Текст

By tllC same author

(,'apitalz:rm and the Historians

The ConstitutiOTl of Liberl:J1

The Pure Theory of Capital

The Senso1J' Order: An Inquiry into the

Foundations of Theoretical Ps.,'Pchology

The Road to Serfdom

{;,,'ttll.dle.

in Philosophy, Politics and Econom.ics

Lau'j Legislation and Liher

V'olume I R_ules and Order

V oinme 2 1-'he l\11irage of Social Justice

V 01 II U H

.\

rhe Political Order of a Free Society (Jorthcomi"fJ)

F. A. Hayek

NEW STUDIES

in Philosophy) Politics,

Economics and the

History of Ideas

c::

.....

r-

rn

C

"

,."

':'

I " .

First published 1978

by Routledge & Kegan PauJ plc

Reprinted in 1982

First published as a paperback in 1985

Reprinted hy Routledge, 1990

1] Ne\v Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE

'. : 1978 F.A. Hayek

Set in Baskerville 11 on 12pt

and printed in Great Britain by

TJ IJ ress (Padstovv) l..td, Padstow, Cornwall

AU rights reserved, No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic",

lnechanical, or other means no,,, known or hereafter invented,

including photocopying and recording, Of in any information

storage or retrieval syslcn1, \vithout pern1ission in ,vriting from

the publishers,

British Library Catalogu1',lg 1'11 Pu.blication Data

Hayek, Friedrich August

Ne\v studies in phi]o ophy, politics,

econon1ics and the history of ideas

I. Social sciences

I. Title

300 ' . 1 I-161

ISBN Q-415-05883-X

Contents

Preface

1) a-rt One

Pl11LOSC)Plly"

C1lapter 1

Chaptet 2

G?UlPter ..,

G 1 ltapter 4

Chapter 5

1'}lC F,rrors of Constructivisn1.

l'lle Prctenec of Knowledge

rI11e Primacy of the Abstract

Two Types of Mind

Tilc Atavism of Social Justice

Part r wo

p()Llrl'ICS

,..

VII

3

23

2:;

;:),,",,

5°

57

Ch pte'T 6' The Confusion of 1..aJ1guagc in Political TlloUght 7 1

Chapter 7 '1'he ( onstitutioIl of a Liberal State g8

Chapter 8 j":conotnic Frecdorn and Reprcserltativc

Governtnent 105

GYhapter 9 Llberalisrn I 19

G'hapter 10 vVhither Democracy? 152

Part Three

ECONOMICS

Chapter I I Three Elucidations of the Ricardo Effect

Cfhapter J 2 Competition as a Discovery Procedure

G T haptel' 13 rl'hc C alnpaign ...Against Keynesian Inflation

I Inflation's path to unemployrnent

2 Inflat\on, tl1c Inisdirection of labour, and

unemployn1ent

3 Furt11er consideratio!lS on the same topic

4- Caloice in curre11cy: a "\-vay to stop in.llatiol1

(;hftpl( , 1.1 'I"he C\V (knlliu;ion ,l\bout 'Plannin '

Iv]

I6

..)

179

19 1

Iq

""

I !)7

2 « } )

[H

,) Il'

.', J.....

(:hn/",., I fj

,,'11"1'11''- 1 b'

(/IJI1JJter '7

C1lapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Postscript

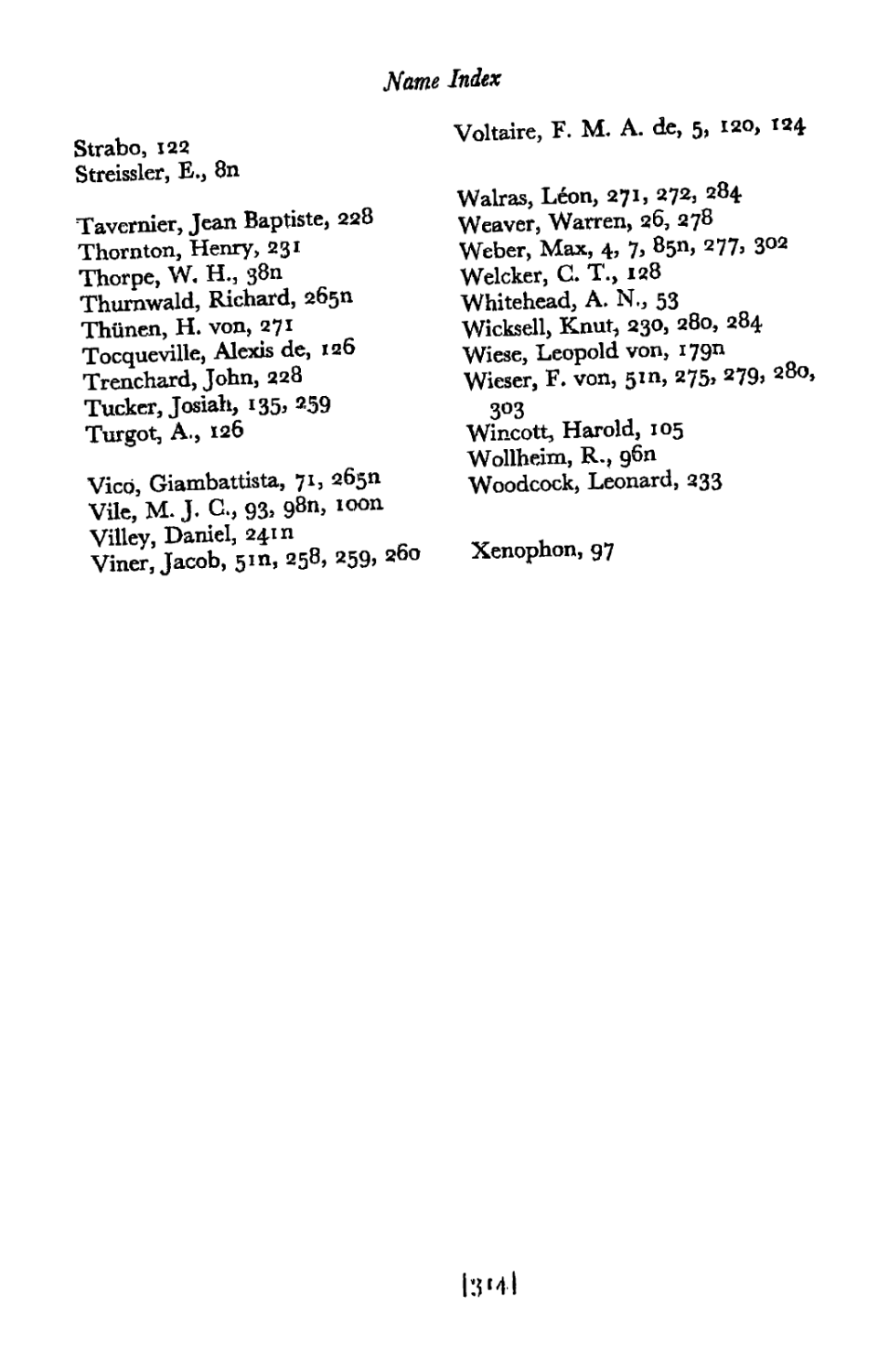

N an1e Index

( . utel1 tJ

Part Four

IIISTORY OF'IDEAS

.1)1"' Berna.rd 1\1andevil1e

.l\danl Smitll S Message in Today's IJanguage

TIle Place of Menger's GrundJiitze in tbe History

of l1:conomic Thought

Personal Recollections of Keynes and tbe

'!(cyncsia.n Revolution'

,

Nature lJ. Nurture Once ....\gain

Socialism. and Science

I 'Ii I

249

26 1

27°

28 3

29°

295

3°9

3 11

Preface

'This long-col1tcmplatcd further volume of Studies has been delayed

mainly by uncerta.inty about whether I ought to include the various

essays preparatory to my inquiry on LauJ, Legislation and Liherty

,vhich for years I doubted my ability to complete. Much the greater

part of wllat I published (luring 111e last 10 years were preliminary

studies for that ',,'ork whic.h h 1.d little importance once the clrief

conclusions had found tl1eir final [orIn ili tllat systematic exposition.

"Vith twa valu.mes published and the third near completion I feel

navy suHiciently confidt nt to leave nlost of those earlier attempts

dispersed as they are and have only it1cluded in this volume t\VO or

three of them which seem to rne still to provide additional material.

On the ,\t]10Ie the present volume tllUS deals again equally \f'!ith

problems of phl1osophy, politics and economics, though it proved to

lje a littlc nlorc difficult to decide to which category some of the essays

belonged. S0I11e readers nlay feel that some of the essays in the part

on philosophy deal more with psychological tlrdn Vvith strictly

philosopliical prob1t ms and that the part on economics now deals

chicfly witll what as an acadernic subject used to be called 'money

and bankil1g'" The only difference in forn1al arrangement from t11e

first volunle i that I ba\t c thought it appropriate to give the kind of

articles which in the earlier volume I had placed in all appendix the

status of a fourth part under the heading 'History of Ideas' and t9

amend tile title of the volume accordingly.

Of the articles contained in this volume the lectures on 'The

Errors of Constructivism' (chapter I) and 'Competition as a Dis-

c.overy Procedure' (cl1apter 12) have been published before only in

German, \vJlile the article on 'Liberalism t (chapter 9) \'Vas written in

English to be published in an Italian transiation in the Enciclopediil

del Novicento by the Istituto della Enciclopedia Italiana at Rome. 'J'u

tllen1 as well as to all the otherpubIishers of the original versions uanl(. d

in thc footnotes at the beginning of each chapter I amgreatlyillde1)tt tl

fbr permission to repril1t..

Frc ih'Ur i.B. F. ./\.. IIAYJI'.K

April 197 1

('vi j I

C,HAP1'ER ONE

The Errors of Constructivism *

I

It scelned to n}c Jl('cel'Sary tu illtrod"ilCe the tern1 'c.OI1structivisnl :t as a

specific naIne ffJf a marroer of thiJlkitJ..g that irl the past has often, l)ut

n1isleadi.ngly, beeIl described as 'ratiollalism'. 2 The ba ic conception

of this constructivism can. perhaps be expressed in. the simplest

11)anner by the innocent soundirlg formula that, since Inan has

hirnself created tile institutions of society and civilisation, lle must

also be able to alter them at viiIl so as to satisfy l1is desires or wishes.

It 1.S almost 50 years since I first heard and \-vas greatly impressed by

this fOI'IDula.. 3

At first the current phrase that mall 'created' his civilisation and

its institutions may appear rather harn;lless and commonplace. But as

soon as it is extend eel, as is freq\lently dOIle: to Inca.n tJlat man was

able to do this because he was endowed v!ith reason, t11e implications

bccoDle quefstionablc. l\lan did not possess reason before civilisation.

* An inaugural lecture delivered on 27 January 1970 on th.e asSWtlptiOfl of a visiting

professorship at the Paris-LodroTL Ulliv( rsjty of Salzburg and )rlg.inaUy published as

Di£ Irrliimer de.. J(on.druktivi.\'mus und die Grutidlagen legitimtr }(ritik gesellsr./Jqj;/icher Gebiltie

Munich, 197 0 ) reprinted Tiibingen 1975- r-.rhe fit'St two paragl'aphs rda-ring soldy to

local circumstances have been omitted froL'Y\ this translation.

I See my Tokyo lecture of J 964 on 'Kinds of ratronalism in Studies in PililQJoP!t'Y, PolituJ

and &onomit.s J London and Chic l.go, 19 6 7.

2 1 have com.e across occasionalrtferencC5 to the fact that the adjective con.structi\'ist'

"vas a. favourite term of W. E. Gladstone, but 1 have not succeeded in finding H in his

published worb". More recently it has a130 been used to describe a m()Vf; nlent in art.

where its mt g is not unrelated to the (:onc pt here discussed. See Stephen Bann,

Th8 Tradition Q.fConslrudivwn, London, 1974. Perhaps) to show 'L. at we use tbe tcrm in

a critical 8cnse t 'constructivistic' is better tha.n tconstructivist'.

9 In a lecture by \V. C. l\.1:itchell at Columbia University in New York during the year

19234 If I had even then some reservations about this statement it wa., mainly due to

the discussion of tne efft=Cts of 'non..reBected action' in Cad Menger, UnkrsucltJJngen

iihef! die MethQden der Sat:i4lwwenschaften und der politischen Ok01Jo.rnie insbuondne J Leipzig,

1 nH3-

[3]

The Errors oj Constructivis11Z

'I I,c t,.yo evolved together. We need mercly to consider language,

\vhicll today nobody still1.)clievcs to have been 'inVcllted' byarational

I H'jng) in order to see that reasotl and civilisation develop in constant

luutual interaction. But w}lat ,\,re 110W no longer question \vith regard

10 Janguagc (thougl1 everl that is c0I11paratively recent) is by no

rneans generally accepted "rith regard to morals, law, the skills of

handicrafts, or social institutions. '''le are st.jJl too easily led to assume

i hat these p}lenomena) \vhich are clearly the resuJts of human action,

BlUst also have beer} consciously designed by a ]luman rrlind, in

(:ircliDlstanecs created for tl1e purposes ,vhicJ1 tll( Y serve - that is,

that tiley arc \-vhat lvlax vVcbcr called wert-rational/: products. In

short, 'V\'e arc l11isled into thinklng that morals, ]a\ { HkiJls and social

iU5titlltions can only be justificd in so far as they correspond to SOIne

1 )l'ccollceived design.

It is significant that this is a mistake we usuaHy comrnit only \vith

r \ogard to tIle pll( nomcna of our own civilisation. If the ethnologist

C)f social anthropologist attempts to understand other clllturcs, he h,as

110 doubt that their members freqllently have no idea iiS to the reason

(,')}"' observing particular rules, or vvl1at depends on it. Yet most

1110dcrn social theorists arc rarely "villing to admit that tIle sanlC tl1ing

applies also to our o\vn civilisatiol1. "ATe too frey'ucntly do not kno\\;

what benefits we derive from the usages of our society; and such

s(lrial theor.ists regard this merely as a regrettable deficiency ",,"hich

4HIght to be removed as soon as possible.

2

I t1 a s}lort lecture it is not possible to trace the history of the discus-

sion of these problems to which I have given some attention in recent

y( ars. 5 I will merely mention that they were already familiar to the

;lucient Greeks. The very dichoton1Y bet\\'een 'natural' and 'artificial

1,)r1na.tions "",hich the ancient Greeks introduced has d.ominated the

(1 iscl1ssion for 2 ooo years t U nfortunately-, the Greeks distinction

1 )t (\veen natural and artificial l\as become the greatest obstacle to

f u.rther advance; because, interpreted as an exclusive alternative,

,I S('C Ma V\'eber, WirtscTuzfl und Ge.'tell.fchtJjt, 'I'ubingcn" 1921, chapter 1, paragraph 2,

,..,here we get little help, hO¥f""ever, since the 'values' to which the discussion refers are

i( 'un in effect reduced to consciously pursued particular airns.

'. Sr'e particularly nlY es. ays on 'Th results of human action but not of human d( iKn'

ILIa I '"I'h(' k' a1 philosophy of David Hunu" in Studies on Philosopk , Poli,ic.f and Ec.onornil:.\,

,l1ld tHY '<'(:1'1&1"(' Oil 'I),. Ucrnan1 MalHlf'vi1I1-'. puhlisiu:(1 in this buok1 p. 1q.

r .11

The ETrO'1'S of Constructivi.rm

this distinction is not only ambiguous but dcfinitel)' false. As was at

last clearly seen by the Scottish social philosophers of the cightcCllth

century (but tho late Schoolmen had already partly seen it), a large

part of social formations, although the result of human action, is not

of human design. 1'hc consequence of this is that suell formations,

according to the interpretation of the traditiol1al terms" could be

described eitl1er as '11atural', or as 'artificial'.

The beginning of a tTUC appreciation of these circumstances in

the sixteentll centluy \vas extinguislled, however, in tIlc seventeenth

cetttury by the rise of a P?werful ne,v philosophy - the rationalism of

Rene Descartes and his followers, frOln whom all mod rn forms of

constructivism derive. From Descartes it ,"vas taJ<:en over by that

unreasonable 'Age of Reason), \vhich ,vas entirely dominated by the

Cartesian spirit. Voltaire, tilc greatest representative of the so-called

C Age of Reason', eXIJressed the Cartesian spirit ill his famous state-

ment 'if you want good laws, burn those you have and n1ake

yourselves new ones', 0 Against this, the gIeat critic of rationalism,

David Humc, could orIly slo\vly elaborate the foundations of a true

theory of the growth of social formations, which ,vas further

developed by llis fellow Scotsmen, Adam Smith and Adam Ferguson)

into a theory of phenomena that are 'tIle result of human action but

not of human design'.

Descartes had taught tl1at \ve s110uld only believe what we can

prove. Applied to tl1c field of nlorals and values generally, his

doctrine meant that \ve should only accept as binding what we could

recognise as a rational design fOf a recQgnisable })urpose. I wi111eave

undecided how far he himself evaded difficulties by representing the

unfathomable ,vit1 of God as the creator of all purposive phenomena. 7

For his successors it certainly became a human will, which they

regarded as the source of all social formations whose intention must

provide the justification. Society appeared to thelTI as a deliberate

6 Voltaire, Dutionnaire /Jhilo90pltique, s.v. '.Loi', reprinted in (Euvres philosophique.s de

Voltaire, ed. Hachcttc, Pa.ris n.d., Xv'III, p. 432.

7 De9cartes was sorncwhat reticent about his vie\vs on political and moral problems and

only rarely explicitly stated the consequence of his philosophical principll.ag for these

questions. But compare the famous passage at the beginning of the second part of

Discours de la mithotk where he \vrites: Ije croil) que, si Spartc a ete. autrefois tres

florissante, ce n)a pas ete it cause de la bonte de chacune de ses lois en particu1ier,

vus que plusieurs etaient fort etrangc ct me me contrairc a bonnes meurs; mais a

cause que, n ayant ctc inventee que parun scu1, elles tendaienttoutes a meme fin). The

consequences of the Cartesian pI)ilosophy for mor are well shown in Alfred Espinas)

Descartes et la Morale, Paris, 19 2 5.

[5]

The Errors of (}onstructivisrn

construction of men for an intended purpose.... shown most clearly in

the ,vriting of Descattes t faithful pupil J.-:J. Rousseau. 8 The belief

in the unlinlited power of a supreme authority as necessary, especially

for a representative assembl1', and therefore the beJiefthat democracy

necessarily means the unlimited power of the majority, aTe ominous

consequences of tl1is constructivism.

3

You will probably most clearly see what I mean by 'constructivisn1'

if I quote a characteristic statC111eIlt of a ¥lcIl..kno\vn Swcdisll

sociologist, whic!l I recently encountered in the pages of a German

popular science journaL 'The most important goal tl1at sociology

has set itsclf" he \'Vrote, 'is to predict the future deveLopment and to

shape (gestalten) the future, or, if one prefers to expr,css it in tl1at

rnanner, to create the future of mankind.' If a science makes such

claims this evid.ently implies the assertion that tIle whole of lluman

civilisation, and all we have so far achieved, could only have been

built as a purposive rational constructiOIl.

It must suffice for the moment to show that this consfructivistic

interpretation of social formations is by no means nlerely harmless

philosophical speculation j but an assertion of fact from which

conclusions arc derived concerning both the explanation of social

processes and the opportunities for political action. The factually

erroneous assertion, fi"'om wl'lic11 the constructivists derive such far-

reaching consequences and demands, appears to me to be that the

complex order of our modern society is exclusively due to the cir-

cumstance that men have been guided in tlleir a( tions by foresight -

an insight into the connections bet\veen cause and effect- or at least

that it could have arisen tllrough design. What I \vant to show is that

8 Cf. R. Derathe J Le Ra'ionalisme rk J.-J, Rou.rseau, Paris, 1925-

9 Torgny rr, Segerstedt, 'Wandel der Gesel1schaft , Bild der Wijsenscllaft vol. VI" no. 5,

!\{ay 1969, p. 441. See also the same author's Gesellschaftlir.he Herr.vchaft <lis Joziologisehes

KQnzepl, Neuwied and Berlin, 1967. Earlier examples of the constantly recurring idea

of mankind or reason detennining itself:, particularly by L, T. Hobhouse and Karl

l\.fannheim, I have giv n on an earlier occasion (The CDunter..RevolutioTl of Scie'Jce"

Chicago l 195 2 ), but I had not expected. to find the explicit assertion by a representative

of this view. such as the psychologist B. F. Skinner ('Freedom and the control of men',

Tlu: American Scholar, vol. XXVI) no. It [955-6, p- 49) that 'Man is- ablr., and now as

neVl'r before, to lift himself up by his own bootstraps'. The reader will find lhat tilt,

sam( idea appears also in a stateJnent of the psychiatrist G.. U. Chisbulrn, In IU" ((uutted

lalt T .

Ifq

The Error..r of ConJtructivij'm

men are in their conduct never guided exclusiuefv by their undcr w

standing of the causal conncctioIlS betweel1 particular known means

and certain desired ends, but always also by rules of conduct of

whicll they are rarely awarc, ,vhich they certainly 11ave not con...

sciously invented, and that to discern the function and significance

of this is a difficult and only partially achieved task of scientific

effort" Expressing tIns differently - it means that the S11ccess of

rational striving (Max Weber's zweckrationales Handeln) is largely

due to the observance of values, whose role in our society ought

to be carefully distinguislled frotn tllat of deliberately pursued

goals.

I can only briefly m( ntion tbe further fact, that Sllceess of the

in(livi(lual in the achic-venlent of 11is imm.cdiate allls depellds, J.lot

only on his conscious insight into causal connections, but also ill a

high degree on his ability to act according to rules) w}lic}lllC may be

unable to express in "\Fords, but \vhich we can only describe by

forml1lating rules, All our skills) from the command of language to the

mastery of handicrafts or games - actions whicll we 'know ho\v' to

perronll,vithout being a.ble to state flOW we do it - arc instances of

this. 10 I me11tion them here only because action according to rules -

which we do not explicitly kno'\v an(l whicll have not been designed

by reason, but prevail because tIle manner of acting ofth.Qse who are

successful is imitated - is perhaps easier to r cognisc in tllese instances

than il1 the ficld directly relevallt to my present COl1ccrns.

The rules \ve arc discussing are those that are flot so much useful

to the individuals who observe them) as those that (if they are

generally observed) make all the mernbers of the group more effective,

because they give them opportunities to act witlun a social order.

These rules are also mostly not the result of a deliberate choice of

means for speejfic purposes, but of a process of selection, in the course

of which groups tllat achieved a more efficient order displaced (or

were imitated by) others, often without knowin.g to wllat their

superiority was due. This social group of rulcs includes tIle ru1es of

law, of morals, of custom and so on - in fact, all the values whicll

govern a society. The terrn 'value', which I shall for lack of a bett('r

one have to continue to use in this context, is in fact a little rnls",

leading, because we tend to interpret it as referring to particnlar

aims of individual action, while in the fields to Wruc11 I ani refi rrin

10 SC( rny essay on 'Rules, perception and inh:l1igibi1ity' in Stlldie in PhilfJJIJJJi!v J J'ulilic.,'

mid Economics.

ri.'

The Errors of G'onstructivism

they consist mostly of rules which do not tell us positively what to

do, but in most instances ll1erely what we ought not to do.

Those taboos of society which are not founded on any rational

justification ha\'e bee}} the f1lvourite suqject of derision by the

constructivists, \vho 'ViS}l to see them banned from any rationally

designed order of society. Among the taboos they have largely

succeeded in destroying arc respect for private property and for the

keeping of }}rivate contracts, with the resuJt that some people doubt

if respect for tl1em Ca1} ever again be rcstored. 11

:For all orgalllsms j however, it is often more important to know

what tIley must not do, if they are to avoid danger, than to know

what t]lCY must do in order to achieve J)articular ends, The former

kind of knowlcdge is usually not a kllowledge of the consequences

wInch the prohibited kind of conduct would produce, but a know-

ledge tllat in certain cOIlditions certain types of conduct are to be

avoided. OUf positive kno\vlcdge of cause and effect assists us only

in those fields ,vl1cre our acquaintance with tile particular circum-

stances is sufficient; and it is important that we dO.l1ot move beyond

the region where this knowledge will guide us reliably. This is

aclucved by rules that, witllout regard to the consequences in tIle

particular instance, generally prohibit actions of a certain kind. 12

That in this sense man is not only a purpose-seeking but also a

ruJe-folIowi.llg auhnal lIas been repeatedly stressed in the recent

literature. IS In order to understand \vhat is meant by this, we must

be quite clear about the meaning attached in this connection to the

word 'rule', Th.is is necessary because those chief-Iy negative (or

prohibitory) rules of conduct whicll make possible the formation of

social order arc of three different kinds, which I now spell out. These

kinds of rules are: (I) rules that are merely observed in fact but

have never been stated in words; if we speak of the sense of justice'

or 'the feeling for language' \ve refer to StIch rules which we are able

to apply, but dQ not know explicitly; (2) rules that, though they

II cr. J for example, Gunnar l\/Iyrdal, Beyond the Welfllre State) London, 1969, p. 17: 'The

important property and contract taboos, so- basic for a stable liberal society, were

forcibly ,veakened \vhcn big alterations were allowed to occur in the rea1 value ()f

currencies'; and ibid,) p. t9 (Social taboos can never be established by decisions

founded upon reflection and discussion'.

J 2 1 have treated these problems more extensively in my lecture on Recht.. rdnung und

Ha,ndelnsordnung in E, Streissler (eel.), ur Einhe.it der Recht.s - und Staatswis.ren-

J"choften, Karlsruhe, 1967; reprinted in my Freibutger Studien, Tabingen J 96g as wdl

as in my Law, Legi.Jlation and Liberly vol. I, Rules and Orde" London and Chicago, 1973.

13 R, S. Peters, The Concept of Motivation, London, 195 8 , p. 5.

1'81

The Errors oj Cort.rtructivism

have been stated in ,-vords j still merely ex-pre s approximately what

has long bcforc been gcneraUy observed in action; aIld (3) rules that

have been deliberately introduced and therefore necessarily exist as

words set out in sentences.

CotlBtruc:tivists 1,vould like to reject the -first and second groups of

rules, and to accel)t as valid only the third group I llavc m Jltioned.

4

What tl1en is tl1e origin of those rules that 1110St people follQ'" but few

if anyone can state 111 words? I,fang bcfore Charles Darwin the

theorists of society, and parlicularly those of languagc, had givel1

the answer that in the proces of cultural transmission, in which

modes of conduct arc passed on from generation to generation, a

process of seleetion takes place, ill wllich those modes of conduct

prevail ,vhicllicad to tl1e fortnation of a more efficient order for the

whole group, because such groups w'i1l prevail over others. 14

A point needing special empl1asis, because it is so frequently

misunderstood, is that by no means every regularity of conduct

among- iIldivid.uals produces an ol'der for the \vhole of society.

"Therefore regular individual conduct does not necessarily mean

order, but only certain kinds of regularity of tbe conduct of in..

dividuals lead to an order for the whole, rrhe order of society is

therefore a factual state of affairs whic]l must be distinguished

from the regularity of the conduct ofindividua1s. It must be defined

as a condition in which individuals are able, on the basis of their own

respective peculiar kno\vledge, to form expectations concerning the

conduct of others, which are proved correct by making possible a

successful mutual aqjustment of the actions of these individuals. If

every person perceiving another were either to try to kill him or to

run away, this would certainly also constitute a regularity of

individual conduct, but not one that led to the formation of ordered

groups. Quite clearly, ccrtah1 combinations ofsuch rules ofindividual

conduct may produce a superior kind of order, which will enable

some groups to expand at the expense of others.

This effect does not presuppose that the members of the group

know to which rules of conduct the group owes its superiority, but

14- See on these 'Darwinians before Darwin' in the socia1 sciences my essays (The

resultc\ ofhurIJ.an action but not ofhulnan design' and 'The lega.t philosophy ofl)a.vid

1 Jwnc' in Studies in Philo.fOp/ vJ Poli';c,'i and Economic;s.

19 J

The Errol's of Co nstt.uctiv ism

merely tllat it "viII accept only those i11dividuals as n1cmbers \vho

observe the rules traditionally accepted by it. TIlere \l'ill al\vays be

an amount of cxperietlce of individuals prec pitated in such rules,

which its living mcnlbers do not ktlOW, but \vhicl1 nevertheless help

them more effectively to pursue their ends.

"l"1his sort of 'kIl0\vledge of the 'Norld tl1at is passed on ii'om

geIleration to generation will tllUS consist itl a great measure not of

knowledge of cause and effect, but of rules of conduct adapted to the

envirollhlent and acting like information about the environnlcnt

although tIley do not say anything about it. Like scientific theories,

they are prcservecl by proving thcrnselves useful, but, in contrast to

scientific theories, by a proof which no OI1C needs to kno\v, b<;cau$c

the proof mani[( sts it.self in the resilience and progressive expansion

oftllc order of society whir.!l it makes possib[c. T'his is the true content

of the n1uch derided ] dca of tI1C '\"lhrdom of our ancestors' embodied

in inherited institulions, which plays snell an important role in

conservative thought, but appears to the constructivist to be an

empty IJhrase signifying nothing.

5

Time allows IDe to consider further only onc of the many interesting

jnterrel .tioJ1s of tlris kind, which at tIle salne time also explains \'vhy

an ecoIlonust is particularly inclined to concern himself ,\lith these

problems: the connection between rules of law and tIle spontaneously

formed -order of t}1e market. 15 This order is, of course, not tIlC result

of a miracle or some natural harmony of intcre8ts. It forms itself,

because in the course of millennia. men develop rules of conduct

which lead to the formatiotl of such an order out of the separate

spontaneous activities of individuals. rI he interesting point about this

is that men developed these rules ¥trithout really understanding their

functions. Philosophers of la\v have in general even ceased to ask

what is the 'purpose' of law, thinking the question is unanswerable

because they interpret 'purpose' to mean particular foreseeable

results, to achieve which tIle rules were designed. In fact, this

'purpose' is to bring about an abstract order - a system of abstract

relations - concrete manifestations of which will depend on a great

variety of particular circumstances which no one can know in their

entirety. Those rules of just conduct have therefore a 'meaning' or

J 5 C..J: Iny lecture 'Rechtsordnung und l-Iande1nsordnung', cited ahove iu note J 2.

I to")

1hl? ErrQrs of G'Qr.structi 'ifm

'function) v{hicl1 no one has given them, a.nd vvhich soc.ia] theory

must try to discover.

I t w " the great achievement of econolnic theory that.' 200 years

before cybernetics, it recognised the nat\lre of suc11 self-regulating

systems in "'vhieI1 certain regu1aritics (or, perhaps better, 'restraints')

of conduct of the elements led to constant adaptation of the compre-

hensive order to particular facts, affecting in the first instance only

the separate elements. Such all order, lead.ing to the utilisatioIl of

much more information than anyone possesses, could not }lavc been

'invented; .. This f()11o\vs fronI the fact that the result could not bave

been foreseen. None of our ancestors could have know"n that the

prott ction of property and contracts would lead to a.n extensive

divisiorl of labour} sl,ccialisation and the establishment of markets,

or that the extension to outsiders of rules initially applicable only to

Inembcrs of the sanle tribe wou]d tend towards the formation of a

world economy.

.L ll that man could do was to try to improve bit by bit on a process

of mutuaJly aqjusting individual activities, b}r redllcing conflicts

through modifications to S01ne of the in11crited rules. All that he

could deliberately design, he could and did create only within a

system of rules, which he 11ad not invented, and with die aim of

improving an existing order. 16 Al\vays n1erely adjusting the rules, he

tried to improve the combined effect of all other rules accepted in his

community, In his efforts to improve the existing order, he was

therefore never free arbitrarily to lay do\vn any ne\v rule he liked,

but had always a definite problem to solve, raised by an imperfection

of the existing order, but of an order ]1C \vould have been quite

incapable of construf ting as a whole. "Vhat man found were conflicts

between accepted values, the significance of \Vllich he only partly

understood, bItt on the character of which tlle results of many of his

efforts depended, and which he could only strive better to adapt to

each other, b.ut which he could never create anew.

16 ct in this connection K. R. Popper, rile Ope-n Socie y and Its Enemi.es, Princeton, N.J.,

1963, vo). I, p. 64: 'Nearly all misunderstandings [of the statement that norms arc

man-made] can be traced back to one fundam.ental misconception, namely to the

bclicf that C'Ioconvention" implied arbitrariness'; also David Hume, A Treali..re on

Human .J{ature, in n'orkJ, ed. T, Ii. Green and T. HI Grose, London, tB90 vol. II,

p, 250 'Though the rules of justice be. arlifteial, they are not arhitrary. Nor i the

l."Xpcession improper to call them Lmvs of Nat7.lrc; ifby natural we understand wl1aL i

couunon to any species, or even if \ve confine it Lo nl( an what is inseparable frotlllhr.

speci . '

[JI]

The Erro'ts of Constructivism

6

The most surprising ]Ject of recent d( velopmel1ts is that our un-

deniably increased understanding of these circunlstances llas led to

new errors. \V( believe, I think rightly, that \ve have learnt to

understand the general principles \Vllicll govern the formation of

such complex orders as tl10se of organi:nns, lluman society, or perllaps

even the hUInan mind. ] xpcricnce in those fields in vvhich modern

science has achieved its greatest tritunphs lcads us to expect tha.t such

insigl1ts will rapidly also give us Inastery over the phenomena, and

enable us deliberately to deterrnine the results. But in the sp11er of

the complex phetlon1ena of life, of the mind J and of the society, \4{e

encounter a TIC\'" difficulty.17 Hovvcver greatly our theories and

iec11niques of 11lVestigatioll assist us 1.0 interpret the observed facts,

they give little help in ascertaining all those particulars \vhich enter

into the determination of the cotnplex patterns, and ,vhich '\ve would

ha\rc to know to achieve complete explanations, or precise

predictions.

If \ve knevv" all the particular circumstances ,vInch prevailed in the

course of the history of the earth (and if it were not for t11e plleno-

mellOl1 of genetic drift) we should be able \ ith the help of modern

gCl1ctics to explain ,.vhy different pccies of organisms have assumed

the specific structures vvl1ich they posRess. But it ''\i.ould be absurd to

assume that \VC could ever ascertain all these particular facts. It

may even be true that if at a given. moment someone could kno\", the

sum total of all the particular filcts \vllich a.rc dispersed among the

millions or billiol'ls of people living at the time, he ought to be in a

POSitiOl1 to bring about a more efficient order of human productive

efforts tl1an that achieved by the Inarket. Science cal1 help us to a

better theoretical understan(ling of the interconnections. But

science cannot significantly llelp us to ascertail1 all tile widcly dis-

persed and rapidly fluctuating particular circumstances of time and

place whicl1 detcrmine tl1e order of a great cOluplex society.

rfhe delusion that advancing theoretical knowledge places us

everywhere increasingly in a position to reduce complex inter-

connections to ascertainable particular facts often leads to new

scientific errors. Especially it leads to those errors of science which we

must now consider, because they lcad to the destruction of irreplace-

17 cr. my essay on 'The theory of c01nplex phenomena in Studies in Pltilosoph..v, l)oliticJ

lmd E.canomic.r.

I J 2J

The Errors oj Constructivism

able ,ralues, to \Vllicll 'AIC O\VC our socjal order and our civilisation.

Suc:11 errors are largely due to an arrogation of pretended knowledge,

which in fact no one possesses alld ,,,,hich even the advance of science

is not likely to give us,

(Joncerning our modern ec.onomic system, understanding of the

principles by wInch its order forms itself sho\ys us that it. rests on the

11se of kno\vledge (arid of skills in obtaining relcv'ant information)

,vhich no onc possesses ill its entirety, and tha.t it is brought about

because iJ)di lidual arc in their actions gui.ded by certain general

rules. Certainly, \VC OUg}lt not to succumb to the false belie£: or

delusion, that \ve can replace it \\i"ith a differel1t kind of order, \vhich

presupposes that all this knowle{Ige can be concentrated in a central

brain, or group of brain$ of al1.Y practicable size.

"The fact, ho\vever, tha.t in spite of all the advance of OUf know-

ledgc) the results of our erldeavollrs remain dependent on circum

stances about which ,vc k.now little or nothing, and on ordering forces

we cannot contl.ol, is precisely what so many people regard as

intolerable. Constructivist.s ascribe tllis interdependence to still

allowing ourselves to be guided by values which are not rationally

demonstrated or given positive proof as justification for them. They

assert that "'lC no longer need to entrust our L:1.te to a system, the

resultH of '\VlllCh. \VC do not determine beforehand, although it opens

up vast ne,v opportunities for the efforts of individuals, but at the

same time resem bIes a game of c}lance in Some respects, since no

single person bears resporlsibilit)'- for the ultimate outcome. The

anthropomorphic hy'postasation of a personified mankind, who

pursue aims they have c011sciously chosen, thus leads to the demand

that all those gro\vn values not visibly serving approved ends j but

v{hich are conditions for the formation of an abstract order, should

be discarded to offer individuals improved prospects of achieving

their different and often conflicting goals. Scientific error of this

kir.rl tcnds to discredit values, on the observance of which tlle survival

of our civilisation may depend..

7

This process of scientific error destroying indispensable valu($

comml 11C( d to play an important role during tllC last century. Tt is

specially associ.ated witll various p11ilosophical views, ,vhich their

I ' ) 1 ' 1 ,. , . , 1 J . I

_u1thol'S ((.' 1.0 ( eserl JC as .l10S1tlVlst, ltcaUS(' t. l1'Y WI 1 tu rt:(:oAui C'.

I J i I

The Error \' of (, Ol1.\.trtll;/.il. iS1n

as usefltl kno\vledge only insights into tlH: connection bcnveen

cause and effect. 'rhe very naIne - positus rneaning 'set doV\rn' -

expresses the preference for the deliberately created over all that hac;

not })e.cn rationally designed. The fOUlldt"r of ihe positivist movement,

Auguste COlnt( , clearly expressed this hasi{ id( a \v]len he a scrtcd

the utlq uestionable su periority of de1l10118tl'L ted over revealed

morals..18 1'11e phI'ase sho\\ts that the on]y choice lIt rccogniscd ,vas

that between de1ibcratc cr ation by a huruan n,ind and creation by a

superhuman intelligence, and that 11e did n01 eVC11 consider the

possibility of any origins .lrOnI a process of seleetive evolution. The

m.ost irnportant later nlanifestation of tl1is construc.tivism in the

course of the ninct( enth century W $ 11tiIitariani!;nl, the treatrncnt

of all nor111S in episteJ.TIological positivism in general and legal

positivisnl ill particular; an.d fi.lla1.1y, I believe, the wl101e of socialism.

In the case of utilitarianism. 1 this character is elcarly SI10W11 in its

original, particularistic forrrl, 110\V generally distinguished as act

lltilitarianism' from 'rulc utilitarianism j .. T11is llone is faithful to the

original idea that every single decisioll IDust be based on the per-

ceived social utility of its particular effects; vvhile a generic or rul

utilitaria.ni$ffi, as has ofterl been shown c,ann.ot be consistently

carried throught Itt Side by side ,vitI1 these attempts at CQllStructivistic

expianatioI1 \VC find in pl1ilosophical positivisnl, hovV"cver, also a

tendency to dispose of all values as things which do riot refer to ficts

(and, ulerefote, are (metaphysjcal') or a tende,ncy to treat them as

pure nlatters of enlotion and therefore rationally- not justifiable, or

meaningless, The most naIve version of this is probably fl1e 'emotiv-

ism' that has bcetl popular in the course of the last 30 years, The

expounders of 'emotivisn1 s20 1Jelieved that, with the statCm.cnt tbat

moral or imnl0ral, or just and llIJjust, action evokes certain nIoraI

feelings, they had explainer} sonlething - as .if' the question, vvhy a

certain group of actiol1S causes one kind. of emotion, and another

group of actions a110thcr kind of emotiol1, did lInt raise all impcn tan l

problem of the significance tlus has for tIle ordering of life in society.

18 Auguste Comte, Sys'eme de la jJolitique positive, Paris, 1854, vQl. I, p. 356: La superi..

orite de la. moral demorrtrf.c sur la moral revelee!"

9 Concerning the results of the :uorc rccent discussion of utilitarianism see David Lyons,

Forms and Lunits of (.ltil-ita.rianism) Oxford, 1965; D. Ii. Hodgson, Consequencr-s oj

Utilitaria, istn) Oxford, 1967; and the convenient collection of essays in M, D Bayles

(00.), Contemporary Ulili'arianism, Ne\v x ork, 1968.

20 S the writings of Rudolf Carnap, and particularly A. J. A.yer Lr:ltll1uage, Truth and

Lo, if, Loudon, I!} 6.

11/11

The Errors of Constructivism

'he constructivist approach is most clearly to be seen in the

original form of legal positivism, as expounded by TI10mas Hobbes

and John Austin, to whom every rule of law must be derivable from

a conscious act of legislation. This, as every historian of la, v kno\vs, is

factually false. But even in its most modern form, which I will

briefly consider later, this false assumption is avoided only by

limiting the conscious act of creating law to the conferring of validity

on rules, about tIle origin of tIle content of whicIl it has noth.ing to

say. This turns the vhole tlleory into an uninteresting tautology,

which. tells us notl1ing about 110W the rules can be found which

the judicial authorities must apply.

The roots of socialism in constructivisric thougl1t are obvious not

only in its original form - in which it intended through socialisation of

the nleans of production, distribution and exchange to make possible

a planne(l economy to replace the spontaneo.us order of the market

by an orga11isation directed to particular cnds. 21 But the modern

form of socialism that tries to use the n1arket in the service of what is

called 'social justice', and for this purpose \vants to guide the action

of men, not by rules of just conduct for the individual, but by the

recognised importa11ce of results broug}lt about b}' the decisions of

authority, is no less based upon it.

8

In our century COIlstructivism has in particular exercised great

influence on ethical vicws through its effects on psychiatry and

psychology. Within the time at lny disposal I can give only two of

many examples of that destruction ofva1ues by scientific error, \vhich

is at work in these fields. With regard to the first example, which I

21 The recognition of the defects of these plans is now generally andjust1y ascribed to the

great discussion which was started in the 1920S by the writings of Ludwig von Mises.

But we sho'nd -not overlook how many of the. important points had been clearly seen

ear1ier by some economists. As one forgotten instance a statement by Erwin Nasse in

an article cOber die Verhutung der Produktionskrisen durch staatliche Fursorge',

JahrbucllfiJr Gesetzgebung ttc., N .S., r879J p. 164, may be quoted: 'Eine planmassige

Leitung der Produktion ohne Freiheit. der BedarfS.. und Berufswahl wiirde nicht

gcradczu undcnkbar, aber mit einer Zerstorung alles dessen, was das Lebe.nlebens-

V,.Cl.t macht, verbunden scin. Einc plann :tssigc LCllw1g der gesam.ten wir chaft..

lichen Ta.tigkcit mit Freiheit der Bedarfs.. und Beruf. wahl zu vercinigen ist cin

Problem, das nur mit der Quadratur des Kr("iscs verglichen \verden kann, Dcnn, so

wie manjedem gestattet, die Richtung und Art seiner wirtschaftlichcn 'I'atigkcit wid

Konsumtion frei zu bestimmen: ver1iert m \n di( Lcituug cler Gesamtwirt..'Jch",n au

(IeI' l[and,,:t

[151

The Errors of Constructivism

take from a psychiatrist.) I must first say a fe'tv words about the

autllor I sllall quote, lest it be suspected tllat in order to exaggerate

I have chosen some unrepreScl1tative figure, TIle interIlational

reputation of the Canadian scientist) the late Brock (Jhisholm, is

illustrated by tIle fact that he had been cntru'sted with building up the

VVorld Ifealth Organisation, acted for live years as its first Sccretary-

General and ,vas linally elected President of the World f'cderation of

Mental I-Icalth.

Just before Brock Cllisholm embarked all t11is international career

he wrote :22

The re..interpretation and eventual eradication of the concept of

right and \\ rong Wllich l1as been the basis of cllild training, tIle

substitutiol1 of intelligent a,nd ratioIlal thinking for faith. in tl1c

certainties of the old people, these are tllC bclated objectives of

practically all effective psychotl1erapy. . . . "'fhe suggestion that

",.,e should stop teaching children moralities and right and

'Vfong and instead protect their original intellectual integrity

has of course to be lnet by an outcry of heretic or iconoclast,

such as was raised against Galileo for finding another planet,

2 George Drock Chisholm, r-rhe re-estabHshmcnt of peacetime society II, The William

Alamon White Memorial Lectures, 2nd series, l chialryt vol. IX, no. 3, February

194 6 (with a laudatory introduction by Abe Forta )J pp. 9-11. Cf: also 1\'{0 books by

Chisholm, Prescription for SUTVival, N{:w York! 1957, and Can People Learn to Learn?

New York, J 9S8 J as \vel1 as his essay 'The issues concerning man's biological future'

in The Great Issues fir Conscience in lvfodern Medicine, Hanover, N.H" 19 60 , where he

argQes (p. 61): 'We haventt even got a govc;rnment department that I kn )w of that

is set up to concern it.sclf with the "survival of the human race". Au.d if there is any

question about which we have no government department, it obviously is hot very

.important. !

It would be possible to quote here any number of similar utterances of the last

S5 0 years. The R,u5:)ian revolutionary A!coL''tndcl" I-Icrzen was able to \'v"rite: (You

want a book ofmlet>, while I think that when one reaches a certain age, one ought to

be ashamed of having to use one', and the truly free. man creates his own morality!

(Alexander I-Ierzen, From tile Other Shore, l d. 1. Berlin., London, 195 6 , pp. 28 and 141);

this is little different from the vieV\."S of a contemporary logicaJ positi\ ist such as Hans

Reichenbach \vho argu s in The Rise oj Scientifi£ PhilosopJ!y Berkeley, Calif., 1949,

p. 14 1 that 'the power of reason must be sought. not in rules that reason dictates to

O\1r i1nagination, but in the ability to free ourselves from any kind of rules to which

we hn ve been conditioned through experience and tradition', The statement by

J. M. Keynes, Two Memoirs, London J 1949, p. 97, which on eatlicr occasions I have

q uolt!d in. Ulis connection t appears to roe to have largcly lost its significance in this

{ ( nllcxt ince Michael Holroyd in Lytton Strachey, a Critual Biography, London t 1967

aile} a9()H, 11assho,, n lhat the D1ajority oftbcmclnbcrs of the group about which Keynes

)Juk(:. iududiug hiln,t;dl w 'n luunosexual J which is pf()bably a sufficient explanation

..r Ilwil' n'volt n aiu t ru1ill' 'Hu1'al .

I ,h I

The Errors of Constructivism

and against the truth of evolution i and against Chrh;t's

interpretatioll of tIle Hebrc\\r Gods, and against any attem})t to

change tIle mistaken old ways and ideas. 1"'1he pretence is made,

as it Ilas been made in relation to the finding of any

extension of trutll, that to do away with right and 1-\ T rong would

produce uncivilized peoplc immorality, lawlessness and social

c}laos. The L1.ct is that most psyc11iatrists and psychologists and

Jnany other respectal>lc peopJc have escaped from these moral

chains and arc able to observe al1d think freely. . . . If the. race is

to be freed from its c.rippling burden of go()d and evil it must

be psychiatrists \vho take th( original responsibility. This is a

challenge \vhicl} must be met. . . . 'VitI1 ttle other human

sciences, psychia.try nlust no,v decide "vhat is to be the

inlmediatc future of tIle hUl'nan race. No one else can. And this

is t]1C prime responsibility of psychiatry,

It never seemed to occur to Chisholm t11at moral rules do not

directly serve tIle satisfaction of individual desires, but are required

to assist the functioning of an order; and even to tame some instincts,

whicl1 n1an has inllcrited from llis life in small groups \vhcre he

passed most of his evolution. It may ,veIl be that tl1e incorrigible

barbarian in our midst rcserlts these restraints. But are psychiatrists

really tlle con1pete.nt authorities to give us new morals?

Chis1101m fillally expresses the 110pe t}lat two or three million

trained psyclliatrists, ,vith the assistance of appropriate salesmanship,

,viII soon succeed in freeing men from the 'perverse' concept of

right and ,.yrOIlg. It sometimes seems as if they have already had too

rnuch success in tl1is direction.

My second COlltemporary example of the destruction of values by

scientific error is taken fronl jurisprudence. There is no need in this

instance to identify tl1e autllor of the statement I shall quote as

beIongtng to the same category. It comes from no less a figure than

ll1Y former teacher at the University of Vienna, Hans Kelsen. He

assures us that )ustice. is an irrational idea', and continues :23

3 JIan Keben, What is ]ustiJ:eJ, Berkeley, Calif:, 1957, p. 21; almost literally the same

statt Jnent oc.curs in General Theory oj'Law and Stale, Cambridge, Mass'J I949, p. 13.

'flu: e1ixnination from the law' of the concept of justice W of course not a discovery of

Kds( n but is COlnlnon to the whole of legal positivism and is particulal"ly character-

istic of th( German theorist of law around the turn of the century of whom Alfred

vun M'urtin, lYlensch und GesellscJlOft Heutt, Frankfurt a.M. J J 965, p. 265) tightly says:

'In wHht'hninjschcr Zeit machtcn schliess1icb, wie (;raf Harry K( 5S1er in seioC"J\

[{jo'Ltim d overleaf

(''(71

The Errors of Constructivism

from tIle point of view of rational cognition, there are only

interests of human beillgs and hence conflicts of in terest. The

solution of these can }Je brougllt about either by satisfyil1g one

interest at the expense of the other, or by a compromise

between the existing interests. It is not possible to prove that the

one or the other solution is just.

Law is thus for Kelsen a deliberate construction, serving known

particular interests. This migllt il1dced be necessarily so, if we llad

ever to create anew the whole body of rules of just conduct. I \viU

even concede to Kelsen that \ve can never positively prove \vhat is

just. But this does not preclude our ability to say when a rule is

unjust, or that by tl1e persistent application of such a negative test of

injllstice we may not be able progressively to approach justice.

It is true that this applies only to the rules of just conduct for

individuals, and not to what KeIsen, like all socialists, }lad primarily

in mind - namely, those aims of the deliberate measures enlploycd

by authority to achieve w!1at is called 'social justice'. Yet neither

positive nor negative criteria of an o jective kind exist, [rOlIl which

to define or test so-called 'social justice', which is one of the emptiest

of all phrases.

The nineteenth-century ideal of liberty ,vas based on the conviction

that there were such objective ggeneral rules of just co:ndtlct; and

the f lse assertion that justice is always merely a matter of particular

interests has contributed a great deal to creating the belief that ''\FC

have no choice but to assign to each individual what is regarded as

right by those who for the time being hold the power.

9

Let me clearly state the consequences that seem to follow from what

I have said about the principles for legithnate criticism of social

formations. Mter laying the previous foundations, this can be done

in comparatively few words.. I must at once warn you, ho\.vever, tha.t

Erinnerungen berichtet, beriL mte deutscbe Rechtslehrer so etwas wie einen Sport

daraus, bei jeder Gelegenheit zu betonen: dass Gerechtigkeit natiir1ich nicht cIas

Geringste mit Recht zu tun habe. Die Frucht war die Lehre von dcr entscheidenden

rechtlichen Potc-nz der UEntscheidung ', der DezisioDismuf1 Carl Sclunitts, des

Kroqjuristen der brauncn Diktatur.'

A good account of the dissolution of German Jibera1isro by legal positivisnt will

b found in John If. Hallowell, 77le Decline l!f Liherali."1ll as lzn Ideology will, P(lrliculttr

Riferenc 10 GmlJQ1J Polilko-Lcgal 'l1,(JU, "', Bcrkdt'Y) Calif.., 1!)4:.t.

II H I

The E17'ors of Constructiz,i.sm

the ronscrvativ.es alnong you ,vho up to t11is point may be rqjoicing,

\viJll1Q,\\' probably be disappointed. TIle proper conclusion from the

considerations I have advanced is b}' no means that ,ve may con-

fidr.ntly accept all the old and traditional values Nor even tbat there

arc any values or tnoraJ principles, ."vhicll science may not occasiotially

question. 1'hc social SCiClltist \vIlo endeavours to undel"'stand how

society functions, and to cliscovcr where it can be improvcd must

(:laim the right critically to examinc, and even to judge, every

single value of Ollr society. 4I'lle consC'{lul nce of what I have said is

nlerely that "ve t.an never at one and the same ti-mc question all its

vaJ.u.cs. Such a O bsolute doulJt could lead only to the destruction of our

<:iyi1isa.t.ion and - in \iicw of the numbers to \vhic.h economic progress

llas anowed the llUlnan raCt to grow - to extreme misery and starva-

tjon. ( omp1ete abanclonrnel1t of all tradit.ional values is, of course,

inlposs;J)lc; it ",,'ould make Inall illcapable of acting. If traditional

and taught values iormed by man in the -:ourse of the evolution bf

civilisation \'V.ere renounced, this could only Inearl faIling back on

those instinctive values, whicll nlan developed in hundreds of

thousands of years of t.ribal life, and which are no\V probably in a

measure innate. Tllese instinctive values are often irreconcilable

vith the basic I)rinciples of an open society - namely, t11e application

of the same rules of j LIst eonduct to our relations with all other men

- which our young rcvolutiol1aries also profess. The possibility of

tlcll a great soci.ety certainly docs not rest 011 instincts, but on the

goverl1ance of acquired rules. TIns is th,e discipline of reason. 24 It

curbs instinctive impulses, and relies on rules of conduct which have

originated in an interpersonal mental process. As the result of this

process, irl tlle COllfse of tin1e all the separate individual sets of

values beconle slowly adapted to each other.

'lle process of th evolutiol1 of a system of '\'alues passed on by

J. ultural tran missiorl Illust iU1plicitly rest on criticism of individual

values in the light of tllcir consistency, or compatibility, vvith all

ot11er values of society, which for tllis purpose must be taken as

g--iVf:'Jl r nd undoubted" The only standard by which we can judge

particular values of our society is the entire body of other values of

1hat sanJe society. More precisely, the factually existing, but always

q, 'l'h( term n.alSOD i3 here used in the sense explained by John Lockc, Essays on the Law

,,( .!Yrllll7.c, ( d. \\1. von Leyden, Oxford, (954, p. 11 I: 'By reason, however, I do not

think j inc;,\nl hc rf: lhe ff.1ocu1ty of the understanding which forms trains of thouRht

a )d cl.=dur('S proo[C{, bet cp.rtain definite jlrinciples of action from which sprinK all

"t..ltLf. and wltatevt.; i5 nlo e ssar)" for th : proper moukii.u of lno1"al :

1 1 91

The ""'r{)rs qt" ( ,'011.\'1 rllr:tini.\"1f1.

imperfect, order of ac.tians ptOd1U'(,(1 by obedience to these valu{ 5

provides the touchstone for evaluation. B(.( 'aUSf' prcvajling syslen.ls of

morals or va]ues do not always jV(' 11 nanl biguous anS\,\7:crs to the

questions whicll arise) but often pr()v (0 hc' i.11(ernaIly corltradictory

,vc are forced to develop and rcfine Huch Jnoral systclns corltinuously.

We s11all sometimes be constrained to Su'lTificc sorne moral value, but

always only to other moral values \vhic.:J L \V(. regard as superior. "\' e

can110t escape this c110ice, because it is p;u'l of ail indispensabl(.

process. In the course of it \VC are Gt'rlHill to rnakc many mistakes,

Sometim{ s \vl101c groups, and perhaps ('utj1'f' IHltioI1S, ""\l.HI decline,

because they c.hose Ule wrong values. l (' 'sol) has to prove itself in

this mutual adjustment of given values, fiIHllt111.st perform its rnost

important l)ut very unpopular task - narntly, to point out tl1e inner

contradictions of our thinking and feelin!-{.

111e picture of mall as a being \VIIO, thank:.; to Ius reason, call rise

above the values of his civilisation, in order to judge it fronl the

outside, or from a higller point of vic\v, is an illusion. I t simply must

be understood that reason itself is part of civili ation, A]l \ve can

ever do is to confront one part ",rith the other parts. Even this

process leads to incessant movement, "vhich may ill the very long"

course of time challge the wllole, But sudd.en complete reconstruction

of t11e whole is not possible at any stag( of t11e process, because we

must al\vays use tIle n1aterial that is available, and whicll itsclfis tIle

integrated product of a process of evolution.

I hope it Ilas become sufficieIltly clear that it is not, as may

sometimes appear, the progress of science \vluch threatens our

civilisation, but scientific error, based \1sually on the presumption

ofkno,vlcdge which in fact vve do llot possess. l"';his lays upon science

the responsibility to n1ake good the harm its representatives have

done. Gro th of knowledge produces the insigl1t that we can now

aim at the goals which th.e present state of scierlce has brought

within our reach thanks only to the governance of values> which

we have not made, and tIle significance of "vhich '\'\'C still only very

imperfectly understand. So long as \ve cannot )..-ct agree on crucial

questions, such as whether a cOInpetitiv( n'la1"ket order is p08si ble

,vithout the recognition of private several property ill the instruments

of prod ucti 011, it is clear that ,ve still understand only very imperfectly

the fundamental principles on ,vhich the existing order is ba.sed.

If scientists arc so little a\vatc of the responsibility they llave

incurred by failing t conlprehcnd the role of values for tllC prcscrva-

[20]

The Errors of Constructivism

tion of the social order, this is larg-ely due to the notion that science

as suell 11as l10tlling to say about the validity of values. 1'he true

statement that, from our understanding of causal connections be..

twecn facts alone, \VC can derive 110 conclusions about the validity of

values, llas l)een extended jnto the false bclief that science l1as nothing

to do with va]ues.

'This attitude sllould change immediatcly scientific allalysis sho 's

that th( existing Hlctual order of society exists only because people

accept certain values. "Vith regard to SlICh a social system) we cannot

even rnakc statements about the cficcts of particular events WitllOUt

assunliug that certain tl0rn s are being ger1crally obeyed. 25 From

suell prernlses containi.ng values it is perfectly possible to derive

conclusions ahout the compatibility, or inconlpatibjlity, of the

Vari01.1S values presupposed ill an argun1ent. It is tllerefore incorrect

i froDl tJ1C postulate tbat science ought to be free of values, the

conclusion is dra\vn that ,vithil1 a given system problems of value

cannot be rationally decided. vVhen ",'e have to deal with an ongoing

process lor tI1e ordering- of society, in \Vl1ich most of tIle governing

valucs are unq uesiioned, there \"rill often be only one certain answer

to partic.ular questions that is compatible vvitll the rest of the

system. 26

25 Cf. in this connection the arguIn nt in H. ,A.. L. Ifart, The Contept of Law, Oxford,

Ig61) p. 188: ;Our concern is 1,vith social arl'angen cnts for continued existence, not

with those of a suicide club. \Ve- ,vish to know w'hether, an-tong these social arrange..

m nts, there are sOlne , bich are il1uminalingly ranked a3 natural laws discoverable:

by reason, and what their relation is to hurna.n law and morality. 1:'0 raise this or any

other question haw n\en would H\'e together, we m.llSt assuD1e that their aim, generally

speaking, is to Jivc. Froln this point the argwnent is a simple one t Reflection on some

very obvious gcn( ralisatioos - indeed truisms - conccrniog human .paturc and the world

in ,,,,h.ich men live, show that as long as they hold good, th rc are certain ruleg of

conduct ",'ruch any social organisation nlust contain if it is to be viablc4' SimiIar

considerations of an anthropologist are to be found ill S.. F. Nadel} .Anthropology and

lvlodern Life, Canberra, 1953, pp. 16- 2.

26 My position in this respect has become very Jnuch like that which Luigi Einaudi has

well described in his introduction to a book by C. Bresciani- TWToru "'weh I know

only i11 its German translation, Eirifiihrung in die I-Yirlschafe.rp0 litilc, Bern, J 948, p. 13.

He relates there how he used to believe that the economist had silently to 'accept th

goals pur:;ucd by the legislator but had become increasingly doubtful about this" and

might some day arrive at the conclusion that the economist ought to combine his

task of a critic of the means with a similar critique of the ends, 3.ud that this IllcLY

prove as much a part of science as the investigation of the means to which science at

present confinc--s itself, He adds that the study of the cor1"cspondencc of means anti

( ncl!; and of the logical consistency of the posited ends Inay be much. m()r diflicult lhan.

lIut c rtaiIlly of equal moral value to, all congid( rations of the acc<"ptct'Uility and

(:\'a1u tion of thr. ( pantte C"ncis.

I!.!J)

The Errors of COllstructiz'ism

We l1ave the curious spectacle that frequently the very same

fl icntists, "rho particularly emphasise the wert/rei (va.lue free)

,.haracter of science, use that science to dil)credit prevailing values as

t he expression of irrational emotions or particular material interests.

Snell scientists often give the impressiorl tl1aJ the only valU( judg-

Inellt that is scientificaJly respectable is the view that our values have

no value. l'his attitude is tllerefore the result of a dcfcctive ul1der-

standing of the connection behvecn accepted values and the pre..

vailing factual order.. 27 All that we can do - and must do - is to test

each and every value about vvhictl doubts are raised by the standard

uf other values, which ,ve can assume that our listeners or readers

hare "vith us. At pres nt the posttuate tl1at \VC sllould avoid all

value judgments seems to me often to have bCl On1( a nlere excuse of

llH.. tirnid, \vho do not wisll to offend anyone and thus conceal their

})rc[crences. Even more frequently, it is an attempt to CQI1Ceal from

themselves rational comprehension of the choices we 11ave to make

hetwcen possibilities open to us, which force us to sacrifice some

a.ims \v.e wish also to realise.

Onc of th.e noblest ta.sks of social science, it seems to me, is to

show up clearly these conflicts of values.

].'hl1s it is possible to demonstrate that 1Nhat depends on the

tu'( eptance of values, which do not appear as consciously -pursued

aln\S of individuals or groups, are the very foundatiohS of the factual

ot'(h r, ,.yhose existence we presuppose in all our individual

t ndcavours.

-J.7 A good illustration of what is said in the text is apparently offered by the lectures of

( unnar Myrdal on Objer.tivity in Social Research froIn which The Tirr.es Literary

Stt/ )le1Mn' of 19 February 1970 quotes definition of 'scietitific objectivity' as the

rr. dng of the student from C (I) the pow rful heritage of earlier 'Wl1 tings itl his field or

inc]uiry, ordinarily cuntaining nonna tivc and teleological notions inherited fr.om past

eIu:rations and founded upon the metaphysical moral philosophies of natural law

and.. utilitarianism from ,.vhich aU our social and economic theori nave branched

()ft; (2) the influence of the entire cultural, social, economic, and politicaJ Jnilieu of

lhl' ociety where he lives, works a.nd earns his living and his st.atus; and (3) the

influence stemming from his own personality as rno!d(rl not only by traditions and

cnviromncnt but a1so by his individual history, constitution and inclinations. 2

I 1

CHAPTER TWO

The Pretence of Knowledge.

The particular occasion of this lecture, combined with the chief

practical probleln which economists have to face today, have made

tIle choice of its topic aln10st inevitable. On the one 11and the still

recent establisllment of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic

Science marks a significant step in the process by which, in the

opiniorl of the general public, economics has been conceded some

of the digtIity and prestige of t11c physical sciences. On the other

hand, the economists are at this moment called upon to say how to

extricate the free world £ronl the serious threat of accelerating

inflation Wllich, it ffil1St be admitted, has been. brought about by

policies ,vhich the majority of economists recommended and even

urged governments to pursue. We have indeed at the moment little

cause for pride: as a profession we have made a rness of things.

It seems to me tha this failure of tl1e economists to guide policy

more successfully is closely connected with their propensity to imitate

as closely as possible tIle procedures of the brilliantly successful

physical sciences - an attempt which in our field may lead to out-

right errOT. It is an approach which has come to be described as the

'SCiClltistic' attitude - an attitude ,vhich, as I defined it some thirty

y.ears ago, 'is decidedly unscientific in the true sense of the word,

since it involves a mechanical and uncritical application of habits of

thought to fields different from those in which they 11ave been

formed).l I ,,,,ant today to begin by expla. ning how some of the

gravest errors of recent economic policy are a direct consequence of

this scientistic error.

The theory \vh:ich h.as been guiding monetary and financial policy

· Nobel Memorial Lecture, delivered at Stockholm, 1 I December 1974, and reprinted

froJn us Prix Nobel en 1974, Stockholm, 1975.

t Sci nti nl and the study of society', Economica, vol. IX, no. 35, August 1942, reprinted

in 'rJu nCJImlcr-Revolution t!f Sde7Ke, Chicago, 195 2 .

[23]

The Prrtence of }"'nou.;le lJe

during the last thu"ty years, and \"]1ich I contend is largely tIle

product of such a mislakcn COIJCl1Jtl.un of the proper sciel1tific.

procedure, consists in the assertion that tllere exists a simple positive

corrclatioll bet\\'een total employment and the size of ll1e aggregate

delnal1d for goods and services; it leads to tIle bclief that ,ve can

perlnancntly assure full emplo)rrnent by mainta.ining total 1110ney

expenditure at an appropriate level. i\lnong tIle various lileorics

advanced to account for extellsive Ullemployment, this is I)robab1y

the only one in support of\vh.ich strong quantitative evidence can be

adduced. I nevertheless regard it as fundarnentally false, and to act

upon it, as \\'e no\v experience, as .very harrnful.

'This brings me to the crucial issue. U nl1 ke the position that exists

in the physical sciences, in economics al1d other disciplines that

deal with essentially complex phenomena, the aspects of tIle events

to be accounted for about ,,,,hiel1 \ve can get quantitative (lata are

necessarily limited and may not include the important ones. While

in the physical sciences it is generally assulned, probably witll good

reason, that any important factor whicl1 determines the observed

event.s will itselfbe directly observable and measurable, in t]1e study

of such complex phenomena as the market, Wllicll depend on tl1e

actions of many individuals, all the circumstances \Vl1ich ,viII

determine the outcome of a process, for reasons whic}l I shall

explain later, will hardly ever be fully known or measurable. And

while in the physical sciences the il1vestigator will be able to measure

what) on the basis of a prima facie theory, he thinks important, in the

social sciences often t11at is treated as important Wllich happens to be

accessible to measurement. This is sometimes carried to the point

where it is demanded that our theories must be formulated in such

terms that they refer only to nleasurable magnitudes.

It can llardly be denied that such a demand quite arbitrarily

limits the facts which are to be admitted as possible causes of the

events which occur in the real world. This view, ,-vhich is often quite

naively accepted as required by scientific procedure, has some

rather paradoxical consequences. 'vVe know, of course, wit}} regard

to the market and similar social structures, a great many facts

which \ve cannot measure and on which iIldeed we have only some

very imprecise and general information. And because the effects of

these facts in any particular instance cannot be confirmed by

quantitative evidence, they are simply disregarded by those sworn to

admit only wl1al they regard as scientific vi(len<.'( : tJu'y tlu.'I't'ltpOU

r 41

The Pretence of Knowledge

happily proceed on the fiction that the factors \vruch they can

nlcasurc arc the only ones that are relevant.

Th.e correlation between aggregate demand and total employment,

for instance, may only l)e approximate, but as it is tIle onry one on

\>vhich \ve llave quantitative data, it is accepted as the only causal

connection that counts. On this standard there may thus well exist

better 'scientific) evidence for a false theory-, wlueh \vill be accepted

bec.ause it is more scien tific:', than for a valid explanation, \vhich is

rt:jcctcd because there is 110 sufficient quantitative evidence for it.

Let me illustrate tllis by a brief sketch of what I regard as the chief

actual cause of extensive unemployment - an account Wl1ich \vill also

explain ,vby such unen1ployment cannot be lastingly cured by the

inIlationary policies recommended by the no,\, £'1shionable theory.

"I11is correct explanation appears to Ine to be the existence of

discrepancies betvvccn tIle distribution of dClnand among the

different goods and services and the allocation of labour and other

resources among the production of those outputs. 'ATe possess a fairly

good 'qualitative) knowledge of the forces by ",,-hich a correspondence

between demand and supply in the different sectors of the economic

system is brought abOtlt, of the conditions under which it will be

achieved, and of the factors likely to prevent such an adjustment.

The separate steps itl the account of this process rely on facts of

everyday experience, and few wIlo take tIle trouble to follow the

argument will question the validity of the factual assumptions, or the

logical correctness of the conclusions drawn from tllem. We have

indeed good reason to believe that unemployment indicates that the

structure of relative prices and \vages has been distorted (usually by

monopolistic or governmental price fIXing), and that in order to

restore equality between the demand and the supply of labour in all

sectors changes of relative prices and some transfers of labour will be

necessary.

But when "\ve are asked for quantitative evidence for the particular

structure of prices and '\vages that viould be required in order to

assure a smooth continuous sale of the products and services offered,

we must admit t11at \ve have no such information. 'Ale know, in other

words, the general conditions in which what we call, somcw}lat

tIuslcadingly, an equilibrium will establish itself: but we never know

what tllc particular prices or wages are which would exist if tht

ularket were to l}ring about such an equilibrium. We call mereIy

ay what the ( (Hll1itiunR arc in which we '<ln eXI1cct t.h( mark('i '0

I !)I

The jJr!!ll!/lCe ql' J{nowledge

establish prices and wages at vvhich demand ,vill equal supply. But

we can never produce statistical inf()rmation wllich would shovv how

mucll the prevailing prices anti \vages deviate from those whicll would

secure a continuous sale of tIle current supply of labour p TI10U.gh this

account of the causes of unemploynlent is an en1pirical theory, in the

sense that it migl1t be proved false, for example if with a constant

money supply, a general increase of Yvagcs did not lc"cl to un-

employment, it is certainly not the kind oft11eory \vhich \ve could use

to obtain specific numerical predictions concerning the rates of

\vagcs, or thc distribution of labour, to be expected. ......

Why should we, hO'\iever, in economics, llave to plead ignorance

of the sort offacts on ,vhich, in the case of a physical theory, a sciellti:it

,vould certainly be expeeted to give precise informatiol'l? It is

probably not sltrprising that those impressed by the example of the

J)hysical sciences should fInd this position vcry unsatir;factory and

should insist on the standards of proof which. t11ey find there. rrhe

reason for this state of affairs is the fact, to \-\r}lich I have already

bricfly referred, that the social sciences, like nluch of biology but

unlike nl0st fields of the physical sciences, have to deal \vith structures

of essential complexity, i.e. ,vith structures "\\rhose characteristic

properties can be exhibited only by models made up of relatively

large numbers of variables. Competition, for instance, is a process

whicl1 will produce certain results only if it proceeds among a fairly

large number of acting persons.

In some fields, particularly \vhere problems of a similar kind

arise in t11C physical sciences, the Qifficqlties can be OVC1'COlne by

using, instead of specific information about the individual elements"

data about the relative frcquency or the probability, of the occur-

rence of t.he various distinctive properties of the elements. But this is

true only ,vhere we have to deal with \vhat }las been called by Dr

Warren Weaver (formerly of the Rockefeller Foundation), with

a distinction \vhich ought to be much more \videly understood,

'phenomena of unorganized complexity', in contrast to those

'phenomena of organized con1plexity' with vvhich ¥.'e have to deal in

the social sciences. 2 Orgal1ized complexity here means that the

character of the structures sho,""ing it depends not only on the prop-

erties of the individual clements of which they arc composed, arid

the relative frequency with which they occur, but also on the n1.anncr

2 \Varren WeaVf'I J "A quarter century in the natural scicncrst, Tilt: Jl(ltkt:/ 1l1!r l ("ltu/"tio"

Annual Report 1958, c.:huptl"'l' I, 'Science and ('olupl.."xity'"

r (.I

The Pretence of II now/edge

in vvhicl1 tIle individual elements are connected ,vitil eacll otller. In

the cxplal1ation of tIlc '\forking of suell structures we can for this

reason not replace the information about the indi lidual elements by

statistical information, but require full information about cae}l

element if from our theory \.ye are to derive specific predictions about

inclividual events. Without such specific information about the

individual clemel1ts ,.ve shall be confined to \Vllat on another

occasion I have called mere pattern predictions - predictions of

some of the general attributes of tIle structures that will forn1

themselves, but not containing specific statements about the

individual elcn1cnts of which the struetures \viII be made u.p. a

'"This is particularly true of our theories aCCOuilting for tIle deter-

mination of the systc]n of relative prices and wages that ,viII form

themselves all a well-functioning n1arkct I11tO the determination of

these prices and wages there ,viII c IJter tile effects of particular

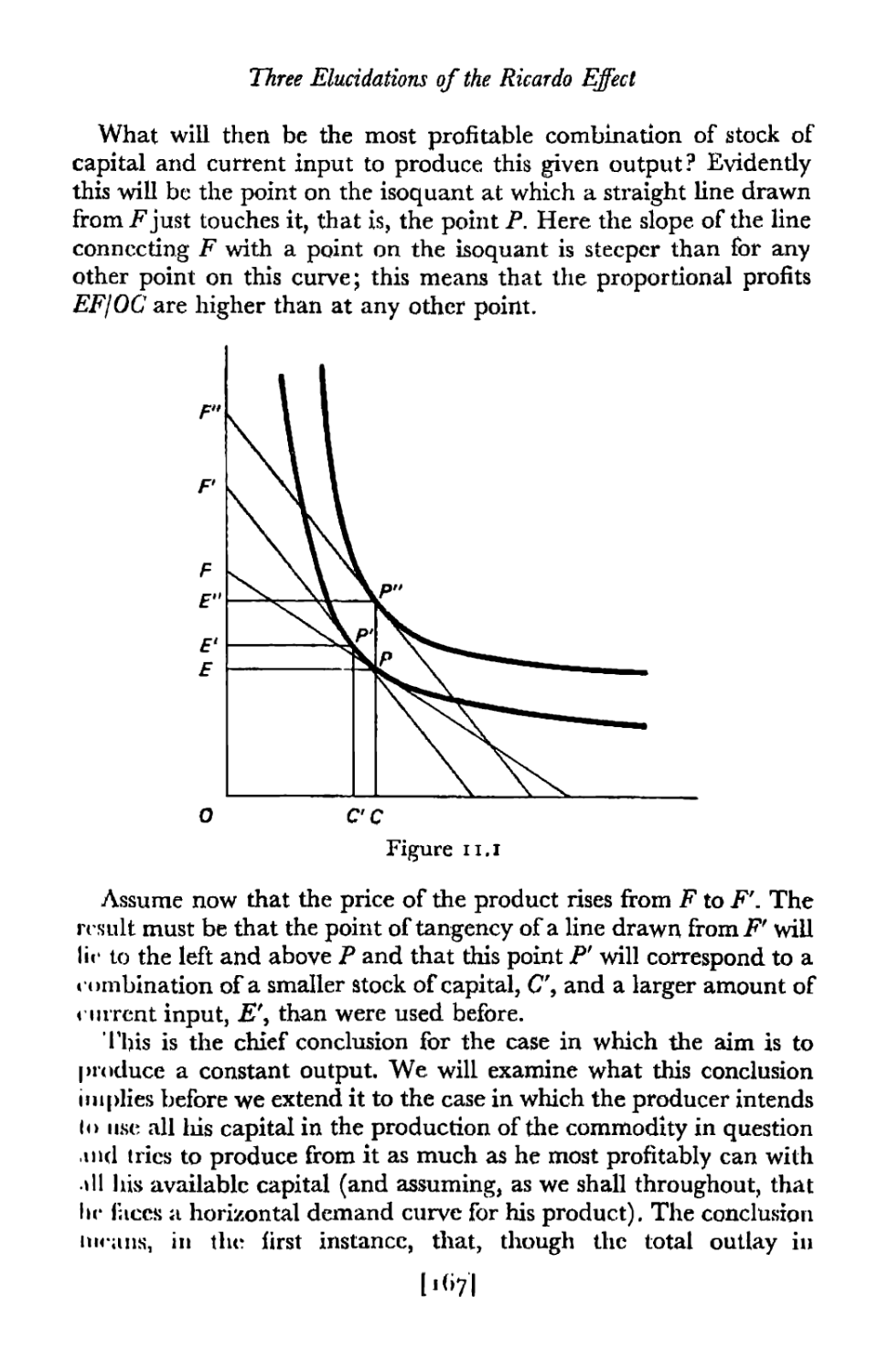

information possessed by everyone of the participants in the market