Текст

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS

of QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

by Eugene Kuzmin

SIRIUS ACADEMIC PRESS

2013

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY

IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

(1651 -1689)

Eugene Kuzmin

SIRIUS ACADEMIC

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

SIRIUS ACADEMIC PRESS

28203 SW 110th Ave

Wilsonville, Oregon 97070 USA

siriusacademic.com

© Copyright by Eugene Kuzmin (2013)

ISBN: 978-1-940964-01-0

Cover design by Sasha Naumov

All rights reserved. No part of this work may be copied or reproduced

in any way without the expression written permission of the author(s)

and the publisher.

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

Contents

1. Introduction

1. Problem, Methodology and Composition of the Work 4

2. Kuhlmann's Brief Biography 12

3. History of Research 15

4. Alchemy and Poetry 31

2. Kuhlmann and Alchemy

1. Early Works: Epistemology and First Acquaintance

with Alchemy (until 1674) 49

2. Formulation of the Main Scientific Principles (1674) 77

3. Search for Recognition (1674 - 1689) 121

3. Alchemical Symbols

1. Tincture 150

2. Color 172

3. Micro-and Macrocosm 186

4. Three Principles 213

5. Rose and Lily 245

4. Alchemical Operations and Processes

1. An Alchemical Journey 281

2. Chemical Marriage, or Conjunction 294

3. Opus Magnum 335

5. Conclusion 369

Appendix 1. Kuhlmann's Works 375

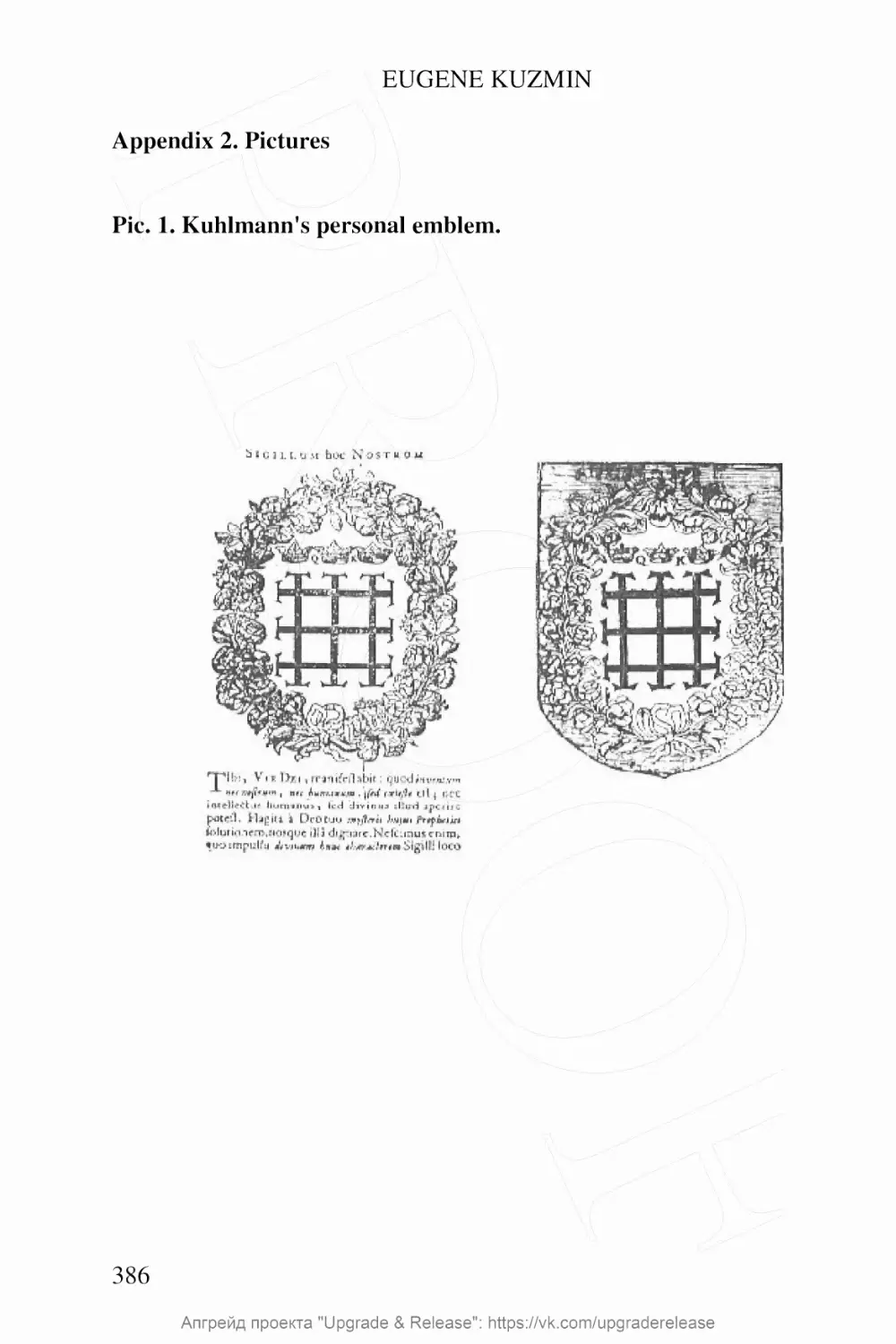

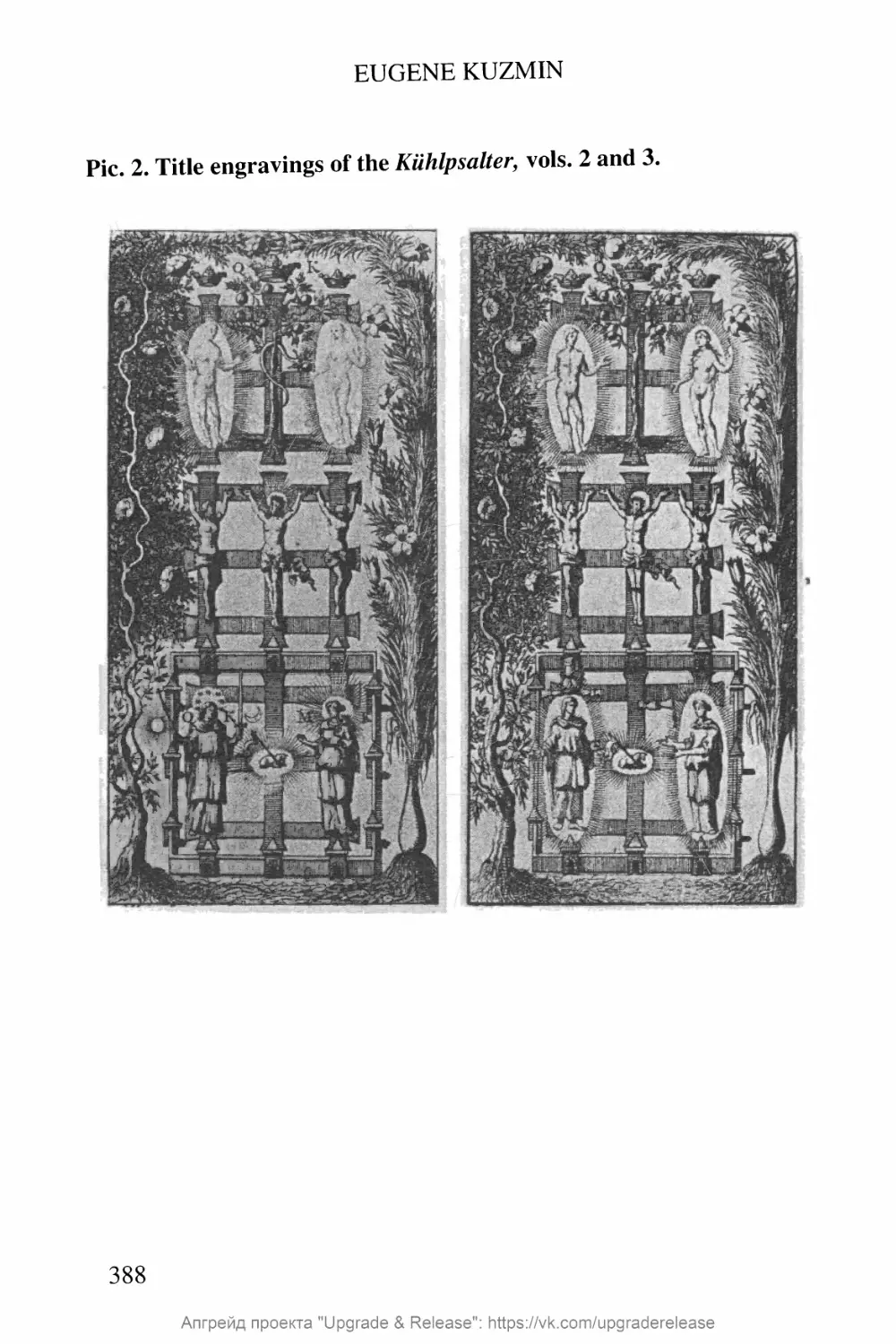

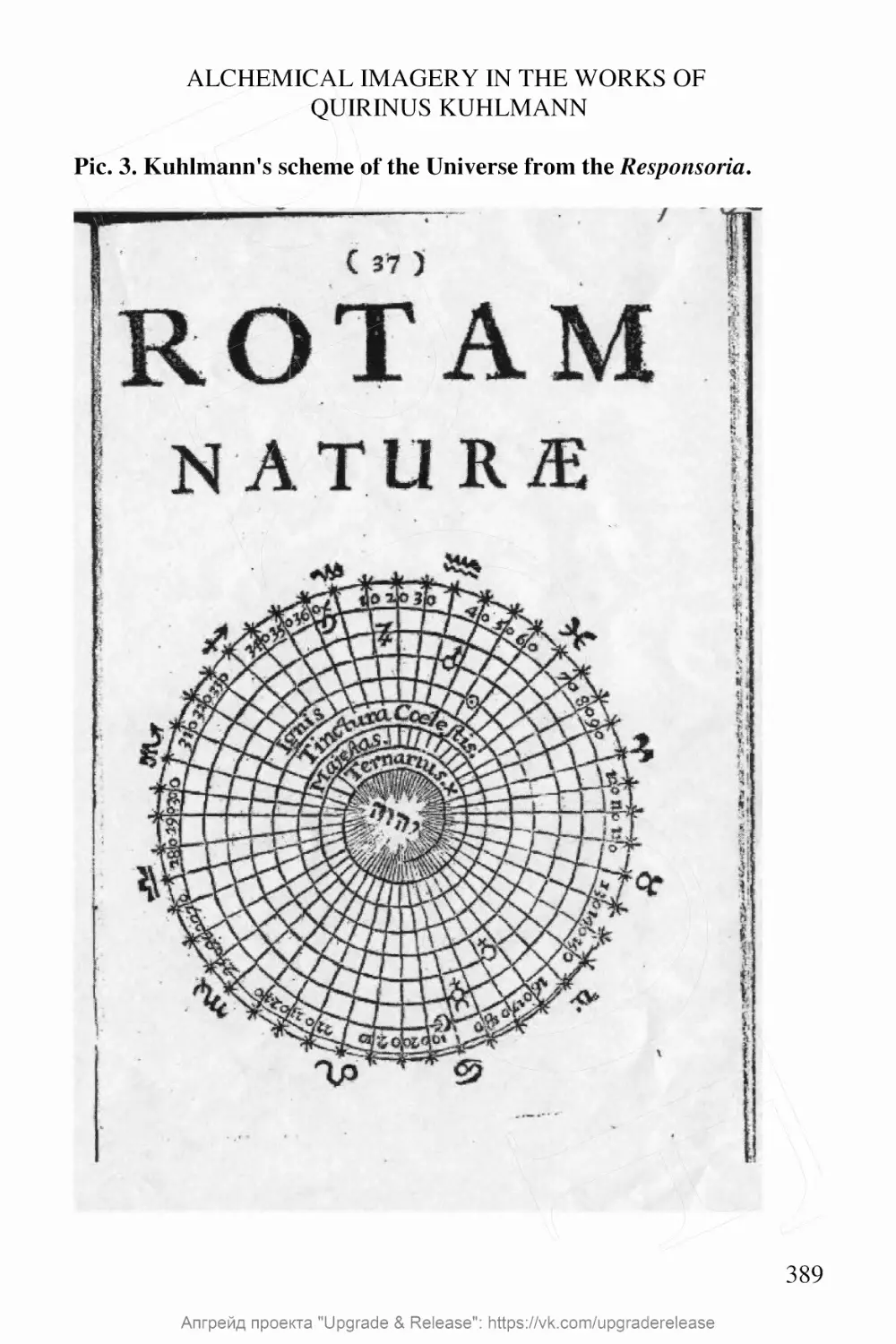

Appendix 2. Pictures 386

Bibliography 395

3

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

1. Introduction

1.1 Problem, Methodology and Composition of the Work

The widely known chiliast thinker and German baroque poet Quirinus

Kuhlmann (1651-1689) was interested in alchemy. His knowledge of the

subject was based both on books and on personal acquaintance with many

alchemists - some famous, some little known. Kuhlmann freely discussed

his ideas with these adepts, and their theories may well have had a

considerable influence on him. Similarly, Kuhlmann may have inspired

certain alchemists, and thus traces a dialogue between literature and science

during the Scientific Revolution1—that period which saw the emergence of

modern scientific nomenclature—can be found in Kuhlmann's writings.

This work was originally planned as an attempt to solve the widely

acknowledged problem found in studies of the Silesian baroque poet,

Quirinus Kuhlmann - alchemy's impact on his works. Though the problem

has been frequently noted, no special study has been made of it, and

references to it have never been seriously explored. That Kuhlmann was

interested in alchemy is generally accepted as a given, but without particular

verification: though it is self-evident through Kuhlmann's references to

known alchemists, the character and intensity of alchemy's influence on him

remains unclear.

The research could have been completed without difficulty, since

Kuhlmann's biography and works have been thoroughly studied (see section

1.3) and the main facts about him and his books are easily accessible. A

large body of works exists on the impact of alchemy on various poets (see

section 1.4), and it would not be difficult to borrow a scheme from any of

1 The Scientific Revolution is a period roughly between 1500 and 1800, when new

ideas in various sciences led to a rejection of doctrines that had prevailed from Ancient

Greece through the Middle Ages, and laid the foundations of modern science. The term

was coined in: Alexander Koyre, Etudes galileennes (Paris: Hermann, 1939). The

literature on the subject is vast. For general introduction see: Rupert A. Hall, The

Scientific Revolution, 1500-1800: The Formation of the Modern Scientific Attitude, 2nd

ed. (Boston: Longmans, 1962); Thomas Samuel Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific-

Revolutions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962); Richard S. Westfall, The

Construction of Modern Science: Mechanisms and Mechanics (New York: Wiley,

1971); Steven Shapin, The Scientific Revolution (Chicago: The University of Chicago

Press, 1996).

4

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

those studies and extrapolate it onto our own inquiry. However, during the

textual study and analysis it became clear that such a methodology creates a

serious problem. There are two widespread methods for studying the impact

of alchemy on literature, and they are illustrated by many examples in

section 1.4. One can search for references to alchemical books and

quotations from them. If a certain author declares that he has borrowed an

idea from an alchemical text or unambiguously cites an alchemical text,

then the impact of alchemy on that person cannot be questioned. Sometimes

an author's general attitude to alchemy is disclosed in his explanations; if he

insists that the transmutation of metals is impossible, it is clearly established

that he does not believe in transmutation. The negative side of this approach

lies in its plain informative character. When studying a considerable number

of authors, one can decide on the extent to which alchemical ideas were

disseminated, or on attitudes toward alchemy in general, but it cannot

explain the distinctive influence that alchemy had in an author's works. It

remains unclear why, and to what extent, those authors engaged in alchemy

in the first place, or what ideas they adapted from it. The results of such

studies are thus limited and contribute hardly anything to understanding the

context of alchemy's impact.

There is a second method, that involves the analysis of particular ideas,

theories, and symbols, and in fact it is the only possible way to clarify the

character and reasons for borrowing from alchemy. In this case, though, we

must clearly know and formulate what alchemy entails and what are the

implications of its distinctive language, images, symbols, and theories. It is

necessary to have lucid ideas about its essence, and what distinguishes it

from other disciplines, and this leads to an artificial construction of the

abstract ideal of alchemy.

It is impossible to offer a simple explanation of the essence of alchemy,

for its adepts did not draw up a unified common conception of its subject,

methods, and tasks. The contemporary education system stipulates the

subjects and methods of study. Academic institutions have assembled a set

of researches enabling a never-ending dialogue between researchers on the

subjects deemed appropriate for academic study,2 but the situation with

alchemy was completely different. Right from the beginning, it was

excluded from the circle of official, commonly accepted spheres of

2 Thomas Samuel Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

5

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

knowledge,3 and its tie with academic disciplines was doubted. During the

seventeenth century, the situation started to change, with the increasing

popularity of alchemy that generated an incredible flood of books on

alchemy and burgeoning interest in it.4 There were many attempts to make

alchemy an established discipline, open to debate by the scientific

community, and to incorporate it in the educational system.5 Alchemy

3 William R. Newman, “Technology and Alchemical Debate in the Late Middle Ages,”

Isis 80 (1989): 423-45. Also in his: Promethean Ambition: Alchemy and the Quest to

Perfect Natures (Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2004), 34¬

114.

4 This popularity is widely known and noted in various works on alchemy. The topic

was discussed in detail, for instance in R. Hirsch, "Printing and the Diffusion of

Alchemical and Chemical Knowledge," Chymia 3 (1950): 115-41; Allan G. Debus, The

Chemical Philosophy: Paracelsian Science and Medicine in the Sixteenth and

Seventeenth Centuries, 2 vols., (New York: Science History Publications, 1977), 1:448¬

55; Bruce T. Moran, Distilling Knowledge: Alchemy, Chemistry, and the Scientific

Revolution (Cambridge, Mass and London: Harvard University Press, 2005), 46-66;

Also in the beginning of: Allen G. Debus, "Paracelsianism and the Diffusion of the

Chemical Philosophy in Early Modern Europe," in Paracelsus: The Man and his

Reputation. His Ideas and their Transformation, ed. Peter Grell Ole (Leiden, Boston,

Koln: Brill, 1998), 226-44.

5 Allen G. Debus, Science and Education in the Seventeenth Century: The Webster-

Ward Debate (London: Macdonald; New York: American Elsevier, 1970); his,

"Chemistry and the Universities in the Seventeenth Century," Academiae Analecta:

Klasse der Wetenschappen 48 (1986): 13-33; his, "Chemists, Physicians, and Changing

Perspectives on the Scientific Revolution," Isis 89, no. 1 (March 1998): 66-81; Owen

Hannaway, ’’Early University Courses in Chemistry” (PhD diss., The University Of

Glasgow, 1965); his, The Chemists and the World: The Didactic Origins of Chemistry

(Baltimore, Md.: Johns Hopkins Press, 1975); Jose Mana Lopez Pinero’s introduction

to: Lloren$ Co^ar, El "Dialogus" (1589) del Paracelsista Lloreng Canary la cdtedra de

medicamentos quimicos de la Universidad de Valencia (1591) (Valencia: Catedra e

Institute de Historia de la Medicina, 1977), 9-25; Jose Mana Lopez Pinero, "Paracelsus

and his Work in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Spain," Clio Medica 8 (1973): 113¬

41; Bruce T. Moran, The Alchemical Word of the German Court: Occult Philosophy

and Chemical Medicine in the Circle of Moritz of Hessen (1572-1632) (Stuttgart: Franz

Steiner Verlag, 1991); idem, Chemical Pharmacy Enters the University: Johannes

Hartmann and the Didactic Care of Chymiatria in the Early Seventeenth Century

(Madison: American Institute of the History of Pharmacy, 1991). On the importance of

a convincing theory for the acceptance of the knowledge as science (based on the

example of the healers in the Renaissance) see John Henry, “Doctors and Healers:

Popular Culture and the Medical Profession,” in Science, Culture and Popular Belief in

Renaissance Europe, ed. Stephen Pumfrey, Paolo L. Rossi and Maurice Slawinski, 191¬

6

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

evolved from an amorphous marginal sphere of knowledge into a widely

popular, and thus even more shapeless field, with extensive discussions on

alchemy that created various opinions about it. Ultimately chemistry

became an official science, while alchemy returned to its former

marginality, at best.

Another problem is the vagueness and instability of alchemical

terminology, a well-known problem, noted in most works on alchemy.* 6

Alchemical texts were intentionally written in an unclear style that

permitted numerous interpretations;7 nothing is stated clearly and with

certainty, and thus there is no well established and commonly accepted

nomenclature. Any alchemist could produce new symbols, and so every

text, event, and phenomenon could be interpreted as an alchemical sign.

Maurice P. Crosland has summarized that situation,8 and shows how the

same terminology could simultaneously be alchemical and non-alchemical.

He also states that modem chemistry begins from a certain standardization

of alchemy's language and methodology.

Such a situation makes a simple comparison between ideas impossible.

If there are two ideas or symbols, one of which appears in an alchemical

book and the other in a poem, it cannot prove alchemy's impact; the poem

might also have inspired an alchemist who granted it an alchemical

interpretation. A poet and an alchemist could well have had a third non-

alchemical source, and yet we can speak of alchemy as a definite subject: if

alchemical books were written, published, bought, and explained by

alchemical lexicons, and if there were people who called themselves

221 (Manchester and New York: Manchester University Press, 1991); Fritz Krafft, 'Die

Arznei kommt vom Herrn, und der Apotheker bereitet sie'. Biblische Rechtfertigung der

Apothekerkunst im Protestantismus. Apotheken-Auslucht im Lemgo und Pharmak-

Theologie, Quellen und Studien zur Geschichte der Pharmazie 76 (Stuttgart, 1999), 59¬

74; idem, "Arzneien 'umb sonst und on gelt' aus Christi Himmelsapotheke,"

Pharmazeutische Zeitung 146(2001): 10-17.

6 For interesting philosophical insight into the problem see: Raimond Reiter, "Die

'Dunkelheit' der Sprache der Alchemisten," Muttersprache: Zeitschrift. Zur Pflege und

Erforschund der deutschen Sprache 97, no. 5-6 (1987): 323-6. However, this article is

too abstract and theoretical for our historical study.

7 For the bibliography of the modern attitudes to alchemical symbolism see: H. J.

Sheppard, “A survey of alchemical and hermetic symbolism,” Ambix 8 (1960): 35-41.

8 Maurice P. Crosland, Historical Studies in the Language of Chemistry (Cambridge,

Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1962); his “Changes in Chemical Concepts and

Language in the Seventeenth Century," Science in Context 9 (1996): 225-40.

7

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

alchemists, this should be a criterion for defining alchemy as a subject and,

thus, for alchemical impact. We can start defining alchemy's impact by

listing the main principles of our study of its influence on literature. First of

all, we need to show that Kuhlmann had certain clearly alchemical sources,

to prove that the poet had read alchemical books or was in contact with

alchemists, and to identify remarks and passages where alchemy is

unmistakably referred to.

Every symbol or term has to be briefly discussed, from a historical

perspective, that may illuminate the relationship between the symbol or

term and alchemical tradition. Alchemical lexicons are particularly

important in this context, since they show real correlations between the

subject and the history of terms and symbols. Though the definite source of

an alchemical symbol or term may be difficult to trace, one can identify

possible influences by examining the works that the writer read. Finally, we

should investigate if various separate symbols and terms can be considered

part of a specific alchemical theory. Alchemy should not be regarded as a

chaotic set of terms and symbols, but as a science or pseudo-science, which

provides its adepts with promises of acquiring specific theoretical or

practical systematic knowledge.

Quirinus Kuhlmann is a suitable figure for gaining an understanding of

the interrelation between alchemy and literature. The question of alchemy's

impact on him is a very old unresolved problem (see section 1.3). On the

whole his contemporaries regarded him as an adept, and this is noted by

most of his early biographers, of whom the most important are Gottfried

Arnold (1666-1714) and Johann Christoph Adelung (1732-1806). That

reputation has strong foundations, and it is enough to note among his works

the manifesto De Magnalibus Naturae (1682), written for adepts of

alchemy; even so, the actual impact of alchemy on Kuhlmann has never

been specially studied. Walter Dietze, who authored the best-known

research on Kuhlmann, questioned the importance of alchemy on

Kuhlmann's worldview, though he did not enlarge on the topic.

This work thus has two main tasks; the first is to address the unsolved

question regarding alchemy's impact on Quirinus Kuhlmann, and the second

is to construct a new, dedicated methodology for studying the impact of

alchemy on literature - a mission likely to pioneer research on the

interrelationship between literature and science in the seventeenth century.

The first task, however, totally overwhelms the second one, since the extent

of the work and the focus on one personality rules out a comprehensive and

abstract discussion. This work accordingly focuses on Kuhlmann, without

8

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

highlighting the ties between alchemy and literature, and with no extensive

discussion on other personalities. The new methodology is not only a tool

for this specific study but, as shown in section 1.4, it may be useful for other

studies of how alchemy affected literature.

There are four parts to this study. The first part is an introduction into

the entire work, and begins with an explanation of the methodology and

general principles, as well as offering information on the its goals, structure,

and arguments (1.1). The second section of the first part provides general

information on Kuhlmann's biography (1.2); although our theme is

alchemical imagery in his work, rather than his life, this section looks at his

personality. The main biographic facts are given as briefly as possible,

simply to introduce Kuhlmann to the reader. Section 1.3 contains a brief

history of Kuhlmann's scholarship and its main trends, and also explains the

importance of studying alchemical imagery in his works. The final section

of the first part (1.4) introduces readers to the problematic of the

interrelations between alchemy and literature.

The need for seeking a new methodology is well grounded, and an essay

follows on the history of research into alchemy's impact on literature; the

essay is neither comprehensive nor complete. We cite a broad range of well-

known and representative articles, that reflect the chief trends and problems

in studies of the alchemy-literature relationship. Several very accurate

studies exist concerning the impact of alchemy on the literature of

Romanticism,9 but we have excluded them from our outline. Around 1800,

attitudes toward alchemy radically changed, alchemy was no longer a focus

for debate in the scientific community, and so those works research a reality

radically different from that of the seventeenth century. As well as

providing a bibliographical guide, the essay's principal task is to prepare the

field for discussing the literature-alchemy relationship, and to set out the

principles and strategies for our study. It points out some important

philosophical and methodological problems entailed in such research.

The actual research starts in the second part, that concerns the

development of Kuhlmann's knowledge of alchemy, and discusses the books

9 Dietrich von Engelhardt, Hegel und die Chemie: Studie zur Philosophic und

Wissenschaft der Natur urn 1800 (Wiesbaden: Pressler, 1976); Georg Schwedt, Goethe

als Chemiker (Berlin: Springer, 1998); Michel Chaouli, The Laboratory of Poetry:

Chemistry and Poetics in the Work of Friedrich Schlegel (Baltimore and London: The

John Hopkins University Press, 2002).

9

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

he read and the alchemists with whom he communicated, though it is of

course vital not only to produce a list of such books and persons, but also to

establish how Kuhlmann responded to them. Much attention is paid to the

development and evolution of Kuhlmann's attitude to scientific knowledge

and his epistemological assumptions. As far as possible, the material is

organized chronologically, though occasionally compliance with that strict

order tends to render the text less readable, since Kuhlmann repeatedly

returns to the same topic, so there are exceptions to chronological order. The

section's main purpose is to describe the process of Kuhlmann's

development throughout his life.

This part has three sections - a division generated by the logic of

Kuhlmann's inner progression (1.2). The turning point in his development is

1674, when he reacted to Jakob Bohme's (1575-1624) works, which deeply

impressed him. From that point, Kuhlmann is especially known as a

Behmenist (i.e. follower of Bohme), as his Neubegeisterter Bohme brought

him wide fame. Hence, this year splits our narrative into three sections:

before 1674, that was a formative stage when Kuhlmann tries to find a main

direction for his thinking; in 1674 he formulates leading principles for his

basic theories; and after that year, Kuhlmann applies his newly developed

teaching. That division also changes the study's main character. Before

1675, Kuhlmann's sources are mostly from books, but from that year

onwards he creates personal contacts with many alchemists; at that period,

he acquired his knowledge principally from oral sources. This part is far

from comprehensive, and shows only Kuhlmann's alchemical inspirations

without addressing his main inspirations. General studies about Kuhlmann,

particularly Walter Dietze's (1.3) monograph, are worth consulting for

information on his most important sources. We deliberately refrained from

presenting detailed notions regarding the complex relationship between

people and ideas, and the section's overarching aim is to show Kuhlmann's

development in general, rather than his place in intellectual history.

The work's third part discusses Kuhlmann's alchemical terms and

symbols, and chronological order is generally avoided here; only

sometimes, in cases of considerable changes in the symbol's usage over

time, it is specifically noted. The discussion is mostly analytical, with a

focus on the symbols' essence, not on the details of their development

through Kuhlmann's lifetime. The set of alchemical symbols is not

complete here, for we chose the terms and symbols most important for

understanding Kuhlmann's works. There are three sections in this part: it

starts with a brief explanation of the history of a symbol/term and its

10

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

connection with alchemy; next, the usage, meaning, and role of the

symbol/term in Kuhlmann's works are explored; finally, succinct attention

is given to the connection of the term/symbol in its particular context to

alchemy, and the probable source of Kuhlmann's use of it.

The final part addresses alchemical theories and processes in

Kuhlmann's works, and attempts to show the role of separate symbols and

ideas in their interrelations within a certain system, with developed

alchemical theories. The analysis of Kuhlmann's works is not organized, for

the most part, in chronological order. There is a brief reference to the

history of a certain theory, a discussion of the idea's meaning in Kuhlmann's

works, and some remarks on Kuhlmann's possible sources. There are three

sections in this part. The first concerns Kuhlmann's journey and an

alchemical interpretation of its nature (4.1), showing the diversity of the

problem: there is nothing chemical in a journey itself, but it can be

explained as a chemical act. This section is intended to emphasize the main

methodological problems when studying alchemy's impact on literature. The

second part highlights "alchemical marriage" (4.2), a pivotal theme in Carl

Gustav Jung's study of alchemy, and that has often dominated modem

studies on alchemical symbolism. The final topic addresses the main

alchemical process - Opus Magnum (4.3). It unites various alchemical ideas

into a single theory and one narrative, and addresses the main features of

Kuhlmann's actual use of alchemical imagery.

The study has two appendices. The first provides a bibliography of

Kuhlmann's works, and explains the character of the sources and their

chronological order, as well as describing the availability of his writings.

There is no edition of Kuhlmann's complete works, and some of his books

are extremely rare and so there the bibliographical data are highly diverse.

Important references to Kuhlmann's works in the main text of the work offer

general explanations on the character of the sources, and they are described

systematically in a special section (Appendix 1). The second appendix

consists of pictures - illustrations mentioned in the work. The conclusion at

the end of the entire work explains some important ideas established by this

study. While researching material on Kuhlmann, different versions of the

names of the same person were encountered, however only one was used

throughout to maintain consistency.

The title of this study highlights Imagery in the Works of Quirinus

Kuhlmann, and its neutrality cannot delude the reader by implying

substantial explanations. Alchemy as such cannot have an impact. The

11

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

subjects of alchemy and its nomenclature are too flexible, and it is a broad

sphere of knowledge with unclear boundaries, and thus the word "imagery"

lets us adopt a broad view of the problem, without terminological

restrictions.

Since this work presents a new methodology and deals with a

considerable quantity of primary sources, it was deemed preferable to avoid

discussion, when possible, on modern technical terms, and thus to focus our

attention on the main trajectory of the research and be flexible in our

responses to the complex content of the sources.

1.2. Kuhlmann's Brief Biography

Quirinus Kuhlmann was born in Breslau (Wroclaw) on February 25, 1651 to

a Lutheran family. Very little is known about his sister, Eleonore Rosina.

His father's profession is under question, since different testimonies

maintain that he was a merchant, or a harness maker. He evidently died

while traveling, only three years after Quirinus Kuhlmann was born. Until

the future poet's twelfth birthday, the boy suffered from a speech

impediment, for which he was often mocked: possibly, his extensive reading

compensated for his lack of social interaction. He began to study in the open

city library of Breslau, and from 1661 he attended the Ratgymnasium bei

Maria Magdalena, where he studied for nine years at the municipality's

expense. His first works were published in that period, and he became

renowned at a very early age. Kuhlmann also gained influential friends

during that period. He was sponsored by different patrons throughout his

entire life. Kuhlmann had very complex relations with some of them, and

financial support strongly depended on his patrons' attitude to his ideas and

deeds, as well as his personal interactions with them, making his wellbeing

unstable.

In September 1670, Kuhlmann set off to study jurisprudence at the

University of Jena, which had the reputation at that time of a university with

low academic standards, though it was the university where Lutheran youth

from Silesia embarked on higher studies. In Jena, Kuhlmann wrote and

published his works, and tried to attract the attention of famous and noble

people. The range of his correspondence and works, and the fact that he

published some impressive anthologies, shows the absence of a clear

direction of interest, or immersion in something definite. Although

Kuhlmann received attention and praise in Jena, he was apparently

12

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

dissatisfied with the university and left in 1673 for Leiden, then one

Europe's most famous universities. His decision may have been spurred by

his inner search for a vocation. Kuhlmann's publications while in Jena show

his negligible interest in studies of jurisprudence.

Leaving Jena for Leiden marked a decisive turning-point for Kuhlmann,

and it was the year when he became acquainted with Jacob Bbhme's

writings, to which he responded excitedly. In 1674, summarizing his new

inspirations, Kuhlmann wrote his famous work, Der Neubegeisterte Bohme,

a book that introduced him into a circle of religious thinkers, particularly the

so-called enthusiasts.10 Since that work, he was usually regarded as a

Behmenist, and for the most part it is a true definition; throughout his life,

Kuhlmann repeatedly refers to Bohme as the ultimate authority. While

Kuhlmann certainly had a wide circle of acquaintances, his principal friends

and opponents are Behemists. Following his engagement in Bbhme's works,

Kuhlmann's religious search intensified. After 1674, he visited numerous

European cities where he was introduced to many famous enthusiasts and

adepts, such as Johannes Rothe, Friedrich Breckling, Johannes Gichtel,

Tanneke Denys, and Mercurius van Helmont (2.2, 2.3). Kuhlmann believed

in his prophetic mission and sought confirmation of it, a search that led him

to construct a "private mythology," as Walter Dietze calls it (1.3).

Kuhlmann gave special meaning to each of his deeds and the events in

his life, as well as his travels. Three of his journeys were especially well

planned and difficult, as a missionary in lands that Kuhlmann knew little

about. The first was a journey to Constantinople to convert the Ottoman

Sultan to Christianity; undertaken in 1678-1679, it had little success.

Kuhlmann could not meet the Sultan Mechmed IV, who in the meanwhile

had left Constantinople on a campaign against the Tsardom of Russia.

Kuhlmann did not convert the Sultan, but explained his failure as a victory,

believing that his journey would spiritually bring about the conversion of

the Turks. Second, he traveled "spiritually" to Jerusalem in 1681-1682,

10 "Enthusiast" means "inspired by God". From the book of R.A. Knox it is generally

regarded as a specific phenomenon in European history. For the introduction see R. A.

Knox, Enthusiasm: A Chapter in the History of Religion (Oxford: Oxford University

Press, 1950); Michael Heyd, "Be Sober and Reasonable:" The Critique of Enthusiasm

in the Seventeenth and Early Eighteenth Centuries (Leiden, New York, Koln: E. J.

Brill, 1995); Lawrence E. Klein and Anthony J. La Vopa, eds. Enthusiasm and

Enlightenment in Europe, 1650-1850 (San Marino, California: Huntington Library,

1998).

13

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

though he never arrived there, because of financial problems. He traveled

through France and Switzerland, seeing this journey as seeking the

conversion of the Jews, which Kuhlmann believed would occur in the future

as a result of his journey. Finally, in 1689, he moved to Russia, where he

planned to agitate the Russians to join an anti-Catholic union, together with

the Turks and Protestants. However, he was arrested and burned at the stake

as a heretic in Moscow.

Kuhlmann composed a considerable quantity of works, both poetic and

theoretic; the theoretic ones were rich in form, but monotonous in content.

Starting from 1674, Kuhlmann repeatedly insisted on his outstanding

religious mission. He arranged his arguments in the form of pamphlets,

letters, commentaries, anthologies and philosophical works - aimed to

appeal to different thinkers, and addressing different spheres of human

knowledge (see Appendix 1).

Women played a very important role in Kuhlmann's life and, as a

consequence, in his theoretical speculations too. Three women are worthy of

note: Magdalena von Lindau, Mary Gould (Kuhlmann called her Maria

Anglicana), and Esther Michaelis. Quirinus Kuhlmann cohabitated with

Magdalena von Lindau without legalizing the union from October 1675-

April 1679, and they remained in sporadic contact after 1679. This was

during his journey to the Ottoman Empire and early chiliastic career. In

1685, after a long cohabitation and many hesitations, Quirinus Kuhlmann

finally married Mary Gould, a physician and an educated woman, in

Amsterdam. It was apparently a happy marriage, but Mary died on

November 16, 1686. A year later Kuhlmann married Esther Michaelis, who

stepfather, Loth des Haes, was the publisher of some of Kuhlmann's books.

Kuhlmann's personality has some traits that, allied with the fate of his

works, might attract the attention of researchers into the history of ideas.

First, Kuhlmann was particularly known to his contemporaries for his

extravagant thoughts, deeds and, most importantly, as an adept; for instance,

he was in touch with Mercurius van Helmont, Athanasius Kircher, Albert

Otto Faber, and prominent English Behmists (2.2, 2.3). His wide range of

contacts with seventeenth-century scientists is discussed at length below.

Second, Kuhlmann had a great influence on the development of widely

known trends in thinking of his time, although that impact is not the topic of

our study and is not discussed comprehensively here. To mention a few of

such influences, nevertheless, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646-1716)

showed interest in his ideas on ars combinatoria. He certainly read at least

one of Kuhlmann's works, his published correspondence with Athanasius

14

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

Kircher (1601/2-1680). Another example is Kuhlmann's celebrated treatise

Der Neubegeisterte Bohme (1674), published before the first edition of

Opera Omnia by Jakob Bohme (1682), and might have inspired it.

Kuhlmann was noted by early Russian masons.

The theme of alchemy's influence on seventeenth-century poetry is

widely known and has already been mentioned (see also 1.4). As a poet,

religious thinker, and an adept rolled into one person, Kuhlmann is a good

subject for studying that phenomenon. He and his ideas were known among

alchemists, and in his works, all those topics are merged and quite

indivisible. And moreover Kuhlmann can be viewed as a starting-point in

the relationship between literature and science at the time of the Scientific

Revolution — a highly significant era for the rise of the modern scientific

narrative, scientific terminology, and its application.

1.3. History of Research

Walter Dietze compiled a history of scholarship before 1963 in his Quirinus

Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, as did Jonathan P. Clark in his article "Beyond

Rhyme or Reason. Fanaticism and the Transference of Interpretive

Paradigms from the Seventeenth-Century Orthodoxy to the Aesthetics of

Enlightenment." (See below). Diinnhaupt's is the most recent attempt at

producing a definitive bibliography of Kuhlmann in his

Personalbibiographien zu den Drucken des Barock, with special assistance

from J.P. Clark." Our bibliographical sketch is not completely independent

nor innovative research into that question, and is rather based considerably

on Dietze, Clark and Diinnhaupt. The main stages in the development of

historiography are repeated here, to give a clear idea of the context of our

work on Kuhlmann. It provides the reader with an understanding of the

main problems in studies of Kuhlmann; it indicates how that scholarship

developed, and helps to explain the significance of this research. We have

no intention of providing a comprehensive bibliography; only the most well

known and influential works have been chosen, those reflecting the main

direction in which Kuhlmann studies developed. We also refer to works that

11 Gerhard Diinnhaupt, Personalbibliographie zu den Drucken des Barock, (Stuttgart:

Hiersemann, 1990-1993), 4:2444-62.

15

Anrpewfl npoeirra "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

are important for our particular theme - the alchemical impact on his

writings.

Before Kuhlmann's death in 1689 and for some time thereafter, his

name and his biography were generally remembered.12 His works were

well-known and adherents of his religious teaching continued to be active

after his death (particularly Christoph Barthut), but without garnering

significant success. He was noted in various studies of the period. Some

information on his life was found in purely historic works, for instance in

those of Lucae, Kohler, and Ludwig.13 His name was also noted in general

descriptions of Silesian literature, such as in the works by Erdmann

Neumeister,14 Johann Christian Leuschener,15 Johann Sigismund John,16 and

J.G. Peuker.17 Kuhlmann was also held up as an example in religious

controversies and his fate and teaching were used, for instance, in the

polemic around Bohme between Abraham Calovius18 and Friedrich

Breckling.19 For Calovius, Kuhlmann's fate was a deleterious result of

Bohme's impact, while Breckling believed that Bohme's true teaching could

not be blamed for its interpreters' misunderstandings. Indeed, Kuhlmann is

12 Generally the bibliographical sketch on Kuhlmann is based on Walter Dietze,

Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet; Versuch einer monographischen Darstellung

von Leben und Werk, Neue Beitrage zur Literaturwissenschaft 17 (Berlin: Riitten und

Loening, 1963), 339-51.

13 Friedrich Lichtstern [Friedrich Lucae], Fiirsten- Krone Schelisische... (Frankfurt am

Main: Knoch, 1685), 103-5; Johann David Kohler, Der Shelisischen Kern-Chronicke

Anderer Theil... (Frankfurt: Buggel, 1711), 2:497-522 ; Gottfried Ludwig, Vniversal-

Historie, Von Anfang der Welt bis aufletzige Zeit... (Leipzig: Lanck, 1718), 1:600.

14 Erdmann Neumeister, Specimen Dissertationis Historico-Criticae De Poetis

germanicis hujus saeculi praecipuis.. .(n.p., 1706), 62 f. The work was reedited as De

Poetis Germanicis, by Franz Heiduk, with German translation by Gunter Merwald

(Bern: Franck, 1978). See pp. 369 f. in new edition.

15 Johann Christian Leuschner, Ad Cvnradi Silesiam togatam.... (Hirschberg: Immanuel

Kahn., 1753). no pagination.

16 Johann Sigismund John, Parnassi silesiaci sive Recensionis Poetarvm

Silesiacorvm... (Breslau: Rohrlahius, 1728), 120 f.

17 Johann Georg Peuker, Kurze biographische Nachrichten der vornehmsten

schlesischen Gelehrten die vor dem achtzehnten Jarhundert gebohren warden, nebst

einer Anzeige ihrer Schriften (Grottkau: Verlag der evangelischen Schulanstatt, 1788),

62 ff.

18 Abraham Calovius, Anti-Bohmius... (Leipzig: Christiphor Wohlfart, 1690), see

Preface and in main text pp. 118 f.

19 Friedrich Breckling, Anticalovius sive Calovius cum asseclis suis prostratus, et

Jacobus Boehmius cum aliis testibus veritatis defenses (Halle: Luppius, 1688).

16

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

most often cited as a negative example, a warning to the righteous. This

image is also found in works by August Pfeiffer,20 Samuel Schelwig,21 22 23 24

Georg Pritius, Heinrich Ludolf Benthem, ‘ Andreas Carolus, Johann

Fiedrich Corvinus,25 and Adam Rechenberg.26 A founder of Pietism, Philipp

Jacob Spener (1635-1705), also adhered to this line of reasoning; he was

very well aware of Kuhlmann's ideas and initially expressed a certain

optimism for Kuhlmann's possible recovery from deviant beliefs. However,

Spener later lost hope of such an eventuality.27

Academic interest in Kuhlmann's teaching and biography was embodied

in two dissertations written in the early eighteenth-century. Gottlieb

Liefmann defended the first of them in Wittenberg under the title

Dissertatio historica de fanaticis Silesiorum et speciatim Qvirino

Kuhlmanno in 1698; it was reissued in 1713 (second edition) and in 1733.

According to the title page of that book published in 1733, it was the fourth

edition. The dissertation may have been printed twice in the same year,

though research has not yet tried to determine the question. The second

dissertation, Dissertatio de Quirino Kuhlmanno, Fanaticorum speculo et

exemplari, was defended by Johann Christian Harenberg and published in

the second volume of Museum Historico-Philologico-Theologicum, in

Bremen, in 1732. Both dissertations lack actual information or facts, but

they are evidence that interest in Kuhlmann was unabated.

The turning point in the study of Kuhlmann's biography and

bibliography was Gottfried Arnold's Unparthayische Kirchen- und Ketzer-

20 August Pfeiffer, Antichiliasmus... (Lubeck: Bbckmann, 1691), 65 f., 69 f.; his,

Antienthusiasmus... (Lubeck: Bbckmann, 1692), 268-72.

21 Samuel Schelwig, Die Sectirische Pietisterey...(n.p., 1969), 49.

22 Georg Pritius, Moskowitischer Oder Reufiischer Kirchen-Staat... (Leipzig: Groschuff,

1698), 24-7.

23 Heinrich Ludolf Benthem, Holiindischer Kirch- und Schulen-Staat... (Frankfurt and

Leipzig: Forster, Gottschick, 1698), 2:165, 343-7.

24 Andreas Carolus, Memorabilia Ecclesiastica seculi d nato Christo... (Tubingen:

Cotta, 1699), 2:114.

25 Johann Friedrich Corvinus, Anabaptisticum et Enthusiasticum Pantheon... (n.p.,

1702).

26 Adam Rechenberg, Sumniariuni Historiae Ecclesiasticae.... (Leipzig: Klosius, 1697),

722.

27 There is a special study on the problem: Jonathan P. Clark, '"In der Hoffnung

besserer Zeiten': Philipp Jakob Spener's Reception of Quirinus Kuhlmann," Pietismus

und Neuzeit 12 (1986): 54-69.

17

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

Historie. The author collected substantial material on the Church's history

from its beginnings to his own days: he also found many basic sources for

Kuhlmann's biography and teaching.28 Arnold was the first who tried to

compile a comprehensive list of Kuhlmann's works. The book provides the

reader with substantial interesting and suggestive information, and

consequently the book Unparthayische Kirchen- und Ketzer-Historie

became a popular source for knowledge on Kuhlmann in wider circles.

Arnold supplied many well-known historians with data of genuine value,

but also provoked a bitter polemic in which Kuhlmann's name significantly

figured. In presenting both biographical and speculative data on him,

Heinrich Feustking aggressively advanced a clearly negative appraisal of

Kuhlmann as a heretic;29 as well as awarding bias, it shaped the tendency in

studies for such well-known historians as Ehregott Daniel Colberg,30 Johann

Michael Heineccius31 and Johann Georg Walch.32 In the age of the

Enlightenment, Kuhlmann continued to attract attention. His name

occasionally appeared in periodic and general works on enthusiasts,33

though there were no discoveries, suggestions, or new facts. Moreover, no

special studies were made that specifically concerned Kuhlmann himself.

The philosophical and ideological perspectives changed drastically, so that

allegations of heresy were modified to charges of foolishness.

The epic work by prominent philologist and lexicographer Johann

Christoph Adelung, Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit is notable.34 This

28 Gottfried Arnold, Unpartheyische Kirchen= und Kezer= Historie, vom Anfang des

Neuen Testaments bis auf Jahr Christi 1688..., 4 in 2 vols (Frankfurt: Thomas Frischen,

1729), 3:197-201.

29 Heinrich Feustking, Gynaeceum Haeretico Fanaticum, Oder Historie und

Beschreibung Der falschen Prophetinnen/ Qvackerinnen/ Schwarmerinnen/ und

anderen sectirischen und begeisterten Weibes-Personen/ Durch welche die Kirche

Gottes verunruhiget warden;... entgegen gesetzet denen Adeptis Godofredi Arnoldi

(Frankfurt and Leipzig: Zimmermann, 1704), 406-10.

30 Ehregott Daniel Colberg, Das Platonisch-Hermetischen Christenthum... (Leipzig;

Gleditsch, 1710), 1:322-6; 2:644 f.

31 Johann Michael Heineccius, ...Eigentliche und wahrhafftige Abbildung der alten und

neuen Griechischen Kirche... (Leipzig: Gleditsch, 1711), 30-37.

32 Johann Georg Walch, Die Historische und Theologische Einleitung in die Religions-

Streitigkeiten...vols. 4 and 5. (Jena: Meyer, 1736).

33 See also n. 10.

34 Johann Christoph Adelung, Geschichte der menschlichen Narrheit, oder

Lebensbeschreibungen beriihmter Schwarzkiinstler, Goldmacher, Teugelsbanner,

18

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

eight-volume work, printed between 1785 and 1789, contains biographies of

different religious thinkers presented from the perspective of the

Enlightenment, as fools. Kuhlmann's biography occupies almost a hundred

pages in the work's fifth volume, that is an attempt to explore the problem

from a position unmarked by previous religious discussion. As well as

analyzing previous works on the topic, Adelung tried to compile a new and

full list of Kuhlmann's publications. The Geschichte der menschlichen

Narrheit surpasses all previous works not only in quantity of information,

but also in accuracy of research. In the eighteenth century, particularly its

first part, biographic notions about Kuhlmann appeared in numerous

lexicons,35 but his name started disappearing from wider circles toward the

end of the century and mentions of Kuhlmann became exceedingly rare.

In the early nineteenth-century, interest in Kuhlmann's works and

personality started to revive,36 and a book by August Kahlert, Schlesiens

Antheil an deutscher Poesie, awakened some interest in his personality.37

Kahlert's study returned the name of Kuhlmann to general studies of

literature and history, as well as to lexicons,38 though Kuhlmann's biography

and writings were not thoroughly dealt with. The new interest in Kuhlmann

caused a shift, and the sources were gradually searched and studied. Many

years after his first study on the topic, August Kahlert devoted a special

work to Kuhlmann.39 Nevertheless, by the end of the century interest had

died away in Germany itself.

Certain references were made to Kuhlmann in scientific literature in

Russia, during the last twenty years of the nineteenth century,40 and a first

work especially devoted to him was published in 1867. It was an article by

Nikolay Savvich Tikhonravov, which addressed Kuhlmann's visit to

Zeichen- und Liniendeuter, Schwdrmer, Wahrsager und anderer philosophischer

Unholden (Leipzig, 1785-1789), 5:2-90.

35 For their list see Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 348.

36 The bibliography from the 19th century till 1963 is particularly based on Dietze,

Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 9-16.

37 August Kahlert, Schlesien Antheil an deutschen Poesie: Ein Beitrag zur

Literaturgeschichte (Breslau: A. Schulz, 1835).

38 For a list of these publications, see Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 9¬

10.

39 August Kahlert, "Der Schwarmer Quirinus Kuhlman," Deutsches Museum:

Zeitschrift fur Literatur, Kunst und ofentliches Leben 10 (1860): 316-24.

40 Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 14.

19

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

Moscow in 1689.41 Ivan Sokolov found original document relating to

Kuhlmann's trial—a manuscript that Tikhonravov had not encountered.42

All the Russian documents were carefully analyzed and published by

Dmitriy Tsvetayev in 1883.43 Tikhonravov's article remained better known,

however, and for a proposed collection of his works, Tikhonravov revised

and expanded his article that was ultimately never printed because of the

publisher's financial circumstances. The text was first translated into

German by A.F. Fechner, an evangelical pastor in Moscow, and was

published in Riga as a small book.44 Tsvetayev published a piece that

included a reference to Kuhlmann, but was lesser known than the works of

Tikhonravov; it was an article on Protestants in Russia during the reign of

Sofia (1682-1689).45 He reproduced this text, without conceptual or factual

changes, in another work on non-orthodox Christianity in Russia in the

sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.46

After Kahlert's work, the next study in Germany devoted to Kuhlmann

would appear only in 1909, an article by Bernhard Ihringer.47 The author

rejected the old widespread conception that regarded Kuhlmann’s life as a

point in the history of human foolishness. For Ihringer, the talented poet's

extravagant ideas were vestiges of his time, and thus a subject worth

studying; his publication enhanced Kuhlmann’s standing somewhat and his

name began to reappear in several general works.48 The need to publish

Kuhlmann’s works became obvious, and in 1923, Ausgewahlte Dichtungen

appeared in Hadern-Verlag.49 Seven years later, two biographical studies

41 HHKOJiaii CaBBnq TnxoHpaBOB, "Kbhphh KyjitMaH," PyccKuu eecmuuK 72, no. 11

(November 1867): 183-222, ibid. 72, no. 12 (December 1867): 560-94.

42

PiBaH Cokojiob, OmnoiaeHue npomecmaumcmBa k Poccuu 6 XVI u XVII bckox

(MocKBa, 1880),. 171 ff.

43 IjBeTaeB, "Po3biCKHoe aejio KBupmra KyjibMana, 1689 roaa 26 Man-29

OKTflOpn," HmeHun O6u{ecmBa Hcmopuu u ffpeBHOcmeii Poccuu 3(1883): 144, 149.

44 N.S. Tichonrawow, Quirinus Kuhlmann (verbrannt in Moskau den 4. Oktober 1689):

Eine Kulturhistorische Studie (Riga: N. KymmePs Buchhandlung, 1873).

45 JjMMTpm IjBeTaeB, "RpoTecTaHTCTBO b Poccmm b npaBJienne Cocj)bM," PyccKuu

eecmHUK 168, no. 11 (1883): 5-93.

46 Idem, H3 ucmopuu unocmpauHbix ucnoBedauuu b Poccuu b XVI u XVII BeKax

(Moskow, 1886).

47 Bernhard Ihringer, "Quirinus Kuhlmann," Zeitschrift fiir Bucherfreunde 1 (1909):

179-82.

48 For their list see Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, n. 7-9, pp. 359-60.

49 Quirinus Kuhlmann, Ausgewahlte Dichtungen, ed. Oda Weitbrecht (Potsdam: Hadern

Verlag, 1923).

20

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

were published, by Will-Erich Peuckert50 and Johannes Hoffmeiser,51

respectively: some important sources were found and published by Theodor

Wotschke52 and Dmitrij Cizevskij;53 but World War II interrupted progress

in these investigations.

A new momentum for these studies came in 1950, in the article “Stand

und Aufgaben der deutschen Barockforschung” by Erik Lunding.54 The

special studies on Kuhlmann furnished information about him and spurred

interest in him for general researches on history, literature, religion, and for

lexicons:55 from time to time his lyrical works appeared in various

anthologies.56 A tendency towards a search for and careful study of the

sources, as opposed to generalization, is evident in some works engaging

with different aspects of Kuhlmann’s biography and writings, such as the

studies by Robert L. Beare,57 Claus Victor Bock,58 Curt von Faber du

Faur,59 Leonard Foster and A. A. Parker,60 Blake Lee Spahr61 and B. O.

50 Will-Erich Peuckert, "Quirinus Kuhlmann" In Schlesische Lebensbilder, edited by

der Historischen Kommission fur Schlesien, vol. 3, edited by Friedrich Andreae et all.

(Breslau, 1928), 139-144.

51 Johannes Hoffmeister, "Quirinus Kuhlmann" Euphorion 31 (1931): 591-615.

52 Theodor Wotschke, "Neues von Quirin Kuhlmann," Zeitschrift des Vereins fiir

Geschichte Schlesiens 72 (1938): 268-75.

53 Dmytro Cizevskij, "Zwei Ketzer in Moskau" Kyrios 6 (1942/43): 29-46. Reappeared

in his, Aus zwei Welten: Beitrage zur Geschichte der slavisch-westlichen literarischen

Beziehungen (Den Haag, 1956) 231-68.

54 Erik Lunding, "Stand und Aufgaben der deutschen Barockforschung," Orbis

Litterarum. Revue Danoise d'histoire litteraire 7, no. 1-2 (1950): 27-91.

55 For a list see Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, n. 16, p. 361.

56 For a list see Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, n. 17, p. 361.

57 Robert L. Beare, "Quirinus Kuhlmann and the Fruchtbringende Gesellschaft," The

Journal of English and Germanic Philology 52, no. 3 (July 1953): 346-71.

58 Claus Victor Bock, "Ekstatisches Dichtertum, Die Geistreise Quirinus Kuhlmanns,"

Castrum Peregrini 29 (1956):26-47, repr. in: Antaios 2 (1960): 42-60; idem, "Quirinus

Kuhlmann in Nederland." Duitse Kroniek 10 (1958): 31-38.

59 Curt von Faber du Faur, "Die Keimzelle des Kiihlpsalters." The Journal of English

and Germanic Philology 44, no. 2 (April 1947): 150-9.

60 Leonard Forster and A.A. Parker, "Quirinus Kuhlmann and the Poetry of St. John of

the Cross," Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 35, no. 1 (January 1958): 1-23; Leonard W.

Forster, "Zu den Quellen des ’Kiihlpsalters,’ Der 5. Kiihlpsalm und der Jubilus des

Pseudo-Bernhard." Euphorion 52 (1958): 256-71.

61 Blake Lee Spahr, "Quirin Kuhlmann: The Jenar Years." Modern Language Notes 72,

no. 8 (1957): 605-10.

21

Anrpewg npoekma "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

Unbegaun.62 Some important obscure details of Kuhlmann's biography were

revealed in these brief studies. However, it was Robert L. Beare’s article

“Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ein Bibliographischer Versuch” (1954) that marks a

certain shift in studies of the poet.63 This brief work summarizes the

bibliographic development over years of search for Kuhlmann's extremely

rare writings, reflecting a movement toward the study of exact facts and the

composing of inclusive inquiries.

In 1952, Rolf Flechsig wrote an important dissertation on Kuhlmann,64

the first attempt to explore Kuhlmann's entire biography since Adelung's

work in the eighteenth century. It offered an analysis of his poetry, based on

a wide examination of sources, and the bibliography's accuracy and totality

are among the work's principal achievements. Flechsig compiled his own

list of Kuhlmann's work, and also tried to detect and examine each

individual source. However, his main foundation for biographical facts was

Kiihlpsalter, and Flechsig also declared it in the title of his dissertation: it

was a good departure point, since in Kiihlpsalter Kuhlmann describes his

mythologized autobiography in approximate chronological order. Though

the book's language is none too clear, its text could be compared with other

sources, and Flechsig attempted to do just that. Flechsig's dissertation has

become extremely important for Kuhlmann's scholarship. It gives a very

detailed and full-length biography of Kuhlmann. The dissertation and the

above-mentioned articles by Beare became a basis for further studies.

Flechsig's research, nonetheless, lacks two very important elements. He tries

to include all the important sources, although it is not an easy task, and

perhaps there can be no complete set of sources, when studying a person

like Kuhlmann who read so widely and had such a large circle of contacts.

Without previous researches to rely on, Flechsig had too narrow a base of

information to build upon.

The following year, Robert L. Beare published his article “Quirinus

Kuhlmann: The Religious Apprenticeships,”65 which primarily focuses on

the poet’s biography, and more specifically on his early life experience.

62 B.O. Unbegaun, "Un ouvrage retrouve de Quirin Kuhlmann." La Nouvelle Clio 3:7-8

(July- August 1951): 251-61.

63 Robert L. Beare,“Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ein Bibliographischer Versuch,” La Nouvelle

Clio f> 164-82.

64 Rolf Flechsig, "Quirinus Kuhlmann und sein 'Kiihlpsalter'" (PhD diss., Rheinische

Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universitat, Bonn, 1952).

65 Robert L. Beare, “Quirinus Kuhlmann: The Religious Apprenticeship,” PMLA 68

(1953): 828-62.

22

Anrpewfl npoeirra "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

Prior to his study, Beare had sought out sources on Kuhlmann and became a

leading specialist on them. Claus Victor Bock also made a considerable

contribution to the study of Kuhlmann's life and writings. In 1957, he

published his Quirinus Kuhlmann als Dichter,bb a book in two parts. The

first is a brief, but very substantial biography with some previously

unknown facts and new interpretations of known data. In the second part,

Bock offers his philosophic, unhistorical, conception of Kuhlmann's

"ecstatic" language. The scope of material here is very wide; for instance,

applying psychoanalysis for interpreting Kuhlmann's poetry and religious

imagery. The book's main idea is the affinity Kuhlmann's ideas and

language have with the incantations of shamans. Bock had started studying

this problem earlier,66 67 68 and his monograph elaborate the idea.

The shift in general attitude to Kuhlmann, from neglect to interest,

arrived at the same time as knowledge of his biography became more

widespread; this is discernible in Walter Nigg's well-known book, Heimlich

Weisheit.b* The text does not include any new information on Kuhlmann's

biography and ideas and gives only general information about him.

However, Kuhlmann appears here in the company of the most prominent

and known seventeenth-century mystics, such as Johann Arndt, Jakob

Bbhme, Johann Valentin Andreae, Johann Amos Comenius, Angelus

Silesius, Johann Georg Gichtel and George Fox.

However, for the most part, the Russian period of Kuhlmann's

biography remained unknown in the West. In 1962, A.M. Panchenko wrote

an article about Kuhlmann's political program and its background at the

time of Kuhlmann's visit to Moscow.69 Consequently, the sources are

mainly Russian material concerning the trial against Kuhlmann (1689).

Unfortunately, this article remains unnoted in the West until today.

66 Claus Victor Bock, Quirinus Kuhlmann als Dichter: Ein Beitrag zur Charakteristik

des Ekstatikers (Bern: Francke, 1957).

67 Bock, "Ekstatisches Dichtertum, Die Geistreise Quirinus Kuhlmanns".

68 Walter Nigg, Heimlich Weisheit: Mystisches Leben in der evangelischen Christenheit

(Zurich and Stuttgart: Artemis-Verlag, 1959), 258-73.

69 A.M. IlaHHeHKO, "KeupuH KyjibMan u ’neuiCKue SpaTta,"' in PyccKan mimepamypa

66K06 cpedu cjiaeHHCKux jiumepamyp, ed. JI.A. JJmhtphb h JJ.C.JlHxaneB (MocKBa,

JTeHHHrpaa: H3/taTejitcTBO AH CCCP, 1963), 330-47.

23

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

Beare discovered and published some very important miscellaneous

biographical facts in 1962.70 Walter Dietze, a scholar from East Berlin, with

knowledge of the Russian language, researched the Russian documents on

Kuhlmann and made the main facts known in the West.71 After Dietze's

research, a brief account of Kuhlmann's death in Moscow was discovered;

Gottfried Arnold may have known about this anonymous German text,

which bears the title Quirinus Kuhlmann Leben und Todt. It was published

by Leonard Forster.72 Since this article, there have been no further additions

to the accounts on Kuhlmann's death in Moscow; there have only been some

completely speculative works on his life there and the importance of his

theories for the Russian history of ideas.73 After the publication of the article

on Kuhlmann's death in Moscow, Walter Dietze wrote the best general book

on Kuhlmann to date, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, published in

1963. It is a standard biography with many new facts that Dietze discovered,

and draws on the primary sources and previous research. Dietze briefly

retells the content of Kuhlmann's entire work, excluding some very early

poems recently discovered by Jonathan Philip Clark (Appendix I).74

Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet became the starting-point for all

further studies. It provides Kuhlmann's standard biography and his entire

bibliography, and its main advantage compared with every other work on

Kuhlmann is its inclusiveness, brevity, and high scholarly standards. Dietze

discusses all periods of Kuhlmann's life, and reconsiders the legends about

Kuhlmann. The information on Kuhlmann and his work is wholly based on

primary sources; Dietze tries to draw upon all of them and succeeds better

than any other researcher in the field. The book chiefly presents pure facts,

and though the author offers some theories and abstract explanations, they

do not play a central role. Dietze's book enables and makes necessary the

70 Robert L. Beare, "Quirinus Kuhlmann: Where and When?" Modern Language Notes

77, no. 4(1962): 379-97.

71 Walter Dietze, "Quirinus Kuhlmanns letztes Wirken in RuBland," Sinn und Form 14

(1962): 10-71.

72 Leonard Forster, "Quirinus Kuhlmann in Moscow 1689: An Unnoticed Account,"

Germano-Slavica 2, no. 5 (1978): 317-23.

73 John M. Gogol, "The Archpriest Avvakum and Quirinus Kuhlmann: A Comparative

Study in the Literary Baroque," Germano-Slavica 2 (1973): 35-48; V. David Zdenek,

"The Influence of Jacob Boehme on Russian Religious Thought," Slavic Review 21, no.

1 (1962): 43-64.

74 Jonathan Philip Clark, "From Imitation to Invention: Three Newly Discovered Poems

by Quirinus Kuhlmann," Wolfenbiitteler Barock-Nachrichten 14(1987): 113-29.

24

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

movement from studies that merely collect plain data on Kuhlmann's life

towards studies of Kuhlmann's ideas and placing them in the context of

seventeenth-century thinking. Conducting such studies was a difficult task

before the works of Beare, Flechsig, Bock and particularly those of Dietze,

because of the sparse knowledge about Kuhlmann's biography and

bibliography. Following Dietze's work, it is now possible to concentrate

endeavors on the special aspects of Kuhlmann's ideas and life.

Two tendencies in the studies on Kuhlmann after Dietze's work can be

discerned: the first is greater detail, and the second is the broader reference

made to Kuhlmann in studies on the history of ideas and German literature.

The focus on case-studies of specific writings and ideas, instead of the

composition of the inclusive works, is exemplified in Sibylle Rusterholz's

article with its detailed interpretation of one of Kuhlmann's psalms.75 A

number of dissertations discuss the rhetoric in Kuhlmann's works, such as

that by Klaus Karl Ernst Neuendorf who tried to gain broad insights into the

problem;76 his thesis discussed Kuhlmann's different works. Klaus Karl

Ernst observed the poet's development throughout his life. Neuendorf

emphasized the impact of ars combinatoria on Kuhlmann,77 and a

discussion devoted to this question alone comprises nearly a quarter of the

whole dissertation.78 Ralf Schmittem's thesis examines one of Kuhlmann's

main works, the Kiihlpsalter, and the role of rhetoric in it: the dissertation

deserves special attention for researchers into the alchemical aspect of

Kuhlmann's ideas.79 Schmittem meticulously explores hermetic philosophy

in Kiihlpsalter and the theory of prefiguration (also see sections 2.2 and

4.2), but did not define the subject, and noted the general impact of hermetic

and/or alchemic ideas on Kuhlmann. The meaning of the term "hermetic" in

this work is not thoroughly explained. Schmittem offers general definitions

borrowed from various books on hermetic ideas, and draws weak

comparison between these definitions and his subjective interpretation of

75 Sibylle Rusterholz, "Klarlichte Dunkelheiten. Quirinus Kuhlmanns 62. Kiihlpsalm,"

in Deutsche Barocklyrik: Gedichtinterpretationen von Spee bis Haller, ed. Martin

Bicher and Alois M. Haas (Bern and Munich: Francke, 1973), 225-64.

76Klaus Karl Ernst Neuendorf, "Das Lyrische Werk Quirinus Kuhlmanns:

Interpretationen zu seiner rhetorischen Struktur" (PhD diss., Rice University, 1970).

77 For ars combinatoria, see part 2 of this work.

78 Neuendorf, "Das Lyrische Werk Quirinus Kuhlmanns," 113-51.

79 Ralf Schmittem, "Die Rhetorik des Kiihlpsalters von Quirinus Kuhlmann: Dichtung

im Kontext biblischer und hermetischer Schreibweisen" (PhD diss., Koln, 2003).

25

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

Kuhlmann's writings: it cannot therefore be considered a completely correct,

scientific and empiric research. Producing artificial and simple images

based on modern books, with especially disputable and questionable points

for their comparison, fails to provide reliable data.

Generalization is another tendency in studies of Kuhlmann. The quantity

of data about his life and writings makes it possible to discuss his

personality and ideas in general studies on the history of ideas and German

literature. Werner Vordtriede, for example, who edited a selection of pieces

from the Kilhlpsalter, wrote an article about Kuhlmann, where he repeats

known facts about Kuhlmann's life and his main work. The article's central

problem is Kuhlmann's place among German poets of the Baroque.

Vortriede's estimation is very high: "... er (der Kilhlpsalter) ist doch noch

nur Kuhlmann's Haupwerk, sondern auch eines der Hauptwerke des

deutschen Barock."80 On the article's first page, he notes the importance of

alchemical symbolism in Kilhlpsalter, but does not enlarge on the matter,

simply noting that Kuhlmann borrowed the alchemical symbolism of the lily

and the rose from Bohme (3.5). Conrad Wierdemann depicts a certain

tendency towards irrationality in the poetry, citing examples from Johann

Klaj, Catharina von Greiffenberg and Q. Kuhlmann. 81 Thomas Althaus

compares the stylistic peculiarities of Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg's

Sonneten oder Klinggedichten and Kuhlmann's Himmlische Libes-kilsse?2

he was evidently inspired by Conrad Wiederman.83 Gerald Gillespie

compares theories of the language in the works of Kuhlmann, Kircher and

Leibniz,84 attempting to denote a linguistic tradition particular to Germany.

Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann briefly presents the main facts about

80 Werner Vortriede, "Quirinus Kuhlmanns 'Kilhlpsalter" Antaios 7 (1965-1966): 501—

27.

81 Conrad Wiedemann, "Engel, Geist und Feuer: Zum Dichterselbstverstandnis bei J.

Klaj, C.R. von Greiffenberg und Q. Kuhlmann," in Literatur und Geistesgeschichte:

Festgabe fiir Heinz Otto Burger, ed. Reinhold Grimm and Conrad Wiedemann (Berlin:

Erich Schmidt Verlag, 1968), 85-109.

82 Thomas Althaus, "Einklang und Liebe. Die spracherotische Perspektive des Glaubens

im Geistlichen Sonett bei Catharina Regina von Greiffenberg and Quirinus Kuhlmann,"

in Religion und Religiositat im Zeitalter des Barock, ed. Dieter Breuer (Wiesbaden:

Harrassowitz Verlag, 1995), 2:779-88.

83 Wiedemann, "Engel, Geist und Feuer," 85-109.

84 Gerald Gillespie, "Primal Utterance: Observations on Kuhlmann's Correspondence

with Kircher, in View of Leibniz's Theories," in Wege der Worte: Festschrift fiir

Wolfgang Fleischhauer, ed. Donald C. Reichel (Cologne and Vienna: Bohlau, 1978),

27-46.

26

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

Kuhlmann's biography and ideas;85 though his article is mainly a

compilation, his analysis of Kuhlmann's ideas is deep and inclusive.

Schmidt-Biggemann makes many important parallels and remarks

concerning general patterns of Christian religious thinking in the

seventeenth century, offering an original interpretation for some of

Kuhlmann's vague symbols. Jonathan P. Clark researched the

transformation of Baroque discourse into the speech patterns of the

Enlightenment, and defines the problem as follows: "Schwarmerei and the

related phenomena of "fanaticism" and "enthusiasm" provide insight into

the transference of interpretive paradigms from the seventeenth-century

religious orthodoxy to Enlightenment discourses."86 Even though the

problem is very broad, Clark principally relies on chronological and

ideological tendencies found in reactions to Kuhlmann's work: Clark had

previously written a dissertation on Kuhlmann.87 After the works of

Flechsig, Bock, and Dietze, the biography of Kuhlmann and his main ideas

became clearer. Before their works, in spite of Kuhlmann's importance for

understanding the history of religion and literature in the seventeenth

century, he was rarely and superficially studied, and any interest in him was

hampered by incomplete knowledge of his biography. After Dietze's book,

Kuhlmann became commonly cited in works on the history of ideas and

German literature; a full list is unnecessary, and only a few examples

follow. Jutta Weisz awarded significant attention to Kuhlmann's

Unsterbliche Sterblichkeit in her general study of German epigrams in the

seventeenth century.88 Kuhlmann is cited in two books by Andrew Weeks,

one on Jakob Bohme89 and the other a history of German mysticism.90 The

85 Wilhelm Schmidt-Biggemann, "Salvation through Philology: The Poetical

Messianism of Quirinus Kuhlmann (1651-1689)," in Toward the Millennium:

Messianic Expectations from the Bible to Waco, ed. Peter Schafer and Mark Cohen

(Leiden, Boston, Koln: Brill, 1998), 259-98.

86 Jonathan P. Clark, "Beyond Rhyme or Reason. Fanaticism and the Transference of

Interpretive Paradigms from the Seventeenth-Century Orthodoxy to the Aesthetics of

Enlightenment." German Issue 105, no. 3 (April 1990): 563-82.

87 Idem, "Immediacy and Experience: Institutional change and Spiritual Expression in

the Works of Quirinus Kuhlmann" (PhD diss., Berkley, 1986).

88 Jutta Weisz, Das deutsche Epigramm des 17. Jahrhunderts (Stuttgart: J.B.

Metzlersche Verlagsbuchhandlung, 1979).

89 Andrew Weeks, Boehme: An Intellectual Biography of the Seventeenth-Century

Philosopher and Mystic (New York: State University of New York, 1991), 2.

27

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN

brief remarks on Kuhlmann in the book on Bbhme demonstrate awareness

to Kuhlmann's special role in the rich tradition of his interpreters and

followers, although such remarks were not unique or novel, since Kuhlmann

was also mentioned, for example, in John Joseph Stoudt's well-known study

on Bbhme.90 91 The references to Kuhlmann in Weeks' second work are more

significant; although he did not attempt to produce a comprehensive history,

he described some of the most important points in the history of German

mysticism and Kuhlmann appears in that context. In his references to the

poet's biography and ideas, Weeks completely relies on Dietze. Kuhlmann is

presented as a predecessor of the writer and graphic artist Gunter Bruno

Fuchs (1928-1977) in a recent study by Georg Ralle.92 Though this work is

not important for the present research, it reflects the current state of

Kuhlmann scholarship: he has finally become a widely known Baroque

poet, and information on his biography and writings are easily accessible.

Alchemical imagery is, however, the theme of the present work, not

Kuhlmann's biography or bibliography. Though frequently mentioned in

works about Kuhlmann, in his lifetime and until today, alchemical imagery

has never received special scholarly attention. Kuhlmann's fame as an

alchemist began during his lifetime. As we will see later, Kuhlmann often

referred to alchemical books, communicated with prominent alchemists and

appealed to them. In the polemic against Kuhlmann, Breckling (see also 2.3)

notes that fact:

....noch ein ander Thronfurst Quirin Kuhlmann/ der sich selbst schon fiir

Salomon von Kaiserstein ausgibt Denn ein jeder wil gern der Elias

Artista selbst seyn / und von alien falschen Alchymisten und Goldsuchern/

die gleich der Erden Gold machen und auff das Gold mehr als auff Gott

hoffen/ verehret und angebehten seyn....93

90 idem, German Mysticism from Hildegard of Bingen to Ludwig Wittgenstein: A

Literary and Intellectual History (New York: State University of New York Press,

1993), 172, 185, particularly 190-1.

91 John Joseph Stoudt, Sunrise to Eternity: A Study in Jacob Boehme's Life and Thought

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957), 64.

92 Georg Ralle, Gunter Bruno Fuchs und seine Literarischen Vorlaufer: Quirinus

Kuhlmann, Peter Hille und Paul Scheerbart (Hannover - Laatzen: Werhahn, 2007).

93 Cited according Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 252.

28

Anrpewfl npoeKTa "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

ALCHEMICAL IMAGERY IN THE WORKS OF

QUIRINUS KUHLMANN

Breckling especially emphasized the impact of Paracelsus on Kuhlmann,94 95

and was not the only one who made such assertions. In later books,

Kuhlmann is usually grouped together with Paracelsus and Jakob Bbhme,

though the theme is not emphasized. Kuhlmann's main characteristics are

"phantast" and "enthusiast." In Gottfried Arnold's Unparteyische Kirchen

und Ketzer-Historie (first edition in 1699-1700; in the edition of 1629,

3:197-201) he included the first reliable biography of Quirinus Kuhlmann,

with a critique of his works. Arnold clearly underscored the impact of

alchemical works on Kuhlmann. Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was interested

in Kuhlmann's ideas on the ars combinatorial and noted alchemy and

enthusiasm as Kuhlmann's main inspirations: "Quirin Kulman Silesien

home de scavoir et d'esprit, mais qui avoit donne depuis dans deux sortes de

visions egalement dangereuses, 1'une des Enthousiastes, 1'autre des

Alchymistes..."96 In volume IX of his Geschichte der menschlichen

Narrheit (1799), Johann-Christoph Adelung unmistakably stressed

Kuhlmann's fame as an adept, and thus his dependence on alchemical

sources.

Over time, Kuhlmann's alchemical inspirations were noted in nearly

every mention of him, though not verified or explained. Flechsig - in his

work on Kuhlmann's biography and writings - showed a complete

misunderstanding of the problem, and alchemy for him is akin to black

magic. Notwithstanding, he defended Kuhlmann and Bbhme, who he

believed, applied alchemy only for its symbolism, without magical

connotations: "Der Gebrauch von alchemischer Terminologie war durchaus

iiblich und begint keine schwarzmagische Betatigung. Gerade bei Boehme

wird sie haufig als Symbologie benutzt...."97 Flechsig tried to avoid any

deep inquiry into the problem.

In the basic book on Kuhlmann's biography and bibliography, Dietze's

Ketzer und Poet (1963) he frequently mentions alchemy's impact on

Kuhlmann. Though the theme is not important for that book's main concept,

it is unavoidable in research into Kuhlmann. Dietze accordingly did not

94 Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, n. 156, p. 473.

95 Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 344-7.

96 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Nouveaux Essais sur I'Entendement Humain (1703-1705)

in Book 4, chapter 19. Cited according Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, Samtliche Schriften

und Briefe (Darmstadt, Leipzig, Berlin: Akademie-Verlag, 1962), 4/2: 507. Dietze cited

German translation: Dietze, Quirinus Kuhlmann: Ketzer und Poet, 347.

97 Flechsig, "Quirinus Kuhlmann," n. 16, pp. 327-8.

29

Anrpewfl npoeirra "Upgrade & Release": https://vk.com/upgraderelease

EUGENE KUZMIN