Похожие

Текст

A Historical Atlas

./TIBET

KARL E. RYAVEC

Karl E. Ryavec is associate professor of world heritage at the University of California,

Merced.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

© 2015 by The University of Chicago

AH maps © 2015 Karl E. Ryavec

All rights reserved. Published 2015.

Printed in Canada

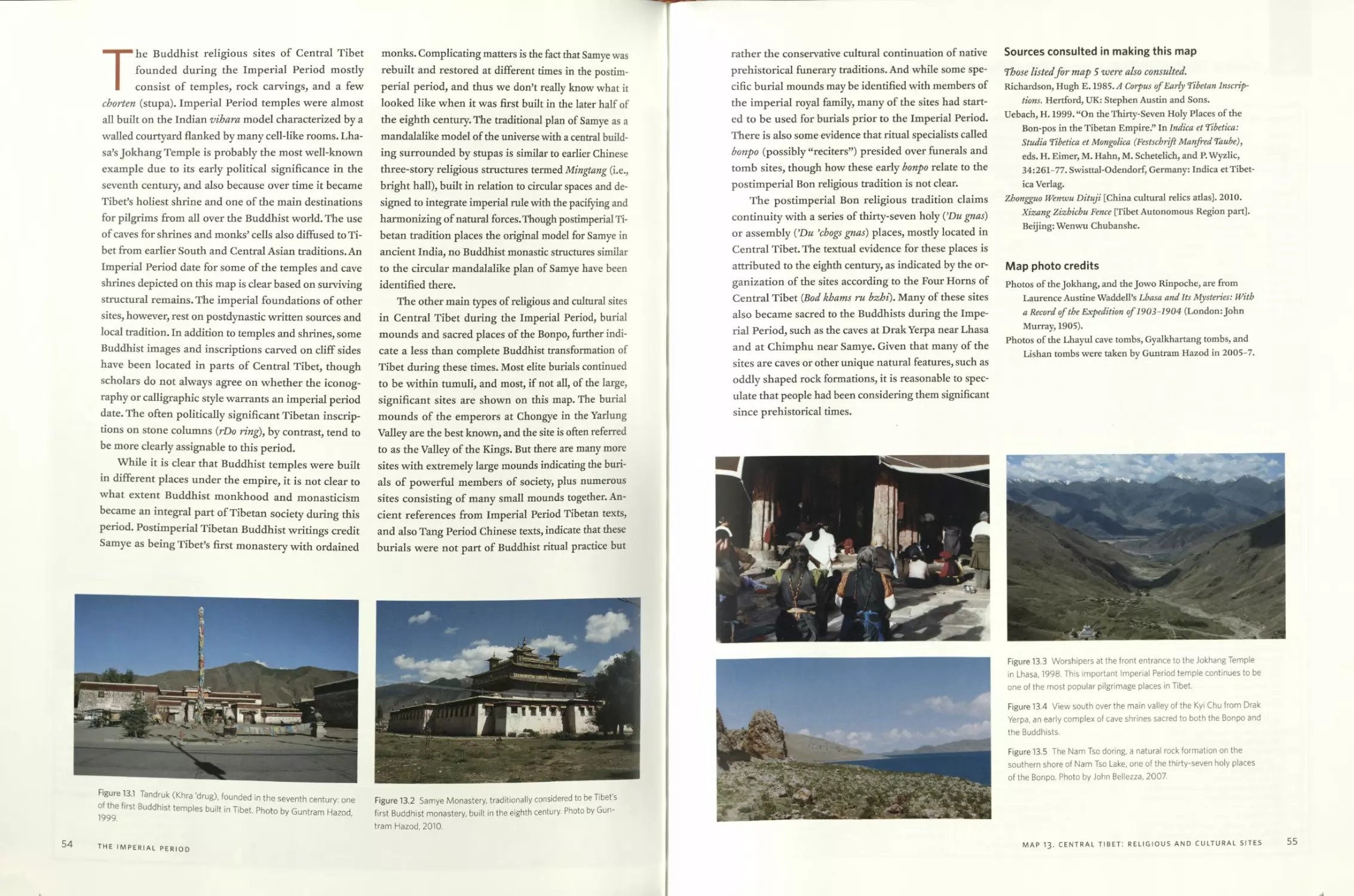

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13:978-0-226-73244-2 (cloth)

ISBN-13:978-0-226-24394-8 (e-book)

DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226243948.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Ryavec, Karl E., author.

A historical atlas of Tibet / Karl E. Ryavec.

pages cm

© 2015 by The University of Chicago.

All maps © by Karl E. Ryavec.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-73244-2 (cloth : alk. paper) - ISBN 978-0-226-24394-8 (e-book) 1. Tibet

Autonomous Region (China)—Historical geography—Maps. 2. Tibet Autonomous Region

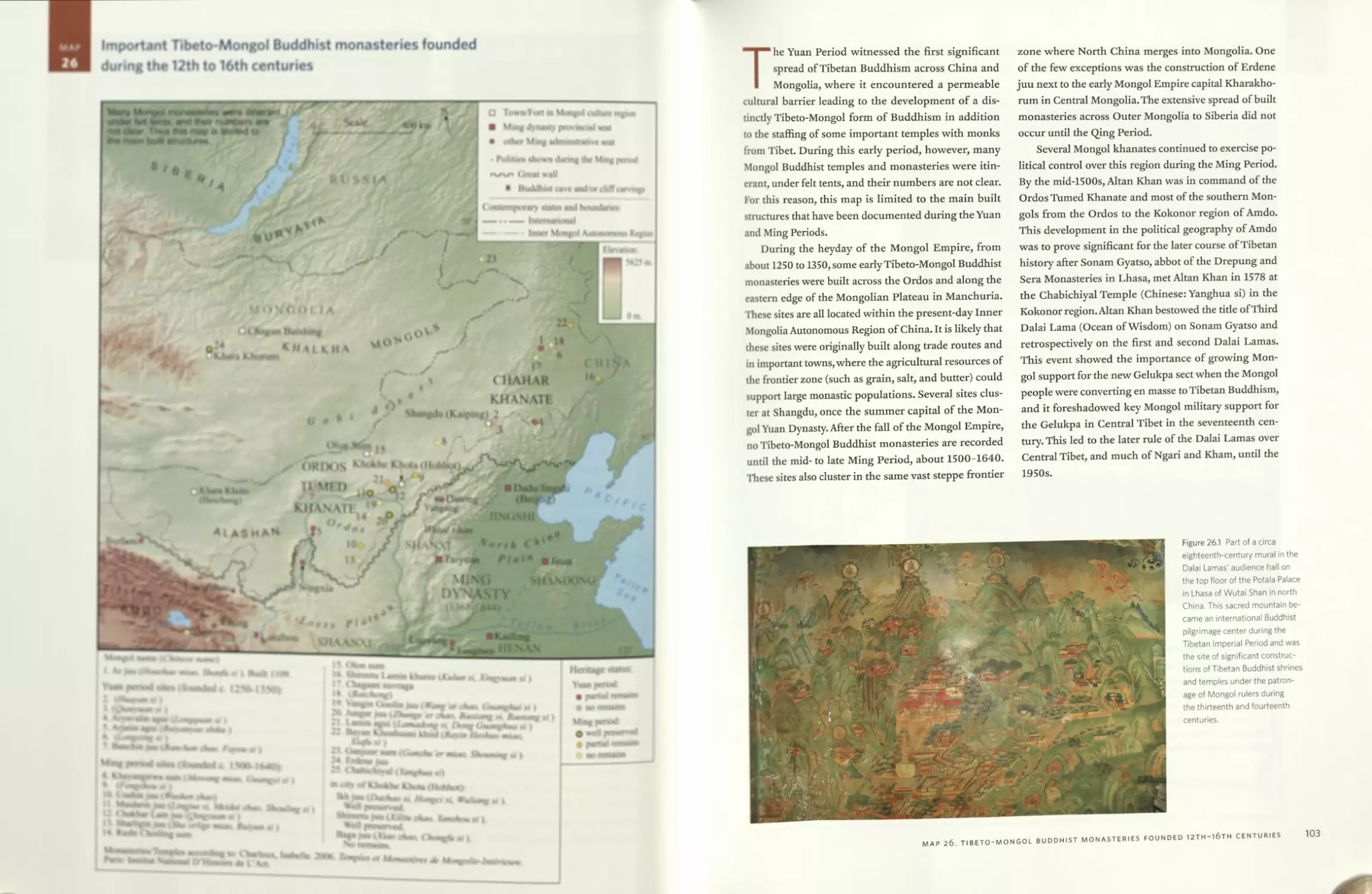

(China)—History—Maps. I. Title

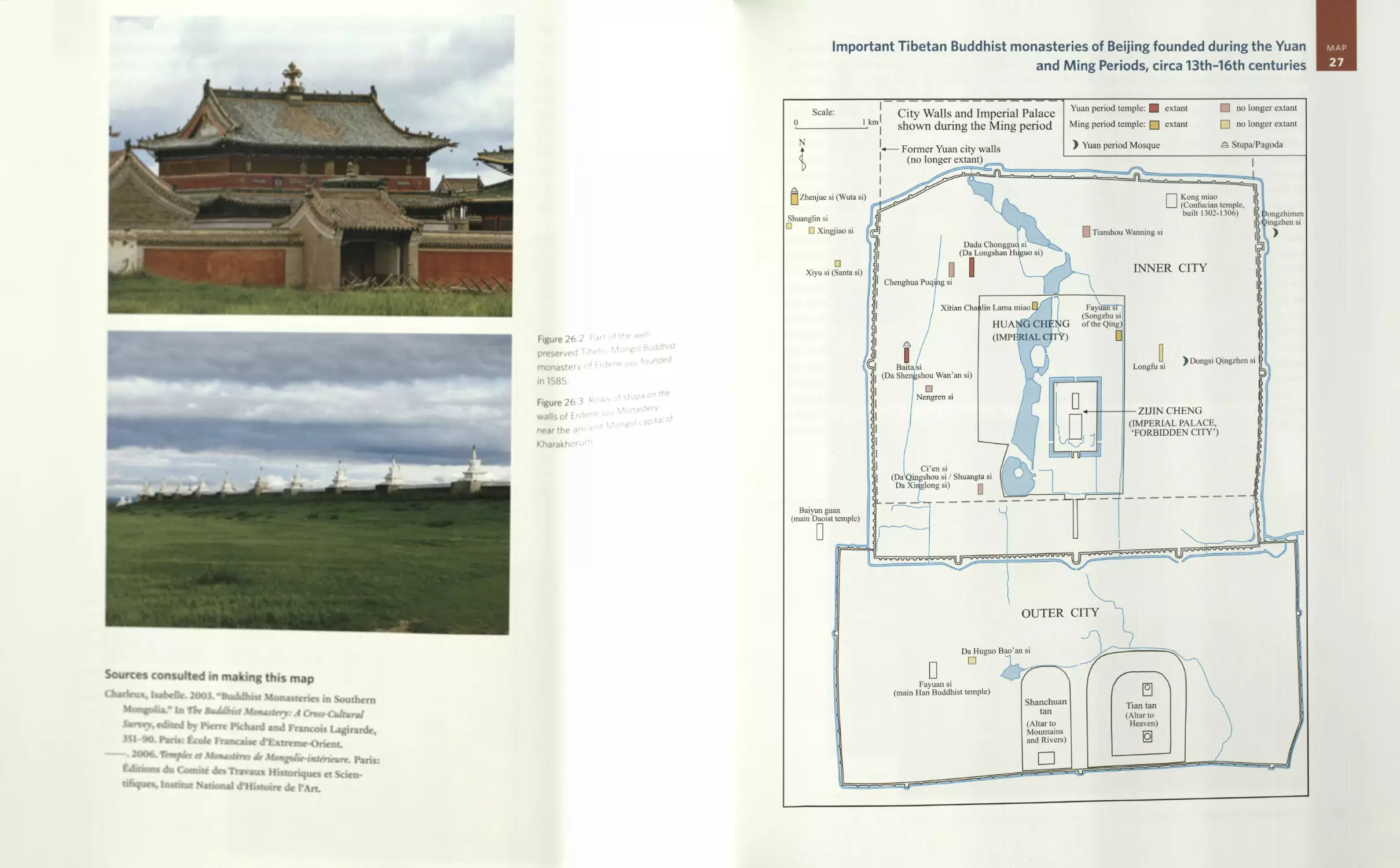

G2308.T5R9 2015

911'.515—dc23

2014038399

@ This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To my parents

CONTENTS

Preface xiii

Notes on Gazetteer: Phonetic and Literary Romanization xv

A Note on Sources xvii

INTRODUCTION

Map 1 Tibet and the Tibetan culture region 3

Map 2 Tibet and surrounding civilizations 4

Map 3 Major regions and natural features of Tibet 6

Map 4 Tibetan macroregions 11

Map 5 The structure of Tibetan history: Core regions, peripheries, and

trade networks circa 1900 12

Graph of the growth of Buddhist temples and monasteries in core

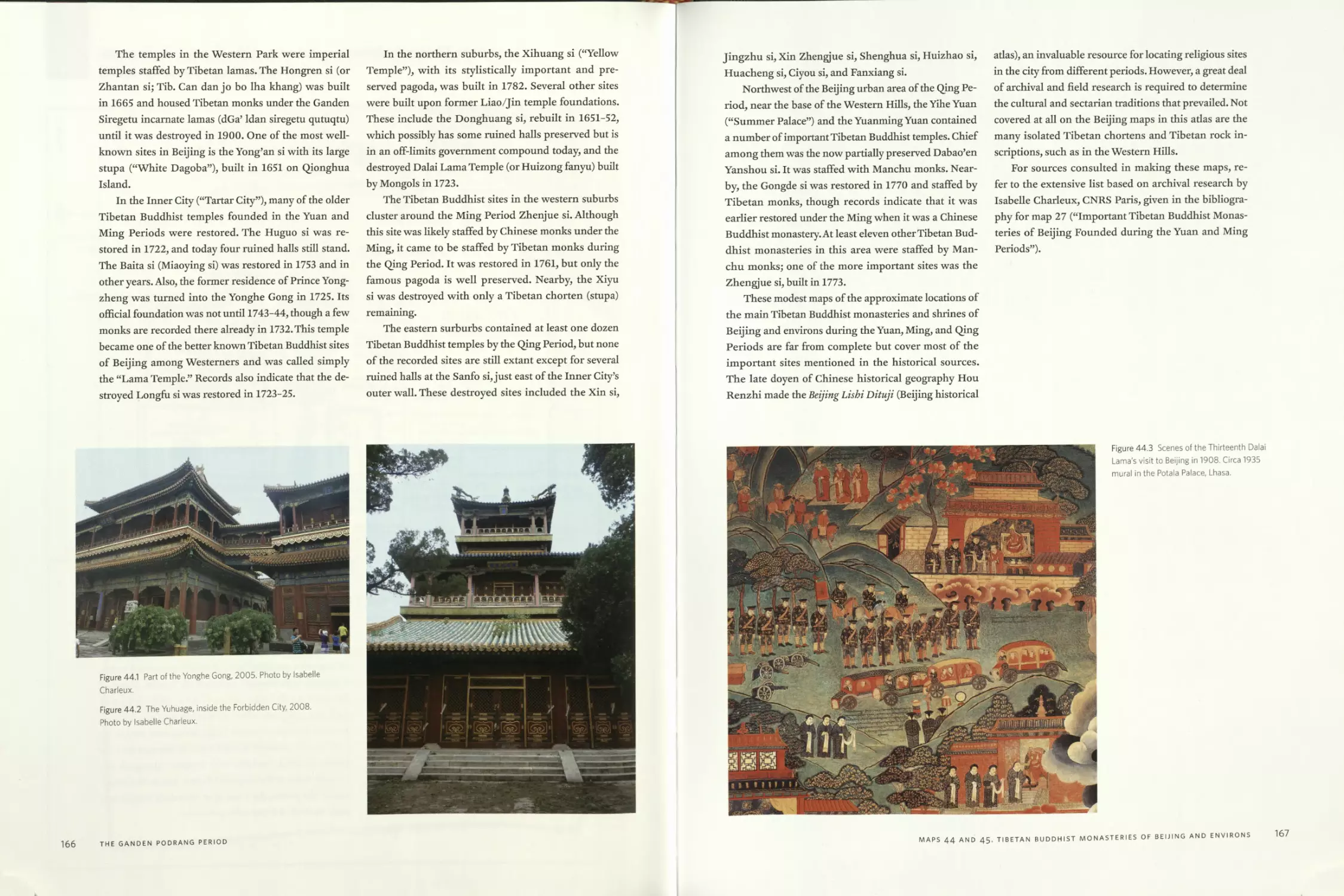

regions ca. 600-1950

Map 6 The historical Tibetan world: Travel time and main trade patterns

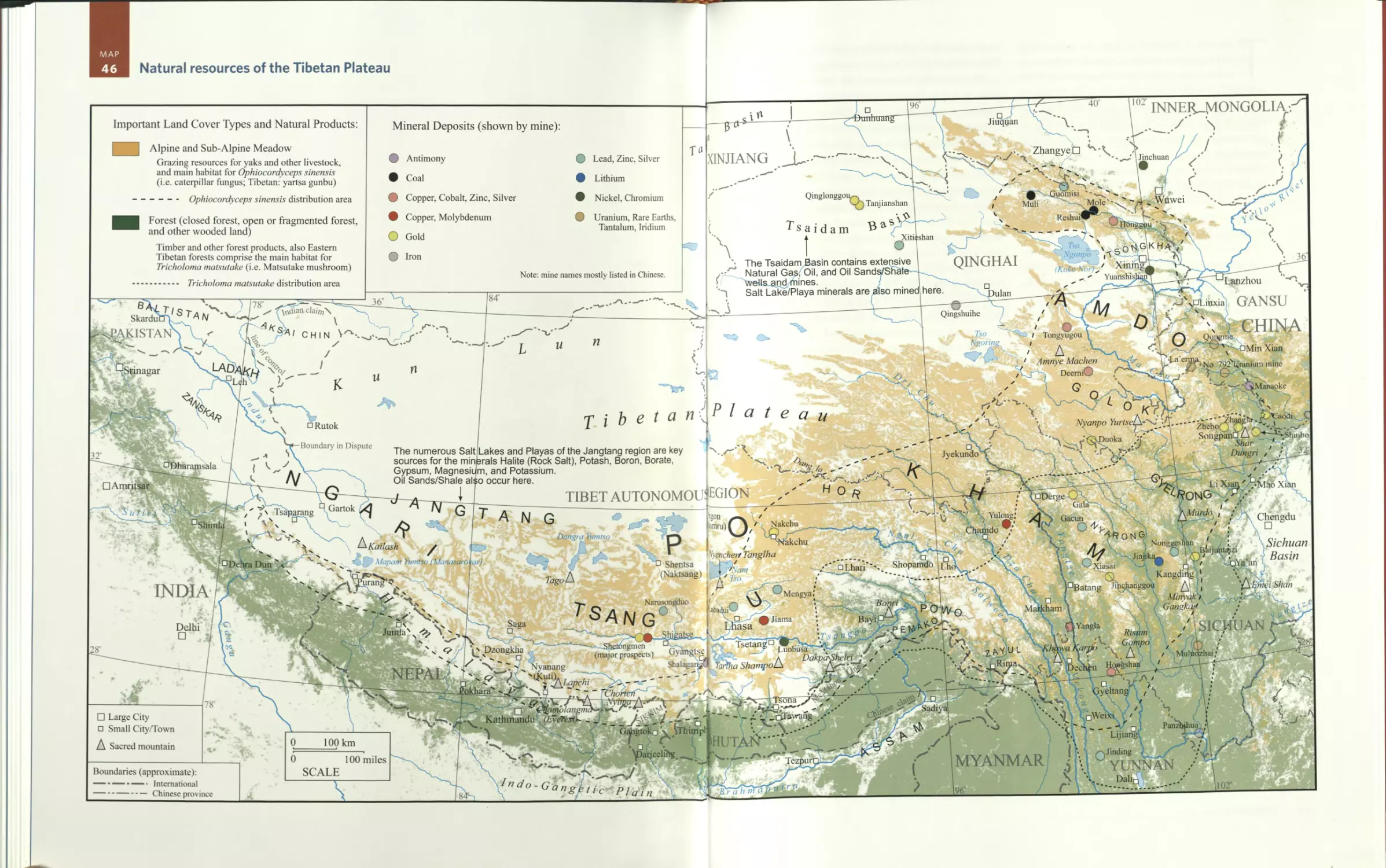

circa 1900 18

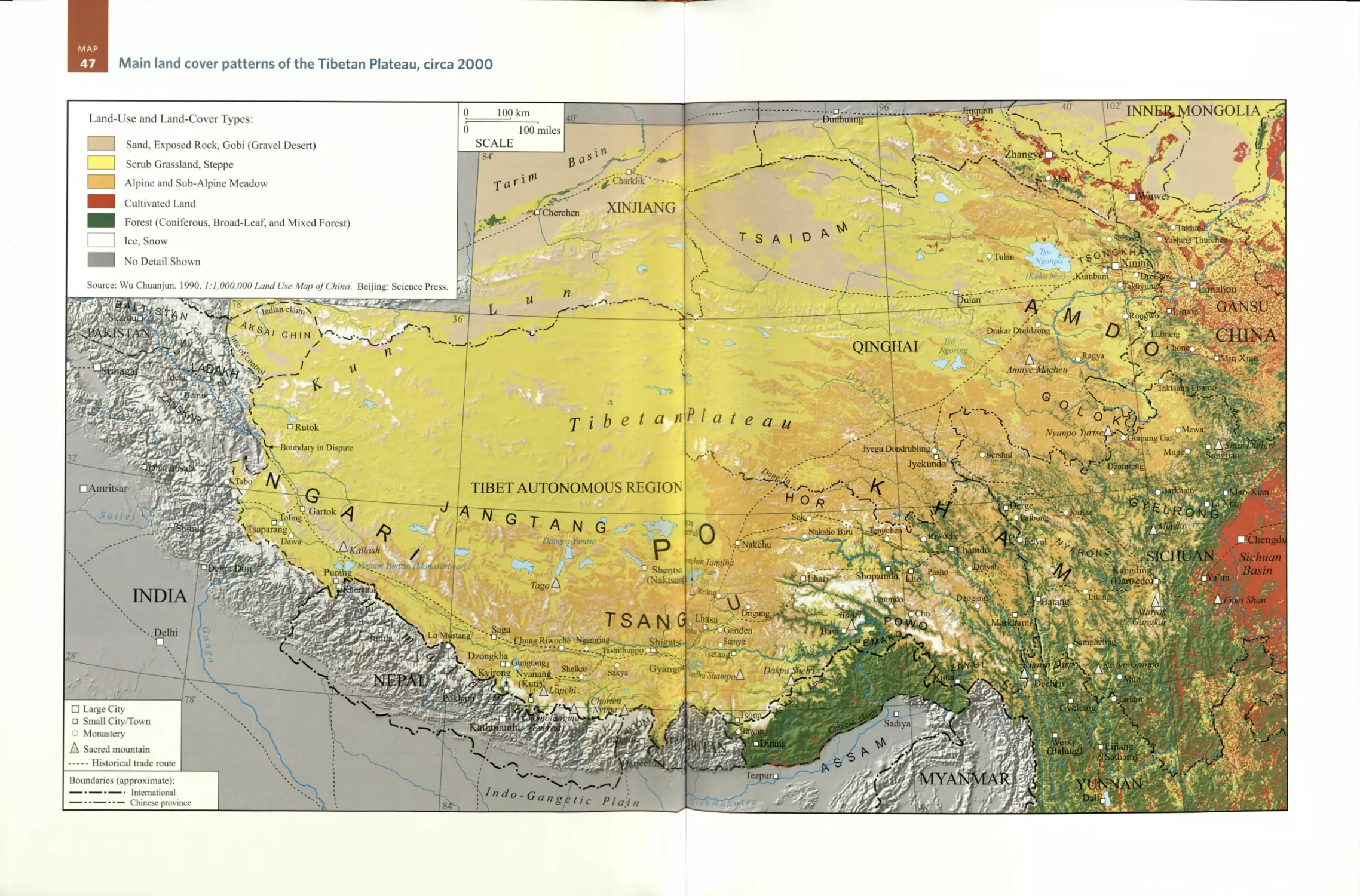

Table 1. Long-distance trade items listed in the Yushu Diaocha Ji

(Yushu investigation record), 1919

A brief overview of the use and production of money in Tibet

Map 7 The Tibetic languages 26

Table 2. The Tibetic languages

Map 8 How to use this adas: Map coverage and cartographic

conventions 30

PART 1

The prehistorical and ancient periods, circa 30,000 BCE to 600 CE

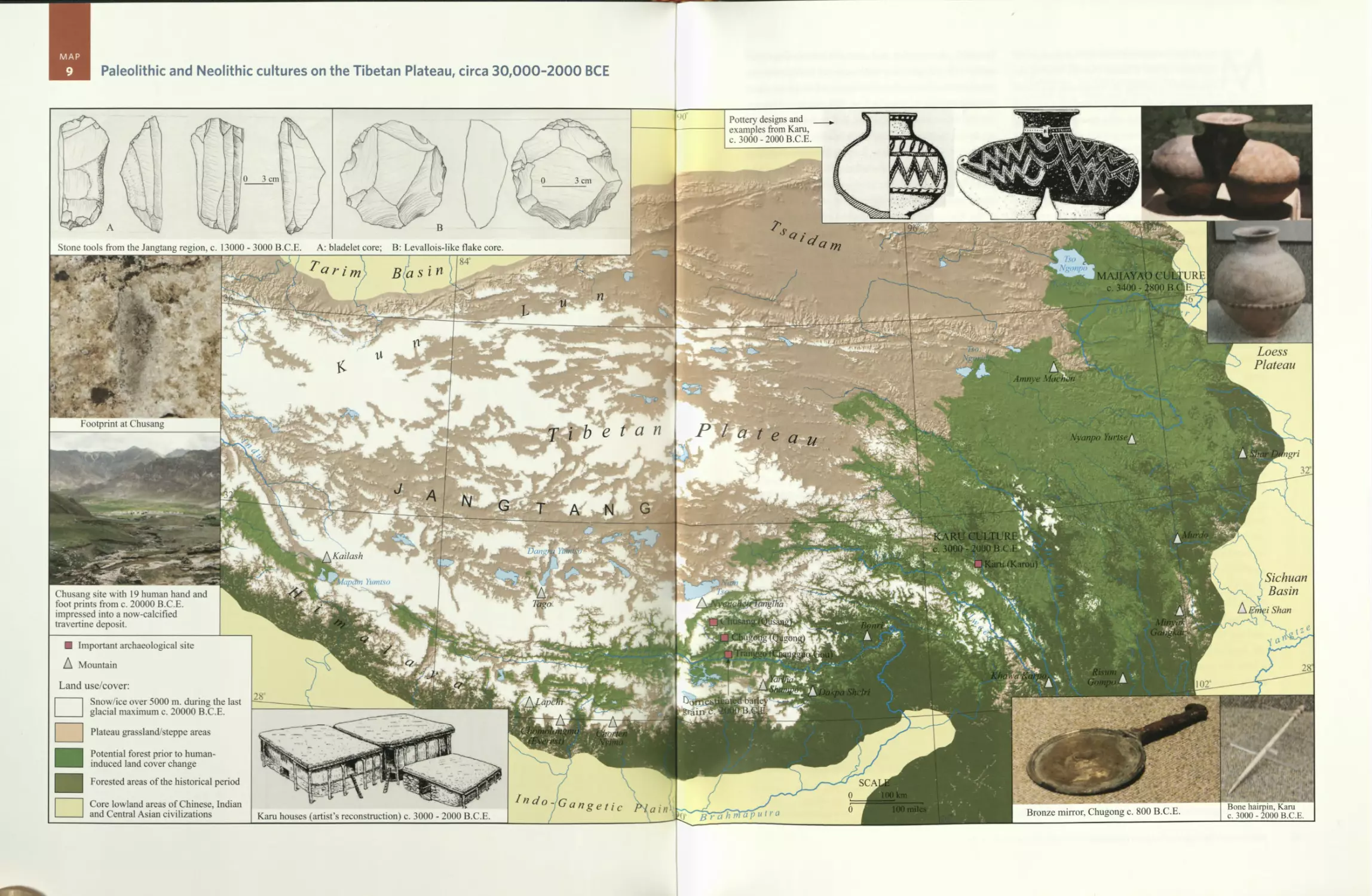

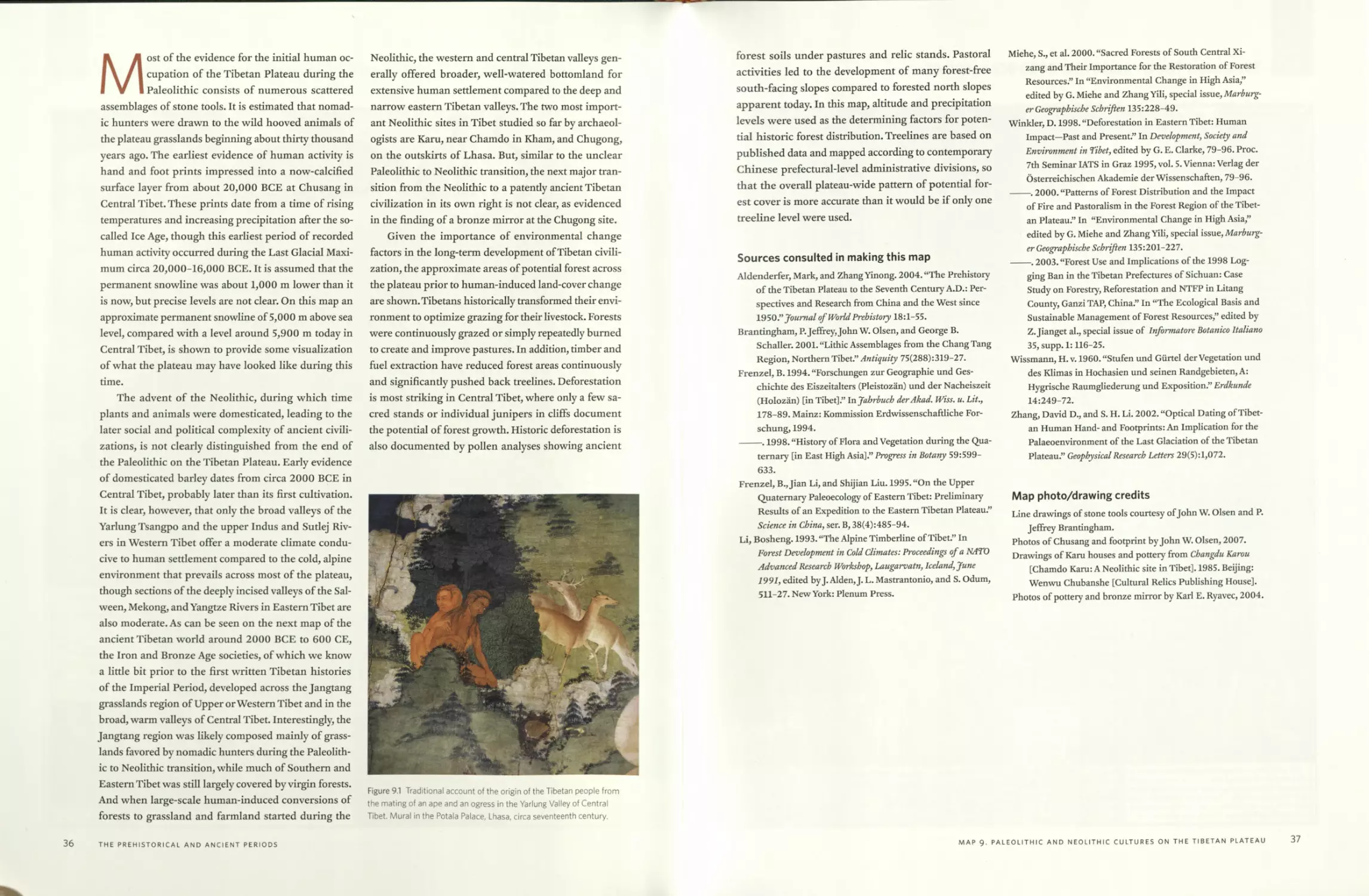

Map 9 Paleolithic and Neolithic cultures on the Tibetan Plateau, circa

30,000-2000 BCE 34

vii

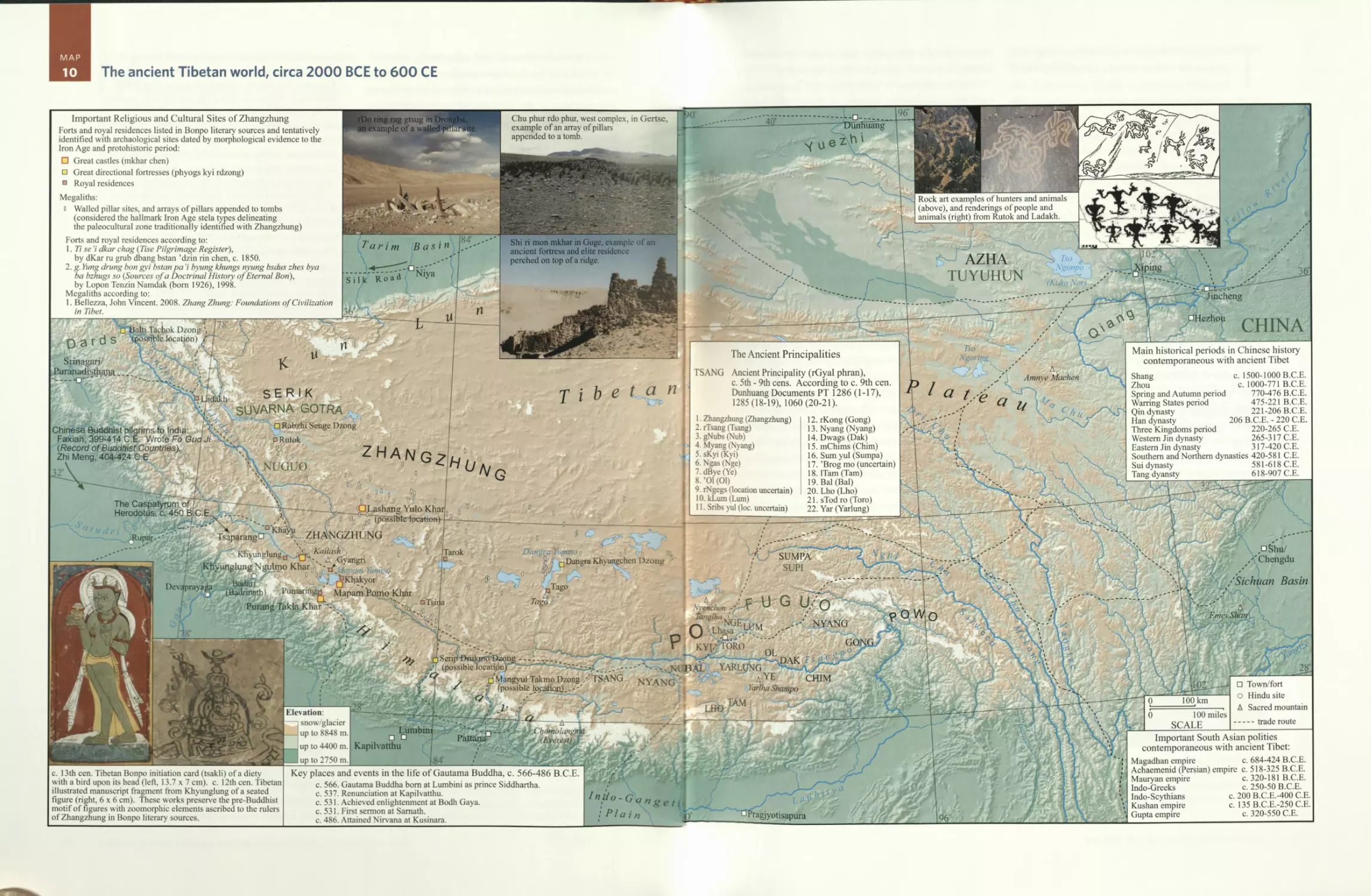

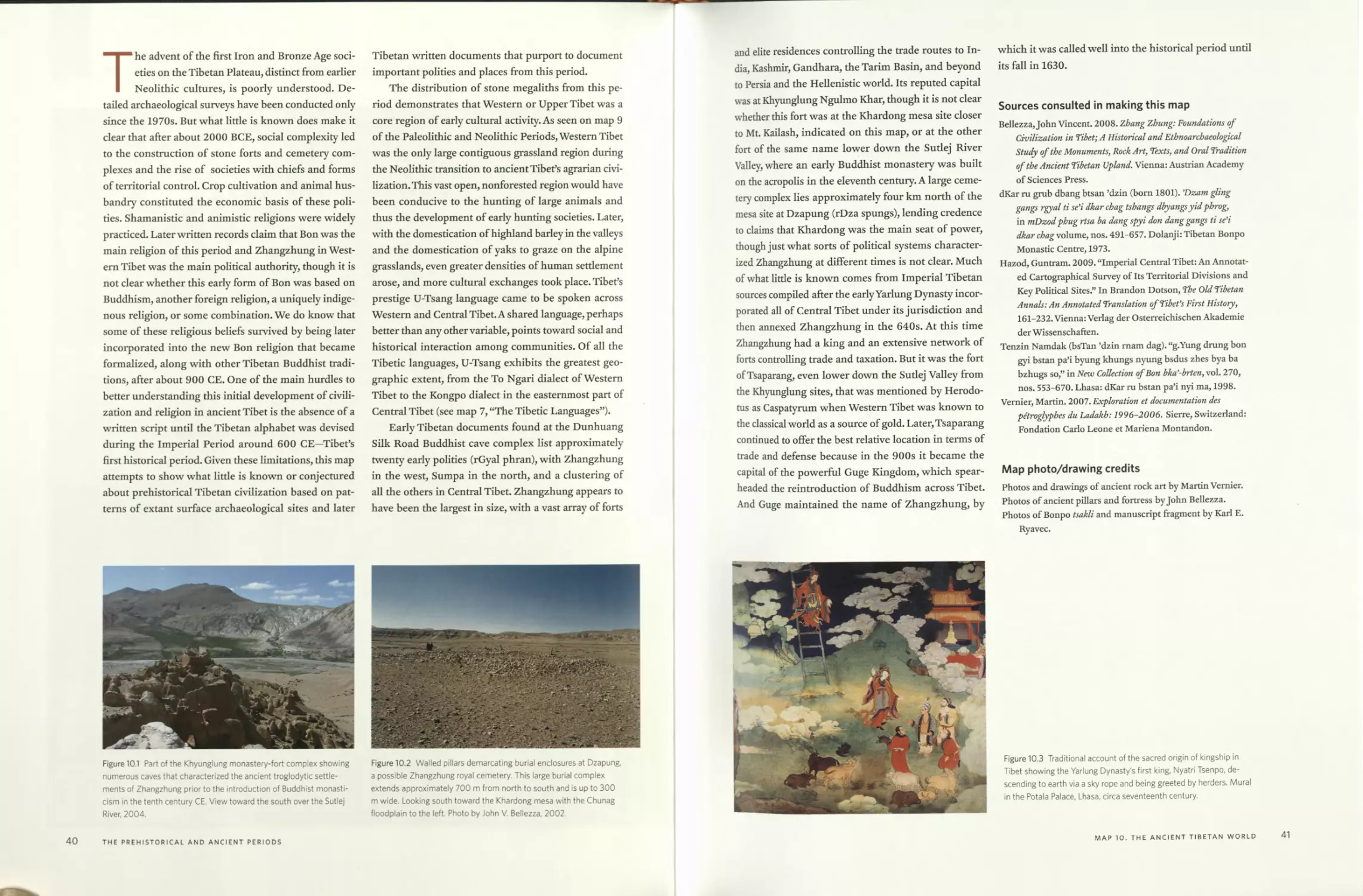

Map 10 The ancient Tibetan world, circa 2000 BCE to 600 CE 38

Forts and royal residences listed in Bonpo literary sources

Ancient principalities {rGyalpbran) according to circa 9th-century

Dunhuang documents

PART 2

The Imperial Period, circa 600-900

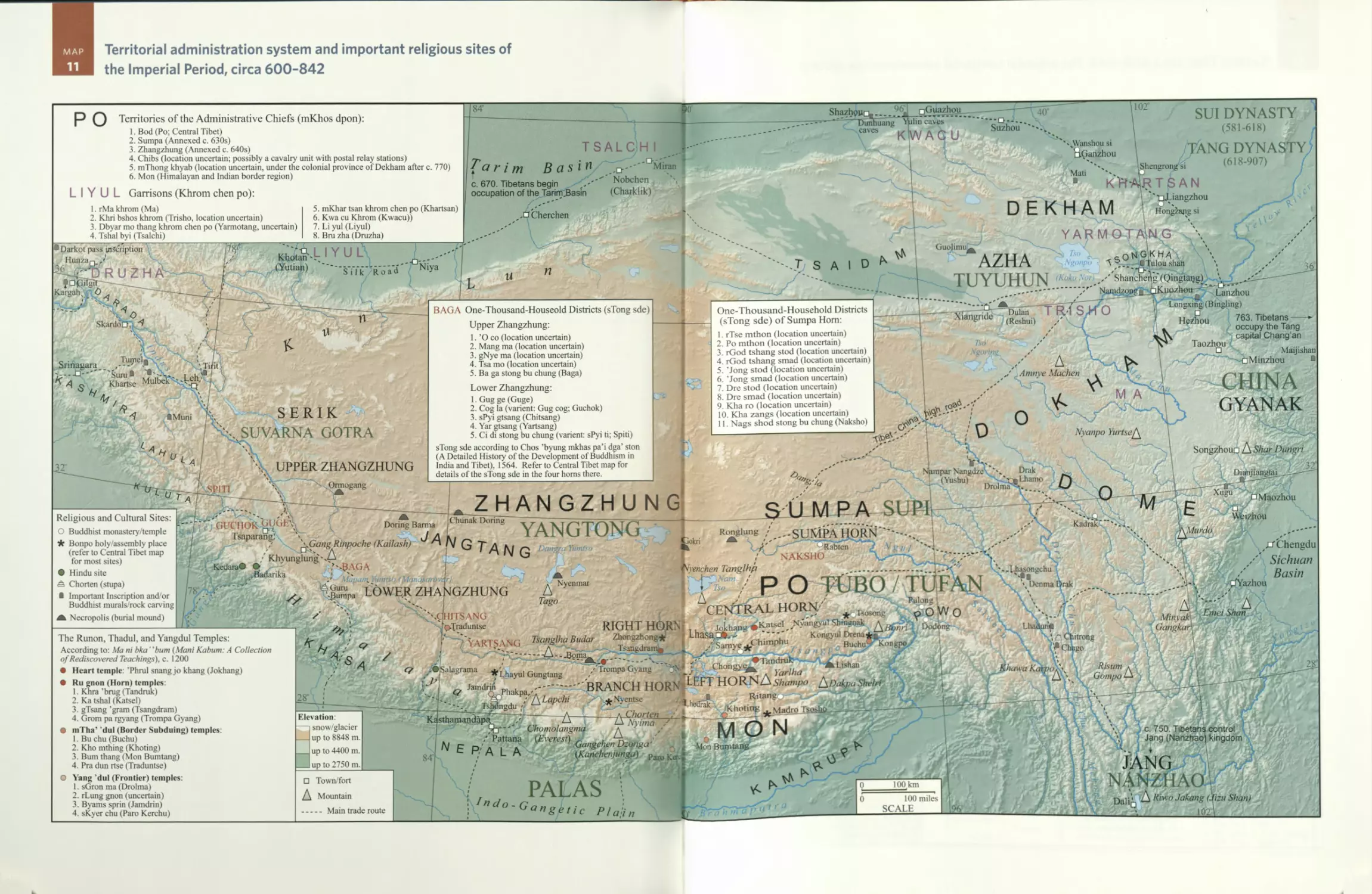

Map 11 Territorial administration system and important religious sites of

the Imperial Period, circa 600-842 44

Territories of the administrative chiefs {mKbos dpon)

Garrisons {Kbrom cben po)

The one thousand household districts {sTong sde) of Upper

Zhangzhung, Lower Zhangzhung, and Sumpa Horn

The Horn (Ru), Border Subduing (mTha’ ’dul), and Frontier (Yang

’dul) Temples

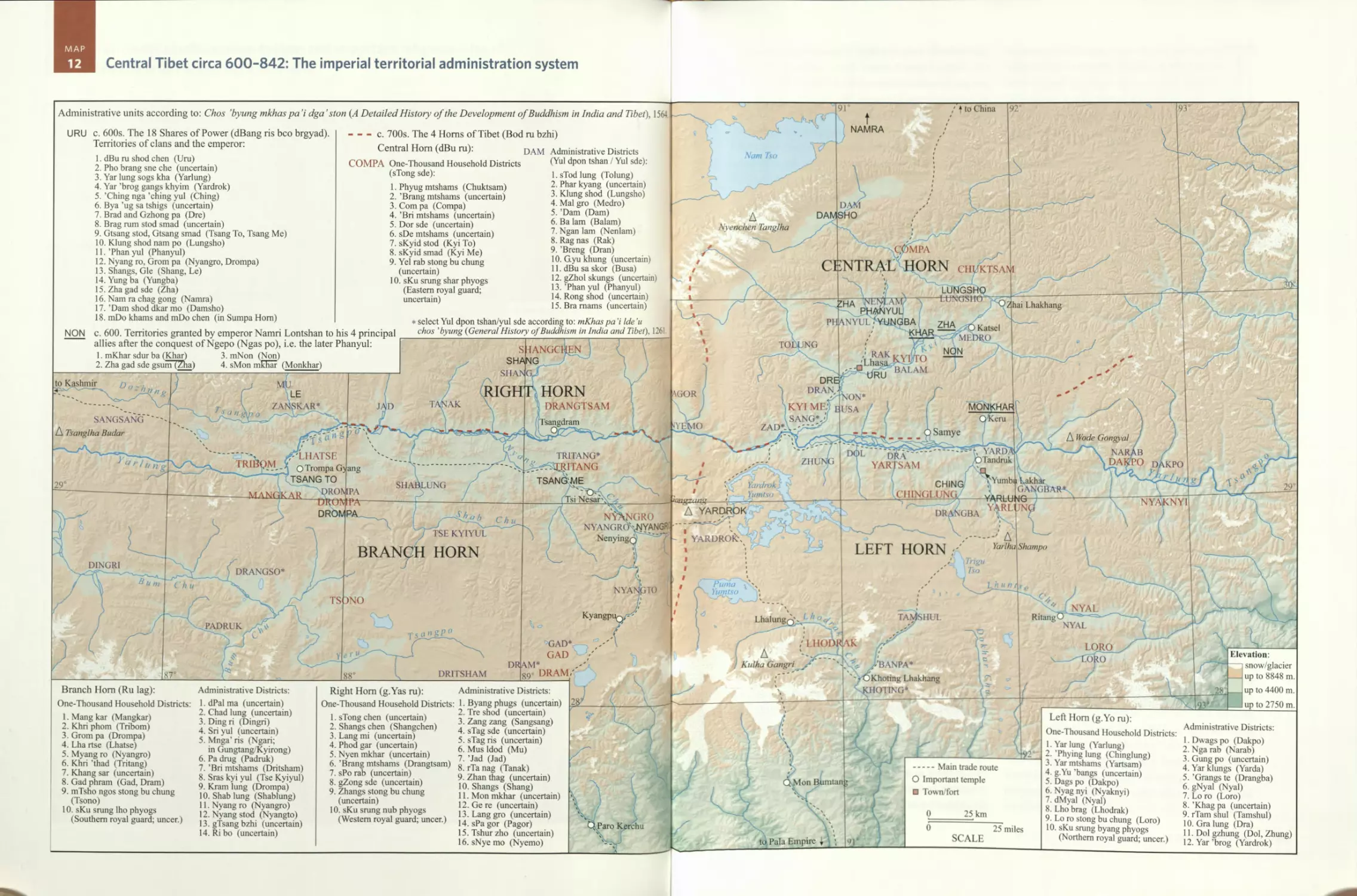

Map 12 Central Tibet circa 600-842: The imperial territorial

administration system 46

The Eighteen Shares of Power {dBang ris bco brgyad)

The Four Horns of Tibet {Bod ru bzbi)

The one thousand household districts {sTong sde) and administrative

districts {Yul dpon tsban / Yul sde) of Central Hom, Right Hom,

Left Horn, and Branch Hom

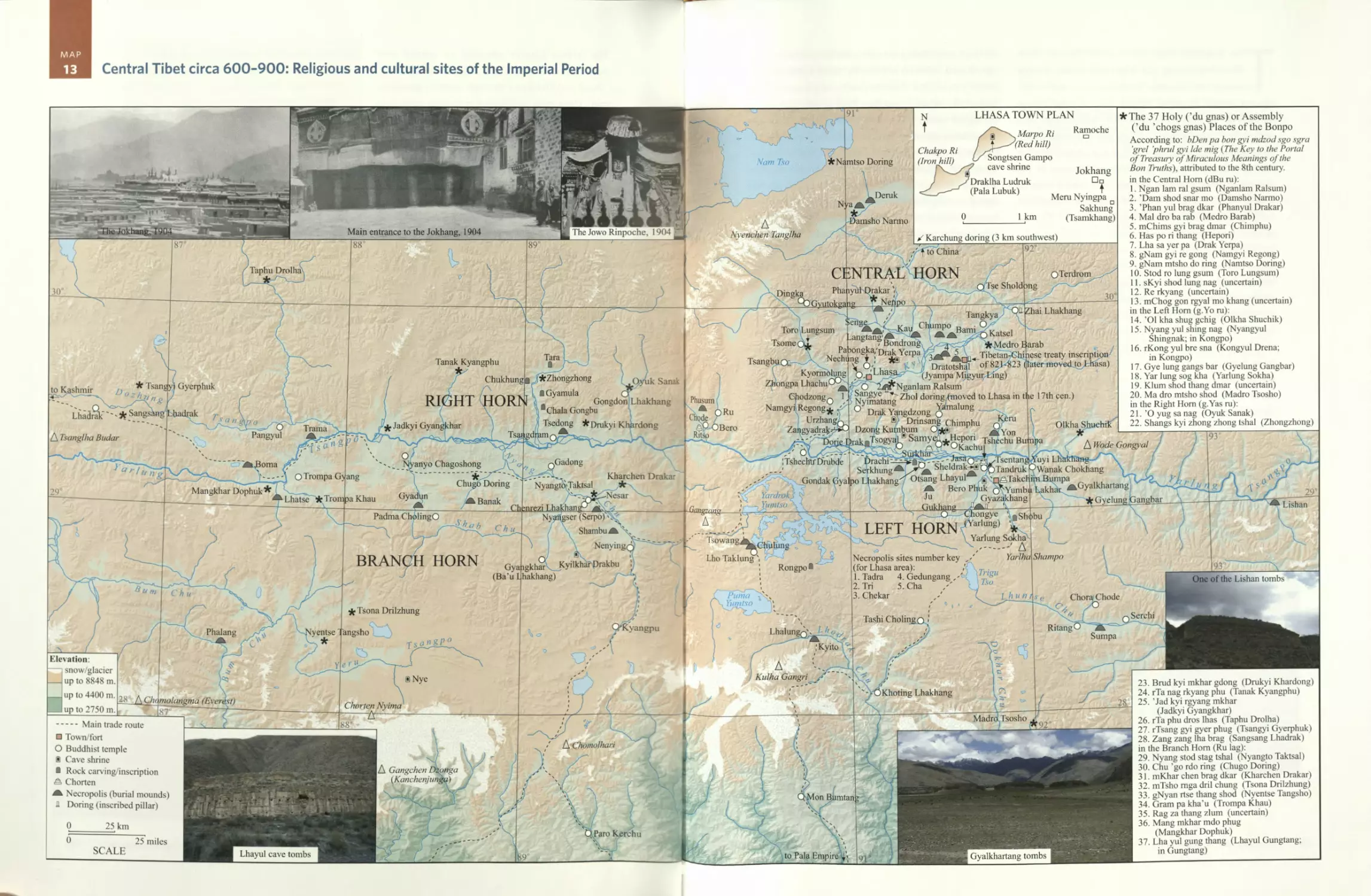

Map 13 Central Tibet circa 600-900: Religious and cultural sites of the

Imperial Period 52

Lhasa town plan

The thirty-seven holy/assembly places of the Bonpo

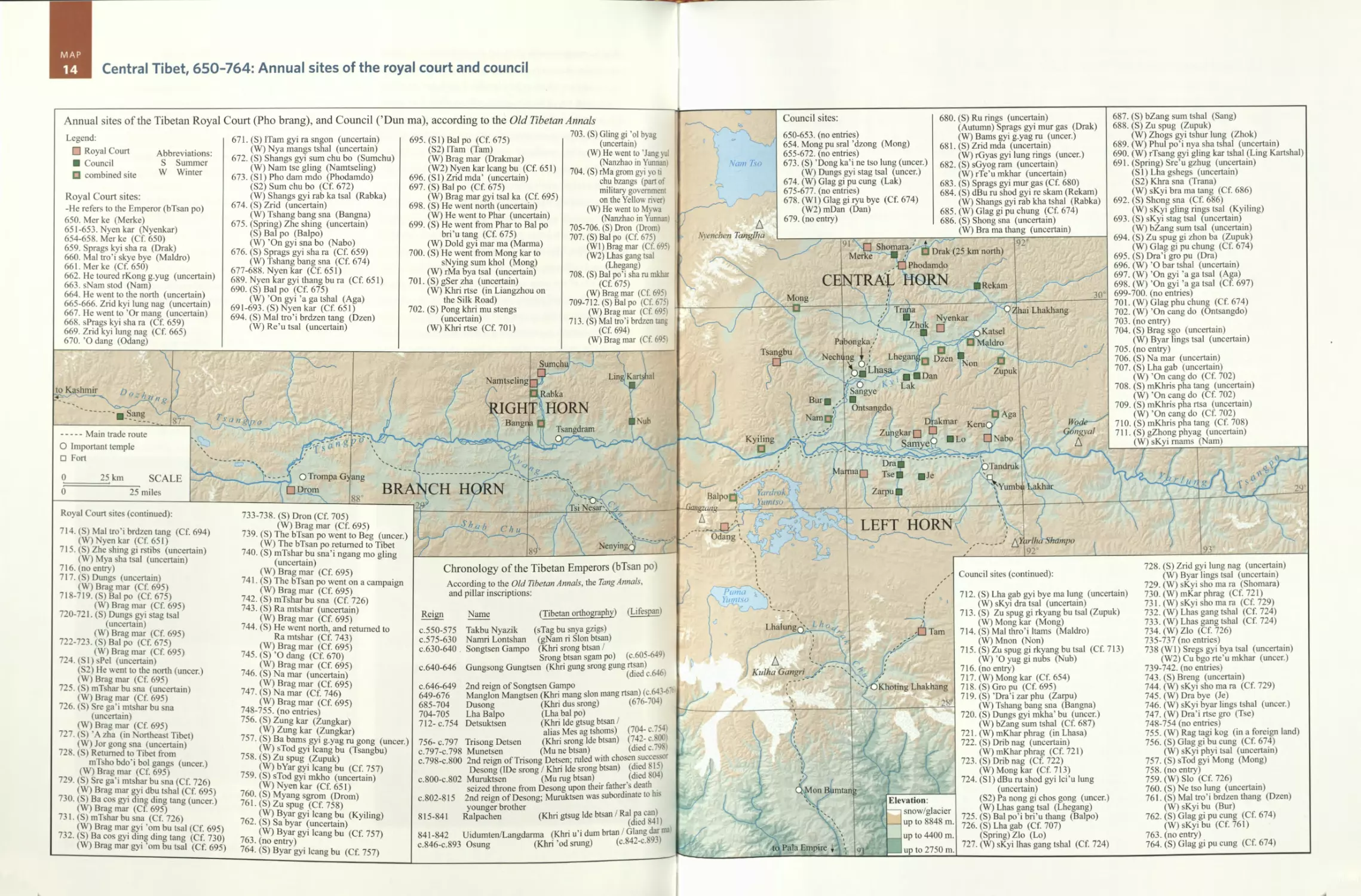

Map 14 Central Tibet 650-764: Annual sites of the royal court and

council 56

Annual sites of the Tibetan Royal Court {Pbo brang) and council

{'Dun ma)

Chronology of the Tibetan emperors {frTsan po)

PART 3

The Period of Disunion, circa 900-1642

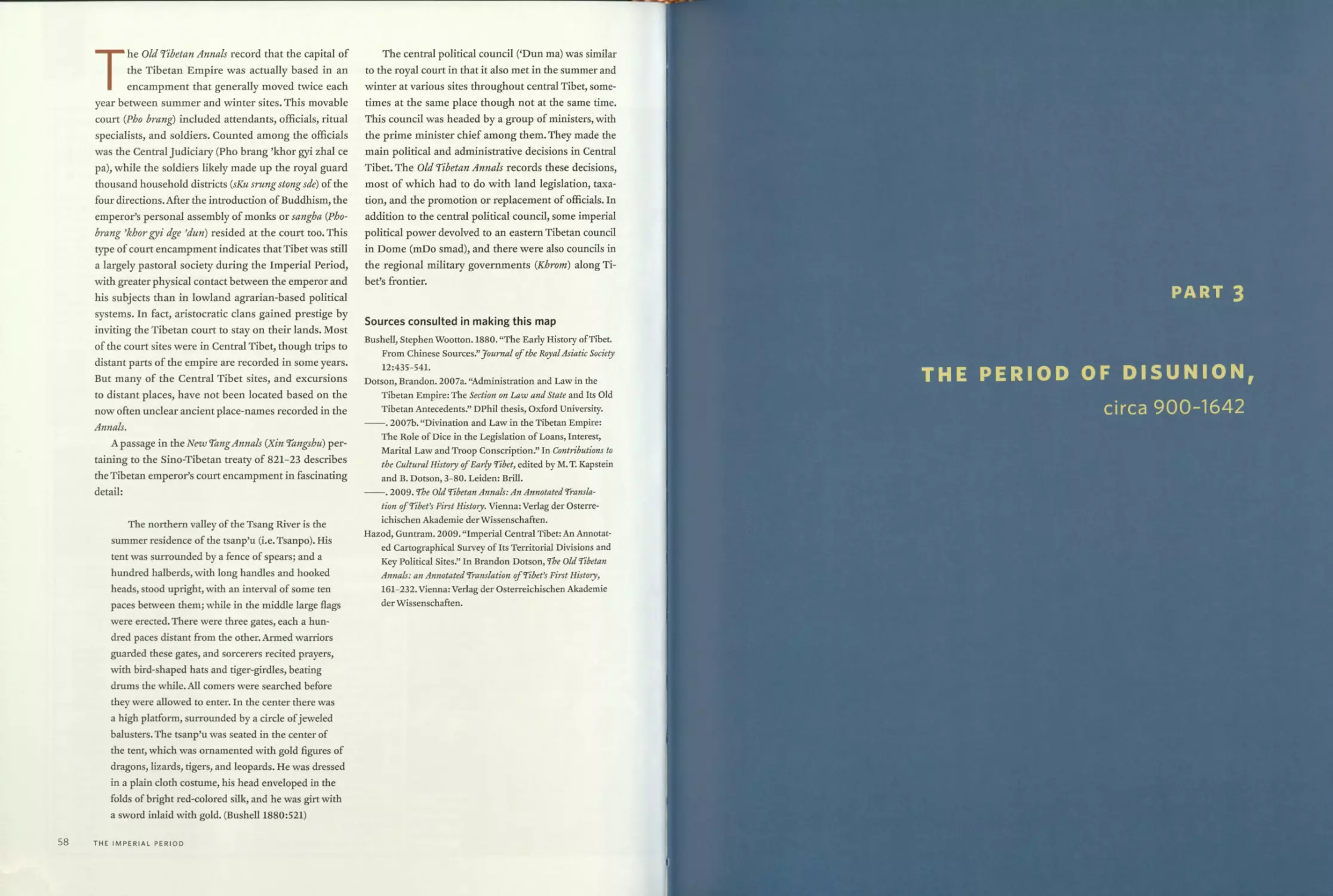

Map 15 Major polities and important religious sites during the

aftermath of empire and the Second Diffusion of Buddhism,

circa 842-1240 60

The Kagyu schools

viii

CONTENTS

Map 16 Central Tibet circa 900-1240: Aftermath of empire and religious

sites founded during the Second Diffusion of Buddhism 68

Lhasa Valley plan

Lhasa town plan

The regional principalities (rje dpon tsban)

Map 17 Ngari circa 900-1100: The kingdoms of Ngari Khorsum 72

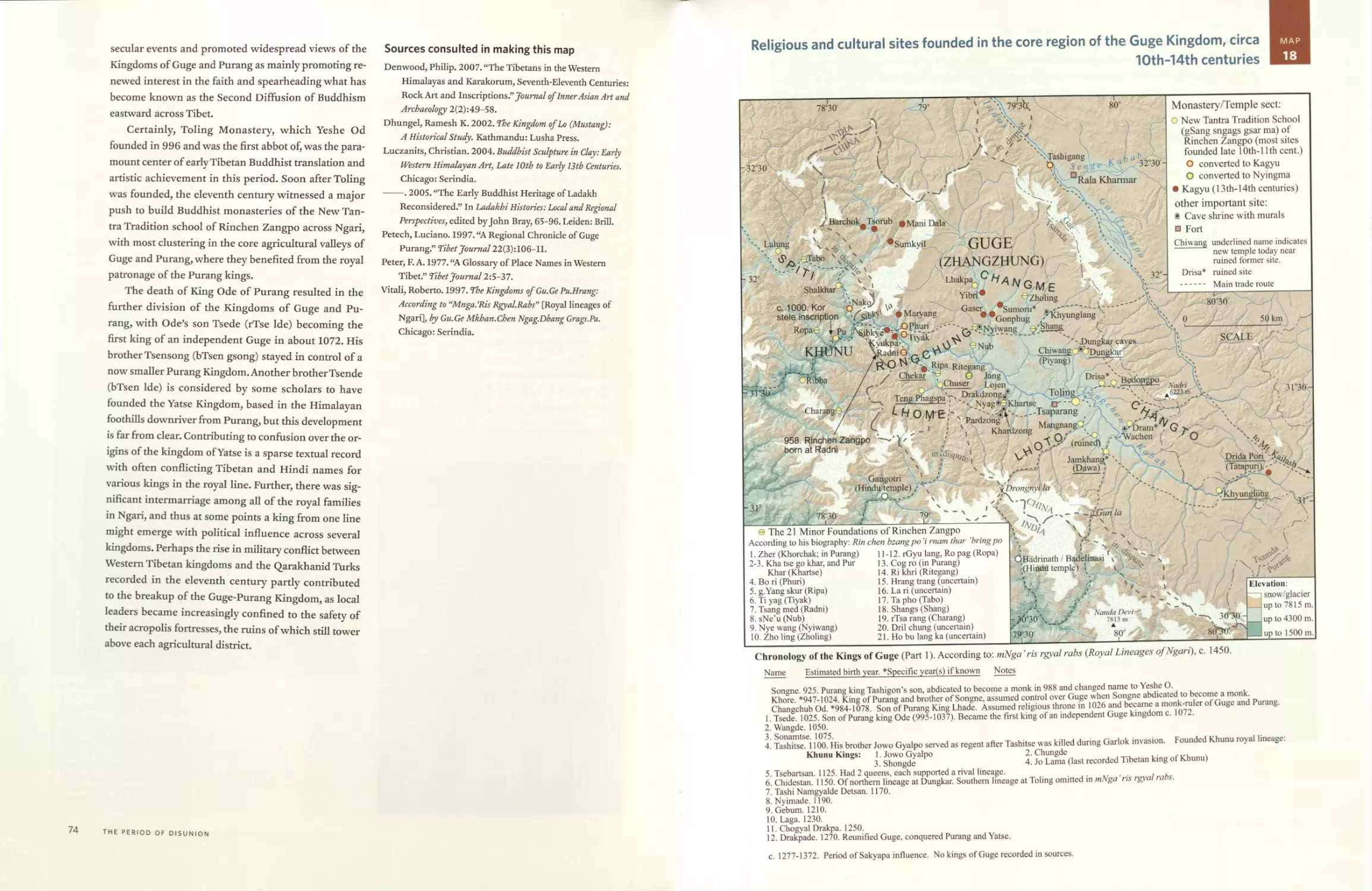

Map 18 Religious and cultural sites founded in the core region of the

Guge Kingdom, circa 10th-14th centuries 75

The twenty-one minor foundations of Rinchen Zangpo

Chronology of the kings of Guge, part 1

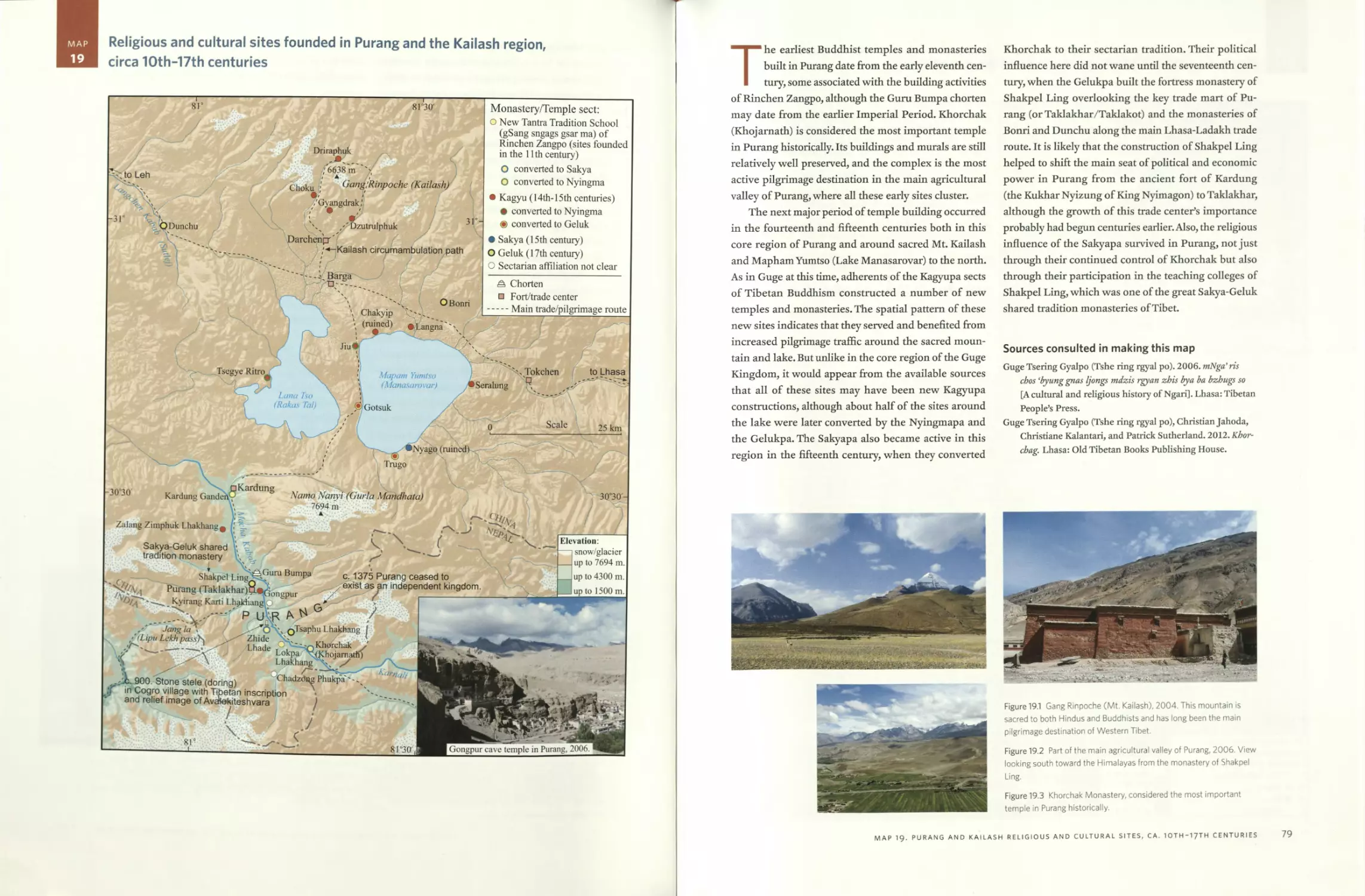

Map 19 Religious and cultural sites founded in Purang and the Kailash

region, circa 10th-17th centuries 78

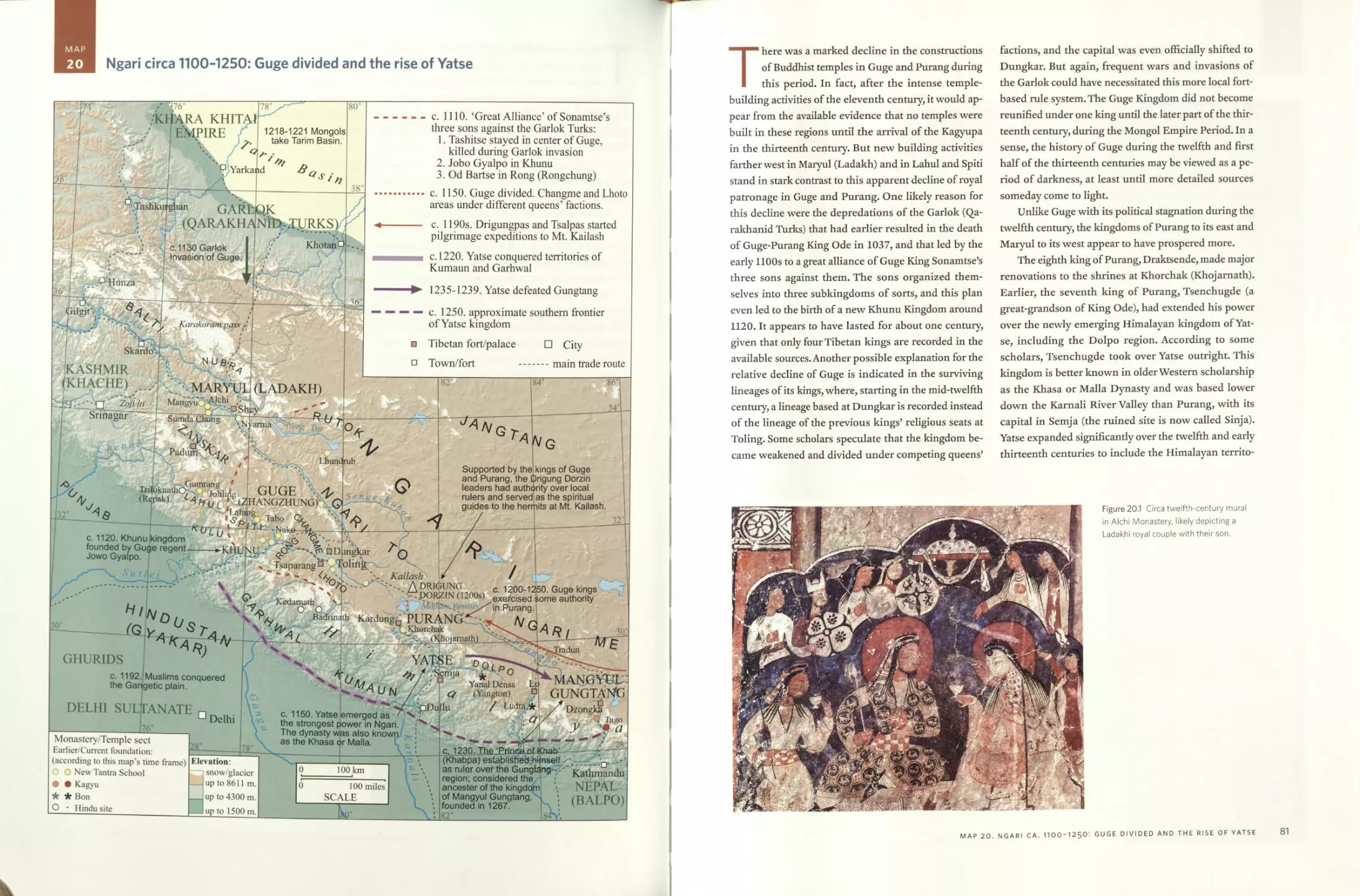

Map 20 Ngari circa 1100-1250: Guge divided and the rise of Yatse 80

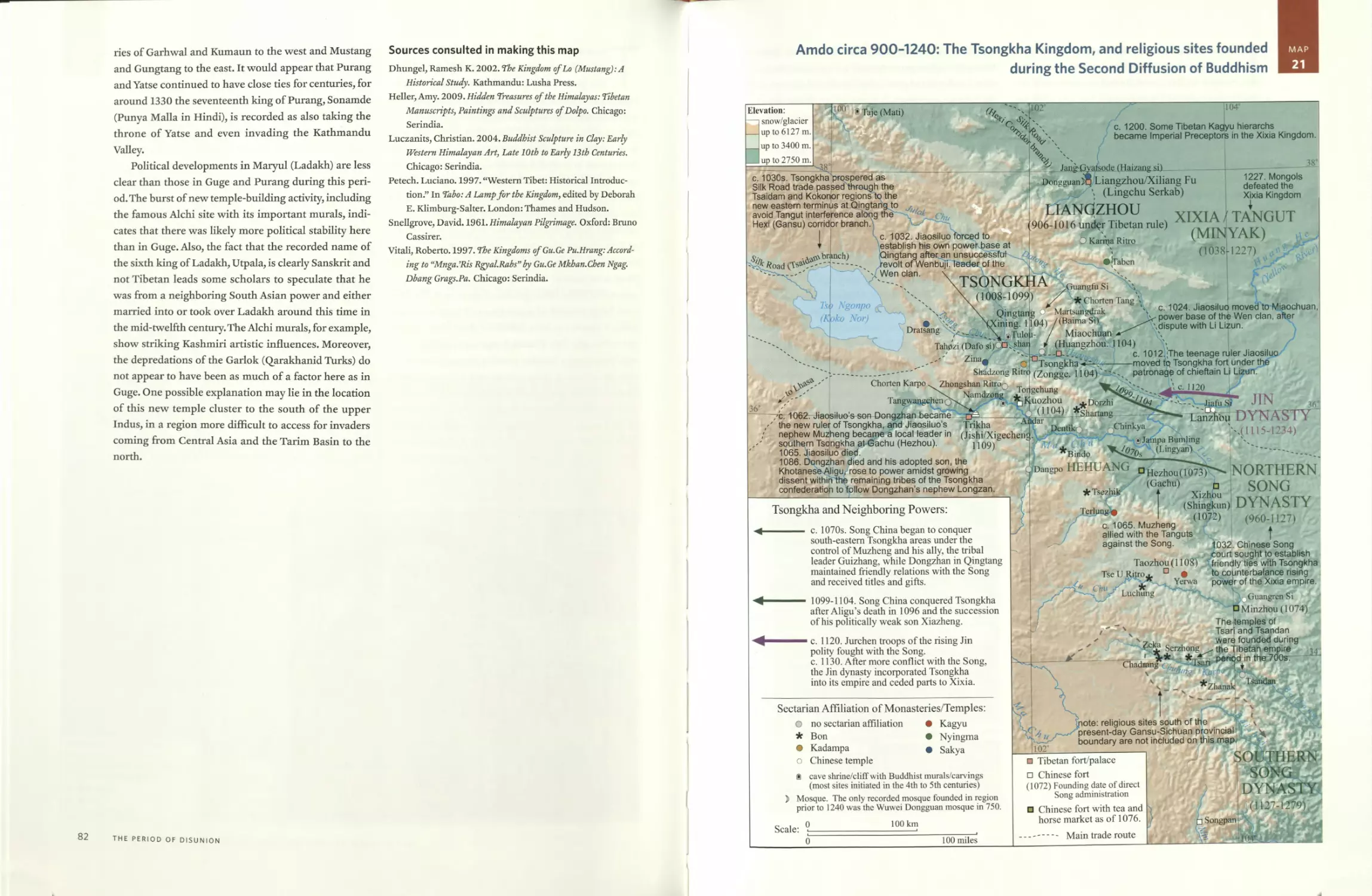

Map 21 Amdo circa 900-1240: The Tsongkha Kingdom, and religious sites

founded during the Second Diffusion of Buddhism 83

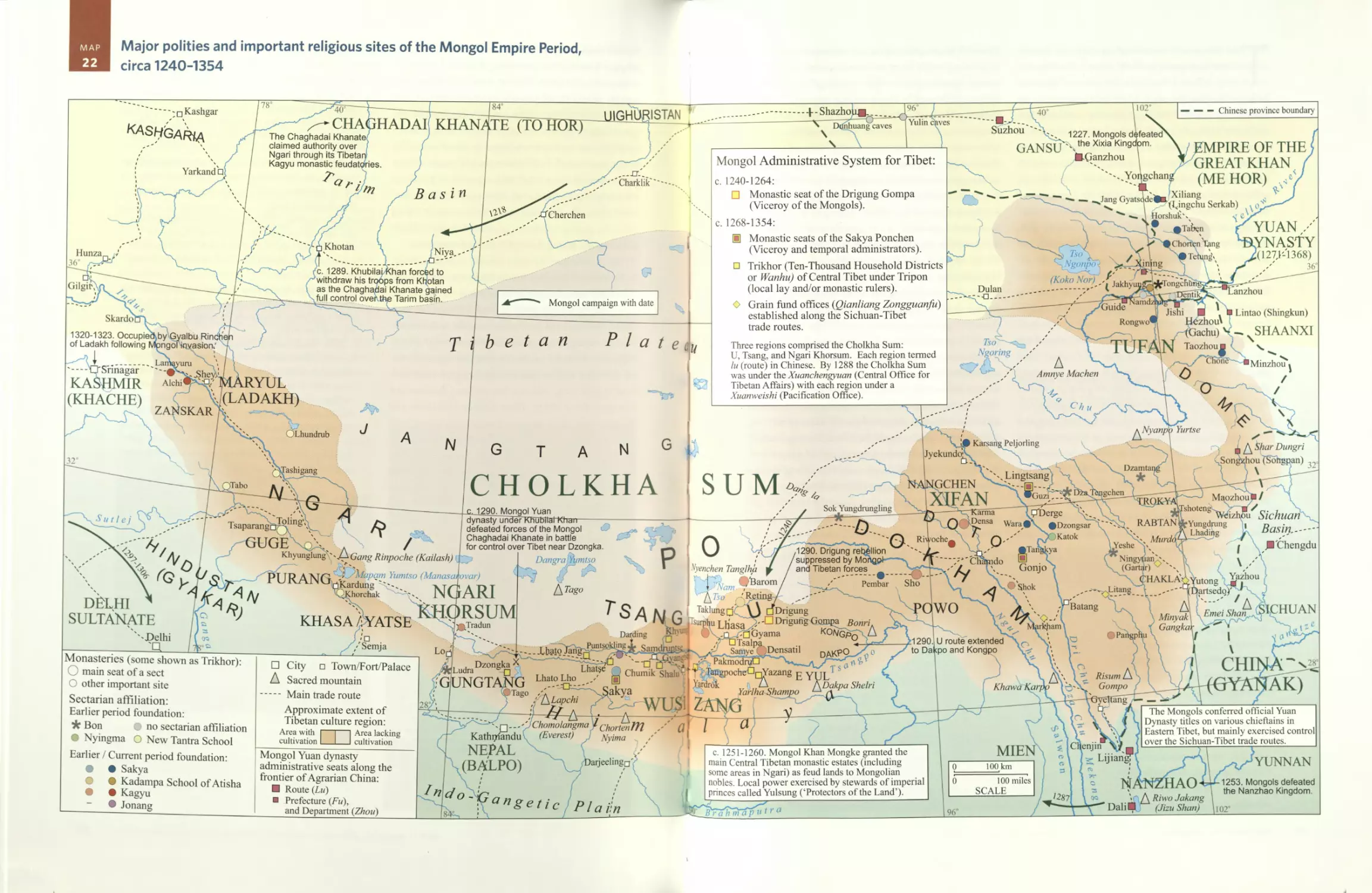

Map 22 Major polities and important religious sites of the Mongol Empire

Period, circa 1240-1354 86

Mongol administrative system for Tibet

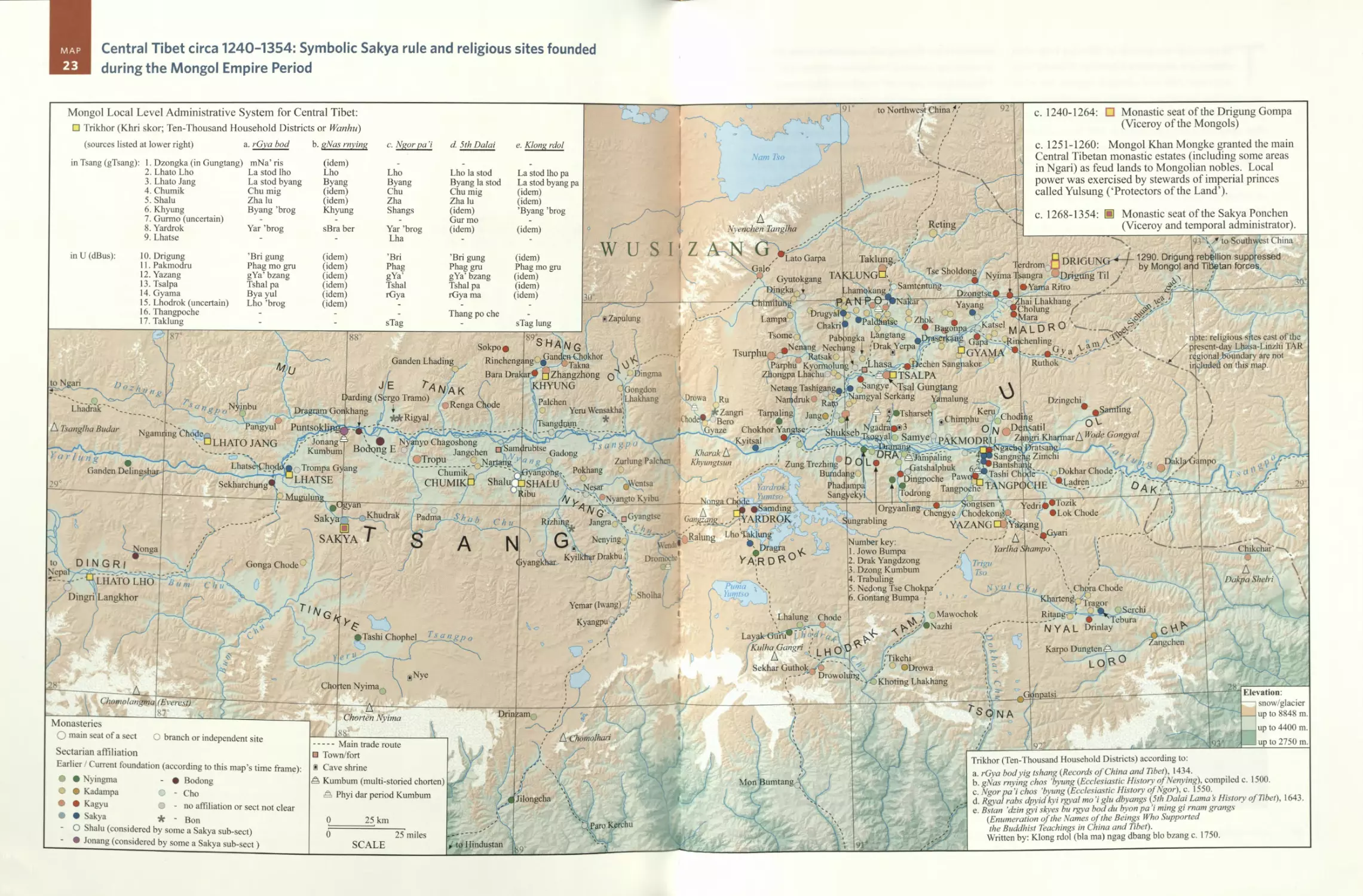

Map 23 Central Tibet circa 1240-1354: Symbolic Sakya rule and religious

sites founded during the Mongol Empire Period 92

The ten thousand household districts (Kbri skor / Wanhu)

Map 24 Ngari circa 1250-1365: Yatse-Gungtang rivalry during the Mongol

Empire Period 96

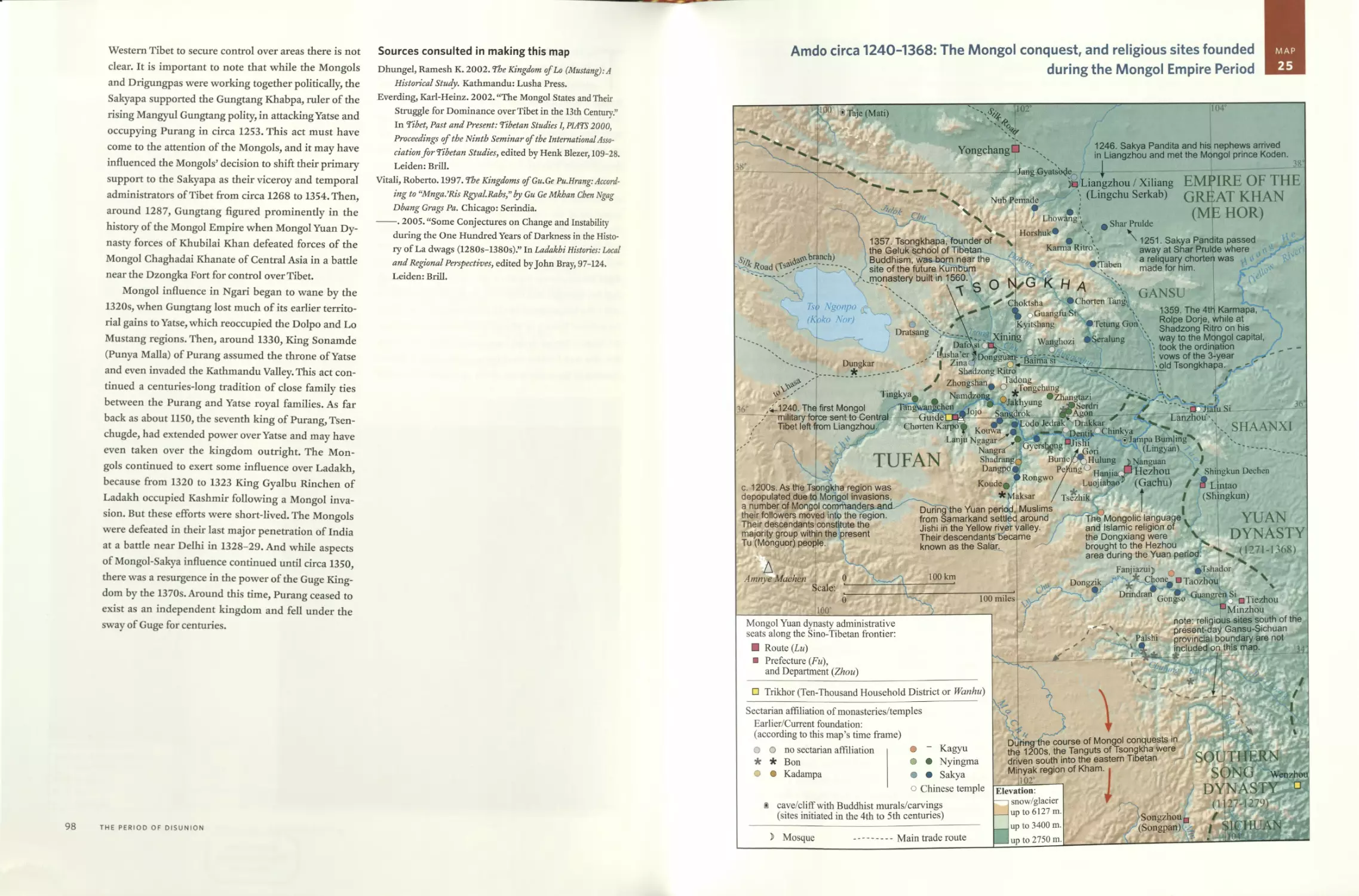

Map 25 Amdo circa 1240-1368: The Mongol conquest, and religious sites

founded during the Mongol Empire Period 99

Map 26 Important Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist monasteries founded during

the 12th to 16th centuries 102

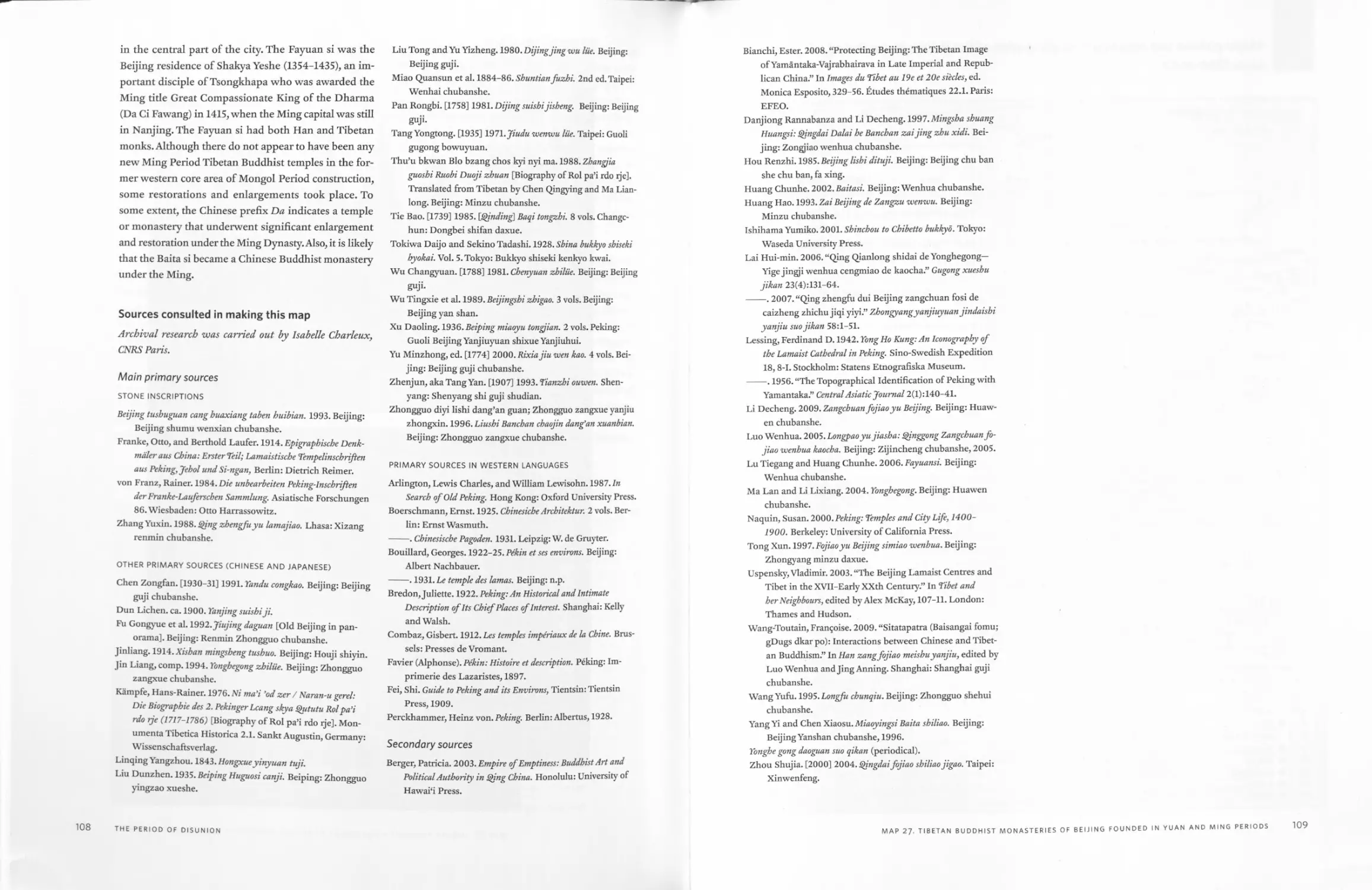

Map 27 Important Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of Beijing

founded during the Yuan and Ming Periods, circa 13th-16th

centuries 105

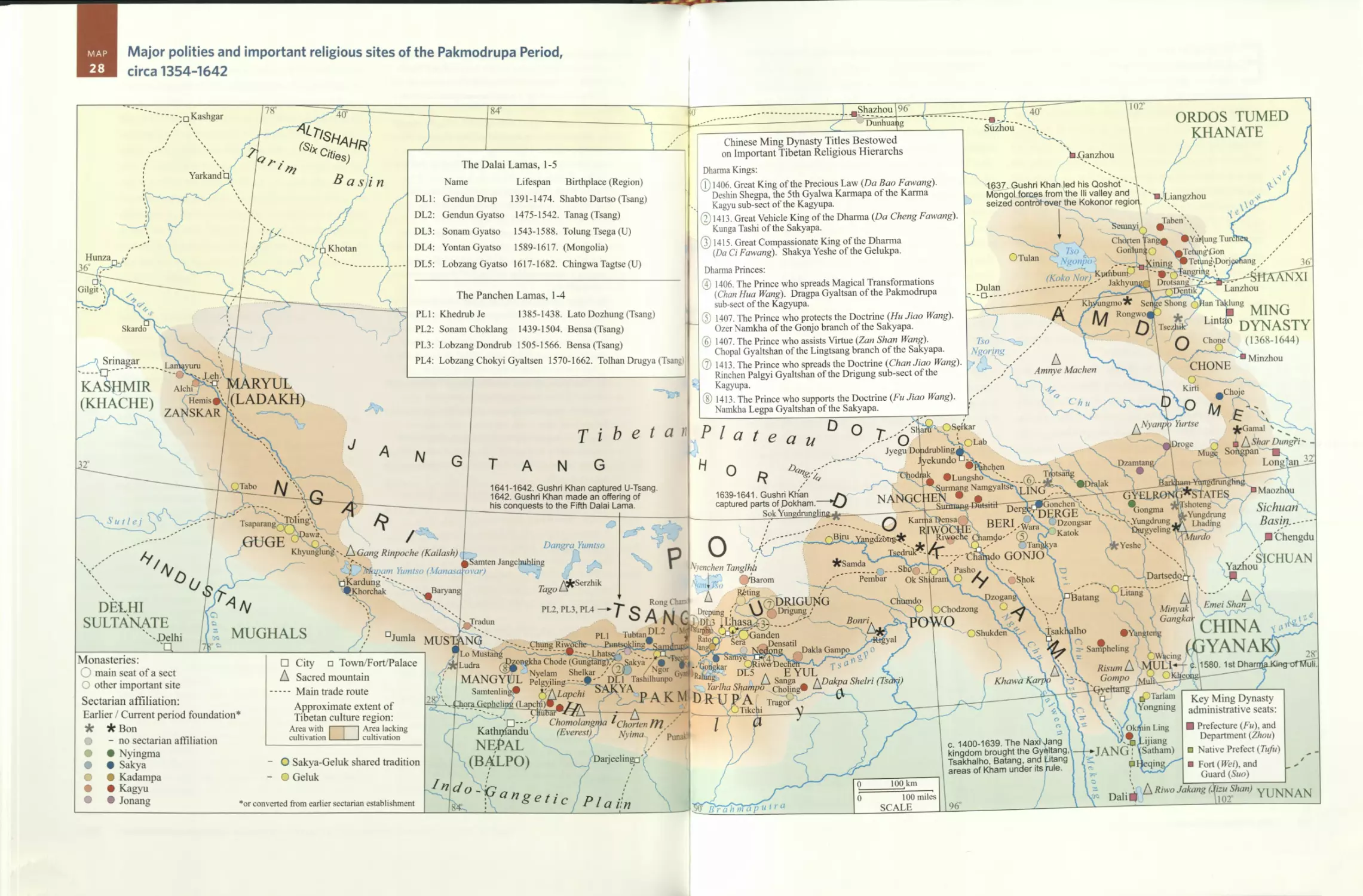

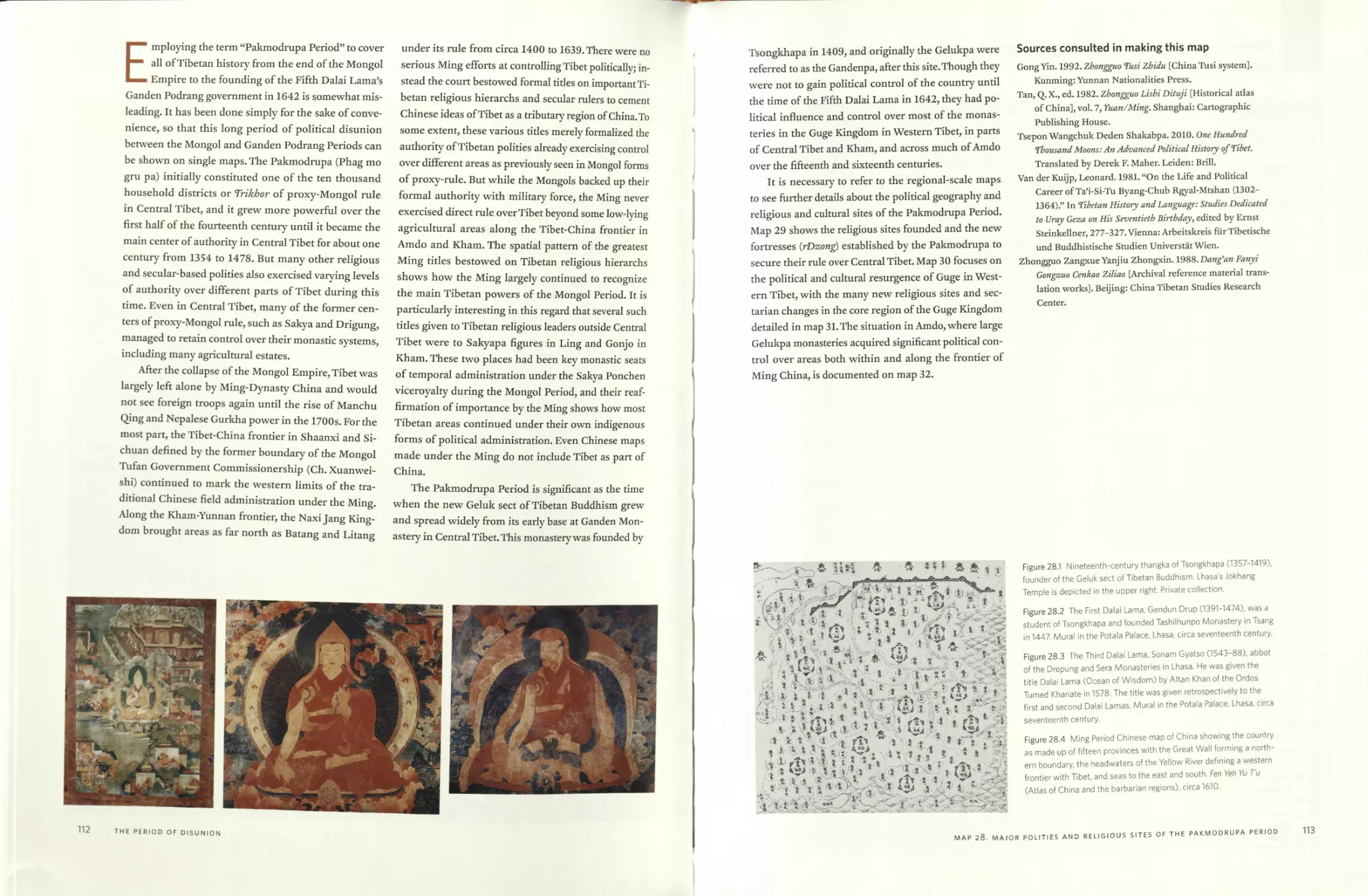

Map 28 Major polities and important religious sites of the Pakmodrupa

Period, circa 1354-1642 110

Chinese Ming Dynasty tides bestowed on important Tibetan

religious hierarchs

Birthplaces of the First through Fifth Dalai Lamas

Birthplaces of the First through Fourth Panchen Lamas

CONTENTS

ix

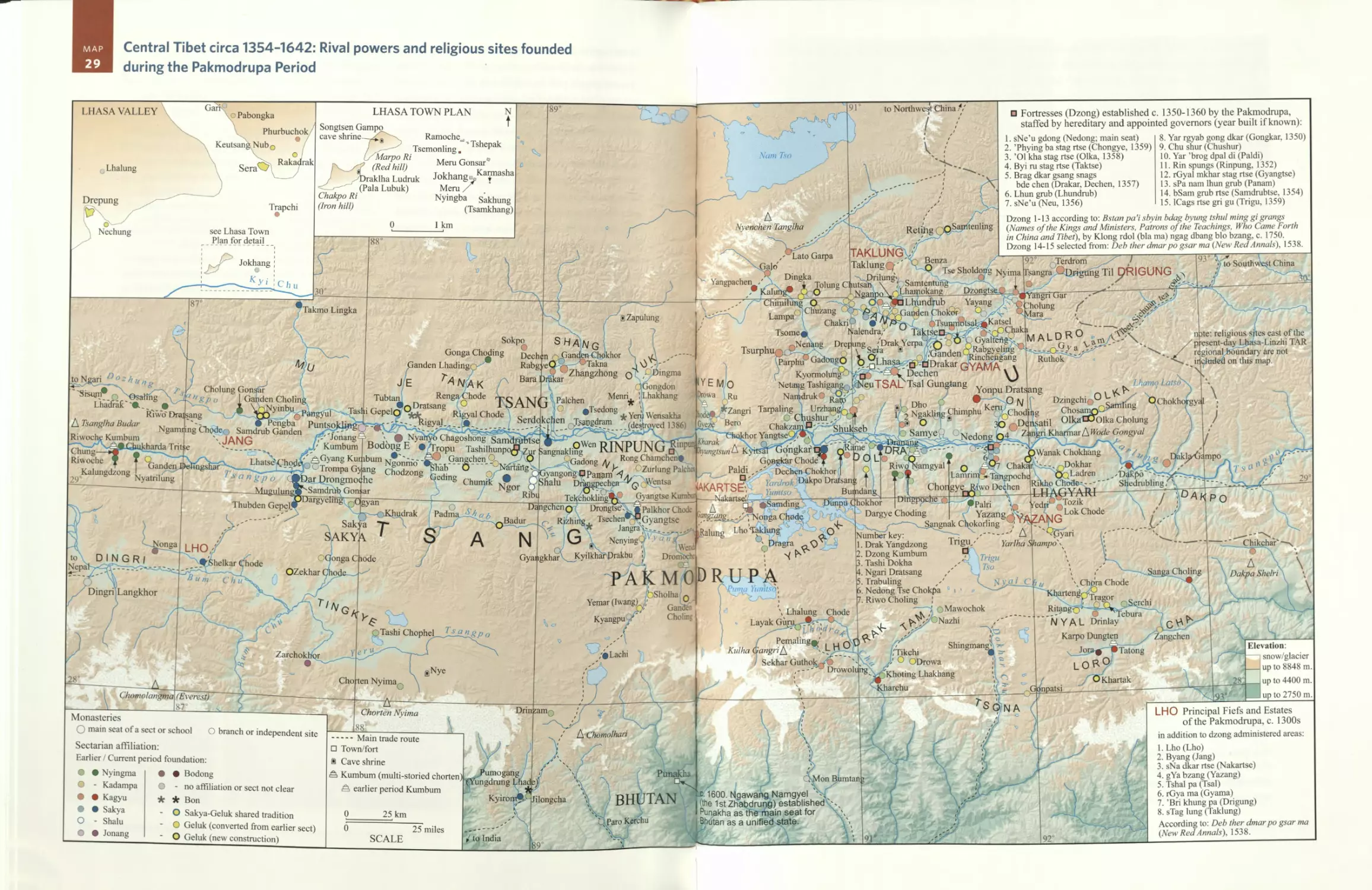

Map 29 Central Tibet circa 1354-1642: Rival powers and religious sites

founded during the Pakmodrupa Period 114

Lhasa Valley plan

Lhasa town plan

Fortresses (rDzong) established circa 1350-60 by the Pakmodrupa

Principal fiefs and estates of the Pakmodrupa, circa 1300s

Map 30 Ngari circa 1365-1630: The resurgence of Guge 118

Map 31 Religious and cultural sites in the core region of the Guge

Kingdom, circa 15th-17th centuries 119

Tsaparang Fort plan

Toling Monastery plan

Chronology of the kings of Guge, part 2

Map 32 Amdo circa 1368-1644: Local monastic powers in relation to

China’s Ming Dynasty 123

PART 4

The Ganden Podrang Period (Kingdom of the Dalai Lamas)

Map 33 Major polities of the Ganden Podrang Period,

circa 1642-1900 128

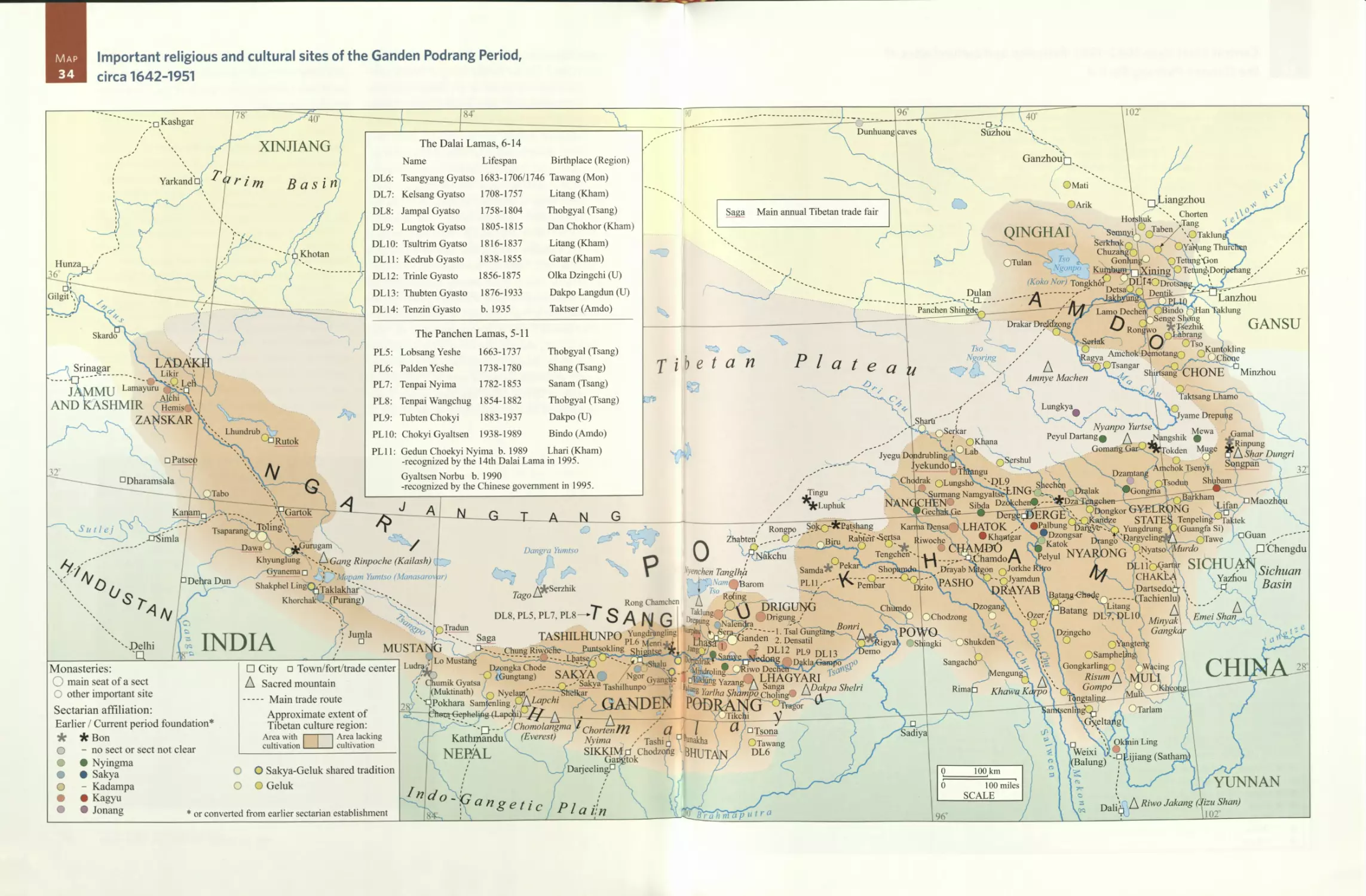

Map 34 Important religious and cultural sites of the Ganden Podrang

Period, circa 1642-1951 132

Main annual Tibetan trade fairs

Birthplaces of the Sixth through Fourteenth Dalai Lamas

Birthplaces of the Fifth through Eleventh Panchen Lamas

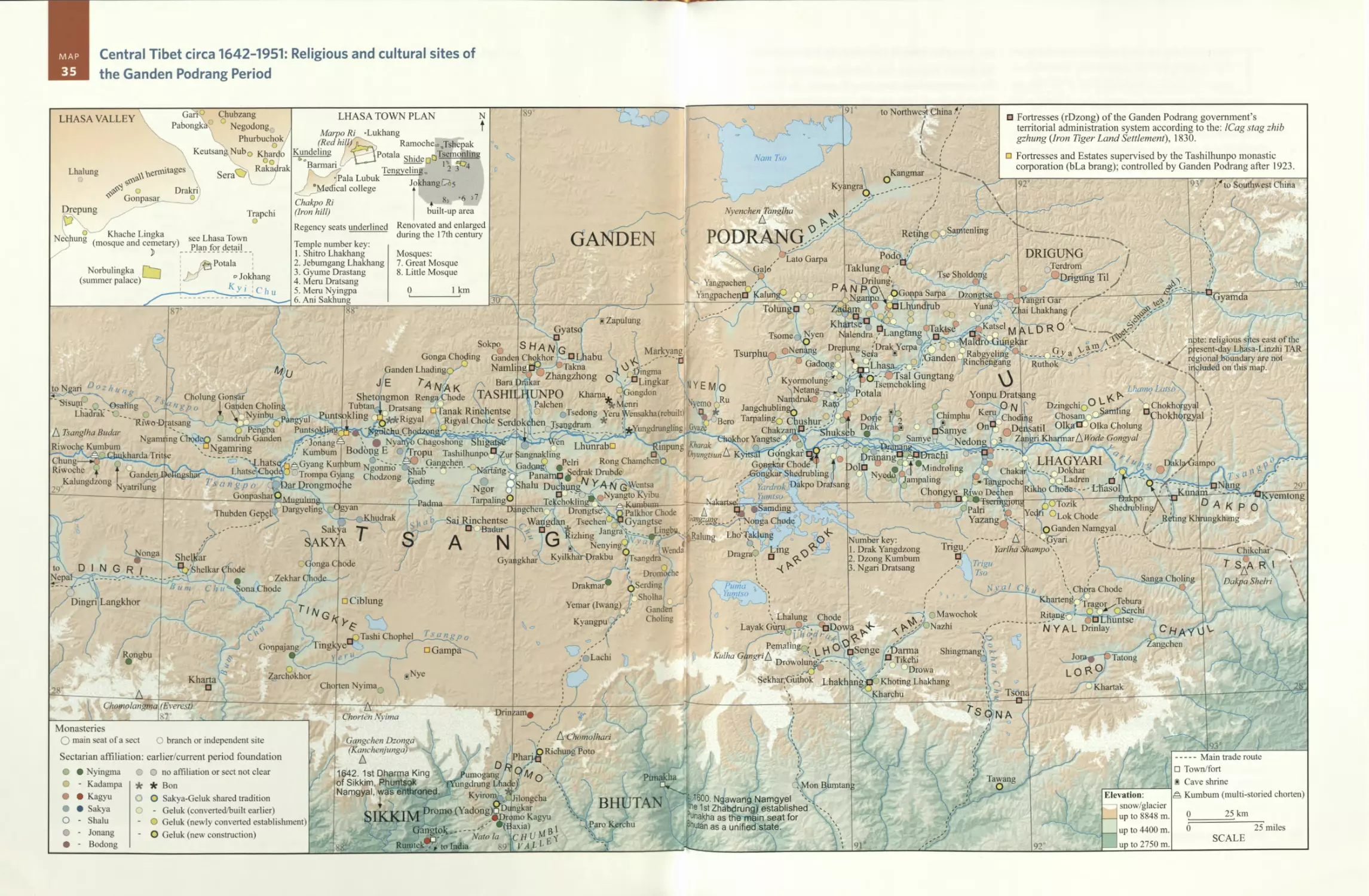

Map 35 Central Tibet circa 1642-1951: Religious and cultural sites of

the Ganden Podrang Period 134

Lhasa Valley plan

Lhasa town plan

Fortresses (rDzong) of the Ganden Podrang government’s territorial

administration system circa 1830

Fortresses and estates supervised by the Tashi Lhunpo Monastic

Corporation (bLa brang) until 1923

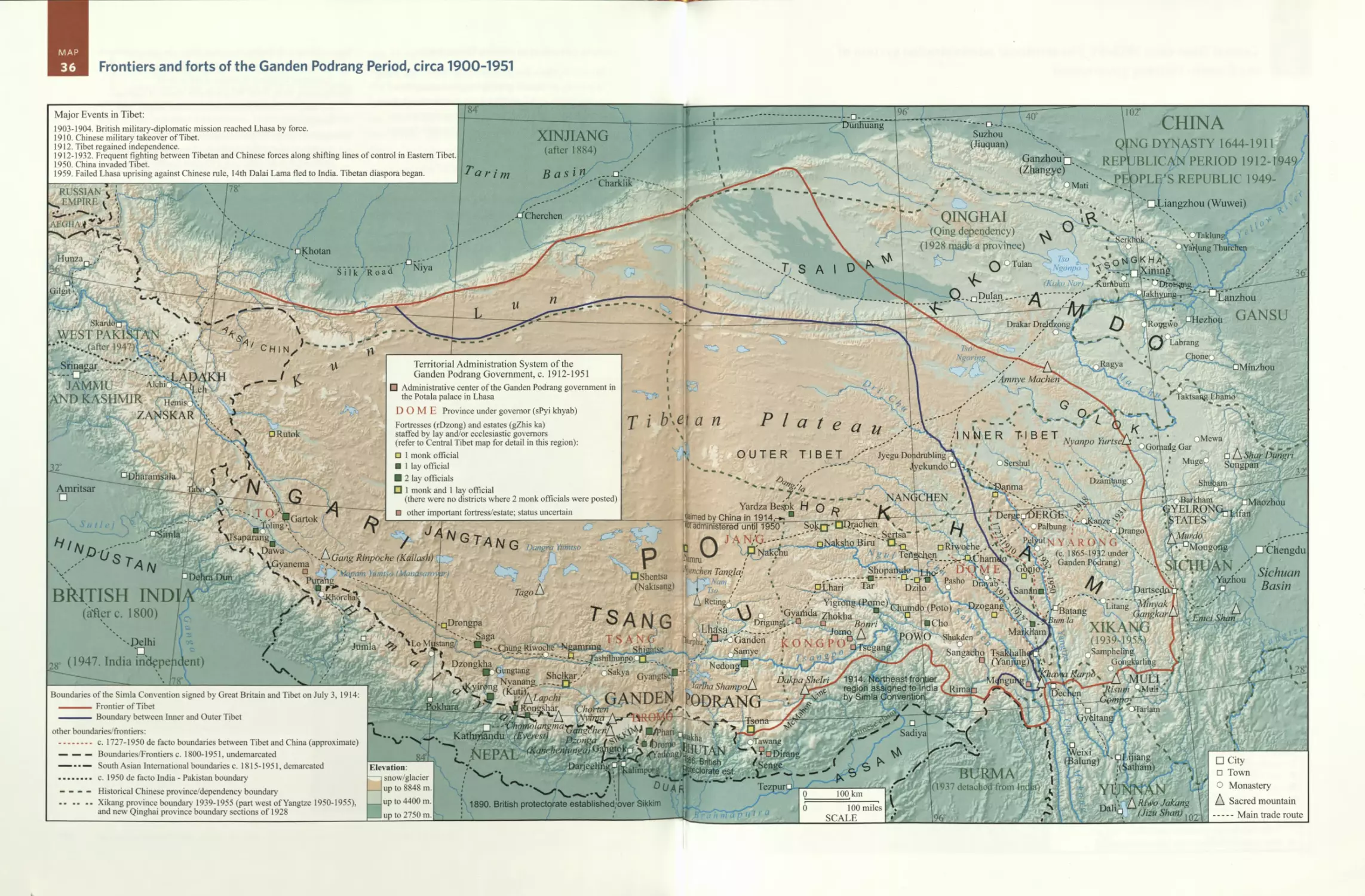

Map 36 Frontiers and forts of the Ganden Podrang Period,

circa 1900-1951 138

Fortresses (rDzong) and estates (gZhis ka) staffed by lay or

ecclesiastic governors

Boundaries of the Simla Convention signed by Great Britain and

Tibet in 1914

x

CONTENTS

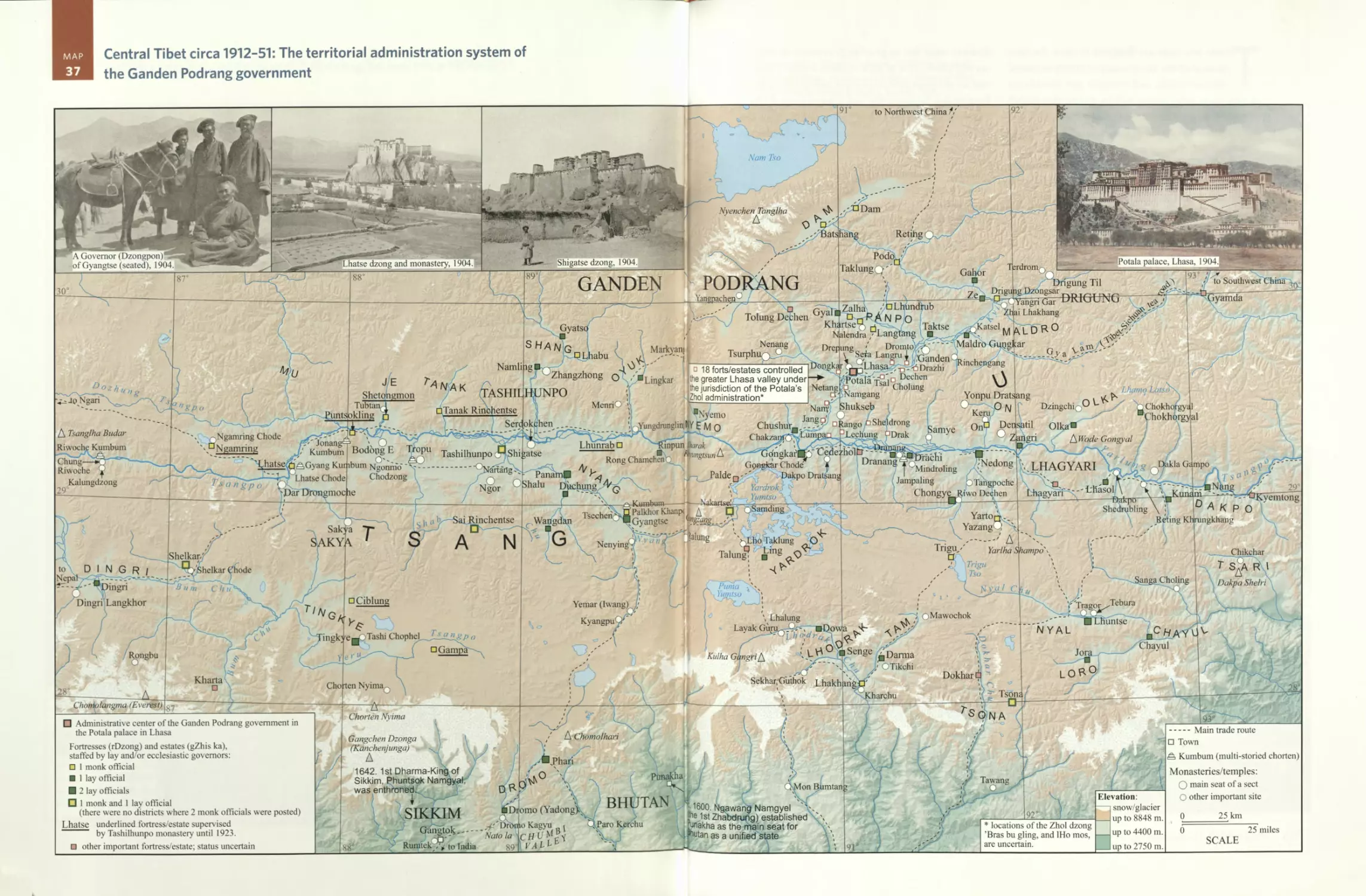

Map 37 Central Tibet circa 1912-1951: The territorial administration

system of the Ganden Podrang government 140

Fortresses (rDzong) and estates (gZhis ka) staffed by lay or

ecclesiastic governors

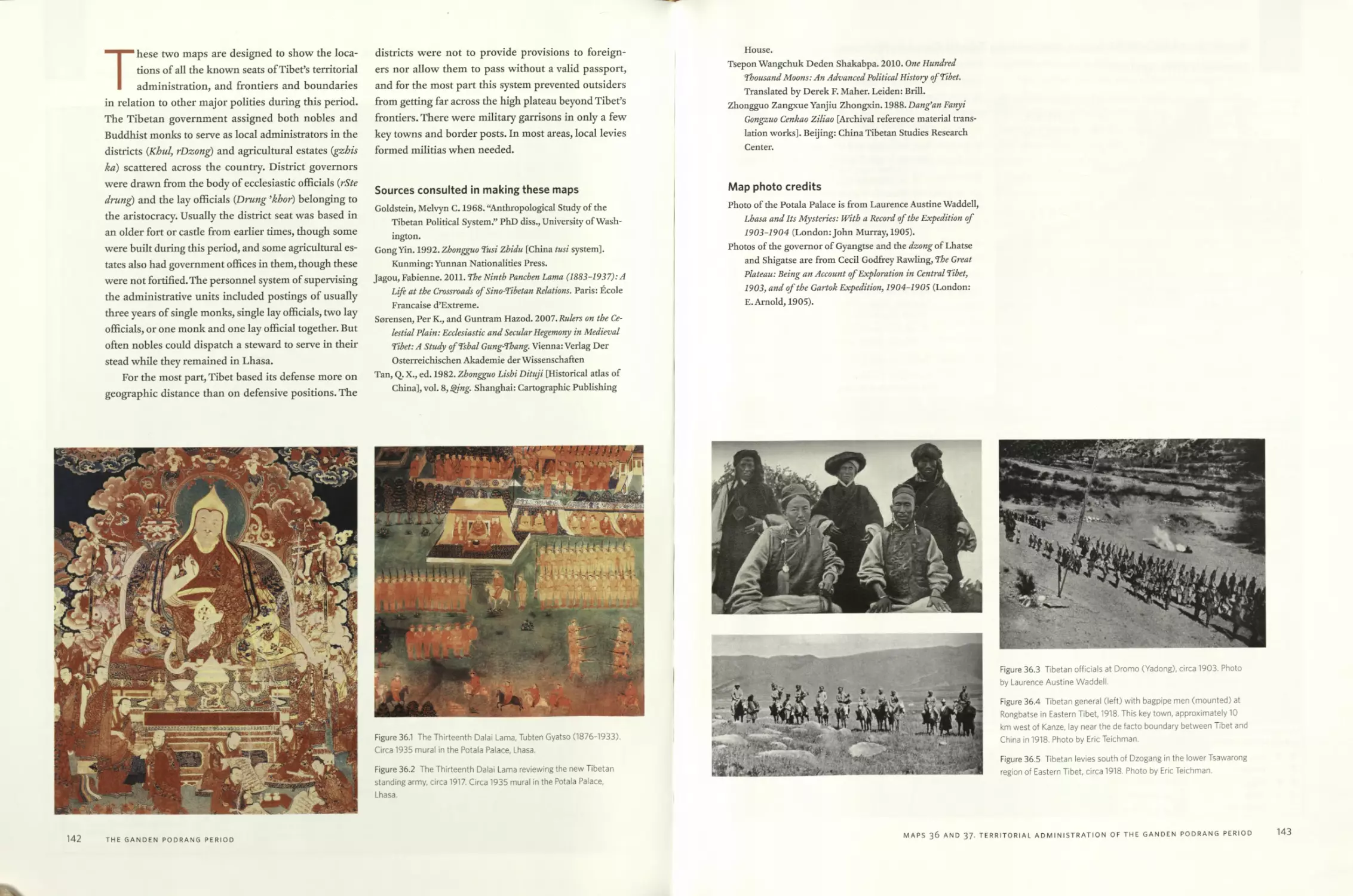

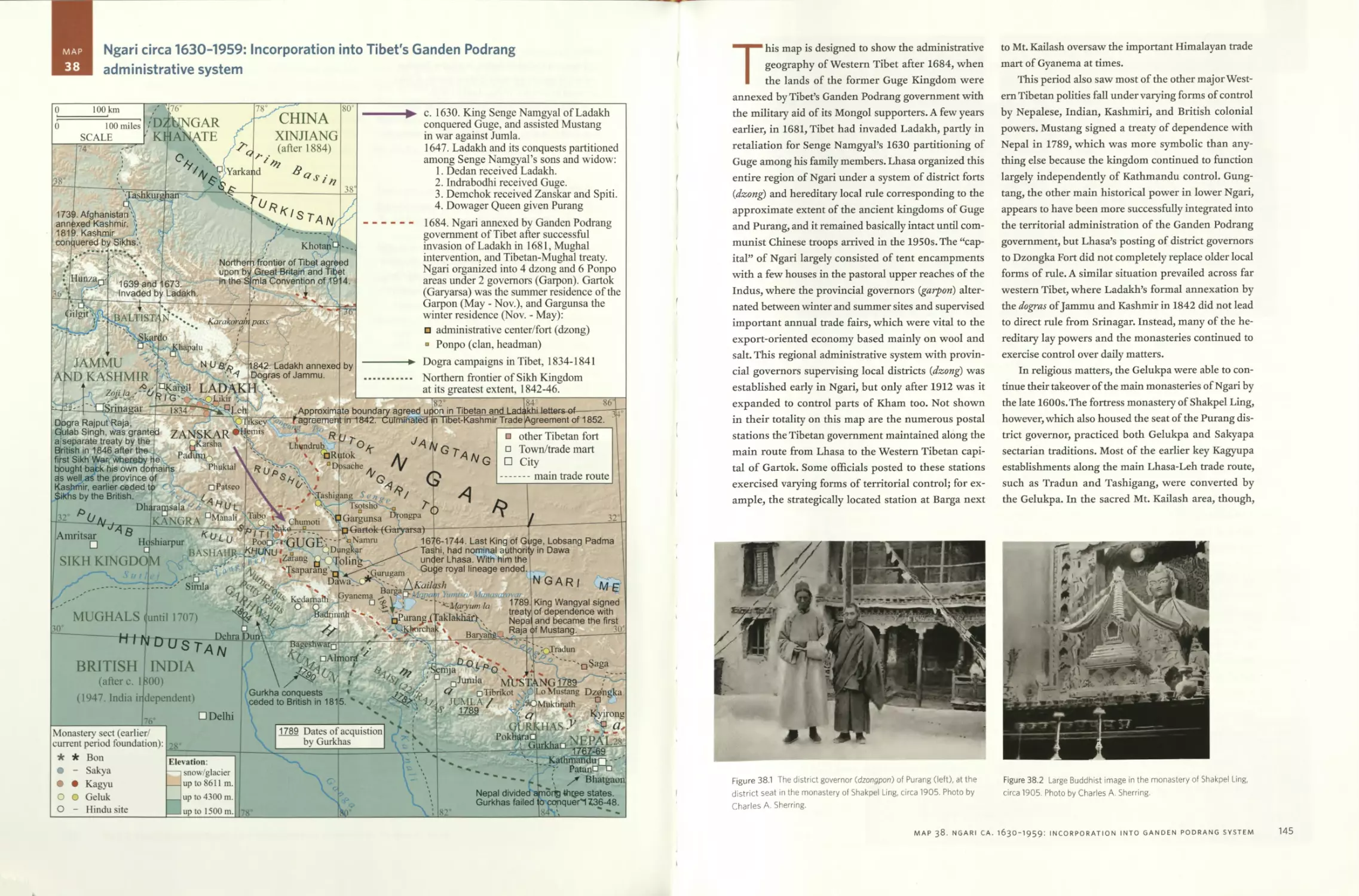

Map 38 Ngari circa 1630-1959: Incorporation into Tibet’s Ganden

Podrang administrative system 144

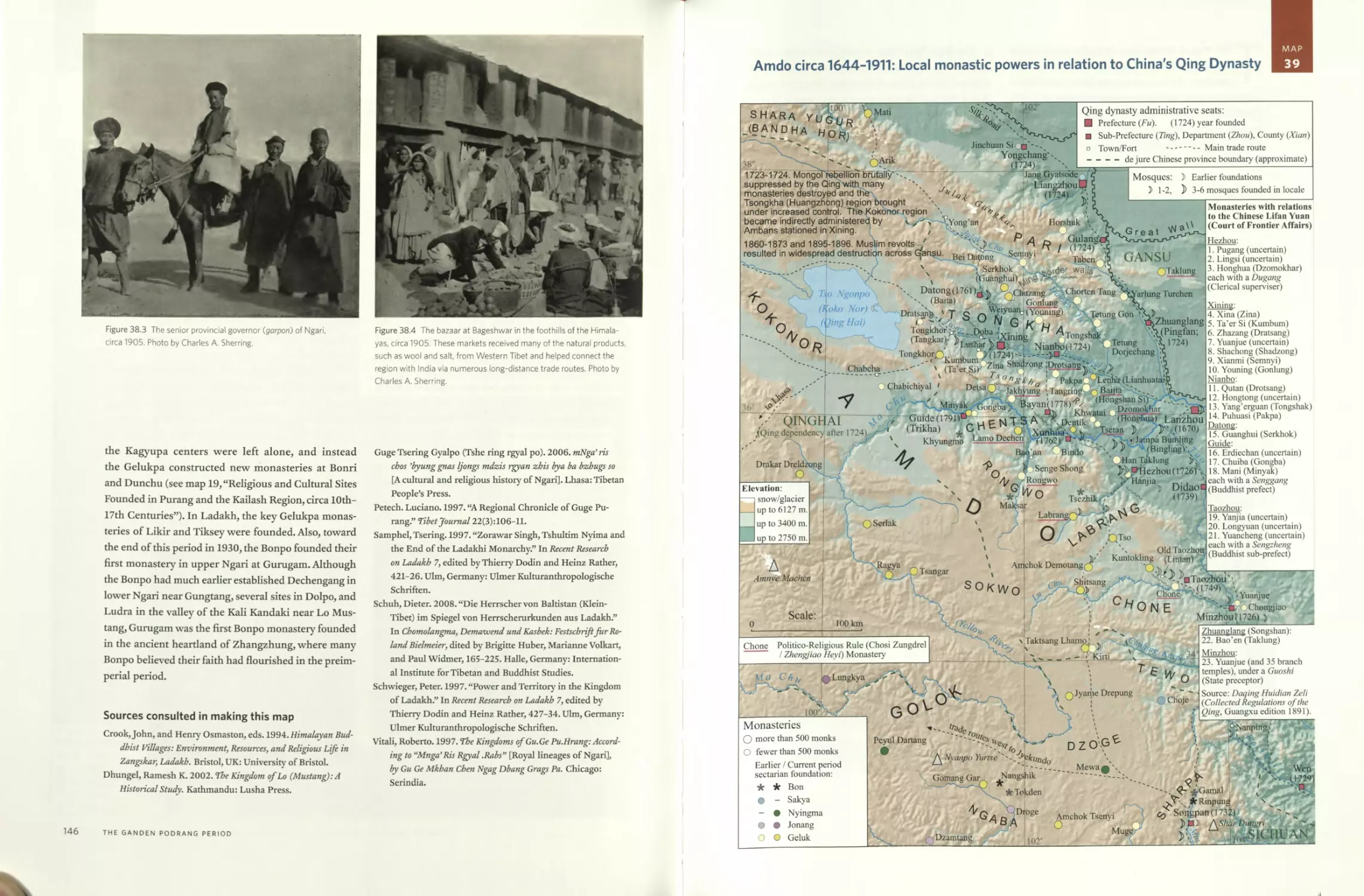

Map 39 Amdo circa 1644-1911: Local monastic powers in relation to

China’s Qing Dynasty 147

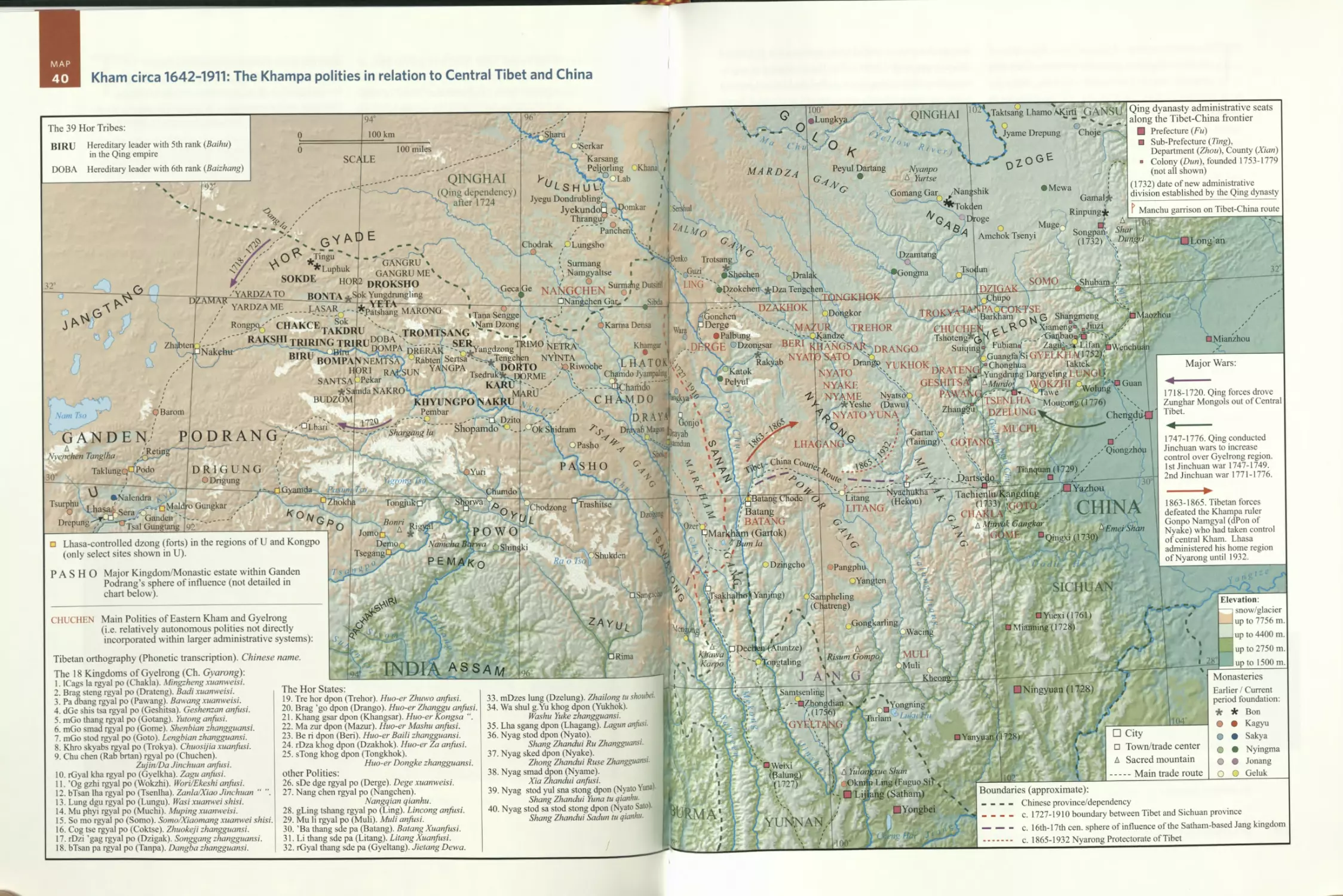

Map 40 Kham circa 1642-1911: The Khampa polities in relation to

Central Tibet and China 150

Main polities of Eastern Kham and Gyelrong

The Thirty-Nine Hor Tribes

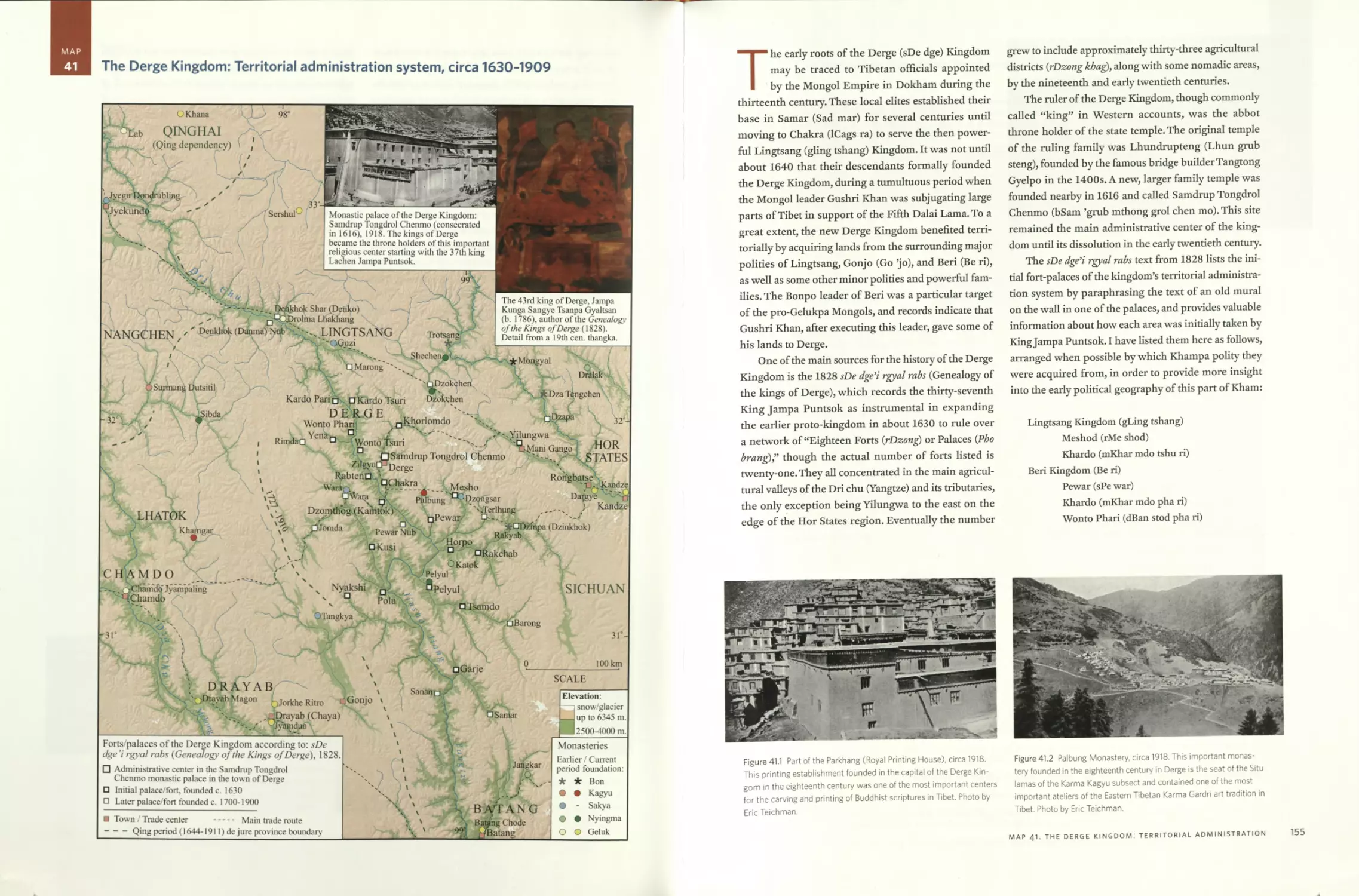

Map 41 The Derge Kingdom: Territorial administration system,

circa 1630-1909 154

Forts and palaces of the Derge Kingdom

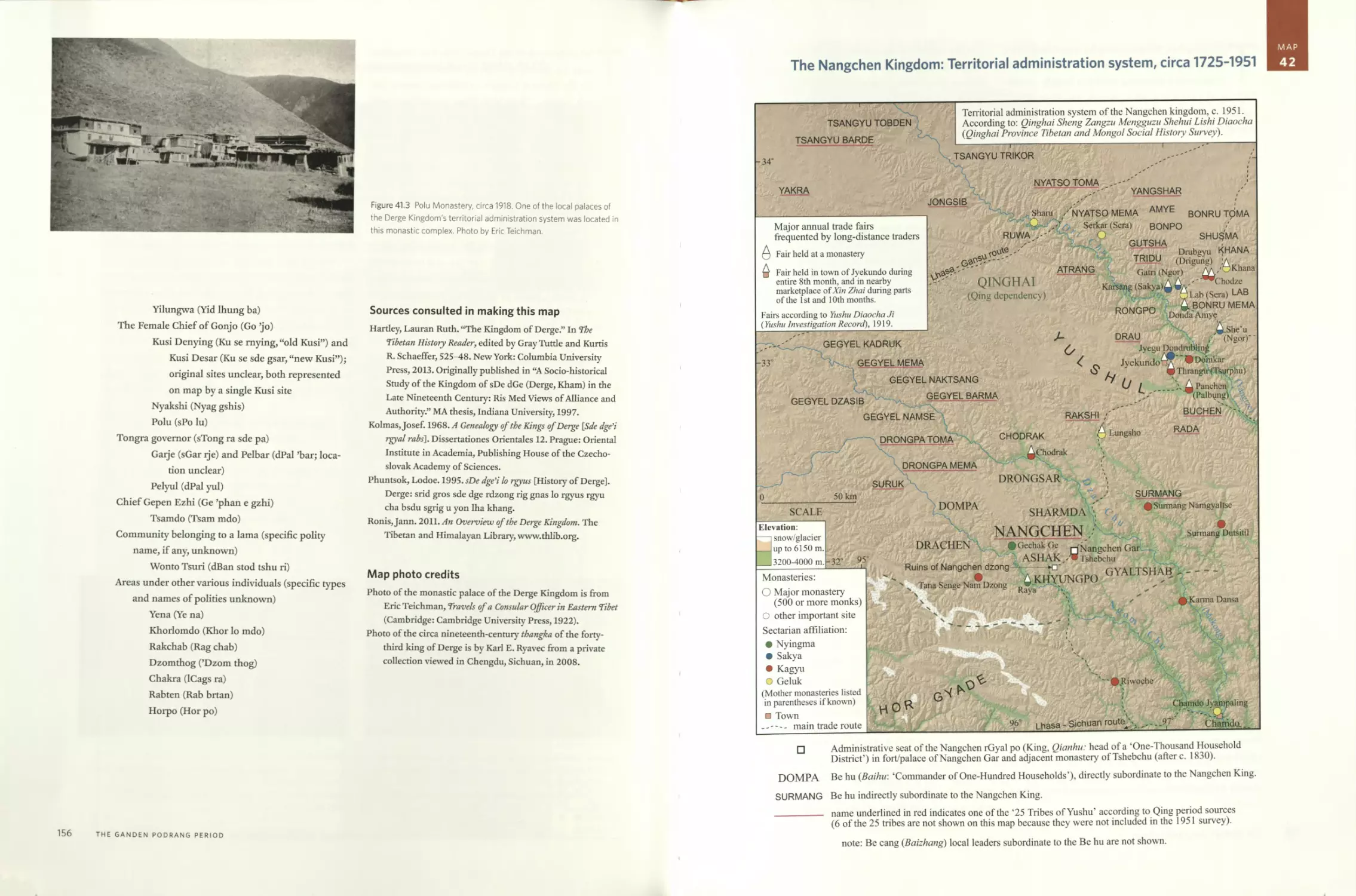

Map 42 The Nangchen Kingdom: Territorial administration system,

circa 1725-1951 157

The one hundred household districts (Be hu / Baihu)

The twenty-five tribes of Yushu

Major annual trade fairs frequented by long-distance traders

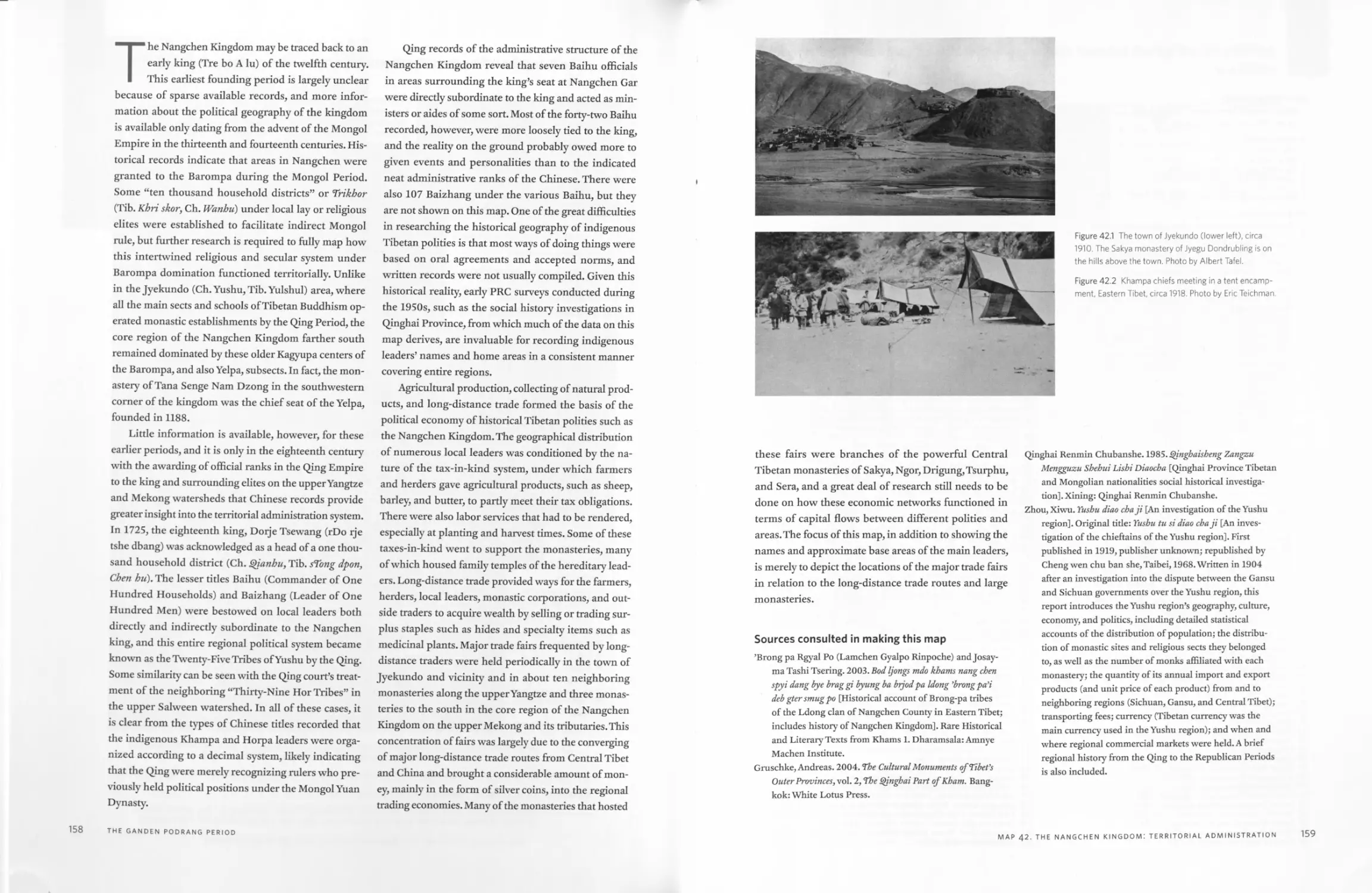

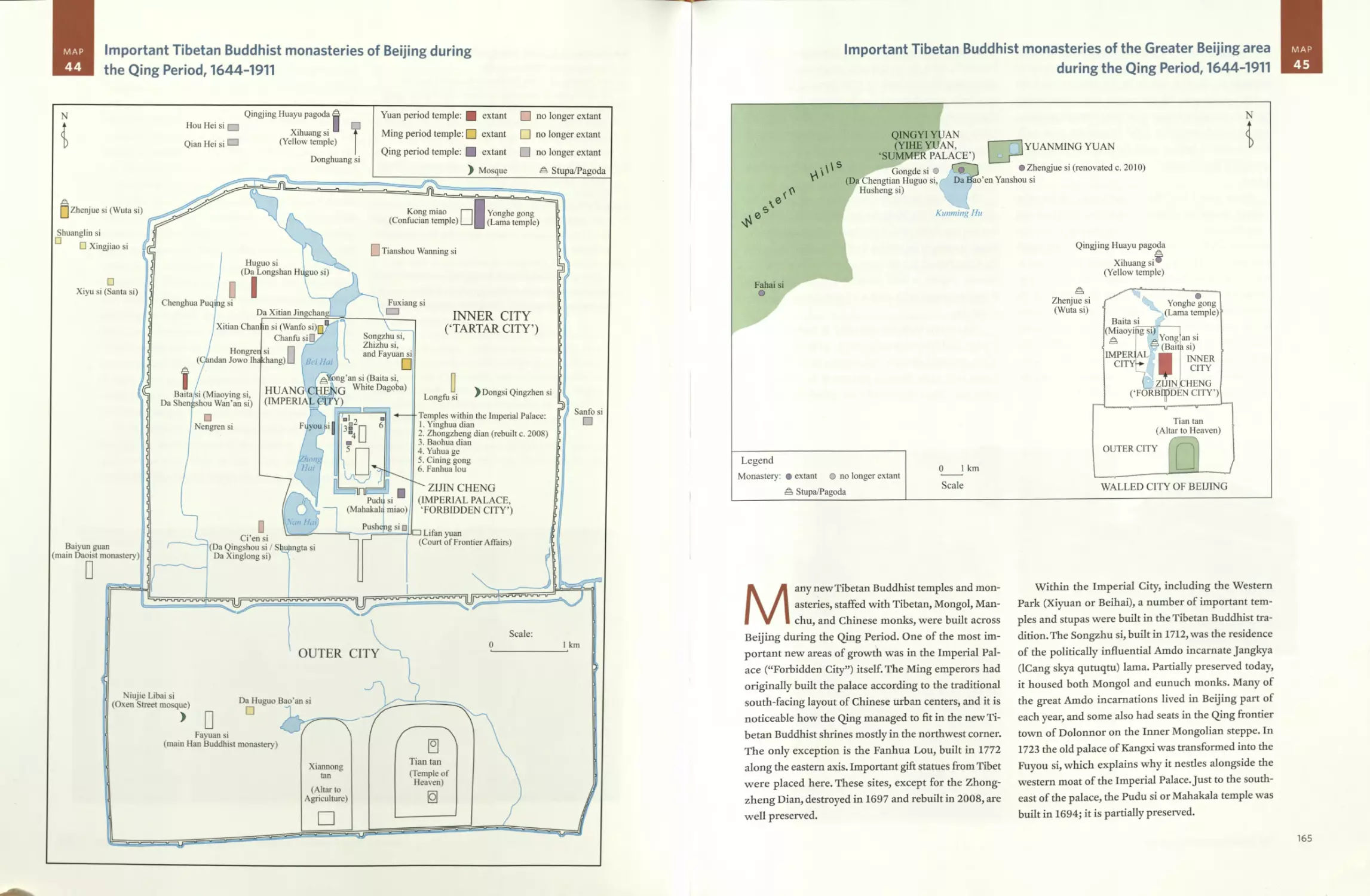

Map 43 Important Tibeto-Mongol Buddhist monasteries founded during

the Qing Period, 1644-1911 161

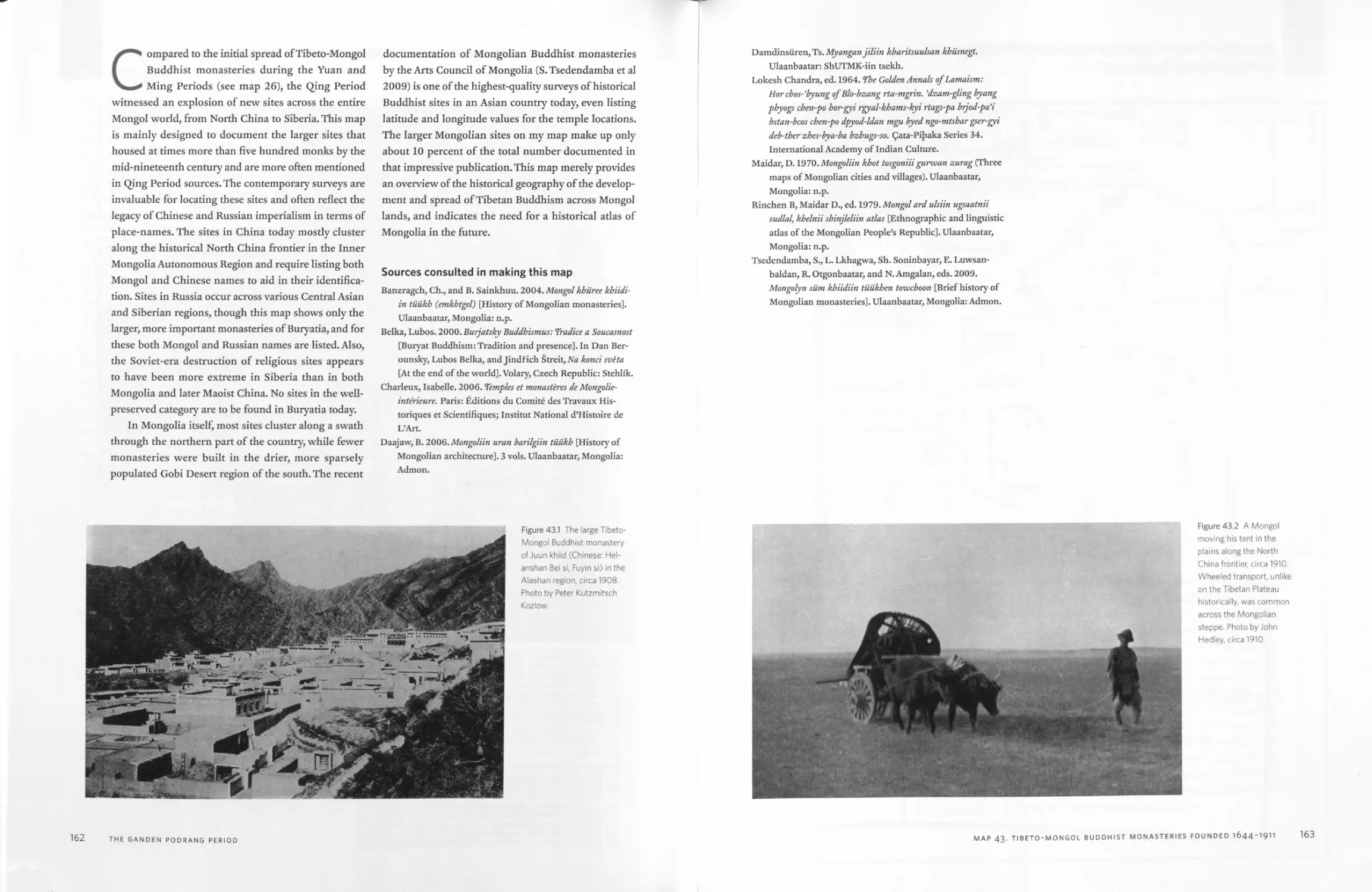

Map 44 Important Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of Beijing during the

Qing Period, 1644-1911 164

Map 45 Important Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of the Greater Beijing

area during the Qing Period, 1644-1911 165

CONCLUSION

Map 46 Natural resources of the Tibetan Plateau 170

Map 47 Main land cover patterns of the Tibetan Plateau, circa 2000 174

Map 48 The Tibetan population, circa 2000 178

Map 49 Tibet in the People’s Republic of China, circa 2000:

The territorial administration system 182

Acknowledgments 187

Historical Photograph Sources 193

Index 195

CONTENTS Xi

PREFACE

This is the first historical atlas of Tibet to be

made. Though there have been some good car-

tographic surveys of cultural and religious sites

across the Tibetan Plateau and a wealth of studies on

historical Tibetan texts, a basic reference work like this

atlas has long been needed by students and scholars

interested in learning about Tibet. Peter Kessler’s his-

torical cultural atlases of some of the eastern Tibetan

polities were the first true historical atlases of specific

small parts of Tibet. And limited historical coverage of

Tibet was provided in Albert Hermann’s seminal His-

torical and Commercial Atlas of China published in 1935,

in Tan Qixiang’s Zhongguo Lishi Dituji (China histor-

ical atlas, 8 volumes, 1982), and in Joseph Schwartz-

berg’s A Historical Atlas of South Asia (1978). But in

these works Tibet is mapped as merely peripheral to

Asia’s large sedentary agricultural civilizations and not

from its own central position and perspective as a civ-

ilization in its own right. Thus I drew the maps and

wrote the text of this atlas to help meet the need for a

comprehensive series of maps showing the growth and

spread of Tibetan civilization in its entirety in relation

to important places, events, and connections between

regions.

I remember precisely how my idea to make this his-

torical atlas of Tibet first arose. It did so spontaneous-

ly when I was at the Chicago 2005 annual meeting of

the Association for Asian Studies talking with scholars

working on the China historical geographic infor-

mation system. This project was based on the above-

mentioned Zhongguo Lishi Dituji of Tan Qixiang, which

provided a template to copy from. But Tibet lacked any

such comprehensive historical atlas, so I decided then

and there that I was going to provide a clear set of

summary maps of the general course of Tibetan histo-

ry. This sudden decision, coupled with the feeling that

there was no time to waste, partly explains why this

historical atlas of Tibet is an independent work of one

scholar and not a large project with an editorial board

and armies of cartographers.

Making a historical atlas of a civilization for the

first time has presented some advantages amidst sev-

eral disadvantages. On the bright side, each map I

made was often valued by those colleagues I shared it

with as a new resource, and there was usually no simi-

larly detailed map to compare the accuracies or errors

against. But at the same time, I had little cartographic

material to study. Fortunately, as far back as 1993 when

I first embarked on doctoral research in geography, I

began to build up various spatial databases of cultur-

al and religious sites across Tibet. The results of the

subsequent twelve years of research and eight years

of mapmaking, combined with still more research and

database construction, are now finally presented in this

modest atlas. In retrospect, I wish I had another twenty

years to refine and improve this historical atlas, but I

believe it is now sufficient and hope others will find it

of some value.

xiii

NOTES ON GAZETTEER

Phonetic and Literary Romanization

Tibetan place-names on the maps in this atlas, par-

ticularly those of Buddhist temples and monas-

teries, may be searched for online at the Tibetan

Buddhist Resource Center (TBRC.org) to obtain the Ti-

betan orthography and related information about his-

torical persons and texts associated with the sites.

The Tibetan words and place-names in this adas are

rendered phonetically according to the general rules

proposed by the TBRC and the Tibetan and Himalayan

Library (THL). However, I have retained some of the

more well-known phonetic transcriptions of import-

ant places in Tibet used by the British and American

mapmaking authorities of the late nineteenth to mid-

twentieth centuries, such as Shigatse for Shikatse (gZhis

ka rtse), and Gyangtse for Gyantse (rGyal rtse), for the

sake of conventional cross-referencing with other his-

torical maps and adases.

Mention should also be made of the official Roman-

ization system promulgated by the People’s Republic

of China for phonetically transcribing Tibetan place-

names (NSM 1986). According to this system, Shigatse

is romanized as Xigaze, and Gyangtse as Gyangze, for

example.

When Tibetan words and place-names are listed in

literary transliteration preserving the original orthog-

raphy of the Tibetan spellings, I have followed the full

rules of the Wylie system (1959) and capitalized the

radical letter to indicate the pronunciation.

Chinese words and place-names are transcribed

according to the Pinyin system and are phonetically

rendered based on standard Mandarin pronunciation.

Literature Cited

National Survey Ministry (NSM). 1986. Zangyu Lhasa Hua

Diming Yiyin Guize (Tibetan Lhasa dialect place-name

transcription rules). Beijing: Survey Press.

Wylie, Turrell Verl. 1959. “A Standard System of Tibetan Tran-

scription.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 22:261-67.

xv

A NOTE ON SOURCES

Primary Tibetan sources are listed on the maps

themselves so that readers can more clearly relate

mapped features to the historical texts they were

recorded in.

Secondary sources, primarily Chinese and Western

contemporary scholarly works, are listed in the bibli-

ography for each map. Mainland Chinese works pub-

lished after 1949 are listed in Pinyin, but older works

cataloged in the West in the Wade-Giles system have

not been converted.

The only exception to this plan are the approxi-

mately twenty contemporary Tibetan and Chinese-text

survey volumes of Bonpo and Buddhist temples and

monasteries listed in the bibliography of map 5, “The

Structure of Tibetan History.” Given the large number

of these detailed volumes and that the sites they docu-

ment are shown on almost all of the maps in this adas,

they are listed only in this specific map’s bibliography.

xvii

INTRODUCTION

Tibet and the Tibetan culture region

MAP

1

MAP

2

Tibet and surrounding civilizations

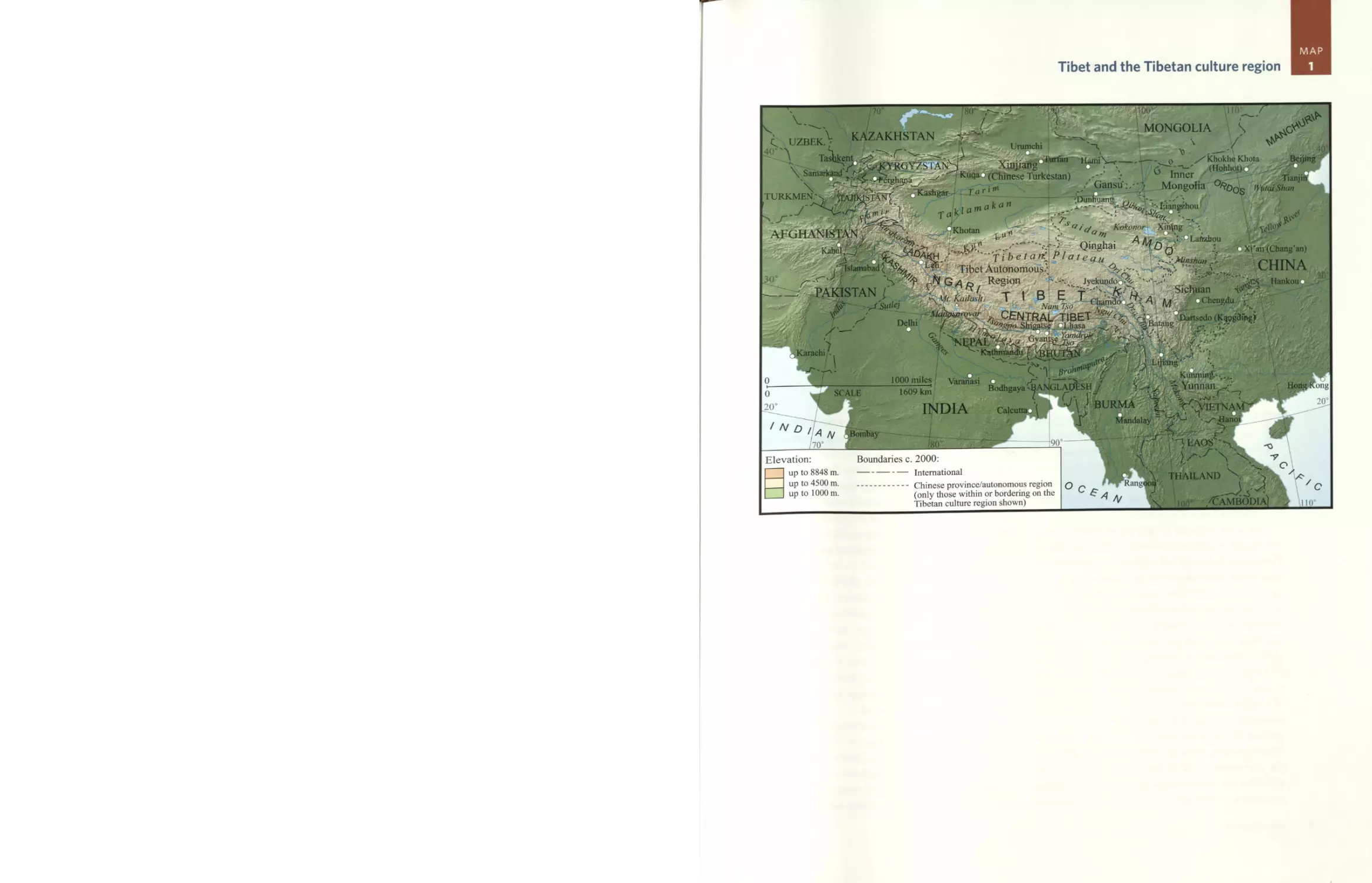

The Tibetan culture region is vast, extending

approximately two thousand miles from west

to east and one thousand miles from north to

south. Tibetans call Tibet Po (spelled Bod in Tibetan,

and pronounced in English like “Poe”). A popular Ti-

betan name for Tibet in the sense of a people’s home-

land is Gangs Ijongs (Snowland).

This atlas attempts to map the historical growth

and spread of Tibetan civilization across the Tibetan

Plateau and bordering hill regions, from prehistorical

times to the annexation of the last Tibetan state by Chi-

na in the 1950s. The Tibet Autonomous Region is a leg-

acy of this last Lhasa-based Tibetan political system. Its

geographical extent roughly corresponds to the lands

that were under both the direct and the indirect rule

of the former Ganden Podrang government, which can

be described as the Kingdom of the Dalai Lamas. But

a view of this central Tibetan political system as part

of a larger civilization is complicated by the fact that

bordering Himalayan kingdoms, which arose out of

political and religious traditions developed under the

Tibetan Empire of the seventh to ninth centuries and

the later development of the various sects of Tibetan

Buddhism in tandem with political patronage during

the tenth to seventeenth centuries, did not always refer

to themselves as Tibetan. Some common characteris-

tics of Tibetan culture include shared origin myths, lan-

guage, and religion. Although common Tibetan cultural

practices helped to characterize these disparate centers

of political authority, long-term patterns of regional

development promoted the manifestation of different

national and ethnic identities in modern times. For

these reasons, most people who now identify as Tibet-

an largely compose the Tibetic-speaking populations

in China. Tibetic language speakers and adherents of

Tibetan Buddhism in Ladakh or Bhutan, for example,

may identify themselves as Ladakhis or Bhutanese, re-

spectively. In fact, a Ladakhi could also choose to iden-

tify as Indian, just as a Tibetan may identify as Chinese.

Given the historical-geographical complexity of this

situation, the purpose of this atlas is partly to allow

readers to view for themselves where and when key

facets of Tibetan culture developed and in what sorts

of regional and political contexts.

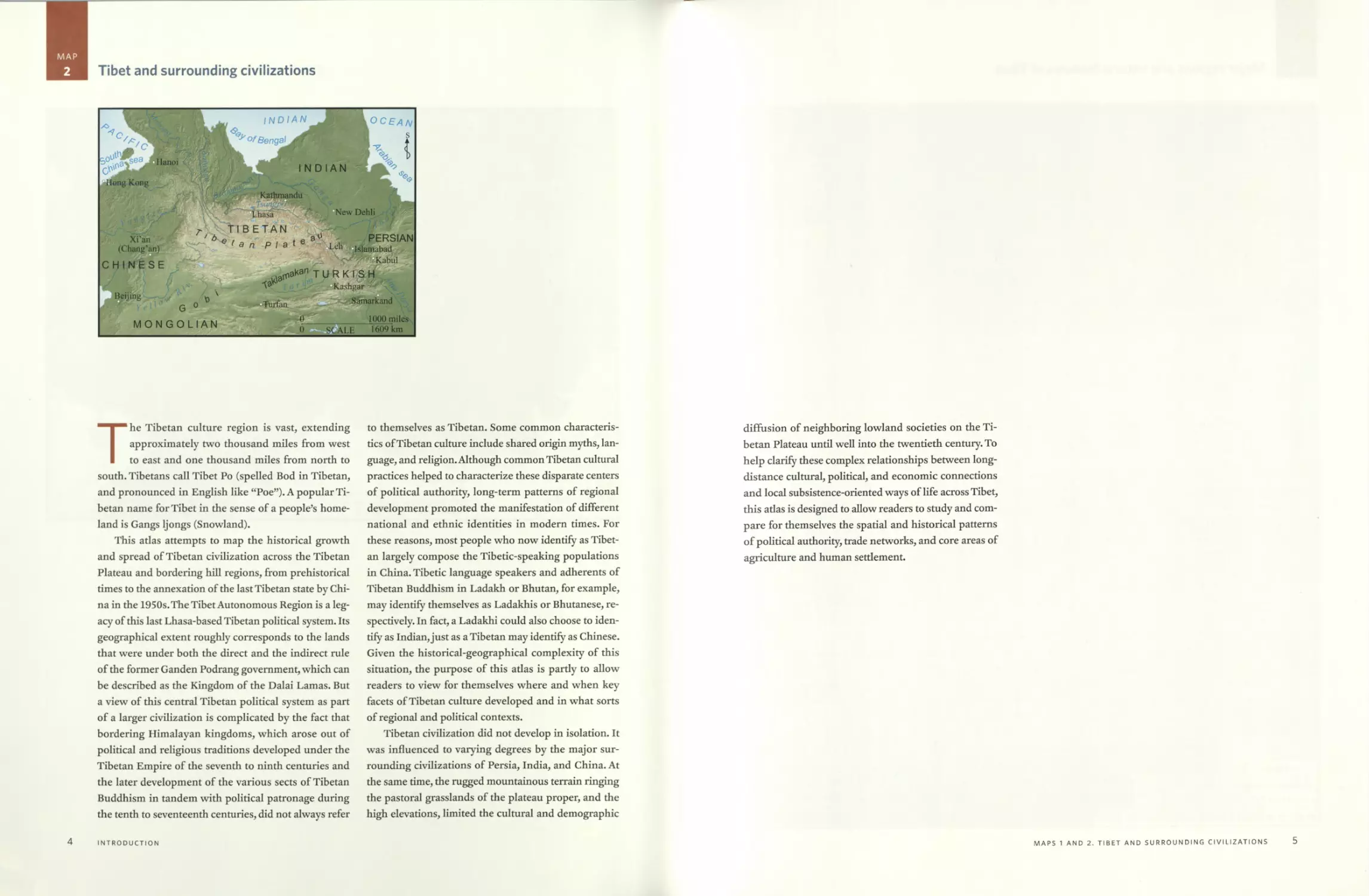

Tibetan civilization did not develop in isolation. It

was influenced to varying degrees by the major sur-

rounding civilizations of Persia, India, and China. At

the same time, the rugged mountainous terrain ringing

the pastoral grasslands of the plateau proper, and the

high elevations, limited the cultural and demographic

4

INTRODUCTION

diffusion of neighboring lowland societies on the Ti-

betan Plateau until well into the twentieth century. To

help clarify these complex relationships between long-

distance cultural, political, and economic connections

and local subsistence-oriented ways of life across Tibet,

this adas is designed to allow readers to study and com-

pare for themselves the spatial and historical patterns

of political authority, trade networks, and core areas of

agriculture and human setdement.

MAPS 1 AND 2. TIBET AND SURROUNDING CIVILIZATIONS

5

MAP

3

Major regions and natural features of Tibet

102"

□ Kashgar

XINJIANG

CHINA

YarkandQ

Charklik

,iangzhou (Wuwei)

QINGHAI

Cherchen

AFG. i

□ Khotan

ulan

Hunza,

Kumb’um

Lanzhou

Dulan

Gilgit

Drakar Dreh

Skardoi

Ngoring

Ragya

Amnye Machen

Alchi

Hem is

^AR

^-.O&ershul

□Dharamsala

DzamtangO

Amritsar

Barkham

laozhou

xrSimla

Hru

iRiw<

DPelyul

'hamdo

| Nyenchen Tangla;

Ci Dehra Dun

Dark

Litang

1 HBatang

INDIA

Shukden

Delhi

Chung RiwochF^4

hawa Kai

OTarlam

>khara

Sadiya

,ijiang

BURMA

Tezpuri

Major Polity Boundary/Frontier c. 1900

ining

Drol

Loess

Plateau

Shazhou

(Dunhuang)

Suzhou

(Jiuquan)

Srinagar

Vale of

Kashmir

Ngonpo

(Koko Nor)

Elevation:

— i snow/glacier

___up to 8848 m.

___up to 4400 m.

__I up to 2750 m.

veixi

•alung)

Taktsang Lhamo

XOTaklung

^L^Ya'riung Thurchen

□ City

□ Town

О Monastery

A Sacred mountain

----Main trade route

Ganzhou'[j4 '

(Zhangye)

Mati

RUSSIAN/

EMPIRE 4

Risurh xMuli

Jumla ° ^LoM]

SilkZR'o'ad" Ni*a

Sichuan

Ya/hou ~

□ Basin

DZOGfc

oMewa

Gar

xЛ A Shar Dungri

MuSc Songpan

Shubam —-— }

n«ii‘ LsRiwoJakans

UallD (Jizu Shan),(

lergep'

7\<)Palbung

Murdo Vx

DMougong JTChengdu

iRongwo /Hezhou

\2 , h GANSU

Qj Labrang

\ Choneo

Nyanpo Yurtsef$S*Q™dn%

^iGABA

Bonri

KONGpn A

Jyegu Dondrubling

jyekundo

'ang Rinpoche (Kailash)

'Mapani Yumho (Manasarov ir/

Р-,- 'Vhomolangnia** w 4i

Kathmandu (Evet^st) GaigchenLM^S /

. / Dzonga '

C/NEPAL

^D^ee,ln^^aliSp<w

A NG ° PANPO

6)g ‘ Tsurpbu Gandcn

./ ' Чина .

,zz GANDE> №RANg4 % Д"-

___C »i л. d У____________—— -------

100. km

100 miles

SCALE

FsakkalhoiO. 2 V- Sa*?pheIins

(Yanjtag) . \ 3 G<

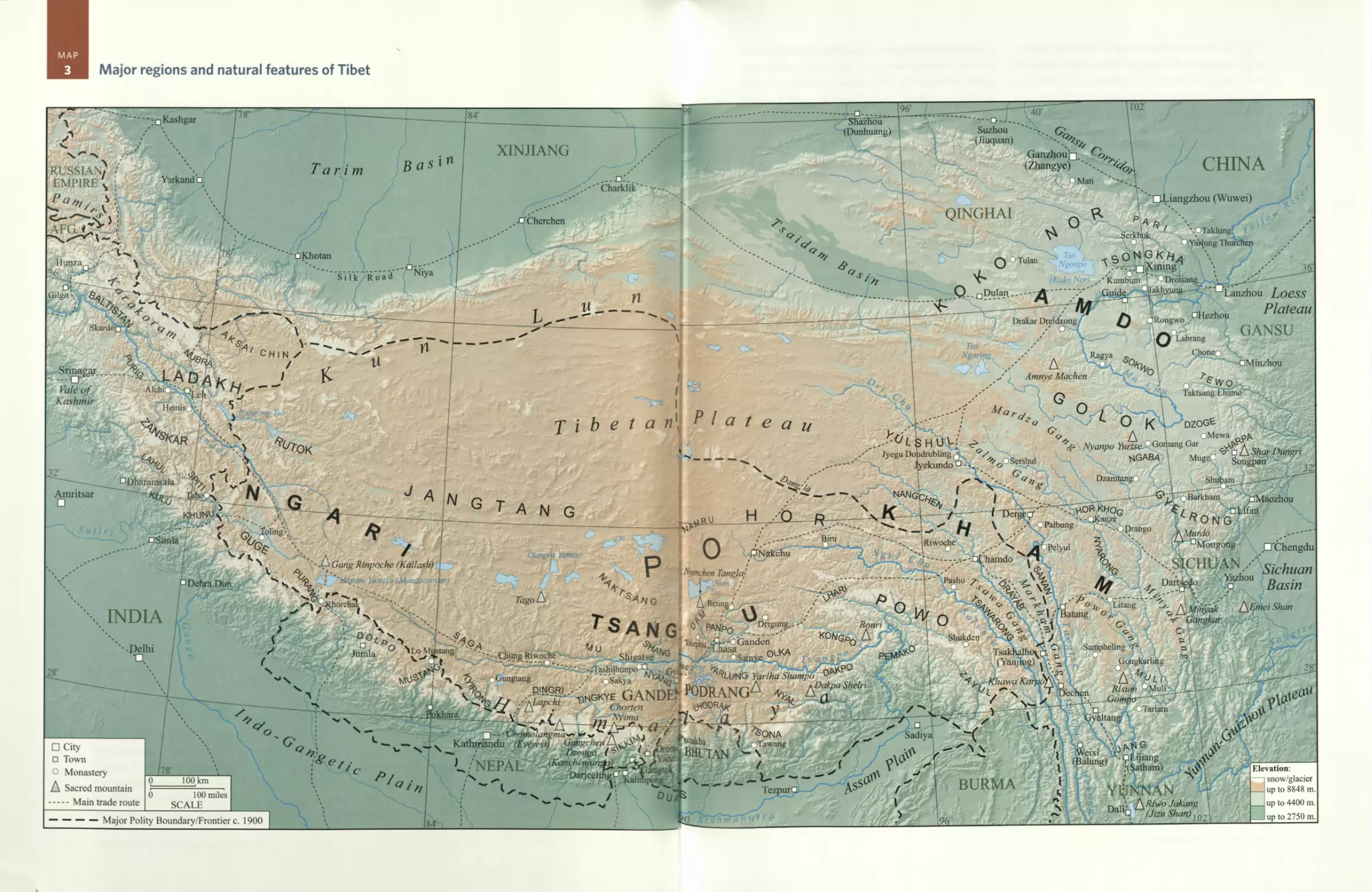

The history of Tibet is largely the history of local-

ities. Given the rugged terrain, high elevations,

and local-based agricultural subsistence econ-

omies of Tibetan communities historically, the study

of empires, kingdoms, and famous people cannot ad-

equately encompass the social and environmental his-

tory of Tibet. The purpose of this map is to show the

main macro- and meso-scale folk regions and areas fre-

quently mentioned in historical Tibetan literature, and

also foreign travelogues, which became increasingly

common by the early twentieth century. In making this

map, I paid particular attention to how the regions and

places that composed Tibet were described in a text

about the geography of the world (’Dzam gling rgyas

bshad) byjampel Chokyi Tenzin Trinle (1789-1839).

This is one of the rare historical Tibetan texts to deal

with the entire geographical extent of Tibet. As such,

this map largely names regions and natural features

according to conventions of the nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries. For insights into what these re-

gions and areas were called in Tibetan, and to a lesser

extent Chinese, during earlier times, primarily during

the Imperial, Second Diffusion of Buddhism, and Mon-

gol Empire Periods, readers should refer to the appro-

priate historical maps in this adas.

The most common Tibetan name for the Lhasa-

based government of Tibet during the period 1642-

1951 was Depa Zhung (sDe pa gzhung; authority cen-

ter). Its formal name Ganden Podrang, taken from the

name of an earlier palace in the great monastery of

Drepung in the Lhasa Valley, is used in this atlas to

indicate what became generally construed as “political

Tibet” during the colonial period, especially after the

fall of China’s Qing Dynasty in 1911 and the rise of

a de facto independent Tibetan state. Despite contem-

porary political debates over these earlier statuses of

Tibet, traditional geographical descriptions of the Ti-

betan culture region do not place much emphasis on

this last indigenous Lhasa-based government. Instead,

the entire plateau-wide “Snowland” (Gangs Ijongs)

tends to be perceived as Tibet with its own distinctive

places and ways of life. For reference purposes, I have

indicated the approximate boundaries and frontiers of

Ganden Podrang on this map in the sense of a polity

with its own patently territory-based forms of political

administration.

Most historical Tibetan texts with significant geo-

graphical relevance to particular places and regions are

devoted to the description of individual Buddhist mon-

asteries, temples, statues, and the like and are usually

called catalogs (dKar chag). In addition, there is a rich

travel genre (gNasyig) including route descriptions and

pilgrimage itineraries to sacred sites across Tibet and

beyond to foreign lands, primarily India and China.

These sorts of works are far too numerous to address

in this map, except in cases where the name of a partic-

ularly famous monastery and nearby town came over

time to be commonly used as the name for the larger

locale or region, such as with Riwoche and Chamdo in

Central Kham and Labrang and Chone in Amdo. For

this reason I include most of the larger and historically

important monasteries, as well as certain towns, on this

map, and they should generally be understood to indi-

cate popular names for the surrounding areas.

Traditional Tibetan spatial concepts treat the geog-

raphy of Tibet as consisting of a western “upper” re-

gion of Ngari, a central “middle” region of U-Tsang,

and eastern “lower” regions of Kham and Amdo. These

four macro regions are often further divided by Tibetan

writers into additional upper and lower regions, such

as Tsang To (gTsang sTod; upper Tsang) and Tsang Me

(gTsang sMad; lower Tsang), and a wide assortment of

smaller areas and locales primarily consisting of agri-

cultural valleys (Yul, gRong) and pastoral highlands

(sGang, ’Brog). Geographers term these sorts of intel-

lectual constructs perceptual regions (also folk or ver-

nacular regions). Unlike formal regions based on the

distribution of a specific cultural trait or functional

regions defined by networks of social interaction, per-

ceptual regions are believed to exist. For this reason, it

is not possible to map specific areas and boundaries of

perceptual regions. In this atlas I indicate the approxi-

mate core areas and general extents of Tibet’s main folk

or perceptual regions by placing each region’s name

across the relevant map areas.

Ngari, at its greatest extent, stretches from the

Gungtang and Saga areas as far west as Ladakh. In

ancient times this region was called Zhangzhung. But

over time Ngari came to be considered the western part

of the Tibetan Plateau proper, centered on the sacred

mountain Gang Rinpoche (Kailash) and excluding bor-

dering Himalayan and Karakoram regions from Mus-

tang and Dolpo in the east and Ladakh and Baltistan

in the west. One way to visualize specific areas and

boundaries of broadly defined folk regions is by map-

ping related cultural variables and social networks of

8

INTRODUCTION

either formal or functional regions. For example, map 7

of the Tibetic languages shows the distribution of the

Ngari (i.e.,To Ngari) dialect of the U-Tsang Tibetic lan-

guage, and this particular mapping may be understood

as one of many possible interpretations of Ngari’s west-

ern geographic extent. Interestingly, both the Ngari and

U-Tsang macroregions share the same prestige U-Tsang

language within the geolinguistic continuum of Tibet’s

central language section, unlike the much clearer re-

gional divides from, and between, the Amdo and Kham

languages.

U-Tsang, or Central Tibet, is centered on Tibet’s

main city of Lhasa and mosdy lies in the watershed of

the great YarlungTsangpo. The name U-Tsang is a com-

bination of U, denoting the Lhasa region, and Tsang

based on the towns of Gyangtse and Shigatse. Core ag-

ricultural valleys, such as that of the Nyang in Tsang

and the Kyi Chu in U, are clearly understood as part

of U-Tsang proper, but many surrounding Himalayan

regions like Lhodrak and Dingri are more loosely tied

to spatial definitions of Central Tibet. And stretching

northward, the Jangtang (i.e., Chang thang; northern

grassy plain) formed a vaguely defined and sparsely

populated zone between the core areas of Central and

Western Tibet.

The eastern Tibetan regions may also be understood

as consisting of fairly well defined historical core areas,

such as Chamdo and Derge in Kham and Tsongkha in

Amdo, while similarly vast and vaguely defined folk re-

gions historically separated these core areas from one

another. The Hor and Powo regions separated Kham

from U-Tsang, while the Golok and Gyelrong regions

separated Kham from Amdo.

Below the vast scale of regions, Tibetan writers of-

ten employ the term sDe (pronounced like “day”) for a

local group such as a tribe, district, or community, or

even a group of religious practitioners. Among agricul-

tural communities the term rong (gRong) is frequently

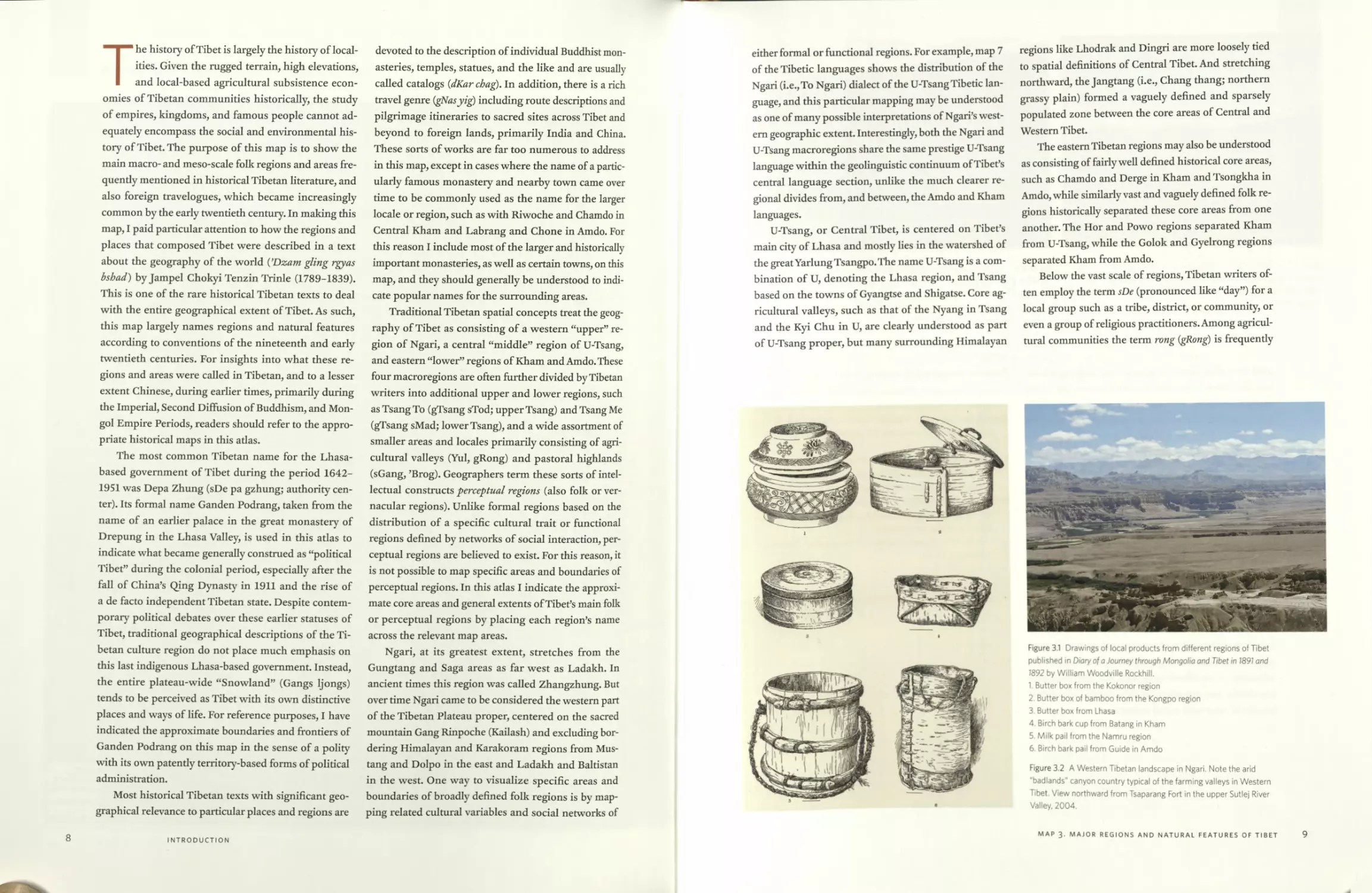

Figure 3.1 Drawings of local products from different regions of Tibet

published in Diary of a Journey through Mongolia and Tibet in 1891 and

1892 by William Woodville Rockhill.

1. Butter box from the Kokonor region

2. Butter box of bamboo from the Kongpo region

3. Butter box from Lhasa

4. Birch bark cup from Batang in Kham

5. Milk pail from the Namru region

6. Birch bark pail from Guide in Amdo

Figure 3.2 A Western Tibetan landscape in Ngari. Note the arid

badlands" canyon country typical of the farming valleys in Western

Tibet. View northward from Tsaparang Fort in the upper Sutlej River

Valley, 2004.

MAP 3. MAJOR REGIONS AND NATURAL FEATURES OF TIBET

9

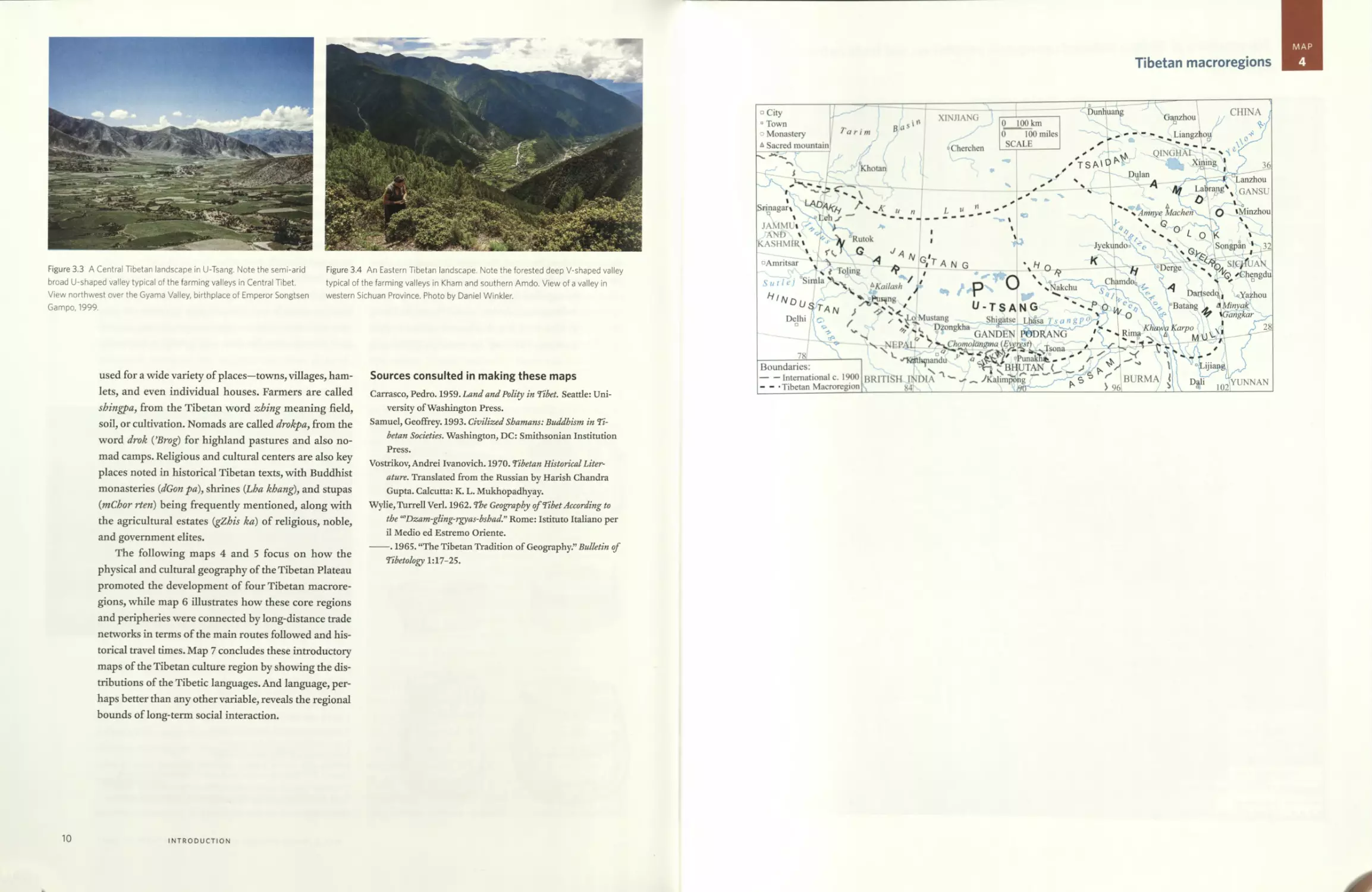

Figure 3.3 A Central Tibetan landscape in U-Tsang. Note the semi-arid

broad U-shaped valley typical of the farming valleys in Central Tibet.

View northwest over the Gyama Valley, birthplace of Emperor Songtsen

Gampo, 1999.

Figure 3.4 An Eastern Tibetan landscape. Note the forested deep V-shaped valley

typical of the farming valleys in Kham and southern Amdo. View of a valley in

western Sichuan Province. Photo by Daniel Winkler.

used for a wide variety of places—towns, villages, ham-

lets, and even individual houses. Farmers are called

shingpa, from the Tibetan word zhing meaning field,

soil, or cultivation. Nomads are called drokpa, from the

word drok ("Brog) for highland pastures and also no-

mad camps. Religious and cultural centers are also key

places noted in historical Tibetan texts, with Buddhist

monasteries (dGon pa), shrines (Lha khang), and stupas

(mChor rteri) being frequendy mentioned, along with

the agricultural estates (gZhis ka) of religious, noble,

and government elites.

The following maps 4 and 5 focus on how the

physical and cultural geography of the Tibetan Plateau

promoted the development of four Tibetan macrore-

gions, while map 6 illustrates how these core regions

and peripheries were connected by long-distance trade

networks in terms of the main routes followed and his-

torical travel times. Map 7 concludes these introductory

maps of the Tibetan culture region by showing the dis-

tributions of the Tibetic languages. And language, per-

haps better than any other variable, reveals the regional

bounds of long-term social interaction.

Sources consulted in making these maps

Carrasco, Pedro. 1959. Land and Polity in Tibet. Seatde: Uni-

versity of Washington Press.

Samuel, Geoffrey. 1993. Civilized Shamans: Buddhism in Ti-

betan Societies. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution

Press.

Vostrikov, Andrei Ivanovich. 1970. Tibetan Historical Liter-

ature. Translated from the Russian by Harish Chandra

Gupta. Calcutta: K. L. Mukhopadhyay.

Wylie, Turrell Verl. 1962. The Geography of Tibet According to

the iaDzam-gling-rgyas-bshad.” Rome: Istituto Italiano per

il Medio ed Estremo Oriente.

----. 1965. “The Tibetan Tradition of Geography.” Bulletin of

Tibetology 1:17-25.

10

INTRODUCTION

MAP

4

Tibetan macroregions

MAP

5

The structure of Tibetan history: Core regions, peripheries, and trade networks

circa 1900

□ Amritsar

v. 5* и 11

Delhi

Charklik'

'Cherchen

Khotan

chin

□ Ri

Ytn

Daw:

BRITISH INDIA

siik'Koia" TNiy*

Buddhist and Bon Monasteries per 1000 sq km:

0

XINJIANG

0.000001 -3.0

3.0- 12.0

12.0-280.1

a r i

Basin

Boundaries / Frontiers (approximate)

— — — International

- - - - • Chinese province/dependency

^^-G a n g e t i c p/^

- Yem

--------____________

□ City

□ Town/trade center

О Monastery

A Sacred mountain

----Main trade route

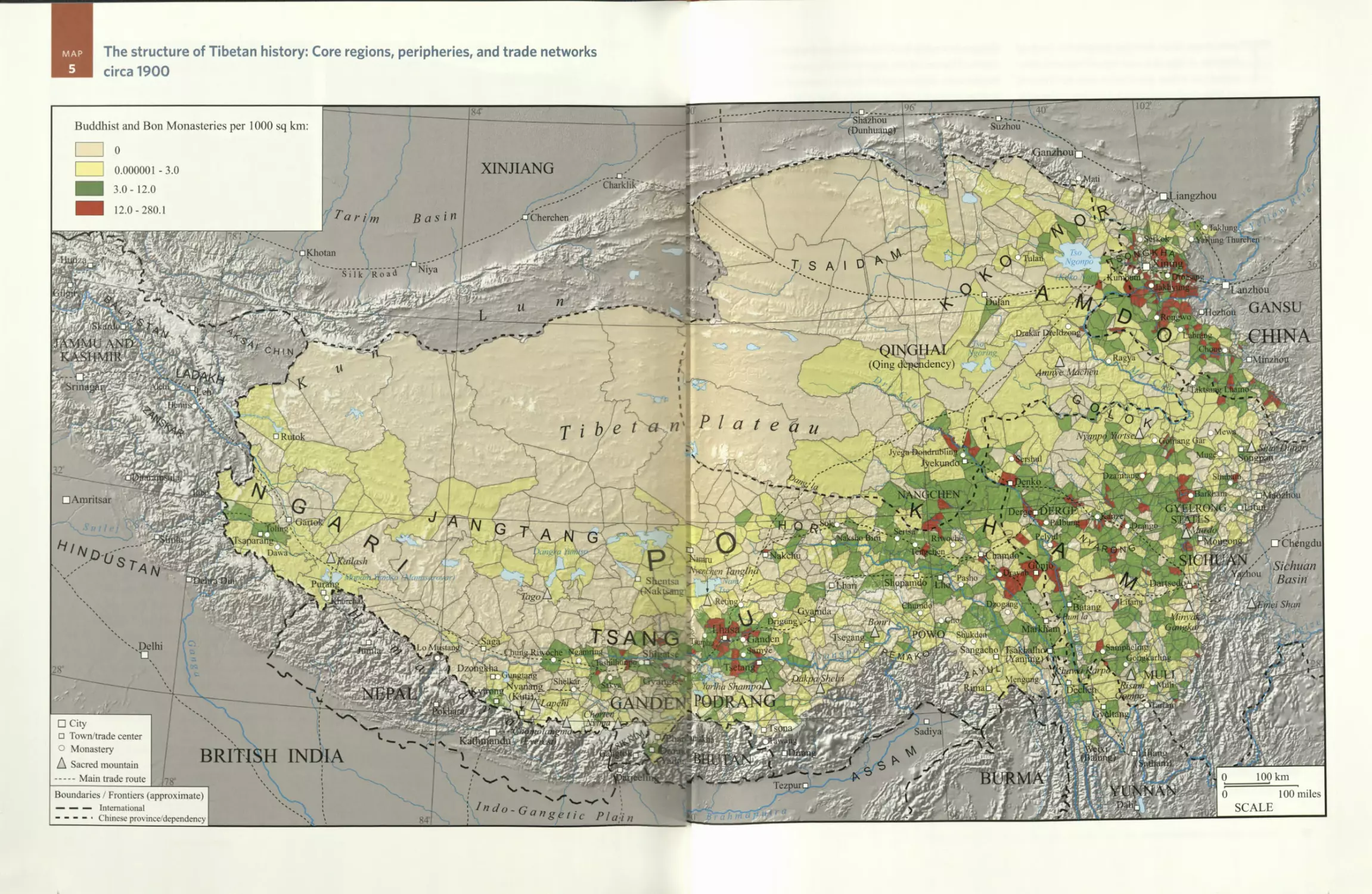

These maps show how the geographic basis of

Tibetan civilization consists of four core mac-

roregions where population and agricultural

resources historically concentrated in river valleys due

to the physical geography of the plateau. Specifically,

map 5 illustrates the spatial variation in local densities

of Buddhist and Bonpo monasteries. In a country of

few cities and towns, the monasteries historically func-

tioned as important centers of political and economic

activity. Their historical constructions across Tibet

from about 600 to 1950 may be studied as one key mea-

sure of local economic development. In contrast, most

studies of Tibetan history base generalizations about

regional and national development on historical peri-

ods, not as this map attempts to do by placing relevant

disaggregated data in a fine-grained spatial framework

that reflects the actual macroregional structure of Ti-

bet’s economies and societies in the past. To some ex-

tent these regional patterns were altered by increased

population growth and migration across China since

the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949; thus

modern Chinese census data cannot be trusted to dif-

ferentiate between the historical core areas of Tibetan

settlement and the peripheries. It is estimated that prior

to the 1950s, approximately one-quarter of Tibet’s male

population consisted of Buddhist monks.

The locations of 2,925 Buddhist and Bonpo temples

and monasteries were mapped to model these spatial

and temporal patterns of Tibet’s historical macrore-

gional structure. In order for the densities of these reli-

gious sites to be calculated within 1,962 contemporary

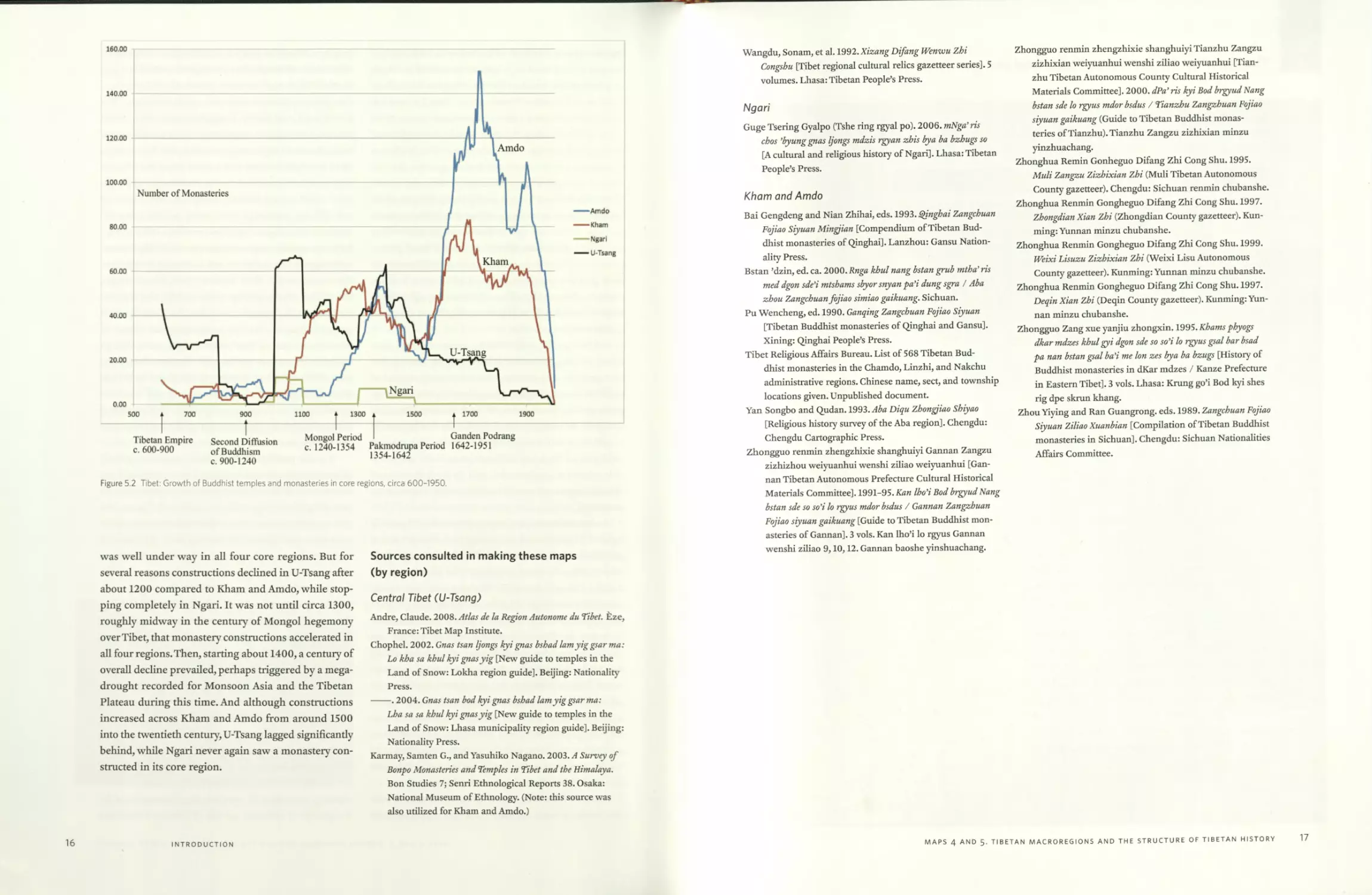

Figure 5.1 Ganden Monastery, Central Tibet. Large crowds gather for

a religious festival, July 1998.

Chinese township-level administrative divisions cover-

ing the Tibetan culture region in China, ecumen areas

were measured based on land cover types in the digital

version of the 1:1 Million Land-Use Map of China, These

land use/cover data can be seen in map 47, “Main Land

Cover Patterns of the Tibetan Plateau.” Areas of water,

bare rock, and snow or ice were excluded from the fi-

nal calculations so that the results would most accu-

rately reflect the densities of temples and monasteries

in relation to actual forms of land use based on such

economically important land cover types as grasslands,

cultivated lands, and forests.

The approximately three thousand Buddhist sites

georeferenced to make this map derive from twenty

years of research by numerous scholars working from

many different sources. To some extent, all the maps in

this atlas, starting from map 11 of the Tibetan Empire

through to the last historical period view presented in

map 45 of the greater Beijing area, show the growth

and spread of these Buddhist sites. As stated in the

acknowledgments section in reference to regional

systems theory, developed by the late George William

Skinner, I realized in 2005 that I could make a series

of time period maps from these religious site databases

to form the skeletal framework for a historical atlas of

Tibet. For this reason, the bibliography for this map of

the core regions of Tibet’s historical development is

very detailed and extensive in covering mainly Tibetan-

and Chinese-language survey volumes that document

Tibetan Buddhist and Bonpo temples and monasteries

across the different counties, prefectures, and provinces

that today cover the Tibetan culture region in China.

Readers should refer to these nineteen key sources for

information about specific religious sites.

As noted earlier, historical Tibetan texts often de-

scribe the geography of Tibet in terms of a western “up-

per” region of Ngari, a central “middle” region of U-

Tsang, and eastern “lower” regions of Dokham, which

in recent centuries have come to be called Amdo and

Kham. These literary accounts can be verified in the

core-periphery patterns on this map. Ngari includes sa-

cred Mt. Kailash and the source of the Indus and Ganga

(Ganges) Rivers. U-Tsang includes the holy city of

Lhasa and is watered by Tibet’s great river the Yarlung

Tsangpo. The name U-Tsang is a combination of U, de-

noting the eastern Lhasa region, and Tsang, covering

the western part based on the towns of Gyangtse and

Shigatse. Eastern Tibet or Kham is a vast region cover-

14

INTRODUCTION

ing the upper watersheds of the Salween, Mekong, and

Yangtze Rivers, from high plateau grasslands to where

they merge into bamboo forests along the foothills of

Sichuan and Yunnan. Northeastern Tibet, or Amdo, is

based on the farming valleys in the upper Yellow River

watershed bordering the deserts and loess regions of

Gansu. In fact, Amdo is noteworthy as the only Tibetan

macroregion with a core zone that merges into the core

zone of a neighboring civilization, in this case that of

Northwest China. The topography along this part of the

Tibetan Plateau is less rugged than that of the southern

Himalayan frontier, and it slowly merges into valleys

and desert plains through which the Silk Road passes.

Historically these factors led a number of different cul-

tural groups to setde along the Amdo-Gansu frontier,

and an understanding of how Amdo’s core region func-

tioned economically in relation to Northwest China re-

quires further research.

At first glance, only U-Tsang appears to be a mac-

roregion itself, given that it is completely surrounded

by a periphery. In contrast, the outer macroregions of

Ngari, Kham, and Amdo merge into core lowland re-

gions of East, Southeast, and South Asian civilizations

along the descending river valleys. It is also important

to point out that comparable data for Ladakh, consid-

ered part of Ngari in ancient times, were not avail-

able when I made this adas, and so the full extent of

this macroregion’s core is not discernible but must be

estimated.

I also estimated the southern extent of Amdo in

light of linguistic data pertaining to the geographical

distribution of the Amdowa Tibetic languages (see

map 7, “The Tibetic Languages”) in addition to the

Buddhist temple densities. This approach was neces-

sary due to the high densities in the Gyelrong valleys

that appear, at first glance, to be part of the Kham mac-

roregion. But linguistic patterns tentatively support

placing at least the northern part of Gyelrong within

the Amdo macroregion. A shared language, perhaps

better than any other variable, points toward histori-

cal social interaction among communities. Though it

is reasonable to speculate that there in recent centu-

ries was greater economic interaction between com-

munities in Gyelrong and the Sichuan Basin than with

Amdo. Further research is required to better delineate

the extent of Amdo in regard to Gyelrong.

Prior to the 1950s, travel up the river valleys onto

the plateau proper was often not easy owing to steep

gorges, subtropical jungles, and isolated independent

tribes. And, although the core regions of Western and

Eastern Tibet were at times politically independent,

they always produced their own staple food items like

butter, meat, and barley. Long-distance trade in items

like tea and salt was important to the economies of

both Tibet and neighboring countries, but the caravans

often avoided the river valleys and instead went over

high mountain passes where the routes were generally

more suited to pack animals, being wider and less steep

and offering pasturage. Also, many passes along the

southern Himalayan frontier were impassible except

for a few months each summer, due to the high snow-

falls triggered by India’s monsoon climate. Travel from

China and the Silk Road south to Tibet, though longer,

was often easier than from India because the Himala-

yas created a dry rain shadow across the plateau, which

tended to keep the interior passes open year round. In

this way we can see how Tibetan civilization, though

spread over four core regions, still functioned relatively

independently of surrounding political and economic

systems throughout most of its history and was inte-

grated between its cores, peripheries, and bordering

cultures mainly by long-distance trade in some staples

and luxury items.

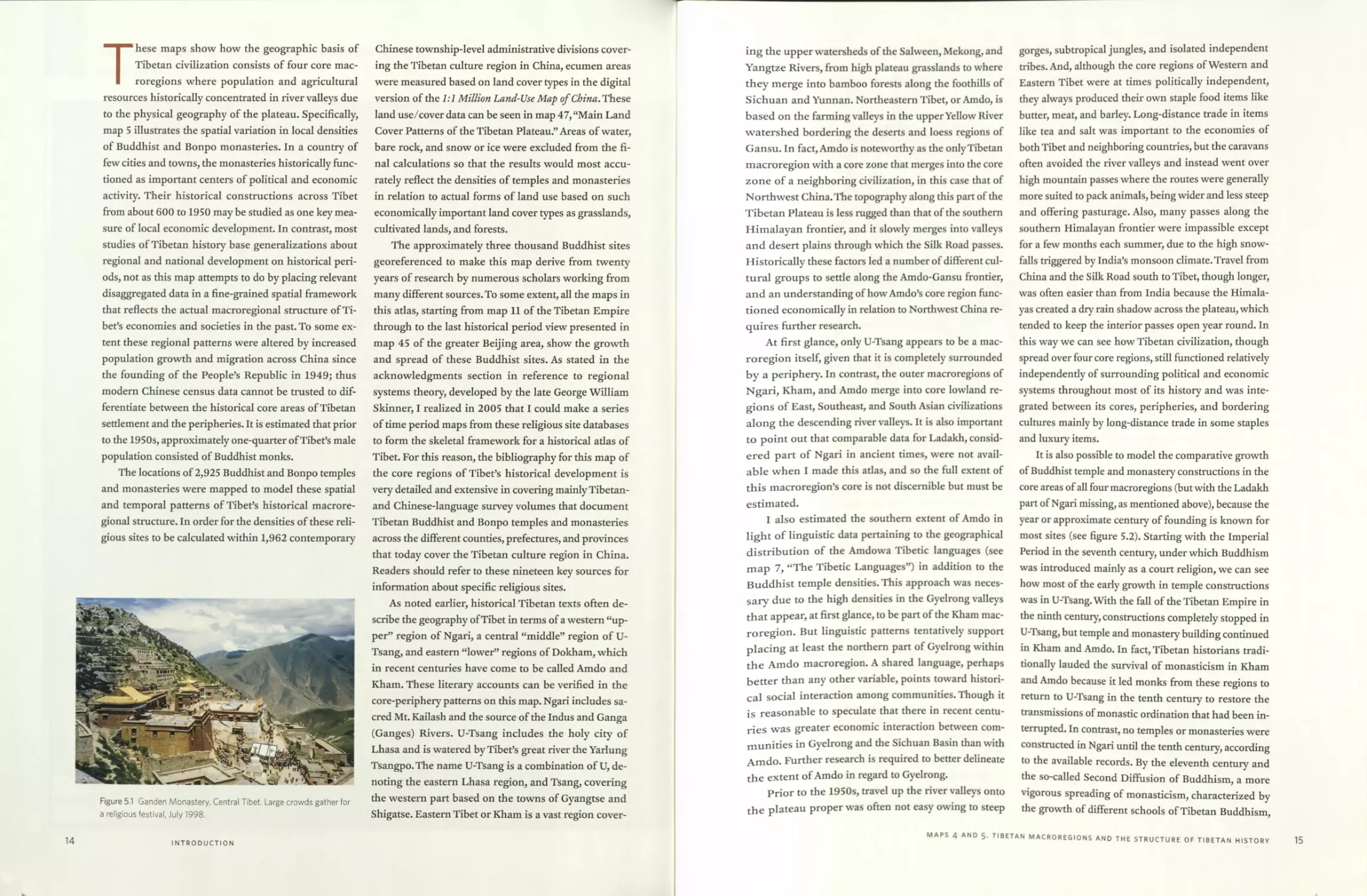

It is also possible to model the comparative growth

of Buddhist temple and monastery constructions in the

core areas of all four macroregions (but with the Ladakh

part of Ngari missing, as mentioned above), because the

year or approximate century of founding is known for

most sites (see figure 5.2). Starting with the Imperial

Period in the seventh century, under which Buddhism

was introduced mainly as a court religion, we can see

how most of the early growth in temple constructions

was in U-Tsang. With the fall of the Tibetan Empire in

the ninth century, constructions completely stopped in

U-Tsang, but temple and monastery building continued

in Kham and Amdo. In fact, Tibetan historians tradi-

tionally lauded the survival of monasticism in Kham

and Amdo because it led monks from these regions to

return to U-Tsang in the tenth century to restore the

transmissions of monastic ordination that had been in-

terrupted. In contrast, no temples or monasteries were

constructed in Ngari until the tenth century, according

to the available records. By the eleventh century and

the so-called Second Diffusion of Buddhism, a more

vigorous spreading of monasticism, characterized by

the growth of different schools of Tibetan Buddhism,

MAPS 4 AND 5. TIBETAN MACROREGIONS AND THE STRUCTURE OF TIBETAN HISTORY

15

Figure 5.2 Tibet: Growth of Buddhist temples and monasteries in core regions, circa 600-1950.

was well under way in all four core regions. But for

several reasons constructions declined in U-Tsang after

about 1200 compared to Kham and Amdo, while stop-

ping completely in Ngari. It was not until circa 1300,

roughly midway in the century of Mongol hegemony

over Tibet, that monastery constructions accelerated in

all four regions.Then, starting about 1400, a century of

overall decline prevailed, perhaps triggered by a mega-

drought recorded for Monsoon Asia and the Tibetan

Plateau during this time. And although constructions

increased across Kham and Amdo from around 1500

into the twentieth century, U-Tsang lagged significandy

behind, while Ngari never again saw a monastery con-

structed in its core region.

Sources consulted in making these maps

(by region)

Central Tibet (U-Tsang)

Andre, Claude. 2008. Atlas de la Region Autonome du Tibet. Eze,

France: Tibet Map Institute.

Chophel. 2002. Gnas tsan Ijongs kyi gnas bshad lamyiggsarma:

Lo kha sa khul kyi gnasyig [New guide to temples in the

Land of Snow: Lokha region guide]. Beijing: Nationality

Press.

----. 2004. Gnas tsan bod kyi gnas bshad lamyiggsar ma:

Lha sa sa khul kyi gnasyig [New guide to temples in the

Land of Snow: Lhasa municipality region guide]. Beijing:

Nationality Press.

Karmay, Samten G., and Yasuhiko Nagano. 2003. A Survey of

Bonpo Monasteries and Temples in Tibet and the Himalaya.

Bon Studies 7; Senri Ethnological Reports 38. Osaka:

National Museum of Ethnology. (Note: this source was

also utilized for Kham and Amdo.)

16

INTRODUCTION

Wangdu, Sonam, et al. 1992.Xzz«w^ Difang Wenwu Zhi

Congshu [Tibet regional cultural relics gazetteer series]. 5

volumes. Lhasa: Tibetan People’s Press.

Ngari

Guge Tsering Gyalpo (Tshe ring rgyal po). 2006. mNga’ris

chos ’byung gnas Ijongs mdzis rgyan zhis by a ba bzhugs so

[A cultural and religious history of Ngari]. Lhasa: Tibetan

People’s Press.

Kham and Amdo

Bai Gengdeng and Nian Zhihai, eds. 1993. Qinghai Zangchuan

Fojiao Siyuan Mingjian [Compendium of Tibetan Bud-

dhist monasteries of Qinghai]. Lanzhou: Gansu Nation-

ality Press.

Bstan ’dzin, ed. ca. 2000. Rnga khul nang bstan grub mtha’ ris

med dgon sde’i mtshams sbyorsnyan pa’i dung sgra / Aba

zhou Zangchuan fojiao simiao gaikuang. Sichuan.

Pu Wencheng, ed. 1990. Ganqing Zangchuan Fojiao Siyuan

[Tibetan Buddhist monasteries of Qinghai and Gansu].

Xining: Qinghai People’s Press.

Tibet Religious Affairs Bureau. List of 568 Tibetan Bud-

dhist monasteries in the Chamdo, Linzhi, and Nakchu

administrative regions. Chinese name, sect, and township

locations given. Unpublished document.

Yan Songbo and Qudan. 1993. Aba Diqu Zhongjiao Shiyao

[Religious history survey of the Aba region]. Chengdu:

Chengdu Cartographic Press.

Zhongguo renmin zhengzhixie shanghuiyi Garman Zangzu

zizhizhou weiyuanhui wenshi ziliao weiyuanhui [Gan-

nan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture Cultural Historical

Materials Committee]. 1991-95. Kan Iho’i Bod brgyud Nang

bstan sde so so’i lo rgyus mdor bsdus / Gannan Zangzhuan

Fojiao siyuan gaikuang [Guide to Tibetan Buddhist mon-

asteries of Gannan]. 3 vols. Kan Iho’i lo rgyus Gannan

wenshi ziliao 9,10,12. Gannan baoshe yinshuachang.

Zhongguo renmin zhengzhixie shanghuiyi Tianzhu Zangzu

zizhixian weiyuanhui wenshi ziliao weiyuanhui [Tian-

zhu Tibetan Autonomous County Cultural Historical

Materials Committee]. 2000. dPa’ ris kyi Bod brgyud Nang

bstan sde lo rgyus mdor bsdus / Tianzhu Zangzhuan Fojiao

siyuan gaikuang (Guide to Tibetan Buddhist monas-

teries of Tianzhu). Tianzhu Zangzu zizhixian minzu

yinzhuachang.

Zhonghua Remin Gonheguo Difang Zhi Cong Shu. 1995.

Muli Zangzu Zizhixian Zhi (Muli Tibetan Autonomous

County gazetteer). Chengdu: Sichuan renmin chubanshe.

Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Difang Zhi Cong Shu. 1997.

Zhongdian Xian Zhi (Zhongdian County gazetteer). Kun-

ming: Yunnan minzu chubanshe.

Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Difang Zhi Cong Shu. 1999.

Weixi Lisuzu Zizhixian Zhi (Weixi Lisu Autonomous

County gazetteer). Kunming: Yunnan minzu chubanshe.

Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo Difang Zhi Cong Shu. 1997.

Deqin Xian Zhi (Deqin County gazetteer). Kunming: Yun-

nan minzu chubanshe.

Zhongguo Zang xue yanjiu zhongxin. 1995. Khams phyogs

dkar mdzes khul gyi dgon sde so so’i lo rgyus gsal bar bsad

pa nan bstan gsal ba’i me Ion zes bya ba bzugs [History of

Buddhist monasteries in dKar mdzes / Kanze Prefecture

in Eastern Tibet]. 3 vols. Lhasa: Krung go’i Bod kyi shes

rig dpe skrun khang.

Zhou Yiying and Ran Guangrong. eds. 1989. Zangchuan Fojiao

Siyuan Ziliao Xuanbian [Compilation of Tibetan Buddhist

monasteries in Sichuan]. Chengdu: Sichuan Nationalities

Affairs Committee.

MAPS 4 AND 5. TIBETAN MACROREGIONS AND THE STRUCTURE OF TIBETAN HISTORY

17

The historical Tibetan world: Travel time and main trade patterns circa 1900

MAP

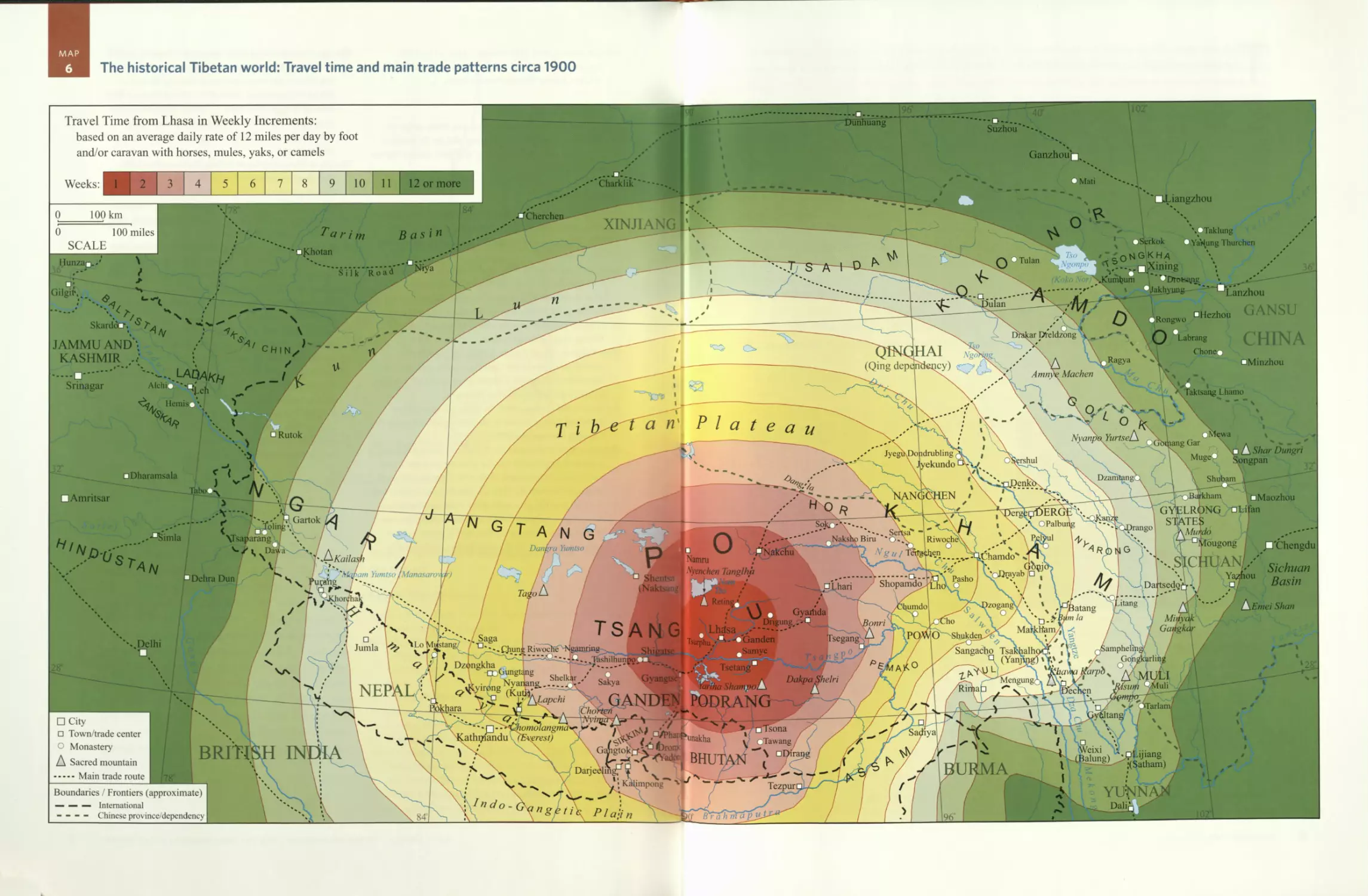

This map shows the distances that travelers,such

as traders and pilgrims, covered in weekly incre-

ments by either walking or riding along routes

radiating outward from Lhasa to an outer mapped limit

of three months. Traditional forms of travel persisted

in Tibet well into the mid-twentieth century, because

the first roads for motorized vehicles were not built

until the 1950s. Previously it had taken about three

months for travelers from oudying parts of the Tibetan

Plateau, such as the Amdo frontier in Gansu Province,

the foothills along the Sichuan Basin, and Ladakh in

western Tibet, to reach Lhasa. It is important to real-

ize, however, that elite travelers such as government

officials and couriers often made much better time due

to the fresh horses and supplies they could obtain at

official stations along the main routes. Without such

support, the average traveler made about twelve miles

a day, whether walking or riding, because the pack ani-

mals needed to spend roughly half of each day grazing

to meet their nutritional requirements if grain was not

directly fed to them. And in the eastern Himalayas, in

parts of Powo and Zayul, and all through the jungle

regions bordering on the plains of Assam, many routes

were not passable by pack animals, and porters often

made five miles a day at best. The most common pack

animals were horses, mules, and yaks, with the mules

favored due to their ability to go farther on smaller

amounts of food. Indeed, much of the bulk tea carried

to Tibet from China on yaks was frequently transferred

among the herds of different nomadic groups so the

animals would not tire and become useless after about

one week when used in this manner. Bactrian cam-

els were sometimes used too in the northern Tibetan

regions of Amdo and Ladakh, which are closer to the

Central Asian Silk Road routes, where camels are still

widely used as pack animals.

Over thousands of years, well before Tibetan writ-

ten records first appeared during the Tibetan Imperi-

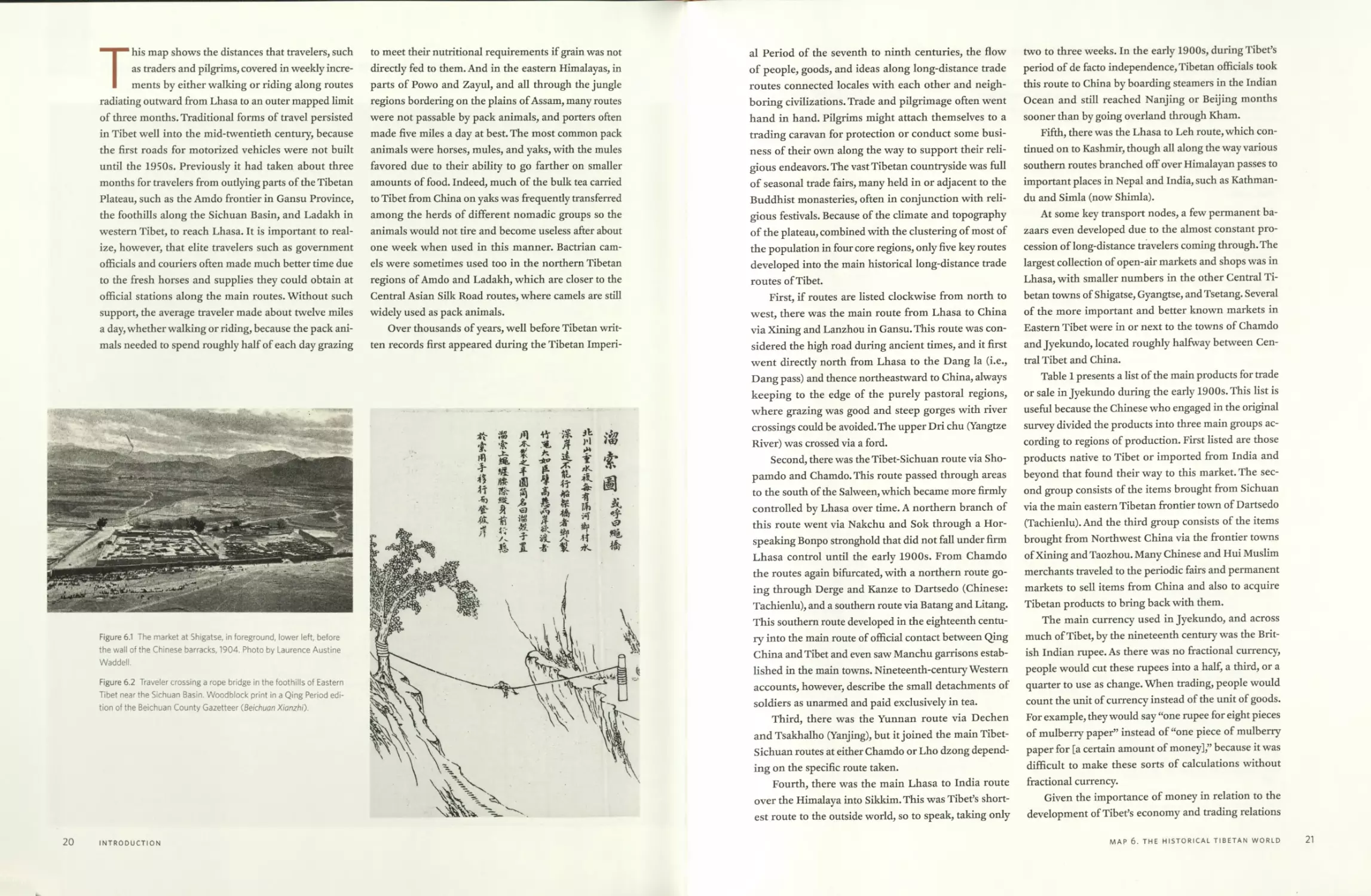

Figure 6.1 The market at Shigatse, in foreground, lower left, before

the wall of the Chinese barracks, 1904. Photo by Laurence Austine

Waddell.

Figure 6.2 Traveler crossing a rope bridge in the foothills of Eastern

Tibet near the Sichuan Basin. Woodblock print in a Qing Period edi-

tion of the Beichuan County Gazetteer (Beichuan Xianzhi).

20

INTRODUCTION

al Period of the seventh to ninth centuries, the flow

of people, goods, and ideas along long-distance trade

routes connected locales with each other and neigh-

boring civilizations. Trade and pilgrimage often went

hand in hand. Pilgrims might attach themselves to a

trading caravan for protection or conduct some busi-

ness of their own along the way to support their reli-

gious endeavors. The vast Tibetan countryside was full

of seasonal trade fairs, many held in or adjacent to the

Buddhist monasteries, often in conjunction with reli-

gious festivals. Because of the climate and topography

of the plateau, combined with the clustering of most of

the population in four core regions, only five key routes

developed into the main historical long-distance trade

routes of Tibet.

First, if routes are listed clockwise from north to

west, there was the main route from Lhasa to China

via Xining and Lanzhou in Gansu. This route was con-

sidered the high road during ancient times, and it first

went directly north from Lhasa to the Dang la (i.e.,

Dang pass) and thence northeastward to China, always

keeping to the edge of the purely pastoral regions,

where grazing was good and steep gorges with river

crossings could be avoided. The upper Dri chu (Yangtze

River) was crossed via a ford.

Second, there was the Tibet-Sichuan route via Sho-

pamdo and Chamdo. This route passed through areas

to the south of the Salween, which became more firmly

controlled by Lhasa over time. A northern branch of

this route went via Nakchu and Sok through a Hor-

speaking Bonpo stronghold that did not fall under firm

Lhasa control until the early 1900s. From Chamdo

the routes again bifurcated, with a northern route go-

ing through Derge and Kanze to Dartsedo (Chinese:

Tachienlu), and a southern route via Batang and Litang.

This southern route developed in the eighteenth centu-

ry into the main route of official contact between Qing

China and Tibet and even saw Manchu garrisons estab-

lished in the main towns. Nineteenth-century Western

accounts, however, describe the small detachments of

soldiers as unarmed and paid exclusively in tea.

Third, there was the Yunnan route via Dechen

and Tsakhalho (Yanjing), but it joined the main Tibet-

Sichuan routes at either Chamdo or Lho dzong depend-

ing on the specific route taken.

Fourth, there was the main Lhasa to India route

over the Himalaya into Sikkim. This was Tibet’s short-

est route to the outside world, so to speak, taking only

two to three weeks. In the early 1900s, during Tibet’s

period of de facto independence, Tibetan officials took

this route to China by boarding steamers in the Indian

Ocean and still reached Nanjing or Beijing months

sooner than by going overland through Kham.

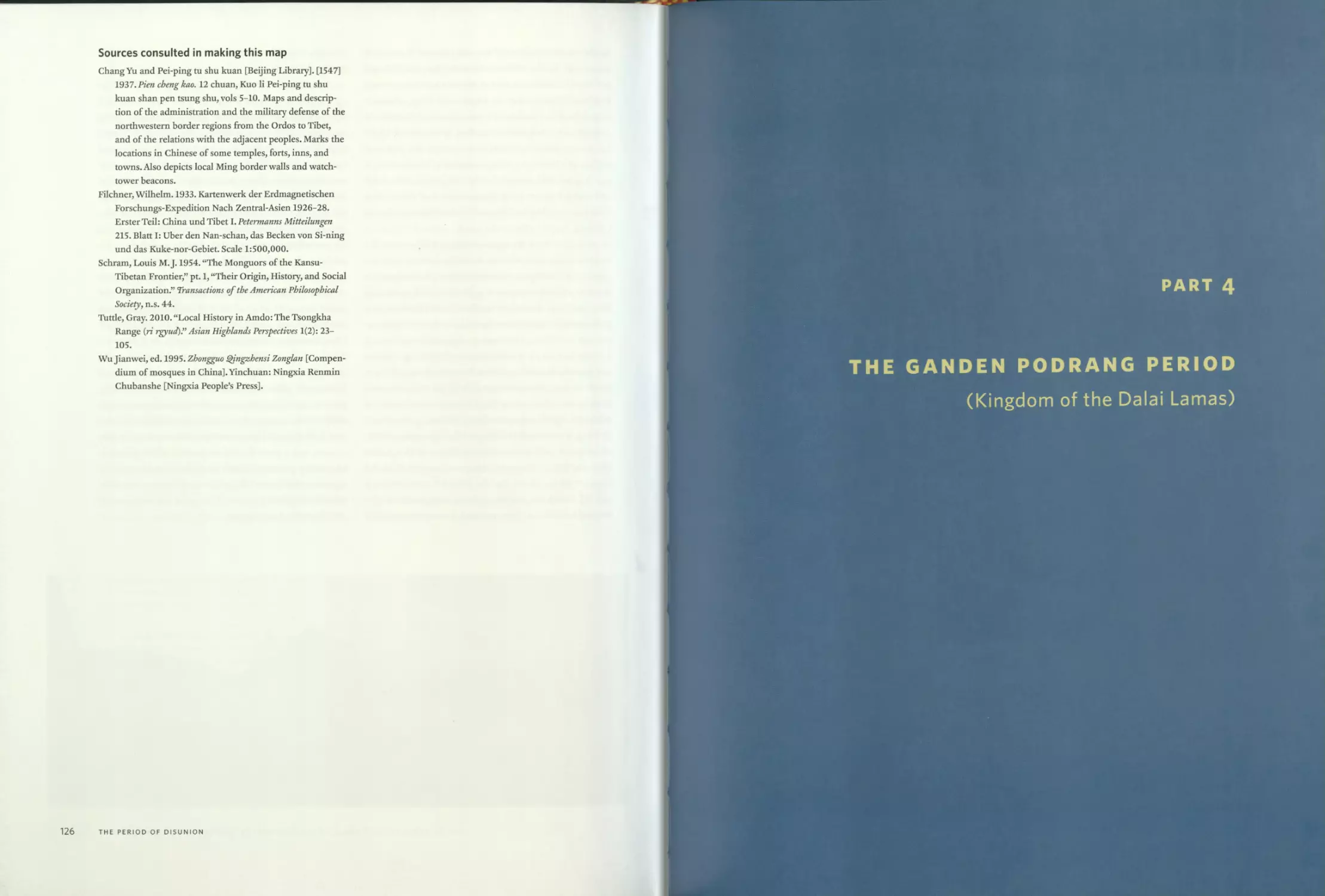

Fifth, there was the Lhasa to Leh route, which con-

tinued on to Kashmir, though all along the way various

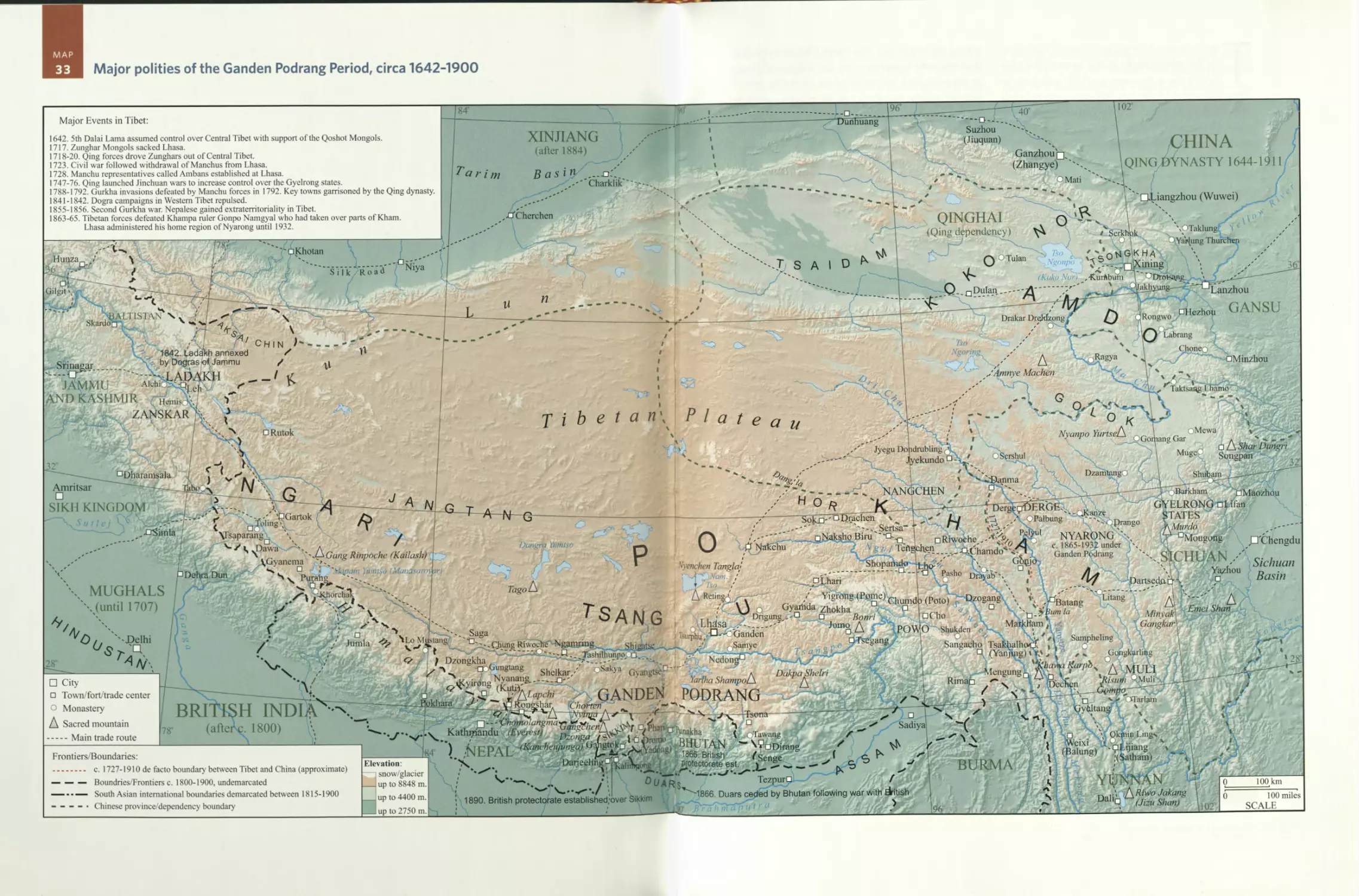

southern routes branched off over Himalayan passes to

important places in Nepal and India, such as Kathman-

du and Simla (now Shimla).

At some key transport nodes, a few permanent ba-

zaars even developed due to the almost constant pro-

cession of long-distance travelers coming through. The

largest collection of open-air markets and shops was in

Lhasa, with smaller numbers in the other Central Ti-

betan towns of Shigatse, Gyangtse, and Tsetang. Several

of the more important and better known markets in

Eastern Tibet were in or next to the towns of Chamdo

and Jyekundo, located roughly halfway between Cen-

tral Tibet and China.

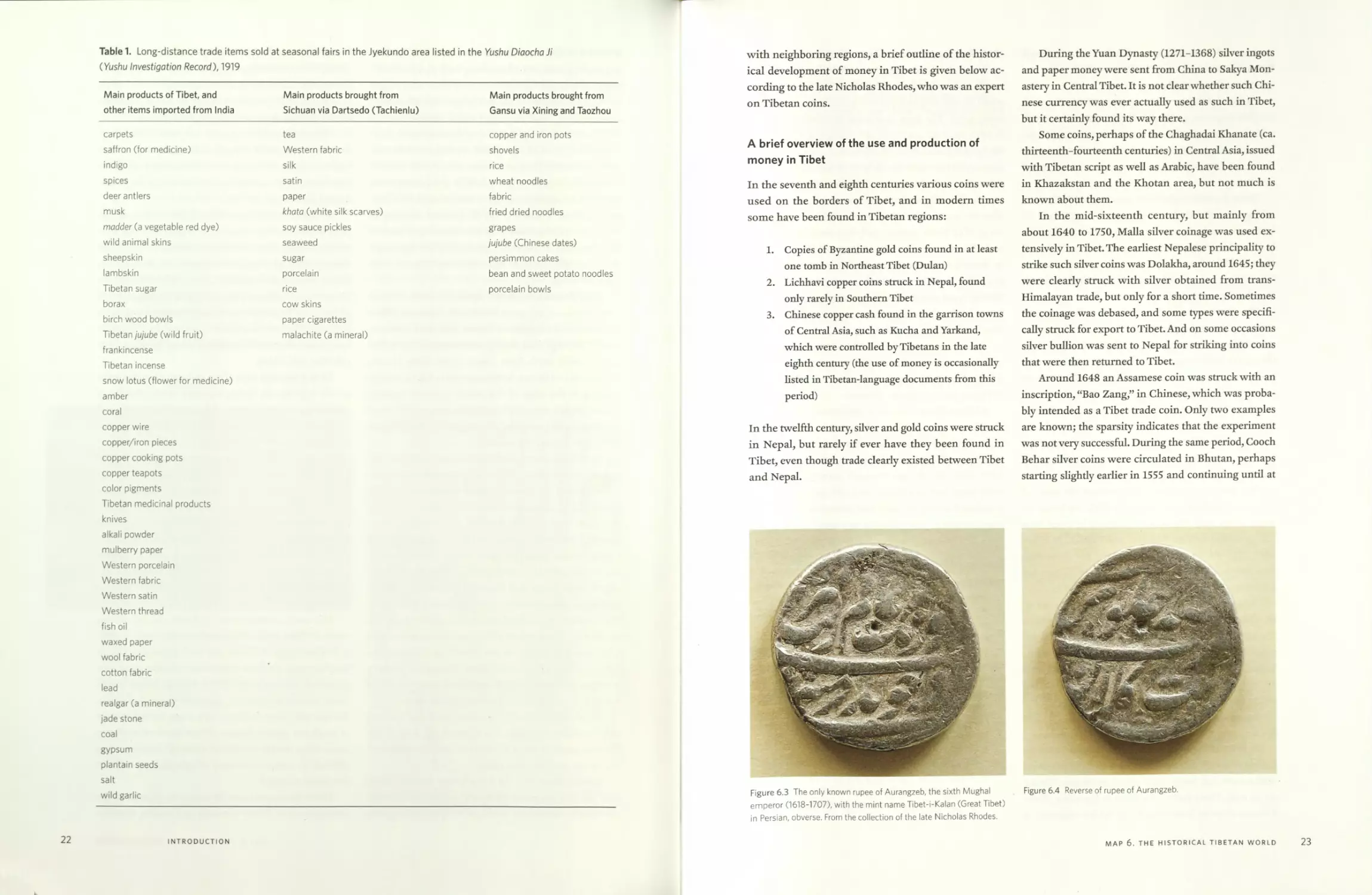

Table 1 presents a list of the main products for trade

or sale in Jyekundo during the early 1900s. This list is

useful because the Chinese who engaged in the original

survey divided the products into three main groups ac-

cording to regions of production. First listed are those

products native to Tibet or imported from India and

beyond that found their way to this market. The sec-

ond group consists of the items brought from Sichuan

via the main eastern Tibetan frontier town of Dartsedo

(Tachienlu). And the third group consists of the items

brought from Northwest China via the frontier towns

of Xining and Taozhou. Many Chinese and Hui Muslim

merchants traveled to the periodic fairs and permanent

markets to sell items from China and also to acquire

Tibetan products to bring back with them.

The main currency used in Jyekundo, and across

much of Tibet, by the nineteenth century was the Brit-

ish Indian rupee. As there was no fractional currency,

people would cut these rupees into a half, a third, or a

quarter to use as change. When trading, people would

count the unit of currency instead of the unit of goods.

For example, they would say “one rupee for eight pieces

of mulberry paper” instead of “one piece of mulberry

paper for [a certain amount of money],” because it was

difficult to make these sorts of calculations without

fractional currency.

Given the importance of money in relation to the

development of Tibet’s economy and trading relations

MAP 6. THE HISTORICAL TIBETAN WORLD

21

Table 1. Long-distance trade items sold at seasonal fairs in the Jyekundo area listed in the Yushu Diaocha Ji

(Yushu Investigation Record), 1919

Main products of Tibet, and Main products brought from Main products brought from

other items imported from India Sichuan via Dartsedo (Tachienlu) Gansu via Xining and Taozhou

carpets tea copper and iron pots

saffron (for medicine) Western fabric shovels

indigo silk rice

spices satin wheat noodles

deer antlers paper fabric

musk khata (white silk scarves) fried dried noodles

madder (a vegetable red dye) soy sauce pickles grapes

wild animal skins seaweed jujube (Chinese dates)

sheepskin sugar persimmon cakes

lambskin porcelain bean and sweet potato noodles

Tibetan sugar rice porcelain bowls

borax cow skins

birch wood bowls paper cigarettes

Tibetan jujube (wild fruit) malachite (a mineral)

frankincense

Tibetan incense

snow lotus (flower for medicine)

amber

coral

copper wire

copper/iron pieces

copper cooking pots

copper teapots

color pigments

Tibetan medicinal products

knives

alkali powder

mulberry paper

Western porcelain

Western fabric

Western satin

Western thread

fish oil

waxed paper

wool fabric

cotton fabric

lead

realgar (a mineral)

jade stone

coal

gypsum

plantain seeds

salt

wild garlic

22

INTRODUCTION

with neighboring regions, a brief outline of the histor-

ical development of money in Tibet is given below ac-

cording to the late Nicholas Rhodes, who was an expert

on Tibetan coins.

A brief overview of the use and production of

money in Tibet

In the seventh and eighth centuries various coins were

used on the borders of Tibet, and in modern times

some have been found in Tibetan regions:

1. Copies of Byzantine gold coins found in at least

one tomb in Northeast Tibet (Dulan)

2. Lichhavi copper coins struck in Nepal, found

only rarely in Southern Tibet

3. Chinese copper cash found in the garrison towns

of Central Asia, such as Kucha and Yarkand,

which were controlled by Tibetans in the late

eighth century (the use of money is occasionally

listed in Tibetan-language documents from this

period)

In the twelfth century, silver and gold coins were struck

in Nepal, but rarely if ever have they been found in

Tibet, even though trade clearly existed between Tibet

and Nepal.

During the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) silver ingots

and paper money were sent from China to Sakya Mon-

astery in Central Tibet. It is not clear whether such Chi-

nese currency was ever actually used as such in Tibet,

but it certainly found its way there.

Some coins, perhaps of the Chaghadai Khanate (ca.

thirteenth-fourteenth centuries) in Central Asia, issued

with Tibetan script as well as Arabic, have been found

in Khazakstan and the Khotan area, but not much is

known about them.

In the mid-sixteenth century, but mainly from

about 1640 to 1750, Malla silver coinage was used ex-

tensively in Tibet. The earliest Nepalese principality to

strike such silver coins was Dolakha, around 1645; they

were clearly struck with silver obtained from trans-

Himalayan trade, but only for a short time. Sometimes

the coinage was debased, and some types were specifi-

cally struck for export to Tibet. And on some occasions

silver bullion was sent to Nepal for striking into coins

that were then returned to Tibet.

Around 1648 an Assamese coin was struck with an

inscription, “Bao Zang,” in Chinese, which was proba-

bly intended as a Tibet trade coin. Only two examples

are known; the sparsity indicates that the experiment

was not very successful. During the same period, Cooch

Behar silver coins were circulated in Bhutan, perhaps

starting slightly earlier in 1555 and continuing until at

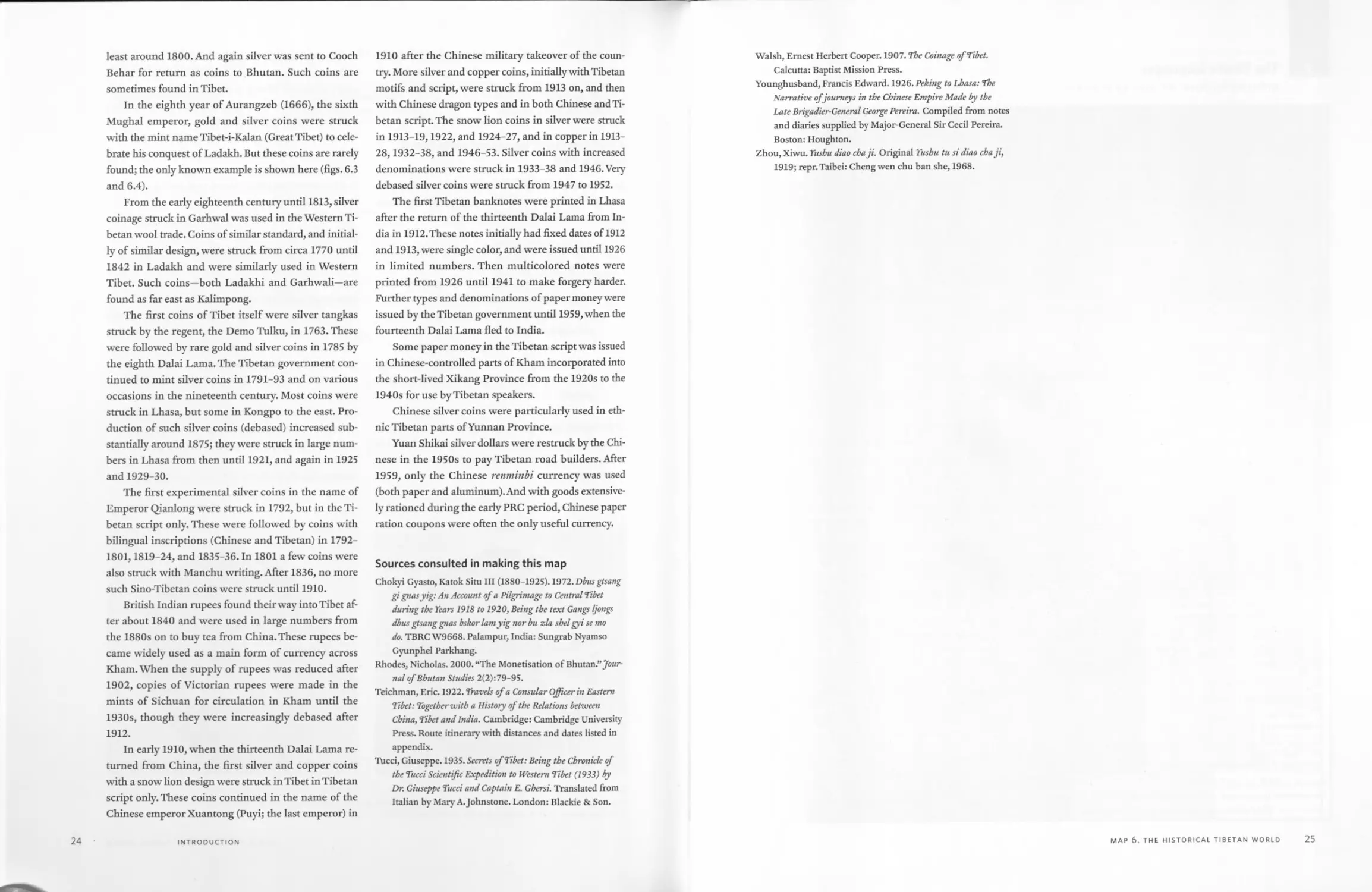

Figure 6.4 Reverse of rupee of Aurangzeb.

Figure 6.3 The only known rupee of Aurangzeb, the sixth Mughal

emperor (1618-1707), with the mint name Tibet-i-Kalan (Great Tibet)

in Persian, obverse. From the collection of the late Nicholas Rhodes.

MAP 6. THE HISTORICAL TIBETAN WORLD

23

least around 1800. And again silver was sent to Cooch

Behar for return as coins to Bhutan. Such coins are

sometimes found in Tibet.

In the eighth year of Aurangzeb (1666), the sixth

Mughal emperor, gold and silver coins were struck

with the mint name Tibet-i-Kalan (Great Tibet) to cele-

brate his conquest of Ladakh. But these coins are rarely

found; the only known example is shown here (figs. 6.3

and 6.4).

From the early eighteenth century until 1813, silver

coinage struck in Garhwal was used in the Western Ti-

betan wool trade. Coins of similar standard, and initial-

ly of similar design, were struck from circa 1770 until

1842 in Ladakh and were similarly used in Western

Tibet. Such coins—both Ladakhi and Garhwali—are

found as far east as Kalimpong.

The first coins of Tibet itself were silver tangkas

struck by the regent, the Demo Tulku, in 1763. These

were followed by rare gold and silver coins in 1785 by

the eighth Dalai Lama. The Tibetan government con-

tinued to mint silver coins in 1791-93 and on various

occasions in the nineteenth century. Most coins were

struck in Lhasa, but some in Kongpo to the east. Pro-

duction of such silver coins (debased) increased sub-

stantially around 1875; they were struck in large num-

bers in Lhasa from then until 1921, and again in 1925

and 1929-30.

The first experimental silver coins in the name of

Emperor Qianlong were struck in 1792, but in the Ti-

betan script only. These were followed by coins with

bilingual inscriptions (Chinese and Tibetan) in 1792-

1801,1819-24, and 1835-36. In 1801 a few coins were

also struck with Manchu writing. After 1836, no more

such Sino-Tibetan coins were struck until 1910.

British Indian rupees found their way into Tibet af-

ter about 1840 and were used in large numbers from

the 1880s on to buy tea from China. These rupees be-

came widely used as a main form of currency across

Kham. When the supply of rupees was reduced after

1902, copies of Victorian rupees were made in the

mints of Sichuan for circulation in Kham until the

1930s, though they were increasingly debased after

1912.

In early 1910, when the thirteenth Dalai Lama re-

turned from China, the first silver and copper coins

with a snow lion design were struck in Tibet in Tibetan

script only. These coins continued in the name of the

Chinese emperor Xuantong (Puyi; the last emperor) in

1910 after the Chinese military takeover of the coun-

try. More silver and copper coins, initially with Tibetan

motifs and script, were struck from 1913 on, and then

with Chinese dragon types and in both Chinese and Ti-

betan script. The snow lion coins in silver were struck

in 1913-19,1922, and 1924-27, and in copper in 1913-

28,1932-38, and 1946-53. Silver coins with increased

denominations were struck in 1933-38 and 1946. Very

debased silver coins were struck from 1947 to 1952.

The first Tibetan banknotes were printed in Lhasa

after the return of the thirteenth Dalai Lama from In-

dia in 1912. These notes initially had fixed dates of 1912

and 1913, were single color, and were issued until 1926

in limited numbers. Then multicolored notes were

printed from 1926 until 1941 to make forgery harder.

Further types and denominations of paper money were

issued by the Tibetan government until 1959, when the

fourteenth Dalai Lama fled to India.

Some paper money in the Tibetan script was issued

in Chinese-controlled parts of Kham incorporated into

the short-lived Xikang Province from the 1920s to the

1940s for use by Tibetan speakers.

Chinese silver coins were particularly used in eth-

nic Tibetan parts of Yunnan Province.

Yuan Shikai silver dollars were restruck by the Chi-

nese in the 1950s to pay Tibetan road builders. After

1959, only the Chinese renminbi currency was used

(both paper and aluminum). And with goods extensive-

ly rationed during the early PRC period, Chinese paper

ration coupons were often the only useful currency.

Sources consulted in making this map

Chokyi Gyasto, Katok Situ III (1880-1925). Y372.Dbus gtsang

gi gnasyig: An Account of a Pilgrimage to Central Tibet

during the Years 1918 to 1920, Being the text Gangs Ijongs

dbus gtsang gnas bskorlamyig norbu zla shel gyi se mo

do. TBRC W9668. Palampur, India: Sungrab Nyamso

Gyunphel Parkhang.

Rhodes, Nicholas. 2000. “The Monetisation of Bhutan.” Jour-

nal of Bhutan Studies 2(2):79-95.

Teichman, Eric. 1922. Travels of a Consular Officer in Eastern

Tibet: Together with a History of the Relations between

China, Tibet and India. Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press. Route itinerary with distances and dates listed in

appendix.

Tucci, Giuseppe. 1935. Secrets of Tibet: Being the Chronicle of

the Tucci Scientific Expedition to Western Tibet (1933) by

Dr. Giuseppe Tucci and Captain E. Ghersi. Translated from

Italian by Mary A. Johnstone. London: Blackie & Son.

24

INTRODUCTION

Walsh, Ernest Herbert Cooper. 1907. The Coinage of Tibet.

Calcutta: Baptist Mission Press.

Younghusband, Francis Edward. 1926. Peking to Lhasa: The

Narrative of journeys in the Chinese Empire Made by the

Late Brigadier-General George Pereira. Compiled from notes

and diaries supplied by Major-General Sir Cecil Pereira.

Boston: Houghton.

Zhou, Xiwu. Yusbu diao cha ji. Original Yushu tu si diao cha ji,

1919; repr.Taibei: Cheng wen chu ban she, 1968.

MAP 6. THE HISTORICAL TIBETAN WORLD

25

MAP

7

The Tibetic languages

NICOLAS TOURNADRE AND KARL RYAVEC

□ Kashgar

Yarkand

iCherchen

inmg

Niya

Rebl

ZAN'

iOLOK

32 PA К

I Gar

Laste

KANI

KHYUNGPtP

Tsanda

Nakchu

RONGDRAK

Nyagrongi

:ham

Xjangkars

PHENPQ

KONGPO

Unci

CHAKTREI

6

KathmanduD

DUR

Chomblapt

(Everest)

Dartsedoq

MINYAK'

О Mao Xi An

xtion

Gangchen Dzonga \

(Kanchenjunga} z

( DHROMCL

' SHARKHOK -v

Zungchu BAIMA /

ZHONGU

YUSHU \ „

□ \ z- П -

JyekundoSershul

Amnve MachenA

s ______ □

Machen

BATANG \n

° A* MTANG

M,nx j,

□Dunhuang

96°

ч *>ч «^hangyeQ

TAJIKISTAN

XINJIANG

North-Eastern section

AFG.

Themchel

Khotan

; 3£

Lanzhou

lagormo

Min Xian

KH<

aRutok

South-Eastern section

Boundary in Dispute

TIBET\AUTONOMOUS REGION

HOR BACHEN

HOR NAKCHU

Shim la

□ Chengdu

INDIA

HU AN

Syenchen Thanglfa —

Shan

Central section

\UTTAR PRADESH

BIHAR

_>Tsetang

LHOKHA

□Nyima

Dangra Yumtso

Political Boundaries (circa 2000):

—" “ — International (both de jure and de facto)

----------Chinese Province/Autonom. Region, Indian State

--------Approximate Boundaries of

Geolinguistic Sections

These boundaries, some overlapping, also

indicate the extents of those languages that

cover large areas in China (i.e. U-Tsang, Amdo,

Hor and Kham). Dialects are mapped in these

three main regions.

A* Pockets of Amdo spoken

K* Pockets of Kham spoken

□ Large City

□ Small City/Town

Language data according to:

The Tibetic Languages

by Nicolas Toumadre and Hiroyuki Suzuki

r □

Jiuquan

QINGHAI

" □

--Dulan

y* VHUMLA’K

7 J oxPOLPa

k .. Junila \

“<щф-Western section-"x

102° INNER MONGOLIA У

. AUTONOMOUS REGION f

r ?/ / i ‘

lung/-3 i

)j£PE / jVQ _____ -«W- JUL»

Thimf MERA ‘ Z

DZONGKHaJC^’*'--------

bh ('ГГ\ л

Southern section ASSAM

11 <^zSadiya\

LHOKE f^rjcciing'

L /)/WEST BENI

>rN!NGXIA

Lhari PEMBAR

□

0 100 miles

SCALE

Purane

AND У? I

f CHINA

IWuwei Xх

A Kailash , —,

) Марат ftimtso (Maniisciro ar)

TO NGARI

^AU^Yr^bpyGCHU

:org^

\

nJ

0 Tso jL

Ngonpol

BANAKq TSONI

Chabcha^-,. -

\

□Gertse |

K2-

ГGANSU

UiPrSig 1 S 4

у n

Charklik

Elevation:

snow/glacier

---up to 8848 m.

---up to 4400 m.

---up to 2750 m.

100 km

.'Slp<N

iSkardux BALTI

' N »*' \ I * X *1

\North-Western section 7

rT ?>?SHAMSKAi: 1 I

~\PURIK ladakhi/'^j

LMiaagU.

О ^purikn^adake

- flaJ.

SKARI ,

HMIRNh

Padum IУ

KEI

^**i~~<©hai£1ba7>LAHULI

□ Amritsar\ Н1МАСНЛ1 \

• PRADESH \

PUNJAB

4KZ.UINLVMVI N • Gvclt;

KHAM

к ЛГ1 UK \ Balling

zNDDelnal)un

> HARYANA.'"

Hunza \

' O ^/5

-- Northern J

GileitXn- Areas---U

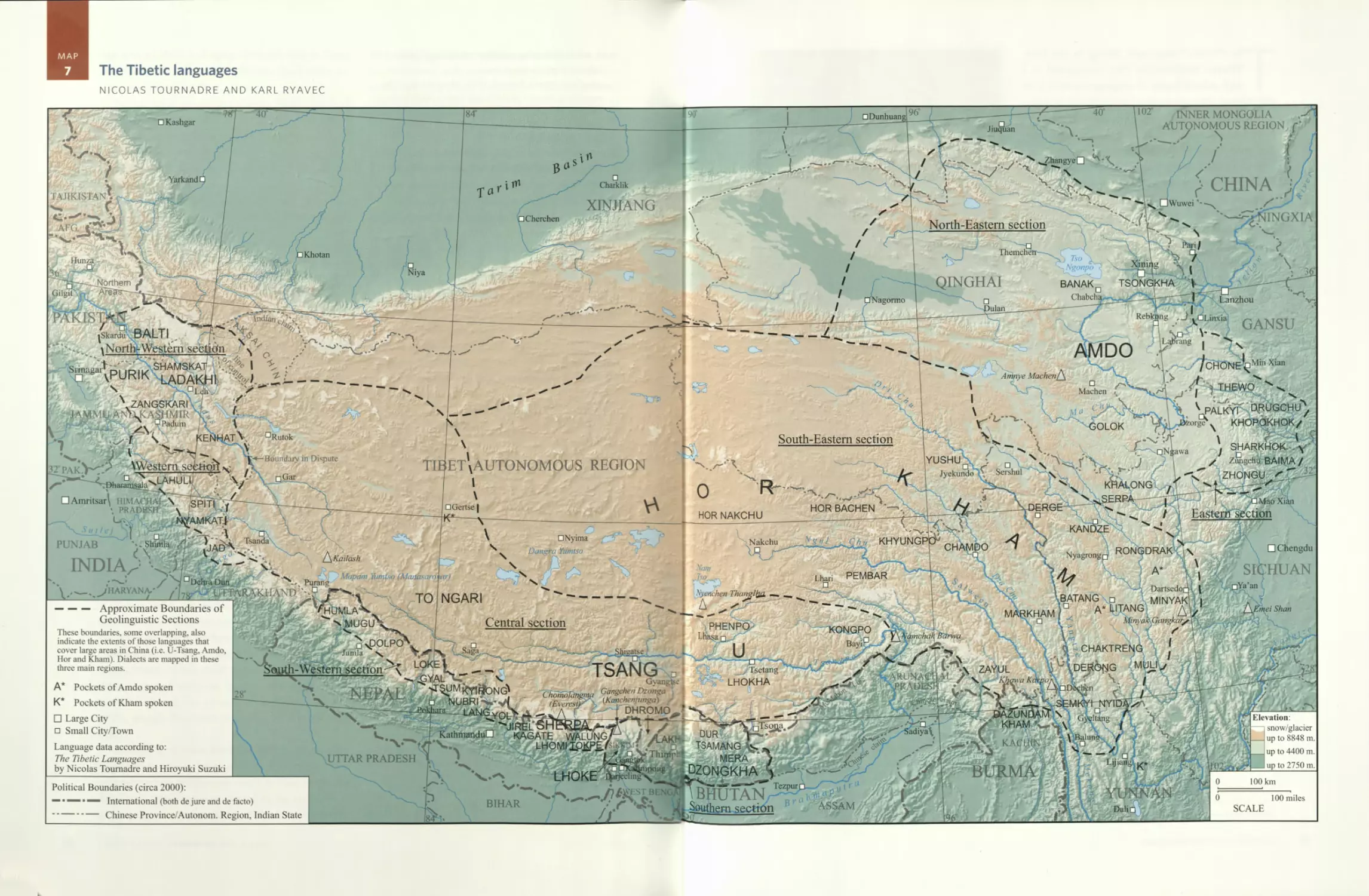

The “Tibetic” languages belong to the Sino-

Tibetan macrofamily. They correspond to a

well-defined family of languages derived from

Old Tibetan, although in some rare cases such as Baima

or Khalong, a Qiangic substratum is a very probable

hypothesis. The language called Old Tibetan was spo-

ken at the time of the Tibetan Empire (seventh to ninth

centuries). Old Tibetan is very similar to the classical

literary language, which has preserved a very archaic

orthography. And indeed, all the modern languages not

only have regular reflexes of Classical Literary Tibetan

but also share a core vocabulary and grammar.

The Tibetic linguistic family is comparable in size

and diversity to the Romance and Germanic families.

The diversity is due to many factors—geographic, soci-

olinguistic, religious, and political.

The Tibetic family includes languages from five

countries—China, Pakistan, India, Bhutan, and Nepal.

Additionally, Sangdam, a Khams dialect, is spoken in

the Kachin state of Myanmar (Burma). The total num-

ber of Tibetic-language speakers is roughly six million;

this figure is approximate since there is no precise and

reliable census.

Figure 7.1 The Tibetan minister Thonmi Sambhota

’ Thon mi sam b+ho ta), credited by tradition with inventing

the Tibetan alphabet in the seventh century. Circa seventeenth-

century mural in the Potala Palace in Lhasa.

Table 2. The Tibetic Languages

China U-Tsang Khams (няя-^ ), Hor Amdo Kyirong -я^), Zhongu (г^я^Х Khalong gSerpa Zitsadegu dPalskyid / Chos-rje Sharkhok (^^), Thewo (§^5), Chone Drugchu Baima (г^-^-я^-).

Pakistan Balti (qan^^)2

India Purik and Ladakhi («ту^'я^'Х Zangskari Spiti and Lahuli or Gharsha (ир^-я^•), Nyamkat (^яя^) and Jad or Dzad Drengjong language often locally called Lhoke (^5 ).

Nepal Humla Mugu (^-oyrg^X Dolpo (^ч-гй-яруХ Loke or Mustang Nubri (^q-aS^X Tsum (^я-g^), Langtang (weqifiX Yolmo Gyalsumdo Jirel (e ^я^), Sherpa (^-«йя^-) also locally called Sharwi Tamnye (/рй-чр?я-^-Х Kagate also called Shupa Цчучйя^-Х Lhomi (^айя^), Walung (<ц-д^5<;-»(-яй-я^-^я-ц-дс-я|^), and Tokpe Gola

Bhutan Dzongkha (gt-я ), Tsamang (ужц-) or Ch’ocha-ngacha Lakha (<ч-гч) also called Tshangkha (afc^X Dur Brokkat also called Bjokha in Dzongkha, Mera Sakteng Brokpa-ke

1. Sun (2003) uses Chos-rje, but according to Suzuki (p.c.), dPalskyid is better suited to refer to a group of four dialects that include Chos-rje.

2. Balti is traditionally written sbal-ti in Tibetan, but Balti people write it and pronounce it bal-ti.

28

INTRODUCTION

Table 2 lists nearly fifty Tibetic languages, all de-

rived from Old Tibetan. The dialects and varieties cer-

tainly number more than two hundred. The languages

listed can be grouped together at a higher level into

eight major sections, which appear on the map: North-

Western, Western, Central, South-Western, Southern,

South-Eastern, Eastern, and North-Eastern. Each sec-

tion constitutes a geolinguistic continuum.

The data presented here will appear in a forthcom-

ing book, The Tibetic Languages, by Nicolas Tournadre

and Hiroyuki Suzuki (with the collaboration of Kon-

chok Gyatso and Xavier Becker).

The classification reflected in the map is essentially

based on a genetic approach, but it also includes geo-

graphical parameters, migration, and language contact

factors. Non-Tibetic languages such as Gyalrongic,

Qiangic, Mongolic, Turkic, Chinese, et cetera do not

appear on the map.

MAP 7. THE TIBETIC LANGUAGES

29

MAP

8

How to use this atlas: Map coverage and cartographic conventions

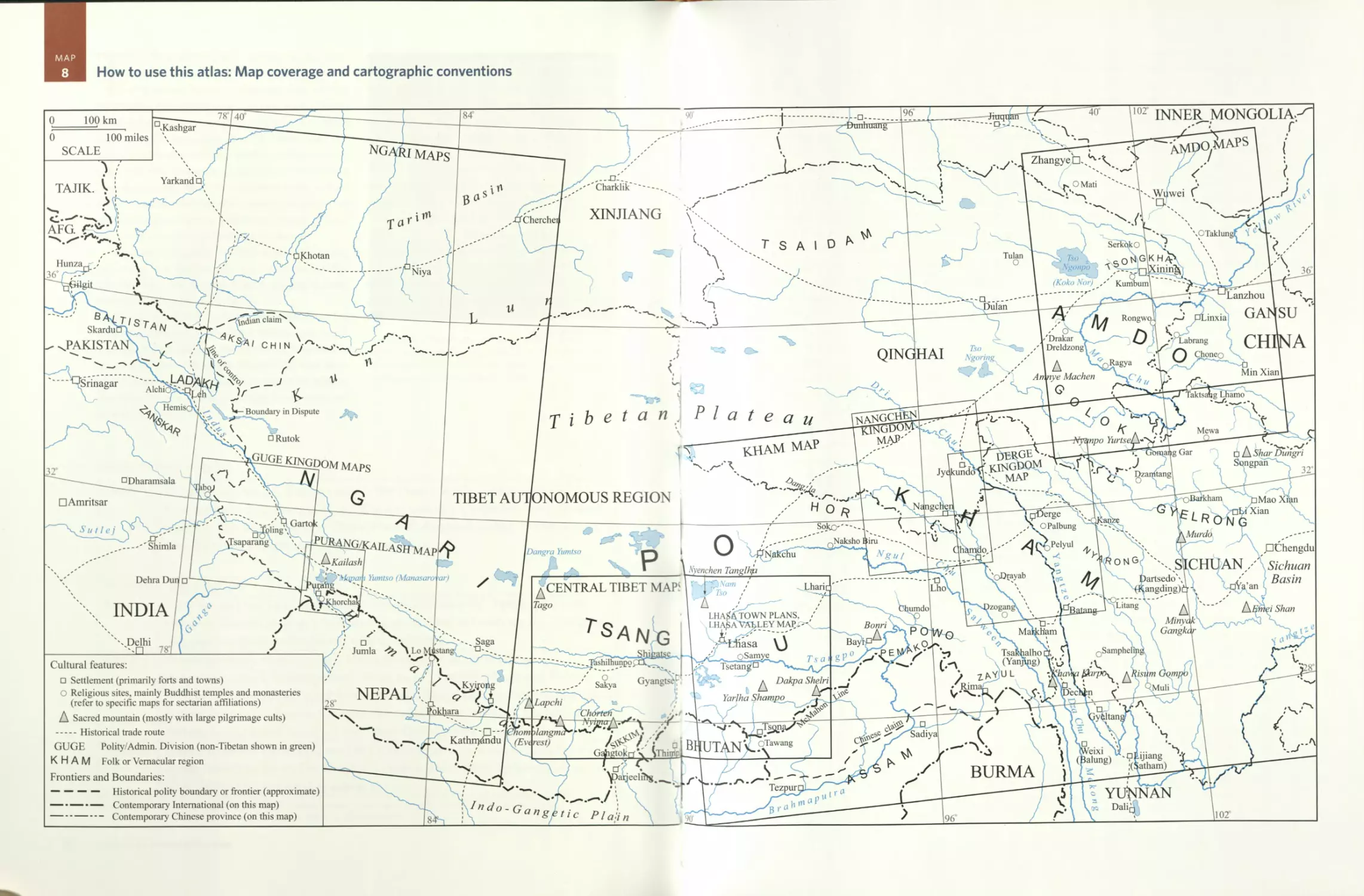

A series of standardized cartographic symbols

and fonts are used in this atlas (refer to this

map’s legend), such as circles for religious

sites and set ranges of colored elevation zones, so that

historical, social, and cultural patterns can be made

as clear as possible across the maps. This map itself

presents the way the entire Tibetan culture region is

depicted on the main historical period maps through-

out this atlas. Also shown are the map footprints of the

regional-scale maps of Tibet’s four macroregions of

Ngari, U-Tsang (Central Tibet), Kham, and Amdo, in-

cluded after each main historical period’s introduction.

In addition, some area maps are included of the west-

ern Tibetan kingdoms of Guge and Purang, the city of

Lhasa and the Lhasa Valley, and the eastern Tibetan

kingdoms of Derge and Nangchen. Not depicted on

this map are some additional maps showing the main

historical diffusions of Tibetan Buddhism across Mon-

golia and North China as far as Siberia, as well as some

detailed maps of sites in the old walled city of Beijing

and surrounding areas.

Fortunately, owing to my academic training in

applying geographic information science to research

problems in the humanities and social sciences, I pos-

sessed sufficient skills to make all of the digital maps

needed for this atlas project. The foundational data for

representing physical terrain derive from a global 1 km

resolution digital elevation model (DEM) developed

during the 1990s by the US Geological Survey. I used

these data to depict a specific set of colored elevation

zones on most maps, including a rich green for Tibet’s

lowland bordering regions and a lighter green up to

4,400 m to show the approximate limits of cultivation

above the agrarian valleys where most of Tibet’s popu-

lation still lives. Above this, the vast and wholly pasto-

ral zone is shown in an earthy orange hue. For repre-

senting terrain on the regional-scale U-Tsang map and

some of the more detailed area maps, I used available

90 m resolution NASA Shuttle Radar Topography Mis-

sion (SRTM) data. The original SRTM data was actually

created at a higher resolution of 30 m and then inten-

tionally downgraded to 90 m for non-US territories and

possessions. Glaciers and snowfields are based on the

Global Land Ice Measurements from Space (GLIMS)

Glacier Database created by the National Snow and

Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colorado. Major rivers and

lakes were edited from global hydrography data pro-

vided in the US government’s 1992 Digital Chart of the

World (DCW).

Tibetan cultural and religious sites shown in this

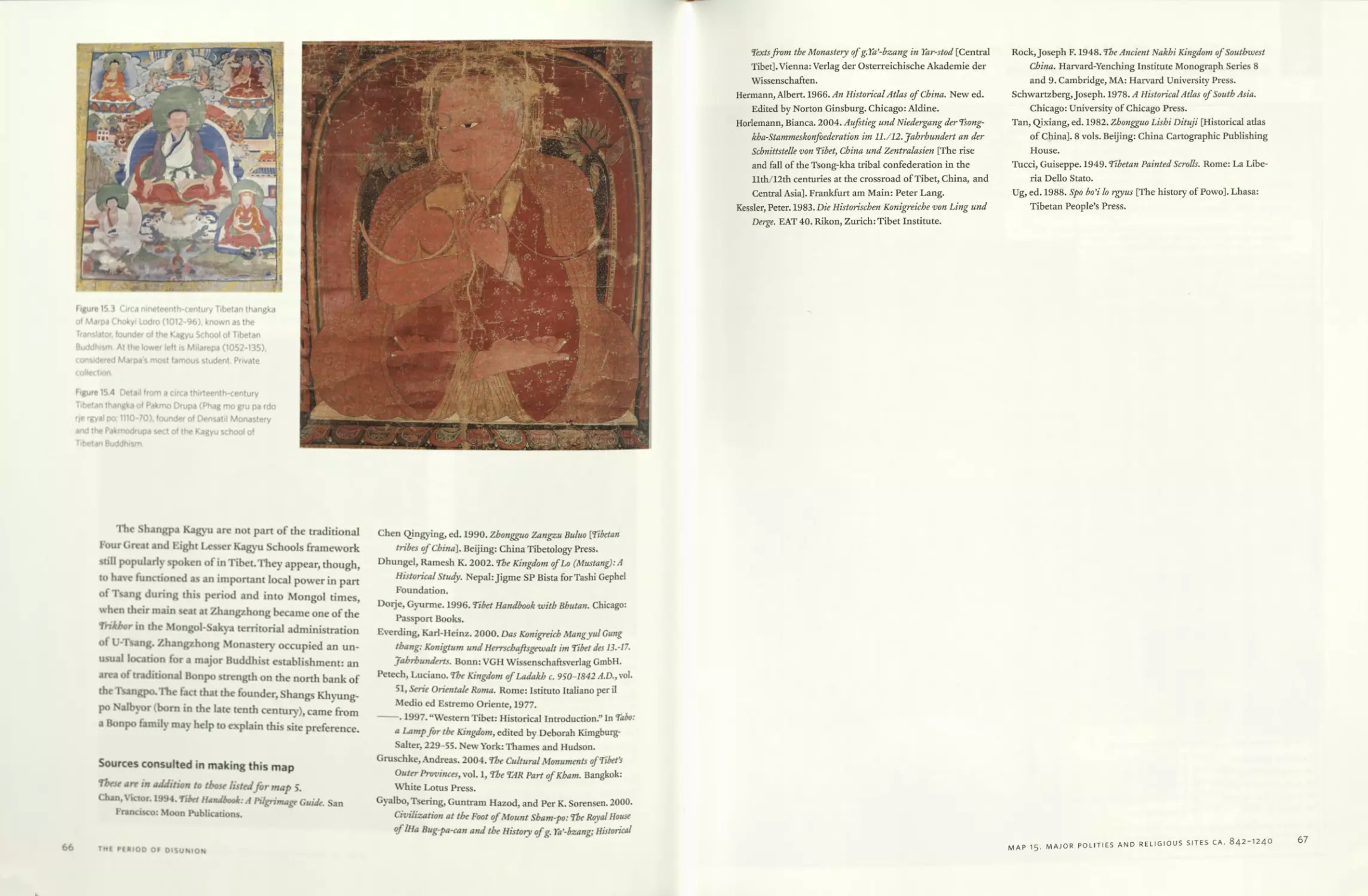

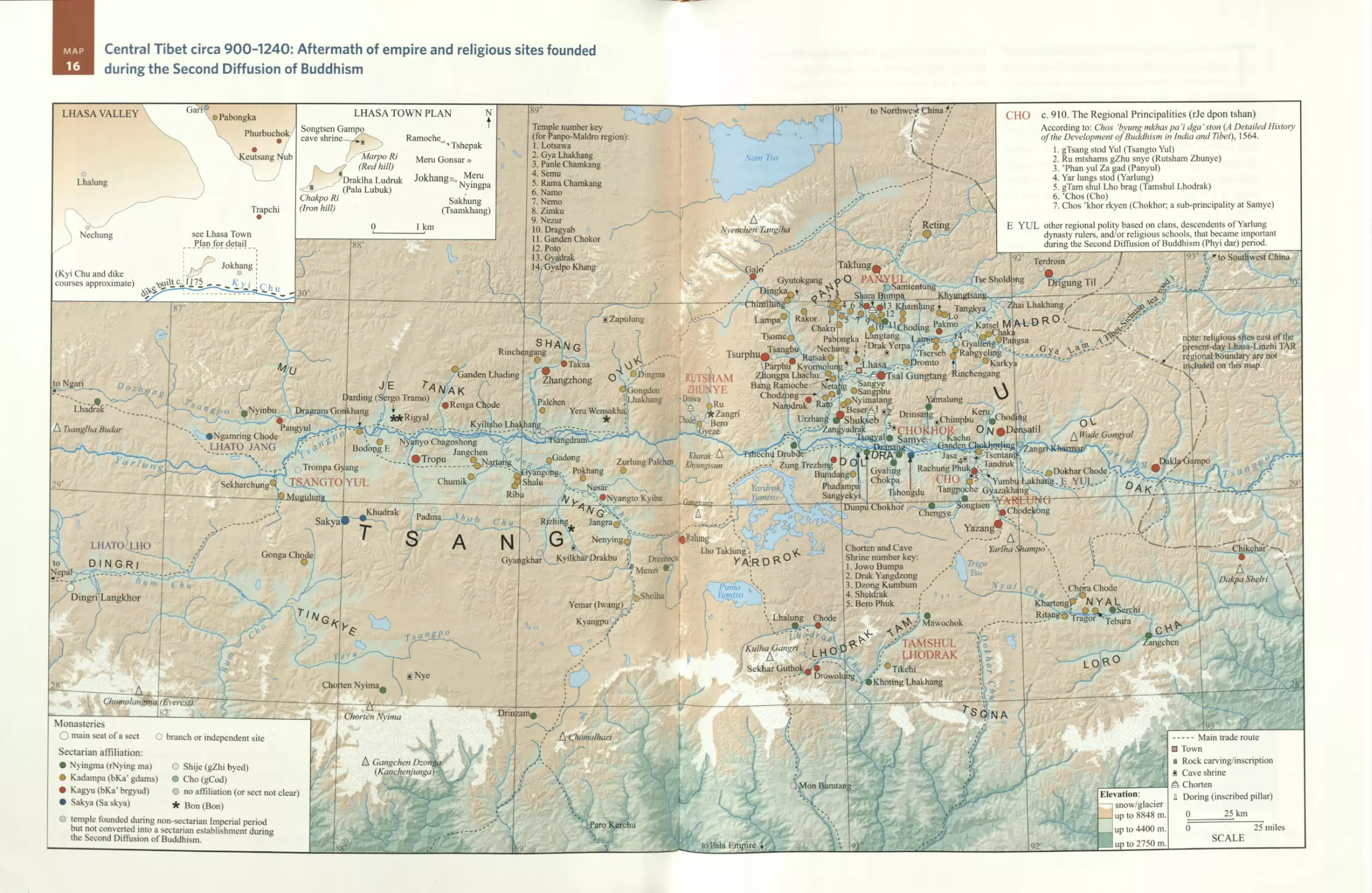

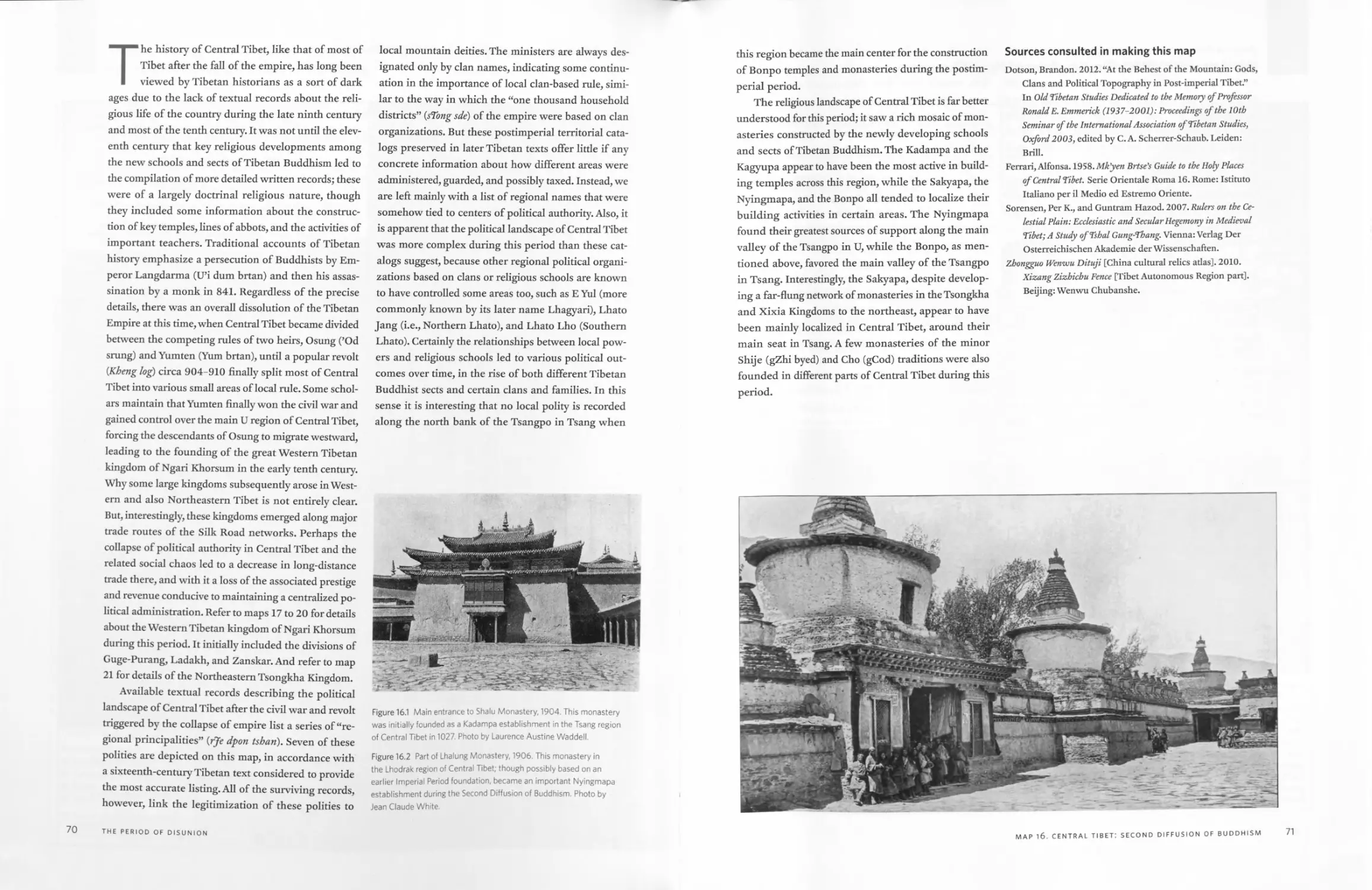

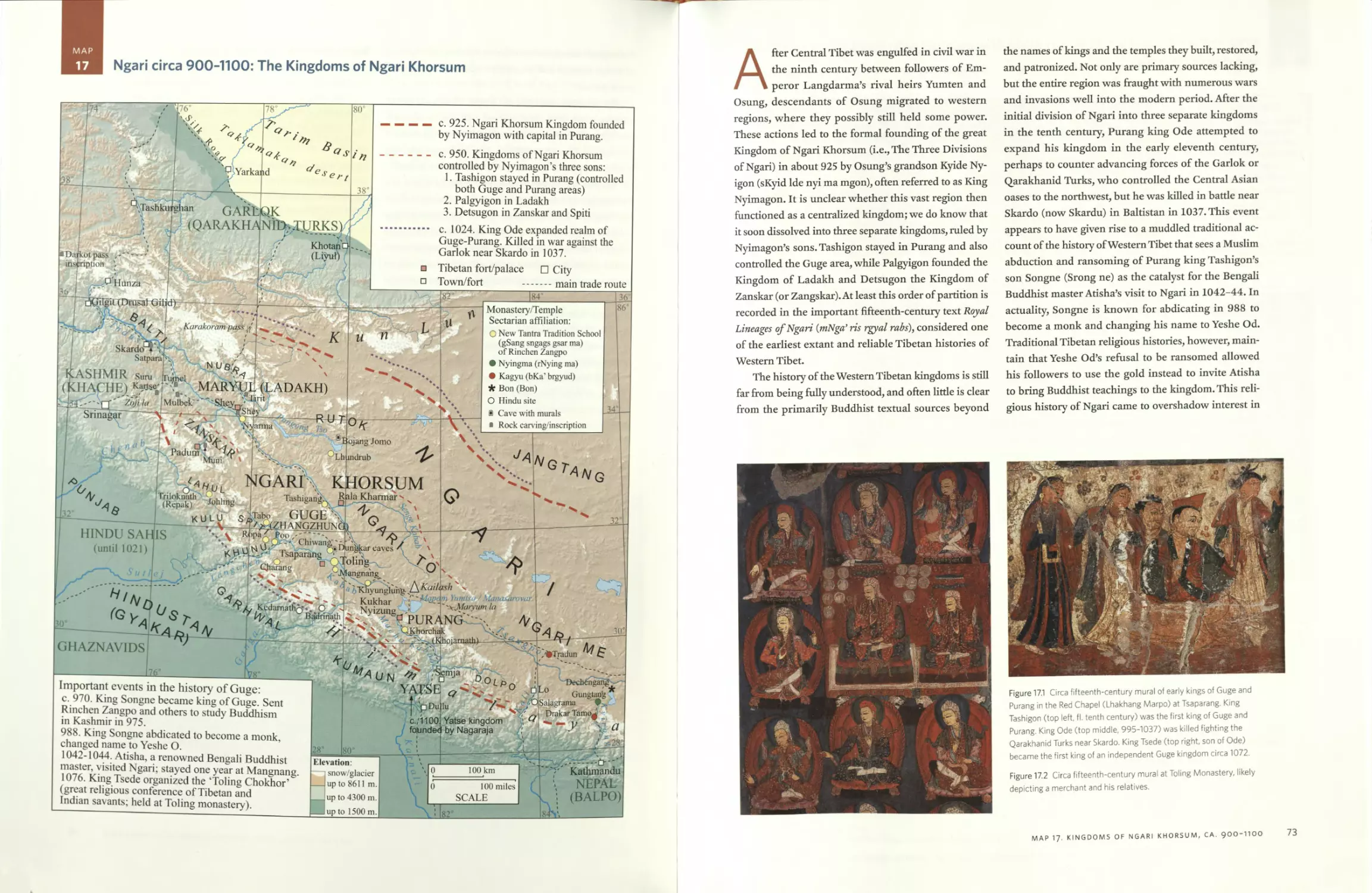

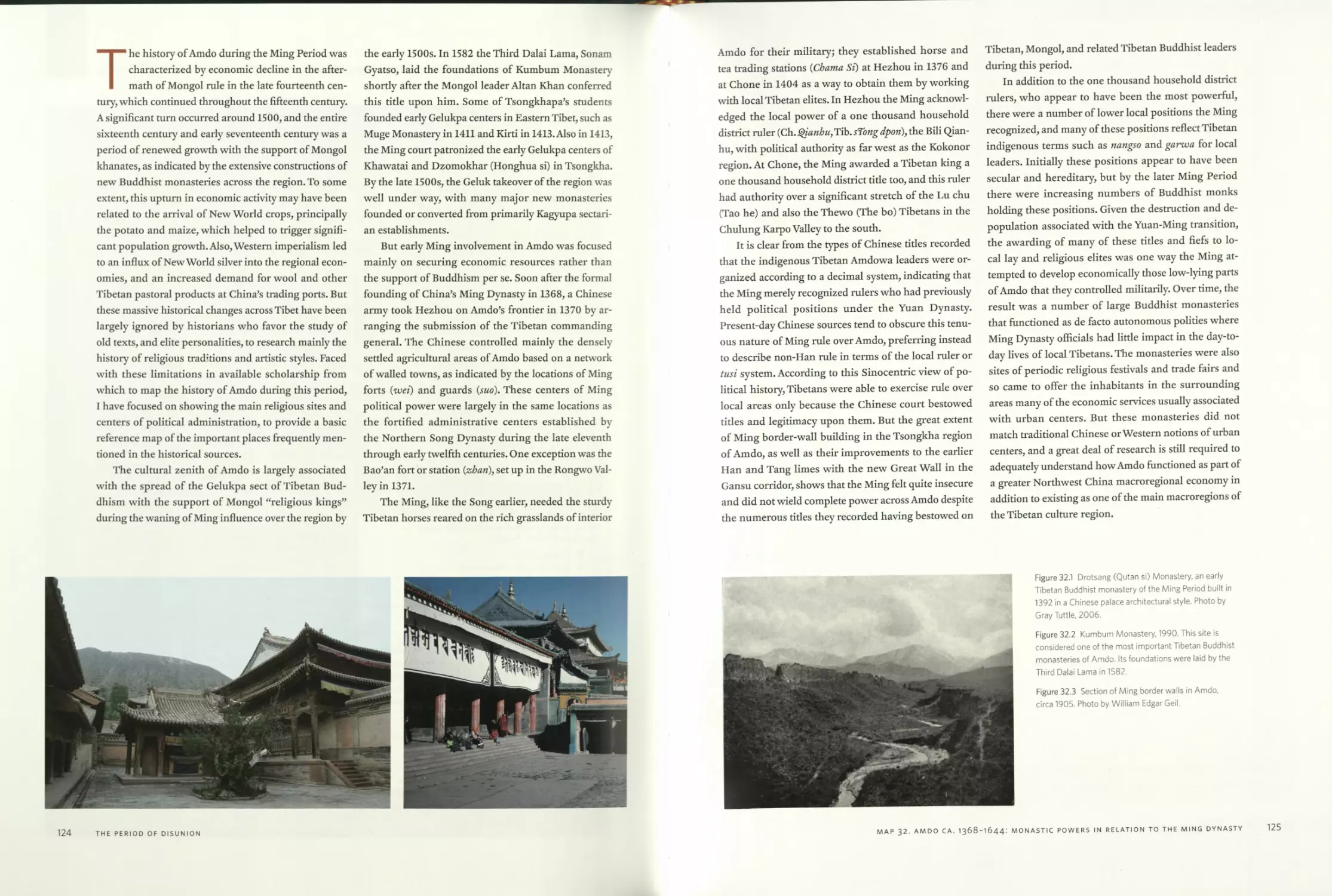

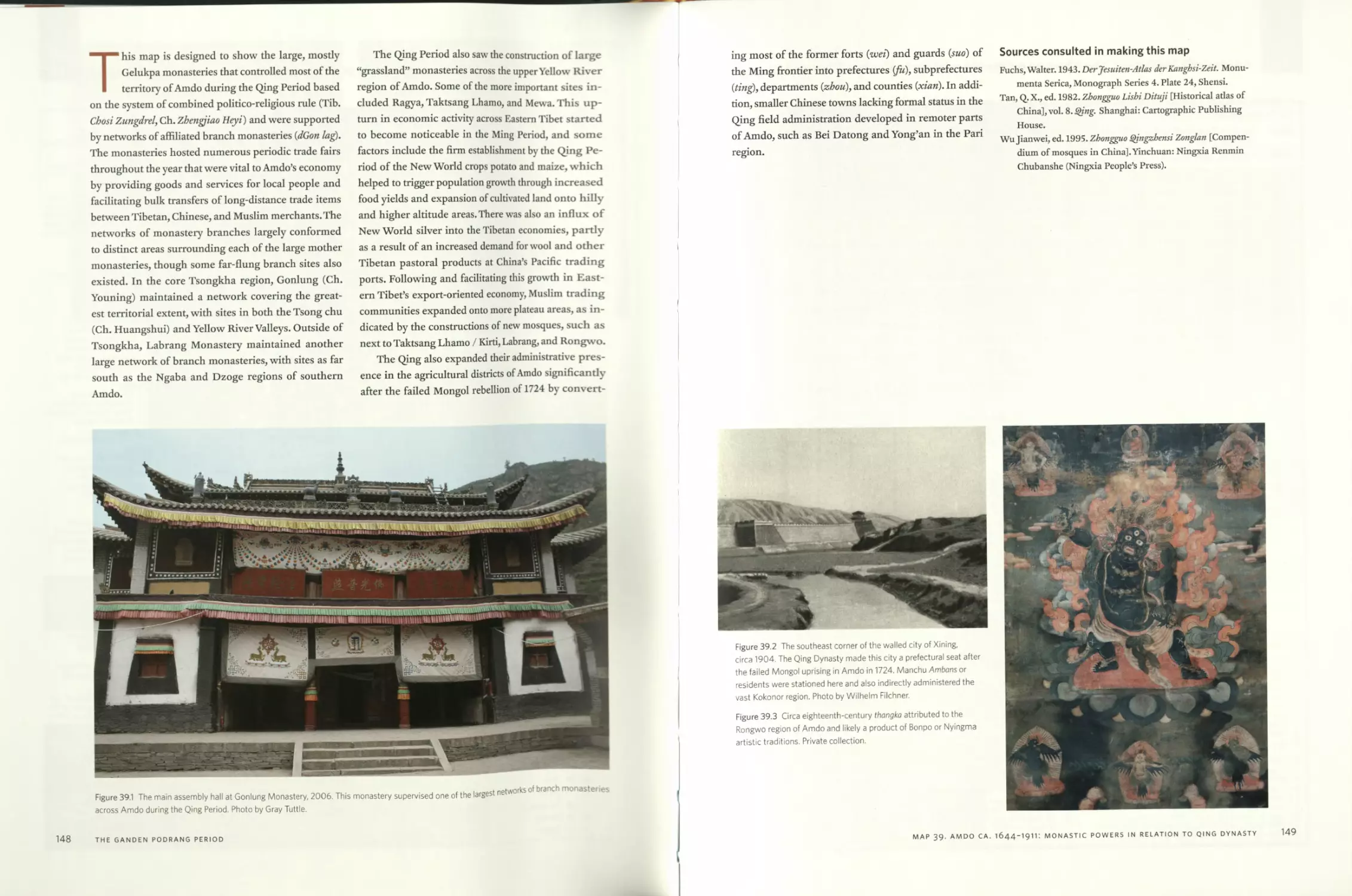

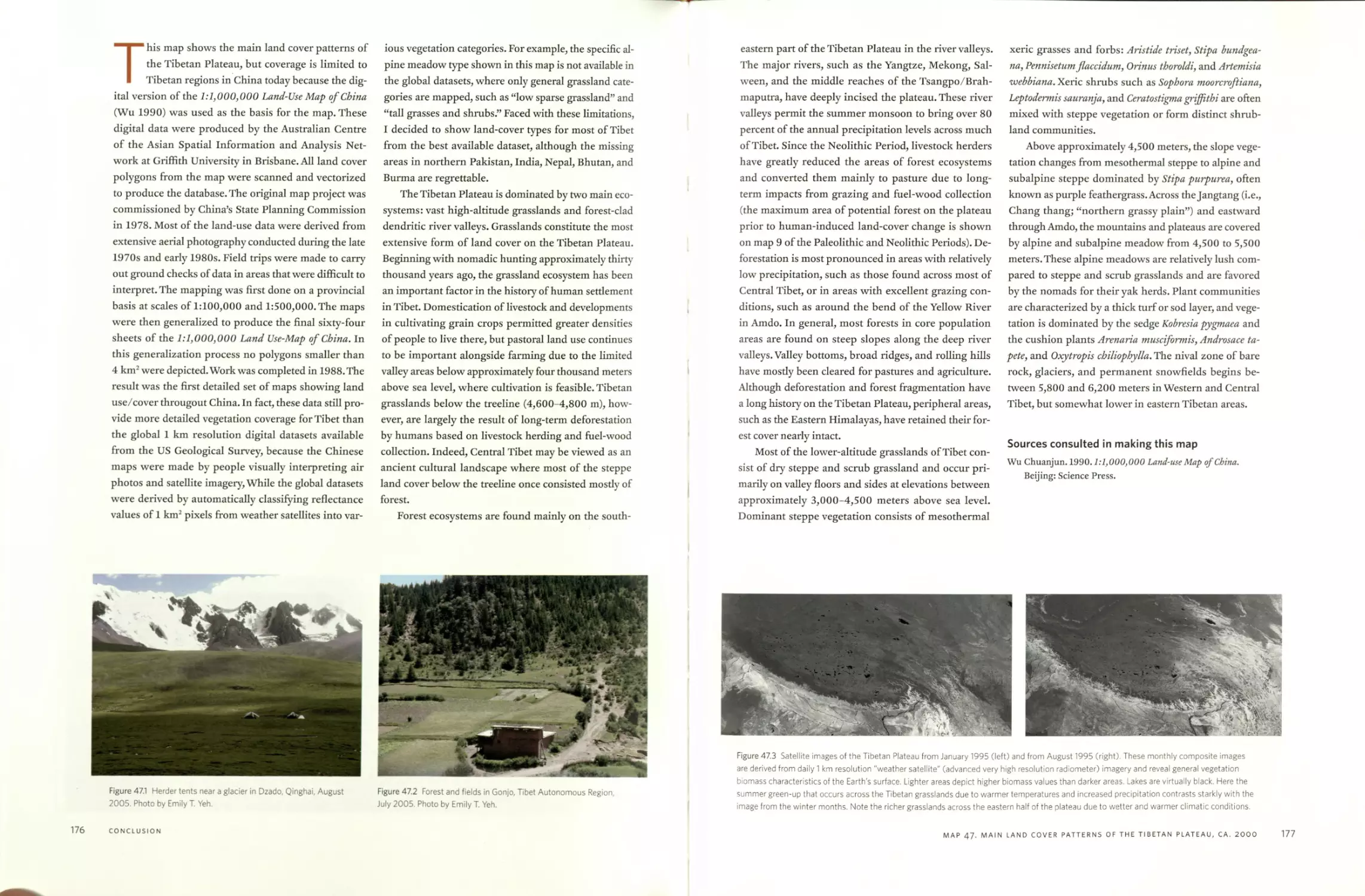

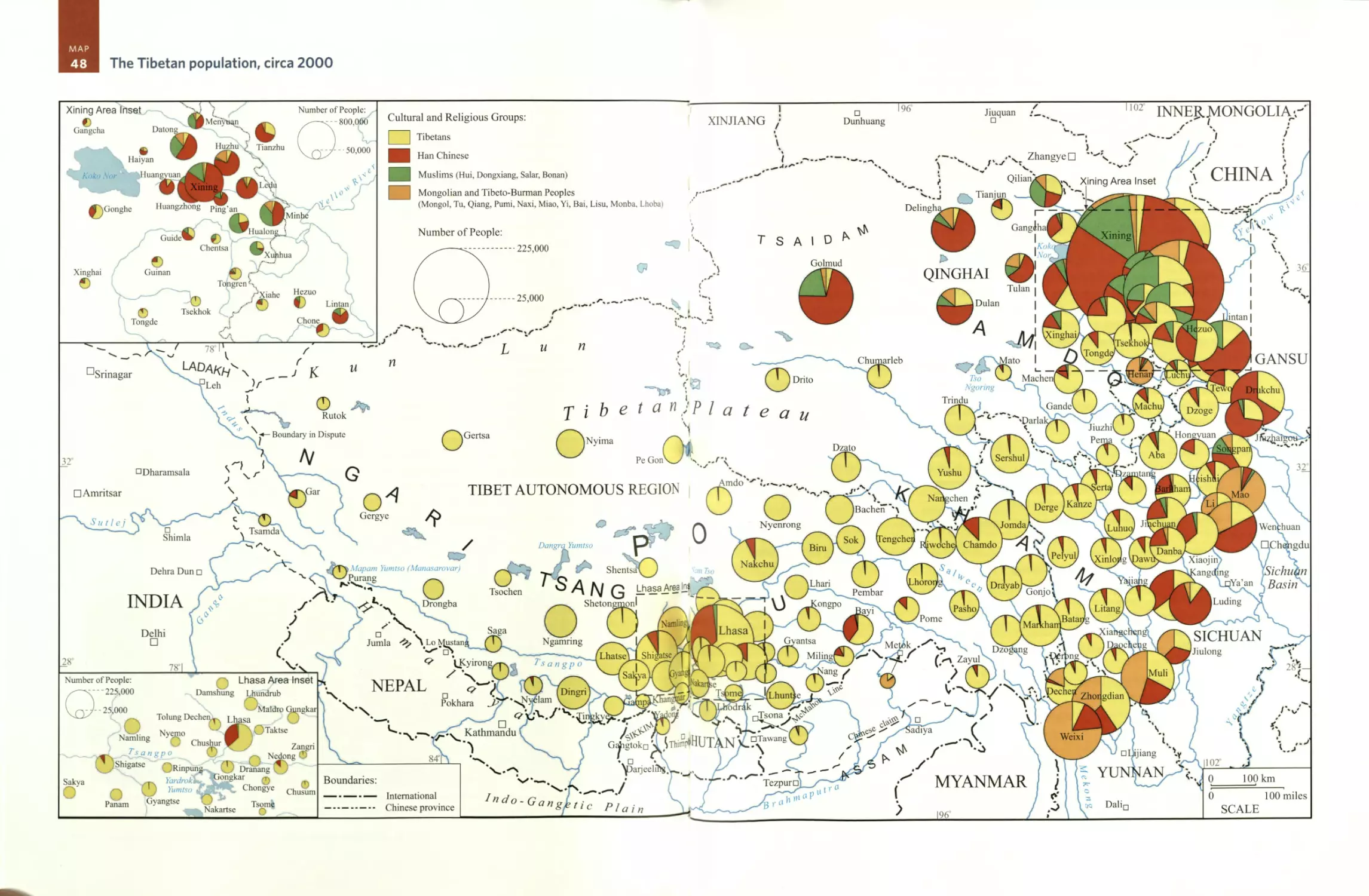

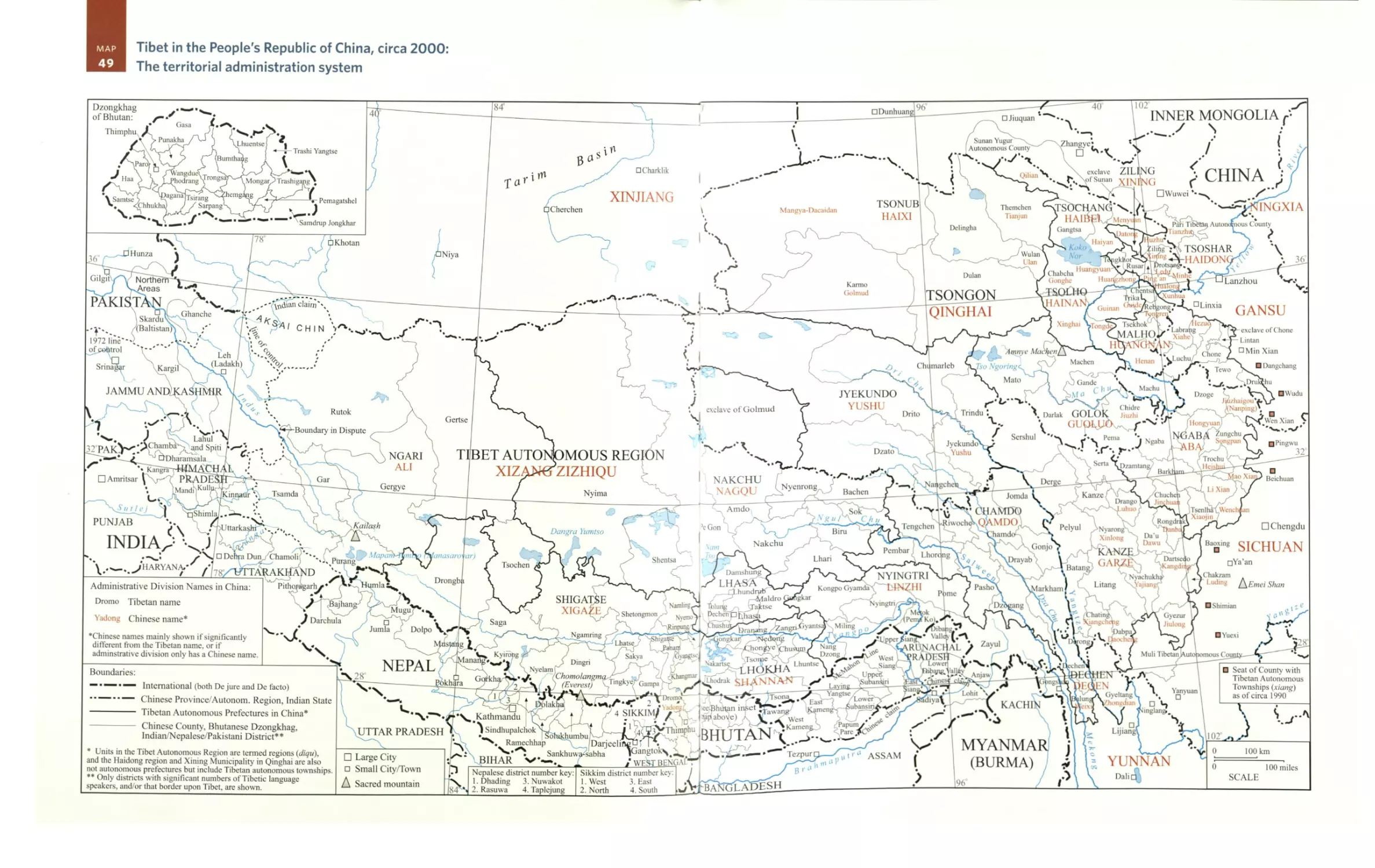

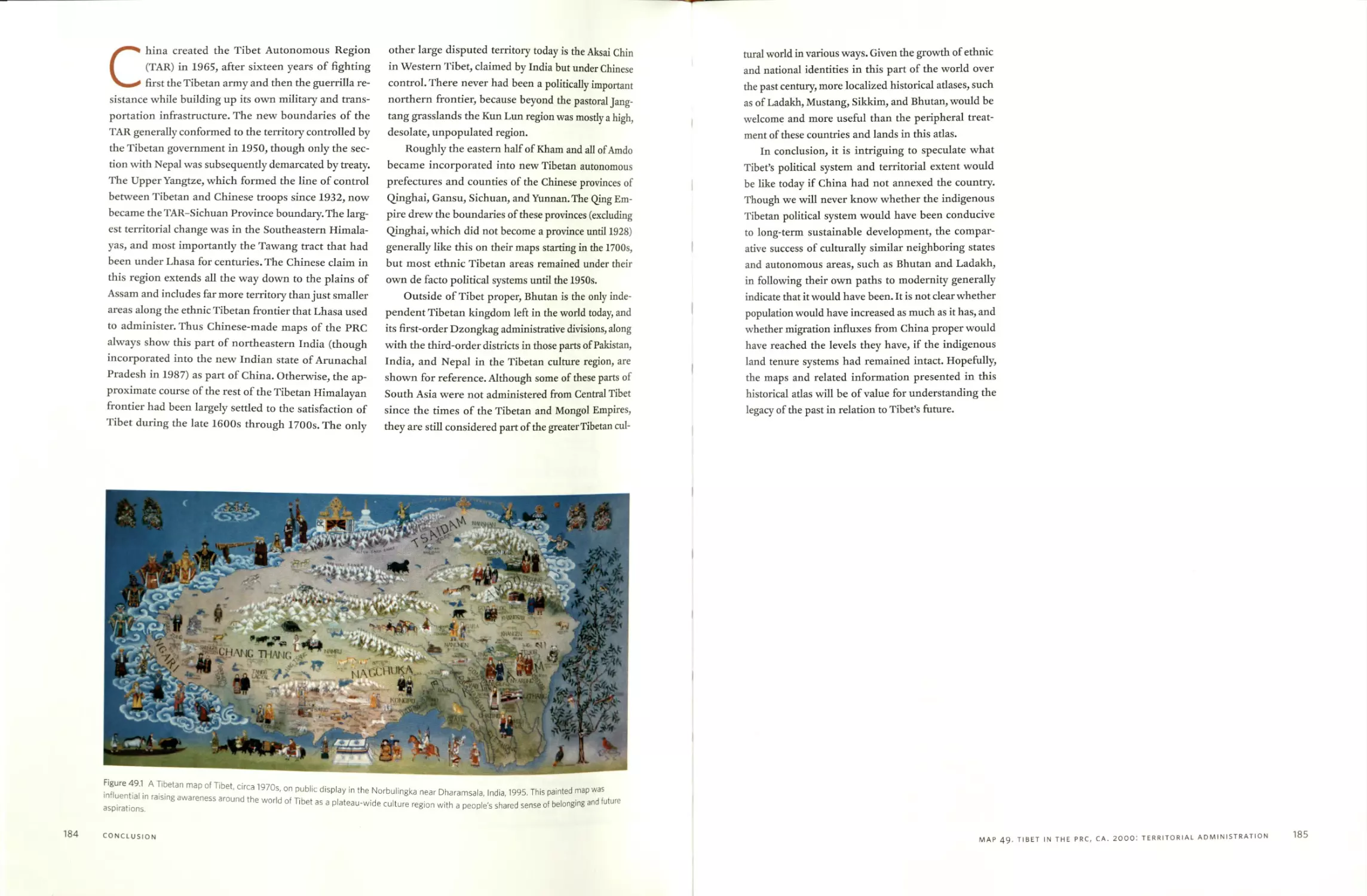

atlas mostly derive from various spatial databases that