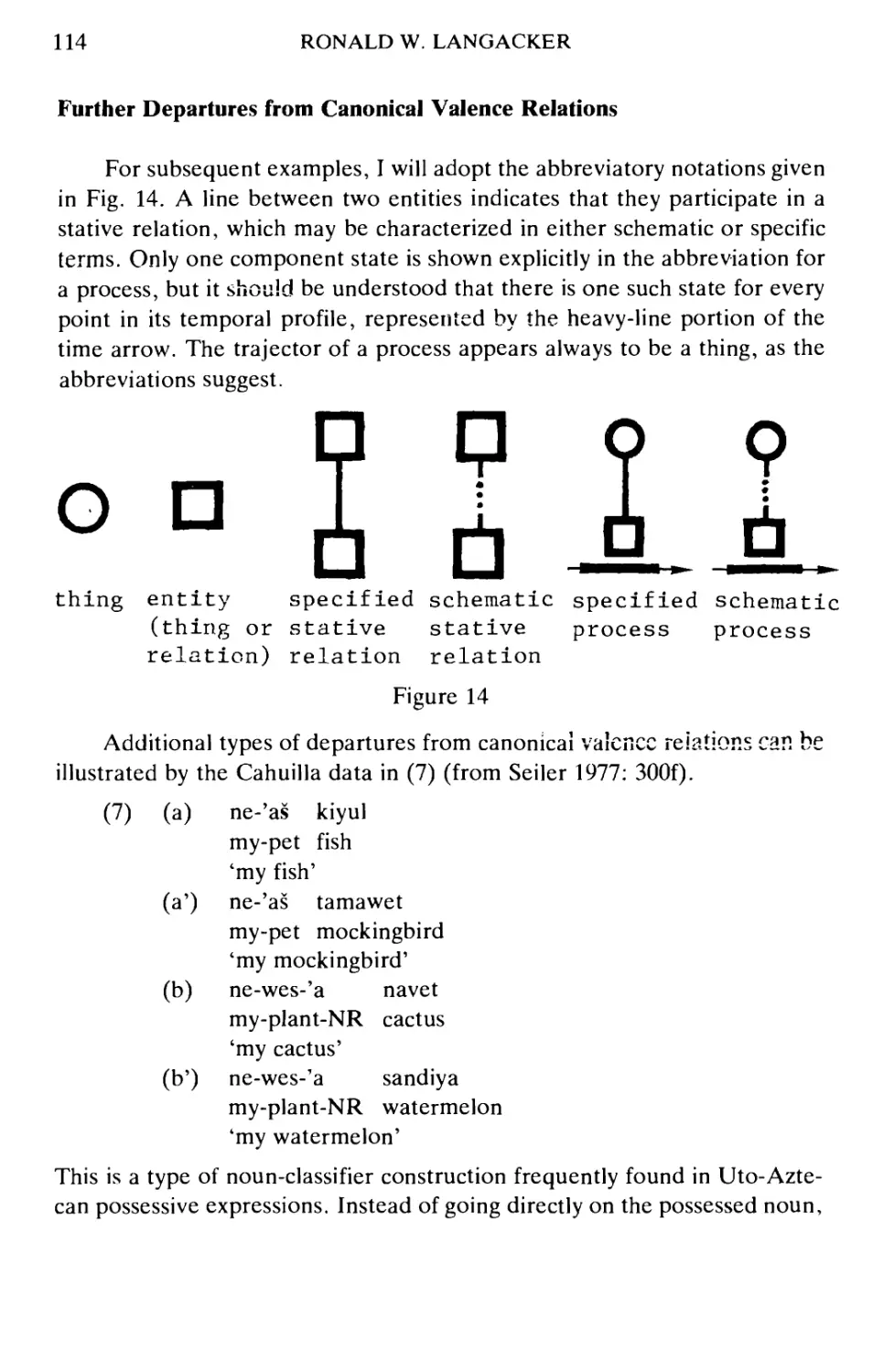

Henning Andersen (Buffalo, N.Y.); Raimo Anttila (Los Angeles)

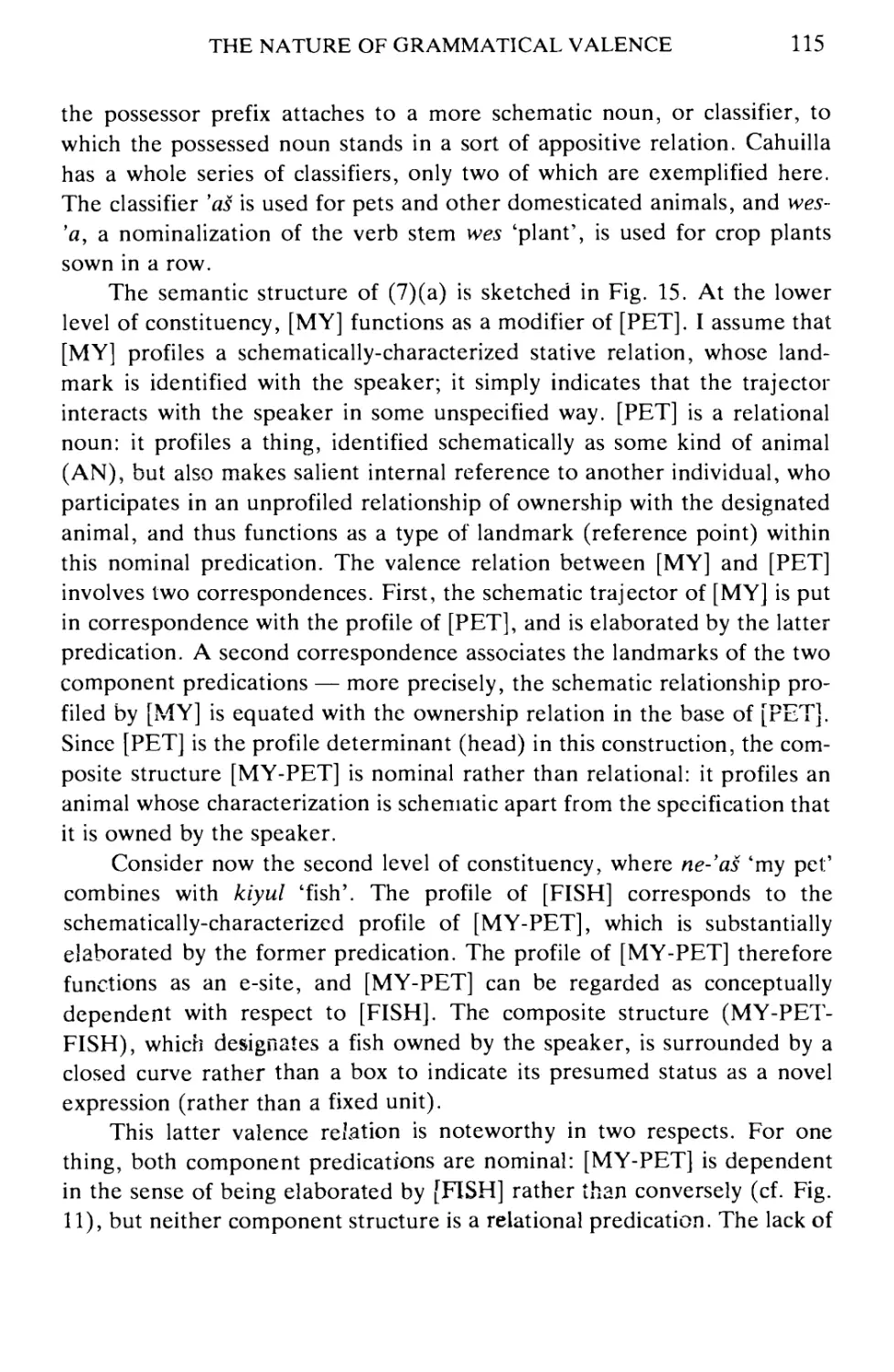

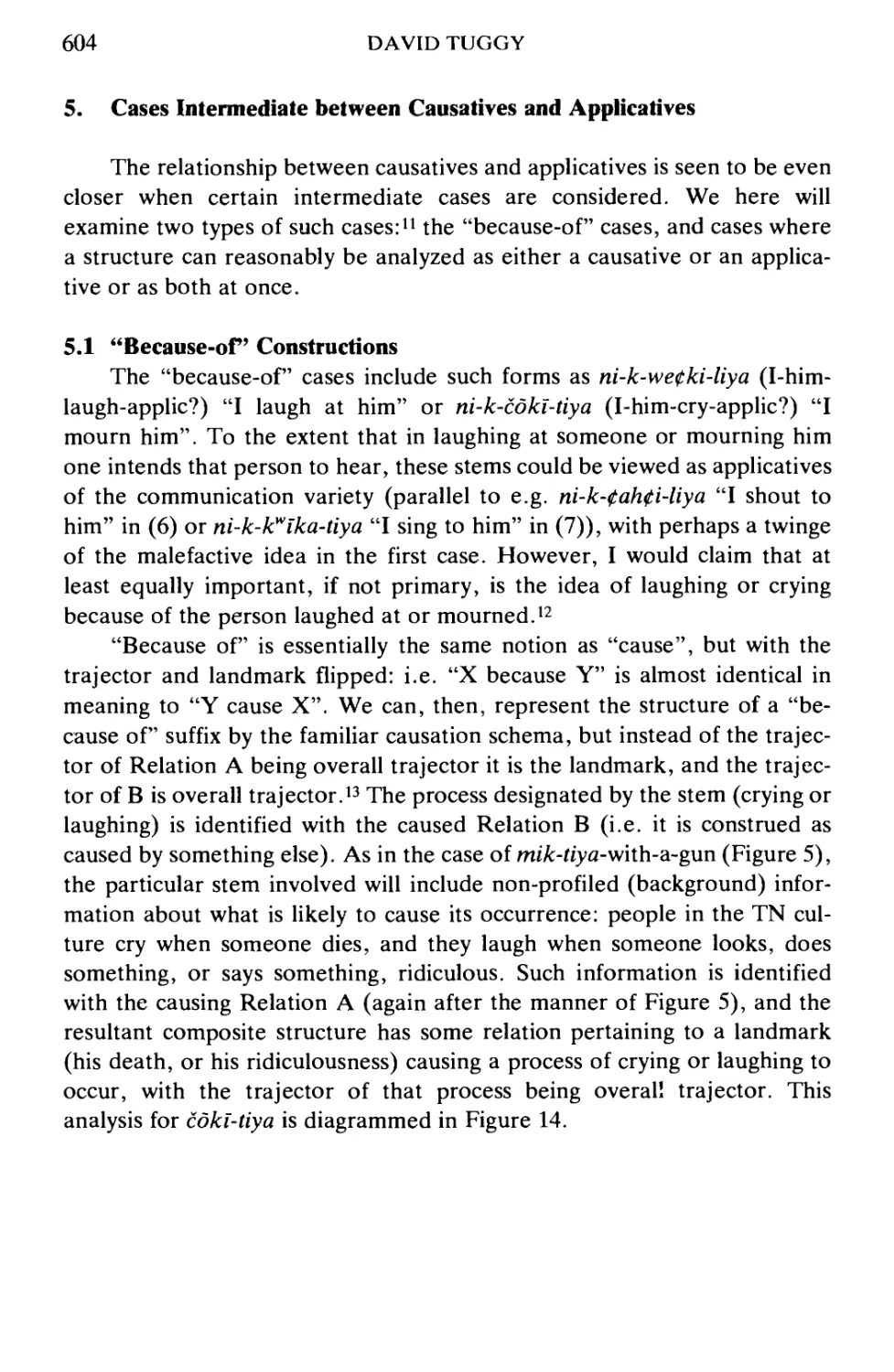

Thomas V. Gamkrelidze (Tbilisi); Hans-Heinrich Lieb (Berlin)

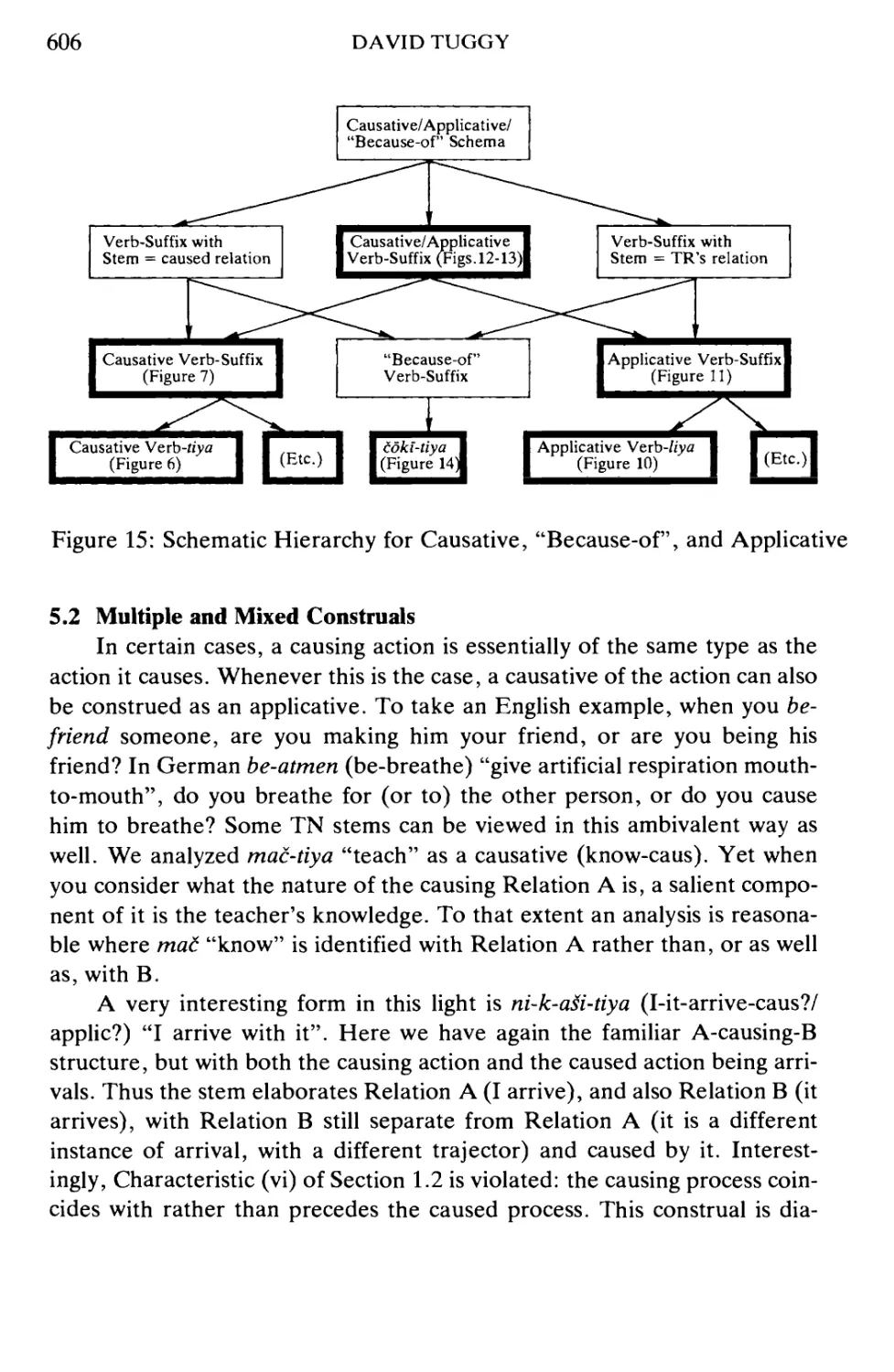

J. Peter Maher (Chicago); Ernst Pulgram (Ann Arbor, Mich.)

E.Wyn Roberts (Vancouver, B.C.); Danny Steinberg (Tokyo)

Volume 50

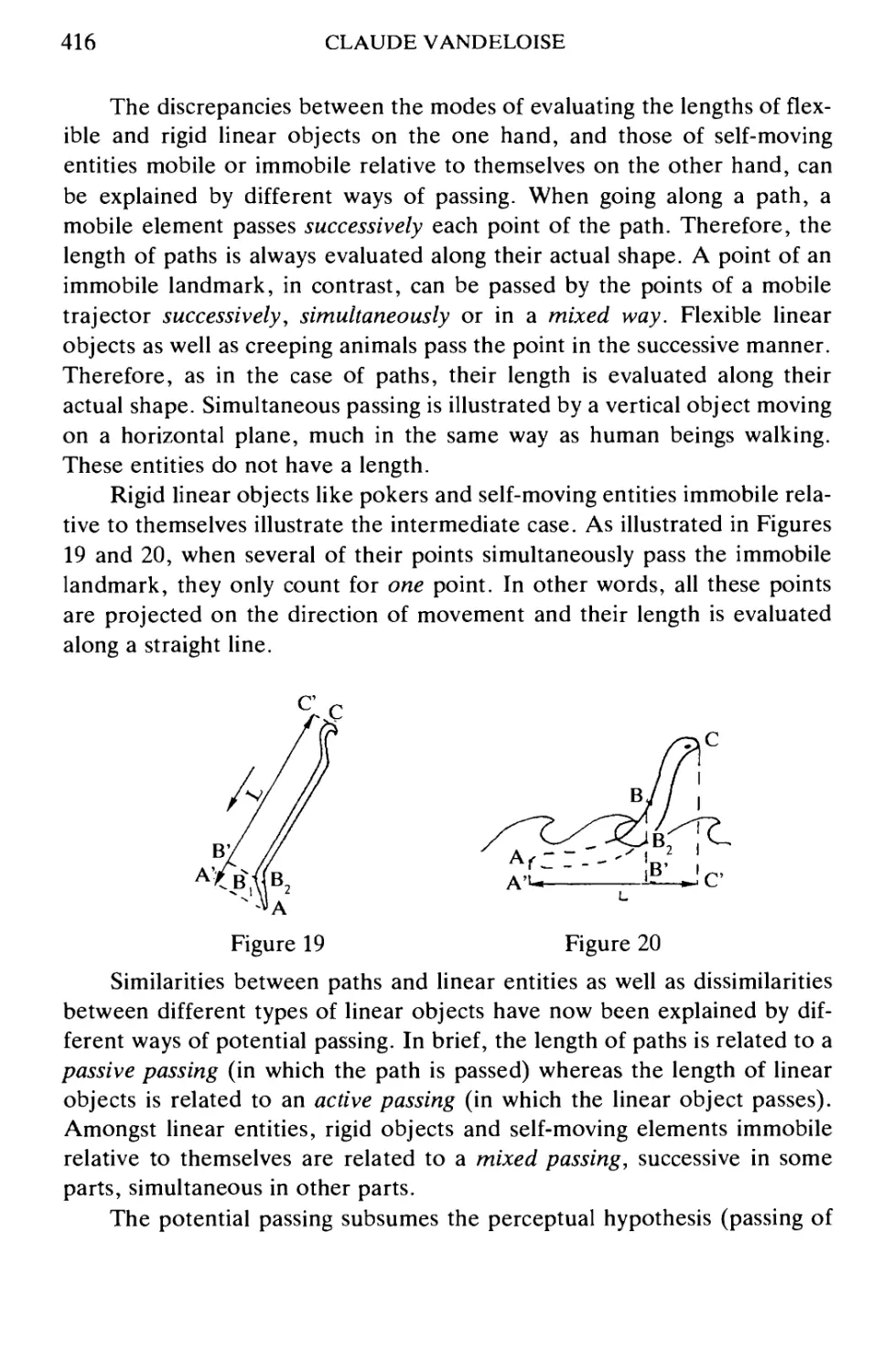

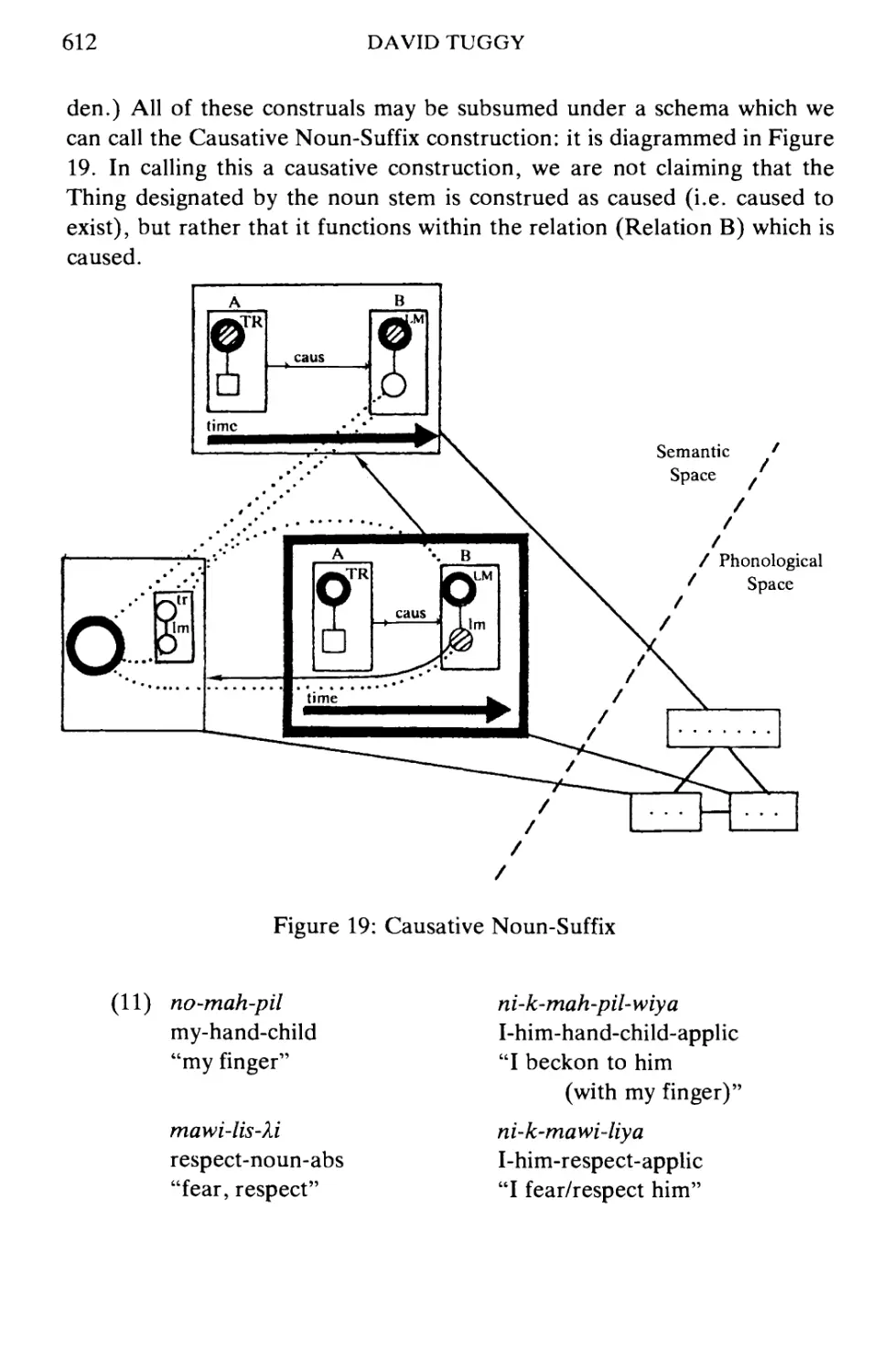

Brygida Rudzka-Ostyn (ed.)

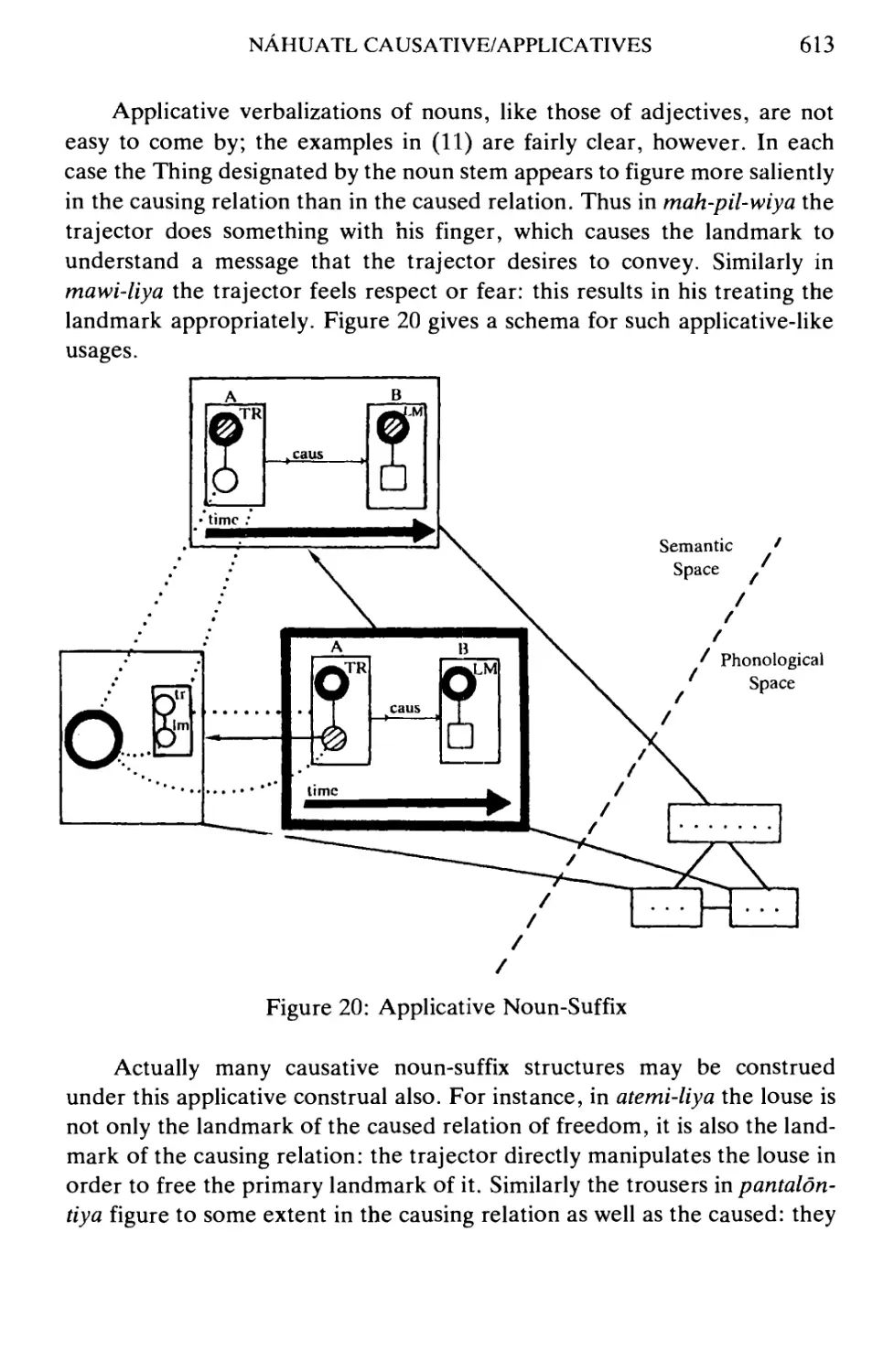

TOPICS IN COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS

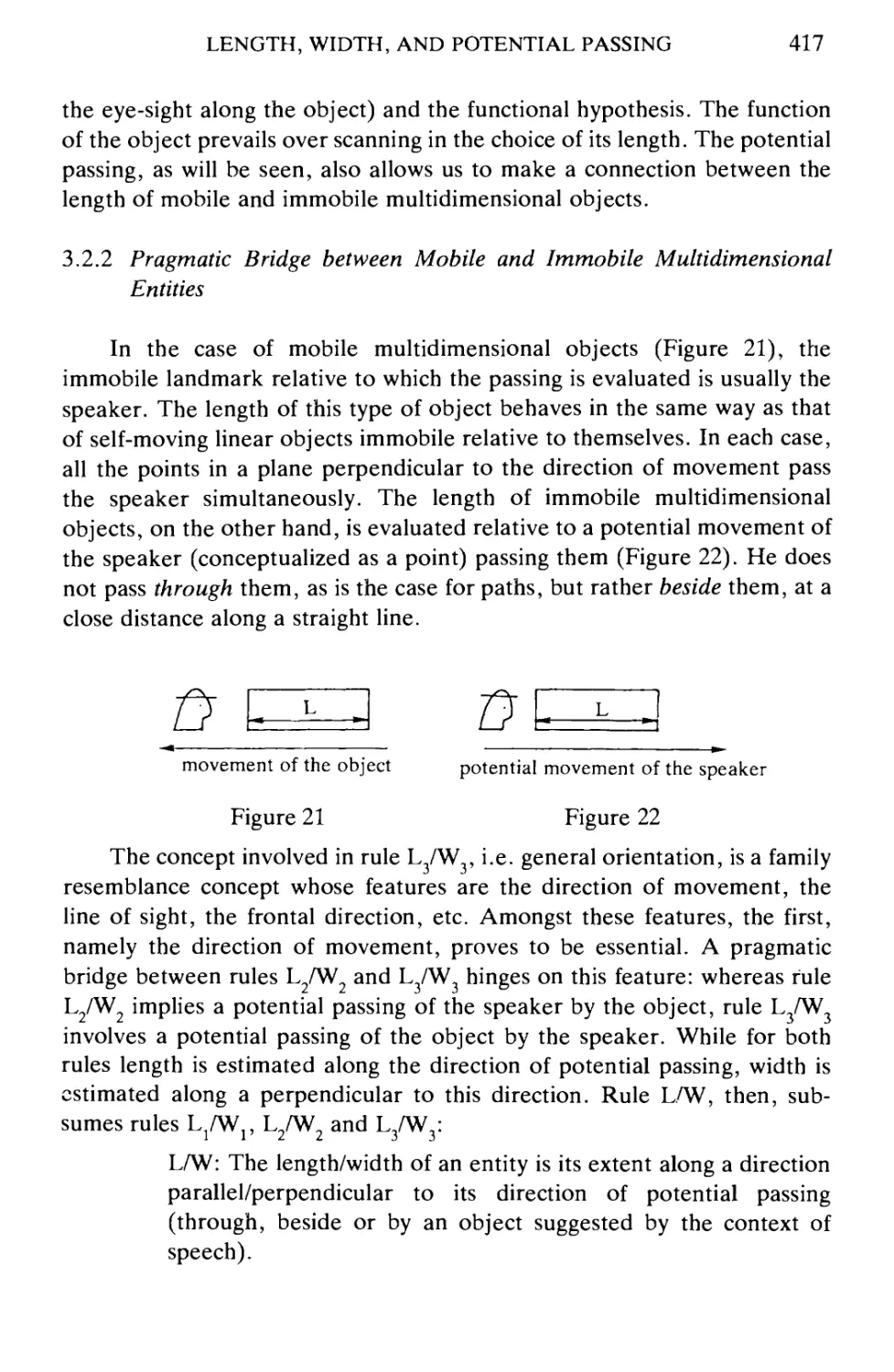

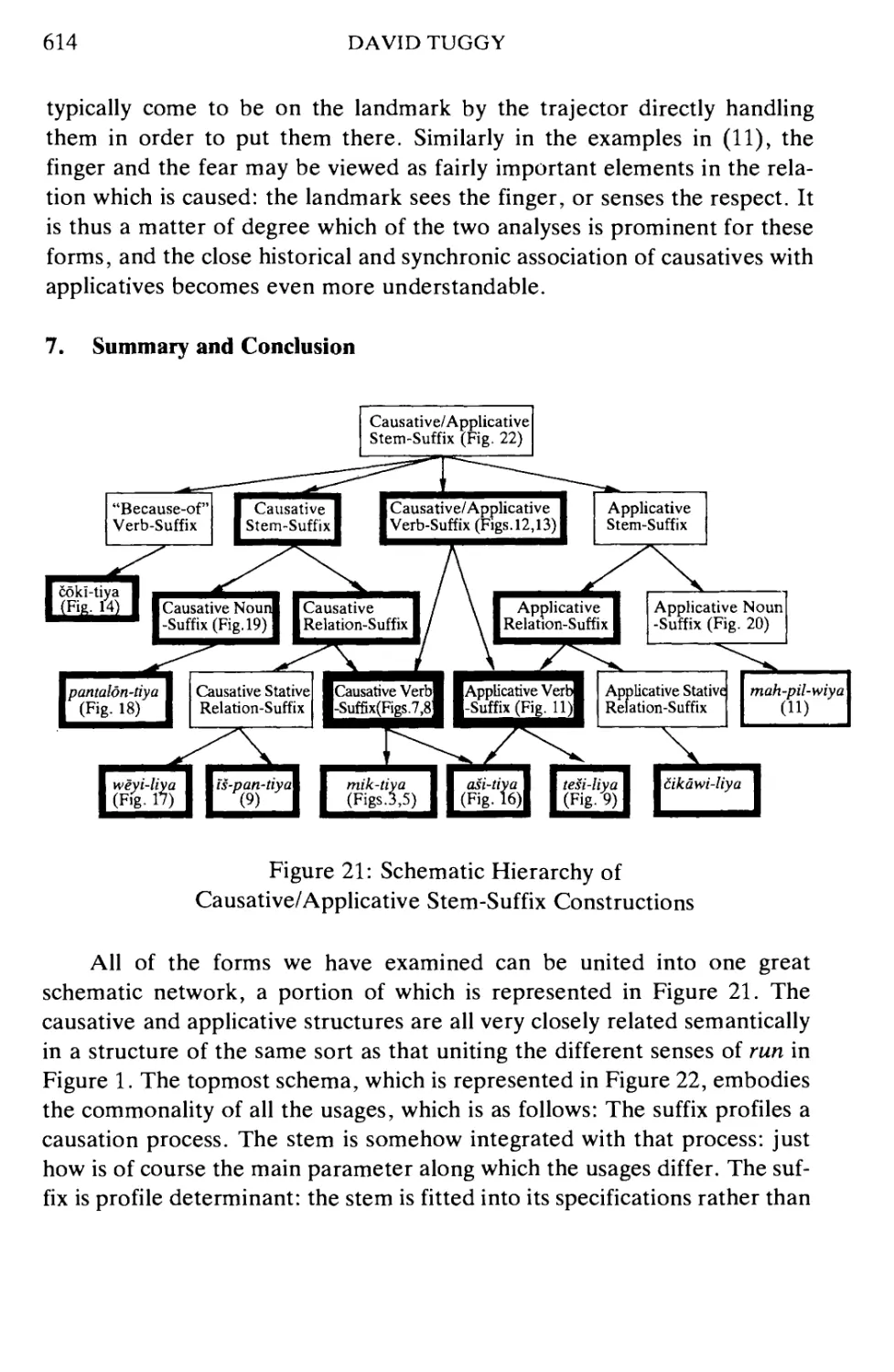

TOPICS IN

COGNITIVE LINGUISTICS

Edited by

BRYGIDA RUDZKA-OSTYN

University of Leuven

JOHN BENJAMINS PUBLISHING COMPANY

AMSTERDAM/PHILADELPHIA

1988

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Topics in cognitive linguistics / edited by Brygida Rudzka-Ostyn

p. cm. — (Amsterdam studies in the theory and history of linguistic science.

Series IV, Current issues in linguistic theory, ISSN 0304-0763; v. 50)

Bibliography: p.

Includes index.

1. Cognitive grammar. I. Rudzka-Ostyn, Brygida. II. Series.

P165.T65 1988

415--de 19 87-37495

ISBN 90 272 3544 9 (alk. paper) CIP

© Copyright 1988 - All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or

any other means, without written permission of the copyright holders. Please direct all

enquiries to the publishers.

To the memory of my mother

Contents

Preface ix

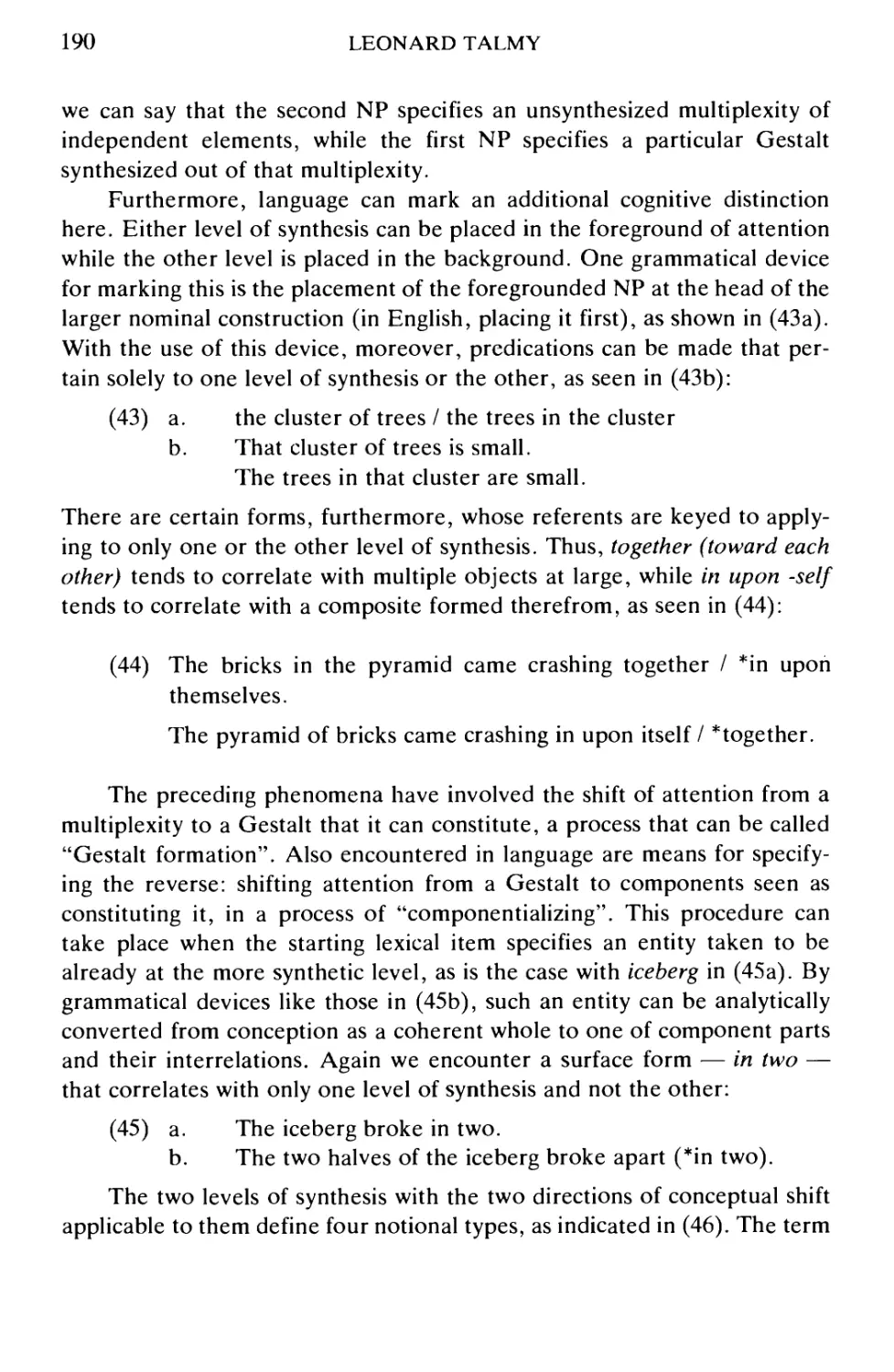

I. Toward a Coherent and Comprehensive Linguistic Theory

An Overview of Cognitive Grammar

Ronald W. Langacker

A View of Linguistic Semantics

Ronald W. Langacker

The Nature of Grammatical Valence

Ronald W. Langacker

A Usage-Based Model

Ronald W. Langacker

II. Aspects of a Multifaceted Research Program

The Relation of Grammar to Cognition

Leonard Talmy

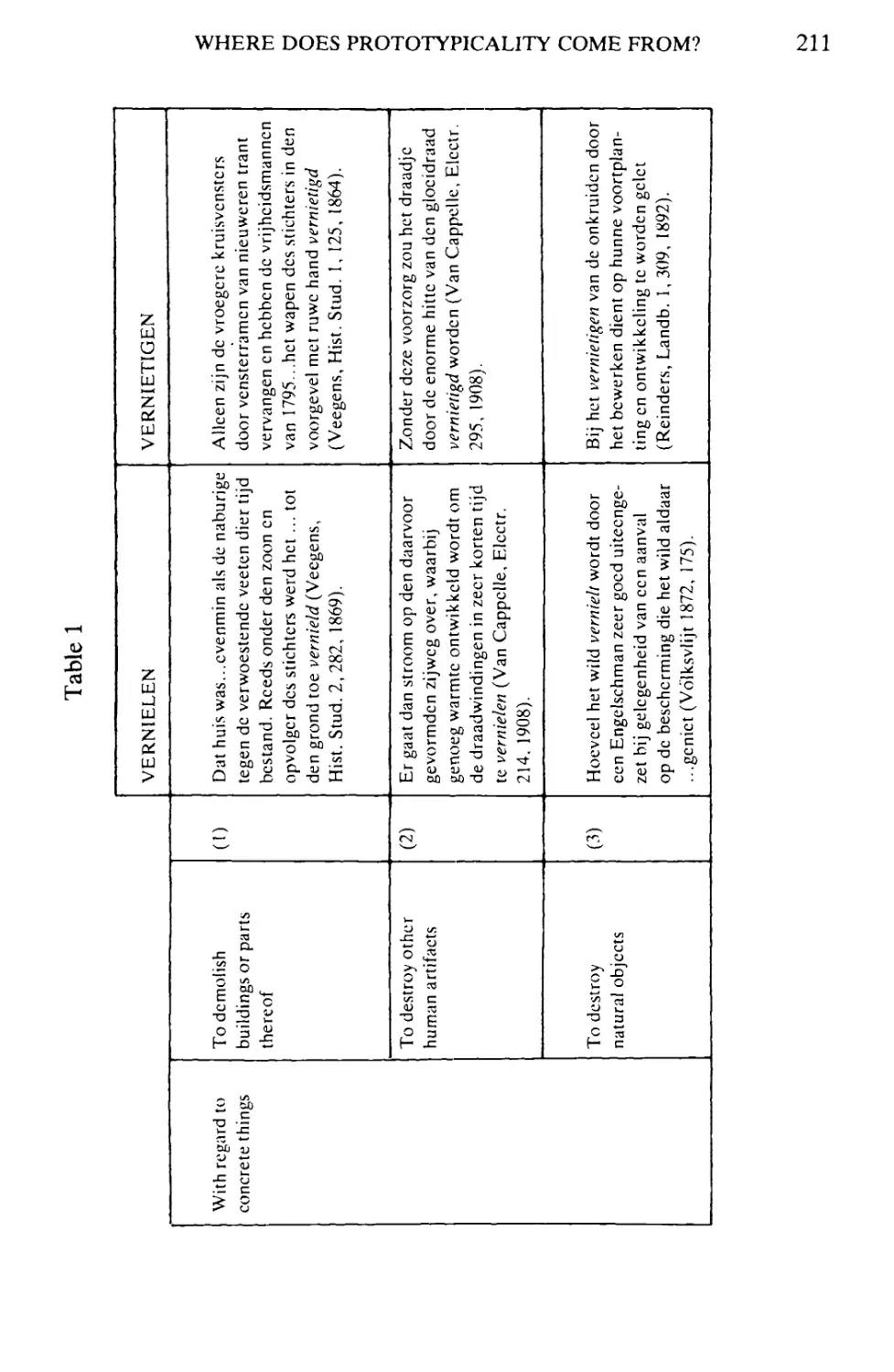

Where Does Prototypicality Come From?

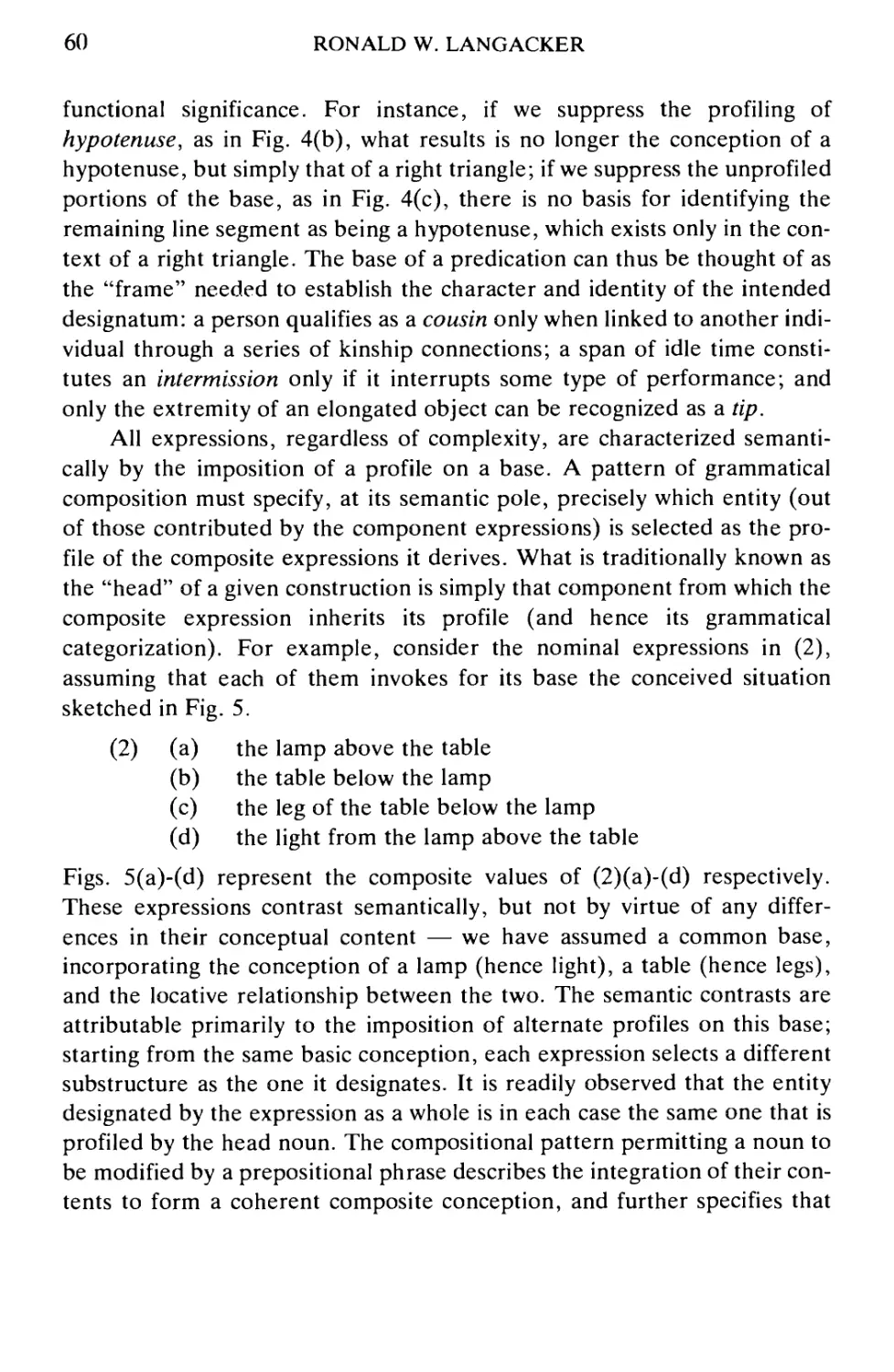

Dirk Geeraerts

The Natural Category MEDIUM: An Alternative to Selection

Restrictions and Similar Constructs 231

Bruce W. Hawkins

Spatial Expressions and the Plasticity of Meaning 271

Annette Herskovits

Contrasting Prepositional Categories: English and Italian 299

John R. Taylor

The Mapping of Elements of Cognitive Space onto Grammatical

Relations: An Example from Russian Verbal Prefixation 327

Laura A. Janda

3

49

91

127

165

207

Vlll

CONTENTS

Conventionalization of Cora Locationals 345

Eugene H. Casad

The Conceptualisation of Vertical Space in English: The Case of Tall 379

Rene Dirven and John R. Taylor

Length, Width, and Potential Passing 403

Claude Vandeloise

On Bounding in Ik 429

Fritz Serzisko

A Discourse Perspective on Tense and Aspect in Standard Modern

Greek and English 447

Wolf Paprotte

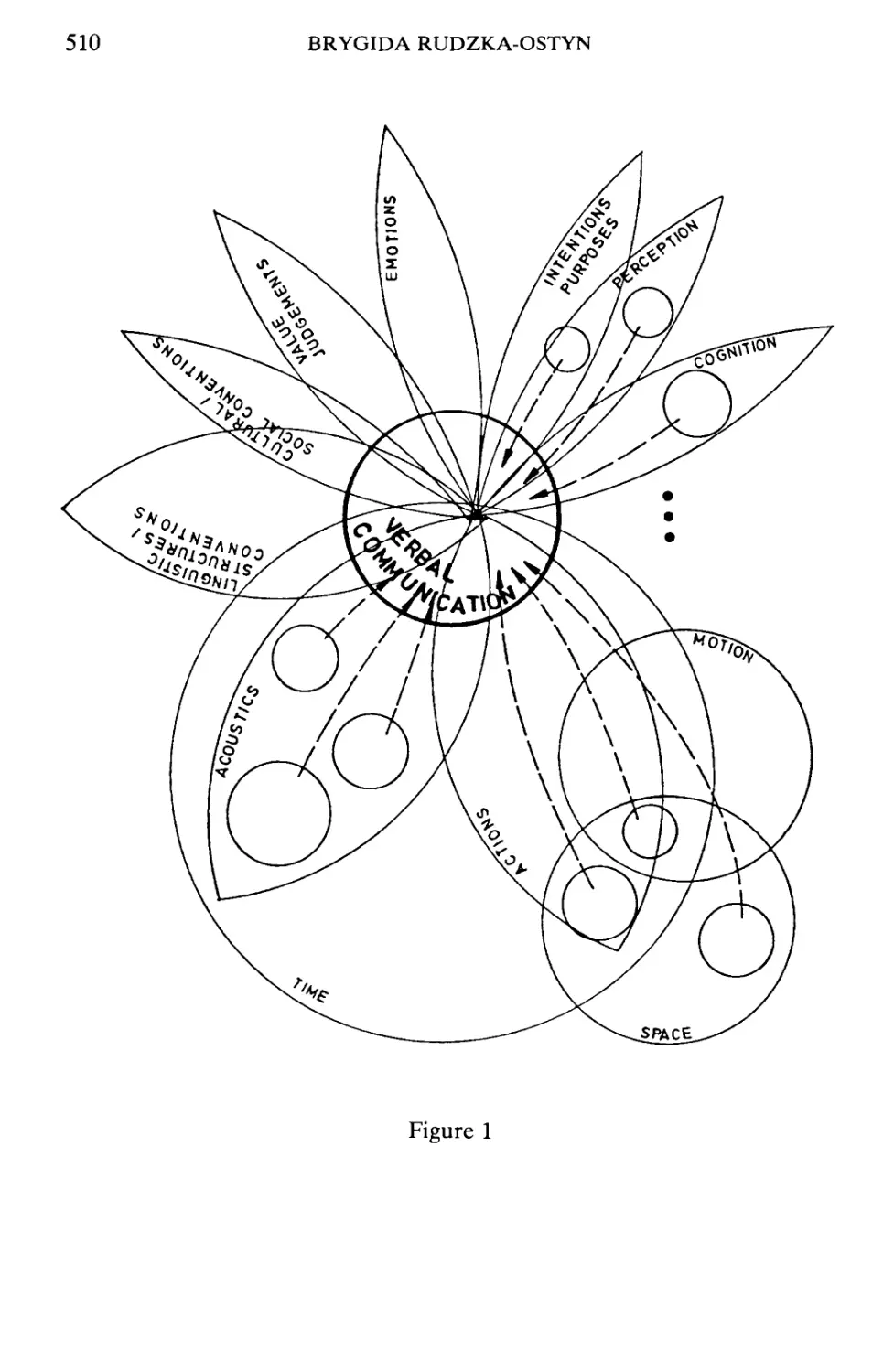

Semantic Extensions into the Domain of Verbal Communication 507

Brygida Rudzka-Ostyn

Spatial Metaphor in German Causative Constructions 555

Robert Thomas King

Nahuatl Causative/Applicatives in Cognitive Grammar 587

David Tuggy

III. A Historical Perspective

Grammatical Categories and Human Conceptualization:

Aristotle and the Modistae 621

Pierre Swiggers

Cognitive Grammar and the History of Lexical Semantics 647

Dirk Geeraerts

References 679

Subject Index 695

Preface

Recent years have witnessed a growing interest in cognitive linguistics,

a framework aiming at an adequate account of the relationship between

language and cognition and as such involving human psychology,

interpersonal relations, culture, and a host of other domains. Our purpose has been

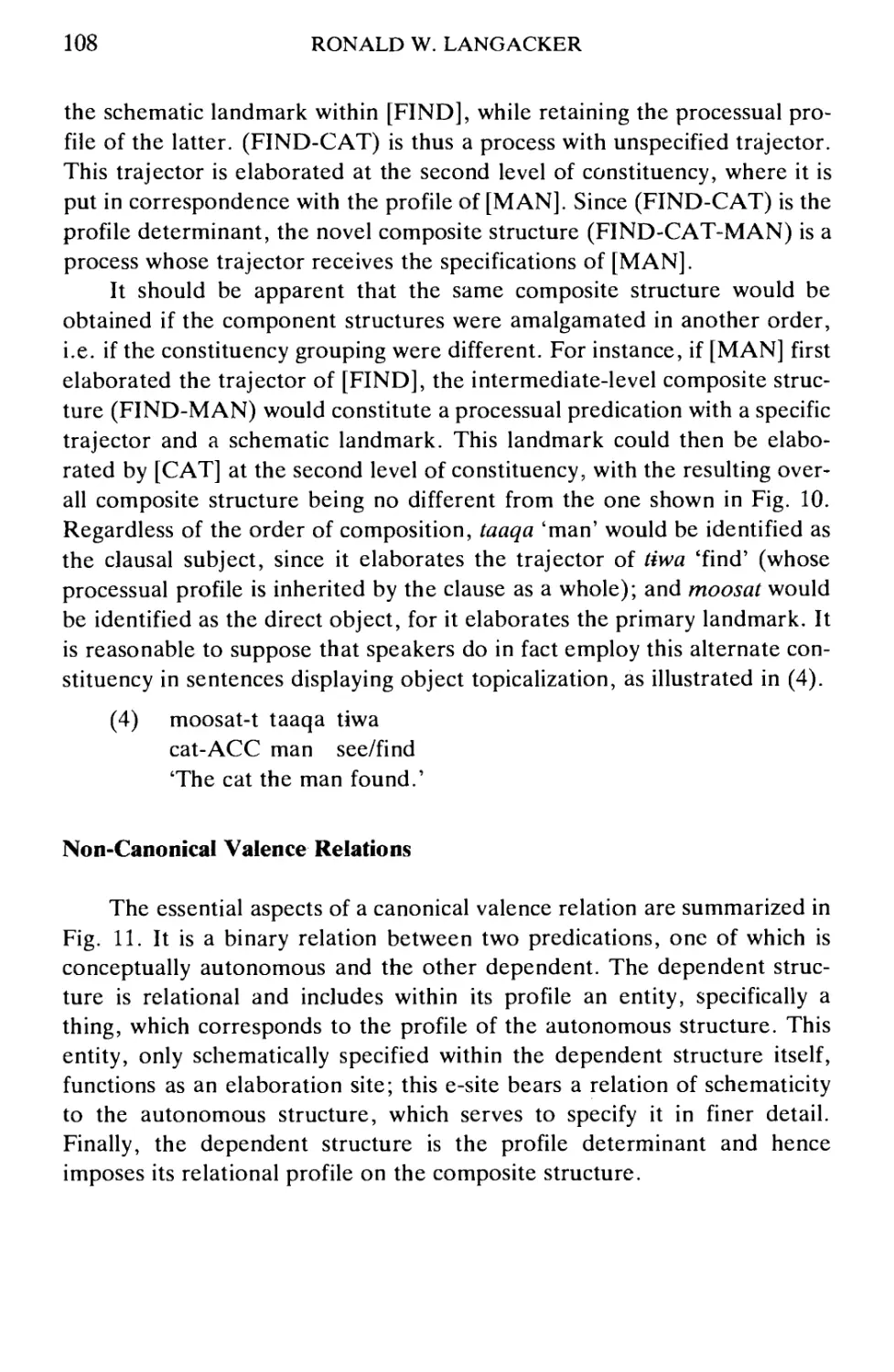

to present the theoretical premises of this framework and to explore its

descriptive and explanatory potential with respect to a wide range of

language phenomena. In pursuing this goal, we have frequently relied on

corpus analyses, intensive field work, and other means of empirical

verification. Crossing the boundaries of particular languages or language families

has lent additional support to the findings emerging from our research.

If one had to name a key notion of cognitive grammar, one would

certainly point to the dependence of linguistic structure on conceptualization

as well as the conceptualized perspective. Within this framework,

meanings are defined relative to conceptual domains, particular linguistic choices

are often found to hinge upon the vantage point from which a given

situation is viewed, and category boundaries are seen as fluctuating and

dependent on, among other things, the conceptualized experience or purpose.

This relativism extends to the very structure of the framework. The reader

will soon discover that not all contributors to the volume draw the same

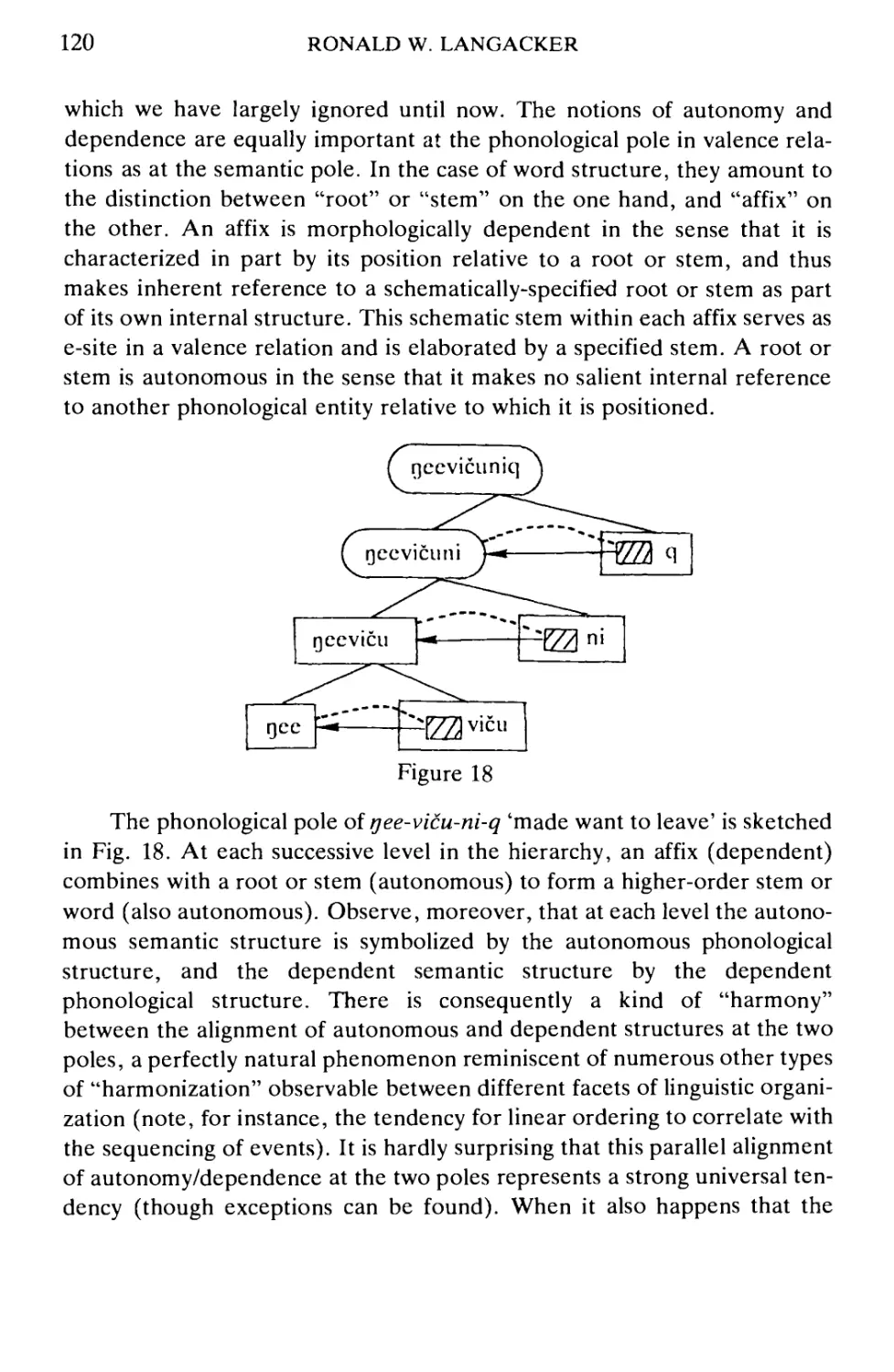

distinctions.Neither do they use identical descriptive tools. Their choice and

nature vary with the purpose as well as perspective adopted.

This inherent flexibility renders the framework exceptionally receptive

to findings in other disciplines. Only some of the current interdisciplinary

crossovers could be signalled here; but they suffice to show the enormous

potential of cognitive grammar in capturing various facets of language. As

language is such a complex phenomenon, it can be adequately described

only when approached from different angles. By relativizing its own

methodology, cognitive linguistics can accommodate these different angles

readily and naturally.

X

PREFACE

To place cognitive grammar against a broader background, we have

explored some earlier linguistic theories. While adding another dimension

to our research, this exploration has unveiled interesting links between

present and past attempts at grasping the relation of language to cognition.

The project has materialized thanks to the help of several people. I am

indebted to Rene Dirven who came up with the idea and suggested to me

the role of editor. The conferences organized by him, first at the University

of Trier and now in Duisburg, have allowed many of us to come together

and discuss topics of common interest; and for this wonderful forum we

remain grateful.

As editor, I wish to thank the authors for their contributions, but also

for their good humor and the spirit of cooperation. Much of the present

volume is the fruit of an intensive exchange of ideas and materials, and also

numerous revisions. In this context, a special word of thanks is due to

Rene Dirven, Dirk Geeraerts, Bruce Hawkins and Pierre Swiggers, all of

whom offered to act as referees on several occasions. To Peter Kelly, I owe

a particular debt of gratitude for sharing with me his native-speaker

intuition.

Finally, I must record my great appreciation for my husband's

encouragement and help at all stages of the project.

Brygida Rudzka-Ostyn

PARTI

TOWARD A COHERENT AND

COMPREHENSIVE LINGUISTIC THEORY

An Overview of Cognitive Grammar

Ronald W. Langacker

University of California, San Diego

Orientation

Cognitive grammar (formerly "space grammar") is a theory of

linguistic structure that I have been developing and articulating since 1976.

Though neither finished nor formalized, it has achieved a substantial

measure of internal coherence and is being applied to an expanding array of

languages and grammatical phenomena (see Langacker 1981, 1982a , 1984,

1985, in press; Casad 1982a; Casad and Langacker 1985; Hawkins 1984;

Lindner 1981, 1982; Smith 1985; Tuggy 1981; Vandeloise 1984, 1985a).

These efforts have been prompted by the feeling tha* established theories

fail to come to grips in any sensible way with the real problems of language

structure, as they are based on interlocking sets of concepts, attitudes, and

assumptions that misconstrue the nature of linguistic phenomena and thus

actually hinder our understanding of them. It is therefore necessary to start

anew and erect a theory on very different conceptual foundations.

Cognitive grammar thus diverges quite radically from the mainstream

of contemporary linguistic theory, particularly as represented in the

generative tradition. The differences are not confined to matters of detail, but

reach to the level of philosophy and organizing assumptions. I will

succinctly sketch these differences as they pertain to the nature of linguistic

investigation, the nature of a linguistic system, the nature of grammatical

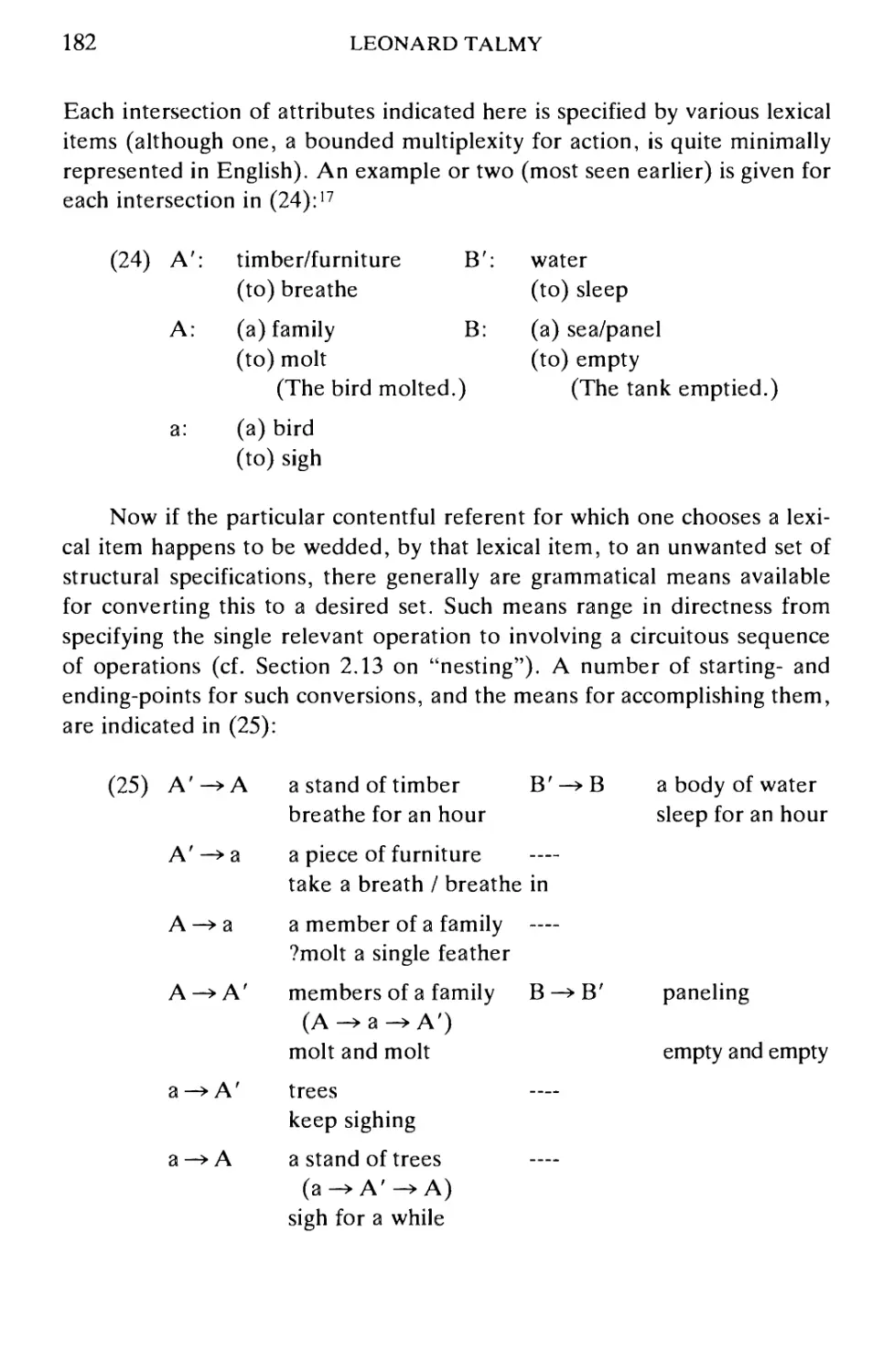

structure, and the nature of meaning. My presentation of the "orthodox"

position is admittedly a caricature; I state it without the necessary

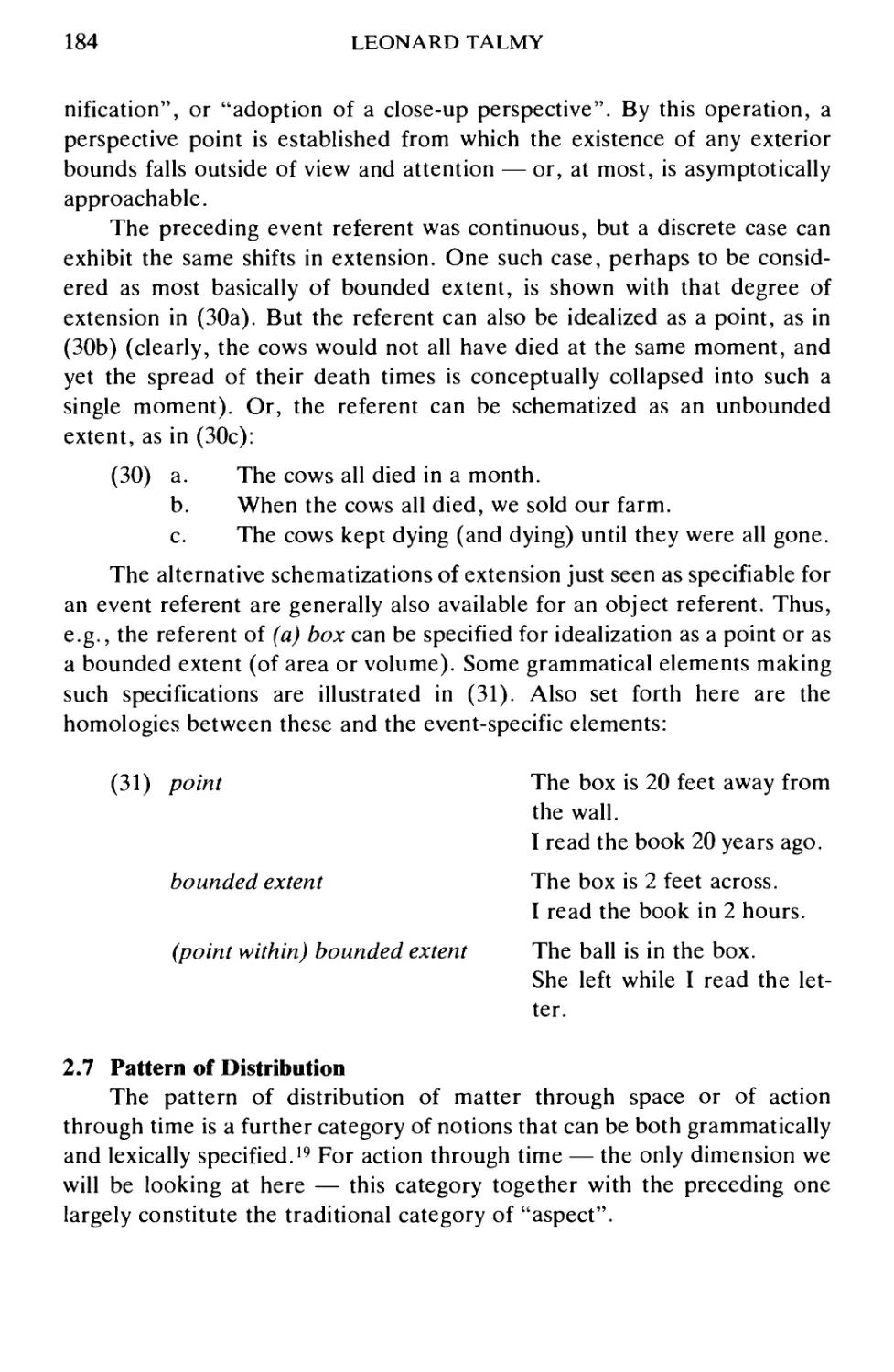

qualifications for sake of brevity, and also to underscore the substantially different

spirit of the two approaches.

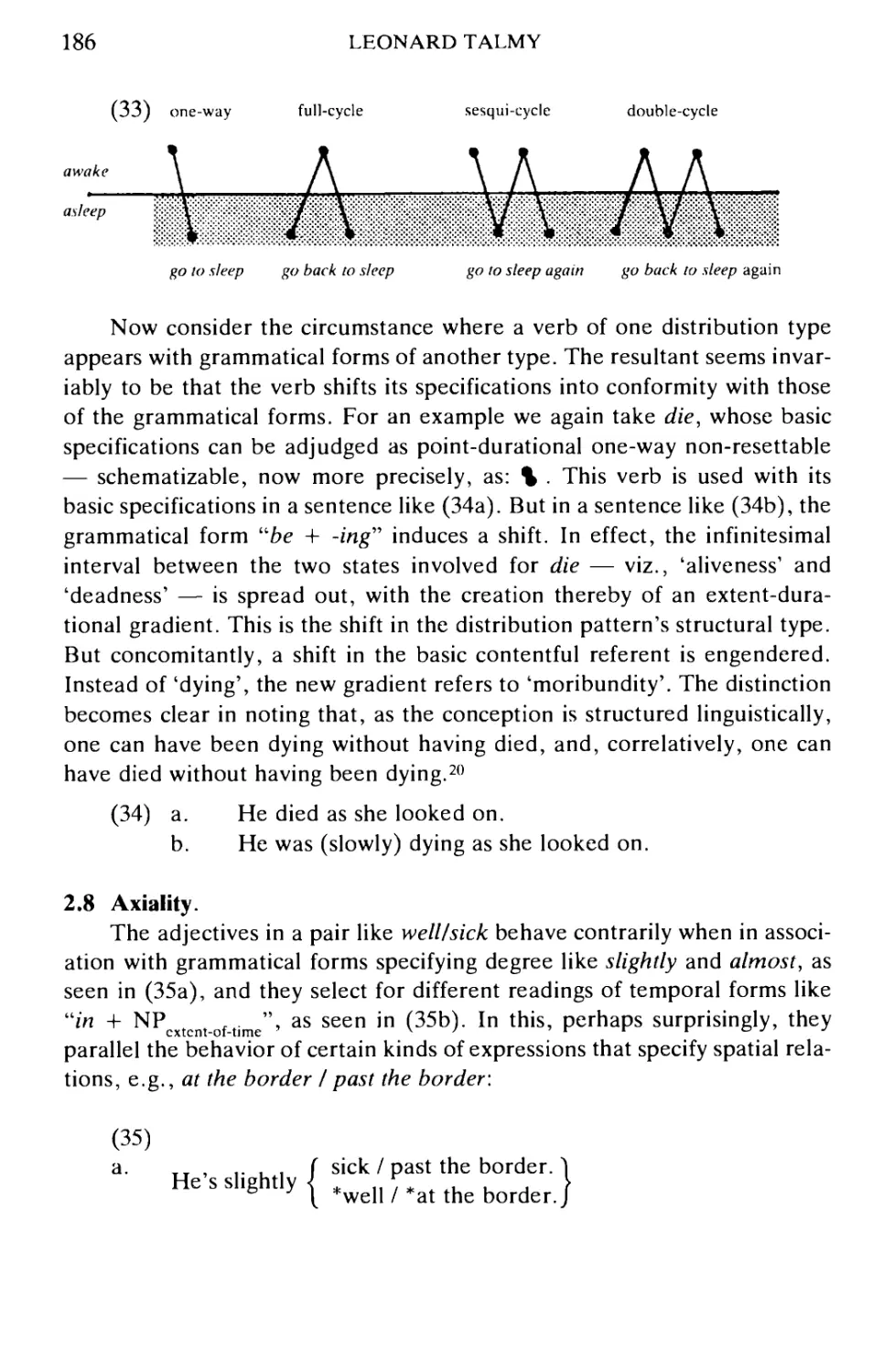

® Ronald W. Langacker

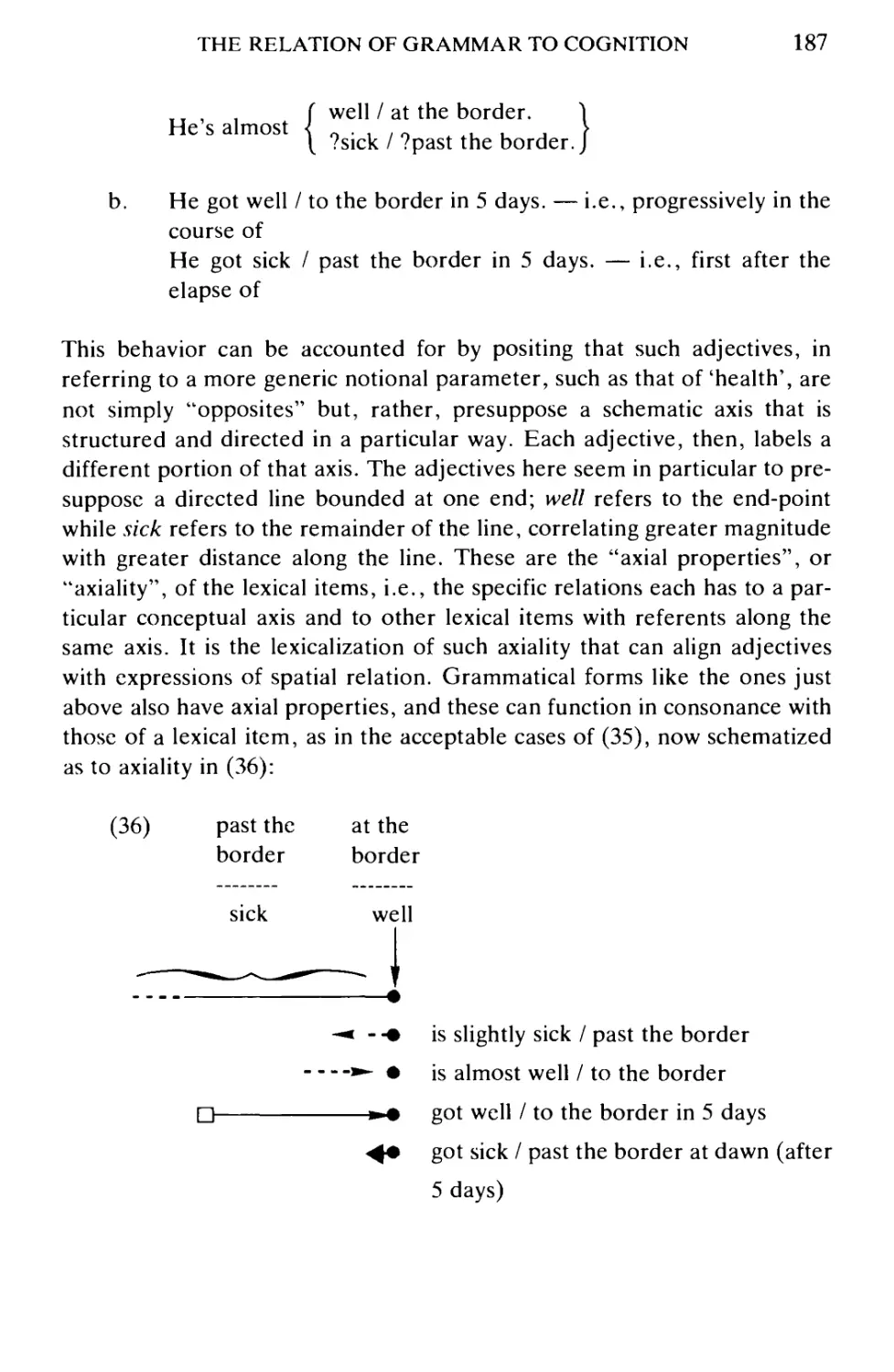

4

RONALD W. LANGACKER

With respect to the nature of linguistic investigation, orthodox theory

holds that language (or at least grammar) is describable as an algorithmic

system. Linguistics is thus a formal science akin to logic and certain

branches of mathematics (e.g. automata theory). Of paramount importance

is the construction of an all-embracing linguistic theory incorporating

explanatory principles; ongoing description is considered most valuable

when formulated in terms of current theory and directed towards the

testing and refinement of its predictions. Discrete categories and absolute

principles are sought, on the grounds that a theory should be maximally

restrictive and make the strongest possible claims. Moreover, economy is a prime

concern in formulating the grammar of a language: redundancy of

statement implies the loss of significant generalizations.

The cognitive grammar "heresy" sees biology as providing a better

metaphor for linguistic research than the formal sciences. While certain

aspects of language may be discrete and "algebraic", in general a language

is more accurately likened to a biological organism; our expectations

concerning the nature of revealing analysis and viable description must be

adjusted accordingly. For instance, absolute predictability is normally an

unrealistic expectation for natural language: much is a matter of degree,

and the role of convention is substantial. Considerations of economy must

cede priority to psychological accuracy; redundancy is plausibly expected in

the cognitive representation of linguistic structure, and does not in principle

conflict with the capturing of significant generalizations. Further, linguistic

theory should emerge organically from a solid descriptive foundation.

Preoccupation with theory may be deleterious if premature, for it stifles the

investigation of non-conforming phenomena and prevents them from being

understood in their own terms.

In the orthodox view, the grammar of a language consists of a number

of distinct "components". The grammar is conceived as a "generative"

device which provides a fully explicit enumeration of "all and only the

grammatical sentences" of the language. The linguistic system is

self-contained, and hence describable without essential reference to broader

cognitive concerns. Language may represent a separate "module" of

psychological structure.

Cognitive grammar views the linguistic system in a very different

fashion. It assumes that language evokes other cognitive systems and must be

described as an integral facet of overall psychological organization. The

grammar of a language is non-generative and non-constructive, for the

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

5

expressions of a language do not constitute a well-defined, algorithmically-

computable set. The grammar of a language simply provides its speakers

with an inventory of symbolic resources — using these resources to

construct and evaluate appropriate expressions is something that speakers do

(not grammars) by virtue of their general categorizing and problem-solving

abilities. Only semantic, phonological, and symbolic units are posited, and

the division of symbolic units into separate components is considered

arbitrary.

Orthodox theory treats grammar (and syntax in particular) as an

independent level or dimension of linguistic structure. Grammar (or at least

syntax) is considered distinct from both lexicon and semantics, and describe

able as an autonomous system. The independence of grammatical structure

is argued by claiming that grammatical categories are based on formal

rather than semantic properties. Speakers are capable of ignoring meaning

and making discrete well-formedness judgments based on grammatical

structure alone.

By contrast, cognitive grammar claims that grammar is intrinsically

symbolic, having no independent existence apart from semantic and

phonological structure. Grammar is describable by means of symbolic units

alone, with lexicon, morphology, and syntax forming a continuum of

symbolic structures. Basic grammatical categories (e.g. noun and verb) are

semantically definable, and the unpredictable membership of other classes

(those defined by occurrence in particular morphological or syntactic

constructions) does not itself establish the independence of grammatical

structure. Well-formedness judgments are often matters of degree, and reflect

the subtle interplay of semantic and contextual factors.

Finally, it is commonplace to reject a "conceptual" or "ideational"

theory of meaning as being untenable for the scientific investigation of

language. It is assumed instead that the meanings of linguistic expressions are

describable in terms of truth conditions, and that some type of formal logic

is appropriate for natural language. It is held that a principled distinction

can be made between semantics and pragmatics (or between linguistic and

extralinguistic knowledge), that semantic structure is fully compositional,

and that such phenomena as metaphor and semantic extension lie outside

the scope of linguistic description.

In the cognitive grammar heresy, meaning is equated with

conceptualization (interpreted quite broadly), to be explicated in terms of cognitive

processing. Formal logic is held to be inadequate for the description of

6

RONALD W. LANGACKER

semantic structure, which is subjective in nature and incorporates

conventional "imagery" — defined as alternate ways of construing or mentally

portraying a conceived situation. Linguistic semantics is properly considered

encyclopedic in scope: the distinction between semantics and pragmatics is

arbitrary. Semantic structure is only partially compositional, and

phenomena like metaphor and semantic extension are central to the proper

analysis of lexicon and grammar.

Meaning and Semantic Structure

An "objectivist" view of meaning has long been predominant in

semantic theory. Rigorous analysis, it is maintained, cannot be based on

anything so mysterious and inaccessible as "concepts" or "ideas"; instead,

the meaning of an expression is equated with the set of conditions under

which it is true, and some type of formal logic is deemed appropriate for the

description of natural language semantics. Without denying its

accomplishments, I believe the objectivist program to be inherently limited and

misguided in fundamental respects: standard objections to the ideational view

are spurious, and a formal semantics based on truth conditions is attainable

only by arbitrarily excluding from its domain numerous aspects of meaning

that are of critical linguistic significance (cf. Chafe 1970: 73-75; Langacker

in press: Part II; Hudson 1984).

Cognitive grammar explicitly equates meaning with

"conceptualization" (or "mental experience"), this term being interpreted quite broadly.

It is meant to include not just fixed concepts, but also novel conceptions

and experiences, even as they occur. It includes not just abstract,

"intellectual" conceptions, but also such phenomena as sensory, emotive, and

kinesthetic sensations. It further embraces a person's awareness of the

physical, social, and linguistic context of speech events. There is nothing

inherently mysterious about conceptualization: it is simply cognitive

processing (neurological activity). Entertaining a particular conceptualization, or

having a certain mental experience, resides in the occurrence of some

complex "cognitive event" (reducing ultimately to the coordinated firing of

neurons). An established concept is simply a "cognitive routine", i.e. a

cognitive event (or event type) sufficiently well "entrenched" to be elicited as

an integral whole.

Cognitive grammar embraces a "subjectivist" view of meaning. The

semantic value of an expression does not reside solely in the inherent prop-

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

7

erties of the entity or situation it describes, but crucially involves as well the

way we choose to think about this entity or situation and mentally portray

it. Expressions that are true under the same conditions, or which have the

same reference or extension, often contrast in meaning nonetheless by

virtue of representing alternate ways of mentally construing the same

objective circumstances. I would argue, for example, that each pair of sentences

in (1) embodies a semantic contrast that a viable linguistic analysis cannot

ignore:

(1) (a) This is a triangle.

(a') This is a three-sided polygon.

(b) The glass is half-empty.

(b>) The glass is half-full.

(c) This roof slopes upward,

(c') This roof slopes downward.

(d) Louise resembles Rebecca,

(d') Rebecca resembles Louise.

(e) Russia invaded Afghanistan.

(e') Afghanistan was invaded by Russia.

(f) I mailed a package to Bill.

(f) I mailed Bill a package.

I use the term "imagery" to indicate our ability to mentally construe a

conceived situation in alternate ways (hence the term does not refer

specifically or exclusively to sensory or visual imagery (cf. Kosslyn 1980; Block

1981)). A pivotal claim of cognitive grammar is that linguistic expressions

and grammatical constructions embody conventional imagery, which

constitutes an essential aspect of their semantic value. In choosing a particular

expression or construction, a speaker construes the conceived situation in a

certain way, i.e. he selects one particular image (from a range of

alternatives) to structure its conceptual content for expressive purposes. Despite

the objective equivalence of the sentence pairs in (1), the members of each

are semantically distinct because they impose contrasting images on the

conceived situation.

At this point, I will confine my discussion of imagery to a single

example, namely the semantic contrasts distinguishing the universal quantifiers

of English. It is intuitively obvious that the sentences in (2) have subtly

different meanings despite their truth-functional equivalence:

8

RONALD W. LANGACKER

(2) (a) All cats are playful.

(b) Any cat is playful.

(c) Every cat is playful.

(d) Each cat is playful.

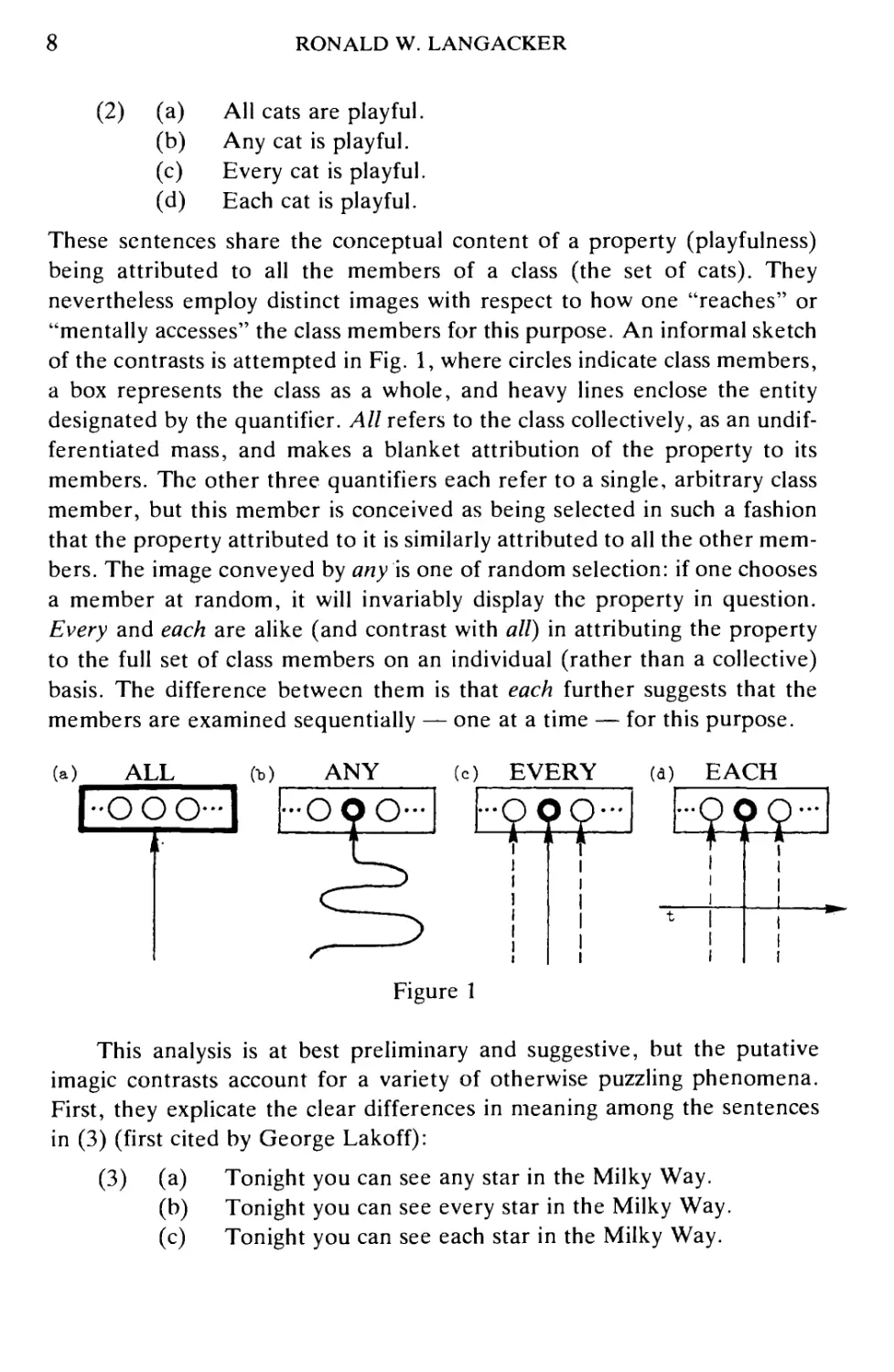

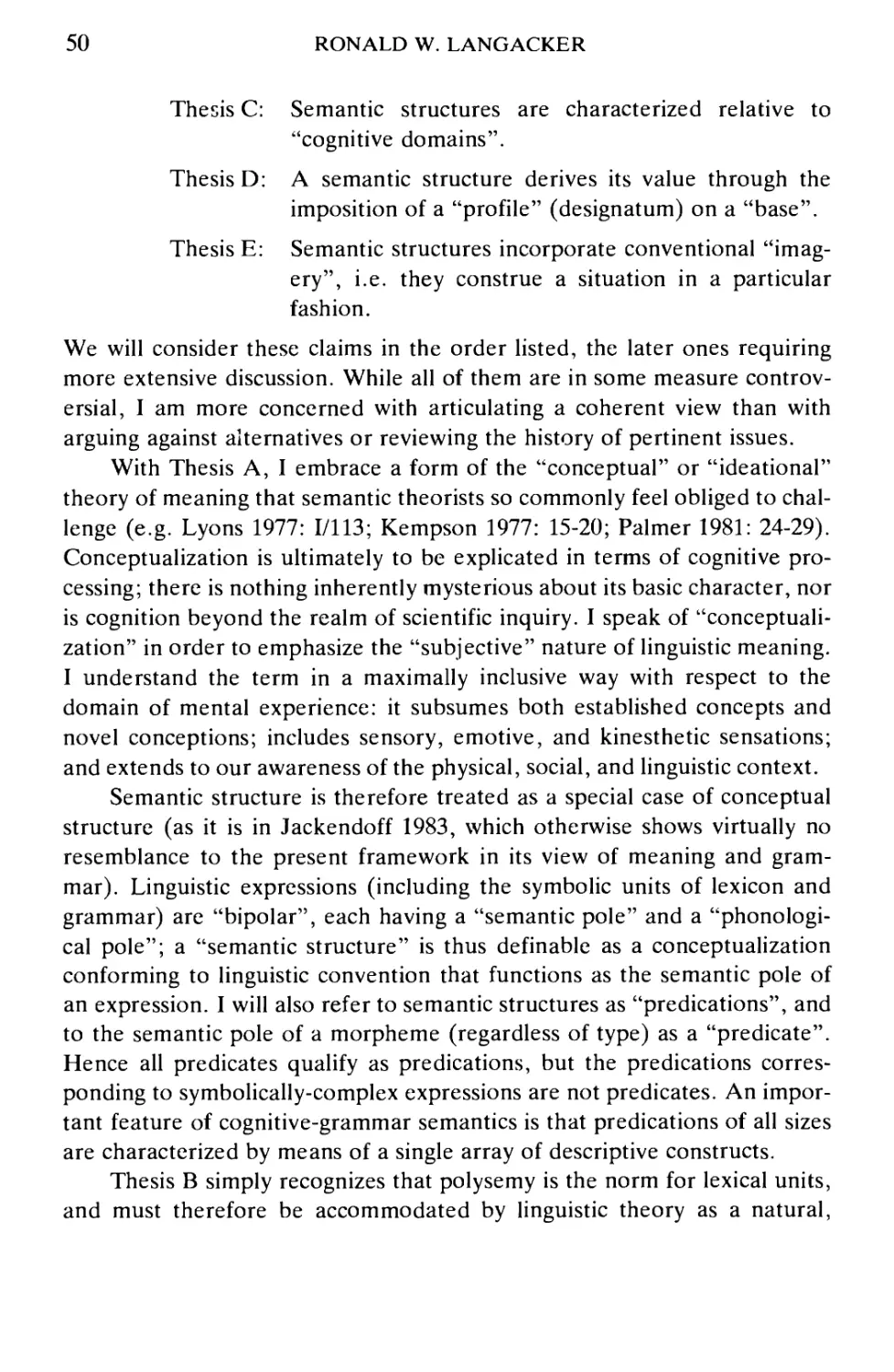

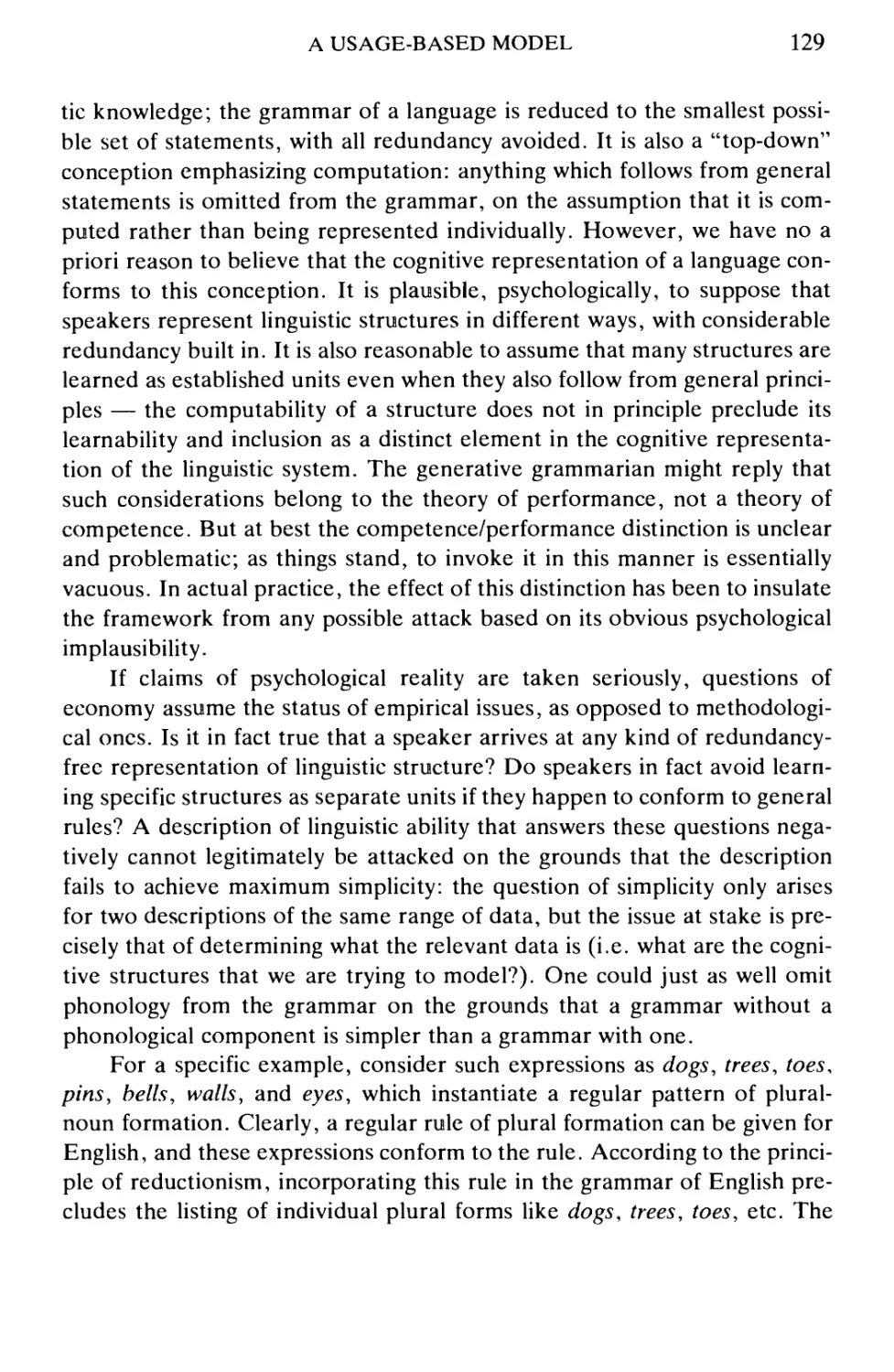

These sentences share the conceptual content of a property (playfulness)

being attributed to all the members of a class (the set of cats). They

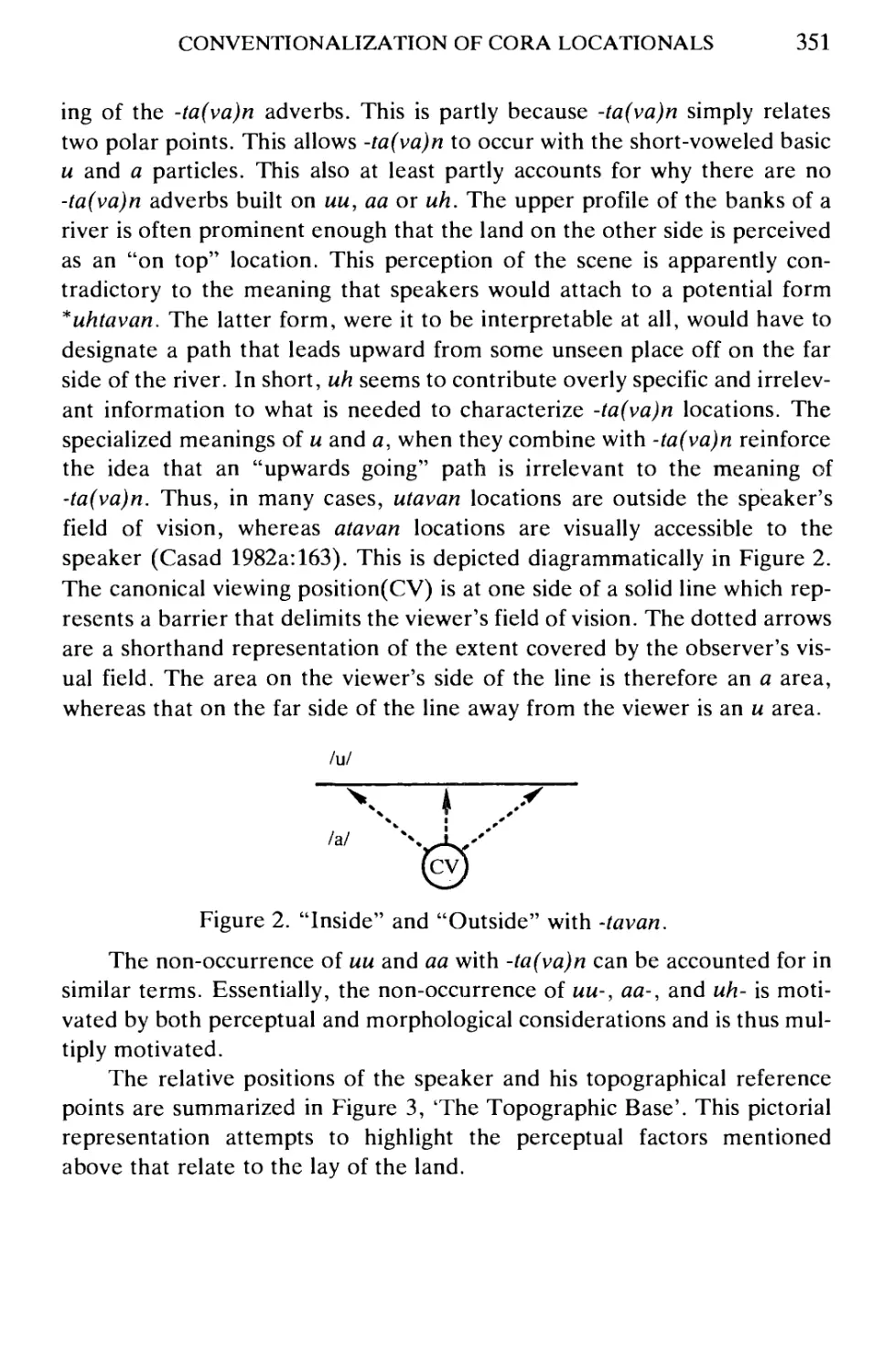

nevertheless employ distinct images with respect to how one "reaches" or

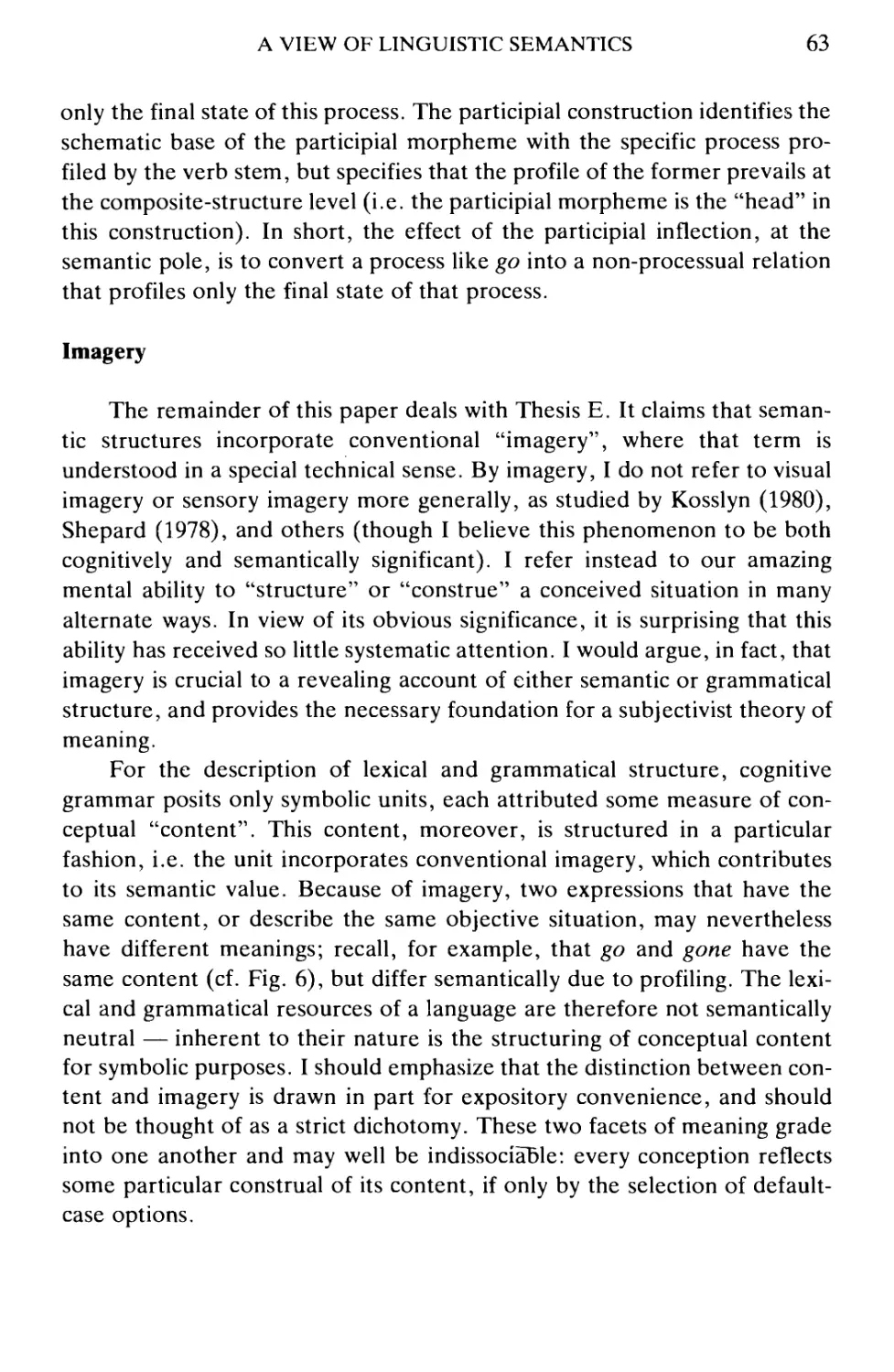

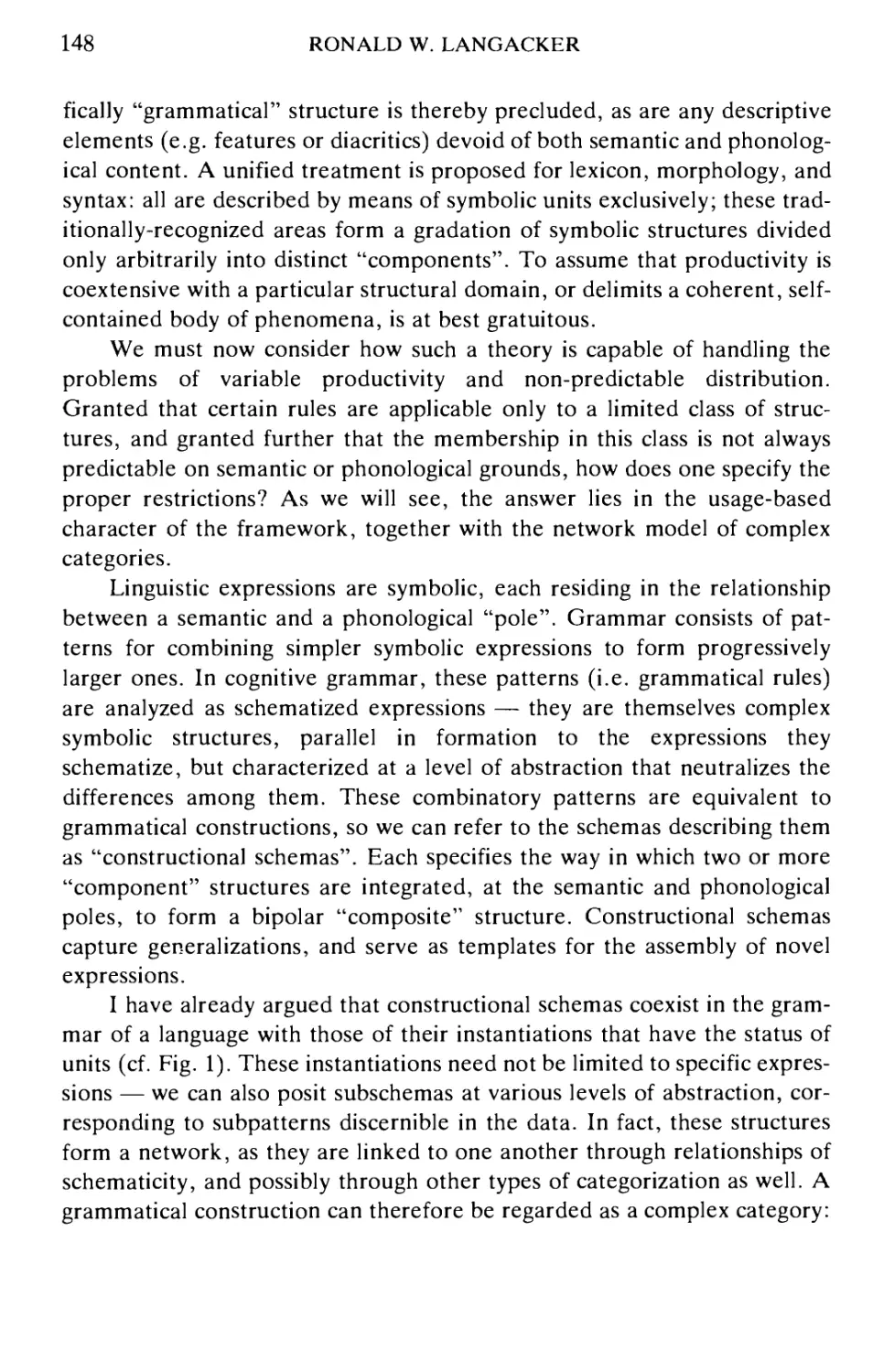

"mentally accesses" the class members for this purpose. An informal sketch

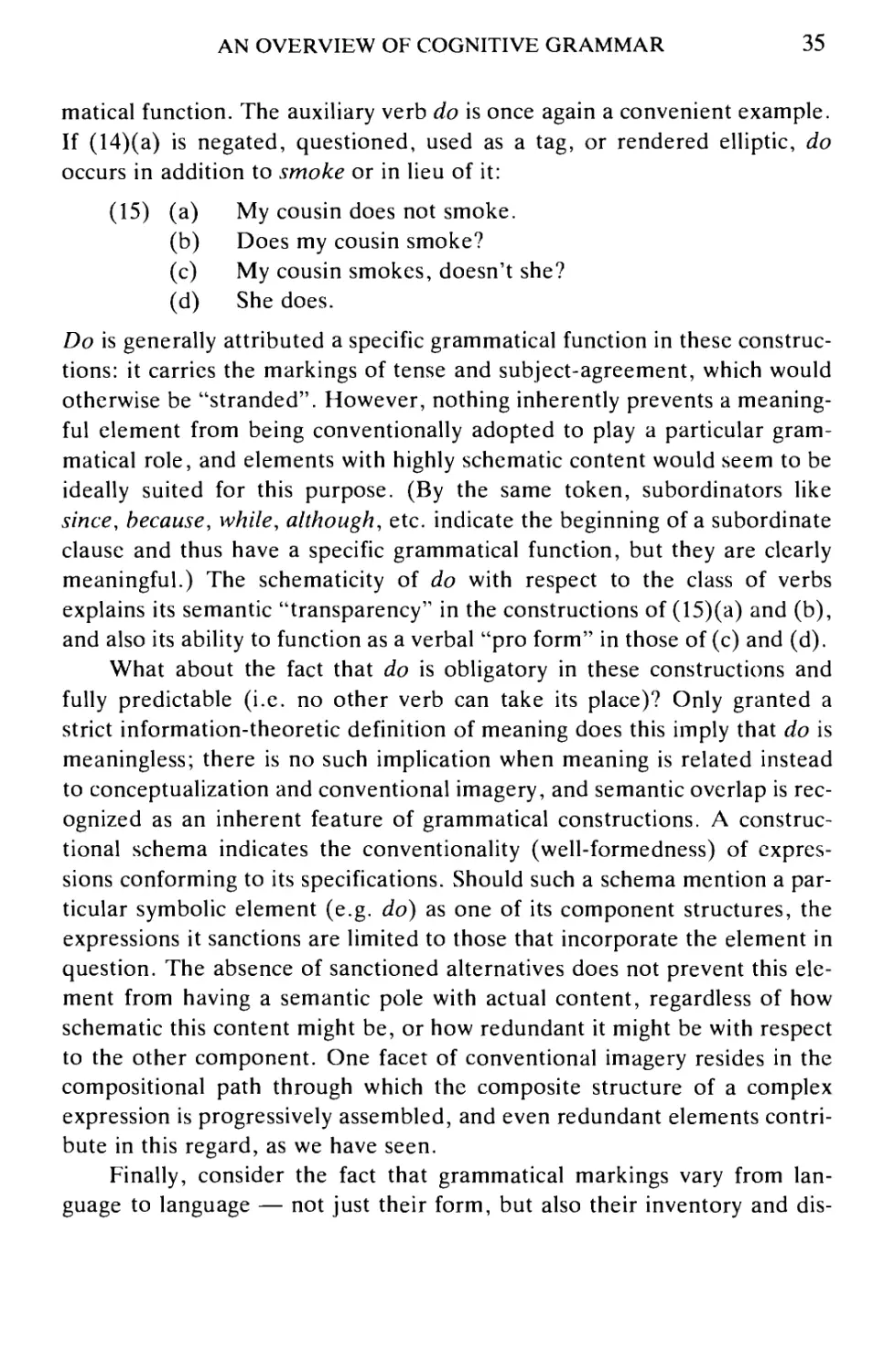

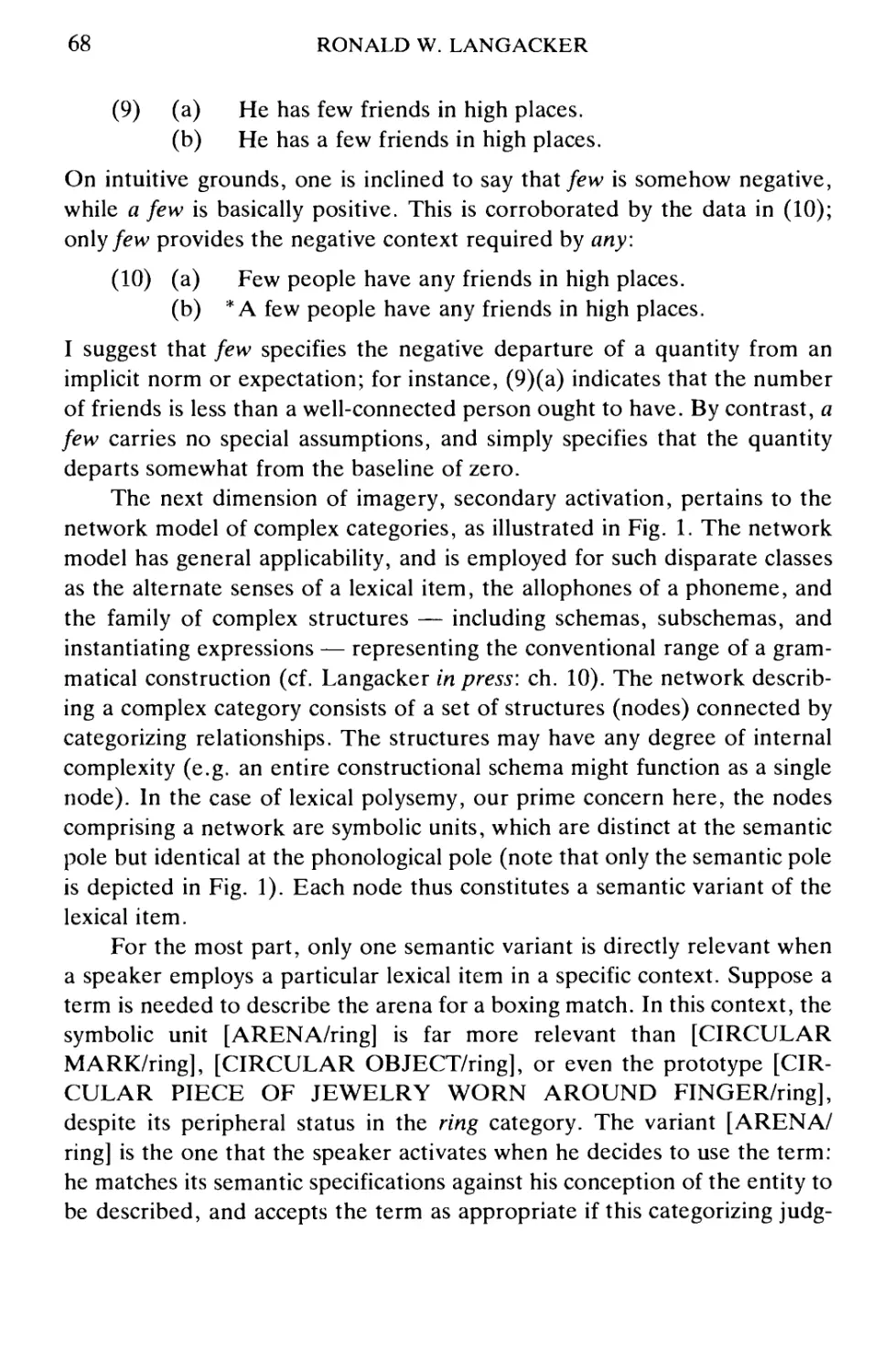

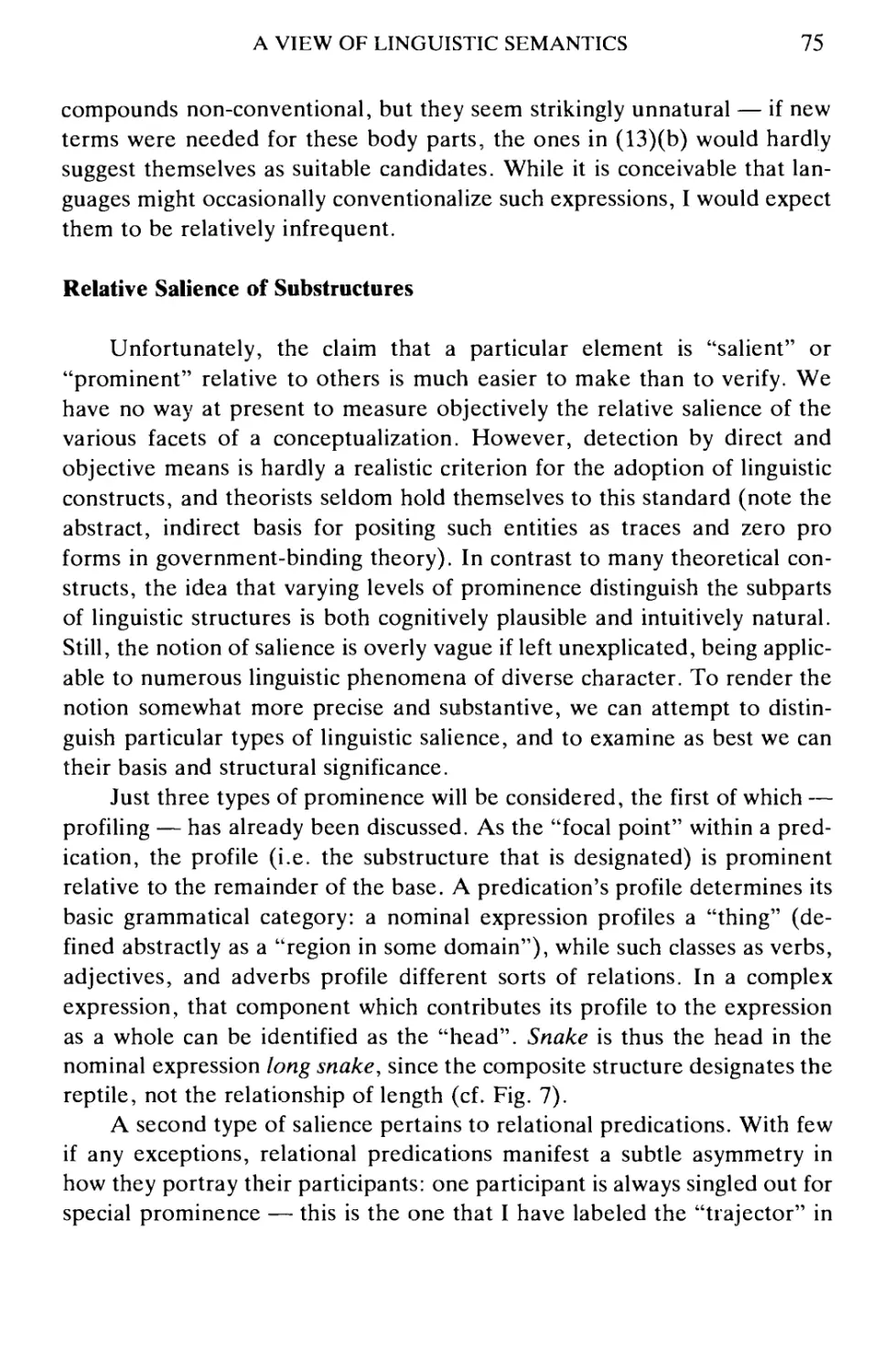

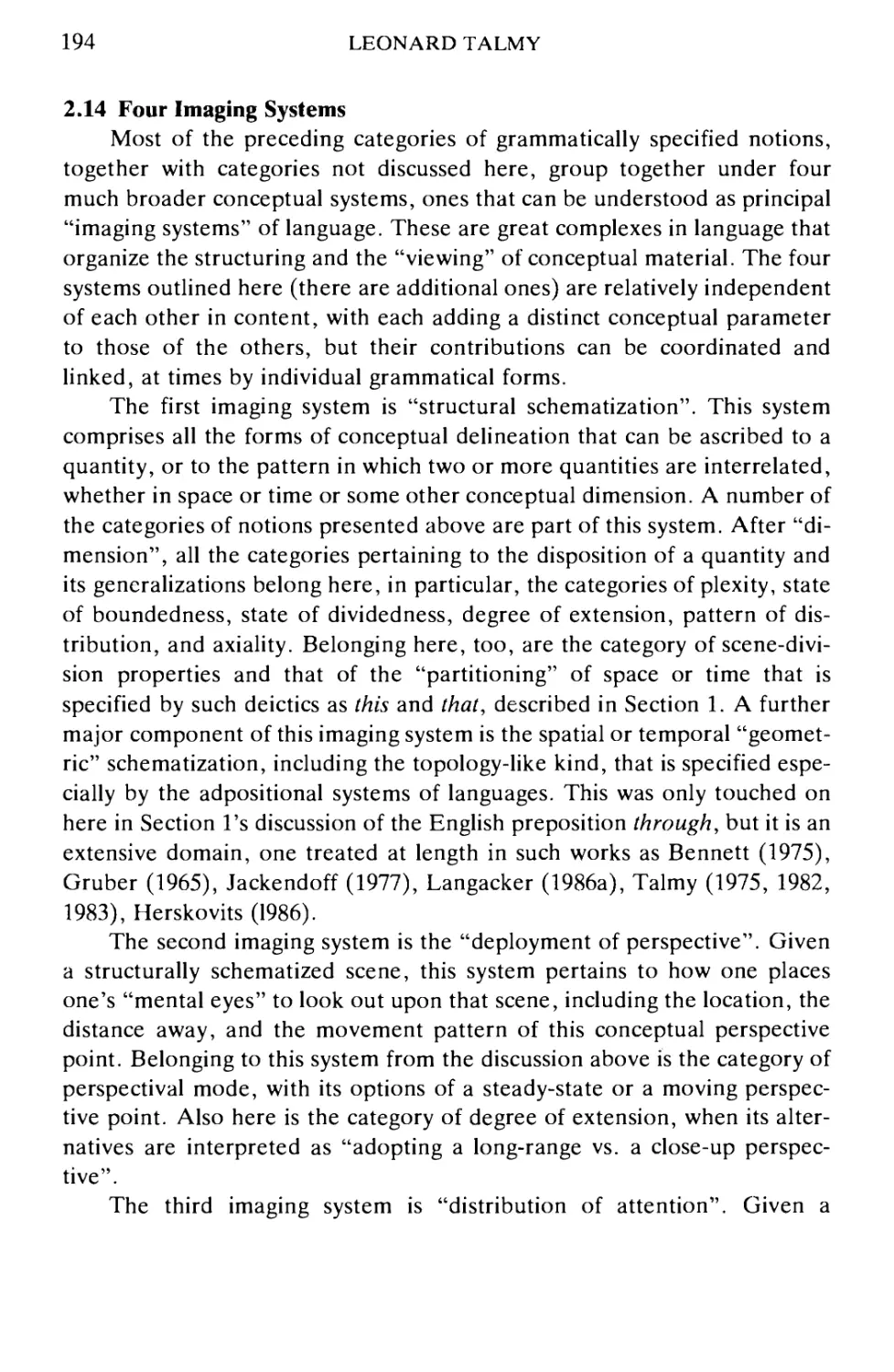

of the contrasts is attempted in Fig. 1, where circles indicate class members,

a box represents the class as a whole, and heavy lines enclose the entity

designated by the quantifier. All refers to the class collectively, as an

undifferentiated mass, and makes a blanket attribution of the property to its

members. The other three quantifiers each refer to a single, arbitrary class

member, but this member is conceived as being selected in such a fashion

that the property attributed to it is similarly attributed to all the other

members. The image conveyed by any is one of random selection: if one chooses

a member at random, it will invariably display the property in question.

Every and each are alike (and contrast with all) in attributing the property

to the full set of class members on an individual (rather than a collective)

basis. The difference between them is that each further suggests that the

members are examined sequentially — one at a time — for this purpose.

(a)

ALL

ANY

l-ooo-l

c) EVERY

|-o t

1 j

??'"

1 ♦

1

1

1

1

1

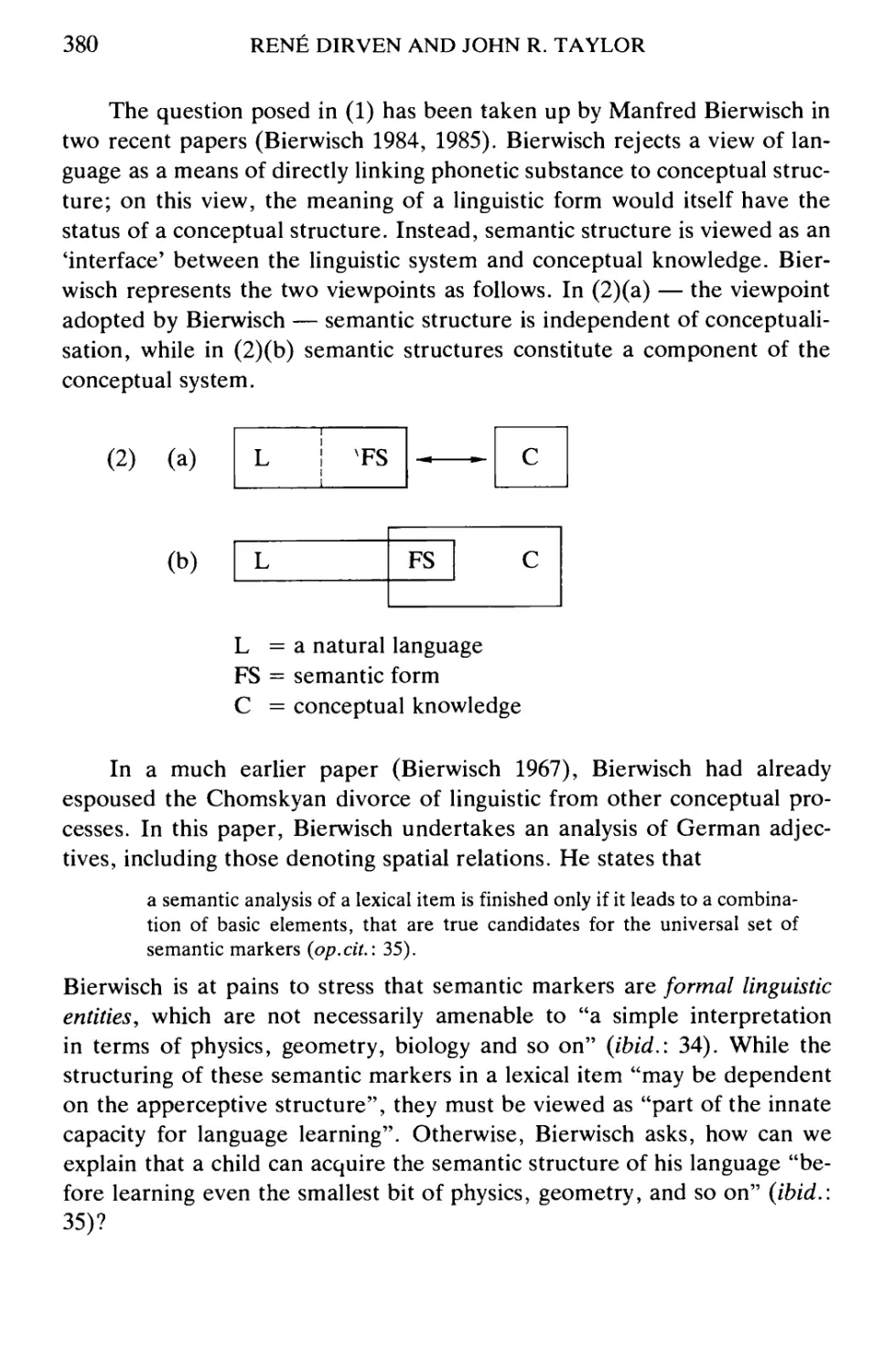

1

(d) EACH

|-o <

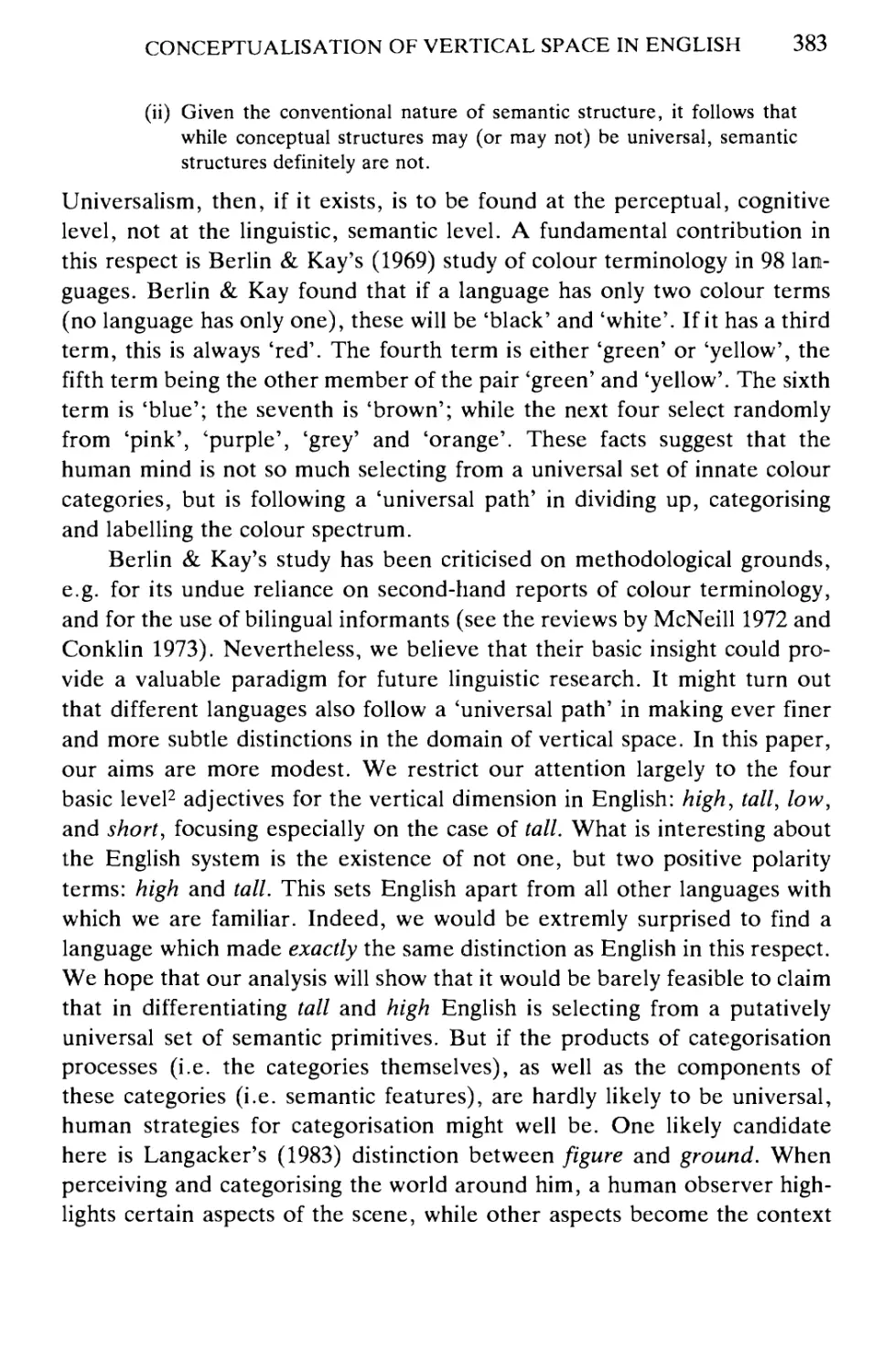

f J

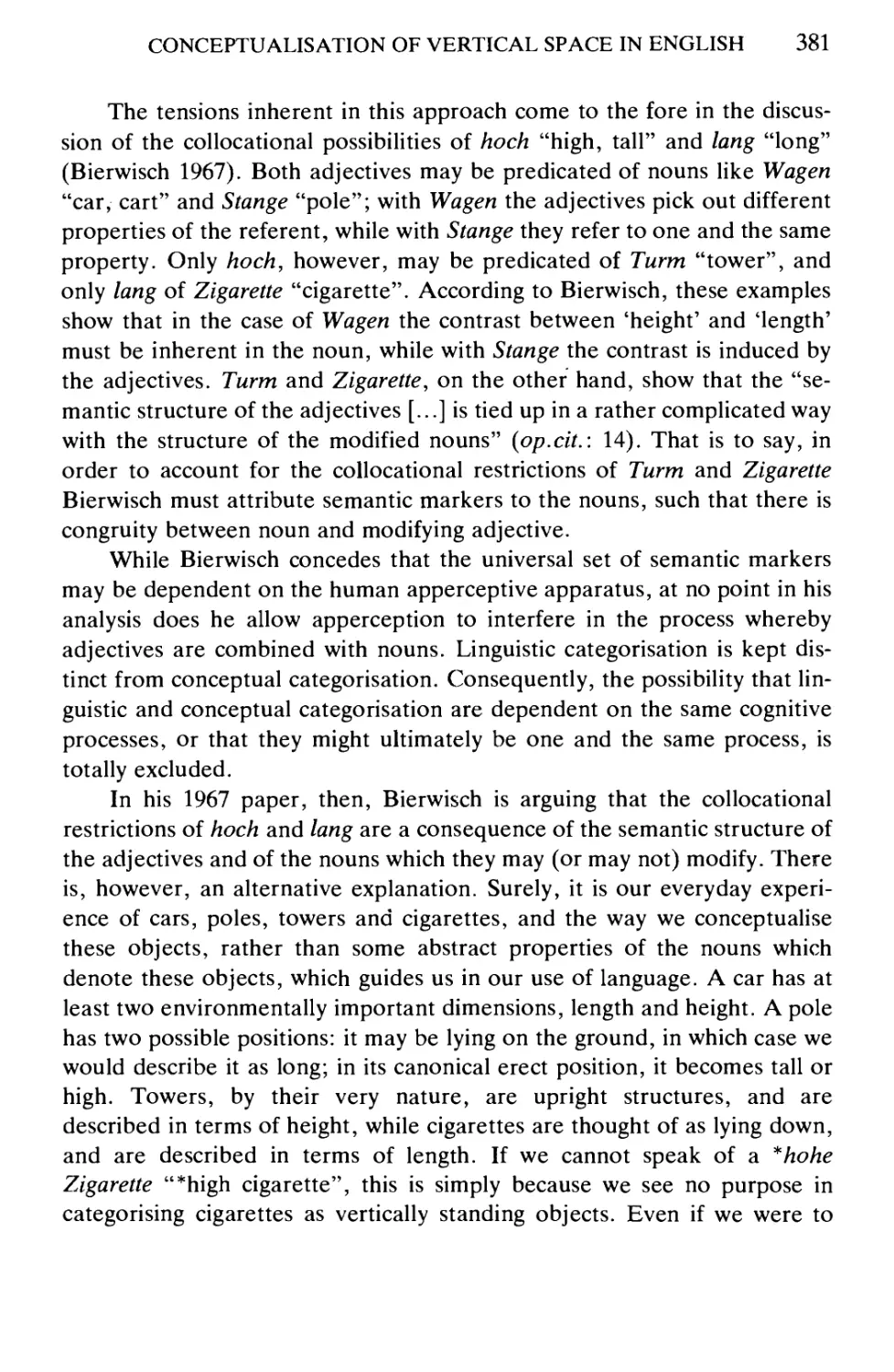

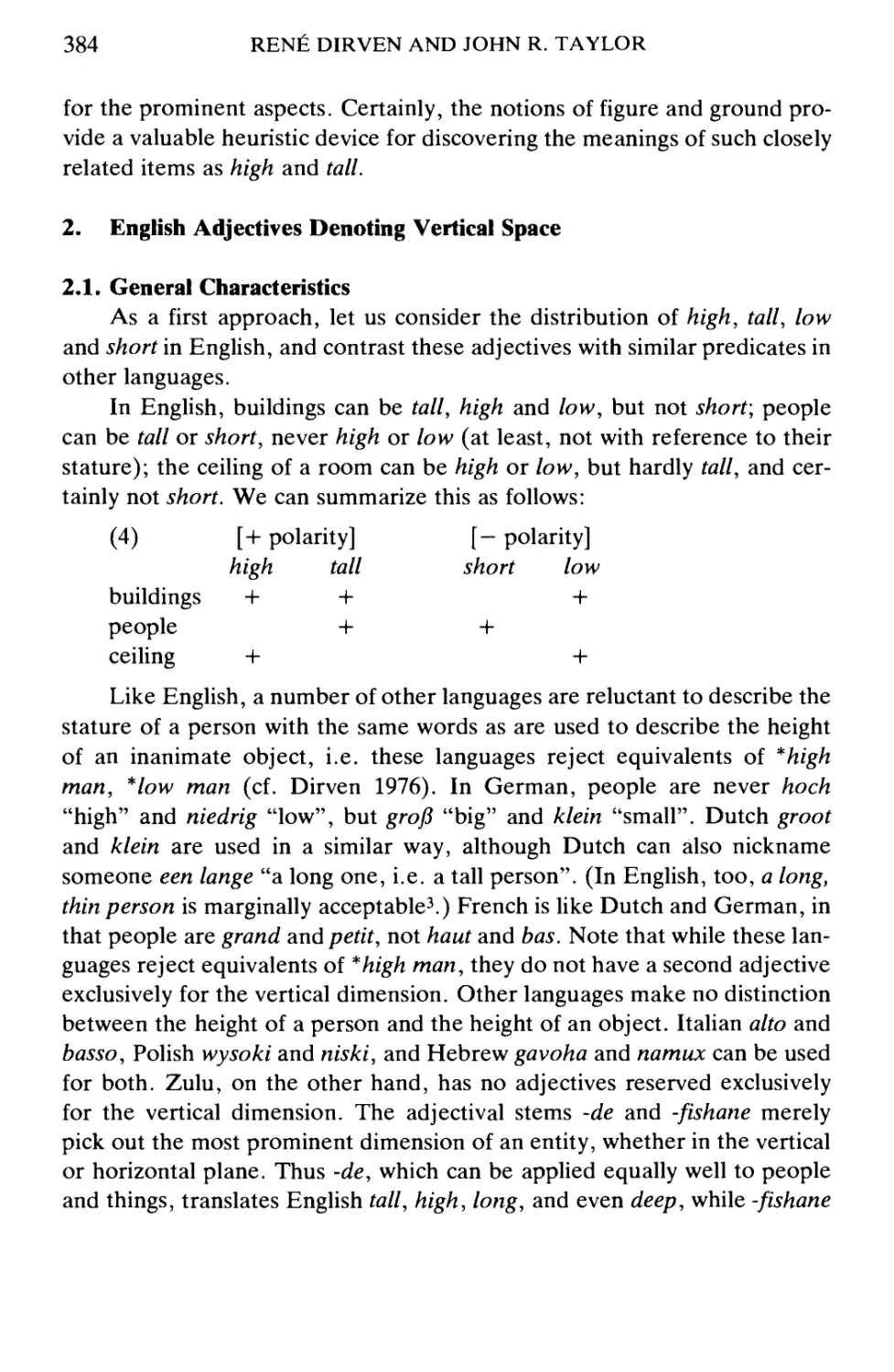

1

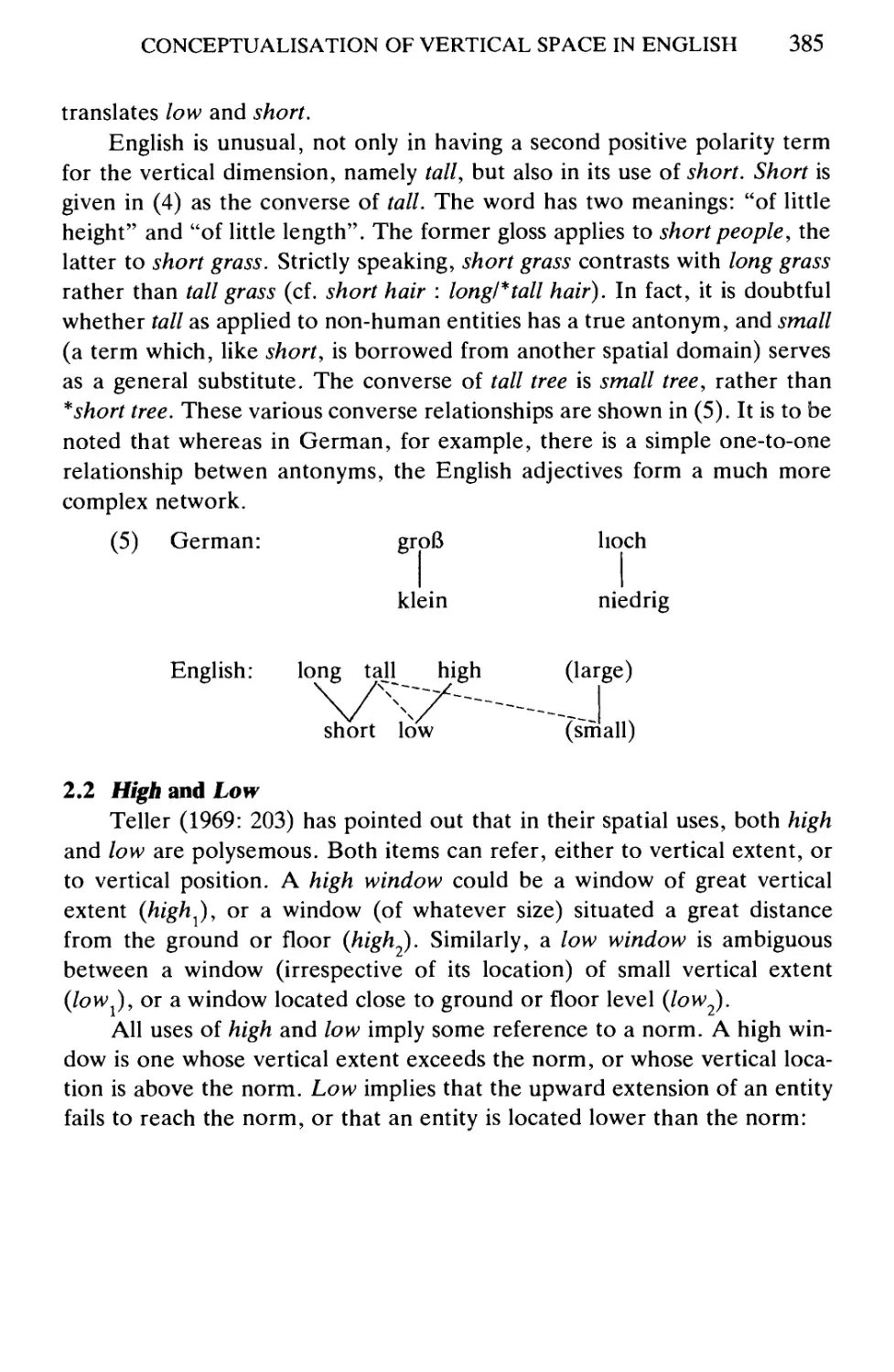

1

1

* 1

1

1

??•■■

1 A

i

I

1

1

1

1

Figure 1

This analysis is at best preliminary and suggestive, but the putative

imagic contrasts account for a variety of otherwise puzzling phenomena.

First, they explicate the clear differences in meaning among the sentences

in (3) (first cited by George Lakoff):

(3) (a) Tonight you can see any star in the Milky Way.

(b) Tonight you can see every star in the Milky Way.

(c) Tonight you can see each star in the Milky Way.

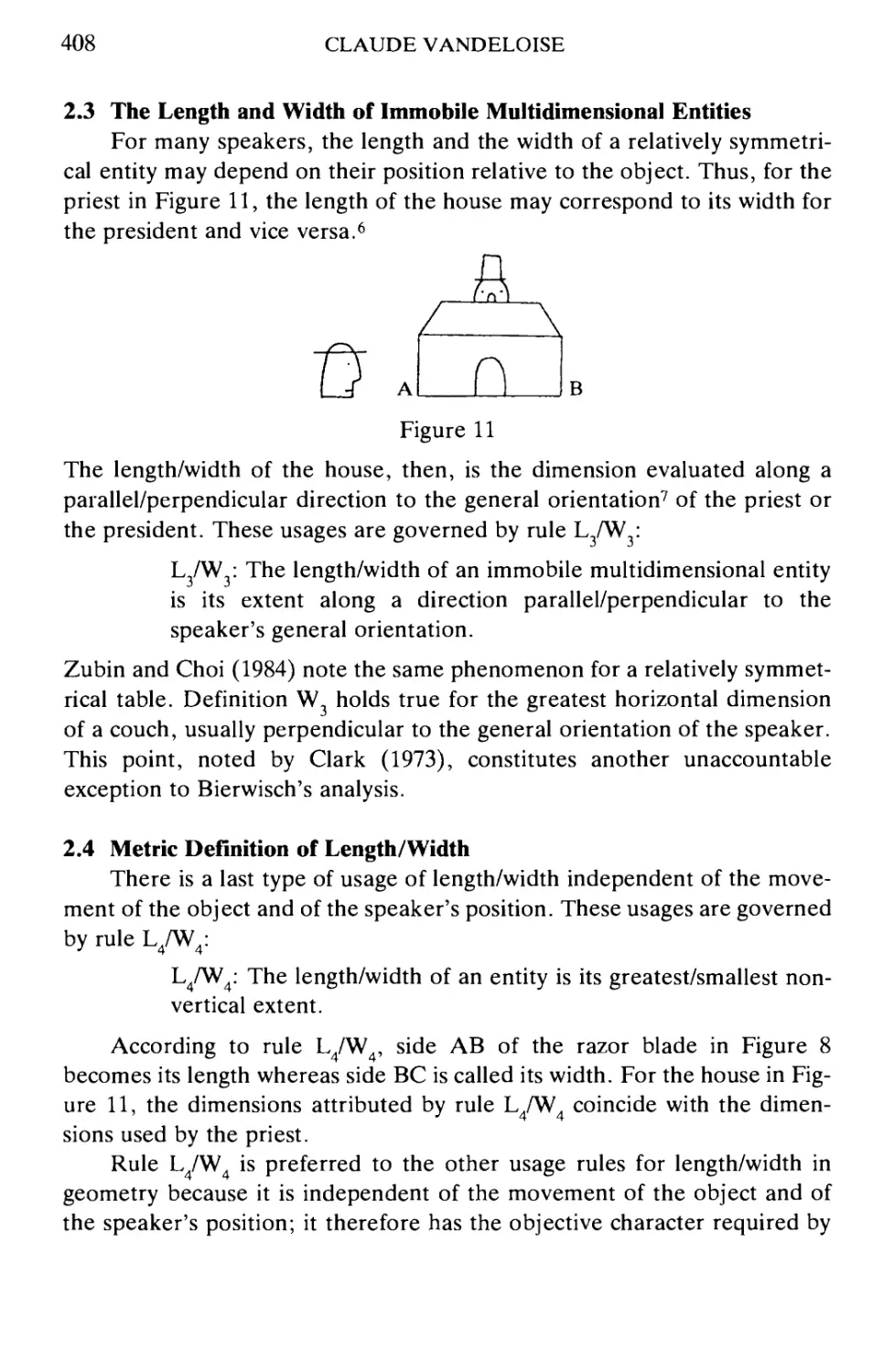

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

9

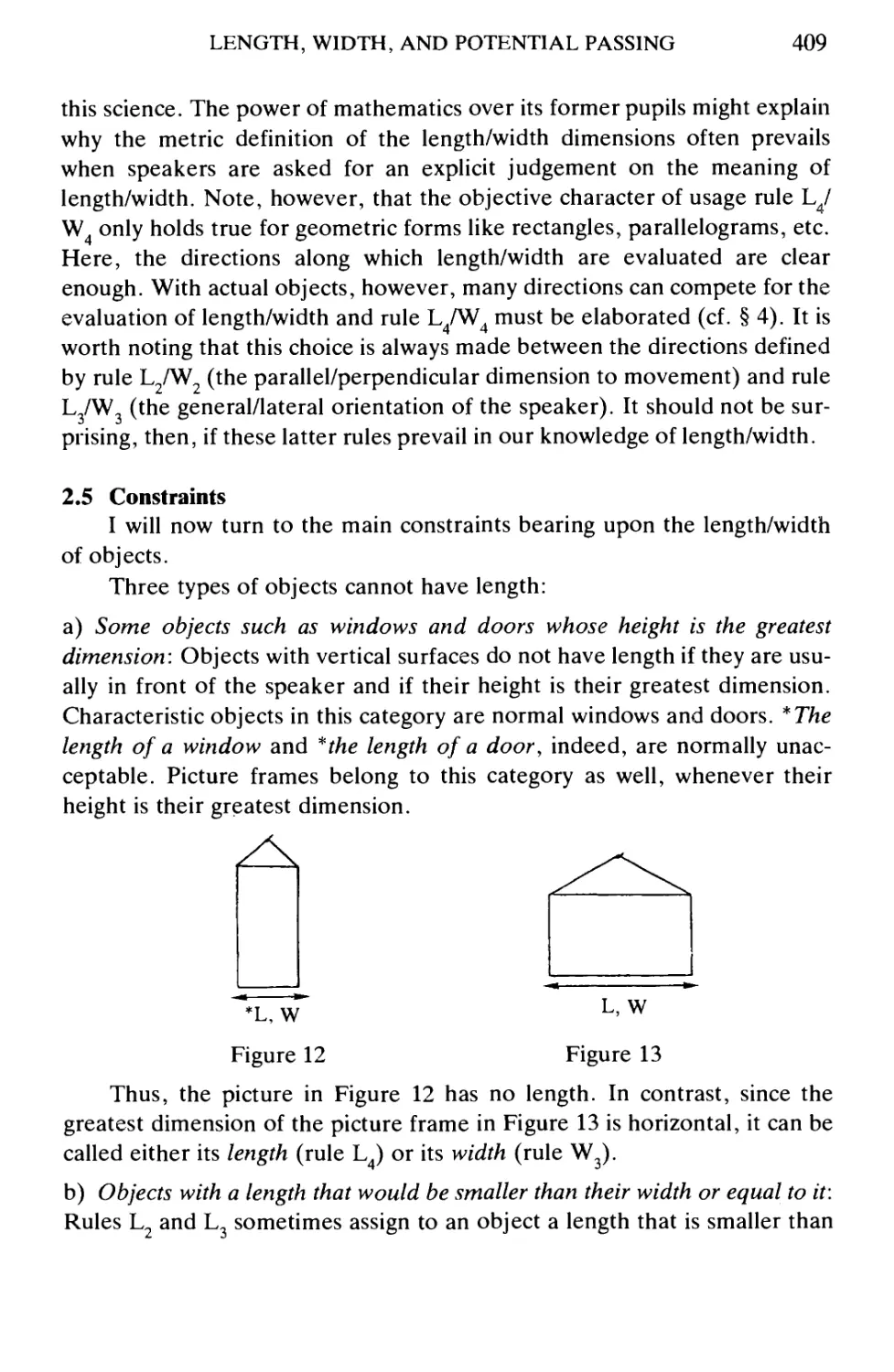

Speakers readily agree that (3)(a) describes the ability to see a single star:

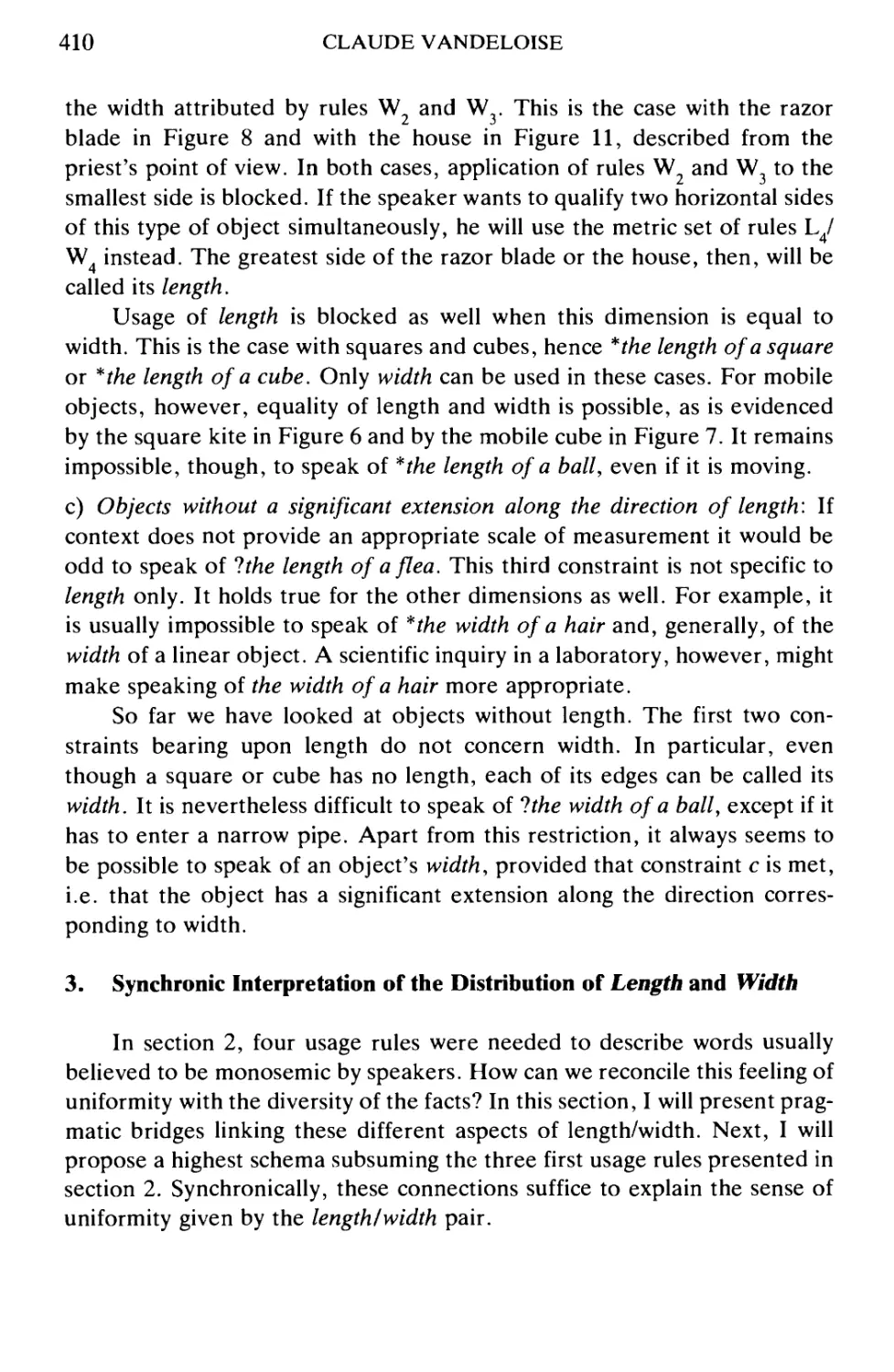

if a particular star is in the Milky Way, tonight you can see it, whichever

one you choose to look at. In (3)(b), the stars of the Milky Way are viewed

simultaneously, but nevertheless stand out as individuals. This

individuation is even stronger in (3)(c), which evokes the image of the viewer shifting

his gaze across the sky, looking first at one star, then at another, and so on.

The analysis further explains the grammatical behavior of the

quantifiers, for instance the ability of any, every, and each (but not all) to occur

with a singular count noun or the pro form one:

(4) (a) any star

(b) every star

(c) each star

(d) * all star

(5) (a) any one of those stars

(b) every one of those stars

(c) each one of those stars

(d) * all one of those stars

Moreover, because they specify individual attribution of the property to

multiple class members, every and each construe the class with a greater

degree of individuation than either all (which views the class collectively) or

any (which specifically invokes only a single, randomly selected member);

the former two quantifiers specifically highlight the status of the class as an

aggregate of distinct individuals. It is natural, then, that mass nouns

(including plurals) should occur with only all and any, since the hallmark of a

mass is internal homogeneity:

(6) (a) all water

(b) any water

(c) * every water

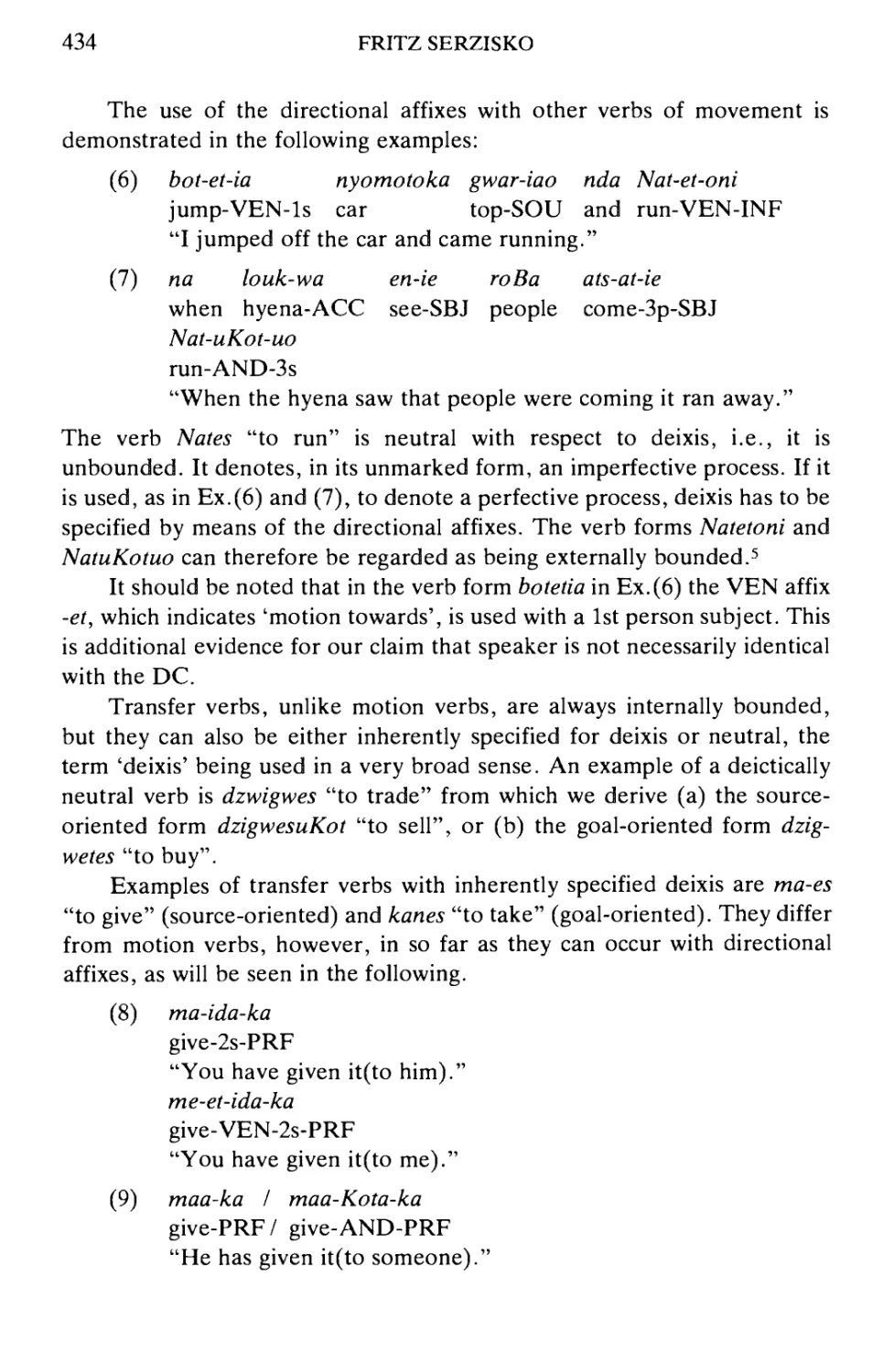

(d) *each water

(7) (a) all cats

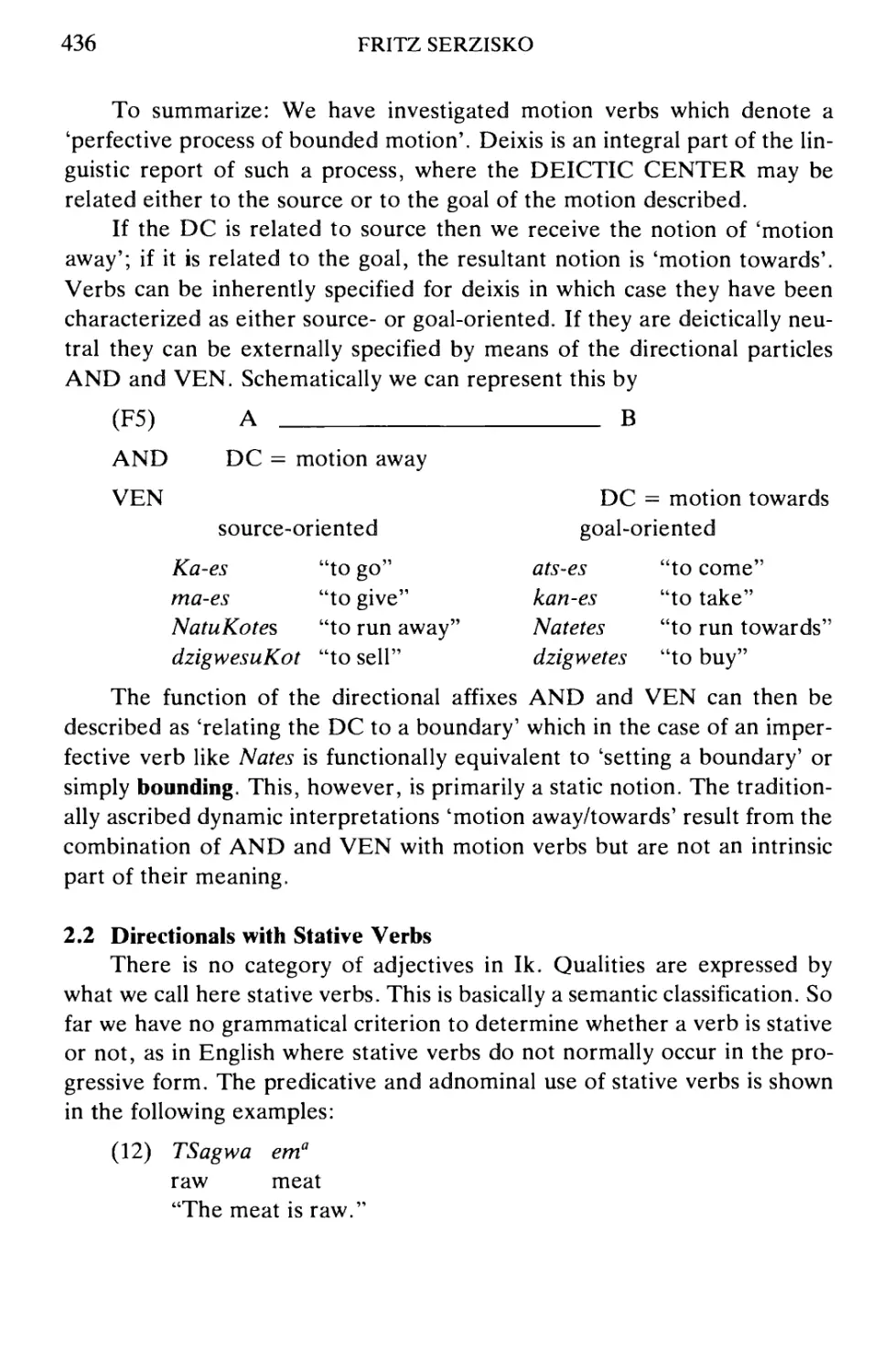

(b) any cats

(c) * every cats

(d) * each cats

The analysis also explains the judgments in (8) and (9).

(8) (a) He examined each one in turn,

(b) He examined every one in turn.

10

RONALD W. LANGACKER

(c) ?He examined all in turn.

(d) *He examined any one in turn.

(9) (a) All cats have something in common.

(b) ?Every cat has something in common.

(c) *?Each cat has something in common.

(d) * Any cat has something in common.

In turn specifies tliat the examination described in (8) affects class members

individually and sequentially. This is fully compatible with each and every

(and reinforces something suggested by the former). Sentence (8)(c) is a bit

peculiar, since the collective construal imposed by all is at cross-purposes

with the individuating force of the adverbial, i.e. there is a certain amount

of tension between the images evoked by different components of the

expression. In (8)(d) this conflict in imagery is even more pronounced,

since any specifically picks out only a single member of the class for

attribution of the property, while in turn implies the participation of multiple

individuals. The semantic effect of have something in common runs counter to

that of in turn, for the notion of commonality requires the simultaneous

conception of class members. The well-formedness judgments in (9) are

thus essentially the inverse of those in (8). The collective character of all

renders (9)(a) unproblematic, while the individuation suggested by every

and each accounts for the relative infelicity of (9)(b) and (c), greater (as

expected) in the case of each. However the sentence with any is once again

the least acceptable, and for the same reason as before: only a single class

member is specifically selected (at random) for attribution of the property,

but have something in common (like in turn) implies access to multiple

members.

The notion of sequential examination may further account for the fact

that each is non-generic, i.e. a sentence like (2)(d) is only used with respect

to some restricted subset of class members identifiable from the context

(not the set of cats as a whole). The reason, perhaps, is that sequential

examination is not easily conceived as providing mental access to all

members of an open-ended, indefinitely expandable class.

This is one example of how the lexical and grammatical resources of a

language embody conventional imagery, which is an inherent and essential

aspect of their semantic value. Two expressions may be functionally

equivalent and serve as approximate paraphrases or translations of one another,

and yet be semantically distinct by virtue of the contrasting images they

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

11

incorporate. The imagery is conventional because the symbolic elements

available to speakers are language-specific and differ unpredictably —

languages simply say things in different ways, even when comparable thoughts

are expressed, as exemplified by the sentences in (10).

(10) (a) I'm cold.

(b) Pai froid.

(c) Mir ist kalt.

In this respect the cognitive grammar view of linguistic semantics is

Whorfian or relativistic. However it is not Whorfian in the sense that this imagery

is taken as imposing powerful or even significant constraints on how or

what we are able to think. I take its influence to be fairly superficial, a

matter of how we package our thoughts for expressive purposes. We shift from

image to image with great facility, even within the confines of a single

sentence, and freely create new ones when those suggested by linguistic

convention do not satisfy our needs.

The Nature of a Grammar

The grammar of a language is characterized as a "structured inventory

of conventional linguistic units". By "unit", I mean a thoroughly mastered

structure (i.e. a cognitive routine). A unit may be highly complex

internally, yet it is simple in the sense of constituting a prepackaged assembly

that speakers can employ in essentially automatic fashion, without

attending to the details of its composition. Examples of units include a lexical

item, an established concept, or the ability to articulate a particular sound

or sound sequence. The units comprising a grammar represent a speaker's

grasp of linguistic convention. I do not limit the term "conventional" to

structures that are arbitrary, unmotivated, or unpredictable: linguistic

structures form a gradation with respect to their degree of motivation, and

no coherence or special status attaches to the subclass of structures that are

fully motivated or to those that are fully arbitrary; speakers operate with

the entire spectrum of structures as an integrated system. Finally, this

inventory of conventional units is "structured" in the sense that some units

function as components (subroutines) of others.

Only three basic types of units are posited: semantic, phonological,

and symbolic. Symbolic units are "bipolar", consisting in the symbolic

relationship between a semantic unit (its "semantic pole") and a phonolog-

12

RONALD W. LANGACKER

ical unit (its "phonological pole"). I claim that lexicon, morphology, and

syntax form a continuum of symbolic structures divided only arbitrarily into

separate components of the grammar. Symbolic units are by no means a

homogeneous class — they vary greatly along certain parameters (e.g.

specificity, complexity, entrenchment, productivity, regularity) — but the

types grade into one another, and do not fall naturally into discrete, non-

overlapping blocks. Grammar (i.e. morphology and syntax) is

accommodated solely by means of symbolic units. The intrinsically symbolic

character of grammatical structure represents a fundamental claim whose import

and viability will be examined in the remainder of this paper.

Treating grammar as symbolic in nature (and not a separate level or

autonomous facet of linguistic structure) enables us to adopt the highly

restrictive "content requirement", which holds that no units are allowed in

the grammar of a language apart from (i) semantic, phonological, and

symbolic units that occur overtly; (ii) "schemas" for the structures in (i); and

(iii) "categorizing relationships" involving the structures in (i) and (ii). For

example, the phonological sequence [tip] occurs overtly, so it is permitted

by (i). The syllable canon [CVC] is "schematic" for [tip] and numerous

other phonological units (i.e. it is fully compatible with their specifications

but characterized with a lesser degree of specificity), so (ii) allows its

inclusion in the grammar. Permitted by (iii) is the categorizing relationship

between the phonological schema [CVC] and a specific sequence like [tip]

that "instantiates" or "elaborates" this schema. I will indicate this

relationship in the following way: [[CVC] —> [tip]], where a solid arrow stands for

the judgment that one structure is schematic for another, and square

brackets enclose a structure with the status of a unit. Hence the categorizing

relationship [[CVC] —> [tip]] is a complex unit containing the simpler units

[CVC] and [tip] as substructures. The schema [CVC] defines a phonological

category, and [[CVC] —> [tip]] characterizes [tip] as an instance of this

category.

The effect of the content requirement is to rule out many sorts of

arbitrary descriptive devices routinely employed in other frameworks. For

example, it rules out the use of "dummies" having neither semantic nor

phonological content, invoked solely to drive the machinery of formal

syntax. Also proscribed is any appeal to arbitrary diacritics or contentless

features (more about this later). It further precludes the derivation of an overt

structure from a hypothetical underlying structure of radically different

character (e.g. the derivation of a passive from an underlying active). There

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

13

is a real sense in which the content requirement is far more constraining

than the conditions, principles, and restrictions which continue to

proliferate (and often evaporate) in the theoretical literature. If valid, it will help

immeasurably to ensure the naturalness of linguistic descriptions.

In describing the grammar of a language as an "inventory'' of

conventional units, I refer to my conception of a grammar as being non-generative

and non-constructive. Specifically rejected is the notion that a grammar can

be regarded as an algorithmic device serving to generate (or give as output)

"all and only the grammatical sentences of a language", at least if the

description of a sentence is taken as including a full semantic

representation. The reason for this rejection is that the full set of expressions is

neither well-defined nor algorithmically computable unless one imposes

arbitrary restrictions on the scope of linguistic description and makes gratuitous

(and seemingly erroneous) assumptions about the nature of language.

Treating the grammar as a generative, constructive device requires (i) the

assumption that well-formedness is absolute, not a matter of degree; (ii) the

exclusion of contextual meaning from the scope of semantic description;

(iii) the omission of metaphor and figurative language from the coverage of

a grammar; (iv) the supposition that semantic structure is fully

compositional; and (v) the claim that a motivated distinction can be made between

semantics and pragmatics (or between linguistic and "extra-linguistic"

knowledge). These positions are commonly taken, but not because the facts

of language use cry out for their adoption. Rather, they are adopted

primarily for methodological reasons, there being no other way to make

language appear to be a self-contained, algorithmically-describable system.

I will simply comment that the convenience to the theorist of positing a self-

contained formal system does not constitute a valid argument for its factual

correctness. I opt for a cognitively and linguistically realistic conception of

language over one that achieves formal neatness at the expense of

drastically distorting and impoverishing its subject matter.

Hence the grammar of a language is not conceived as a generative or

algorithmic device, nor does it construct any expressions or give them as

outputs — it is simply an inventory of symbolic resources. It is up to the

language user to exploit these resources, and doing so is a matter of problem-

solving activity involving categorizing judgments. The results of these

operations draw upon the full body of a speaker's knowledge and cognitive

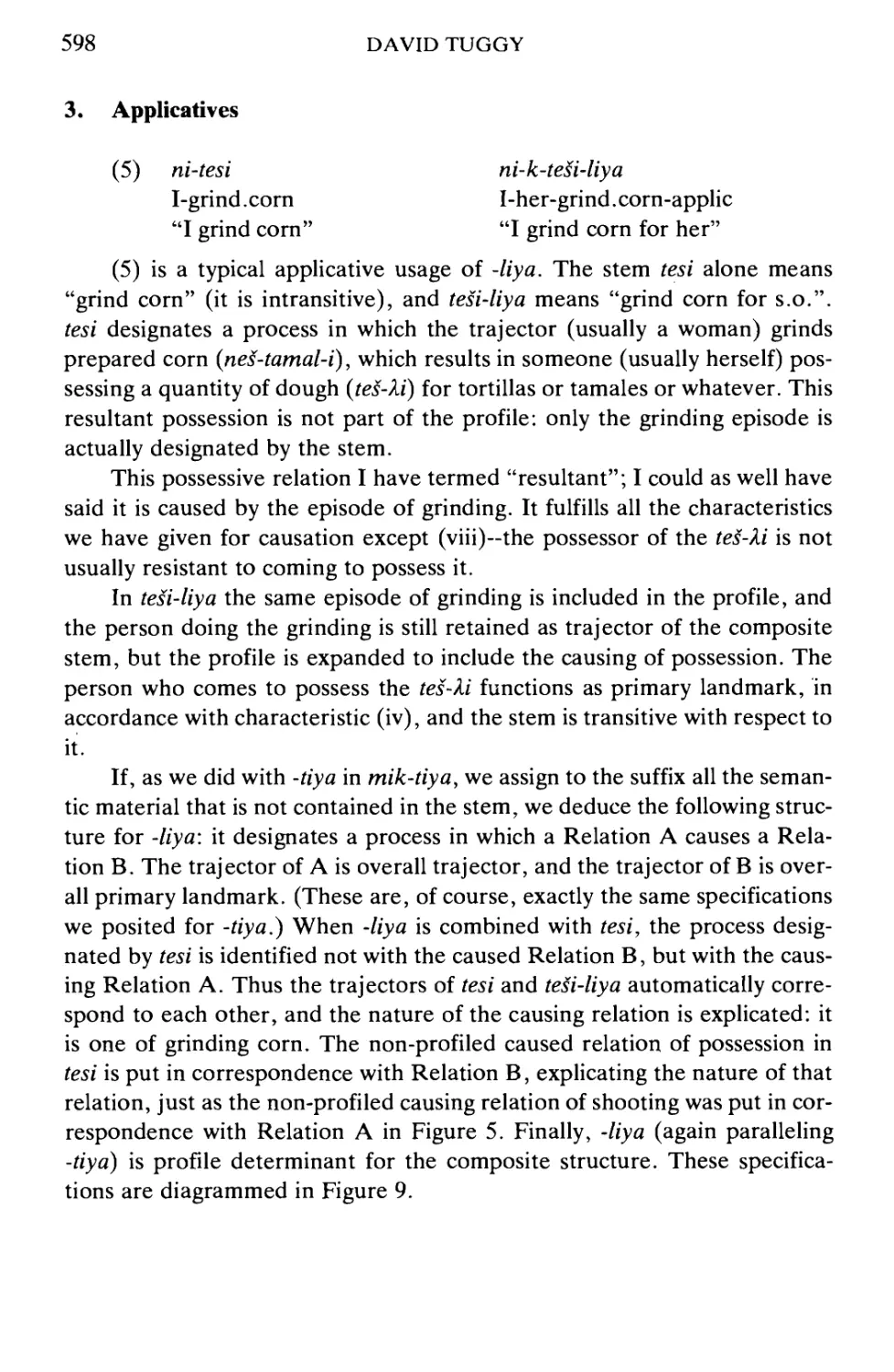

ability, and are thus not algorithmically computable by any limited,

self-contained system.

14

RONALD W. LANGACKER

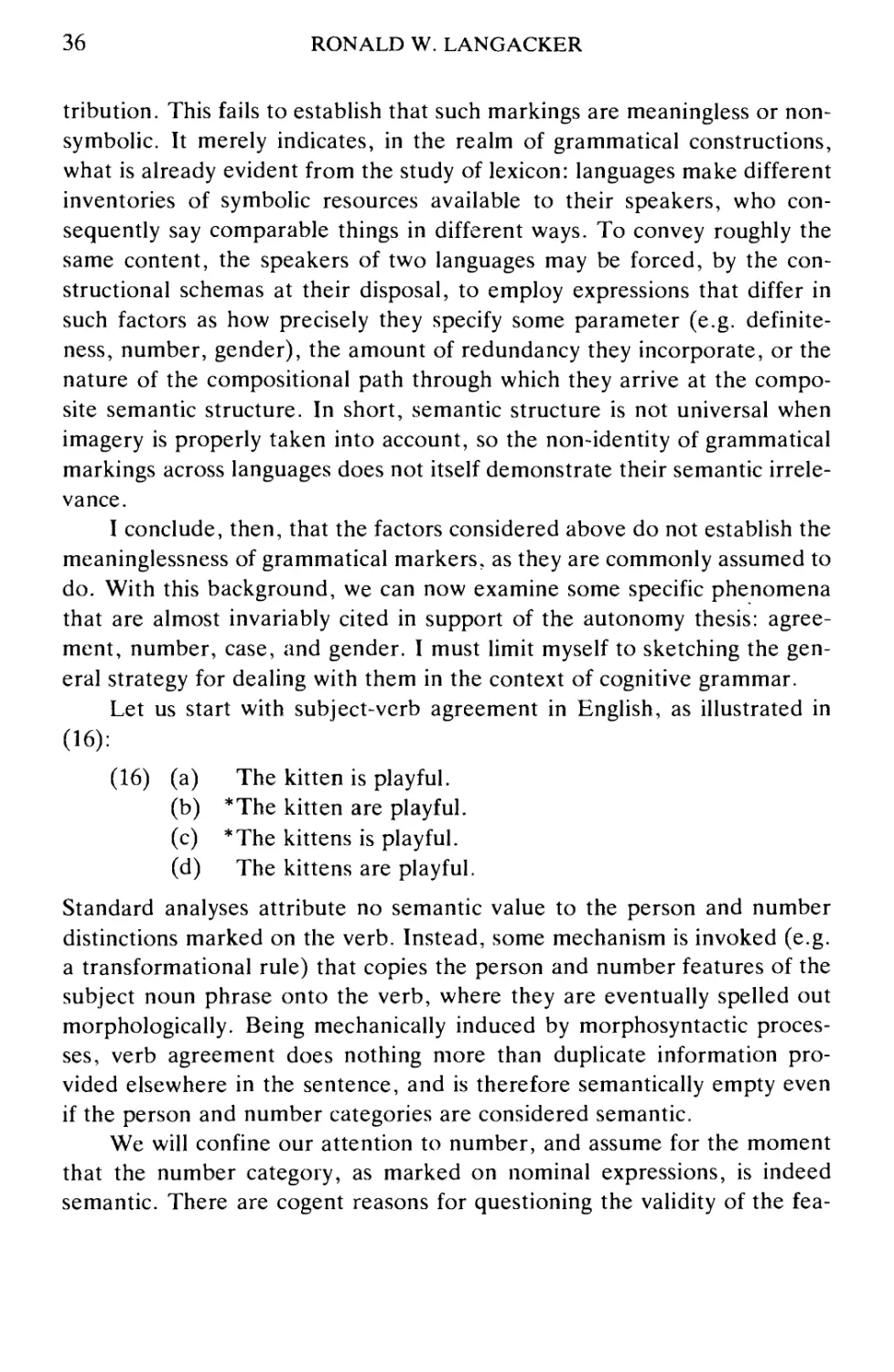

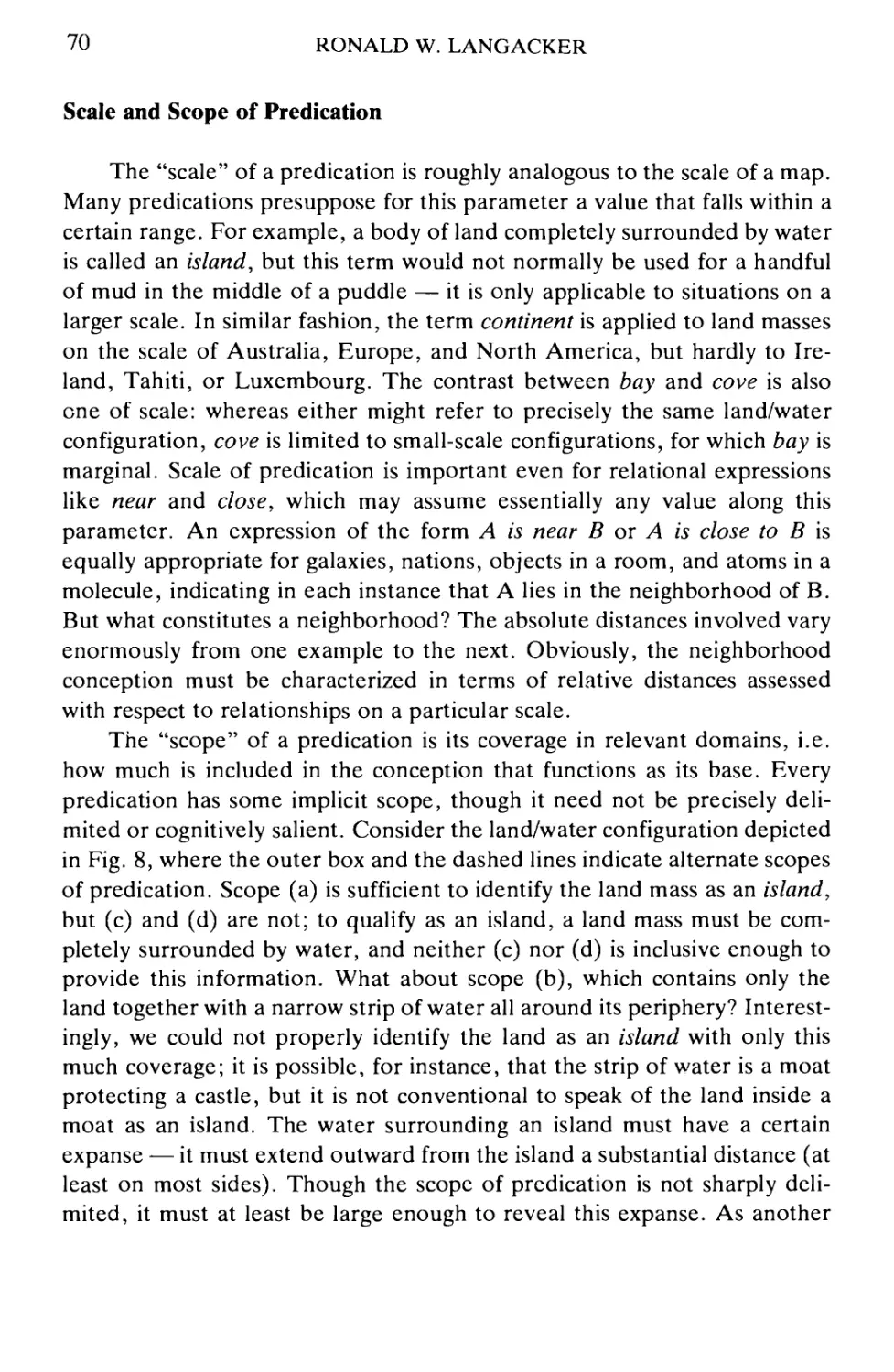

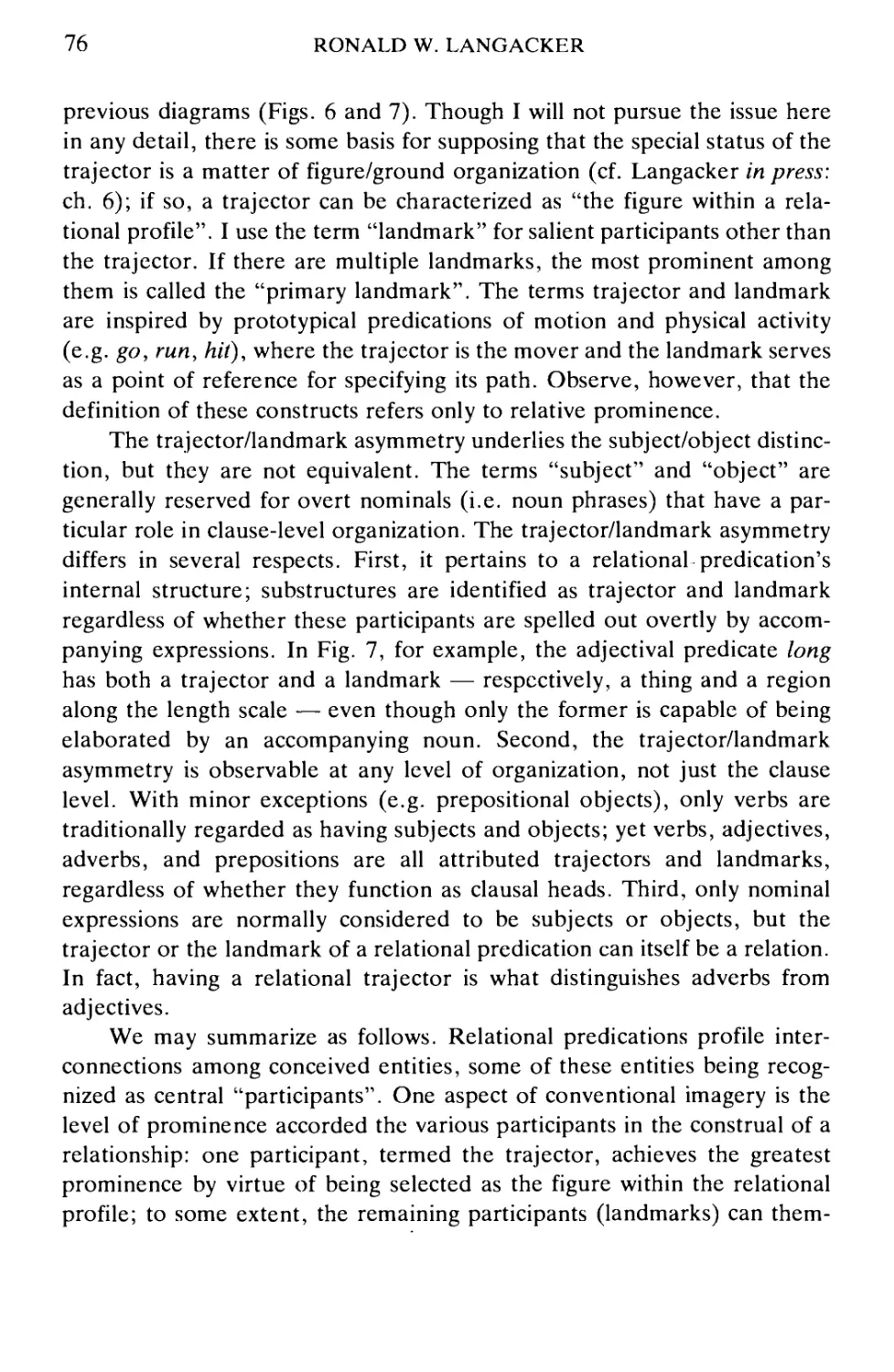

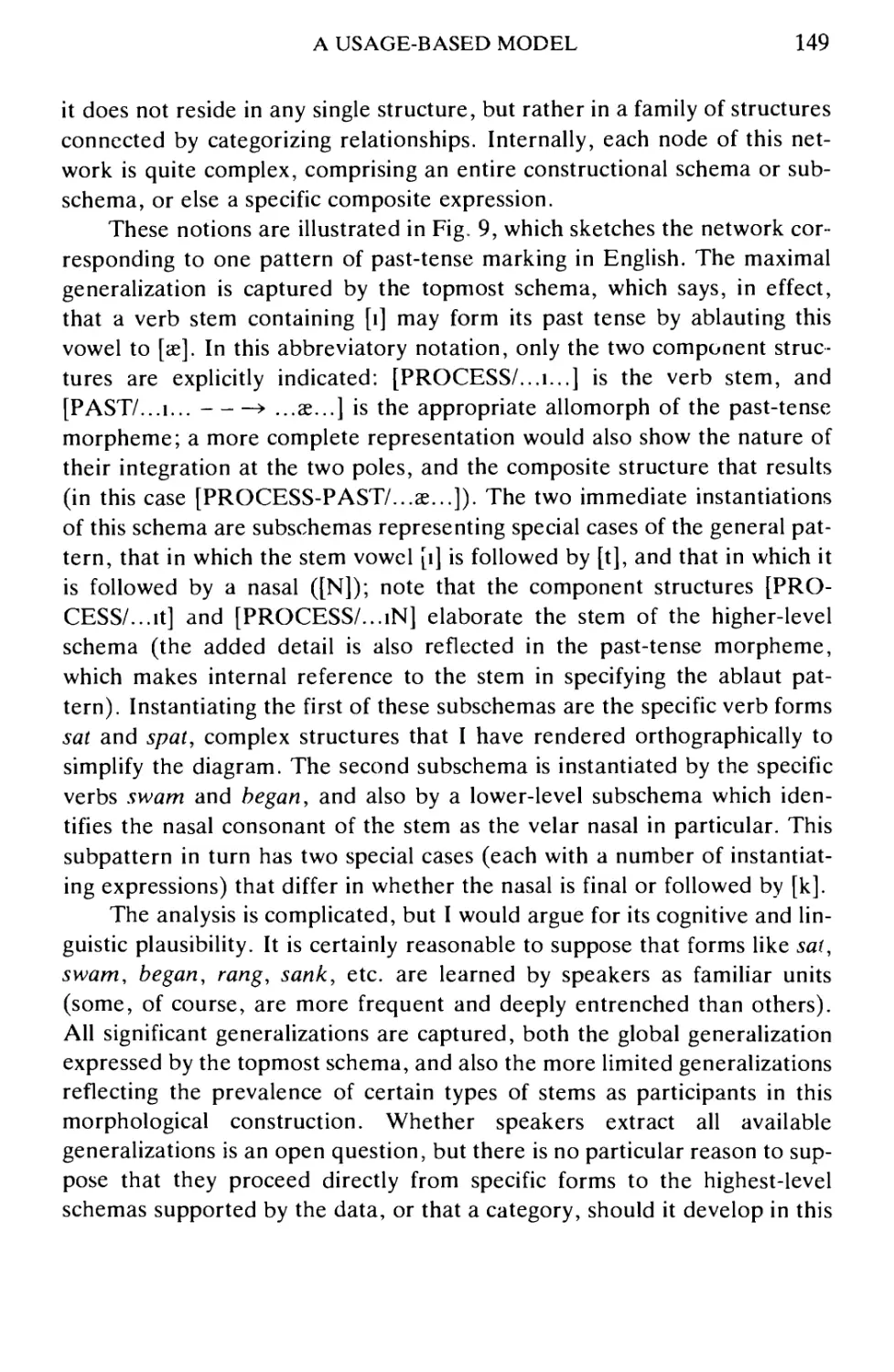

The basic scheme is sketched in Fig. 2(a). The language user brings

many kinds of knowledge and abilities to bear on the task of constructing

and understanding a linguistic expression; these include the conventional

symbolic units provided by the grammar, general knowledge, knowledge of

the immediate context, communicative objectives, esthetic judgments, and

so on. Both the speaker and the addressee face the "coding" problem:

given the resources at their disposal, they must successfully accommodate a

"usage event". The semantic pole of the usage event is identified as the

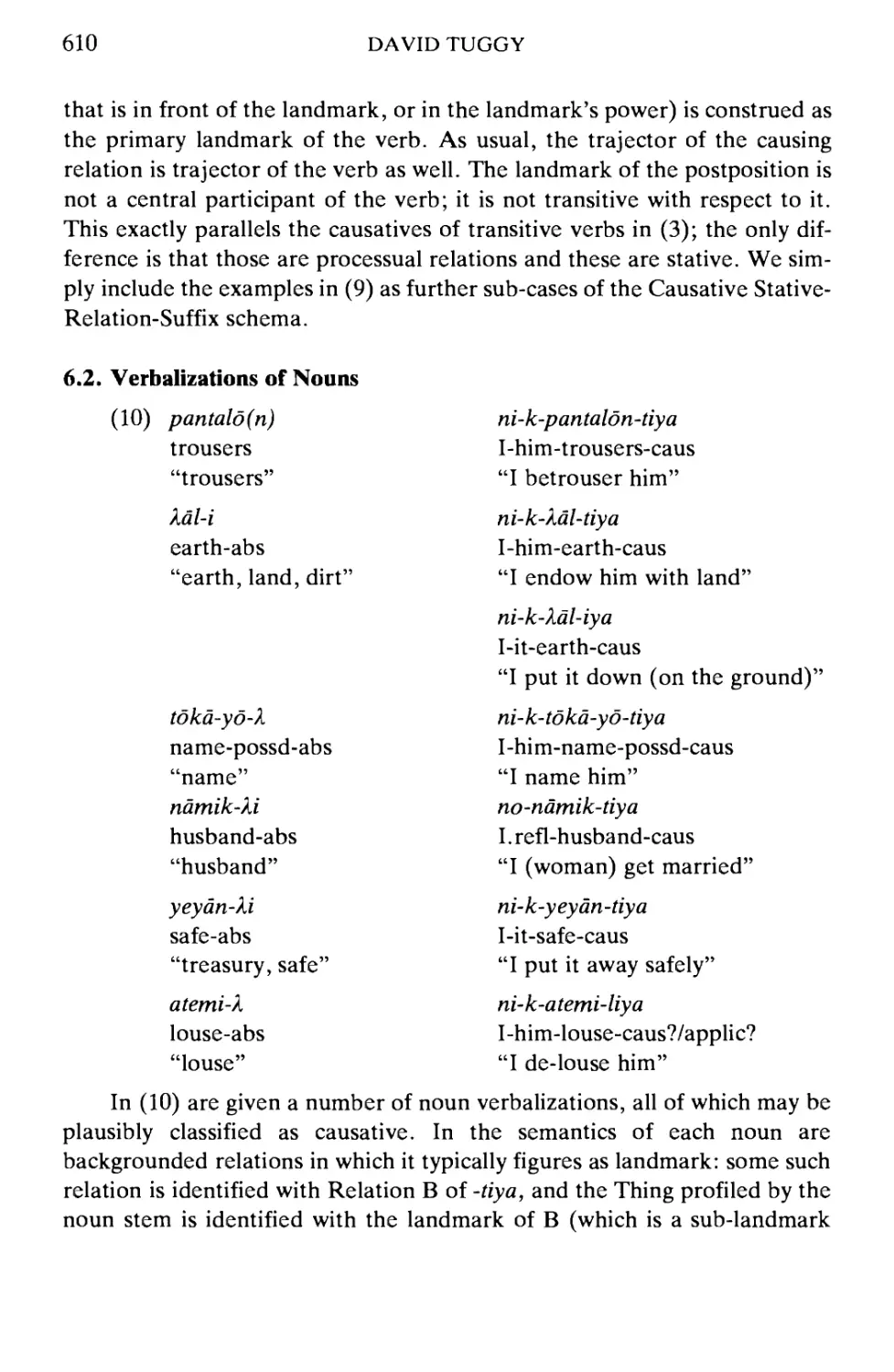

detailed conceptualization that constitutes the expression's full contextual

value, i.e. how it is actually understood in context. The phonological pole

of the usage event is the actual vocalization employed to symbolize this

conception, in all its phonetic detail. Roughly, the speaker starts from the

conceptualization and must arrive at the proper vocalization, while the

addressee proceeds in the opposite direction (encoding vs. decoding). However

both of them, by employing the varied resources at hand, must deal with

the full, bipolar usage event for its occurrence to amount to a meaningful

symbolic experience. Doing so necessarily involves categorization and

problem-solving more generally.

(a)

symbolic units (G)

general knowledge

knowledge of context

communicative objectives

esthetic judgment

etc.

CODING

problem-solving

categorization

RESOURCES

USAGE EVENT

(o)

other

symbolic j_

units L^kh

(inactive)

SU

GRAMMAR

^r^

)~

(COMPOSITIONAL VALUE)

Figure 2

I USAGE \

' **1 EVENT I

ACTUAL

CONTEXTUAL

VALUE

One facet of this coding operation, namely the relation between the

grammar and the usage event, is diagrammed in Fig. 2(b). In arriving at the

usage event, and evaluating it with respect to linguistic convention, the

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

15

speaker or addressee must select a particular array of symbolic units (SU)

and activate them for this purpose; I take it that the cognitive reality of

linguistic units (and their activation in language use) is self-evident and uncon-

troversial. Moreover, since the usage event is identified as the utterance

itself and how it is actually understood in context, it is obviously real — by

definition the usage event does in fact occur. The only facet of Fig. 2(b)

whose status is uncertain is the intervening structure, representing the

"compositional value" of the expression, i.e. the value that could, in

principle, be obtained by algorithmic computation based solely on the

conventional values of the symbolic units employed. It is not unlikely that the

language user computes this compositional value as one step in the coding

process leading to the full usage event. Whether he does so consistently or only

on certain occasions is something we presently have no way of knowing.

What is, however, clear is that the usage event is not in general

equivalent to the compositional value. It is virtually always more specific than

anything strictly predictable from established symbolic units, and thus

represents an elaboration or "specialization" of the compositional value; or

else it conflicts in some way with the compositional value and thus

constitutes an "extension" from it. This departure of the usage event from the

hypothetical compositional value, whether by elaboration or by extension,

reflects the contribution to the coding process of extra-grammatical

resources deployed by the language user.

An example of extension is a novel metaphor, e.g. the use of cabbage

harvester to designate a guillotine. The compositional semantic value of this

expression is roughly 'something that harvests cabbage'; its actual,

contextual semantic value is 'guillotine'; the comparison of these two values,

serving to register their points of similarity and conflict (and thus responsible

for the expression being perceived as metaphoric), is a type of categorizing

judgment; and the symbolic units activated in the coding process include

the lexical items cabbage and harvester, as well as the schematic symbolic

unit representing the relevant pattern of compound formation.

As an example of specialization, suppose I show you a new gadget,

used to sharpen chalk, and refer to it as a chalk sharpener. The

compositional value of this expression is simply 'something that sharpens chalk', but

in context — where you actually see the gadget — your understanding of

this novel expression is far more detailed: you see that it is a mechanical

device, and not a person; you note its approximate size; you may observe

how it operates; and so on. All of this constitutes the expression's contex-

16

RONALD W. LANGACKER

tual semantic value, the semantic pole of the usage event. As is typically the

case, the compositional value substantially "underspecifies" this contextual

value, i.e. the former is schematic for the latter in the categorizing

relationship between the two.

Suppose, now, that the gadget I have shown you becomes widely used,

and that the term chalk sharpener establishes itself as the conventional term

for this type of object. The conventional semantic value of this lexical item

now includes many of those specifications that represented

non-compositional facets of its contextual value when the expression first occurred.

(This is precisely what happened with pencil sharpener, which means not

just 'something that sharpens pencils', but is further understood as

indicating a particular sort of mechanical device.) The implication of this type of

development ought to be apparent: since the non-compositional aspects of

an expression's meaning are part of its contextual value (i.e. how it is

actually understood) the very first time it occurs, and further become part of its

conventional value when it is established as a unit in the grammar, it is

pointless (indeed misguided) to arbitrarily exclude these facets of its

meaning from the domain of linguistic semantics. Moreover, conventionalization

is a matter of degree; there is no particular threshold at which

non-compositional specifications suddenly undergo a change in status from being extra-

linguistic to being conventional and hence linguistic. The process is gradual,

and is initiated when the expression is first employed.

This discrepancy between compositional and contextual value is not

limited to short expressions of the sort that conventionalize as lexical items;

it is characteristic of novel sentences as well. Far more is contributed to the

understanding of a sentence by context and general knowledge (and far less

by compositional principles) than is normally acknowledged. For instance,

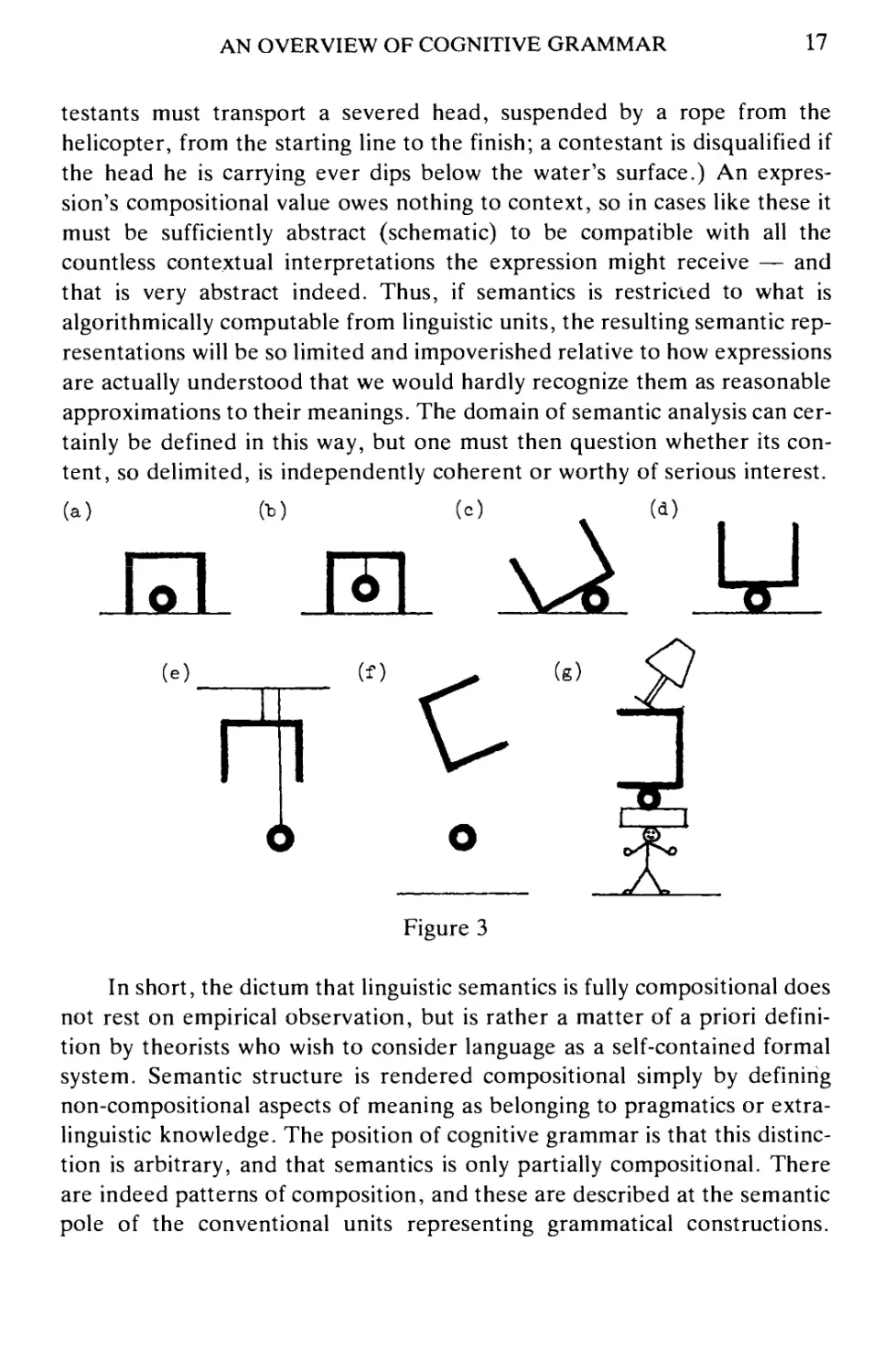

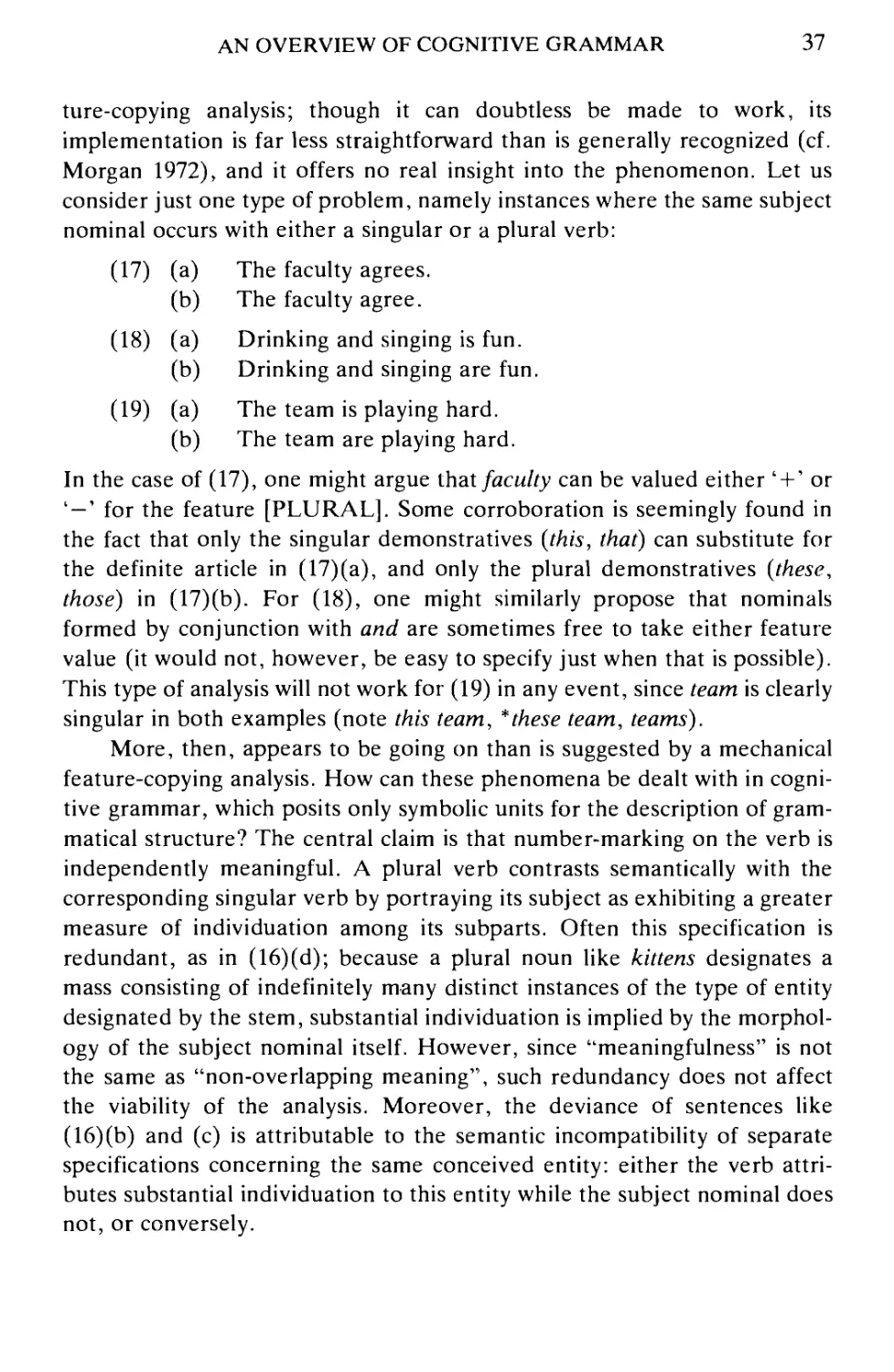

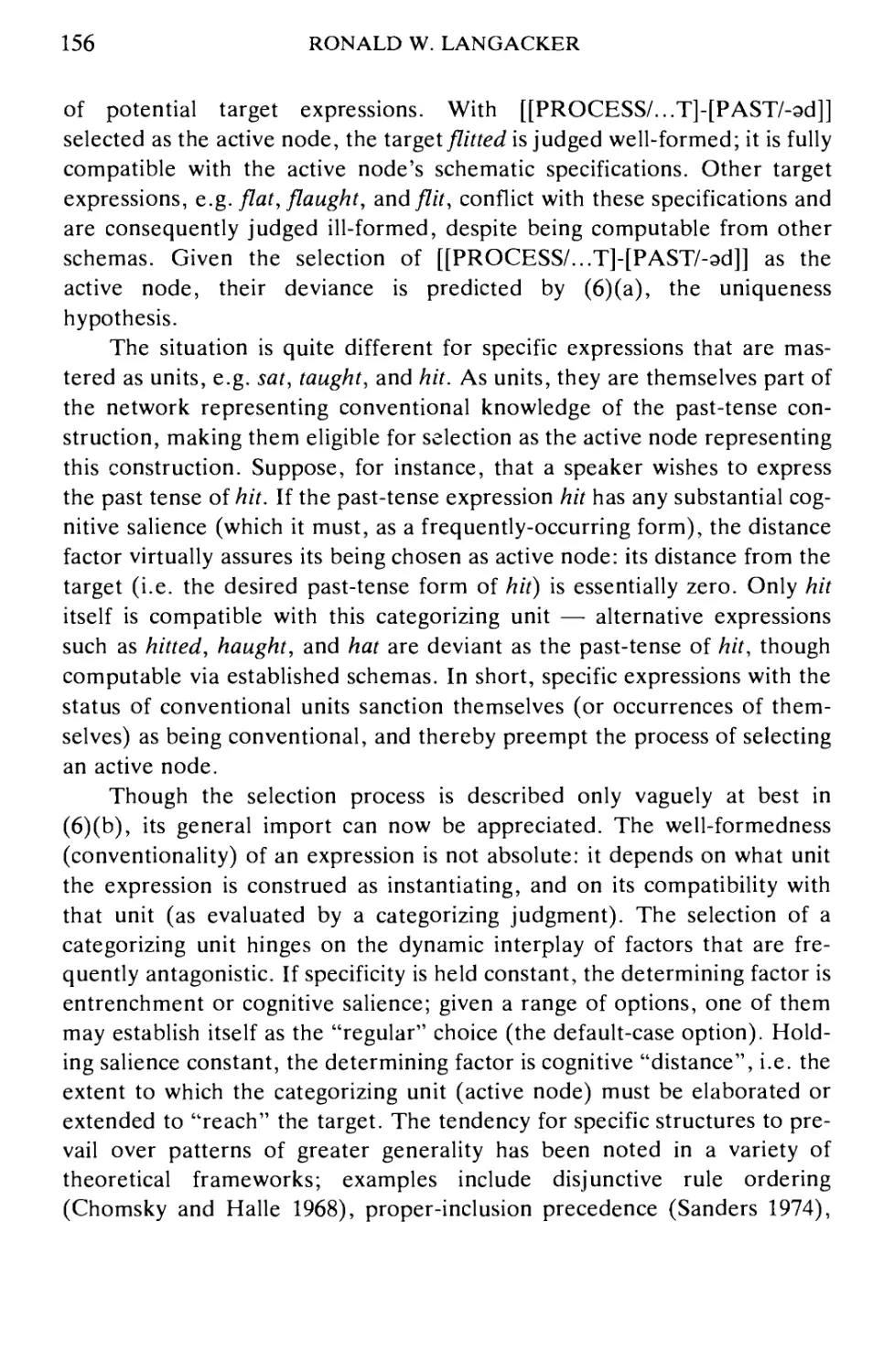

(1 l)(a) would generally be interpreted in the fashion of Fig. 3(a), but given

the appropriate context it could easily be used and understood for any of

the situations in 3(b)-(g) and indefinitely many others.

(11) (a) The ball is under the table.

(b) He is barely keeping his head above the water.

While (ll)(b) evokes the conception of somebody struggling to keep afloat

while swimming, this conception cannot be derived by regular

compositional principles from the conventional meanings of its component lexical

items; in another context, the sentence could be understood in a radically

different way. (Imagine a race over the ocean by helicopter, where the con-

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

17

testants must transport a severed head, suspended by a rope from the

helicopter, from the starting line to the finish; a contestant is disqualified if

the head he is carrying ever dips below the water's surface.) An

expression's compositional value owes nothing to context, so in cases like these it

must be sufficiently abstract (schematic) to be compatible with all the

countless contextual interpretations the expression might receive — and

that is very abstract indeed. Thus, if semantics is restricted to what is

algorithmically computable from linguistic units, the resulting semantic

representations will be so limited and impoverished relative to how expressions

are actually understood that we would hardly recognize them as reasonable

approximations to their meanings. The domain of semantic analysis can

certainly be defined in this way, but one must then question whether its

content, so delimited, is independently coherent or worthy of serious interest.

Figure 3

In short, the dictum that linguistic semantics is fully compositional does

not rest on empirical observation, but is rather a matter of a priori

definition by theorists who wish to consider language as a self-contained formal

system. Semantic structure is rendered compositional simply by defining

non-compositional aspects of meaning as belonging to pragmatics or extra-

linguistic knowledge. The position of cognitive grammar is that this

distinction is arbitrary, and that semantics is only partially compositional. There

are indeed patterns of composition, and these are described at the semantic

pole of the conventional units representing grammatical constructions.

18

RONALD W. LANGACKER

However, the meaning of a complex expression (whatever its degree of

conventionalization) is recognized as a distinct entity not in general

algorithmically derivable from the meanings of its parts. Its compositional

value (assuming for sake of discussion the coherence of this notion) need

not always be separately computed, and if it is, this computation is only one

step in arriving at how the expression is actually understood.

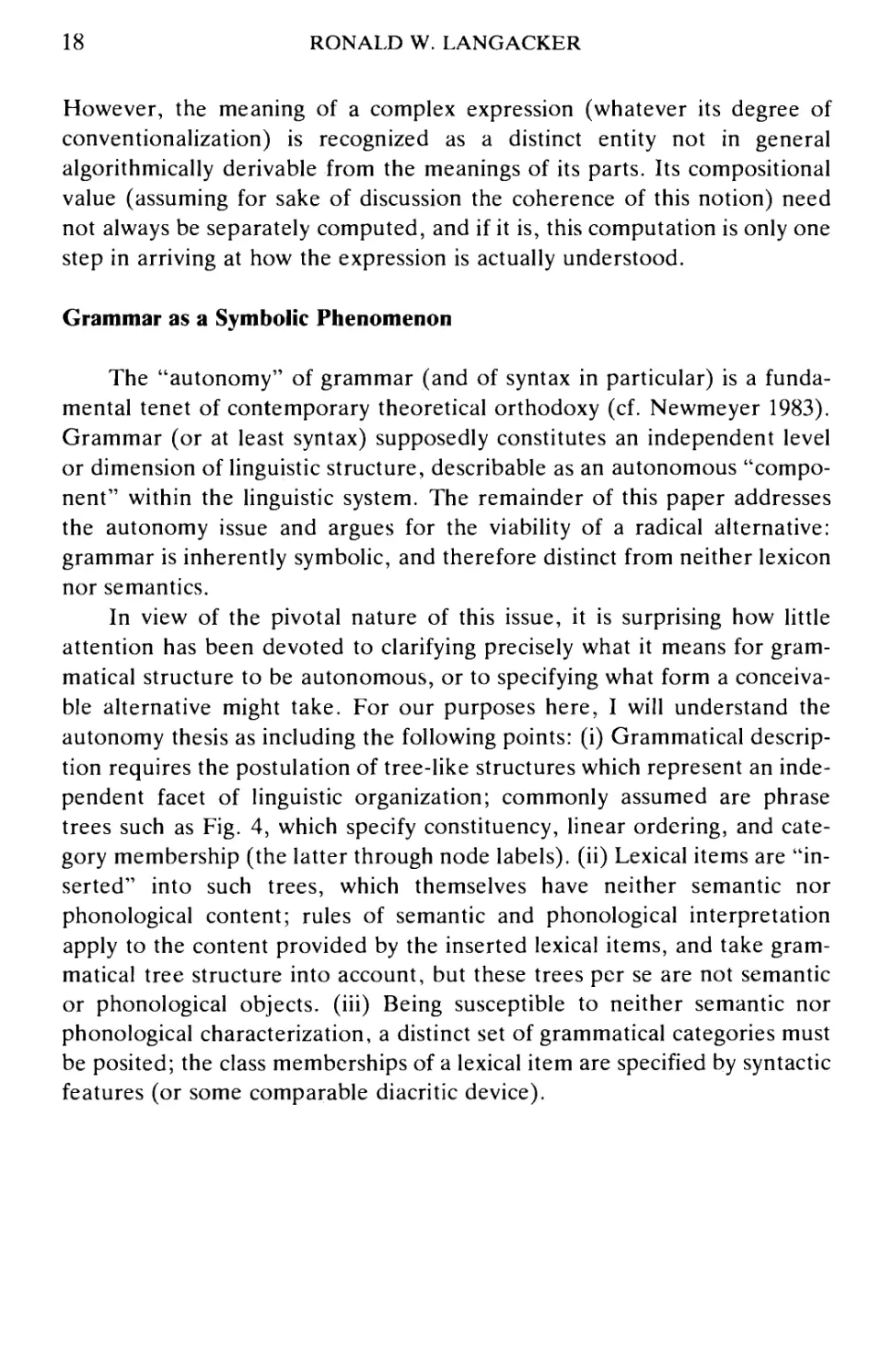

Grammar as a Symbolic Phenomenon

The "autonomy" of grammar (and of syntax in particular) is a

fundamental tenet of contemporary theoretical orthodoxy (cf. Newmeyer 1983).

Grammar (or at least syntax) supposedly constitutes an independent level

or dimension of linguistic structure, describable as an autonomous

"component" within the linguistic system. The remainder of this paper addresses

the autonomy issue and argues for the viability of a radical alternative:

grammar is inherently symbolic, and therefore distinct from neither lexicon

nor semantics.

In view of the pivotal nature of this issue, it is surprising how little

attention has been devoted to clarifying precisely what it means for

grammatical structure to be autonomous, or to specifying what form a

conceivable alternative might take. For our purposes here, I will understand the

autonomy thesis as including the following points: (i) Grammatical

description requires the postulation of tree-like structures which represent an

independent facet of linguistic organization; commonly assumed are phrase

trees such as Fig. 4, which specify constituency, linear ordering, and

category membership (the latter through node labels), (ii) Lexical items are

"inserted" into such trees, which themselves have neither semantic nor

phonological content; rules of semantic and phonological interpretation

apply to the content provided by the inserted lexical items, and take

grammatical tree structure into account, but these trees per se are not semantic

or phonological objects, (iii) Being susceptible to neither semantic nor

phonological characterization, a distinct set of grammatical categories must

be posited; the class memberships of a lexical item are specified by syntactic

features (or some comparable diacritic device).

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

19

Figure 4

The proposed alternative does not employ phrase trees and rejects

points (i)-(iii). It claims that grammar (both morphology and syntax) is

describable using only symbolic elements, each of which has both a

semantic and a phonological pole. The symbolic units characterizing grammatical

structure form a continuum with lexicon: while they differ from typical

lexical items with respect to such factors as complexity and abstractness, the

differences are only a matter of degree, and lexical items themselves range

widely along these parameters. I will therefore begin my presentation of the

alternative view with a brief discussion of lexical units.

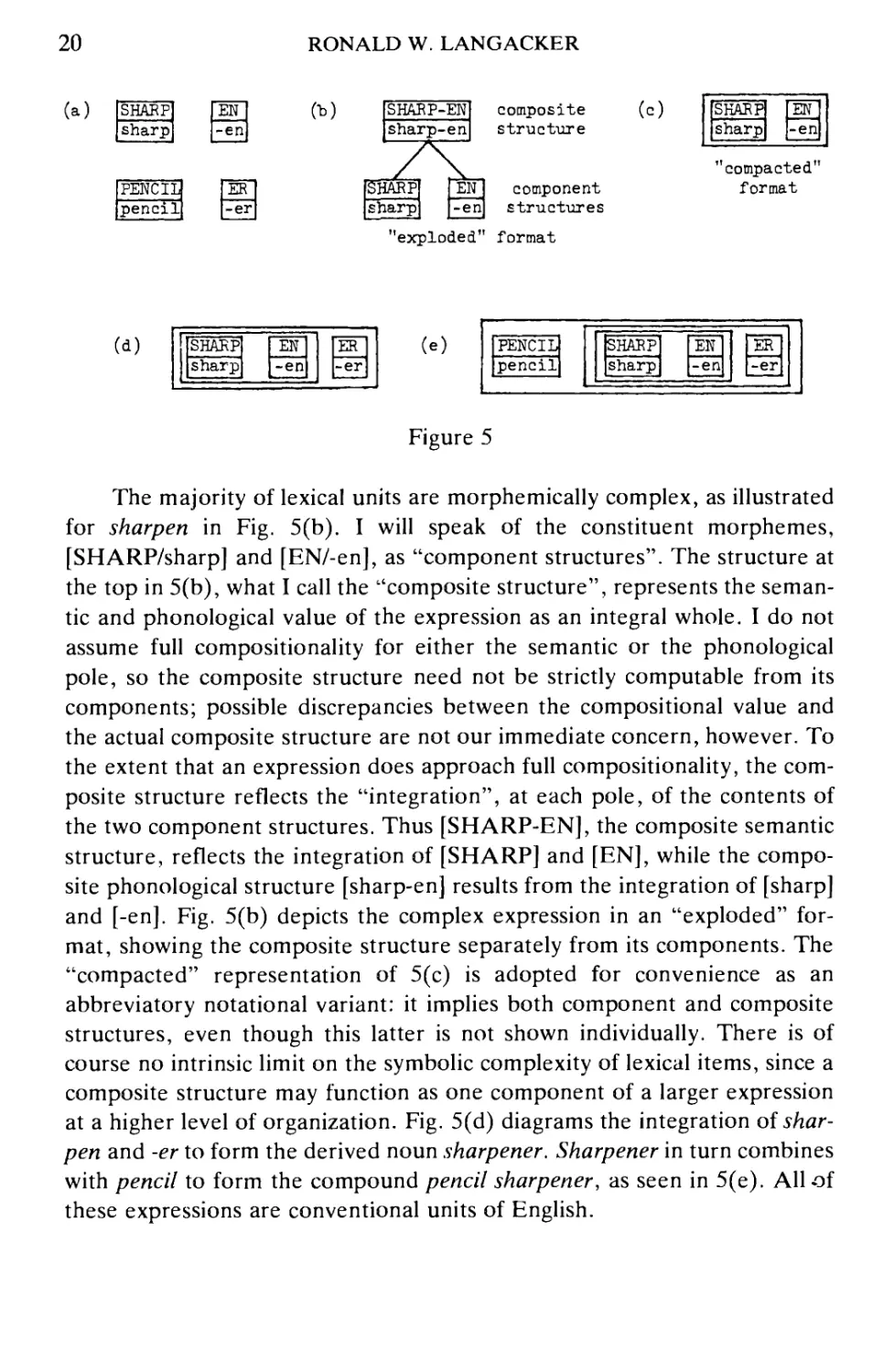

Lexical items vary greatly in their internal complexity. We are

concerned here in particular with "symbolic complexity", i.e. whether an item

decomposes into smaller symbolic units. Those which do not, and are

consequently minimal from the symbolic standpoint, are known as

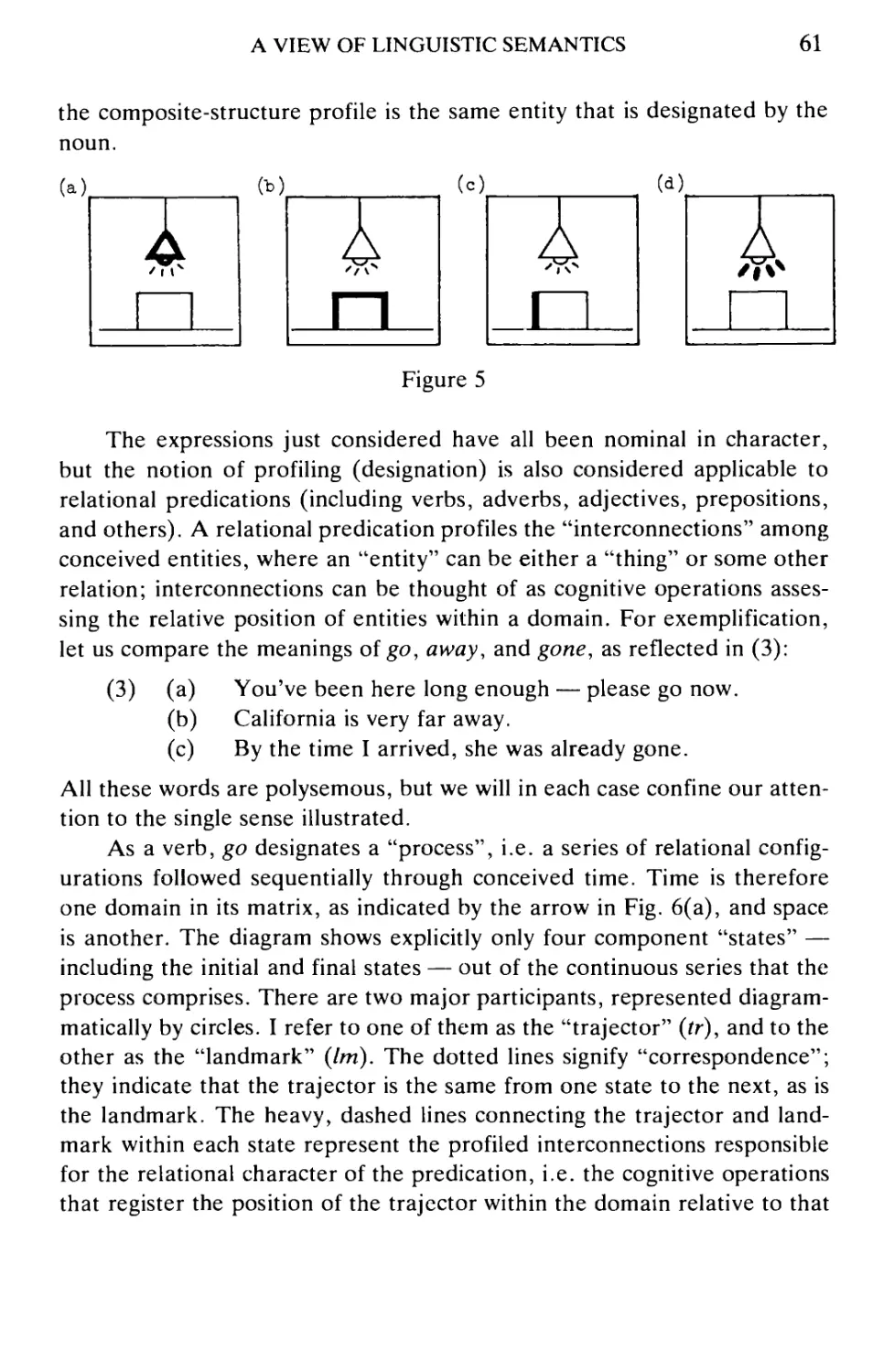

"morphemes". Examples are given in Fig. 5(a), which illustrates the notations I

will use here for symbolic units: the semantic pole is shown at the top, its

content indicated by capital letters (thus SHARP abbreviates the meaning

of sharp); the phonological pole is shown at the bottom (orthographic

representations suffice for present purposes); the line between the two poles

stands for their symbolic relationship; and the box enclosing them indicates

that the symbolic structure as a whole has the status of a conventional unit.

20

RONALD W. LANGACKER

(a)

SHARP!

sharp]

IPENCII

pencil

J

en!

-en]

|er

|-er

ft)

SHARP-EN

sharp-en

/

SHARP

sharp

x

EN

-en

composite

structure

component

structures

(c)

"exploded" format

[[SHARP

Jsharp

-en)

"compacted"

format

(d)

| [SHARP

|| sharp

~en~|

-en|

er]

-erl

(e)

PENCIL^

pencil]

SHARP

[sharp

EN

-enl

ER

-er

Figure 5

The majority of lexical units are morphemically complex, as illustrated

for sharpen in Fig. 5(b). I will speak of the constituent morphemes,

[SHARP/sharp] and [EN/-en], as "component structures". The structure at

the top in 5(b), what I call the ''composite structure", represents the

semantic and phonological value of the expression as an integral whole. I do not

assume full compositionality for either the semantic or the phonological

pole, so the composite structure need not be strictly computable from its

components; possible discrepancies between the compositional value and

the actual composite structure are not our immediate concern, however. To

the extent that an expression does approach full compositionality, the

composite structure reflects the "integration", at each pole, of the contents of

the two component structures. Thus [SHARP-EN], the composite semantic

structure, reflects the integration of [SHARP] and [EN], while the

composite phonological structure [sharp-en] results from the integration of [sharp]

and [-en]. Fig. 5(b) depicts the complex expression in an "exploded"

format, showing the composite structure separately from its components. The

"compacted" representation of 5(c) is adopted for convenience as an

abbreviatory notational variant: it implies both component and composite

structures, even though this latter is not shown individually. There is of

course no intrinsic limit on the symbolic complexity of lexical items, since a

composite structure may function as one component of a larger expression

at a higher level of organization. Fig. 5(d) diagrams the integration of

sharpen and -er to form the derived noun sharpener. Sharpener in turn combines

with pencil to form the compound pencil sharpener, as seen in 5(e). All of

these expressions are conventional units of English.

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

21

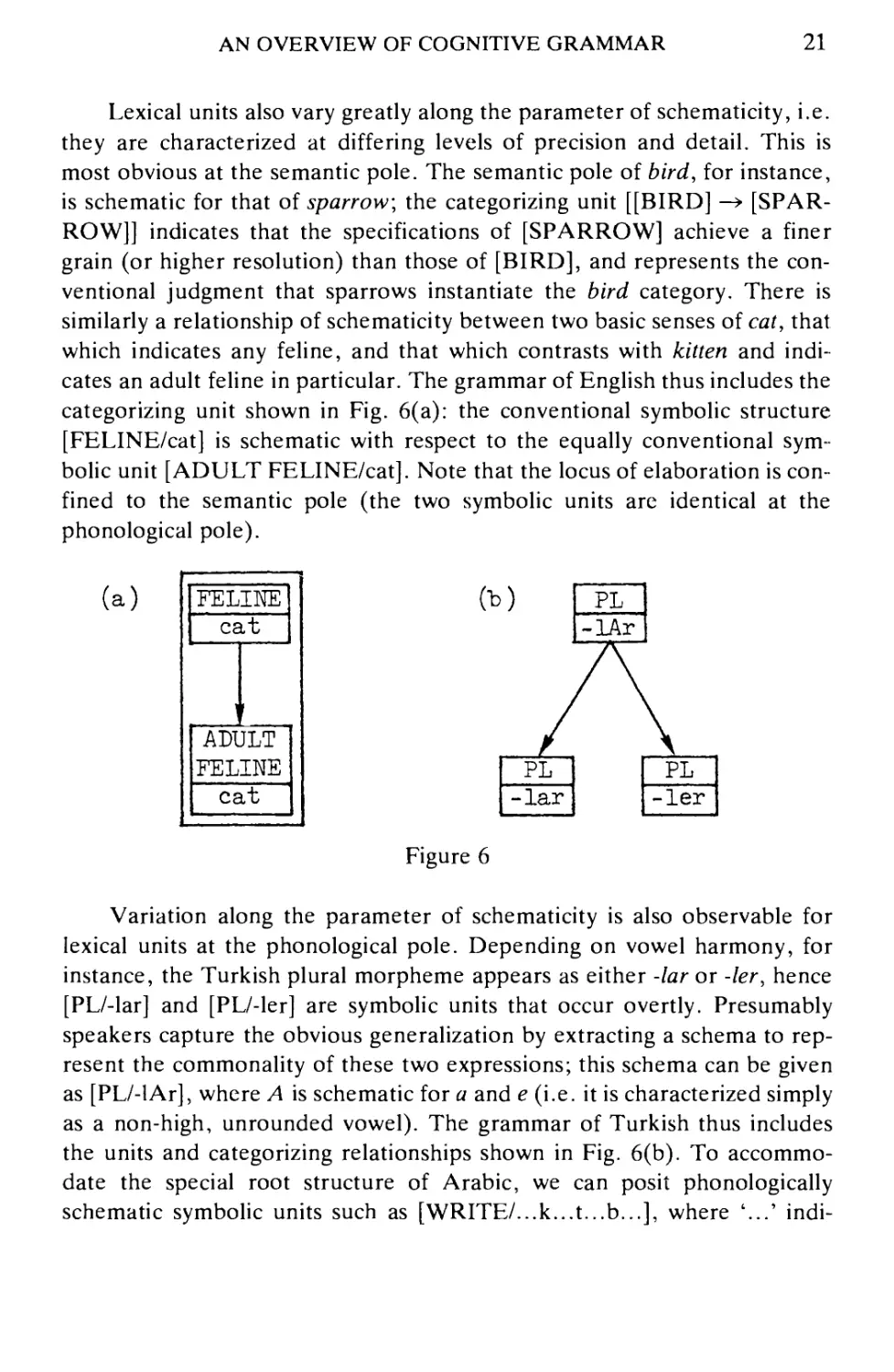

Lexical units also vary greatly along the parameter of schematicity, i.e.

they are characterized at differing levels of precision and detail. This is

most obvious at the semantic pole. The semantic pole of bird, for instance,

is schematic for that of sparrow, the categorizing unit [[BIRD] -»

[SPARROW]] indicates that the specifications of [SPARROW] achieve a finer

grain (or higher resolution) than those of [BIRD], and represents the

conventional judgment that sparrows instantiate the bird category. There is

similarly a relationship of schematicity between two basic senses of cat, that

which indicates any feline, and that which contrasts with kitten and

indicates an adult feline in particular. The grammar of English thus includes the

categorizing unit shown in Fig. 6(a): the conventional symbolic structure

[FELINE/cat] is schematic with respect to the equally conventional

symbolic unit [ADULT FELINE/cat]. Note that the locus of elaboration is

confined to the semantic pole (the two symbolic units are identical at the

phonological pole).

(a)

FELINE

cat

ADULT

FELINE

cat

PL"

| -lar

" PL

-ler J

Figure 6

Variation along the parameter of schematicity is also observable for

lexical units at the phonological pole. Depending on vowel harmony, for

instance, the Turkish plural morpheme appears as either -lar or -ler, hence

[PL/-lar] and [PL/-ler] are symbolic units that occur overtly. Presumably

speakers capture the obvious generalization by extracting a schema to

represent the commonality of these two expressions; this schema can be given

as [PL/-lAr], where A is schematic for a and e (i.e. it is characterized simply

as a non-high, unrounded vowel). The grammar of Turkish thus includes

the units and categorizing relationships shown in Fig. 6(b). To

accommodate the special root structure of Arabic, we can posit phonologically

schematic symbolic units such as [WRITE/...k...t...b...], where '...' indi-

22

RONALD W. LANGACKER

cates the possible occurrence of a vowel (but does not specify its quality).

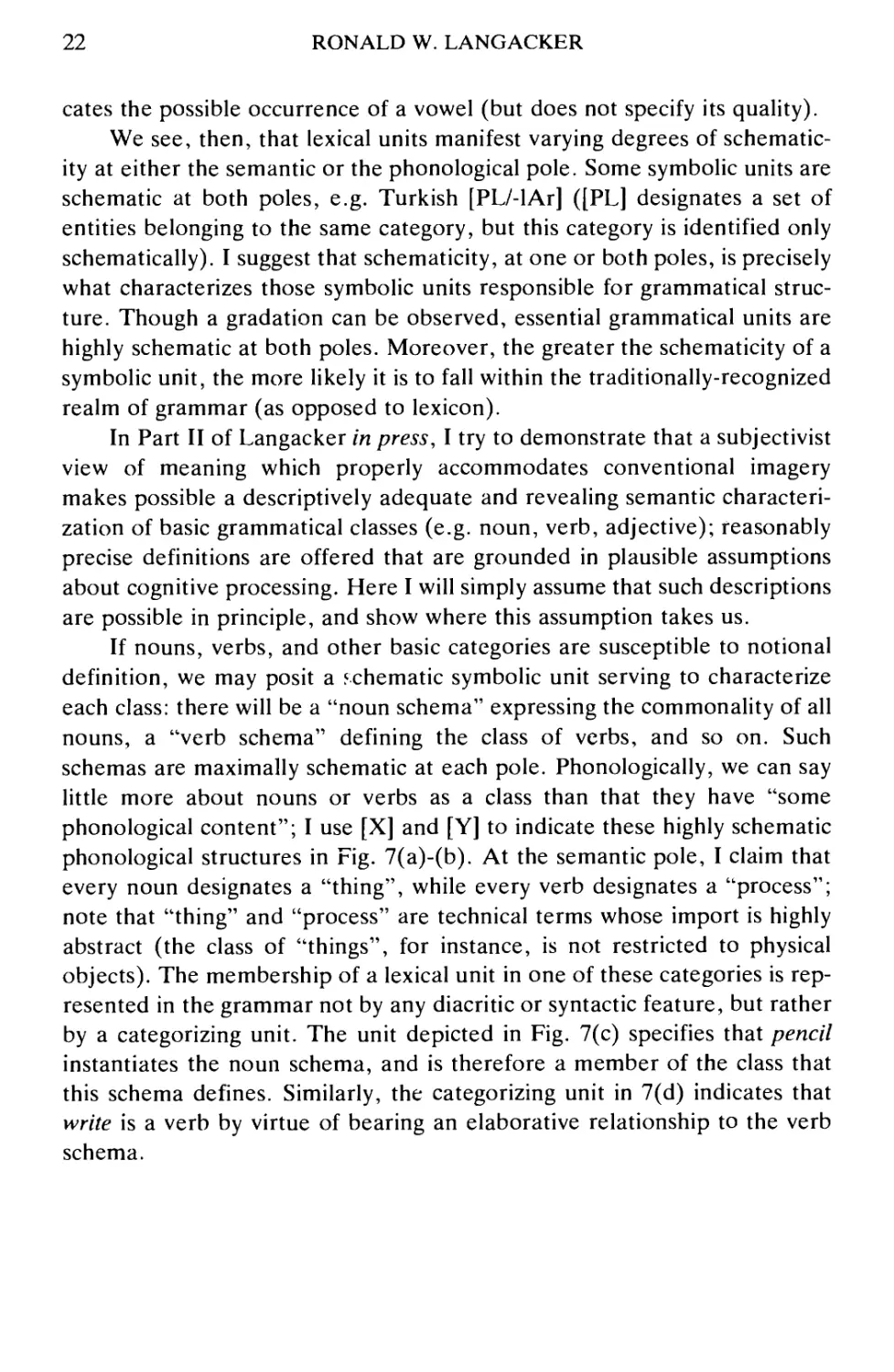

We see, then, that lexical units manifest varying degrees of schematic-

ity at either the semantic or the phonological pole. Some symbolic units are

schematic at both poles, e.g. Turkish [PLAlAr] ([PL] designates a set of

entities belonging to the same category, but this category is identified only

schematically). I suggest that schematicity, at one or both poles, is precisely

what characterizes those symbolic units responsible for grammatical

structure. Though a gradation can be observed, essential grammatical units are

highly schematic at both poles. Moreover, the greater the schematicity of a

symbolic unit, the more likely it is to fall within the traditionally-recognized

realm of grammar (as opposed to lexicon).

In Part II of Langacker in press, I try to demonstrate that a subjectivist

view of meaning which properly accommodates conventional imagery

makes possible a descriptively adequate and revealing semantic

characterization of basic grammatical classes (e.g. noun, verb, adjective); reasonably

precise definitions are offered that are grounded in plausible assumptions

about cognitive processing. Here I will simply assume that such descriptions

are possible in principle, and show where this assumption takes us.

If nouns, verbs, and other basic categories are susceptible to notional

definition, we may posit a schematic symbolic unit serving to characterize

each class: there will be a "noun schema" expressing the commonality of all

nouns, a "verb schema" defining the class of verbs, and so on. Such

schemas are maximally schematic at each pole. Phonologically, we can say

little more about nouns or verbs as a class than that they have "some

phonological content"; I use [X] and [Y] to indicate these highly schematic

phonological structures in Fig. 7(a)-(b). At the semantic pole, I claim that

every noun designates a "thing", while every verb designates a "process";

note that "thing" and "process" are technical terms whose import is highly

abstract (the class of "things", for instance, is not restricted to physical

objects). The membership of a lexical unit in one of these categories is

represented in the grammar not by any diacritic or syntactic feature, but rather

by a categorizing unit. The unit depicted in Fig. 7(c) specifies that pencil

instantiates the noun schema, and is therefore a member of the class that

this schema defines. Similarly, the categorizing unit in 7(d) indicates that

write is a verb by virtue of bearing an elaborative relationship to the verb

schema.

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

23

(a)

(b)

[THING]

I X 1

[PROCESS

1 Y

noun (c)

s chema

] verb

1 s chema

1 THING]

1 x 1

, * ,

PENCIL

[pencilj

1 (d)

[PROCESS

1 Y 1

f

IwriteI

|write)1

Figure 7

We see, then, that this framework accommodates basic grammatical

categories and category membership within the restrictive confines of the

content requirement: nothing has been invoked other than specific

symbolic units (e.g. pencil), schematic symbolic units (e.g. the noun schema),

and categorizing relationships between the two. What about grammatical

rules and constructions? These are not distinguished in cognitive grammar,

but are treated instead as alternate ways of regarding the same entities,

namely symbolic units that are both schematic and complex (in the sense of

having smaller symbolic units as components). I refer to these entities as

"constructional schemas".

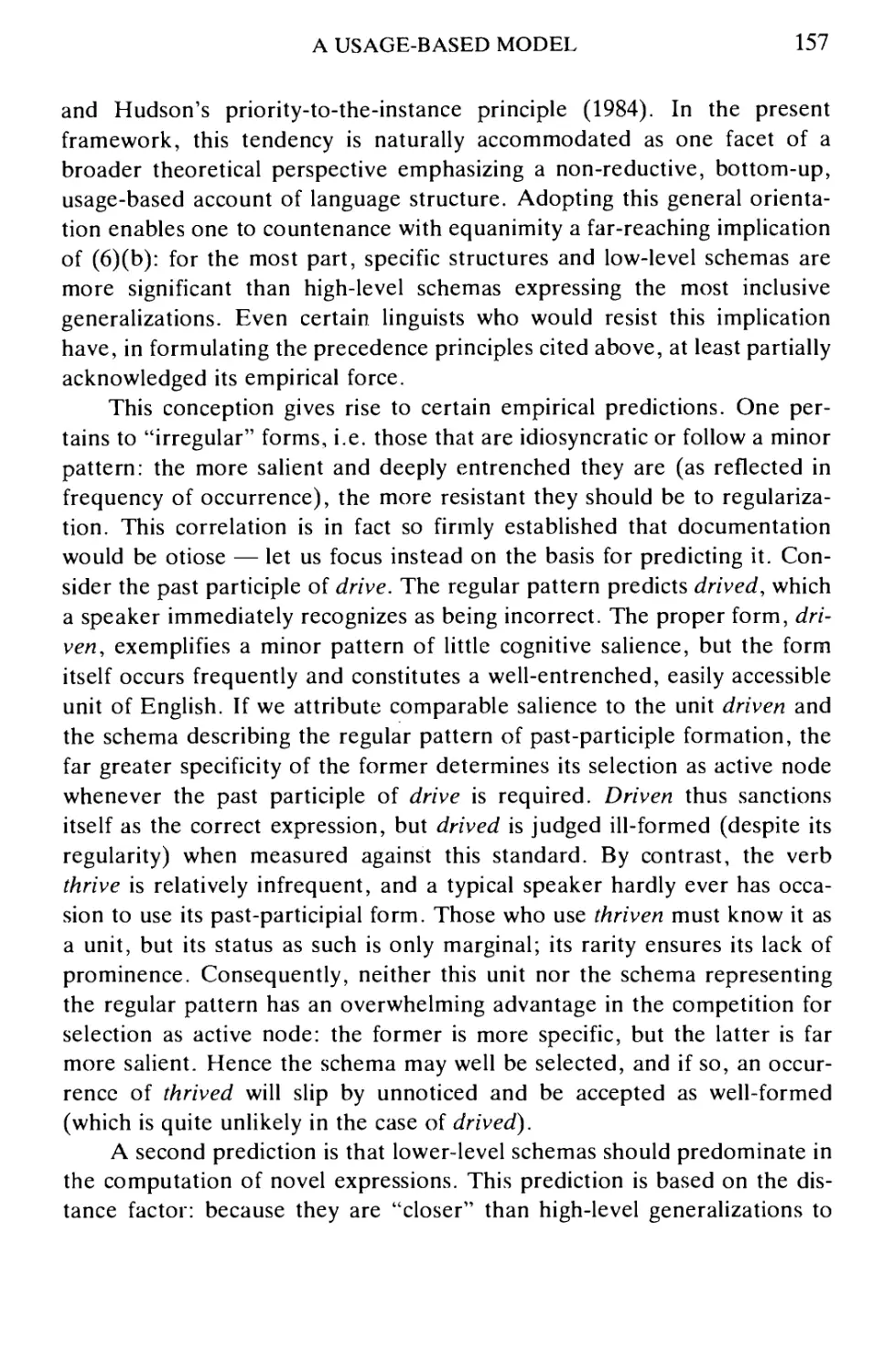

Fig. 8(a) represents the constructional schema for deverbal nominali-

zations in -er {talker, swimmer, complainer, painter, mixer, opener, and so

on). Despite the abbreviatory notations, this structure is a complex

symbolic unit in which component structures are integrated to form a composite

structure at both the semantic and the phonological pole. One component

structure is the verb schema; semantically it designates a process of

unspecified character, while phonologically its content is maximally

schematic. The other component structure is the morpheme -er, which is

specific phonologically but semantically abstract (it designates a "thing"

identified only by the role it plays in a schematic process). The composite

structure (not separately shown in the compacted format of 8(a)) can be

abbreviated as follows: [PROCESS-ER/Y-er]. Semantically, it designates a

thing, and the process in which it plays a specified role is equated with that

designated by the schematic verb stem [PROCESS/Y]. Phonologically, it

specifies the suffixation of -er to the content provided by the stem.

24

RONALD W. LANGACKER

(a)

(b)

: (process)

T Y J

ER

|-er

llTALK

Htalk

er~|

-er]

constructional

schema

instantiation

of schema

[PROCESS

1 Y

1

ER j

-er) 1

i 4 &

Italk]

Italkl

ER 1 j

-er j 1

categorizing

relationship

(structural

description)

Figure 8

In short, the constructional schema is exactly parallel in formation and

internal structure to any of its instantiations, such as talker, diagrammed in

Fig. 8(b); the only difference is that the schematic verb stem in the former

is replaced in the latter by the more elaborate content of talk. The

constructional schema can therefore be regarded as a symbolically-complex

expression, albeit one that is too abstract semantically to be very useful for

communicative purposes, and too abstract phonologically to actually be

pronounced or perceived. Instead it serves a classificatory function, defining

and characterizing a morphological construction by representing the

commonality of its varied instantiations. The relationship between the schema

and a specific instantiating expression resides in a categorizing unit of the

sort depicted in Fig. 8(c). The global categorization, indicated by arrow T,

amounts to a relationship of schematicity: talker elaborates the abstract

specifications of the schema, but is fully compatible with them, and thus

instantiates the morphological pattern the schema describes. This global

categorization can be resolved into local categorizations between particular

substructures. Arrow 42' indicates that talk is categorized as a verb and

elaborates the schematic stem within the constructional schema. The

morpheme -er occurs in both the schema and the specific expressions that

instantiate it; the double-headed solid arrow, labeled '3', marks this

relationship of identity.

A symbolically-complex expression can of course be incorporated as

one component of an expression that is more complex still. A derived verb

like sharpen can therefore function as the stem in the morphological pattern

just described, resulting in sharpener, this noun in turn combines with

pencil in the compound pencil sharpener, whose organization is sketched at the

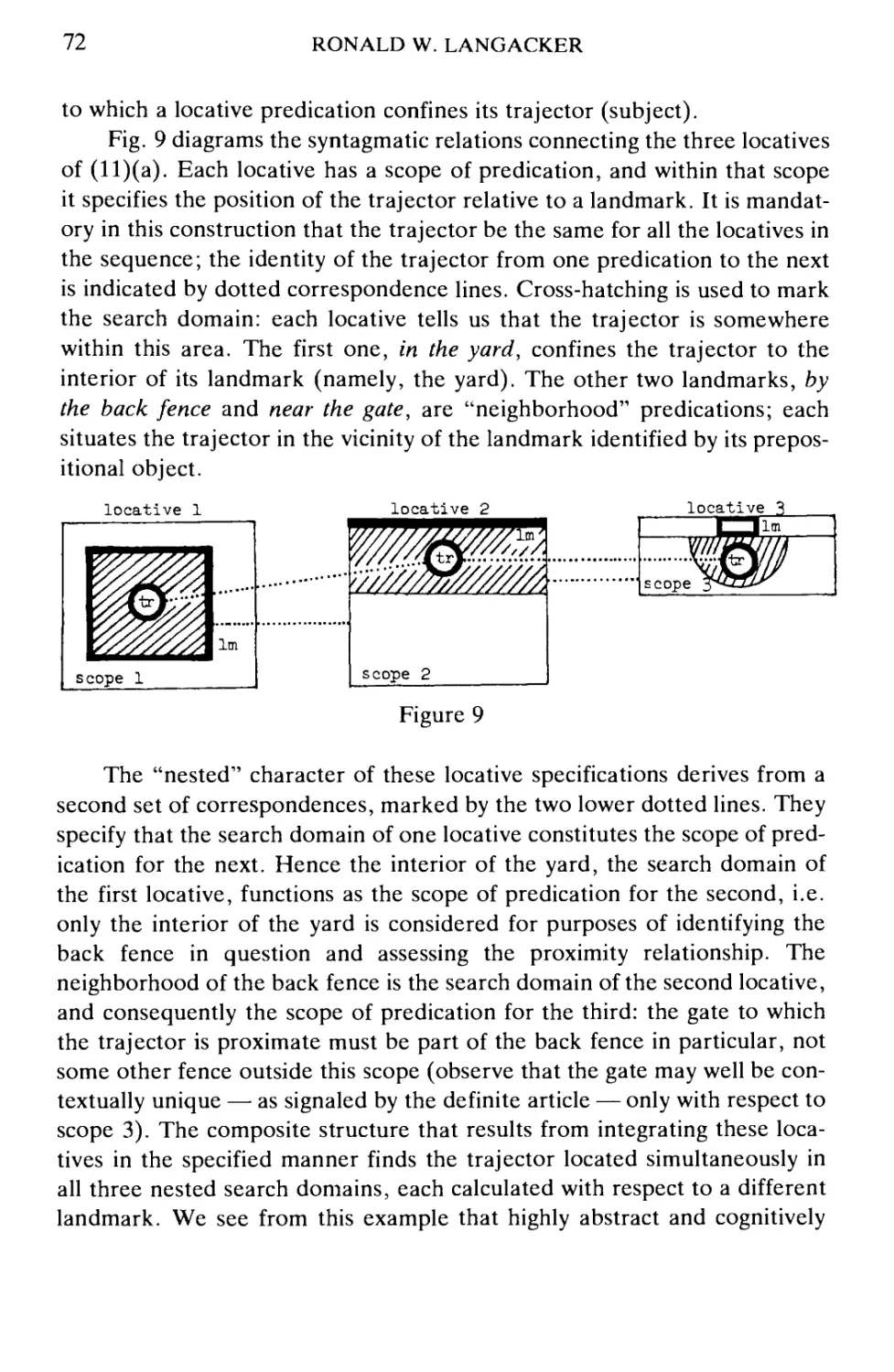

bottom in Fig. 9(a). In the same fashion, one constructional schema is

capable of being incorporated as a component of a larger schema describing

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

25

expressions of greater complexity. At the top in Fig. 9(a), we see the

higher-order constructional schema responsible for expressions like pencil

sharpener, mountain climber, lawn mower, taxi driver, flamethrower, etc.

One of its components is the constructional schema for nominalizations

with -er, as represented in Fig. 8(a); the other component is the noun

schema (cf. Fig. 7(a)). Phonologically, the higher-order schema specifies

the juxtaposition of the two stems to form a compound: [X Y-er]. Semanti-

cally, it specifies that the "thing" symbolized by [X] is equated with the

object of the process symbolized by [Y]. The global categorizing

relationship between this constructional schema and a specific compound like

pencil sharpener reflects local categorizing relationships at different levels of

organization. In Fig. 9(a), arrow '1' again indicates that the overall

relationship is elaborative (i.e. pencil sharpener conforms to the specifications of

the schema but is characterized in finer detail). At a lower hierarchical

level, arrows '2' and '3' show that pencil and sharpener qualify respectively

as instantiations of the noun schema and of the morphological pattern

previously considered. Finally, at the lowest hierarchical level, relationship '3'

is resolved into the local categorizations '4' (which classes sharpen as a

verb) and '5' (an identity relation).

(a)

(THING!

| X |

2

I \

(process

1 Y

~i~.

f

[PENCIL

1 [pencil

ER II

-er II

—i i

k \

I

T

JSHARI

1 JEN ]

(sharp [

-en]

r3

I—»

5

If

, f

"ER

-er|

(t)

THING

CHALK

chalk

PROCESS]

ER

-er|

flSHARP]

1 [sharp)

|EN]!

|-en|

Figure 9

Grammar, I claim, is nothing more than patterns for successively

combining symbolic expressions to form expressions of progressively greater

complexity. These patterns take the form of constructional schemas, some

of which incorporate others as components. Constructional schemas have

multiple functions in this model. First, they capture generalizations by

representing the commonality observed in the formation of specific

instantiating expressions. Second, they provide the basis for categorizing relation-

26

RONALD W. LANGACKER

ships which show the status of specific expressions with respect to structures

and patterns of greater generality. An expression's "structural description"

is simply the set of categorizing relationships in which it participates; for

instance, the structural description of pencil sharpener includes the

categorizing relationships depicted in Fig. 9(a) (together with others not

shown). Finally, a constructional schema serves as a template for the

computation of novel instantiating expressions. Consider a previous example,

namely the coinage of chalk sharpener to designate a previously unfamiliar

gadget. Symbolic resources available to the speaker include the units and

categorizations indicated in Fig. 9(b): the lexical units chalk and sharpen,

their respective categorizations as a noun and a verb, and the constructional

schema representing a compounding pattern. To compute an appropriate

compound, the speaker need only co-activate these structures, i.e. carry out

the elaborative operations relating chalk to the noun schema, and sharpen

to the verb schema, in the setting of the schema for the construction. Of

course, the composite semantic structure obtained in this way will only

approximate the expression's actual, contextually-determined value.

To conclude this section, let us once more consider phrase trees like

Fig. 4, which specify linear ordering, constituency, and constituent types. It

may now be apparent that all three sorts of information are also provided in

the proposed alternative, which posits only symbolic units for the

description of grammatical structure. Linear ordering (actually, temporal

ordering) is simply one dimension of phonological structure. A symbolic

structure — whether simple or complex, specific or schematic — specifies the

temporal sequencing of its phonological components as an inherent part of

the characterization of its phonological pole. Thus sharp, sharpen,

sharpener, and pencil sharpener all specify, as part of their internal phonological

structure, the temporal ordering of their segments, syllables, morphemes,

and stems; the same is true of the schemas which these expressions

instantiate, except that the phonological elements in question are partially

schematic (e.g. the constructional schema of Fig. 8(a) specifies, in its

composite structure, that -er follows the schematically-characterized verb

stem). Syntax and morphology are not sharply distinct in this regard. The

difference between them reduces to whether the construction involves

multiple words at the phonological pole, or parts of a single word (compounds

are thus a borderline case).

Constituency is not a separate facet of linguistic structure, but merely

reflects the order in which symbolic structures are successively combined in

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

27

the formation of a complex expression. We may speak of a "compositional

path" leading from individual morphemes, through intermediate-level

composite structures, to the highest-level composite structure representing the

value of a complex expression overall. The compositional path remains

implicit in "compacted" diagrams like Fig. 9(a), which fail to separately

depict composite structures, but is immediately apparent when these are

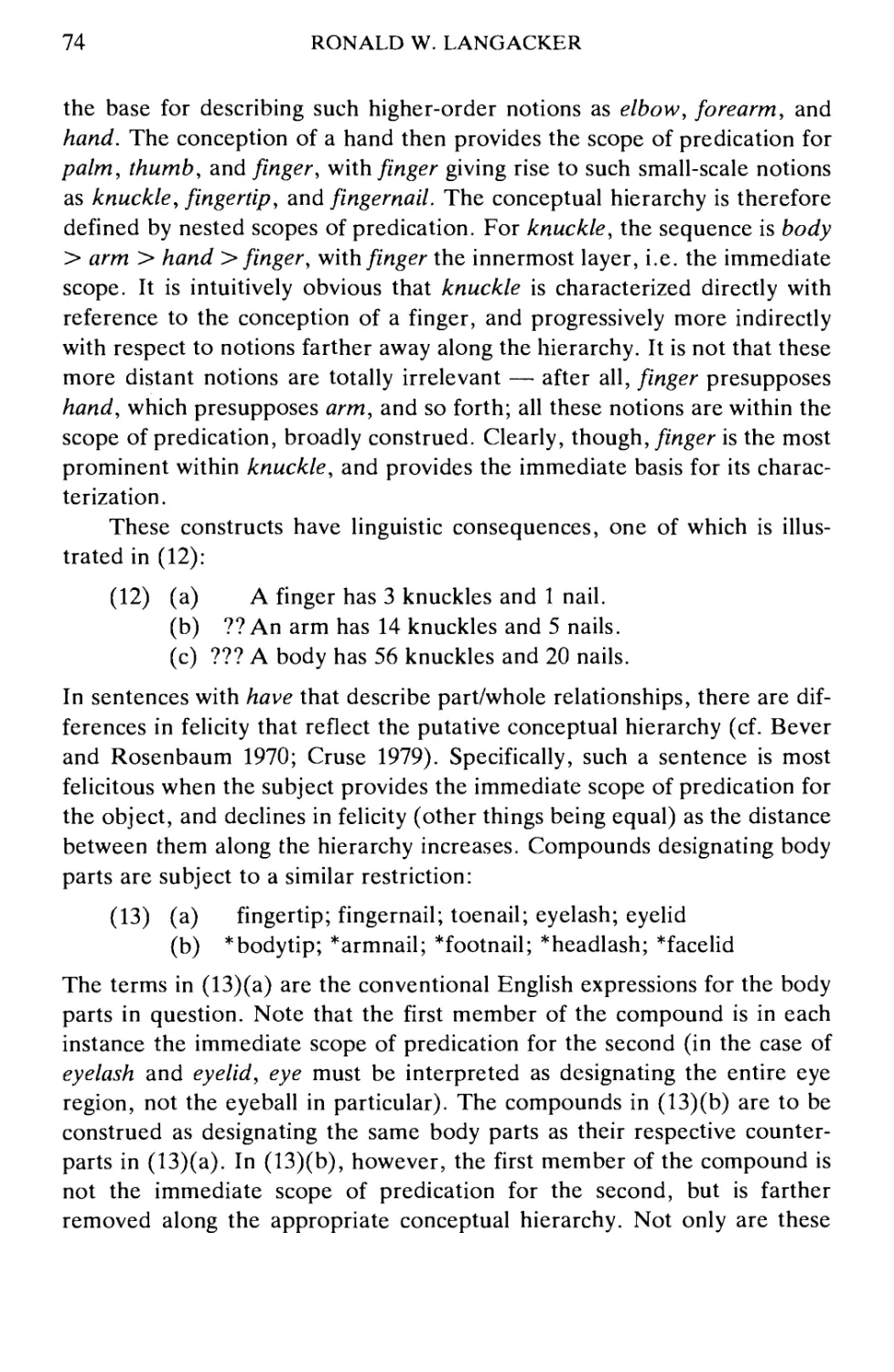

converted into the equivalent '"exploded" format, as illustrated in Fig. 10.

On the left in Fig. 10 is the compositional path of pencil sharpener;

intermediate-level composite structures show that sharpen and sharpener are

constituents (in addition to the individual morphemes and the expression as

a whole). On the right in Fig. 10 is the compositional path of the

constructional schema that pencil sharpener instantiates.

PENCIL-SHARP-EN-ER

pencil sharp-en-er

1

THING-PROCESS-ER1

X Y-er

PENCIL

1 pencil

\ 2

THING]

X

SHARP-EN-ER

sharp-en-er

1SHARP-EN

[sharp-en

^ k

PROCESS

Y ]

SHARP

sharp

enI

-en

Figure 10

These are not phrase trees, but simply ordered assemblies of symbolic

units. They differ from phrase trees in several ways. First, every node is a

symbolic structure incorporating both semantic and phonological content

28

RONALD W. LANGACKER

(and nothing else). Second, these structures are not linearly ordered: each

node specifies temporal ordering internally at the phonological pole, but

the nodes are not temporally ordered with respect to one another. A third

difference is the absence of node labels specifying the grammatical class of

constituents. Class membership is specified not by labels or features, but

rather by categorizing relationships, each reflecting the assessment that a

structure instantiates a particular schema. In the case of grammatical

structure, the categorizing schemas are symbolic, with actual semantic and

phonological content (though often this content is abstract, even to the

point of being essentially vacuous). Collectively, these categorizing

judgments constitute the expression's structural description.

Distribution and Predictability

Cognitive grammar posits only symbolic units for the description of

grammatical structure. Having examined the general character of such

analysis, we turn now to specific phenomena that are often taken as

demonstrating the autonomy of grammar.

One class of arguments pertains to the impossibility of predicting the

membership of "distributional classes", i.e. classes defined on the basis of

morphological or syntactic behavior. For example, there is no way to

predict, on either semantic or phonological grounds, precisely which English

verbs form their past tense by ablauting / to a (i.e. [1] to [ae]); this pattern is

possible only with a small set of verb stems (sit, swim, begin, ring, sing,

etc.) that are neither coherent semantically nor unique phonologically. Nor

is it possible, apparently, to predict the exact membership of the class of

verbs occurring in the so-called "dative shift" construction. While the

construction favors verbs of transfer that are monosyllabic (e.g. give, send,

mail, ship, and buy, but not transfer, communicate, purchase, or propose),

certain pairs of verbs that appear quite comparable both semantically and

phonologically exhibit contrasting behavior:

(12) (a) I told the same thing to Bill,

(a') I told Bill the same thing,

(b) I said the same thing to Bill.

(b') * I said Bill the same thing.

(13) (a) I peeled a banana for Bill,

(a') I peeled Bill a banana.

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

29

(b) I cored an apple for Bill,

(b') *I cored Bill an apple.

Much more can be said about this issue, but let us assume the worst,

namely that the class of dative-shift verbs is unpredictable and must

somehow be listed in the grammar.

In providing such information, linguists generally resort to some type

of diacritic or grammatical feature. For example, sit might be marked by a

diacritic indicating its membership in the class of verbs (e.g. "Class 2B")

that ablaut / to a to mark the past tense. Or, in addition to semantic and

phonological features, give might be attributed a syntactic rule feature such

as [4- Dative Shift], which specifies its ability to undergo the dative shift

rule. Whatever device is used, the marking is assumed to have neither

semantic nor phonological content, since the class it identifies is not

uniquely predictable on the basis of either form or meaning. The autonomy

of grammar is commonly assumed to follow as an inescapable consequence:

since grammatical behavior forces one to posit a distinct set of specifically

"grammatical" classes and descriptive constructs, grammar must constitute

an independent domain of linguistic organization.

This argument is fallacious, for it confuses two issues that can in

principle be distinguished: (i) what kinds of structures there are; and (ii) the

predictability of their behavior. I call this the "type/predictability fallacy". It is

not logically incoherent to maintain that only symbolic units are required

for the description of grammatical structure, even though one cannot

always predict, in absolute terms, precisely which symbolic units occur in a

given construction. Some type of marking or listing is required to provide

this information, but there is no a priori reason to believe that a contentless

feature or diacritic is the proper device for this purpose. Indeed, little

cognitive plausibility attaches to the claim that speakers possess any direct

analog of empty markers like [Class 2B] or [4- Dative Shift] in their mental

representation of linguistic structure.

It is possible to furnish the requisite distributional information without

resorting to anything other than symbolic units. To say that a particular

verb, e.g. sit, marks its past tense by ablauting / to a is equivalent to saying

that sat is a conventional unit of English. Similarly, to say that a particular

verb, e.g. give, occurs in the dative shift construction is equivalent to saying

that the schema describing this construction is instantiated by subschema

having give as its verbal element. I have argued elsewhere (Langacker

1982a, in press) for a "usage-based" model of linguistic structure, wherein

30

RONALD W. LANGACKER

both schemas and their instantiations are included in the grammar of a

language, provided that they have the status of conventional units. Schemas

capture generalizations by representing patterns observable across

expressions. Unit instantiations of constructional schemas (both specific

expressions and subschemas at varying levels of abstraction) describe the actual

implementation of these generalizations by specifying their conventional

range of application.

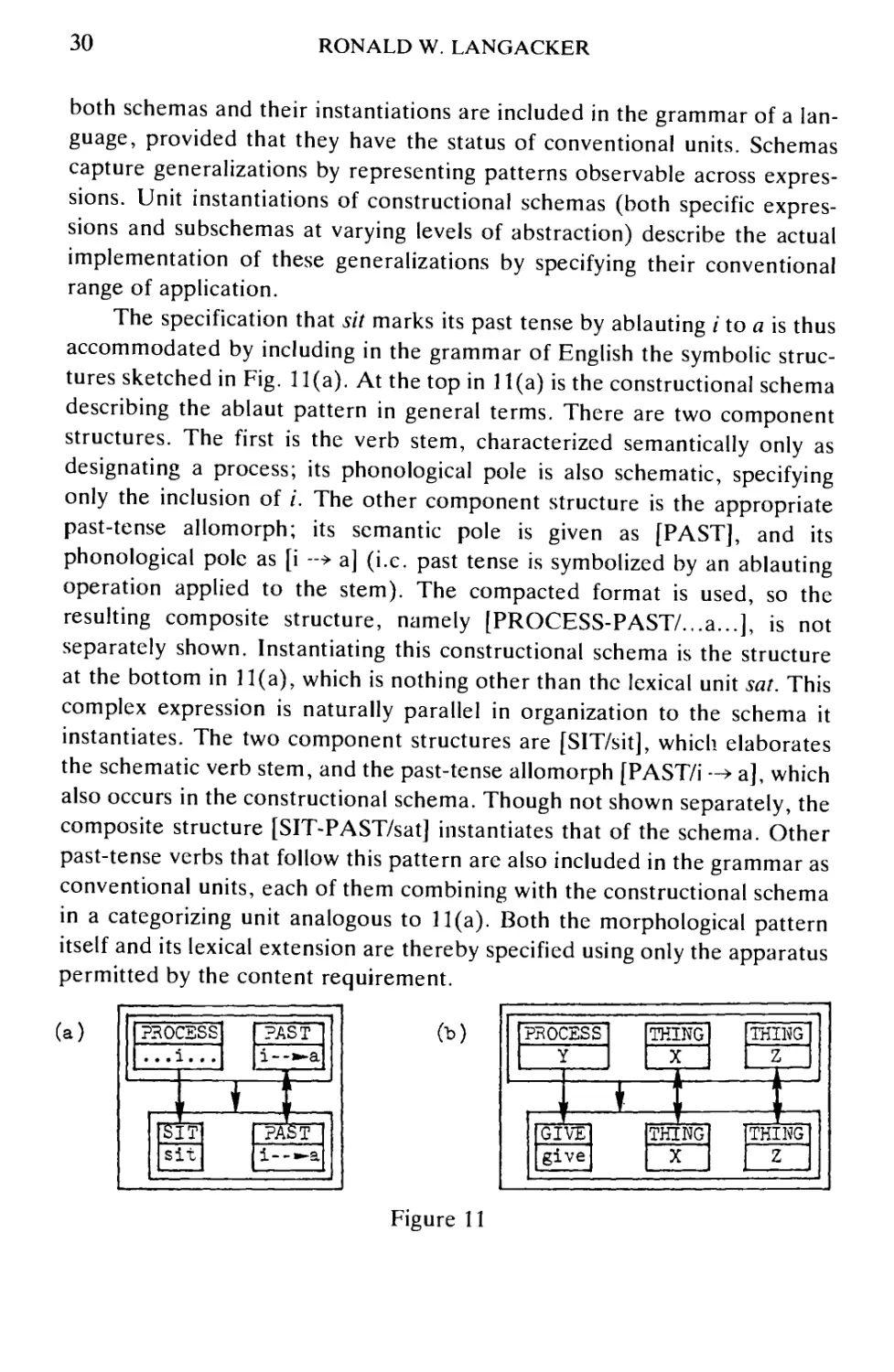

The specification that sit marks its past tense by ablauting / to a is thus

accommodated by including in the grammar of English the symbolic

structures sketched in Fig. 11(a). At the top in 11(a) is the constructional schema

describing the ablaut pattern in general terms. There are two component

structures. The first is the verb stem, characterized semantically only as

designating a process; its phonological pole is also schematic, specifying

only the inclusion of /. The other component structure is the appropriate

past-tense allomorph; its semantic pole is given as [PAST], and its

phonological pole as [i —> a] (i.e. past tense is symbolized by an ablauting

operation applied to the stem). The compacted format is used, so the

resulting composite structure, namely [PROCESS-PAST/...a...], is not

separately shown. Instantiating this constructional schema is the structure

at the bottom in 11(a), which is nothing other than the lexical unit sat. This

complex expression is naturally parallel in organization to the schema it

instantiates. The two component structures are [SIT/sit], which elaborates

the schematic verb stem, and the past-tense allomorph [PAST/i --> a], which

also occurs in the constructional schema. Though not shown separately, the

composite structure [SIT-PAST/sat] instantiates that of the schema. Other

past-tense verbs that follow this pattern are also included in the grammar as

conventional units, each of them combining with the constructional schema

in a categorizing unit analogous to 11(a). Both the morphological pattern

itself and its lexical extension are thereby specified using only the apparatus

permitted by the content requirement.

:| (process

1 Y

1

THING

X

' ♦ ;

[GIVE

[give

- ■■ |

"THING 1 j I

z l||

I' ■ j

THING

X

L- -J

J. .-.

THING111

Z |

Figure 11

l| PROCESS

...i...

1

PAST it

i--»*a|| 1

* ;

1 x" r

[SIT

sit

f

PAST |||

1—a||

AN OVERVIEW OF COGNITIVE GRAMMAR

31

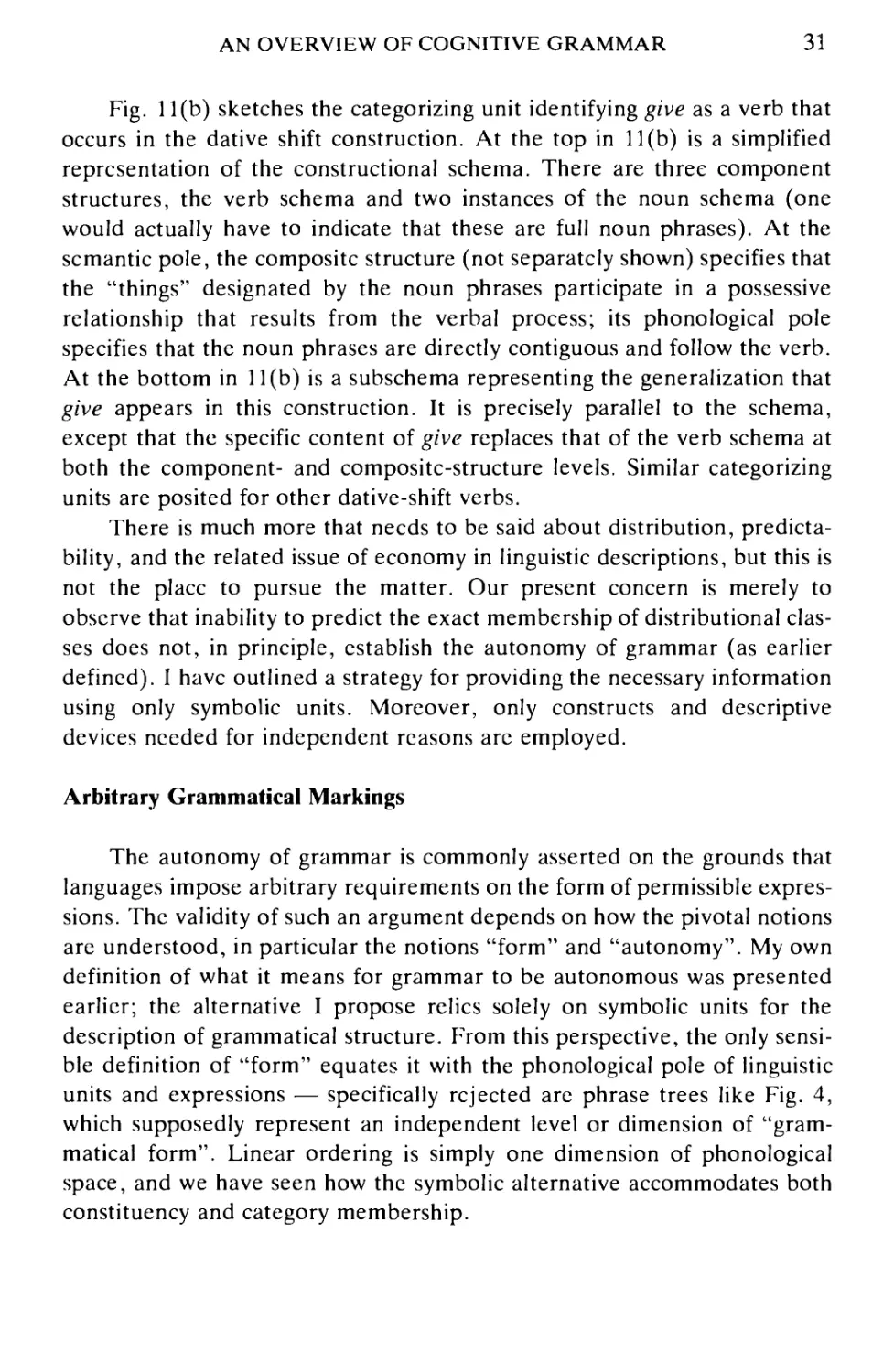

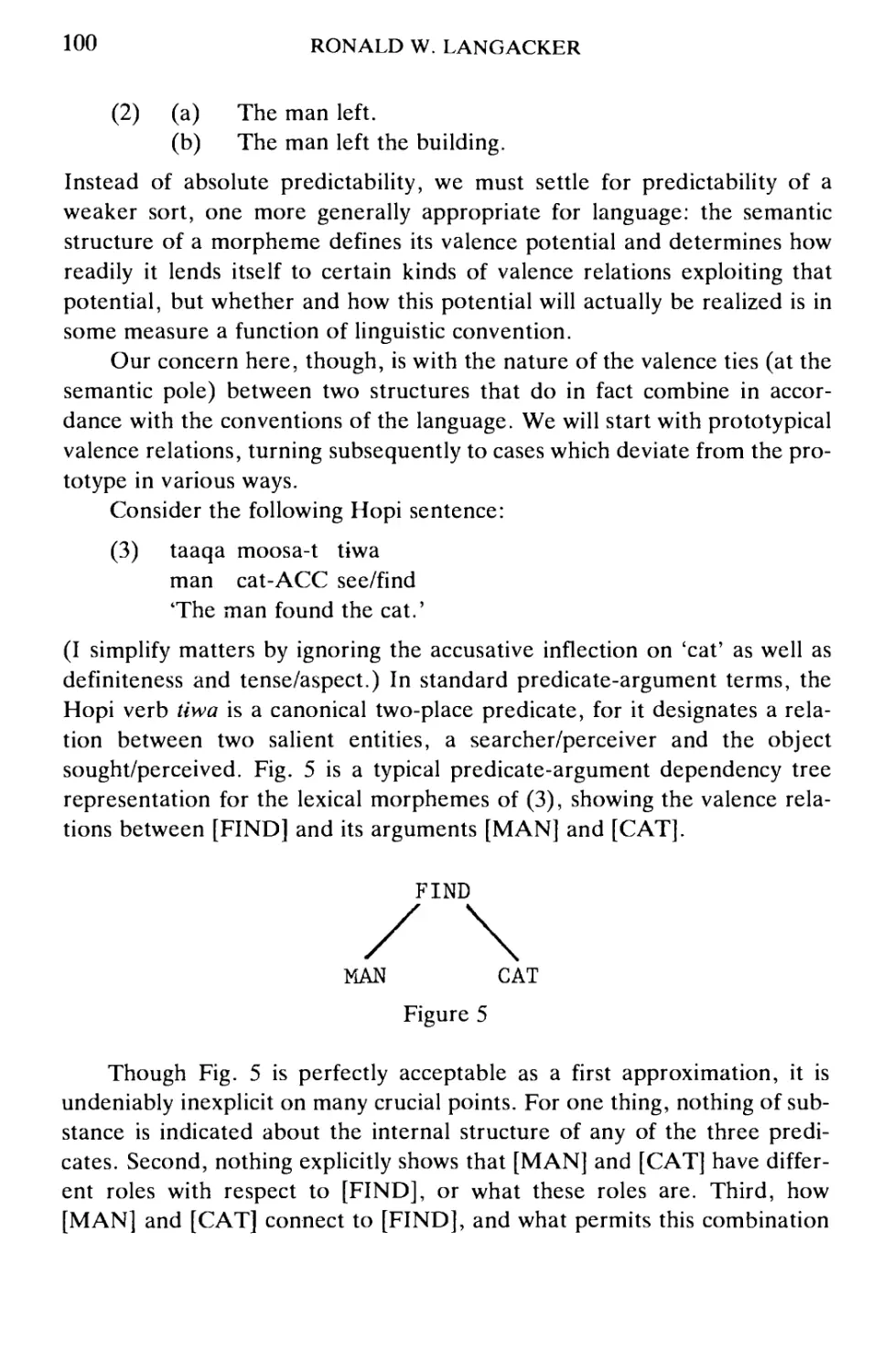

Fig. 11(b) sketches the categorizing unit identifying give as a verb that

occurs in the dative shift construction. At the top in 11(b) is a simplified

representation of the constructional schema. There are three component

structures, the verb schema and two instances of the noun schema (one

would actually have to indicate that these are full noun phrases). At the

semantic pole, the composite structure (not separately shown) specifies that

the "things" designated by the noun phrases participate in a possessive

relationship that results from the verbal process; its phonological pole

specifies that the noun phrases are directly contiguous and follow the verb.

At the bottom in 11(b) is a subschema representing the generalization that

give appears in this construction. It is precisely parallel to the schema,

except that the specific content of give replaces that of the verb schema at

both the component- and composite-structure levels. Similar categorizing

units are posited for other dative-shift verbs.

There is much more that needs to be said about distribution,

predictability, and the related issue of economy in linguistic descriptions, but this is

not the place to pursue the matter. Our present concern is merely to

observe that inability to predict the exact membership of distributional

classes does not, in principle, establish the autonomy of grammar (as earlier

defined). I have outlined a strategy for providing the necessary information

using only symbolic units. Moreover, only constructs and descriptive

devices needed for independent reasons arc employed.

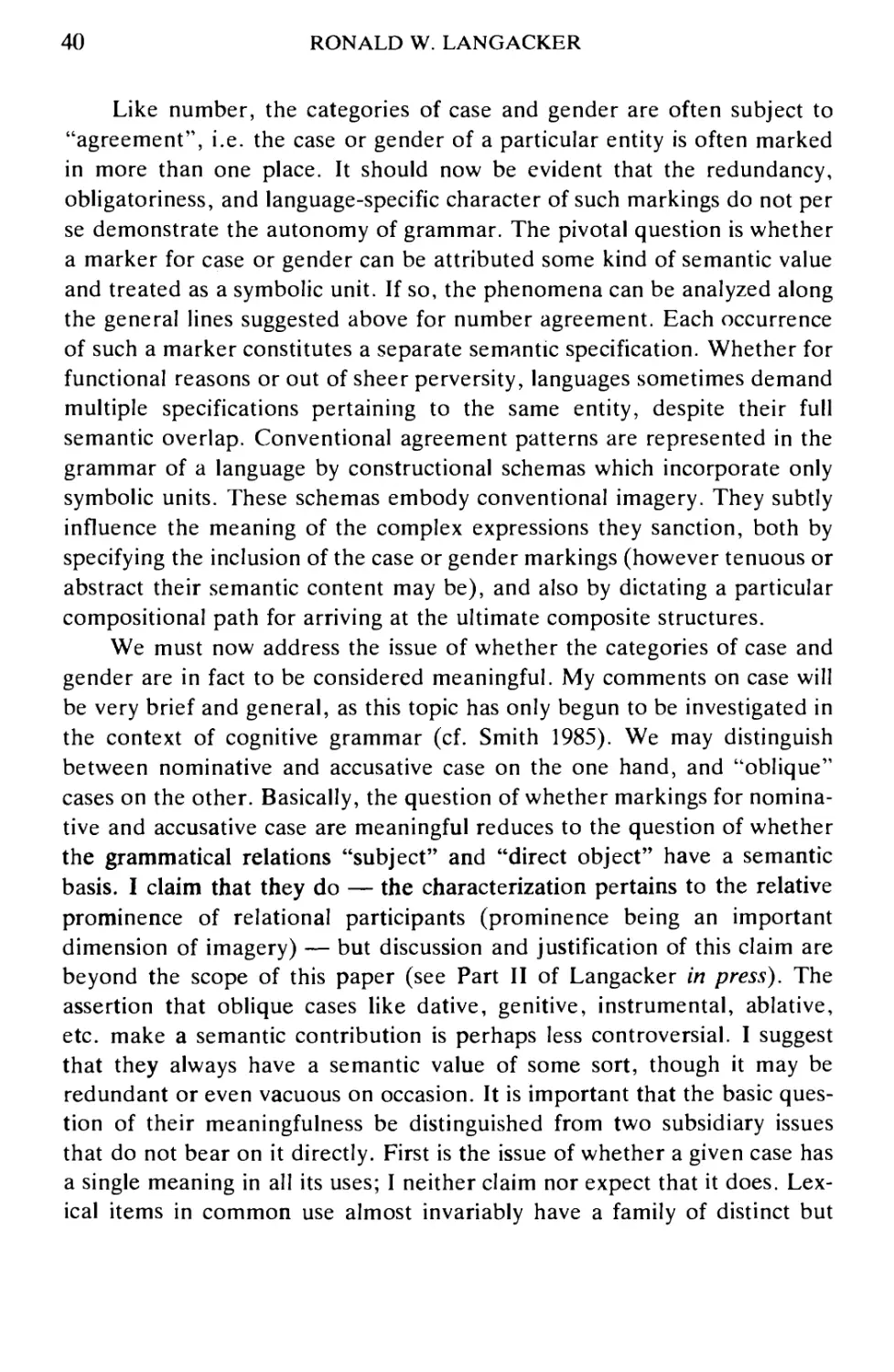

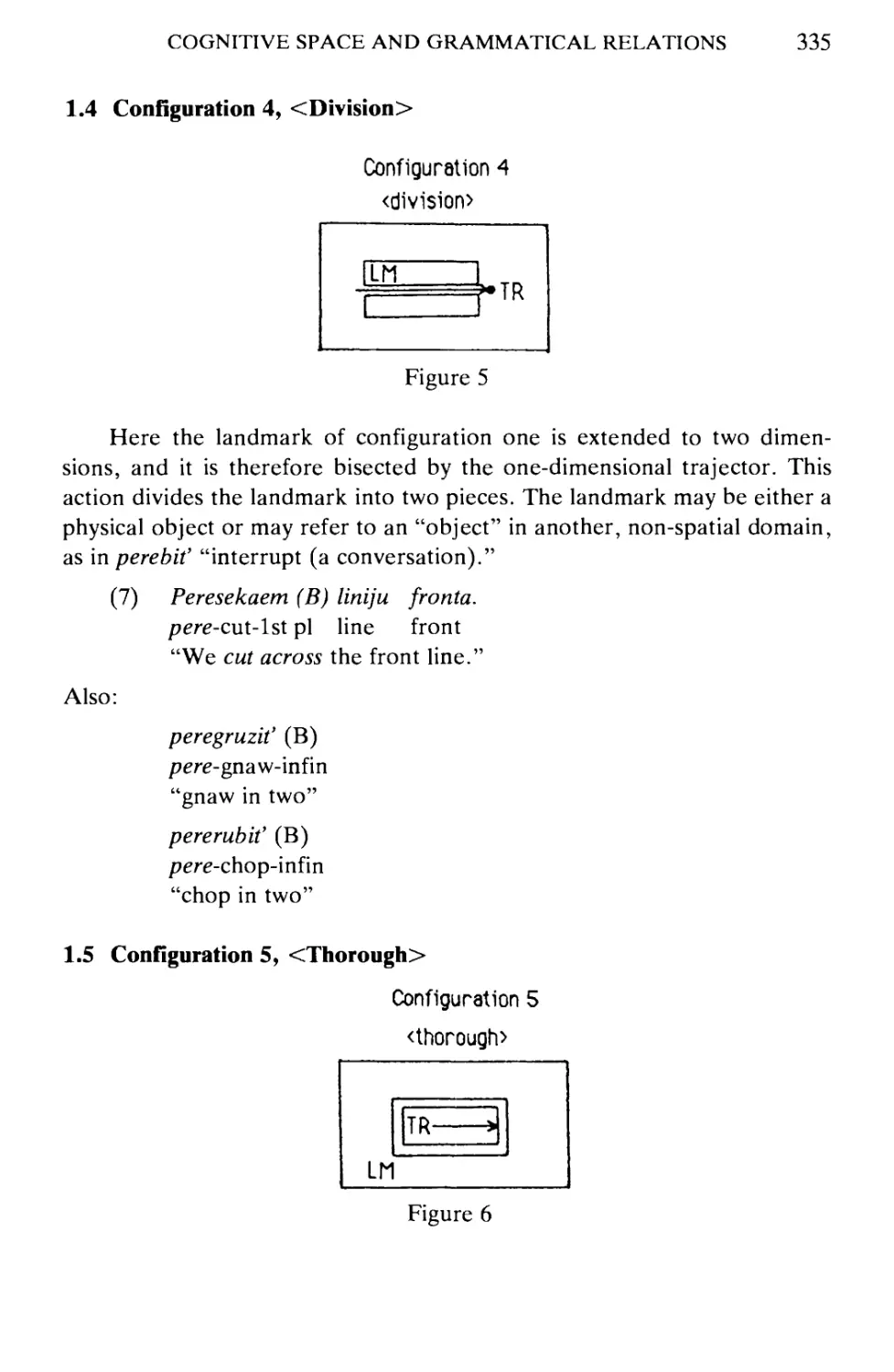

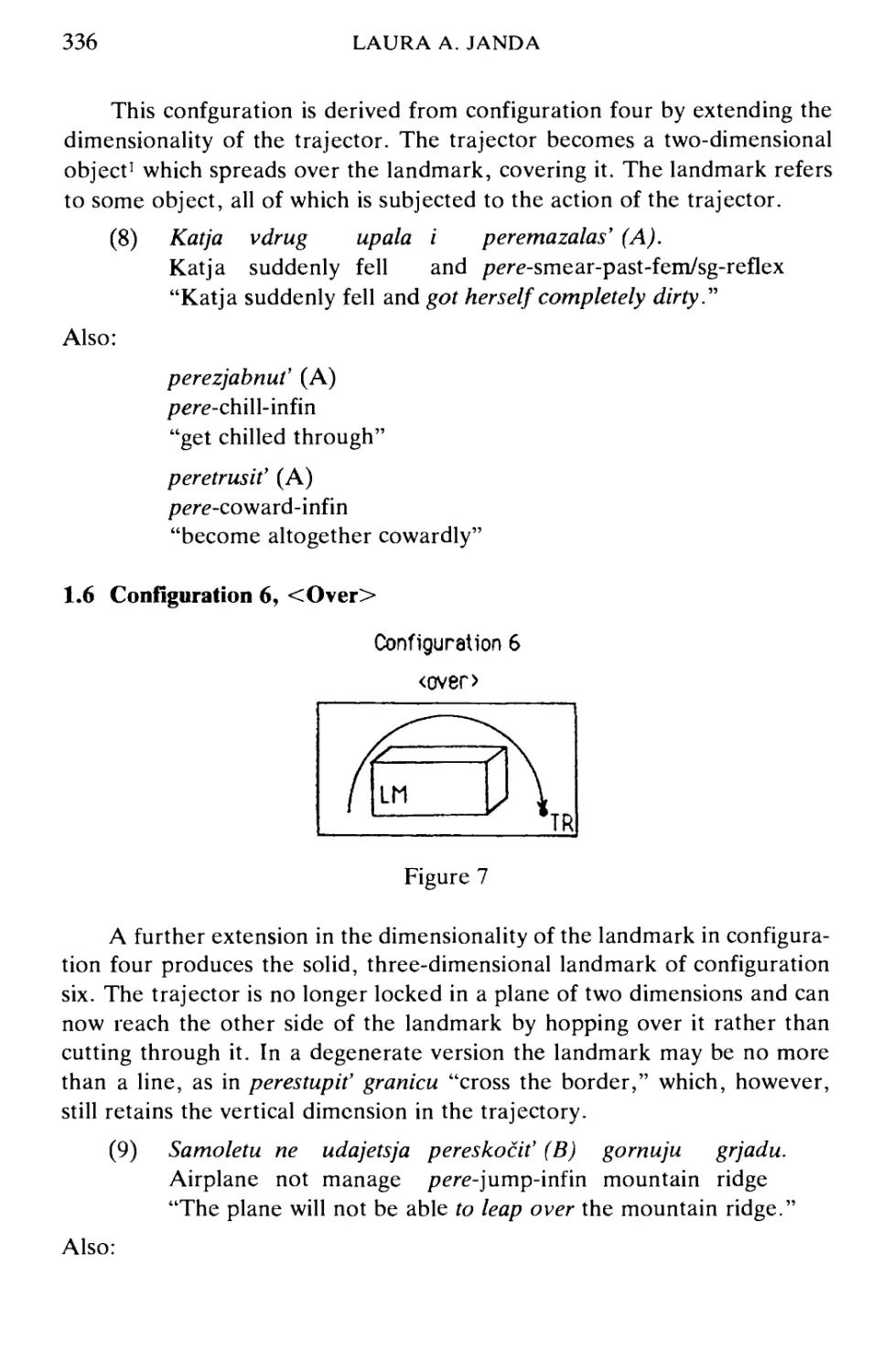

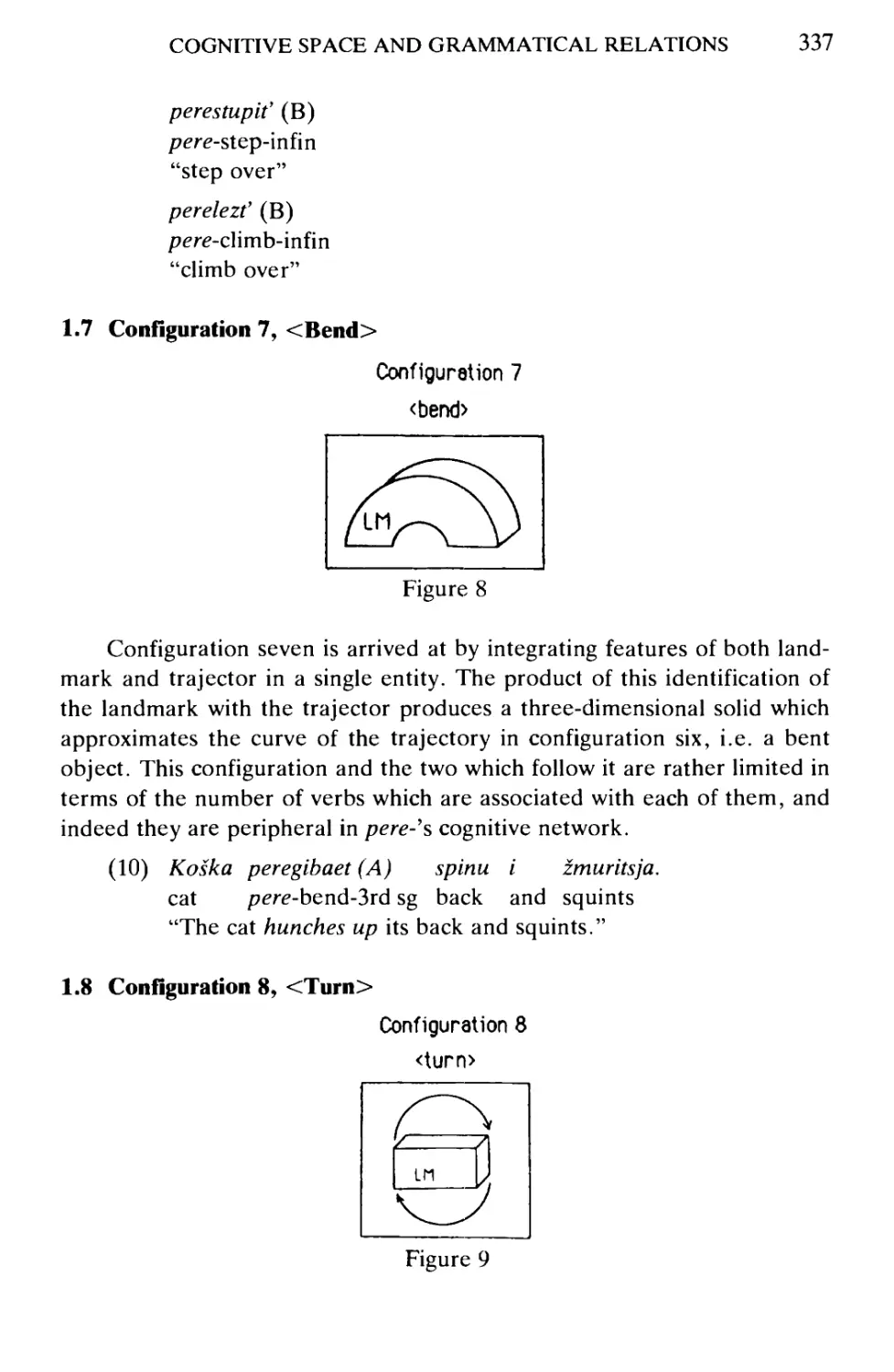

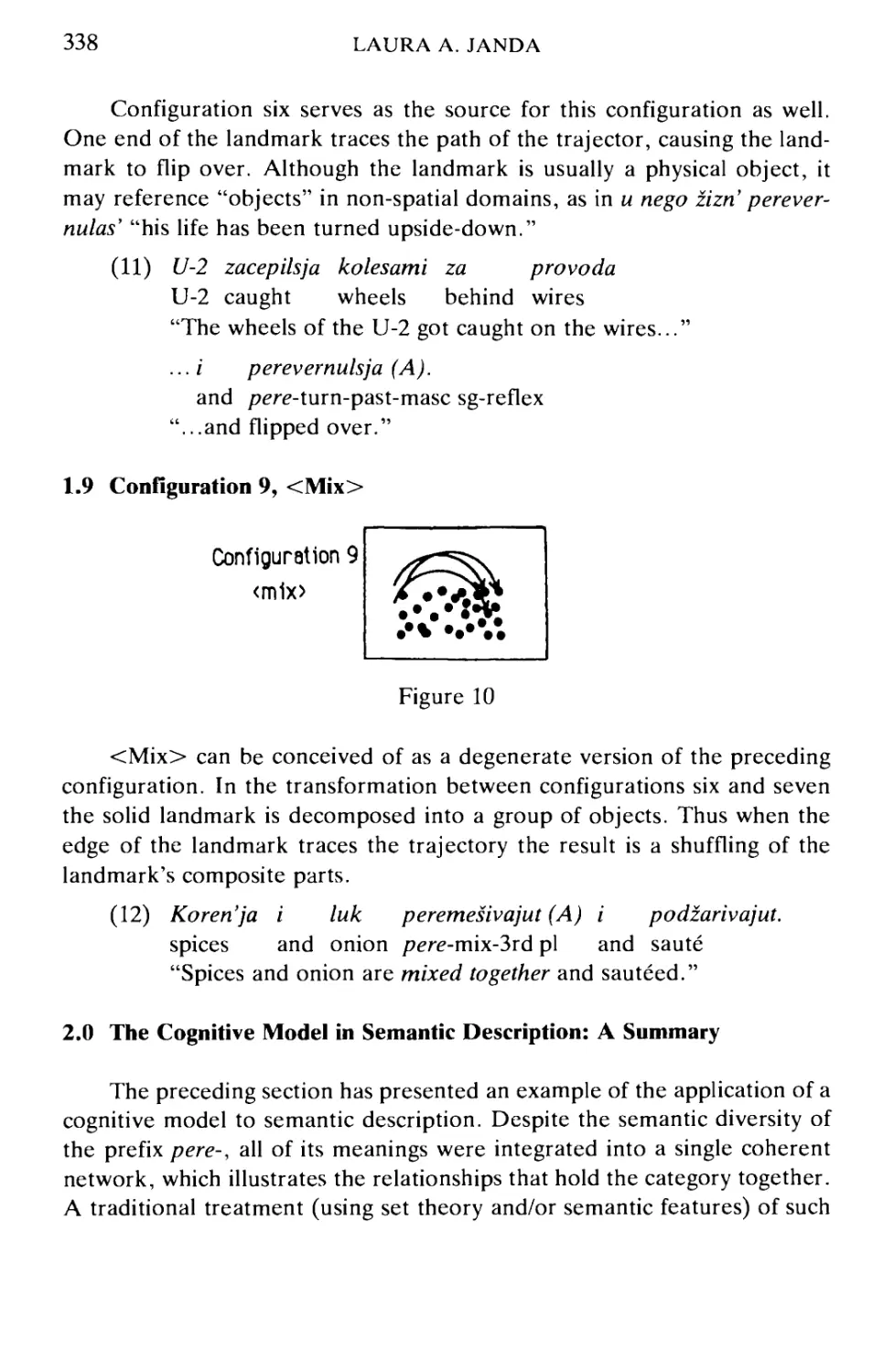

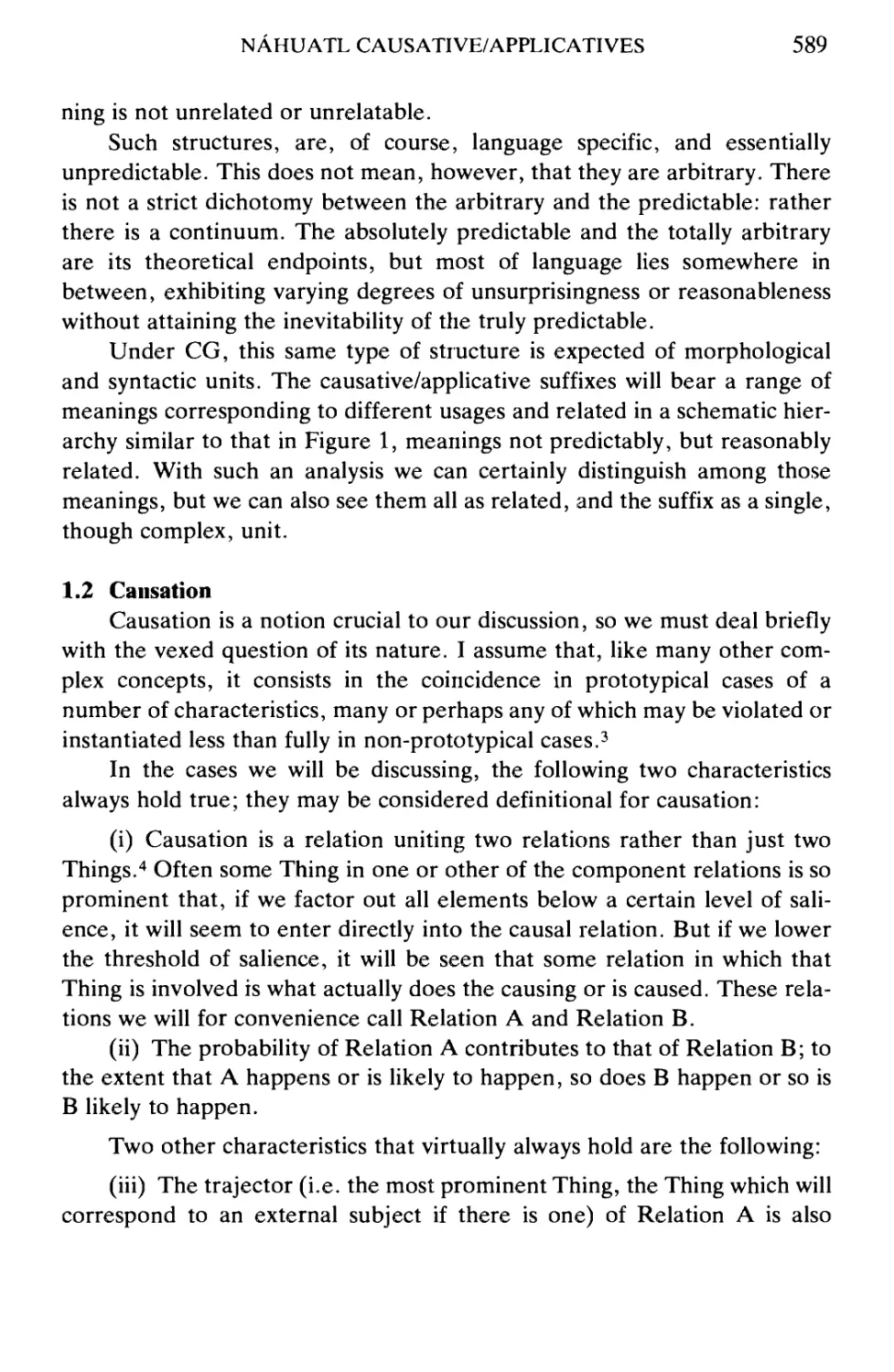

Arbitrary Grammatical Markings

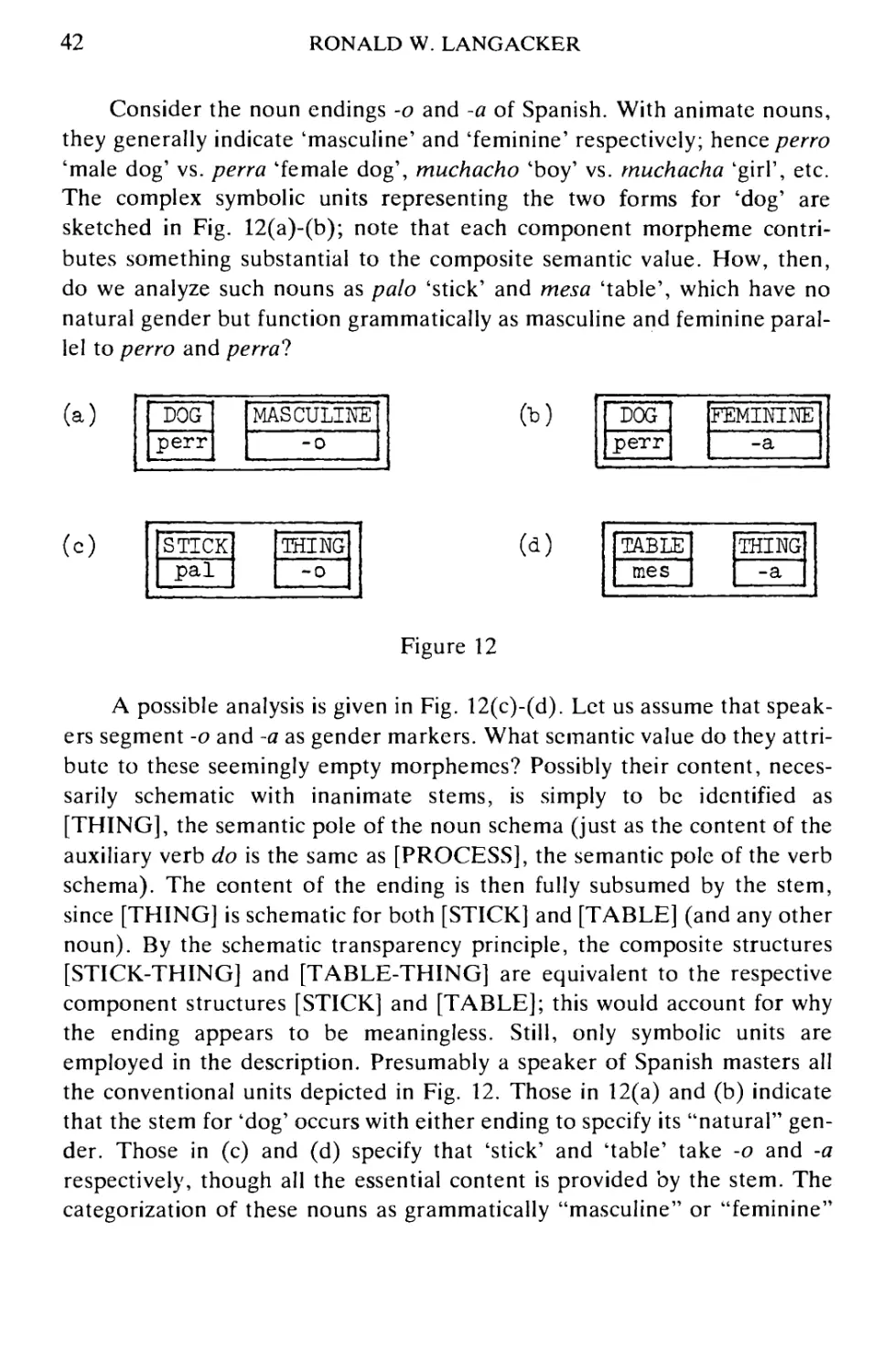

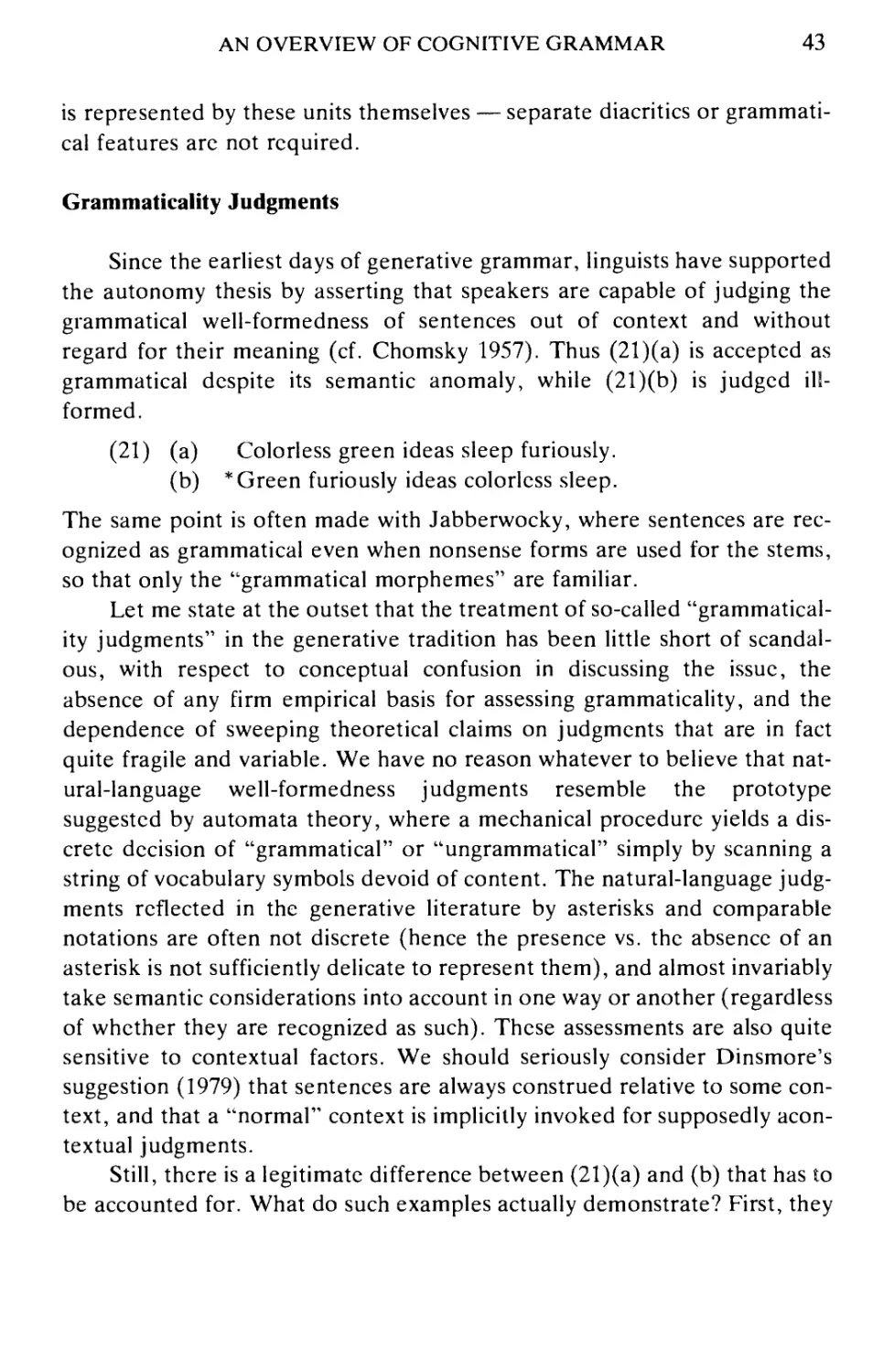

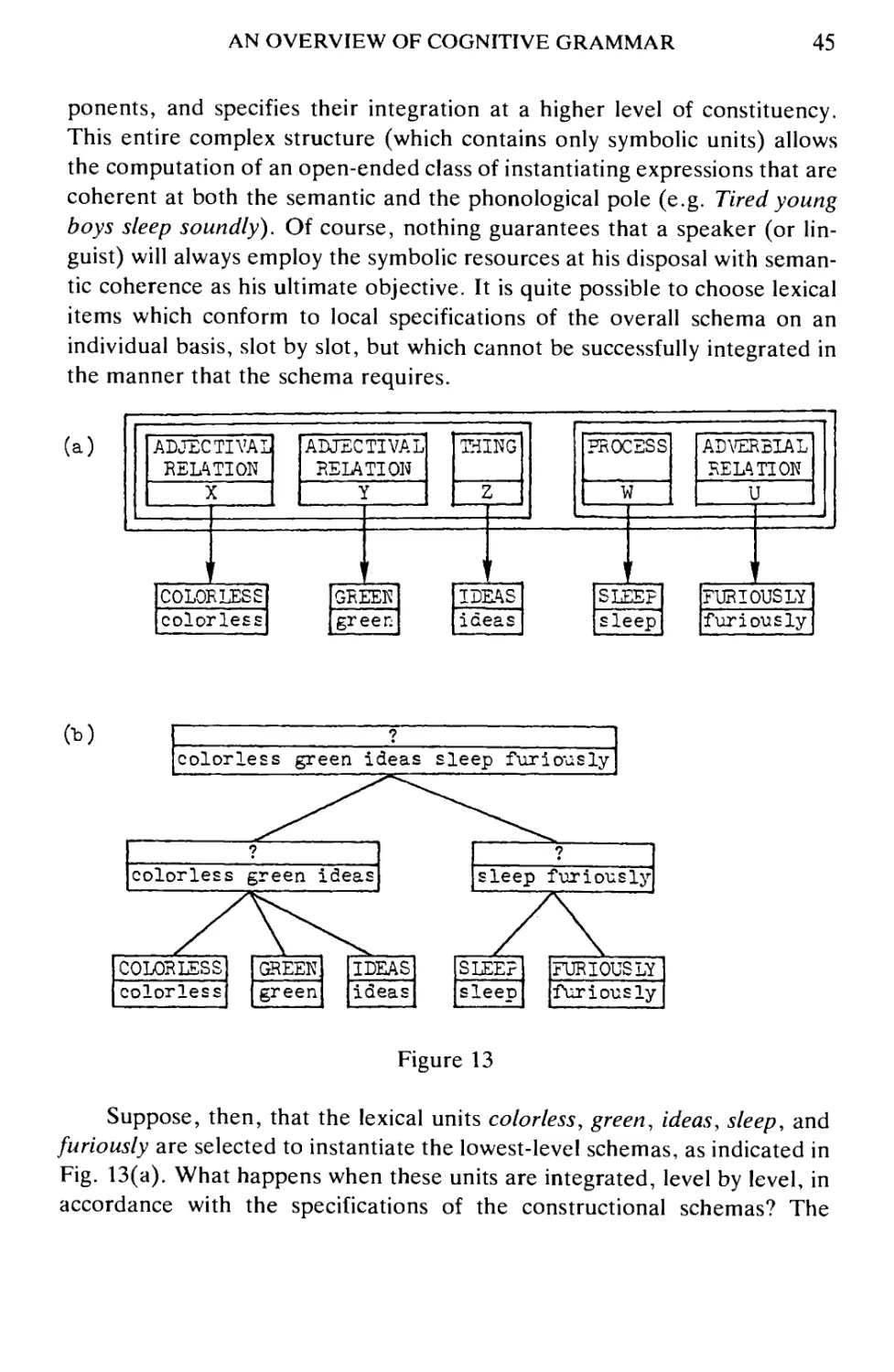

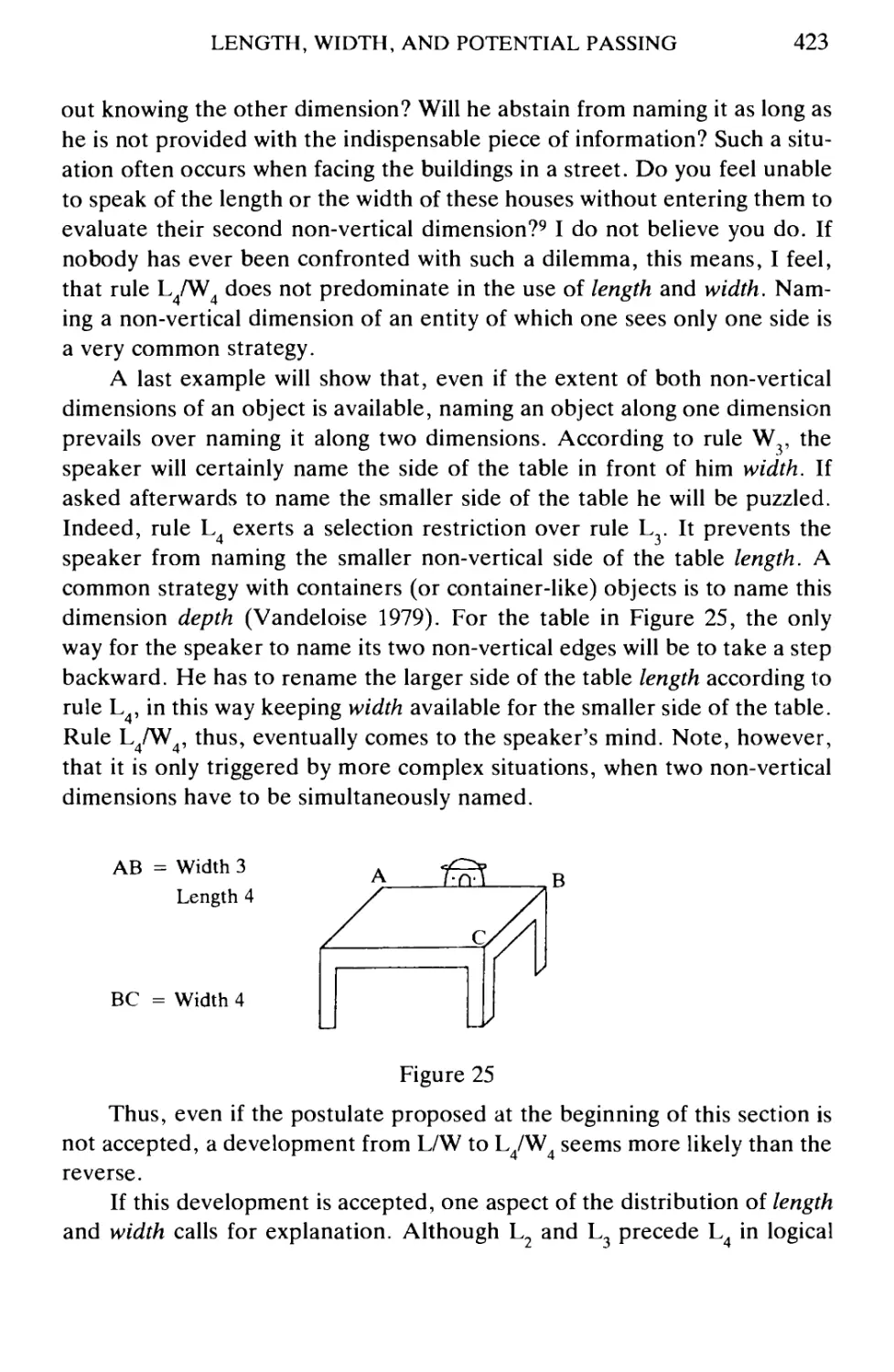

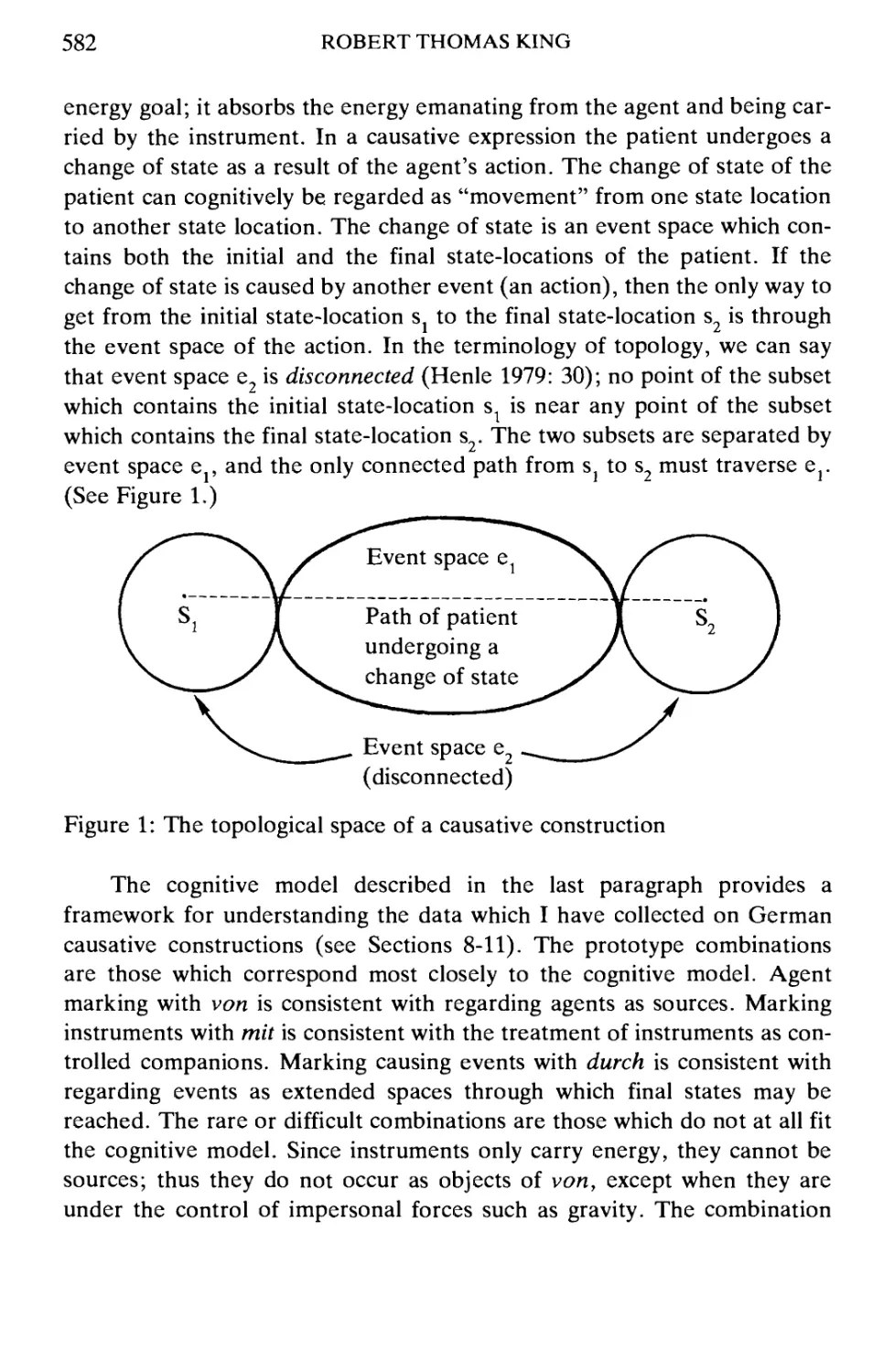

The autonomy of grammar is commonly asserted on the grounds that

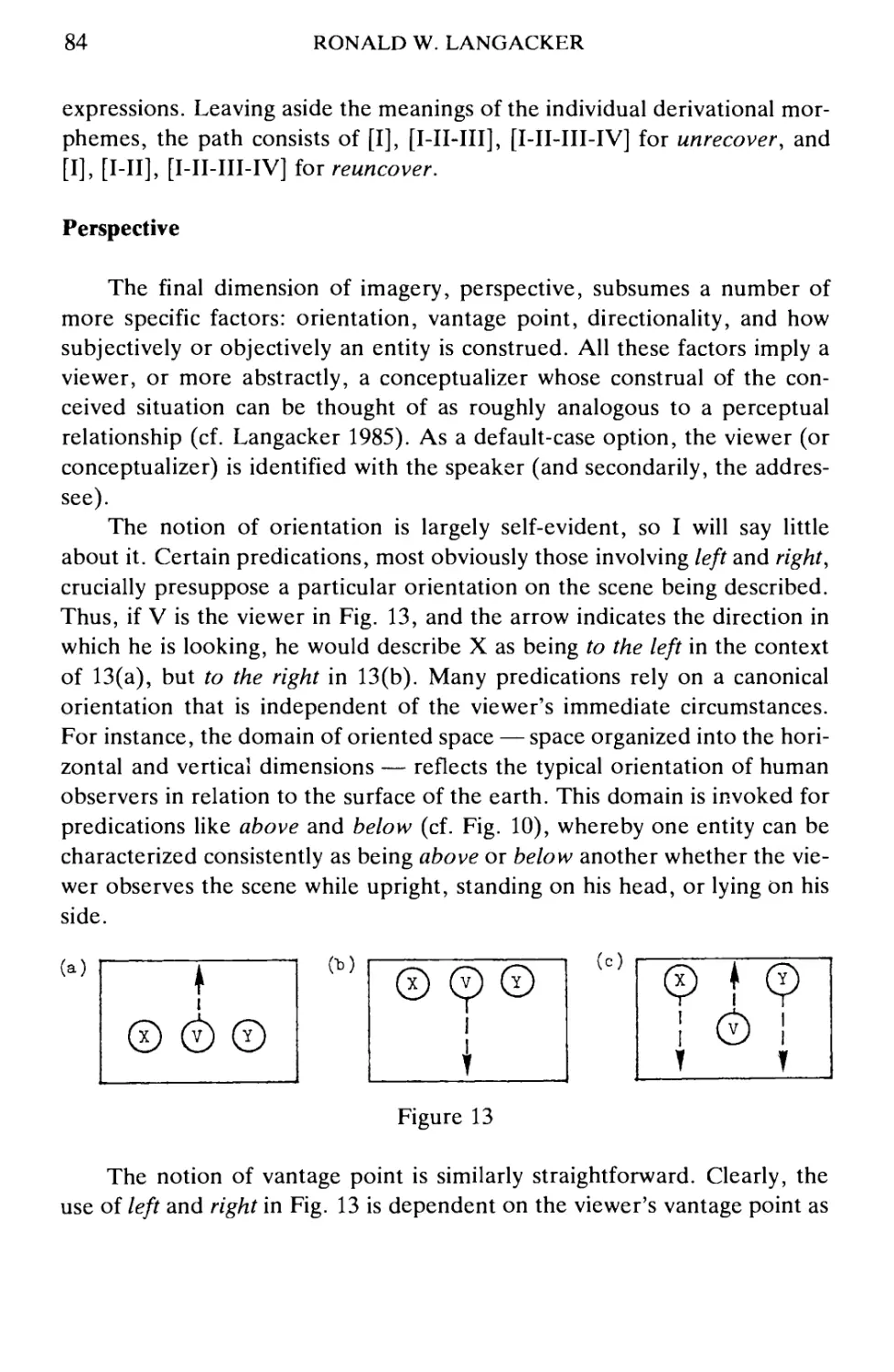

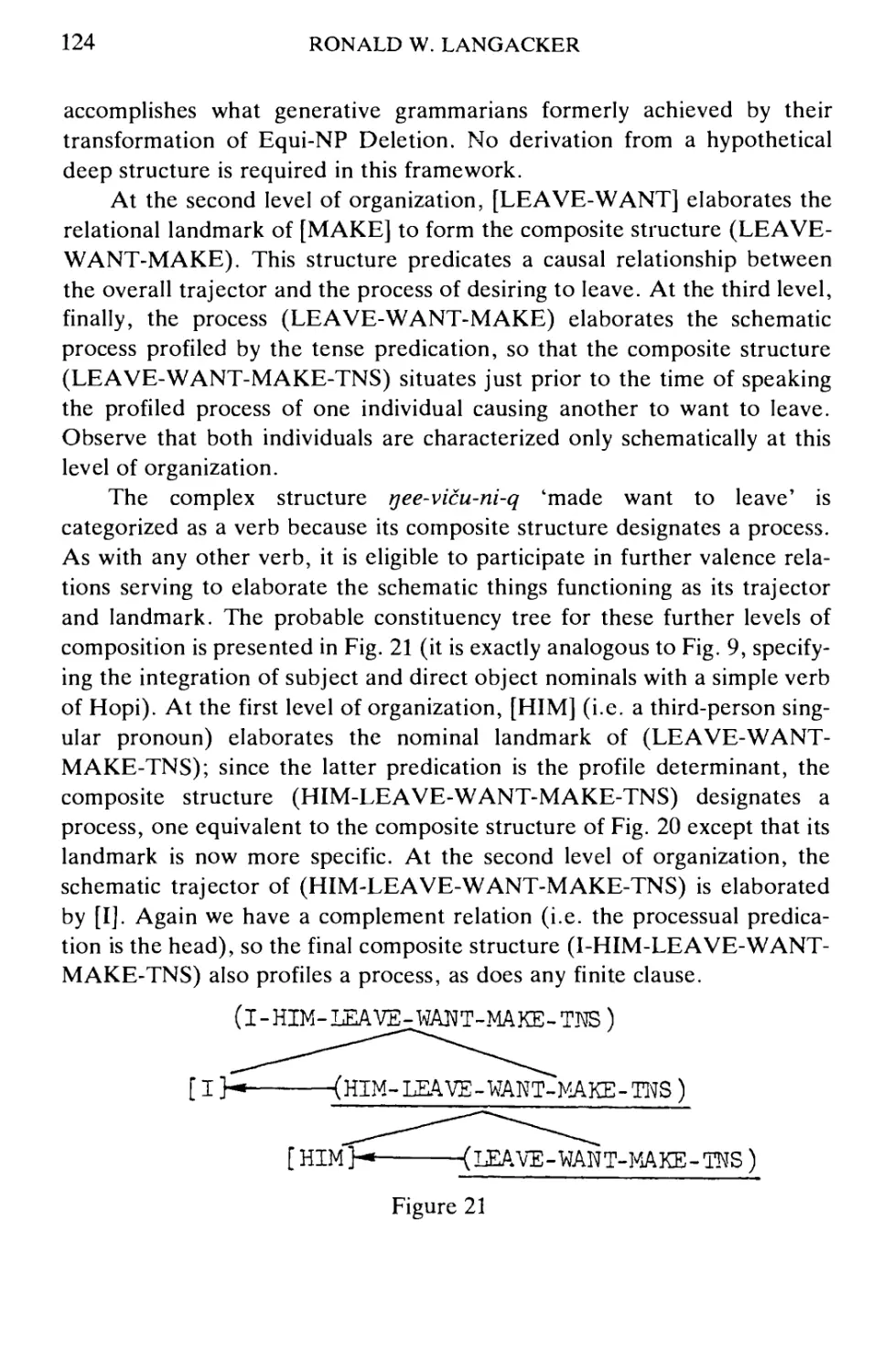

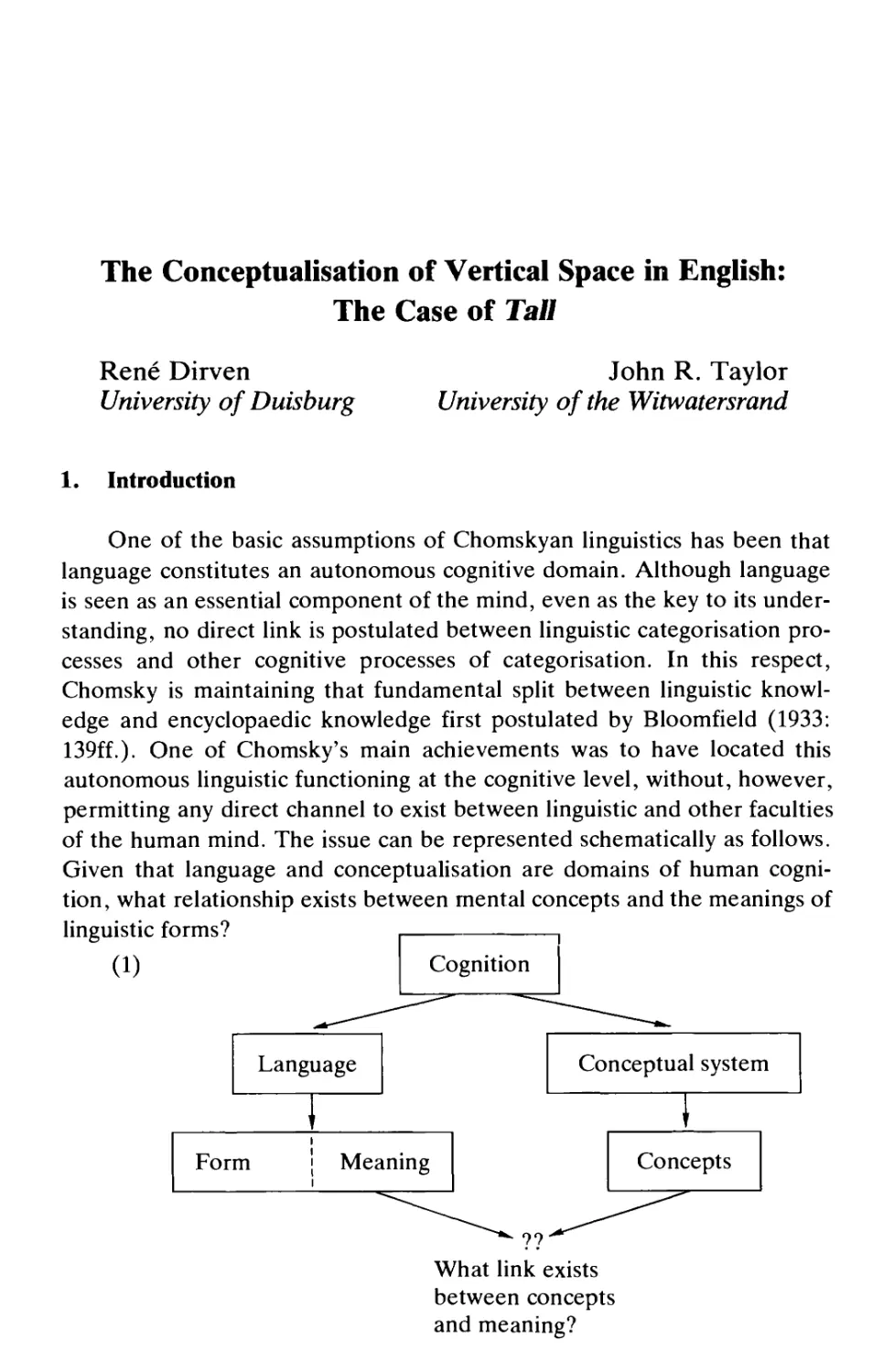

languages impose arbitrary requirements on the form of permissible

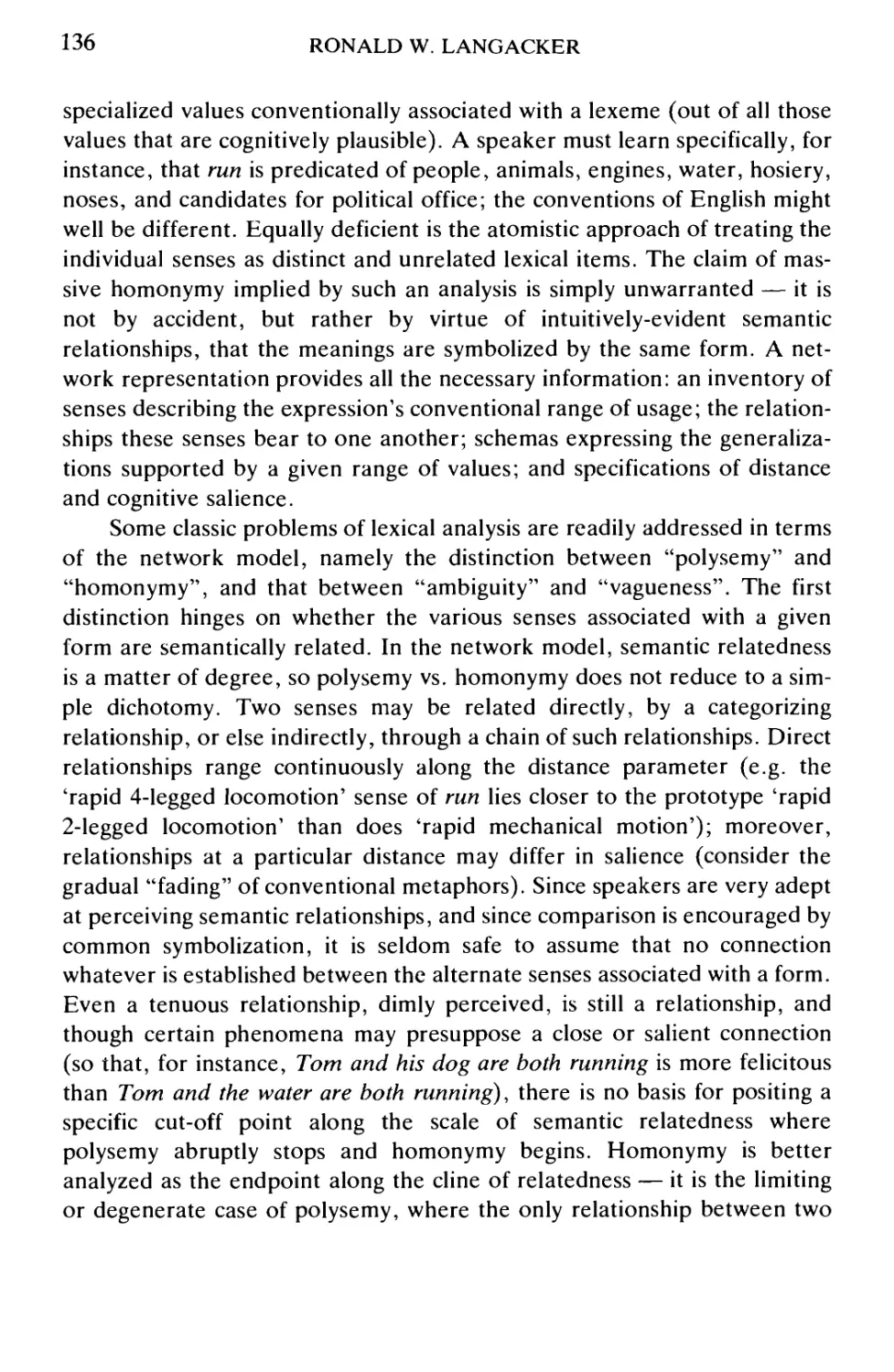

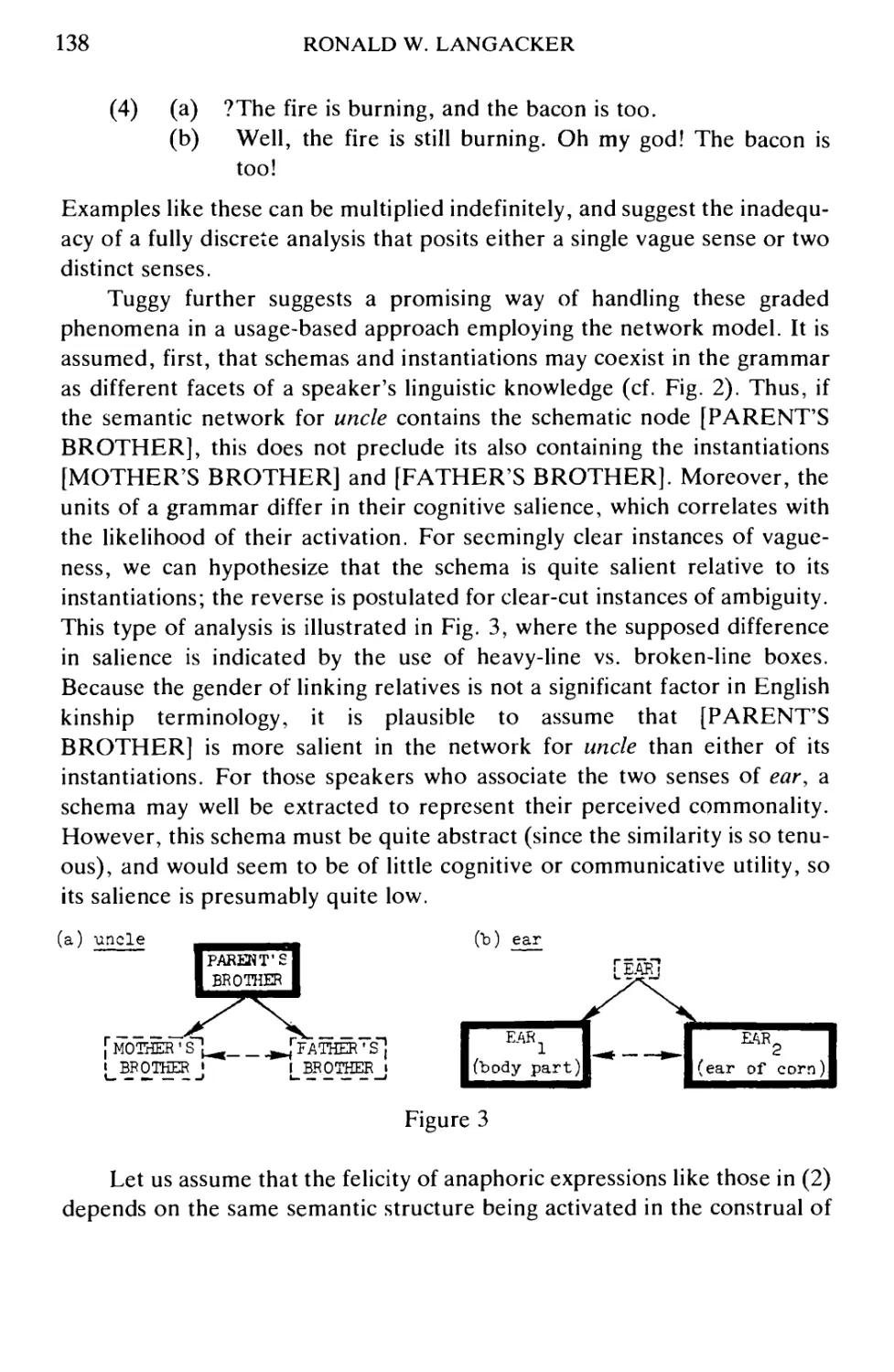

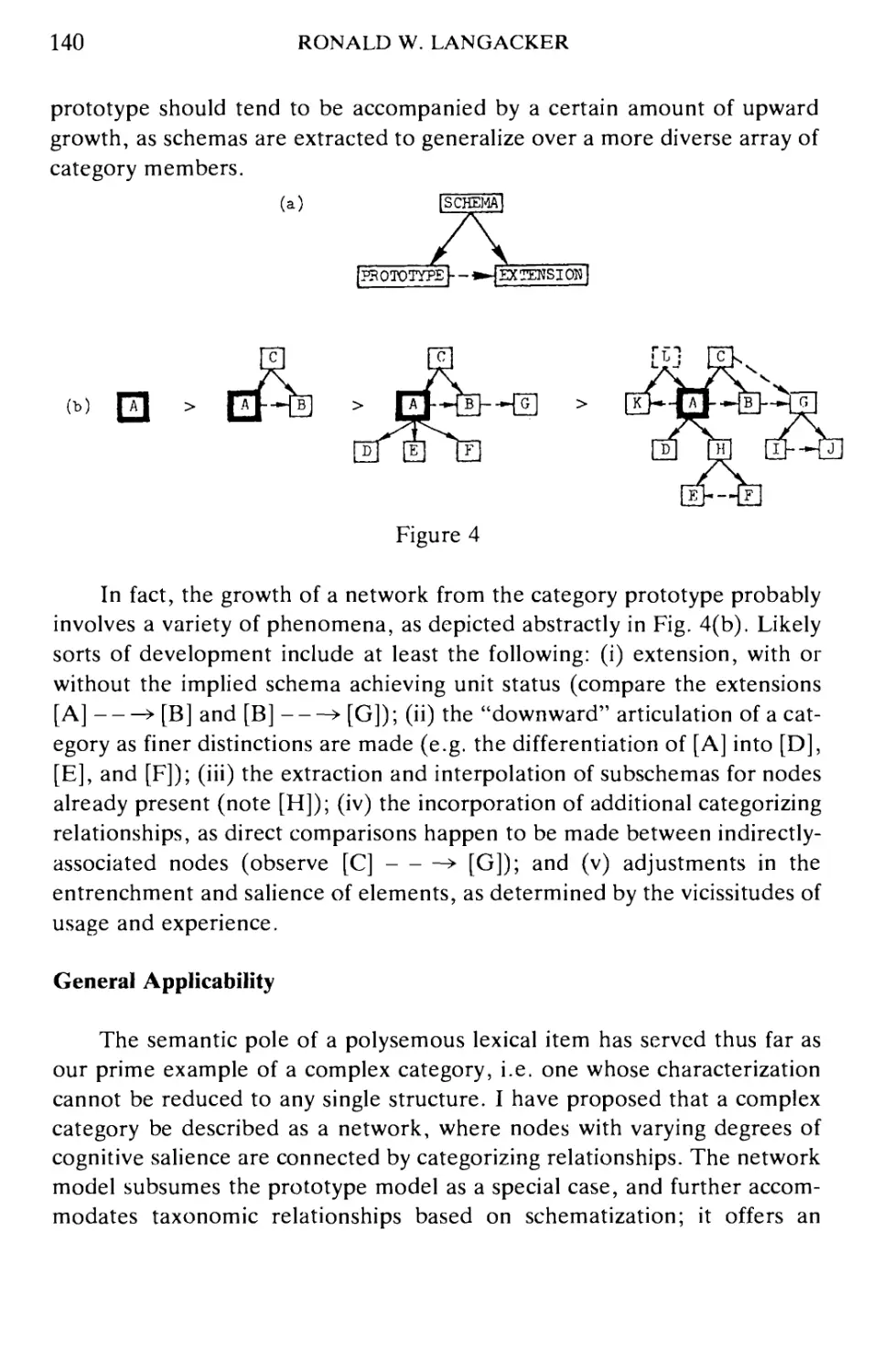

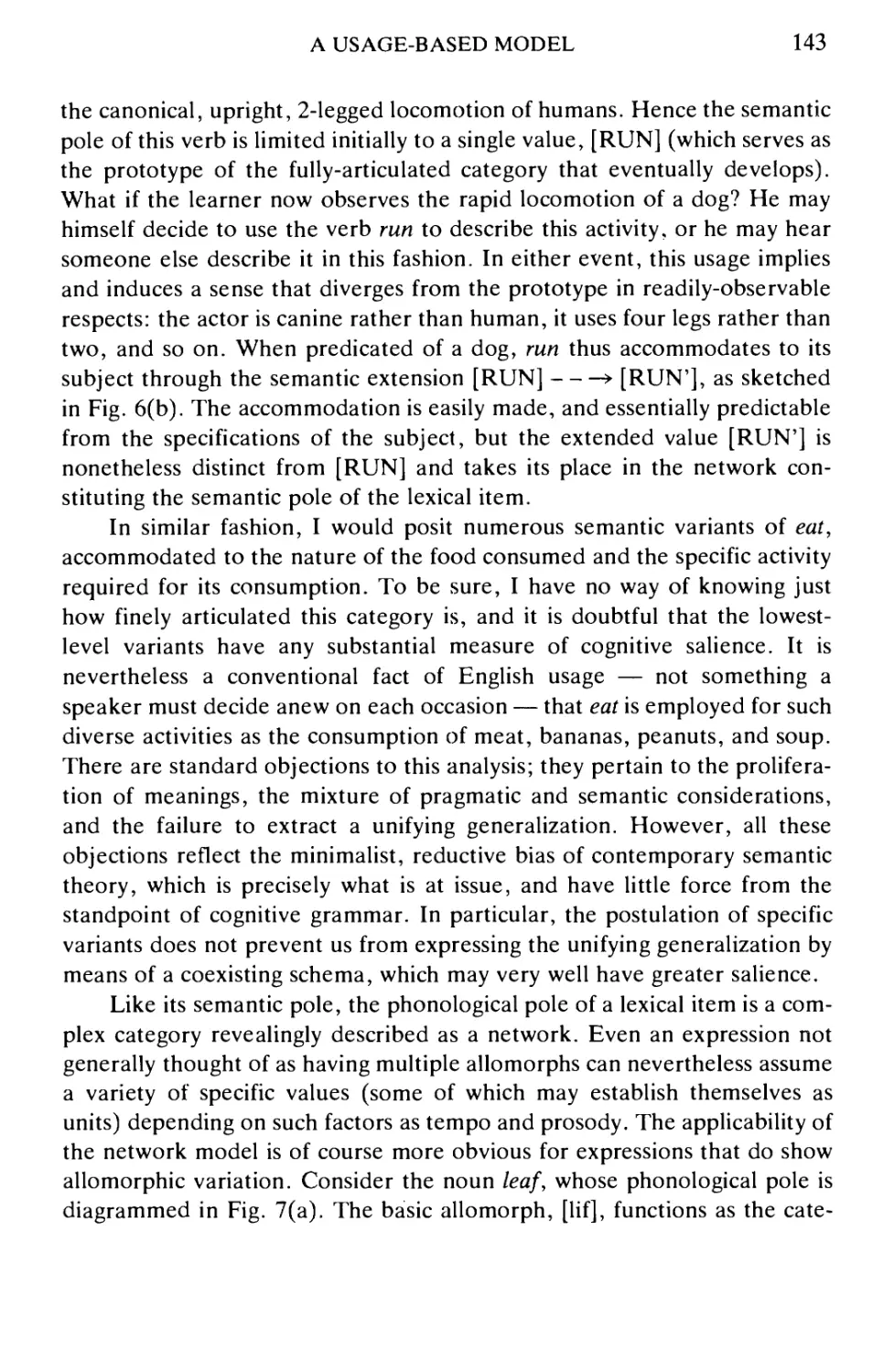

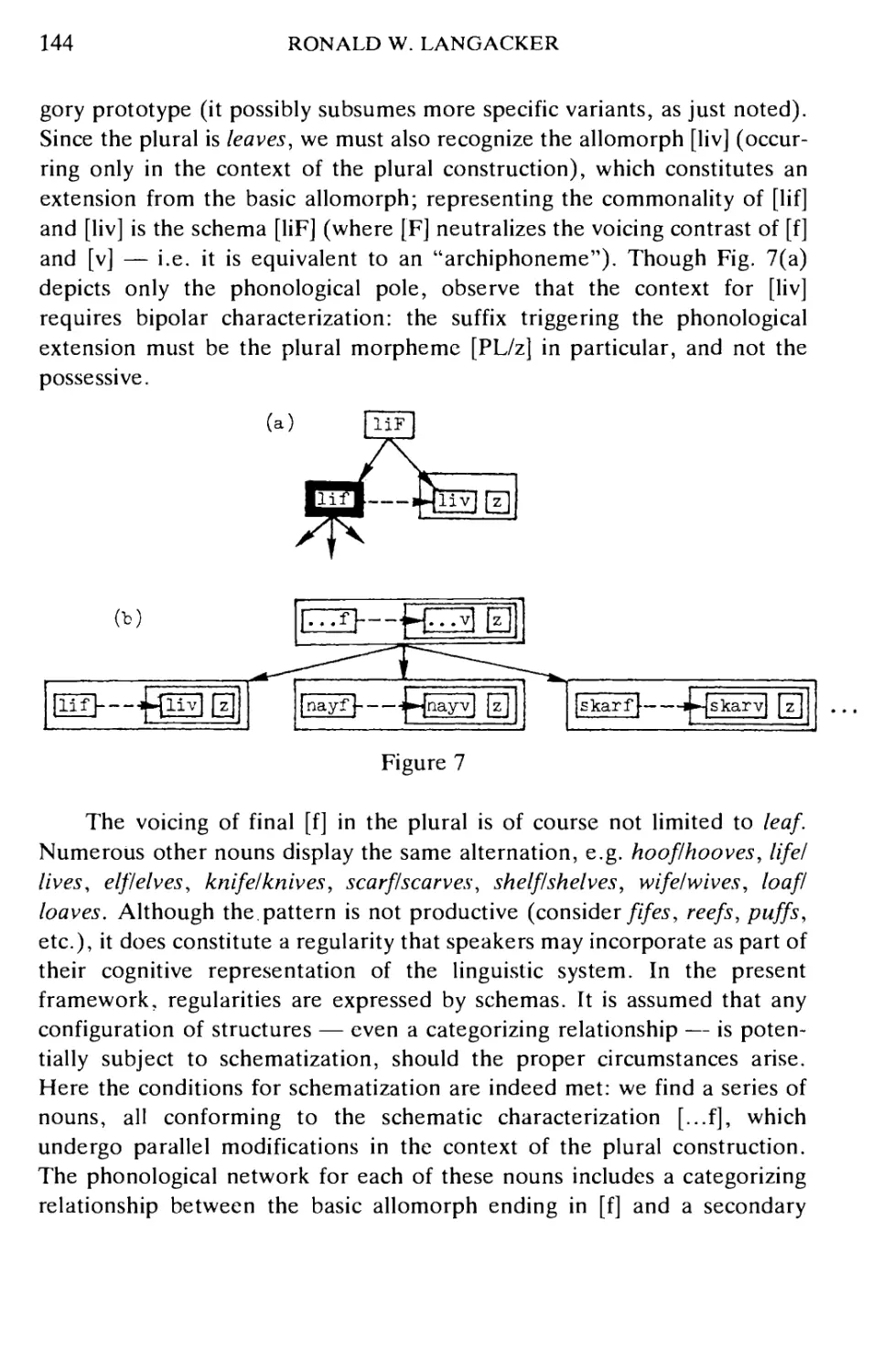

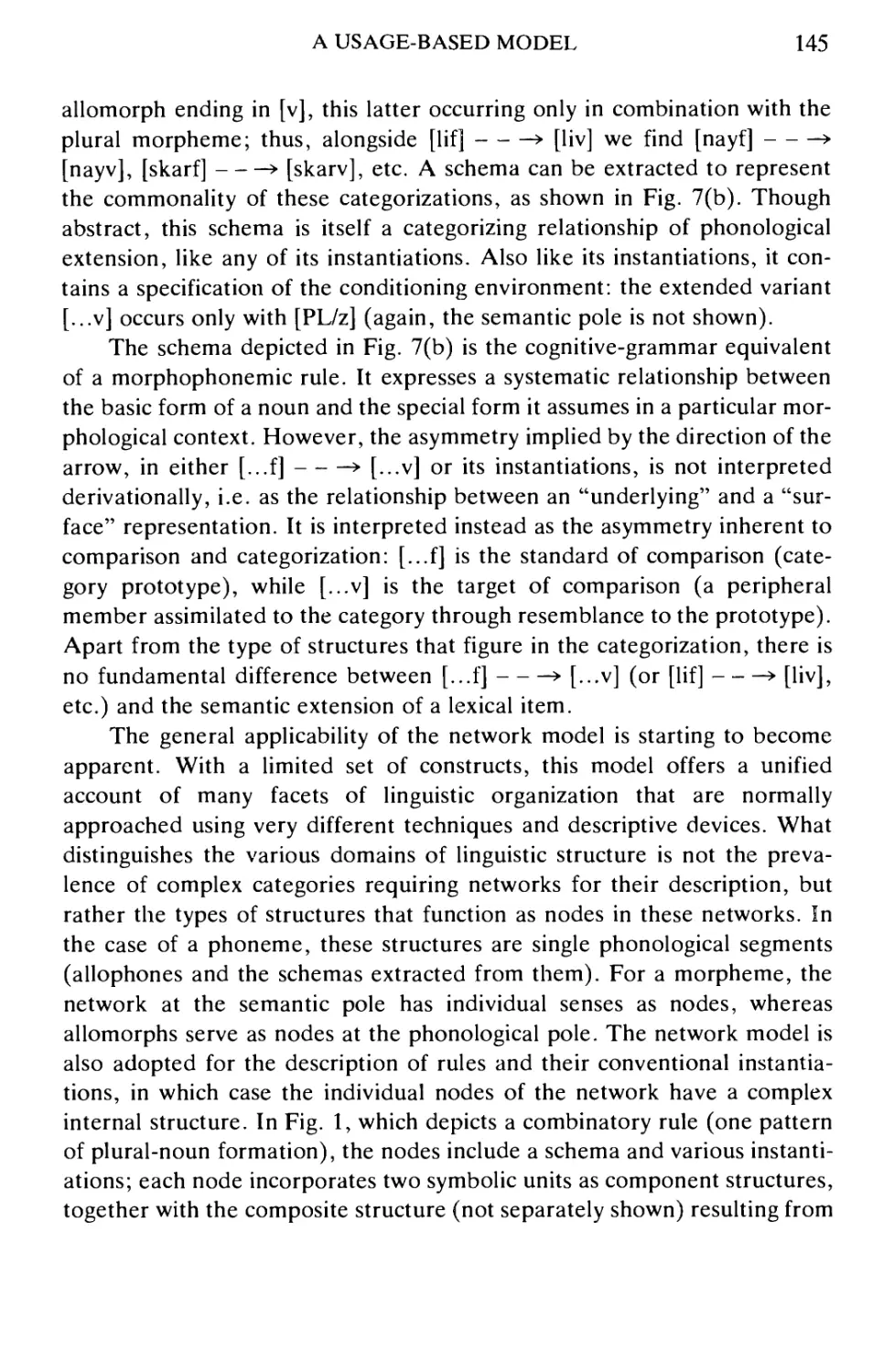

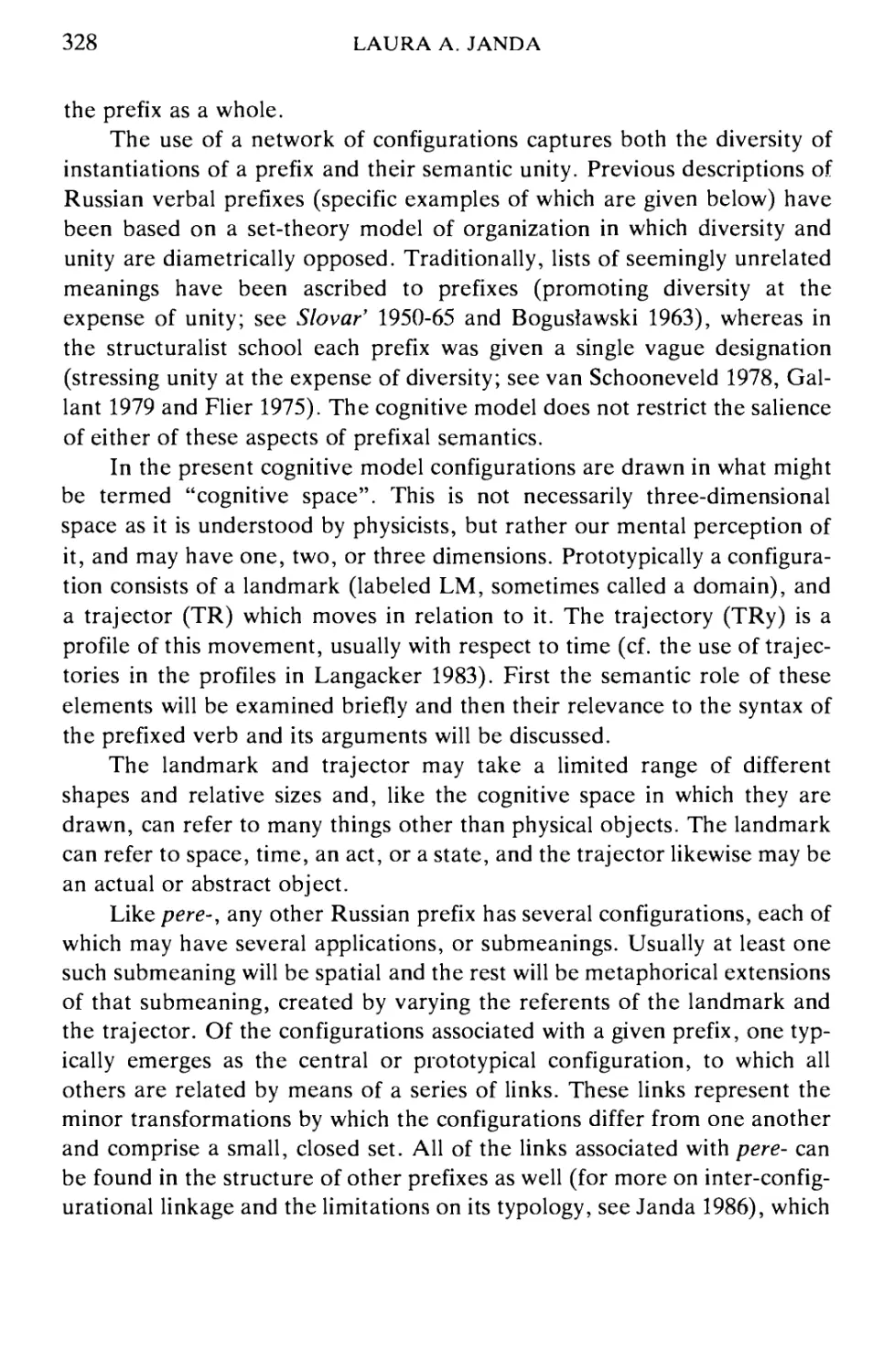

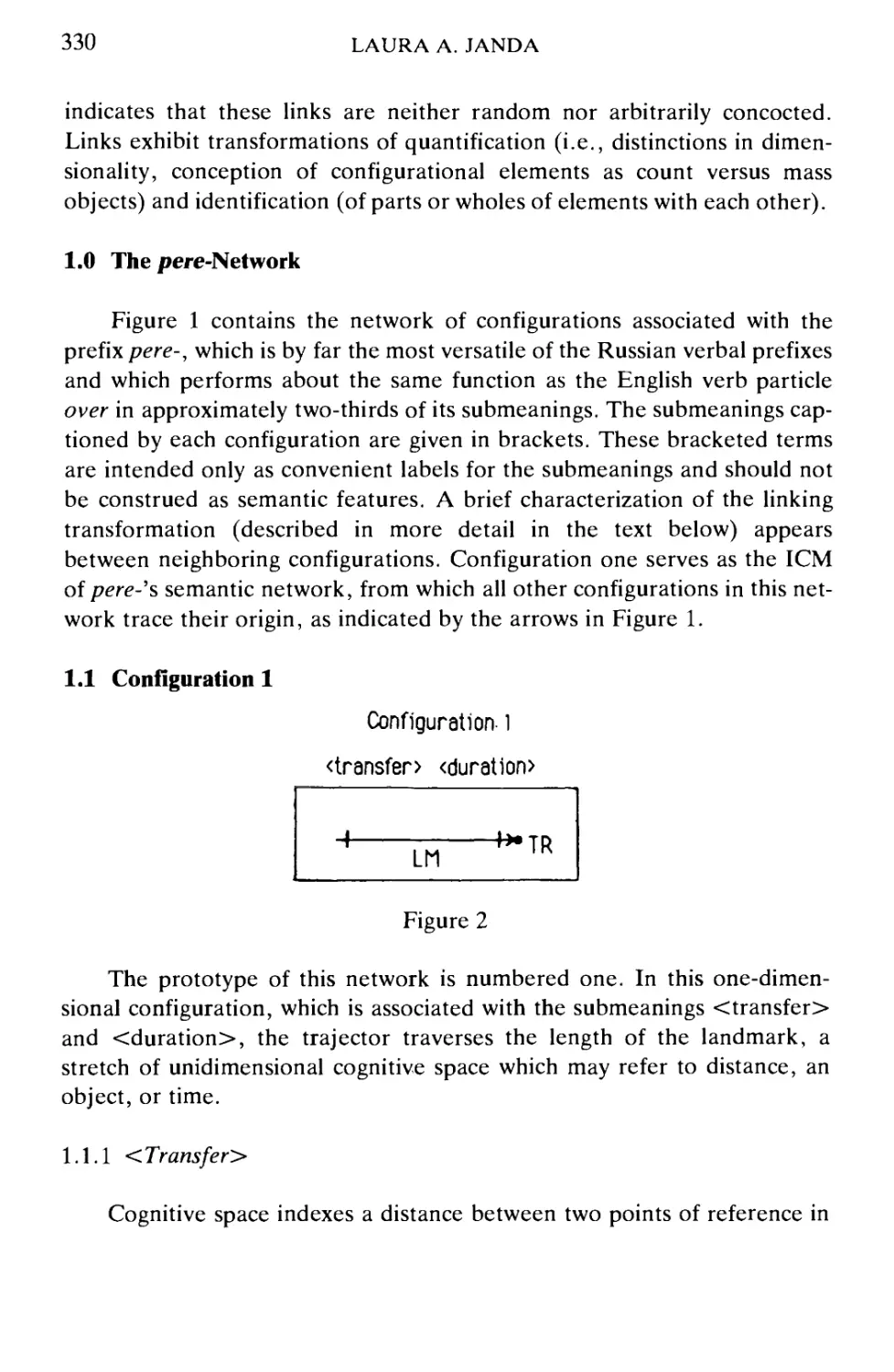

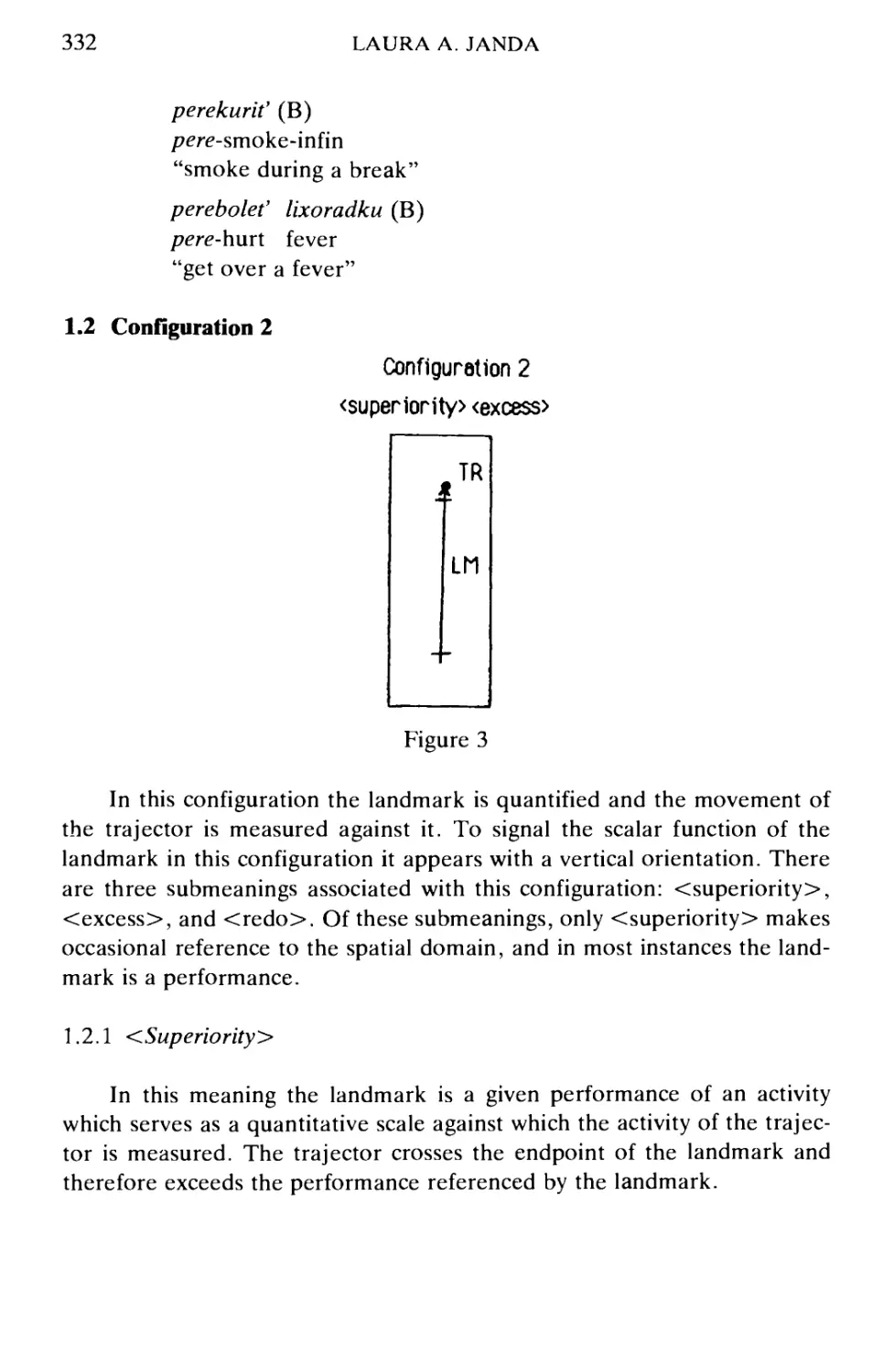

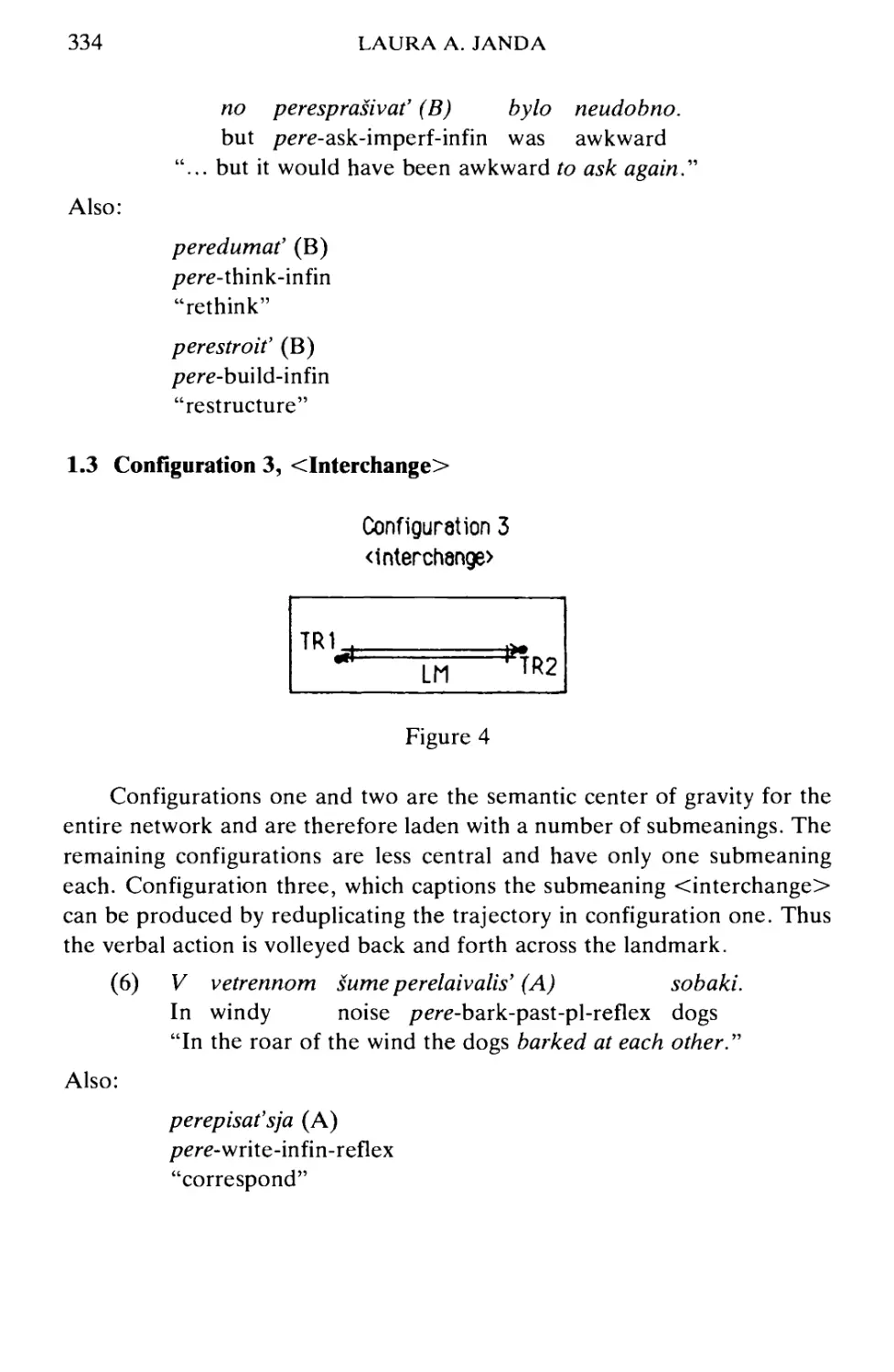

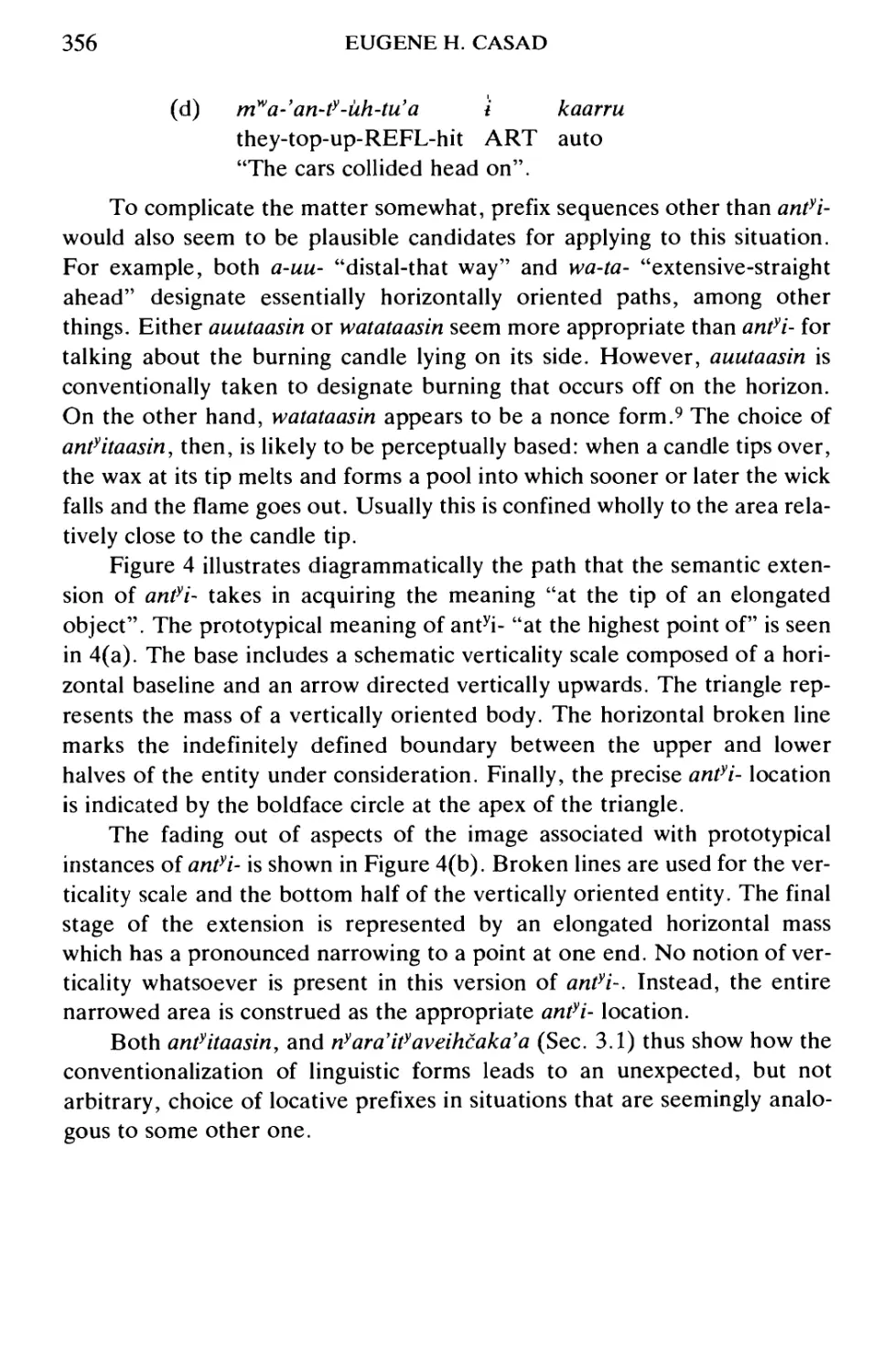

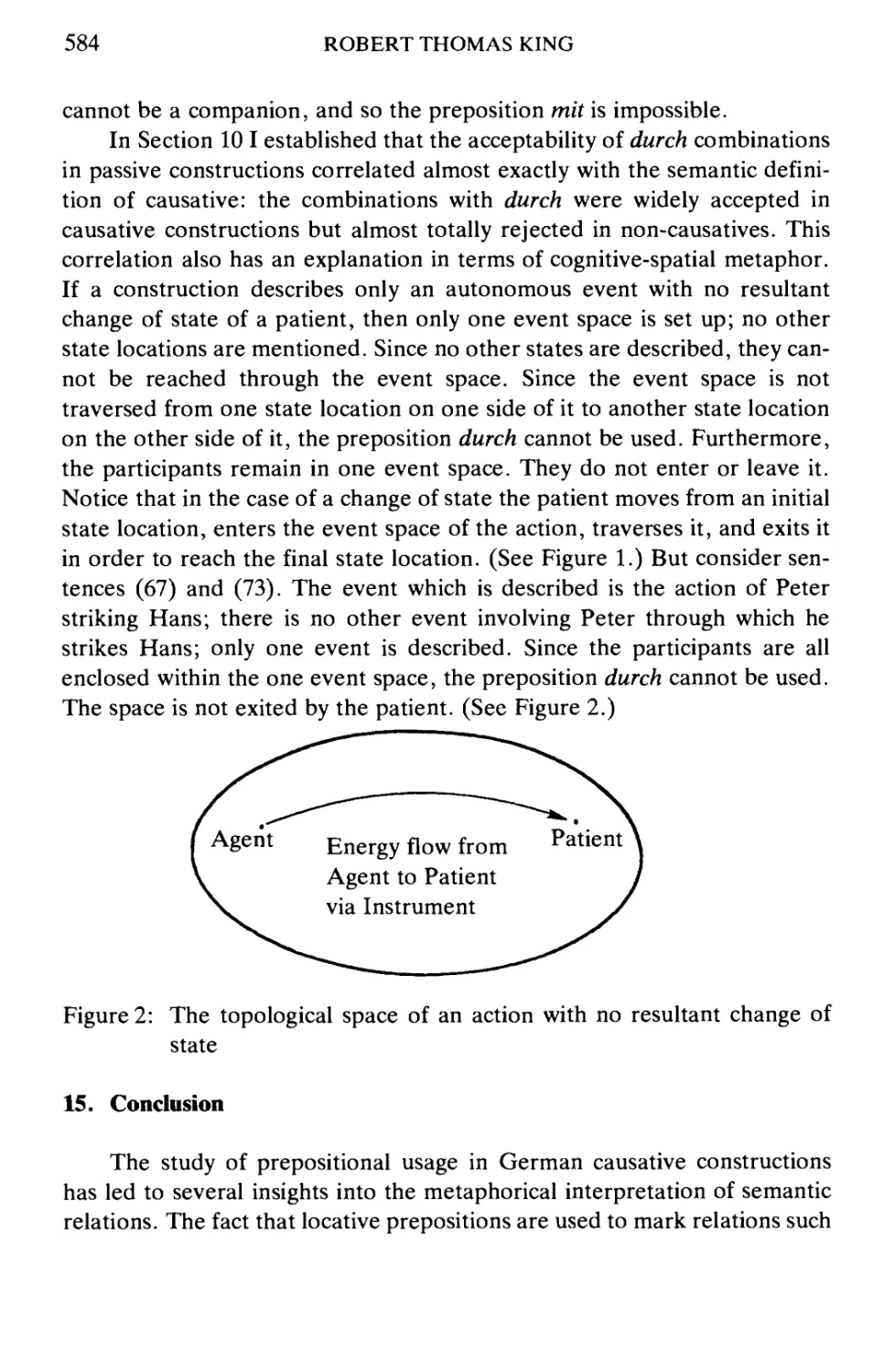

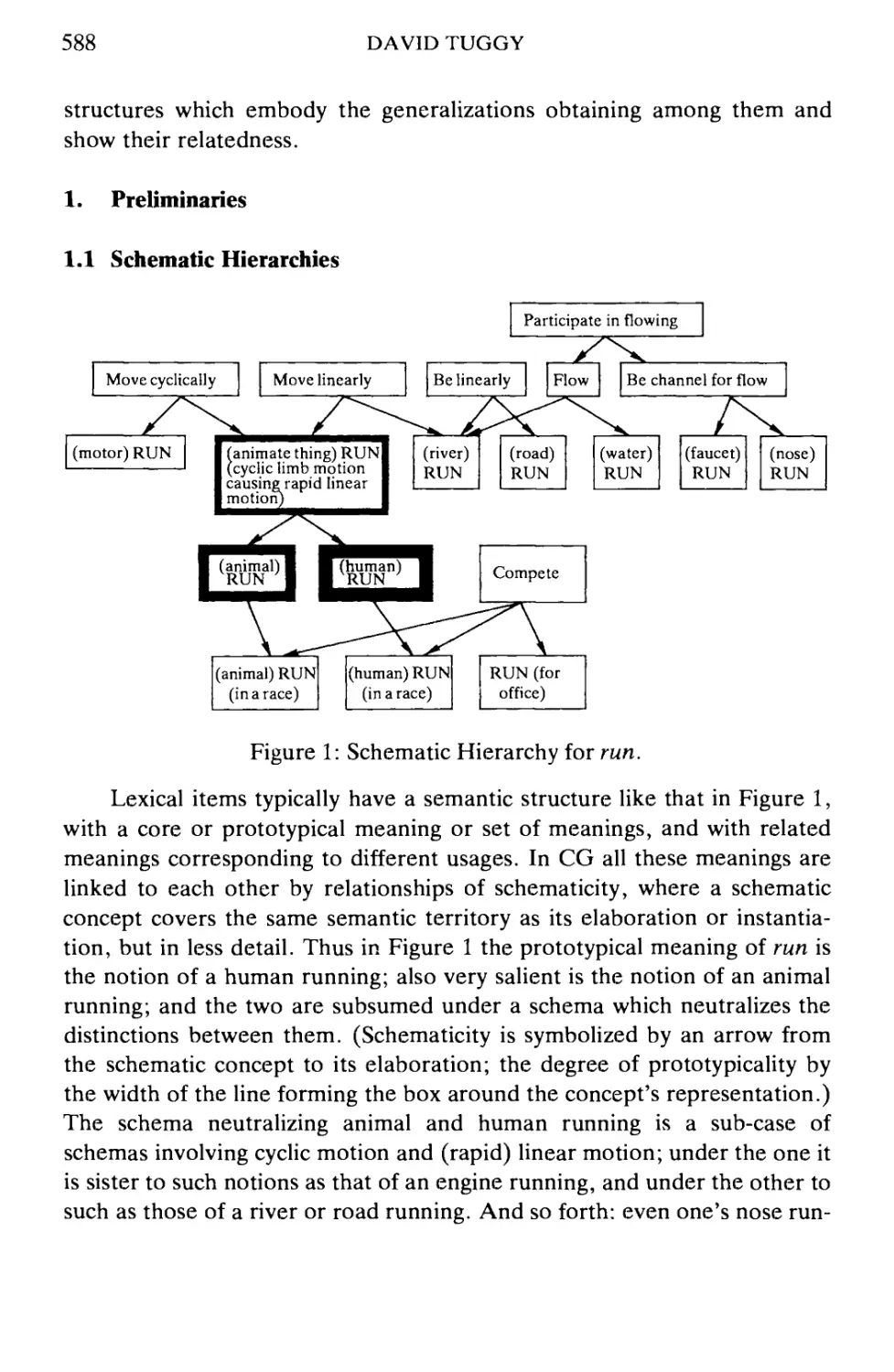

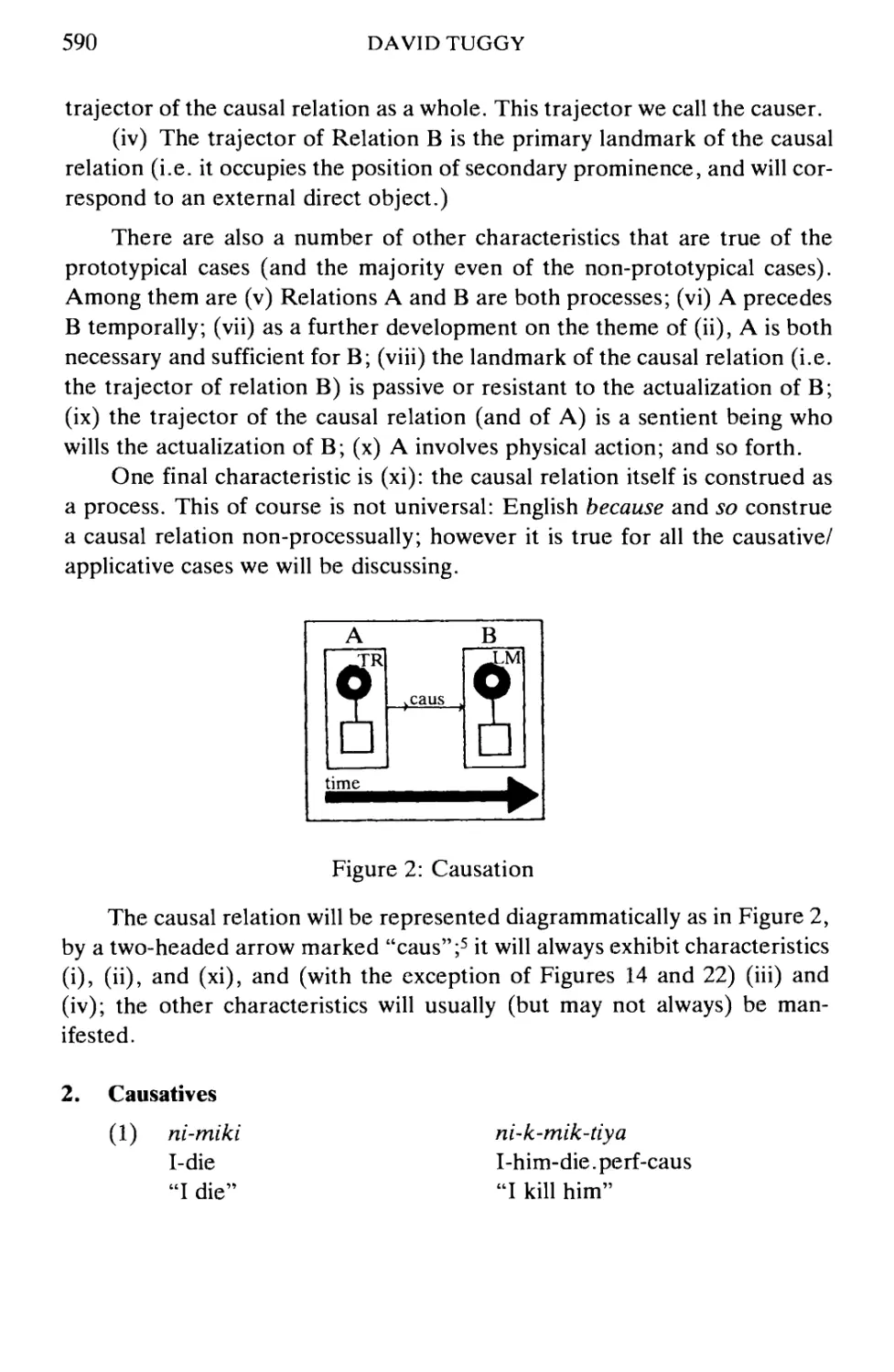

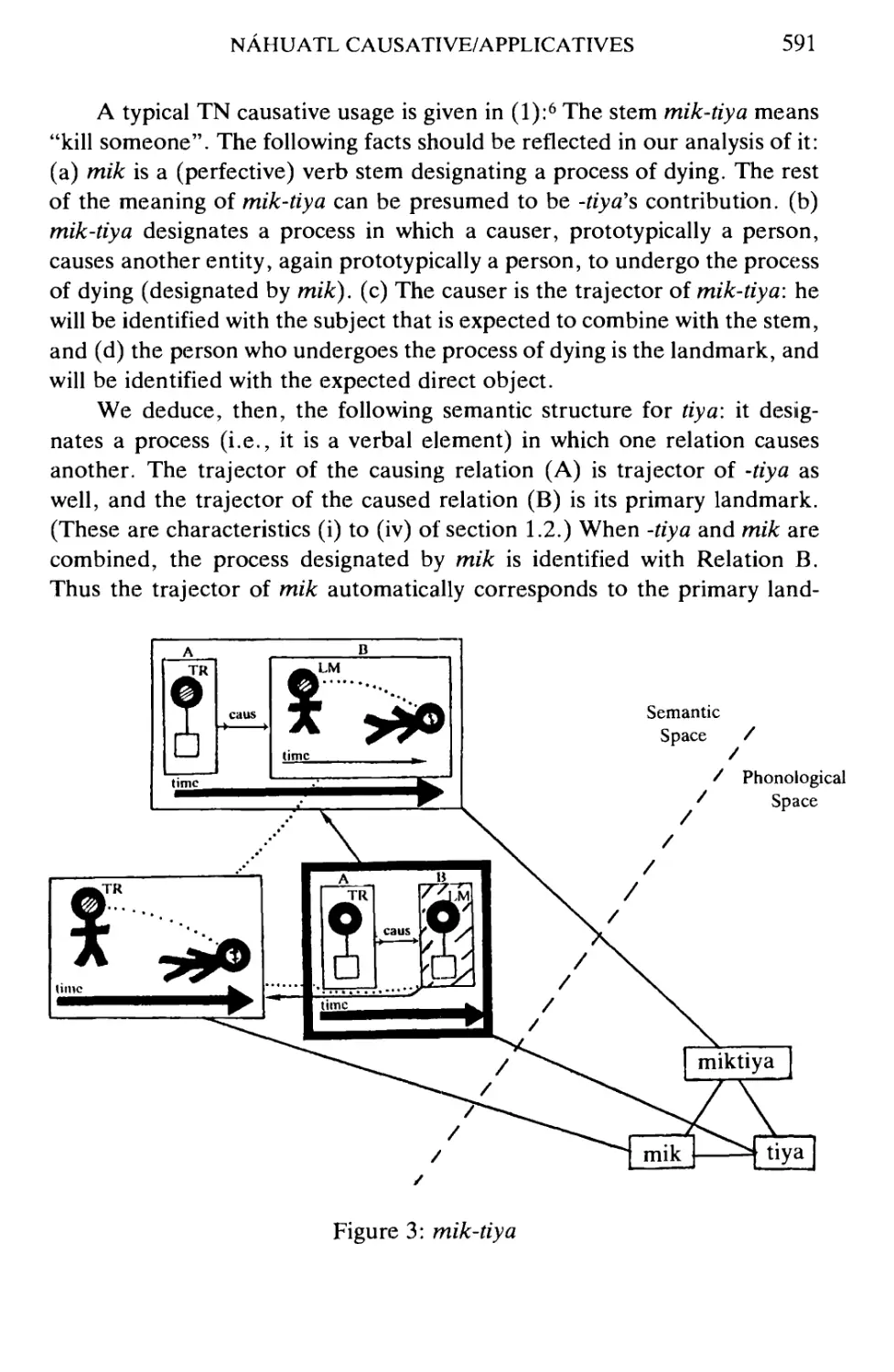

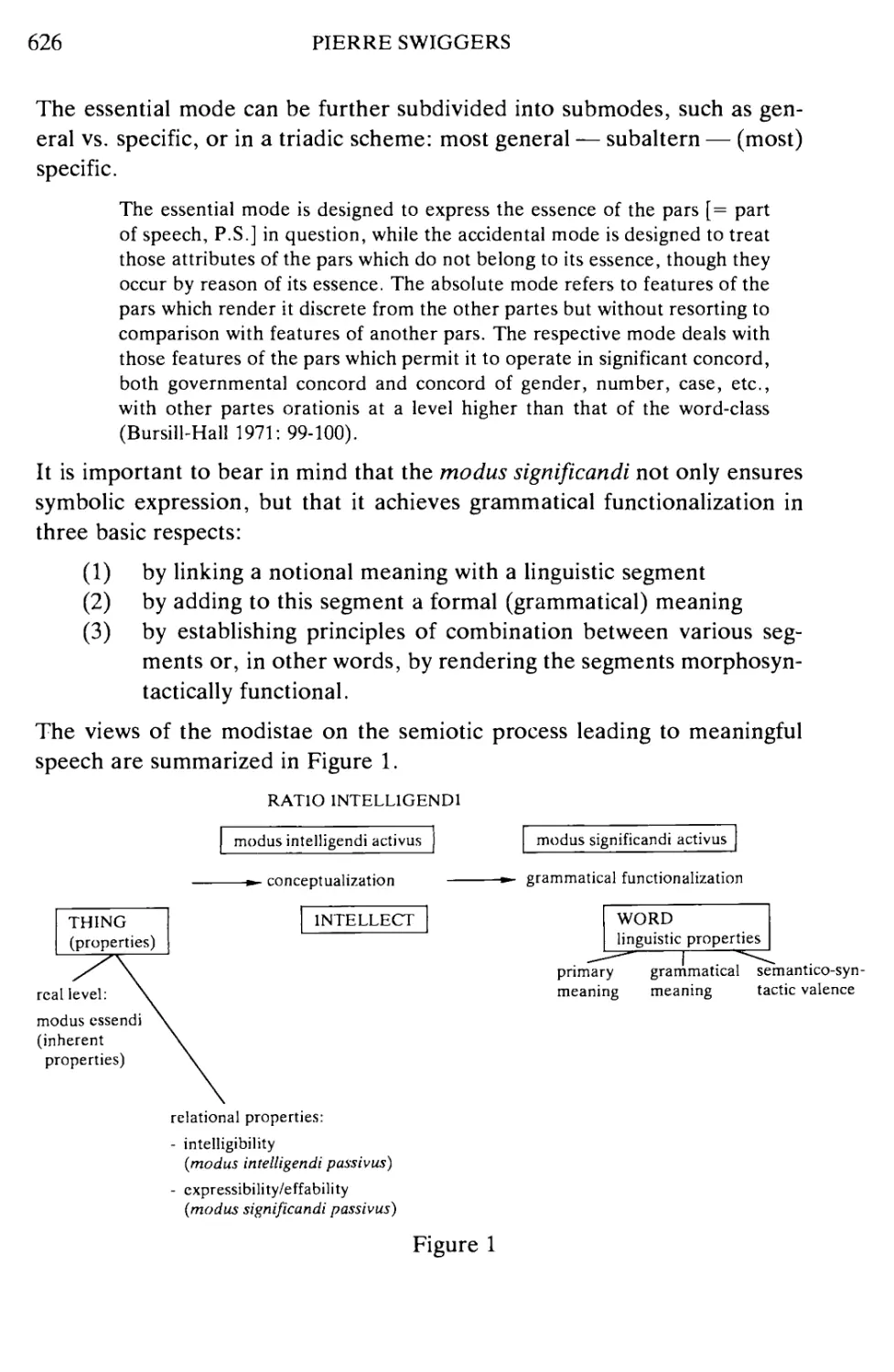

expressions. The validity of such an argument depends on how the pivotal notions