Текст

Г. М. УАЙЗЕР, С. К. ФОЛОМКИНА, Э. И. КААР

ENGLISH

УЧЕБНИК

АНГЛИЙСКОГО ЯЗЫКА

ДЛЯ X КЛАССА

СРЕДНЕЙ ШКОЛЫ

Утверждён

Министерством просвещения РСФСР

10-е издание

ИЗДАТЕЛЬСТВО «ПРОСВЕЩЕНИЕ»

Москва★ 1 973

4 И (Англ) (075)

У 12

6-6

LESSON ONE

Exercises

I. Say where you went last summer, when you went there, who you

went with how long you were there, and when you came home.

II. Say what you usually do during your summer holidays, and what you

want to do next summer. Use the phrase

Next summer, f'd like to...

111. Complete the following sentences; say something about your summer

holidays or your future holiday plans.

1. We couldn’t ... because ...

2. We had planned .... but ...

3. I’d like ... if ...

4. Some of my friends ..., so ...

IV. Ask one of your classmates two questions: a) where he went last

summer; b) who he went with (or who he stayed with).

V. Ask one of your classmates a question about his plans for next sum-

mer. Let him answer, using the phrase

/ think so (I don't think so)

Example: A.: Are you going to the country next summer?

В.: I think so I was there this summer, and my

uncle has invited me to come again next

summer.

VI. Study the meaning and use of the new words as seen in the follow-

ing examples:

to need: 1 need a new pen. We went to the South because

my mother needed sea air. He needs ten more minutes

to finish the work. If you need me, ring me up. Do you

need anything else?

slow: Don’t be so slow — we’ll be late! The clock is five

minutes slow. Speak more slowly, please. They walked

home slowly

fast: Don’t walk so fast! They began to work faster. My

watch is a few minutes fast

to move: 1) I couldn’t move the box. He moved the lamp

nearer. 2) The car was moving too fast to stop. The boy

3

was afraid to move. The train was moving slowly.

Don’t move!

end: I have quite forgotten the end of the story. At the

end of the story, he comes home again. He read the

book from beginning to end. He lives at the end of our

street. We are going to have an English party at the end

of the month.

to prepare: We prepared everything for the excursion. 1 must

prepare to answer the questions. The wall newspaper was

prepared by three pupils.

VII. Add a sentence logically connected.

Example: 1 need a new pen. I’ve lost my old one.

1. If you need me, ring me up. ...

2. They walked home slowly. ...

3. They began to work faster ...

4. Don’t move! ...

5. He read the book from beginning to end ...

VIII. a) Say what you need and why (or what somebody in your family

needs and why).

Examples: 1 need some help. I must find ten pictures for

our wall newspaper.

My sister needs a new ski suit. Her old one is too

small for her now.

b) Say what you (or one ot your classmates) can do fast and what

you do (or he does) slowly.

Example: I can skate fast, but I

c) Say what you are going to do

swim slowly.

at the end of

the week

the month

the year

IX. Read and translate orally the italicized part in each sentence (without

a dictionary).

A. 1. I’d like to have some hot milk. 2. Some time passed.

3. At the end of the summer we made friends with some

boys from Czechoslovakia. 4. Some of the pupils from

our school worked on a collective farm this summer.

5. We must go to some quiet place in the mountains.

В. 1. I need some more time. 2. He liked fruit more than

anything else. 3. Jim could not work more than he did.

4 Now we had only one more question to discuss. 5. The

task becomes even more difficult in the rain.

4

С. I. When did you last go to a pioneer camp? 2. Last

summer we made a camp in the forest and lived there

for a week. 3. Have you ever camped out? 4. Camping

is very pleasant in fine weather.

D. 1. She stood looking at me in surprise. 2. The boy lay in

bed thinking about his plans for the day. 3. We sat

talking about new films. 4. “Take it,” he said talking

fast and pushing the letter into my hand.

X. Guess the meaning of the italicized words; pronounce them correctly.

A. 1. I never complain of bad appetite ['aapitait].

2. That was a really romantic Fra'maentik] story.

3. In Tallin we stayed at a hotel [hou'tel].

4. Do you know Russian poetry f'pouitri] well?

В. 1. How does the film end? The story of his adventures

was endless.

2. The project ['prodjektl you are going to work on is

very interesting. I think there is a real need for it.

3. You can get from London to Edinburgh ['edinbara],

the capital of Scotland, in six hours by fast train.

4. The boy lay without movement. We watched the slow

movements of the machine. Pete won the chess game

after only seventeen moves.

5. The car slowed up when we came to the village.

XI. Read the text “Holiday Plans” at home, giving special attention to

the use of the following words:

a) to return, to pull out, a fire, to fish, a sound, a smell

towards;

b) to move, to need, an end.

Prepare for classroom discussion of the questions in Exercise XII

(page 7).

HOLIDAY PLANS

(Retold from “Three Men in a Boat” by Jerome K. Jerome)1

There were three of us in my room: George, and Harris, and I.

We sat talking about our health, and we all agreed that we were

very ill. I explained to my friends how I felt when I got up in

1 Jerome K. Jerome [dja'roum 'kei dja'roum] (1859—1927) — an English

writer whose humorous stories won great success even outside of England.

His most popular books are: “Three Men in a Boat”, “Three Men on the

ВиттеГ, “The Idle Thoughts of an Idle Fellow”.

5

the morning and began to move about, and Harris described how

he felt when he went to bed. Then George lay down on the sofa

and showed us how he felt at night.

We didn’t know what was the matter with us, but we were

all sure that we worked too hard and that we needed a good

rest. “We must go to some quiet place in the mountains, far

from the noise of London,” George said. I thought it was a good

idea, but Harris didn’t agree with us. “We shall have a better

rest if we go on a sea trip,” he said. “The smell of the sea will

be good for our health.”

I didn’t like the idea of a sea trip, and 1 said so. A sea

trip is good if you can go for two or three months. But you

can’t get any enjoyment out of a sea trip if you go for only

one week. I remember, my sister’s husband once went on a short

sea trip from London to Liverpool.1 He bought a return ticket,

but when he came to Liverpool, the only thing he wanted to do

was to sell the ticket. He found a young man who needed sea

air and exercise and who wanted to go to some place near the

sea. “Near the sea!” my sister’s husband said talking very fast

and pushing the ticket into the young man’s hand, “You can be

on the sea —as much sea air as you like. And exercise! If you

try to walk more than three yards8 on the ship, you will have

enough exercise for your whole life!” He himself returned home

by train; he said that trains were good enough for him.

Then George remembered how his aunt felt once on a sea

trip, and at the end of his story I think Harris understood us,

because he said, “Let’s go up the river. A boat trip on the river

will keep us in the open air and give us exercise. We can fish

and swim. The hard work will give us good appetite and make

us sleep well.”

I said that I could not understand how George could sleep

more than he did now. “Every day has only twenty-four hours,

both in summer and in winter,’’ I said. But we all agreed that

Harris* idea of a boat trip was a good one. So we pulled out

maps and began to discuss plans.

We arranged to start on Saturday from Kingston8 and go up

the river towards Oxford.

Then we discussed where to sleep at night. George and 1 want-

ed to camp out every night. “A camp is so romantic,” we said.

But Harris said, “And what if it rains?”

There is no poetry in Harris. But we had to agree that there

was truth in his words. Camping is not very pleasant when it

rains. You come to the place in the evening. Your clothes are 1 2 *

1 Liverpool f'livapu:!]

2 A yard is about 91 centimetres.

8 Kingston f'kiflstan] — пригород Лондона

6

wet, and there is water in the boat and in everything in the

boat. Two men take the tent out of the boat and begin to put it

up; the third man begins to throw the water out of the boat.

It isn’t easy to put up a tent in dry weather; and the task

becomes even more difficult in the rain. You are sure that the

other man isn’t trying to help you. The tent has just fallen a

second time, when the third man (the one in the boat) suddenly

asks, “Why are you so slow with that tent? Why haven’t you

put it up yet?”

At last, you put up the tent and try to make a fire to get warm

and cook supper. But that is a hopeless task in the rain. So you

decide to eat some cold food and go to bed. But you don’t eat

your food, you drink it, because the bread is full of water, and

the salt, the sugar and the butter are all swimming together and

make a kind of soup...

We thought of all this, and of the wet ground, and the sound

of the rain on the tent, and decided to camp out in fine weather

and to sleep in a hotel in bad weather

Now we had only one more question to discuss—what to take

with us. But Harris said he had had enough discussion for one

evening So we put on our hats and went out for a walk.

Xll. Discuss possible answers to the following questions

1. What was really the matter with the three friends?

2. Why did the friends decide not to go to some quiet place

in the mountains?

3. Why didn’t Jerome like the idea of a sea trip?

4. Why did they all agree to a boat trip?

5. What made the friends discuss the question of camping

out?

XIII. Tell the story. Here is the plan.

1. The three friends decide they need a good rest.

2. Jerome and George do not like the idea of a sea trip.

3. A boat trip —that’s the thing the friends like.

4. Camping out is not always pleasant

XIV. Speak about the picture “A Camp in the Forest”

a) Say what you see in the picture. Use the words:

camp n, to make a fire, to cook, fish n (pl fish),

smell n, sound n, to move.

b) Speak about each of the people in the picture. Say what you think

they did before the moment you see them in the picture.

7

A CAMP IN THE FOREST

XV. Say when you last used one of the means of transportation shown in

the pictures. Then answer the questions.

8

A. 1. Where did you go?

2. How long did your trip (journey) last?

3. Who did you travel with?

4. Where did you stop?

5. What places of interest did you see (visit)?

6. What did you do there?

7. Did you enjoy your trip (journey)?

В. 1. Have you ever camped out? How did you like it?

2. Would you like to camp out again?

XVI. Look at the pictures and say what happened to the two friends

Homework

I .* Write three sentences like those in Exercise II (page 3).

11 .* Copy the following sentences, using a preposition where necessary:

1. You can get ... N. in eight hours ... fast train.

2. She did not move until she read the story ... the end.

Then she slowly closed the book.

9

3 The boys need ... a hammer and some nails to mend

the bench

4 The boys came back ... the country ... the end ...

August.

5. What would you like to prepare ... our English

party?

HL* Do Exercise XI (page 5).

IV * Copy out the Past Tense forms of the irregular verbs (19) used in the

text “Holiday Plans9’. Write their infinitive forms.

Example: were—to be.

V .* Find (he sentences in (he text where the word trip is used (8 sen-

tences) and copy them out: underline the word combinations in which

the word trip appears.

VI .* Read the story “The Tent That Danced” in Lesson Two without using

a dictionary. Prepare to answer the questions given before the text.

Vocabula

end n, v

fast a, adv

fire n

fish n, v

move o, n

ry to be

need v, n

prepare v

pull (out) v

return v

slow a

remembered

smell n, v

sound n

towards prep

I’d like...

LESSON TWO

Questions:

1. Why did the friends call Stanford “Shorty"?

2. Why did two of the men go away and why was Shorty (eft alone in

the camp?

3. What made Shorty leave his comfortable place by the fire?

THE TENT THAT DANCED

(Retold from the story by Stephen Crane)1

Jim and Ed were big, strong young men. Their friend Stanford

was a little man, who looked even smaller when the three of

them stood together. They always called him “Shorty”.

Once they came to a forest to fish. They put up their tent at

the foot of a hill near the lake and were ready to catch all the

fish in it. But perhaps the fish there were remarkably clever, or

they were not hungry. Perhaps the men were not good fishermen ..

Days passed and they caught —nothing.

When they had eaten their last loaf of bread, they decided

that two of them must go to the nearest village for food while

the third stayed to watch the camp.

1 Stephen Crane ['stfcvn 'krein) (1871—1900)—an American writer, the

author of many short stories and novels. One of his best-known books —

"The Red Badge of Courage" — is about the Civil War in America.

11

returned. Shorty

“Shorty is too small and weak to carry

much,” Ed said to Jim, “so we’ll have to go.”

The two men were not very happy at the idea,

for their camp was far from the nearest village.

“You’ll stay here and be comfortable, Shor-

ty, while we have to walk all the way to the

village and back,” Ed said complainingly.

“I hope the devil comes to keep you com-

pany,”1 said Jim, as he and Ed started for the

village.

Night came, and the two men had not yet

sat near the camp-fire, looking into the dark

forest and listening to the wind in the trees. Suddenly, he heard

strange sounds. He stood up slowly and his legs felt very weak.

“Hah!” he shouted. A growl2 answered, and a big, black bear

came out of the forest towards the fire. Shorty and his uninvited

visitor stood looking at each other. The bear looked like a vet-

eran and a fighter. His little, red eyes shone, his open mouth

looked very red and very big.

Slowly the bear began to move towards the little man, who

turned and ran around the camp-fire. “Ho!” said the bear to him-

self, “this thing won’t fight — it runs. Well, I’ll catch it.”

And he started to run after Shorty. Now Shorty didn’t run —

he flew, the bear after him. They ran around the fire, the bear

coming nearer and nearer. Then Shorty flew into the tent.

The bear stopped in front of the tent. Then he put his head

into it and smelled. He could smell many people, but he could

see no one. The little man lay in the far corner of the tent. He

was too frightened to move. Then, slowly and carefully, the bear

moved into the tent...

Exercises

I. Look at the three series of pictures. Which series do you think

describes the end of the story best? Tell the end of the Story according

to the series you have chosen, using the words given with each picture.

1.

at that moment

to appear

to return

to understand

in danger

1 I hope the devil comes to keep you company.—Надеюсь, черт придет

составить тебе компанию.

* a growl [graul] — рычание, ворчание.

12

to km

to look out

slowly

(not) to move

to pull

dead

around the fire

to tell

the other end of

the tent

fast

towards

high up

to return

to see the danger

13

to kill

at the foot of the

tree

to come down

slowly

3.

a stick

a hat

the end

to move towards

to get frightened

to return

to be surprised

to run after

fast

around the fire

to feel proud

to tell

14

II. At home read the author’s end of the story on page 144. Explain

Shorty's answer to his friends' questions.

III. Translate orally in class.

1. Stanford was called “Shorty” by hfs friends. Stanford,

called “Shorty” by his friends, was not a very strong man.

2. The tent was put up by the friends at the foot of a hill.

The tent, put up by the friends, looked very small

among the big trees.

3. The sound was heard by the people around the fire. The

sound, heard by the people around the fire, came from

the lake.

4. The boat was carried by the water. The boat, carried by

the water, was slowly moving towards an island in the

middle of the river.

5. The sledge was pulled by six dogs. The sledge, pulled

by six dogs, stopped in front of the post-office.

IV. Translate in writing at home, using a dictionary.

SAILORS’ FRIEND

There are very dangerous reefs near the northern coast of New

Zealand. In the summer of 1871, a ship called the ‘Brindle”

was moving slowly through a fog near the reefs. Some sailors on

the ship suddenly saw a tremendous white dolphin in the water

It swam towards them and then turned and swam in front of the

ship. The dolphin seemed to lead the ship, and it swam on and

on until the ship had passed the dangerous reefs. Then it swam

away, and the ship, led by the dolphin Into open water, con-

tinued on its way.

From that time on, every ship that came to the reefs was met

by the white dolphin. Sailors in every port knew about the

dolphin; thanks to its “work” not one ship was lost on the reefs.

The dolphin, protected by a special law, appeared in front of

every ship that came near the coast of New Zealand. It continued

to serve as a ships’ pilot until 1912. Of course, no one could be

sure that it was the same dolphin, and no one has ever discov-

ered what made the white dolphin (or dolphins) pilot ships past

the reefs for forty years.

LESSON THREE

Exercises

I. Say what you have decided to do after finishing school. Use the

phrases:

After finishing school ...

I have decided ...

1 haven’t decided yet ...

I’d like to ...

Example: I have decided to go to work after finishing school.

I’d like to get work at a factory

11. Say what you wanted to be at some time in the past. Then repeat

what you said in Exercise I. Use the phrase

... 1 changed my mind and decided ...

111. Say the same things that you said in Exercises 1 and 11 about one of

your friends or a member of your family.

IV. Ask one of your classmates about his future profession. Let him an-

swer, using the phrase

/ thin! so (I don’t think so).

Example: A: Are you going to be an engineer?

В: I don’t think so. I’d like to be an architect.

But I haven’t decided yet.

V. Study the meaning and use of the new words as seen in the following

examples:

examination, We took our first examinations in the 8th

to pass, form. The Russian examination was the

university, most difficult, and most of the boys and

(technical) girls were afraid of it. But we had worked

college: hard, and almost all the pupils did well at

the examination. All the pupils in our class

passed the examination.

Some pupils in our class want to continue their

studies after finishing school. Two of them want to enter

16

Moscow University, three — technical colleges, one—

a medical college, and the others have not decided yet I’d

like to study at a teachers’ college or at a university.

We are all working very hard as we shall have

to take (and, of course, we hope to pass!) our entrance

examinations.

VI. a) Say what you’d like to be or where you’d like to work. You may

need some of the following words and word combinations:

an actor, an artist, a doctor, a scientist, a teacher,

a pilot, a worker, a writer, a dancer, an engineer, a tech-

nician [tek'nifan], a mechanic [tni'ksntk], a collective farm-

er, etc.;

at/in a hospital, at/in a factory, at/in a library, in/at

a plant, on the radio (TV), at/in school, on a collective

farm, at/in a theatre, in the cinema, etc.

b) Say where you’d like to get your training:

I’d like to get my training

at a university

at a technical college

at a teachers’ college

at a medical college

at a theatre school

at a technical school

at a medical school

c) Say three or more sentences about yourself:

Example: I’d like to work at a hospital. I’d like to be a

doctor. I want to get my training at a medical

college.

VII. Speak about yourself and your classmates following the examples in

Exercise V (page 16).

VIII, Study the meaning and use of the new words as seen in the following

examples:

used to: 1 still remember the wonderful stories that my

grandmother used to tell me. Last summer we used to

play volley-ball almost every afternoon.

to act: You didn’t act right. I didn’t like the way he acted

at the meeting. He acted like a hero.

immediately: We shall begin immediately. Call him imme-

diately. We had to act immediately.

to die: The great Russian poet Pushkin died in 1837. He

died young. The dying man called his three sons. He

died fighting for freedom.

17

right, л: Everybody in our country has the right to work

and to study. Women in our country have the same rights

as men. Workers in capitalist countries have to fight for

their rights. You have no right to keep library books

so long.

IX. Say two sentences about what you did last summer (when it rained,

in fine weather; in the morning/afternoon/evening; after breakfast,

after lunch, after dinner, after supper).

Example: Early in the morning 1 used to go fishing.

When it rained, I used to play chess with my

brother or read something.

X. Study the following groups of sentences. After reading each group

discuss the difficulties that the gerunds present for translation.

A. I. 1 like fishing (to fish) early in the morning. 2. The

travellers continued moving (to move) towards the vil-

lage because they wanted to spend the night there.

3. We planned seeing (to see) a number of cities on the

journey down the Volga.

В. 1. She never enjoyed cooking. 2. I’ll begin the doors

after I finish washing the windows. 3. She didn’t stop

sewing until it was too dark to see.

С. I. Camping is very pleasant in fine weather. 2. Making

a fire is very difficult in the rain. 3. Fishing gives me

much enjoyment. 4. John’s last job was cleaning buses.

5. Seeing is believing. (English proverb.)

D. 1. Jim and Ed were not very happy at the idea of going

to the village. 2. She was tired of listening to his jokes.

3. The girls thought of returning to their collective

farm at the end of May. 4. When he was a boy, he

dreamed of becoming a great traveller. 5. I have never

had a chance of visiting Kiev.

REMEMBER!

One construction only

to stop

to finish

to enjoy

doing something

to think

to be tired

to dream

a chance

an idea

a plan

of doing something

18

XI. Guess the meaning of the italicized words; pronounce them correctly.

A. 1. The army attacked the city. Three attacks were made

during the night.

2. Our industry I'mdAstn] needs many trained specialists.

Young specialists are needed in all industries.

3. We were sure he had a good chance [tjarns] ol winning

in the coming races.

4. The girl had a talent ['taelant] for drawing.

5. The news was met with enthusiasm [in'6ju:ziaezm].

6. We found an ideal [ai'dial] place for our camp.

7. Jerome’s friends decided not to eat in restaurants

['restaro:gz], but to prepare dinners themselves.

8. It was a typical ['tipikal] camp dinner.

В. 1. He was named Henry after his grandfather. My sister

has a friend, named Jane.

2. The engineer made a careful examination of the engine.

The doctor examined my eyes.

3. He couldn't explain his actions. Actions speak louder

(громче) than words. (English proverb.) The time has

come for action. He lived an active life. The first act

of the play was not interesting. He acted very well

in “Othello [o'0elou]”.

4. We saw very well-trained dogs in the circus They got

special training in the circus school. They were trained

to dance and walk on two legs.

XII Discuss the translation of the following sentences.

1. Glasgow’s ['glaezgouz] George Square is a pleasant contrast to

the old black houses around it It is a lunch-time meeting

place for thousands of people.

2. Now, George Square has become another kind of meeting

place.

3. It was in George Square that 1 met a sixteen-year-old boy.

4. When I spoke to John, this is what he said ...

5. It’s difficult to have dreams when your life is falling to

pieces around you.

6. In Scotland, 10,000 young people under eighteen are

unemployed—one-third of the youth under eighteen.

7. Tens of thousands of working-class youth arewithout jobs.

8. You are not wanted.

XIII. Read the text “One of Thousands” at home, giving special attention

to the use of the following words:

a) unemployed, to unite, a government, to serve;

b) named, used to, a chance, to train, industry, a right.

Prepare for classroom discussion of the questions in Exercise XIV

(page 23).

19

ONE OF THOUSANDS

The Story of John McGlinchey 1 by Doug Bain

Glasgow’s George Square is

a pleasant contrast to the old

black houses around it It is a

John McGlinchey wants to find a job.

lunch-time meeting place for

thousands of people who like to

sit in the sun among the flower-

beds and listen to the jazz bands1 2

which play during the summer

months.

Now, George Square has be-

come another kind of meeting

place; for when lunch-time is

over and the bands have stopped

playing, hundreds of young peo-

ple can still be seen in the

square—young people who have

nothing to do the whole day —

Glasgow’s unemployed youth.

It was in George Square that

I met a sixteen-year old boy,

named John McGlinchey, who

has been out of work since No-

vember last year.

TYPICAL

John is a typical young teen- died and John had to leave to

ager.3 4 He went to a senior sec- help at home.

ondary school* until his father Since he left school, he has

1 John McGlinchey [ma'glintfi]

* a jazz band fcfeaez 'band)—джаз-оркестр

• a teenager ['ti:n,eidja] — a boy or a girl who is between thirteen and

nineteen years old

4 senior ['si:nja| secondary school — forms 9—11

20

had jobs in a fish shop, a res-

taurant, and a few other places.

His last job was cleaning

buses, but when his mother fell

ill, John had tostayathome—

to wash, cook and clean for his

eight younger brothers and sis-

ters. Of course he lost his job.

For ten months since then,

John has gone to the Labour

Exchange1 every day, looking

for a job. He will take any kind

I hear about the games from my

friends. I can’t go to the pic-

tures2 or to dances.

I would like to be a motor-

mechanic, but I don’t think I

have a chance of becoming a

mechanic. I want work —any

kind of work. I’m tired of doing

nothing. Most of the time, when

Гт not looking for a job, I

stay at home.”

I spoke to John for an hour

Unemployed school-leavers.

of work that he can find. When

I spoke to John, this is what he

said:

“I would like to do the things

other young people do. I’ve got

a good bicycle, and I like riding

it. But I’m thinking of selling

it. We need money at home. I

used to go to football games on

Saturdays, but I can’t go now.

and felt that here was a typ-

ical teenager who has all the

dreams and hopes of youth. But

It’s difficult to have them when

your life is falling to pieces

around you.

In Scotland, 10,000 young

people under eighteen are un-

employed—one-third of the

youth under eighteen. Of that

1 the Labour Exchange ['leiba(r)iks'tfeind3j—биржа труда

8 to go to the plctures=»to go to the cinema

21

more than 2,

•Illi

have

never had a job since they

left school. From all corners of

Britain, the same story comes

Al! teenagers up to eighteen

must have a chance of becoming

part-time students.2 The country

must help part-time students to

Youth demonstration against unemployment.

in: from Wales, from Mersey-

side, from Sunderland1 and even

from the “rich" South-East of

England. Tens of thousands of

working-class youth are without

jobs. If you have just left school,

you are not wanted! Take your

place in the army of unemployed!

Britain needs thousands of

trained people—engineers, scien-

tists, technicians of all kinds.

We must train boys and girls in

all industries, all school-leavers

must be employed.

become full-time students® and

to pass their examinations for

universities. England needs ten

new universities and better tech-

nical colleges to train half a

million scientists and engineers.

For their free time, young

people need playing fields, swim-

ming-pools, clubs and theatres.

We must stop the attacks on

the rights of youth. A govern-

ment which cannot find a place

for the talents, the enthusiasm

and ideals of its youth must be

1 Wales [weilz], Merseyside ['matzisaid), Sunderland ('sAndaland)

a A part-time student—a student who works and at the same time stud-

ies at school, a university or a college, a full-time student—a student who

does not work anywhere and only studies at school, a university or a college.

changed. Young people must

unite in the struggle against

the Tory Government.' They

must fight for their right to work

and to live a full, interesting

life.

XIV. Answer

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

the following questions:

Where did the author of the article meet John McGlin-

chey? Why did he find him there?

What can you say about John’s family?

Why didn’t John finish school?

Why did John lose his last job?

What did John dream of?

The government serves only

the interests of big business, the

monopolies. Young people must

act immediately, together with

older workers to change the Brit-

ish government.

XV. Speak about John McGtinchey’s life.

XVI. Find answers to the following questions in the text and discuss them.

1. How many young people were unemployed in Scotland in

1963? Was this so only in Scotland?

2. What rights of the youth does the author write about?

3 Did the government in Great Britain solve the

pr blem of Britain’s need of trained specialists?

4 How does the author understand the task of the youth

of Great Britain?

5. Why does the author call John McGlinchey a typical

teenager?

XVII. Speak about your plans for the future (what you are going to do af-

ter finishing school).

XVIII. Speak about Pimenov’s picture “University Lights”.

1 the Tory ['tan) Government — правительство, большинство которого

составляют члены партии тори —консервативной партии Англии

23

Homework

I.* Do Exercise Vic) (page 17) in writing.

IL* Prepare for a dialogue in class. Think of what you can tell your

classmates about your plans for the future, and what you can ask them

about their plans.

111 .* Do Exercise XIII (page 19).

IV .* Re-read the text and copy out the sentences in which the words

a chance, a university, a coltege, used to, immediately are used.

V .* Read the article by A. Johnstone in Lesson Four without using a

dictionary. Prepare to answer the questions given before the text.

Vocabulary to be remembered

act n, v,

attack v, n

chance n

college n

die v

examination n

government n

immediately adv

Industry (industries) n

lunch n

mechanic n

pass v

right n

serve v

technical a

technician n

train v

unemployed a

unite v

university n

change one’s mind

named ...

used to ...

LESSON FOUR

Questions:

1. How did Volodya happen to fall ill?

2. Why was Volodya taken to Moscow?

3. What can you say about Volodya’s studies?

WHY VOLODYA DIDN’T DIE

By Archie Johnstone'

Pevek is three hundred miles north of the Arctic Circle.1 2 3 The

nearest big city is Magadan, a thousand miles to the south; Mos-

cow is about eight thousand miles to the west by plane. And

all the way through this distance,8 and for more than eight years,

there were people who united their efforts to save the life of Vo-

lodya Trufanov. Volodya’s mother decided to write an open letter

of thanks to all these people. I heard the letter when it was read

over Radio Moscow.

“It all began,” the mother explained, “when Volodya, who was

sixteen then, was playing hockey on his school team in the most

important game of the season. The temperature was minu thirty,

not an unusual temperature for a February day in Pevek. It was

only when the game was over, and Volodya’s team had won, that

he felt *a little frost-bite’.4 * His team-mates took off his boots and

massaged his feet. When he came home, Volodya talked about the

game, but he didn’t say a word about the frost-bite.

A whole month passed before I learned about it.”

One night when his mother came home from work, she found

Volodya in bed with a very high temperature. She ran for help

to the hospital at the other end of town and returned with a young

doctor named Dina Barinova. The doctor examined Volodya and

said that he must have an operation. It was the only chance of

1 Archie Johnstone ('аф 'djonstoun] (died in 1962)—an English journal-

ist; wrote many articles about the Soviet Union, where he lived for several

years, in American and British magazines and newspapers. The article is from

the American magazine “New World Review”, August, 1962.

2 the Arctic Circle—Северный полярный круг

3 distance ['distans]— расстояние

« ... felt *a little frost-bite* — ... почувствовал, что немного отморозил

ноги (‘frost-bite’—букв.: «укус мороза»)

saving his life, and they must act immediately. General sepsis.1

Volodya was taken to the hospital, and the struggle for his life

began.

There were more operations after the first one. Pevek is a lit-

tle town and soon everybody knew about Volodya. The doctors,

the hospital people, and many people in Pevek gave their blood1 2

for Volodya Everybody came to Volodya’s mother to ask what

they could do to help They brought fruit, vegetables and all kinds

of delicacies that were hard to get in Pevek. Volodya did not die,

thanks to the blood that people from all over the town gave. But

he was getting weaker and weaker.

A terrible night came when the doctors saw that they could do

nothing more to save his life. A radio SOS was sent to the chief

doctor3 in Magadan, Dr Obikhodov. He came himself, by a spe-

cial plane. He stayed a week at the hospital and then said that

the only hope was to take Volodya to Moscow. Volodya under-

stood how bad things were, but he never stopped fighting for his

life.

“So now,” his mother writes, “1 had to take my dying son on

a journey of almost eight thousand miles. How could we move

him? But in this too, I wasn’t friendless. Comrade Burkhanov,

chief of the Transport Service, arranged for a special fast plane.

For the journey from the hospital to the airdrome, they made a

special transport—a big sledge with a special bed in it, pulled

by a tractor. On the way to Moscow, doctors came to the plane at

every stop to take care4 of Volodya.”

In Moscow, Volodya was taken to the Botkin Hospital, where

Dr. Anna Savchenko, the famous specialist, began a new struggle

for Volodya’s life, a hard struggle that lasted two long years. At

last, the danger passed. Volodya could sit up in bed, and then

stand, and then move about slowly. He began to make plans for

his future.

All his life he had dreamed of becoming a radio engineer But

how could he go to school? He still walked with great difficulty.

“And in this too, we found good-hearted people who didn’t allow

us to fight alone,” Volodya’s mother writes

“Nikolai Blagushin, a teacher of Moscow School No. 26, gave

all of his free time to help Volodya to finish the ten-year school.

Then the teachers and professors of a Leningrad engineering col-

lege united their efforts to help Volodya. He has just passed his

fourth-year examinations. He has one more year to study.”

1 general sepsis ('djenaral 'sepsis]—общее заражение крови (при неко-

торых случаях обмораживания протекает в течение довольно длительного

времени без каких-либо внешних признаков)

2 blood [blxd] — кровь

* the chief ltfi:f] doctor—главный врач

4 to take care [kea]—эд осмотреть, оказать помощь

26

Next year, Volodya hopes to pass his last examinations, and

to receive the diploma of radio engineer. Let us wish him every

success!

Exercises

1. Give as many facts as you can to prove the following:

1. Many people in Pevek tried to help Volodya.

2. Everybody tried to make Volodya’s journey to Moscow

as comfortable as possible.

3. The struggle for Volodya’s life was hard and long.

4 Volodya will become a radio engineer.

11. Discuss the following questions.

1. Why did the author find it important to describe the

geographical (dsia'graeftkl] situation of the town of Pevek?

2. Why didn’t Volodya die?

III. Speak about Burak’s picture “A Visit”.

a) Describe the picture (say what you see in the picture).

b) Say what each of the girls will do after the visit.

27

IV. Translate in writing at home, using a dictionary.

ON THE ENGLISH CLIMATE

Almost twenty million people (two-fifths) of the whole popu-

lation of England live in seven large, densely populated cities.

London, the largest of them, has a population of eight million,

and most Londoners still have open fireplaces in which they use

coal. The result is that there is a tremendous concentration of

smoke and soot in the air. The smoke not only absorbs part of

the sun’s rays, but promotes the formation of denser and heavier

fogs. That explains why the well-known English fogs are seen

more often in densely populated cities. Very often, while a heavy

fog hangs over a big English city for days, only a few miles

away in the country, the sky may be cloudless and the sun

shining brightly.

The average winter temperature varies between —3° and —7°.

Snow does not cover the ground very long, except on the moun-

tains. The cold air, which comes to England from the continent,

becomes not only damper as it moves over the North Sea, but

warmer, and it melts the snow.

Towards spring, cold masses of air from the Arctic may

attack England, and in April there are sure to be snowfalls some-

where in England.

The English climate is so changeable that when English

people make plans for vacations or trips, they usually begin,

“If the weather...”

LESSON FIVE

Exercises

I. Say what sports you go in for now, and what you went in for in the

past. Use the phrase

When I was ... years old, 1 ...

II. Speak about the sports you went in for last summer or last winter.

Say where you used to go, how long you used to play games (swim,

fish, etc.} and what you used to do afterwards.

III. Say what sport you like to watch. Say something about an interesting

event that you saw in this kind of sport. If you know, say who the

Soviet Union champion and the world champion is in this kind of

sport. Look at the names of different kinds of sport events given here:

basket-ball game; water-polo game; volley-ball game;

hockey game; tennis match; boxing match; football match;

figure-skating competition; swimming competition; gymnas-

tics competition; racing competition; chess tournament.

Example: I like to watch ski-jumping.

I saw an interesting ski-jumping competition

last (this) winter.

... is the Soviet Union ski-jumping champion.

IV. Study the examples:

A: I like camping out.

B: So do I.

A: I don’t play tennis well.

B: Neither do I.

After each sentence use the phrase

So do (did, am, shall, have) I;

Neither do (did, am, shall, have) I.

1. I used to go in for volley-ball.

2. I don’t play volley-ball so often now.

29

3. I haven’t seen a good football game for a long time.

4. I don’t like to watch table-tennis games on TV.

5. I am not good at figure-skating.

6. I want to see some tennis matches next summer.

7. I shall go in for sports as much as I can.

8. I have read about the match in the newspaper.

9. I was never a good speed skater.

V. Do the same as you did in Exercise IV (page 29) nd add another

sentence, as in the example:

Example:

A: 1 want to go to a football match this Sunday.

B: So do 1. Do you know where I can get a ticket?

1. 1 want to go to a volley-ball game this Sunday.

2. If it doesn’t rain, we shall go swimming.

3. One of my friends wanted to become a chess champion.

4. We used to play hockey very often.

5. I didn’t go skating very often last winter.

VI. Study the meaning and use of the new words as seen in the following

examples:

well-known: Cherkasov was a well-known actor. The novel

“War and Peace” by Lev Tolstoy is well known all over

the world. These facts are well known to everybody. It

is well known that...

to be (get) excited: She was so excited that she couldn’t

speak. Everybody was excited by the news. We shall

speak about it when you are less excited. He got excited

when he saw the letter.

fan: There are many football fans in our class. Most of

them are Spartak fans. I am a tennis fan, and I try to

see all the most important tennis matches.

to hold (held, held): Hold my watch for me, we are going

to have a volley-ball game. The girl returned holding

some plates in her hands. She held her little brother by

the hand.

member: The members of our English club have pen-friends

in Great Britain and Australia. I’d like to become a

member of the school hockey team.

speed: The car was moving at high speed. They were driv-

ing at a speed of 120 kilometres an hour. Lydia Skobli-

kova was the 1964 Winter Olympics speed-skating cham-

pion. The train was going at full speed.

30

to seem: It seems to me that you are wrong. The exami-

nation seemed very difficult to him. He seemed (to be)

surprised. He did not seem (to be) excited at all.

The girl didn’t seem to like the lunch; she didn’t eat any-

thing.

to wear (wore, worn): He was wearing his best suit. The

girl wore a black dress and seemed much older than

she really was. She enjoyed wearing her new winter

coat.

to be about: I was about to leave the house when the

telephone rang. He was about to agree, but suddenly

changed his mind.

VII. a) Say what they are wearing and why:

b) Say what you usually wear: 1) at school, at home; 2) in summer,

in winter.

VIII» Complete the following sentences in as many ways as you can;

1. I was about to ... when ...

2. It seems to me that ...

3. It is well known that ...

31

IX. Say what they are holding and why:

X. Guess the meaning of the italicized words; pronounce them correctly.

A. I. Sports are very popular ['popjula] tn our country.

2. Now we can watch many international [^nta'naejnal]

matches on TV.

3. Petrov came to the finish line ten seconds before his

nearest opponent [a'pounant].

В. 1. The class was so excited by the news that their school

team had won that the beginnieig of the lesson was

very noisy. A group of excited children, holding books

and flowers, gathered round their form mistress. It

was a very exciting match. There was much noise

and excitement at the meeting.

2. He is very ill; the doctors say that his life is in

danger. Crossing the street is dangerous when cars

are moving fast from all sides.

3. He said he wasn’t interested in the match though the

game itself was interesting to him. He said he had

lost interest because the game was too slow.

4. It was impossible to return in time because the train

was late. Please be ready at six o’clock if possible.

C. 1. November 7, 1967 is the fiftieth anniversary [,aem-

'vaisari] of the Great October Socialist Revolution.

32

2. If a player in a hockey game breaks a rule [ru:l], he

is not allowed to play for two minutes.

3. The train went back about two hundred metres and

then began to move forward ['fo:wad] again.

4. Each player won five games: the chess tournament

ended in a draw.

5. Some of Gorky’s letters were found not long ago and

were published ['рлЫф] in “Literaturnaya Gazeta”.

XI. Discuss the translation of the following sentences:

I. People in those days enjoyed their ball games and

got as excited about a game as they do now.

2. Nobody was allowed to play ball games.

3. The rules fixed the number of men on a team.

4. In 1909, the goal-keeper began to wear clothes of a

different colour from that used by the other members

of his team

5. The rules were changed again and again.

6. The new rule made it possible to stop any attack.

7. The game was becoming less interesting, and people

seemed to be losing their interest in it.

8. Football began to be played in Russia at the begin-

ning of the twentieth century.

XII. Read the text “One Hundred Years of Football** at home, giving special

attention to the following words:

a) a purpose, to interfere, a laws

b) to be (get) excited, to seem, to be about, to end in a

draw, forward, a rule.

Prepare to answer the questions in Exercise XI11 (page 36).

ONE HUNDRED YEARS OF FOOTBALL

We say that 1963 was the one-hundredth anniversary of foot-

ball, but the game is really much older Games with a ball were

well known hundreds of years ago. “Harpastum”, the Roman1

game, that was brought to Gaul1 2 * by Caesar’s legions,8 the French

game of “Soult”, Georgian4 “Lelo”, Russian “Shalyga” and “Kila”,

and many others were all forms of ball games. “Kemari”, one of

1 Roman ('rouman]— римский

2 Gaul [go:l]— Галлия (древнее государство, находившееся на террито-

рии современной Франции)

’Caesar’s legions ['st гэг 'Udsanzj — легионы (Юлия) Цезаря

4 Georgian ['(^эхЭДап) — грузинский

33

1679. England vs.1 Scotland.

the oldest of these games, was played 1,400 years ago and is still

played in Japan? Football fans saw “Kemari” at the 1964

Olympic Games in Tokyo.

These ball games were not played in stadiums or on football

fields. They were played in the squares and streets of cities and

villages, and they were very dangerous to the windows and doors

of the houses.

People in those days enjoyed their ball games and got as

excited about a game as they do now. Young workmen used to

leave their work to take part in a game. At the beginning of the

seventeenth century, special laws were made against playing ball

games. Nobody was allowed to play, and for two hundred and

fifty years, there were no games.

People began to play again in the second half of the nine-

teenth century. In 1863, a meeting was called in a tavern in

Great Queen Street, London, for the purpose of deciding the rules

of the game. There was much excitement at this meeting. Shouts

of “Only feet!” came from one end of the hall; “Hands and feet!”

came from the other end. At last, when the “hands and feet"

group saw that they could not win, they left the hall. The meet-

ing then became quieter, and thirteen rules of football were intro-

duced. They were published in December, 1863, and later became

the international rules of the game all over the world.

* vs. — сокр. от versus (against)

8 Japan [dja'paen]—Япония

34

The rules fixed the number of men on a team: a goal-keeper,

one full-back, one half-back and eight forwards.1 Only the goal-

keeper could hold the ball in his hands. The sound of the refe-

ree’s whistle1 was heard for the first time in 1878. Before that

time, the referees shouted to the players, made signals with their

arms or used a school bell.

The goal,1 as we see it today, was introduced in 1891. The

same year saw the introduction of the eleven-metre penalty kick.1

At first, the goal-keeper was allowed to move forward six metres

in front of his goal. He could move and jump from side to side

to try to interfere with the player wrho was about to make the

penalty kick. But a rule was introduced which did not allow the

goal-keeper to move towards the player or from side to side

before the penalty kick was made. In 1909, the goal-keeper began

to wear clothes of a different colour from that used by the other

members of his team.

The rules for “out of play”1 were changed again and again.

At first, the rule did not allow a player to pass the ball1 to

a man in front of him. Later, the rule was changed: a player

was “out of play” if there were less than three opponents in front

of him at the moment when he passed the ball to another

member of his team. This new rule made it possible to stop any

attack. One of the backs could move forward, leaving only the

other back and the goal-keeper in front of the attacking team.

The forwards of the attacking team were then “out of play” and

the referee’s whistle stopped the game. It became more and more

difficult to make a goal. More and more often, games ended in

a draw — 0-0;1 2 the game was becoming less interesting, and people

seemed to be losing their interest in it.

In 1925, the rule was changed again for the last time. Now,

a player is “out of play” if there are less than two (not three)

opponents in front of him at the moment when he passes the

ball. Since 1925, no important changes have been made in the

rules of football.

Football began to be played in Russia at the beginning of

the twentieth century. The game was not very well known then, but

after the Great October Socialist Revolution, it became more and

more popular. Today, football is the favourite sport of millions

of people in our country, and Soviet football teams take part in

international matches all over the world.

1 Some football terms: goal [goul]— 1) ворота; 2) гол; goal-keeper f'goul-

ktpa]—вратарь; 'full-back—защитник; 'half-back—полузащитник; forward

['fa:wad] — нападающий; penalty ['penlti] kick—пенальти (одиннадцатимет-

ровый штрафной удар); out of play—вне игры, to pass the ball—переда-

вать мяч; referee’s whistle (,refa'rfcz 'wislj—свисток судьи

2 Read: nothing to nothing

35

XIIL Answer the questions:

1. Why do we say that 1963 was the one-hundredth anni-

versary of football?

2. Why were ball games not always allowed by law?

3. When were the rules of football published? How many

rules were there?

4. Have the rules of the game always been the same since

they were introduced?

5. When was football first played in Russia?

6. What can you say about Soviet football teams?

XIV. Re-read the first four paragraphs of the text “One Hundred Years of

Football”. Then:

a) Find the most important sentence or sentences in each paragraph.

b) Give the idea of each paragraph in as few words as possible.

c) Write down the best variant.

XV. Speak about the last football (hockey, etc.) game you went to or

watched on TV. Say if you like this kind of sport, if you go in for it

yourself or are only a fan, what teams played, who won the game and

what the score was.

XVI. Tell what happened one summer day to the boys living in our yard.

You may need the word: спасательный круг — life-buoy f'laifboi].

THEORY AND PRACTICE

(by Y. Cherepanov)

XVII. Speak about Fattakhov’s picture “Fans” (page 37).

a) Say if you ^ee a town or a village in the picture, and why you

think so.

b) Describe the two boys. (Say how old they are, what they are wear-

ing, which boy is holding a hockey-stick.)

c) Say what the boys did before the moment you see them in the

picture.

d) Speak about the game the boys are watching. (What kind of game

it is, where it is being played, how the boys’ favourite team is

playing, why the boys are so excited, etc.)

36

Homework

I.* Copy the following sentences. Use the verb in the margin in the

proper form.

I ... to see Helen at the stadium yes-

terday. It always ... to me that she

didn’t like football. But when I ... how

excited she ... when one of the teams ...

to be losing, 1 ..., “I ... wrong — Helen

is a real football fan.”

I ... about to ask her which team ...

a better chance of winning, when she

suddenly ... to me and ..., “Tell me why

one member of the team ... different

clothes? And why doesn’t he help the other

players on his team?”

to be surprised

to seem

to see

to become, to seem

to think, to be

to be, to have

to turn, to say

to wear

II.* Do Exercise XII (page 33).

37

Hi.* Find English equivalents in the text for the following and write

them out:

сотая годовщина футбола; с целью установить правила

игры; они были опубликованы в декабре 1863 года; оканчи-

вались вничью; принимают участие в международных

матчах; двигаться вперед; правило было изменено; спе-

циальные законы против игры в мяч; мешать игроку.

IV.* Say which of the dictionary meanings given here are illustrated in the

following sentences:

interfere [,mta'fia] о 1) мешать; служить помехой, препятствовать;

2) вмешиваться (in); 3) сталкиваться (with).

law [b:] п 1) закон; правило; 2) право; юриспруденция; internation-

а1~международное право; 3) профессия юриста; 4) суд, судебный

процесс; 5) attr. законный; юридический; правовой

1. Sometimes, his interest in sports interfered with his studies.

Don’t interfere in their discussion, they are specialists

2. Newton formulated the law of gravity ['gtaevitij.

Have you ever read “The Law of Life” by Jack London?

At that college, students must take examinations in inter-

national law.

Lenin studied in the law department at Kazan University.

V .* Prepare for a dialogue in class. Think of what you can tell your class-

mates about your favourite sport and what you can ask them on the

subject.

VI .* Read the story “The Blue Patch” in Lesson Six without using a dic-

tionary. Prepare to answer the questions given before the text.

anniversary n

fan n

forward adv

hold (held, held) v

interfere v

international a

law n

match n

member n

neither adv

publish v

purpose n

rule n

seem v

speed n

wear (wore, worn) v

well-known a

be about

be (get) excited

end in a draw

38

LESSON SIX

Questions:

1. Why did Jackie decide to go to the races?

2. What place did Jackie take:

a) in the first race?

b) in the thread-and-needle race?

c) in the wheelbarrow race?

THE BLUE PATCH1

By D. Bateson

“Ma,” said Jackie, “when can I have those new trousers?” She

did not look up from her sewing. “When your father gets a job,”

she said at last. “In October, perhaps.”

Jackie ran out into the street. He threw his ball at the wall

of the house and caught it again. October ... he had to wait

three months before he could say good-bye to the blue patch in

his trousers. And everybody could see the patch. Penny Dale,

the girl who lived on the hill, could see it too.

Jenner came up the street and asked, “Going to the races,1 2 3 * 5

Jackie?”

Jackie threw his ball at the wall again. “No, I don’t think

so,” he said.

“There are prizes,” Jenner said. “Seven and six and half a

crown8 for first and second places.”

Jackie thought: “If I win a first prize, 1 can buy those trou-

sers myself. Then Ma won’t have to worry.”

“I’d like to go,” he said. “How much do you have to pay to

take part in the races?”

“Only sixpence,” Jenner said.

“Only!” Jackie said “And where can I get sixpence?”

“I’ll give you threepence for that ball.”

“But I need sixpence!”

“— And another threepence for your knife,” Jenner said.

1 a patch Ipaetf] —заплата

2 Going to the races? (разг.)=Are you going to the races?

3 seven and six = seven shillings and sixpence. British money: a pound

(£|) = 12 shillings (12s); one shilling (Is) = 12 pennies (12d); one crown =

5 shillings; a half-crown=2 shillings sixpence (2s 6d)

39

Jackie thought about it, but not long. Ten minutes later, they

were on their way to the races, Jenner wearing his new white

shirt and white trousers, Jackie in his old shirt and brown trou-

sers with the blue patch.

For many weeks, Jackie had thought ot going in for some-

thing—just for the idea of winning. But he had not, because of

the patch He didn’t want to show all the other boys and girls

the blue patch in his trousers. But how could he get rid of1 the

patch if he didn’t run? When the man shouted, “First race — boys,

seventy yards,” Jackie gave h»m his sixpence and went to stand

in the starting-line with the other boys.

He tried too hard at the beginning of the race, and couldn’t

make his legs go fast enough at the end. But he won second

place, with Jenner just behind him, and the man gave him half

a crown.

Next was a thread-and-needle race. Jackie wanted Penny Dale

for a partner, but a girl named Helen took his arm, and they

went together to the starting-line. Jackie saw Penny Dale near

him, with Jenner. Helen went to the end of the field and held

her needle ready. Jackie put the piece of thread into his mouth,

and when the man shouted “Go!”, he ran like the wind towards

Helen. He was the first boy to get to his partner. But he was

so excited that his hands were shaking, and he had difficulty

threading the needle.

“How slow you are!” Helen said, waiting to run back to the

starting-line with her threaded needle.

The other pairs threaded their needles quickly, and the girls

ran back. Penny was second. Helen was last. When Jackie re-

turned slowly with his hands in his pockets, Helen didn’t look

at him. She walked away without a word.

Jackie’s last chance for a big prize was the wheelbarrow1 2 race.

You had to run on your hands in the wheelbarrow race; a girl

behind you held your legs and pushed you. But now nobody, he

thought, wanted to be his partner Nobody wanted to help him

to get the money for those new trousers.

So that was how Penny Dale saw him looking unhappy and

alone.

“Would you like to help me?” she asked.

His eyes became bright, but he said, “You can have anyone

for a partner.”

“I don’t want anyone,” she answered. “I’d like to have you.”

His heart was full of joy, but he thought of Penny behind

him and of the blue patch in his trousers. “I can’t,” he said.

“I’m no good at sport.”

1 to get rid of — избавиться от

2 a wheelbarrow ['wi:l,baerouj — тачка

40

“Please, Jackie!” she said. "Look, they’re about to start ” And

she pulled his hand

He tried again as they moved towards the line. “I have never

won a first prize.”

But Penny didn’t answer. They were in the line now, and she

took his legs and he heard the man’s voice: “Ready? Go!”

Jackie forgot his purpose in coming to the races. He stopped

thinking about Ma, and Jenner, and Helen. He even stopped

thinking about the prizes. He could only think of the blue patch

in his trousers that Penny could see. He ran forward on his

hands. He only wanted to get to the end of the field as quickly

as possible, to give Penny less time to look at that patch. He

ran on and on, and didn’t see that now all the other pairs were

behind them. But he saw the white finish line. When they came

to the end of the field, he ran across the white line and fell

down.

“We won, Jackie, we won!” Penny cried as she sat down near

him on the grass.

And he saw that there was only admiration* in her eyes.

Exercises

I. Answer the questions:

I. Why did Jackie change his mind about going to the

races?

2. How did he get the money he needed to enter the races?

3. What shows that Jackie was a good runner?

4. What are the rules of a thread-and-needle race and of a

wheelbarrow race?

5. What prizes did Jackie win?

11. Answer the foliowing questions. Give tacts from the story to support

your answers

1. In what season were the races held?

2. Did the idea of winning some money come to Jackie

only that day?

3. Was Jackie a better runner than Jenner?

4 How many races did Penny take part in? What prizes

did she win?

5. Why did Penny invite Jackie to be her partner in the

wheelbarrow race?

1 admiration hadmrreijn]—восхищение

41

111. Speak about the picture. You may need the words: to break (broke,

broken)—разбивать; to take a picture (of) — фотографировать.

IV. Translate orally in class:

1. It was the Russian scientist Ladygin who made the first

electric lamp.

2. it was the Russian traveller Miklukho-Maklai who studied

the life of the Papuans ['paepjuanz],

3. It was not until 1863 that the rules of football were

introduced.

4. It was in the South Sea islands that Jack London found

material for some of his best stories

V. Translate in writing al home, using a dictionary.

MAGIC TABLETS

In their first match against Sweden’s champion football team,

the Dynamo footballers won by a score of five to one. It was

their speed of play that brought the Soviet team their victory,

and Swedish experts wondered how the Russian players could

maintain such high speed.

42

A reporter who entered the Dynamo dressing-room during the

interval made a sensational discovery. The Russians, he said,

drank tea and lemon; and at the same time, they sucked some

kind of white tablets. The newspapers had no doubt that it was

these white tablets that gave the players the strength to maintain

their high speed of play. A Swedish firm began to sell so-called

“Dynamo Tablets” which, they said, would improve a footballer’s

game immediately. But it was soon proved that the firm’s tablets

were simply—sugar.

It cannot be said, however, that the firm was trying to deceive

people. It is quite possible that the Dynamo players drank their

tea, as some Russian people like to do, holding the piece of sugar

in their mouth.

LESSON SEVEN

Exercises

1. Speak about a book you read not long ago. Say who the book is by,

what it is about and who it is about.

11. Say something about a book that helped you to decide what your pro-

fession will be, or that interested you in some profession.

111. Speak about the kind of books you used to read when you were much

younger.

IV. Speak about a book you would like to read, and why you have not

read it yet.

V. Say something about an author whose books you like. If you know,

say what autobiographical material can be seen in his books.

VI. Make up dialogues on the following situation. Somebody tells a friend to

read a book (or a story). The friend has not read the book, but he

has seen a screen version (or an adaptation for the stage).

VII. Study the meaning and use of the new words as seen in the following

examples:

exhibition, Towards the end of the school year, we usual-

to exhibit, ly arrange an exhibition of the pupils’ work

art, at our school. Every pupil has the right to take

a painting, part in the exhibition.

especially, The pupils exhibit many useful things made

to paint: in their workshops. Beautiful needlework and

handicraft work are also exhibited. In one of

the rooms, we usually have a real art exhibition. Photographs,

drawings and paintings are exhibited.

We are especially proud of our school artists. Some of

them draw and paint beautifully and—who knows? —

perhaps some day they will be famous painters.

hobby: My hobby is collecting stamps. What’s your hobby?

He’s not really an artist, painting is only his hobby.

My sister has two hobbies—speed-skating and book-

binding.

foreign: I’d like to know two or three foreign languages.

Many foreign visitors come to our country every year.

to refuse: He refused to answer our questions. She refused

our help. I had to refuse because I had no time.

war: “War and Peace” by Lev Tolstoy. The war began

(ended) in ... To lose (to win) a war. We don’t

want war.

44

to lead (led, led): 1) She led the child by the hand. The

door leads into the hall. This street leads to the square.

2) The Soviet Union leads the struggle against war for

peace all over the world. Harry Pollitt was a well-known

leader of the English working-class movement.

to create: Shakespeare ['Jeikspia] created plays that will

never die. Scientists have created new synthetic materials.

courage: 1 hadn’t the courage to tell her the truth. Don’t

lose courage!

Vlil. Make sentences (orally) using the following word combinations:

1 foreign stamps; foreign languages; foreign countries;

2. at an art exhibition; to go to an industrial exhibition;

an exhibition of synthetic materials;

3. to lead somebody; to lead out of...; to lead into (to)... .

IX. Say: a) why you had to refuse something (or refuse to do something);

b) why you hadn’t the courage to do something, as shown in the

examples.

Examples: Tony invited me to see the exhibition of children’s

books, but I had tickets to the theatre for the

same day. So I had to refuse.

1 wanted to go swimming, but I hadn’t the courage

to jump into the cold water.

X. Translate the italicized part of the sentence.

I. / want you to interfere and stop the game —it has become

too noisy.

2. I don't want you to move the things on my table.

3 Would you like me to speak to him for you?

4. Do you want us to give him your telephone number?

5. The father wanted his son to enter a technical college.

“Td like you to be a good engineer,” he used to say.

REMEMBER!

I’d like

They want

him

us

them

etc.

to do something

XI. Ask your classmates to do something. Use the phrases:

I’d like you to ...

I want you to ...

45

XII. Guess the meaning of the following words; pronounce them correctly.

A. 1 Van Cliburn ['van 'klaiba:n] is one of the best-known

American musicians [mju:'zijanz] today.

2. I have always liked the work of Sergei Konyonkov,

the well-known Soviet sculptor f'skAlpto].

3. Workers in capitalist countries have to fight for their

political [pa'htikal] rights.

4. “Komsomolskaya Pravda” has its own correspondents

[,kons'pondants] in many cities.

5. Progressive [pra'gresiv] people all over the world

are uniting their efforts in the struggle against

war.

6. At the end of the school year we discussed the work

of our English club at a special conference ['konfaransj.

В. 1. We must buy white paint for the windows and green

paint for the doors.

2. Repin was the leading painter of the beginning of

the 20th century. The smaller boys all wanted to sit

near the pioneer leader. A great revolutionary leader.

A leader of the proletariat.

3. Thousands of Young Communists fought courageously

[ka'reidjasli] against the fascists.

C. 1. We decided to give her a new ski suit as a gift for

her birthday.

2. The little bird couldn’t fly because its wings were

not yet strong enough.

3. The day of the international tennis matches will be

announced [a'naunst] over the radio.

4. All the land in our country belongs [bi'lorjz] to the

people.

XIII. Discuss the translation of the following:

1. Works of art; a Peace Prize.

2. “Painting pictures, making drawings—the creation of art

in any form has been to me a form of speech.”

3. “All art belongs to those who love it most, and 1 want

the Soviet people to have all of my life’s work that is

still in my hands.”

4. “The Soviet people’s call for world disarmament in the

United Nations is perhaps the greatest peace act in all

history.”

5. The purpose was to announce the news of Rockwell Kent’s

gift to the Soviet people.

6. “... seven years ago, that is what I did.”

7. “But the fact is, that a great many people in America

do care.”

46

8. ... the United States today has turned its face against

beauty as an important part of life.

9. To many parents in America painting and writing seem

good as hobbies and entertainment, but for real life, they

want their children to be engineers, businessmen, bankers

and technicians.

10. "... an American artist must have courage to be true

to his art, and must have greater courage to do anything

that those in power in America do not like.”

XIV. Read the text “Rockwell Kent’s Gift” at home, giving special attention

to the use of the following words:

a) an entertainment, speech, creation, disarmament, reality,

respect;

b) art, especially, to refuse, a hobby, to belong.

Prepare for classroom discussion of the questions in Exercise XV

(page 49).

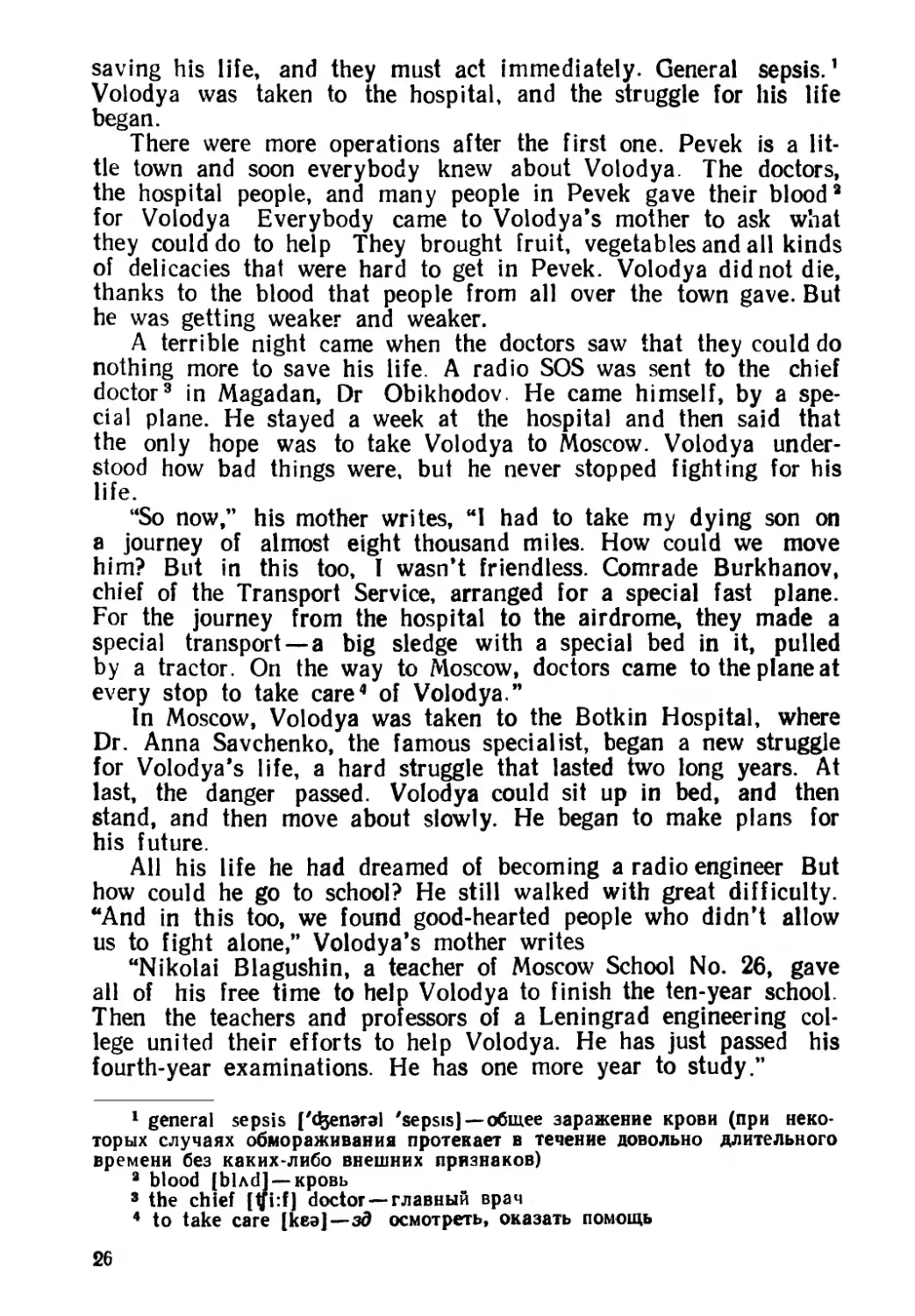

ROCKWELL KENT’S GIFT

In 1961, Rockwell Kent, the famous American artist and

writer, decided to give his whole collection of paintings, drawings

and books to the Soviet people. There are more than eighty

paintings, eight hundred drawings and other works of art in the

collection.

In a letter that he wrote about his gift to the Union of

Soviet Societies for Friendship and Cultural Relations with

Foreign Countries,1 Mr. Kent said, “Three years ago, there

was an exhibition of my work in the Soviet Union. The

pictures were exhibited in many cities, and everywhere the

people showed the greatest interest in them, much more interest

than American artists receive in their own country. Painting

pictures, making drawings — the creation of art in any form has

been to me a form of speech I have tried to find understanding

and friends through my form of speech. Your people have given

me that understanding and friendship; they have become my

people and my friends. All art belongs to those who love it most,

and I want the Soviet people to have all of my life’s work that

is still in my hands.

For years, the Soviet government has given prizes to those

men and women in all countries whose service to world peace

has been the greatest. The Soviet people’s call for world disar-

mament in the United Nations is perhaps the greatest peace act

1 the Union of Soviet Societies [sa'saiatiz] for Friendship and Cultural

I'kAltfaral] Relations [n'leijnz] with Foreign Countries—Союз Советских

обществ дружбы и культурных связей с зарубежными странами

47

in all history. I want to give my

work to the Soviet people as a

prize — a Peace Prize. 1 know that

this “prize” for such an act is small —

too small, but it is all that I have

to give. Please, take it. It comes from

my heart.”

The Ministry of Culture1 of the

U.S.S.R. invited Soviet and foreign

correspondents to a press conference.

The purpose was to announce the

news of Rockwell Kent’s gift to the

Soviet people. All the American cor-

respondents in Moscow and correspond-

ents of the international news service

were present. One American corre-

spondent asked Rockwell Kent why he

had not presented his work to the

American people, why he had not asked an American museum

to take his pictures

“My answer is,” Mr. Kent explained, “that seven years ago,

that is what I did.” Rockwell Kent had spent the best years of

his youth in Maine,1 2 and he asked the Farnsworth Museum in

Rockland, Maine, to take his collection. The director of the

museum said that they would be glad to receive such a wonderful

collection. He said that the museum would build another wing,

especially for Mr. Kent’s collection. But just after that time

Rockwell Kent was called to Washington by the McCarthy

Committee3 to answer questions about his political ideas.

Rockwell Kent said that the committee had no right to ask such

questions and refused to answer them. Immediately after that,

the Farnsworth Museum refused to take his pictures.

The conference lasted two hours, and the correspondents

showed great interest in it, especially the American correspond-

ents. But the American newspapers published very little about

Rockwell Kent’s gift. One Western newspaper4 wrote only a few

words: “We have heard that artist Rockwell Kent, who uses a lot

of red paint in his pictures, has given many paintings to Russia.

What we have to say is — who cares?”5

“But the fact is. that a great many people in America do

1 the Ministry of Culture ['kAltfa]

8 Maine [mein] — a northeast state of USA

3 the McCarthy Committee [тэ'ка01 ka'miti]

4 one Western newspaper = a newspaper in one of the western states

of the USA

5 who cares? — зд. ну и что (из этого)? кого это интересует (волнует)?

(to саге—интересоваться)

48

care,” the progressive magazine “New World Review” wrote.

"People who are tired of the cold war and who hope for peace

and friendship understand the purpose of Rockwell Kent’s gift

and are happy about it ”

The well-known American historian, writer and Negro leader

Dr. Du Bois’ wrote that the United States today has turned its