Текст

ПГ1117

SAN FRANCISCqjl^L^ LIBRARY^

3 1223 000907395 "Y" "W

Л1L SIC

HUNTER

The autobiog hy of a career

Laura Boulton

т.м.н.

$8.95

THE MUSIC HUNTER

I лига Boulton

Illustrated with photographs

Through the language of 'music Laura

Boulton became ambassador to the world;

through the vocabulary of song she made '

friends wherever she went. “Bestowal of

gifts establishes contact/’ she observes, “a -

sharing of music inspires trust. This bears

out what I have always believed: that r

music is the one perfect form .of com- /

munication that knows no barriers.”

The Music Hunter is the story of the

daring search by a noted musicologist to

discover and record the traditional and

liturgical music of people living in little

known parts of the world. From the

frozen wastes of the Arctic to Voodoo

ceremonies in Haiti, from the snow-

capped mountains of Nepal to initiation

rites in Africa, from Tibetan lamasaries

to the Penguin Islands, and from the

courts of kings to the huts of peasants,

Dr. Boulton took her intrepid way.

“In every instance,” she explains, "my

object was the same: to capture, absorb

and bring back the world’s music; not the

music of the concert hall or the opera

house, but the music of the people, their

(continued on back flap)

(continued from front flap)

expression in songs of sadness and joy,

their outpourings in times of tragedy and

times of exaltation.”

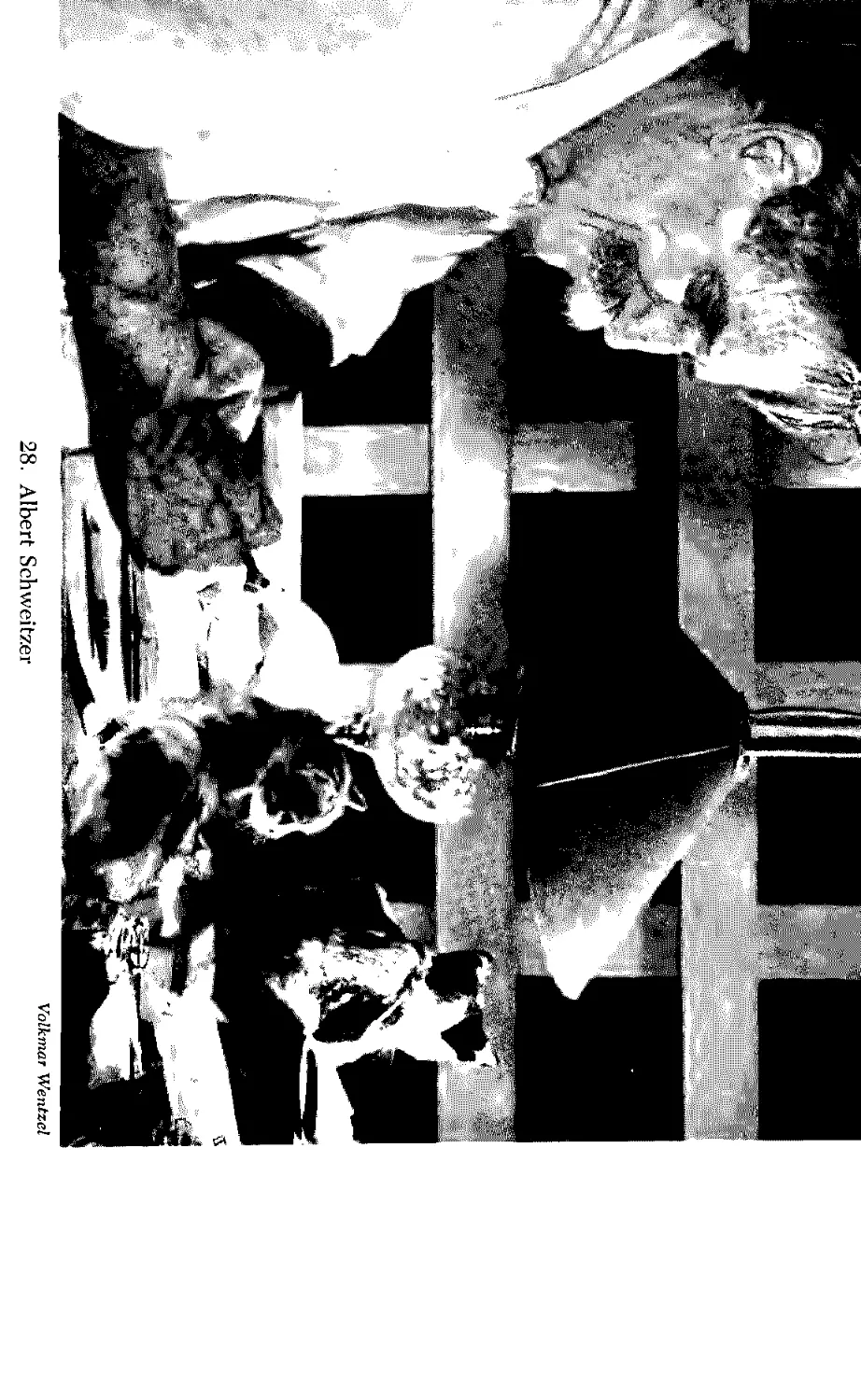

During thirty-five years o£ journeying,

she felt equally at home as a guest of

great personalities like Dr. Albert

Schweitzer, Prime Minister Nehru, Em-

peror Haile Selassie or with natives hid-

den away in the jungles, the mountains

or the icy tundra. And her travels, of

course were enriched by more than music

—an understanding of the folkways of

peoples, their traditions, th air struggles

for survival, the hopes and fears which

are the wellspring of music everywhere.

An index will help readers to follow

these twenty-eight extraordinary safaris.

PHOTO BY ARA GULER

Laura Boulton is the Director of the Re-

search Project on World Music and Di-

rector of the Laura Boulton Collection of

Traditional and Liturgical Music in the

School of International Affairs at Colum-

bia University.

JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY WILL ROUSSEAU

Printed in the U.S.A.

THE MUSIC HUNTER.

THE MUSIC HUNTER

The Autobiography of a Career

by Laura Boulton

Doubleday & Company, Inc.

Garden City, New York

^9

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 67-11154

Copyright © 1969 by Laura C. Boulton

All Rights Reserved

Printed in the United States of America

First Edition

My IHM&r wj My Ж&зг

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am greatly indebted to an unbelievable number of individuals

and governments around the world for their help and cooperation.

Although it is not possible to list them, I want to express here

my heartfelt thanks to all of them.

For substantial grants and fellowships and for inspiring sponsor-

ship I want to express my deep appreciation to the following:

Foundations: American Council of Learned Societies; American

Philosophical Society; Carnegie Corporation of New York (2

grants); East and West Foundation; Phelps Stokes Fund; Wenner-

gren Foundation.

Universities, Museums, and Organizations: American Museum

of Natural History; Carnegie Museum; Field Museum; Columbia

University; Harvard University; Tulane University; University of

California; University of Chicago; University of Washington;

UNESCO.

I am also deeply grateful to many individuals who have

sponsored expeditions or have generously assisted my research,

especially the following:

Mrs. Anne Archbold; Mr. and Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss; Mrs.

W. Murray Crane; Mrs. Lydia Foote; Mr. Chauncey Hamlin;

Mrs. H. H. Jonas; Mrs. John H. Leh; Mr. Leon Mandel; Mr. and

Mrs. Ralph Pulitzer; Dr. and Mrs. George Shattuck; Mrs. Oscar

Straus; Mrs. Margaret Pope Walker.

I also want to express my appreciation for the privilege of

writing portions of this book surrounded by the peace and beauty

Vlii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

of the MacDowell Colony, N. H. and on the estates of kind and

interested friends: Mrs. Anne Archbold, Nassau; Mrs. Louis An-

spacher, Purchase, N.Y.; Mr. and Mrs. Zlatko Balocovic, Camden,

Maine; Frances and Alexander McLanahan, Chateau de Missery,

Cote d’Or, France.

I also want to express my thanks to the experts from various

countries who have taken time to read these chapters and have

given valuable comments.

For the constant aid of assistants and secretaries, I am particu-

larly grateful, especially for the invaluable help and suggestions

of Elizabeth Webb who encouraged me in my occasional moments

of despair while choosing and eliminating material.

My deep gratitude goes to Dean Andrew Cordier for the

stimulating cooperation he has given me and for the sympathetic

Introduction he has written for this book.

I would like to express warmest thanks to Ken McCormick,

editor-in-chief of Doubleday, for his valued help and infinite

patience.

For his expert editorial assistance my eternal gratitude goes to

John Ardoin.

To Mrs. Oscar Straus I am most indebted for starting me in

this career.

To Mr. Julian Clarence Levi through whose wisdom and

generosity our research center for World Music at Columbia

University was established and continues to grow my gratitude

is boundless.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments vii

Introduction xiii

SECTION I: AFRICA

1. The Beginning 3

2. Up the Nile to the Mountains of the Moon and Kenya 7

3. Tanganyika’s Mystery Mountain 21

4. Nyasaland to Capetown 40

5. Angola: Gateway to Portuguese West Africa 57

6. The Ovimbundu of Angola 68

7. From Timbuktu to the Cameroons 88

8. Bronze Artists of Benin 110

9. Songs and Instruments of Jungle and Bush 121

10. Through South West Africa: Wasteland, Wonderland 137

11. Coming of Age in Ovamboland 150

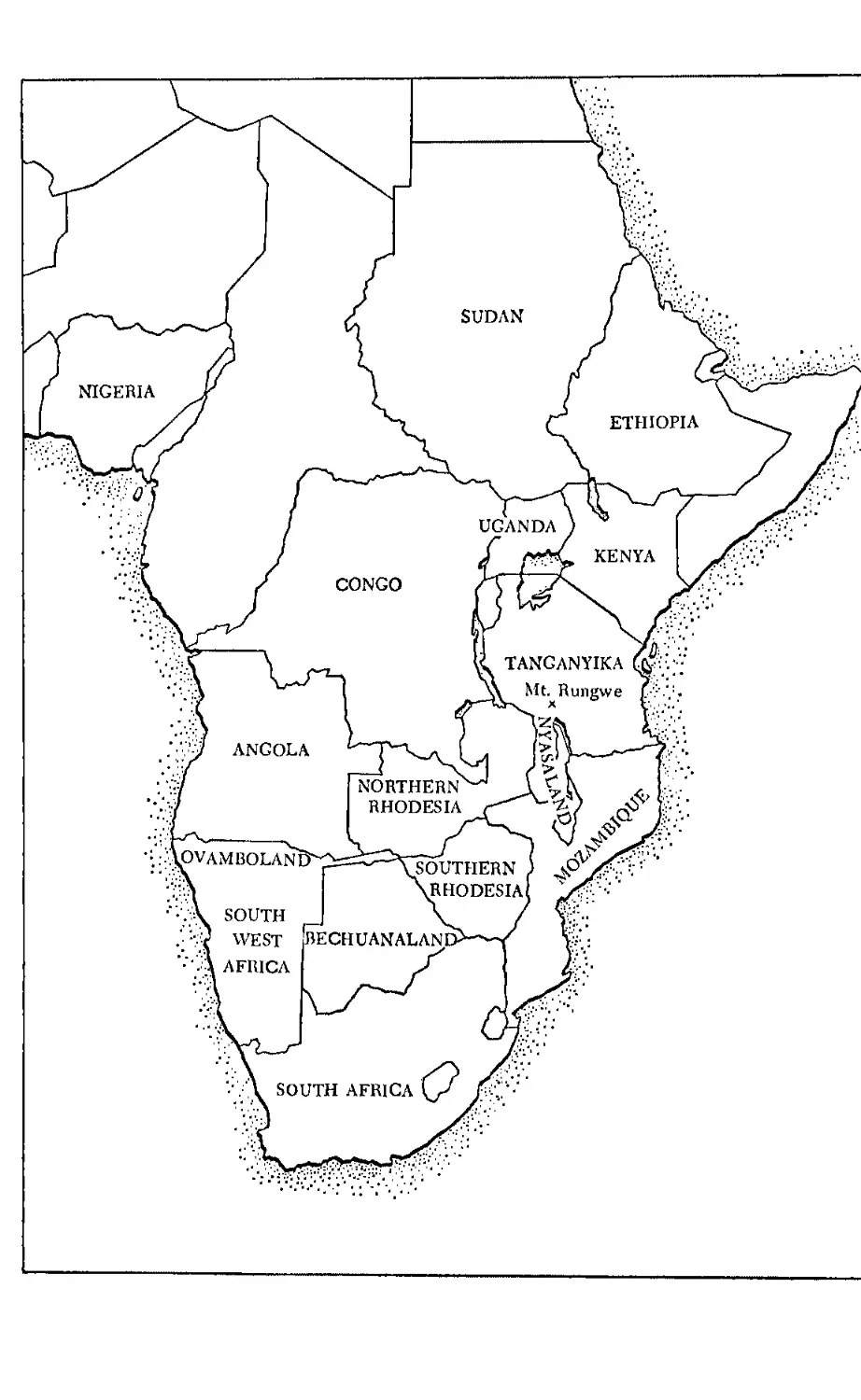

12. Bushmen of the Kalahari 167

13. Albert Schweitzer: Twentieth-Century Saint 180

SECTION П: THE EAST

14. The Pageant of India 197

15. Tibetan Magic and Mysticism 222

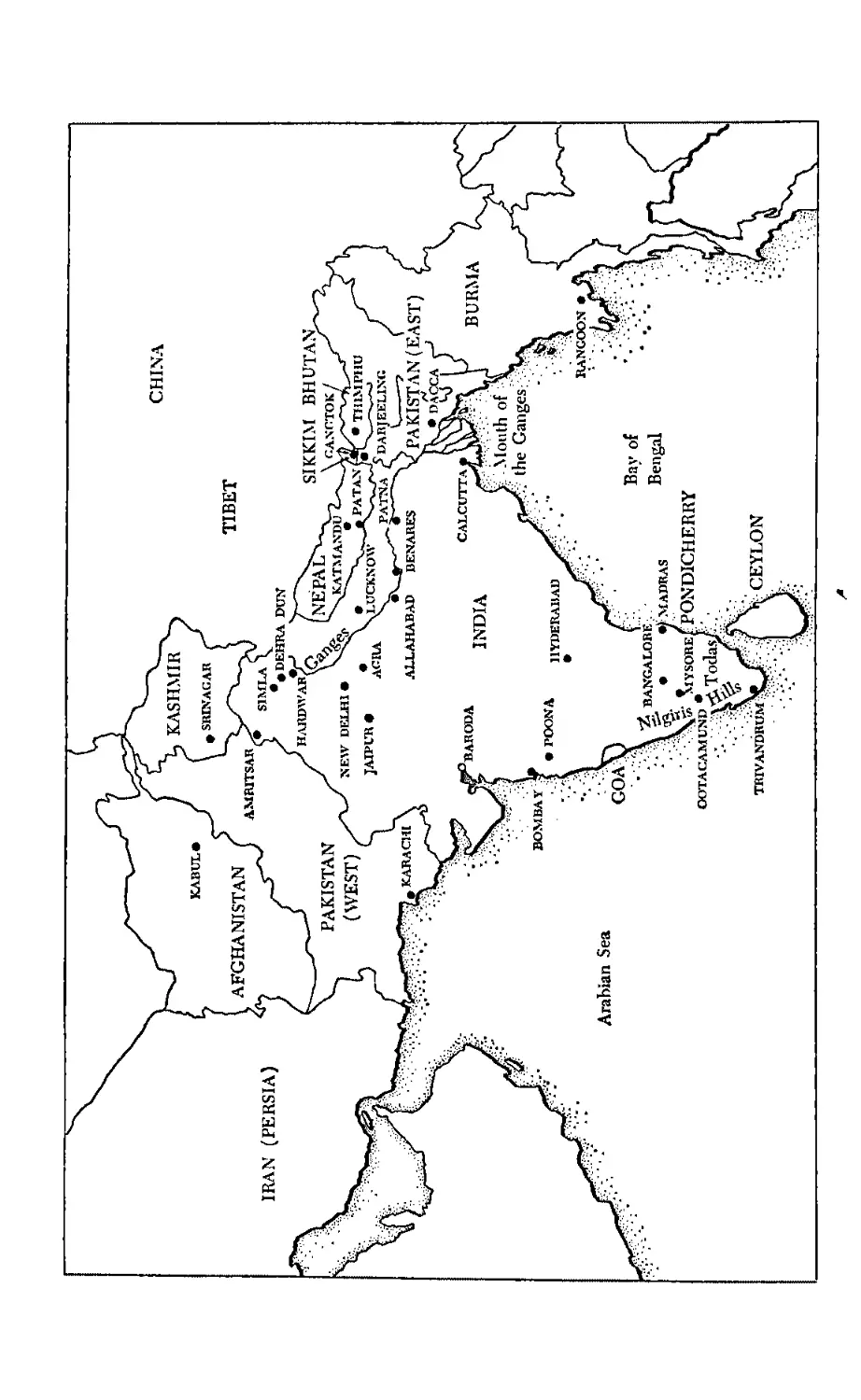

16. The Hermit Kingdom of Nepal 235

17. Cave Council in Burma 255

18. Southeast Asia: Indochina and Siam 265

ig. Southeast Asia: From Bali to Borneo 289

20. To the Far East 3°9

21. Japanese Sojourn 327

X

CONTENTS

SECTION III: THE AMERICAS

22, To the Eastern Arctic In Convoy 345

23. Eskimos of the Eastern Arctic 3®5

24. Flight to the Alaskan Arctic З^1

25. The Queen Charlotte Islands and the Northwest

Coast Indians 393

26, Indians of Our Southwest 411

27. The First Mexicans 431

28. African Survivals in the New World 445

' \

SECTION IV: EUROPE

У 29. Gypsies in the Mountains of Hungary 455

30. Balkan Experiences 470

31, A Glimpse into Byzantine and Orthodox Music 480

SECTION V; AFRICA

32. Africa Revisited—Ethiopia 491

Epilogue 502

Appendix 504

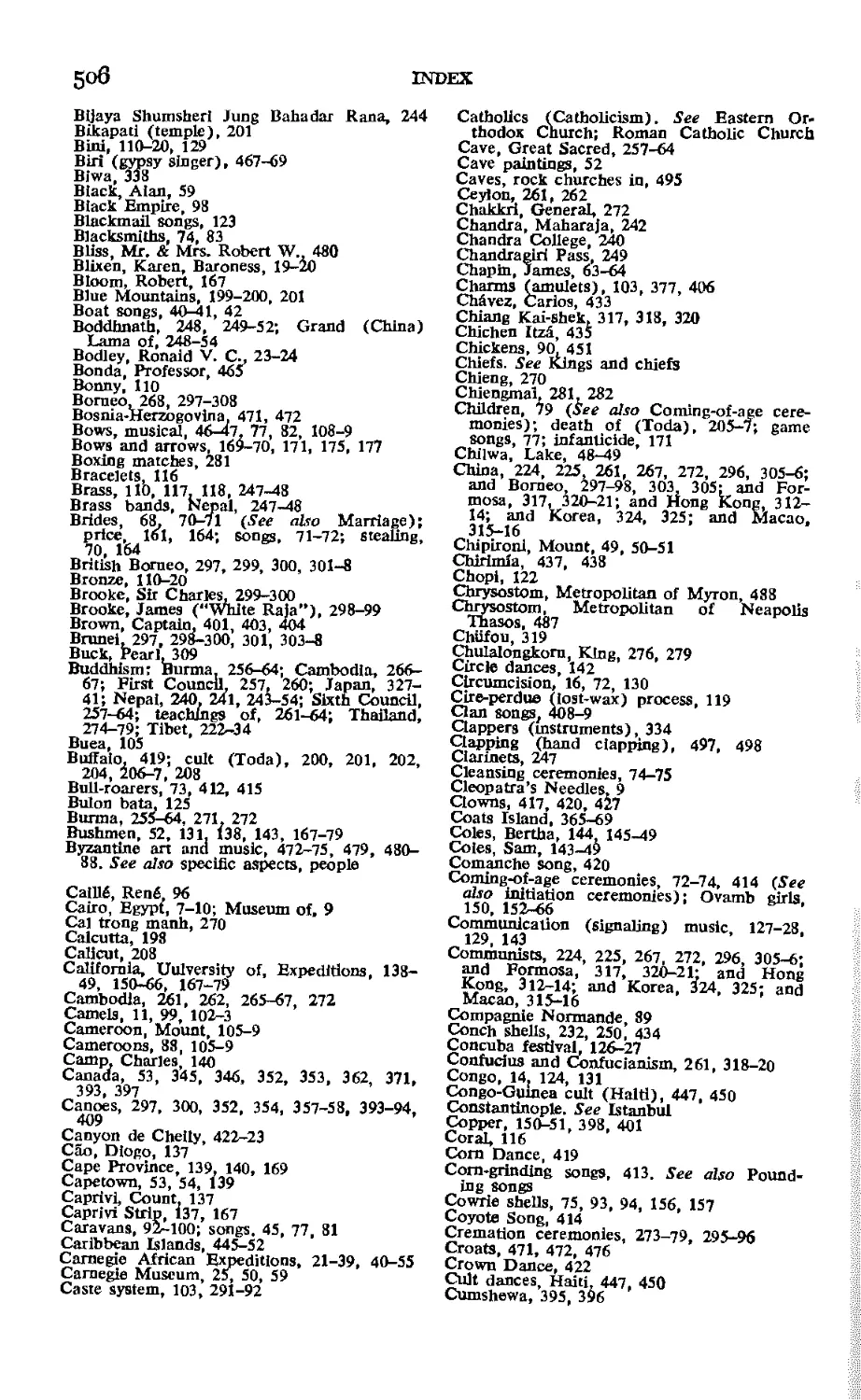

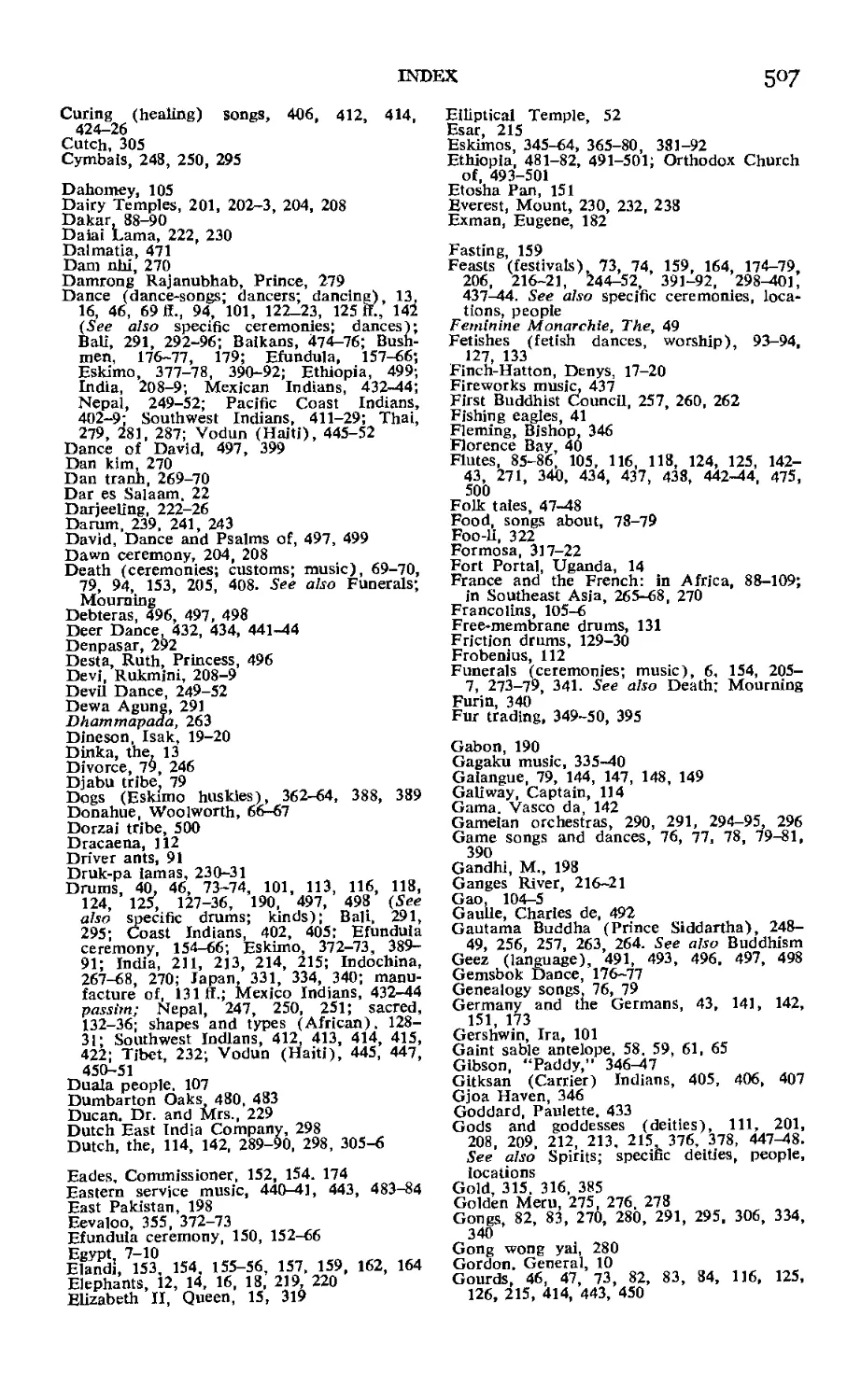

Index 505

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

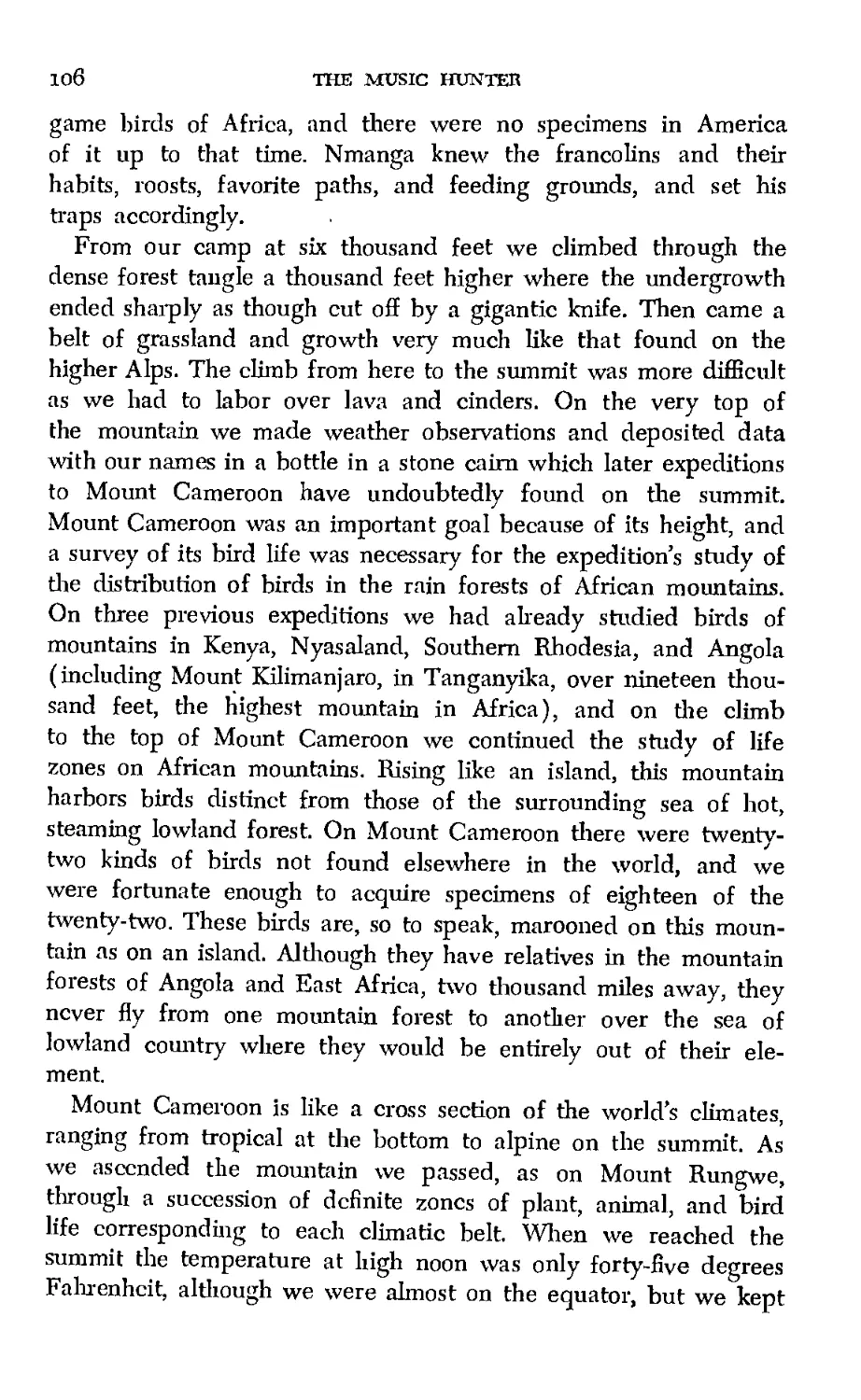

1. The author, Mrs. Straus, her grandson, and Denys Finch-Hatton,

at lunch

2. Wamjabaregi and boys, Mount Rungwe, Tanganyika

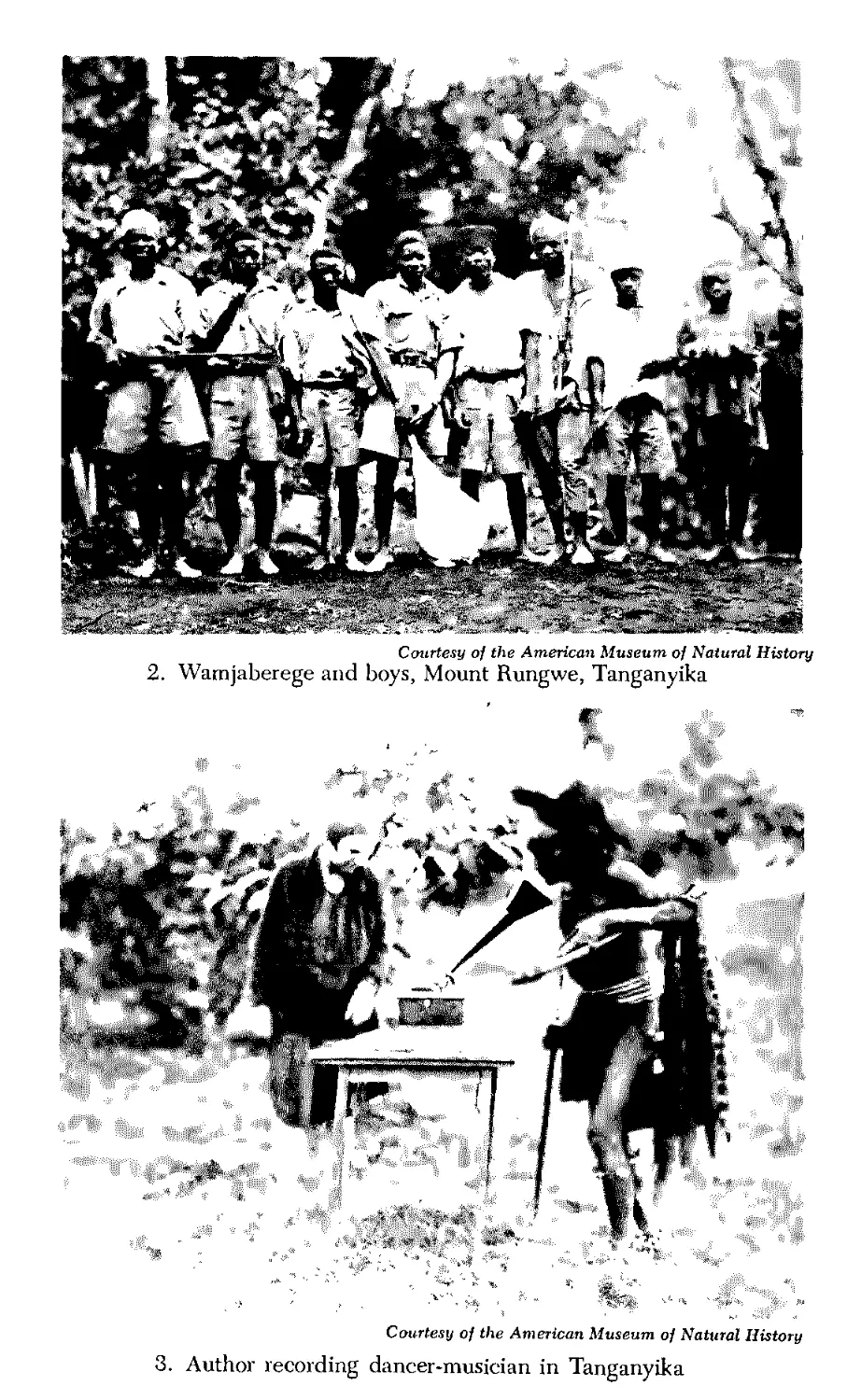

3. Author recording dancer-musician in Tanganyika

4. Author feeding Shoko

5, Puzi nursing Shoko

6. Pulitzer party at lunch, Angola

7. Iloy-Iloy, author’s tribal sister, Angola

8. Recording royal flute, Angola

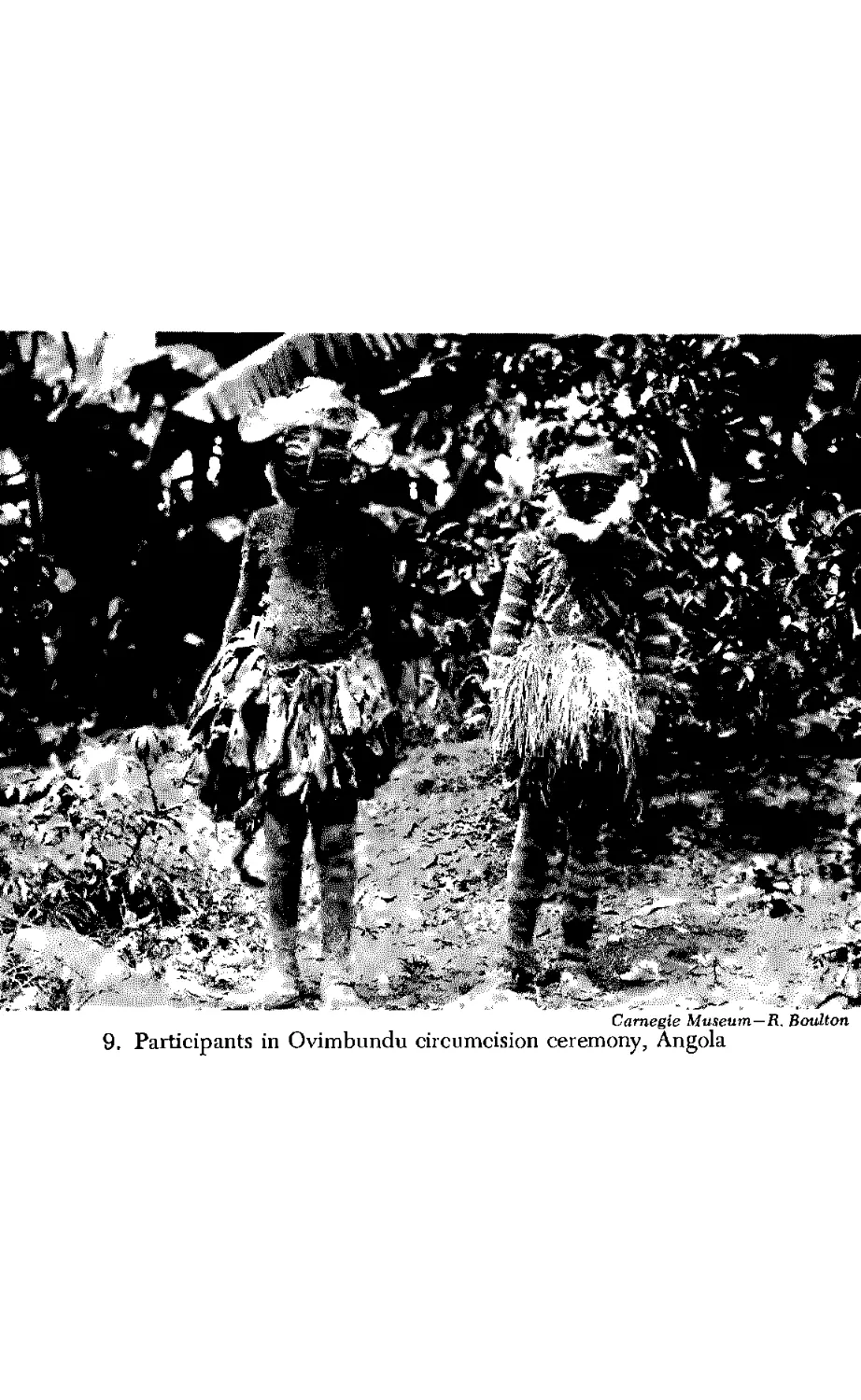

9. Participants in Ovimbundu circumcision ceremony, Angola

10. Yakouba, White Monk of Timbuktu

11. The author with the famous ineharists (camel corps) near Timbuktu

12, Sixty-five yards in seven hours in the Sahara

13. Recording Tuaregs in Timbuktu

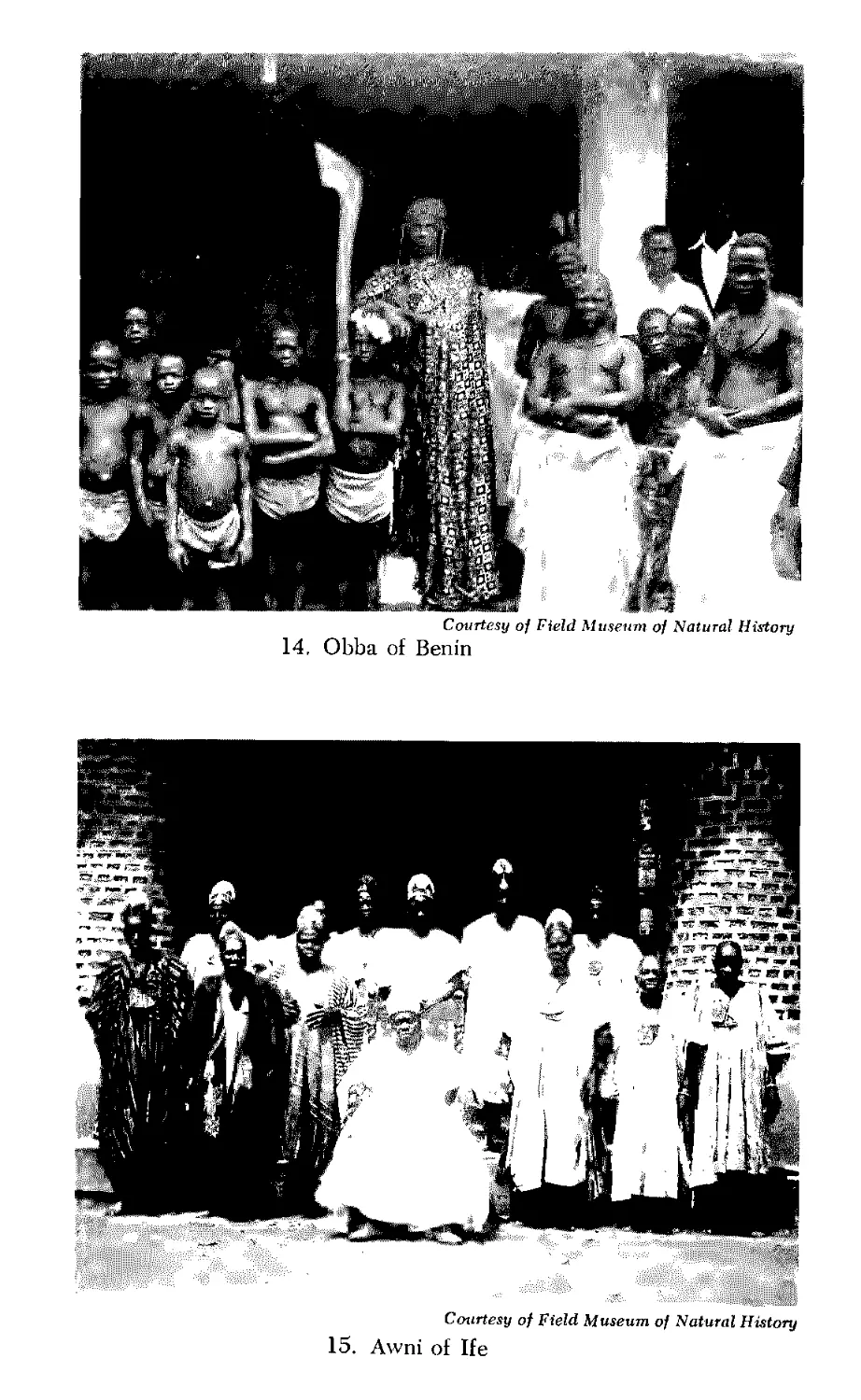

14, Obba of Benin

15, Awni of Ife

16. Obba’s musicians

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

XI

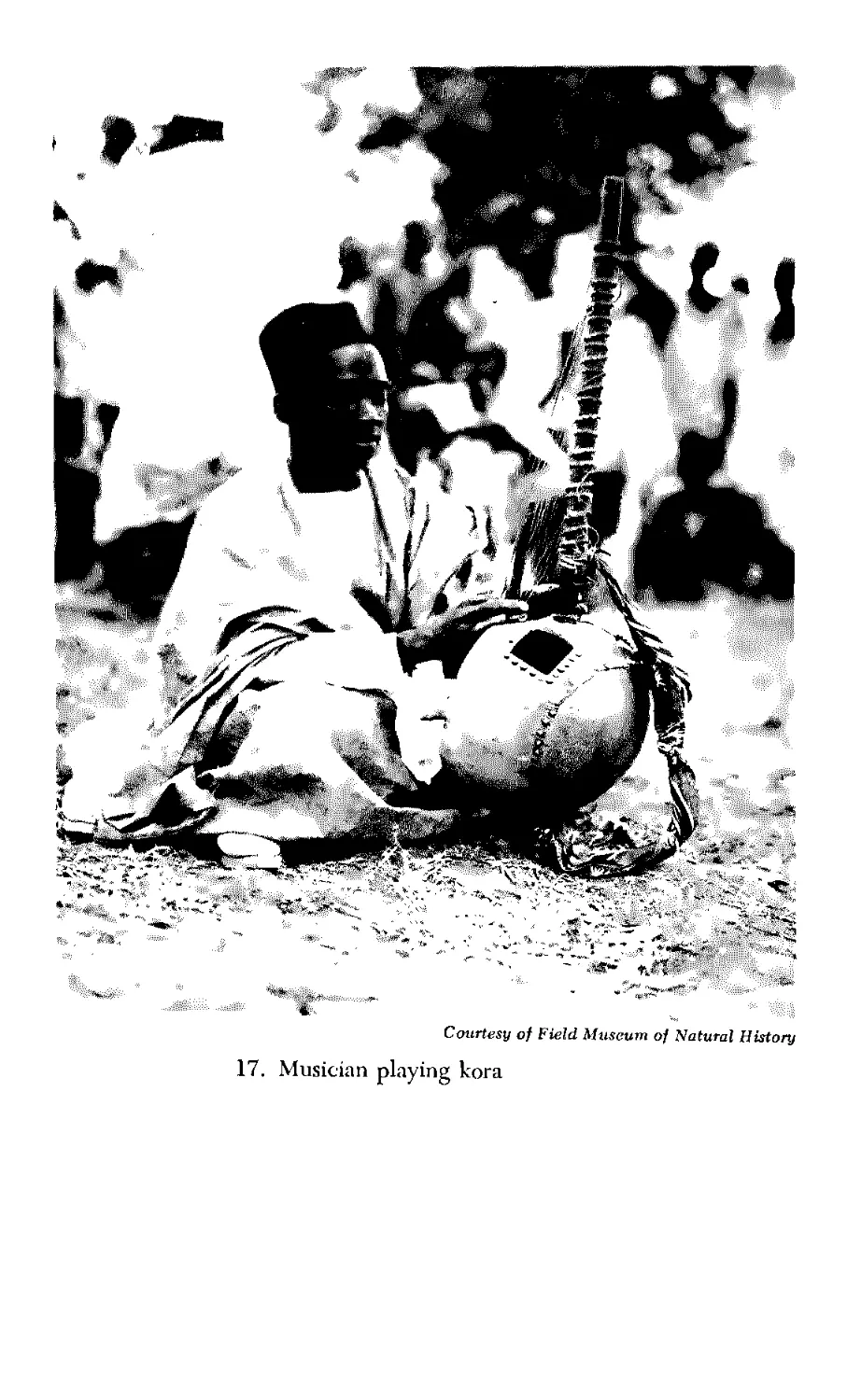

17. Musician playing kora

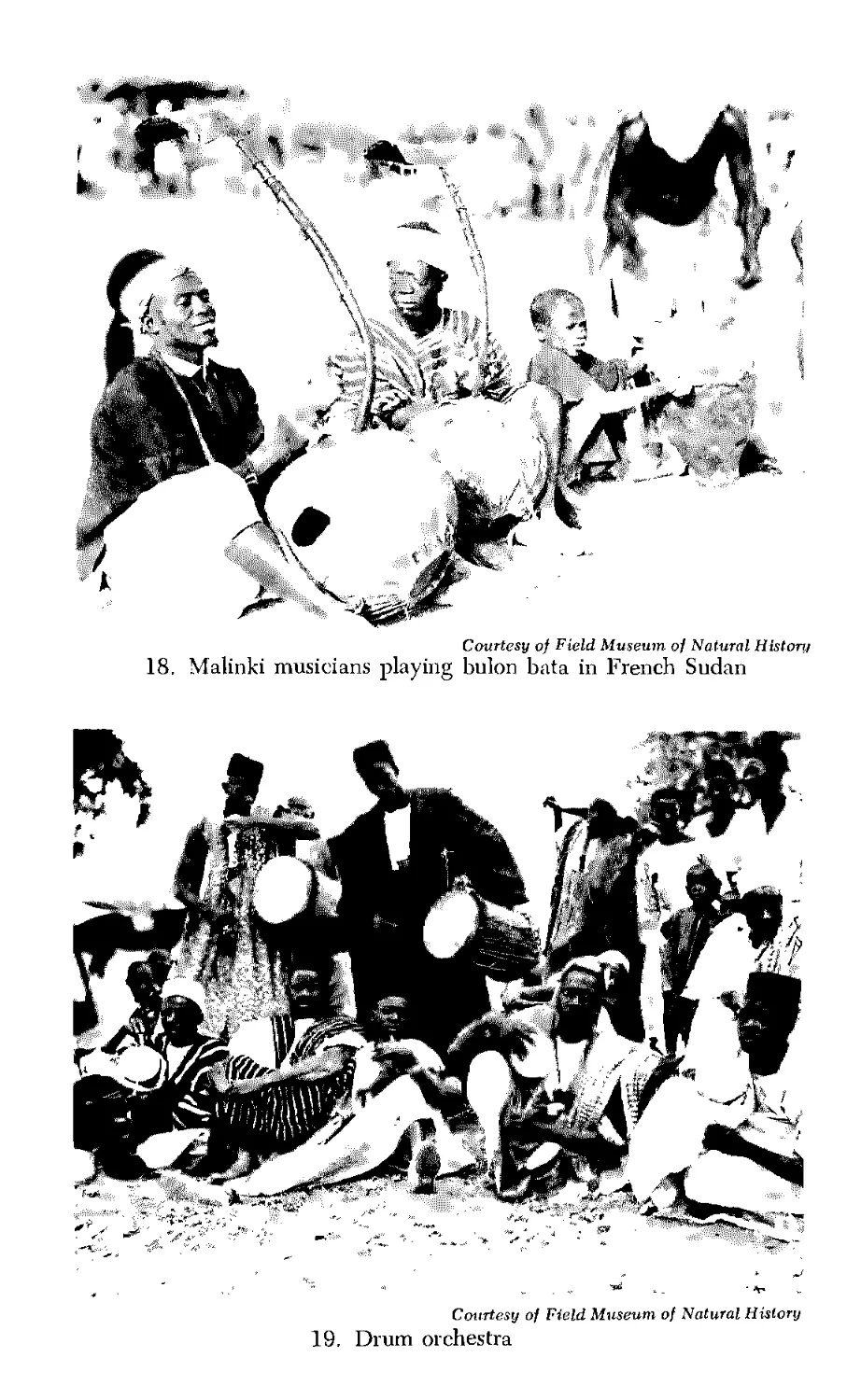

18. Malinki musicians playing bulon bata in French Sudan

19. Drum orchestra

20- A gubu player with musical bow

21. Curved xylophone and singers, Angola

22. Sam Coles, “Preacher with a plow”

23. Woman seeing her own face for first time

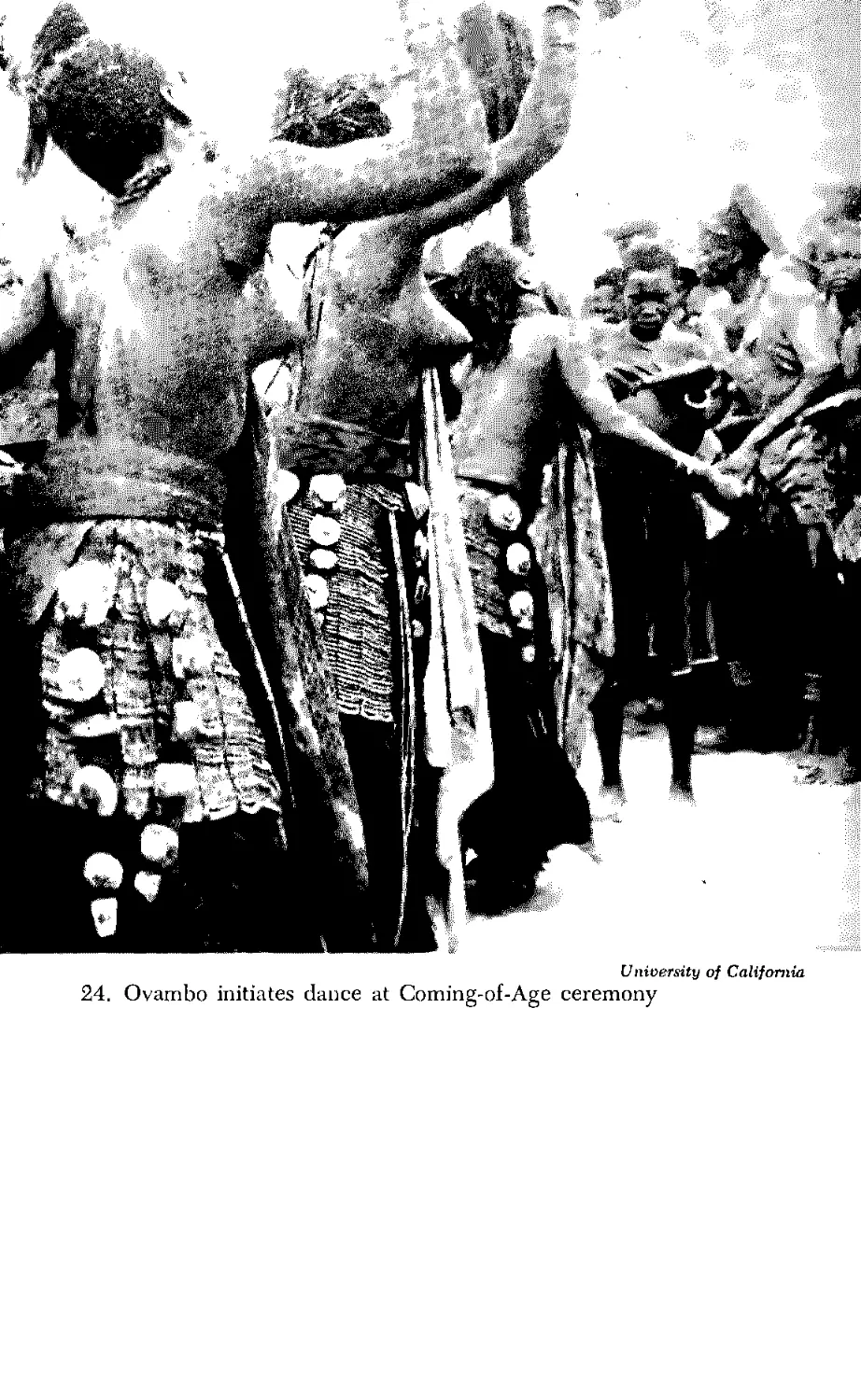

24. Ovambo initiates dance at Coming-of-Age ceremony

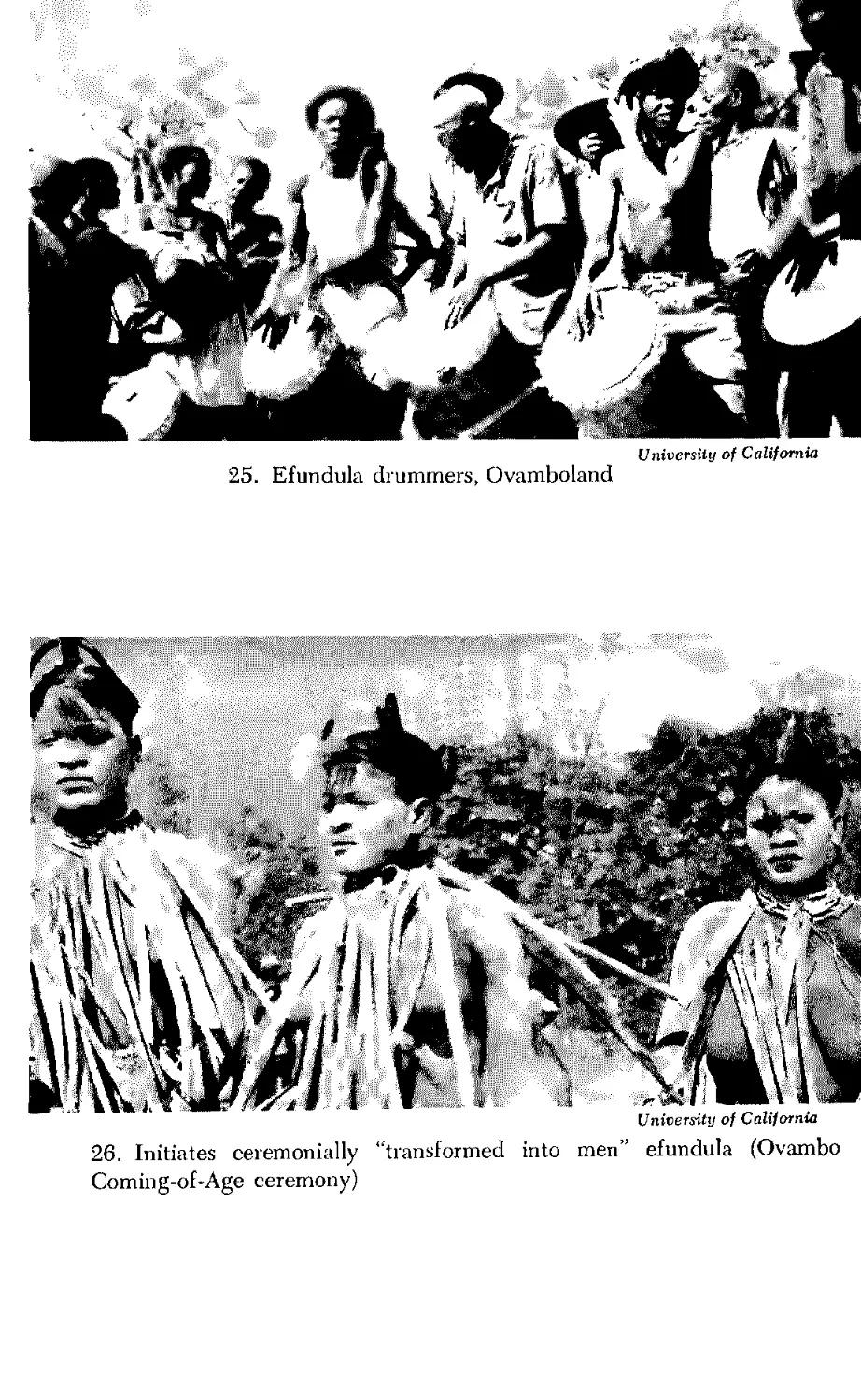

25. Efundula drummers, Ovamboland

26. Initiates ceremonially “transformed into men” efundula (Ovambo

Coming-of-Age ceremony)

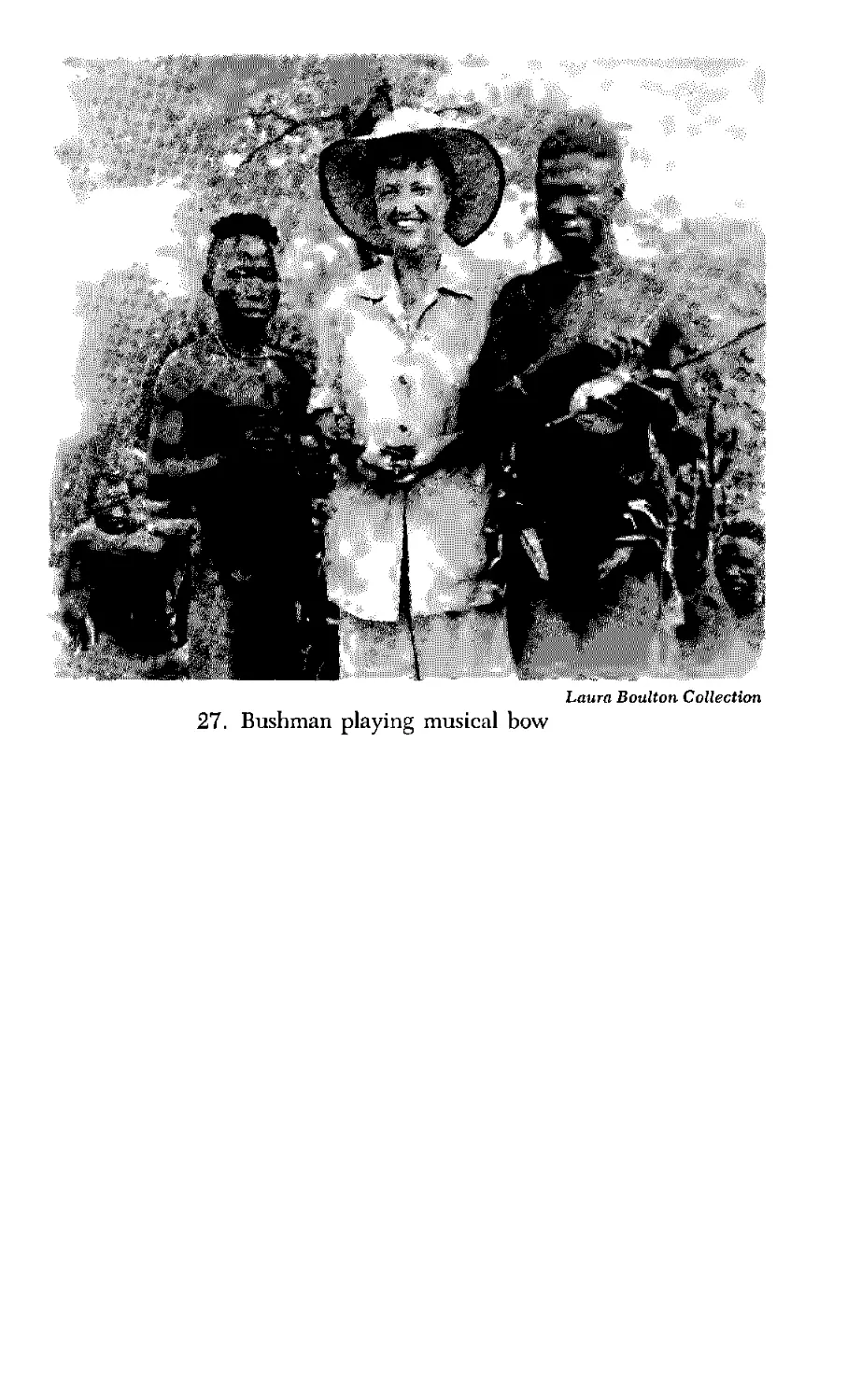

27. Bushman playing musical bow

28. Albert Schweitzer

29. Albert Schweitzer’s orderly playing primitive harp

30. Procession of holy men during the Puma Kumbha Mela (Um

Festival)

31. Millions of Hindus at Puma Kumbha Mela

32. Nilgiris Hills, Todas

33. Vina players in Mysore orchestra recorded by author

34. The author with her unpredictable Tibetan pony

35. Jigme Taring, Tibetan interpreter, and the daughter of the Raja of

Bhutan

36. Maharaja of Nepal

37. The Prince and his bride, Nepal wedding

38. The author recording the Yellow Lama and Tibetan lamas

39. Tibetan lamas’ Devil Dancers

40. Royal musicians and dancer, Angkor Wat, Cambodia

41. Mah-Sai, Thailand

42. Thai dancers

43. Balinese prince, host of author

44. Author with Dyak chief, Sarawak

45. The author in Korea with head of International Red Cross

46. On a glacier at Point Barrow

47. Peterhead in Hudson Bay

48. Eastern Arctic Eskimos on walrus hunt

49. Eevaloo making drum

50. Author recording Eskimo Drum Dance on Southampton Island

51. Sid Wien and passengers, Alaska

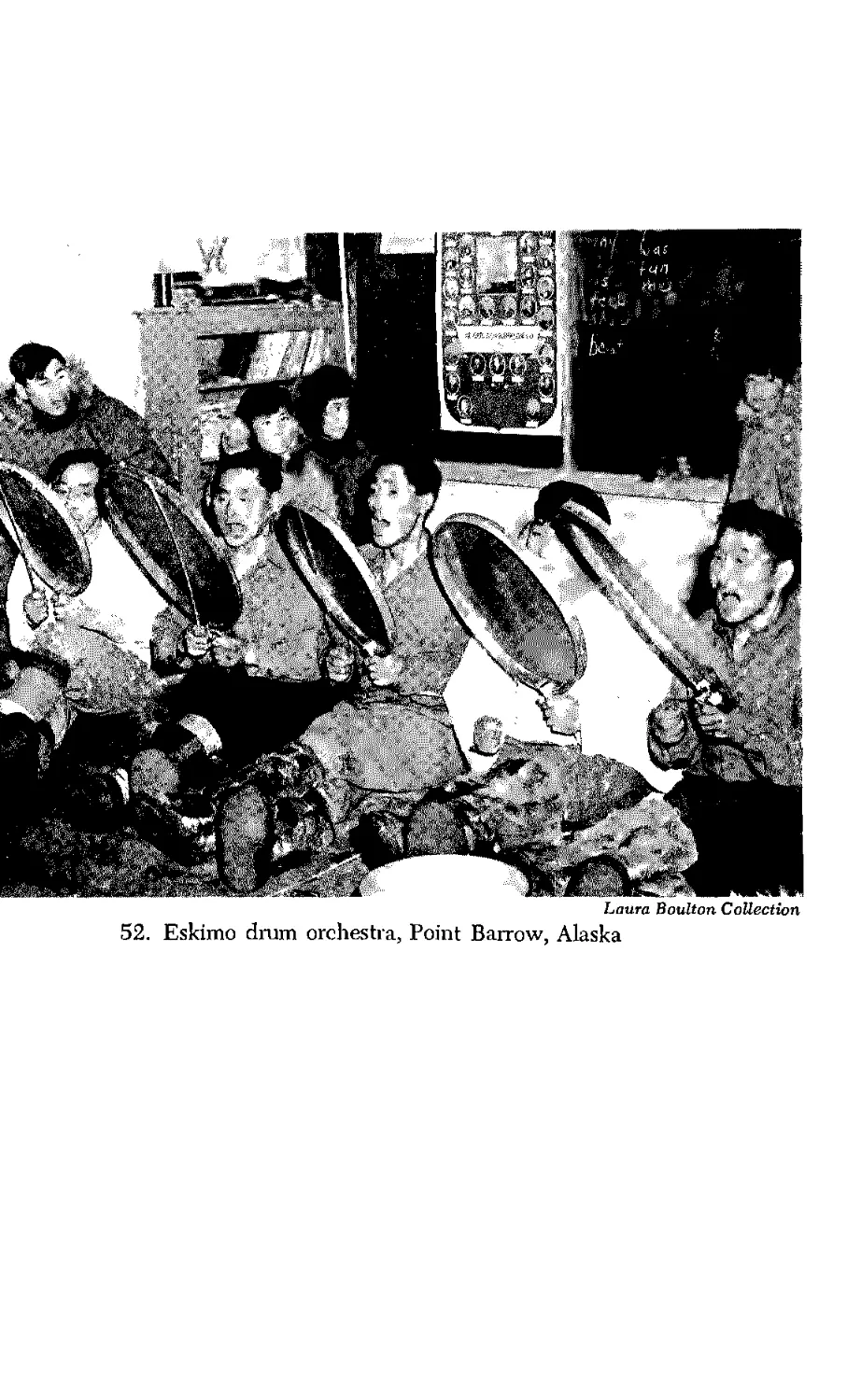

52. Eskimo drum orchestra, Point Barrow, Alaska

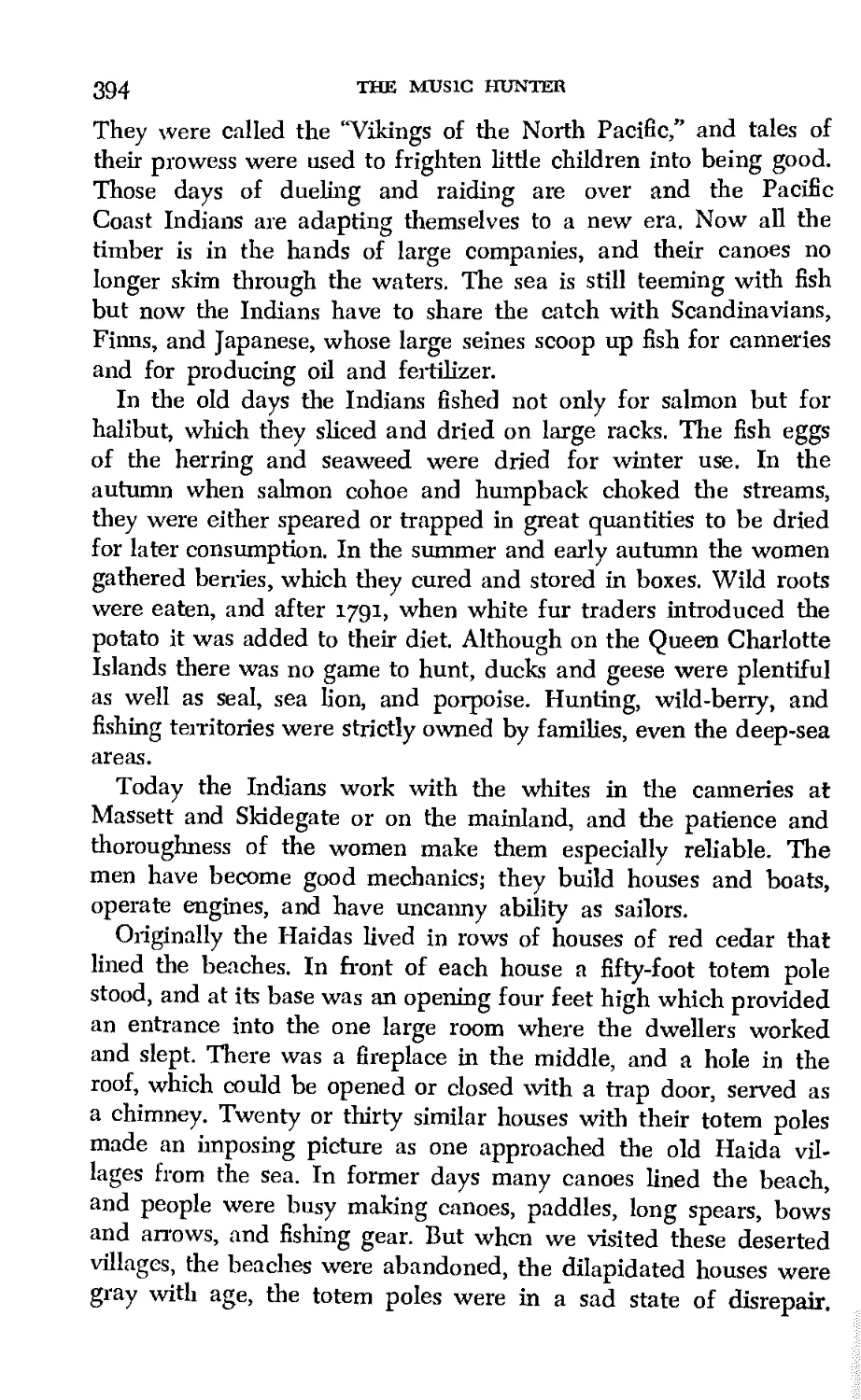

53. Navajo yebitchai (night chant) musicians with the medicine man

at far right

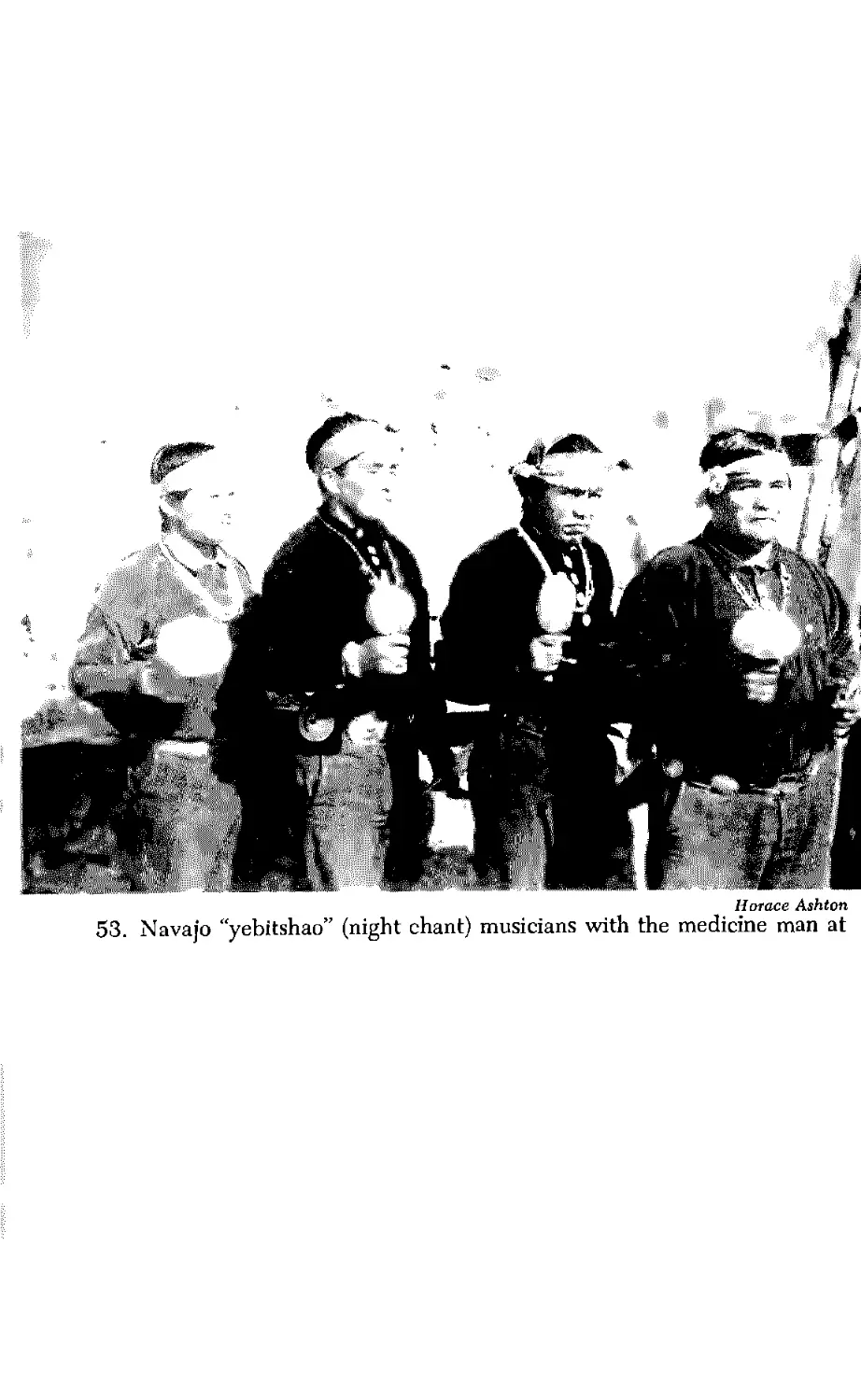

54. Los Voladores Flying Pole Dance

55, Yaqui Deer Dancer

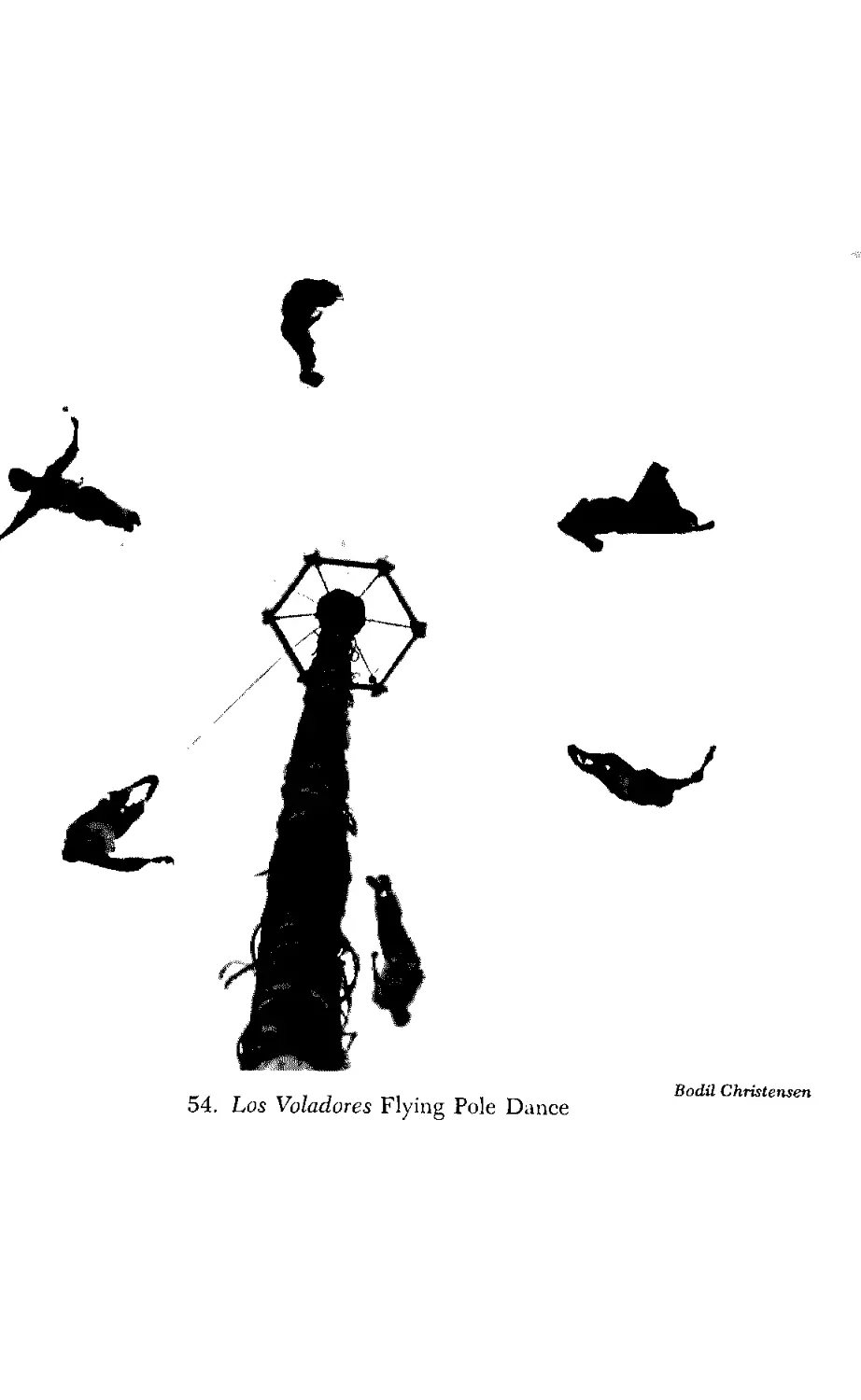

56. Houngon making the vevers

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

xii

57. Author recording Haitian singers

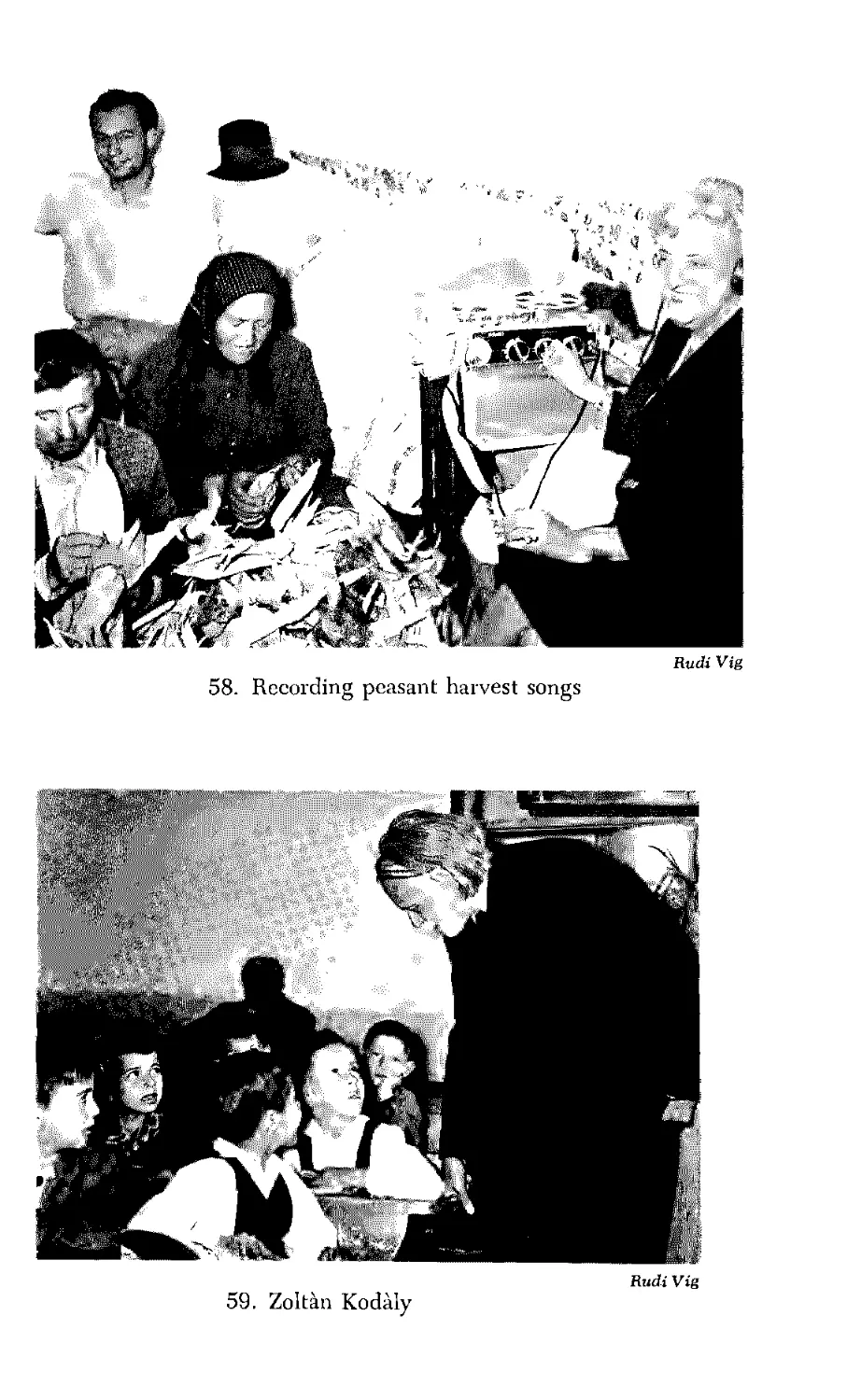

58. Recording peasant harvest songs

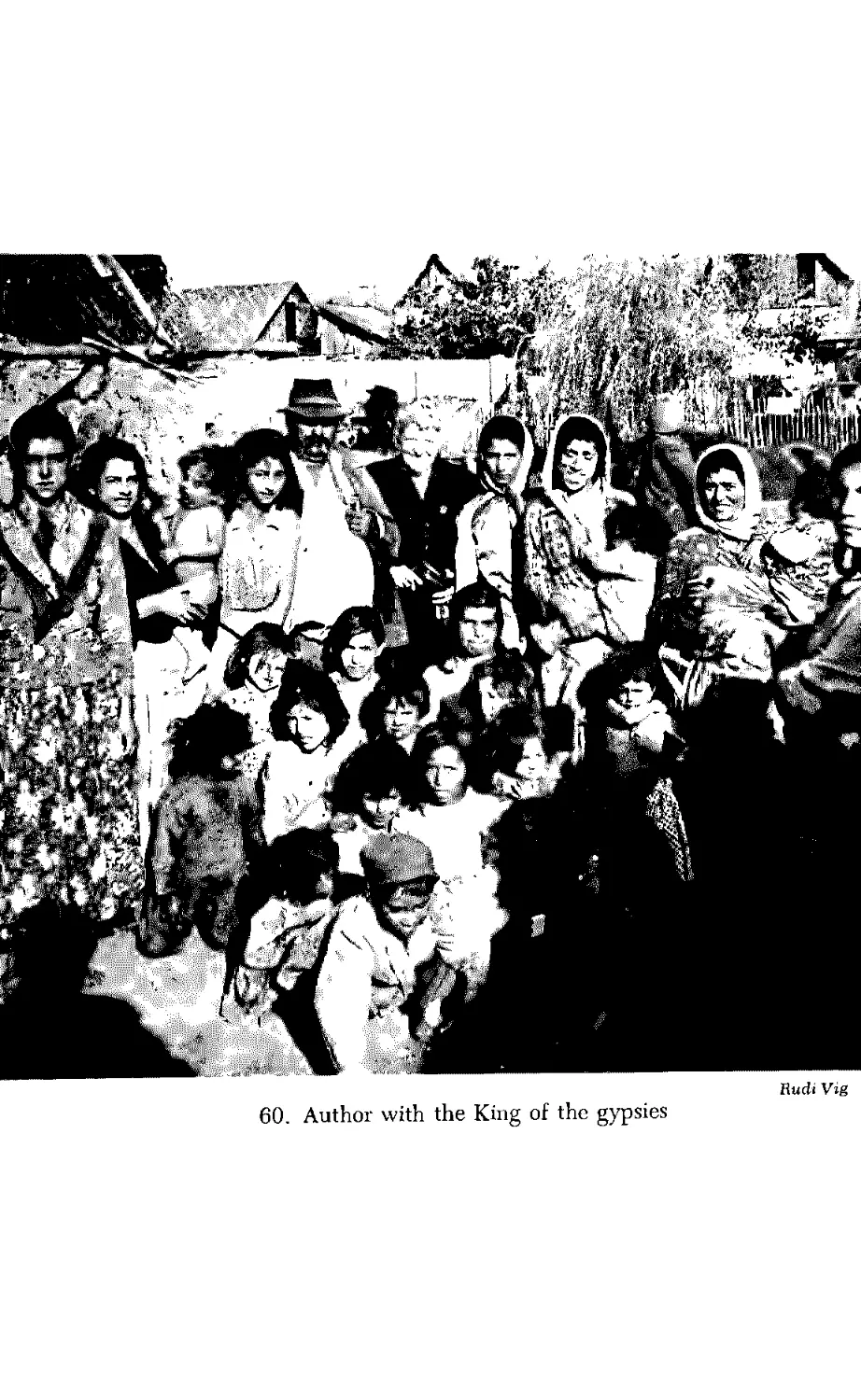

59. Zoltan Kodaly

60. Author with the King of the gypsies

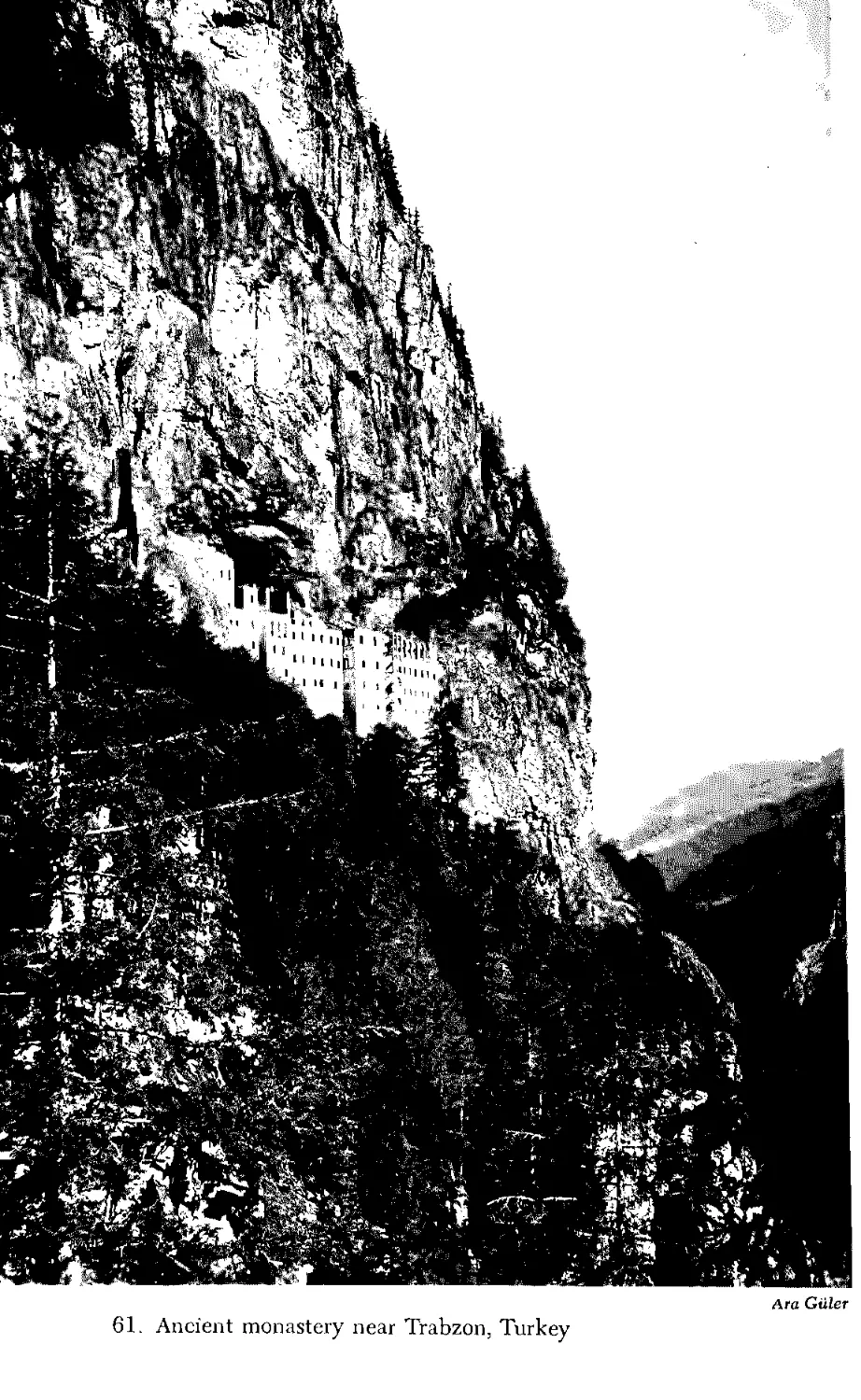

61. Ancient monastery near Trabzon, Turkey

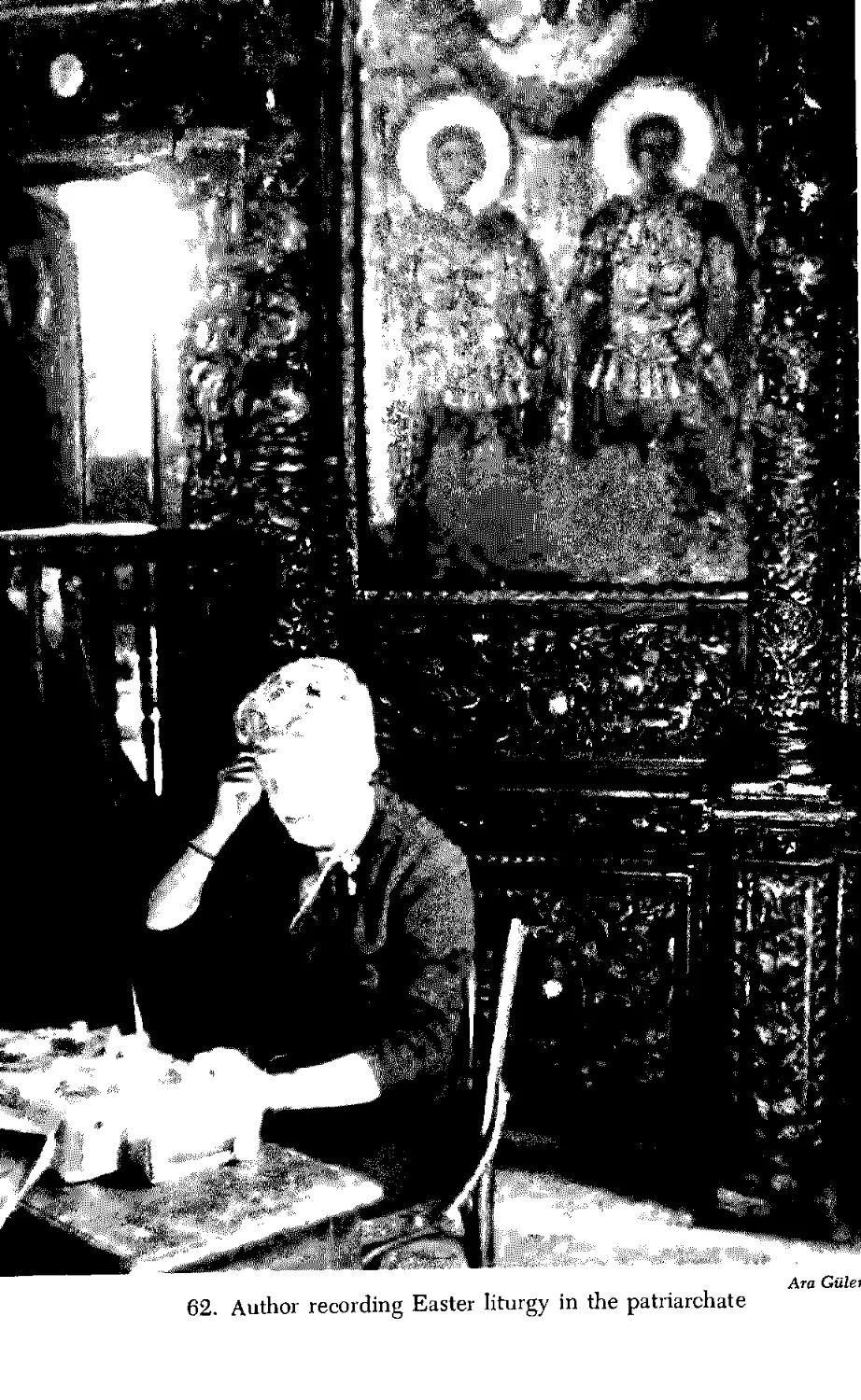

62. Author recording Easter liturgy in the patriarchate

63. Emperor Haile Selassie

64. Dance of David (sistrums in left hands)

65. Author recording Ethiopian orchestra

66. Musician playing “harp of David”

INTRODUCTION

This extraordinary book, by Dr. Laura Boulton, The Music Hunter,

is the fascinating story of the on-the-spot search by its author for

folk and liturgical music in all parts of the world. It records thirty-

five years of determined and dedicated effort to secure the tapes

and records of the music of peoples on all five continents and on

the islands of the seas. She penetrated almost inaccessible places.

Her journeys carried her deep into Eskimo territory, into sub-

Sahara Africa, into Nepal, Thailand, Borneo and elsewhere. She

never chose the easy places, concerned as she was to seek the most

authentic music directly from the people who were its creators

and users. Much of her travel took place before recent improve-

ments in transportation and one is filled with awe that she should

have survived some of her experiences in travel and in local living

conditions. In her travels she felt equally at home as a guest of

great personalities like Dr. Albert Schweitzer, Prime Minister

Nehru, Emperor Haile Selassie or with natives hidden away in the

jungles, the mountains or frozen tundra.

She had a capacity to develop a quick and easy rapport with her

hosts, whoever they might be, and thus elicited from them not

only warm cooperation in the rendition and recording of music,

but, as well, a flood of folk habits which gives music a meaningful

setting. While the book is an exciting diary, it is more than that. It

is alive with acute observations of the folkways of peoples, their

traditions, their customs, their ways of life, their hopes and con-

cerns, their struggle for sheer physical existence. These are the

xiv

INTRODUCTIChV

materials out of which music is bom, the crowning jewel of a

culture. Music is both the language and the reflection of the lives

of peoples.

As Dr. Boulton points out, music is the universal language. It

is a form of communication universally understood. Whether as

the universal language or as a language of identifiable folk whose

lives are carved by custom and tradition, it throws a penetrating

light upon values of importance to the human race and to its

separate parts.

Under conditions which were often unbelievably difficult Dr.

Boulton succeeded in securing recordings and tapes of folk and

liturgical music previously unavailable to the outside world. While

recording the music she also collected a rich treasure of musical

instinments, many primitive in character and unusual in design.

It is fortunate for the world of music that Dr. Boulton engaged

in her numerous adventurous expeditions even before improved

transportation would have eased her task, for today the spread of

popular music through the radio and the disc is blotting out much

of the native music which she had the satisfaction to record and

from which the world will benefit.

Her collection of thirty thousand recordings and scores of musi-

cal instruments form the heart of the Laura Boulton Collection at

Columbia University. Surrounded by these rich resources collected

on at least twenty-eight expeditions, she is directing today a re-

search program in world music in die School of International Affairs

at the University. It is her concern to share this music as widely

as possible with students, faculty and the general public, and an

increasing number of her recordings are being made into albums for

wider distribution.

Andrew W. Cordier,

Acting President

Columbia University

A7ew York City

Section I

AFRICA

Chapter i

THE BEGINNING

It hardly seems possible that so many years have passed since I

made my first recordings in an African rain forest. Little did I

know that the ensuing years would take me to every comer of the

world, from the frozen wastes of the Arctic to voodoo ceremonies

in Haiti, from the snow-capped mountains of Nepal to the Penguin

Islands at the tip of Africa, from Tibetan lamasaries to Buddhist

temples in Japan, and from the courts of kings to the huts of

peasants.

In every instance my object was the same: to capture, absorb,

and bring back the world’s music; not the music of the concert

hall or the opera house, but the music of the people, their expres-

sion in songs of sadness and joy, their outpourings in times of

tragedy and times of exaltation.

In remote areas of the world, where the tribes were at first

very shy with me and distrustful of my recording machine, I de-

vised a game: first I recorded a gay French folk song, singing it

with gestures, and then played it back for them. Their faces

would inevitably burst into smiles when they recognized my voice

and saw they did not need to fear my machine. After that every-

one wanted to sing for me at once. Having a quick musical ear, I

could soon sing with them some of their own songs. Nothing I

could have done would have established me more firmly, more

rapidly, as a friend. Bestowal of gifts establishes contact; a sharing

of music inspires trust. This bears out what I have always believed:

4

THE MUSIC HUNTER

that music is the one perfect form of communication that knows

no barriers.

My wise parents brought me up without prejudices. I have

been able to collect rare music and attend sacred ceremonies never

previously witnessed by white people, and sometimes in regions

where a white woman had never been seen, only because these

people knew that my interest in them was not just idle curiosity.

I was willing to spend many hazardous months seeking them out

because I was genuinely interested in their music and in what

that had to teach me.

After twenty-eight expeditions all over the world, where shall

I begin? The Chinese say that the longest journey starts with

the first step. My first step was a firm background in music,

both in theory and in performance. A small fortune had been

spent on the training of my voice and the nature of my career

seemed never to have been in doubt. As a small child, I am told,

I concluded every bedtime prayer with “Dear God, make me a

high soprano/’ This gift and an extensive training were not to be

wasted, but none of us could have forseen the direction in which

they would take me.

I sang my first solo in an operetta at the age of three and was

planning a concert career, but it had barely begun when the

invitation came to join the Straus African Expedition for the

American Museum of Natural History in New York. In spite of

vigorous protest from my musical mentors, I accepted this mar-

velous opportunity to hear indigenous music in Africa. As serious

as my musical interests were on the expedition at the time, I did

not dream that the study of the world’s music would occupy the

rest of my life and lead to long years of research and field work

(including university graduate work in musicology and anthro-

pology) combined with lecturing and teaching at major uni-

versities in America, Europe, and Asia. When I brought back my

first recordings out of Africa, there was no word for my career.

I used to be introduced as a musical anthropologist or an an-

thropological musicologist. Now we have a word: ethnomusicologist.

I am deeply grateful to Mrs. Oscar Straus, the patron of my

first expedition, who because of her interest in music encouraged

me to take time from the museum collecting of everything that

crawled, flew, moved, and breathed to record the songs and

AFRICA

5

rhythms of Africa. This was the beginning of a career that has

become increasingly absorbing.

It was Africa that provided for me the first exciting proof of

what I had always believed to be true: that music is the most

spontaneous and demonstrative form of expression the human

family possesses, that truly it is the one language that needs no

translation. It was my good fortune that I was able to work in

world music before people had changed so much—for example,

throughout Africa while villages were still purely African villages,

in Vietnam while it was still Indochina and people had time to

sing. A great deal of political history has been made in the last

thirty-five years and much that was beautiful in the tribal lore has

now been lost.

Musicologists today often have a struggle to locate the genuine

article; the end product is so often influenced by "civilization,” that

only keen research reveals how much is worth collecting at all.

When I returned to Bechuanaland fifteen years after my first

expedition there, I could find only a few of the songs I had re-

corded before. During a Red Cross campaign to raise money, the

Africans, wishing to make their contribution, thought of an ingen-

ious way of raising funds. They organized a concert. There was a

cost of sixpence to have a number performed and a shilling not

to have it performed. As a shilling was a lot of money to an

African in those days, every number was performed and the

concert lasted all night. But of the forty-three songs performed,

only six were genuine African melodies. All the others were a very

poor imitation of Bing Crosby or one of the latest popular singers

heard on the radio or in the movies. The ability to distinguish be-

tween genuine material and what is hybrid is the result of intensive

study and ear development.

Before the invention of portable recording equipment, musical

notation was the only way to preserve the music heard, but it

simply was not possible to capture all the little quavers, the

elaborations, the variations which, on first hearing, eluded the

Western ear, however trained. Even with today’s highly scientific

recording equipment, one must still listen with earphones over

and over before the music can be correctly transcribed. Ethnic

music has become such a scientific study that we are now de-

veloping machines to examine and analyze the melodies and

6

THE MUSIC HUNTER

rhythms. There are even computers in which melodies go m one

end and come out the other, classified and “transcribed.”

While struggling one day with the acoustics involved in record-

ing the ancient Benin ceremony of sacrifice in Southern Nigeria,

I could not have known that religious music was to become the

major interest of my musical studies, and that I would record not

only the primitive rituals of Africans, but also those of Eskimos

and American Indians, sacred voodoo ceremonies in Haiti, New

World African rites in Brazil, and unique music of the Todas, a

disappearing hill tribe of India whose funeral ritual, being secret

and profoundly sacred, had never before been heard by an out-

sider, I was told.

Eventually I was to go on to record, study, and collect representa-

tive musical material in all twelve great religions of the world,

including Buddhist chants in Tibetan lamaseries, Zoroastrian hymns

in Iran, Hindu chanting in Himalayan ashramas during the great

Puma Kumbha Mela (Um Festival), ceremonial music in the

golden temple of Amritsar, seat of the Sikh religion, and ancient

music of the Far Eastern religions. More recently the early music

of Christianity—Byzantine and orthodox music—have been my

major interest.

I have retraced my steps to the countries formerly visited and

have found everywhere incredible change. Even in the earlier

days while working with remote groups, it was difficult if not

impossible to find informants who would agree completely in their

interpretation of tribal lore, or to witness a ceremony performed in

exactly the same way on different occasions. And certainly the

so-called authorities in their learned volumes often differ widely

in their facts, their spelling of local words—spelled phonetically, of

course—and particularly in their interpretations. I have for the most

part written of my own observations; world travelers unfortunately

can no longer experience the same fascination which these lands

formerly held. But this is the way it was.

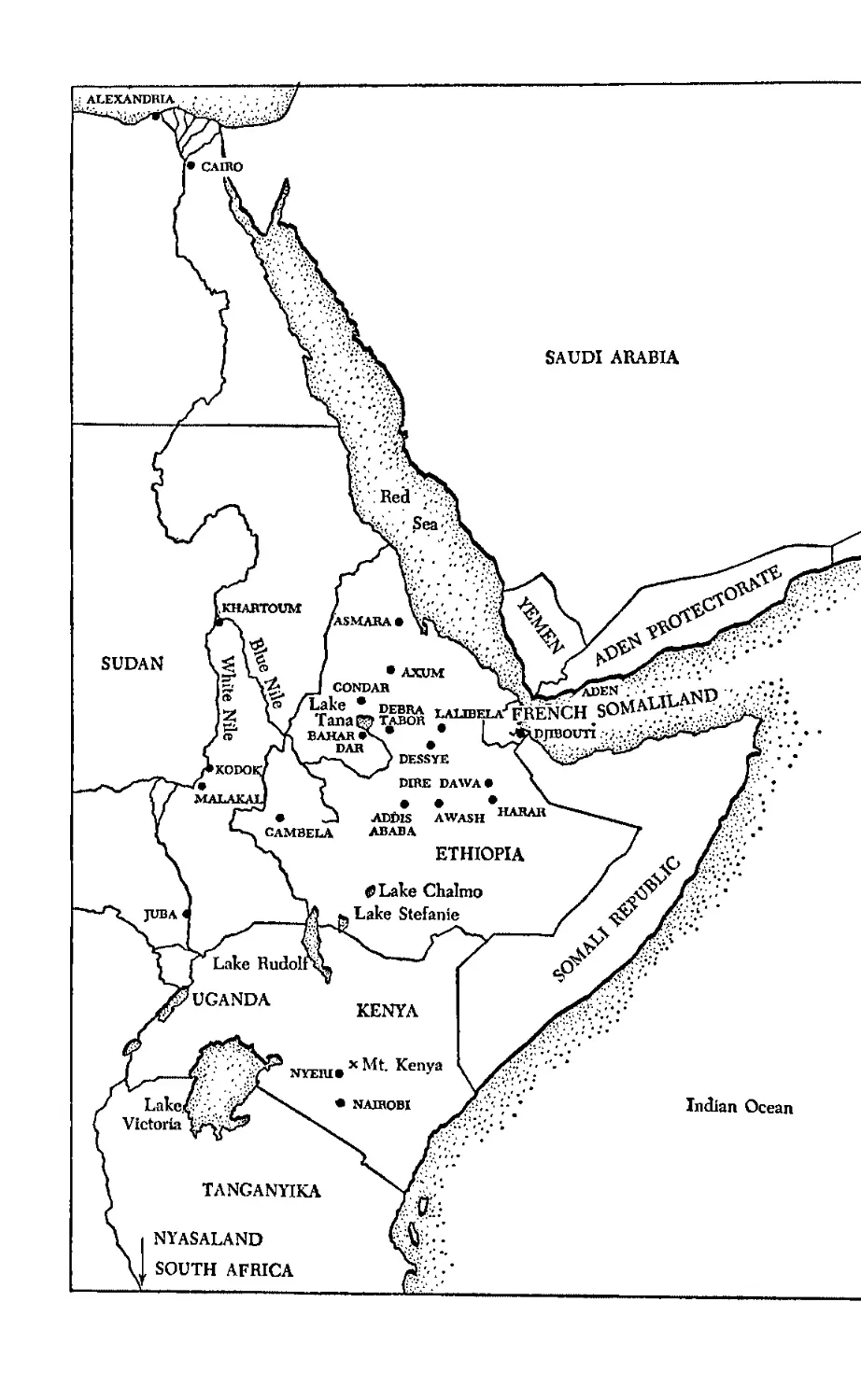

Chapter 2

UP THE NILE TO THE MOUNTAINS

OF THE MOON AND KENYA

I had to be satisfied with only rubbing shoulders with Alexandria’s

rich history: with walking where, three hundred years before

Christ, Euclid had paced back and forth while expounding the

theorems which have formed the basis of our present geometry;

where the scholar Eratosthenes accurately mapped die Nile in

250 B.c,; and where Nelson, in more modern context, defeated the

French in 1798 and Napoleon the Turks in 1799. The passage of

time seems to have left only a superficial imprint on this ancient

city. In this century intrigues may be on a wider scale and better

organized, but one sensed that the Arabian Nights atmosphere, the

intermingling of beauty and ugliness, and the scents and sounds

of the city are, and have always been, as fixed as the poles.

In Cairo one felt even more strongly the startling contrast of

being catapulted from the New World into the Old. Everywhere

there was ceaseless activity: the hubbub and bustle of the bazaar,

the raucous cries of the vendors, the hounding of dragomans who

insisted on showing us the rare sights and dark secrets of their

city, and the pitiful beggars and ragged urchins with hands for-

ever outstretched for baksheesh (to them, anything from money

to cigarettes). When the swarming crowds and the heat became

too oppressive, one had only to sit on the veranda of the old

Shepheard’s Hotel to witness the kaleidoscope of the East, for

sooner or later everything in Cairo passed by Shepheard’s, in-

cluding one day a party of celebrants singing in procession as

AFRICA 9

they returned from an ancient circumcision ritual. It was rather

like stepping from the Hilton into a page of the Koran.

The sense of antiquity was heightened still further for me in

the Museum of Cairo when I saw many of the priceless treasures

recovered intact from the tomb of King Tutankhamen, the ancient

king whose burial place had been abandoned by grave robbers,

and at Luxor, where I visited the excavations in the Valley of the

Kings. And then there were Heliopolis, the original site of Cleo-

patra’s Needles (now in London and New York), the Sphinx,

and the Pyramids. (Visiting these marvels brought for me the first

of many rides on a camel.)

Recently I was in Cairo for the sixth time, and for sentimental

reasons stayed at the new Shepheard’s Hotel. The original build-

ing had been burned down during the anti-British riots. The whole

world still paraded in front but this time there were more in-

tensified modern noises: big, smart American and European cars

and troupes of grim, revolution-minded Egyptians instead of gay

celebrants returning homeward from age-old rituals.

Though a new Egypt has evolved and an independent Sudan has

emerged, the Nile still dominates the whole of life, just as it has

for past millenniums. Near Cairo the waterway still teems with

activity and commerce of every kind; dahabeahs and feluccas and

other frail craft sail busily to and fro on the slow-moving brown

water, and the boats swarm with Arabs in long Mother Hubbard

gowns and turbans which lend them the rakish air of the brigands

remembered from childhood picture books. Here, too, the Kham-

sin (a hot sand storm) attacks without warning, with violent

winds overturning small boats and dumping voyagers and car-

goes into the river. Saving lives appeared to me to have been of

secondary importance to salvaging fruit, carrots, or anything edible

bobbing in the water.

For more than 5,500 years the height of the annual Nile flood,

rising in April, overflowing in September, on which cultivation of

crops was entirely dependent, had been ceremoniously measured

by the Egyptians. Then in 1902 the British government built the

first Aswan Dam to harness the floodwaters, which made possible

the growing of four crops annually in the rich Nile Delta. But with

this blessing came misfortune. Some of the oldest monuments

known to man were hidden under the waters of the dam. Probably

the most famous of these was the Temple of Isis on the island of

10

THE MUSIC HUNTER

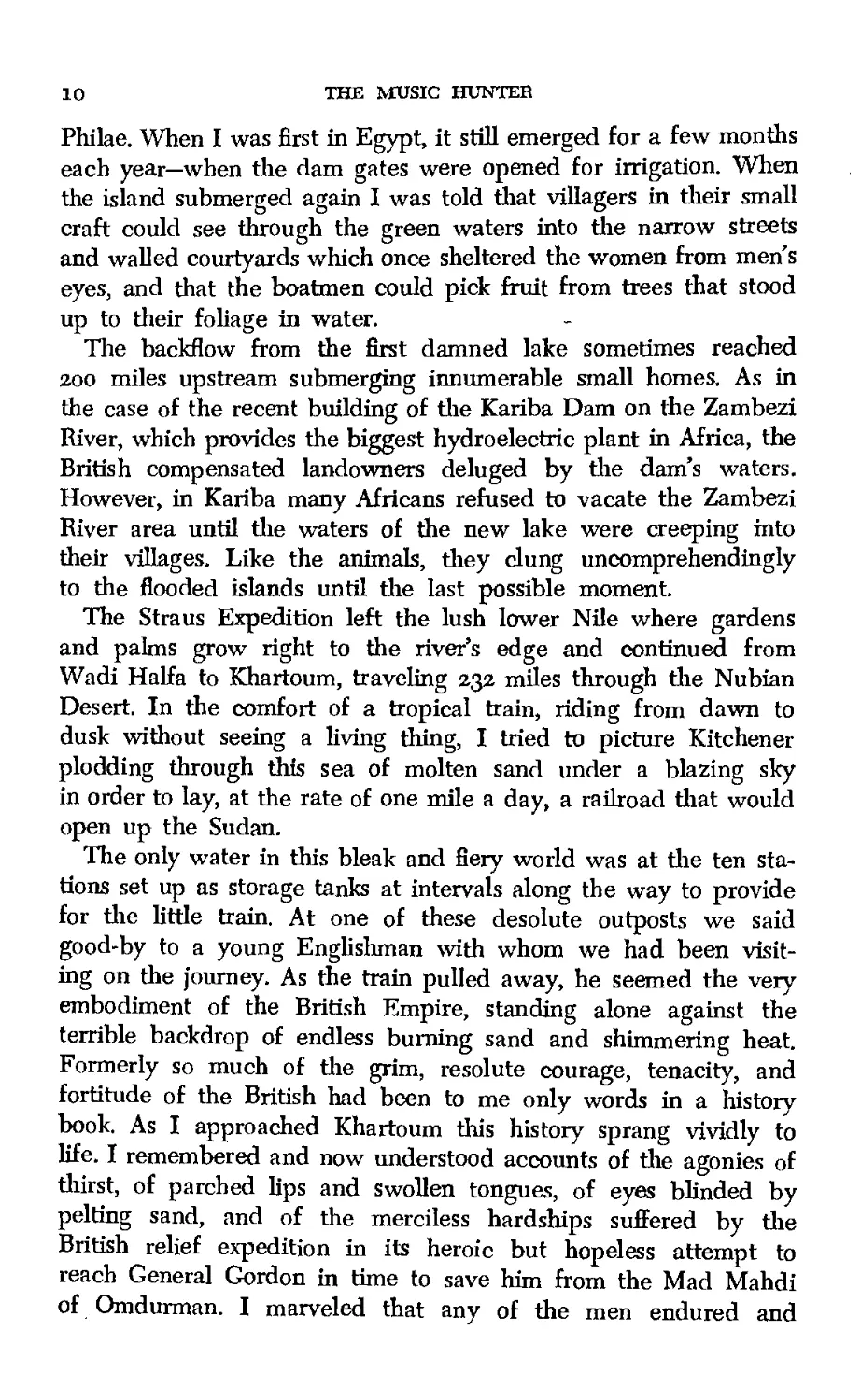

Philae. When I was first in Egypt, it still emerged for a few months

each year—when the dam gates were opened for irrigation. When

the island submerged again I was told that villagers in their small

craft could see through the green waters into the narrow streets

and walled courtyards which once sheltered the women from men’s

eyes, and that the boatmen could pick fruit from trees that stood

up to their foliage in water.

The backflow from the first damned lake sometimes reached

200 miles upstream submerging innumerable small homes. As in

the case of the recent building of the Kariba Dam on the Zambezi

River, which provides the biggest hydroelectric plant in Africa, the

British compensated landowners deluged by the dam’s waters.

However, in Kariba many Africans refused to vacate the Zambezi

River area until the waters of the new lake were creeping into

their villages. Like the animals, they dung uncomprehendingly

to the flooded islands until the last possible moment.

The Straus Expedition left the lush lower Nile where gardens

and palms grow right to the river’s edge and continued from

Wadi Haifa to Khartoum, traveling 232 miles through the Nubian

Desert. In the comfort of a tropical train, riding from dawn to

dusk without seeing a living thing, I tried to picture Kitchener

plodding through this sea of molten sand under a blazing sky

in order to lay, at the rate of one mile a day, a railroad that would

open up the Sudan.

The only water in this bleak and fiery world was at the ten sta-

tions set up as storage tanks at intervals along the way to provide

for the little train. At one of these desolute outposts we said

good-by to a young Englishman with whom we had been visit-

ing on the journey. As the train pulled away, he seemed the very

embodiment of the British Empire, standing alone against the

terrible backdrop of endless burning sand and shimmering heat.

Formerly so much of the grim, resolute courage, tenacity, and

fortitude of the British had been to me only words in a history

book. As I approached Khartoum this history sprang vividly to

life. I remembered and now understood accounts of the agonies of

thirst, of parched lips and swollen tongues, of eyes blinded by

pelting sand, and of the merciless hardships suffered by the

British relief expedition in its heroic but hopeless attempt to

reach General Gordon in time to save him from the Mad Mahdi

of Omdurman. I marveled that any of the men endured and

AFRICA

11

survived this terrible tract of country. A Bedouin camel caravan

may occasionally reach its destination, but the numerous bones

scattered along the way, protruding from the sand, testified to

the numbers that did not. I imagine that the songs of these lonely

travelers must have been very sad indeed, much more tragic than

the music I recorded later of the meharists, the camel patrol of the

Sahara.

My first intimate contact witb African wildlife was in a small

zoo in Khartoum where exotic birds (spoonbill and shoebill storks,

and secretary birds, the latter so named because of crest feathers

resembling quill pens behind their ears), and beautiful golden ga-

zelles balancing on slender legs wandered about freely. It was there

that I made my first African animal friend, a baby hippo. He looked

forward to our late afternoon visits and, at our approach, would

rush to the wire of his enclosure, opening his enormous cavern of

pink mouth. When a lump of sugar was dropped into it, he would

stand there sucking and looking ridiculous, with tears of pure

pleasure pouring down his lumpy cheeks. He had come to expect

this daily ration of sugar, for a British officer stationed at Khartoum

had spoiled him for many months before our arrival by cultivating

his sweet tooth. It was there also that we met our first African lion,

a not very kingly, rather shamefaced old fellow with only a stub

of a tail. If you have never seen a bobtailed lion, you cannot

imagine what a pitiful and incongruous sight he presents. This

one had carelessly gone to sleep with part of his formerly proud

tail lazily protruding into the next cage, where a hyena had

bitten it off. Khartoum rocked with his roars for two weeks.

After the desolation of the Nubian Desert, we looked forward to

relief when we boarded a small stern-wheeler, the government

mail boat, for our journey southward “up the Nile” to the head-

waters at Rejaf. Our boat pulled two barges, one for sleeping

and one for eating. The heat in the Sudan was so intense that the

cabins on the boat were bearahle only long enough to dress. The

sudd, floating islands of papyrus grass, made night navigation im-

possible, so at sunset we anchored offshore and after dinner fell

asleep under our nets to the ceaseless clamor of crickets and

frogs, and the drone of mosquitoes. These pests surrounded us in

ferocious swarms ready to devour anything and everybody the mo-

ment the north wind dropped, as it did each evening. In the

velvety blackness before daylight we would be awakened by the

12

THE MUSIC HUNTER

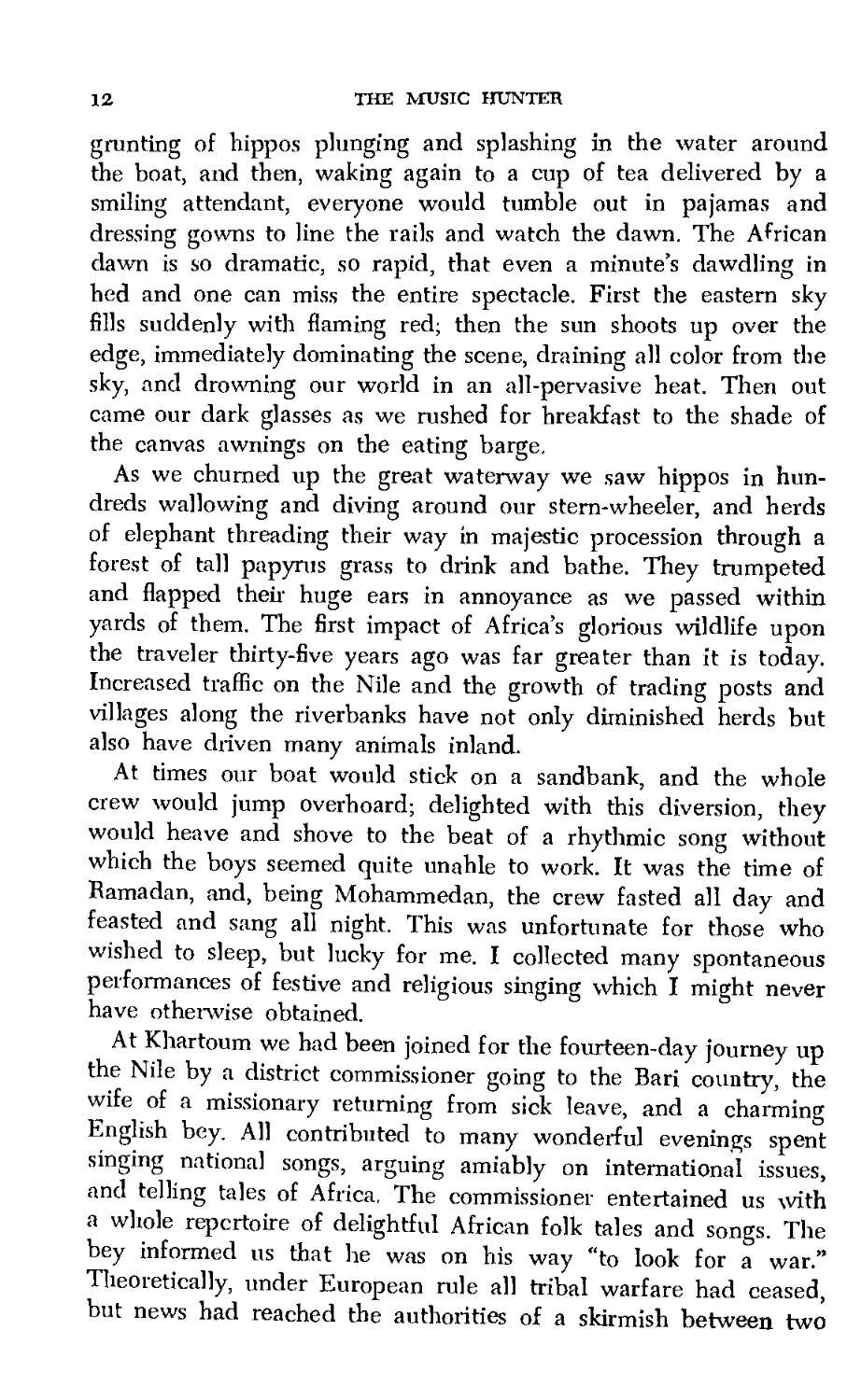

grunting of hippos plunging and splashing in the water around

the boat, and then, waking again to a cup of tea delivered by a

smiling attendant, everyone would tumble out in pajamas and

dressing gowns to line the rails and watch the dawn. The African

dawn is so dramatic, so rapid, that even a minute s dawdling in

hed and one can miss the entire spectacle. First the eastern sky

fills suddenly with flaming red; then the sun shoots up over the

edge, immediately dominating the scene, draining all color from the

sky, and drowning our world in an all-pervasive heat. Then out

came our dark glasses as we rushed for breakfast to the shade of

the canvas awnings on the eating barge.

As we churned up the great waterway we saw hippos in hun-

dreds wallowing and diving around our stern-wheeler, and herds

of elephant threading their way in majestic procession through a

forest of tall papyrus grass to drink and bathe. They trumpeted

and flapped then huge ears in annoyance as we passed within

yards of them. The first impact of Africa’s glorious wildlife upon

the traveler thirty-five years ago was far greater than it is today.

Increased traffic on the Nile and the growth of trading posts and

villages along the riverbanks have not only diminished herds but

also have driven many animals inland.

At times our boat would stick on a sandbank, and the whole

crew would jump overhoard; delighted with this diversion, they

would heave and shove to the beat of a rhythmic song without

which the boys seemed quite unahle to work. It was the time of

Ramadan, and, being Mohammedan, the crew fasted all day and

feasted and sang all night. This was unfortunate for those who

wished to sleep, but lucky for me. I collected many spontaneous

performances of festive and religious singing which I might never

have otherwise obtained.

At Khartoum we had been joined for the fourteen-day journey up

the Nile by a district commissioner going to the Bari country, the

wife of a missionary returning from sick leave, and a charming

English bey. All contributed to many wonderful evenings spent

singing national songs, arguing amiably on international issues,

and telling tales of Africa. The commissioner entertained us with

a whole repertoire of delightful African folk tales and songs. The

bey informed us that he was on his way “to look for a war.”

Theoretically, under European rule all tribal warfare had ceased,

but news had reached the authorities of a skirmish between two

AFRICA

13

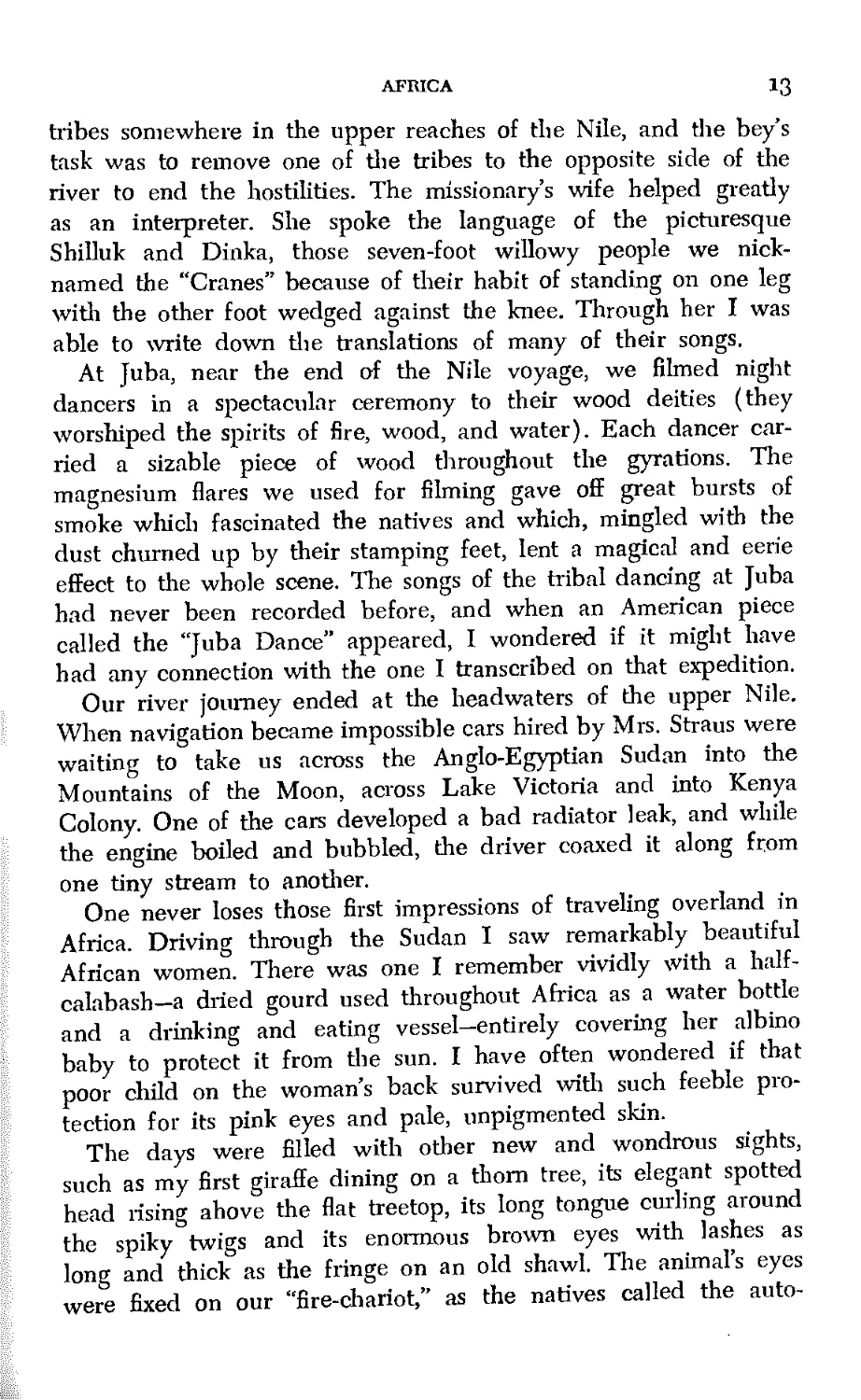

tribes somewhere in the upper reaches of the Nile, and the beys

task was to remove one of the tribes to the opposite side of the

river to end the hostilities. The missionary’s wife helped greatly

as an interpreter. She spoke the language of the picturesque

Shilluk and Dinka, those seven-foot willowy people we nick-

named the “Cranes” because of their habit of standing on one leg

with the other foot wedged against the knee. Through her I was

able to write down the translations of many of their songs.

At Juba, near the end of the Nile voyage, we filmed night

dancers in a spectacular ceremony to their wood deities (they

worshiped the spirits of fire, wood, and water). Each dancer car-

ried a sizable piece of wood throughout the gyrations. The

magnesium flares we used for filming gave off great bursts of

smoke which fascinated the natives and which, mingled with the

dust churned up by their stamping feet, lent a magical and eerie

effect to the whole scene. The songs of the tribal dancing at Juba

had never been recorded before, and when an American piece

called the “Juba Dance” appeared, I wondered if it might have

had any connection with the one I transcribed on that expedition.

Our river journey ended at the headwaters of the upper Nile.

When navigation became impossible cars hired by Mrs. Straus were

waiting to take us across the Anglo-Egyptian Sudan into the

Mountains of the Moon, across Lake Victoria and into Kenya

Colony. One of the cars developed a bad radiator leak, and while

the engine boiled and bubbled, the driver coaxed it along from

one tiny stream to another.

One never loses those first impressions of traveling overland in

Africa. Driving through the Sudan I saw remarkably beautiful

African women. There was one I remember vividly with a half-

calabash—a dried gourd used throughout Africa as a water bottle

and a drinking and eating vessel—entirely covering her albino

baby to protect it from the sun. I have often wondered if that

poor child on the woman’s back survived with such feeble pro-

tection for its pink eyes and pale, unpigmented skin.

The days were filled with other new and wondrous sights,

such as my first giraffe dining on a thorn tree, its elegant spotted

head rising ahove the flat treetop, its long tongue curling around

the spiky twigs and its enormous brown eyes with lashes as

long and thick as the fringe on an old shawl. The animal’s eyes

were fixed on our “fire-chariot,” as the natives called the auto-

14 THE MUSIC HUNTER

mobile. In Latuka, as in many villages of this region, the people

were naked. The chief s councilors, however, wore metal helmets like

those of Crusaders. It is thought that at least one of the nine

military expeditions undertaken in the name of Christianity be-

tween 1095 and 1272 passed through this area, leaving behind these

relics.

At Fort Portal in Uganda we slept for the first time under

thatched roofs in small rest huts, provided by the British officials

along the route. The eerie, unidentifiable noises of the African

night, the rustlings and scurryings of unseen things, the whir and

bump of insects beating against the mosquito netting, and the

constant barrage of flying, crawling, squeaking creatures were at

first terrors I had previously encountered only in nightmares. Hip-

pos, too, thumping and grunting outside the hut, frequently used

the mud wall of the huts as rubbing posts. The large herds of

hippos in this area made it necessary to post a notice on the little

golf course at Fort Portal to the effect that a player could,

without penalty, lift his golf ball out of a hippo track.

In Uganda we followed close on the heels of the Duke of

Windsor, then Prince of Wales, who was on safari with Uganda’s

top white hunter, Captain Salmon—known as Samaki, the local

African word for fish. Samaki, a charming English ex-army officer,

later told us fascinating tales of his life in Africa, including the

royal safaris.

It was not Samaki, however, but another white hunter who

took us on our first collecting trek into the snow-capped Moun-

tains of the Moon on the border between Uganda and the

Belgian Congo. We camped near a mountain stream where the

elephants came to drink and bathe. One night a large herd of

these giants plowed through the area, and I have to admit that I

slept through the rumpus, for there is no deeper fatigue than that

induced by a long, exacting day in the bush. In the morning I saw

the spoor everywhere. Trees were uprooted all about us, as if to

show the resentment the elephants felt at our intrusion into their

private lives.

We had been out only a short time when our hunter did a foolish

thing. He shot a hippo to provide meat for our safari boys, and

ate some of it. Hippo meat is eaten by the indigenous people of

Africa but it apparently was too rich for him. Within a few hours

AFRICA

15

he was desperately ill, in great pain, and convinced that he was

going to die. This is the end/ he wailed. “This will do me in.”

Though the nearest settlement was about fifteen miles away,

I set off with an African guide hoping to find a doctor, leaving

the men of our party to break camp and to make the difficult

trek down the mountain with a two-hundred-pound invalid in an

improvised hammock. Ned, Mrs. Strauss grandson, appalled at

the thought of my going off through the mountains with only an

African for protection, came crashing after me (he was heavy

and unused to strenuous exercise). “Laura, Laura,” he panted,

“wait for me, wait for me.” A doctor was located, the sick hunter

was left in his charge, and we were on our way to Entebbe.

We crossed Lake Victoria—Africa’s largest lake, forming part

of the border of East Africa’s three territories—to Kampala,

now a large city but then only a small village, and went on into

Kenya, bumping over rutted dusty roads, crossing the equator at

9,000 feet (it was a weird feeling to be freezing right on the equa-

tor), to Nairobi.

Two tilings I saw for the first time on this journey remain im-

printed forever in my mind: the majesty of the Bift Valley, the

volcanic cleft which ages ago split open the green heart of east

Africa; and the splendor of the flamingos, rising in pink shimmer-

ing clouds as we approached the blue waters of Lake Navaisha.

Thousands of these graceful birds, much more brilliant than the

flamingos of Nassau or our South, come every year to feed on the

fish in the lake. Seen at sunset, their bright plumage mingling

with the blues, purples, and golds of the hazy light filtering through

the valley, they are a breath-taking sight.

In the Kenya Highlands, outside Nyeri, we stayed with Major

Walker and his wife in their recently built Outspan Hotel. They had

installed a boma, an observation platform, high in a tree in the

midst of dense forest some miles from the town overlooking a salt

pan. Here we saw animals of every kind coming, as they had for

centuries, to lick the natural salt from the earth. This first rough

boma was later enlarged into a small treetop hotel which even-

tually became famous throughout the world. While Princess Eliza-

beth was the guest of the Walkers, her father died. The young

woman had climbed into the tree house a princess, and came down

a queen.

The original Treetops was burned during the Mau Mau terrors,

16

THE MUSIC HUNTER

but later a compact, modern hotel was built in the heart of another

giant tree with verandas where guests can sit in strictest silence

and look down on herds of rhino, elephant, gazelle, and families

of ridiculous wart hogs, with their wireless-aerial tails, licking

the salt below. The only talking permitted is at a little bar or dur-

ing meals, and even then it must be carefully modulated so as not

to frighten the animals at the salt pan. To augment the natural

supply, salt is sprinkled over the pan area during the day; when

there is no moon or it is covered by a cloud, there are now con-

cealed floodlights which cleverly filter through the trees to simu-

late moonlight. This apparently hoodwinks the animals completely.

It is not possible to drive through the dense forest to Treetops,

and visitors have an exciting twenty-minute trek going through

the bush in complete silence, guarded by an armed white hunter

and several African guards. Now long slat ladders are fixed to

trees at intervals along the track as uneasy reminders of imminent

attack from rhino and elephant which abound throughout this wild

Aberdare country. There were no such comfortable safeguards

on my first visit.

The Walkers lived in the heart of the Kikuyu territory, where

the murderous, oath-taking Mau Mau movement began, though

the Kikuyu appeared to be a peaceful and contented people

when we were there. Yet only a little more than twenty years

later they had instituted their secret anti-European terrorist move-

ment in which Jomo Kenyatta, the present prime minister of Kenva,

figured so largely. While in Kikuyu territory, we filmed many of

their dances, the most exciting being the vigorous dance of the

circumcision ceremony, in which the initiates made themselves

grotesque by liberal use of paint and other embellishments. Over

their short toga-like garment, which is knotted over one shoulder,

they wore black and white colobus-monkey shawls and handsome

leopard skins that swung out in back as they danced. Symbolic

red and white paint was applied to their heads, faces, arms, and

legs in geometric designs, and bands of cowrie shells hunff down

their outside upper legs supporting metal rattles shaped like pea

pods. Each boy carried a short stick topped with plumes made

from cow tails, and a few had small wooden shields brir^tly

painted in triangles of deep hhie and white edged with red. One

wore a mask made from animal skin, and the leader carried a long

staff. It was not possible to record all the sounds of such violent

AFRICA

17

group activity on my wax-cylinder recorder. To have preserved

anything at all with that early equipment was something of a

miracle.

Before leaving New York we had booked a safari with Kenya’s

most sought-after white hunter, Denys Finch-Hatton. The youngest

son of the Earl of Winchelsea, he had gone to Kenya on a hunt-

ing trip and loved the country so much that he had decided to

spend the rest of his life there. Finch-Hatton, too, had recently

taken the Prince of Wales on a shooting safari, and we feared that

he might be bored with our party because in Kenya we shot only

with cameras. But our fears were ungrounded, for he was not

only interested in our photographic work but equally interested in

studiously observing the game.

He was a tall, striking man, with large blue eyes which revealed

his sense of humor more than did his quiet personality. His charm

made fireside chats and safari dinners unforgettably happy. His

witty conversation and stories full of wisdom and knowledge of

Africa made us reluctant to retire at night On the plains and

in the bush we saw demonstrated time and again his rapport

with wild animals. He could detect every spoor, anticipate every

movement, and by testing the wind tell exactly how close we

could approach game. He and his head hunter found the wind’s

direction by constantly stooping as we cautiously advanced, gath-

ering handfuls of dirt, letting it sift through their fingers, and

judging the wind by the direction in whieh the dust was blown.

Life in camp was made easier by expertly trained and highly

efficient camp boys. When we arrived at a campsite hot, dusty,

and tired, almost before we were out of the cars there would be

a fire going, a cup of tea ready, and soon our tents were up,

with beds made. After a hot bath in a folding canvas tub, every-

one would gather for drinks and dinner, clean and fresh in bush

jacket, slacks, and mosquito boots. Because we were so near the

equator, there was no twilight and darkness descended suddenly.

I looked forward to these evenings about the campfire. They were

the best part of each day.

Our first night in the bush we were thrilled to see a whole

family of magnificent lions—a male, two lionesses, and four cubs

—prowling about in front of our camp. They appeared to be as

fascinated by our movements around die campfire as we were by

theirs in the moonlight.

18

THE MUSIC HUNTER

At dawn and dusk we would go into the bush to watch and

photograph animals of every kind coming to drink at the water

holes: elephant, buffalo, zebra, and great herds of antelope from

the awkward wildebeest to the exquisite gazelle. All would lift

their heads nervously from time to time, muzzles held high to

scent the wind, then scatter wildly at some slight sound or from

an instinctive sense that warned of a lioness nearby. Many trag-

edies occur beside water holes, where animals, absorbed in slaking

their thirst, are taken unaware. However, the majority of the

animals are saved by their strange form of “radar” which can

broadcast throughout a herd in seconds the presence of a killer.

On late afternoon drives we often spotted two or three lions

crouched in the tufty scrub, cleverly stationed near the water

hole, and were delighted to see the herds of zebra and antelope

gallop away before the cats had an opportunity to strike.

The cameraman and I had a sharp lesson in emergency be-

havior while we were camping for a week in the midst of a herd

of feeding elephant. One day while we were filming a huge bull

elephant, the wind changed and he caught our scent. Trunk

raised, ears happing, he rushed at us trumpeting wildly. On an

impulse we raced for an eight-foot anthill and scrambled up it;

Finch-Hatton drew the bull’s attention away from us, and we

crawled down from our perch, but with little dignity. Finch-Hat-

ton then explained that climbing the anthill was the worst thing

we could have done. Although these African termite nests are

calculated to be twenty-seven times the height of the Empire

State Building judged in terms of the size of the insects, even

an African anthill would have afforded little protection from a

giant elephant weighing six tons, had he really meant business.

AH we had accomplished was to draw further attention to our-

selves.

It was on this safari that we filmed the Masai, a tall, proud,

and dignified people, one of the more reticent of African tribes.

Before the days of organized protection of wildlife, a Masai lion

hunt might continue over many days. When a lion was surrounded,

the warriors would close in inch by inch or stand immobile for

what seemed hours, ebony statues in the long golden grass, await-

ing the signal to advance on their quarry. Their only weapon

against the infuriated beast was the traditional long spear, but it

was very seldom that they failed to make a kill. For a young

AFRICA

19

Masai to wound and not kill his lion outright during the blooding

ceremony was a dishonor, for the Masai believe that it is better

that a young warrior be killed by a wounded lion than survive

as a coward. We learned that many chose death in this manner.

All in all, this was one of the happiest episodes in my life. It

was in great part due to Denys Finch-Hatton that every day of

the safari is still a glorious landmark in my memory. We were

very sad when we said good-by to him at Voi on the Tsavo

River, and we were deeply shocked to learn of his death about

a year after our parting. He had crashed in a small plane which

he had bought to survey the herds of game he loved so much.

He had been burned to death at Voi, where when we had last

seen him he was smiling and waving good-by.

There is a touching tribute to this delightful and cultured man

by Isak Dinesen in Out of Africa. Having shared much of the

same kind of background in their native countries, Baroness Karen

Blixen (Dinesen’s true name) and Finch-Hatton were very close

friends and spent much time together reading the classics, listen-

ing to symphonic records, and conversing in Latin for the fun of

it.

When I first met the Baroness, she was still living on her

African farm, and although I knew her later in her native Co-

penhagen, it is against the background of the Africa she loved

that I see her most vividly. A story she once told me and later

published gives an insight into this wonderful woman’s character,

and illustrates the kindness and affection shown by many Euro-

pean settlers to their African workmen, something rarely remem-

bered in these days of rapid changes. The Baroness had just

received a letter from die King of Denmark thanking her for

die gift of a magnificent lion skin which she had sent to him, a

skin worthy of a king, for which she and Finch-Hatton had

searched for a long time. While she was reading the letter, a

frightened boy burst into her home to tell her that one of the

farm boys had been badly hurt in a wood-chopping accident.

Thrusting die letter into the pocket of her bush jacket, she rushed

to him.

A king means something special to Africans, and the workers

had always loved her stories about her king. On the way to the

hospital in the ambulance, she sat beside the boy, pacifying him.

To keep his mind off his pain, she showed him die letter she

20

THE MUSIC HUNTER

had just received from her king. He begged to touch it, and she

gave it to him to hold. Throughout his stay in the hospital, and

even in death, the letter (now bloodstained) was clutched to his

breast as though it were the last thread holding him to life. She

did not have the heart to take it from the boy.

Finch-Hatton had always expressed the wish to be buried in

his beloved Ngong hills outside of Nairobi overlooking the Athi

plains where the game roamed free in hundreds of thousands.

The last thing the Baroness did before leaving Africa forever

was to visit her friend’s grave. In Out of Africa she describes

having seen two proud lions, their tawny manes ruffled by the

wind, lying quietly on his grave. She wrote: ‘The lions on Lord

Nelson’s monument are only made of bronze.”

Chapter 3

TANGANYIKA’S MYSTERY MOUNTAIN

After the departure for New York of Mrs. Straus, her grandson,

and her companion, we continued the expedition for the American

Museum of Natural History through Tanganyika into Nyasaland,

where we would begin the Carnegie South African Expedition,

ending at Capetown and the Penguin Islands off the southwest

coast of South Africa. We said farewell to Mrs. Straus at Nairobi

and began our journey to the coastal city of Mombasa. But in

spite of our preparedness we were stranded on the banks of the

Tsavo River. Heavy rains had caused a flood that had carried

away part of the bridge, and we had no choice but to pitch

camp and wait for it to be repaired so that our trucks could

cross.

Of all the sounds and songs and cries and calls of an African

night, there is none so chilling as the roar of the lion. This is a

sound to which I could never become accustomed. You can feel

your skin prickling as other lions answer the first deep-throated

roar. We had not known that there were so many lions in the

world until that night.

The only book I had at hand that night was Lieutenant Colonel

J. H. Patterson’s famous thriller Man Eaters of Tsavo, a blood-

curdling account of the building of the railway from Nairobi to

Mombasa. Progress on the line was seriously delayed when many

of the workmen were devoured by man-eating lions. The men

were not safe even in the boxcars where they slept; the lions,

bold beyond belief, eventually jumped in and hauled them out

22

THE MUSIC HUNTER

into the night. Finally all the workers fled, holding up the laying

of the railroad for almost a year. Later when I recounted my

shattering experience on the Tsavo River to the son of the author,

Dr. Bryan Patterson, an eminent scientist at Harvard, he agreed

that his fathers book was not, under the circumstances, the best

inducement to sleep.

At Mombasa we boarded a small steamer en route from India

to England for our voyage to Beira in Mozambique (Portuguese

East Africa). In the harbor of Dar es Salaam, where we anchored

one night, I awoke in the morning insisting that I had heard the

roaring of lions. I was told that I was still dreaming the nightmare

of Tsavo, but when the captain came to breakfast he asked:

“Anyone hear the lions roaring last night?” I was vindicated.

Lions had come into the town during the night and had dragged

an Indian cabinetmaker out of his hut and hauled him off into

the bush. Such things could not happen in modern Dar es Salaam,

but on my first visit, the edge of the town was still bordered by

bush country.

I contracted my first bout of dysentery on that ship and arrived

in Mozambique feeling more dead than alive. But in Beira there

was a wonderful old man named Lawley who had been brought

from England by Cecil Rhodes as an engineer to help build the

mighty bridge over the Zambezi. Lawley had retired to Beira

and had built a small hotel called the Savoy where we all stayed.

He took me under his wing, and I was allowed to eat nothing

but boiled rice and drink nothing but the water in which the rice

was boiled. Everyone else was having penguin eggs shipped in

from Capetown, avocado salad, pawpaws, and other luscious trop-

ical foods which I longed to taste. However, the rice treatment

quickly restored me to life, and to this day it has never failed

to work its magic.

During our stay at the Savoy we were regaled with wondrous

tales by our host, fascinating reminiscences of those early bridge-

building days. He told us that when the bridge was finally com-

pleted, some dignitaries from England came for the official open-

ing, and one, not content with Lawley’s word as to the exact

height of the structure, was determined to prove it for himself

by the old method of holding a watch in one hand and dropping

a stone from the other, timing the fall. Mr. Lawley loved to

AFRICA

23

recount how this foppish gentleman opened the wrong hand and

“there he stood on the bridge, staring at a stone.”

From Beira we went by a tiny boat and a chugging biweekly

train to the Shire Highlands of Nyasaland where we stayed with

the director of railways at Limbe near Blantyre while arranging

our trip through Nyasaland to Mount Rungwe in southern Tan-

ganyika. With the help of our host and the government, we

assembled an excellent staff of five personal boys. From Limbe

we moved on to Zomba, then little more than a village nestling

under the shadow of Mount Zomba. Many parties were given

for us by the small European community there, and it was in

Zomba that I found the first piano I had come across in Africa.

I was kept playing and singing until the early morning hours.

The latest song hit was “My Blue Heaven,” and whenever I have

heard it since, I have been taken back to that evening and have

remembered our host firing the cook at three o’clock in the morn-

ing because the dinner was cold. (The cook was rehired the

next day.)

From Zomba to Mwaya in Tanganyika Territory we eventually

sailed on a small government mail steamer, the only water traffic

for the entire length of Lake Nyasa. The other passengers in

addition to our party were a judge and his three assistants on

their way to try a native murder case. Their folk tales and the

singing of our boys kept me busy recording throughout the jour-

ney. The most anxious moment of the trip came when, at the

head of the lake, we were put off on a sandy beach with our

mountain of gear, expecting to find porters awaiting us there.

All arrangements had been made through government headquar-

ters in Zomba, and porters were to have been sent to us by

Karosa, the paramount chief of this area. We had traveled some

five thousand miles to reach this isolated spot, the jumping-off

point for the real work of the expedition. No land has ever

looked so formidable or less welcoming to me. It was an un-

nerving moment when the boat steamed away leaving the mem-

bers of our expedition alone on that spit of sand without another

human in sight,' knowing that it would be a month before the

ship returned.

I was not so philosophical then as I am now, nor had I yet

heard the story later told me by Ronald V. C. Bodley, a

descendant, I was informed, of the founder of Oxford’s Bodleian

THE MUSIC HUNTER

Library, who lived for a considerable time in the desert while

preparing his two-volume work on the life of Mohammed. New

to desert life and still Western in moods and attitudes, he had

arranged to meet a famous s.heik at a certain time in the desert.

He waited all day and all night, all the next day and night, and

finally after three days the sheik appeared. Bodley, by now raging

with impatience and frustration, could not completely hide his

feelings. The sheik said to him: “What would you have been

doing if you hadn’t been here?’ “Nothing much, I suppose,

but . . The sheik interrupted: ‘Well, couldn’t you do nothing

much just as well here as there?”

This was our plight on the sandspit except that had we been

where we were going we would have been very busy indeed.

At last, toward sunset, our porters came straggling out of the

rim of bush beyond the beach. When our gear was finally loaded

—after much argument among the men as to who would carry

the lightest boxes in our mass of equipment—we set off to pay

our respects to Karos a. The chief s representative and several

tribal headsmen came in slow procession to meet us. Behind

them trailed troops of men, women, and children keeping a re-

spectful distance, but excited and curious. A white safari in this

remote part of central Africa, especially one with so many porters,

was quite an event. A white woman was cause for great excite-

ment.

Karosa had sent to me by his representative a gift of a beautiful

white goat, my first present from an African chief. Long afterward

I learned that according to the native etiquette of this tribe I

should have killed the animal on the spot and sent half of the

meat back to the chief. Instead I was so touched by this gesture

that I led the little goat many miles into the mountains of Tan-

ganyika, fording rivers and crossing slippery log bridges above

rushing mountain streams, but finally in one camp hunger over-

rode sentiment, and goat chops were added to our menu. My

breach of etiquette over the goat was apparently overlooked by

Chief Karosa—a fortunate thing, for we were dependent upon

him for our porters and their food supply.

On arrival in the village, we were astonished that the ancient

Karosa himself appeared to greet ns, carried to his throne chair

on the back of a strong young girl; we were told later that this

was the special privilege of the youngest wife. He was the oldest

AFRICA

25

living creature I have ever seen. His body was shrunken and

wrinkled, but from his wizened face shone a pair of vigorous

and cunning eyes. The success of our trip up Mount Rungwe

depended on winning the friendship of this important chief. After

exchanging formal greetings through interpreters, we said that

we would like to present some small gifts. I had brought with

me tire most gorgeous colored baubles I could find, the best

Mr. Woolworth had to offer, and I asked the chief to select one

for his favorite wife.

His eyes glinted. With one swift movement he took the box

from my hands saying: “I have many wives ” With that my entire

treasure, with which I had hoped to make friends and influence

people throughout the length and breadth of Africa, was gone.

I find tliis amusing now. Then it seemed a major tragedy. After

polite conversation and the exchange of other gifts, Karosa gave

us a guide to a temporary camping place in one of his banana

groves nearby. While we were pitching camp, the chief sent a

dozen men carrying bunches of plantains (large green bananas)

which, roasted in their skins deep in the coals of the campfires,

provided a delicious meal.

I had never before fully appreciated the beauty and usefulness

of the banana plant. Here in the northern Nyasa region the

banana was a most essential commodity, and these graceful plants

with their broad, drooping leaves, wine-colored flowers, and

bunches of green and yellow fniit were everywhere. Apart from

the fruit providing the Africans with their basic diet, the leaves

of the tree supplied thatching for their huts, umbrellas against

the rain (the African cannot stand being wet and cold), material

for “skirts,” and they served as wrapping paper and as covers

for bamboo milk containers. The leaves were also used as seats,

beds, and pads of many sorts. Wilted over the fire, they made

han^v drinking cups.

The trunk of the banana tree provided the resonator for the

natives’ favorite instrument, a primitive xylophone. I brought back

to the Carnegie Museum one such instrument—which was hu-

morously described by a music critic as “a good old woodpile

xvlophone made of young railroad ties.” The “railroad ties” are

kevs made from a light wood and cut into pieces about two

inches wide, varying in length from one and a half to three

feet. These keys, or staves, usually five to nine in number, are

гв

THE MUSIC HUNTER

placed on “trunks” of banana trees, freshly cut for each occasion,

as resonance is lost when the trunk dries. Each key is accurately

tuned by chipping away tiny flakes of wood, and held in place

by small pegs driven into the trunk. Two boys seat themselves

on either side of the huge unwieldy instrument and play it by

striking the keys with small wooden bearing sticks. They play in

syncopated rhythms, and the liquid tones of the keys produce

strangely sweet music.

I still have vivid memories of our first night camped in Karosa’s

banana grove. Our boys were singing at their tasks, the bivouac

fires of the porters glowed among the trees, the special guard

provided in our honor by Karosa paced up and down proudly

with a brightly polished gun on his shoulder, his shadow, thrown

by the campfires, stalked silently beside him. During the night

our camp was invaded by a battalion of soldier ants on the

march, an invasion no gun could stop. There was no sleep for

anyone until these tenacious insects had been driven away by

the old native method of slowly scorching with bundles of lighted

grass every inch of ground around the camp.

It was a hard trek from the banana grove to Tukuyu, and it

took us several days to cover the fifty-mile distance, camping

en route. This southernmost government post at the foot of Mount

Rungwe was our first objective in Tanganyika, and the trip to

reach it was lightened by the porters' rhythmic singing. In Tukuyu

I made some of the favorite records in my collection, songs sung

by a splendid old man, totally unspoiled and an excellent singer.

While singing exuberant songs he accompanied himself on a small

African zither held under his left arm and plucked with his left

fingers. At the same time, he danced brandishing a spear in his

right hand. When I played the recording back to him he was

beside himself with joy. Through my interpreter he said: “Now

I have heard myself sing, I would like to see myself dance/’ for

we had also filmed his performance. I was in a quandary. How

could we make this child of nature understand that the motion

pictures had to travel thousands of miles back to America to be

treated with white mans medicine before they could be seen?

Although disappointed and not at all convinced, he did not stop

singing and his songs are among my treasures. They created

great interest when the wax cylinders were copied recently by

the Thomas Edison Rerecording Laboratories.

AFRICA

27

I seem to have lived through the history of recording for I

think I have tried every method and material known. I did not

dream that the melodies I captured on that early, glorified Edison

recorder would be of interest to the world in general. For African

flutes or a single voice, this machine was surprisingly good, but it

co’dd not take the volume produced by a chorus or an orchestra

of drums. When I returned to Africa on the Straus West African

Expedition I had much more adeouate equipment, especially de-

signed for me by engineers of Columbia Broadcasting System,

thanks to a generous grant from Carnegie Corporation of New

York. The recording was done on big aluminum discs thickly

coated with heavy grease, really an embossing process. Then

came the first commercial portable machine, the Presto, cutting

acetate-covered aluminum discs. The wire recorder I did not trust

for use in the field: the wire tangled and was easily stretched

producing a "wow.” Then came tape, a real godsend! The first

good field recorder for tape was the Magnacorder; the president

of the company presented one to me for my first trip around the

world. The results were excellent but it was cumbersome with

two cases weighing nearly fifty pounds each, requiring heavy

duty batteries. Finally came a tape recorder which is an answer

to nmver—it is the Nagra, invented bv Kudelski in Lausanne.

Thn isolated government post at Tnkuvu had only three British

officials, one with a wife and child. Their dav began in the early

morning dealing with native affairs (everything from theft to

susnected witchcraft), and the late afternoons were devoted to

tea and tennis followed by hot baths and “sundowners” (usually

soot-ch and soda). The day ended with dinner in formal dress

(Ь'аск tie and long gowns); the farther from civilization an out-

post might be, the more rigid was this rule. Dav after dav the

ro”Hne was the same. Perhaps when there were no guests they

mi^ht have spent an evening alone, but when we were at the

post there was little rest, for visitors were rare and new faces

m°^nt new conversation and word from the outside. These British

ofRninIs were doing a wonderful job in the area, and they were

bevond words in helning me find musicians to record, s”ch

as Hie old man and his excellent songs, and in helping to start

our entire party on its way to Mount Rungwe.

In Tukuyu we also met a wonderful old German Lutheran

missionary whose hospital had served the local population for

28

THE MUSIC HUNTER

many years. He had great scientific knowledge and a splendid

library about the area, which he made available to us. We dis-

covered that he was very disturbed about a new mission which

had recently been built in the shadow of his own by a highly

emotional American religious sect. This form of religion had im-

mediate appeal to the exuberant Africans, and the congregations

were flocking from the old church to the new. To make matters

worse, an American woman with more dollars than knowledge

of the African interior had "felt the call,” packed hundreds of

Greek Testaments, scores of writing pads, pencils, pens, and story-

books, and had set sail to establish a school for the new sect.

When we arrived in Tukuyu the matter had practically become

an international issue. We heard after we had left that there

had been a fire in which the new mission was destroyed. Whether

this was accidental or by divine interference, the crisis was passed

and orthodoxy restored. This could not happen today because

missionaries are thoroughly screened by very strict boards and

the standards required are high.

From Tukuyu we began the climb up Mount Rungwe, an ex-

tinct volcanic mountain so isolated that it had never before been

explored by a scientific expedition, and I was, I was told, the

first white woman to climb to its summit. At the beginning of

our ascent we followed small paths made by the local woodcutters

who penetrated the forest of the lower mountain, but after three

thousand feet we had nothing but animal trails to follow. The

only means of crossing rushing mountain streams was by fallen

trees slippery with moss, or by native bridges of bamboo bound

together with lianas, often so fragile that I marveled that they

held together while our stream of a hundred carriers jogged across

with their heavy loads. The ordinary load for each was sixty

pounds, but many begged to be given a double load in order to

have double pay and food. Twenty men were needed just to

carry food for themselves and the other eighty.

In the course of my twenty-eight expeditions I have lived die

history of transportation—traveling by native dugout canoes and

little rafts poled by bamboo poles; by Greek donkeys, Tibetan

ponies, and Nepalese dhan di (primitive sedan chair); by African

camel, Indian elephant, and Eskimo dog sledge; ultimately by

truck, jeep, helicopter, and jet. And still my favorite method of

travel, especially in Africa, is on foot. I have trekked hundreds

AFRICA

29

of miles into the mountains, through the bush, and across the

plains. Only in this way does one feel close to the people, see

every flower, know every scent, hear every bird; a marvelous

way of making friends with a strange country . . . and best of all,

the porters always sang to make the load lighter, improvising

new songs or singing ancient songs that belonged to the former

days of trade caravans crossing the continent.

On this march the porters sang constantly as we climbed into

beautiful rain forest where mahogany trees, nine and ten feet in

diameter reached a height of one hundred eighty feet. They were

covered with thick trailing creepers that made the forest so dense

that even at midday we were walking through tunnels of deep

green gloom, forcing our way through lianas, thick entangling

vines which draped themselves from tree to tree making a solid

wall of growth. Curious monkeys, black and white colobus and

blue Sykes, swung and bounded overhead, and their chatter pro-

testing our presence reverberated eerily through the trees.

At the beginning of the steep climb the porters began a wonder-

fully vigorous song with each verse imitating a different animal,

starting with the fleet gazelle, and going through every species

they knew until finally, at the end of the day when they were

near exhaustion, they sang: ‘T am the slow-creeping snail. Shall

I ever reach my goal?”

We were interested in making observations and collections in

every zone of life at various altitudes on Mount Rungwe. Above

the lifezone of the savanna (bush), there was a zone of forest

in the foothills up to about three thousand feet, another up to

six thousand feet where giant trees towered to nearly two hundred

feet and moss-bearded tree fems grew to a height of over twenty

feet, and finally a zone of bamboo, rearing straight and slender

fifty feet into the sky, marking the tree line at approximately

nine thousand feet, with the scrubby alpine zone reaching to the

summit. The bird and animal life changed as dramatically with

each zone as did the vegetation; the various belts were almost

as clean-cut and distinguishable as though there were actual walls

between them.

We made our base camp on Mount Rungwe at six thousand

feet on the only level space available, right in the heart of the

rain forest. I felt very small and insignificant hemmed in on all

sides by enormous wonders of nature. The trees seemed to scratch

30

THE MUSIC HUNTER

tiie sky and the undergrowth was so dense that it took hours to

make a clearing big enough for our tents, worktables, campfire,

and space for the “kitchen” area and the boys’ canvas shelter.

The smell of the deep wet foliage, the humid air, heavy and

dank, and the pungent scent of moldy decaying leaves and plants