Автор: Fairbank J.K. Twitchett D.

Теги: history cambridge history of china

ISBN: 978-0-521-24332-2

Год: 2007

Похожие

Текст

THE CAMBRIDGE

HISTORY OF

CHINA

VOLUME 7

THE MING DYNASTY

1368-1644

PART 1

THE CAMBRIDGE HISTORY

OF CHINA

General Editors

Denis Twitchett and John K. Fairbank

Volume 7

The Ming Dynasty, 1368—1644, Part I

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Work on this volume was partially supported by the National Endowment for the

Humanities, Grant RO-20431-83.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

THE CAMBRIDGE

HISTORY OF

CHINA

Volume 7

The Ming Dynasty, 1368—1644, Part I

edited by

FREDERICK W. MOTE and DENIS TWITCHETT

Cambridge

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao Paulo

Cambridge University Press

32 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10013-2473, USA

www.cambridge.org

Information on this title:www.cambridge.org/9780521243322

© Cambridge University Press 1998

This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception

and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements,

no reproduction of any part may take place without

the written permission of Cambridge University Press.

First published 1998

Reprinted 1990,1997, 2004, 2007

Printed in the United States of America

A catalogue recordfor this publication is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-0-521-24332-2 hardback

Cambridge University Press has no responsibility for

the persistence or accuracy of URLs for external or

third-party Internet Web sites referred to in this publication

and does not guarantee that any content on such

Web sites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE

When The Cambridge History of China was first planned, more than two

decades ago, it was naturally intended that it should begin with the very

earliest periods of Chinese history. However, the production of the series

has taken place over a period of years when our knowledge both of Chinese

prehistory and of much of the first millennium B.c. has been transformed

by the spate of archeological discoveries that began in the 1920s and has

been gathering increasing momentum since the early 1970s. This flood of

new information has changed our view of early history repeatedly, and there

is not yet any generally accepted synthesis of this new evidence and the

traditional written record. In spite of repeated efforts to plan and produce a

volume or volumes that would summarize the present state of our

knowledge of early China, it has so far proved impossible to do so. It may

well be another decade before it will prove practical to undertake a synthe¬

sis of all these new discoveries that is likely to have some enduring value.

Reluctantly, therefore, we begin the coverage of The Cambridge History of

China with the establishment of the first imperial regimes, those of Ch'in

and Han. We are conscious that this leaves a millennium or more of the

recorded past to be dealt with elsewhere, and at another time. We are

equally conscious of the fact that the events and developments of the first

millennium B.C. laid the foundations for the Chinese society and its ideas

and institutions that we are about to describe. The institutions, the literary

and artistic culture, the social forms, and the systems of ideas and beliefs of

Ch'in and Han were firmly rooted in the past, and cannot be understood

without some knowledge of this earlier history. As the modern world grows

more interconnected, historical understanding of it becomes ever more

necessary and the historian's task ever more complex. Fact and theory affect

each other even as sources proliferate and knowledge increases. Merely to

summarize what is known becomes an awesome task, yet a factual basis of

knowledge is increasingly essential for historical thinking.

Since the beginning of the century, the Cambridge histories have set a

pattern in the English-reading world for multivolume series containing

chapters written by specialists under the guidance of volume editors. The

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

VI

GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE

Cambridge Modern History, planned by Lord Acton, appeared in sixteen

volumes between 1902 and 1912. It was followed by The Cambridge Ancient

History, The Cambridge Medieval History, The Cambridge History of English

Literature, and Cambridge histories of India, of Poland, and of the British

Empire. The original Modern History has now been replaced by The New

Cambridge Modern History in twelve volumes, and The Cambridge Economic

History of Europe is now being completed. Other Cambridge histories in¬

clude histories of Islam, Arabic literature, Iran, Judaism, Africa, Japan,

and Latin America.

In the case of China, Western historians face a special problem. The

history of Chinese civilization is more extensive and complex than that of

any single Western nation, and only slightly less ramified than the history

of European civilization as a whole. The Chinese historical record is im¬

mensely detailed and extensive, and Chinese historical scholarship has been

highly developed and sophisticated for many centuries. Yet until recent

decades the study of China in the West, despite the important pioneer

work of European sinologists, had hardly progressed beyond the translation

of some few classical historical texts, and the outline history of the major

dynasties and their institutions.

Recently Western scholars have drawn more fully upon the rich tradi¬

tions of historical scholarship in China and also in Japan, and greatly

advanced both our detailed knowledge of past events and institutions, and

also our critical understanding of traditional historiography. In addition,

the present generation of Western historians of China can also draw upon

the new outlooks and techniques of modern Western historical scholarship,

and upon recent developments in the social sciences, while continuing to

build upon the solid foundations of rapidly progressing European, Japa¬

nese, and Chinese studies. Recent historical events, too, have given promi¬

nence to new problems, while throwing into question many older concep¬

tions. Under these multiple impacts the Western revolution in Chinese

studies is steadily gathering momentum.

When The Cambridge History of China was first planned in 1966, the aim

was to provide a substantial account of the history of China as a benchmark

for the Western history-reading public: an account of the current state of

knowledge in six volumes. Since then the outpouring of current research,

the application of new methods, and the extension of scholarship into new

fields have further stimulated Chinese historical studies. This growth is

indicated by the fact that the history has now become a planned fifteen

volumes, but will still leave out such topics as the history of art and of

literature, many aspects of economics and technology, and all the riches of

local history.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GENERAL EDITORS’ PREFACE

The striking advances in our knowledge of China’s past over the last

decade will continue and accelerate. Western historians of this great and

complex subject are justified in their efforts by the needs of their own

peoples for greater and deeper understanding of China. Chinese history

belongs to the world not only as a right and necessity, but also as a subject

of compelling interest.

JOHN K. FAIRBANK

DENIS TWITCHETT

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

General editors’ preface

List of maps and table

Preface to Volume 7

Acknowledgments

List of abbreviations

Ming weights and measures

Genealogy of the Ming imperial family

Ming dynasty emperors

Introduction

by Frederick W. Mote, Princeton University

page v

xiii

xv

xviii

XX

xxi

xxii

xxiii

1

1 The rise of the Ming dynasty, 1330—1367 11

by Frederick W. Mote

Introduction 11

Deteriorating conditions in China, 1330-1350 12

The disintegration of central authority 18

The career of Chu Yiian-chang, 1328—1367 44

2 Military origins of Ming China

by Edward L. Dreyer, University of Miami

Introduction

The rebellions of the reign of Toghon Temur

The Ming—Han war, 1360—1363

The Ming conquest of China, 1364-1368

The army and the frontiers, 1368—1372

58

58

58

72

88

98

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

X

CONTENTS

3 The Hung-wu reign, 1368—1398 107

by John D. LanGLOIS, Jr., Morgan Guaranty Trust Company

of New York

Introduction 107

From 1371 to 1380: Consolidation and stability 125

1380: Year of transition and reorganization 139

1383 to 1392: Years of intensifying surveillance and terror 149

4 The Chien-wen, Yung-lo, Hung-hsi, and Hsiian-te reigns,

1599~1435 182

by Hok-lam Chan, University of Washington

Introduction 182

The Chien-wen reign 184

The Yung-lo reign 205

The Hung-hsi reign 276

The Hsiian-te reign 284

5 The Cheng-t’ung, Ching-t’ai, and T’ien-shun reigns,

1436-1464 305

by Denis Twitchett, Princeton University, and

Tilemann Grimm, Tiihingen University

The first reign of Ying-tsung, 1435-1449 305

The defense of Peking and the enthronement of a new

emperor 325

Ying-tsung’s second reign: The T’ien-shun period,

1457-1464 339

6 The Ch’eng-hua and Hung-chih reigns, 1465—1505 343

by Frederick W. Mote

The emperors 343

Issues in civil government in the Ch’eng-hua and

Hung-chih eras 358

Military problems 370

7 The Cheng-te reign, 1506—1521 403

by James Geiss, Princeton University

The emperor’s first years 403

The court under Liu Chin 405

The Prince of An-hua’s uprising 409

The imperial administration after 1510 412

The emperor’s travels 418

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS XI

The Prince of Ning’s treason 423

The tour of the south 430

The interregnum 436

Assessments of the reign 439

8 The Chia-ching reign, 1522-1566 440

by James Geiss

The emperor’s selection and accession 440

The struggle for power 443

Foreign policy and defense 466

Taoism and court politics 479

Yen Sung’s rise to power 482

Fiscal crises 485

Trade and piracy 490

Yen Sung’s demise 505

The emperor’s last years 507

The Ming empire in the early sixteenth century 508

9 The Lung-ch’ing and Wan-li reigns, 1567—1620 511

by Ray Huang

The two emperors and their predecessors 511

The Wan-li reign 514

The decade of Chang Chii-cheng: A glowing twilight 518

The Tung-lin academy and partisan controversies 532

Petty issues and a fundamental cause 544

An ideological state on the wane 550

The three major campaigns of the later Wan-li reign 563

The Manchu challenge 574

10 The T’ai-ch’ang, T’ien-ch’i, and Ch’ung-chen reigns,

1620-1644 585

by William Atwell, Hobart and William Smith Colleges

The T’ai-ch’ang reign, August—September 1620 590

The T’ien-ch’i reign, 1621-1627 595

The Ch’ung-chen reign, 1628—1644 611

The Shun interregnum 637

11 The Southern Ming, 1644—1662 641

by Lynn A. Struve, Indiana University

The Hung-kuang regime 641

Initial resistance to Ch’ing occupation in the lower

Yangtze region 660

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CONTENTS

The Lu and Lung-wu regimes 663

The Yung-li regime in Liang-Kuang and southern

Hu-kuang, 1646-1651 676

The maritime regime of regent Lu, 1646-1652 693

The southwest and southeast, 1652—1662 701

12 Historical writing during the Ming 726

by Wolfgang Franke, University of Malaya

Introduction: Some general trends 726

The National Bureau of Historiography (Kuo-shih kuan) 736

Ming government publications relevant to history or as

historical sources 746

Semi-official works on individual government agencies and

institutions 755

Semi-private and private historiography in the composite

and annalistic styles 756

Biographical writing 760

Various notes dealing with historical subjects 763

Writings on state affairs 766

Works on foreign affairs and on military organization 770

Encyclopedias and works on geography, economics, and

technology 774

Works on local history 777

Concluding remarks 781

Bibliographic notes 783

В ibliography 816

Glossary-index 860

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MAPS AND TABLE

Maps

I

Political divisions of Ming China

page xxiv

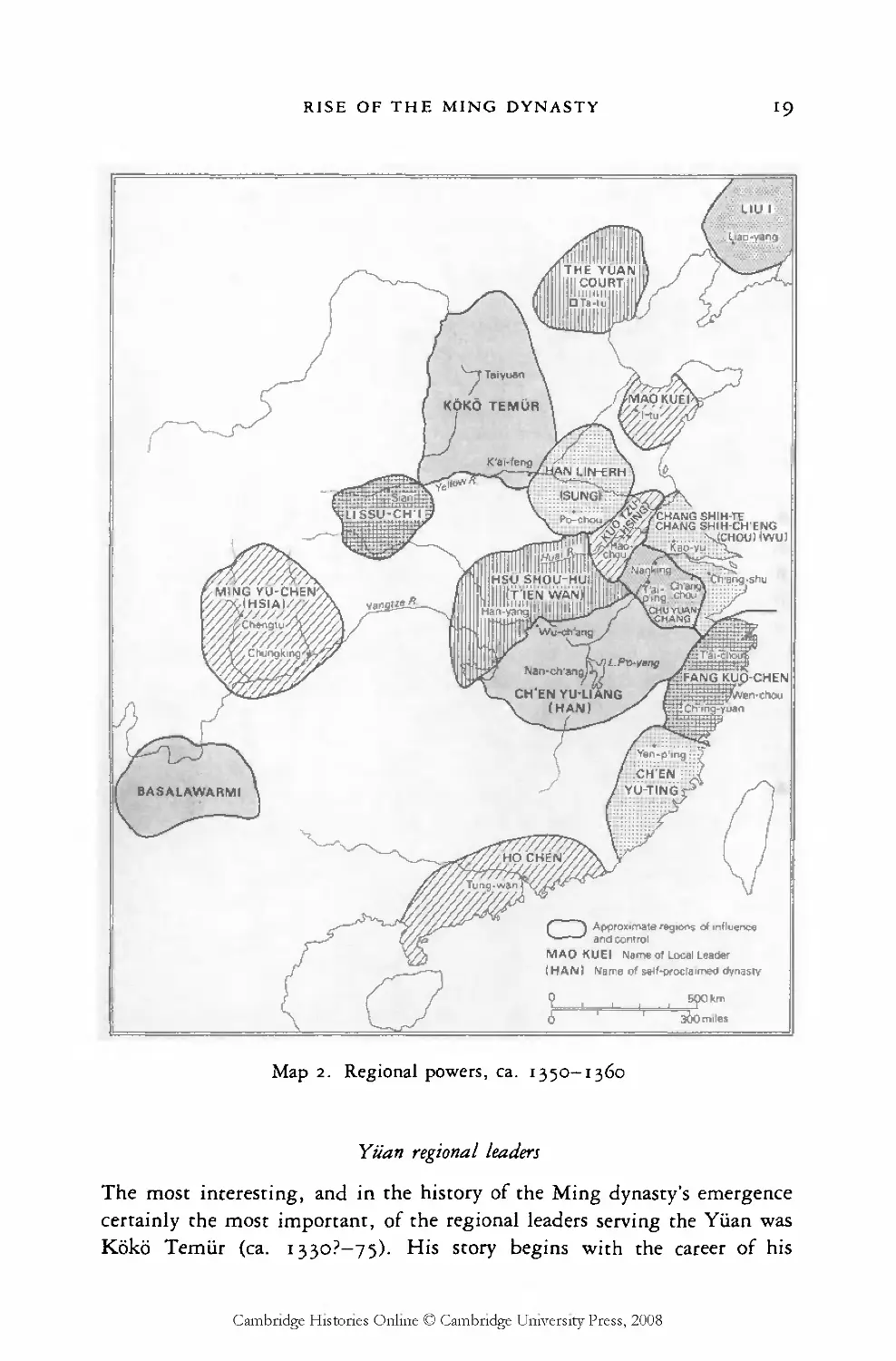

2

Regional powers, ca. 1350-1360

19

3

Nanking and its environs

75

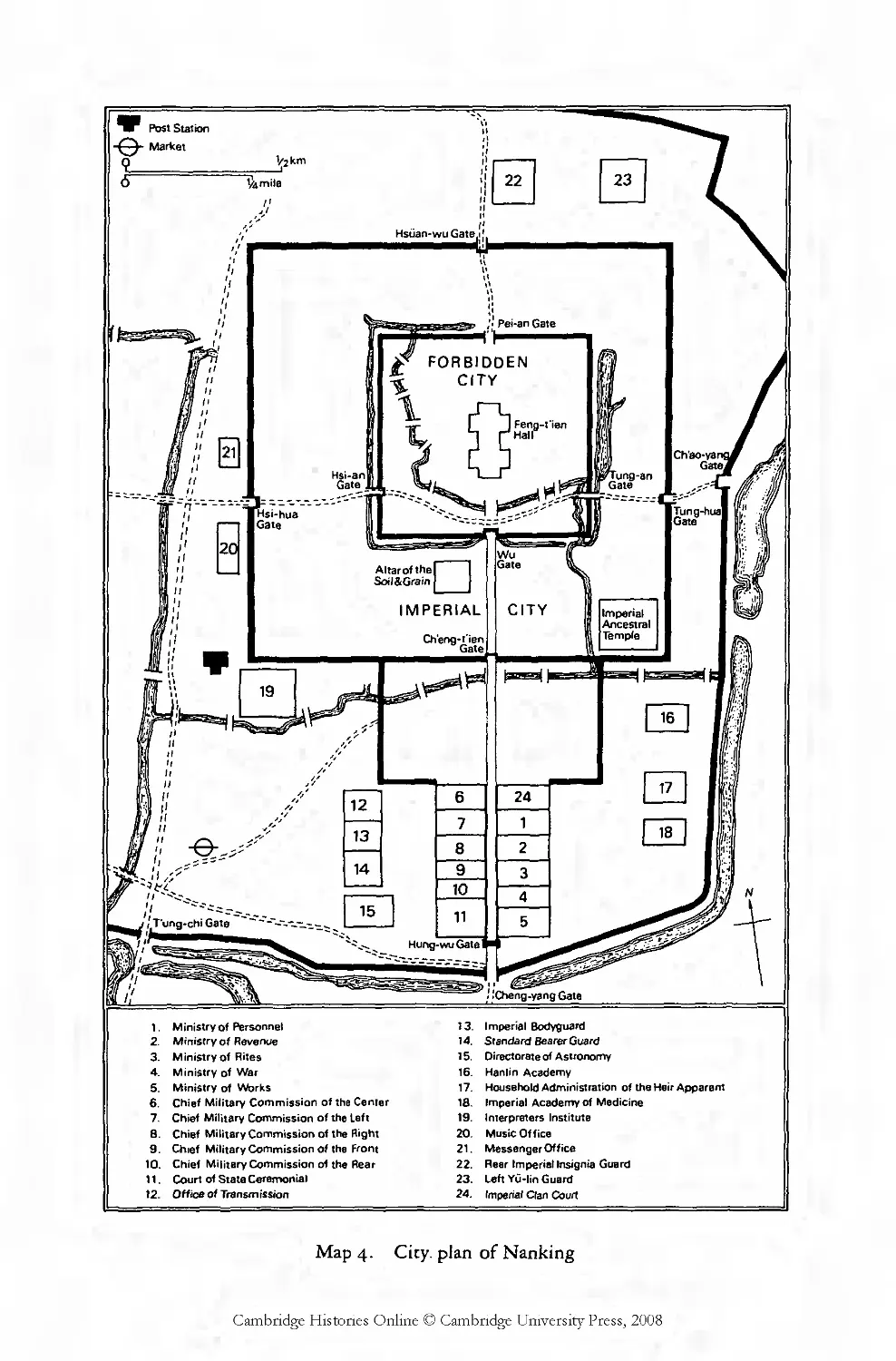

4

City plan of Nanking

110

5

Estates of the Ming princes

121

6

The Szechwan campaign, 1371

126

7

The Yunnan campaign, 1381 — 1382

45

8

The Nanking campaign, 1402

197

9

China and Inner Asia at the beginning of the Ming

224

IO

The Yung-lo emperor’s Mongolian campaigns

225

11

Cheng Ho’s maritime expeditions

234

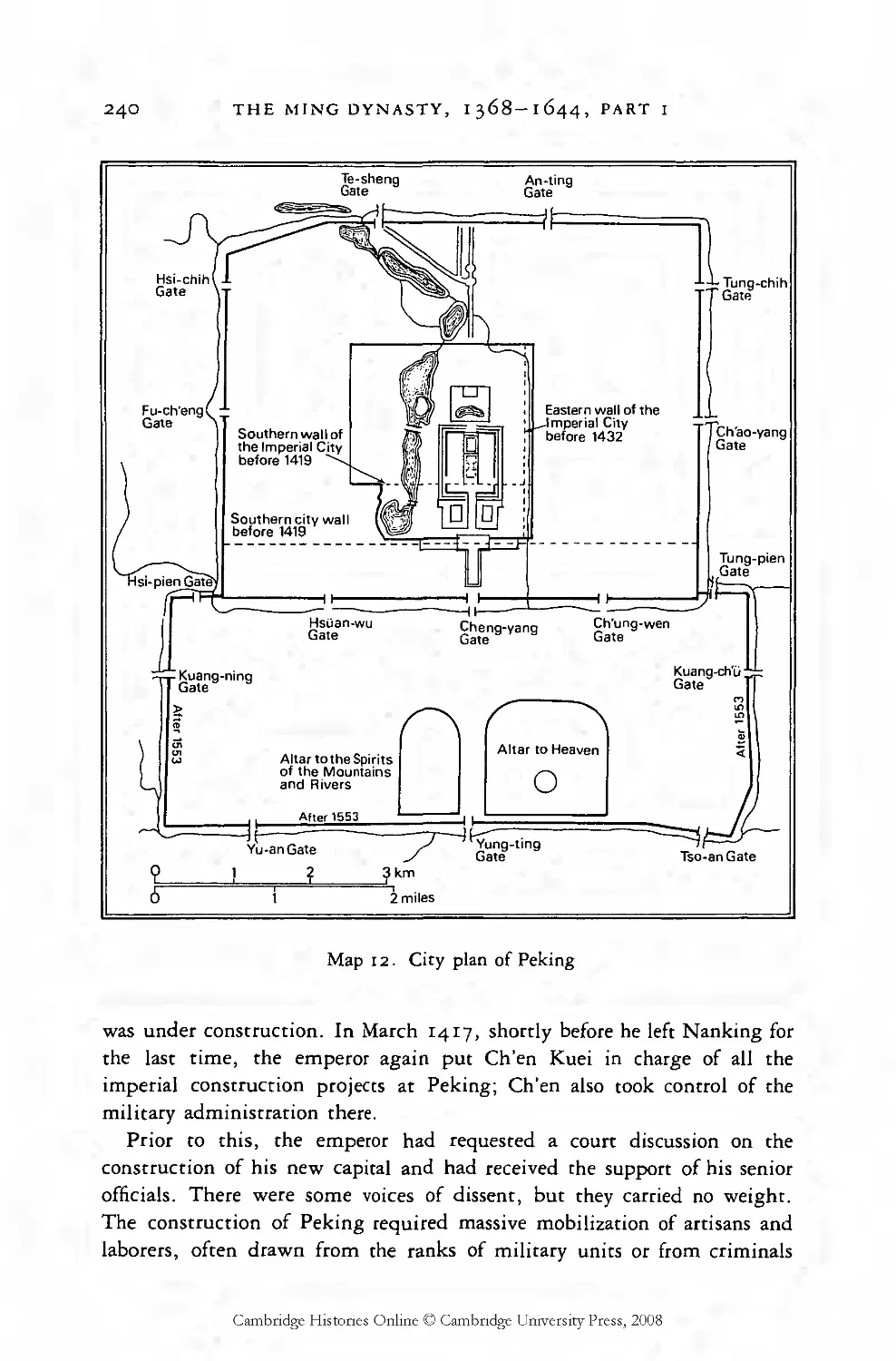

12

City plan of Peking

240

13

Principal offices of the imperial government

243

14

The Grand Canal

253

15

Areas affected by calamities and epidemics, 1430-1450

311

16

The T’u-mu campaign, 1449

323

17

The Ta-t’eng hsia campaign, 1465-1466

378

l8

The Ching-Hsiang rebellions, 1465-1476

385

19

Northern border garrisons and the Great Wall

390

20

The Cheng-te emperor’s travels in the northwest

419

21

The Prince of Ning’s rebellion

429

22

The Cheng-te emperor’s southern tour

431

23

Sixteenth-century Japanese pirate raids

497

24

The Korean campaigns, 1592—1598

569

25

Yang Hao’s offensive against Nurhaci, 1619

578

26

The spread of peasant uprisings, 1630—1638

624

27

The campaigns of Li Tzu-ch’eng, 1641 —1644

633

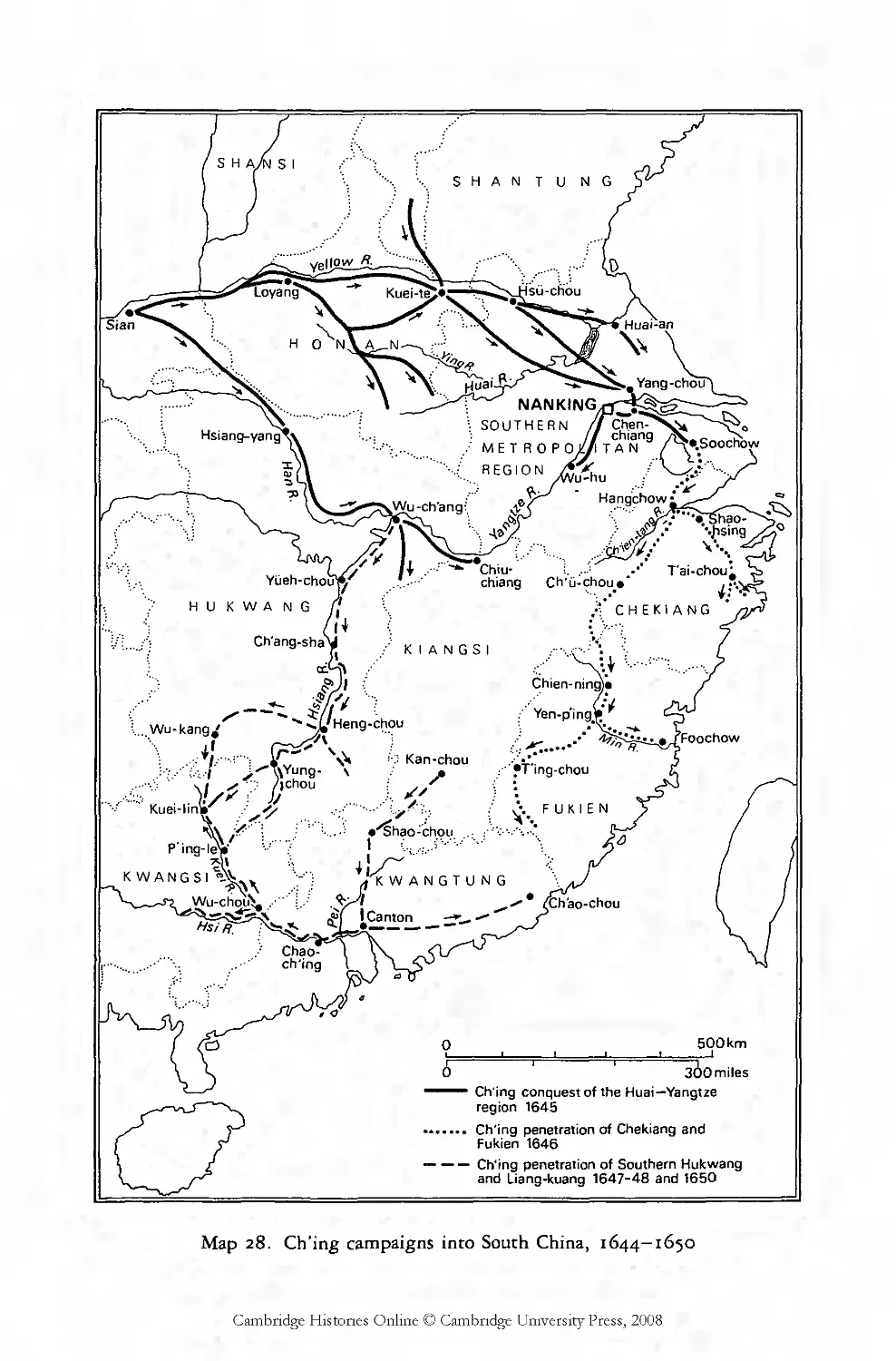

28

Ch’ing campaigns into South China, 1644-1650

659

29

Principal locations of the Southern Ming courts

664

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

XIV

MAPS AND TABLE

30

The end of the Southern Ming

696

31

The movements of Cheng Ch’eng-kung

713

Table

I

Ming princes in the Hung-wu period who went to fiefs

171

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE TO VOLUME 7

The Chinese is romanized according to the Wade-Giles system, which for

all its imperfections is employed almost universally in the serious literature

on China written in English. There are a few exceptions, which are noted

below. For Japanese, the Hepburn system of romanization is followed.

Mongolian is transliterated following A. Mostaert, Dictionnaire Ordos (Pe¬

king, Catholic University, 1941), as modified by Francis W. Cleaves, and

further simplified as follows

c becomes ch

s becomes sh

7 becomes gh

q becomes kh

j becomes j

The transliteration of other foreign languages follows the usage in L. Car¬

rington Goodrich and Chaoying Fang, eds., Dictionary of Ming biography

(New York and London: Columbia University Press, 1976).

Chinese personal names are given following their native form —that is

with surname preceding the given name, romanized in the Wade-Giles

system. In the case of Chinese authors of Western-language works, the

names are given in the published form, in which the given name may

sometimes precede the surname (for example, Chaoying Fang). In the case

of some contemporary scholars from the People’s Republic of China, we

employ their preferred romanization in the Pinyin system (for example,

Wang Yuquan), and for some Hong Kong scholars, we follow the Canto¬

nese transcriptions of their names under which they publish in English (for

example, Hok-lam Chan, Chiu Ling-yeoung).

Chinese place names are romanized according to the Wade-Giles system

with the exception of those plages familiar in the English-language litera¬

ture in nonstandard postal spellings. For a list of these, see G. William

Skinner, Modern Chinese society: A critical bibliography (Stanford: Stanford

University Press, 1973), Vol. I, Introduction, p. iix. The two areas around

Peking and Nanking under the direct control of the court are referred to in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

XVI

PREFACE TO VOLUME 7

Chinese as Pei Chih-li and Nan Chih-li respectively, and in English as the

Northern and Southern Metropolitan Regions. And finally, although Pe¬

king should properly be referred to as Pei-p’ing (The North is Pacified)

from 1368 to 1420, in the interest of clarity it is anachronistically referred

to as Peking throughout the text, except in those places where the history

of the city's name is under discussion.

Ming official titles generally follow those given in Charles O. Hucker, A

dictionary of official titles in imperial China (Stanford: Stanford University

Press, 1985), with the following modifications regarding the terms Secretar¬

iat and grand secretariat. For the period until 1380, the term “Secretariat” is

employed. After that date, we employ consistently the form “grand secre¬

tariat” to translate nei-ko, to underline the unofficial character of that

institution. Its members are referred to with the title “grand secretary.”

Charles O. Hucker’s earlier translation of “National University” for Kuo-tzu

chien has been preferred over “Directorate of Education,” and the translation

“Protector of the State’1 has been preferred over “Regent” for the term

chien-kuo, since the Ming dynasty did not strictly speaking institute any

provisions for a regency. An exception is made in the case of the short-lived

provisional regimes of the Southern Ming (see Chapter 11), when normal

government was no longer feasible.

Emperors are referred to by their temple names during their reign and

by their personal names prior to their accession. The reign title of

“Ch’eng-tsu” is romanized in the form “Yung-lo,” which has become con¬

ventional in English-language literature, rather than in the form “Yung-

le.” The dates for an emperor’s reign refer to the years when the regnal title

was formally instituted. Because the regnal title remained in use after an

emperor’s death until the end of the lunar year in which he died, in most

cases, emperors ascended the throne during the year prior to the institution

of their regnal titles. For example, the Ch’eng-hua emperor ascended the

throne in February 1464, but his regnal title was not used until the

beginning of the next lunar year, and hence the first year of his reign is

traditionally given as 1465.

Dates have been converted to their Western equivalents in the Julian

calendar until 1582 and the Gregorian calendar thereafter, following Keith

Hazelton, A synchronic Chinese-Western daily calendar 1341 —1661 A.D.,

Ming Studies Research Series, No. 1 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota

Press, 1984). The reader should remember that when Chinese sources refer

to a year alone, this year does not correspond exactly to its Western

equivalent.

The ages of individuals are sometimes cited in the Chinese form of sui.

Conventionally a person was one sui at birth and became two sui on the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

PREFACE TO VOLUME 7 xvii

New Year following. Thus in Western terms a person was always at least

one year younger than his Chinese age in sui and might be almost two years

younger if he were born at the end of the Chinese year. In attempting to

give dates for individuals where birth or death dates are not available, the

form cs. (chin shih) is used to indicate the year in which the individual

passed the highest civil service examination.

The maps are based on the recent historical atlas of Yiian and Ming

China, which appears as Vol. 7 of the series Chung-kuo li-shih ti-t’u chi

(Shanghai: Chung-hua ti-t’u hsiieh-she, 1975).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editors of this volume owe thanks first of all to the worldwide commu¬

nity of Ming scholars, a large percentage of whom attended the Ming

History Workshops held at Princeton through the summers of 1979 and

1980, where planning and writing for this volume and Volume 8 were

begun. All of us who have written chapters here have benefited from all

those other colleagues not present as authors in ways that go well beyond

the debts acknowledged in the footnotes. The National Endowment for the

Humanities generously supported those workshops and subsequent coordi¬

nation of the work on this volume and the forthcoming Volume 8. The

Mellon Foundation through the Committee on Studies of Chinese Civiliza¬

tion of the American Council of Learned Societies provided grants to stu¬

dents attending the two summer workshops; their presence added much to

the quality of those exploratory activities. We are grateful for those kinds

of support, as for that generously provided by the Program in East Asian

Studies of Princeton University.

Foremost among individuals who must be accorded special words of

gratitude here is Dr. James Geiss, who has coordinated the Ming History

Project through the years. In addition to writing two chapters in the

present volume, his scholarly editing has contributed substantially to the

continuity and quality of the volume as a whole. Others whose help has

proved invaluable are Professors Wang Yuquan (Peking) and Hsii Hong

(Taipei), who during periods of residence at Princeton and since have

given generously of their extensive knowledge and their critical advice;

Professor Ray Huang, who throughout all stages of the work has contri¬

buted stimulus and wise counsel, drawing on his penetrating analyses of

Chinese civilization; Dr. Philip de Heer, who offered invaluable advice on

mid-fifteenth-century political history; Dr. Keith Hazelton, who devised

the computer supports and ensured that they worked; Nancy Norton

Tomasko, whose considerable command of Chinese language and scholar¬

ship has contributed to her meticulous editing and skillful indexing; and

Dr. Howard Goodman, who prepared the drafts for all the maps and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

XIX

tables in this volume. Cooperative scholarship has never been better

served. For all the delays in completing this volume and for its shortcom¬

ings, we of course are alone responsible.

F.W.M.

D.C.T.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

ABBREVIATIONS

BIHP

BSOAS

CKL

CNW

CSL

DMB

ECCP

HJAS

JAOS

JAS

КС

MC

MCSYC

MHY

MS

MSCSPM

MSL

MTC

MTCTS

MTSHCCS

TMHT

TW

YS

Chung yang yen chiu yuan li shih yii yen yen chiu so (Bulletin of

the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica)

Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies

Cho keng lu

Chung-kuo nei luan wai huo li shih ts’ung shu (alternately

Chung-kuo chin tai nei luan wai huo li shih ku shih ts’ung shu)

Та Ch’ing li ch’ao shih lu

Dictionary of Ming Biography

Eminent Chinese of the Ch’ing Period

Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies

Journal of the American Oriental Society

Journal of Asian Studies

Kuo ch’iieh

Ming chi

Ming Ch’ing shih yen chiu ts’ung kao

Та Ming hui yao

Ming shih

Ming shih chi shih pen mo

Ming shih lu

Ming t’ung chien

Ming tai chih tu shih lun t’sung

Ming tai she hui ching chi shih lun ts’ung

Та Ming hui tien

T’ai-wan wen hsien ts’ung k’an

Yuan shih

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MING WEIGHTS AND MEASURES

I. Length

II. Weight

III. Capacity

IV. Area

1 ch’ih

=

10

ts’un

=

12.3

inches (approx.)

1 pu (double pace)

=

5

ch’ih

1 chang

—

10

ch’ih

1 li

=

1/3

mile

1 Hang (tael)

—

1.3

ounces

1 chin (catty)

=

16

Hang

=

1.3

pounds (approx.)

1 sheng

=

0.99

quart (approx.)

1 tou

=

10

sheng

1 shihltan (picul)*

10

tou

=

99

quarts

=

3.1

bushels

1 той (mu)

=

0.14

acre

1 ch’ing

=

100

той

Note: The Chinese measurements sometimes mentioned in these chapters derive from a bewildering

variety of sources and from regions where standard units varied. They do not imply a dynasty-long or

empirewide standard and are to be treated only as approximations.

*The shihltan was properly a measure of capacity. It is, however, frequently used also as a measure of

weight equivalent to ioo chin.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

GENEALOGY OF THE MING IMPERIAL FAMILY

\ sons 7 sons

1 1 isr| 1 1 1 I I I I

* * Chu T'zu-lang (1629—45)

HA ?-?

* = Sons who died before maturity (selected). r. = Reign period as emperor.

HA = Male heir apparent. reb. = Rebelled. Dashed box = Southern Ming emperors

Note: Table shows only male members of the Chu imperial family who were significant in the line of

imperial succession, who were important rebels, or who were forebears of such men. The numbers of

sons and generational placement of certain individuals follow data in the “Pen chi” and “Chu wang hsi

piao” sections of the Ming shih, corroborated closely in DMB and ECCP. Other sources may vary on

account of criteria for establishing “legitimate” sons, etc.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

MING DYNASTY EMPERORS

Given name

Reign name

Chu Yiian-chang

Hung-wu

(1368-98)

Chu Yiin-wen

Chien-wen

(1399-1402)

Chu Ti

Yung-lo i

(1403-24)

Chu Kao-chih

Hung-hsi

(1425)

Chu Chan-chi

Hsiian-te

(1426-35)

Chu Ch’i-chen

Cheng-t’ung (1436—49)

Chu Ch’i-yii

Ching-t'ai

(1450-56)

Chu Ch’i-chen

T’ien-shun

(1457-64)

Chu Chien-shen

Ch’eng-hua

(1465-87)

Chu Yu-t’ang

Hung-chih

(1488-1505)

Chu Hou-chao

Cheng-te

(1506-21)

Chu Hou-ts’ung

Chia-ching

(1522-66)

Chu Tsai-hou

Lung-ch’ing (1567-72)

Chu I-chiin

Wan-li (1573-1620)

Chu Ch’ang-lo

T’ai-ch’ang

(1620)

Chu Yu-chiao

T’ien-ch’i

(1621-27)

Chu Yu-chien

Ch’ung-chen (1628—44)

Southern Ming

Chu Yu-sung

Hung-kuang (6.1644—6.1645)

Chu Yii-chien

Lung-wu

(8.1645-10.1646)

Chu Ch’ang-fang

regent Luh (6.1645)

Chu Yu-lang

Yung-li

(12.1646-1.1662)

Chu Yii-yueh

Shao-wu

(12.1646)

Chu I-hai

regent Lu

(8.1645-1653)

Temple name

T’ai-tsu

Hui-ti, Hui-tsung

T’ai-tsung, Ch’eng-tsu

Jen-tsung

Hsiian-tsung

Ying-tsung

Tai-tsung, Ching-ti

Ying-tsung

Hsien-tsung

Hsiao-tsung

Wu-tsung

Shih-tsung

Mu-tsung

Shen-tsung

Kuang-tsung

Hsi-tsung

I-tsung, Ssu-tsung,

Huai-tsung,

Chuang-lieh-ti

An-tsung

Shao-tsung

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Map i. Political divisions of Ming China

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

This volume and the following volume are devoted to the history of the

Ming dynasty. The present volume offers a narrative account of political

developments from the rebellions of the mid-fourteenth century that ended

the Mongol Yiian dynasty’s control over China —and from one of which the

new Ming dynasty was formed in 1368 —until the last Ming remnant,

called the Southern Ming, was extinguished in Burma in 1662. That was

almost twenty years after the new Manchu Ch’ing dynasty had proclaimed

the success of its conquest of the Mandate of Heaven, and of China, in

Peking in the spring of 1644.

That period of roughly three centuries from the 1340s until the 1660s,

or more closely defined, the 277 years from 1368 until 1644 during which

Ming rule formally prevailed, is the only segment of later imperial history

from the fall of the Northern Sung capital to the Jurchen invaders in 1126

until the Revolution of 19 n ended the imperial era during which all of

China proper was ruled by a native or Han Chinese dynasty. The actual

impact of that alternation of native and conquest dynasties on Chinese life

was, to be sure, of varying significance, and at its most destructive it

probably never threatened to interrupt the cultural continuity of Chinese

development. Nonetheless, the success of the Chinese in regaining control

over their own government is an important event in history.

In Ming times and even more so in the recent nationalistic-minded

century, the Ming dynasty has been seen as an important era of Chinese

resurgence. The life of that resurgent society in social, intellectual, eco¬

nomic and other dimensions is surveyed in Volume 8. There we see much

evidence that the Ming period witnessed the growth of Chinese civilization,

the filling out of the realm, and, if one may indulge in biological meta¬

phor, the maturing of the traditional Chinese civilization in that last phase

of its relatively secure intramural isolation and splendor. We can see steady

if undermeasured population increase, a significant increase in literacy, and

the growth of learning throughout sub-elite levels of society, accompanied

by a flourishing of sub-elite as well as elite cultural forms. We observe the

filling out of the system of urban networks, reflecting the expansion of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

2

THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

productivity and of exchange. The growing importance of the maritime

southeast provinces and the centrifugal forces that propelled many of the

region’s hardy residents into lives abroad preceded Europe’s era of mercan¬

tile expansion and might have rivaled it. The absorption of China’s inland

southern and southwestern provinces during the Ming also is evidence of

the age’s expansiveness. The boundless energies of Ming society must be

kept in mind as the political history of the age is recounted.

What should be the final assessment of Ming government? Was the Ming

an era of strong government, or merely one in which the throne and its

accessories could intimidate the civil government in awesome displays of

willful violence? Was it an era of effective administration, or one in which

the practical limitations imposed by the milieu seriously limited political

accomplishment? Was domestic administration the tool through which the

imperial institution in this period of its long history more perfectly than

before realized its potential to govern, or was it in fact the vehicle by which

class interests and local interests in society achieved their counter purposes?

Such questions, perhaps themselves framed in misleading terms, have long

been asked. The reader here will want to ask his own questions of this

material. It may help to identify some of the components of Ming political

history that have led to so broad and contradictory a set of questions about it.

Outwardly at least, the Ming dynasty appears to be a period of very

powerful government. Its founder made it a strong, assertive, highly cen¬

tralized regime. But are those appearances misleading? It can be argued

that the early emperors’ will to centralize and to assert the supremacy of

their will over all acts of governance was never in fact as effectively institu¬

tionalized as those rulers intended and perhaps deceived themselves into

believing it was. Professor Ray Huang, here and elsewhere, argues that the

Chinese preference for ethical over technical solutions to all social problems

created limitations in the working style of government that deflected the

exercise of power. His arguments have compelling force —but the aura of

great power cannot be dispelled. For evidence, one need only look at

China’s enhanced position in East Asia in Ming times.

Several military-minded early emperors reestablished China’s dominance

not only in Inner Asia, whence China’s conquerors traditionally had come,

but also throughout the sea lanes of Asia. A previous era of diplomatic

reciprocity between China and the other Asian land powers was succeeded

by an era of a sinocentric world order based on the Chinese presumption of

Chinese centrality and superiority and at least nominally acknowledged by

many other states, great and small, through the vehicle of the tribute

system. Domestically also there was again a structure of centralized control

and supervision—the thousands of local and regional administrators, as well

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

3

as the central government’s officials, were recruited by merit and appointed

directly through agencies of the central government. Even more than in

model early dynasties, the Ming attempted to regularize the exercise of

political power and to make uniform the patterns of bureaucratic behavior

so as to correct what early Ming rulers saw as the lenient, slipshod, and

corrupt mismanagement that had been imposed by a succession of alien

dynasties. Above all the early Ming state, for better or for worse, sought to

consolidate its power by stimulating a uniform ideological basis for private

and for bureaucratic behavior. The resulting “revised” neo-Confucian ethos

was in many ways a new Ming achievement, and it had profound conse¬

quences for political life.

Despite those strong beginnings, the political history of the Ming is not

one of consistent achievement. The chapters that comprise this volume

often focus on political weakness. Ming government has been described by

some modern scholars as the great achievement of Chinese civilization. It

also has been seen as proof of ineradicable anomalies of forms versus actuali¬

ties, as a working system ever in need of patching up but never susceptible

to thoroughgoing rational correction. Reflections of both points of view

will be encountered here. Yet whatever criteria assume the greater signifi¬

cance for these authors, one must conclude that the governing of Ming

China was a vast undertaking, grand in its assumptions, lofty in its profes¬

sional ideals, and exhaustingly intricate in the interplay of ideal and actual

patterns that marked its daily existence.

If those fundamental characterizations of the quality of Ming govern¬

ment remain inconclusive, some long-range trends in the development of

governing modes seem clear enough. Despite the rigidly prescribed norms

and procedures made binding on all his heirs by the autocratic dynastic

founder, Ming government was not unchanging. Trends become discern¬

ible over the course of these three centuries. It may serve a useful purpose

here to point out some of those trends.

A most intriguing feature of Ming political history is the trend from

direct rule by a highly competent (in his own eyes, omnicompetent) found¬

ing emperor toward the evolving system of shared authority, whether prop¬

erly delegated or usurped. Ming emperors were the capstone in an authority

structure that could not function without them. They were the ritual heads

of state and society within a civilization in which ritual possessed a scope of

functional significance scarcely comprehensible to us today. Ming emperors

also, however, were the executive officers of a system that required their

daily participation in deciding and validating routine acts of governing. In

the absence of that, some not-strictly-acceptable substitute for the em¬

peror’s own ruling actions was required.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

4

THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

Implicit in that system is the impractical notion that emperors could and

would make informed decisions on a very broad range of matters of state

from routine appointments for all the thousands of offices to be filled by

ranked civil and military officials to vast or trivial modifications of policy.

True, that would in most cases mean merely reviewing and approving

prescreened lists of candidates for most offices, as worked up by the Minis¬

try of Personnel, or making no more than minor alterations in the course of

approving action proposals submitted for his notation of “accepted” and his

seal. Yet no actions or appointments were possible without at least the seal,

and in all matters of higher import the emperor was expected to have

digested analyses and arrived at his own judgments. Although that scope of

competence and function was inherent in the Chinese conception of monar¬

chy, it was operationally institutionalized in Ming times to a degree hith¬

erto unknown. From the fall of the dynasty in the seventeenth century

onward, historians have judged that to have been the crucial weakness of

Ming government and have blamed the founding emperor for abolishing

the offices of chief ministers of state and their supporting secretarial and

advisory staffs in 1380.

The reorganization of government stemming from that “abolition of the

prime ministership,” removal of the top level of authority in the outer

court, and the resulting assumption of those support functions by the ruler

and his inner court, gave a new shape to the structure of Chinese central

government that would last through all of Ming and Ch’ing times until the

revolution of 1911. In reality, the intention of the Ming founder was

modified already in his own reign and was reshaped by cumulative accre¬

tions and conventional adaptations in every reign thereafter according to

the current conditions and the age, competence, and commitment of the

successive rulers. The suspicious-minded founder’s fear, of course, had been

that his professional bureaucrats in senior roles as advisors and administra¬

tors would bend the acts of governing to serve their own interests or might

even attempt outright usurpation. He also feared that the same breed of

scholar-officials in lower-ranking roles as local magistrates would misuse

their authority.

Some scholars have seen genuine benefit to the farming masses from the

founder’s emphasis on improving the conditions of rural society and tight¬

ening up the norms of local government, whether he did that out of simple

altruism or was shrewdly cognizant of the state’s interests, or both. If his

suspicion of bureaucrats was in that matter constructive, at the higher

levels of the complex political machinery, corrosive suspicion backed up by

unfathomable terror was profoundly destructive, the more so because once

institutionalized, it continued to influence the long range of history. One

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

5

can argue that as a political leader of China’s fourteenth century he had no

choice but to build a government reliant on the services of cultivated men

who would proclaim their neo-Confucian commitment. The contradiction

lies in his acknowledging that necessary condition of governing Chinese

society, while remaining deeply suspicious of its consequences; he institu¬

tionalized his officialdom’s constant intimidation and distanced the throne

from the kinds of rational administrative supports that the bureaucracy

itself should have best provided. That was to build a regime with serious

weaknesses.

It is fascinating, then, to observe reign by reign through the chapters

comprising this volume the range and cumulative effect of the institutional

adaptations that were made in the effort to overcome that basic administra¬

tive flaw. We do not know much about the second emperor (1398-1402),

but it seems clear that he greatly upgraded the advisory functions of his

principal scholar-mentors, because the impropriety of having done just that

was one of the excuses given for the usurpation. The usurper who held the

throne from 1402 until 1424 in a reign of great vigor and high competence

was not bound by the principles he claimed to defend. Because his interests

lay in solving border problems away from the court, he began to create the

inner court institutions that would free him from the drudgery of governing.

Most pertinent was his plan to select top examination graduates tor

elite careers in the Hanlin Academy, leading to the posts that in time

came to constitute the nei-ko, or grand secretariat. At the same time he

assigned larger roles to eunuchs, even insisting that numbers of them be

formally educated in government practices and precedents. That, of neces¬

sity, led to intricate forms of cooperation between civil bureaucrats and

their eunuch counterparts, even as each group contested for emperors’

support and the increase of its own powers at the expense of the other.

Mostly, it must be noted, that practice worked smoothly enough, but the

recurrent failures were spectacular, as when eunuchs managed to become

all-powerful dictators who manipulated emperors and defied the norms of

bureaucratic government.

The first such case came in the 1440s in the reign of the boy emperor

Ying-tsung. The flamboyant abuses in half a dozen such cases to the end of

the dynasty are what come to mind immediately in relation to eunuchs in

Ming government. If most of the tens of thousands of eunuchs who were in

civil or military service at any one time from the late fifteenth century

onward were more or less routine performers and not flamboyant abusers of

power, nonetheless it is likely that in some of their regular functions —

notably as managers of international trade along the inland frontiers and at

the maritime entrepots, and as procurers of supplies and special revenues

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

6 THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

for the imperial city-they probably performed very badly most of the

time.

The loss in 1380 of the chief ministerships and the isolation of the

emperor from responsible senior advisors having their proper place at the

head of the outer court thus can be seen as the starting point for the

development of both the grand secretariat and the regular bureaucracy’s

counterpart eunuch bureaucracy, both elements of the Ming inner court.

The interplay between these irregular, though eventually highly regular¬

ized, elements of Ming government is the major focus of political history

throughout the dynasty. Some emperors worked well within the system,

sometimes adding to it significantly. Others, as these chapters show, seri¬

ously defaulted or resisted the norms, with varying consequences. From our

modern point of view, it is all too understandable when the reader of

history feels oppressed with frustration that the system’s obvious irrationali¬

ties could not be overcome by generation after generation of acute-minded

and devoted statesmen-bureaucrats.

The dismal account of political failures can perhaps assume too large a

place in our consciousness as we read this volume. There is another side to

the story that must not be lost sight of. The world’s largest society, spread

across an area as large as Western Europe, truly flourished under this

fallible system of governing, and the flow of well-prepared, committed

officials-expectant never diminished. In each decade there was a new group

of able persons eager to make careers in government service. Whenever one

group’s energies and enthusiasms were dissipated by the frustrations of

service, eager replacements were at hand to carry on. There was a freshness

and energy in the civil service under this dynasty that is not matched in

later times, even though governing often faltered.

Was Ming China, then, poorly governed? The Ming government’s

strengths were simultaneously its weaknesses; for example, its heavy emphasis

on cultivation, on learning, and on ethical obligations bound it to limited

responses that accepted the primacy of precedent, of compromise, and of face

saving. It had the weaknesses and the strengths of a massive stability. We

might better ask whether any of the Ming state’s contemporaries throughout

the world (and none faced problems of Chinese scale) was better governed. In

most historians’ minds, such a question probably does not embarrass China

until well into post-Ming times. Given the scope of the Ming government’s

tasks in maintaining the unity and sense of shared destiny throughout so large

a territory and in providing enough self-renovating features to keep the society

flexibly if slowing changing, usually at peace and in order, its achievements

are impressive. Moreover, Ming government allowed those Chinese people

who could attain more than mere subsistence to employ their resources mostly

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

7

for the uses freely chosen by them, for it was a government that, by comparison

with others throughout the world then and later, taxed the people at very low

levels and left most of the wealth generated by its productive people in the

regions where that wealth was produced. Inequities abounded. But the society

remained open, and it offered people at all levels a wider spectrum of choices

than they have known more recently. The government of Ming China is not to

be dismissed out of hand.

Other trends encompassing change from the fourteenth century to the

seventeenth can be followed through successive reigns of Ming history. One

is apparent in the defense posture of the Ming state. The stable element in

that is the obsession with the threat posed by the neighboring Mongol

nation to the north, understandably so, since the dynasty came into being

by resisting and then expelling China’s Mongol conquerors; it had to guard

against their resurgence until another northern neighbor, the Manchu,

superseded the Mongols early in the seventeenth century as the enemy to

the north. If that focus on the Mongol enemy was the enduring part of the

situation, what long-range trend of change emerges? It is one of retrench¬

ment. At first the new Ming state met the Mongols in their kind of warfare

on their home ground; before the middle of the fifteenth century, that had

changed to a defense policy of withdrawal behind fixed barriers along the

line marking the northern extent of Chinese-style sedentary life. The

founding emperor planned to maintain garrisons far out into the steppe.

The usurper, the Yung-lo emperor in the first quarter of the fifteenth

century, repeatedly campaigned in the steppe, but failed to make the

forward garrisons viable parts of an active defense by offense. He withdrew

the garrisons to more readily defended, fortified strategic passage points.

Despite that consolidated defense line, the Mongols invaded, disastrously

for China, in 1449 and again in 1550, and raided constantly. By the 1470s

China had begun to connect the fortified barriers wirh long walls supported

by towers and bastions. The fabled Great Wall, more accurately a series of

long walls, came into being. For the rest of the dynasty, wall building and

the garrisoning of the wall defense zone became the preoccupation of the

Ming state. The Inner Asian frontier became a stifling burden.

Frontier problems can be the source of great stimulus to a nation. The

Inner Asian frontier had been that for China in earlier dynasties such as the

Han and the T’ang, but in Ming times the consequences seem to have been

wholly negative. Far greater opportunities for Ming China’s involvement

with the rest of the world — whether with Japan and Korea, or with the

maritime states to the south and beyond, or with the European powers

whose first ships to reach China were those of the Portuguese who sailed

from Goa and Malacca into the estuary of the Pearl River below Canton in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

8

THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

1517—were neglected. Early fifteenth-century Ming China had sent out

the largest and farthest-ranging flotillas in world history up to that time;

they had gone as far as the Persian Gulf and the coast of Africa. Whatever

promise that might have held, it all passed from the scene, in part surely

because the obsession with the Great Wall left no time for the Ming state

to look elsewhere and assess other opportunities in positive terms.

The revealing counterpart to that trend of retrenchment and passivity

in the north and the consequent failure of the Ming state to expand in

other directions is the trend of increasingly imaginative and bold partici¬

pation in maritime commerce by private interests—in defiance of govern¬

ment sanctions —all along China’s eastern seaboard, particularly from the

Yangtze Delta south to Canton. What might that have accomplished if,

like its counterparts in Europe in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, it

had gained state sponsorship and support? Even without state sponsor¬

ship, Chinese merchant and craftsmen colonies, and eventually agricul¬

tural settlements as well, came into existence from the Philippines

through Southeast Asia, and mostly date from Ming times. The boundless

energies, ingenious entrepreneurship, aggressive risk-taking, and creative

leadership within the society seen within this Ming maritime expansion is

at curious variance with the retrenchment and managerial failures of the

state in its northern defense posture.

Less striking perhaps, but another trend of great significance, is the

expansion of the Chinese population throughout the border provinces of the

south and southwest, the displacement or absorption of non-Han minori¬

ties, and the extension of Chinese administration to the borders of modern

Burma, Laos, and Vietnam. The earliest of the Ming emperors lent the full

force of the state’s military resources to that; Yunnan was conquered and

absorbed for the first time under Chinese rule (although Khubilai had

conquered the region in the 1250s and had set up a somewhat attenuated

Mongol administration there); Kweichow was organized as a province;

Annam was warred upon and unsuccessfully absorbed in the 1420s. The

“pacification” of tribal peoples throughout the southwest is also a recurrent

theme throughout the chapters of this volume. Eventually, however, the

state’s role became less aggressive. Cultural assimilation continued, but

now the impulse for further assimilation came from trade and mining and

Chinese population growth pressing into the richer valleys of the region.

The interesting counterpart to that growth in the south and southeast is

the striking trend of shrinkage and decline in the northern defense zone and

particularly in the far northwest. Climatic change may have lowered the

margin in agriculture throughout that marginal zone, but social factors also

contributed. The siege mentality that descended on the region as the

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

INTRODUCTION

9

defense zone buildup developed through the second half of the dynasty was

crippling enough. Trade diminished. The movement of goods and of

people was decreased as much by economic decline of the region as by the

restrictive military conditions. The normal concerns of civil government

were secondary to the military administration. Finally, the state’s policy of

underpaying or abandoning its defense garrison soldiers, especially the

undertrained and overaged, drove them into banditry. All these forces

working together induced increasingly unstable conditions within this nar¬

row band of the northern and northwestern frontier. It is not surprising

that the region’s endemic disorder, although quite atypical of late Ming

society in general, should spawn the two large movements of roaming

banditry that became a peril to the rest of China in the 1630s. One of

these, dignified as the "rebellion” of Li Tzu-ch’eng, plundered at will

through North China and, quite fortuitously, found an unguarded moment

when it could breach the gates of Peking. That formally terminated the

dynasty in 1644.

These are some of the trends obvious to the reader of Ming history. Also

apparent throughout this volume is the richness of detail that can be

reconstituted in many aspects of this history.

The procession of the sixteen incumbents of the throne between 1368

and 1644 and the several would-be successors who fought on against the

Manchus from the far south until 1662 are a gallery of diverse types whose

lives beg for fuller reconstruction. There is no full political biography of

any of them in a Western language. Even though Chinese emperors are

among the most elusive of subjects in Chinese historiography, much could

be done to remedy that lack. But beyond those imperial figures (and

countless others of the imperial clan), there is a wealth of documentary

evidence for lives, for places, and for actions of all kinds. There are count¬

less volumes of Ming writings — poetry and belles lettres, serious scholar¬

ship in many fields, religious and philosophical studies, plays and stories

and other entertainment writings, reports written by officials on all govern¬

mental subjects, and the writings of Ming historians beginning the task of

putting their history in order. No scholar can know more than a fraction of

all this vast sea of words, comprising more printed books in existence at

any time during this dynasty than in all the rest of the world together.

Many large aspects of the field have been virtually unstudied in the present

century, during which the total volume of relevant materials has been

greatly augmented by facsimile printing, archeology, and archival labors.

During most of the present century Ming history has not been a widely

studied subject in China, in Japan, or in the West. The vast array of

traditional historical materials, ably described by Wolfgang Franke in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

IO THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

Chapter 12 of this volume, now attracts the attention of a generation of

new scholars, and the world of scholarship begins to appreciate how impor¬

tant the history of these centuries must be in the larger frameworks of

Chinese and of world history. The authors and editors have undertaken the

effort of compiling this volume with a certain confidence that it carries

scholarship some modest steps forward, but in greater confidence that the

field will quickly move beyond it in larger steps. I am confident that a

number of these authors will be present to contribute to the early retire¬

ment of this work, as they move forward to supersede it. I hail their

present achievement and look forward to their early success in surpassing it.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

CHAPTER 1

THE RISE OF THE MING DYNASTY,

1330-1367

INTRODUCTION

The character of the Yuan dynasty, through which the Mongol conquerors

from Khubilai Khan onward ruled China, has been interpreted in many

ways and at present is still much at issue among scholars.1 Nonetheless,

one fact about it is unambiguous. Its ability to govern —to maintain order

in society, to administer provincial and local government, and to collect

taxes —was eroding well before the middle of the fourteenth century. Chu

Yuan-chang (1328—1398), the founder of the Ming dynasty, was born into

a family of desperately poor tenant farmers in the Huai River plain of

modern Anhwei province on 21 October 1328. He never experienced the

normal conditions of China’s stable agrarian society until, as emperor forty

years later, it fell to him to rule over the empire and to guide its rehabilita¬

tion. The Ming dynasty was spawned during a half-century of intensifying

chaos, an age of breakdown in which throughout most of the country the

conduct of daily life increasingly depended on direct recourse ro violence. It

provides a classic example of the gradual militarization of Chinese society

and, because of that, of the struggle among potent rivals to succeed the

Mongol regime by imposing, through military force, a successor regime

that could claim the Mandate of Heaven. Despite the traditional Chinese

penchant for subsuming this into the stylized pattern of breakdown and

regeneration provided by their dynastic cycle theory, the way the Yuan

dynasty disintegrated and the Ming dynasty emerged is by no means typi¬

cal of the dynastic changes that punctuate imperial Chinese history. The

middle half of the fourteenth century is an extraordinary age. Chinese

society in chaos reveals much about its latent potentialities and its normally

less-exposed structural framework. This period thus displays aspects of the

character of Chinese civilization that are not so readily discernible in times

of peaceful, orderly civil government. And the violence of this period left

its enduring mark on the Ming dynasty. It richly merits the historian’s

thoughtful attention.

i The history of the Yiian dynasty forms part of Volume VI.

11

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

12

THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

DETERIORATING CONDITIONS IN CHINA, 133O-135O

The Yuan court

Factionalism is endemic to politics and was present throughout the Yiian

dynasty; it became a crippling factor in government early in the four¬

teenth century. After Khubilai’s long reign (1260-94), cliques of cour¬

tiers representing conflicting interests of his grandsons and their heirs

often engaged in murderous intrigues to control the throne. Some scholars

see two competing policies at the crux of the continuing struggle among

factions. The one was a Mongolia-based policy (and faction) with an

orientation toward Mongol interests in the Inner Asian steppe, repre¬

sented by the traditions of the Chagatai Khanate. The roots of this policy

are traced all the way back to the rivals of Khubilai, especially Khaidu of

the line of Ogodei, who had warred against Khubilai throughout his

reign. The other faction is identified with what have been called the

“Confucian” concerns of governing from a China-based throne using bu¬

reaucratic means to achieve its statist ends. This provided a fundamental

and irreconcilable split within the Mongol political leadership over the

means and goals of governing China.2 The latter group engineered a coup

in 1328 that “restored” the line of Khaishan, who had reigned 1308-12,

and is known by his posthumous title as the emperor Wu-tsung. His two

sons, Khoshila and then Tugh Temur, were placed on the throne in

1328. The former was assassinated by partisans of the latter, who is

known as Wen-tsung and who reigned until 1332. He was succeeded by

his two young sons. First was the younger, Irinjinbal, who died as a child

of six after a reign of two months. Upon his death, in perhaps suspicious

circumstances, his older brother Toghon Temur came to the throne in

1333 at the age of thirteen. The last Mongol ruler over China, he was

driven from his capital at Ta-tu (Peking) by Ming armies in 1368 and

died in the steppe in 1370. Toghon Temur is known in Chinese history

by his posthumous titles Shun-ti, granted him by the Ming founder, or

Hui-ti, the title bestowed by his refugee court in Mongolia. His reign of

thirty-five years to 1368 contrasts with the average of about five and

one-half years for the seven reigns from the death of Khubilai to 1333, a

period marked by plots, coups, and regicide. The length of his reign does

not signify, however, that a new stability in Yuan rule had been

achieved. Instead, the factional infighting had shifted from coups aiming

2 This interpretation of the late Yuan politics has been most forcefully stated by John W. Dardess in

Conquerors and Confucians: Aspects of political change in late Yiian China (New York, 1973).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

RISE OF THE MING DYNASTY

r3

at control over puppet emperors to struggles among Mongol holders of

regional military power for control of the court through its chief offices,

the posts of chancellor of the right and of the left. That in itself signified

no improvement in the quality of government.

The reign of Shun-ti corresponds roughly with the period of the Ming

dynasty’s emergence. The last Mongol emperor is described in many con¬

temporary Chinese sources and by early Ming historians as having been a

monster of debauchery, surely an exaggerated depiction, but it is difficult

to determine to what extent it is exaggerated. Some contemporary writers

praised him. In either case, he mattered very little in the events that saw

the dynasty’s once vaunted power crumble and disappear. Chinggis Khan,

military genius, leader of vast purpose and of superhuman energies, had in

this seventh-generation descendant yet another successor of at best mediocre

qualities. It is comment enough to note that the history of his reign turns

on larger personalities and on problems largely made and met by others.

The decline of Yuan military power

The Yuan government’s military forces had been in decline since the end of

the thirteenth century. Following the conquest of the Southern Sung in the

1270s, the main body of Mongol and Inner Asian troops within China had

been deployed at garrisons on the Yellow River plain to shield the capital

at Ta-tu (Peking). Special units of Mongol forces were dispatched to points

of strategic importance as needed, but they were not distributed through¬

out the provinces to police the empire on a regular basis. Armies of Chinese

professional soldiers, both those who had been subject to the Jurchen Chin

dynasty before its fall to the Mongols in the 1230s, and those who had

surrendered during the conquest of the Southern Sung in the 1270s, com¬

prised the principal elements in the garrisons stationed elsewhere.

This pattern persisted until the end of the dynasty; that is, the main

Mongol garrisons and the imperial guard forces were stationed in the north,

close to the capital, while Chinese units, sometimes under Mongol or West¬

ern Asian commanders, guarded the central regions, the south, and the

southwest. These provincial garrisons were not evenly distributed, but were

concentrated in the lower Yangtze region. Yang-chou, Chien-k’ang (Nank¬

ing), and Hangchow were the most strongly garrisoned bastions of Yuan

power outside the capital region. This was to protect the rich region at the

southern end of the Grand Canal that supplied the capital with revenues,

especially with the tax grains. Elsewhere smaller concentrations of troops

were placed at regionally important locations in Szechwan, in Yunnan, the

central Yangtze, and the southeast coast.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

14

THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

The Yiian military garrisons were poorly administered. One scholar has

written that even by the end of the thirteenth century, mismanagement

was causing breakdowns of the military system, and by the 1340s it had

been repeatedly demonstrated to be incapable of repressing local rebellions

and banditry. Even the imperial guards based at the capital, who were

occasionally sent into the field in major campaigns, were by that time no

longer held to be invincible.3 From the early fourteenth century onward, a

geographic correlation between the regional distribution of the main Yiian

military might and relative freedom from rebellious activity is obvious;

even more obvious is the correlation in time between the sharp decline of

Yuan military effectiveness everywhere by midcentury and the progressive

increase in rebel activity. The Yiian dynasty’s capacity to coerce the Chi¬

nese, whether by relying on Inner Asian military units (including the

Mongol forces based within China proper) or by using the Chinese profes¬

sional soldiers and conscripts from the civilian population, rapidly dimin¬

ished through these decades. More important, that fact was becoming

widely recognized throughout the Chinese population.

As society became disorderly and unsafe, on the one hand local leaders

in government or in private life assumed initiatives in organizing local

defense forces and building defense installations. On the other hand,

bandits took advantage of disorder to form ever larger and bolder organi¬

zations. Both local self-defense leaders and local bandits could assume

illicit political roles by declaring themselves independent of the legitimate

arms of government in order to maximize their freedom of movement and

their claims on support. Those genuinely interested in local defense, often

representing or linked to the local elite but not necessarily stemming

from elite backgrounds, tended to remain susceptible to reimposition of

government controls, although often negotiating continuations of their

freedoms of initiative and enhancement of their leaders’ status. Other

autonomous movements representing some stage of banditry expanding

into open rebellion also could use their military power as a negotiating

point in securing legitimation with ranks and titles in exchange for coop¬

eration with a desperate government. Still other groups using folk reli¬

gion and secret doctrine as their cohering element and their justification

for rebellion were mostly, in their eyes and in those of the government,

beyond such compromises.4

3 Hsiao, Ch’i-ch'ing, The military establishment of the Yiian dynasty (Cambridge, Mass., 1978), pp. 62 —

63,46-47¬

4 Examples of all these patterns are the subject of the next section, “The disintegration of central

authority.”

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

RISE OF THE MING DYNASTY

J5

The degenerative process, starting from the administrators’ failure to

maintain law and order and leading to the various kinds of organized

dissidence, has special relevance for the subject of military power in the late

Yuan. That process led to the weakening of the normative controls

throughout society on which social order fundamentally depended and to

their replacement by direct recourse to force. It induced a comprehensive

change from a pacific society to a militarized one. Arms, usually not

present in village households, came to be universally present. As many

males came to possess and to understand arms, those most successful in

their use became military leaders. Each village might produce several, from

corporals to captains, all striving to become generals. In the competition

for military supremacy that ensued from the 1330s onward, a very large

number of competent and a few brilliant military leaders were produced

from the most humble backgrounds. Most of those remained outside the

government’s military establishment in the service of one or another of the

rebellions.

A society once so militarized could only be demilitarized and restored to

unified, civilian management by a long process in which all the competi¬

tors for national leadership but one were eliminated. In military terms, that

is the process that dominated the life of China from about 1330 until the

completion of Chu Yiian-chang’s reunification in the 1380s. As military

history, it is described by Edward L. Dreyer in Chapter 2 of this volume.

Elite and government

The middle decades of the fourteenth century provide a curious spectacle in

the history of later imperial China’s scholarly and social elite. To some it was

a period of hope, largely unfulfilled, that time-honored Chinese ways might

at last prevail over the alien conquerors’ disruptive impact. After completing

his conquest of central and south China in the 1270s, Khubilai Khan had

taken some essential steps toward acknowledging the superiority of Chinese

political institutions for governing the Chinese, and transforming the one¬

sided reliance on the Mongol military machine into a full partnership with

civilian, bureaucratic government. He had patronized Chinese (and sinified

Inner Asian) scholar-officials and had heeded their counsel. In 1271 he

ordered eminent scholar-officials to design a full complement of Chinese

ritual forms for the conduct of his court, while retaining, as the Official

history of the Yuan says, Mongol customs and rituals for affairs involving the

imperial clan and the Mongol nobility.5 He had spurred the recruitment of

5 Sung Lien et al., eds., Yuan shih (1369—70; rpt. Peking, 1976), 67.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

l6 THE MING DYNASTY, 1368-1644, PART I

Chinese scholars for official appointment by recommendation. But, point¬

edly refusing the most important request of his Chinese advisers, he had not

instituted civil service examinations to recruit officials.

In 1313 his great-grandson Ayurbarwada, known to history as the em¬

peror Jen-tsung (1312-20), announced that commencing in 1315 the ex¬

aminations would be reinstated on the Sung model, and would designate as

orthodox the classical exegeses of the Chu Hsi (1130—1200) school. This

aroused a great surge of hope and satisfaction throughout the Chinese

population. When Tugh Temur, Jen-tsung’s nephew, came to the throne

in 1328, that aroused further hope. In his years as Prince of Huai, residing

at Chien-k’ang (Nanking), he had associated with eminent literati and men

of arts. Given the posthumous title Wen-tsung (the cultivated), he appears

to be the Mongol emperor with soundest claims to having been fully

literate in Chinese. In addition, he attempted to write classical Chinese

poetry (two examples survive), to paint, and to produce reasonably satisfac¬

tory Chinese calligraphy.6 The command of Chinese civilization that Khu-

bilai’s son and heir, Prince Chen-chin, might have brought to the throne

had he not predeceased his father in 1285, now after six mostly disappoint¬

ing reigns had found a second imperial incarnation. Moreover, as noted

above, the coup that placed Wen-tsung on the throne represented the

success of the “Confucian” faction in Mongol politics, the one that stressed

the rulers’ interests in a well-run Chinese state.

One of Wen-tsung’s first acts as emperor was to establish in the capital a

new academy of Chinese learning and art as an office of the inner court,

called the K’uei-chang ко.7 At the same time, there were at court several

highly placed nobles like Majartai. His son, Toghto, was to become the

leading advocate of Chinese ways of governing during the final reign of the

dynasty. Majartai was avidly developing contacts with leading Chinese

scholars, hiring them to tutor his sons, and sponsoring Chinese learning at

the court.8 By the fourteenth century many of the privileged Central and

Western Asians (se-mu jen) had become learned, cultivated members of the

Chinese cultural elite, demonstrating the power of Chinese values to as¬

similate aliens. At this time, during the decades from the 1320s to the

1340s, a number of leading classical scholars and literary figures from the

central Chinese heartland of high cultural development served at the Yuan

court, mostly by recommendation and direct appointment, but also by the

6 Herbert Franke, “Could the Mongol emperors read and write and write Chinese?" Asia major, NS 3

(1952), pp. 28-41.

7 Chiang I-han, Yuan tat k'uei chang ko chi k’uei chang ko jen wu (Taipei, 1981).

8 John D. Langlois, Jr., “Political thought in Chin-hua under Mongol rule,” in China under Mongol

rule (Princeton, 1981), esp. pp. 169 ff. See also Langlois, “Yu Chi and his Mongol sovereign,"

Journal of Asian studies 38, No. 1 (November, 1978), pp. 99—116.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

RISE OF THE MING DYNASTY

П

newly opened examination route. Throughout, young men had continued

to train in classical learning in preparation for scholar-official careers,

unable to believe that the great norms of their civilization would not again

prevail. During the first half of the fourteenth century private academies,

through which the elite assumed enlarged responsibilities for maintaining

such education, flourished. A number of important regional and local

centers of learning emerged: Chin-hua in northern Chekiang emphasized

classical learning in the support of statecraft and produced scholars eager to

find activist, positive roles in government. Many figures prominent in that

school during the final decades of the Yuan went on to serve prominently at

the early Ming court and to dominate early Ming learning and statecraft.9

The significance of this discussion of elite attitudes and activities is

that the Chinese elite in general accepted the legitimacy of Mongol rule

and strove to maintain traditional patterns of government participation.

They never achieved full acceptance from their Mongol overlords. Even

Wen-tsung had reigned only four years, and ineffectually. Many discour¬