Текст

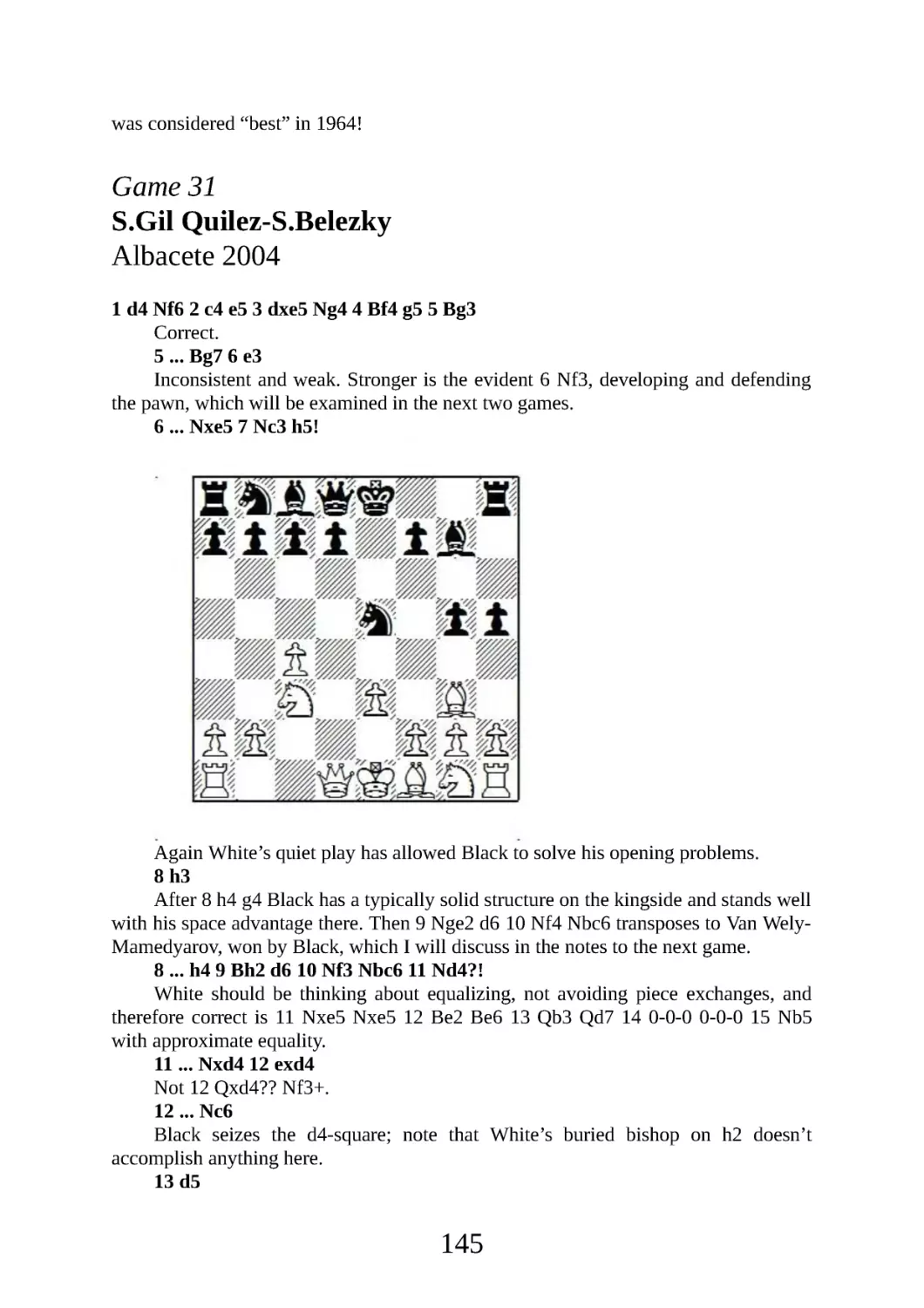

2

First published in 2009 by Gloucester Publishers plc (formerly Everyman Publishers

plc), Northburgh House, 10 Northburgh Street, London EC1V 0AT

Copyright © 2009 Timothy Taylor

The right of Timothy Taylor to be identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

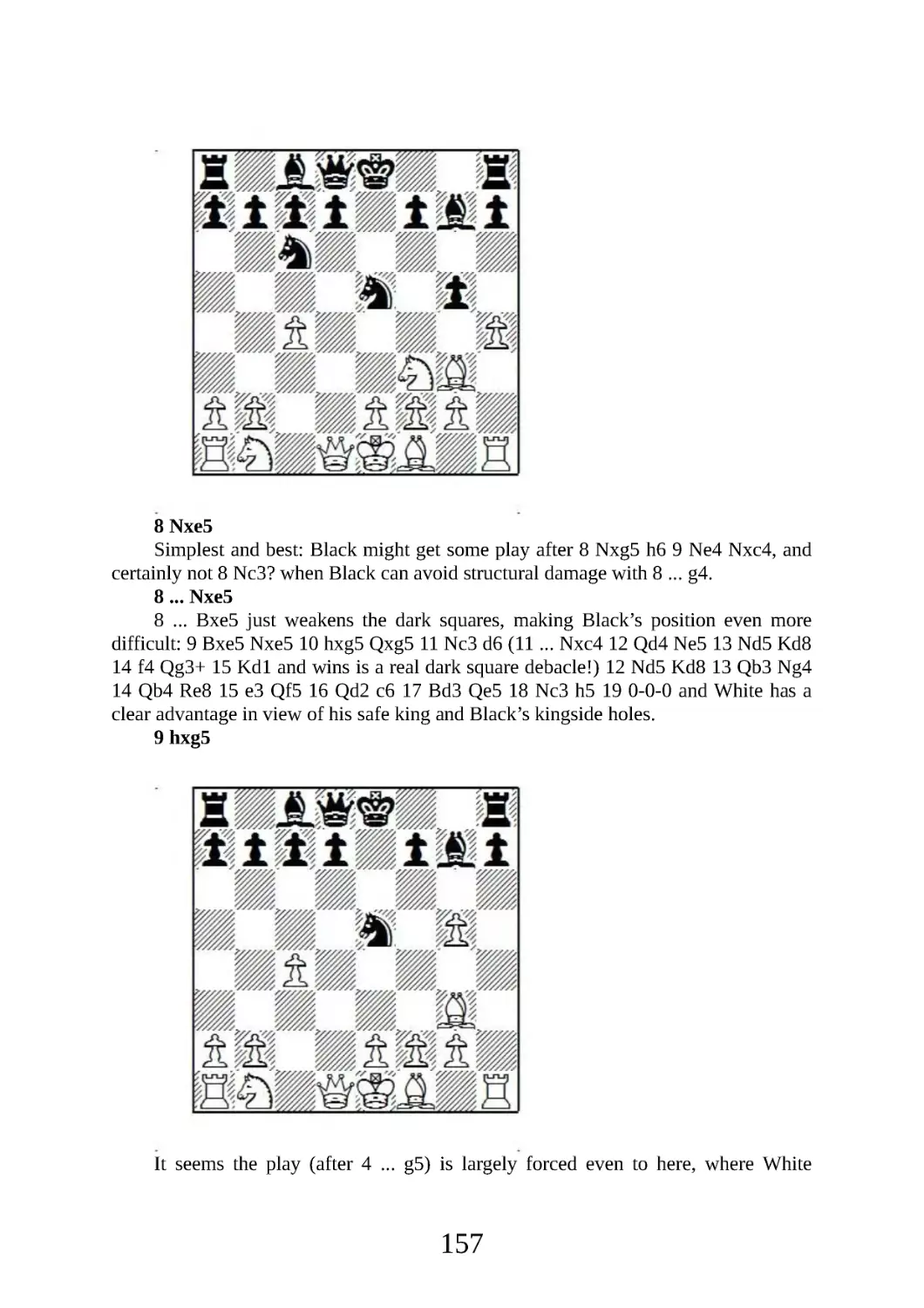

retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic,

magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the

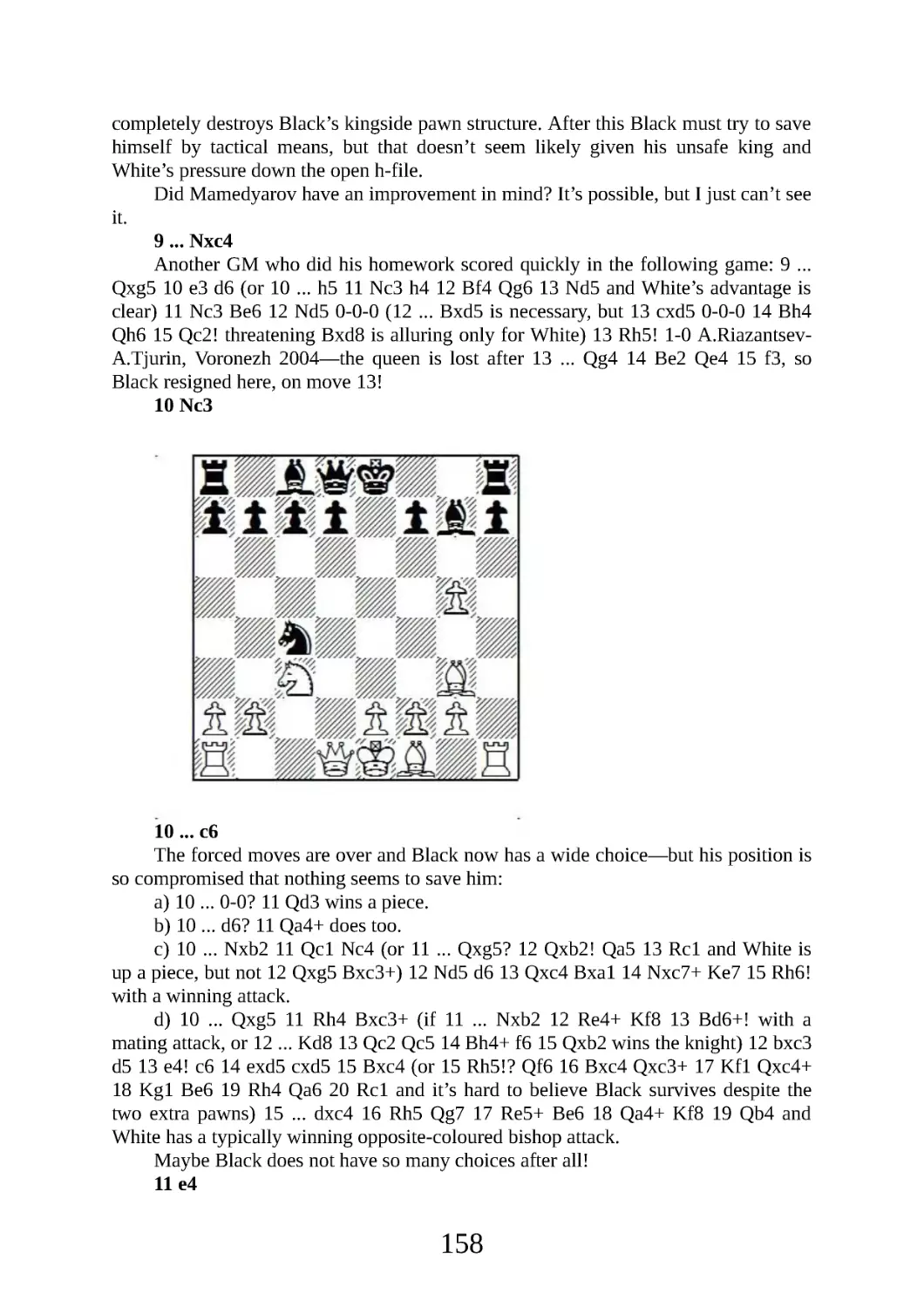

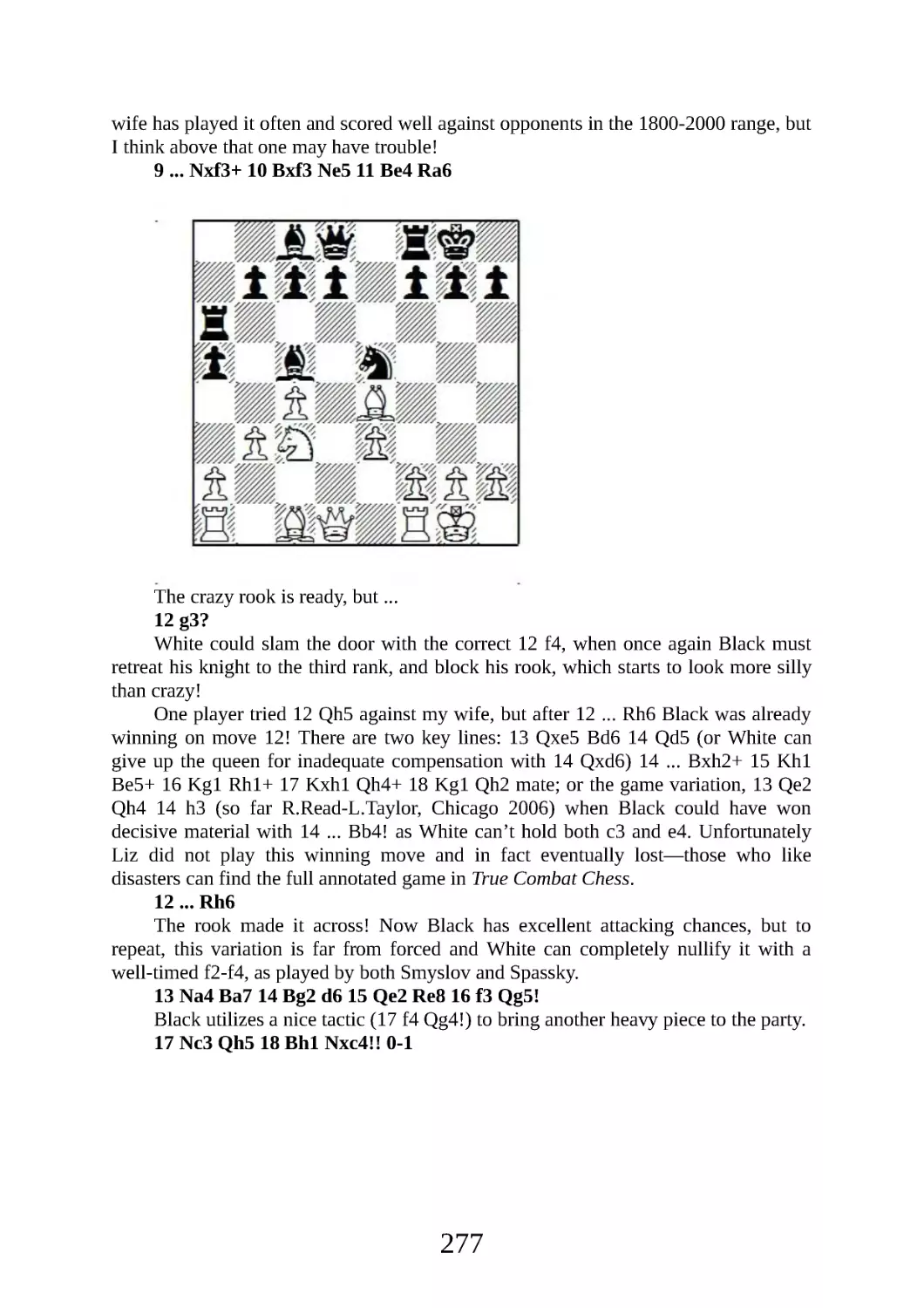

publisher.

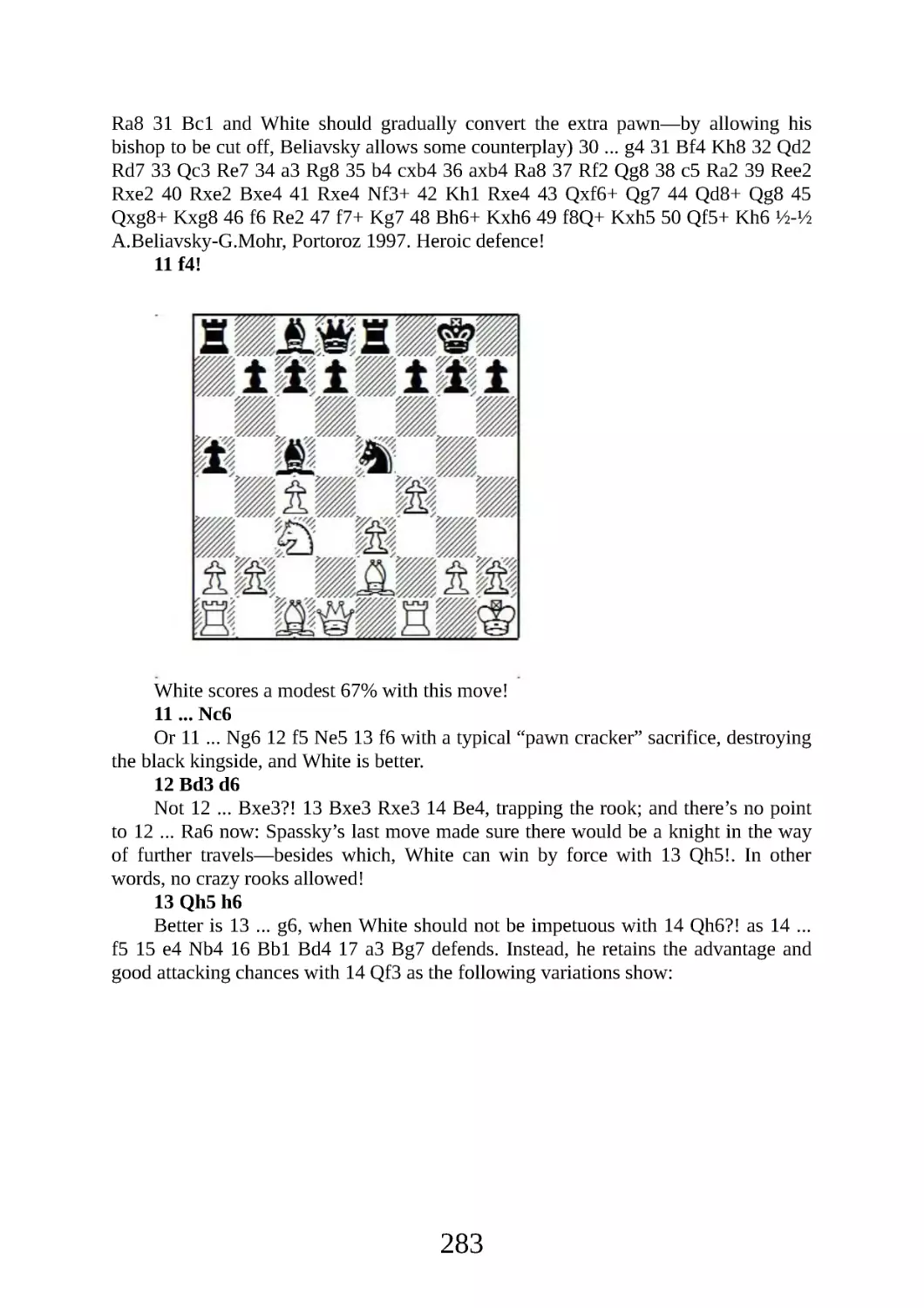

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

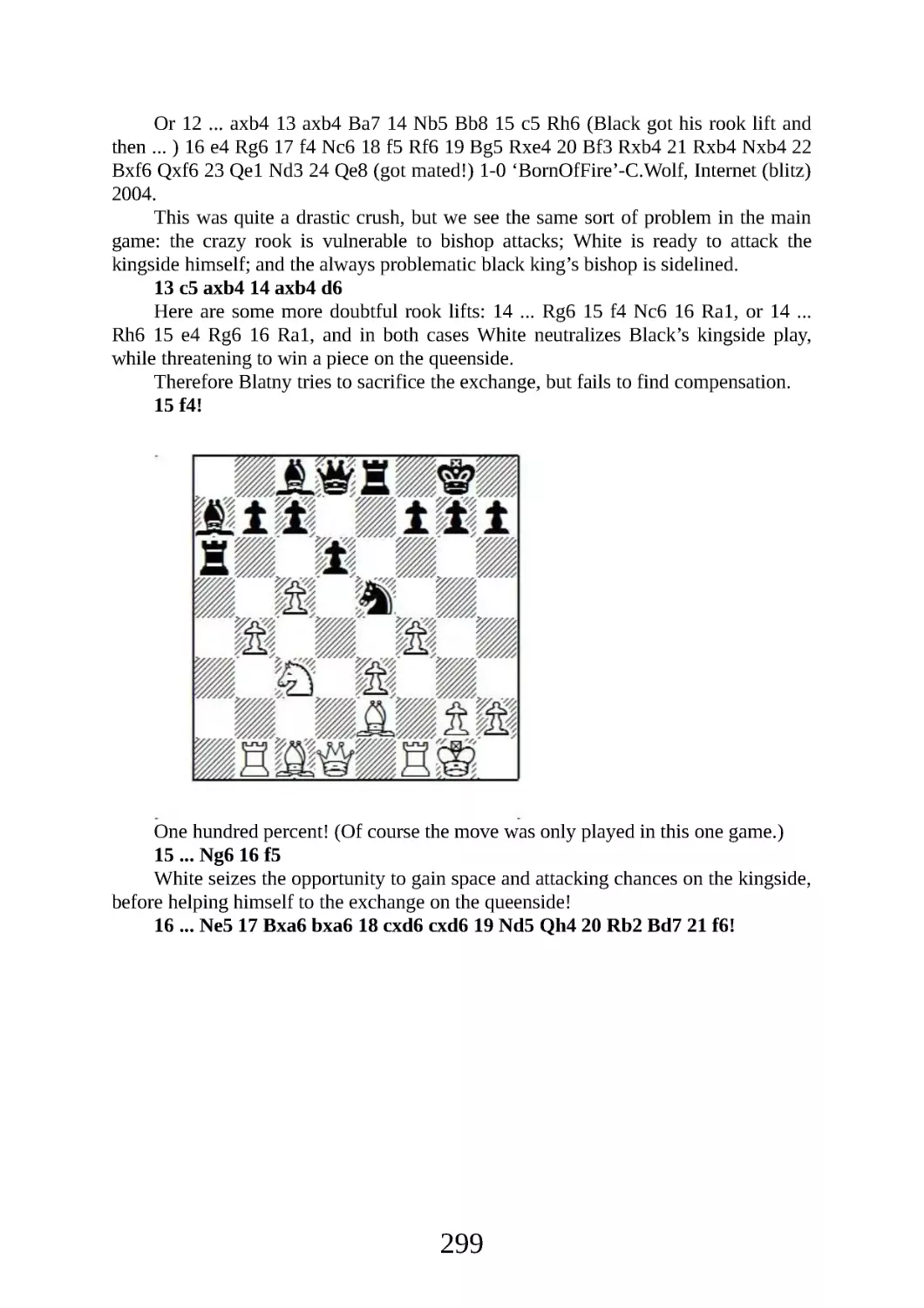

ISBN: 978 1 85744 753 8

Distributed in North America by The Globe Pequot Press, P.O Box 480,

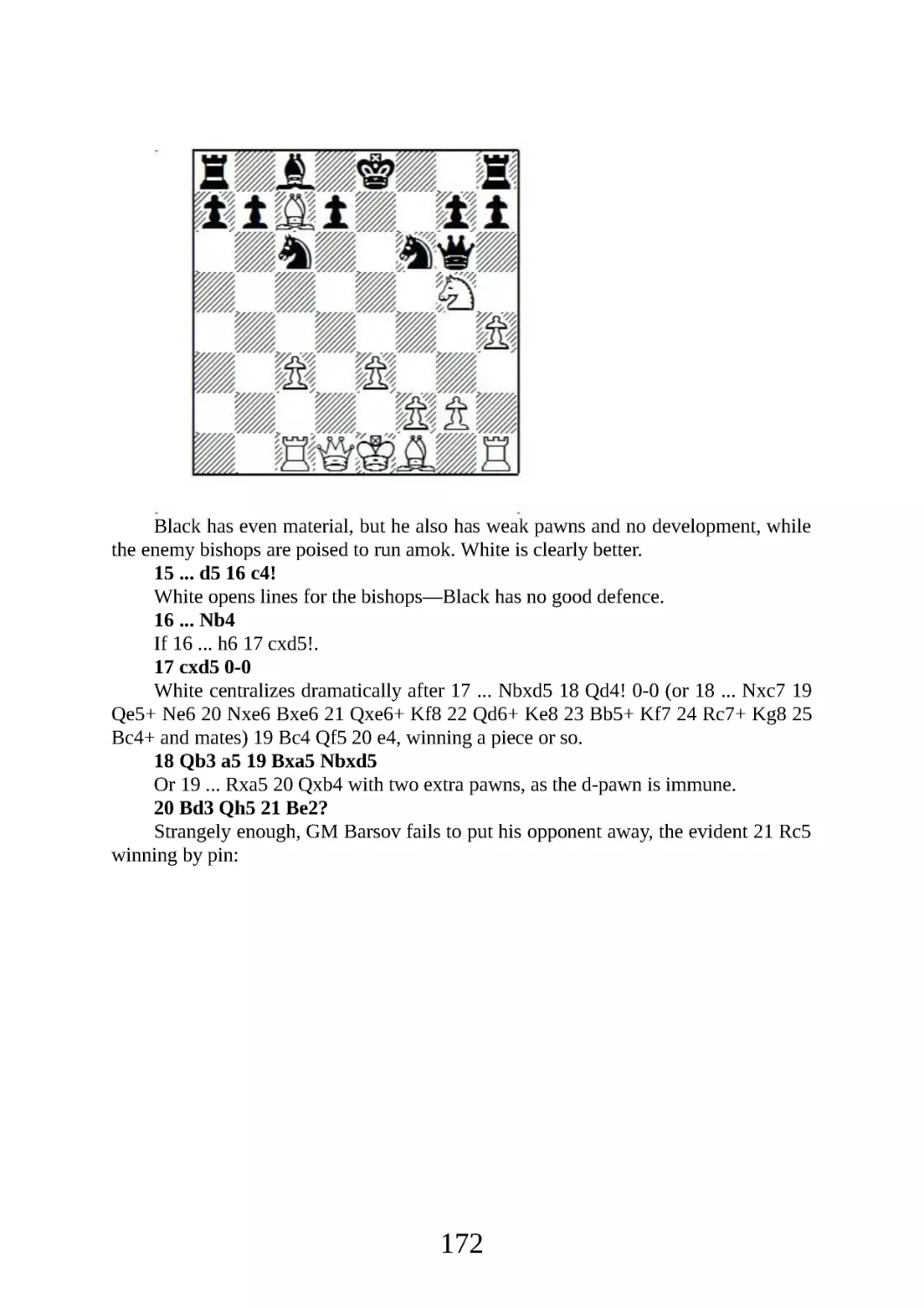

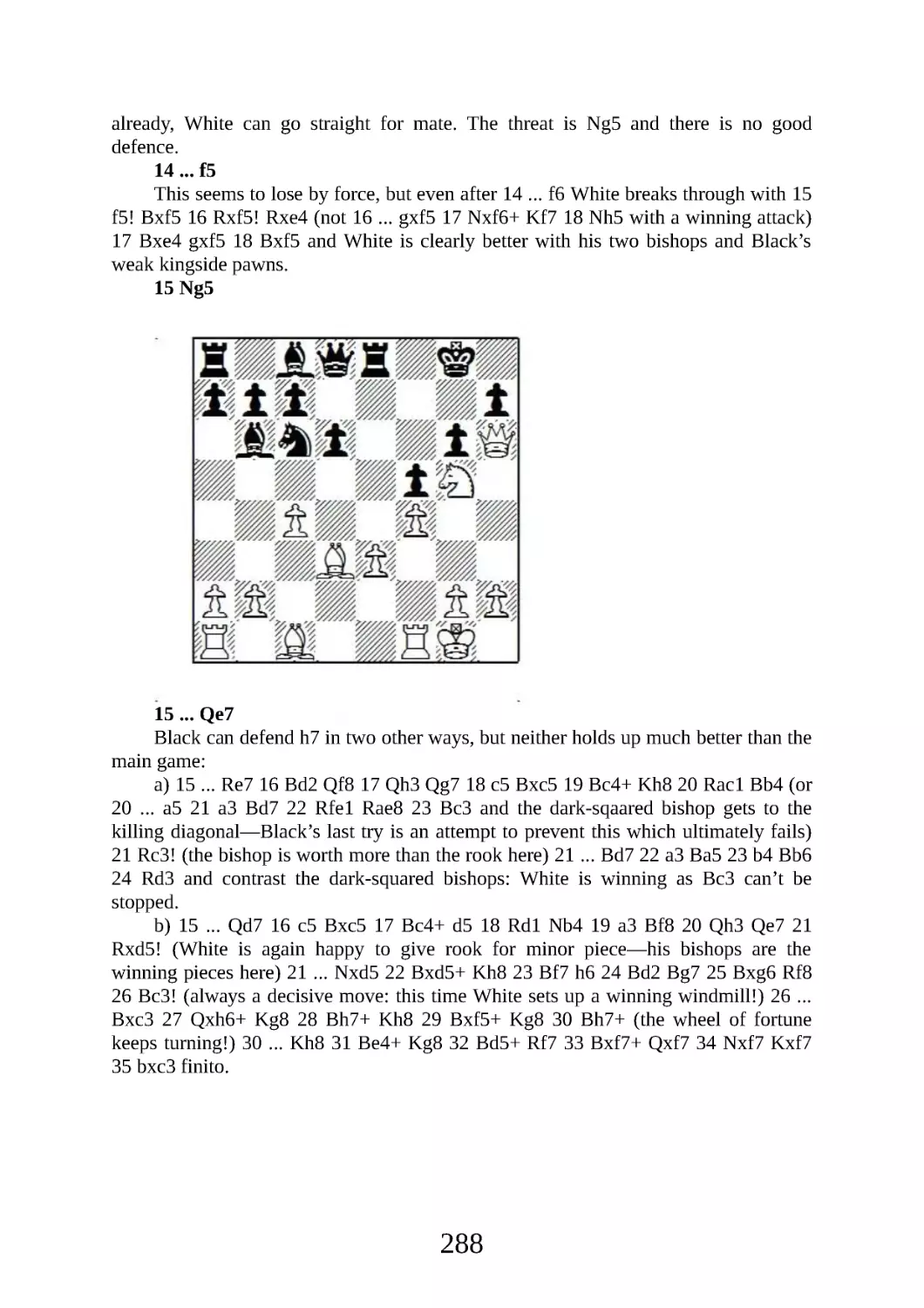

246 Goose Lane, Guilford, CT 06437-0480.

All other sales enquiries should be directed to Everyman Chess, Northburgh

House,

10 Northburgh Street, London EC1V 0AT

tel: 020 7253 7887 fax: 020 7490 3708

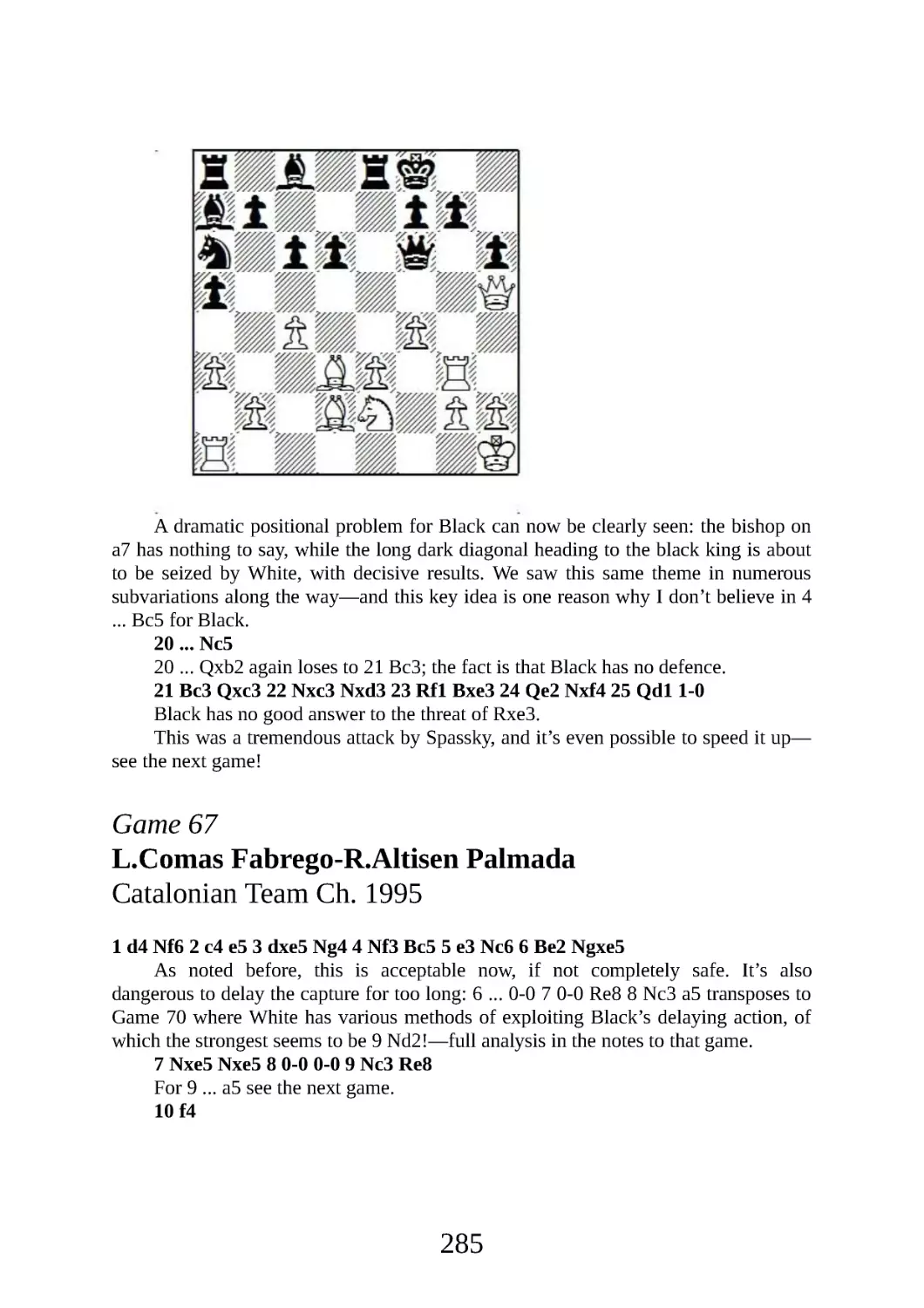

email: info@everymanchess.com; website: www.everymanchess.com

Everyman is the registered trade mark of Random House Inc. and is used in this

work under licence from Random House Inc.

To my beautiful wife Liz

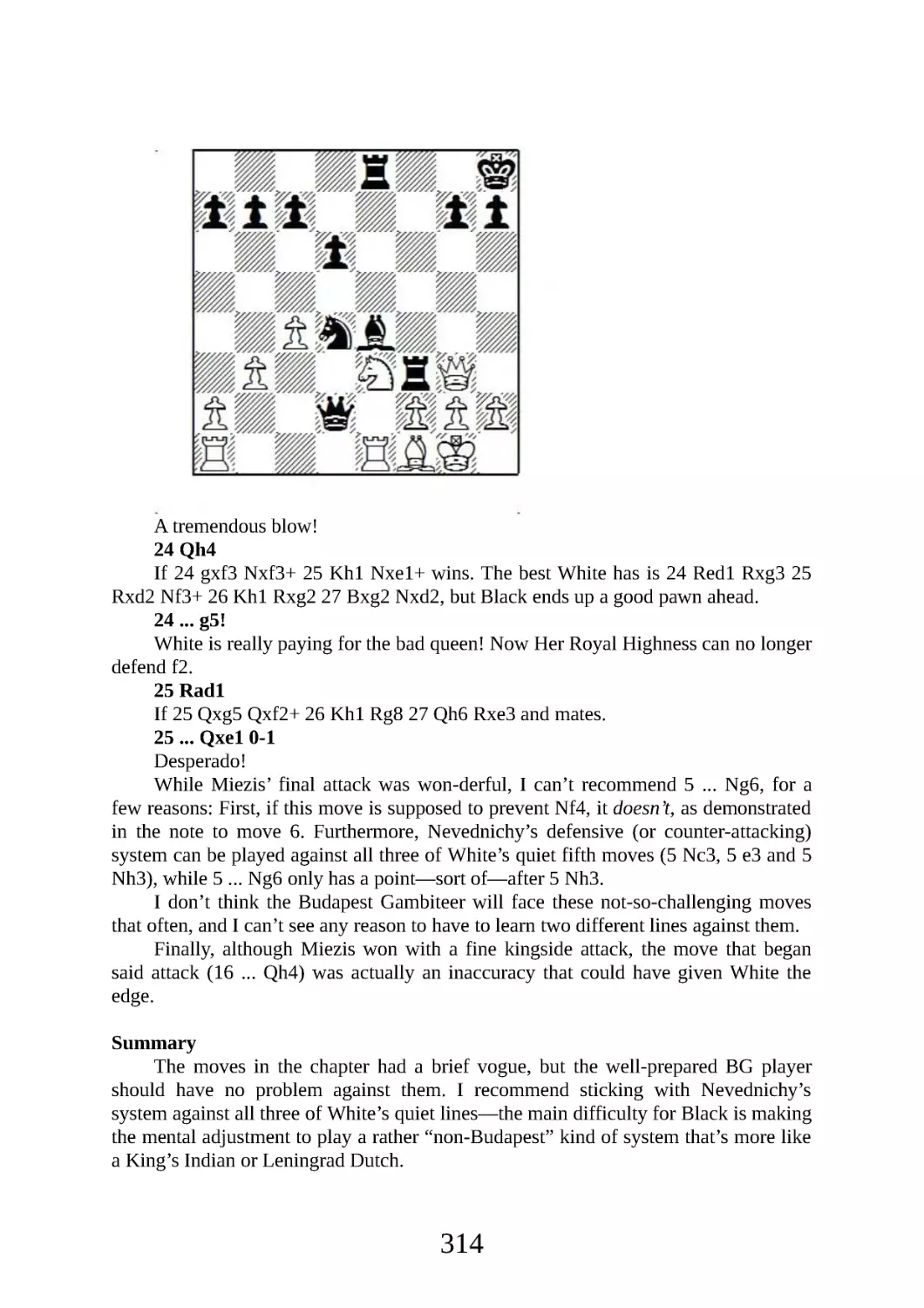

Everyman Chess Series

Chief advisor: Byron Jacobs

Commissioning editor: John Emms

Assistant editor: Richard Palliser

Typeset and edited by First Rank Publishing, Brighton.

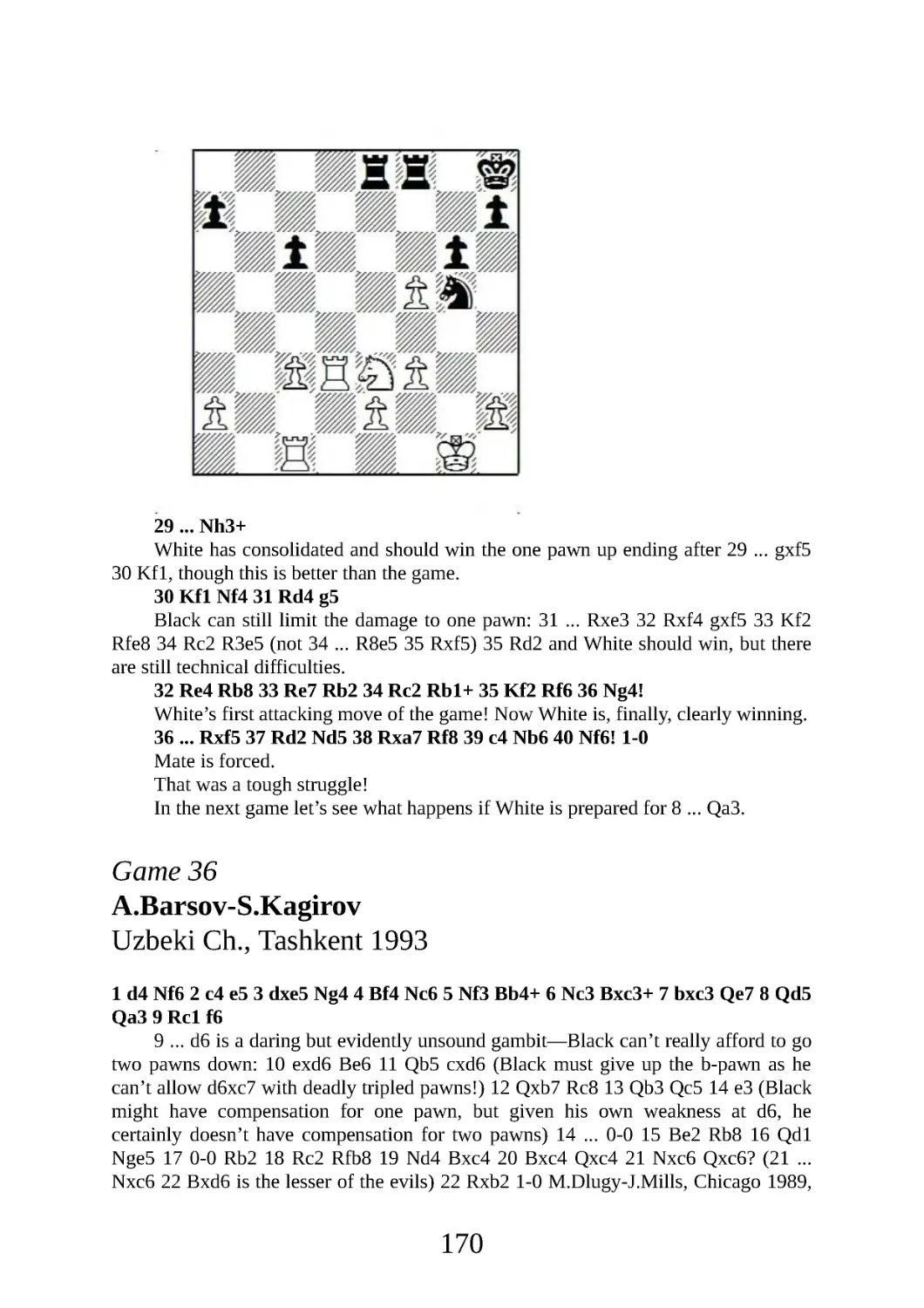

Cover design by Horatio Monteverde.

Printed and bound in the US.

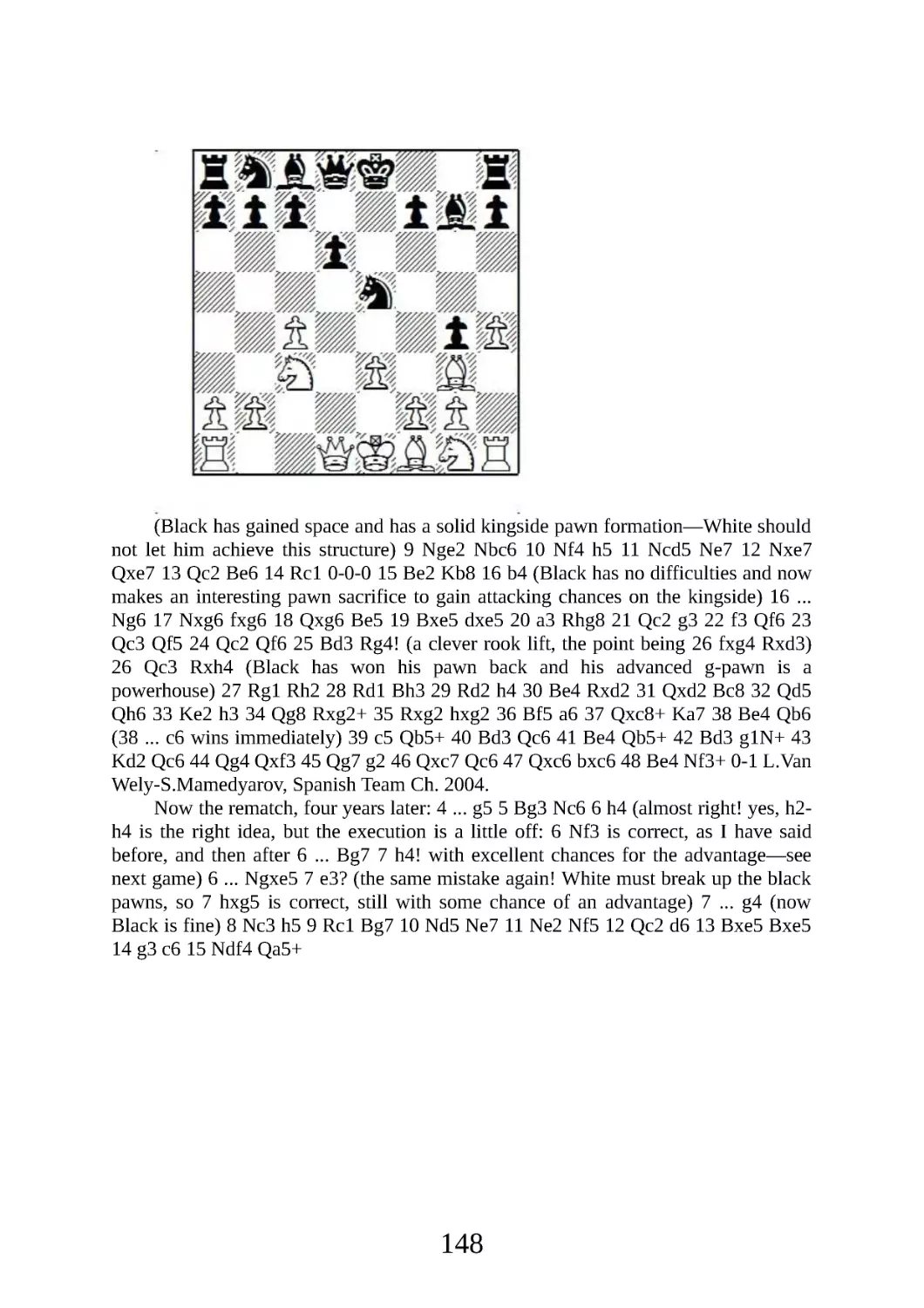

3

Contents

Bibliography

Introduction

Part I: The Alekhine Attack (4 e4)

1 The Alekhine Attack as played by Alekhine

2 Deviations

3 Alekhine Attack vs. 5 ... Ng6

4 Alekhine Attack vs. 5 ... Nec6

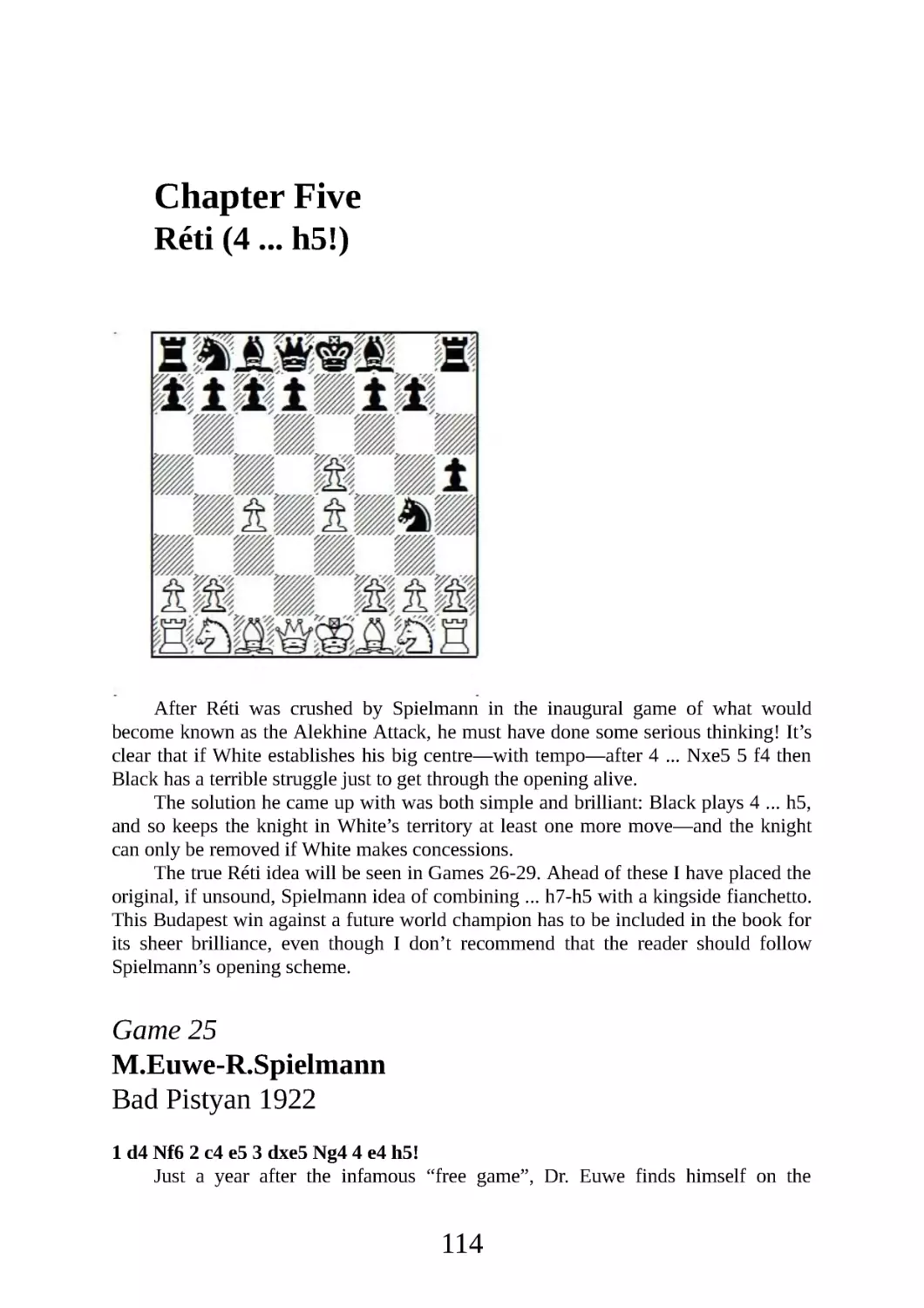

5 Réti (4 ... h5!)

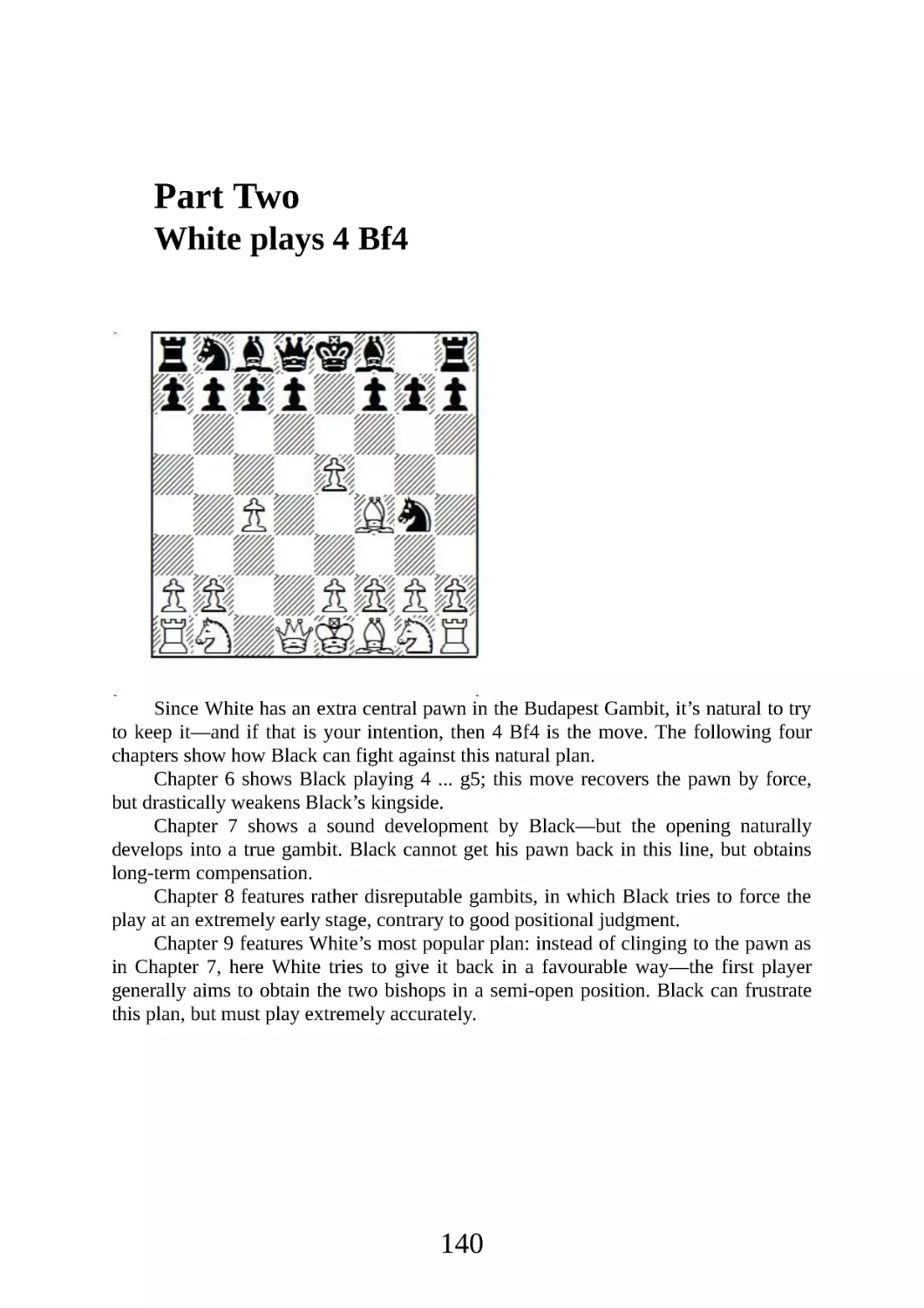

Part II: White plays 4 Bf4

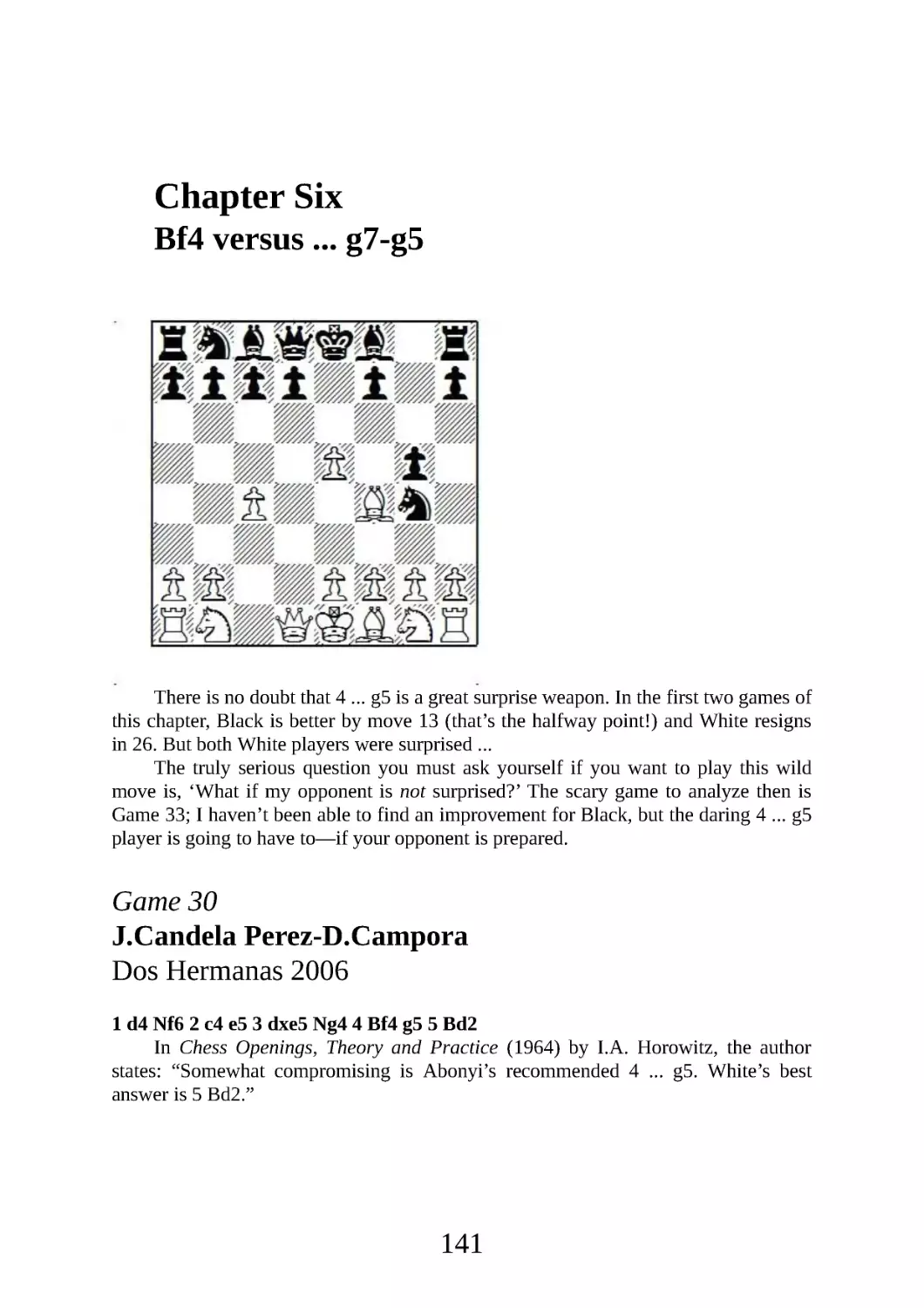

6 Bf4 vs. . .. g7-g5

7 The Original Budapest Gambit (Bf4 and Nc3)

8 Black Gambits against 4 Bf4

9 Bf4 Main Line with Nbd2

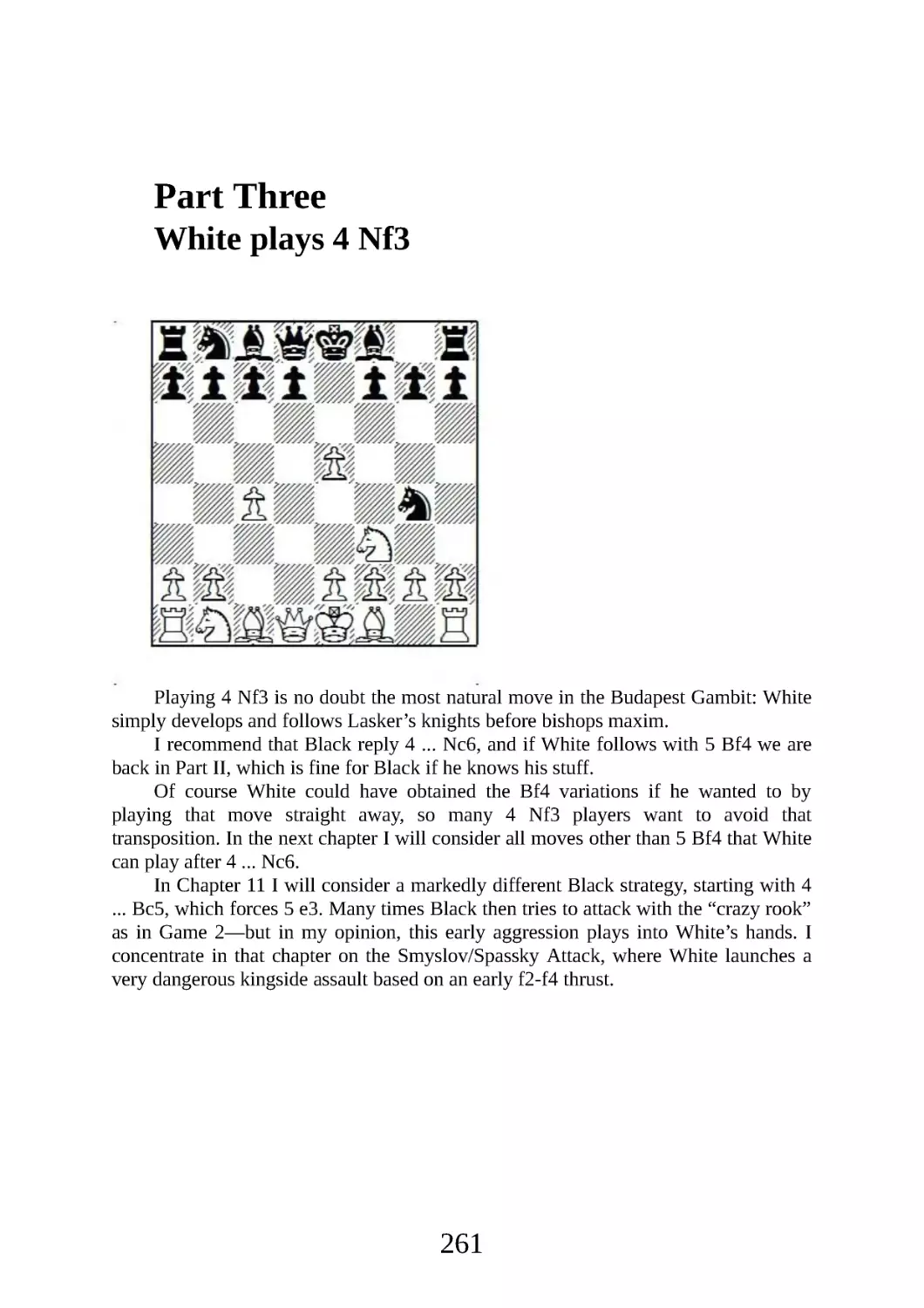

Part III: White plays 4 Nf3

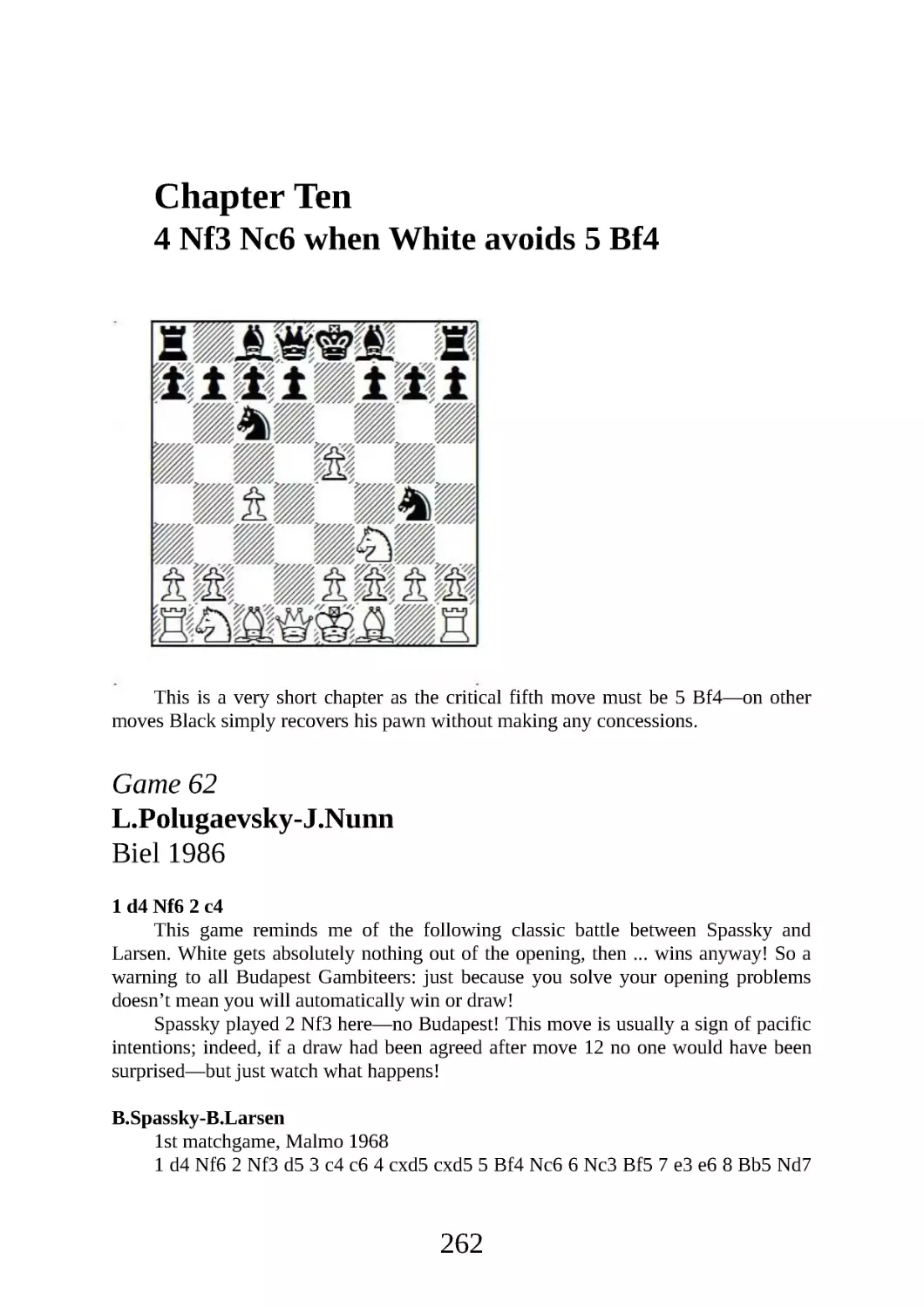

10 4 Nf3 Nc6 when White avoids 5 Bf4

11 4 Nf3 Bc5

Part IV: Unusual Lines

12 The Quiet Ones: 4 Nc3, 4 e3, 4 Nh3

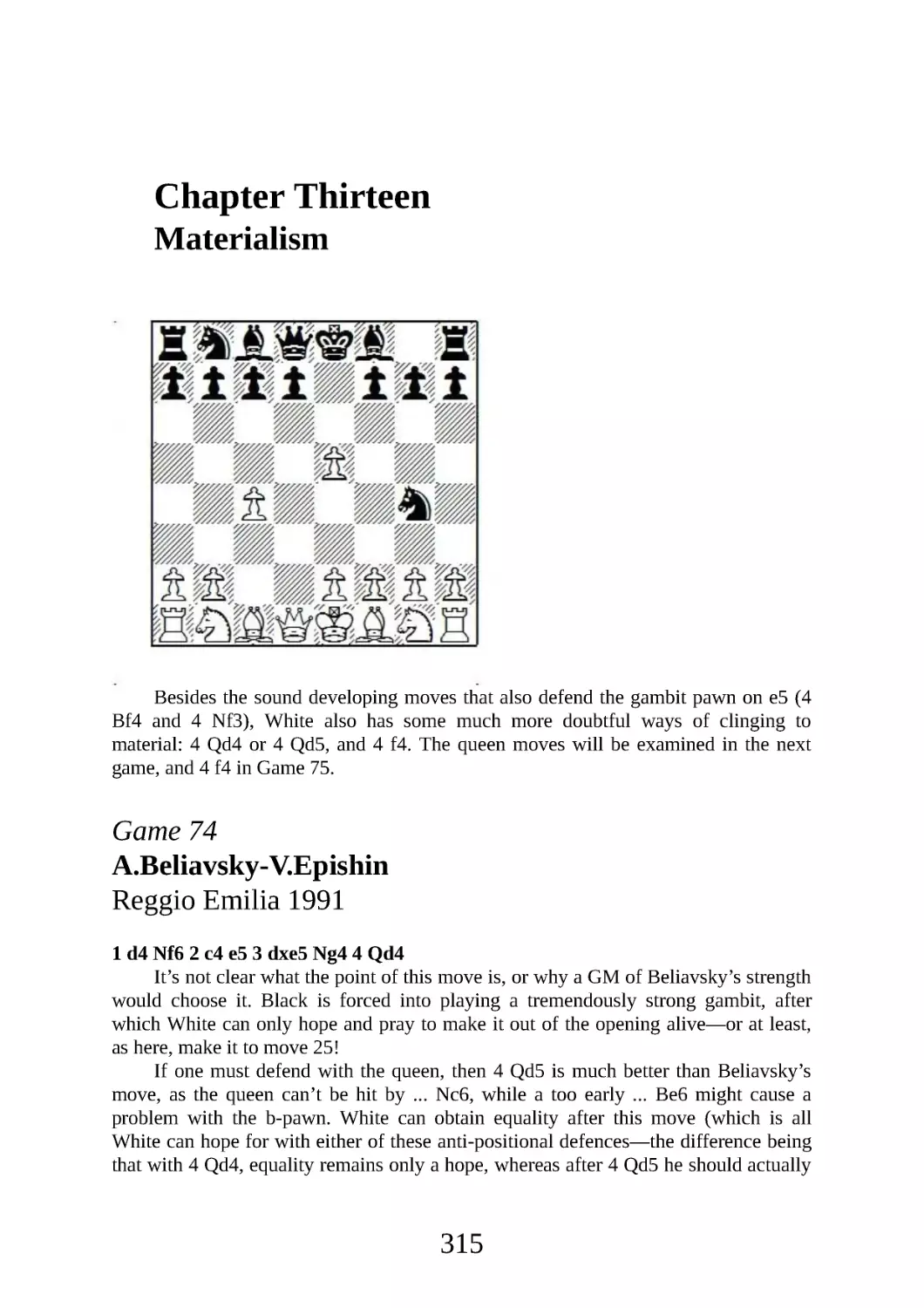

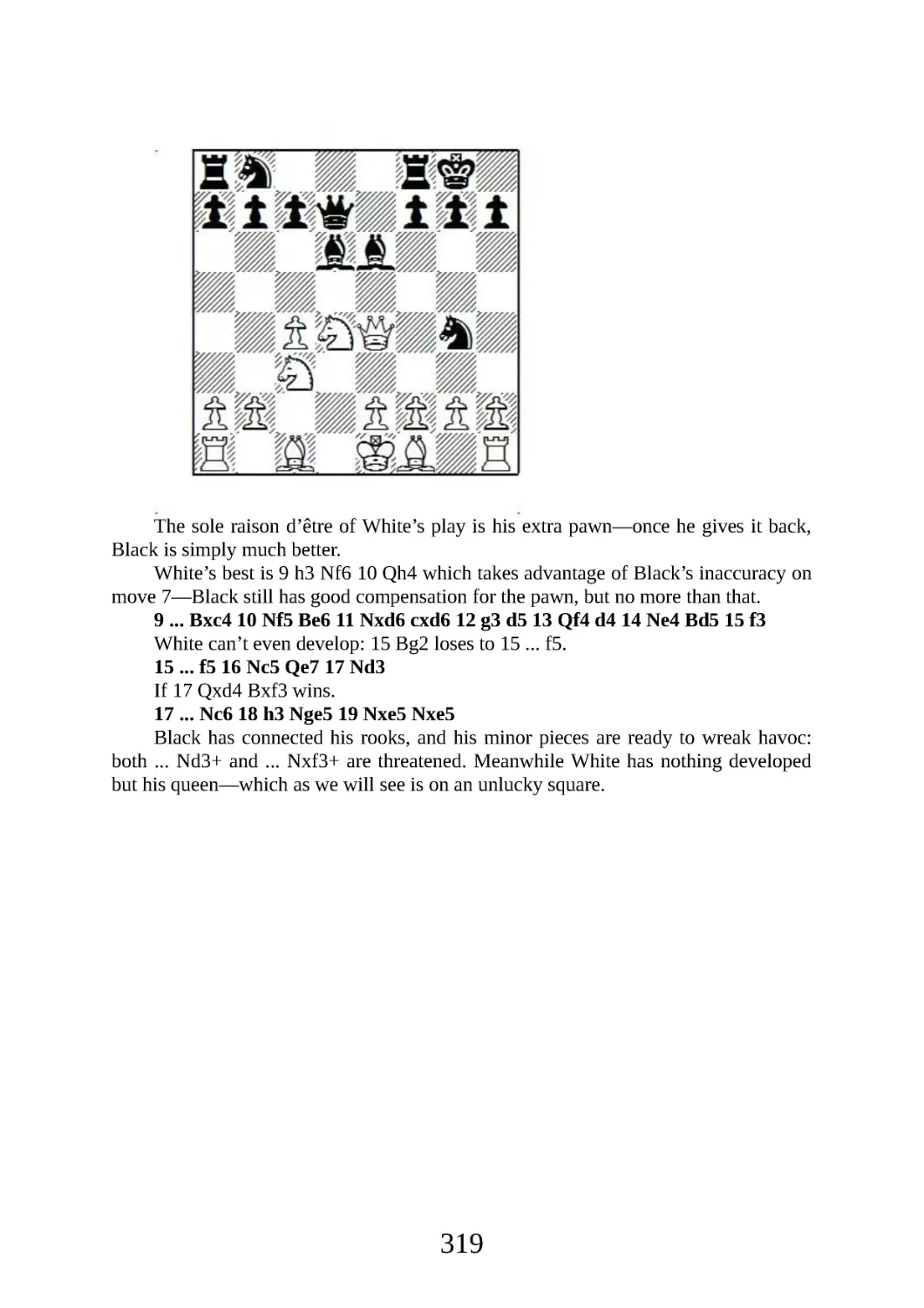

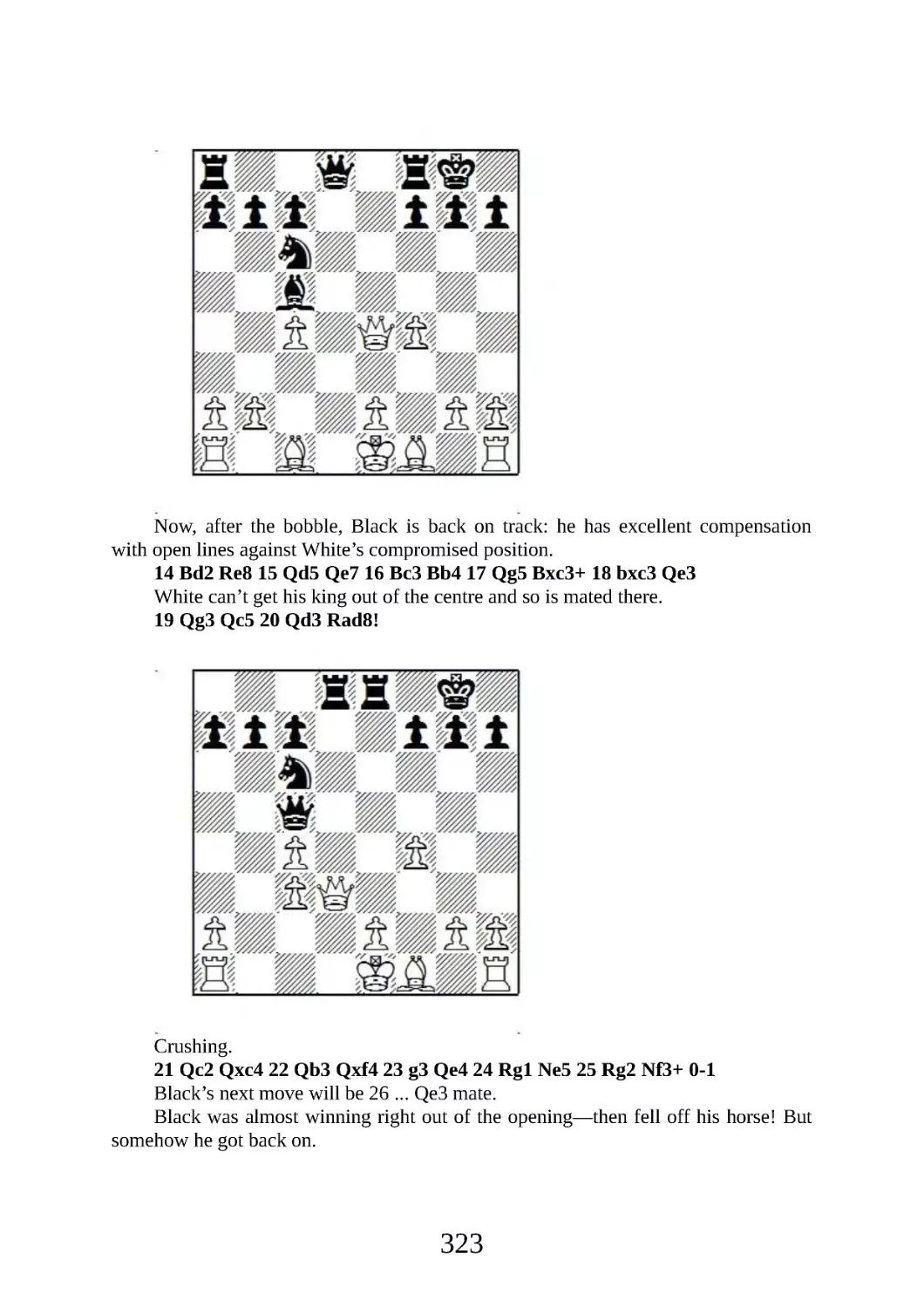

13 Materialism

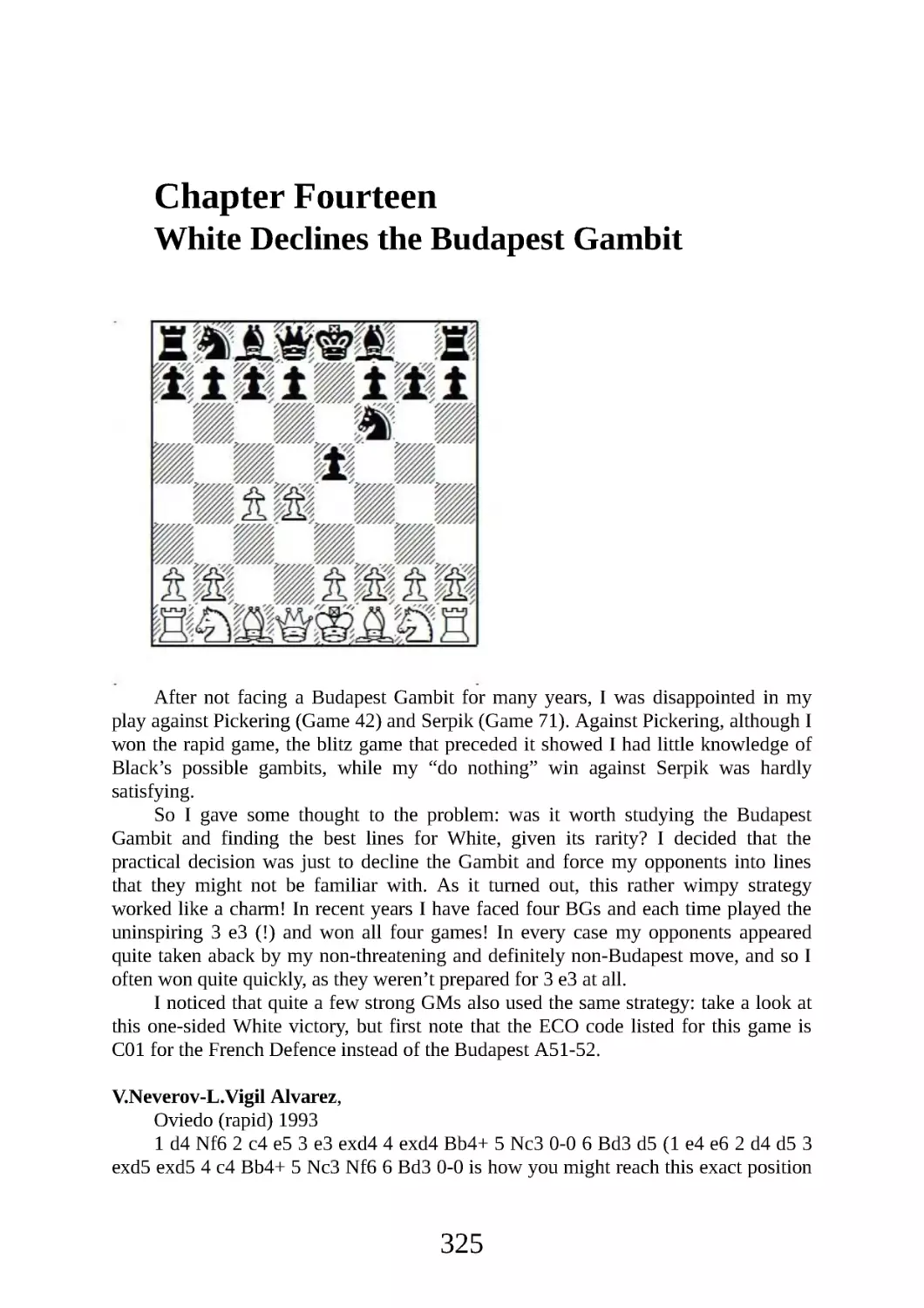

14 White Declines the Budapest Gambit

15 The Fajarowicz Gambit

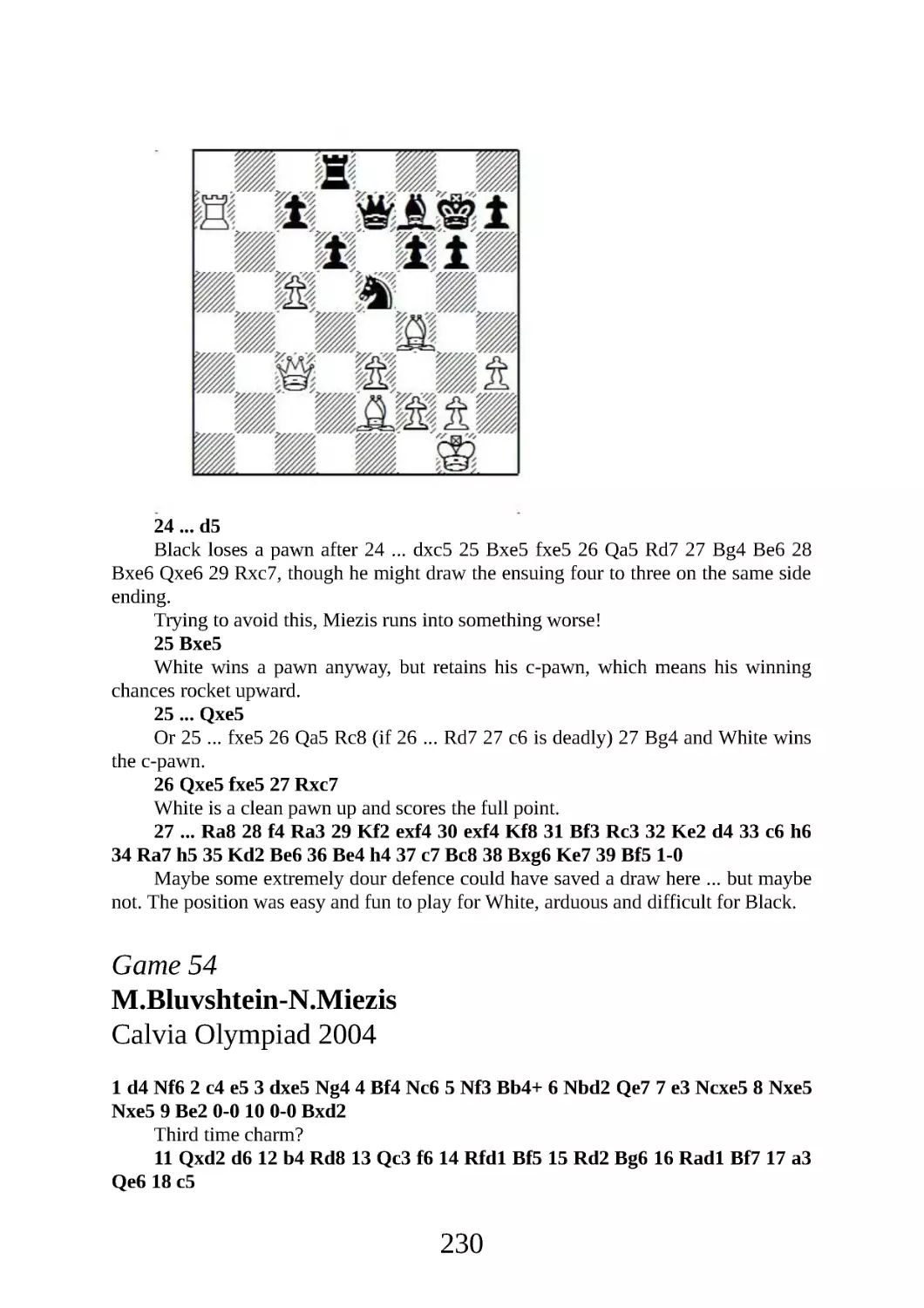

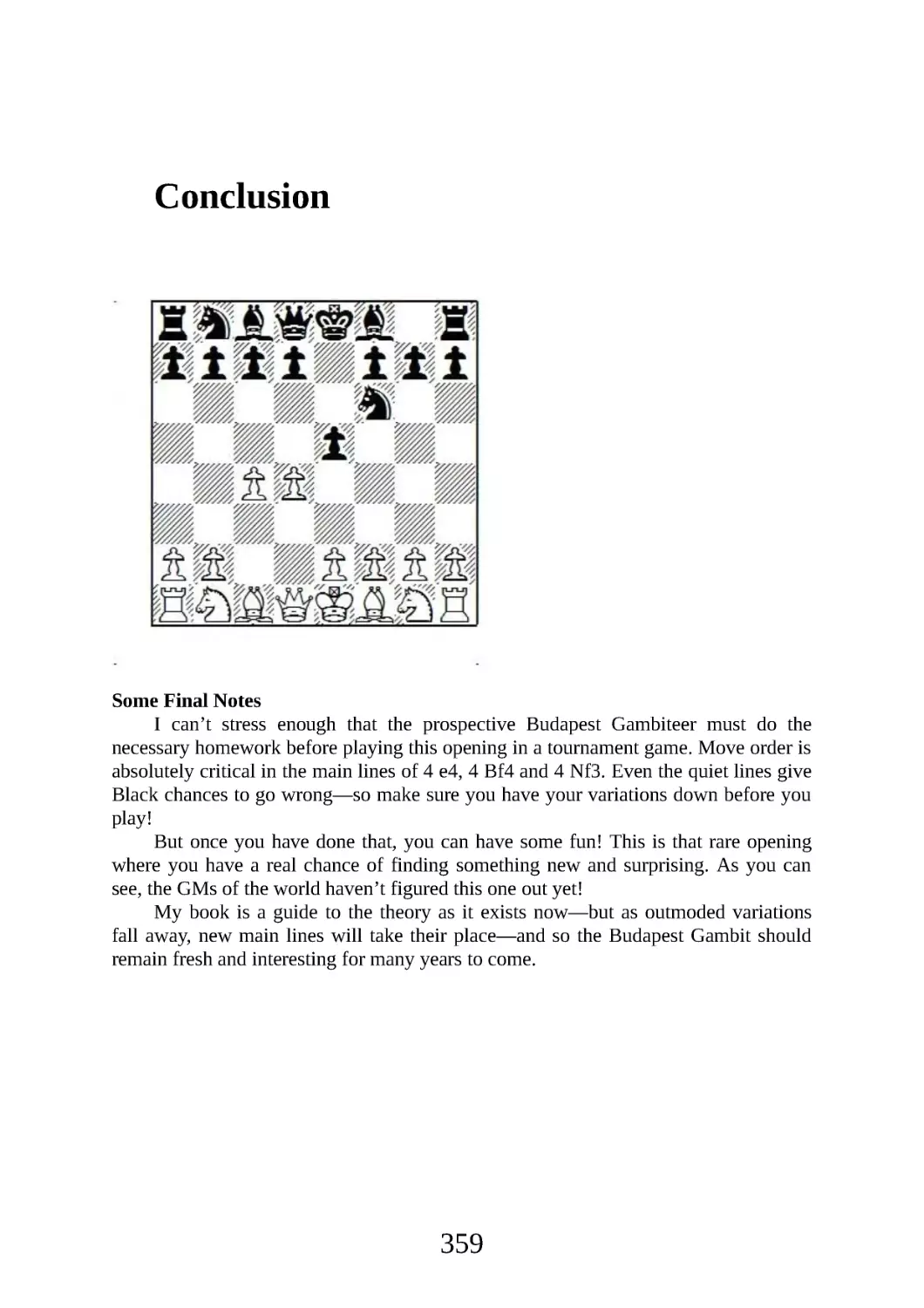

Conclusion

Index of Complete Games

4

Bibliography

Books

The Fabulous Budapest Gambit, Viktor Moskalenko (New in Chess 2007)

Budapest Fajarowicz, Lev Gutman (Batsford 2004)

My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937, Alexander Alekhine (G. Bell and Sons

1969)

Chess Openings Theory and Practice, I.A . Horowitz (Simon and Schuster 1964)

My Great Predecessors, Volumes I and IV, Garry Kasparov (Everyman

2003/2004)

Computer Programs and Databases

Chessbase.com

Fritz 11

Megabase 2008

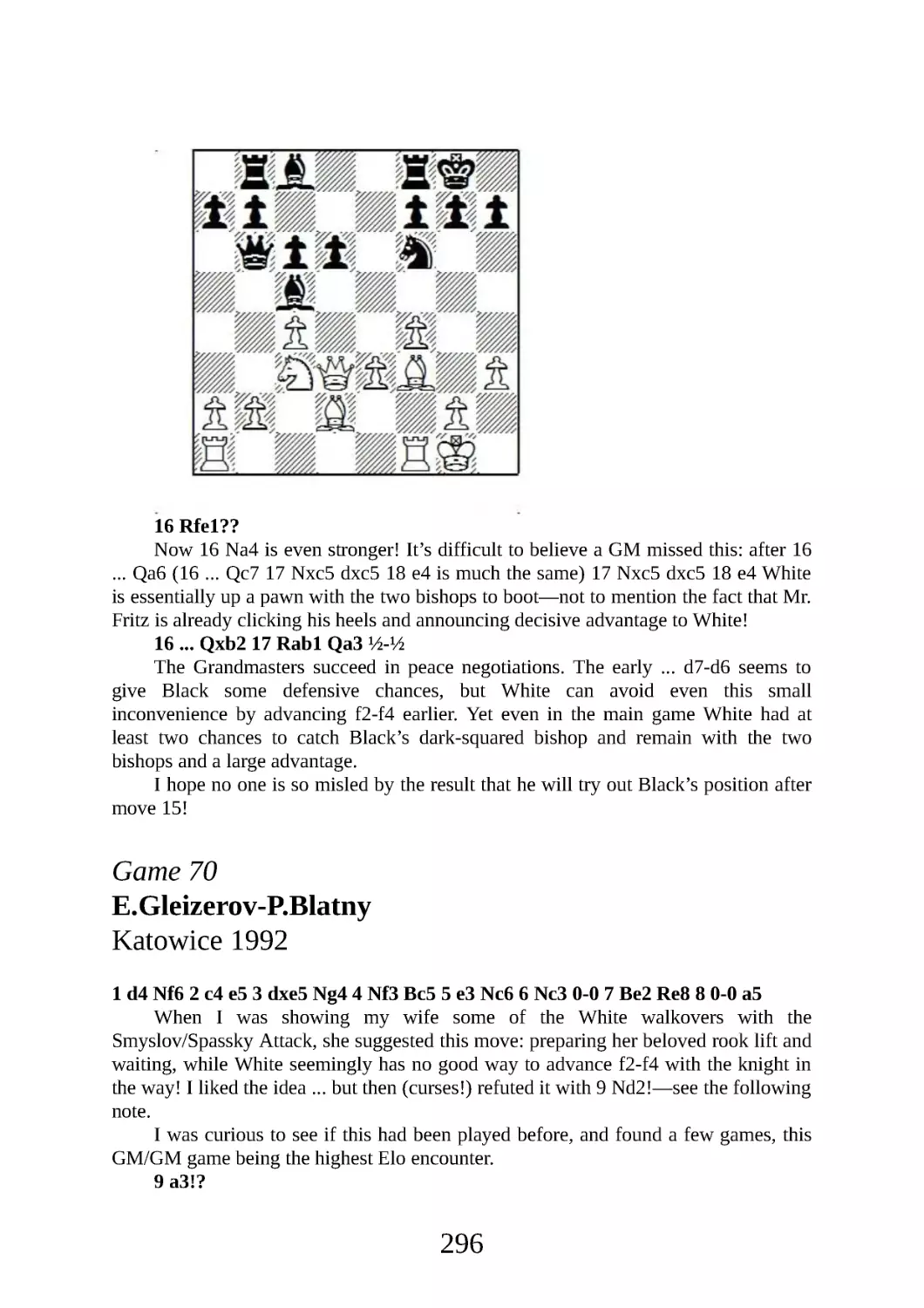

MegaCorr4 (ChessMail)

Correspondence Database 2006 (ChessBase)

Chessgames.com

Acknowledgment

Extra special thanks to the champion of tournament organizers,

Mr. Budapest himself, Laszlo Nagy

5

Introduction

Let’s get to the heart of the matter right away: after months of hard work analyzing the

Budapest Gambit, in almost every case turning over barrels of conventional wisdom, I

have come to two clear conclusions, which are:

One: the Budapest Gambit is sound, and can be played at the highest level.

Two: the opening is quite difficult to play.

Elaborating on the second point, the main thing I noticed was that the BG is not a

“feel” opening. One can’t just learn a few ideas and then happily play the gambit in a

tournament game. In fact, every line demands accurate calculation, strong strategical

play and precise move orders.

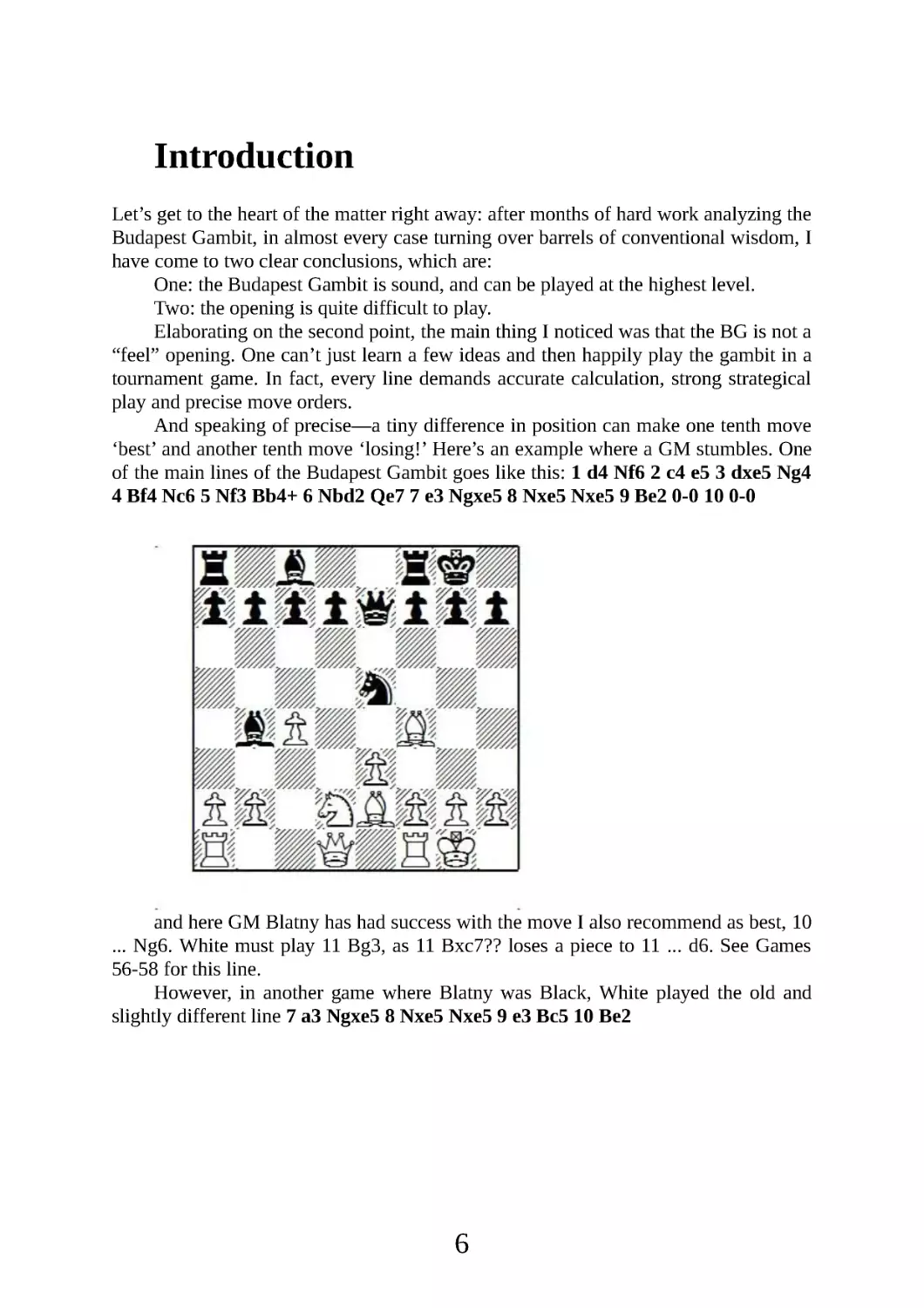

And speaking of precise—a tiny difference in position can make one tenth move

‘best’ and another tenth move ‘losing!’ Here’s an example where a GM stumbles. One

of the main lines of the Budapest Gambit goes like this: 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4

4 Bf4 Nc6 5 Nf3 Bb4+ 6 Nbd2 Qe7 7 e3 Ngxe5 8 Nxe5 Nxe5 9 Be2 0-0 10 0-0

and here GM Blatny has had success with the move I also recommend as best, 10

... Ng6. White must play 11 Bg3, as 11 Bxc7?? loses a piece to 11 ... d6. See Games

56-58 for this line.

However, in another game where Blatny was Black, White played the old and

slightly different line 7 a3 Ngxe5 8 Nxe5 Nxe5 9 e3 Bc5 10 Be2

6

and now 10 ... d6 is correct, blocking the f4-bishop, but evidently confusing

variations (it’s the same move number, but just that little, crucial bit different) Blatny

played 10 ... Ng6 and White answered 11 Bxc7, taking a clear pawn, as 11 ... d6 does

nothing here since the bishop escapes via a5 (see the notes to Game 61 for this

debacle).

In other words it’s possible to lose right in the opening if you’re not careful.

Here’s an even more drastic example. I devote no less than five chapters to the

Alekhine Attack—which I think is the critical test of the Budapest Gambit—that

begins 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 with the idea 4 ... Nxe5 5 f4, when White

has an extended Maróczy Bind and central domination. If Black allows this attack, he

is doomed to a difficult defence, as the first four chapters demonstrate. Therefore I

recommend Réti’s brilliant counterstroke 4 ... h5, which is analyzed in depth in

Chapter 5. My feeling is that the critical move thus comes on move 4 (!) and it’s

possible to be blown off the board if you miss it!

Another critical move comes in the popular variation 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5

Ng4 4 Nf3 and again Black faces a critical choice on move 4. I advocate 4 ... Nc6, as I

haven’t found any good defence to the Smyslov/Spassky Attack that occurs after 4 ...

Bc5 5 e3 and a later f2-f4 for White, where it often turns out that the bishop is

misplaced on c5, and White can attack the black king along the long diagonal.

So you have been warned!

But there is an upside, and a substantial one: if you do your homework, both by

studying this book and using your chess engine and especially, by thinking

independently (there are many new ideas to be found in the opening, often very early

in the game) then you, as Black, will have a significant advantage over your opponent.

I play 1 d4 as my main opening, and I only encounter a Budapest Gambit about once a

year. I think this is typical—so very few White players will have your expertise, and

even better for you, they might think the Gambit is unsound! These players may well

try to keep the gambit pawn, giving you the opportunity to win with savage attacks

(take a look at Games 34, 38, 39 and 73 among others).

7

There is also another, rather peculiar advantage to becoming a Budapest

Gambiteer. Many White 1 d4 players are uncomfortable playing against the Budapest

and so avoid it altogether. After 1 d4 Nf6—when they see that gleam in your eye!—

they play 2 Nf3 (most often) or sometimes 2 Bg5, and obviously the Budapest is not

possible after either of these moves, but the Trompowsky has been pretty well

defanged by 2 ... e6, and 2 Nf3 is just too quiet to give White very much.

Some personal statistics are appropriate here: after I signed on to write this book,

I tried to obtain the BG over the next seven months, in the course of which I played in

several tournaments and had Black 23 times. How many Budapest Gambits? Zero!

The box score reads like this: 15 games where I faced 1 e4 (no BG there!), two games

where I faced 1 c4, one 1 Nf3, and only five that started 1 d4 Nf6. Of those five, two

of my opponents went for the Trompowsky with 2 Bg5 (one of them made a draw),

and three went for “safety” (they didn’t get it!) with 2 Nf3. The result is that with

Black against 1 d4 I won four and drew only one against these less ambitious

openings, but I couldn’t get the Budapest!

Now don’t let this discourage you! By playing 1 ... Nf6, by somehow hinting that

you are about to throw a sharp gambit in White’s face, you often induce your opponent

to play a move that is simply inferior to the objectively best 2 c4.

Add in my 90% score against these second best moves and one can see that these

alternatives are simply not dangerous if one is well prepared. I would recommend that

any prospective Budapest player should also check out John Cox’s excellent book on

just that subject, Dealing with d4 Deviations, in which he maintains his enthusiasm

while writing about some of the most mind-numbingly boring openings in all of chess!

Now let’s get back to the subject at hand, the far from boring Budapest Gambit

which occurs after 2 c4 e5 (and it’s worth noting that, despite my personal statistics,

according to the Chessbase.com Opening Explorer, 2 c4 is by far the most likely move

— in fact it’s played more than three times as often as the second most popular, 2 Nf3).

I have tried to be objective throughout the book—after all, as a d4 player I want

to know the strongest line against the gambit, as well as Black’s best counterplay.

And objectively speaking, the Alekhine Attack must be the sternest test of the

gambit. From a practical point of view, however, 4 Nf3 is dangerous as so many

Budapest Gambiteers will follow old paths and try 4 ... Bc5, when the second player ’s

game is quite difficult (see Chapter 11). I don’t think 4 Bf4 is a big threat to the

Gambit’s existence, but (as Blatny’s mishap showed) Black must play extraordinarily

precisely. Even the best players in the world (see Chapter 9) have gone seriously astray

in this position, but I think Black is fine as long as he does not stick to outmoded

variations.

Other moves besides the big three (4 e4, 4 Bf4, 4 Nf3) should not trouble Black,

and declining with something like 3 e3 is likewise nothing if Black is prepared.

To complete this introduction, I offer two games of former World Champion

Vladimir Kramnik, who has been known to walk both sides of the Budapest street, and

a short win of my own, in the course of which the layout of the book is explained.

Game 1

8

V.Kramnik-S.Mamedyarov

Nice (rapid) 2008

After this game, many people asked, “How did the World Champion lose to the

Budapest Gambit?”

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 Nc3

This quiet move (along with 4 e3 and 4 Nh3) is focused on controlling d5

without spending any time trying to hold onto the extra pawn. These variations will be

fully examined in Chapter 12.

4 ... Nc6

As we will learn in the above cited chapter, this is already not so accurate—but I

find it refreshing to see an opening so little explored that a GM can make an

inaccuracy on move 4!

Since the pawn is unguarded, Black should take it: 4 ... Nxe5. If White continues

quietly with 5 e3, Black should play 5 ... d6 which gives his knight a retreat, prepares a

kingside fianchetto, and most important, retains the option of ... c7-c6 to kick any

white knight that might drop in on d5. See Game 72 for this precise defence.

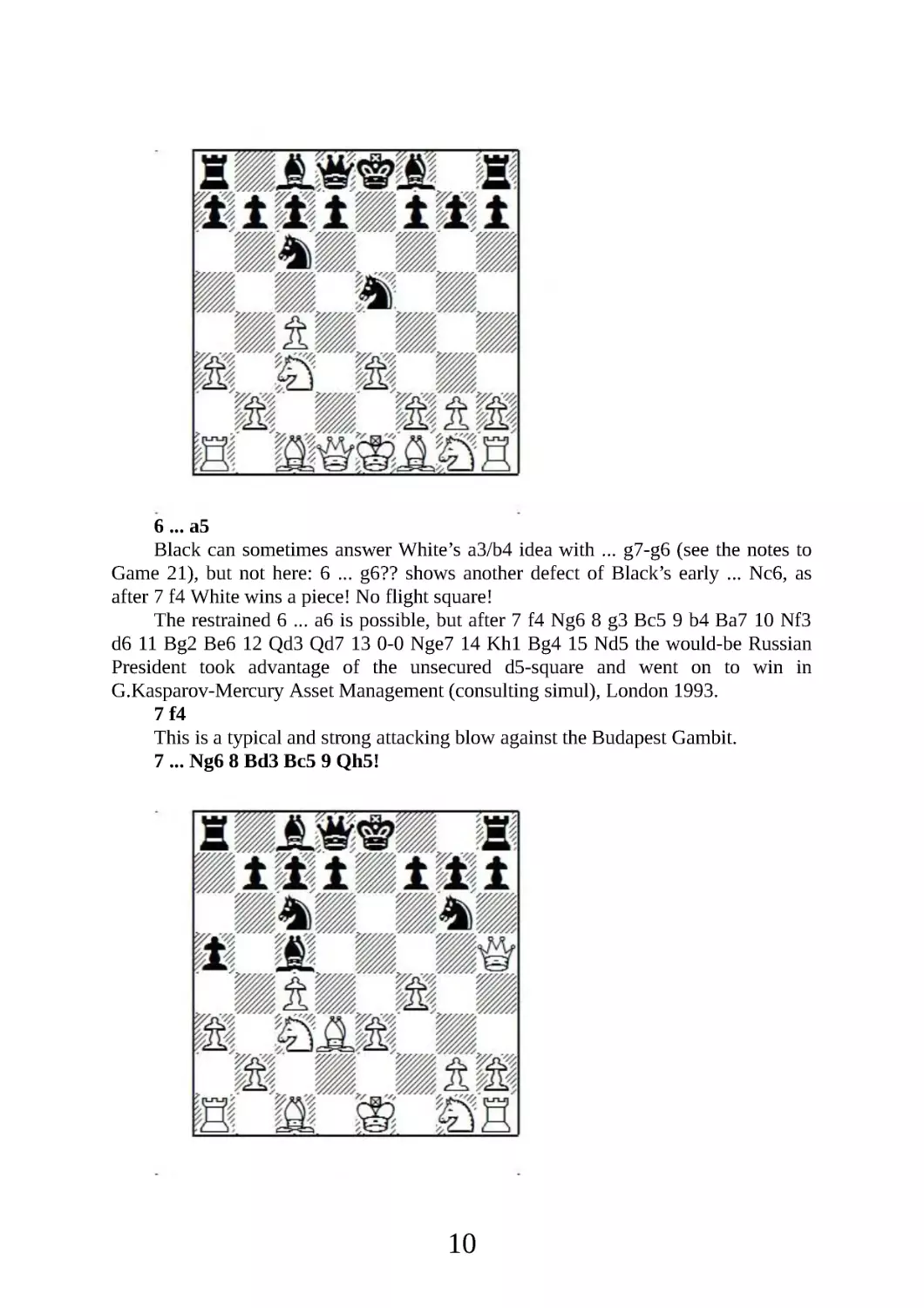

5 e3 Ngxe5 6 a3

9

6 ... a5

Black can sometimes answer White’s a3/b4 idea with ... g7-g6 (see the notes to

Game 21), but not here: 6 ... g6?? shows another defect of Black’s early ... Nc6, as

after 7 f4 White wins a piece! No flight square!

The restrained 6 ... a6 is possible, but after 7 f4 Ng6 8 g3 Bc5 9 b4 Ba7 10 Nf3

d6 11 Bg2 Be6 12 Qd3 Qd7 13 0-0 Nge7 14 Kh1 Bg4 15 Nd5 the would-be Russian

President took advantage of the unsecured d5-square and went on to win in

G.Kasparov-Mercury Asset Management (consulting simul), London 1993.

7 f4

This is a typical and strong attacking blow against the Budapest Gambit.

7 ... Ng6 8 Bd3 Bc5 9 Qh5!

10

Excellent! White attacks with gain of time. So far White has outplayed his

opponent.

9 ... d6!?

Here or on the next move Black should settle for a somewhat worse position—

instead he continues his “subtle” manoeuvres and walks to the edge of the precipice.

Best is 9 ... Qh4+ 10 Qxh4 Nxh4 11 g3 Ng6 12 Nf3 d6 (but not 12 ... 0-0?! 13

Nd5 Bd6 14 e4, when Black’s cramped position collapses in view of the weakness at

c7) 13 Nd5 Kd8 14 Ng5 Be6 15 Bd2 Nge7 16 Nxe6+ fxe6 17 Nc3 and White’s two

bishops give him the edge in the endgame.

10 Nf3 a4?!

Extravagant! Correct is 10 ... 0-0 11 Ng5 h6 12 Nge4 Ba7 13 0-0 when Black

stays in the game, though White is somewhat better all across the board, with kingside

chances and knight leaps to b5 and d5.

11 Bd2?!

Kramnik misses his chance! 11 Ng5! would give White a tremendous attack and

close to a winning advantage. Black can’t play either ... h7-h6 or ... f7-f6, can’t castle,

and White can many times just take on h7 as his attack is worth more than the pin.

11 ... 0-0 12 Ne4

Now 12 Ng5 is too slow in view of 12 ... h6 13 Nge4 (not 13 Nxf7 Qh4+ 14

Qxh4 Nxh4 and White loses his far-flung knight) 13 ... Na5 14 0-0 Nb3 with

counterplay.

12 ... Qe8

13 0-0 -0

Simpler is 13 Nxc5 dxc5 14 0-0 (not 14 Qxc5?! Nxf4, but now White threatens

both taking the pawn as well as the central attack e3-e4) 14 ... f5 15 Rae1 Nge5 16

Qxe8 Nxf3+ 17 Rxf3 Rxe8 18 e4 with an endgame advantage; yes, Black has d4, but

White has the two bishops and the better pawn majority.

13 ... f5 14 Nxc5 dxc5 15 Kb1

White avoids 15 e4? Nxf4! picking off a pawn.

11

15 ... Nge7 16 Qh4

White tries for too much: again simpler is 16 Qxe8 Rxe8 17 Bc3 Bd7 18 Rhe1

Rad8 19 Bc2 Be6 20 Rxd8 Rxd8 21 Nd2 Ra8 22 e4 with a long-term advantage once

again due to his two bishops and superior pawn structure.

16 ... h6 17 Bc3 Be6 18 Rhg1 Rd8 19 Ka1 Rxd3! 20 Rxd3 Bxc4

White has just missed too many chances for advantage; now it’s Black’s turn, and

he’s not going to miss anything!

21 Bxg7

Kramnik tries for confusion, since Black is fine after 21 Rd2 Nd5.

21 ... Kxg7

The rook is immune: 21 ... Bxd3? 22 Qxh6 with a winning attack.

22 g4 Ng6!

Mamedyarov again shows restraint and refuses to be tempted by the poisoned

rook—if 22 ... Bxd3? something like the following variation would occur: 23 gxf5+

Kf7 24 Qh5+ Kf6 25 Qxh6+ Kxf5 26 Nh4+ Ke4 27 Qe6+ Ne5 28 Qxe5 mate.

23 gxf5 Rxf5 24 Rc3 Bf7 25 Qf2

12

Black has two pieces for a rook and a good position, and now begins the counter-

attack.

25 ... Qe6 26 b3 axb3 27 Nh4 Rh5 28 Kb2

White gets nowhere with 28 f5 Qf6 29 Nxg6 Qxc3+ 30 Kb1 Bxg6 31 Rxg6+

Kh7, when Black wins with his extra piece.

28 ... Qf6 29 Nxg6 Bxg6 30 e4 c4 31 Qd2

31 f5 doesn’t work here either—one sees the tactics favouring Black who simply

has more pieces to give, as the following variation shows: 31 ... Ne5 32 Kb1 Kh8 33

Rcg3 Rxf5 34 exf5 Bxf5+ 35 Kc1 Nd3+ 36 Rxd3 cxd3 and Black emerges with three

pawns for the exchange and a winning attack.

31 ... Qd4 32 Qxd4+ Nxd4 33 Rcg3

White loses simply after 33 Rxc4 Rxh2, and he still can’t make the critical 33 f5

work: Black wins with 33 ... Rxh2+ 34 Ka1 (or 34 Kb1 Nb5 and the knight comes in

with check) 34 ... Nb5 35 Rxg6+ Kh7 36 Rcg3 Ra2+ 37 Kb1 Nxa3+ 38 Kc1 b2+ wins

as Black queens with check.

33 ... Rxh2+ 34 Kb1 Kf7 35 Rxg6 c3

13

The connected pawns are decisive as White has no perpetual.

36 Rg7+ Ke8 37 R7g2

If 37 Rg8+ Kd7 38 R1g7+ Kc6 39 Rg6+ Kb5 40 Rg2 Rxg2 41 Rxg2 Nf3 and

Black will win the coming king and pawn ending as in the game; note that the black

king is still in the square of White’s f-pawn, and the fact that Black has a passed h-

pawn is crucial.

37 ... Rxg2 38 Rxg2 Nf3!

Black forces the aforementioned winning king and pawn ending.

39 Kc1 Nd2 0-1

After 40 Rxd2 cxd2+ 41 Kxd2 b2 42 Kc2 h5 the white king is outside the square,

while the black king handles White’s connected passed pawns.

Back to our opening question: How did the World Champion lose to the

Budapest Gambit? The answer lies not in the opening, but in the middlegame. The

Budapest certainly didn’t fare well in this game: Kramnik was clearly well prepared,

and played more accurately than Black in the early going—in fact he was on the verge

of a win, had he played 11 Ng5!.

After this he refused to take on a couple of nice +/= positions, and finally gave

Black chances—who seized them with both hands and played extremely well from

move 19 onwards.

So remember, this opening book may help you get a good opening—but you’re

going to have to win the game yourself!

Game 2

I.Odesskij-V.Kramnik

Samtredia 1987

Now we see Kramnik on the winning side, and my question is, “Why didn’t Kramnik

14

play the Budapest Gambit against Anand in their recent World Championship match?”

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 Nf3 Bc5

This is the most common move in the position, but I don’t recommend it—my

preference is for 4 ... Nc6. Find out why in Chapters 10 and 11.

On the other hand, I have to say 4 ... Bc5 can be deadly against an opponent

unprepared for the BG.

5 e3 Nc6 6 Nc3 0-0 7 Be2 Ngxe5 8 0-0 Nxf3+ 9 Bxf3 Ne5 10 Be2 Re8 11 b3

As I will show in Chapter 12, the best way for White to fight for the advantage is

f2-f4 here or after Kh1, as now Black is able to bring in another attacker ...

11 ... a5 12 Bb2 Ra6

And here it is! The “crazy rook” begins its journey.

13 Qd5 Ba7 14 Ne4 Rae6 15 Ng3 d6 16 Qxa5

Kramnik scores with a deflecting pawn sacrifice. While White’s queen is off

pawn munching, Vlad throws everything at the white king.

16 ... Bb6 17 Qc3 Rh6 18 Rfd1 Qh4 19 Nf1 Rg6 20 b4 Bg4 21 Bxg4 Rxg4

15

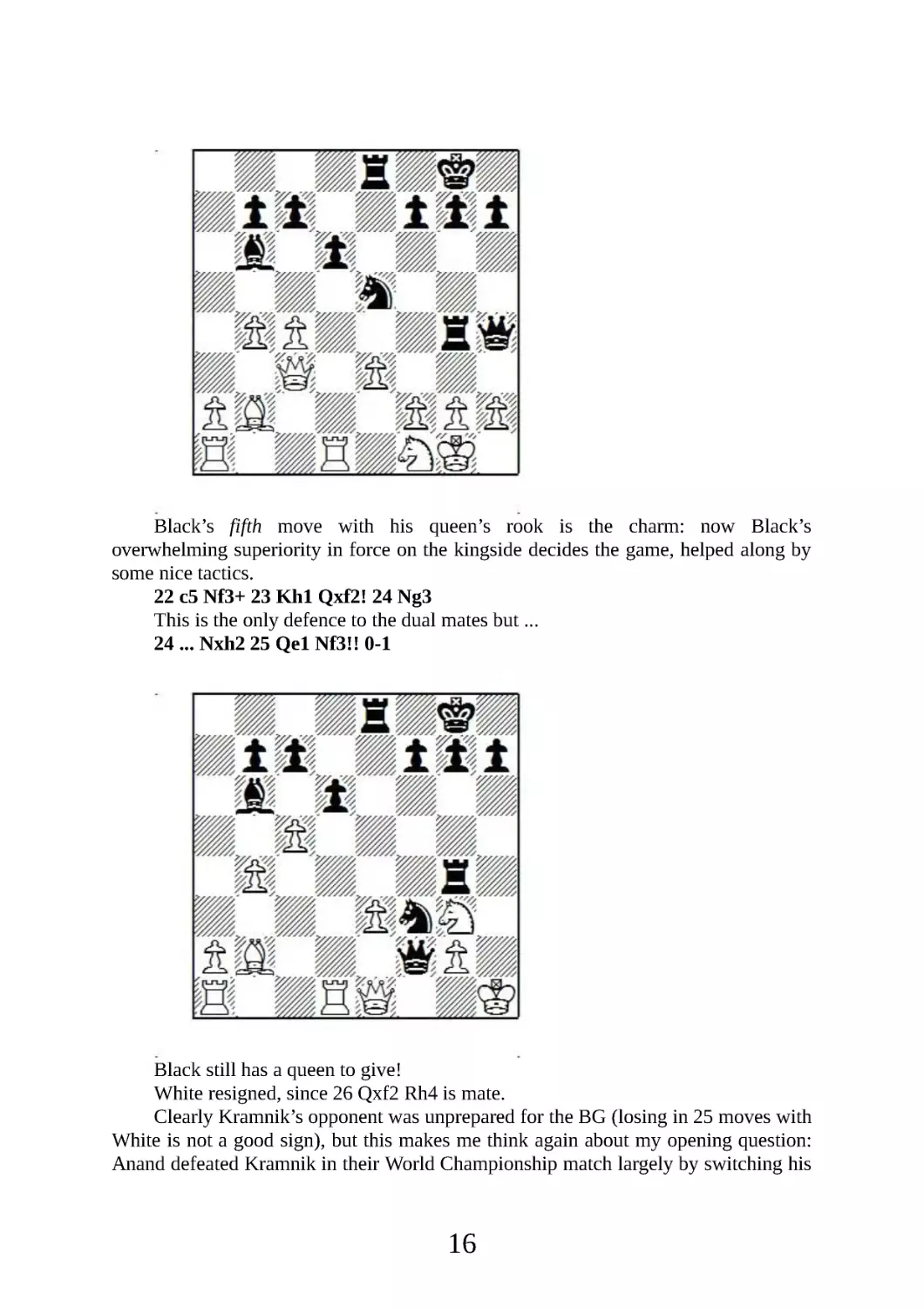

Black’s fifth move with his queen’s rook is the charm: now Black’s

overwhelming superiority in force on the kingside decides the game, helped along by

some nice tactics.

22 c5 Nf3+ 23 Kh1 Qxf2! 24 Ng3

This is the only defence to the dual mates but ...

24 ... Nxh2 25 Qe1 Nf3!! 0-1

Black still has a queen to give!

White resigned, since 26 Qxf2 Rh4 is mate.

Clearly Kramnik’s opponent was unprepared for the BG (losing in 25 moves with

White is not a good sign), but this makes me think again about my opening question:

Anand defeated Kramnik in their World Championship match largely by switching his

16

repertoire from 1 e4 to 1 d4. Would Anand have prepared deeply for the BG? I doubt

it! Imagine how a crushing victory like this would have raised Kramnik’s spirits! I

think Kramnik should have risked the Gambit, and maybe then he would still be World

Champion.

Game 3

M.Jayson-T.Taylor

Los Angeles (rapid) 2005

The following was the last tournament game in which I reached the Budapest Gambit

as Black (by which I mean 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5—note that when White declines

the gambit, one gets a different opening altogether). I’ve used this short win to explain

the layout of the book in an informal manner.

The book is divided into four parts, each of which has at least two chapters. The

first three parts deal with important variations of the BG Accepted, where White

makes a serious attempt at an opening advantage, starting with 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 de5

Ng4 and now: Part I: 4 e4. Part II: 4 Bf4. Part III: 4 Nf3. Part IV deals with lesser

deviations for White, and Black’s offbeat try, the Fajarowicz Gambit.

By the way, whenever I refer to “the Mega” or “Megabase” I refer to the

Chessbase Megabase 2008 database. I have continuously updated the games, so this

book is current through March 2009. I have also supplemented this main database with

MegaCorr4 (ChessMail) and Correspondence Database 2006 (Chessbase). Finally, my

chess engine is Fritz 11.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4

The Trompowsky shouldn’t surprise anyone these days, and if White plays 2 Nf3,

he can’t play the sharpest lines against virtually any Black opening: no Four Pawns

Attack or Sämisch against the King’s Indian, can’t play the Knesevic or main line

exchange vs. the Grünfeld, can’t fight the Nimzo-Indian with Anand’s f2-f3 or

Rubinstein’s Ng1-e2, and can only reach a weaker line of the QGD exchange!

But I will leave it to John Cox to explain such deviations—we now proceed to

the subject of this book: Black strikes boldly in the centre and the Budapest Gambit is

on the board!

2 ... e5! 3 dxe5

Declining the Gambit with moves like 3 e3 or 3 Nf3 shouldn’t cause the well-

prepared BG player any problems—these modest alternatives are covered in Chapter

14.

3 ... Ng4

17

The true Budapest Gambit: Black threatens to take back on e5, and the knight

also eyes f2.

Very risky is 3 ... Ne4, the Fajarowicz Gambit. I don’t view this as a Budapest

Gambit at all—it’s really a completely different animal—and I don’t recommend it.

Nonetheless, for reasons of completeness, I give brief coverage in Part IV, Chapter 15.

4 Bf4

This important main line is covered in Part II, Chapters 6-9 . Two critical

alternatives are 4 e4, the Alekhine Attack (Part I, Chapters 1-5) and 4 Nf3 (Chapters

10-11). As mentioned in Game 1, the quiet but reasonable tries, 4 e3, 4 Nh3, 4 Nc3

will be discussed in Chapter 12. The not so reasonable tries 4 Qd4, 4 Qd5, 4 f4, where

White tries to hang onto the gambit pawn no matter what, will be defenestrated in

Chapter 13.

4 ... Nc6

4 ... g5 is the sharp and risky alternative: see Chapter 6. Over-ambitious gambit

play such as 4 ... Bb4+ 5 Nd2 d6 will be covered in Chapter 8.

5 Nf3 Bb4+ 6 Nbd2

6 Nc3 tries to hold onto the pawn: see Chapter 7.

6 ... Qe7

This basic Budapest Gambit tabiya will be extensively covered in Chapter 9.

7 a3 Ngxe5 8 axb4

The slightly superior alternative 8 e3 will be examined in Games 59-61.

8 ... Nd3 mate

18

Here is every Budapest Gambiteer ’s dream: Mate in Eight!

Now that the pathways are marked, let’s go explore the Budapest Gambit—and I

promise, the rest of the games will be a little longer!

Timothy Taylor,

Los Angeles,

July 2009

19

Part One

The Alekhine Attack (4 e4)

The Alekhine Attack was actually invented by the attacking genius Rudolf

Spielmann in the following game:

R.Spielmann-R.Réti

1st matchgame, Berlin 1919

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5 (after being hammered so ferociously here,

Réti realized he had to find a brake to slow down White’s attack—and he did, with 4

... h5!—see Chapter 5) 5 f4 Ng6 6 Be3 Bd6 7 Qd2 Qe7 8 Nc3 Bb4 9 Bd3 b6 10 Nge2

Bb7 11 Ng3 0-0 12 h4 Qd8 13 h5 Ne7 14 a3 Bc5 15 0-0 -0 d6 16 Bc2 Nd7 17 Qd3

Bxe3+ 18 Qxe3 f6 19 e5

19 ... fxe5 20 Qd3 Nf6 21 Nce4 Bxe4 22 Nxe4 Nxe4 23 Qxe4 Rxf4 24 Qxh7+

Kf7 25 Rdf1 Qh8 26 Rxf4+ exf4 27 Qe4 Re8 28 Qxf4+ Kg8 29 h6 g6 30 h7+ Kg7 31

Rf1 1-0

Alekhine then refined the system further, and it became a still more lethal

weapon in his hands. Chapter 1 gives all six of Alekhine’s tournament games with the

Budapest (five with White and one where he faced his own system as Black).

Chapter 2 features attempts by Black to avoid the main lines of the attack by

sacrificing material or tossing in ... Bb4+. As one will see, these tries don’t fare too

well.

Chapters 3 and 4 cover what most books call the main line of the Alekhine

Attack: 4 e4 Nxe5 5 f4 and now 5 ... Ng6 is Chapter 3 and 5 ... Nec6 is Chapter 4.

While these lines are very popular, I doubt you will want to play them as Black after

you get a good look at White’s attacking chances!

20

Chapter 5 covers what I consider to be the best defence to the Alekhine Attack,

namely Réti’s improvement, 4 ... h5!.

21

Chapter One

The Alekhine Attack as Played by Alekhine

If you can get through the following games without flinching, then you have the right

stuff to be a Budapest Gambiteer!

Game 4

A.Alekhine-M.Euwe

Amsterdam 1921

This is described in the Megabase as a “free game” and while I don’t know exactly

what that means, by the play it appears to be a casual encounter rather than a

tournament game. Alekhine plays inaccurately, then tries to blow his opponent off the

board—while Euwe sacs with wild abandon!

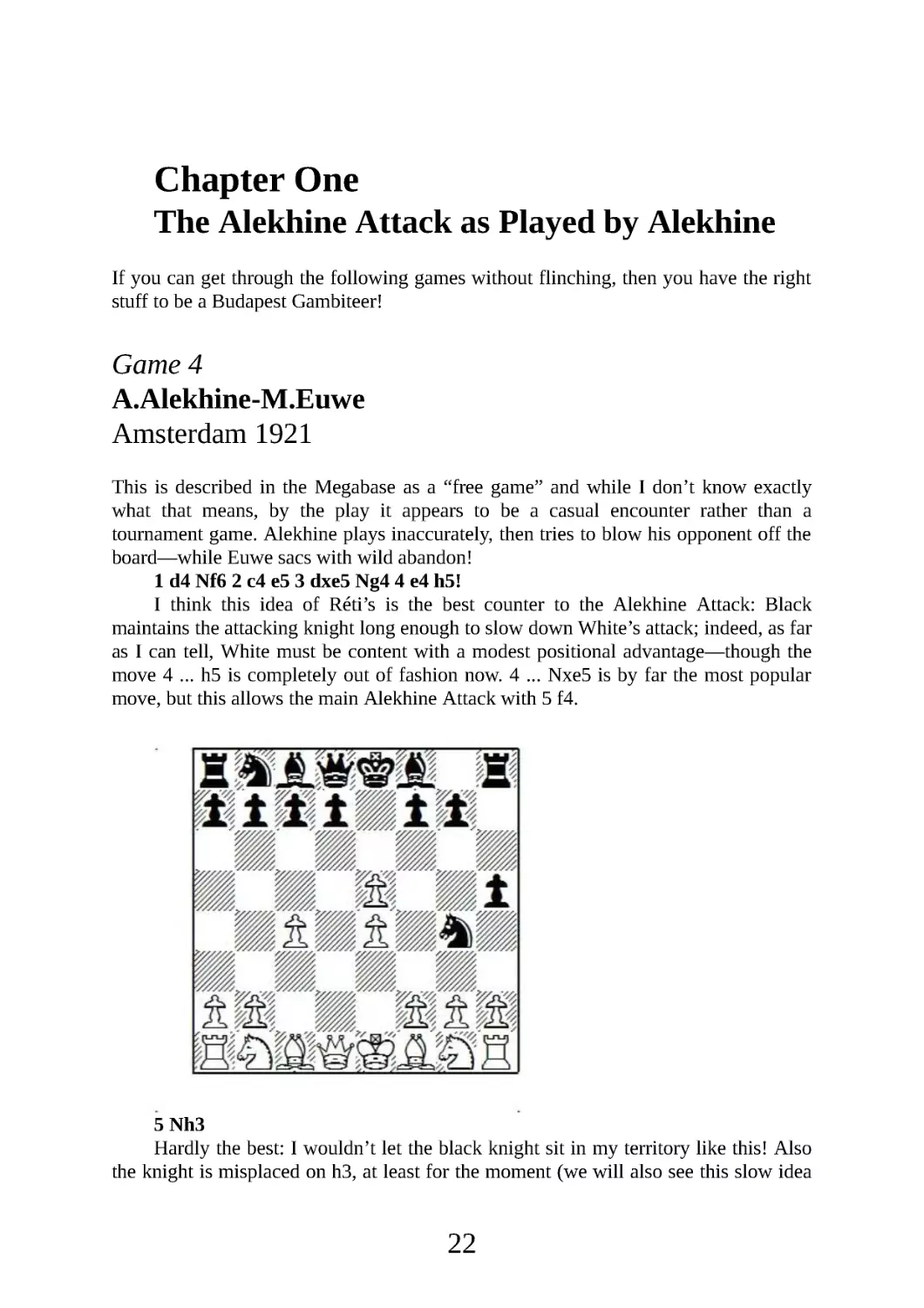

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 h5!

I think this idea of Réti’s is the best counter to the Alekhine Attack: Black

maintains the attacking knight long enough to slow down White’s attack; indeed, as far

as I can tell, White must be content with a modest positional advantage—though the

move 4 ... h5 is completely out of fashion now. 4 ... Nxe5 is by far the most popular

move, but this allows the main Alekhine Attack with 5 f4.

5 Nh3

Hardly the best: I wouldn’t let the black knight sit in my territory like this! Also

the knight is misplaced on h3, at least for the moment (we will also see this slow idea

22

— White dreams of Nh3-f4-d5—in Chapter 12, but it’s no more effective there). I

recommend that one follow Petrosian (Game 29) and kick the black knight

immediately with 5 h3.

Note that the seemingly normal 5 Nf3?! is even worse, as Black answers 5 ...

Bc5!. Now White must desperately seek a draw, which shows the danger of leaving

the black knight in its advanced position. 6 Bg5 (weaker is 6 e6 Qf6 7 exf7+ and now,

instead of 7 ... Kf8 8 Qd5 Bxf2+ 9 Ke2 Nc6 10 h3 Be3 with a very unclear position

which was eventually drawn in H.Hohensee-K .Richter, Berlin 1928, Black should

have played the simple 7 ... Qxf7, recovering his pawn with some advantage) 6 ...

Bxf2+ 7 Ke2 f6 8 exf6 gxf6 9 h3 fxg5 10 hxg4 Bb6 11 Rxh5 Rxh5 and now not 12

gxh5 g4 with advantage to Black, but 12 Qd5!!, after which Fritz sees a draw by

perpetual check, but I see a lot of anxiety before making a miserable draw!

5 ... Nc6

For 5 ... Nxe5 see Game 25, Euwe-Spielmann—there Euwe loses on the White

side of this opening!

6 Nc3 Bc5

23

7 Nd5

7 Be2 looks best but is too slow now to get an advantage as the attacking knight

stays in place: 7 ... Ncxe5! (7 ... Ngxe5 takes the pressure off f2 so White can

successfully reposition with 8 Nf4) when none of White’s three tries trouble Black:

a) 8 Na4 (trying to shake off the pressure of Black’s three active minor pieces) 8

. .. Bb4+ 9 Bd2 Bxd2+ 10 Qxd2 d6 11 Nf4 0-0 12 Nxh5 Be6 13 b3 Qh4 14 Ng3 f5 with

a double-edged game where Black has compensation for the pawn; one could imagine

15 Bxg4 Nxg4 16 h3 Ne5 17 exf5 Bxf5 18 Nxf5 Rxf5 19 0-0 Nf3+ 20 gxf3 Rg5+ 21

Kh2 Rh5 with a winning attack for Black.

b) 8 0-0 a5 9 Ng5 Qf6 10 Nd5 Qd6 11 h3 f6! with a wildly double-edged game

where Black’s attacking chances should not be underestimated—note Black has threats

to h2 as well as f2.

c) 8 f4 Qh4+ and now, because of the bad knight on h3, 9 g3 is impossible, so

White must move his king: 9 Kf1 Nc6 10 Nd5 0-0 11 Nxc7 Rb8 and Black has good

compensation for the pawn.

7 ... Ncxe5 8 b4

24

Impetuous—White is overextended and has only one piece not on the edge of the

board, and that one can be kicked back!

8 ... Be7?

With the correct move Black could get the advantage, but now White exchanges

off the e7-bishop, activates his own dark-squared bishop on the long diagonal (where

it has no opponent) stops Black’s counter-attack, and so on ...

Best is 8 ... Bf8! after which ... c7-c6, driving back White’s only good piece, is

coming. Here are a few variations:

a) 9 f4 c6 10 fxe5 cxd5 and Black is better in view of the attacks on e4 and b4.

b) 9 f3 c6 10 fxg4 (10 Ne3? Bxb4+ wins for Black) 10 ... cxd5 with an attack

against b4 and g4.

c) 9 a3 c6 10 Ne3 Qf6 11 Ra2 a5 and White’s overextended pawn structure

collapses.

9 Bb2 c6 10 Nxe7 Qxe7 11 c5

What a difference a few moves make! Now White’s dark square bind (in the

absence of the Black’s dark-squared bishop) is virtually decisive.

11 ... a5 12 Qd4

White threatens to win a piece, so Black “sacrifices” it—but the alternative 12 ...

Ng6 13 f3 Nf6 14 b5 would have been positionally dreadful.

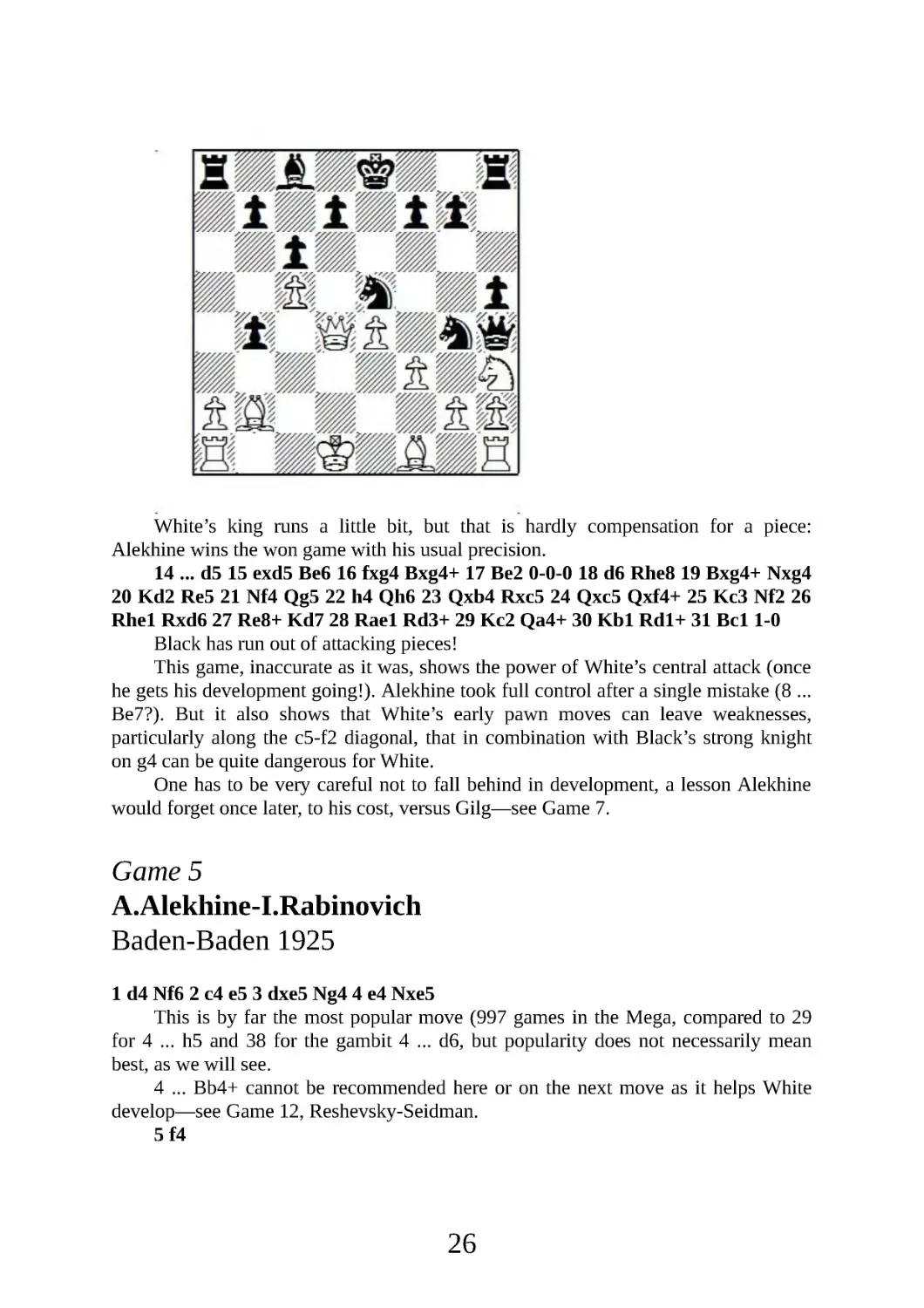

12 ... axb4 13 f3 Qh4+ 14 Kd1

25

White’s king runs a little bit, but that is hardly compensation for a piece:

Alekhine wins the won game with his usual precision.

14 ... d5 15 exd5 Be6 16 fxg4 Bxg4+ 17 Be2 0-0 -0 18 d6 Rhe8 19 Bxg4+ Nxg4

20 Kd2 Re5 21 Nf4 Qg5 22 h4 Qh6 23 Qxb4 Rxc5 24 Qxc5 Qxf4+ 25 Kc3 Nf2 26

Rhe1 Rxd6 27 Re8+ Kd7 28 Rae1 Rd3+ 29 Kc2 Qa4+ 30 Kb1 Rd1+ 31 Bc1 1-0

Black has run out of attacking pieces!

This game, inaccurate as it was, shows the power of White’s central attack (once

he gets his development going!). Alekhine took full control after a single mistake (8 ...

Be7?). But it also shows that White’s early pawn moves can leave weaknesses,

particularly along the c5-f2 diagonal, that in combination with Black’s strong knight

on g4 can be quite dangerous for White.

One has to be very careful not to fall behind in development, a lesson Alekhine

would forget once later, to his cost, versus Gilg—see Game 7.

Game 5

A.Alekhine-I.Rabinovich

Baden-Baden 1925

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5

This is by far the most popular move (997 games in the Mega, compared to 29

for 4 ... h5 and 38 for the gambit 4 ... d6, but popularity does not necessarily mean

best, as we will see.

4 ... Bb4+ cannot be recommended here or on the next move as it helps White

develop—see Game 12, Reshevsky-Seidman.

5 f4

26

The basic tabiya of the Alekhine Attack. Black now has a choice: 5 ... Ng6, as

played here, does not get in the way of the other pieces, but the knight is vulnerable to

the f4-f5 attack. The knight is safer on c6, but it blocks the natural developing square

for the b8-knight. Which one is better? Grandmaster annotators can become confused;

take a look at these duelling quotes from Jonathan Tisdall, an American GM who now

plays for Norway.

Analyzing the 1991 game between Mikhalchishin and Lendwai (Game 14 in this

book) Tisdall writes about 5 ... Ng6: “Lalic hints that this may be better than the

popular retreat to c6, and I have a feeling he is right. That line has a tendency to lead

to a traffic jam of Black’s minor pieces on the queenside. The line with a knight on g6

creates pressure against the f4-pawn. On a bad day, the Ng6 will get kicked around as

White mounts an attack, but we should be able to avoid that if we keep the possibility

in mind.”

Sounds good, but now we have Tisdall annotating the game Bacrot-Shirov from

2000 (this game is given in the notes to Game 23, Spirin-Kravchenko)—here he extols

5 ... Nc6: “A contentious decision, but this is probably better than 5 ... Ng6.”(!)

My feeling is that Black is in trouble already, no matter where he puts the knight.

I think the only good path for Black is the uncompromising 4 ... h5, as seen in the

previous game and fully analyzed in Games 25-29.

5 ... Ng6

For the unlucky sacrifices 5 ... Nbc6 and 5 ... Bc5 see the properly numbered

Game 13.

6 Nf3

I will cover the alternative 6 Be3 in Games 14 and 15.

6 ... Bc5

This logical-looking move, taking over the a7-g1 diagonal, is no longer played at

a high level as a result of the current game: I will fully analyze the modern alternative

6 ... Bb4+ in Games 16 and 17.

7 f5!

27

Alekhine awards himself this well-deserved exclam—Black is already in trouble

on move 7! Note that Alekhine brilliantly refutes his opponent’s seemingly sound

positional play by moving his f-pawn twice and his king’s knight twice in the opening

—no DDT for him! (You’ll get this joke if you read my previous book, True Combat

Chess.)

7 ... Nh4

Black is very cramped after the alternative 7 ... Ne7. According to the Megabase,

White has scored seven wins and only one draw from this position, e.g . 8 Nc3 d6 9

Na4 Bb4+ 10 Kf2 Nd7 11 a3 Bc5+ 12 Nxc5 Nxc5 13 Bd3 Nxd3+ 14 Qxd3 0-0 15 b4

Nc6 16 Bb2 Qe7 17 Rad1 Ne5 18 Bxe5 dxe5 19 Qd5 Re8 20 Rd3 c6 21 Qd6 Qxd6 22

Rxd6 f6 23 Rhd1 Kf7 24 g4 h6 25 h4 a5 26 b5 cxb5 27 cxb5 a4 28 g5 Ra5 29 Rb6

Ke7 30 gxf6+ gxf6 31 Rg1 Rf8 32 Nd2 Ra7 33 Nc4 Bd7 34 Ne3 Kd8 35 Rg7 Kc8 36

Nd5 Ra5 37 Ke3 Rxb5 38 Rxd7 Rxb6 39 Nxb6+ Kb8 1-0 I.Ivanov-G .Bendana

Guerrero, Boston 1988—a powerful win by the late American GM.

8 Ng5!

The second anti-positional move—but now Black’s divagating knight has no

moves that don’t allow capture, while White is threatening the double attack Qh5.

8 ... Qe7

If Black plays 8 ... h6, White won’t retreat: 9 Qh5! 0-0 10 Qxh4 Be7 11 Nc3 Re8

12 Qg4 Bxg5 13 Bxg5 hxg5 14 0-0 -0 Na6 15 h4 gxh4 16 Rxh4 b6 17 Be2 Bb7 18 Bf3

Re5 and now 19 Rdh1 would have won in C.Santos-M .Munoz Sanchez, Bled

Olympiad 2002.

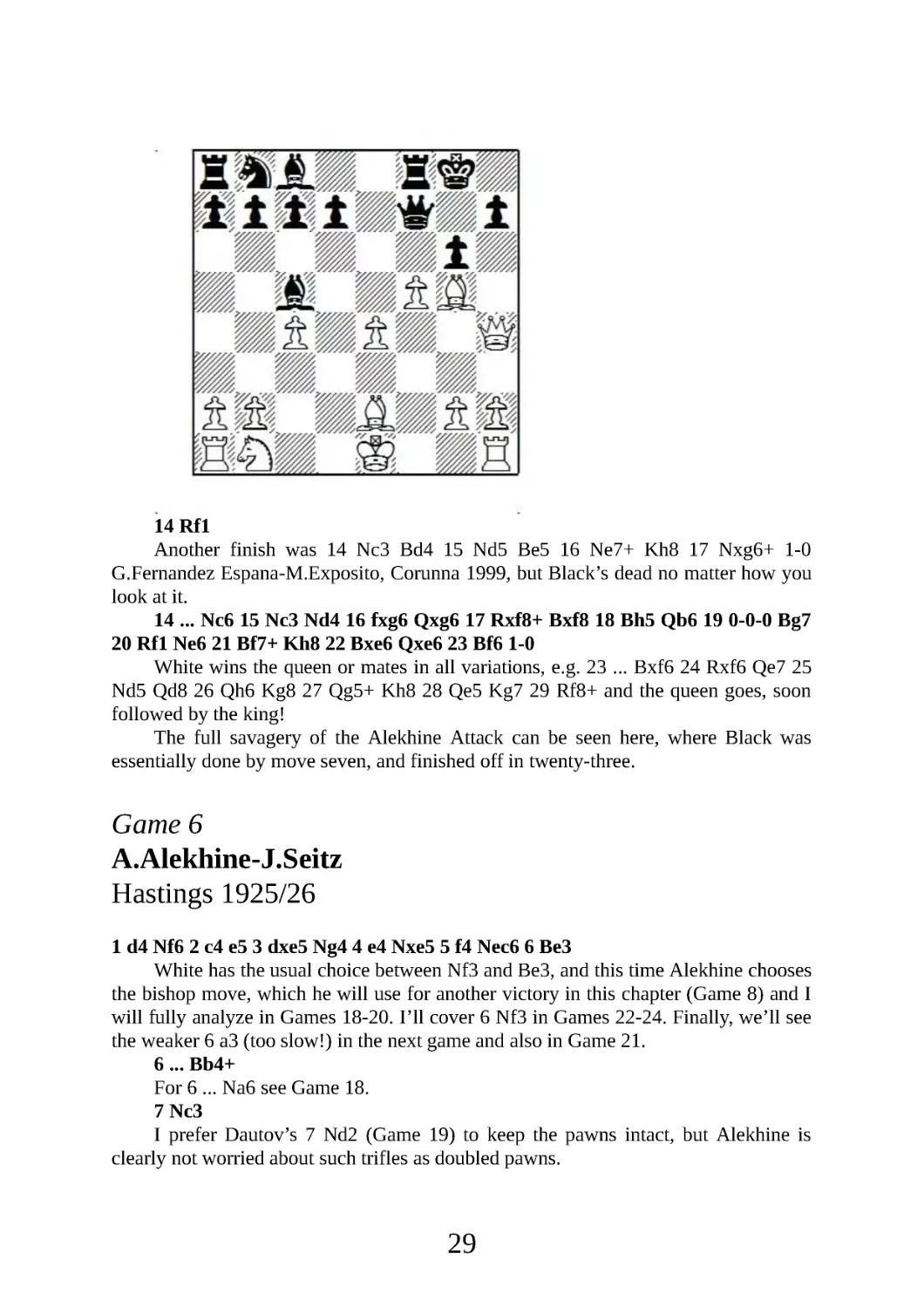

9 Qg4 f6 10 Qh5+ g6 11 Qxh4 fxg5 12 Bxg5 Qf7 13 Be2 0-0

28

14 Rf1

Another finish was 14 Nc3 Bd4 15 Nd5 Be5 16 Ne7+ Kh8 17 Nxg6+ 1-0

G.Fernandez Espana-M .Exposito, Corunna 1999, but Black’s dead no matter how you

look at it.

14 ... Nc6 15 Nc3 Nd4 16 fxg6 Qxg6 17 Rxf8+ Bxf8 18 Bh5 Qb6 19 0-0 -0 Bg7

20 Rf1 Ne6 21 Bf7+ Kh8 22 Bxe6 Qxe6 23 Bf6 1-0

White wins the queen or mates in all variations, e.g . 23 ... Bxf6 24 Rxf6 Qe7 25

Nd5 Qd8 26 Qh6 Kg8 27 Qg5+ Kh8 28 Qe5 Kg7 29 Rf8+ and the queen goes, soon

followed by the king!

The full savagery of the Alekhine Attack can be seen here, where Black was

essentially done by move seven, and finished off in twenty-three.

Game 6

A.Alekhine-J.Seitz

Hastings 1925/26

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5 5 f4 Nec6 6 Be3

White has the usual choice between Nf3 and Be3, and this time Alekhine chooses

the bishop move, which he will use for another victory in this chapter (Game 8) and I

will fully analyze in Games 18-20. I’ll cover 6 Nf3 in Games 22-24 . Finally, we’ll see

the weaker 6 a3 (too slow!) in the next game and also in Game 21.

6 ... Bb4+

For 6 ... Na6 see Game 18.

7 Nc3

I prefer Dautov’s 7 Nd2 (Game 19) to keep the pawns intact, but Alekhine is

clearly not worried about such trifles as doubled pawns.

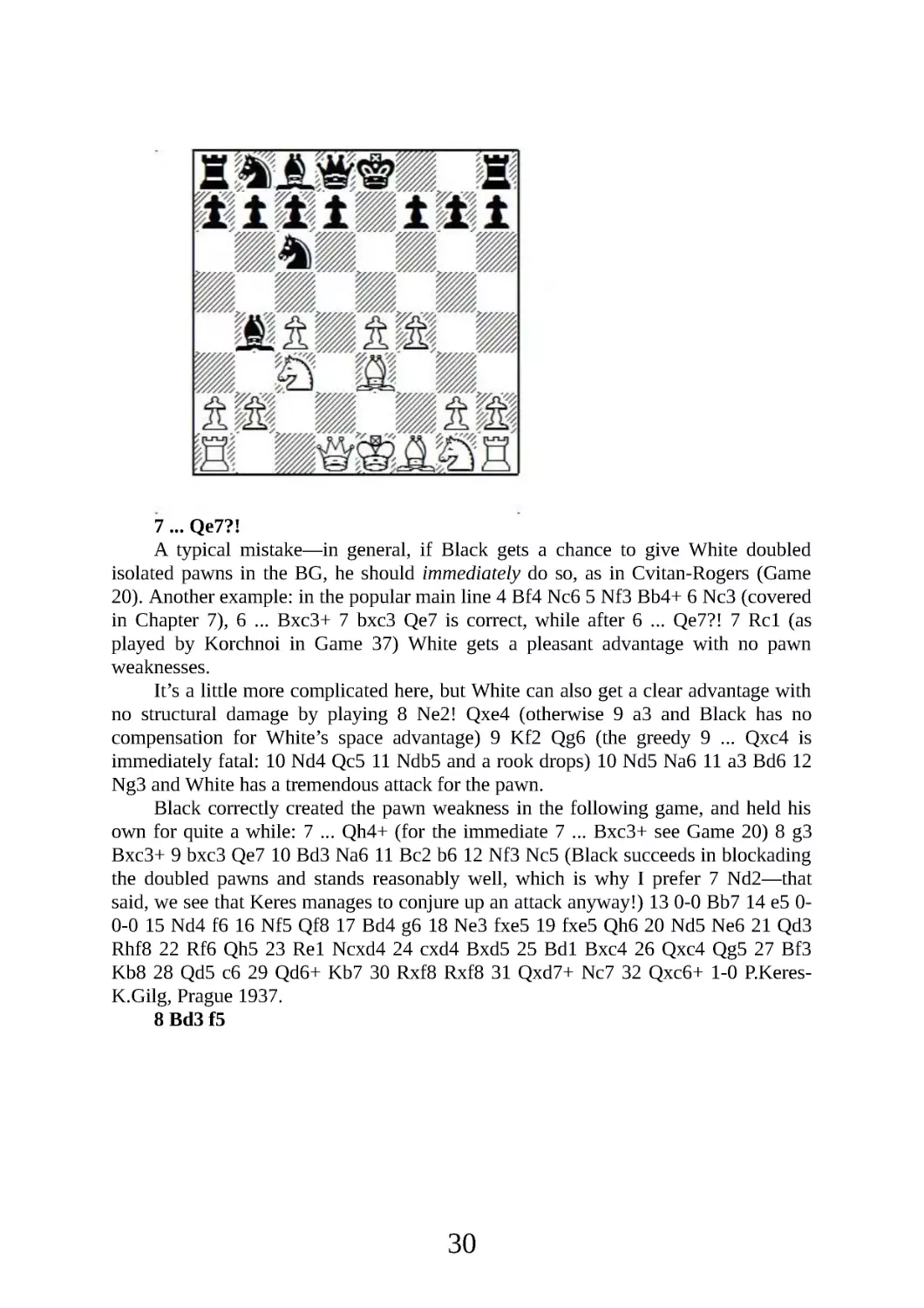

29

7 ... Qe7?!

A typical mistake—in general, if Black gets a chance to give White doubled

isolated pawns in the BG, he should immediately do so, as in Cvitan-Rogers (Game

20). Another example: in the popular main line 4 Bf4 Nc6 5 Nf3 Bb4+ 6 Nc3 (covered

in Chapter 7), 6 ... Bxc3+ 7 bxc3 Qe7 is correct, while after 6 ... Qe7?! 7 Rc1 (as

played by Korchnoi in Game 37) White gets a pleasant advantage with no pawn

weaknesses.

It’s a little more complicated here, but White can also get a clear advantage with

no structural damage by playing 8 Ne2! Qxe4 (otherwise 9 a3 and Black has no

compensation for White’s space advantage) 9 Kf2 Qg6 (the greedy 9 ... Qxc4 is

immediately fatal: 10 Nd4 Qc5 11 Ndb5 and a rook drops) 10 Nd5 Na6 11 a3 Bd6 12

Ng3 and White has a tremendous attack for the pawn.

Black correctly created the pawn weakness in the following game, and held his

own for quite a while: 7 ... Qh4+ (for the immediate 7 ... Bxc3+ see Game 20) 8 g3

Bxc3+ 9 bxc3 Qe7 10 Bd3 Na6 11 Bc2 b6 12 Nf3 Nc5 (Black succeeds in blockading

the doubled pawns and stands reasonably well, which is why I prefer 7 Nd2—that

said, we see that Keres manages to conjure up an attack anyway!) 13 0-0 Bb7 14 e5 0-

0-0 15 Nd4 f6 16 Nf5 Qf8 17 Bd4 g6 18 Ne3 fxe5 19 fxe5 Qh6 20 Nd5 Ne6 21 Qd3

Rhf8 22 Rf6 Qh5 23 Re1 Ncxd4 24 cxd4 Bxd5 25 Bd1 Bxc4 26 Qxc4 Qg5 27 Bf3

Kb8 28 Qd5 c6 29 Qd6+ Kb7 30 Rxf8 Rxf8 31 Qxd7+ Nc7 32 Qxc6+ 1-0 P.Keres-

K.Gilg, Prague 1937.

8 Bd3 f5

30

This is too risky in such an undeveloped position—since Alekhine did not cover

his knight, Black should still take it: 8 ... Bxc3+ followed by 9 ... Na6, holding c5,

looks best, similar to the Keres-Gilg game.

9 Qh5+

A typical “Grandmaster over-refinement” that helps Black block the d3-bishop.

Correct is the simple 9 Qf3 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 fxe4 11 Bxe4 with advantage, e.g . 11 ... 0-

0 (or 11 ... d6 12 Bd5 Bg4 13 Qxg4 Qxe3+ 14 Kf1 and White is practically winning

with the rook coming to e1 soon) 12 Nh3 Re8 13 Ng5 h6 14 0-0 d6 (not 14 ... hxg5?

15 Bd5+ Kh7 16 Qh5 mate, or 15 ... Kf8 16 fxg5+ and mates) 15 Bd5+ Kh8 16 Rae1

with a winning attack.

9 ... g6 10 Qf3 Bxc3+ 11 bxc3 fxe4

Much better is 11 ... d6 and Black more or less holds, because of the gift tempo ...

g7-g6 that Black got in because of 9 Qh5+. Black consolidates after 12 exf5 Bxf5 13

Bxf5 gxf5 14 Ne2 Nd7 15 0-0 0-0 -0 16 Nd4 Rde8, while if 12 Nh3 fxe4 13 Bxe4 (13

Qxe4 Bxh3 destroys the rest of White’s pawns) 13 ... Bg4 14 Qxg4 Qxe4 and Black

has counterplay—one sees that, unlike in the note to move 9, White was unable to get

his bishop to d5 here.

12 Bxe4 0-0 13 Bd5+ Kh8 14 Nh3 d6

It doesn’t help to get the queens off: 14 ... Re8 15 Kf2 Qh4+ 16 Qg3 Qxg3+ 17

hxg3, still with a winning attack.

15 0-0

31

Since Black missed his chance on move 11, we see that ... g7-g6 now shows up

as a weakness. All White needs is one check on the long diagonal and the game will be

over.

15 ... Bxh3 16 Qxh3 Qd7 17 f5!

The Bird/Four Pawns Attack blow scores again! Even Fritz jumps to plus 3!

17 ... gxf5

17 ... Rxf5 18 Qh4 Na6 19 Rxf5 gxf5 20 Bh6 Qe7 21 Bg5 and wins is a typical

variation where the dark-squared bishop finds its way to the long diagonal.

18 Rab1 f4

Trying to divert the bishop from d4, as 18 ... Na6 19 Bxc6 bxc6 20 Bd4+ Kg8 21

Qg3+ wins immediately.

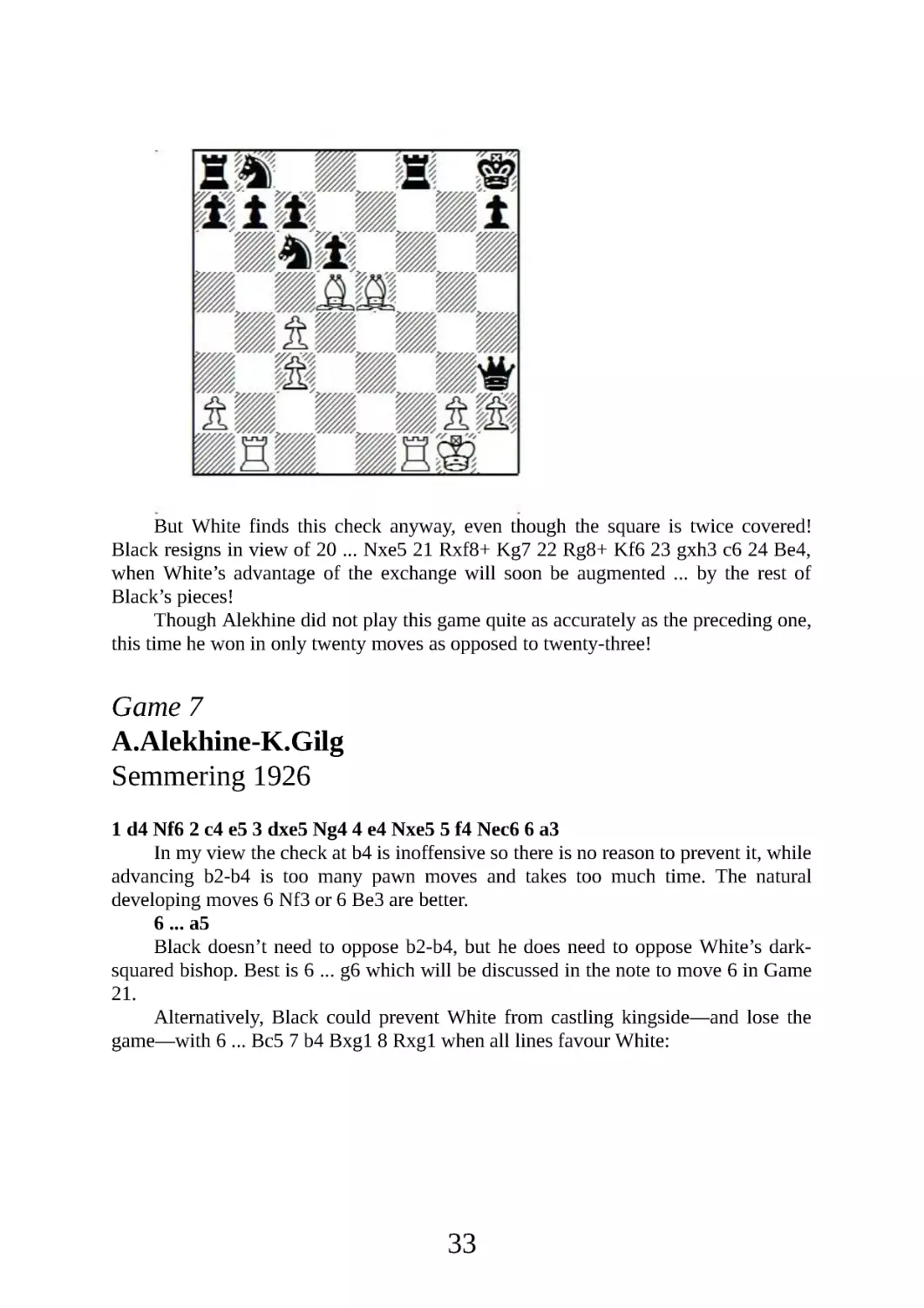

19 Bxf4 Qxh3 20 Be5+! 1-0

32

But White finds this check anyway, even though the square is twice covered!

Black resigns in view of 20 ... Nxe5 21 Rxf8+ Kg7 22 Rg8+ Kf6 23 gxh3 c6 24 Be4,

when White’s advantage of the exchange will soon be augmented ... by the rest of

Black’s pieces!

Though Alekhine did not play this game quite as accurately as the preceding one,

this time he won in only twenty moves as opposed to twenty-three!

Game 7

A.Alekhine-K.Gilg

Semmering 1926

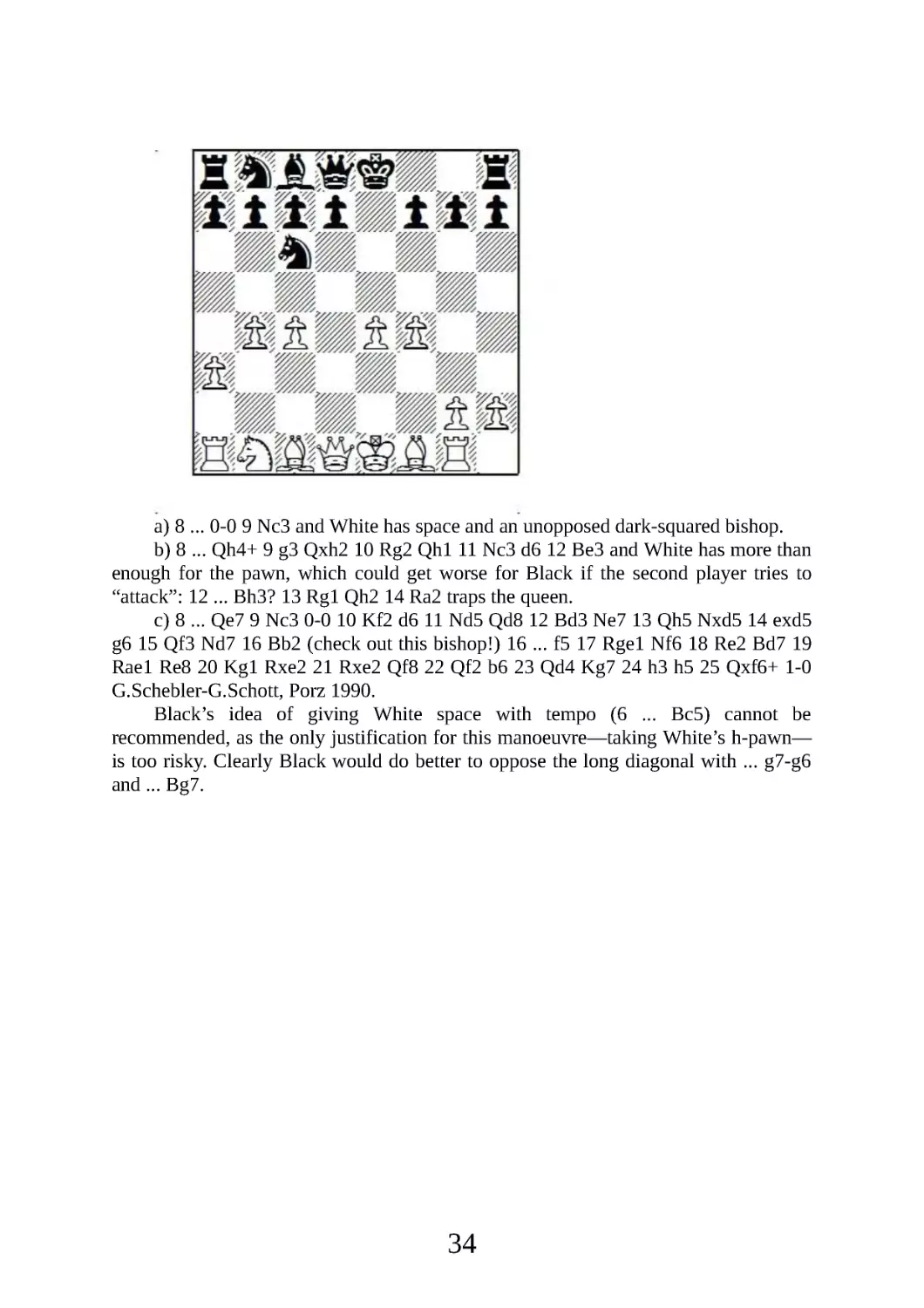

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5 5 f4 Nec6 6 a3

In my view the check at b4 is inoffensive so there is no reason to prevent it, while

advancing b2-b4 is too many pawn moves and takes too much time. The natural

developing moves 6 Nf3 or 6 Be3 are better.

6 ... a5

Black doesn’t need to oppose b2-b4, but he does need to oppose White’s dark-

squared bishop. Best is 6 ... g6 which will be discussed in the note to move 6 in Game

21.

Alternatively, Black could prevent White from castling kingside—and lose the

game—with 6 ... Bc5 7 b4 Bxg1 8 Rxg1 when all lines favour White:

33

a) 8 ... 0-0 9 Nc3 and White has space and an unopposed dark-squared bishop.

b) 8 ... Qh4+ 9 g3 Qxh2 10 Rg2 Qh1 11 Nc3 d6 12 Be3 and White has more than

enough for the pawn, which could get worse for Black if the second player tries to

“attack”: 12 ... Bh3? 13 Rg1 Qh2 14 Ra2 traps the queen.

c) 8 ... Qe7 9 Nc3 0-0 10 Kf2 d6 11 Nd5 Qd8 12 Bd3 Ne7 13 Qh5 Nxd5 14 exd5

g6 15 Qf3 Nd7 16 Bb2 (check out this bishop!) 16 ... f5 17 Rge1 Nf6 18 Re2 Bd7 19

Rae1 Re8 20 Kg1 Rxe2 21 Rxe2 Qf8 22 Qf2 b6 23 Qd4 Kg7 24 h3 h5 25 Qxf6+ 1-0

G.Schebler-G.Schott, Porz 1990.

Black’s idea of giving White space with tempo (6 ... Bc5) cannot be

recommended, as the only justification for this manoeuvre—taking White’s h-pawn—

is too risky. Clearly Black would do better to oppose the long diagonal with ... g7-g6

and ... Bg7.

34

7 Nc3 Bc5 8 Nd5

Perhaps Alekhine recalled his quick win vs. Euwe, but facing a determined

tournament competitor is not the same as a “free game!”

Better is the modest 8 Nf3 0-0 9 Bd3 as played by the Chinese GM Wang Yue, as

seen in the note to move 7 in Game 21.

8 ... 0-0 9 Bd3 d6 10 Qh5

Unlike the similar Kramnik sortie from Game 1, this move does not come with

either a threat or an attack! White has lost too much time in the opening (a2-a3, Nd5)

for such a primitive venture to succeed.

10 ... Nd7 11 Nf3 h6 12 g4?

Mr. Fritz offers the circumspect 12 Qh4 with equality, but Alekhine is determined

35

to attack at all cost—and the cost is one point—for his opponent!

12 ... Nf6 13 Nxf6+ Qxf6 14 f5 Nd4

Black’s counter-attack arrives at full speed, and our favourite chess machine says

Black already has a decisive advantage.

It is instructive to note the weaknesses caused by White’s non-essential pawn

moves: 6 a3 left a hole at b3, and 12 g4 weakened f3, and both of these are easily

targeted by Black’s powerful centralized knight.

15 g5

The great world champion runs forward to his doom.

15 ... Nxf3+ 16 Qxf3 hxg5 17 h4 Re8 18 Kd1

Or 18 hxg5 Qxf5 19 Qg3 Rxe4+ 20 Kd2 Rd4 21 Kc3 Rxd3+ 22 Qxd3 Qe5+ 23

Kb3 Bf5 with a decisive Shirovian attack.

18 ... gxh4 19 Kc2 Bd7 20 Bd2 Ra6 21 Qh5 Ba4+ 22 Kc1 Rb6 23 Ra2 Bd4 24

b4 Be3!

36

25 Bxe3 Qc3+ 26 Bc2 Qxe3+ 27 Kb1 Bxc2+ 28 Rxc2 axb4 29 Qxh4 bxa3+ 30

Ka2 Qh6 31 Qxh6

31 Qe1 Qf6 is worse, so Alekhine must go into a lost ending.

31 ... gxh6 32 Rxh6 Kg7 33 Rh4 Rb2+ 34 Rxb2 axb2 35 Kxb2

35 ... Rh8 36 f6+ Kg8 37 Rf4 Kf8 38 Kc3 Rh3+ 39 Kd2 Ke8 40 e5 dxe5 41

Rf5 Rh6 42 Rxe5+ Kd8 43 Rd5+ Kc8 44 Rf5 Kd7 45 Rd5+ Ke6 46 Rc5 c6 47 Ra5

Rh8 48 Ra7 Rb8 49 Kc3 Kxf6 50 Kb4 Ke5 51 Kc5 f5 52 Ra1 f4 53 Re1+ Kf5 54

Re7 b5 55 Kxc6 bxc4 56 Kd5 Rd8+ 57 Kxc4 f3 58 Kc3 Kf4 59 Rf7+ Kg3 60 Rg7+

Kf2 61 Rg6 Kf1 62 Rf6 f2

Black has reached the Lucena position—once Gilg demonstrates that he knows

the correct technique to win it, Alekhine resigns.

37

63 Rg6 Rd5 64 Kc2 Ke2 65 Re6+ Kf3 66 Rf6+ Ke3 67 Rf8 Rd4 0-1

Game 8

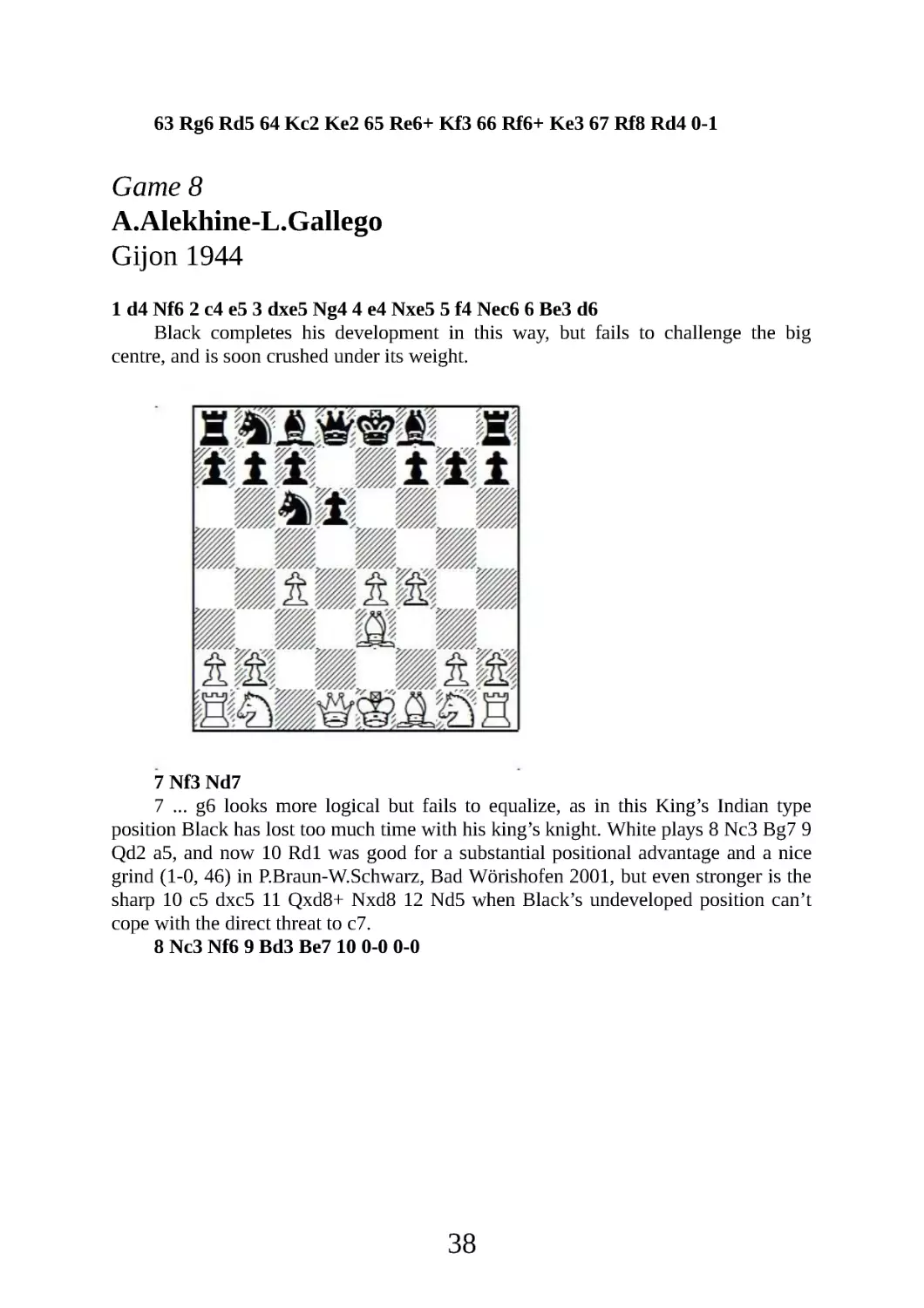

A.Alekhine-L.Gallego

Gijon 1944

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5 5 f4 Nec6 6 Be3 d6

Black completes his development in this way, but fails to challenge the big

centre, and is soon crushed under its weight.

7 Nf3 Nd7

7 ... g6 looks more logical but fails to equalize, as in this King’s Indian type

position Black has lost too much time with his king’s knight. White plays 8 Nc3 Bg7 9

Qd2 a5, and now 10 Rd1 was good for a substantial positional advantage and a nice

grind (1-0, 46) in P.Braun-W.Schwarz, Bad Wörishofen 2001, but even stronger is the

sharp 10 c5 dxc5 11 Qxd8+ Nxd8 12 Nd5 when Black’s undeveloped position can’t

cope with the direct threat to c7.

8 Nc3 Nf6 9 Bd3 Be7 10 0-0 0-0

38

Black has developed and castled and is virtually lost.

11 h3 b6 12 a3 Ne8 13 Qc2 f5

Or 13 ... g6 14 b4 a6 15 Rad1 with slow strangulation.

14 exf5 Nf6 15 g4 Bd7 16 Rae1 Rb8 17 Nd5 Nxd5 18 cxd5 Na5 19 b4 Nb7 20

Nd4 Qc8 21 Rc1 Bd8 22 Nc6

Now Black could play 22 ... Ra8 23 Nxd8 Qxd8 24 Qxc7 Rb8 and fight on two

pawns down, but instead he saves the a-pawn and ...

22 ... a5 23 Na7 1-0

Loses his queen!

Simple development won’t do against the Alekhine Attack.

39

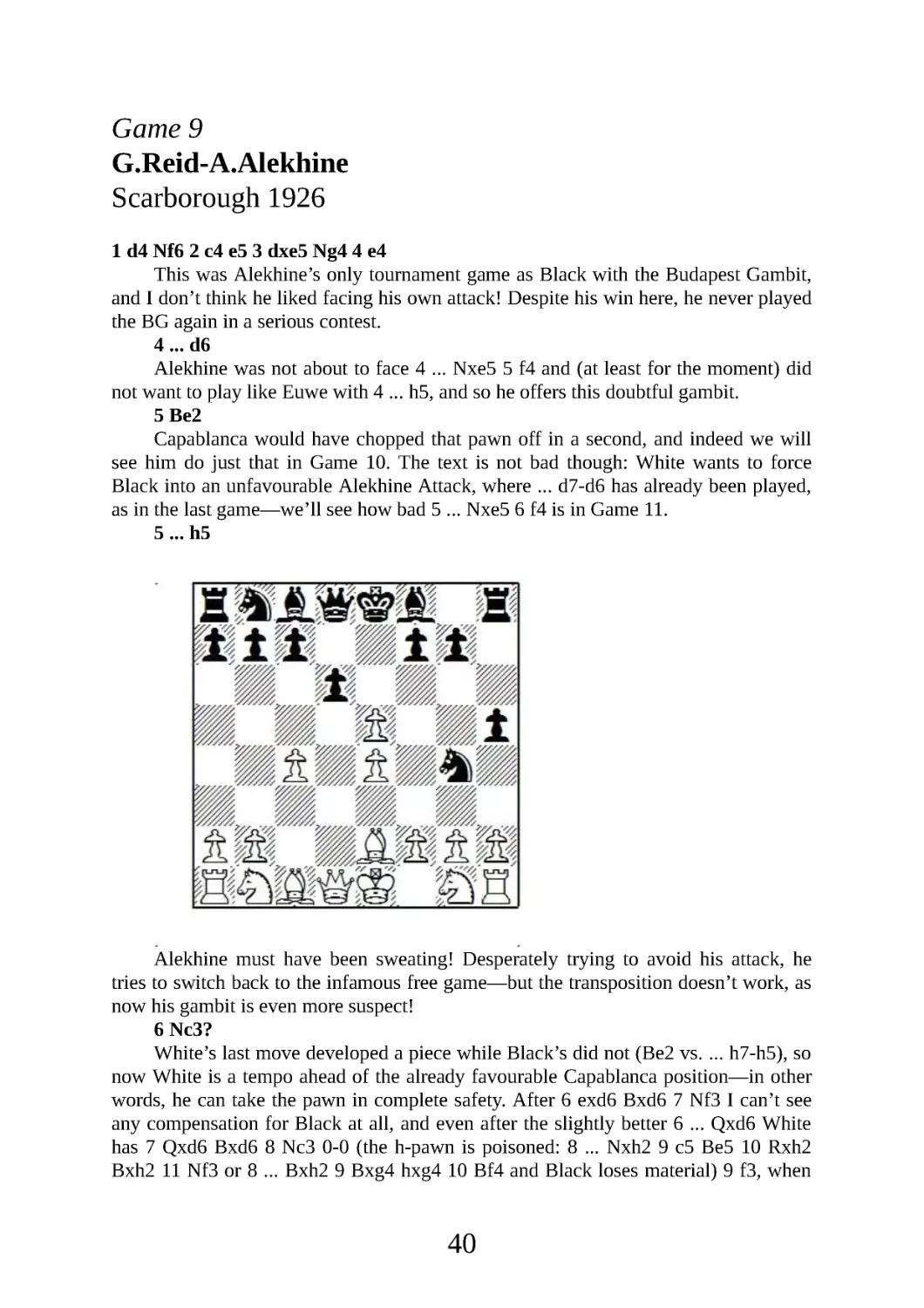

Game 9

G.Reid-A.Alekhine

Scarborough 1926

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4

This was Alekhine’s only tournament game as Black with the Budapest Gambit,

and I don’t think he liked facing his own attack! Despite his win here, he never played

the BG again in a serious contest.

4 ... d6

Alekhine was not about to face 4 ... Nxe5 5 f4 and (at least for the moment) did

not want to play like Euwe with 4 ... h5, and so he offers this doubtful gambit.

5 Be2

Capablanca would have chopped that pawn off in a second, and indeed we will

see him do just that in Game 10. The text is not bad though: White wants to force

Black into an unfavourable Alekhine Attack, where ... d7-d6 has already been played,

as in the last game—we’ll see how bad 5 ... Nxe5 6 f4 is in Game 11.

5 ... h5

Alekhine must have been sweating! Desperately trying to avoid his attack, he

tries to switch back to the infamous free game—but the transposition doesn’t work, as

now his gambit is even more suspect!

6 Nc3?

White’s last move developed a piece while Black’s did not (Be2 vs. .. . h7-h5), so

now White is a tempo ahead of the already favourable Capablanca position—in other

words, he can take the pawn in complete safety. After 6 exd6 Bxd6 7 Nf3 I can’t see

any compensation for Black at all, and even after the slightly better 6 ... Qxd6 White

has 7 Qxd6 Bxd6 8 Nc3 0-0 (the h-pawn is poisoned: 8 ... Nxh2 9 c5 Be5 10 Rxh2

Bxh2 11 Nf3 or 8 ... Bxh2 9 Bxg4 hxg4 10 Bf4 and Black loses material) 9 f3, when

40

Black has the bitter choice between trapping his own knight to get his pawn back (9 ...

Nxh2 with no exit visa) or returning to safety with 9 ... Nf6 and nothing at all for the

pawn.

6 ... Nc6 7 h3

7 exd6 is still a clear pawn, but the text is not bad if ...

7 ... Ngxe5

White follows with 8 f4!. The Alekhine Attack against Alekhine! Now if 8 ...

Ng6 White just plays 9 Nf3 with advantage, so Black is almost forced to try 8 ... Qh4+

9 Kf1

but it transpires that even here Black has no effective knight move, as can be

seen:

a) 9 ... Ng6 10 Nf3 Qf6 (or 10 ... Qg3 11 Nd5 and c7 cracks as so often in this

variation) 11 f5 Nge5 12 Bg5! wins the queen as there is no check on f3—note how

having the king on f1 actually helps White here.

b) 9 ... Ng4 10 g3 wins a piece.

c) 9 ... Nd7 10 Nf3 and one can see Black got no mileage out of the check, as

White can castle by hand: 10 ... Qd8 11 Kf2 Be7 12 Be3 with a typical Alekhine

Attack plus.

This would have been a dream position for the White player—but lacking

boldness, he played the prosaic ...

8 Nf3

And was lost in five more moves.

8 ... Nxf3+ 9 Bxf3 g6 10 Be3 Be6 11 Nd5 Ne5 12 Bd4 c6 13 Bxe5?

13 Ne3 is a much better try.

13 ... dxe5

41

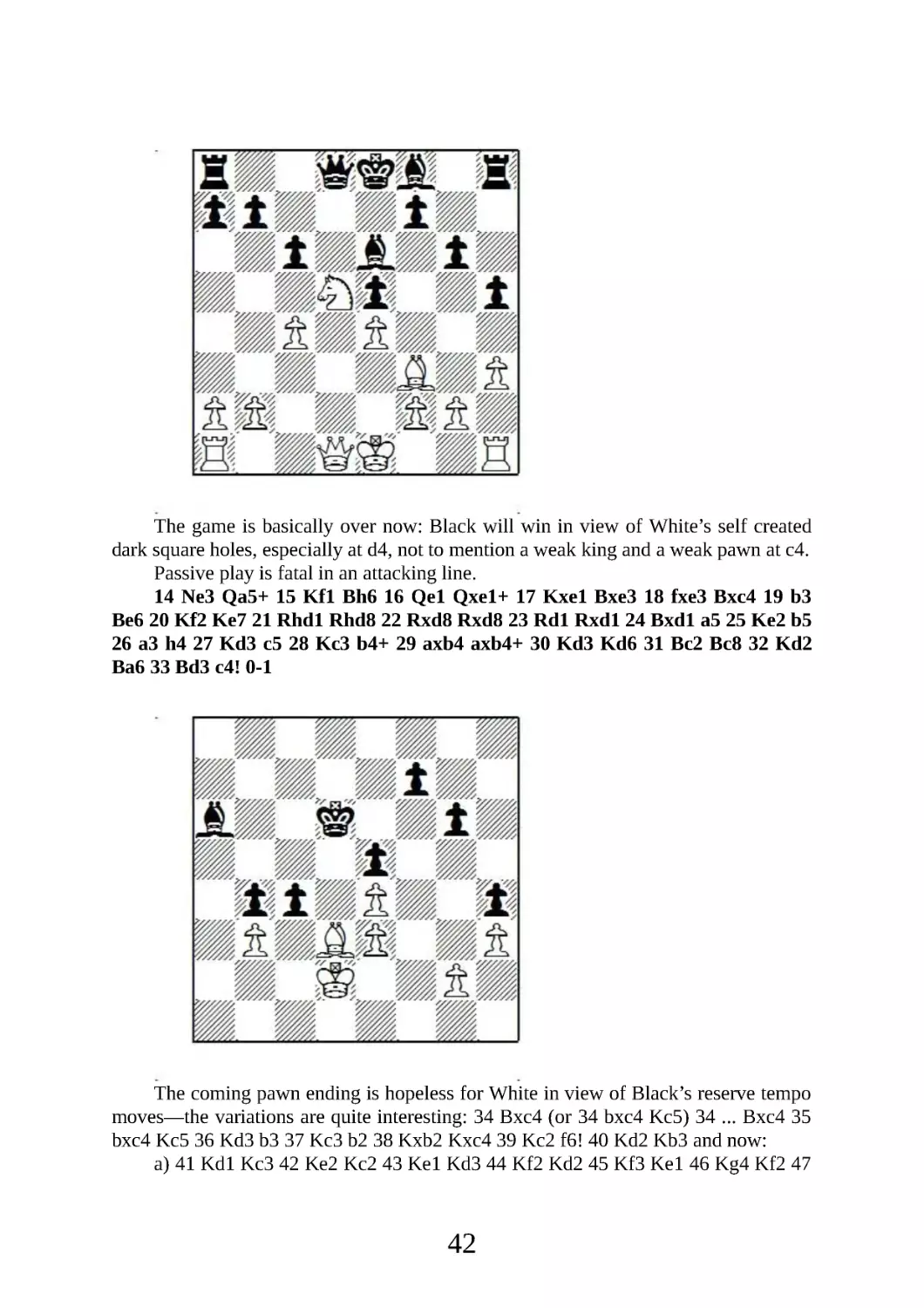

The game is basically over now: Black will win in view of White’s self created

dark square holes, especially at d4, not to mention a weak king and a weak pawn at c4.

Passive play is fatal in an attacking line.

14 Ne3 Qa5+ 15 Kf1 Bh6 16 Qe1 Qxe1+ 17 Kxe1 Bxe3 18 fxe3 Bxc4 19 b3

Be6 20 Kf2 Ke7 21 Rhd1 Rhd8 22 Rxd8 Rxd8 23 Rd1 Rxd1 24 Bxd1 a5 25 Ke2 b5

26 a3 h4 27 Kd3 c5 28 Kc3 b4+ 29 axb4 axb4+ 30 Kd3 Kd6 31 Bc2 Bc8 32 Kd2

Ba6 33 Bd3 c4! 0-1

The coming pawn ending is hopeless for White in view of Black’s reserve tempo

moves—the variations are quite interesting: 34 Bxc4 (or 34 bxc4 Kc5) 34 ... Bxc4 35

bxc4 Kc5 36 Kd3 b3 37 Kc3 b2 38 Kxb2 Kxc4 39 Kc2 f6! 40 Kd2 Kb3 and now:

a) 41 Kd1 Kc3 42 Ke2 Kc2 43 Ke1 Kd3 44 Kf2 Kd2 45 Kf3 Ke1 46 Kg4 Kf2 47

42

Kxh4 Kxg2 48 Kg4 Kf2 49 h4 Kxe3 50 h5 gxh5+ 51 Kxh5 Kxe4 52 Kg6 Kf3 53 Kxf6

e4 and queens.

b) 41 Kd3 Kb2 42 Kd2 (or 42 Kc4 Kc2 43 Kd5 Kd3 44 Ke6 Kxe3 45 Kxf6 Kxe4

46 Kxg6 Kf4 47 Kh5 Kg3 48 Kg5 e4 and again the e-pawn promotes) 42 ... g5! 43

Kd1 Kc3 44 Ke2 Kc2 45 Kf3 Kd3 46 Kg4 Kxe4 47 Kh5 Kxe3 48 Kg6 Kf4 49 Kxf6 e4

and once again the e-pawn goes through.

Alekhine scored a nice technical win once he got his position after move 13, but I

would have liked to have seen his face after 4 e4!.

Summary

The really scary win here is Game 8, where Black plays ten seemingly reasonable

moves and then might as well resign. The 23 and 20-move debacles of Games 5 and 6

do not inspire confidence, nor does the gambit 4 ... d6 of Game 9. But one should note

Black was better out of the opening in Game 4, and actually won in Game 7.

I’m going to amplify this further in Chapters 3 and 4, but one should already be

getting the feeling that 4 ... Nxe5 against the Alekhine Attack is suspect. The only

reason Gilg got into Game 7 was due to Alekhine’s time wasting 6 a3.

This leaves the 4 ... h5 of Alekhine-Euwe as the last man standing, and I will give

full coverage of this line—that I consider critical and best—in Chapter 5.

43

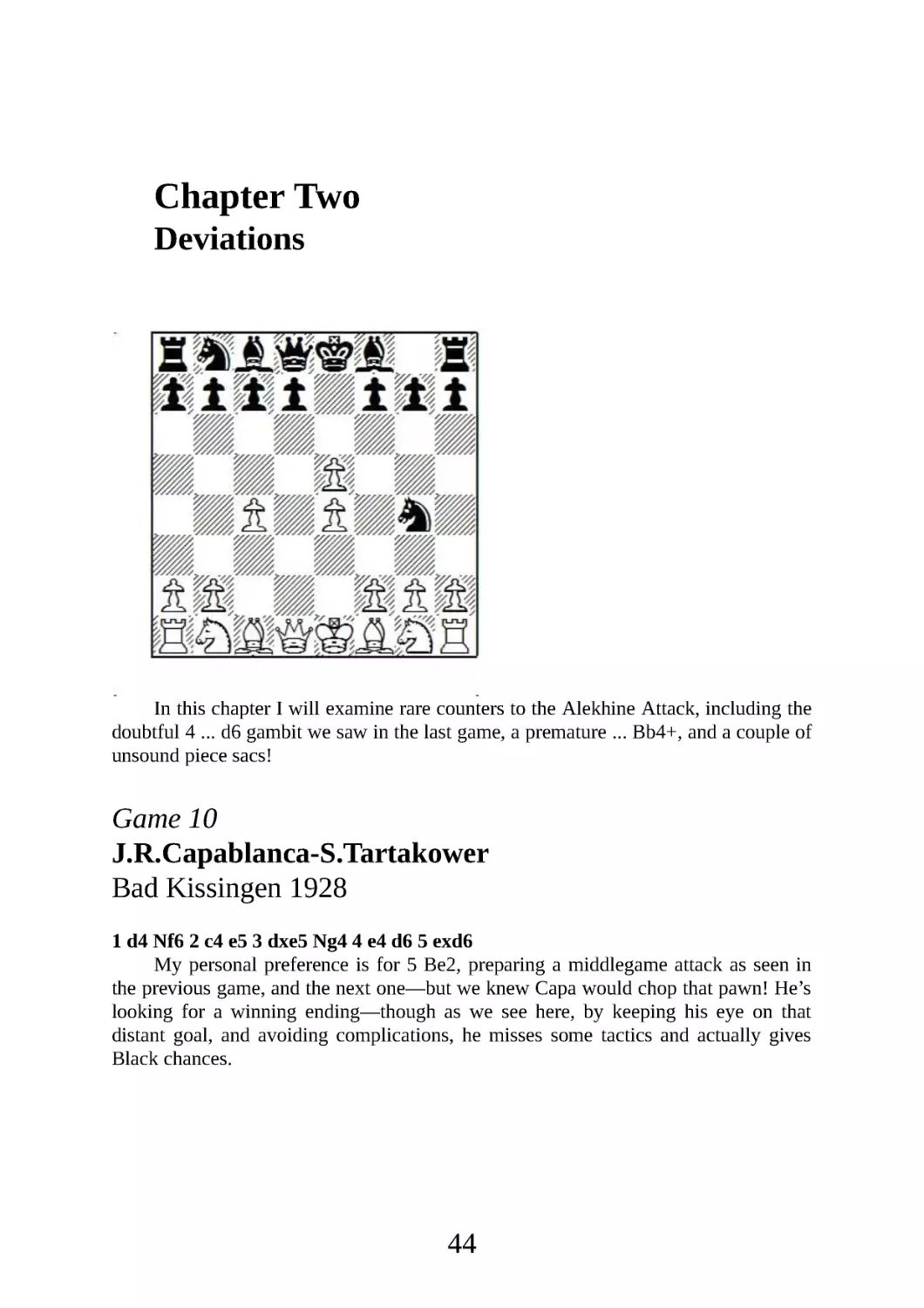

Chapter Two

Deviations

In this chapter I will examine rare counters to the Alekhine Attack, including the

doubtful 4 ... d6 gambit we saw in the last game, a premature ... Bb4+, and a couple of

unsound piece sacs!

Game 10

J.R.Capablanca-S.Tartakower

Bad Kissingen 1928

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 d6 5 exd6

My personal preference is for 5 Be2, preparing a middlegame attack as seen in

the previous game, and the next one—but we knew Capa would chop that pawn! He’s

looking for a winning ending—though as we see here, by keeping his eye on that

distant goal, and avoiding complications, he misses some tactics and actually gives

Black chances.

44

5 ... Bxd6

Since this doesn’t turn out well for Black at all, I was wondering if 5 ... Qxd6

might improve, so I tested it against my German sparring partner—and was crushed as

follows: 6 Qxd6 Bxd6 7 Be2 Nc6 8 Nf3 0-0 9 0-0 Re8 10 Nc3 f5 11 exf5 Bxf5 12 h3

Nge5 13 Nxe5?! Bxe5 14 Be3 Nd4 15 Bxd4 Bxd4 16 Rfe1 c6 17 Rad1 Rad8 18 Bf3

Rxe1+ 19 Rxe1 Bf6 20 Rd1 Rxd1+ 21 Nxd1 Bd3 22 b3 Bb1 23 a3 Ba2 24 b4 Bxc4

and Black was winning in T.Taylor-Comp Fritz 11, blitz game 2008. Careful analysis

reveals that I missed a subtle improvement: correct is the precise 13 Be3! Bd3 (both

13 ... Nd3 14 Nh4 and 13 ... Nxf3+ 14 Bxf3 Bd3 15 Bd5+ are good for White) 14

Nxe5 Bxe2 15 Nxe2 Bxe5 16 Rad1! and White keeps the pawn with winning chances.

But I think Black has some genuine practical play in this line, which is another

reason why I favour 5 Be2.

6 Be2!

Accurate! By developing with a threat White sets his opponent insoluble

problems, and also avoids the trick 6 Nf3? Bb4+ 7 Bd2 Bc5! and Black won in

J.Kinman-G .Koshnitsky, Perth 1928, as f2 falls.

6 ... f5

This fails tactically, but even after 6 ... Nf6 7 Nc3 (White scored a quick win with

7 Nf3 Nxe4 8 0-0 0-0 9 Nbd2 Re8 10 Nxe4 Rxe4 11 Bd3 Re8 12 Ng5 h6 13 Qh5 g6

14 Qxh6 1-0 S.Himmelmann-T.Schuler, Bremen 1992, but Black could have defended

better with 9 ... Nf6) 7 ... Nc6 8 Nf3 0-0 9 Be3, developing while threatening c4-c5,

it’s hard to see any real compensation for Black.

Note also that 6 ... h5 just transposes back to the note to move 6 of the previous

game, which showed that Black had nothing for the pawn there either.

7 exf5 Qe7

This should lose quickly, but on other moves Black is two pawns down for not

much.

8 Nf3?

Capablanca, dreaming of his pawn up ending, fails to notice that he can win a

45

piece right now!

Correct is 8 c5! when Black’s knight on g4 is hanging. After 8 ... Bxc5 9 Qa4+

Nc6 10 Qxg4 Black does not have enough for the piece:

a) 10 ... Nb4 11 Bg5 Nc2+ (11 ... Qe5 12 Qh5+ Kf8 13 f6 Nc2+ 14 Kd1 Nxa1 15

fxg7+ Kxg7 16 Bh6+ Kf6 17 Bg7+ wins the queen) 12 Kd1 Qe5 13 Qh5+ Kf8 14 Nf3

Qd5+ 15 Kxc2 Bxf5+ 16 Kc1 Qe4 (or if 16 ... Bxf2 17 Nc3 with a winning attack, as

Rf1 comes next) 17 Ne1 Bxf2 18 Rf1 Be3+ (18 ... Bxe1 19 Rxf5+ Qxf5 20 Be7+

again picks off the queen) 19 Bxe3 Qxe3+ 20 Nd2 Qc5+ 21 Bc4 and wins.

b) 10 ... Nd4 11 Qh5+ Qf7 (if 11 ... Kf8 12 f6! gxf6 13 Bh6+ Kg8 14 Nc3 Nc2+

15 Kd1 Nxa1 16 Bc4+ Be6 17 Qg4+ wins major material) 12 Qxf7+ Kxf7 13 Bd3 and

White is just a piece up.

c) 10 ... 0-0 11 Bg5 develops with gain of time, demonstrating that Black has

nothing real for the piece.

As far as I can see, this constitutes a clear refutation of the 4 ... d6, 5 ... Bxd6

gambit.

8 ... Bxf5 9 Bg5

White could also play to win more material with 9 Qd5, but it’s not so clear as

the above piece win. Black could get at least a confusing position after 9 ... Bg6 10

Qxb7 Bd3.

9 ... Nf6 10 Nc3 Nc6 11 Nd5 Qf7 12 0-0 0-0 -0 13 Nd4 Nxd4 14 Qxd4 c6 15

Bxf6 gxf6

46

16 Qxf6?

Another tactical mistake, and this one is even more serious—as after this move

White not only loses all his advantage, Black can start playing for a win!

Clearly White’s plan is to exchange queens, but as will be seen, this could

backfire. Instead of thinking of the ending, Capa should have thought of mating his

opponent in the middlegame!

Correct is to sac a piece with 16 Qxa7! cxd5 17 cxd5, when I can’t find a way out

for Black: 17 ... Rdg8 (17 ... Qxd5 loses more quickly, e.g . 18 Rac1+ Bc7 19 Rfd1 Qe5

20 Qa8 mate, or 18 ... Kd7 19 Rfd1 with a winning attack) 18 Rac1+ (but not 18 Bb5?

Bxh2+ 19 Kxh2 Qh5+ 20 Kg1 Rxg2+ 21 Kxg2 Rg8 and it’s White who gets mated) 18

... Kd7 (18 ... Bc7 fails to 19 Qa8+ Kd7 20 Bb5+ Ke7 21 Rfe1+ Be5 22 d6+ Kxd6 23

Qa3+ Ke6 24 Qb3+ Ke7 25 Rc7+ and wins) 19 Rfe1! (19 Qxb7+ Ke8 20 Qc6+ Qd7

21 Bb5 Qxc6 22 Rxc6 Bb8 23 Rxf6+ Bd7 would be more of a slog with the five

pawns for the piece) and now:

47

a) 19 ... Rxg2+ 20 Kxg2 Qg6+ (or 20 ... Qxd5+ 21 f3 and Black has no more

good checks) 21 Kh1 Be4+ 22 f3 Qh5 23 Qxb7+ Ke8 24 Rc8 mate.

b) 19 ... Bxh2+ 20 Kxh2 Rxg2+ 21 Kh1 Rg1+ (if 21 ... Qxd5 22 Bb5+ Qxb5 23

Qd4+ Qd5 24 Qxd5 mate) 22 Rxg1 Qxd5+ 23 f3+ and now that the checks are done,

Black will be mated.

c) 19 ... Qxd5 is relatively best, but after 20 g3 White has a safe king, while there

is no shelter for the black monarch. There are many variations, but White’s attack

looks decisive, e.g . 20 ... Bh3 (20 ... Ra8 21 Qb6 and 20 ... h5 21 Bc4 Qc6 22 Bxg8

both lose quickly) 21 Qa4+ Kd8 22 Bf1 Bxf1 23 Rxf1 Ke7 (if 23 ... h5 24 Rfd1 Qe5

25 Qa8+ Ke7 26 Qxb7+ Ke6 27 Re1 wins the queen) 24 Rfe1+ Kf7 (if 24 ... Be5 25 f4

recovers the sacrificed piece) 25 Rcd1 and it’s all over. A typical finish could be 25 ...

Qc5 26 Qd7+ Be7 27 Rd5 Qb4 28 Qe6+ Kf8 (or 28 ... Ke8 29 a3) 29 Rd7 Rg7 30

Rd8+ Bxd8 31 Qe8 mate.

But Capablanca was unable to switch gears and go over to the attack—and so

took the wrong pawn. Now he would be in serious trouble if Black played correctly ...

16 ... Qxf6??

But Tartakower misses his chance!

Black can take over the game with the Kotovian creeping move 16 ... Qg6!!

48

What to do? The knight is hanging, but if the knight moves, the queen is lost. If

the white queen exchanges itself, then Black breaks through on the h-file with good

winning chances. If White moves the knight with check, this happens: 17 Ne7+ Bxe7

18 Qxe7 Rhe8 and Black wins a piece.

What can White do? We’ve already seen that the knight check fails. Also bad are:

a) 17 Qxg6 hxg6 18 Nc3 Bxh2+ 19 Kh1 Rd2 and Black has a winning advantage

in view of the threats ... Be5+ and ... Rxb2.

b) 17 g4 Be6 18 Rac1 (not 18 Ne7+ Be7 19 Qxe7 as 19 ... Rd2 20 Rfe1 Bxg4

wins for Black) 18 ... Kb8 19 Qxg6 hxg6 20 Nc3 Bxh2+ 21 Kg2 Be5 22 Rh1 (not 22

Rfd1 Rh2+ 23 Kg1 Rdh8 with a big attack for Black) 22 ... Rxh1 23 Rxh1 Rd2 and

White is struggling to draw.

c) Fritz comes up with what is apparently the only save, 17 c5!, but even this

fails to equalize: 17 ... Qxf6 (or 17 ... Bxc5 18 Qc3 Be4 19 Nf4 Qf5 when Black is

only one pawn down and certainly has enough compensation with his strong bishops; I

would prefer Black here, but the ending looks even stronger) 18 Nxf6 Bxc5 19 Bg4

Bxg4 20 Nxg4 Rd2 and White is fighting for his life—Black will at least recover his

pawn with the better game.

So Capablanca’s “better ending” could have become just that—for Black!—

because he failed to force the win tactically at two crucial moments. One cannot win

every game in a technical positional style!

Of course, now that Black has blundered, Capa gets his position and wins just as

he had planned. There is truly no justice in chess.

17 Nxf6 Be5 18 Bg4 Bxf6

Or 18 ... Bxg4 19 Nxg4 Bxb2 20 Rad1.

19 Bxf5+ Kc7 20 Rad1 Bxb2 21 Rxd8 Rxd8 22 Bxh7 Rd4 23 g3

And now Capa takes his single extra pawn and grinds to victory; even the

opposite-coloured bishops fail to disturb his relentless technique.

49

23 ... Rxc4 24 h4 b5 25 Kg2 a5 26 h5 Bg7 27 f4 Bh6 28 Re1 Ra4 29 Bg8 Rd4

30 Re7+ Rd7 31 Rxd7+ Kxd7 32 Kf3 c5 33 g4 c4 34 g5 Bf8 35 h6 a4 36 f5 Kc6 37

h7 Bg7 38 f6 c3 39 Ke2 Bh8 40 f7 1-0

One can’t say too many good things about the 4 ... d6 gambit, but if you must

play it, take back with the queen when Black has practical chances. After the bishop

recapture, White was essentially winning by move 6, even though the game contained

various misadventures beyond that point!

Game 11

S.Reshevsky-A.Denker

Syracuse 1934

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 d6 5 Be2

We saw this in Game 9: instead of accepting the gambit, White aims for a

favourable Alekhine Attack, where the f8-bishop is blocked.

5 ... Nxe5

We recall that after the alternative, Alekhine’s 5 ... h5 in the above-mentioned

game, White could have got the advantage with the simple 6 exd6 when Black has

nothing for the pawn, or in the game after 6 Nc3 Nc6 7 h3 Ngxe5 White could have

struck hard with 8 f4!.

6 f4

50

6 ... Ng4

No matter where Black’s knight moves, he will not have sufficient counterplay to

balance White’s space advantage with the f8-bishop blocked in—we saw this type of

play already in the Alekhine-Gallego crush, Game 8.

a) 6 ... Ng6 7 Nf3 Nc6 8 0-0 Be7 9 Nc3 0-0 10 Be3 Re8 11 Qd2 Bf6 12 Nd4 with

a clear space advantage in O.Katajisto-B.De Greif, Amsterdam Olympiad 1954.

b) 6 ... Nec6 7 Nf3 Be7 8 Nc3 0-0 and now White won quickly after 9 Nd5 Nd7

10 0-0 Nc5 11 e5 Re8?! (11 ... dxe5 puts Black back in the game) 12 b4 Nd7 13 b5

Ncb8 14 Ba3 in A.Fomin-N .Miasnikov, USSR 1955; but I think I would played less

impetuously and kept my pawns together with 9 0-0 and a steady positional advantage.

7 Nf3

Not 7 Bxg4 Qh4+ with counterplay.

7 ... Nc6 8 0-0 Bd7?!

Slightly better is 8 ... Be7 9 Nc3 0-0 10 h3 Nf6 11 Be3, but White has a sound

grip on the position while Black has no counterplay to speak of—e .g . 11 ... Nh5 12

Qe1 Bf6 13 Nd5 Bxb2 14 Rb1 Ba3 (14 ... Bf6 15 g4 snags the knight on rim) 15 e5

and White has a tremendous attack for a single pawn.

9 Nc3 Be7 10 h3 Nf6 11 e5!

51

The knight has no good square.

11 ... dxe5 12 fxe5 Ng8

Or 12 ... Nh5 13 Kh2 g6 14 Bh6 Bf8 15 Qc1 with a winning attack.

13 Be3 f6!?

13 ... Be6 14 Qc1 with Rd1 coming is virtually winning.

14 Bd3!

Reshevsky switches to direct attack.

14 ... fxe5

After the more solid 14 ... Be6 15 Qe2 White’s position is overwhelming.

15 Ng5! Nf6

If 15 ... Bxg5 16 Qh5+ g6 17 Bxg6+ hxg6 18 Qxg6+ Ke7 19 Bc5 mate.

52

16 Rxf6!

Black could resign.

16 ... Bxf6 17 Qh5+ g6 18 Bxg6+ hxg6 19 Qxg6+ Ke7 20 Qf7+ Kd6 21 c5

mate

In general, it’s clear (look how quickly White is winning these games!) that the

Budapest Gambiteer must be thoroughly prepared for the Alekhine Attack, and that

this attack in the hands of a bold attacking player is very dangerous indeed.

Specifically, I think the last two games show that 4 ... d6 is mistaken to put it

mildly: Black doesn’t get enough for the pawn after Capablanca’s gambit acceptance,

and falls under fierce attack after Reshevsky’s 5 Be2.

Game 12

S.Reshevsky-H.Seidman

US Championship, New York 1951

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5

Black can throw in an early ... Bb4+ at many points in the Alekhine Attack, but I

can’t see any value to it. In general, after the transaction ... Bb4+ and an exchange of

bishops on d2, White develops his queen while Black has released any pressure he had

on White’s position. Therefore Black should wait until White has played the b1-knight

out (to pin it) or moved the c1-bishop (Be3) so a check will force White to pin himself

or lose time with Be3-d2. The main game and notes show the gains White gets from

such premature checks.

3 ... Ng4

After 3 ... Bb4+ 4 Bd2 Bxd2+ 5 Qxd2 Ng4 6 Qf4 Black had no compensation for

the pawn in T.Kirschneck-C.Saing, German League 2005.

4 e4 Nxe5

4 ... Bb4+ is not much better here: 5 Bd2 Bxd2+ 6 Qxd2 Nxe5 7 f4 Nec6 8 Nf3

Qe7 9 Nc3 (White leads in development and has taken over the centre) 9 ... 0-0 10 Bd3

Nb4 11 Be2 f5 12 exf5 Rxf5 13 a3 N4a6 14 0-0 d6 (14 ... Nc5 15 Nd5 Qd6 16 Qc2

followed by Rad1 is winning for White) 15 Bd3 Rh5 16 Nd5 (White dominates the

board and has a huge lead in development) 16 ... Qf8 17 Rae1 Nd7 18 Ng5 Nf6 19

Ne7+ Kh8 20 Bg6! (a pretty finishing blow) 1-0 D.Sahovic-P.Kresoja, Belgrade 1993.

5 f4 Bb4+

Or here!

6 Bd2 Bxd2+ 7 Qxd2 Ng6 8 Nc3 d6 9 Nf3 0-0 10 Bd3 Nd7 11 0-0 Nc5 12 Bc2

White has obtained an ideal attacking set-up just by making natural moves.

Notice how the exchange on d2 helped White’s development flow, and of course there

was no awkward business of kingside castling prevented or delayed by ... Bc5.

53

12 ... a5 13 Nd4 f6 14 Rae1 Bd7 15 Kh1 Re8 16 Re3 Bc6 17 b3 Nf8 18 a3 Kh8

19 Rfe1 Qe7 20 f5!

Lasker style! Reshevsky cramps Black’s king position, takes away e6 and g6

from the black knights, and prepares a direct attack on the king.

20 ... Ncd7 21 Nd5 Qd8 22 Nf4 Ne5 23 Qe2 Qe7 24 Rh3 Qf7 25 Nde6

One recalls that in the famous Lasker-Capablanca duel alluded to above, Black

had a serious counter-chance when he could have sacrificed the exchange for a knight

on e6:

Em.Lasker-J.R.Capablanca

St Petersburg 1914

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 dxc6 5 d4 exd4 6 Qxd4 Qxd4 7 Nxd4 Bd6 8

54

Nc3 Ne7 9 0-0 0-0 10 f4 Re8 11 Nb3 f6 12 f5 b6 13 Bf4 Bb7 14 Bxd6 cxd6 15 Nd4

Rad8 16 Ne6 Rd7 17 Rad1 Nc8 18 Rf2 b5 19 Rfd2 Rde7 20 b4 Kf7 21 a3

Here Black could have obtained good practical drawing chances with 21 ... Rxe6,

but missed his opportunity and went on to defeat: 21 ... Ba8 22 Kf2 Ra7 23 g4 h6 24

Rd3 a5 25 h4 axb4 26 axb4 Rae7 27 Kf3 Rg8 28 Kf4 g6 29 Rg3 g5+ 30 Kf3 Nb6 31

hxg5 hxg5 32 Rh3 Rd7 33 Kg3 Ke8 34 Rdh1 Bb7 35 e5 dxe5 36 Ne4 Nd5 37 N6c5

Bc8 38 Nxd7 Bxd7 39 Rh7 Rf8 40 Ra1 Kd8 41 Ra8+ Bc8 42 Nc5 1-0

Here, too, Black will have that opportunity, so perhaps White should have simply

kept the pressure with 25 Nd5.

25 ... Rac8

Black, like Capablanca, can’t muster the gumption to sacrifice the exchange. 25

. .. Nxe6 26 Nxe6 Rxe6! 27 fxe6 Qxe6 would be very hard for White to win.

26 b4 Bd7 27 Nxf8! Rxf8

55

Now White has a decisive attack—but misses the winning combination three

times in a row!

28 c5

28 Ng6+! wins as both defences are forcibly crushed:

a) 28 ... Nxg6 29 Rxh7+ Kxh7 (or 29 ... Kg8 30 Qh5 Bxf5 31 exf5 Rfe8 32 Be4

and White mates or wins massive material) 30 Qh5+ Kg8 31 fxg6 wins the queen.

b) 28 ... Kg8 29 Rxh7! (threatening mate in one, which always gets the

opponent’s attention!) 29 ... Qxc4 (or 29 ... Nxg6 30 Qh5 and wins as in line ‘a’) 30

Qh5 Rfd8 (not 30 ... Qxc2 31 Ne7 mate) 31 Nxe5 and mates.

28 ... dxc5 29 bxc5

29 Ng6+! wins.

29 ... a4 30 Bb1

30 Ng6+! wins.

30 ... Qe8 31 Ng6+!

Finally the light bulb comes on!

31 ... Nxg6 32 Rxh7+ Kxh7 33 Qh5+ Kg8 34 fxg6 Rf7 35 e5!

56

White adds the bishop to his attack.

35 ... Be6

This prolongs the game as long as possible, but there is no defence.

35 ... fxe5 fails to 36 Ba2 Be6 37 Qh7+ Kf8 38 gxf7 Qxf7 (also losing is 38 ...

Bxf7 39 Rf1 Rd8 40 Bxf7 Qxf7 41 Qh8+ Ke7 42 Rxf7 and White wins everything) 39

Bxe6 Qxe6 40 Rf1+ Ke7 (or 40 ... Ke8 41 Qxg7 Qe7 42 Qg6+ Kd7 43 Rd1+ and

White wins the queen for a pawn) 41 Qxg7+ Kd8 42 Rf8+ wins the queen for a rook,

which isn’t much better!.

Another hopeless try is 35 ... f5 36 e6 Bxe6 37 Ba2 Rf6 (taking the bishop allows

a slightly quicker mate: 37 ... Bxa2 38 Qh7+ Kf8 39 Qh8 mate) 38 Qh7+ Kf8 39 Qh8+

Ke7 40 Qxg7+ Rf7 41 Rxe6+ Kd7 42 Qd4 mate.

36 Qh7+ Kf8 37 Qh8+ Ke7 38 exf6+ Kd7

Now White gets a winning ending. The most entertaining try is 38 ... gxf6 (38 ...

Kxf6 allows mate in one with 39 Qh4) but White’s attack is nonetheless decisive after

39 Qh3! Kd7 40 Qd3+ Kc6 (or 40 ... Ke7 41 gxf7 Qxf7 42 Ba2 and White comes out a

piece ahead) 41 Qe4+ Kb5 (if 41 ... Kxc5 42 Qb4+ Kc6 43 Rc1+ Kd7 44 Rd1+ Kc6 45

Be4+ Bd5 46 Bxd5+ Kd7 47 Bxb7+ Ke6 48 Qe4 mate) 42 Qxb7+ Ka5 43 Bd3 with a

mating attack, e.g . 43 ... Bc4 (43 ... Ra8 allows 44 Qb4 mate) 44 Qb4+ Ka6 45 Qxc4+

Kb7 46 Qa6+ Kb8 47 Rb1+ Qb5 48 Rxb5 mate.

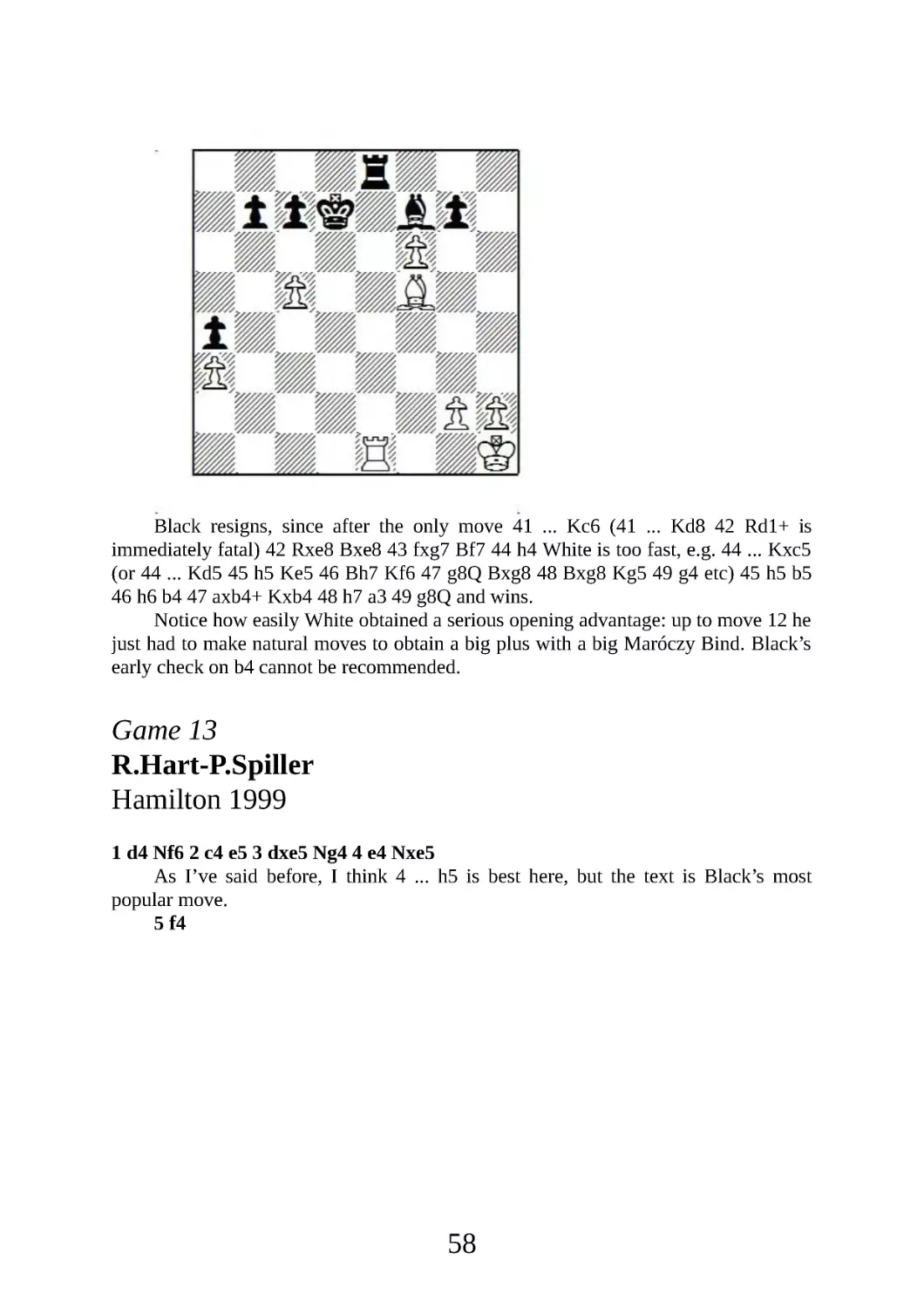

39 Qxe8+ Rxe8 40 gxf7 Bxf7 41 Bf5+ 1-0

57

Black resigns, since after the only move 41 ... Kc6 (41 ... Kd8 42 Rd1+ is

immediately fatal) 42 Rxe8 Bxe8 43 fxg7 Bf7 44 h4 White is too fast, e.g . 44 ... Kxc5

(or 44 ... Kd5 45 h5 Ke5 46 Bh7 Kf6 47 g8Q Bxg8 48 Bxg8 Kg5 49 g4 etc) 45 h5 b5

46 h6 b4 47 axb4+ Kxb4 48 h7 a3 49 g8Q and wins.

Notice how easily White obtained a serious opening advantage: up to move 12 he

just had to make natural moves to obtain a big plus with a big Maróczy Bind. Black’s

early check on b4 cannot be recommended.

Game 13

R.Hart-P.Spiller

Hamilton 1999

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5

As I’ve said before, I think 4 ... h5 is best here, but the text is Black’s most

popular move.

5 f4

58

The next two chapters will be devoted to the knight retreats to g6 and c6

respectively; but before we get there, let’s consider this question: does Black have to

move the knight at all?

5 ... Nbc6

The other potential sacrifice, 5 ... Bc5, is weaker as there is no knight check on

b4, allowing a Qd3 defence as will be seen: 6 fxe5 Qh4+ 7 Kd2 Bxg1 (7 ... Qf4+ 8

Kc2 Qxe4+ 9 Qd3 is the point, when Black’s attack is stopped in its tracks—of course

this defence wouldn’t work with a black knight on c6) 8 Rxg1 Qf2+ 9 Be2 and Black

has no real compensation for the piece.

6 fxe5

6 Nc3 is a safe alternative, reverting to a typical Alekhine Attack, but my Fritz-

assisted analysis says there’s nothing wrong with just taking the piece.

6 ... Qh4+ 7 Kd2 Qf4+

59

Now White can draw with 8 Ke1 Qh4+ 9 Kd2 Qf4+ 10 Ke1 Qh4+ 1⁄2-1⁄2 L.Gomez

Cabrero-F.Fons Cervero, Valencia 1995, but let’s pass over that passivity and look at

White’s winning tries.

8 Kd3

The curious 8 Kc3 also seems to win for White:

a) 8 ... Qxe5+ plays into White’s hands, as the soon to be open e-file facilitates

exchanges that favour him: 9 Kd2 Qd4+ (or 9 ... Qf4+ 10 Ke1 Qh4+ 11 g3 Qxe4+ 12

Qe2 etc) 10 Ke1 Qxe4+ 11 Qe2 (the reason White wants the e-file open) 11 ... Qe6 12

Nf3 Bb4+ 13 Kf2 d6 (13 ... Bc5+ 14 Be3 just leads to more exchanges and the queens

still come off) 14 Qxe6+ fxe6 15 Be3 0-0 16 a3 Bc5 17 Bxc5 dxc5 18 Nc3 1-0

J.Rezek-P.Kipasso, correspondence 2001, as Black has nothing for the piece.

b) 8 ... Bb4+ fails to give adequate compensation either: 9 Kb3 Nd4+ 10 Kxb4

Qxe5 11 Kc3! Nf3+ (if 11 ... c5 12 Kd2! Qf4+ 13 Kd3 Qd6 14 Nc3 Nb3+ 15 Nd5

Nxa1 16 Bf4 or 14 ... b5 15 Nd5 bxc4+ 16 Ke3 Bb7 17 Bxc4 f5 18 Nf3 fxe4 19 Nxd4

cxd4+ 20 Qxd4 and White wins easily) 12 Kd3 Qd4+ 13 Ke2 Nxg1+ 14 Ke1 Qxe4+

15 Kd2 Qf4+ (after 15 ... Nh3 16 Nc3 Qd4+ 17 Kc2 Qxd1+ 18 Nxd1 or 16 ... Qc6 17

Qe1+ Kf8 18 Qh4 White emerges with two extra pieces) 16 Kc2 Qf2+ 17 Bd2 d6 18

Bd3 wins the trapped knight and soon the game.

However, the third king move is not the charm: 8 Kc2?! Qxe4+ 9 Bd3? Nb4+ 10

Kc3 Nxd3 11 Qxd3 Bb4+ 12 Kc2 Qxg2+ 0-1 Kartik-Tarrega, correspondence 2001,

was a disastrous loss for White!

60

8 ... Qxe5

Black has also tried two knight checks here:

a) 8 ... Nb4+ 9 Kc3 Qxe5+ 10 Kb3 Qxe4?! (but if 10 ... a5 11 Nc3 d6 12 Nf3 a4+

13 Nxa4 Qa5 14 Nc3 Qb6 15 Nb5 c6 16 Qd4 and Black’s attack comes to a halt; or 10

... b5 11 cxb5 a6 12 Nf3 Qc5 13 Nc3 axb5 14 a3 and once again Black is driven back

while White retains the extra piece) 11 Nc3 and White converted his extra piece in

V.Hendrix-R.Weir, correspondence 1993.

b) 8 ... Nxe5+ 9 Kc3 Qxe4 10 Nf3 d6 11 Bd3 (White also obtained a winning

position with 11 Qe2 in M.Hase-A .Kuhlmann, correspondence 1992) 11 ... Qxd3+

(better is 11 ... Qc6 but after 12 Na3 Black doesn’t really have anything for the piece)

12 Qxd3 Nxd3 13 Kxd3 and White went on to win in A.Közenkov-R.Nocci,

correspondence 1999.

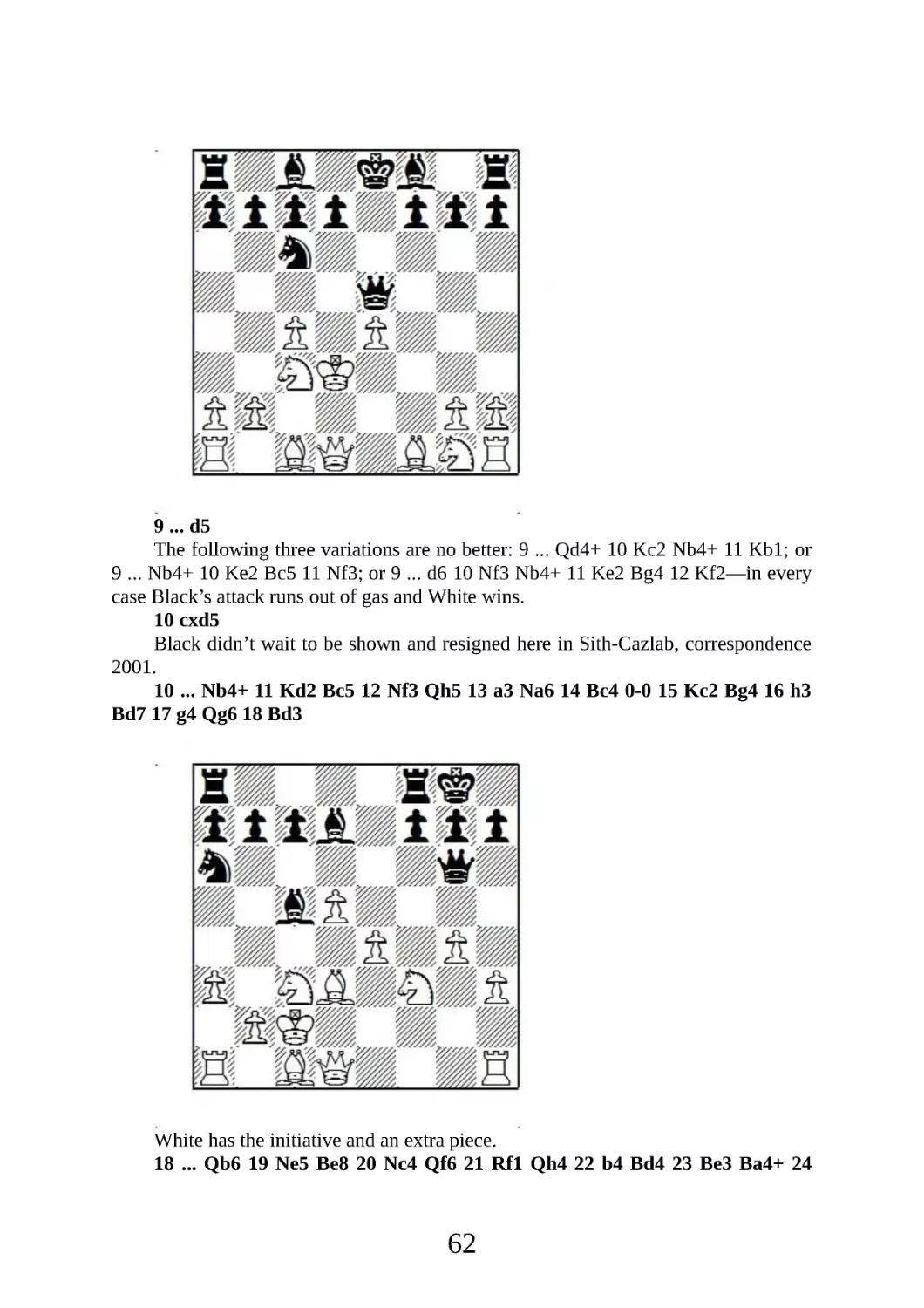

9 Nc3

61

9 ... d5

The following three variations are no better: 9 ... Qd4+ 10 Kc2 Nb4+ 11 Kb1; or

9 ... Nb4+ 10 Ke2 Bc5 11 Nf3; or 9 ... d6 10 Nf3 Nb4+ 11 Ke2 Bg4 12 Kf2—in every

case Black’s attack runs out of gas and White wins.

10 cxd5

Black didn’t wait to be shown and resigned here in Sith-Cazlab, correspondence

2001.

10 ... Nb4+ 11 Kd2 Bc5 12 Nf3 Qh5 13 a3 Na6 14 Bc4 0-0 15 Kc2 Bg4 16 h3

Bd7 17 g4 Qg6 18 Bd3

White has the initiative and an extra piece.

18 ... Qb6 19 Ne5 Be8 20 Nc4 Qf6 21 Rf1 Qh4 22 b4 Bd4 23 Be3 Ba4+ 24

62

Nxa4 Bxa1 25 Qxa1 b5 26 Nd2 Qxh3 27 Rf3 Qxg4 28 Qg1 Qd7 29 Nc3 c6 30 dxc6

Qxc6 31 Bxb5 Qe6 32 Bd4 g6 33 Rf6 1-0

White’s material advantage just might be adequate.

This full piece gambit gives a few practical chances (it is possible to win in 12

moves if White makes a serious error), but in general I cannot recommend it,

especially now that we are in the computer age. If White has looked at this line even a

little bit on a database—and sees that he can get to the basic tabiya after 8 Kd3 by

force—then there doesn’t seem to be any good advice for Black, except: don’t play this

line!

Summary

The conclusions are simple here: none of these lines are acceptable for Black.

The 4 ... d6 gambit is an unsound pawn offer, and Capablanca could have won a piece

on move 8, while Reshevsky’s alternate treatment led to mate in 21. Reshevsky again

hammered the premature ... Bb4+. Finally, the piece sacrifice on move 5 has been tried

repeatedly with no real success, and is consistently refuted by the computer.

63

Chapter Three

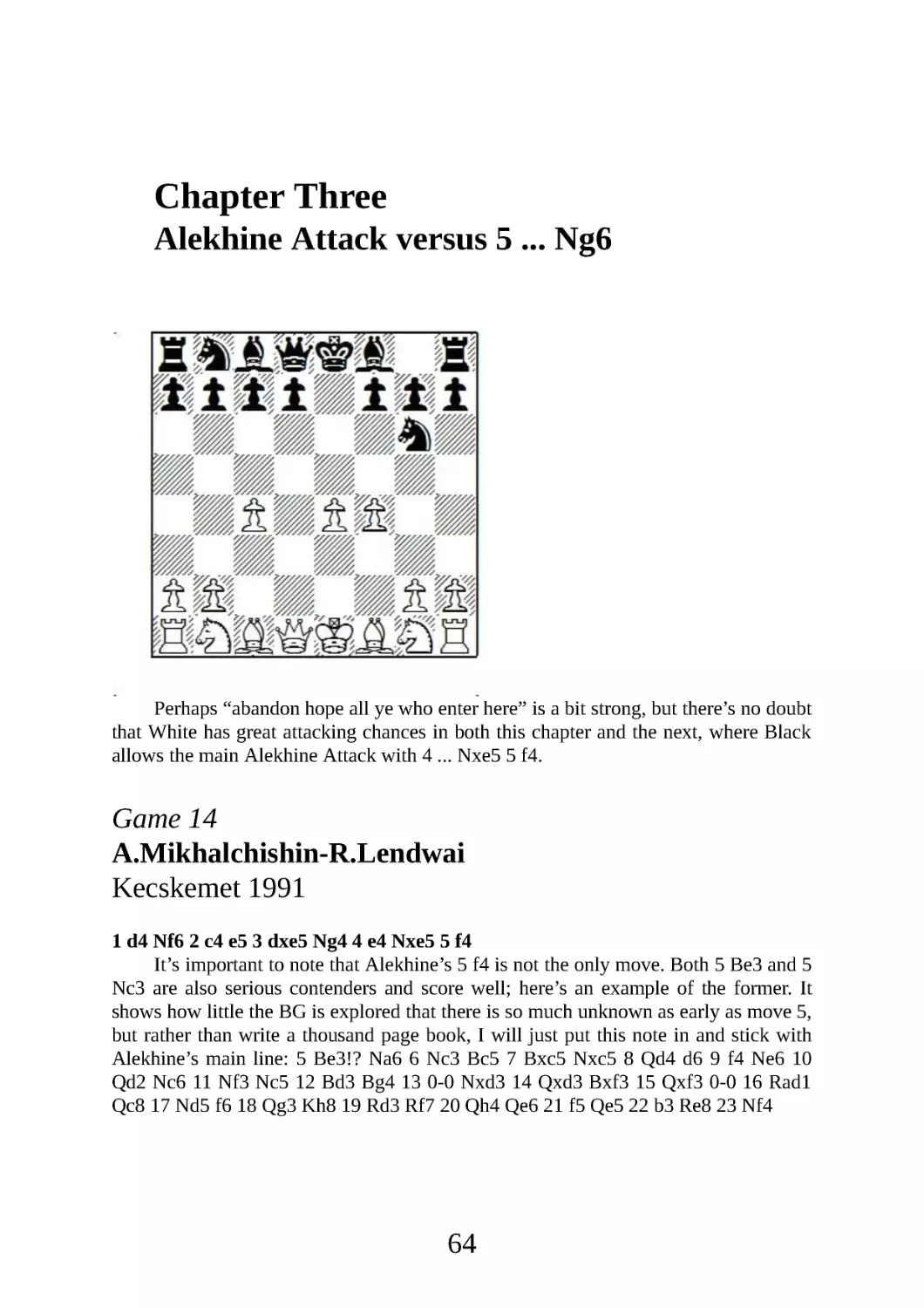

Alekhine Attack versus 5 ... Ng6

Perhaps “abandon hope all ye who enter here” is a bit strong, but there’s no doubt

that White has great attacking chances in both this chapter and the next, where Black

allows the main Alekhine Attack with 4 ... Nxe5 5 f4.

Game 14

A.Mikhalchishin-R.Lendwai

Kecskemet 1991

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 e4 Nxe5 5 f4

It’s important to note that Alekhine’s 5 f4 is not the only move. Both 5 Be3 and 5

Nc3 are also serious contenders and score well; here’s an example of the former. It

shows how little the BG is explored that there is so much unknown as early as move 5,

but rather than write a thousand page book, I will just put this note in and stick with

Alekhine’s main line: 5 Be3!? Na6 6 Nc3 Bc5 7 Bxc5 Nxc5 8 Qd4 d6 9 f4 Ne6 10

Qd2 Nc6 11 Nf3 Nc5 12 Bd3 Bg4 13 0-0 Nxd3 14 Qxd3 Bxf3 15 Qxf3 0-0 16 Rad1

Qc8 17 Nd5 f6 18 Qg3 Kh8 19 Rd3 Rf7 20 Qh4 Qe6 21 f5 Qe5 22 b3 Re8 23 Nf4

64

23 ... Kg8 (23 ... Qxe4 allows a pretty mate: 24 Ng6+ Kg8 25 Qxh7+! Kxh7 26

Rh3+ etc) 24 Re1 Qc5+ 25 Kh1 Ne5 26 Rg3 Qa5 27 Re2 Qa3 28 h3 Qc1+ 29 Kh2

Qd1 30 Rf2 Qe1 31 Ne6 Qb1 32 Rf4 Qxa2 33 Qh5 Ree7 34 Rh4 h6 35 Qd1 Kh7 36

Qc1 Rxe6 37 fxe6 Re7 38 Rxg7+ 1-0 V.Milov-M .Klauser, Swiss Team Ch. 2007.

5 ... Ng6

The somewhat more popular retreat to c6 will be covered in the next chapter.

6 Be3

As an AAA member, I prefer the Alekhine Approved Attack of 6 Nf3 (Games 5,

16 and 17) although the text move is quite playable and Mikhalchishin’s play is

impressive. Still, I think the “king wandering” lines (see the next note) give Black too

many practical chances.

Nonetheless, the game is important for demonstrating White’s attacking chances

after the smallest lapse.

6 ... Nc6

More usual and better is 6 ... Bb4+, which illuminates a slight problem with 6

Be3. It would seem absurd to go back with the bishop (of course Reshevsky got a big

advantage in a similar position with Bd2, but there he hadn’t previously moved the

bishop), so White has to block with the knight: 7 Nd2 (7 Nc3 allows doubled isolated

pawns, which give Black something to reach for in his difficult search for counterplay

— s e e the next game) 7 ... Qe7 8 Kf2 Bc5! (but not 8 ... Bxd2+?! 9 Qxd2 Qxe4 10 Bd3

when White has a tremendous attack for the pawn) 9 Qf3 Nc6 and it’s not so easy for

White to consolidate his position.

7 a3

While I don’t like this pawn move when thrown in too early (see Game 7) here it

has an important function:

65

White’s sixth move already took away c5, and now his seventh takes away b4

from the f8-bishop. Said piece can’t be fianchettoed with the knight blocking the g-

pawn, and ... Bd6 is anti-positional (see the following note). This leaves the very non-

threatening e7 as the only feasible square for the moment. Meanwhile, by preventing

the check, White can develop the queen’s knight to the best square, c3, with no fear of

doubled pawns.

Yes, there is a loss of time, but Mikhalchishin succeeds in consolidating his space

advantage anyway, with the aid of a pawn sacrifice.

7 ... b6

Trying to make a square for the bishop. The alternative 7 ... Bd6 is tricky but

positionally weak: if White does not allow an effective sacrifice the bishop is

obviously misplaced on d6.

a) 8 Nh3 0-0 9 Qh5?! (White has no time for this extravagance; 9 Nc3 is better) 9

. .. Qf6 10 e5 Ncxe5! 11 fxe5 Bxe5 (Black obtains good compensation for the piece in

view of White’s disorganized and undeveloped pieces) 12 Ng5 h6 13 Ne4 Qc6 14

Nbc3 Re8 15 Kd2 f5 16 Qxf5 d5 17 Nf6+ Bxf6 18 Qxd5+ Be6 19 Qxc6 bxc6 20 Re1

Bf5 21 Kc1 Bxc3! 22 bxc3 Rab8! 0-1 I.Potyavin-D .Novitzkij, St Petersburg 2005.

Instead ...

b) 8 g3 is best, as after this simple move Black has no plan: 8 ... Qf6 (trying to

play as in the Novitskij game, but this doesn’t work against solid White play—Black

should probably just accept the loss of tempo and go back with 8 ... Be7) 9 Nc3 and

Black’s position makes no sense. While White can continue to build up with natural

moves like Nf3 and Bg2, Black has to be careful that e4-e5 doesn’t just win a piece

(and it will, soon!) and so has full retreat in his future.

8 Nc3 Bc5 9 Qd3!?

Preparing the aforementioned pawn sacrifice. 9 Qd2 looks more natural, but

Black can stir up some trouble with 9 ... Na5.

9 ... 0-0 10 Nf3 Ba6 11 g3!

66

This pawn sacrifice is the only way to justify White’s seemingly random set-up—

but now everything makes sense! White has threats of h4-h5, either preceded or

followed by Bh3, targeting d7. The f-pawn is now securely protected, so the central e-

and f-pawn phalanx will stay intact.

All this for only one pawn? Go for it!

11 ... Bxc4

I don’t think Black has any choice, as otherwise White continues with the above

noted plans, and Black doesn’t even have any material to compensate.

12 Qxc4 Bxe3 13 Nd5 b5?

The only compensation Black has for his very difficult position is the extra pawn,

so giving it back is a serious, practically fatal mistake. Better is to hang on with 13 ...

Bc5 14 b4 Be7 15 h4 h5 16 Bh3 and White has pressure all over the board, but at least

the extra pawn may provide some solace.

14 Qc3! Bb6 15 Bxb5

67

15 ... Nce7

I don’t think there’s any way Black can overcome his problems now: White has

consolidated his space advantage and has attacking chances in the centre and on the

kingside, for example 15 ... Re8 16 0-0 -0 and Black can’t even take on e4 because of

17 Bxc6 winning a piece, and so must grovel even to maintain material equality.

16 Nxb6 cxb6 17 f5 Rc8

Or 17 ... Nh8 18 0-0 with a decisive positional advantage.

18 Qd3 Nh8 19 Bxd7 Rc5

19 ... Rc7 20 Rd1 doesn’t change anything—White has won a pawn while

maintaining his positional advantage, and finishes smoothly.

20 Rd1 Qc7 21 0-0 Rc2 22 Qb3 Re2 23 e5 Qc5+ 24 Kh1 Re3 25 Qa4

68

25 ... Rxf3

If 25 ... Nd5 the reply 26 e6 is overwhelming.

26 Rxf3 Qxe5 27 Qd4 Qe2 28 Re3 Qf2 29 Rxe7 Qf3+ 30 Kg1 1-0

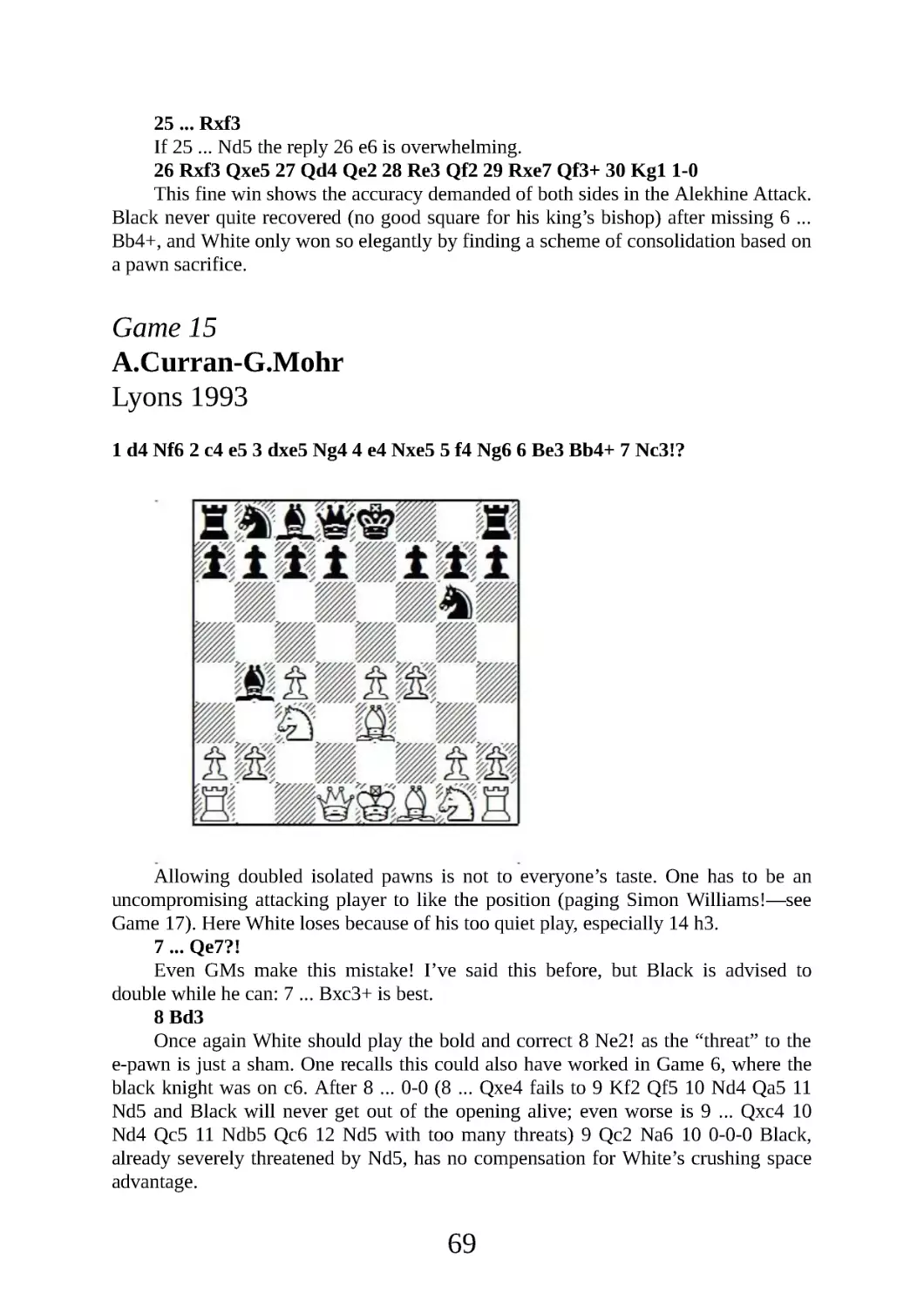

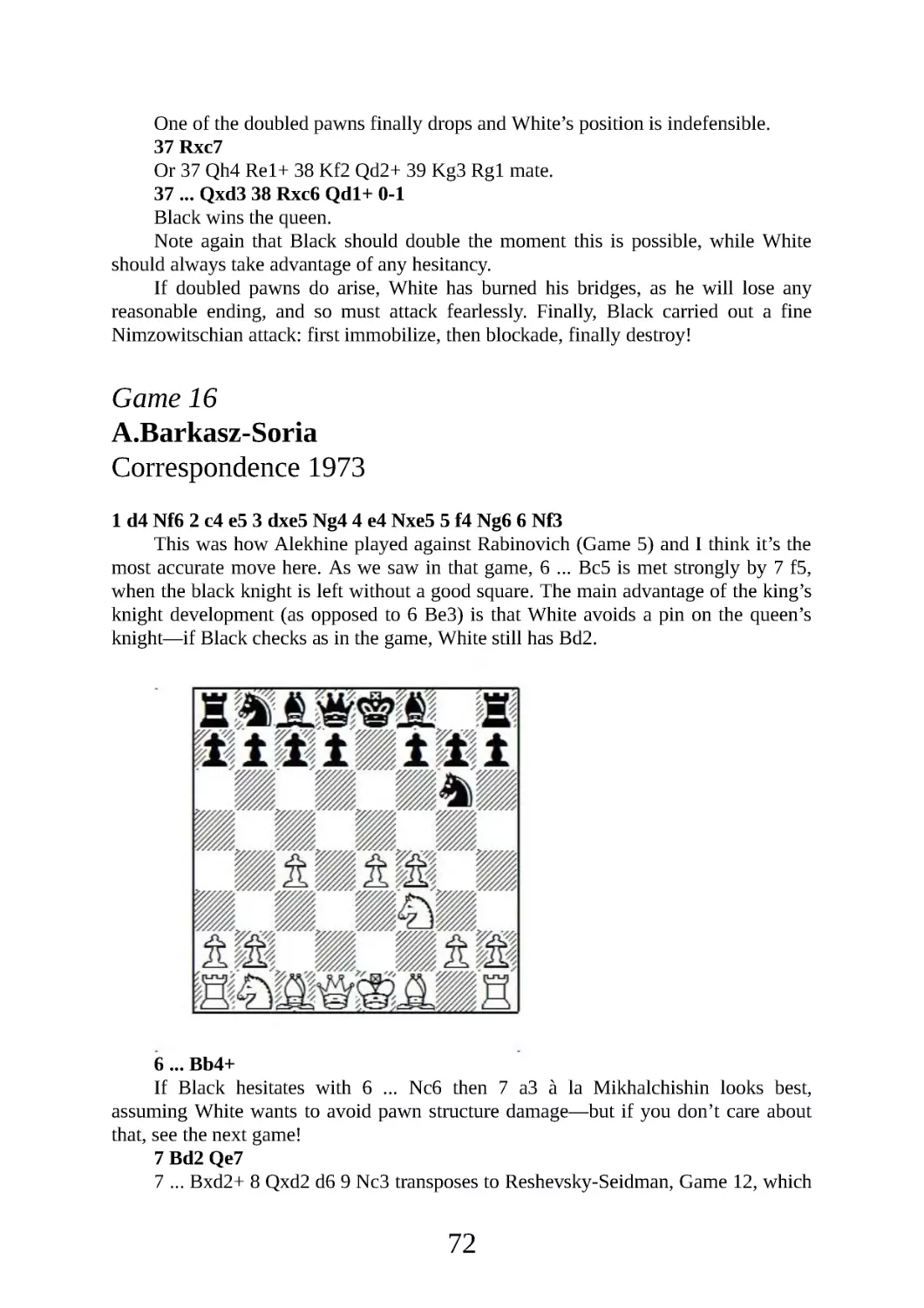

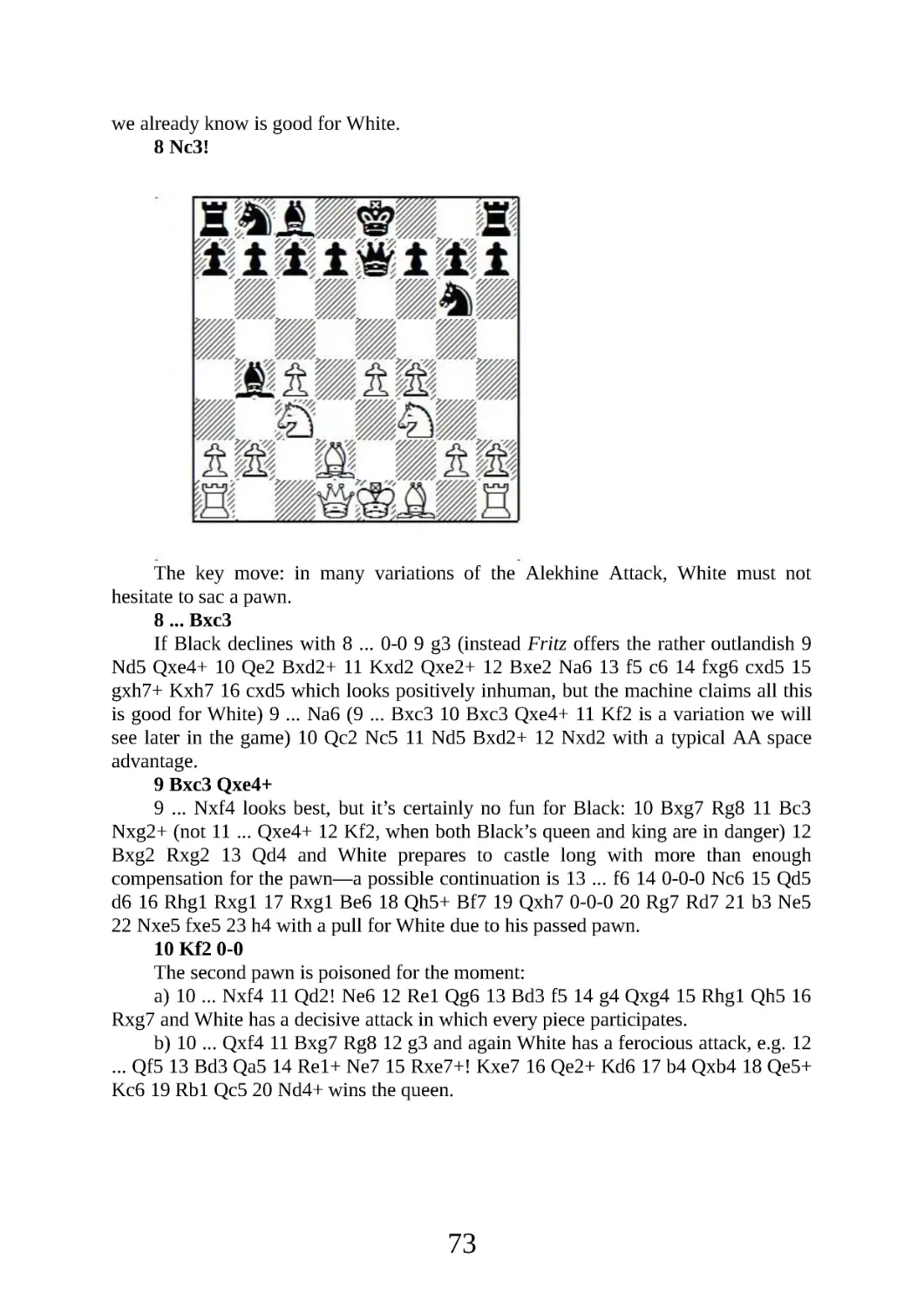

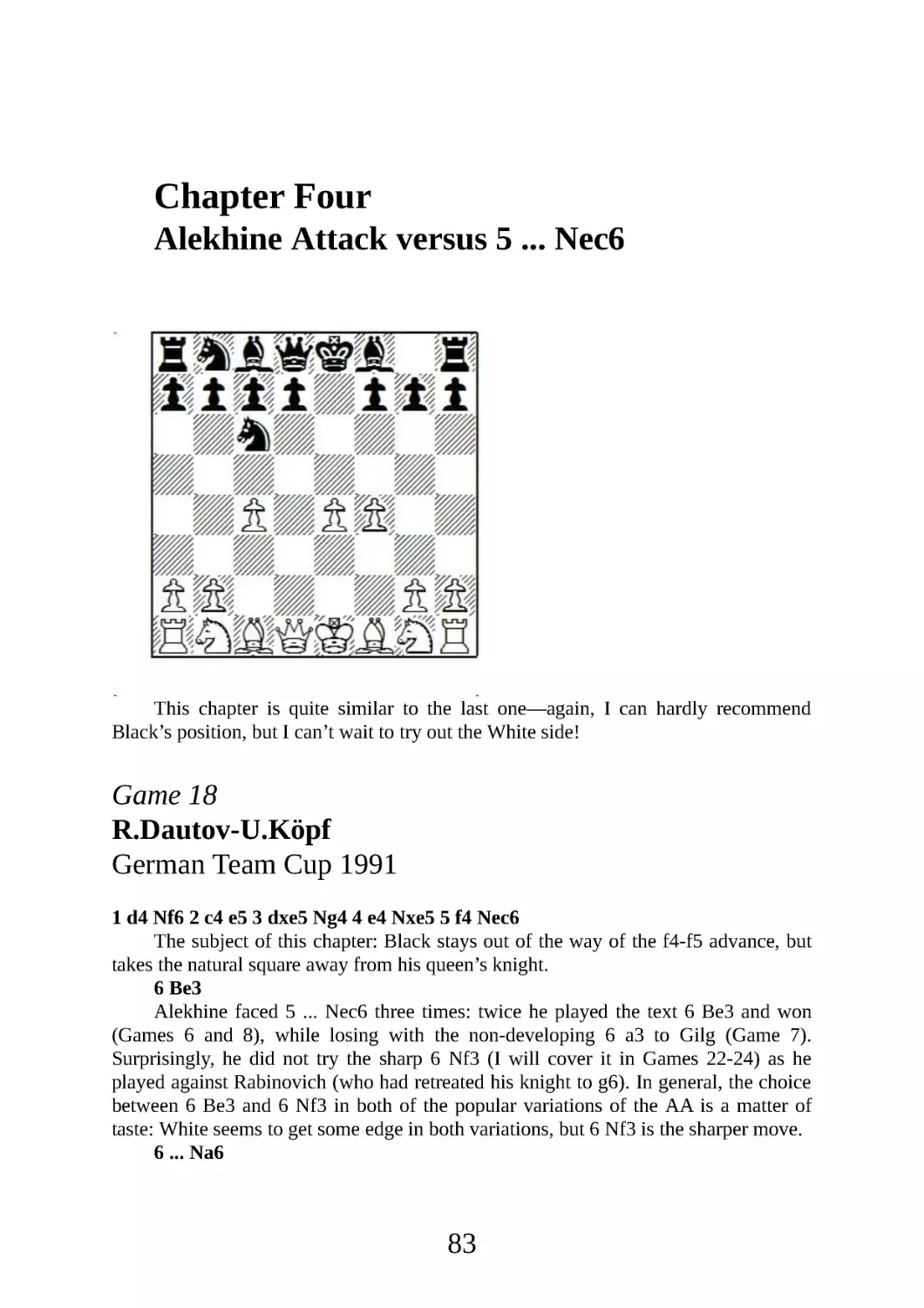

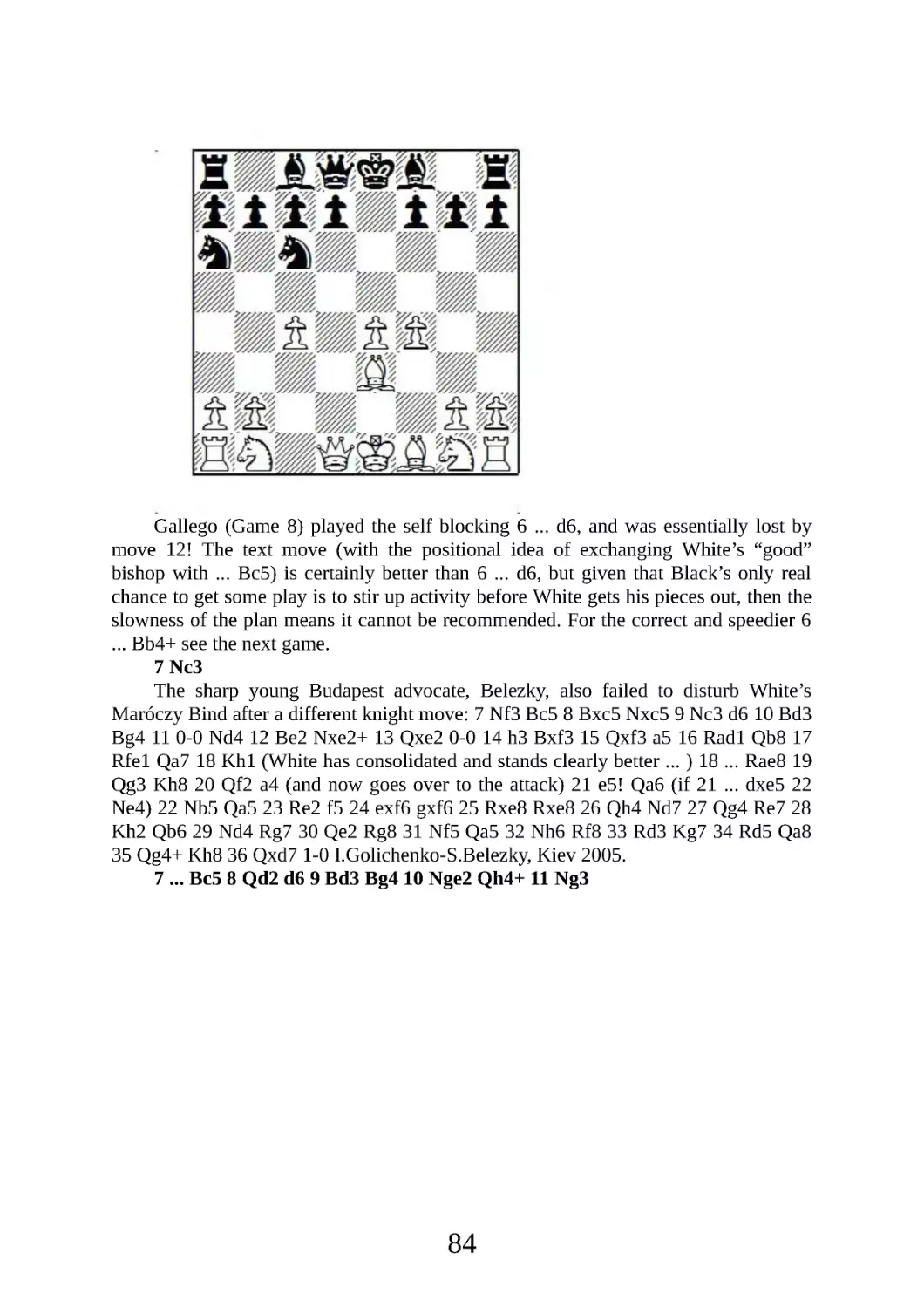

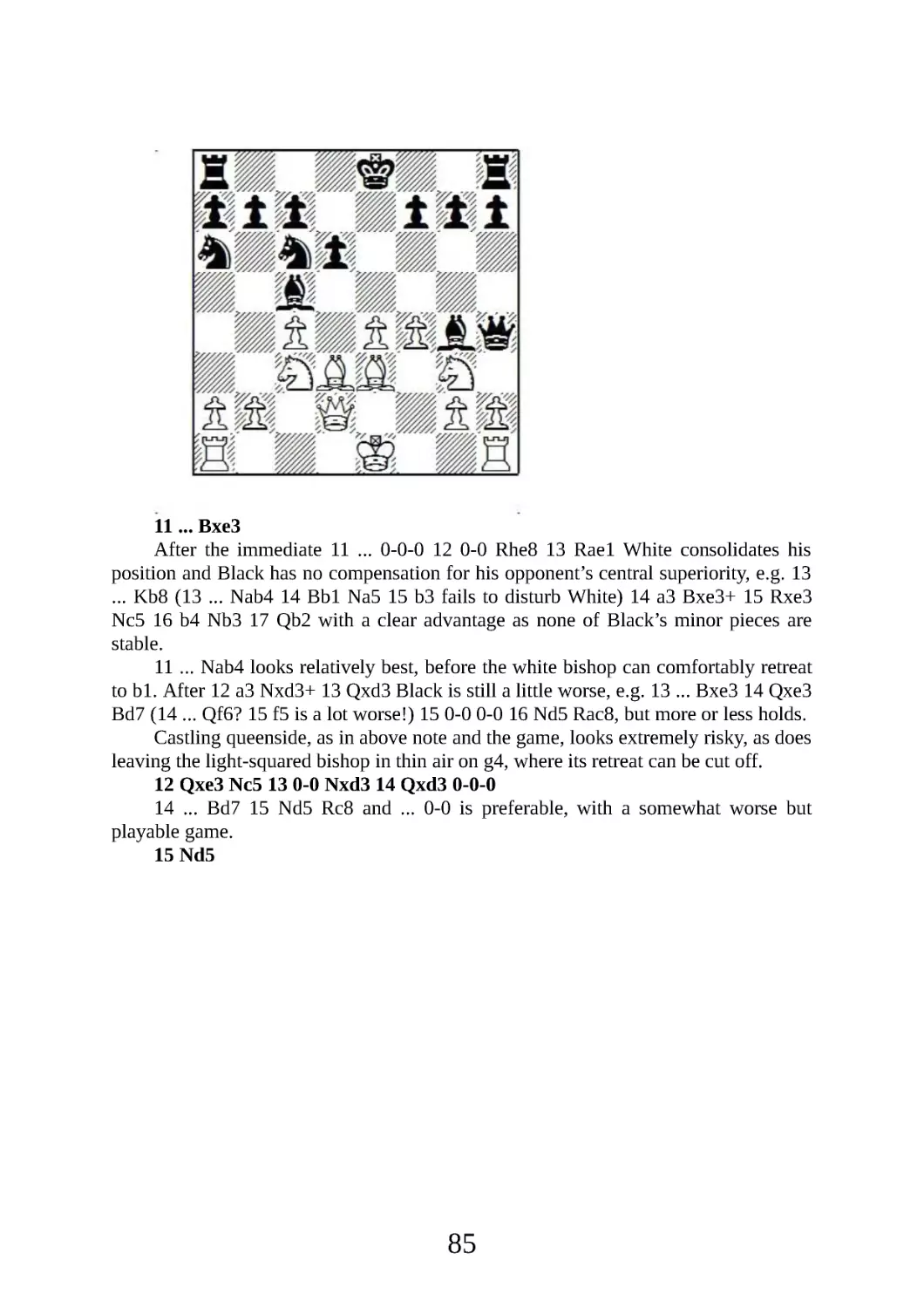

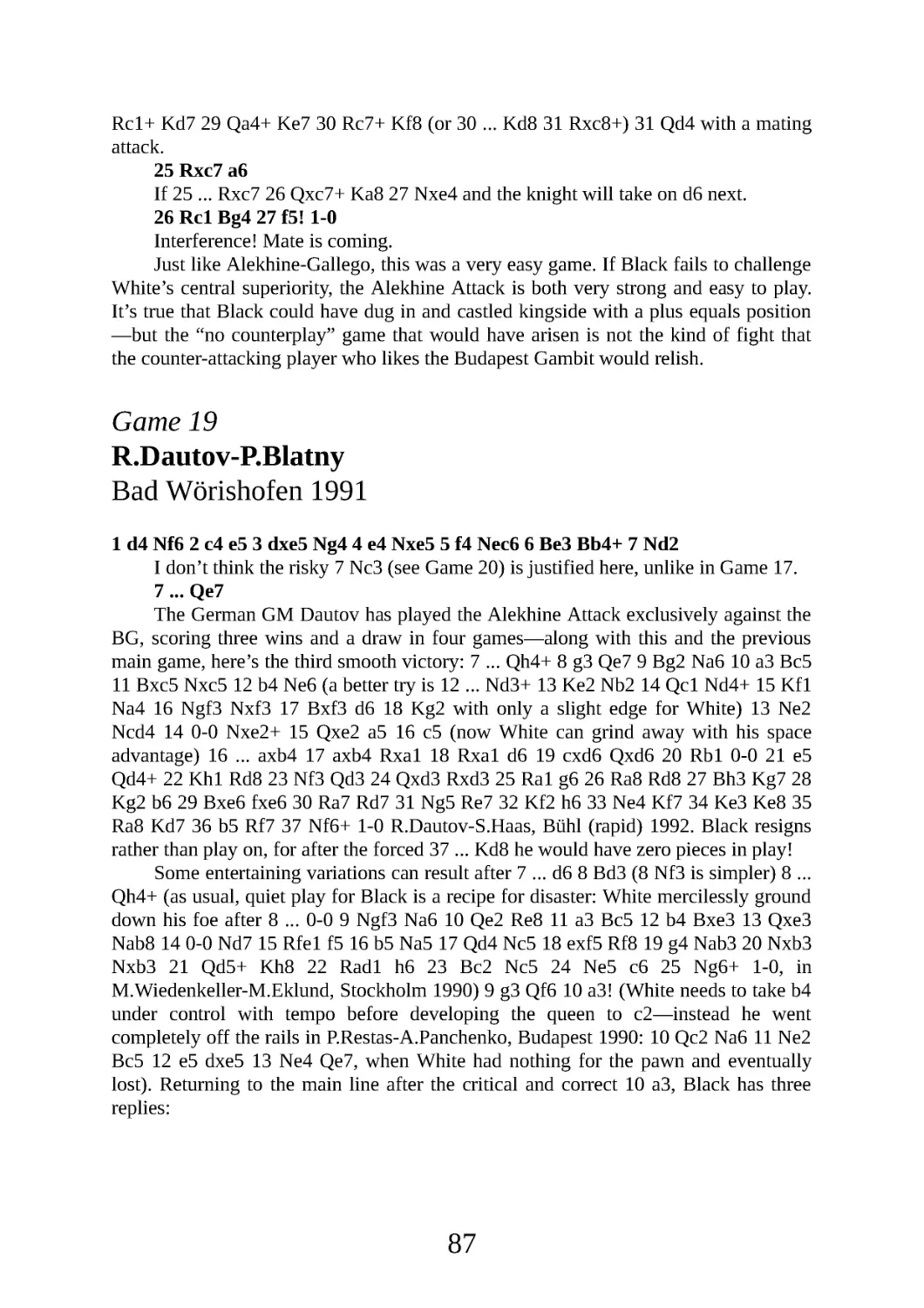

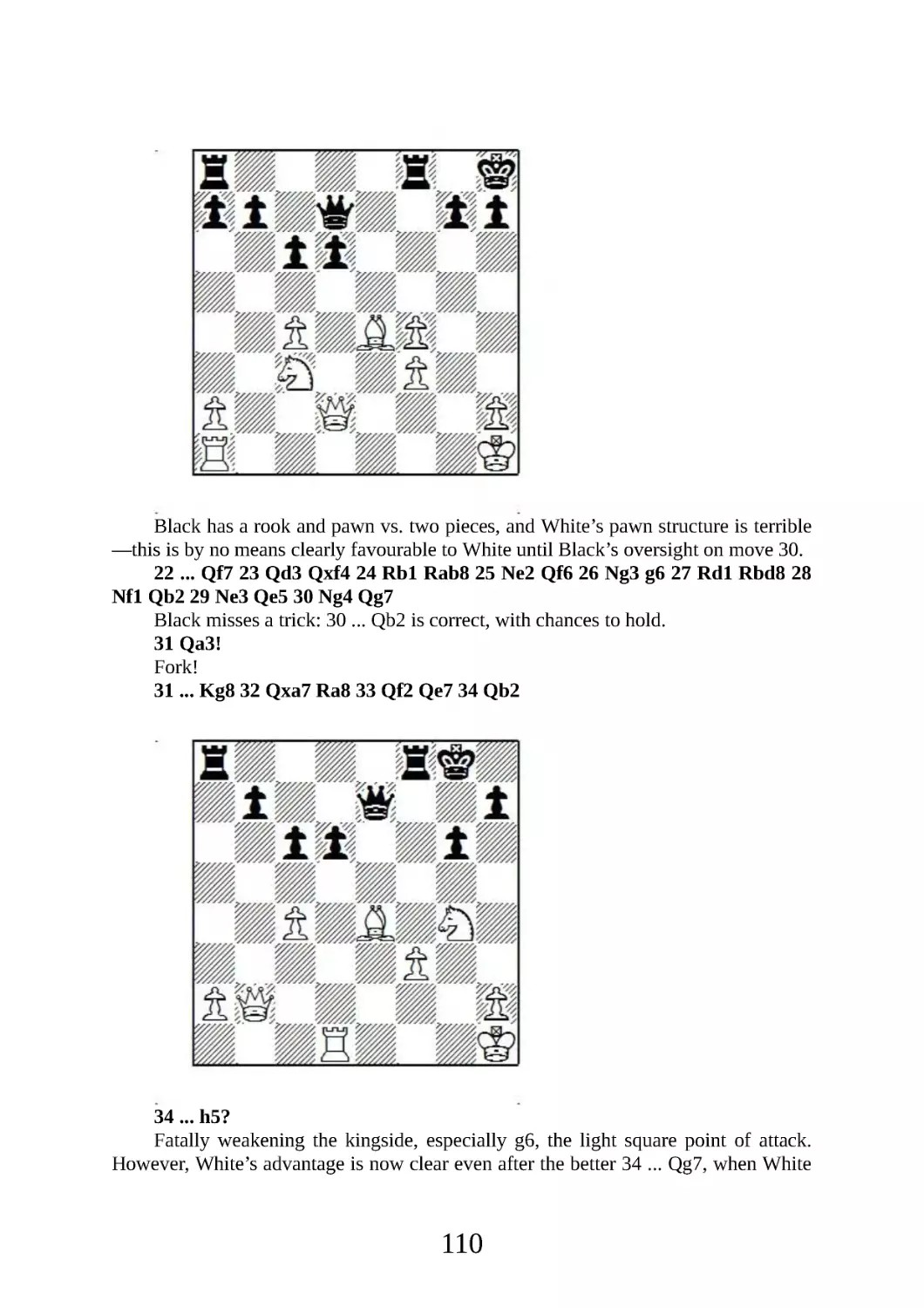

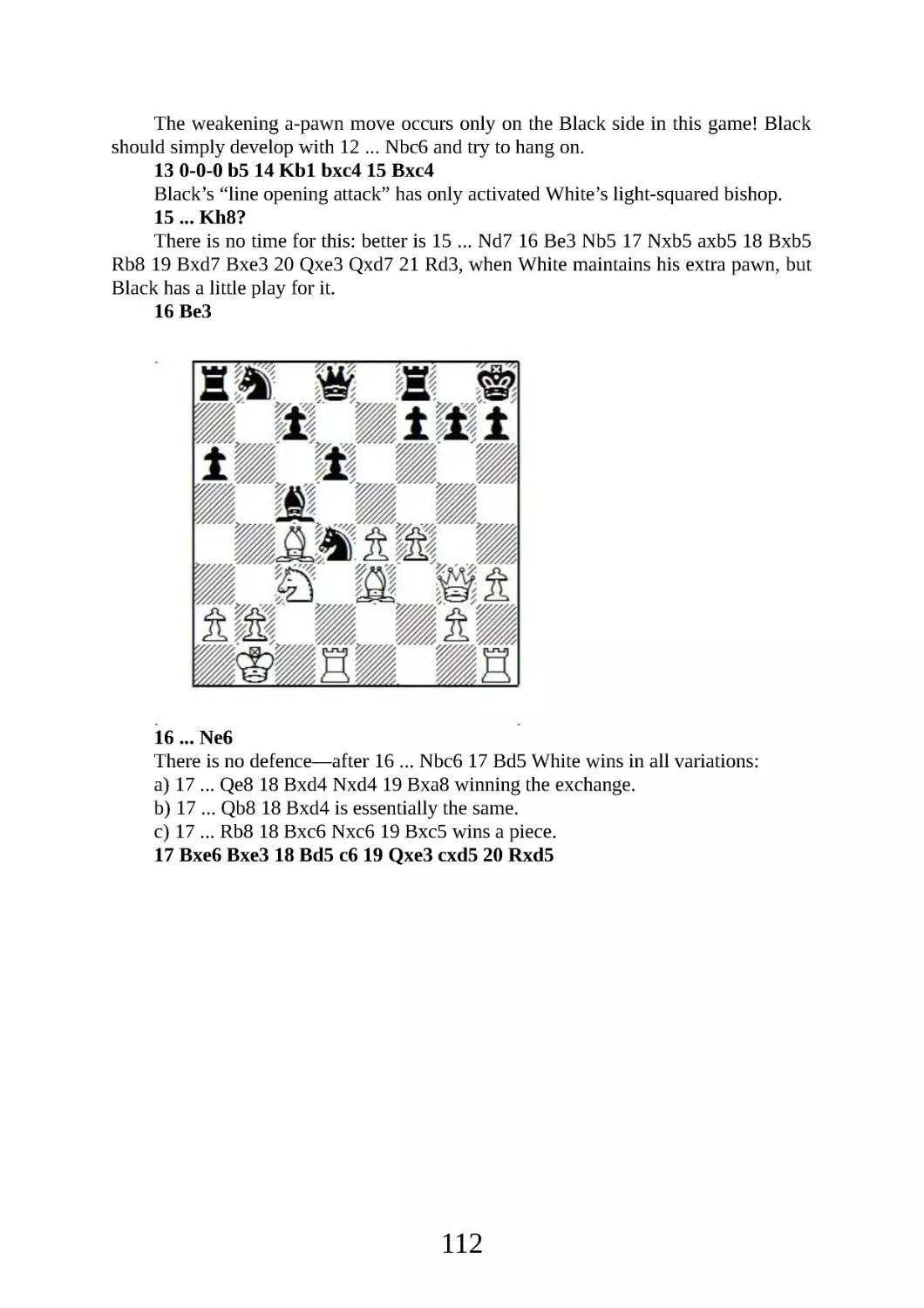

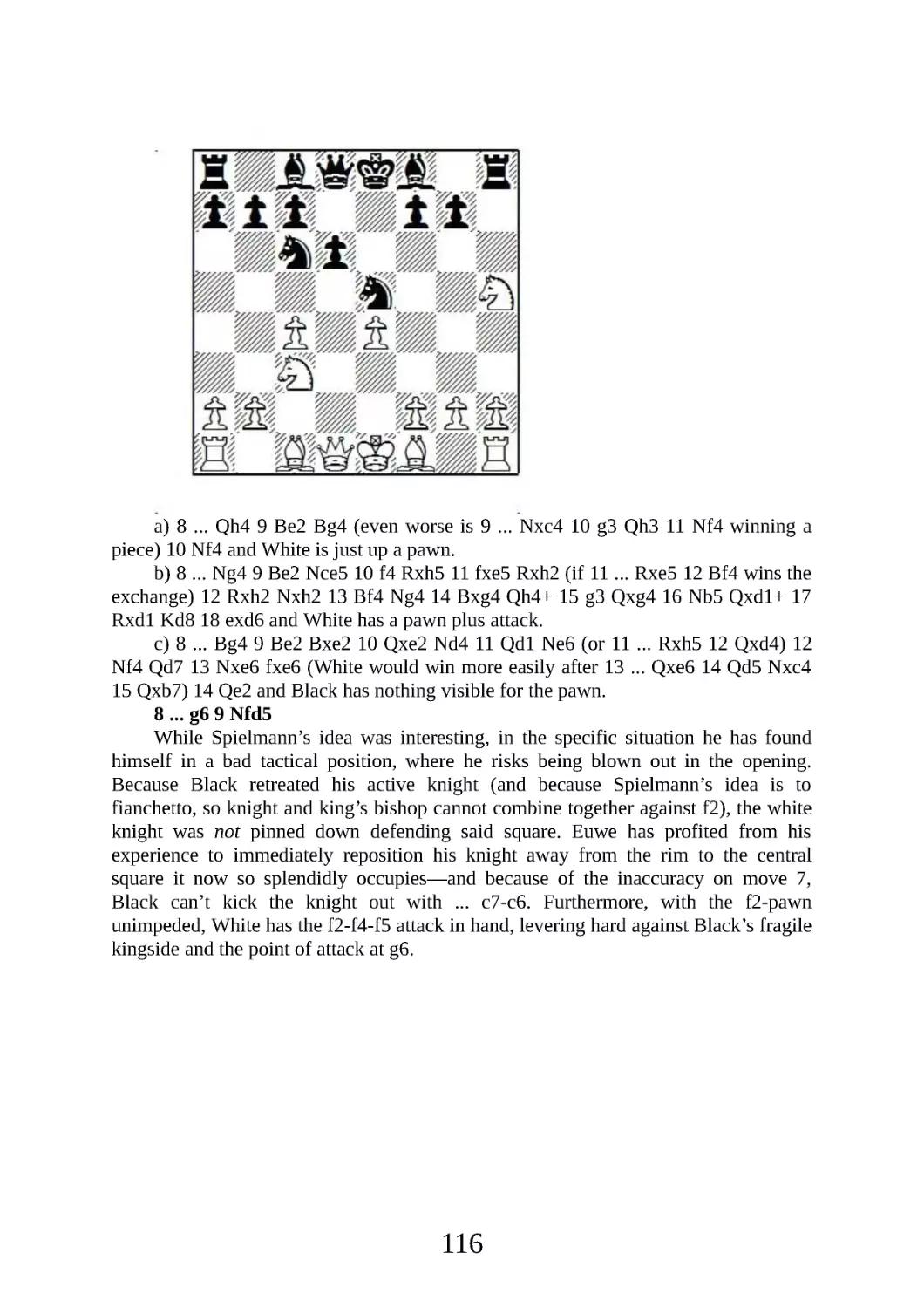

This fine win shows the accuracy demanded of both sides in the Alekhine Attack.