Текст

4-m

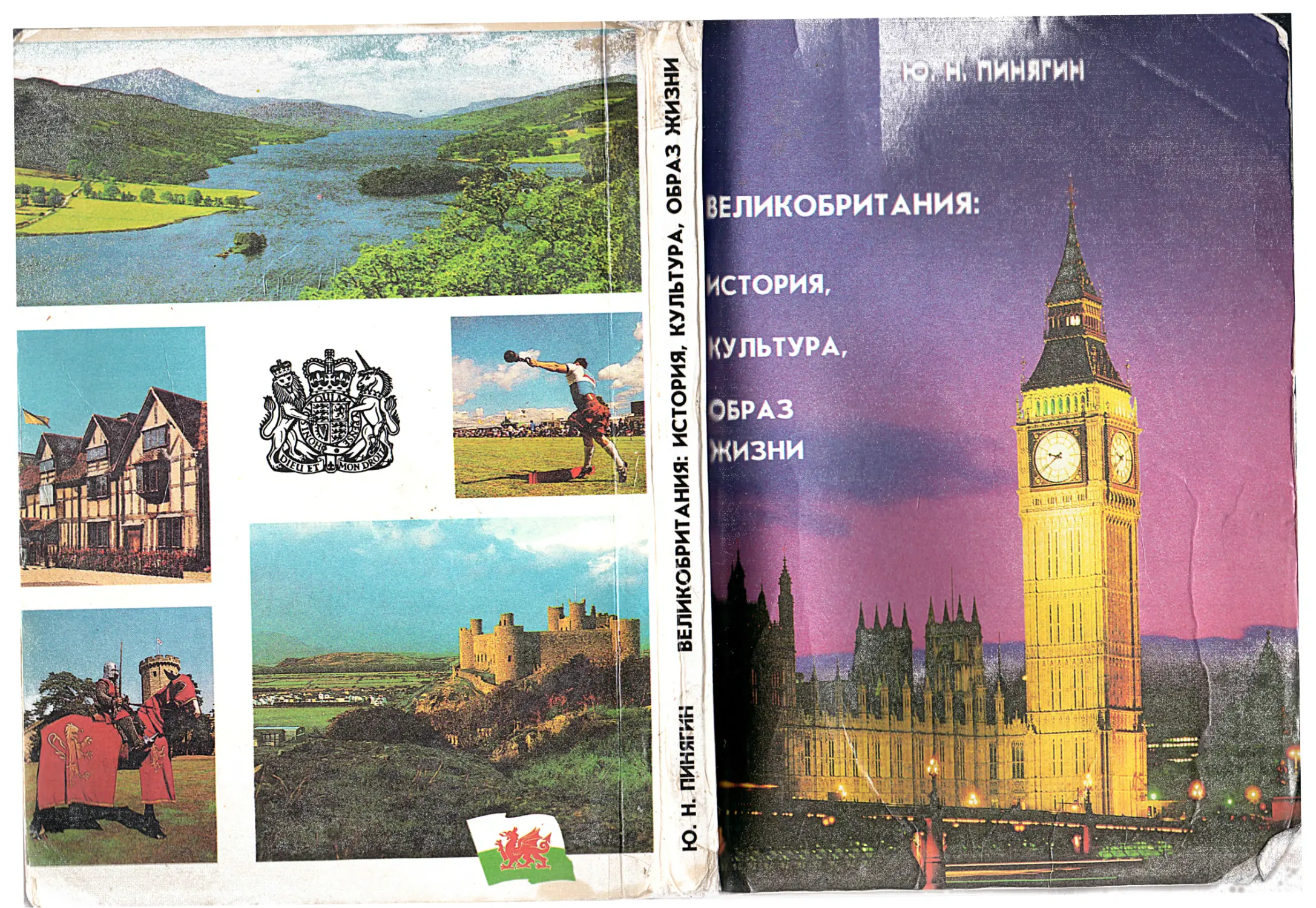

ю. н. пинягин

ВЕЛИКОБРИТАНИЯ :

ИСТОРИЯ, КУЛЬТУРА, ОБРАЗ ЖИЗНИ

Лингвострановедческий очерк

йЗЬ^Опсихопоги.<

Издательство Пермского университета

Пермь 1996

ББК 63.3/4=Вл/-7

П32

Редактор Л.А. Богданова

Рецензенты: профессор Алан МакГиллври, университет

Стрэтклайда, Глазго /Шотландия/; доцент Пермского

педагогического университета И.В. Егорова

Печатается в соответствии с решением редакционно-изда-

тельского совета Пермского университета

ПИНЯГИН Ю.Н.

П32 Великобритания: история, культура, образ жизни

лингвострановедческий очерк. - Пермь: Изд-во Перм. ун-та, 1996»

296 с.

ISBN 5-8241 - 0113 - 2

Книга является первой попыткой системного описания

Великобритании с лингвострановедческой точки зрения. Основное

внимание уделяется освещению гуманитарных аспектов - истории,

культуре, образованию, средствам массовой информации, традициям

и образу жизни.

Для студентов и аспирантов романо-германской специальности,

а также преподавателей, читающих курс страноведения.

The book attempts to give a systematic description of the

background information on Great Britain. It embraces the issues

which constitute the core of information essential for the

Russian learners of English. For this reason the author

concentrated on such aspects as history, culture, education,

mass media, traditions and way of life.

4602020102 - 9

П--------------- Без объявл.

H 55(03)-96

ISBN 5 - 8241

0113

С) Ю.Н.Пинягин 1996

2

ПРЕДИСЛОВИЕ

Автором предпринята попытка системного описания Великобрита-

нии с лингвострановедческой точки зрения. Книга содержит матери-

ал, охватывающий круг вопросов, которые являются предметом изу-

чения студентов романо-германских специальностей. Представленная

в ней разнообразная информация дает возможность преподавателю,

читающему курс страноведения, самому определить его оптимальный

объем. Отдельные главы и разделы книги могут использоваться ас-

пирантами и студентами по истории Англии, Шотландии, Уэльса, ис-

кусству Великобритании и т.д.

В основе создания книги заложено несколько принципов, важ-

нейшим из которых является лингвострановедческий, направленный

на раскрытие и объяснение специфических черт британской истории,

культуры и образа жизни средствами английского языка. Вследствие

этого у читателя могут возникнуть проблемы в понимании отдельных

абзацев, которые можно разрешить, обратившись к известному линг-

вострановедческому англо-русскому словарю ’’Великобритания” . Тем

не менее автор попытался сделать все возможное, чтобы работа с

материалом не вызывала непреодолимых трудностей у читателя, для

которого английский язык не является родным.

Второй принцип, который последовательно реализуется в книге,

- это объяснение причин многих исторических событий, происхожде-

ния британских институтов и их оценка с точки зрения современ-

ности. Это, по мнению автора, необходимо для понимания многих

аспектов жизни такой страны, как Великобритания. Глава о нацио-

нальных традициях не большая по объему, и поэтому автор не пре-

тендует в ней на полное их освещение, однако многие традиции и

традиционные процедуры описаны в соответствующих главах и разде-

лах, в частности посвященных Шотландии и Уэльсу.

Третий принцип, логически вытекающий из предыдущих, - это

описание основных событий в истории Англии, Шотландии и Уэльса

4

таким образом, как оценивают их национальные историки, т.е. так,

чтобы национальная история и самобытность не растворились в по-

нятии "история Великобритании". Это представляется исключительно

важным для понимания исторических фактов прошлого и некоторых

специфических проблем, с которыми сталкивается Великобритания

сегодня. Такой подход, насколько известно автору, осуществляется

впервые в курсе страноведения Великобритании, ибо ранее преобла-

дал так называемый "общебританский" подход к пониманию и оценке

истории и культуры этой многонациональной страны.

Для автора этой книги главным в освещении исторического раз-

вития Великобритании было установление причинно-следственных

связей событий и повествование о людях, в них участвовавших, с

целью объективного осознания исторических процессов, которые, в

конечном счете, и определили судьбу одной из самых устойчивых

демократий в Европе. Это понимание для нас особенно важно в нас-

тоящее время, так как Россия ищет свой путь к демократии, пре-

тендующей на европейский уровень.

PREFACE

Myself a Russian, I have known Great Britain for most of my life as a

tolerant and kindly hostess and I trust that my national detachment has been

more help than hindrance in the pleasures of appreciation.

This book is intended for the Russian learners of English at university

level and is aimed at giving an overall coverage of Great Britain and at the

same time portraying the most essential features of the three countries

comprising it. An inquisitive reader can find lots of material both on the

main aspects of life and just something very particular to satisfy one's

professional interests. I have had in mind, while making my choice, the

Russian learners of English who are entering upon the discovery of the British

heritage in history, culture and traditions and in the richly diverse fabric

of the British way of life. I have therefore made my selection with an eye to

their needs and have included explanations that may seem obvious to those more

fully equipped with the knowledge of the subjects discussed.

With such a mass of material the problems of covering the essentials and

of rejecting, out of necessity, what others will think essential, have been

inevitably severe. There was so much that I wanted to put in and so much that

I had to leave out. This explanation is necessary since there is bound to be

regret, and even astonishment, that certain places and names are not to be

found. These absentees are not the victims of neglect; many things considered

were reluctantly passed over, for reasons of space.

My gratitude goes to those who have invited me to undertake this task and

assisted me in its execution. I am extremely thankful to the British Council

(Moscow) and the British Council (Glasgow) branches for their sponsorship and

support. During the period of two years that I spent working on the book,

I always appreciated the understanding and sincere support of Mr Mark Evans,

Director of the British Council Moscow branch. I am also indebted to Dr Martin

Montgomery and his colleagues at the Department of English Studies of the

University of Strathclyde, and to Professor Alan MacGilliveray who was always

ready with advice in the shaping of the "style and usage". I would like to

lhank all who have come to my aid: the staff of The Andersonian Library of the

University of Strathclyde in Glasgow, and Mr Peter 3. Westwood, Honorary

President of the Burns Federation, who gave expert assistance on Ayr and the

creative work of Robert Burns. While working on the book in Scotland I could

nut be impartial to the people who surrounded me, so probably one would find

the chapter on Scotland somewhat biased, but it only reflects the strong

positive impact Scotland produced on me.

- 6 -

Several friends in England helped me at various stages in the planning and

executing of this project. I am particularly obliged to Tony and Christa

Gillett, and John and Barbara Greening who inspired me and helped to shape

some articles of the book. I am also grateful to Douglas and Karen Hewitt, Roy

and Deborah Manley, and John and Linda Ward, who were most generous in sharing

their views on some aspects of life in Great Britain and helped me to under-

stand the role.and functions of the British institutions. I am grateful to

Mi Christopher Schuman who kindly revised the material and contributed to

the texts.

The author gratefully acknowledges the co-operation of Her Majesty’s

Stationery Office and the Central Office of Information who have given

permission for the materials of Crown Copyright ’’Britain 1993: an Official

Handbook” to appear in these pages.

I could not possibly have written this brief account of history, culture

and the way of life in Great Britain without considerable help from a number

of editors. I am extremely grateful to the following for permission to

reproduce copyright material:

An Illustrated History of Britain by David McDowall, Longman 1993.

Anglistik & Englischuhterricht in Scotland: Literature, Culture, Politics.

Band 38/39. Heidelberg, 1989. Great Britain: Its History from Earliest Times

to the Present Day, by T.K. Derry, C.H.C. Blount, and T.L. Jarman. Oxford

University Press 1962. The New Wales. Ed. by David Cole. University of Wales

Press 1990. Life in Modern Britain, by Peter Bromhead. Longman Group Limited

1993. Scotland: A Concise Cultural History, 1993. Mainstream Publishing Co.

(Edinburg) Ltd. The Xenophobe’s Guide to the English, by Antony Miall. Oval

Projects Ltd., 1993.

I hope that the reader will find here much that will help his under-

standing of the nation’s life, history and culture. This book combines facts

and my own observations and is like a portrait whose subject changes in its

details while the artist draws. It is in this manner that I have interpreted

my commission to compose the book and in this manner that I have tried to

catch t^he likeness in its latest phase.

- 7 -

GREAT BRITAIN IN PROFILE

Britain forms the greater part of the British Isles, which lie off the

north-west coast of mainland Europe. The full name is the United Kingdom of

Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Great Britain comprises England, Wales and

Scotland. The area totals some 242,500 sq km. Britain is just under 1,000 km

long from the south coast of England to the extreme north of Scotland, and

just under 500 km across in the widest part. With some 57 million oeople,

Britain ranks sixteenth in the world in terms of population. The population

has remained relatively stable over the last decade, but has aged. Britain is

a relatively densely populated country. England has the highest population

density of the four lands and Scotland the lowest.

The British tendency to moderation perhaps reflects the climate, which is

exceptionally moderate: not too hot or cold, not too wet or dry. The tempera-

ture rarely goes below -5°C or over 25°C. But the weather is often dull and

damp with too little sunshine. The frequent winds make it feel colder than it

really is. July and August are sometimes fine, but more often miserable. There

ore no great differences of climate between the sections of the UK, except

that the west has more rain than the east, and the northern mountains,

particularly in Scotland, have much more rain and snow. More generally, the

southern parts of England and Wales are a little warmer, sunnier and less

misty than the rest.

Within England the eight administrative regions do not have strong

cultural identities of their own. The styles of architecture do not vary,

though there are parts of the south-west and north where stone houses were

more common until recently than the red brick houses which predominate in most

nt tier regions. There is a clear difference between the northern way of speak-

ing English and the southern way, though each has local variants and each is

ilif trrent from what has been called ’’standard English” or "received pronun-

< iiition", which has no regional basis and is spoken by about 3 per cent of the

pr>i|il(.', scattered around the country.

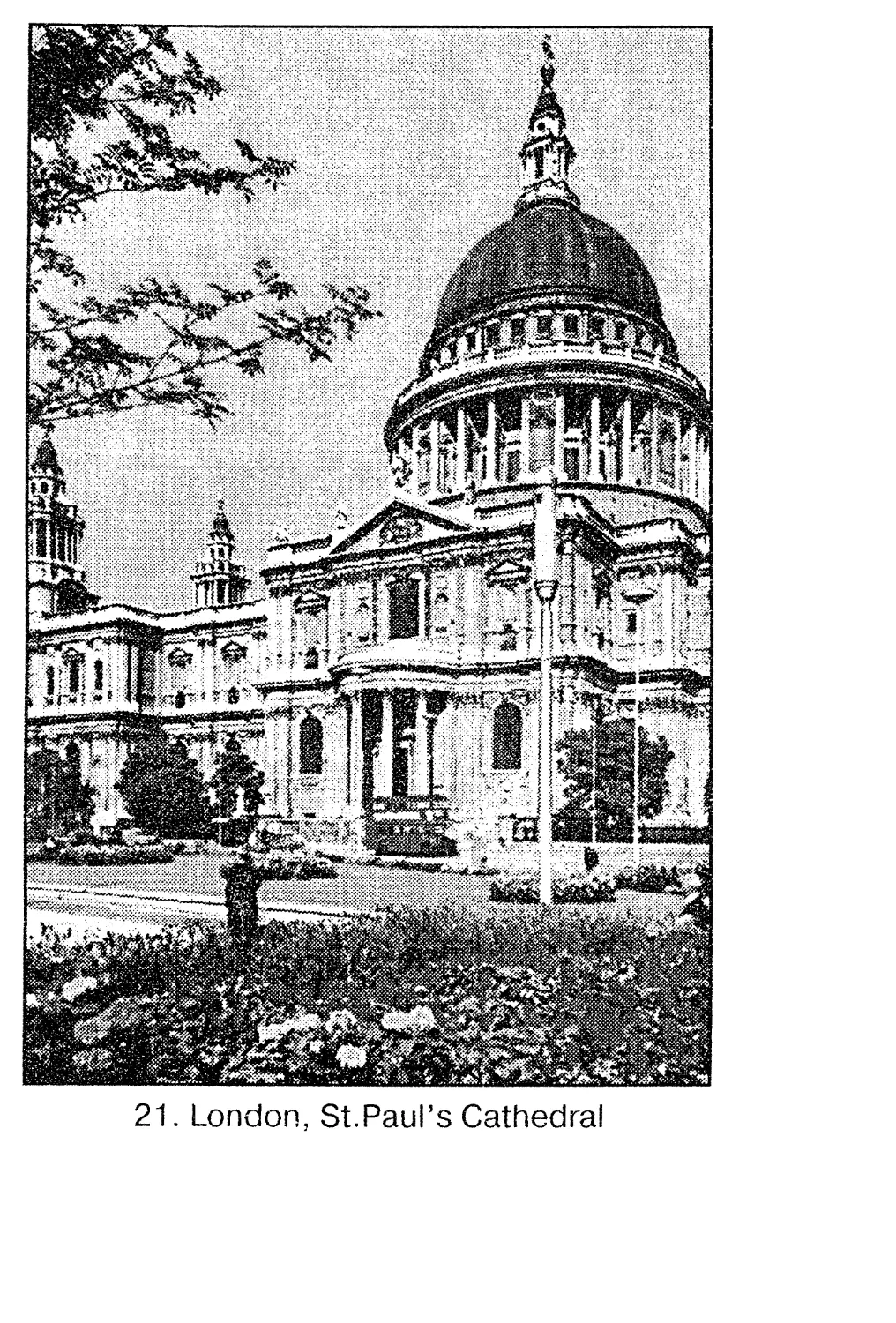

london’s dominant position has been strengthened by the needs of modern

I lines, lor 100 years the central government has extended its responsibilities,

partly by undertaking functions which were not performed at all before. With

Hinny local problems local representatives go to London to see central govern-

inriil officials. The main newspapers and publishers have their offices in Lon-

.. .. no loo do the advertisers and producers of television programmes. Like

I I liner I ngI and suffers, as compared with Germany, Italy and Spain, from exces-

nivo cinicc.nlration of cultural life as well as business in a giant capital.

- ь -

London has changed n great den) in Lt*e past f ifty years, and is now more

tolerant and easygoing than it used to be, with its society less consciously

stratified. Far fewer people live in its central areas than fifty years ago.

The air is now polluted more by petrol fumes than by smoke. There are no

longer any of the yellow-black winter fogs that once shut out the sun.

A large proportion of the more prosperous city workers now live in distant

suburbs, but there are a few rather small fashionable residential districts in

the West End of London — though Mayfair, south of Oxford Street, now consists

of offices. In summer, London is now full of foreign visitors, but those who

see London as though it were the whole country are mistaken.

Outside of London the southern half of England had for a long time more

people than the rest of Britain. But from about 1800 the industrial revolu-

tion brought enormous development to the English north and midlands, to the

Clyde estuary in Scotland and to South Wales. These were the areas rich in the

coal to power the machines in the factories, and there was wool from the sheep

on the nearby hills. By 1850 Manchester was a major industrial and commercial

centre, with cotton mills mainly in the towns around it.

When people speak of the industrial north they think mainly of Lancashire

and Yorkshire. Between .the great port of Liverpool in the west and the smaller

port of Hull in the east, the big cities of Manchester, Sheffield, Leeds and

Bradford, along with some twenty big factory towns, form a great industrial

belt. Some of the buildings there are still black from smoke, some have been

cleaned, and some demolished.. Further to the north-east, Newcastle upon Tyne

is the centre of another industrial area, which is based on coal, iron, steel

and shipbuilding.

But more than half the northern land area is sheep country, where the

bleak moors of the Pennines have fine scenery and the valleys have picturesque

villages. Many of the shepherds’ cottages and village houses are now holiday

and weekend homes for the people of the towns.

Not far to the south of Lancashire, Birmingham is the centre of the West

Midlands conurbation. This is as big as Manchester’s and has a vast variety of

industries, particularly engineering. All through the east midlands there are

other manufacturing towns, big and small, as well as coalmines.

Apart from London, the south has fewer big towns and far fewer smokestack

industries than the north. Except for quite small.moorlands it has almost no

hills too high for cultivation. Most of it is undulating country with hundreds

of small market towns. With its lack of heavy industry and its slightly

sunnier and milder.climate the south is more agreeable to some people than the

- 9 -

north, though it has less good scenery. In the past fifty years its relative

advantages have grown. Being nearer both to London and to the Continent it has

had easier connections with the outside world. The south's economy has adapted

itself more easily than the north's to the needs of the late twentieth centu-

ry, and it is the main base of the most modern industries and enterprises.

More people stay at school after the age of sixteen, more go to university,

fewer are unemployed, more have middle-class jobs. More have cars, more own

their own homes and more have central heating. Health is better: fewer people

die of bronchitis or of other illnesses associated with poor living conditions

pollution or bad diet. Fewer vote for the Labour Party. It is sometimes said

that there are two nations, north and south, with a growing division between

the two.

Who are the British? Many foreigners say "England" and "English" when

they mean "Britain", or the "UK", and "British". This is very annoying for the

5 million people who live in Scotland, the 2,8 million in Wales and 1,5 mil-

lion in Northern Ireland who are certainly not English. However, the

people from Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and English are all British.

"The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland" is the politi-

cal name of the country. Great Britain is the name of the island which is made

up of England, Scotland and Wales and so, strictly speaking, it does not in-

clude Northern Ireland. This book centres on the description of these three

nations, the history and cultures of which were and still are, so closely

interconnected.

It took centuries to form the United Kingdom, and a lot of armed struggle

was involved. In the fifteenth century, a Welsh prince, Henry Tudor, became

King Henry VII of England. Then his son, King Henry VIII, united England and

Wales under one Parliament in 1536. In Scotland a similar thing happened. The

King of Scotland inherited the crown of England and Wales in 1603, so he be-

came King James I of England and Wales and King James VI of Scotland. The

Parliaments of England, Wales and Scotland were united a century later in 1707.

The Scottish and Welsh are proud and independent people. In recent years

I here have been attempts at devolution in the two countries, particularly in

Scotland where the Scottish Nationalist Party was very strong for a while.

However, in .a referendum in 1978 the Welsh rejected devolution and in 1979 the

Scots did the same. So it seems that most Welsh and Scottish people are not

tiiiolnst this union, even though they sometimes complain that they are domina-

ted by England, and particularly by London.

lhe whole of Ireland was united with Great Britain from 1801 up until 1922.

- 10 -

In that year the independent Republic of Ireland was formed in the South,

while Northern Ireland became part of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and

Northern Ireland.

The flag of the United Kingdom, known as the Union Jack, is made up of

three crosses: the English cross of St George (a red cross on a white field),

the Scottish cross of St Andrew (a diagonal white cross on a blue field) and

the Irish cross of St Patrick (a diagonal red cross on a white field).

The English. Almost every nation has a reputation of some kind. The French

are supposed to be amorous, gay, fond of champagne; the Germans dull, formal,

efficient, fond of military uniforms, and parades; the Americans boastful,

energetic and vulgar. The English are reputed to be cold, reserved people who

do not yell in the. street, make love in public or change their governments as

often as they change their underclothes. They are steady, easy-going, and fond

of sport.

The Russians’ view of the English for a long time was based on the type of

Englishman they read about in the novels by Dickens and Galsworthy. Since

these were largely members of the upper and middle classes, it is obvious that

their behaviour cannot be taken as general for the whole people. There are,

however, certain kinds' of behaviour, manners and customs which are peculiar to

England.

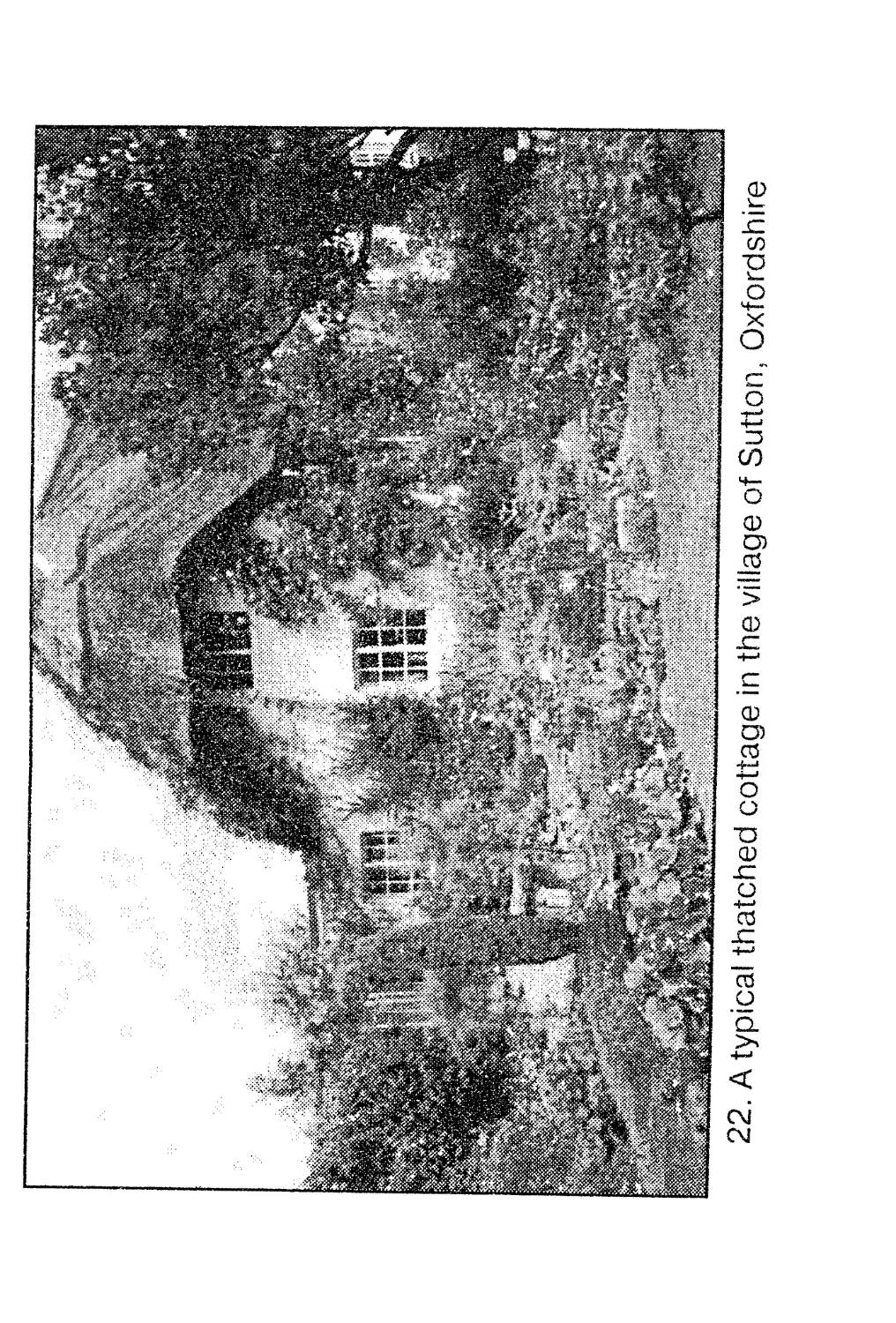

The English are a nation of stay-at-homes. There is no place like home,

they say. And when a man is not working he withdraws from the world to the

company of his wife and children and busies himself with the affairs of the

home. "The Englishman's home is his castle", is a saying known all over the

world; and it is true that English people prefer small houses, built to house

one family. A garden is an indispensable feature of any house there (see ill.

22-23).

The fire is the focus of the English home. What do other nations sit

round? The answer is they don't. They go out to cafes or sit round the cock-

tail bar. For the English it is the open fire and the ceremony of English tea.

Even when central heating is installed it is kept so low in the English home

that Americans and Russians get chilblains, as the English get nervous head-

aches from stuffiness in theirs.

Apart from the conservatism on a grand scale which the attitude to the

monarchy typifies, England is full of small-scale and local conservatisms,

some of them of a highly individual or particular character. Regiments in the

army, municipal corporations, schools and societies have their own private

traditions which command strong loyalties. Such groups have customs of their

- 11

own which they are very reluctant to change, and they like to think of their

private customs as differentiating them, as groups, from the rest of the world.

Most English people have been slow to adopt rational reforms such as the

metric system, which came into general use in 1975. They have suffered

inconvenience from adhering to old ways, because they did not want the trouble

of adapting themselves to new. All the same, several of the most notorious

symbols of conservatism were abandoned, as for example, the old system of money

which was substituted by the decimal system in 1971.

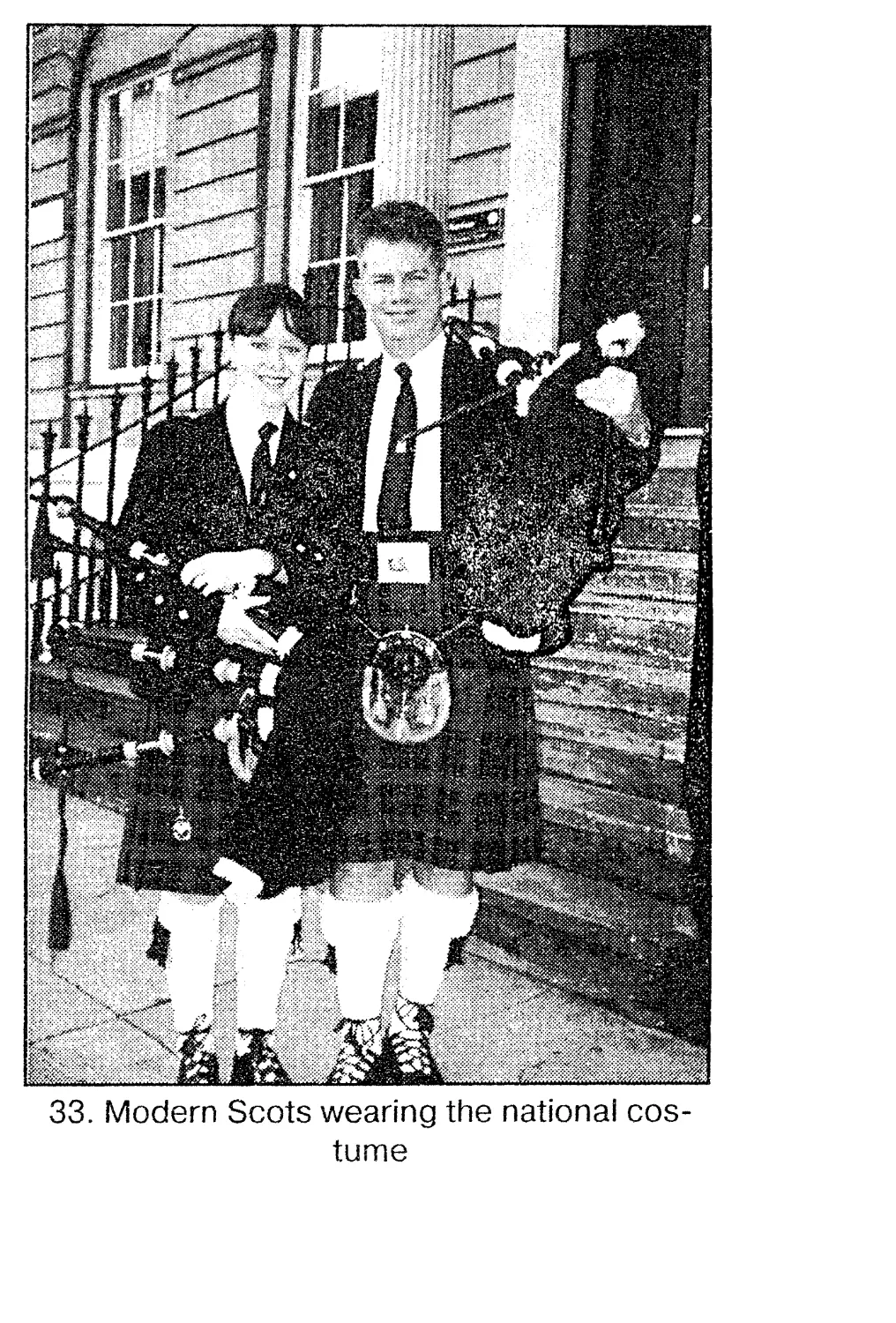

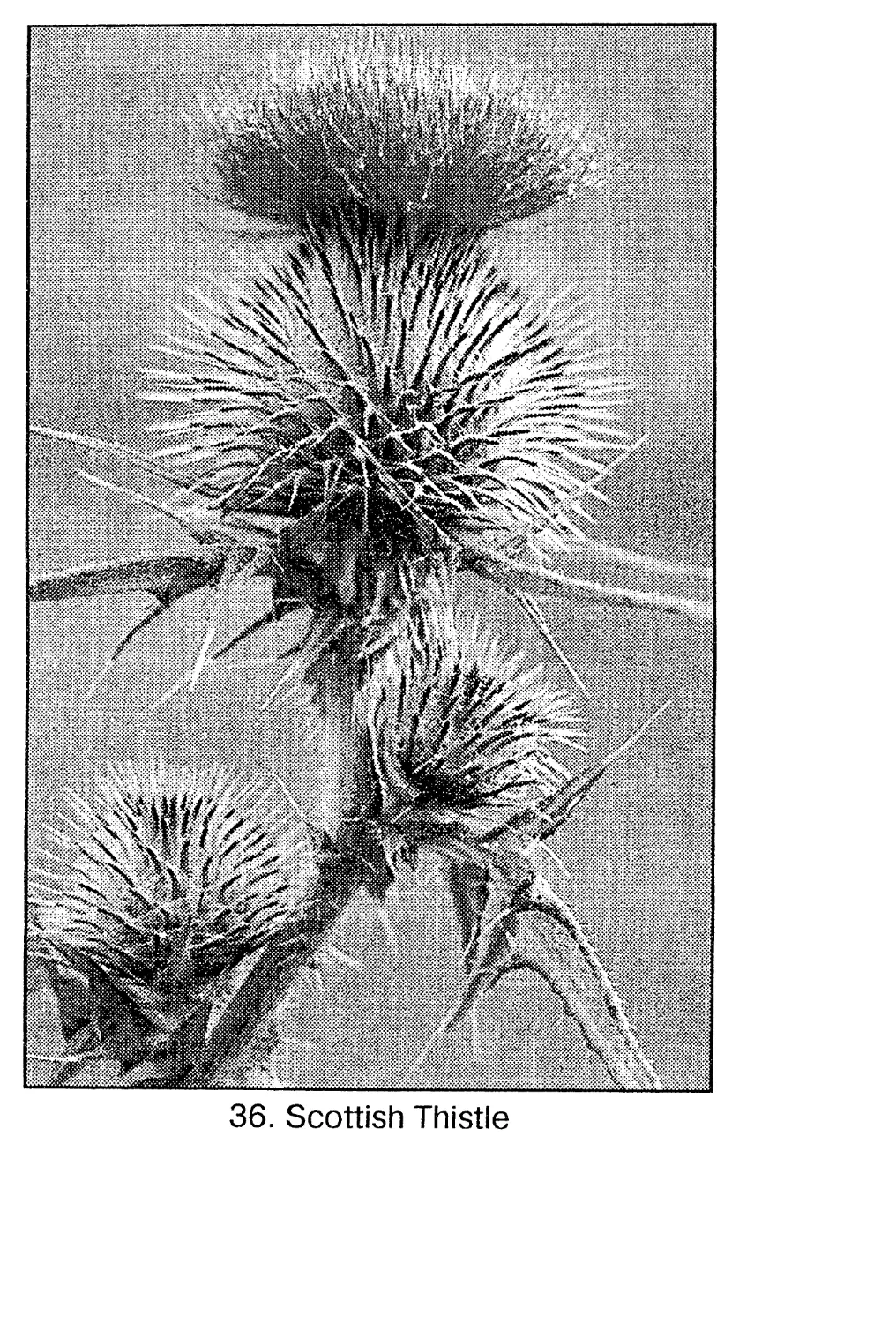

The Scots. The Scots are not English. Nor are the Scots British. No self-

respecting Scot calls himself a Briton. The words Briton and British were

uneasily disinterred after a long burial as a kind of palliative to Scottish

feelings when their Parliament was merged with the English one at Westminster.

But the attempt was not successful. The best things on either side of the

Border remain either English or Scottish. Are Shakespeare and Burns British

poets? When Australians play football (that was born on the fields of England),

do they play a British game? And is there anyone in the whole world who has

over asked for a British whisky?

The two nations have each derived from mixed sources, racially and, as it

were, historically. Each has developed strong national characteristics which

separate them in custom, habit, religion, law and even in language.

The English are amongst the most amiable people in the world; they can

so be very ruthless. They have a genius for compromise, but can enforce

I heir idea of compromise on others with surprising efficiency. They are gene-

rous in small matters but more cautious in big ones. The Scots are proverbial-

ly kindly, but at first glance are not so amiable. They abhor compromise, lean

much upon logic and run much to extremes.

In general the nation of modern Scotland derives from three main racial

sources. The Celts, the Scandinavians and the mysterious and shadowy Picts.

Thuac Picts were the first inhabitants of what we now call Scotland. They were

о small tough people and have left their strain in the blood and occasional

marks Ln the land and language. They were conquered by the invading Celts from

Ireland who, incidentally, were called Scots and from whom the name of modern

nation- comes.

Ihrec centuries later, however, the Celts retreated into the north-western

hllla and islands, their place in the east and south lowlands being taken by

llu; Scandinavians and Angles. Hence the celebrated division of the Scottish

iwiiiplo into Highlanders and Lowlanders. It was a division which marked the

•HatInclion between people of different culture, temperament and language. It

- 12 -

is from the Celts that there comes the more colourful, exciting and extrava-

gant strain in the Scots: the Gaelic language and song, the tartan, the

bagpipes, the Highland spirit and so on. It is from the Lowland strain that

there comes the splendid courage in defence, providing a complementary virtue

to the splendid Highland courage in attack.

Since the break-up of the old Highland system in the eighteenth octury

the Scots became so mixed up in blood that most of them combine something of

the characteristics of both Highlander and Lowlander. All Scots living north

and west of the Highland line which, geographically speaking, still runs dia-

gonally across Scotland were true Celtic Highlanders. That is to say they

spoke the Gaelic language, lived under the ancient Celtic system of land te-

nure and, of course, as members of clans, bore Highland names. South and east

of that line in the Lowland towns, villages and in the countryside, Highland

names were rare.

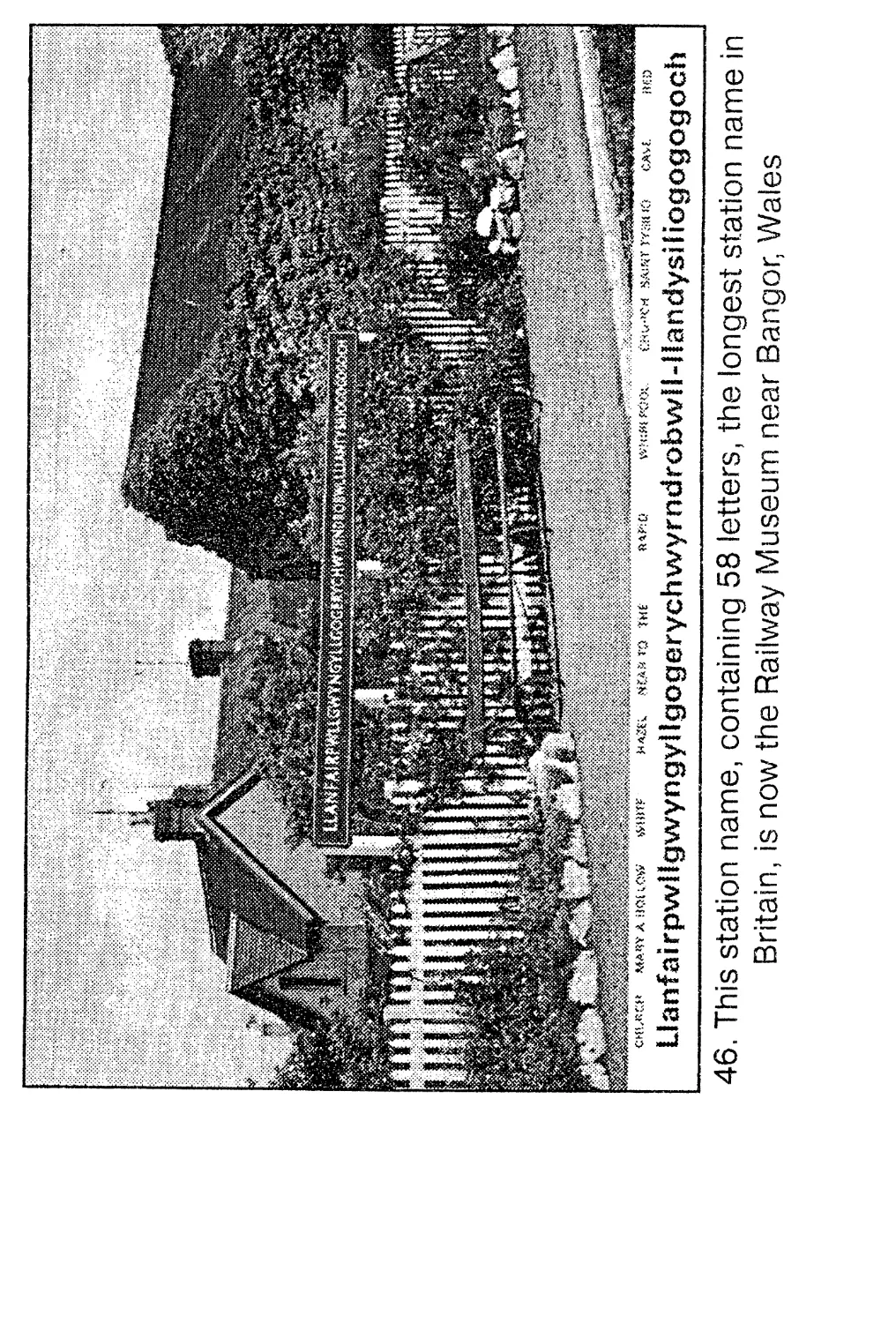

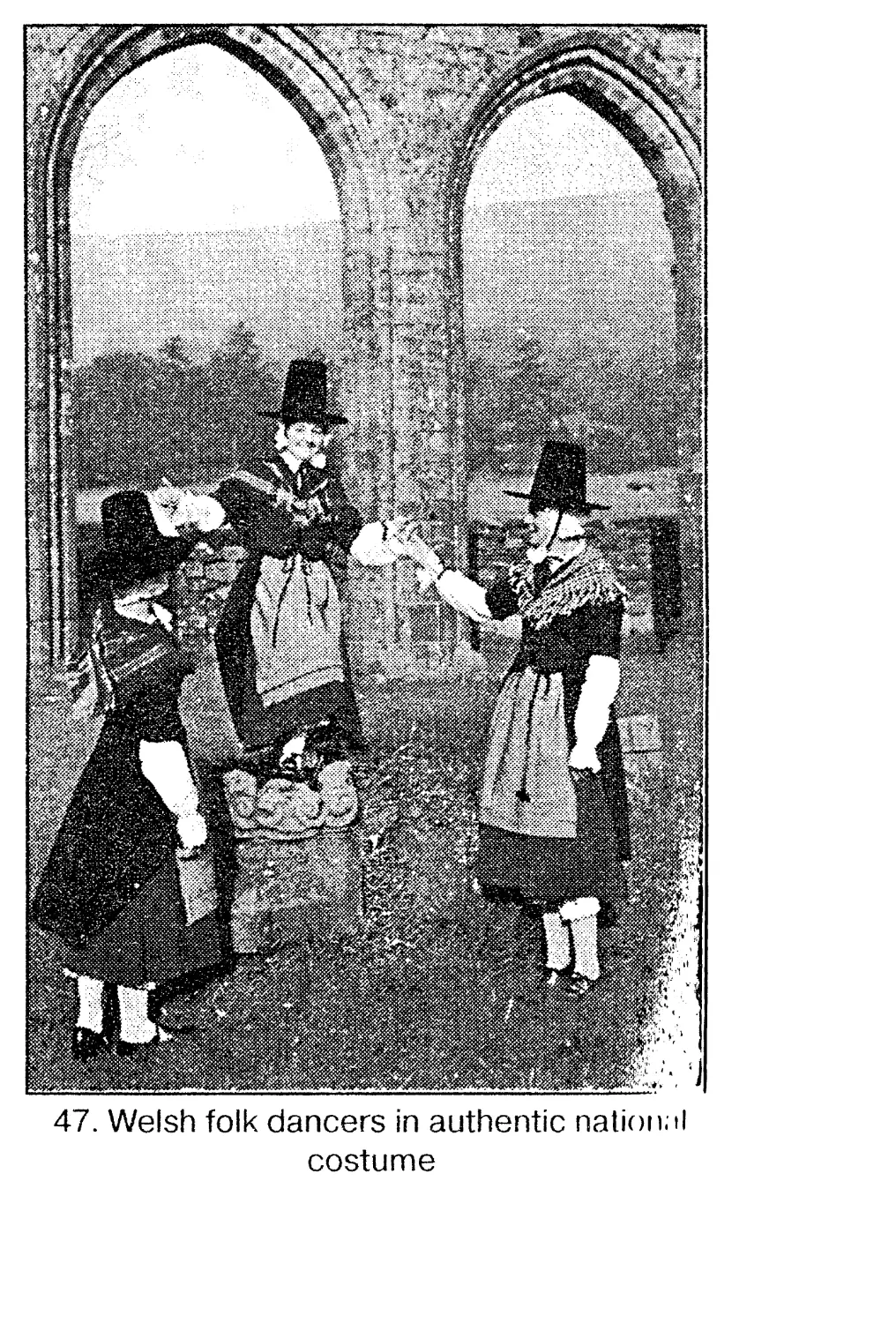

The Welsh. The national spirit in Wales is very strong and many tradi-

tions are cherished there. The Welsh wear their national dress on festive

occasions (ill. 47); the Welsh language is still very much a living force and

is taught side by side with English in schools; and Welshmen, who have a high-

ly developed artistic sense, have a distinguished record in the realm of poet-

ry, song and drama.

Welsh history begins with the Anglo-Saxon victories in the sixth and

seventh centuries which isolated the Welsh from the rest of the Celtic popula-

tion of Britain. Henceforth the people of Wales were vulnerable on two fronts:

on the east they were constantly harried by the English chieftains, and until

the eleventh century the vikings made frequent raids on the coasts. Then came

the Normans who penetrated into the south of the country and established many

strongholds, in spite of strong resistance organised by the Welsh. Eventually,

however, the subjection of the people was completed by Edward I, who built ma-

ny castles and made his soq the first Prince of Wales.

The population of Wales amounts to about three million. The Welsh language

is a Celtic branch of the Indo-European languages and has some roots in common

with them. The Welsh call their country Cymru, and themselves they call Cymry,

a word which has the same root as "camrador" (friend). All over Wales children

at schools are required to spend some time learning Welsh, though many of them

do not remember much beyond the correct pronunciation of place names. At the

1981 census 19 per cent of the whole population claimed that they could speak

Welsh, as compared with 29 per cent in 1951.

Summing up some of the national characteristics of the people living in

- 13 -

Britain, one may say that the things they agree about make them British; the

things they disagree about make them interesting.

(Based on P. Bromhead. Life in Modern Britain)

AN OUTLINE OF BRITISH HISTORY

Some Dates in British History

55 and 54 BC, Julius Caesar's expeditions to Britain

AD 43, Roman conquest begins

122-38, Hadrian's Wall built

409, Roman army withdraws from Britain

450s onwards, foundation of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms

B32-60, Scots and Picts merge to form what is to become the kingdom of Scotia

U60s, Danes overrun East Anglia, Northumbria and East Mercia

1066, William the Conqueror defeats Harold at Hastings and takes the throne

1086, Doomsday survey

1215, King John signs Magna Carta, to protect feudal rights of the barons

1157, Hundred Years War between England and France begins

I Mil, Peasants' Revolt in England

1455-87, Wars of the Roses, between Lancastrians and Yorkists

ГН4-40, English Reformation: Henry VIII breaks with the papacy

Г»16 42, Acts of Union unite England and Wales

Г*4/ 53, Protestantism becomes official religion in England under Edward VI

l*»5 5 >H, Catholic reaction under Магу I

I••••II |6U5, Reign of Elizabeth I. Moderate Protestantism established

Г'ПИ, Did ent of Spanish Armada

Г»,/Ц 1л 15, Plays of Shakespeare written

H.42 '»|, Civil War between King and Parliament

h.44, I xucution of Charles I

Ia‘.1 Ч1, (Jliver Cromwell rules as Lord Protector

InMl, Krnloration of the monarchy under Charles II

|л11П. Glorious Revolution: Accession of William III and Магу II

I/и/, Л<1 of Union unites England and Scotland

I /oil III Ml, Industrial Revolution

Illi/ 1'411, Hcltjn of Queen Victoria

IмИ III, I I nit World War

I’ll’/ »»'., '.ocoimI World War

l‘»/|, Ih Ihiln nnluni European Community

- 14 -

Earliest Times

Britain's prehistory. The Celts. The Romans. About 2400 BC there came the

men from the continent who brought neolithic (New Stone Age) culture to Bri-

tain. A little later an even more important wave of immigrants, Iberians, com-

ing from Spain colonized Ireland, the coastline of Britain and the extreme

north of Scottish mainland. The most important contribution of these settlers

to the development of Britain was their discovery and use of copper, gold and

also tin in Cornwall. Salisbury Plain was the centre of this civilization and

Stonehenge (ill. 1) is its greatest surviving monument. It was erected about

1500 BC, and the precise purposes of Stonehenge remain a mystery, but it was

almost certainly a sort of capital, to which the chiefs of other groups came

from all over Britain.

About 1000 BC invaders from Europe started to come again and the newcomers

were the Celts. Britain has taken its name from one branch of them, the

Britons, because this was the people whom the Romans first met in their occu-

pation of the island, and the name Britannia which the Romans therefore gave

to it has stuck. The Celts imposed their language on the whole of Ireland and

Britain, and it still survives in different forms in Ireland, Wales and

Scotland. They brought' with them iron weapons and tools, which enabled to be-

gin the move from the poor light soils to the richer heavier soils. The centre

of wealth and civilization shifted to the region of the Thames estuary with

towns on the sites of present-day St Albans and Colchester.

The Celtic tribes were ruled over by a warrior class, of which the priests

or Druids, seem to have been particularly important members. These Druids

could not read or write, but they memorised all the religious teachings, the

tribal laws, history, medicine and other knowledge necessary in Celtic society.

The Druids from different tribes all over Britain probably met once a year.

They had no temples, but they met in sacred groves of trees, on certain hills

or by rivers. Stonehenge is supposed to be one of their meeting places.

During the years of 60 to 55 BC Julius Caesar conquered the whole of Gaul

(modern France) for the Romans. There was a close connection between Gaul and

Britain in culture, language and trade, and the British gave help to the

people in Gaul against the Romans. This brought Caesar across the Channel

twice in 55 and 54 BC to put a stop to this help and also to explore the

island, but the conquest did not begin until AD 43 — nearly one hundred years

later. In the meantime trade between Britain and Roman Gaul and the import of

luxury goods from the Roman Empire grew so much that the nobles in Britain

were to a great extent converted to Roman ways of living. Thus by AD 43 Roman

- 15 -

trade and culture had already prepared the way for Roman conquest. By 47 all

the lowlands up to the rivers Severn and Trent had been conquered by the army

of the Emperor Claudius. The Romans could not conquer "Caledonia", as they

culled Scotland, although they spent over a century trying to do that. Later

on, in 122-28, the Emperor Hadrian constructed a great defensive wall across

Britain at the Tyne — Solway isthmus (ill. 2) and the Emperor Antonius built

и second wall at the Forth — Clyde isthmus about 142. Both of these walls

were aimed at stopping the highland tribes from attacking the Romans from the

north and they remained the most impressive of all monuments of the Roman occu-

pation of Britain.

Iho Saxon Invasion

The Invaders. Christianity. The Vikings. Britain remained the province of

tho Roman Empire for four hundred years. It was not colonized by the Romans as

it had been by the Celts and was to be by the English. It was an outlying pro-

vince of a unified empire, ruled from Rome. High officials and senior army

offleers came to Britain for a tour of duty and returned home when it was overj

innrchnnts also came and went, though some perhaps settled in Britain.

Under Roman rule Britain enjoyed two and a half centuries of peace, of com-

plete freedom from foreign invasion and internal war. This remains to this day

llwi longest such period in British history. During this period most of the

•Ivll population ceased to possess weapons and the skills to use them. The

iiiwnti had walls and trained men to defend them, but apart from this Britain

i!'i|inii(lcd on the professional army for defence. This was one of the reasons why

Ih llaln was so quickly conquered by foreign invaders when the Roman Empire

in «4*1’ down.

I Im Romans left about twenty large towns and almost one hundred smaller

niitiii. Миру of these towns were at first army camps, and the Latin word for

• limp, "cunira", has remained part of many town names to this day (with the end-

ing tliohler, caster or cester): Winchester, Lancaster and many others. London

min <i rnpitnl city of about 20,000 people and was twice the size of Paris, and

|iiMinilily the most important trading centre of northern Europe. Magnificent

nhHirt pnvrid rnnds formed a network radiating out to all the provinces from

liiinliiii. '.riiltcrcd all over the lowlands are the remains of the villas of the

a — Britons, for the most part, who had prospered under Roman rule

nod iiiiiipird the Roman style of living. These varied between mansions and

H"dnnl f in idiouecfi in accordance with the amount of land that went with them.

Iln Uni и 11 ri of the social life of the Romano-Britons are still being made

iIhuiih lliniiiijh I hr ntudy of the remains of these villas, with their hot-air

- 16 -

heating systems, mosaic decorations and shrines for religious worship.

In the military area,north and west of central Britain,life was quite dif-

ferent. The tribes of Wales and Scotland had not been converted to Roman ways

of living and were held down only by force based on a network of military

forts. The immense effort was put into building Hadrian’s and the Antonian

Walls to keep these tribes from raiding Britain. Only the strength of the

Roman army kept the province safe. But from the end of the second century on-

wards the central government of the Empire at Rome fell into increasing dis-

order, and in 367 the Picts, Scots and Saxons made simultaneous attacks on

Britain from the north, west and east. The waves of people who moved into

Britain between the fourth and sixth centuries were Angles, Saxons and Jutes.

Gradually they changed Angle to English and called the land they had conquered

England.

The British were killed, enslaved, or driven into the highlands of Wales

and the north-west, where their Christian religion and their Celtic language

survived. Over this same long period the newcomers gradually united into large

kingdoms, such as Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex. Many English counties today

bear the names of early kingdoms: Kent, Sussex and Essex are three examples;

while Norfolk and Suffolk took their names from the North Folk and the South

Folk of the kingdom of East Anglia. The Germanic influence on the place-names

may be traced today in such words as Birmingham, Nottingham, Southampton in

which "ham" means "farm" and "ton" stands for "settlement".

The Saxons created institutions which made the English state strong enough

for the next 500 years. One of these institutions was the King's Council,

called the Witan. The Witan probably grew out of informal groups of senior

warriors and churchmen .to whom kings had turned for advice or support on

difficult matters. By the tenth century the Witan was a formal body, issuing

laws and charters. It was not at all democratic, and the king could decide to

ignore the Witan's advice. But he knew that it might be dangerous to do so,

for the Witan's authority was based on its right to choose kings, and to agree

the use of the king's laws. Without its support the king's own authority was

in danger. The Witan established a system which remained an important part of

the king's method of government. Even today, the king or queen has a Privy

Council, a group of advisers on the affairs of the state.

The Saxons divided the land into new administrative areas, based on shires,

or counties. These shires, established by the end of the tenth century, remain-

ed almost exactly the same for a thousand years. "Shire" is the Saxon word,

"county" the Norman one, but both are still used. Over each shire was appoint-

- 17 -

ed a "shire reeve", the king's local administrator. In time his name became

shortened to "sheriff".

In the last hundred years of Roman government Christianity became firmly

ivitablished across Britain, both in Roman-controlled areas and beyond.

However, the Anglo-Saxons belonged to an older Germanic religion, and they

drove the Celts into the west and north. In the Celtic areas Christianity

continued to spread, bringing paganism to an end. In 597 Pope Gregory the

Great sent a monk, Augustine, to re-establish Christianity in England. Kent

was converted without difficulty, because it had frequent contacts with Chris-

tian France, and Canterbury, the Kentish capital became the seat of the arch-

bishop who is the spiritual leader of the modern English Church, but outside

Kent conversion was slow.

In the eighth century England emerged from confusion and ignorance of the

English conquest and seemed fAirly embarked on the long road back Fo a secure

life. But this prospect of better life was shattered at the end of the eighth

century by the beginning of a period of savage raiding and invasion of the

vikings. "Vikings" is the name given to the Scandinavians who came from modern

Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the very word meaning "sea-rovers" or "pirates".

Flic most important reason for the Viking Age of raiding and settlement was

over-population. The vikings, who most seriously affected England were the

Brines, who raided the eastern and southern coasts from 789 to 865. As the

English had done five centuries earlier, they went up the rivers in their long

fihips. When they reached the point where the ships would no longer float, they

Innncd a fortified camp, seized horses, and rode far and wide over the country

rereading fire and slaughter. The once fierce English had in their turn become

prncc-loving farmers, and were no match for these strong warriors. In ten

yours (865-75) all English kingdoms, with the exception of Wessex, passed into

Ilio possession of the Danes. Alfred, King of Wessex, was a wise statesman who

iiiiiiinged to outwit and later on to defeat the Danes, so that in 878 England was

divided between Alfred and the Danes by a line roughly from London to Chester.

I hr. Dnnes in England became established in their half of the country as land-

iiwners and energetic colonists among the English. The period from the death of

Allred in 899 to the death of his grandson Edgar in 975 has been called the

Bolden Age of Anglo-Saxon England.

there were several waves of the vikings invasions to Britain in subsequent

yiiiirn. Ilieir attacks so weakened the large Pictish kingdom in northern Scot-

I mil Hint in 843 Kenneth MacAlpine, ruler of Scots, was able to conquer the

18 -

Picts and become the first king of Scotland.

The Norman Conquest

Feudalism, England of Doomsday Book. Magna Carta and the decline of

feudalism. The beginnings of Parliament. When Edward the Confessor became

king of England in 1042 he was thirty-seven years old and had lived most of

his life in Normandy, because his mother was a daughter of the Duke of Norman-

dy. He was, therefore, more French than English in language, manners and

tastes, and when he became king there began a close association between Eng-

land and Normandy. Edward died in 1066 without an obvious heir. The question

of who should follow him as king was one of the most important in English his-

tory. Edward had brought many Normans to his English court from France, who

were not liked by the more powerful Saxon nobles, that is why the Witan chose

Harold from Wessex to be the next king of England. Harold's right to the Eng-

lish throne was challenged by Duke William of Normandy who in 1066 landed near

the town of Hastings. Harold was defeated and killed in the battle. William

very soon reached London and was crowned king of England in Westminster Abbey

on Christmas Day 1066.

The only resistance to William after this was a series of risings in dif-

ferent parts of the country. He made no attempts to conquer Wales and Scotland.

Instead he established exceptionally strong military earldoms along the fron-

tiers of both countries. In 1072 William in person led an expedition into

Scotland and forced the king to swear allegiance to him, but there were many

border wars in the next two centuries. In Wales the rugged mountains made the

north of the country impregnable, but in the less mountainous south there was

constantrfighting with varying success and much castle-building by the Normans.

As a result of the Norman conquest some 200 Norman nobles and about 4,000

knights took over the leadership of the English people from the English nobles.

This was the last time in English history that foreigners entered the island

from overseas and imposed themselves on the previous inhabitants by force.

Immediately after his coronation William seized the land of all, who had

fought against him at Hastings, and gave it to his nobles. Thereafter he

confiscated the land of anyone who rebelled against him. Thus within a few

years the English landowning class had been almost entirely replaced by a

Norman landowning class of earls and barons, some two hundred all in all. Most

of these tenants-in-chief (that is, men holding their land directly from the

king) owned many estates, called manors, scattered all over England. In return

for his land each tenant-in-chief had to swear a most solemn oath to the king,

promising his personal loyalty and performance of all the feudal services due

- 19 -

to his land. The most important of these services was to supply a number of

rirmoured knights when the king called for them. In addition to military

ocrvice each feudal had to attend the lord's court to advise him and help him

administer justice. On three very expensive occasions the tenant had to make

money contributions: the knighting of the lord's eldest son, the marriage of

his eldest daughter, and the payment of his ransom if he was taken prisoner in

battle.

When his re-organization of England was finished, William decided to carry

out a complete investigation of the ownership and value of all the land in

England. In the spring of 1086 he sent commissioners to visit every shire

court and make the recordings of all possessions of his subjects. After

William's death in 1087 this vast mass of information was digested into two

great volumes, known as Doomsday Book, and for generations this book remained

in daily use as a basis for taxation and for proving who owned the land.

The twelfth century saw many changes in the system of law and government.

I he two kings who did most to make the ways of government simpler and more

effective were Henry I and Henry II. The king governed the country with the

advice and help of his Council. He had a Great Council, consisting of all

tenants-in-chief, which met only occasionally to advise and take decisions on

the most important questions. He also had a small Council, which was always

with him as he moved about the country. This Council consisted of a few of the

most .important nobles and bishops, and also the king's ministers.

The improvements in the machinery and methods of government greatly

increased the power of Henry II over his subjects, and his son, King John,

faced great problems in dealing with the barons and their supporters. In 1215

the barons forced King John to accept a document, called in Latin Magna Carta,

which described in detail all his breaches of the law, and recorded his

promise to govern in future in accordance with the law or with the advice and

consent of his Great Council. In fact Magna Carta gave no real freedom to the

majority of people in England. The nobles who wrote it and forced King John to

sign it had no such thing in mind. They had one main aim: to make sure John

did not go beyond his rights as feudal lord. Feudalism began to weaken, but it

took another hundred years before it disappeared completely, and Magna Carta

was one of the greatest landmarks in the development of the English constitu-

tion.

John's son Henry III was the first king of England since the Norman

Conquest to be free from the distraction of ruling extensive lands in France.

But he pursued an expensive and unsuccessful foreign policy, trying to recover

- 20 -

the French dominions lost by his father, which eventually brought him into

collision with the barons under the leadership of Simon de Monfort. At a

meeting of the Great Council in 1258 Henry III had to agree to the Provisions

of Oxford: he would give up his foreign ventures and consult the Great Council

three times a year. It was at this time that meetings of the Great Council

began to be called Parliaments, that is meetings for discussions. Henry’s

agreement to the Provisions of Oxford was published in English — the first

important document to be issued by the government in English since the days of

William the Conqueror. This shows the extent to which both sides in the

dispute relied on the support of the country gentry and townspeople.

Edward I brought together the first real parliament. Simon de Monfort's

council had been called a parliament, but it included only nobles. It had been

able to make laws and political decisions, but the lords were less able to

provide the king with money. Edward I created a "representative institution"

which could provide the money he needed. This institution became the House of

Commons. Unlike the House of Lords it contained a mixture of gentry (knights

and other wealthy freemen from the shires) and merchants from the towns. These

were two broad classes of people who produced and controlled England's wealth.

In 1275 Edward I commanded each shire and each town to send two representa-

tives to his parliament. These "commoners" would have stayed away if they

could, to avoid giving Edward money, but few dared risk Edward's anger. They

became unwilling representatives of their local community. This parliament

came by tradition to be regarded as the model of all future parliaments.

The First "United Kingdom"

Since England, Wales and Scotland all lie within a comparatively small

island, it was certain that, sooner or later, the ruler of the strongest of

these three states would conquer the other two and make the island a single

united kingdom. Greater area, population, and natural resources made England

the strongest of the three states. The conquest of Wales was completed by the

end of the thirteenth century because it lay nearer than Scotland to the main

area of Anglo-Norman wealth and power. Scotland, on the other hand, success-

fully defended its independence for three hundred years longer than Wales.

The first Welsh ruler to make himself master of the whole Wales was

Llewelyn the Great (1194-1240). His grandson, Llewelyn II (1247-82), enjoyed

for a time even greater and wider power in Wales, but he supported Simon de

Monfort in the civil war against Henry III and soon after Simon's defeat

Llewelyn had to make peace with Henry and he had to recognize the king of

- 21

England as his overlord. When Edward I succeeded his father as king of

England in 1272, Llewelyn should have renewed his homage to the new king, but

his refusal to do so was the beginning of his downfall. Edward invaded Wales

in 1276 and made Llewelyn surrender. He was allowed to keep the hereditary

title of Prince of Wales, but his authority was restricted to a small area in

Wales.

In 1282 Llewelyn’s brother David started a rebellion, but Edward once

again called together his army and after some months of fighting Llewelyn was

killed in battle, and David was captured and executed as a traitor. By the

Statute of Wales, issued in 1284, the land and people became directly subject

to the king of England. One month later a son was born to Edward I at

Carnarvon Castle. In 1301 the title Prince of Wales was revived for this young

man. Since then the eldest son of the king of England has always had the title

Prince of Wales conferred on him. King Edward I greatly extended his system

of castles, adding a ring of castles around Welsh stronghold of Snowdonia, at

Conway, Carnarvon and Harlech (ill. 42-44). These were the largest and

strongest castles which the English had ever built.

Scotland had become a centralized feudal kingdom in the middle of the

twelfth century. But when in 1286 Alexander III died suddenly without a

direct heir there were two possible successors to his throne. To avoid civil

war the leading men of Scotland invited Edward I of England to decide between

these two claims. Edward gave judgement in favour of John Balliol, who paid

homage to Edward and was crowned King John of Scotland. But soon Edward began

to make effective use of his clearly defined overlordship over Scotland, but

the Scots resented their loss of independence and resisted. Open revolt broke

out in 1295 and in the spring of 1296 Edward invaded Scotland and defeated the

Scots. Thus Edward reduced Scotland to much the same condition as Wales after

the rebellion of 1282. The kingdom of Scotland had been abolished and the land

had been incorporated into the dominions of the king of England. But Scottish

strength had not been broken by Edward’s triumphant tour. Armed resistance to

English rule continued under the leadership of William Wallace, who inflicted

a major defeat on the English at Stirling Bridge in 1297. In 1298 Edward took

revenge for Stirling at Falkirk, but he was distracted from Scotland because

of the war with France. He took Stirling Castle in 1304 after a long siege and

Wallace was captured and executed in London. Edward tried to make Scotland a

part of England, as he had done with Wales. Some Scottish nobles accepted him,

but the people refused to be ruled by the English king. Scottish nationalism

was born on the day Wallace died.

- 22 -

The argument between the two countries continued later on between the son

of Edward I and Robert Bruce, crowned King Robert of Scotland. In 1314 Bruce

defeated the English army at Bannockburn and Scotland became a strong indepen-

dent kingdom, bitterly hostile to England. An alliance grew between Scotland

and France, known as "the Old Alliance", with the result that on the many

occasions when England was at war with France, it had to fight on two fronts.

When the Union of Crowns finally came in 1603, it was the result not of

conquest, but of the accident that James VI of Scotland was the heir of the

childless Elizabeth I of England.

The Century of War, Plague and Disorder

The grandson of Edward I, Edward III (1327-77), was another of England's

great warrior kings. The chief event of his reign was the beginning of a long

and dramatic struggle for mastery between the kings of England and France

which lasted, with intervals of peace, for more than one hundred years (1337-

1453), and had a profound effect on the history of both countries.

Edward III and Philip VI of France drifted into the war without any notion

that they were starting such a long and destructive struggle. Edward feared

French encroachments on the English possessions in France — Gascony, resented

the French Alliance with Scotland, desired to protect Flanders, which bought

most of the English wool every year, from the French aggression, and he also

hoped to regain all the possessions in France which had been lost by King

John. Philip wanted to drive • the English out of France altogether and to

extend his authority to the rich county of Flanders. It was only after war had

broken out that Edward advanced a claim to the French crown, which, soundly

based in law, was utterly unacceptable tn the people of France.

The warfare was interrupted by Black Death — the bubonic plague in 1348,

which was the greatest catastrophe in the history of England. In spite of this

disaster the war was renewed in 1355 by Edward, Prince of Wales, known from

the colour of his armour as the Black Prince. He lived only for war; his chief

interest in war seems to have been slaughter and destruction. He defeated the

French in 1360 and both sides had signed a truce, which was violated by both

sides many times in the years to come.

Peace lasted until 1415 and this long interval in the Hundred Years' War

was occupied by the reigns of Richard II and Henry IV. It was the time of

great social and political unrest, caused by the destructive influence of the

war on all aspects of life in England’. In 1381 the peasants rose in revolt

against their lords and government. Led by Wat Tyler, they entered London and

- 23 -

(or two days controlled the capital. They released the prisoners from prison

mid murdered all the lawyers they could catch. With great courage the young

king met the rebels in an open space. Tyler spoke for the rebels. An alterca-

I ion followed, in which he was killed. Just as the great mass of the rebels

wnu about to overwhelm the king and his small party, Richard promised to grant

nil their demands. They accepted and dispersed to their homes. The rebellion

was over. The government then ignored the king’s promises and took a terrible

revenge on the peasants.

During the reigns of Henry IV and Henry V the war with France continued

and France inflicted heavy losses until a leader of miraculous powers appeared

In France, re-united the nobles, and gave confidence to the people. This was

Joan of Arc, a poor illiterate peasant girl who was inspired by the belief

(hat she was sent by God to save France from the English. In only just over

two years, from her capture of Orleans in 1429 to her burning as a witch in

1431, her work was finished. Although it took the French another twenty—two

years to recover their land from the English, they never lost the spirit Joan

liad given them. When the war at last ended in 1453 the English held only

Calais.

I be England of Chaucer

In the middle of the fourteenth century the clergy, lawyers and scholars

проке Latin; people in aristocratic society still spoke French; but everybody

проке English. In 1362 Edward III ordered that English should be spoken in

Parliament and it was a major step in the development of English as the

national language. In the year when Edward issued his order, Geoffrey Chaucer,

the first person to use the English language for a masterpiece of literature,

wns twenty-two years old. He was writing poetry in English all through his

life, and his masterpiece, "The Canterbury Tales”, was written about 1386-

9(1. The popularity of his book did much to establish the kind of English

прокоп in London and the East Midlands as standard English of all educated men.

In the fourteenth century England was the chief wool-producing country» in

I иrope, and the great cloth industry of Flanders depended on English wool.

(*«»nrse cloth for wear by the ordinary people had always been woven in England,

but the upper classes wore fine cloth imported from abroad. Towns were growing

In number, size and importance with the development of industry and trade, hut

I own life was not completely cut off from the country life as it is in the

modern industrial community. There were a few large towns: London had about

4U,000 inhabitants, York and Bristol about 10,000 each, but over the country

- 24 -

as a whole 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants represented a fair-sized town.

Trade and industry within each town were organized by the Merchant and

Craft Guilds. The Merchant Guild supported the citizens who traded outside the

town in competition with merchants from other towns. There was a Craft Guild

for each craft, as for example, weaving, carpeting, etc., which controlled the

quality of the products. The guilds also produced miracle and morality plays

during the.great festivals of the Church, such as Christmas and Easter. These

plays were among the devices used by the medieval Church to keep the people,

who could not read, constantly reminded of the great stories of their religion

— painted glass windows and the paintings with which the walls of churches

were covered, were other devices.

Great wealth also found expression in the building of fine houses and

magnificent churches, and the foundation of schools and colleges — as, for

example, Eton College near Windsor and King’s College at Cambridge University,

founded by Henry VI, or New College at Oxford University. But in 1455, only

two years after the end of the Hundred Years’ War, a series of civil wars

began between the great nobles for the control of the government.

The Wars of the Roses

Henry VI, who had become king as a baby, was a mentally ill king and hated

the warlike nobles. There were not more than sixty noble families controlling

England at that time. Because. of the fact that England had lost the war with

France and was ruled by a mentally ill king, it was perhaps natural that the

nobles began to ask questions about who should be ruling the country. Eventual-

ly by 1460 the nobility were divided between those who remained loyal to Henry,

the "Lancastrians”, and those who supported the duke of York, the "Yorkists".

According to tradition the Lancastrians took a red rose as their emblem and

the supporters of the duke of York took a white rose, which gave the name to

these wars as the Wars of the Roses.

In 1461 Duke of York defeated the Lancastrians and was crowned king as

Edward IV. He began the horrible practice, which was continued by both sides

for the rest of the wars, of executing noble captives after each victory. As a

result, few of the old feudal nobility survived the Wars of the Roses-— those

who were not killed in the battles were executed qfterwards, and most of the

old noble families became extinct.

When Edward IV died in 1483 his brother Richard took the Crown and became

King Richard III. He was not popular as king and both Lancastrians and

Yorkists disliked him. In 1485 a challenger from France with a very distant

- 25 -

clriim to royal blood landed in England to claim the throne. His name was Henry

ludor. Many discontented lords on both sides joined him and the battle of

Booworth quickly ended in defeat and death of Richard III. Eventually, in 1485

the House of York gave place to the House of Tudor, and the Wars of the Roses

were over. England had at last found a ruler sufficiently strong, clever and

ublc to solve her problems. The violence and uncertainty which dominated

I ngland for over a generation before 1485 were hated by all except the small

group who profited from them and the people were willing to welcome and

support any king strong enough to restore and maintain good government and

respect for the law. This was the foundation of the strength and success

Of Henry VII.

Ihe New Monarchy and the New Age

The Tudors, the Reformation, the Protestant — Catholic Struggle, the New

I oreiqn Policy. Many revolutionary changes were taking place in England under

Henry VII, but even more far-reaching changes were taking place in Europe and

til footing the outside world. They were the invention of printing and the

Renaissance, and their impact on England is associated with William Caxton and

I rnsmus.

Caxton was a prosperous merchant who lived for over thirty years in

I landers where he learned the recently invented art of printing. In 1476 he

returned to England and set up his press in Westminster. During his life he

printed nearly a hundred books and thus completed Chaucer’s work of establish-

ing the kind of English spoken in London and the East Midlands as the standard

I nglish of all educated men.

In the early years of the sixteenth century the Dutchman Erasmus was the

input distinguished scholar in Europe. Through visits to England, where he was

Гос a time Professor of Divinity and Greek at Cambridge University, Erasmus

did more than any other man to extend the full fruits of Renaissance to

Inqland. One important result was a thorough reform of the methods and subject

unit ter of education.

The century of Tudor rule (1485-1603) is often thought of as a most

glorious period in English history. Henry VII built the foundations of a

wnnlthy state and a powerful monarchy. His son, Henry VIII, kept a magnificent

rnurt, and made the Church of England truly English by breaking away from the

R(»mun Catholic Church. Finally, his daughter Elizabeth brought glory to the

im’W state by defeating in 1588 the powerful navy of Spain, the greatest

I urnpean power of the time. During the Tudor age England experienced one of

- 26 -

the greatest artistic periods in its history. There is, however, a less

glorious view of the Tudor century. Henry VIII wasted the wealth saved by his

father. Elizabeth weakened the quality-of government by selling official posts.

She did this to avoid asking Parliament for money.

Henry VIII was always looking for new sources of money. His father had

become powerful by taking over the nobles’ land, but the lands owned by the

Church and the monasteries had not been touched. The Church was a huge

landowner, and the monasteries were no longer important to economic and social

growth in the way they had been two hundred years earlier. Henry VIII disliked

the power of the Church in England because, since it was an international

organisation, he could not completely control it. He was not the only European

king with a wish to ’’centralise’’ state authority. But Henry VIII had another

reason for standing up to the authority of the Church.

It was the failure of Catherine of Aragon to provide a male heir to the

throne which led to a great quarrel between Henry VIII and the Pope. By 1527

the only living child of Henry VIII was a daughter, Mary. He feared the

outbreak of a civil war if he died without a son to succeed him, so in 1527 he

instructed Cardinal Wolsey to get the Pope to dissolve his marriage to

Catherine, in order that he might marry Anne Boleyn and have a son. But the

Pope was not in a position to do that, so in 1529 Wolsey fell from his power,

and Henry prepared to use the English hatred of the wealthy clergy to force

the Pope to do what he wanted. Slowly Henry VIII put pressure on the Pope and

after several refusals of the Pope to give way Henry in 1533 made himself head

of the Church of England in place of the Pope. The new Archbishop of Canter-

bury, Thomas Cranmer, declared that Henry had never been lawfully married to

Catherine and that his four-month secret marriage to Anne was legal.

In this way the Church of England lost its power to the king and Parlia-

ment, but its immense wealth had as yet been hardly touched. So between 1536

and 1539 his new minister Thomas Cromwell, with the support of the Parliament,

dissolved the monasteries and transferred all their property to the king. The

monks and nuns who co-operated, were found jobs in the Church or were

pensioned off; the few who resisted, were hanged. The king's need for

money was so great that he could not keep the monastic lands and spend only

the income. He began to sell them to his officials and wealthy merchants.

Henry married in all six wives, but only three children survived his death

in 1547: Mary, born to Catherine of Aragon, Elizabeth, born to Anne Boleyn and

Edward, born to Jane Seymour.

The son of Henry, Edward VI, was only a child when he became king, so the

- 27 -

country was ruled by a council. All the members of this council were from the

new nobility created by the Tudors. They were keen protestant reformers

because they had benefited from the sale of monastery lands. All the new land-

owners knew that they could only be sure of keeping their lands if they made

I nqland truly Protestant. In 1552 a new prayer book was introduced to make

rmre that all churches followed the new Protestant religion, but the people

did not like the changes in belief, and in some places there was trouble.

When Elizabeth I became queen in 1558, she wanted to find a peaceful

answer to the problems of the English Reformation. She wanted to bring

together again those parts of English society which were in religious disagree-

incnt. The struggle between Catholics and Protestants continued to endanger

llizabeth's position for the next thirty years. Both France and Spain were

Catholic, and Elizabeth and her advisers wanted to avoid open quarrels with

both of them. There was also a danger from those Catholic nobles who wished to

remove Elizabeth I and replace her with the queen of Scotland, who was

Cntholic.

The story of the relationship of Elizabeth and Mary Queen of Scots (Mary

Slunrt) is a tragic history of relationship of two queens, which inspired many

writers of the past and present to give their own vision of a personality

during the most crucial period of the history of England and Scotland. After

an unsuccessful marriage in France Mary had returned to Scotland and married

hcr cousin, who was killed in circumstances which made it almost certain that

ho had been murdered. Mary's ardent Roman Catholicism had already made her

unpopular with her Protestant subjects. She had to abdicate in favour of her

Infant son James and fled to England in 1568. Her cousin Elizabeth I could

neither send her back to Scotland, because the Scots were determined to kill

her, nor let her go free in England, because to all Roman Catholics she was

tho rightful queen of England. 5o she remained a prisoner for nineteen years,

until the Catholic plots to make her queen instead of Elizabeth became so

ihiiujcrous that she was executed in 1587. By that time most English people

believed that to be a Catholic was to be an enemy of England. This hatred of

everything Catholic became an important political force.

One of Elizabeth's most remarkable achievements in the first half of her

reign was the restoration of the country's finances to a sound condition for

I he first time over thirty years. The rapidly increasing prosperity gave many

p-rople more leisure for recreation and more money to spend on pleasure. This

produced an outburst of artistic achievement, particularly in music, poetry

and drama. Elizabethan age is unique, because in it lived and worked a

- 28 -

uniquely great artist — William Shakespeare (ill. 11-12).

The Elizabethan drama was rapidly developed from the miracle and morality

plays of the Middle Ages by a group of writers, of whom only Christopher

Marlowe is still performed. Plays of the new type were first performed in the

colleges of Oxford and Cambridge Universities (ill. 7-10), in the courtyards

of the great mansions. Companies of actors were therefore always on the move.

Permanent theatres were built later, in London, but were regarded with

suspicion by the authorities as places where criticism of the government might

lead to riots. Shakespeare hardly ever wrote directly about current affairs,

for to do so was far too dangerous when many questions of home and foreign

policy were burning issues. Yet we can learn even more about Elizabethan

England from Shakespeare than we can about the fourteenth century from

Chaucer, because whatever the plot, period or country with which Shakespeare

is dealing, it is Elizabethan men and women who move and speak on his stage.

The great geographical discoveries at the end of the fifteenth century

gave control of the new ocean trade routes to Portugal and Spain. England

meanwhile devoted much attention to developing its trade with Europe, but no

spectacular fortunes could be made from such trade. The possibility of vast

profits, though at the price of gigantic risks, tempted a few adventurous

Englishmen to challenge the Spanish monopoly of trade with its colonies. One

of them was Francis Drake, who after three years of wandering in the Pacific

returned home laden with Spanish treasure. Queen Elizabeth recognized his

merits for the country and knighted him.

Although England and Spain did not go to war with each other officially

until 1585, there was a state of undeclared war between them. The long-

expected Spanish attack on England became imminent when, in 1586, Elizabeth

sent an army to help the Dutch rebels. Philip II of Spain became convinced

that he would never defeat the Dutch while England remained unconquered, and

began to prepare a huge fleet, or Armada, for the invasion of England. The

Armada sailed in July 1588 and the Spanish plan was to make contact with their

army in the Netherlands, defeat the English fleet, and convoy the army across

the Channel to invade England. For this purpose the 130 ships of the Armada

carried 18,000 soldiers but only 8,000 sailors, and were commanded by a

general, not an admiral. The English ships were faster, so they were able to

avoid close combat. After two days of fighting the Spanish ships sailed north-

wards in an attempt to get back to Spain by going round Scotland, but a

tremendous westerly gale completed the damage done by the English guns and

fire-ships. Only fifty ships of the Armada got back to Spain.

- 29 -

By the death of Elizabeth I in 1603 England was one of the leading trading

notions in the world, and on the eve of the founding of colonies and expansion

of trade which were to make it the greatest colonial and trading power in

the world.

Пю Stuarts

Parliament against the Crown, Civil War, Restoration. When the son of

Mary Stuart, King James VI of Scotland, succeeded to the throne as James I of

I ngland i,n 1603, he inherited the problems which a much wiser and more adapt-

able man than he might well have failed to solve. The prolonged crisis during

the Tudor period, which resulted from the changes in religion and the threat

of foreign invasion, caused the Tudor rulers to co-operate more fully and more

continuously with Parliament than any previous rulers had done. Three things

produced the head-on collision between James and Parliament which Elizabeth

had with such care and difficulty avoided: James’s constant need for money,

religion and his inability to understand and manage the House of Commons.

In his over-confident way James on his arrival in England so handled

religious affairs that he gave the impression that he favoured Roman Catholi-

cism. This was a bad foundation for his relations with Parliament, where the

Puritans, the party who considered that the Church of England was still too

similar to the Roman Church, were strongly represented • Anxious to rule

over a united, contented and happy people, James suspended the ferocious laws

nqninst Roman Catholics. The result was the fantastic but dangerous Gunpowder

Plot of 1605. The plotters’ intention was to blow up the king and both Houses

of Parliament on the only occasion when they would all be assembled in the

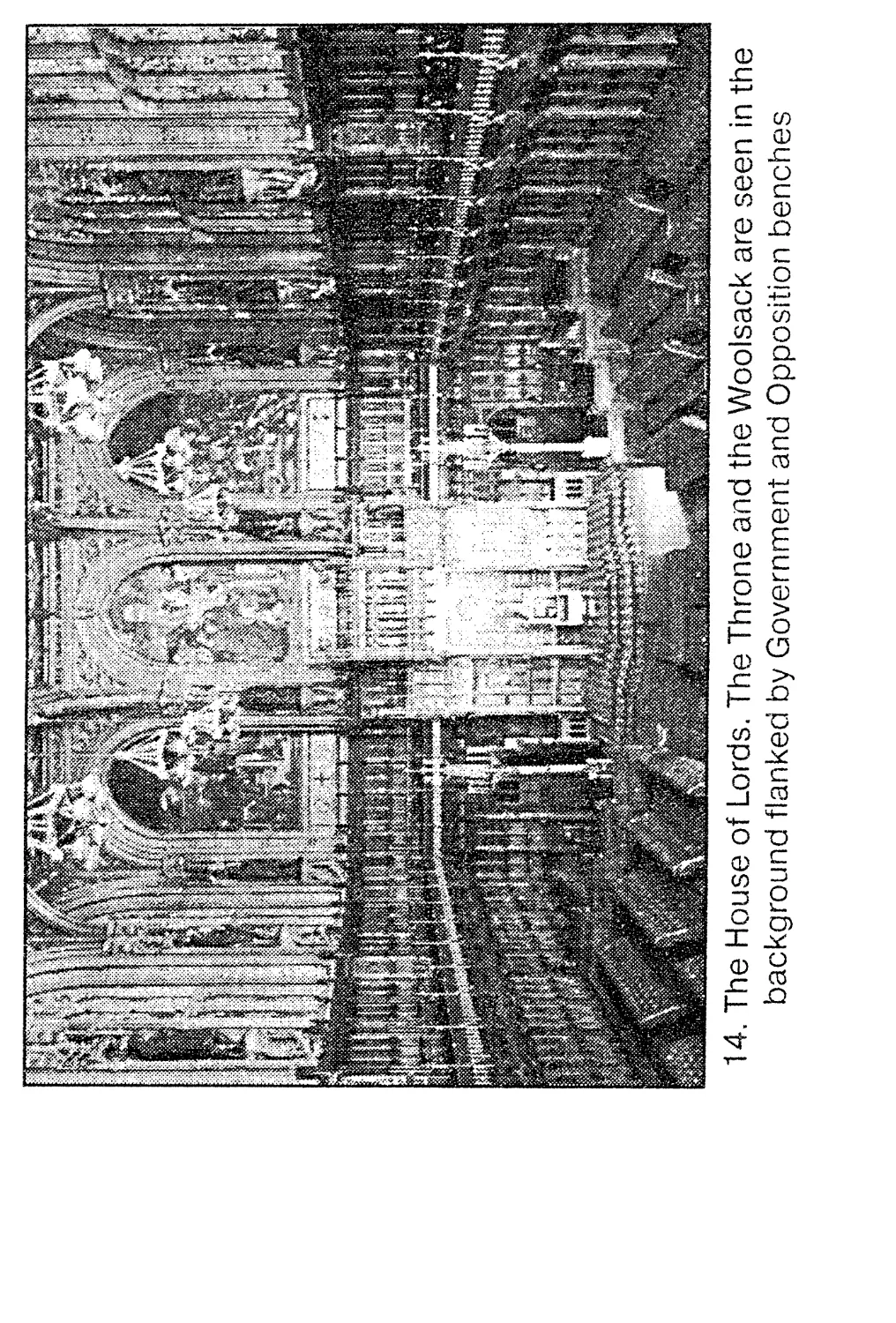

Iknjse of Lords for the State Opening of Parliament on the 5th of November. But

LIkj king’s ministers became aware of the plot and Guy Fawkes was arrested in a

room under the House of Lords. The plot raised popular hatred of Roman Catho-

lics to a frenzy. Bonfires were lighted everywhere to celebrate the escape of

the king and Parliament, and effigies of Guy Fawkes were burned — as they

till 11 are on the 5th of November each year.

Charles I inherited an even more difficult situation than his father. His

iniirriage to Henrietta Maria, the Roman Catholic sister of the king of France,

nnd the knowledge that she had great influence over him gave strength to the

•kunpicion that Charles intended to re-establish the Roman Church in England.

At the beginning of Charles’s reign Parliament deliberately kept him short of

money in order to compel him to call it frequently. There was nothing in the

law of England to compel the king to call Parliament at any fixed intervals,

- 30 -

so for eleven years Charles succeeded in raising enough money without breaking

the law. The first actions of the Long Parliament in 1641 were to secure its

own position and to make illegal the methods by which the king had ruled so

successfully for eleven years without Parliament.

The event which did in fact bring about the formation of a Royalist party

and a Parliamentary party, and made war between them almost unavoidable, was a

rebellion -by the Roman Catholic Irish in October 1641. An army had to be

raised to put down the Irish rebellion, but the Parliament dared not provide

Charles with an army, for fear that he would use it to recover all the

authority which had been taken away from him, and perhaps more. Throughout

English history command of the army had belonged to the king, and it would be

a revolutionary action for Parliament to attempt to transfer command to them-

selves. It was upon this issue of control of the army that the Civil War

broke out.

Charles retired to York in January 1642 and, relying on his supporters to

provide money voluntarily, began to raise an army. Eighty peers and one hund-

red and seventy-five members of the House of Commons joined the king; thirty

peers and three hundred members of the Commons remained in London. The only

clear distinction between the two parties was religion: supporters of the

Church of England and Roman Catholics sided with the king; opponents of the

Church of England sided with the Parliament. But this religious division did

have certain geographical and social consequences. The more sparsely populated

and poor north and west of England in general supported the king; the more

densely populated and rich south and east supported Parliament.

The initiative in the first two campaigns in 1642-3 lay with the king, and

he tried to seize London. Had he succeeded, he would probably have won the

war. During the winter of 1643-4 both sides sought allies. All that Charles

could do was to reach an agreement with the Irish rebels, but these troops

were of poor quality and were of little help to him. Parliament signed the

Covenant with the Scots, by which they secured the help of a powerful Scottish

army in return for their promise (as the Scots understood it, at least) to

make England a Presbyterian country. As a result of this agreement the Anglo-

Scottish army won an overwhelming victory in 1644, and control of northern

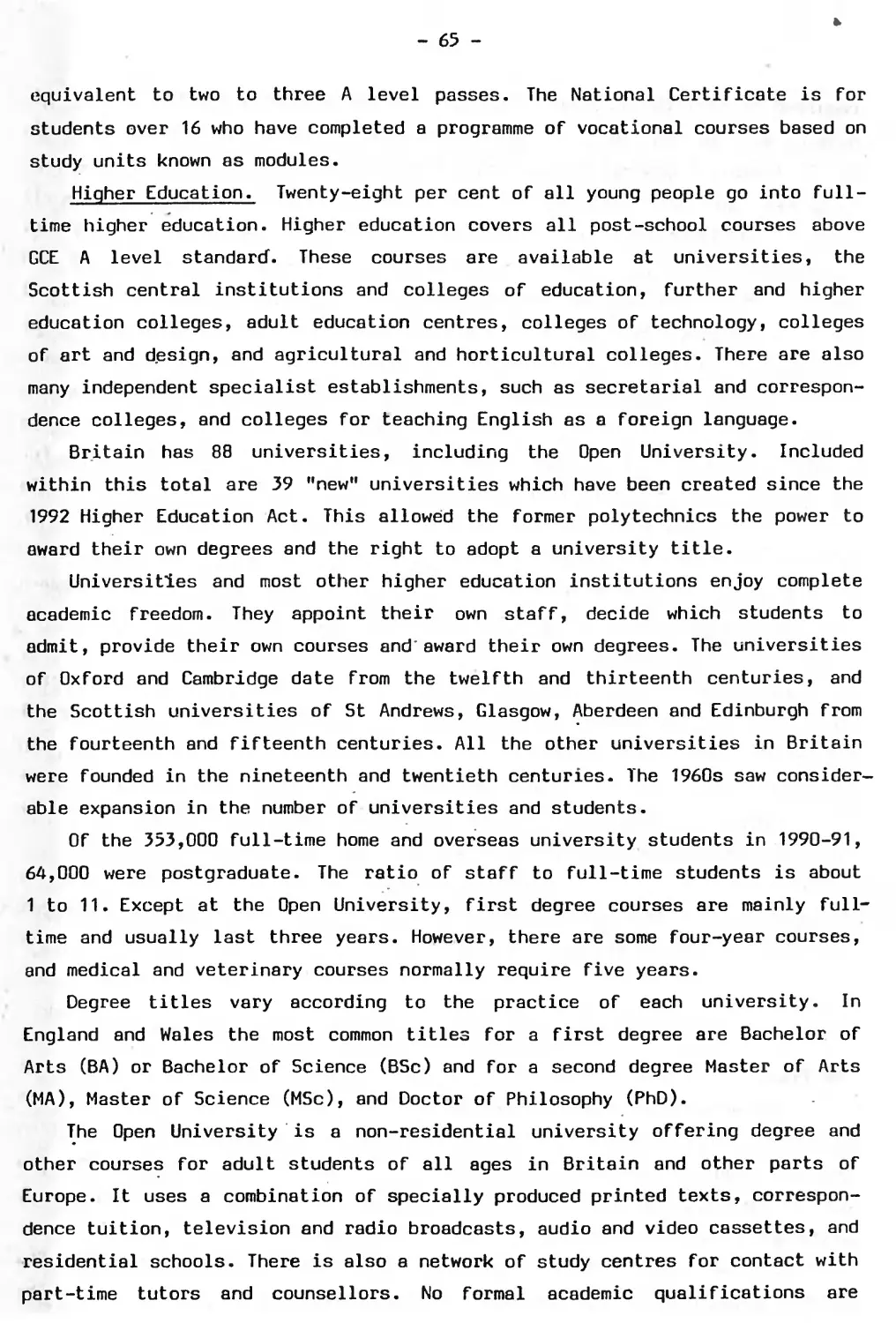

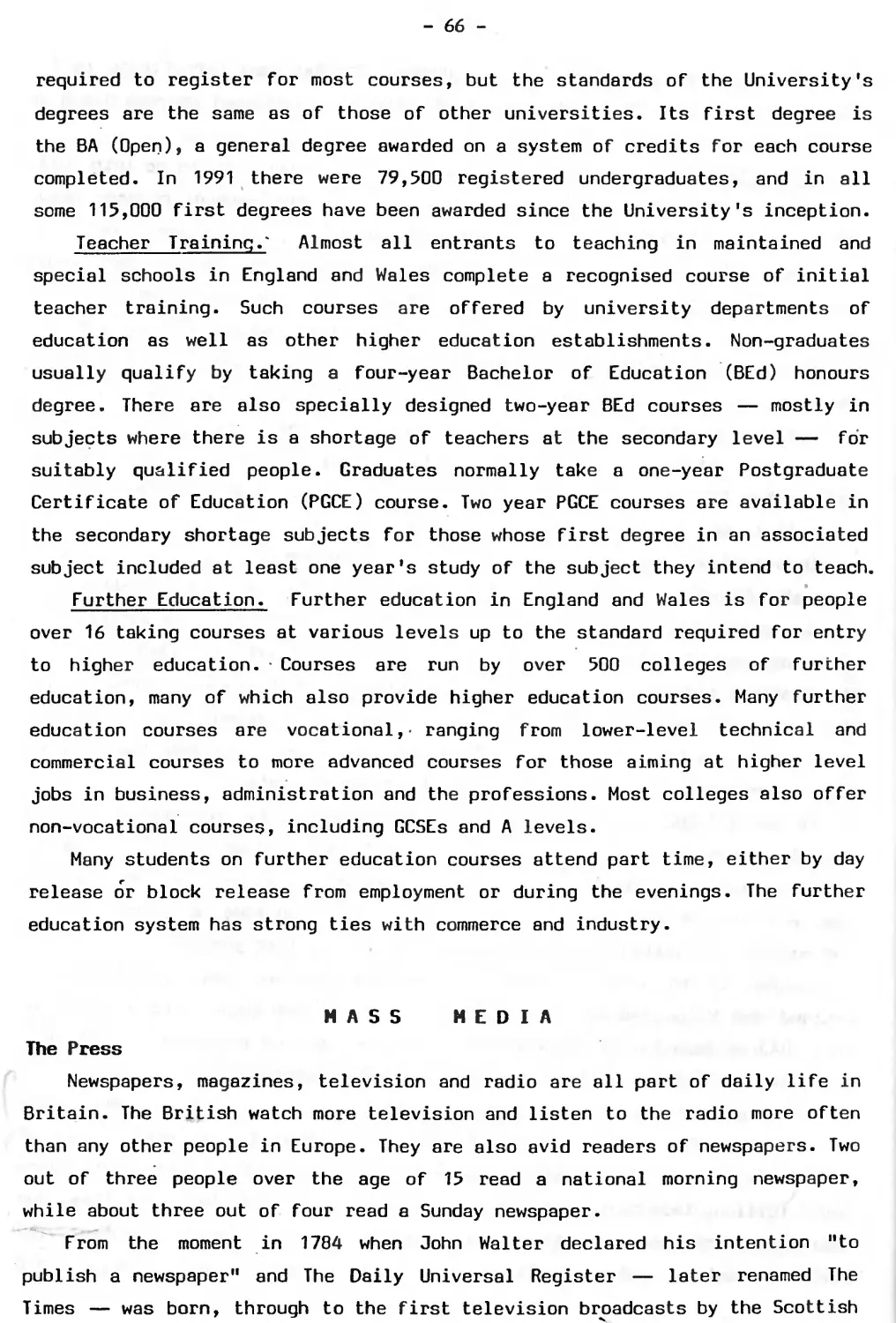

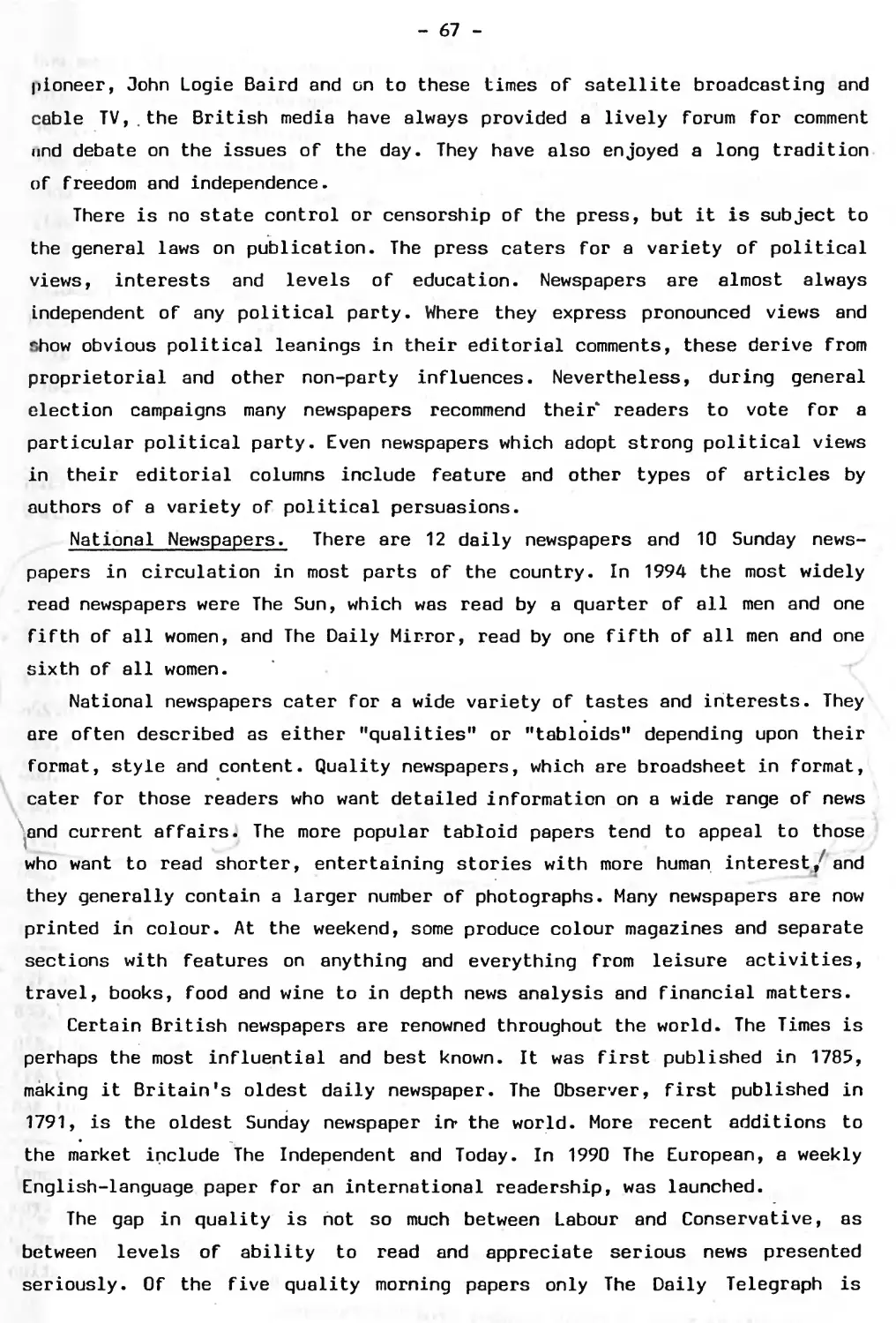

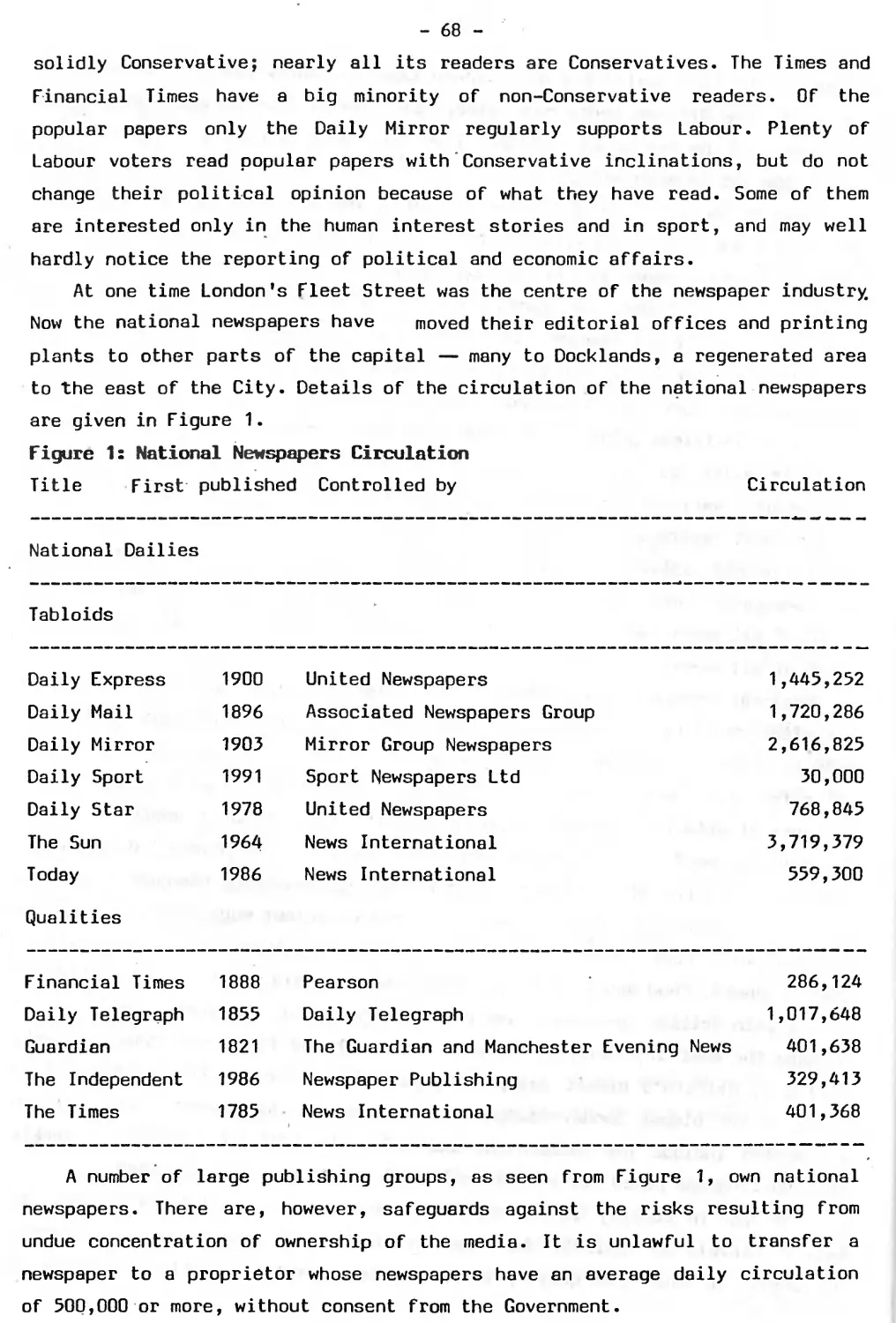

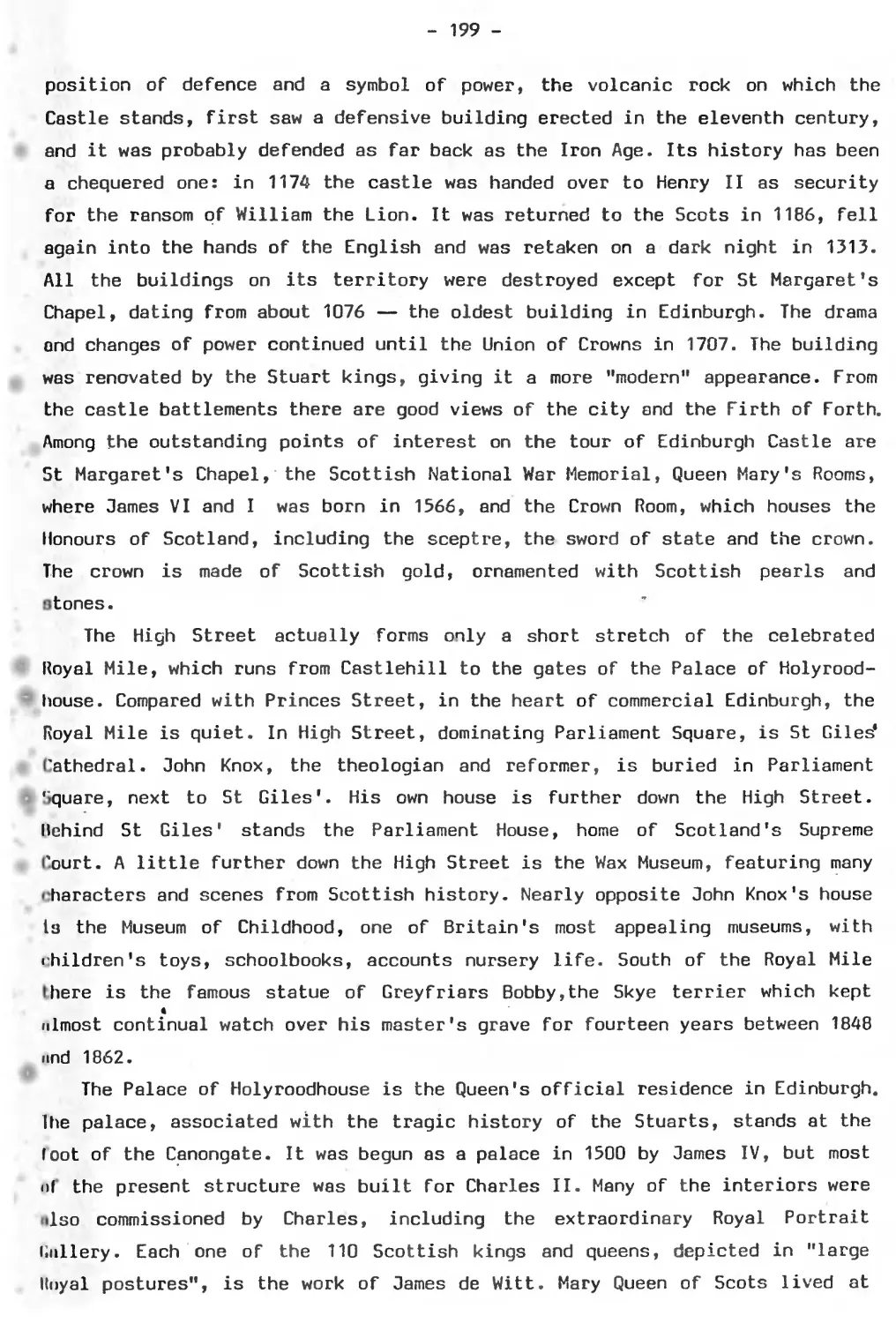

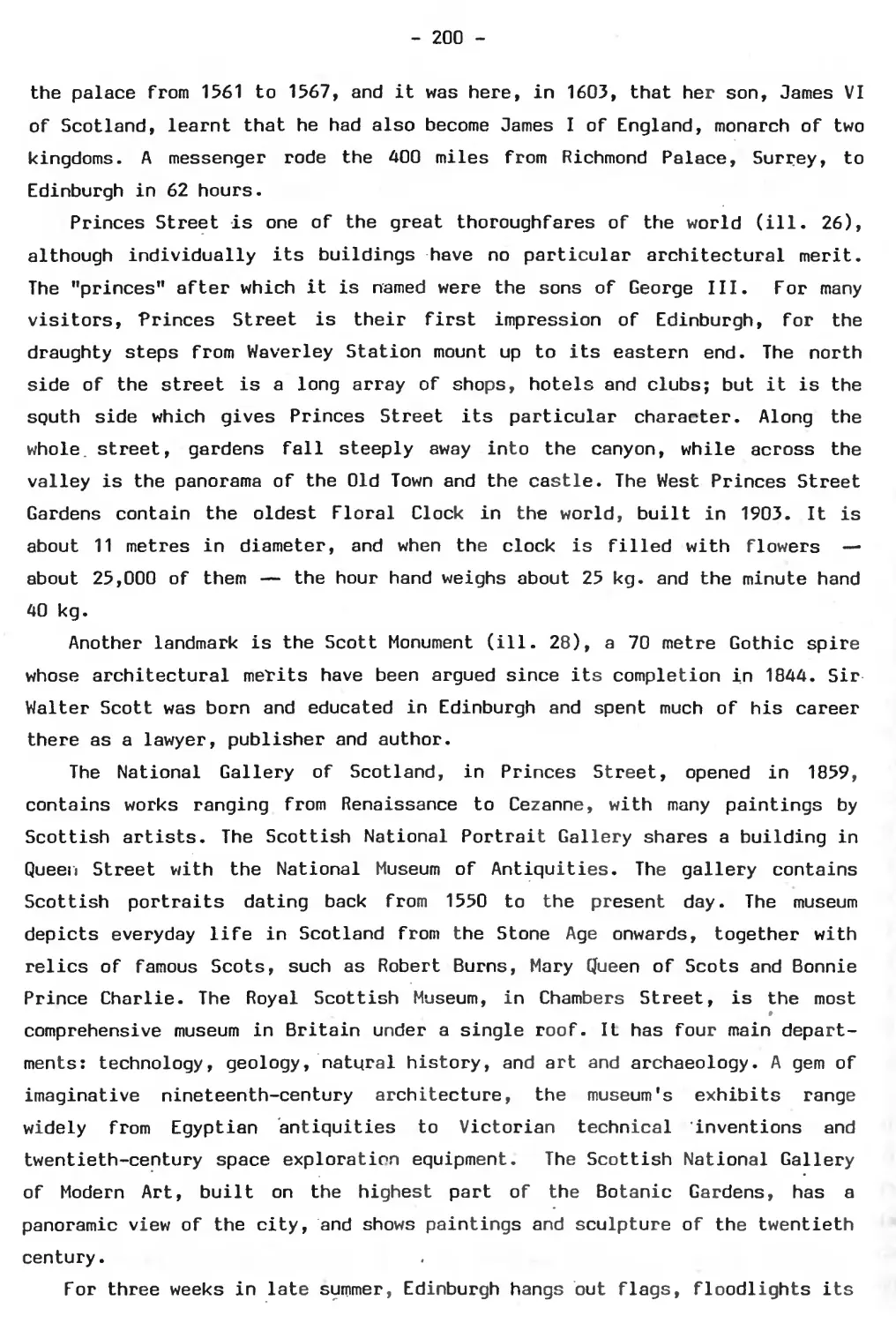

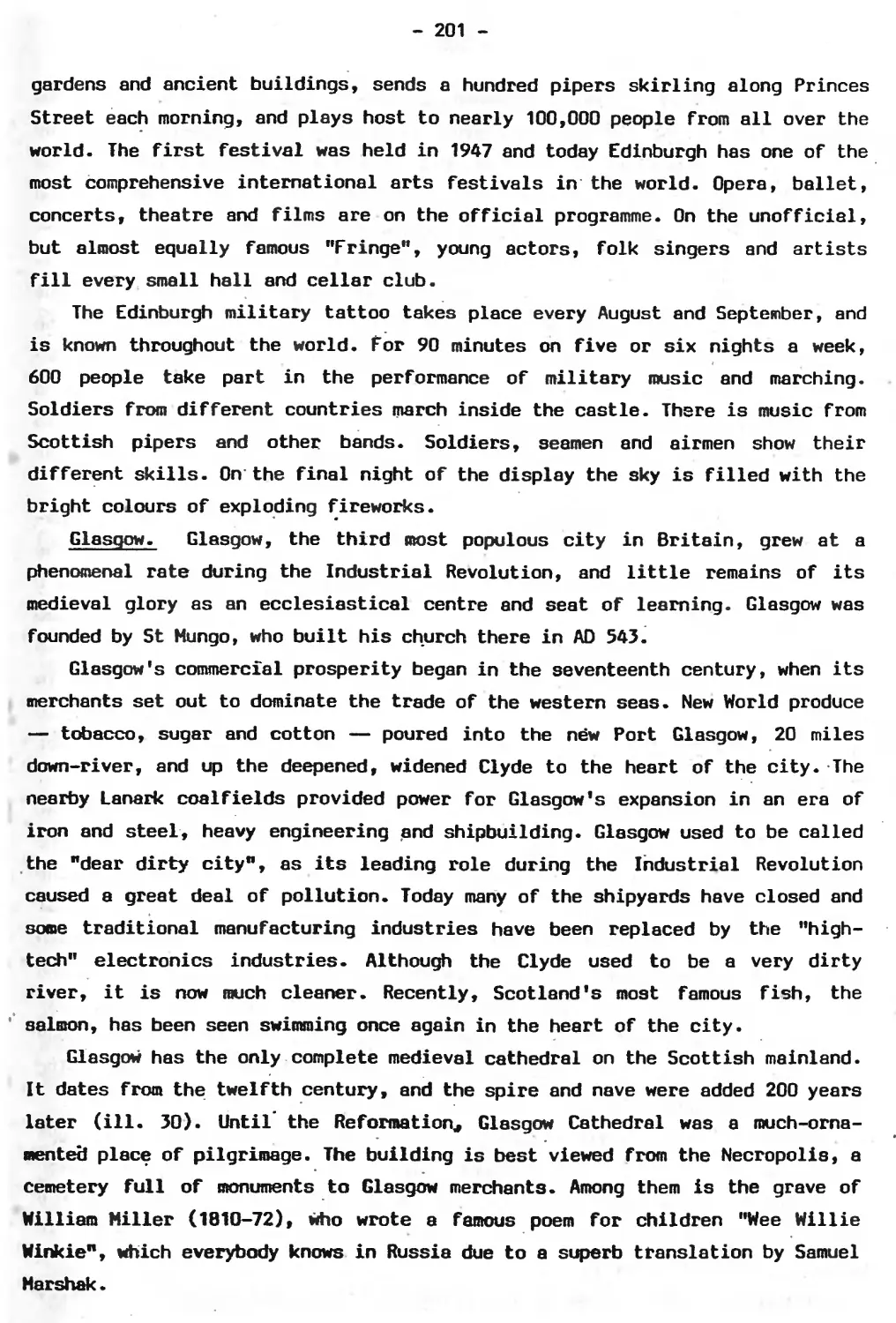

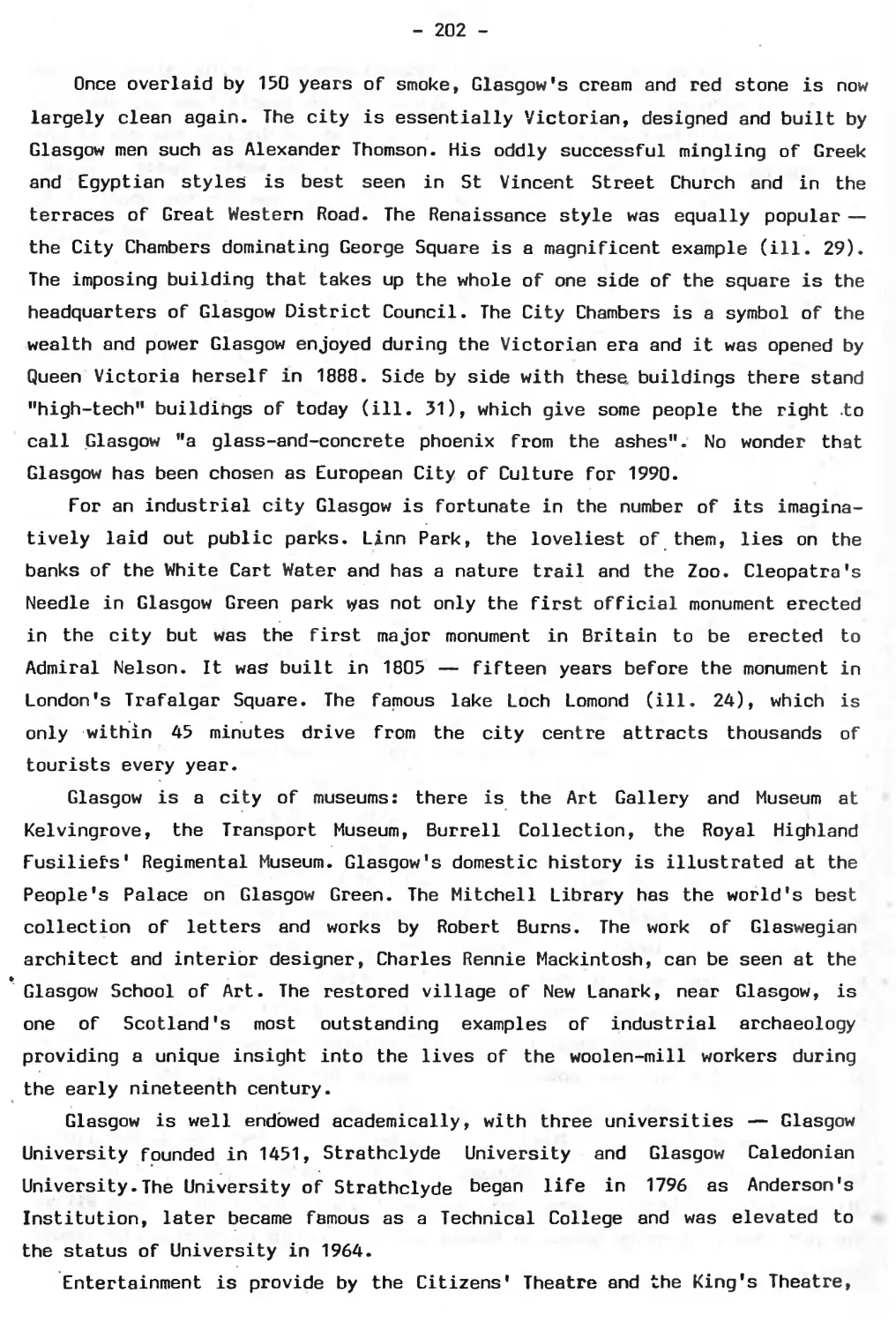

England passed from the king to Parliament. In the summer of 1645 the New