Текст

MEDIEVAL HERALDRY

Some Fourteenth Century

Heraldic Works

EDITED

WITH INTRODUCTION

ENGLISH TRANSLATION OF THE WELSH TEXT

ARMS IN COLOUR, AND NOTES

BY

EVAN JOHN JONES

FOREWORD BY

ANTHONY R. WAGNER

Richmond Herald

CARDIFF

WILLIAM LEWIS (PRINTERS) LTD

19 + 3

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Main entry under title:

Medieval heraldry.

Reprint. Originally published: Cardiff: W. Lewis

(Printers), 1943.

Bibliography: p.

1. Heraldry—Addresses, essays, lectures.

I. Jones, Evan John.

CR21.M43 1983 929.6 78-63502

ISBN 0-404-17149-4

AMS PRESS, INC.

56 East 13 Street, New York, N.Y. 10003

Reprinted from an original in the collections of the Uni-

versity of Michigan library of the edition of 1943, Cardiff.

MANUFACTURED

IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

То ту

Mother and Father

CONTENTS

Page

Preface vii

Foreword by A. R. Waoner x

Introduction xvii

Llyfr Arfau by John Trevor, and English

Translation 2

Tractatus de Armis by Johannes de Bado

Aureo

Text i 95

Text 2 144

Tretis on Armes by John [Vade] 213

Appendix I: De Insigniis et Armis by

Bartolus de Saxoferrato 221

Appendix II: Identification of certain

of the Arms illustrated in the book 253

Welsh-Latin Word List 255

Bibliography 2 58

Authorities cited in Text . . 259

PREFACE

Some years ago, while collecting material in my

research, I came across in manuscript and in print,

texts which, although they were in different languages

and on subjects far removed from each other, seemed to

be the works of one writer. These included portions

of the well-known Eulogii Historiarum Continuatio, a

Welsh Life of St. Martin, a French Metrical History

of the Deposition of Richard II, and a Welsh Book of

Arms.

It seemed to me that the Welsh Book of Arms

deserved attention as an interesting specimen of

medieval Welsh prose: its author claimed that Welsh-

men should read it carefully and master the science

of arms. I set about comparing it with other heraldic

treatises, and I found that it resembled very closely

a work by De Bado Aureo, namely, Tractatus de Armis.

After giving the work careful study, and receiving

encouragement from colleagues and friends, I decided

to present the results of my labours to a larger public,

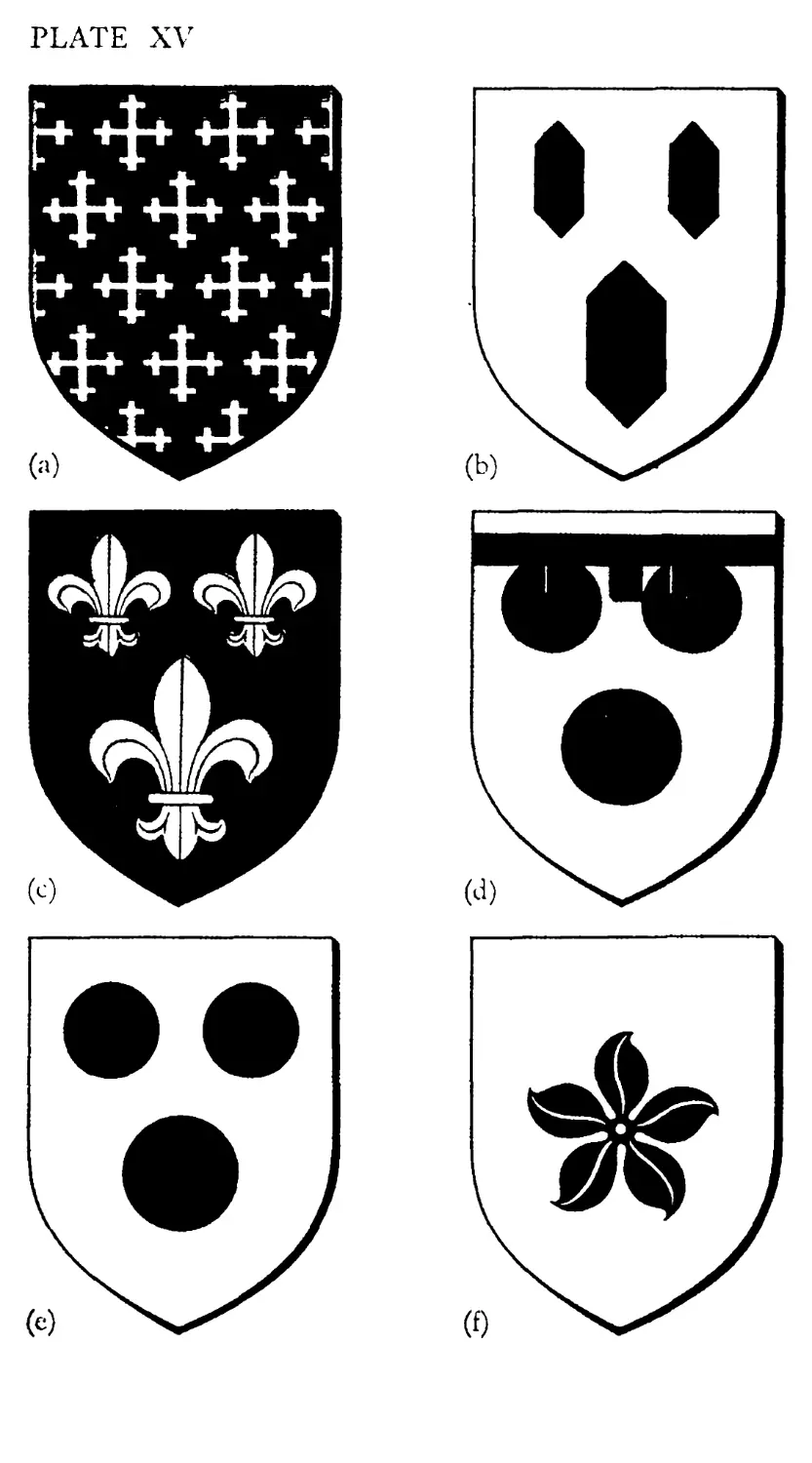

so that the theories could be tested with reference to

the sources themselves. I hope that the texts will also

be regarded as having literary as well as historical

value.

I have not attempted to give the reader an exhaustive

treatment of medieval works on Arms: that may be

possible in the near future. Here I am concerned

only with those Latin and Welsh works which can be

vii

attributed with a degree of certainty to De Bado Aureo.

I have added an English treatise which the reader will

find to be closely related to the other works. I have

also included the De Insigniis et Armis of Bartolus, long

out of print, because of its importance to De Bado

Aureo.

I wish to put it on record that my interest in heraldry

was stimulated from the beginning by that versatile

and generous scholar, the late Cyril Brett, Professor

of English Language and Literature at University

College, Cardiff. To him I continuously submitted

my theories and presented my difficulties: his advice

and helpful criticism were always designed to encourage

me to further effort. I wish I could have had the

benefit of his ripe judgment throughout the preparation

of this work.

My gratitude is due to Mr. A. R. Wagner,

Richmond Herald, for being so ready to write the

Foreword, and showing such friendly interest in this

book. I wish also to express my thanks to colleagues:

to Mr. G. J. Williams and Mr. L. J. D. Richardson

for faithful reading of script and proof sheets, and many

useful suggestions; to Mr. J. Hubert Morgan for

assistance in the early stages of the work and for

directing me to sources of information. I have also

profited much from discussion with colleagues and

friends.

To members of the staffs of the British Museum,

the Bodleian Library, the National Library of Wales,

the Central Library, Cardiff, and the University

viii

College Library, Cardiff, I desire to return thanks for

their courtesy and for affording me many facilities

during the preparation of this work.

To Mr. T. C. Hart, of Messrs. William Lewis

(Printers) Ltd., I owe thanks for his personal help

and patience while the book was being printed; and

to .the artist responsible for the illustrations I am

particularly grateful.

Lastly I wish to acknowledge the generous award

of £50 received from the University of Wales

(Thomas Ellis Memorial Fund).

EVAN J. JONES.

University College,

Cardiff,

1943-

ERRATA

Plate VI (c)

XV (d)

XXVI (f)

or instead of gules.

above label or.

martlets or.

ERRATUM. Plate XXXIa should be argent Hon rampant tabU.

ix

FOREWORD

By Anthony R. Wagner, Richmond Herald.

The Tractates de Ar mis, attributed in one copy to a

mysterious Johannes de Bado Aureo, is the oldest

known treatise on heraldry by a native of these islands.

That the author was our countryman is shown by his

statement that he wrote at the instance of Richard the

Second’s Queen Anne, since deceased, and by his

reference to the heraldic practice of the King of

England and English lords. But his work, he tells us,

is based on that of a Frenchman, his master Franciscus

de Foveis. Neither Franciscus de Foveis nor his

work has been identified and indeed the only known

treatise on heraldry older than the Tractates is that of

Bartolo de Sassoferrato, also here edited by Mr. Evan J.

Jones.

It might have been thought that heraldic interest

and national pride would have combined to draw

scholars’ attention to this little work, and it is or should

be a matter for some shame that its only previous

editor, Sir Edward Bysshe, has had to wait near on

three centuries for a successor. It was not, Mr. Jones

tells us, that his work needed no revision. In his

volume of 1654 were comprised besides the text of the

Tractates, that of Nicholas Upton’s treatise De Studio

Militari, and of Bartolo’s heraldic work above men-

x

tioned, notes on all three, and Sir Henry Spelman’s

essay on early heraldry called Aspilogia. Whatever its

faults this was a notable and scholarly beginning of

the editing of heraldic source material, for which

Sir Edward might almost be forgiven his change of

allegiance and usurpation of Garter’s place under the

Parliament, were it not that his professional misconduct

after the Restoration brought fresh disgrace and trouble

on his colleagues.

The heraldic part of Upton’s work is an amplified

version of the Tractatus. We might credit Upton

with the enlargement of an older work but for one fact.

A passage in this heraldic section recants certain stric-

tures on the colour Vert, which, says the author, he

made in a youthful work. But just such strictures

are made in the Tractatus so that we can hardly doubt

but that this at least of the Upton additions is the work

of the original author. Bysshe thought to cut this

knot by making the Tractatus an early work of Upton,

but that will not do, if, as seems most likely, Queen

Anne, at whose instance the Tractatus was begun,, died

before Upton was born. We must then conclude that

Upton, in the manner of his age, incorporated in his

book without modification or acknowledgment a later

revision of the Tractatus by its own author.

The more complete solution of this and connected

problems must await the full examination of the text

of Upton which it is to be hoped Mr. Jones will now

undertake. Upton has had a little more attention

from modern scholars than the Tractatus, for “the

essential portions” of a sixteenth century English

translation of his work were edited in 1931 by F. P.

xi

Barnard.1 These “essential portions” do not, how-

ever, include the heraldic part though Barnard was a

good and keen heraldic scholar. There is a reason

for this neglect. The objection modern heralds have

to the Tractatus in all its versions is characteristically

expressed by Oswald Barron.

“From the day,” he says, “when John of Guildford

(i.e. Johannes de Bado Aureo) sat down to write a book

upon heraldry that should follow, in dogma and

tradition, the rules of his most excellent teacher Master

Franciscus de Foveis, our authors have wandered into

waste places. At the beginning they go astray seeking

symbolism and an inward significance in every sign

upon the painted shield. For an example I give you

Nicholas Upton and his work.

“The English antiquary may well mourn the folly

of Nicholas Upton. [Barron here attributes to Upton

himself the heraldic part of the De Studio Militari.\

He was gentleman born, was Nicholas, of that freeborn

blood which was reckoned as our English nobility.

Bred at a university, he followed the wars in France

under great captains, the fighting Earl of Salisbury,

Thomas, Earl of Suffolk, and the renowned Talbot,

not one of whom died in bed. He had seen battle and

siege and skirmish, knightly pomp in war and peace.

When he comes home again after nine or ten adven-

turous years to write a treatise on heraldry, you would

say that here is the man who shall tell us all about the

heraldic practice of the days of Agincourt and Orleans.

1 The essential portions of Nicholas Upton’s De Studio Militari before

1446. Translated by John Blount, Fellow of AU Souls (c. 1500); edited

by Francis Pierrepont Barnard. Oxford, 1931.

xii

“And then you come to his book and find it all a

puzzle without an answer. In his first chapter you

are in a mazy argument over the significance of colours

and what the philosophers say of their generation and

why certain colours are nobler than others. You go on

to the chapters of crosses and bars and bends, of lions

and leopards and hounds and at the last you see the

truth about Nicholas Upton. He did not sit down to

describe to you the practice of that armory which was

any day’s common spectacle in the jousting yard. That

were no task for a scholar’s pen. He was there among

his books of philosophy and natural history to give

you that more precious heraldry which should arise

out of a scholar’s meditations. The men in the street

could blazon bars and bends, but Nicholas Upton and

his fellows can tell them the unguessed meanings of

colour and charge, find strange bearings that were

never on banner or shield and beautiful words for

them all.

“Thus the tradition of the heraldry book is established.

As an Englishman, I like to believe that the follies

which French antiquaries have named as sottises

anglaises were imported goods from over-sea, that the

bad tradition began in foreign parts. But we followed

it lovingly.”

It is true. The Tractatus tells us little about

contemporary heraldic practice and more than once

where it purports to do so is demonstrably in error.

The passage about the bearing of chevrons by clerics

(pp. 64, 130,1 81) bears no sort of relation to any known

practice. Less likely to mislead, because so thor-

oughly fantastic, are such statements as that the King

xiii

of England bears Gules, the colour of fire, because

Anglici are Inglici or igne electi; that singers being

knighted bear swans; that to bear martlets is a sign

that a man is ennobled through his bravery (or perhaps

rather that he is of small substance); or that those who

bear piles do so to show that they have grown rich by

labour. Once our author is constrained almost to

apologize for his own absurdity; for having told us

that to bear lucies is the mark of a rapacious and

oppressive man (for pike are rapacious fish), he feels

bound to qualify this by allowing that there are indeed

some who bear such merely because their name is

Lucy!

It is surprising, therefore, that Barron and others

have thought it worth while to quote the De Studio

Militari as decisive on a heraldic point of some import-

ance where it happens to support their own view, the

passage namely where the writer expresses disapproval

of the opinion that heralds can give arms and asserts

his own view that arms so given are of no greater

authority than those taken by a man for himself. It

would be judicious at any rate to quote on the other

side a passage from the original Tractatus (p. 142): “I

ask then, who can give arms ? And do thou say that a

king, a prince, a king of arms, or a herald can do so, as

saith Bartholus.” It would be relevant too to note

where our author says that such and such an alteration

of arms should be made “cum concilio regis haraldo-

rum,” where he says that a King of Heralds should

assign such and such crosses to one of whom he knows

neither good nor ill, and where he tells of a King of

Arms (with a sense of humour ?) who assigned the

xiv

bearing of a swan to some who were not singers, but

were beautiful and had long necks!

The truth is that while these treatises will disappoint

if we go to them looking for plain matter of fact

accounts of contemporary practice, both by what they

tell us wrong and by much that is irrelevant; yet if we

go to them expecting nothing we shall find, a fair deal

of useful plain statement and a good deal more sugges-

ted or to be inferred. The colour and beast symbolism

which they expound does not interest heralds because

the attempt to import it into heraldic practice failed,

at least in England. Sicily Herald’s Blason des

couleurs suggests that it had a little more success beyond

the channel. But heraldic or non-heraldic this sym-

bolism has its own history to which our treatise has a

contribution to make.

Other of its fantasies may prove less remote from

heraldic actuality than we suppose. Fifteenth century

English heraldry is full of transient and ill-known

eccentricities. It may prove that among them are

legacies from the Tractatus. Till a few years since it

was hardly known that Sicily Herald’s fantasy of blazon

by gems had been seriously used at all in England, let

alone that it was adopted in a quasi-official record of

Henry VII’s reign.

And if English fifteenth century heraldry be little

known, how much less known is that of Wales. The

Welsh text of the Tractatus avows the purpose of

educating Wales in heraldry, and falling there on

virgin soil may well have moulded actual practice in

a way not possible in England where heraldry was well

established and developed. A passage quoted by

xv

Mr. Jones from Lewis Glyn Cothi (p. 1) suggests

what manner of influence may and should be

looked for.

The study of these things is in its infancy. Till it

has gone further, conclusions can be only tentative.

The first need is to make texts and facts available. To

this process Mr. Jones’ present edition is a contribu-

tion, valuable in itself and as a pioneer to show the

way to others.

xvi

INTRODUCTION

Some time after the death of Anne of Bohemia, the

queen of Richard II, there appeared a Latin treatise on

heraldry, under the title of Tractatus de Armisl The

author of this work was lohannes de Bado Aureo. It

was not completed before the year 1394, the year of

the queen’s death, for the author states in his intro-

duction that he had written it at the instance of the

queen lately deceased.2

This Tractatus was printed in 1654 by Edward Bysshe

along with two other heraldic works, viz. the De Studio

Militari of Nicholas Upton, and the Aspilogia of Henry

Spelmann.3 A comparison of the Tractatus and the

De Studio Militari led Bysshe wrongly to suppose that

they were the works of one author, and that the

Tractatus was the earlier effort, which in a corrected and

enlarged form was incorporated in the De Studio.

Bysshe was forced to conclude that Upton had adopted

the pen-name lohannes de Bado Aureoy a name which he

held to be fictitium planed

JB.M. Add. MS. 29901. Tractatus Magistri Iohannis de Bado Aureo

cum Francisco de Foveis in distinctionibus armorum. (Small folio, paper,

fifteenth century.)

aQuoniam de armis multociens in clipeis depictis singulis discernere

inveniatur difficile, ad instantiam igitur quarundam personarum,

& specialiter Domine Anne, quondam Regine Anglie, hunc libellum compilavi.

3Nicholai Vptoni, De Studio Militari, Libri Quattuor, lohan. de Bado

Aureo, Tractatus de Armis, Henrici Spelmanni Aspilogia, Edoardus Bissaeus

E codicibus MSS., primus public! juris fecit, Notisque illustravit. Londini.

Typis Rogeri Norton . . . 1654. Folio.

‘Bysshe’s theory reads thus : Se iuvenem adhuc, ait, librum conscrip-

sisse, quo insignia viridis coloris habuit inhonorata, cuius iam erroris ilium

paenituisset. Quibus ergo verbis animum induxi ut crederem libellum

quern de tesseris gentilitiis nunc public! iuris facio, sub nomine Iohannis

de Bado Aureo, opus fuisse Nicbolai Uptoni, illic enim viridis insignium color

damnatur. Quid ? quod methodus & ipsa etiam verba ubique congruunt.

[Continued on page xviii

xvii

в

Apparently Bysshe had at his disposal two De Bado

manuscripts, one from the library of Le Neve, and the

other from the library of the Heralds’ College;1 is

this latter copy now in the possession of the Society of

Antiquaries ? He also mentions several copies of the

De Studio Militari which were consulted by him.2 It

Continued from page xvii]

Neque ego unquam, vel praeter me alius quisquam, familiam istius nominis,

quae usquam extiterit reperiri potuimus. Fictitium plane nomen esse

videtur, et nisi ille idem Uptonus sit, auctorem hunc inter ignotos babeo.

xDuos huius libri codices habui manuscriptos, quorum unum Bibliotheca

Guilielmi Le Neve, alterum nostra suppeditavit.

There are two copies in the British Museum (Add. MSS. 37526 and 29901).

Both are of the fifteenth century. The former does not mention the name

of the author, and the latter, which agrees more closely with Bysshe’s

printed version, mentions the author as De Bado Aureo. The third copy,

now owned by the Society of Antiquaries, supplied Bysshe with the greater

part of his text and the coloured drawings of the arms. In it the name of

the author is not mentioned. Add. MS. 37526 belonged to Le Neve as is

shown by his arms, arg. on cross sa. 5 fleurs de lys of 1, painted inside the

C of the word Cum in the opening sentence.

Another interesting version is that of British Museum MS. 28791. This

differs from the three already mentioned and approximates somewhat to

the heraldic sections found in the De Studio. (See pp. 144—212) It was

copied in 1449.

Armorum tractatus extractus anno domini millesimo CCCCmo XLIXm0

regnique Regis Henrici Sexti post conquestum Anglie vicesimo octavo,

partim ab illo tractatu edito ad instanciam domine Anne quondam regine

Anglie, secundum tradicionem Francisci, partim ab aliis. (The copyist’s

explanation of the sources is at fault as will be seen by comparison with

De Bado's own introduction.)

aThere are two copies in the British Museum and one (Arundel MS. 64)

in the College of Arms. They all belong to the fifteenth century. The British

Museum copies are Add. MS. 30946 and Cotton MS. Nero, C. 3. Later

transcripts are British Museum Harleian MSS. 3504, 6106, and Trinity

College (Oxford) MS. 36. Bysshe states that he used Cotton MS. and two

copies then in Selden’s possession, as well as one from Le Neve’s library.

The Arundel MS. was one of the Selden copies used by Bysshe. There is

also a MS. at Trinity College, Dublin (T.C.D. MS. 801, E. 1. 7), at present

inaccessible (for security reasons). The librarian, Dr. J. G. Smyly, has

kindly given me this description of it from Monck Mason’s unpublished

catalogue (c. 1814) of Latin MSS. in the Trinity College Dublin Library:

“Liber secundus Nicholai Upton, canonis Ecclesiarum Sarum & Welliae,

de regulis & signis in armis depictis,” cum tabulis armorum “exscripsit

Christopherus Ussher, alias Hibernicus.”—F.st tractatulus iste pars haud

plusquam dimidiae huiusce autoris “De Studio Militari.’’

xviii

appears, however, that he did not seriously apply him-

self to collate his texts; for a clearer understanding of

the significance of the manuscript variants would have

shown that De Bado and Upton could not possibly have

been the same person.

The De Studio Militari as we have it in Bysshe’s

edition is divided into four books: the first is devoted to

military affairs, de militia nobilitate^ the second to

acts of war, de bellis & actibus exercitus in eisdem, and the

third and fourth books to heraldic problems, nobilitas

colorum in armis depictorum, regule per quas colores

Armorum & ipsa Arma clarissime discernuntur. Appar-

ently, when Bysshe saw that these third and fourth

books were to some extent a development of the De

Bado tractate, and that Upton had claimed to have

written the whole of the De Studio, he felt justified in

assuming Upton to be the author also of the De Bado

tract.1 This supposition seemed further justified by a

reference in the De Studio to an earlier version, where

the author expressed regret that, as a young man, he

*Upton was bom about the year 1400. He entered Winchester as a

scholar under the name of Helyer, alias Upton Nicholas. He afterwards

became Fellow of New College, Oxford, and later, though ordained sub-

deacon, he forsook higher orders and entered the services of Thomas de

Montacute, the fourth earl of Salisbury. He fought against the French in

Normandy, served under John Talbot, afterwards Earl of Shrewsbury, and

was with him when he was killed near Orleans in 1428. Upton was later

persuaded by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, to renew his studies, and in

1431 he was admitted to the prebend of Dyme in Wells Cathedral. Before

October 2, 1434, he was rector of Chedsey, which he later exchanged for

the rectory of Stapylford. In 1438 he graduated in Canon Law at Broad-

gates Hall (afterwards Pembroke College). He was collated to the prebend

of Wildland in St. Paul’s Cathedral in 1443 ; but he resigned this in favour

of the office of precentor of Salisbury Cathedral. In 1452 he went to Rome

to obtain the canonisation of St. Osmund, the founder of the cathedral.

He died before July 15, 1457, and was buried at Salisbury Cathedral.

(See article sub Upton, by A. E. Pollard, D.N.B.)

XIX

had written an earlier version in which he had made

serious errors {quae sunt veritati contrarid) J

Although Bysshe had consulted six codices2 for his

De Studio^ he did not make any serious attempt at

collation. An example of his failure to see the signi-

ficance of different manuscript readings appears in the

fourth book, pp. 133—46. Here, inserted between

chapters De Leone and De Leonardo, which clearly

belong to the heraldic section, we find fourteen sections

of extraneous matter, which undoubtedly belong to the

De Milicia section. These are

Statuta Henrici quinti tempore guerre.

De ecclesiis & Sacramento Eukaristie.

De personis ecclesiasticis.

Quibus personis tenebuntur omnes obedire.

De vigiliis & gardiis observandis.

De monstris publicis sen ostencionibus.

De turbationibus & clamoribus publicis.

De equitationibus generalibus.

De hospiciis capiendis.

De prisonariis. De terciis. De spoliis non fiendis.

xThe actual quotation to which Bysshe refers reads :

Veruntamen olim, in annis meis iuvenilibus, scripsi in hac materia nimium

sompniando : in qua quidem scriptura fateor me multipliciter errasse, ut

in dampnando colorem viridem, ac multa alia posuisse, que sunt veritati

contraria ; que iam ex certa mea scientia revoco. Utinam omnes copie de

ilia lectione mea extracte mecum essent; quas protestor me antea non

dormiturum, quousque ignibus consumassem.

*hun<^hblici juris facimus ; hortante praecipue, & hoc opus adjuvante

Domino Seldeno, qui mihi in hac re duobus pulcherrimis codicibus MSS.

opem tulit; quorum alterum Matthaeo Haleo, patrii, omnisque juris scientis-

simo, prius datum ab eo mihi exoravit mutuum. Tertium suppeditavit

Bibliotheca Domini Cottoni Equitis & Baronetti, qui Roberti Cottoni

Equitis clarissimi' filius est, tanto patri dignissimus. Quartus erutus est

ex Bibliotheca Guillelmi Le Neve Equestris Ordinis Viri. Aliique duo

eximii mihi ipsi prae manibus erant; quorum praestantior ad aliquem ex

pervetusta & Equestri Lambertorum familia pertinuisse visus est, uti

depicta variis in locis insignia testantur.

XX

De assaltibus. De salvis conductionibus.

De meretricibus ejiciendis.

Quod Johannes Rex Francie fuit verus captivus Edwardi

Tercii.

This mistake is peculiar to one manuscript, viz. BM.

MS. Cotton^ Neroy С. 31; another copy, prepared

by a scribe named Baddesworth in the year 1456, Brit.

Mus. Add. MS. 30946, which was later reproduced by

several copyists,2 avoids this error. There is also a

striking dissimilarity between the introductions in

these two versions. The Baddesworth version reads

thus:

Et quia de pertinentibus ad officium militare, prout in

diversis actibus bellicis in Francia et alibi asseris diversa

me vidisse, et visa in libellum redigi, tuoque desiderio

postulas exhiberi, presenciam igitur tuam precedat mens

iste rudis libellus, qui ex quattuor constat partibus

ordinatus.

In quarum parte prima tractatus de coloribus in armis,

et eorum nobilitate ac differencia : in secunda vero parte

tractatur de regulis et de signis, tarn vivis quam mortuis,

per quos signa in armis et armorum colores clarissime

discemuntur: in tercia namque parte tractatur de

animalibus et de avibus in armis portatis et eorum

proprietatibus : et in quarta parte tractatur de milicia

et eorum nobilitate. Quern quidem libellum ab initio sic

baptizo, volens quod in posterum vocetur, Libellus de

Officio Militari.

Bysshe, following the Nero version, gives the

following introduction:

In prima namque parte tractatur de milicia & nobilitate:

in secunda vero parte de bellis & actibus exercitus in

eisdem. Tercia autem pars ponit nobilitatem colorum in

xThis is the Robert Cotton MS. referred to by Bysshe.

’British Museum Harley MS. 6106 is an imperfect copy of Baddesworth.

Harley MS. 6149 contains only the section De Coloribus. Harley MS. 3504

is also a copy of Baddesworth.

xxi

armis depictorum. Et in quarta ponuntur regule, per

quas colores Armorum & ipsa Arma clarissime discernun-

tur. Quern quidem libellum ab inicio sic baptizo, volens

quod in pos terum vocetur Libellus de Militari Officio.

Thus not only are the contents of Baddesworth’s

copy presented in a different order from that of Nero,

C. 3, but the four books are differently styled.

Baddesworth MS. Nero MS.

Book i. De Coloribus. De milicia et nobilitate.

2. De regulis et signis in De bellis et actibus

armis portatis. exercitus.

3. De animalibus et avibus. De nobilitate colorum.

4. De milicia et nobilitate. De regulis et signis.

The arrangement of the material in the Baddesworth

version is more convincing than that in the Nero copy.

E.g. the scheme adopted by Bysshe in the fourth book

(following the Nero copy) is as follows:

De diversis signis in armis depictis.

De leone.

De regibus Anglie.

De Henrico II. Statuta Henrici quinti tempore guerre.

De ecclesiis .

De meretricibus ejiciendis.

Quod Johannes rex Francie fuit verus Captivus Edwardi

tercii.

De leopardo.

De ariete, agno, apro, aranea, ape, bove, botrace, camelo,

tigride, urso, vulpe, unicoma.

De aquila, accipitre, alieto, arpia, ardea upupa.

De dracone.

De delphinio, de lucio.

The lion and the leopard are taken out of the

alphabetically arranged list of animals, and the

inclusion of the arms of the kings of Britain between

the description of the lion and the leopard is strange,

since the reader has not yet been initiated into the

secret of describing arms.

xxii

The Baddesworth copy maintains a more logical

order:

De leone.

Brutus leonem in armis portavit.

Arma regum Britannie.

Quod Ricardus secundus leones non leopardos portavit.

De leopardo.

De aquila. (Ut leo velut rex, ita aquila velut regina . . .)

Imperatores Romani aquilam portaverunt.

De mustela.

Dux Britannie Minoris portat mustelam.

De perdice.

Scutifer quidam perdices portat.

De delphino.

Dolphinus delphinum portat.

Then follow in strictly alphabetical order the names

of animals, birds, and fishes borne in arms.1

Thus in the Baddesworth copy arms which are

ensigns of dignity have been removed from the others.

The lions, themselves an important charge, were

associated with the kings of England: less important

were leopards and they were attributed to the

English kings: the eagle was the most important of

birds and was associated with imperial dignity: the

Duke of Brittany bore the ermine, and the Dauphin

the dolphin. This treatment is reminiscent of that of

Honord Bonet2 who draws the attention of his reader

JNote the order in the Welsh version of the tractatus (p. 20). The

treatment of the arms of the kings of Britain has there been rightly postponed

until the end. See also note on p. 119.

lL’Arbre des Batailles d'Honore Bonet, publie par Ernest Nys (1883).

See also A. R. Wagner, Heralds and Heraldry (Oxford, 1939), p. 124.

Car il nya qui sent faites et ordonees pour lestat dez dignitez. Si comme

est le seignal de 1’aigle le quel est deputes pour la dignite impeiral, la fleur

de lis pour 1’ostel de France, le leopart pour Angleterre et aussi de tons

aultres dignitez plus petites. Si comme Г ermine pour le Due de Bretaine,

la crois d’argent pour le Conte de Savoie. . . .

Et telles armes purement homme du monde ne doit porter ne mettre en

son hostel ne en sa ville, se non cellui qui est en celle dignite seigneur

principal. Et se auscuns faisoit le contraire il en seroit punis.

xxiii

to the importance of arms which were adopted as

ensigns of dignities, such as the eagle, the fleur-de-lis,

the leopard, the ermine, etc., and maintains that no

man whatever should set up these arms except the

chief lord in that dignity, and that anyone who trans-

gressed that law would be punished.

Equally instructive is the treatment of the falcon

in the two versions. In the Nero copy the falcon is

included in its alphabetical order, but in the Baddes-

worth version it is found in the chapter dealing with

labels borne in arms (De Lingulis sive Labellis}.

Johannes de Bado Aureo could not have been

Nicholas Upton.

It is quite impossible to accept Bysshe’s assumption

that De Bado was Upton, if only on the ground that

Queen Anne had died before Upton was born. Moule,1

rejecting Bysshe’s theory, wrongly quoted De Bado as

De Padoy thus providing a name easily translated into

English, and presenting to students of heraldry a

character named John Guildford. Planche2 speaks of

him as presumed to be one John of Guildford, and who

acknowledges his indebtedness to his master Franciscus

de Foveis, or Franciscus (Francois) des Fossees.3

xThoma8 Moule, Bibliotheca Heraldica Magnae Britanniae (1822), p. 142.

The earliest reference to the name De Vado Aureo known to me is in Stowe

MS. 668, folio ib. Here we find in a late seventeenth century hand the

following :

Traite sur le blazon par lohan de Vado Aureo (Guildeford) et Francois

des Fossees, dedie a Dame Anne, Reine (de Richard 2) d’Angleterre.

The actual treatise, however (folio 52b), in a ? sixteenth century hand,

reads thus: Cy commence le traitie de maistre Jehan de bado aureo auec

ffrancisque des fossees.

'Pursuivant of Arms (1852), pp. 13, 14.

’Sir George Sitwell calls him Francis de Foveis, or Foea (The Ancestor,

No. 1, April, 1902, p. 85). He also accepts John Guildford as the equivalent

of De Bado.

xxiv

FIG. 1

De Badoy then, was not Upton, nor was he neces-

sarily Guildford: and yet this elusive personage was

sufficiently important in the reign of Richard II to be

singled out as a competent writer on heraldry.1 Many

copies of his essay were made from time to time, and

when he himself set to work to prepare a corrected

version of a youthful effort he expressed regret that

he could not recall and burn the earlier copies. It is

not unnatural therefore to assume that the second

De Bado tract found its way into the Upton work,

the De Studio Military and that there it lost its

identity. It is quite possible that the Tractatus

de Armis edited by Bysshe was De 'Bado’s hrst

eftort^ and. that another was wrongly incorpora-

ted in the Upton work. The version which is

preserved in Add. MS. 28791 is fuller than that

printed by Bysshe, but not as full as that included in

Upton. We therefore cannot now distinguish finally

the first and second efforts: nor can we tell what

changes, if any, were made when the second tract

found its way into the De Studio.

The Welsh Tractate.

There is also a Welsh version of the De Bado trac-

tate,2 and its study will throw light on the riddle of the

authorship. The oldest copy of this Welsh treatise

belongs to the Jesus College Collection.3 Sir Thomas

^uoniam de armis multociens in clipeis depictis singula discernere

inveniatur difficile, ad instanciam igitur quarundam personarum, et

specialiter Domine Anne, quondam Regine Anglie, hunc libellum compilavi

(Bysshe, p. 1).

’The Latin version in Add. MS. 28791 closely resembles the Welsh

version, and is certainly a later effort. This version has been reproduced

on pp. 144-212.

’Jesus College MS. 6. See Historical MSS. Commission Reports on

Welsh MSS., Vol. II, p. 37. Unfortunately both the beginning and the

end of the treatise are wanting.

XXV

Wiliems, a learned cleric and lexicographer, refers to a

version of this treatise which he had seen in the White

Book of Hergert! Unfortunately this book was lost

by fire in 1840.2 Wiliems does not mention when this

treatise was copied into the White Booky but he main-

tains that the White Book itself was written many years

before his day—at least a hundred and thirty-two

years before. Thus the tractate might have been

written as early as 1462.3 We cannot therefore from

manuscript evidence discover the date of the composi-

tion of the original work. Nor have we much infor-

mation about the author of this Welsh treatise, for it is

in one manuscript only that we have any mention of

xLlyfr Gwyn Hergest.

*In Stowe MS. 669, folio 17, there is a note, written, according to

O’Connor (Bibliotheca MS. Stowensis, Vol. II, p. 537), in the hand of Charles

Williams Wynne, stating that the work “is a transcript of part of the

White Book of Hergest, a folio MS. on vellum, containing a large collection

of Welsh poetry, heraldry, and history, compiled in the reigns of Henry VI

and Edward IV by Lewis Glyn Cothi, who himself was a Welsh poet and

served under the Earl of Pembroke, to whom and to his brother many of

his poems are addressed. The original was in the Wynnstay collection and

was unfortunately destroyed by fire when in the hands of Mackinley the

binder in 18(40).” It is not clear whether the writer of the heraldic treatise

was the author or the copyist; but we must, of course, assume that the

time of writing the White Book is the latest date to be assigned to its

composition.

3See British Museum Add. MSS. 31055, 126: Ac velly у teruyna у

Beibl, sef Crynnodeb talvyrh or hen Beibl yn amgyphret yn dalgrwnn

у prif istoriae or unrhyw. Ac a scriuennwyt alhan or hen Ihyver G(wynn) о

H(ergest) oedh wedy r argraphu yn dec ar vemrwn er ys lhawer о vlynydh-

oedh, cant. 32. mlynedh or lheiaf. . . .

(Thus ends the Bible, which is a concise precis of the Bible, containing

the chief narratives of the same briefly stated, and copied from the White

Book of Hergest, itself written in a fair hand on membrane many years ago,

at least one hundred and thirty-two years ago.)

Thomas Wiliems here refers to the general composition of the White Book.

In Peniarth MS. 229, p. 217, we have a list of the works presumably as they

appeared in the original work, and if we can assume that the several works

were entered in chronological order, we can also assume 1462 to be the

approximate date of copying the heraldic work, since it immediately follows

the Welsh Bible.

XXVI

him by name as Sidn Trevor,1 and in this instance we

have to rely on the accuracy of the copyist’s testimony,

unless additional supporting evidence is forthcoming

from other quarters.

It is singularly unfortunate that the opening and

closing pages of the Jesus College MS. are wanting.

If, however, we can accept the testimony of Cardiff

MS. 50, we must search for a writer named Sidn Trevor

who flourished some time before 1462, and who was

sufficiently well versed in heraldic matters to write

such a work. Three persons appear as possible

claimants for the honour, and their claims have already

been the subject of some discussion.

(1) Sion Trevor Hen2 of Bryncunallt (oi.? 1493, ?4).

(2) Sidn Trevor of Wigginton, grandson of (1).

(3) Bishop John Trevor, also known as leuan Trevor, the

second bishop of St. Asaph of that name (pb. 1410).

Professor Ifor Williams put forward a case for the

consideration of the first claimant when he rejected

Bishop Trevor as the author of a Welsh Life of

St. Martin and of this Welsh heraldic treatise.3 A close

study of these two books and of Professor Williams’

theories may therefore profitably occupy our attention.

Buchedd Sant Marthin (The Life of St, Martin).

From Mostyn MS. 88 we learn that a John Trevor

wrote a Welsh Life of St. Martin.4 This is a close

1Llyfr yw hwn a elwir yn iaith Gymraeg Llyfr Dysgread Arfau, a Sidn

Trevor a’i troes o’r Llading a’r Ffrangeg yn Gymraeg, a Hoell ap Syr Mathe

a’i hysgrifennodd, oedran Krist mil a ffumkant ac un a thrigaint. Cardiff

MS. 50. (See also p. 3.)

’Sidn Trevor Hen = John Trevor Senior.

’See Bulletin of Board of Celtic Studies, Vol. IV, 1929.

4Mostyn MS. 88. John Trevor a droes у vuchedd honn or llading yn

gymraec a Guttun Owain ai hysgrifennodd pan oedd oed Krist Mil СССС

LXXXVIII о vlynyddoedd yn amser Hari Seithved, nid amgen у drydedd

vlwyddyn о goronedigaeth yr un Hari. [Continued on page xxviii

xxvii

translation of a mediaeval Vita consisting of selections

from Sulpicius Severus’ Vita Sancti Martini, and from

his Epistulae and Dialogi, and from the Historia Regum

Francorum of Gregory of Tours. The author of The

Antiquities of Shropshire attributed this work to Sidn

Trevor Hen:1 Professor Williams rightly noted that

the parish of St. Martin (Llanfarthin), near Oswestry,

was close to the home of this Sidn Trevor. It is not

enough, however, to rely on the unsupported testimony

of the author of The Antiquities* or on the fact that

Trevor lived near Llanfarthin. Furthermore, there

are serious difficulties in the way of accepting this

assumption.

i. The writer of the Welsh Life was clearly a Latin

scholar, yet no such scholarship has been attributed to

Sion Trevor Hen by Gutun Owain, or by any of his

contemporaries.

2. Latin scholarship was not so common at this time

among the laity in Wales as to warrant its being passed

unnoticed by contemporary poets. Even Gutun Owain,

who was sufficiently interested in grammatical studies to

copy a Welsh version of a simplified Donatus, displayed a

complete ignorance of Latin.

Professor Williams also put forward Sidn Trevor

Continued from page xxvii]

(John Trevor translated this Life from Latin into Welsh, and Gutun

Owain copied it in the year 1488, in the reign of Henry VII, in the third

year of his reign.)

According to Meyrick (see Dwnn’s Heraldic Visitations, II, p. 328),

Sidn Trevor Hen died in 1494 (?). John Griffith {Ped., p. 254) and Lloyd

{Powys Fadog, IV, pp. 78, 86) put the year of his death as 1493. The

Visitations of Shropshire (II, p. 465) record his death as having taken place

in 1486-7. (See Bulletin of Celtic Studies, Vol. I, 1929, p. 41 ; cf. also

Peniarth MS. 127. p. 15.)

aT. Farmer Dukes, 1844, The Antiquities of Shropshire (Eddowes,

Shrewsbury). The reference to Sidn Trevor reads thus : “a.d. 1488, John

Trevor, a gentleman of an estate in this parish, translated the Life of

St. Martin out of Latin into Welsh” (p. 316).

xxviii

Hen’s grandson as a possible claimant.1 He is Sidn

Trevor of Wigginton. “But I cannot,” says Professor

Williams, “in spite of all that has been noted above,2

maintain that the question has been settled regarding

the two Sidn Trevors, the grandfather and the grand-

son, until we have place and opportunity to deal with

the genealogies in more detail, and to determine how

long Gutun Owain lived.” Williams had discovered

a poem written by one Morys ap Howel ap Tudur, in

which it was recorded that Sidn Trevor о Wigynt (of

Wigginton) was a man of the wisdom of Solomon, one

who knew how to blazon arms, who was learned in the

Chronicle and the Bible, and who had a perfect know-

ledge of all the arts.3

Such a formidable list of accomplishments deserves

the closest attention, for a scholar thus endowed might

well have essayed to translate ipto Welsh selections

from Severus and Gregory, and he might have written

a Welsh book on heraldry. But there is an insur-

mountable difficulty in our chronology: this Sidn

Trevor could not possibly have written the Llyfr Arfau^

a copy of which appeared in the White Book of Hergest,

Ч.е. ’Sidn Trevor of Wigginton.

20nd ni fedraf, er у cwbl a nodwyd uchod, honni fod у cwestiwn wedi

ei setlo rhwng у ddau Sion Trevor, у taid a’r wyr, nes cael gofod a chyfle

i drafod yr achau yn fanylach, a phenderfynu hyd oes Gutun Owain.

Bulletin of Celtic Studies, V, i, p. 44.

3synwyr sydd sonier j sion

sel(y)f a fryd absalon.

kornici a wyr kryno i gyd

ir bobl hyf ar beibyl hyvyd.

a dysgrivio dysg reiol

arveu’n iaith ar a vv yn ol.

pa le i nodi planedav

nas gwyr bron yscwi(e)r brav

perffaith yw seithiaith sion

xxix

It is hardly likely that he was born before 1440: and

there is no special reason for attributing to him the

Buchedd Sant Mar thin, a transcript of which was made

in 1488.

Sidn Trevor of Wiggin ton was the grandson of Sidn

Trevor Hen, who died according to one authority as

early as i486, but according to others as late as 1494.

Assuming that he was 70 years old when he died, he

would have been born somewhere around the year

1416.1 If we allow only twenty years between the

births of Sidn Trevor Hen and his son and grandson,

then the grandson was born somewhere about the

year 1456, and would be no more than 6 years old in

1462, which is a fair estimate of the date of writing

the Llyfr Arfau into the White Book.

Sidn Trevor of Wigginton might well have inter-

ested himself in heraldry, for in his day this study had

acquired a distinct popularity.2 But that he had

studied heraldry is not sufficient evidence: that he

could not have written the Llyfr Arfau is obvious.

There remains the third claimant in the person of

leuan, or John Trevor, Bishop of St. Asaph. Chevalier

1 According to Peniarth MS. 127, p. 1$, Sidn Trevor Hen died on

Friday, December 6, 1493. “Oed Crist pan vu varw John Trevor ap

Edward ap Dd. 1493, Duw Gwener, у vi*1 dydd о vis Racvyr.”

In this calculation the earliest date has been considered. Even if the

later date 1493-4 were accepted, it would not be possible that the grandson

wrote the heraldic work.

2Lewis Glyn Cothi had copied out the Llyfr Arfau into the White Book,

He himself was interested in matters heraldic, and frequently used heraldic

terms in his poems (see p. xlix). Gutun Owain, too, had undoubtedly

learned much heraldry during his period of training as a bard, and like

other bards of his day he copied out heraldic tracts and genealogical

references. Most of the Welsh poets of the sixteenth century were interested

in heraldry.

XXX

Lloyd1 notes that there were two bishops of St. Asaph

who belonged to the very well known family of Trevors,

namely leuan ap Llywelyn ab leuaf ab Adda ab Awr

of Trevor, and leuan ab lerwerth ddu ab Ednyfed

Gam of Pengwern, or, to trace his descent through

his mother, leuan ab Angharad daughter and co-heiress

of Adda Goch2 ab leuaf ab Adda ab Awr.

leuaf ab Adda ab Awr

___________________I___________________________

I I I I I I

Dafydd Hywel Llywelyn leuaf leuan Adda Goch

_____________________I I

III________________________________________________________I .

leuan Gwenhwyfar Angharad=lerwerth ddu Gwenllian

(Bishop of = Dafydd ab |

St. Asaph) | Ednyfed Gam leuan II

| (Bishop of

Edward St. Asaph)

Sion Trevor Hen

Life of Bishop Trevor.

From this table it is seen that the second Bishop

leuan was nephew to the first bishop and himself uncle

to Si6n Trevor Hen. Of his date, place of birth,

and early life, no facts are known. Nor is it known

where he received his education; but his training for

the Church must have been long extended, for he was

a Doctor of both Civil and Canon Laws. He actually

comes to notice first in 13 8 6 as precentor and prebendary

of Wells.3 These offices he seems to have held until

13934 although he was absent from this country during

XJ. Y. W. Lloyd, Tbe History of. . . Powys Fadog . . IV, p. 135.

2Per bend sinister ermine and ermines, lion rampant or, bordure

gobonny argent and gules pellaty counterchanged. See illustration

XXVI c.

^Calendar of entries in tbe Papal Registers relating to Great Britain and

Ireland {Calendar of State Papers^ IV).

4John Le Neve, Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae . . I, p. 170.

xxxi

the years 1390—5. In November, 1389, he received

4‘Provision of a canonry at St. Davids with reservation

of a prebend, notwithstanding that he had a canonry

and prebend at Wells, together with the precentorship,

and at St. Asaph, and has this day received provision

of canonries with expectations of prebends in Llan-

ddewibrevi and Abergwili in the diocese of St. Davids.”

Trevor was a person of some importance as early as

1389, for in that year he with two others had been

entrusted with the temporalities of the see of Hereford.1

On March 2, 1390, Trevor was elected by the

Chapter of the Cathedral Church of St. Asaph to the

vacant see of that diocese, and he received royal sanction

to go to Rome to secure the Papal confirmation of his

election.2 The vacancy had occurred in December,

1389. When he arrived in Rome he found that one

Alexander Bache had already been appointed by the

Pope: Trevor thereupon decided to stay in Rome as

“Auditor of Causes of the Apostolic See, and Papal

Chaplain.” He seems to have made good use of his

stay at Rome, for in November, 1391, he received

the emoluments of the parish of Meifod and its chapels

valued at 300 marks, as well as the dignity of a canonry

at Lincoln; and in November of the following year he

obtained permission to resign or exchange his

benefices.3

In August, 1394, the see of St. Asaph again became

vacant by the death of the bishop, and again Trevor

was elected by the chapter. This time he was able to

obtain the confirmation of his election by Pope

1 Calendar of tbe Fine Rolls {Calendar of State Papers), July 9.

zRotuli Parliamentorum, Ш, p. 274.

3Calendar of. . . Papal Registers, IV.

xxxii

Boniface IX. On April 9 of the following year he

obtained the royal licence to accept, and he received

the temporalities of the see on July 6 and the spirituali-

ties on October 15.1 His consecration took place at

Rome in October. On becoming bishop he gave up

his canonries and prebends of St. Davids and Llan-

ddewi Brefi, and, presumably, his precentorship and

the prebend at Wells.2 Before leaving Rome he had

secured a faculty to grant dispensation “to six persons

of his kindred to hold benefices with cure, even

of an elective dignity .”3

Almost immediately on his return to England he

took a prominent part in political affairs; and he was

sent by Richard II on a mission to Scotland in the

company of John of Gaunt and other nobles. This

journey is the theme of lolo Goch’s cywydd to Bishop

Trevor.4 His name is also included with those of

Edward Duke of Albemarle and John Earl of Salisbury

as the Commissarii chosen in 1398 to treat for pax

perpetua with Scotland, and on April 5, 1399, he was

chosen with those same two noblemen and others to

punish the Scots for violation of treaties.5

In 1399 Richard embarked upon his ill-starred

expedition against the Irish, and he found himself

away from his kingdom when Bolingbroke after landing

at Ravenspur raised forces against the Crown. Richard

landed at Pembroke and hurried to North Wales, where

he had hoped to find the Earl of Salisbury at the head

of the men of Cheshire and loyal Welshmen to oppose

'Rotuli Parliamentorum.

Calendar of. . . Papal Registers . . November, 1394.

^Calendar of. . . Papal Registers^ 12 Kai. Mai.

4H. Lewis, T. Williams, and I. Williams, Cywyddau lolo Gocb ac ErailL

'•Rotuli Scotiae.

xxxiii

the invader. It is not known whether Trevor went

to Ireland with Richard: we know that he deserted his

king in North Wales, and that on August 16, 1399,

he was appointed chamberlain of Chester, Flint, and

North Wales by Bolingbroke. This appointment was

later confirmed by Bolingbroke as king on November 1.

Apparently Trevor accompanied Bolingbroke and

Richard on the journey from Chester to London, for

at Lichfield on August 24, “in the presence of Henry

duke of Lancaster” he received the royal seals from the

king.

He was a member of the parliamentary commission

which pronounced the sentence of deposition on the

king. This sentence was even possibly composed by

him, and it was read by him in full parliament.1 This

same parliament was angrily rebuked by Trevor for

praying the king to refrain from lavish grants and

especially from giving grants which were supplied by

the Crown, maintaining that liberal grants added to

the dignity of kings. He was sent to Spain in 1400

as ambassador to announce Henry’s accession to the

throne of England, and in the same year he accom-

panied the English army to Scotland. It appears that

the men of Chester and the Welsh followers of Owain

Glyn Dwr were annoyed with Trevor for the part which

he had played in Richard’s dethronement, and, while

he was in Spain or on the expedition to Scotland, his

palace and three manor houses were destroyed, and

the cathedral church itself was badly burned.2 The

parish church of Llanfarthin near Oswestry was

burned at this time. In May, 1401, by a mandate

xRotuli Parliamentorum, III, p. 424; Cbronicon Adae de Usk, p. 327.

*D. R. Thomas, The History of the Diocese of St. Asapb.

xxxiv

“in commendam,” there was granted to him by the

Pope, for life or while bishop of St. Asaph, “the church

of Meifod with its annexed churches of Welshpool

and Cegidfa in his diocese, the value not to exceed

300 marks ... he being unable to maintain his episcopal

state with the fruits of his church of St. Asaph, which

has recently suffered very great loss on account of

wars and tribulations in those parts.” In June he

was granted the income of the church of Mold.1 *

During the next few years Trevor’s loyalty to

Henry IV was severely tested. Himself a Welshman,

he realised that the policy of parliament in the quarrel

between Glyn Dwr and Lord Grey of Ruthin was

unjustifiable. Consequently he earnestly warned par-

liament not to drive the Welshmen to revolt by treating

them harshly; but he was told that parliament was not

at all concerned with the bare-legged rascals (de scurris

nudipedibus se non curare)? Trevor was appointed the

Prince of Wales’s deputy in 1402, and on April 22

the Prince made him his lieutenant for Chester and

Flint. He came at the head of ten esquires and forty

archers to the king’s muster before Shrewsbury and

probably fought on the winning side at the battle of

Shrewsbury, July 23, 1403.3

Whatever were Trevor’s motives, he joined Glyn

Dwr probably late in 1404, and from 1405 until his

death in 1410 we find him working wholeheartedly in

the Welsh cause. Adam of Usk notes that he crossed

over to France twice to raise forces for Glyn Dwr.

1 Calendar of. . . Papal Registers,

*Eulogium Historiarum sive Temporis (Rolls Series, HI, p. 119).

•J. E. Lloyd, Owen Glendower (Oxford, 1931), pp. 123-5 > sub

Trevor, John.

XXXV

Consequently his goods were seized by the Crown

and his see declared vacant, though his successor was

not appointed until 1410. In 1405 he was sent by

Glyn Dwr to co-operate with Northumberland, and,

after the failure of the rising in the north, Trevor and

Northumberland fled to Scotland.1 As late as 1409

he was known as episcopus praetensus2 He died in

1410 on a visit to France and was buried in the

infirmary chapel of the Abbey of St. Victor.3 Adam

of Usk’s statement that Trevor died “trans Tiberym”

is untrustworthy, for Adam was himself an exile at the

time, and he quotes no authority for his statement.

In the British Museum there is a list of books which

once belonged to a John Trevor, bishop of St. Asaph;4

but these almost certainly belonged to Bishop Trevor I,

who held the see from 1346 to 1357.

Trevor was a scholar, a warlike prelate, and a keen

man of affairs. He was interested in heraldic matters,

and we find that on November 6, 1389, a commission

was granted to the Earl of Salisbury and four others

including Trevor to examine a cause brought before

the court of chivalry.5 There is clearly a case there-

fore for considering Bishop Trevor as a possible

author of the Welsh Llyfr Arfau. His claim to be

the writer of the Buchedd Sant Marthin is also attrac-

tive, because we read in The Antiquities of Shropshire

that “the Bishop of St. Asaph had a seat in this parish

(i.e. St. Martin’s) in the right of the church, which

^ordun, Scoticbronicon, II, p. 441 ; Liber Pluscar densis, ed. by

F. J. H. Skene (Historians of Scotland, Vols. VII, X), I, p. 348.

‘Thomas Rymer, Foedera, VIII, p. 588.

’Browne Willis, A Survey of the Cathedral Cburch of St. Asapb; Le Neve,

Fasti Ecclesiae Anglicanae, I, p. 70.

♦Add MS. 25459, folio 291 ; vide D.N.B., sub Trevor.

^Calendar of Patent Rolls (Calendar of State Papers'). See also p. xliv.

xxxvi

was burned down by Owain Glyn Dwr in Henry IV’s

time, and never since repaired by any of the prelates

of that see.” Here is a real motive for writing the

Life of the patron saint of a church that was so closely

attached to the Bishopric of St. Asaph.

The De Bado Tractate and the Welsh Llyfr

Arfau.

No account of the Welsh heraldic work will be

complete without a comparison with the De Bado

treatise, which it resembles very closely.1 Yet, if the

Welsh text is considered as merely a translation of the

Latin text, serious difficulties immediately arise,

because Trevor, far from acknowledging any indebted-

ness to the De Bado treatise, actually claims an origin-

ality for his own effort. He maintains that he con-

sulted, not one single Latin work, but several Latin

and French ones. “I have essayed,” says he, “to

translate from Latin and French into Welsh, portions

of the works of various authors, (who have written) on

this subject, so as to stimulate Welsh readers who may

be unskilled in other languages, to pay attention to

this science of arms, and to make enquiries lest it be

entirely lost.”2 This clearly implies that the Welsh

work is not a translation of the Latin treatise, which—

a significant fact—was written by a contemporary.

Was Bishop John Trevor no other than lohannes de

Bado Aureo himself ?

Especially of the version found in British Museum Add. MS. 28791.

Compare the Welsh text or the English translation with the Latin on pages

I to 94, and pages 144 to 212.

*Mi a ymkenais droi о Ladin a Ffrangec mewn iaith Gymraec gyfraim

0 waith amravaelion awduriaid or gelvyddyt honn, megis i deffro hynny

ddarlleodrion Kymraec ar ni bwynt ddysgedic mewn ieithoedd eraill, i

ymwrando ac i ymwybod ac i ymgeisio am gelvyddyt arveu. . . .

xxxvii

Certain events in the life of Trevor suggest that this

theory can be maintained. He was certainly well

known to Queen Anne, and just before he left England

for Rome in 1390 he had taken part in an important

heraldic case. During the years 1390—5 he was away

from this country: if he had contemplated writing the

tractate while he was at Wells, and did not complete

the task until his return to England, we have a clear

explanation of the reference, in the introduction of the

work, to the death of Queen Anne. The treatise is

more than a description of arms: it contains interesting

references to works on natural history, and it reflects

wide knowledge of medieval law. All these specula-

tions however would have more weight if the name

John Trevor could be satisfactorily equated with the

Latin name lohannes de Bado Aureo. John and leuan

are obviously the same as lohannes*! the difficulty

appears in the interpretation of De Bado.

In a poem attributed to lolo Goch a contemporary

of Bishop Trevor we find the bishop referred to as

hil Awr (of the stock of Awr).2 As son of Angharad

who was daughter and coheiress of Adda Goch, he

^here appears to be no reference to the bishop as Sion and

Professor Lewis maintains that Sidn and leuan are not interchangeable.

“Sylwer mai leuan yw enw’r Esgob, nid Sion, fel у dywaid Mr. Evan J.

Jones, Mediaeval Heraldry, 12. Ni chymysgid у ddau enw, er eu bod ill

dau’n dod 0 lohannes, leuan yn uniongyrchol i’r Gymraeg, a Sidn drwy’r

Saesneg, mwy nag у cymysgir Evan a John heddiw.” (See Cywyddau lolo

Goch ac Eraill, second edition, note on p. 353.) Yet Syr Rhys in a poem

addressed to Guto’r Glyn spoke of Yr Abad Sion and leuan Abad in the

same poem, and Tudur Aled in the same one poem spoke of leuan ap Deicws

as Sion.

2H. Lewis, T. Roberts, and I. Williams, Cywyddau lolo Goch ac Eraill,

p. 82.

xxxviii

could claim the dignity of hilAwr and trace his descent

from Awr the Lord of Trevor.1

The first suggestion that occurs is that Ab Adda ab

Awr might suggest to a whimsical mind the name

De Bado Aureo: at least Awr and Aureus present a

similarity in sound. Du Cange doubtfully suggests

that badus=amphorae species: thus, if we write the

possible equivalent tun for badus^ and remember that

names ending in -ton were frequently represented by

the rebus tuny we have another possible explanation

for De Bado Aureo.2, The Welsh word for town is tref\

and thus, since town can be represented by the rebus

tun^ we can also equate De Tref-or with De Bado Aureo.

Bishop Trevor, who could speak French fluently and

was a Latin scholar, must have been aware of the

punning possibilities of his Welsh name.

Fox-Davies makes it clear that the rebus never

had an heraldic status.3 “The rebus in its nature

is a different thing from a badge, and may best be

described as a pictorial signature, the most frequent

^ruffudd Hiraethog, in Peniarth MS. 126, p. 37, shows the importance

of the Trevor family in the following entry : “Jhon Trevor (i.e. John Trevor

Hen) ap Edward ap Dafydd a Gwenhwyfar v[erch] Adda Goch ap leva ap

Adda ap Awr . ap Tudur Trevor.

2badus=species amphorae=M.E. tonne. Cf. M.E. toun. Tref or=

tref aur=oppidum aureum: oppidum (town) recalls badus=tun. If we can

accept the possibility that Trevor may be represented by a rebus, a golden

tun, then we have another to add to an already interesting list of rebuses.

E.g. Bishop Beckyngton (Bishop of Bath and Wells), a later contemporary

of Trevor (1390-1465). Fire beacon planted in a tun, together with T

(in stained glass window at Wells Cathedral and Lincoln College, Oxford).

Abbot Robert Kirkton. A church and pastoral staff on a tun (at Peter-

borough Cathedral).

Thomas Conyston, abbot of Cirencester. Comb and a tun (Gloucester

Cathedral).

Hugh Ashton (d. 1522). Ash tree issuing out of a tun (St. John’s,

Cambridge).

Bishop Langton (1500). A musical note issuing from a tun (Westminster

Chantry).

•A. C. Fox-Davies, Complete Guide to Heraldry, 1925, p. 455.

XXXIX

occasion of its use being in architectural surroundings,

where it was constantly introduced as a pun upon

some name which it was desired to perpetuate. The

best-known and perhaps the most typical and charac-

teristic rebus is that of Islip, the builder of part of

Westminster Abbey. Rebuses abound on

all our ancient buildings, and their use has lately come

very prominently into favour in connection with the

many allusive book-plates, the design of which

originates in some play upon the name.”

Rebuses and canting arms were not at all strange

to the writers on heraldry: a later contemporary of

Trevor, Bishop Thomas Beckyngton, had, as we have

seen, a rebus design, and this, by an interesting

coincidence, can still be seen at Wells Cathedral.

The Welsh poet Simwnt Vychan (pb. 1606) used the

Welsh word twnn to signify a cask, and he thus

describes the arms of a Croxton family in Cheshire:

Kroxtwnn о swydd Garlleon. Mae yn dwyn arian, ac

аг у ffess о ssabl dau twnn о aur, Rwng tair kroes groessoc

ssangedic or ail, dwy uwch у ffess ac un is i law.1

(Croxton of the county of Chester. He bears argent,

and in the fess sable two tuns or, between three cross

crosslets fitchy of the second, two above and one below.)1

Canting arms, and similarly, rebuses, are not always

immediately obvious, and unless early forms of the

names pictorially represented are appreciated, the

allusive connection may be missed. The De Rupe

family of Pembroke, for instance, bore as their arms

an allusion, not to a rock, but to a roach, and they bore

gules, 3 roaches naiant in pale argent?

Cardiff MS. 4. 265, folio 141 v. See fig. la. Papworth gives /«5 az.

So also Smith, The Vale Royall of England, pub. by Daniel King, 1656,

p. 103.

2Note also illustration XXI d.

xl

It might be urged against this theory that before we

can equate De Bado Aureo with Trevor we must trans-

late from Latin into English and from English into

Welsh. Some little time later than Trevor’s day one

William Middleton was known by the Welsh transla-

tion Gwilym Canoldref: he at least would have exper-

ienced no difficulty in picturing his Welsh name

allusively by means of a tun rebus. In the year 1571

a printer named John Awdely used as his printer’s mark

a very complicated and intriguing cryptogram, the

appreciation of which demanded some knowledge of

Hebrew and not a little ingenuity in solving puzzles.

His mark was “three interlocked crescents with the

word 4V in the centre, and between the horns of the

crescents the word ‘’‘РЗ appearing three times.

This delightful puzzle has been treated in The

Bulletin of Celtic Studies.1 Here is a summary of

the findings. If we write down the words and

we have the beginning of a phrase found in Psalm

Ixxii, 7. The next word in the psalm is ГГР (moon),

nr = until the moon be no more.

Now, forgetting for the moment that we are dealing

with Hebrew words we can read the letters as

AdBeli or AdVeli or OdVeli (Audely). Again, if we

substitute for the Hebrew word Ya-re-ach (moon)

1 Bulletin of Celtic Studies, Vol. Ill, May, 1927, pp. 294 ff.

xli

found in the psalm, another word meaning moon,

Isvanah, we shall have Le (Ь) = by (author-

ship}, thus making

Levanah = By levan, By leuan, By John.

Thus the cryptic representation can be deciphered as

By John Awdely.

When once it has been admitted that punning

devices are favoured, there are no limits to the vagaries

of the imagination. Thus there seems no reasonable

objection to the reading of lohannes de Bado Aureo as

John TrevorЛ

The Occasion of the Writing of the Tractatus.

In the year 1385 an English army under the king in

person invaded Scotland,2 and among the banners

displayed on this occasion were those of Sir Richard

Scrope, first Lord Scrope of Bolton, and of Sir Robert

Grosvenor, a knight of the Palatinate. Their arms

were azure, a bend or.3 A dispute followed, and

the matter was referred to the Court of Chivalry which

consisted normally of the Constable and Marshal of

England (or their lieutenants), and nobles, knights,

and learned clerks. Among these on this occasion

1E. Griffin Stokes, in his edition of Epistolae Obscurorum Virorum

(London), 1909, quotes an interesting example of the use of translation for

providing a pen name. “Johann Jager, afterwards known to the world of

letters as Crotus Rubianus (or Rubeanus) was born at Dornheim in 1480.

His Latinised name at first was lohannes Venator. Crotus Rubianus is

‘decidedly enigmatical until we remember that Dornheim is thorn-home, and

Crotus appears in the De Re Rustica of Columella as a synonym of Sagittarius.’

A far-fetched cognomen was in those days an indication of sound

scholarship.” See introduction, p. lx.

2See Chancery Miscellaneous Rolls, bundle 10, No. 2, edited by Sir N.

Harris Nicolas, 1832 (The Scrope and Grosvenor Controversy, privately

printed, 1832). See also “The Grosvenor Myth” by W. H. B. Bird in

The Ancestor (April, 1902, No. 1, pp. 166 ff.).

ad’azure ove une bende d’ore. For note on his arms, see p. xliv, n.

xlii

were the Duke of York and the Earl of Salisbury.

A tremendous array of evidence was produced on either

side and some of the evidence was claimed to have

dated from the time of King Arthur.1

Scrope brought forward the more numerous and

more distinguished array, leading off* with John of

Gaunt, Roy du Chastell de Lyon, due de Lancastre.

Other deponents on his side were Le Counte de Derby,

afterwards Henry IV, Sir John Holland, the Earl of

Northumberland, Sir Henry de Percy, and Geoffrey

Chaucer. Grosvenor’s witnesses were drawn chiefly

from the two counties palatine, but among them were

several men of rank, including Owain Glyn Dwr.

In 1389 the Duke of Gloucester, as Constable, gave

his sentence in favour of Scrope, but granted the

defendant Grosvenor permission to bear the same arms

with a bordure argent.2 The decision was interpreted

by Grosvenor as a defeat, and he appealed to the king

as Fountain of Honour, who promptly appointed

commissioners to rehear the case; and barely a year

afterwards he gave the sentence in person, confirming

the Scrope title to the arms with costs against the

defendant, and annulling the Constable’s grant of the

differenced coat on the ground that a plain bordure

was not sufficient difference for a stranger in blood.3

The king assigned to Grosvenor new arms, azure a

^ee note 1 on p. xliv.

*lez ditz armes ove un playn bordure d’argent.

8Nous considerantz q’ tiel bordure n’est difference sufficeant en

armes entre deux estraunges & d’un roialme, mes taunt toulement entre

cousyn & cousyn privez de sane. . . .

xliii

garb or, which his descendants have since borne

unchallenged.1

This case naturally attracted the attention of all

the nobility of the land,2 and Trevor, who had not

yet left for Rome, almost certainly found a special

interest in it. It is noteworthy that both parties were

well known in the Welsh border, and in the evidence

much matter concerning early British history was

examined. It was also natural for other families to

make enquiries into their rights to their arms, and in

the Calendar of Patent Rolls (Richard II), under the

date November, 1389, we read of a commission

summoned to enquire into the rights of two families in

Devon to a certain coat of arms. Trevor, then

precentor at Wells, was one of the judges.3

English Treatise on Arms.

There is also a short English treatise on arms which

belongs to the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century.

Its contents are disappointing. The British Museum

has two copies, B.M. Add. MS. 34648 and Hari. MS.

6097, and there is another copy in the Bodleian

Library, Bodl. Land. Misc. 733.

х5угг Robart Grofenor. Mae yn dwyn assur, ysgub wenith о aur

(MS. D. 141). See XXIX c.

Mention was made among the depositions of a third claimant of these

arms, Thomas Carminowe, an esquire of Cornwall, who carried his claim

back far beyond the Conquest to the time of King Arthur.

2An earlier case considered by Commissioners appointed by the

Constable Thomas of Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, known as the Love!

v. Morley case, is described by Mr. Wagner in his book Heralds and Heraldry,

PP- 21-3.

3The Commission was granted to the Earl of Salisbury, Lewis de Clifford

knight, Richard Sturry knight, Master Roger Page, Master John Trevaur,

doctor of laws, to bear and determine the appeal of John Dynham knight of

Devon in a cause in tbe court of chivalry before John Lakenhytb knight and

John Peyto knight supplying the places of Constable and Marshal of England,

in which cause William Asthorp knight was plantiff and tbe said John who now

petitions tbe king defendant.

xliv

The catalogue of the British Museum, after quoting

the opening words of Add. MS. 34648, says: “The

translator’s name suggests that of John ‘de Bado

Aureo,’ but the tract is quite distinct in matter from

the latter’s Tractatus de Armis (also grounded on

Franciscus de Foveis), which was printed by

Sir Edward Bysshe in 1654. Daliaway {Science of

Heraldry, 1793, p. 151) mentions John Dade1 in con-

nection with a translation from the Latin of Franciscus

de Foveis; but whether as the actual translator, or as

the scribe of a particular MS., is uncertain.”2

Three possibilities suggest themselves. The first

is that John Vade, as we must now call him, was the

actual writer of this tract and that he acknowledged

his debt to Franciscus de Foveis, as did the author of

the Tractatus de Armis. The second possibility is that

the name Vade came into being through the influence

of the name De Vado. And there is the third possi-

bility that even the word Vade is incorrect: we have

no original to decide the issue. Did Trevor write

this English version ? Was it written by someone

who was influenced by the Tractatus ?3

гРог the opening words see p. 213. The writer calls himself John.

The obvious errors in the manuscript make it clear that we have not the

original copy.

2The date of this MS. is given as fifteenth century ; but the original

tract might be contemporary with that of De Bado. The late Professor

F. P. Barnard, while not rejecting the Trevor theory put forward here,

believed that De Vado might have been used for De Bado. He had

examined the Bodleian MS., and, writing to me in 1931, he said: “The

author of this tractate is given in the Bodleian Catalogue as John Dade :

on looking at the MS. I found it was Г, i.e. a V read erroneously as Z>, so

we have there Vado. I got Nicholson, the then Librarian, to correct it.”

This MS. has been deposited in a place of safety for the duration of the war,

and therefore cannot now be consulted.

•For the text, based upon the two B.M. manuscripts, see pp. 213-220.

xlv

Other Works attributed to Bishop Trevor.

Bishop Trevor seems to have preserved an anonymity

with regard to other compositions. An examination

of these works will throw further light upon the life

of Trevor; but since the whole problem has been dealt

with in fair detail elsewhere,1 a brief summary must

here suffice.

To the TLulogium (Historiarum sive Temp oris)2, edited

by F. S. Haydon in the Rolls Series, there are appended

two Continuationes^ the former treating the history of

England from the year 1364 till the year 1413. The

editor had failed to trace the author of this Continuation

but he noticed that it had been written by a reliable

historian who wrote good Latin. A careful study of

the work discloses that certain portions were not written

by the author of the main part, that certain remarkable

coincidences appear in the events recorded in the work

and in the life of Trevor himself, and that some of the

events noted were of peculiar interest to Welshmen

and to Trevor in particular.3

If Trevor was the author of this Continuatio we have

at our disposal an account of the Welsh risings against

Henry IV written by an eyewitness who had been

'Vide Speculum, Journal of Mediaeval Studies, XII, p. 197, and XV,

pp. 464 et seq.

*Eulogium (Historiarum sive Temporis), Cbronicon ab Orbe Condito

usque ad annum Domini M.CCC.LXVI, a Monacbo quodam Malmesburiensi

exaratum. Accedunt Continuationes duae, quarum una ad annum M.CCCC.

XIII, altera ad annum M.CCCC.XC perducta est. Rolls Series (1863),

No. 9.