Похожие

Текст

Sir John Bo>rdman "

l mroln Profc,,or of Cl.l"Jcal Archaeology .nul An

.l l (.)xford Umvcnny Jnd .1 fellow of the llnu'h Ar.1c.kmy

lie.• \\.1\ A\\lfitam Dm..·nnr of the Rnn~h School at Athens.

then Av~l\t.Ult Kccpn Jl dll· A'hmolcan Mu\CUI11, Oxford.

before becomin g a Rc.-. u .kr 111 Cl.t\\tc:al Arch.u:oloAY m the

Unlvt. 'f\ll). th~n Prote\''iOf. lie h,I\CXCI\':ttcd 111 Crete. Chios

<llld Lahy.1 . I Its other h.uu.lbuoJ...~ .1rc dt:\"(Hnl to ·ltltn1ian Rt·d

f-,_~urr I -d~t·J (volume' on thl· Archaic and the Cia,,tcal).

.-lthnJidll Rltuk F({!urc I ·ll.\f5 .1nd Grn:k .Swlfuurr - Tltt• Archau

Prrhld. He J\ also the author ofCrrrk .- lrtm du= World ofArt

'ene'; cx<.:.wanon pubhouon'; Tlu• Grab Ol•rrsr,Js: Tlte

J>~~rtllnl(l/1 ""d its SmiJ'flm•. (: and several book' on .mncnt

gL'Ill' .1nd finger nng~.

WORLD OF ART

I h1' t:unml~ 'icnco,

prondl'\ tht· WldC4it JVJ1i.1bk

r.1ngc of lllll\tr.ucd hooko;; on art m .t!I H\ .l\pcn~.

I f you would hlo..t• to rt'n'l\"C a compk·tt' l1 \t

of utk\ 111 pnm please ''rue to·

TIIA\11\ -' ' D I ILD\0'\

30 Bloomdnu~ Stn.·ct, London \' <. 1R Jf~P

In tin' Umtcd St.ut·, plc.a'ic wntt· to:

THA\H<i AI\, I) IH U\0'\; I'(

)00 llfth Avt'IHIC, Nt•w York, Ne\\ Vor!... 10110

1196

$ 1.48

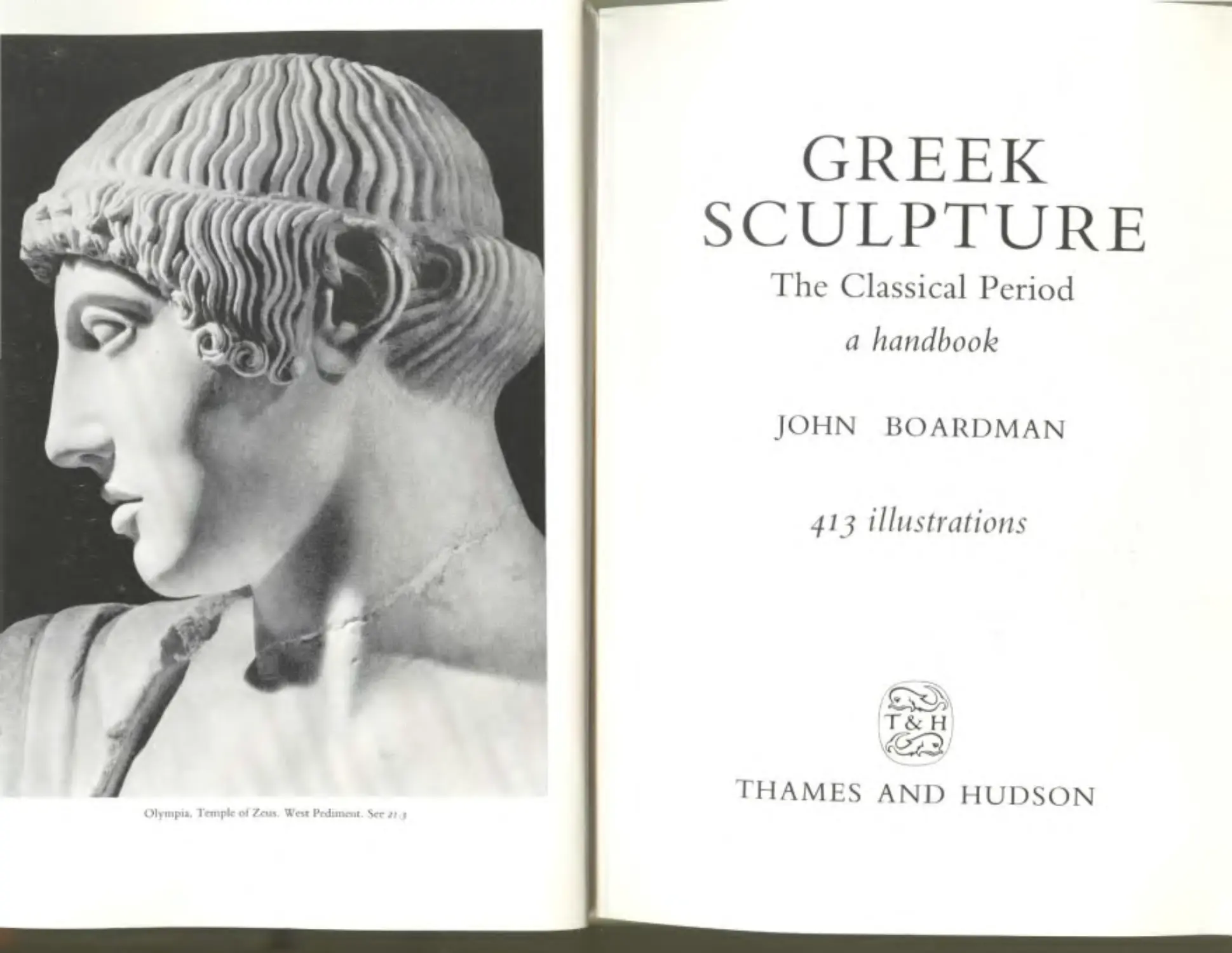

O lymp1a, r tmplc: ofZcus. Wtsl Ptdimc:nL See 1 I .J

GREEK

SCULPTURE

The Classical Period

a handbook

JOHN BOARDMAN

413 illustrations

~

@)

THAMES AND HUDSON

. '1uy ft'P)' ~~.f tlru ltt,1,k iuutd by tlupublidra •h a

p.Jptrb.J,k j, _,,,ilf Jll~lt'" ,,, tlrt n't~dllum tlr.Jt tt ~lr.Jll PWI,

by ll'ay pf1raJ1• , , , ,,,Ju·ru·ut, be- /rut, rn,,M, luml out

11,- otltt·ru.•r.•r or.ulatnl, 14'Uih'UIIIrc puh/r_•ltrr's prwr

wmmt, ;, arry}~''"' ~~ bmdur.l! ,,,- "'''tr M~ratlran tlrac

m rdritlf it r• fiU/IIHJrn/iJ/111 ll'lllliJUI .J mm/.Jr ltlW/rtwu

mcluJm.l! tlu·tt .,.,,,,J, l~t·ru,l! "''l'tHtd ,,, a .cuhJtqumt

puulw_<t>r .

c 19,il5 Tlwmn ,,.J li111IW11 l .ltl, l .tmrlmr

CCirrC'(tnl rdrllott H)() I

Rrt~rmlt'llt"9l

1111 ri(!hU r('\l'11'f'tl. St~ 1''"' 4tln~-~ JlUbliwtitm ttMy l1f

rrpr 11ducnl c~r tmmmilffll w ""Y }''"'''''by"'')' mra~u,

efrcmmir M ml'flratlical, mdwlm.\! J'lmtc'n'J'Y• ruo~dw,l!

or- 1111 y u~/i"'n!lfhllf -~' '',-_".!!<" aud rflrtn•al ~Y-'It'm, wrtlwur

p4-·nui~~i1m 111 "'"'"'.~! .frMII tlu· ruMr<lu ·r

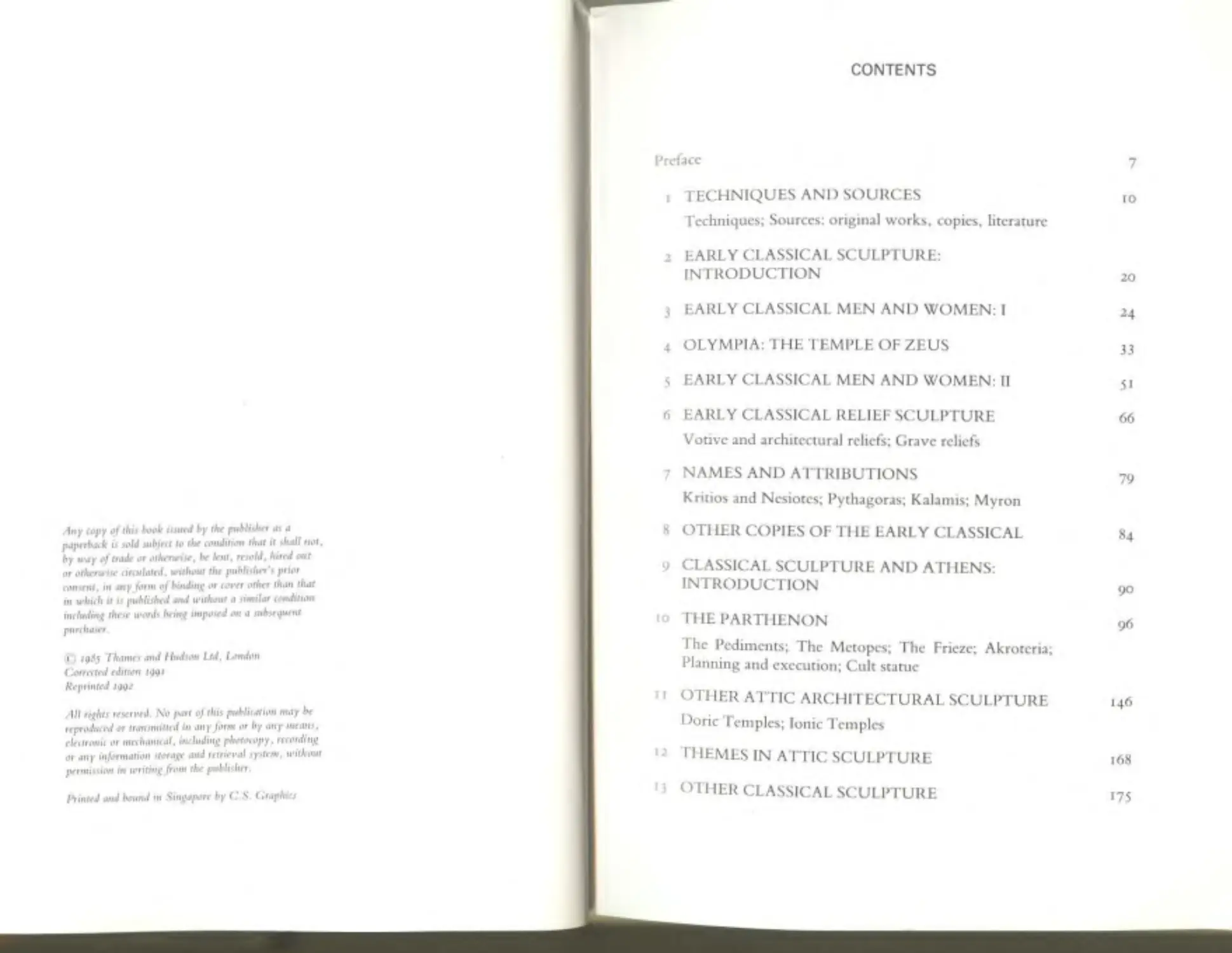

CONTENTS

Preface

TECHNIQUES AND SOURCES

Techniques; Sources: orig inal work s, copies, literature

2 EARLY C LASSICAL SCULPTURE:

INTRODUCTION

EARLY CLASSICAL MEN AND WOMEN: I

4 OLYMPIA: THETEMPLE OFZEUS

EARLY CLASSICAL MEN AND WOMEN: 11

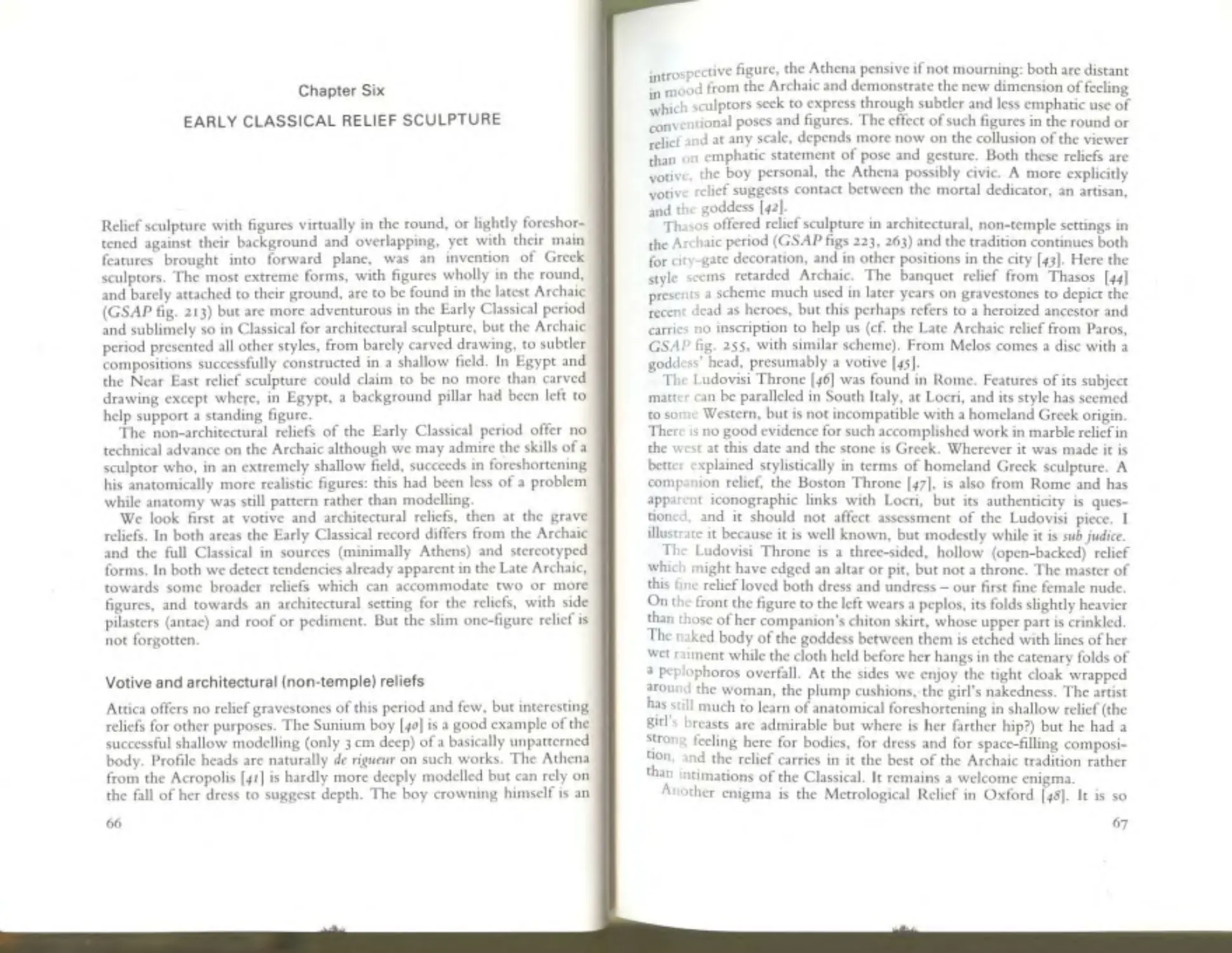

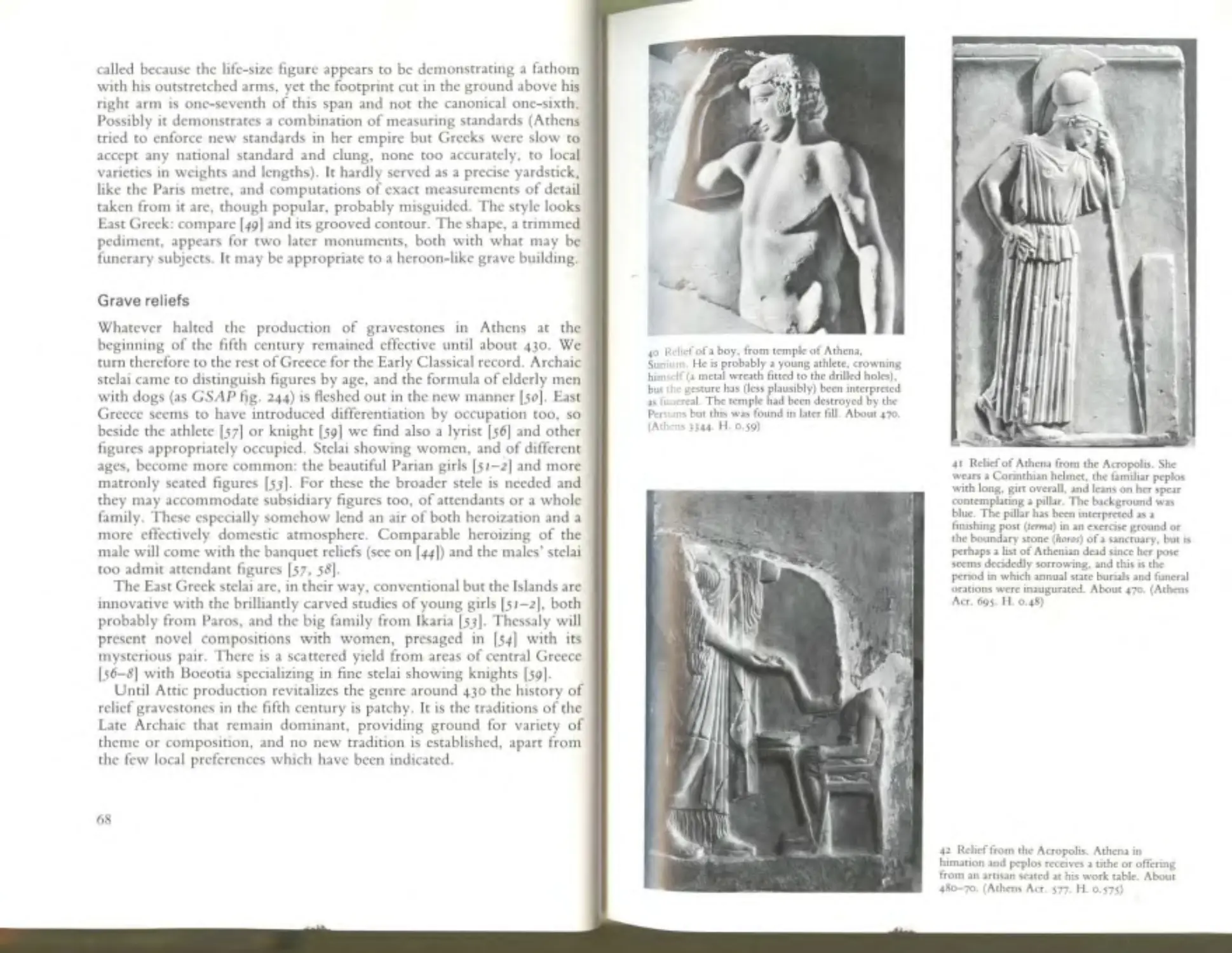

6 EARLY CLASSICAL RELIEF SCULPTURE

Votive and architectural reliefs; Grave reliefs

7 NAMES AND ATTH.Il:3UTIONS

Kritios and Nesiotes; Py thagoras; Kalami s; Myron

8 OTHER COPIES OF TilE EA RLY C LASSICAL

J C LASSICAL SCULPTU RE AND AT! lENS:

INTRODUCTION

10 THE PARTHENON

T h e Pediments; The M etopc s; The Frieze; Akroteria;

Plannin g and execution; Cult statue

Ir OTI IER ATTIC ARCI IITECTURAL SCULPTURE

Dori c T e mples; Io ni c Temples

r~ THEMES IN ATTIC SCULPTURE

' 3 OTHER CLASSICAL SCULPTURE

7

10

20

33

66

79

g6

J68

175

14 OTIIER C LASS ICAL RELIEF SCULPTURE

Attic grave reliefs; N o n-Attic grave reli efs; Votive

reliefs; Record reliefs

15 NAMES AND ATTRIBUTIONS

Phid1as; Po lyclitus; Krcsi la s; Alkamenes; A go rakritos;

Kallim ac h os; Lykios; Strongylion; Paioni os

16 OTIIER COPIES OFTi lE CLASSICAL

17 CONCLUSION

Abbreviations

Notes and 13 ibli ogr a phies

Index of lllu st ration s

Index of Artists

Acknowl ed gments

General Ind ex

203

213

Preface

This volume is a sequel to Greek Sculptu re, The Archaic Period (hereafter

GSAP) publi shed in 1978. The intenti o n had once been to include in it an

account of Greek sc ulpture in the co lo n ies as well as that of the Ea rl y

Classical period, but it has seemed better to deal only with the Greek

homeland, and to em brace all the r emaining fifth century BC, which

includes th e prime period of Cl assica l scu lpture in the commo n ly

accepted use of the term. Within these years Greek sculptors refined their

techniques and confirmed th eir abil ity to cre ate realistic images of the

hum an body, in action or repose, without su rrendering their profound

concern with proportion and design. Later centuries explored r ea li sm

further, and the R o man admiration for all things Greek e nsu red tha t the

idiom remained central to the future development o f Western art . T he

familiarity of the idiom does not make it easier for us to understand o r

appreciate. We do well to remind ourselves that in thi s century and in

Greece, for the first time in the histo r y of man, artists succeeded in

reconciling a strong sense o f form with total r ea li sm, that they both

consciously sought the ideal in figure r epresentati on, and explored the

possibilities of rendering emotion, mood, even the individuality of

portraiture . lt marks a crucial stage which determined that one cu lture at

least in man's hi story was to adopt a w holly new approach to the

function and expression of its VISua l arts.

This was a period of an x iety and excitement throughout the Greek

world. lt saw the threat of conquest by Persia, a democracy- Athens -

cr eating an empire and then losin g it. In Athens A eschylus, Sophocles,

Eu r ipides and Ari st ophanes w r ought the ir versions of Greek myth-

history to counsel and entertain the citizenry. llis to ry, in th e real se nse of

the word, was born, and a philosophy which explored the working of

man's intellect and not o n ly of the world around him. So far as they

could, the visual arts too answered the mood of the day, but their

message is less clearly read than the tex ts of philosophers, histor ians and

poets, and far more difficu lt to comp r ehend.

Our evidence for the fifth century is so different from that for the

Archaic period that part of the first chapter has been devoted to sources.

1t Will help explain why, in one respect, this book is not laid out in quite

7

the manner of most text-books on Greek scul pture. In these ch apters I

have rigorously segregated Roman copi es (presu m ed) of C lassica l

statues, except where their fifth-century ongmals ea~ cc rt a111ly or a~most

certainly be identified. Attempts at such tdenuficauon w tth a parucular

statue arc gene r all y found to depend on the barest m cnuon of a work

whose subject and appar ent fate see m to fit, an d attnbunons to named

scu lptors depend on mainly subjective criteria wh1ch arc themselves

dc n vcd from equall y suspect identifications. Not surpn s111g ly, there IS

virtually n ever agreement over a s in gle piece and the likelihood of

consensus over most ofthem lessens all the time. It is, ofcourse, valuable

to assemble, co mpare and identify the relations hips of copies which

a ppear to be based o n a single original. But it is the deductions fr om such

studies, leadi ng to attributions whi ch arc then use d to demonstrate the

d evelopment and history of Classica l sculpture, that s uddenly ~cmovc

the subject from th e r easonably verifiab le to the purely s pcculauvc and

poten tially mi slea ding . The sc holarly ingenu ity and t1mc s pent on su ch

attribution s tudies (Kopiwforsclumg) seems to grow as the years pass, yet

with diminishing r eturns , and is p erhaps the oddcst phenomenon 111 all

Classical scholarship. Only major new finds bring new hope. It seem s to

me wrong that such guesses should be accorded a status compar ab le with

that of discussion of origina l works, yet in some scu lpture handbook s

co pies and originals arc not even distinguished ex plici tly one from the

other. It is ver y likel y that lost works known only by name arc to be

identified in the many copies made for Roman patrons in Italy, the

Empire and the Greek East, which have su rvived, and lt I S understand-

able that scholars should attempt s uch ide ntifications, bm With such

general lack of agreement it m ay be safer to adm1t, that we_ a~c still

explo rin g the unknowablc, and we 1mpatr a. studen t s apprcc1auon of

o ri ginal works by giving them undue prommencc.. we ~ecd be 111 no

hurry to d1scovcr the whole truth, nor be too d1 sappom tcd 1f 1t eludes us.

lt has been well remarked that the only co py (zzz] which in r ecent yea r s

has been positively identified as a r esult of the find of parts of its o ri g111al

had never been attributed by scholars to its true au th or. I would n ot,

however, go to the further extreme, fashionable in som e quarters, of

seei ng as late pastiches many ge nerally accepted Class1cal o n g 111 a ls and

copies.

.

.

The o riginal scu lpture which has surv1vcd, howeve r , IS seldom the

very best. From Olympia and the P arthenon we hav e what must surely

be the best architectural scu lptures oftheir period, but the very bes t work

was in bronze and the few surviving examples do little m o re than remind

u s how much we miss. There were assuredly great works in m arble, and

some can s till be ad mired, though sel dom complete and always lacking

their original colours. We arc, as it were, trying to appreciate Shakes-

8

peare's genius as a playwnght from A1 You Like It, some sonnets and

Lam b's Tales.

The purpose of th1s volume, as w 1t h GSAP, has been to mtroduce to

the stude nt and genera l r eader what ev1d cncc we have for the appearance

and development of sculpture m the fifth century. A balance had to be

s truck between text, dlu strauon and documentation to do justice to as

much as co uld reasonably be fitted m to the 252 pages of the volumes of

this series. Figure captions therefore carry m format ion which might have

seemed otiose in the text. Measurements ar c in metres; the material IS

marble unl ess other wise stated; dates arc all BC. The photographs are

n u merous and some, perforce, small. They arc supplemen ted by

drawings made for th is book by Marion Cox. Photographs of casts have

been used where conven ient. Casts r ecord appearance acc urately.

without the blemish which often disfigures the orig inal. And in a

collection such as that of the A shmolcan Museum Cast Gallery at Oxford

it is possible to dictate an g le a nd lighting more freely than in most

museums. There are good cast ga ll eri es in Britain, n otably in Oxford and

in Cambridge, and the interested reade r may learn more from them than

from the large plates of an art book. Studio lighting does not always best

suit marble statues. For o ri gi na ls we turn especiall y, outside Greece

itself, to the British Museum, tO the Louvre, Berlin, Muni ch and Rome,

while other museums of Europe an d the United States ar e well suppl ied

with Rom an copies, but on theoe the modern restor er may have taken us

even a stage furt her from the original than had the Roman copyist.

For th1 ~ repnnt (1991) llllliOr <Orrccuom and addmons have been made

to the text md notes, notably to pp. 17 5 and 206, and fig. 134a added on

p.l74·

9

Techniques

Chapt er One

TECHN IQUES A N D SOU RCES

The work of creating a life-size marble statue, from quarry block to a

figure ready for display, is said to require the labour of one man - year.

The material may not in antiquity have seemed particularly precious -

Greece had mountains of fine white marble in Attica and the Islands- but

quarrying it took some skill, and much time and labour. Greek sculptors

had turned from the more easily worked limestones to marble in the

seventh century B c, and by the fifth century most of their work in stone

was in marble except where access to quarries posed problems or the

appetite for the best in materials was not demanding. The major

sculpture of other early cultures was sometimes of even harder material

(granite or porphyry in Egypt), but not commonly white, nor, except

for alabaster which was not often used for large figures, endued with the

potential for translucency of marble. That the most accessible of durable

stones for the Greek workshops had characteristics which lent them-

selves to the realistic imitation of human Acsh may have played no small

part in the direction, speed and success of developments in sculpture of

Greek lands in the Classical period and later.

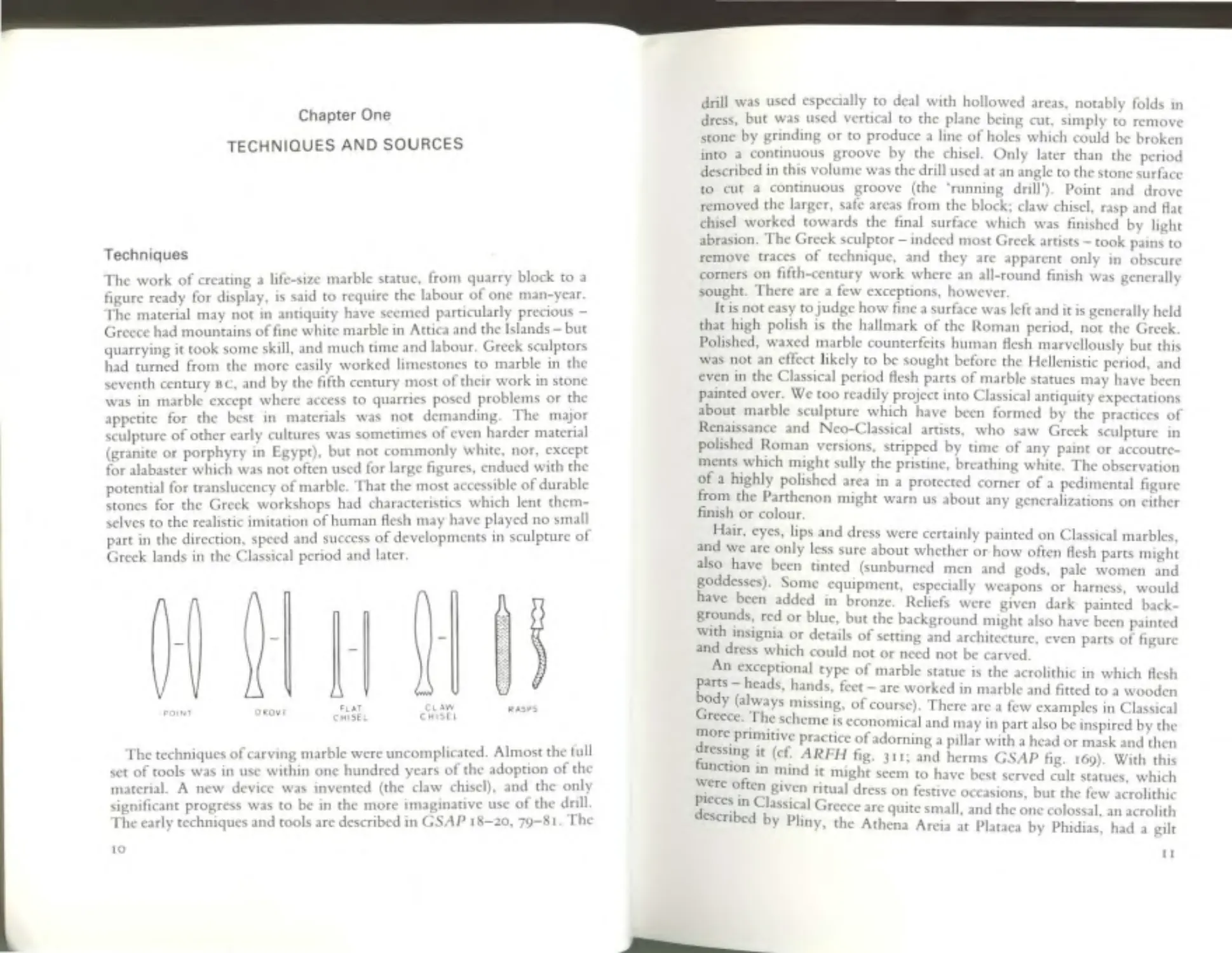

POINT

DR.OvE

FLAT

CHI5fL

CLAW

CHI~EI

RASPS

The techniques of carving marble were uncomplicated. Almost the full

set of tools was in use within one hundred years of the adoption of the

material. A new device was invented (the claw ch1sel), and the only

significant progress was to be in the more unaginative use of the drill.

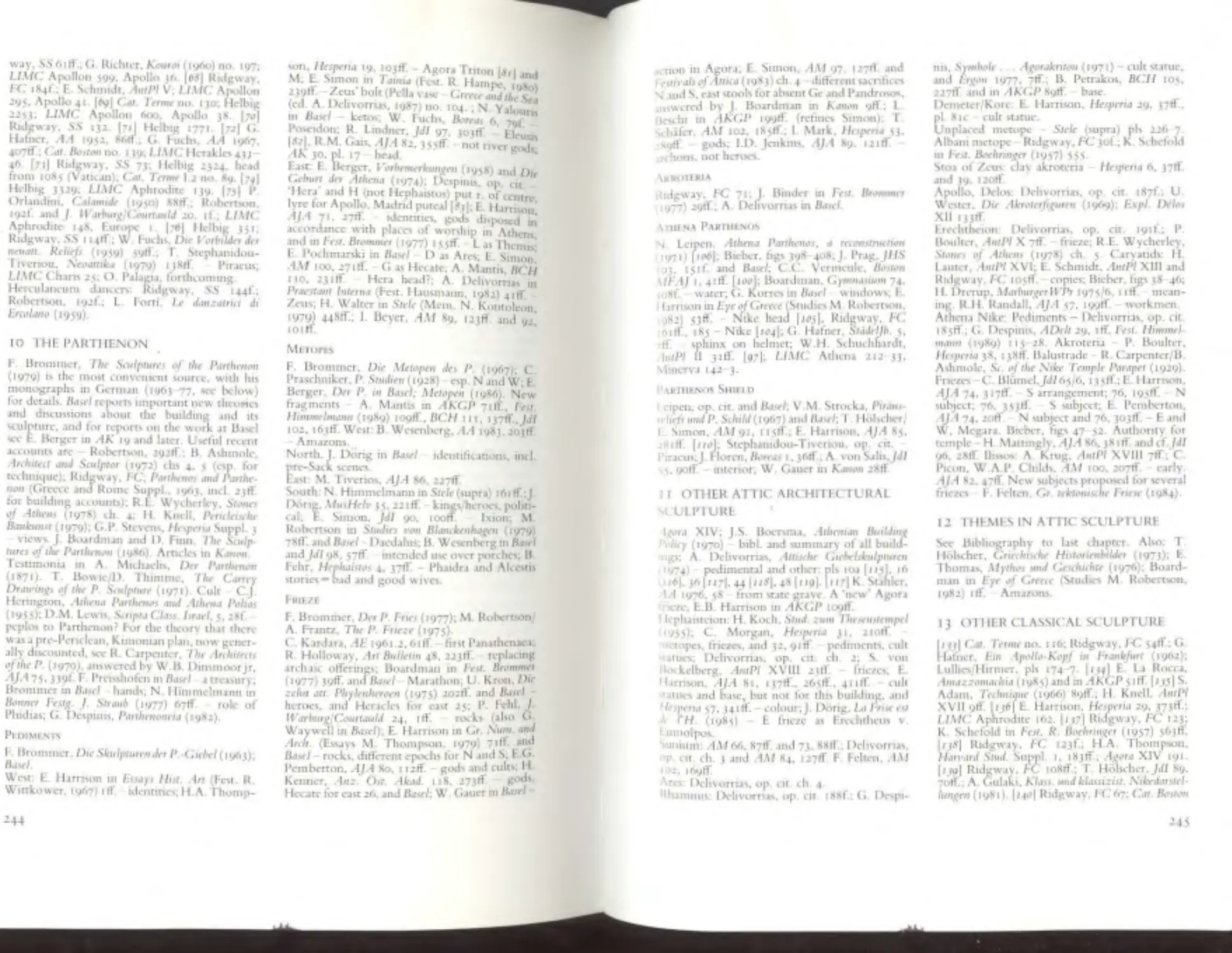

The early techniques and tools are described in GSAP I 8-20, 79-81. The

10

drill was used especially to deal with hollowed areas, notably folds m

dress, but was used verncal to the plane bemg cut, simply to remove

stone by gnndmg or to produce a line of holes which could be broken

into a continuous groove by the chisel. Only later than the period

described in this volume was the drill used at an angle to the stone surface

to cut a contmuous groove (the 'running drill'). Point and drove

removed the larger, safe areas from the block; claw chisel, rasp and Aat

ch1sel worked towards the fina l surface which was finished by light

abras1on. The Greek sculptor- mdeed most Greek artists- took pains to

remove traces of tcchmquc, and they are apparent only in obscure

corners on fifth-century work where an all-round finish was generally

sought. There are a few exceptions, however.

It is .not easy to )udge how fine a surface was left and it is generally held

that h1gh pohsh IS the hallmark of the Roman period, not the Greek.

Pohshed, waxed ~arble counterfeits human Aesh marvellously but this

was not an effect hkcly to be sought before the Hellenistic period and

even in the Classical period Aesh parts of marble statues may have,becn

pa1nted over. We too readilyproject into Classical antiquity expectations

about marble sculpture which have been formed by the practices of

RenaiSSance and Neo-Classical artists, who saw Greek sculpture in

polished ~oma~ vemons, stnpped by tim e of any paint or accoutre-

ments .wh1ch nught sully the pristine, breathing white. The observation

of a h1ghly pohshed a~ea in a protected corner of a pedimental figure

from the Parthenon m1ght warn us about any generalizations on either

fimsh or colour.

Hai r, eyes, lips and dress were certainly painted on C lassical marbles,

and we are only less sure about whether or how often Aesh parts might

also have been tinted . (sunburned men and gods, pale women and

~oddcsses). Some eqmpment, especially weapons or harness would

ave been added in bronze. Reliefs were given dark painte'd back-

grounds: red or blue, but the background n11ght also have been painted

~~~h mslgma or details of setting and architecture, even parts of figure

dress wh1ch could not or need not be carved.

An exceptiOnal type of marble statue is the acrolithic in which Acsh

parts - heads hand fi

kd·

bd

•

s, eet- arc wor e 111 marble and fitted to a wooden

G

o Y (always missing, of course). There ar c a few examples in Classical

recce. The scheme ·

·

1d

.

.

..

IS econom1ca an may 111 part also be inspired by the

;ore. prmunvc practice ofadorning a pillar with a head or mask and then

f~~~~mg ~t (et: ARFH fig. 3 I I; and hcrms GSAP fig. 169). With this

Were

10

fin 111 1~1111d lt might seem to have best served cult starues which

0 ten g•vcn ritual d e

"

·

'

pieces i Cl .

1

r ss on •esnvc occas1ons, but the few acrolith. ic

n ass1ca Greece are ·

ll dh

1

described b PI

qmte s~a , an t e one eo ossa!, an acrolah

Y my, the Athena Are1a at Plataca by Phidias, had a g ilt

II

wooden body. This is only economical to the extent that it did not

employ ivory for the Aesh parts, as did the great C laSSical chrysclcphan-

tine cult statues, like the Athena Parthcnos. We know somethmg of

smaller chrysclcpha ntine figures ofthe Archaic period (GSAP So, 89, fig.

I27) but in the C la ssical, as we shall sec, we know even less than we do of

the acroliths, but the discovery of the workshop in which Phidias made

the chryselephantine Zcus for the temple at Olympia (sec Chapter 4) has

told us something about their technique. The studio matched the size of

the temple interior (cella) in which the statue was to be placed, and the

work must have been erected there for eventual reassembly in its final

home. It appears that a jigsaw of fired clay moulds was prepared from a

full-size model, on which sheets ofgold could be pressed to their correct

size and shape. It seems, then, that they were not fastened to a fully

carved wooden body, which is what we might have expected, since this

would have rendered the mould intermediaries unnecessary. Moulds

were found for colo ured glass inlays in furniture (the Zeus was

enthroned) and dress, simple ivory tools for working gold and a

goldsmith's hammer. Pausanias' description of the statue mentioned

inlays of other metals, ivory, ebony and stone as well as figurc- pamtmg

on the furillrurc. The Aoor before the statue was a shallow pool of 01l,

and there was a similar one of water in Athens before the Athena in the

Parthenon. Both oil and water played their parts in the preservation of

ivory (to fill pores and maintain humidity) and there were probably

r eAecti ve properties too which were appreciated. In the corner of his

workshop Phidias discarded an Athenian clay mug with 'I belong to

Phidias' written on its base, an unexpected personal memento.

The finest Classical statues were executed in bronze. Techniques of

hollow casting for life-size figures had been perfected by the end of the

Archaic period (CSAP 8I) but we lack scien tific studies of most of the

very few major bronzes surviving and some details of the process still

escape us. Most large figures were cast in parts which were then brazed

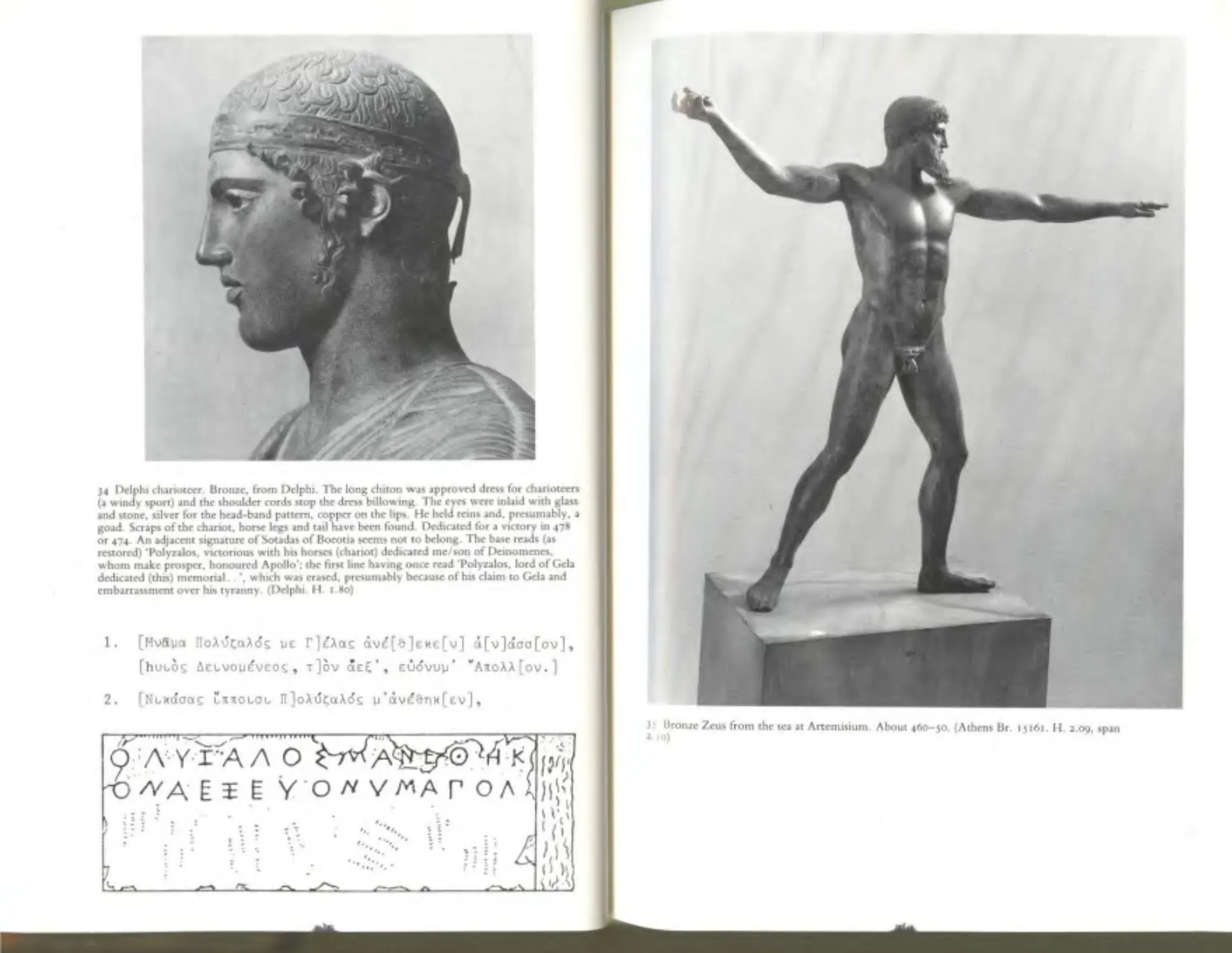

together: the Delphi charioteer [34) is in seven pieces- head, upper and

lower torso, arms, feet. The technique was especially necessary for added

spiral locks which could not easily be cast in one piece with a head: e.g .

[12]. It was not impossible, however, to cast the whole figure by the

direct method.

There were two m ethods of cast ing, both, it seems, practised in our

period although not always easily id entified and a lively debate on the

matter continues. For casting by the direct method the figure was

modelled in clay, if necessary on metal armatures. The surface was

finished, with all the desired detail, in hard wax, and the whole then

encased in clay. Core and mantle were held in position by pegs thrust

through them and the wax melted out, to be replaced by molten bronze.

12

The mantle was then broken away and the core, If poss1ble, ch1pped out.

The fimshed work needed scrapmg down and pohshing, bleJmshe&

patched, and there would often be need too for cold work with ch1scl and

graver on the cast surface. The Late Archaic l'~raeus kouros (CSAP fig.

150) was made this way, smce Its armatures and core were found still

within it. It is doubtful whc.rhcr a statue cou ld ea~ily be cast in pieces by

the direct method smce th1s would mean either cutting up the wax-

covered model, which seems wel l- nigh Impossible, or modelling each

section separately, not as a whole, whiCh could hardly either help or

please the artiSt.

The alternanve 'md1rccr' method work\ from the outside m, as It were.

Piece-moulds arc made of the modelled clay figure and lined with wax.

The figure (usually in parts) is then recast and the moulds removed so that

the wax surface can be worked over and added to (details ofhair, ere). The

figure or parts are then coated in a new clay mantle and cast 'circ perduc' in

the usual way. With the direct, there was no possibili t y ofcasting replicas,

nor are any to be found in our period. Identification ofthe indirect method

depends on observation of the inside of the fini~hed bronze, to judge

whether the wax, exactly replaced by the bronze, shows signs of having

been apphed from w1th111. The evidence 1\ ~omet1mes equivocal since, if

the ong111ai figure was carefully finished for threct casting, the wax sheet\

latd upon It m1ght well present neat underside\, observable as the inner

surfaccofthe bronze. Fingerprints or dnps 111 this position are deCISive for

the m direct method, ~moothly jointed sheets are not. The indirect method

seems attested for some Classical bronzes but if piece-moulds were used it

IS remarkable that the joints between the pieces were always so successfully

worked away (compare the network of ridges on the surface of plaster

casts ofClamca l statues, which mark the joms of piece-moulds and arc not

~Iways smoothed away). Small bronzes were cast from solid wax model~.

c1re perdue', but also sometimes from p1cce-moulds.

On the b1ggcrstatues eyes were mlaid With glass or stone· hp; mpplc~

and teeth were dJst111gu1shed from the body by 111lays 111 rud,dy c~pper or

sil ver, wh1ch could also be used for decoration on dress. The body of the

statue would appear bright and shining, 1ts tone depending on the alloy

uscdd, rang111g from red to brassy, which could be controlled. There IS

ev 1 cnce m Jnscriptl·o

c

h

·

I

f

rh

.

.

ns aor t C COntlnLJC( ,lttentJOn 0 statue-cleaners and

po IS crs m the b1g sanctuaries, and although the patina ad1111red today

ma

11

Y also have been appreciated on old bronzes by some Roman

eo ectors 1t wa

ddd

d.

•

s av01 c an removed 111 the Greek penod. ' 1 he

con ltlon 111 wh1ch R

b

£i

.

,

th

oman ronzes were ound, and Plmy s observanon

at, 111 h1s day b

Idb

pd

•

ronzes cou

e created With baumcn led eo rhe

ro ucnon of black bronzes 111 the RcnaJS~ancc and has ensu,red that this

I.J

appearance even for anctent bronzes remams more familiar to us than

that intended by the Greek metal-worker.

The model for a bro n ze was fashioned in clay and wax to the size and

detail of the desired finished statue, which was cast directly on or from it.

The marble sculptor needed guiding to the form he was trying to release

from a block ofstone. We know, fr om unfimshed statues, that the Greek

sculptor worked from all sides ofthe block, so that any detailed drawings

on its outer faces would have been destroyed im mediately, and it is

difficult to believe that they we r e r edrawn on the increasingly irregular

new surfaces as they appeared. I le could have had full-size drawings of

his figure to which he could refer and, for the stmpler, symmetrical

Archaic, this, or drawings on the block and the help of a grid

determining the placing of im portant features, would have sufficed (see

GSAP zo-1). For the more subtly posed figures of the ClaSSical period

such a process certainly would not ha ve sufficed, and we must assume

some sort of model in the round. That the statues were still designed

basically for one vtewpoint would not have much simplified the

problem. The modern sculptor m stone making a Classtcal figure works

from a full-size model made of clay or plaster. Thts figure can be read

into a block of stone by m easu r ements taken from a ftxed grid or frame

and transferred to the block by drilling 111 to the appropriate depth. Some

related process was employed in the copytsts' studto~ from the second

century B c. lt can be mcd aho to enlarge or reduce from the dimemtons of

the model. No such complicated process was in use carltcr bll[ something

similar might have been, measuring off details from a plumb line or a

triangulation of po111ts on the figure, which would have had to be

translated to its near final surface 111 the block by other means. lt has been

suspected for the pedimental sculptures at Olympia, where also, however,

it is likely that very detailed modeb. were not used, or at least not life-size.

s111ce if they had, certain anatomical or drapery errors would have been

avoided. We shall sec that the Cl,1sstcal sculptor was much concerned with

the mathematical, proportional accuracy of his figures, and the only way

of controlling this in marble would have been to work from a full-scale

model: the major bronzes, in whtch these pnnciples of proportion were

normally expressed, presented no such problems since their models were

mechanically reproduced. Whatever the ulttmate material, the Classical

sculptor probably started with a full model in clay . The large Late ArchaiC

bronzes promoted the changes in technique n11d style 111 marble, and there

are no stylistic differences between the media.

The marble statues were ca rved with their feet in one piece w ith a

s hall ow plinth which was then set in a stone base and fastened by lead or

clamps. A bronze statue had tenons cast or attached beneath the feet,

which were slotted into the base block and set with lead.

14

Sources: original works

The development of Greek sculpture in the Archaic period could be

demonstrated wholly 111 terms of surviving original wor ks. Moreover

since there must have been relatively few major works in bronze which

cou ld only exceptionally survive. the attentions of mctal-seek~rs, the

survtving record tS probably a fatrly accurate one of the full range of

quality, subjeCt ~nd style, and what we mtss most is major works in

wood wluch mtght have added something to our understanding

parncularly of the early years.

'

From the fifth century we arc still well supplied with major works in

marble, especially architectural sculpture, but we know that the most

important works, mainly individual dedications in sanctuaries or cult

statues, were in bronze or precious materials. Remarkably few bronzes

have survtved - barely a dozen -and their high qualit y brin gs home how

much poorer the r ecord ts on whtch we must judge the real sculptural

achtevcmcnts of our pcnod. Few of the surviving bronzes arc from

controlled excavations [34, 138); several have been recovered from

wrecks of .shtp s [35, 37 -9] in which they were being carried in the

Roman penod to new homes, usually in Italy. Ofthose that reached their

new homes none ha s survived: marble fares a little better. The plunder of

Gree~ works of art by the Romans began by the end of the third century

BC Wtth booty from the Greek cities ofSouth It aly, and from the second

ce ntury on Greece too lay open to Roman cupidity. An imposing list of

maJor works by named Greek sculptors which were exhibited in Rome

can be drawn up from the pages of Pliny (1st century A o) and these

represent a small proportion ofthe thousands ofworks plundered. A few

an~nnymous marbles have survived [46, IJJ-4

,

145 , ISJ?).

1

Greece Itself most of the survt vmg origina l marbles arc ar chitcc

tura • and most of these have been excavated over the last two hundred

years, the only m ·

1

.

1

.

dh.

aJor comp ex pen ously rcmammg mainly above

~roun h avmg been that on the Parthenon. There arc few orhcr origin als

rom t c Acropolis wh

01·

bb

ere, as at ympta and Delphi the empty statue

ases car mute tcsti n

h

b

'

down.

1

ony to t e many ronzcs, since stolen or melted

Sources: copies

Another tmportant b

I.

about Cla 1 1

ut perp cxmg (sec Preface) source of information

sstca scu pture is

·

·

A·

to reflect th

anctcnt coptcs. rttsts were naturally inspired

other se

1 e appearance and st yle of major works in other media or at

fifth cen~~s [7h9, 64• 102• 1 85]. lt is suspected that even by the end ofthe

r y t ere was production of reduced versions ofcult statues (sec

15

p. 214) while the pose or details of major works could be mirrored in

figures devised for reliefs or drawn on vases, or adjusted and abbreviated

to decorate jewellery and coins. The concept of an exact rcphca, at the

same or reduced size, did not come easily to the Classical artist, and the

apparent exceptions arc unusual and uncharacteristic. Since the originals

are lost these approximations to, and echoes of, the major works arc

almost impossible t o interpret, and they can never lead us to any

particularly accurate idea of the appearance of their models.

This, however, we arc vouchsafed by copies of a much later date. The

Roman interest in collecting Greek originals led to a brisk trade also in

copies of famous works. These could be in bronze but we know most of

them in marble, which survives more readily, and it is these marbles that

populate most museums outside Greece itself; not that they are lacking in

Greece and the Near East, since the fashion spread rapidly throughout

the Roman Empire, reviving significantly in periods of philhellene

emperors like Hadrian.

The courts and temples of the Hell enistic kings, as at Pcrgamum, had

been adorned with versions of Classical s tatues, but these were genera ll y

free essays in the Classical manner. The industry that se r ved the Roman

patrons produced copies as accurate as techniques and skills permitted.

This might seem the saving of our subject, but there arc problems. First,

the copies arc almost never specifically identified for us by inscription,

and in this respect our best information comes from portrait-busts

mounted as hcrms (like the Greek sacred pillars, GSAP fig. 169) and

inscribed, as [188, 246], but the original was a whole figure, which we

usually lack, and some portrait-berms ca rry demonstrably wrong or

fanciful names.

Secondly, even fewer copies can be cer tainly identified from descrip-

tions ofthem given in ancient authors, where we arc commonly given no

more than a name and a location. Thirdly, the detail and quality of the

original arc considerably impaired by the process of translating a bronzl'

into a marble, quite apart from the irreparable loss of a master's finishing

touch. Marble had not the tensile strength of bronze, hence the struts.

pillars and tree-trunks introduced to strengthen the figures; e.g . [6o, 6z-

J, 66-70, 72, ZZJ, ZZ7-J7l· Pose may be adjusted for the same reason

and Imsunderstanding of the dress or attributes ofthe original could lead

to misleading errors. Technical details may often betray the period it·

which the co pies were made because they differ from the origina

treatment and from that of other periods of copying. Fourthly, heads o

attribute> could be transposed from one type to another, just as many

C lassical type could be used as base for a Roman portrait head. Whet

only one or two apparent copies arc preserved these shortcomings mus '

leave us very uneasy about their value as eviden ce for any C lassica

10

origmal. Where several coptcs agree closely with each other in both size

and detail we may feel more confident that they reflect an original with

some accuracy. Finally, however, it is left to our own judgement

whether the original of such copies was created in the Classical penod,

when, and even by whom. lt IS becoming mcrcasingly clear that the

Roman ;rudios could turn Out Classicizing pastiches which can only be

detected through what we judge to be mtcrnal styli stic anachronisms or

inconsistenCies, or on technical grounds. There ar e many original works

in a plau~tblc C las.si;al style i~1 various media from the first centur y o c,

and the Neo-AttJC studios tn Greece produced relief-decorated vases

and slabs with figures. based on fifth-century origin als, wh1le elegant

ArchaJsmg, swallow-tail folds and the hkc, became increasingly fashion -

able. These are all easy to detect, however. Greek artists workmg in

Italy, like Pasnclcs and Stcphanus, could produce original works in the

Classical style, and it is possible that we could sometimes be misled by

statues and rchcfs from their studtos . lt was sometimes the same or

neighbour studios that were doing the copying of Greek originals, and

the late cr eations and pastiches could themselves be copied.

There are two other miniatunst sources of copies of Classical figures.

Statues of gods or heroes often formed the subject of intaglios for gem-

stones ofthe first century BC and later. Some give finely detailed versions

of heads [IOJJ. most arc roo small or too freely interpreted by the

engraver to be of positive value, and they arc never identified on the

stone. Problems arc posed too by Neo-Classical versions of the later

ctghtecnth and nineteenth centuries which are sometimes very difficult to

detect. And on Greek coinage of the Roman pcnod famous local statues

arc sometimes represented: GSAP figs 125, cf. 126, 185; [180-2, zo

7bj.

fhese have the merit of being easily placed, but a local moncycr was not

bound to favour a local t ype, the scale is minut e and detail mim 111 al.

All these comidcrations have led to my cautious presentation of the

cvtdencc of COp ies, as explained in the Preface.

13

1

romc copies of statues could be made by castmg from the onginal

w1t1ptcccmoId· h

·

d.

hb-

u s m t c 111 trcct .method, but this seems very rarely to

avc ccn p

dMbl

d I .h ractJsc · ar c copiCs were measured off from full-stzc

moes.Ictcch·

·

1

-

8.

1

mque was cerum y practised from the second century

<:, am a Simple

·

hb

pc nod r,

k. r vcrston maY a vc een employed even in the ClassiCal

(s . b or)ma mg fimshed works from life- si7c or even reduced models

.cc a

ovcOL·II.

.

the 0

.

1· )VJOus y, t liS could VIrtually never be done dire. ctly from

ngma statue 111 sa t

k1

from 1

•.

ne uary or mar et p ace, and the copyist worked

Paster castshk th · 1

·

The casts

e ose 111 t 1e teachmg gallencs of our univcrsmes

were made fi

·

1

·

has Zcu•

rom ptece-mou ds taken from the originals. Luc1an

• comment on the h

dd·

the A the

A

P•tc smearc ai!y over a statue of Hermcs in

mangob

I

.

.

ra Y scu ptors prcpanng tt for casting.

A remarkable find m 1952 at Baiae on the Bay of Naples has preserved

scraps of casts from Greek original sculptures. These must have been

used in the copyist s' srudios. They include pieces of a number of famou s

srarues known ro us otherwise only from marble copres (here [4] and

pieces of our [1 87, 190-2, 202, 214 , ZJ41l and give us the opportunity to

draw direct, if sometimes trivial , compansons between copy and

original, su ch as we arc very rarely allowed otherwise (exce ption s -[122,

,

44 ]). They also include casts from o ri ginal Greek s tatues orhcrw1sc

wholly unknown to us although Roman marble copies (for which these

casts had been made) ma y one day be identified !11]. lr seems that the

casts were r einforced by iron or wood arm arures in the legs, with other

parrs of the body and dress stiffened by bone o r straw. They show that

on some figures the copyist had deliberately fleshed our the phys1que of

the original. They reveal too derails of work - how the eyelashes of a

bronze were protected when the mould was made, leaving them lumpy

on the cast (4]. and how hollow folds and undercutting were plugged

before moulding. The m odern caster r ecognizes the techniques re adily

enough.

Sources: literature

No treatise by an ancient sculptor abom his work has survived (e.g .,

Polyclitus' Canon: sec p. 205) and no treatise de.aling specifically wah the

hisrory of sculpture. Conte mporary litcrarure IS ex tremely renccnt, and

it is exceptional to find in Euripides' play l oll a character who 1~

bothering to co mm en t on the sculptural decoration of a temple 111 the set

(supposedly at Delphi). From later periods th.crc is some wealth of

relevant asides- in Cicero (mi d-1 st century BC) 111 a penod when Greek

culture was highly fashionable in R ome; in the works of literary scholars

like Quintilian ( 1sr century A o) who sought. analogres 111 the VIsual arts ·

in the wider ranging entertainments of cssay1srs hkc Lucran (znd cenruq

A o). The geographer Srrabo (died A o 21 or later) could have rold us

more, but seldom borhcrs with more than names. But there arc tW< •

major sources who between them account for most of the usefu l

testimonia we can deploy.

.

.

Pliny the Elder, who died observing the eruption of Vesuv1us 111 A r

79, wrote a Natural History which was in the nature of an encyclopacd1«

drawing on a wide variety of written sources (2,000 he sa1d), 111clud1~f:

the Helleni stic treatises on an criti cism. He lists hi s sources separately "

an index bm the remarks in his main text arc not individually attributed

The most influential source is generally thought to be Xenocrarcs 0 1

Sicyon, a third-cemury writer. Pliny has a long section on bronze statut

(Book 34· 5- -93) discussing material, types and the works ofthe pr111CIP·'

18

arnsrs whom he dates by their floruit ro Olympiads (periods of 4 years) ,

defining srudios and nanung pup1ls. His descriptions of individual statues

arc laconic but occasionally assist in the Identification of copies, and of

more interest arc the critical comments which he takes from his sources

and which tell us w hat Hellenistic scholars thought of the achievemcms

of Classical sculptors. This is not, of course, the same as the view which

would have been taken in the very different world and society for which

the sculprurcs had been created, and we arc vividly aware of the intrusion

of obfuscatory art-historical jargon. The short section on clay modelling

(Book 35· 151-8) and the comparati vely shorr one on marble sculpture

(Book 36.9 -44) arc presented in the same manner.

Pausamas IS our other major source, writing a guide to Greece in the

second ccnrury A D. He too used written sources, bm probably with less

discrimination than Pliny. H e expresses his own view from time ro time

but in his descriptions of sanctuaries and cit ies he is often very much a~

the mercy of what he was told by guides or priests, neither of them

necessarily reliable repos itories of accurate information. Sometimes h e

seems simply to ha ve been careless. Where we can check his statements

or descriptions by the sires or monuments he describes we often find

them faulty. Where we cannot ch eck them our only recourse is ro be

mildly suspiCIOUS at all times. In his descriptions of scenes his interpreta-

tion IS, naturally en ough, that of his own day, and we have ro imagine

what he saw, and attempt to rcmtcrprcr it in the light of the period in

which it was made.

In the follo\~ing chapters I mention, where appropriate, the literary

sources for attnbutwns or descnptlons, by t heir authors' names (Pau s.,

Phny, etc.) but genera lly Without further detail ofthe texts, which can be

found m rhe vanous published compendia.

With so little COIJte

·d

b

·

·

·

.

.

mporary ev1 cncc a out artists surv1vmg except

on ms cnbed bases from which rhc o ri ginal statue has alm ost' always

;,scaped, we arc forced to rely heavily upon sources like Pliny and

r ausamas 1f we wish •o

h'

1

·

1

•

pur names to t mgs or sty es, even rh111gs or

sry es wh1ch we can only observe in what we take to be accurate Roman

cop1cs. But names arc t

h.

·

dd·

rh

no everyt 111g; 111 cc , m the srudy of ancient art,

cy arc next to nothing.

19

Chapter Two

EARLY CLASSICAL SCULPTURE: INTRODUCTION

The physical turmoil of Greek history in the early decades of the fiftl·

century was answered in Greek art by what appea r s to be sure and stead\

progress, and the gradual changes in style encouraged effortlessly, 1

seems, a revolution in the sculptor 's approach t o his craft. This marks

turning point in W est crn art.

In less than a hundred and fifty years the G r eek scu lptor had perfectet.

his technical command of the medium in w hich most of the fi ncs1

Archaic sculpture was executed - white m arble. It is not an easy material

nor, on refl ection , can we judge it an obvious choice for the execution o

images in relief or in the round. We have r eflected on its properties in th <

la st chapter. lt lends itself to clear, sharply defined masses and pattern n <

less than eo subtlety of contour and even, as late r generations were t<

discover, to the expr ession of the soft, the vaguely defined, the sensual

The Archaic sculptor explored its potential in cr eating three-dimension•

patterns which represented the human body. Style evolved slowly, a·

t echnique improved, and the changes, which must have been admittC<

because t he r esults were more satisfying and the function s of the figUJ

we r e thus better served, also led to render ings which were closer eo lift

closer (fo r the whole body at least) than any achieved by other ancic1

cultures. Not that there is anything inherently good about realism in a rt

but o n ce the Greeks discovered how much more it could express than th

conventions, symbols and patterns ofArcha1sm, they made a virtue of 1t

Down to ar ound 500 what realism there was in Greek art, especially 11

the rendering of the naked male, was literally superfi cial. The figur <

con veyed no more than the sum of their parts, fairly accuratcl

delineated and fairly accurately juxtaposed. Soon, though , even th l

triumph of realism could, it was found , be impr oved upon. l t is apparel

from drawin g (on vases) more readily than in sculp ture that the artist w."

beginning to observe his s ubject con sciously, and not simply reprodu <-

ing what he had been taught of the conventions for representing a man,.

a god or an anima l. Closer observation was not confined t o detail, but

was the problem set by the proper rendering of detail on bodies not

attention but at case o r in motion, which led to a closer observation a b 1

of structure, and wah it a g r owing understanding of how a body move·

20

how its weight is carried, how a shaft in pose can affect the placmg of

limbs, corso: head. The sculpto rs of the last of the kouroi, like the

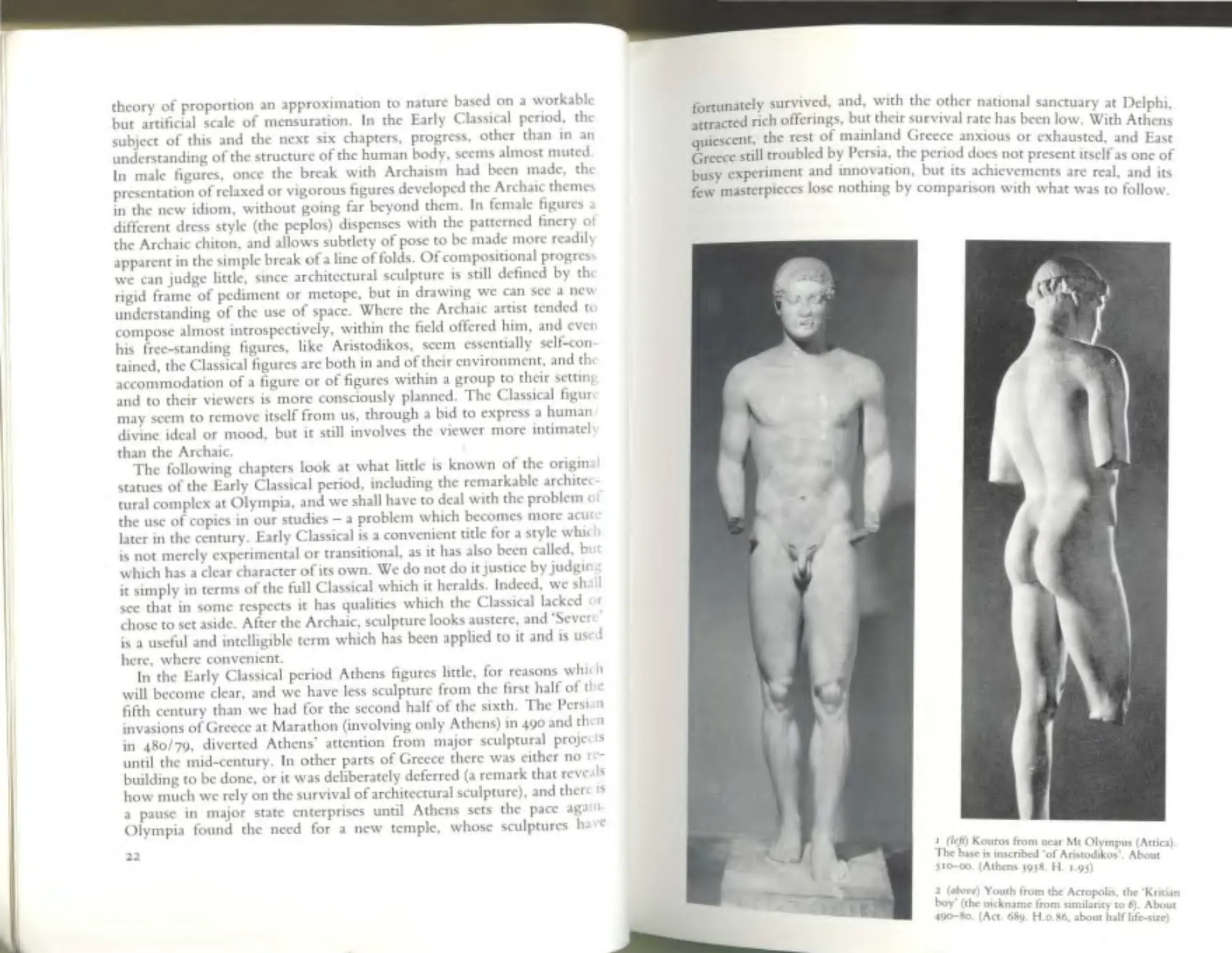

Athenian Anscod1kos of about 510-500 (1], did not need to worry too

much about this. The1r figu r es were evenl y poised, in balance. Figures in

violent acuon, runnm g or fighnng, could be compose d like articul ated

dolls, although there was g rowing awareness of the problems o f

r endenng_ a tWI~t mg figure, smcc so many were still basically conceived

in two d1mens1ons rather than three, including even those cut in the

round eo be set in temple pediments. The so-called 'Kritian boy' from the

Athenian Acropolis [2], probably earher than 480, betrays the new

awareness, we1ght sh1ft ed o n to one leg, the other slack, with hip

lowered and the shoulder and head lightly mclined. Now look ah ead

through this book, at [20.1 , 36, 38-_ 9, 65-9 , 72, 184-6 , 223, 227 -35] to

see how, through the century, th as calm assurance in showing t he

standmg figu r e IS Improved upon. But even the ea rliest of the figur es

abruptly remove us from the world of Archai c rigidity and pattern into

o n e m wluch art takes on the task of representing, even counter feiting

hfe, and not merely cr eatmg tokens of li fe.

Gr eek art in the Iron Age began with little or nothing by way of figure

decoration but wah abstract pattern, eventuall y applied to the construe-

non of man-symbols, whole scenes and even narrative. The formal

demands of pt~re pattern long remained close to the artist 's conscious-

ness, and as nmc pa sse~ were ex pressed in sophisticated theories of

m ensuration and proportion. All this might seem alien t o an a rt which

t~tthc casual observer, seemed in pur suit of the real, but t he demands of

P tern and proporuon we r e more consciously se r ved by the Archaic

arnst than any pos·t · d

·

kI.

d.

1 ave esare to ma e 11s works more lik e the world

aroun him. This remained true even aft er the possibili ties of realism

;e{e /ecogmzcd in the early fifth cen tury, and when a scu lptor

nootyac atus, came to write a book about his art later in the century it wa~

n anatomacal text b k b

.

'

'

beobse d. k

-

00 ut an essay about the 1deal proportions to

more

0

rve 1~ ma ang images of the human body, and based as much or

proport~omat ~manes than on the life class. These tendencies to observe

P

ositive stn ani . tho Jdca h ze rather than pa rticulari ze figures were more

unu•t anaseaeh£<

1··

·

came alnlo

'd

r

or rea IS tiC anatonucal presentation which

st acc1 entall y Th

d·

.

•

realismina t d £<

•

·

cy arc t e n cn c1es wh1ch held back obsessive

until afte r rtl an ' o r 111Sta n ce, life-like rather than idealized portraiture

1cpcnodstd'd · h'b

·

'

showed the

.

. u le 111 t IS ook . F1fth-ccntury sculpture

artast workang t

d

·f:

these appa r e tl

.

owar s a sans act o r y reconciliation of all

n Y contradictor y ai

h.h

.

.

expresses an

1·de 1

.

1

ms - an art w 1c m1rrors hfe that

a 111 1Uman 1m

hk

'

pattern and p

ages, t at ac nowledges the dominance of

r oport1on

The Archaac scul

·,

ptor s patterns were of surface anatomy and dress, his

21

theory of proportion an app r oximation to nature based on a workable

but ar tificial scale of mensuration. I n the Early Classical period, the

subject of this and the next six chapte r s, progr ess, other than in an

understanding of the structu r e of the human body, seems almost muted

In male figures, once the break with Archaism had been made , th(

presentation of relaxed or vigorous figures developed the Archaic theme~

in the new idiom, without going far beyond them. In female figures a

different dress style (the pep los) d ispenses with the patterned finery o f

the Archaic chiton, and allows subtlety of pose to be made more readil )

apparent in the simple break of a line of folds. Of compositional pro g res'

we can judge li t tle, since arch itectural sculpture is still defined by tlu

rigid frame of pediment or metopc, but in drawing we can sec a nC\\

u n derstanding of the use of space. Where the Ar ch aic artist t ended t<·

com p ose almost in t r ospectively, within the fteld offered him, and cvct 1

his free-st andi n g fig u res, lik e Aristodikos, seem esse nti all y self-con

rai ned, the C lassical figures arc both in and oftheir environment, and thr

accommodation of a figure or of figures w ithin a g r oup to their settin ~

and to t heir viewer s is more consciously pl ann ed. The Classica l figur t

may seem t o remove itself f rom us, through a bid to express a human

divine idea l or mood, but it st ill involves the viewe r more intimate!

than the Archaic.

The following chapte r s look at what little is known of the origin

statues of t he Early Classical per iod, including the remarkable arch ite r

tural complex at Olympia, and we shall have to deal with the problem <

the use of copies in our studies - a problem which becomes more acu .

later in the century. Early Classica l is a convenient title for a style whK

is not merely experimental or transitional, as it has also been called, b1

which has a clear character of its own. We do not do it justice by judgn

it simply in terms of t he full Classical which it heralds. Indeed, we sh I

sec that in some respects it has qualities which the Classical lacked <

chose to set as ide. After the Arch aic, sculptu re looks auste r e, and 'Sever· '

is a useful and intelligible ter m which has been appl ied to it and is us• J

here, w h ere convenient.

In the Ea rl y Classical per iod At hen s figures li ttle, for reaso n s whtt 11

w ill become clear, and we have less scu lpture f rom the first half oft 1C

fifth century than we had for the second half of the sixth. The Pcrst. n

invasio n s of Greece at Marathon (in volving only Athen s) in 490 and th • n

in 480/79, dive rted Athens' atten tio n fr om major sculptura l projct s

until the mid-centur y. In other parts of G reece there was either no

building to be done, o r it was deliberately defe r red (a remark that rcv c Is

how much we rely on the survival ofarchitectura l scu lpt ure), and the n ts

a pause in major state enterprises until Athens sets the pace ag a •L

Olympia found the n eed for a new temple, whose sculptures h.

·c

22

fortunately sur vived, and, wah the other national sanctuary at Delphi,

attracted nch offenngs, but thetr survtval rate has been low. With Athens

qu iesce n t, the rest of mamland Greece anxious or exhausted, and East

Greece s till troubled by Pers1a, the pe r iod does not present itself as one of

busy experiment and innovation, but tts achtcvements are real, and its

few mastcrpteccs lose nothmg by comparison with what was to follow.

I (ltji) Ko uros from near~~ Olympus (Amc.a).

The base 1.s mscnbed 'ofAruto<hkos· . About

s• o-oo. (Athens 39J8. H. L9S)

1 (a.bov~) Youth from the A cropolis, the 'Krna.an

boy (the mcknamc from s1m1laru y to 6). About

49G-8o. (Act. 689 . H.o.86 , >bout h>lfhfe-S<Zel

Chapter Three

EARLY CLASSICAL MEN AND WOMEN: I

In the Archaic period the two most important sculptu r al types, in which

artists displayed their g r owing comm and in rcp r esentmg plaust.ble

anato m y and dress, edging all the time by a sort of natural selection

towards a m ore realis t ic image (see GSAP 65), were the st andmg nude

man and the dressed woman - the kouros and korc. The same two baste

types remain important in Greek sculpture throu gh the Classtcal penod

and we shall conside r each of them before gomg on t o look at larger

co mplexes, as at Olympia, in which they arc al so to be fo und, and at the

figures in o ther poses.

.

.

.

.

.

We begin perversely, however, by tgnonng.our pnnctple o f relcgaung

copies t o a separat e chapter and by dcscnbmg a g.roup frorr1. a city,

Athens, that we h ave just declared rel a u vely b.arren. 1~ thts. pcnod. The

reason is that t he group is known by scraps of ItS ongmal (m casts), and

that it demonstrates very well many of the problems of the. use of texts

and copies in our stud y. The group is that of the Tyranmctdes.

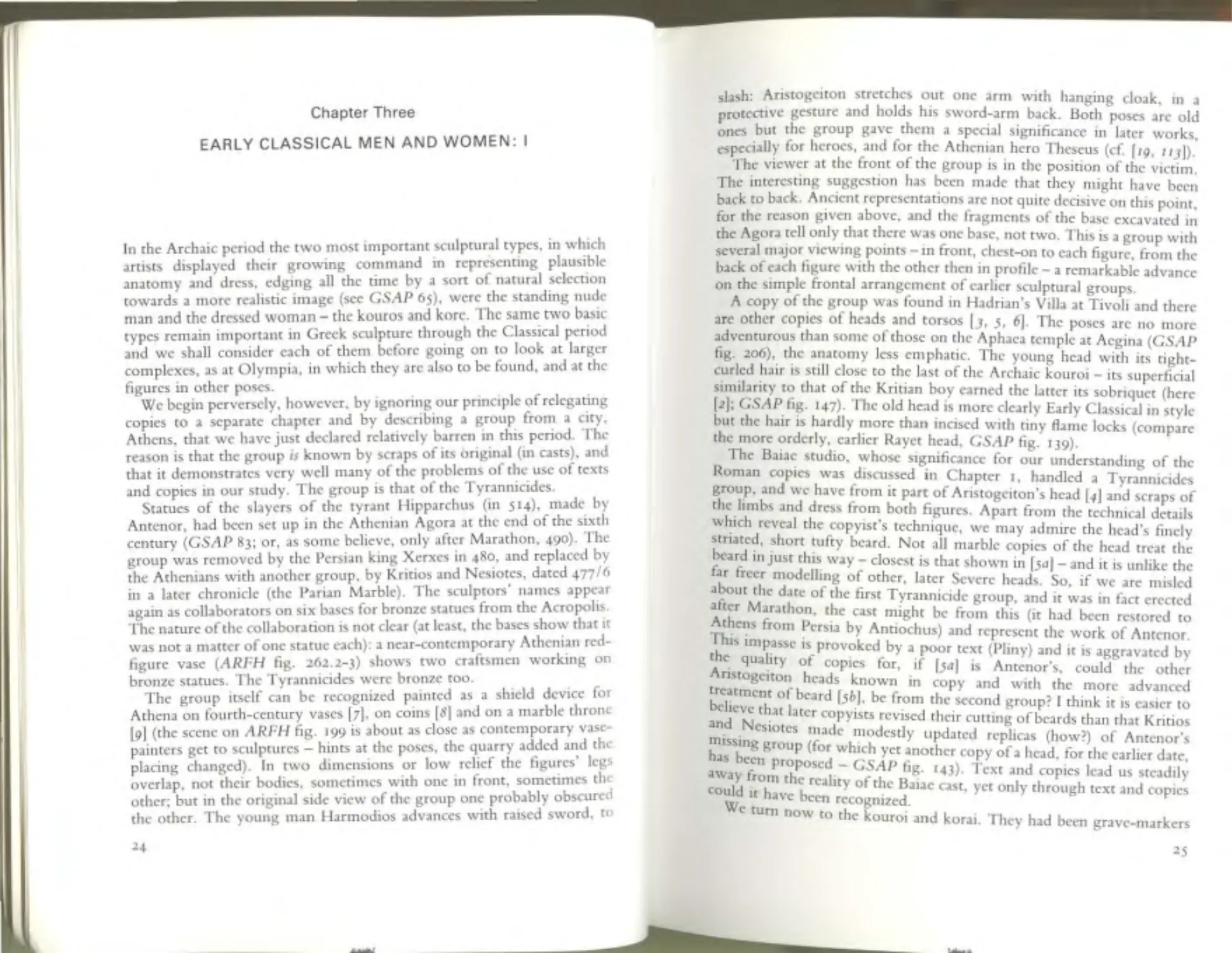

Statues of the slaye r s of the t yrant I lipparchus (in 514), made by

An t enor, had been set up in the Athenian Agora at the end of t he st~th

century (GSAP 83; or, as some believe, onl y after Ma rathon, 490). 1 he

group was removed by the Persian king x.erxcs in 480, and replaced by

the Athenians w ith anothe r grou p, by Krmos and Nes10tes, d ated 477 / 6

in a later chronicle {the Parian Marble). The sculptors' names appear

again as coll aborato rs on six bases for bronze statues from the Acropolis

The n ature ofthe co ll aboration is n ot clear (a t least, the bases sh ow that tt

was not a m atter of one st atue each): a near-contemporary Atheman red-

figure vase (ARFH fig. 262.2 -3) shows two cr aftsmen workmg on

bronze statu es. The Tyrannicides wer e br onze too.

.

.

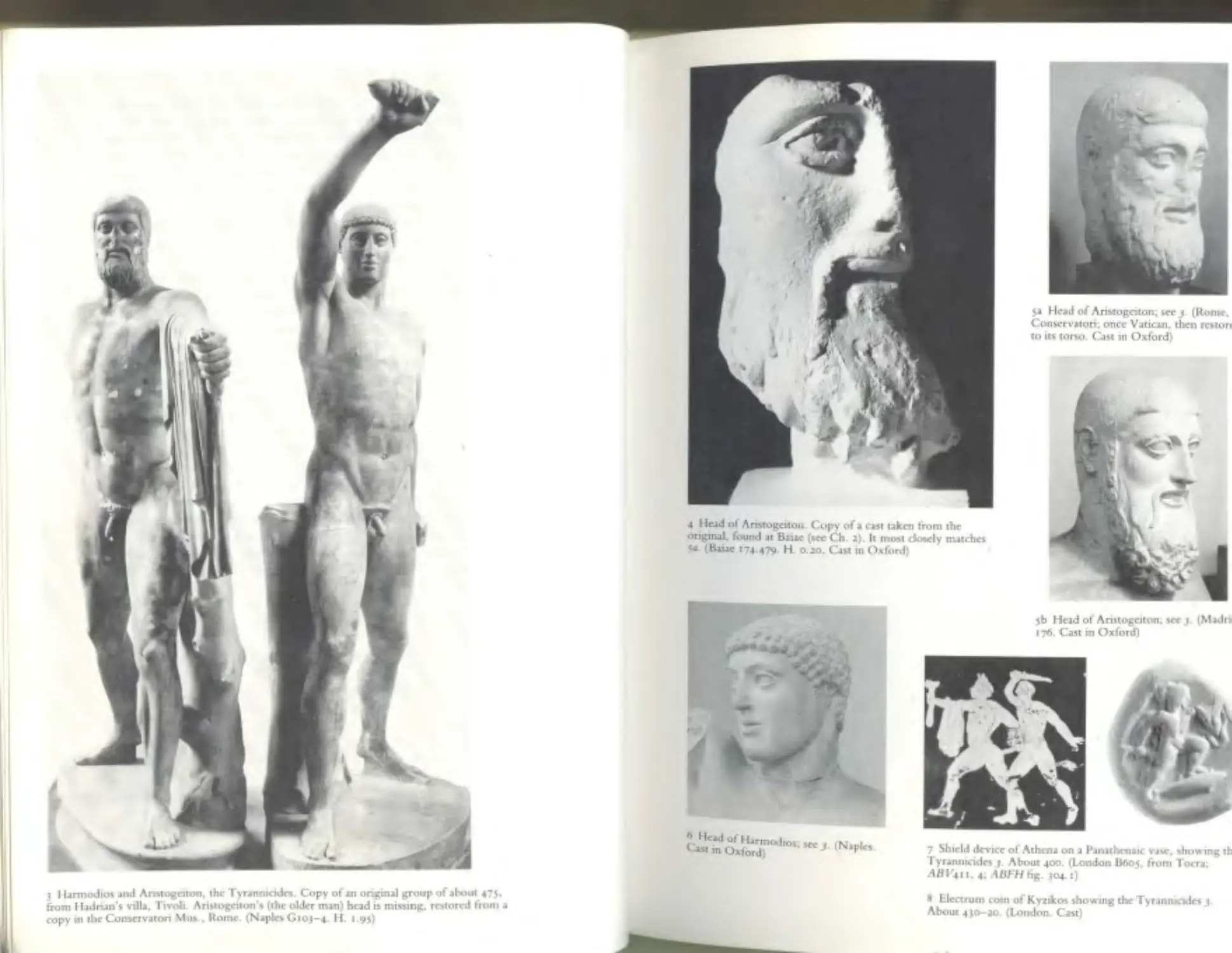

T he grou p itsel f ca n be r ecognized painted as a shteld devtce for

Athena on fourth-centu r y vases [7], on co in s [8] and on a marbl e throne

[9) (the scen e on ARFH fig. 199 is about as close as contemporary vase~

painters get to sculptures- hmts at the poses, the quarry added a~d t h.

placing ch anged). I n two d imens ions or low rchef the figures le gs

overlap, not their bodies, sometimes with one in fr ont, somettmes the

other; but in the original side view of the group on~ probably obscured

the other. The young man Harmodios advances with ratsed sword, t<

slash: Anstogeiton str etches out one arm with ban ging cloak, in a

protective gesture and holds his sword-arm back. Both poses arc old

ones but the group gave them a specia l significance in later wo r ks,

especially fo r h eroes, and for the Athenian h ero T hescus (cf . [19, liJj}.

The viewer at the fr ont ofthe group is in the position of the victim.

The interesting suggestion has been made that they might have bee n

back to back. An cient representations ar c not quite decisive o n this point,

for th e r eason given above, and the fragments of the base excavated m

the Agora tell only that there was one base, not two. This is a group with

several major v iewing points- in front, chest-on to each figure, from the

back of each figure with the other then in profi le- a remarkable advance

on the simple frontal arrangement of earlier scu lptural g r oups.

A copy of the group was found in H ad rian's Villa at Tivoli and there

are other copies of heads and torsos [J, 5, 6]. The poses arc no more

ad venturous than some o f th ose on the Aphaca temple at Aegin a (GSAP

fig. 206),. the a ~1atomy less emphatic. The young bead with its tight-

curled batr ts stt ll close t o the l as t of the Archaic k ouroi- its superficial

simil arity to that of the Kritian boy ea rned the latter its sobriquet (here

[z); GSAP fig. 147). The old head is more clearly Ea rl y C lass ical in st yle

but the h atr ts hardly more than incised w ith tiny Aame locks (compare

the more orderl y, earli er Ra yet head, GSAP fig. 139).

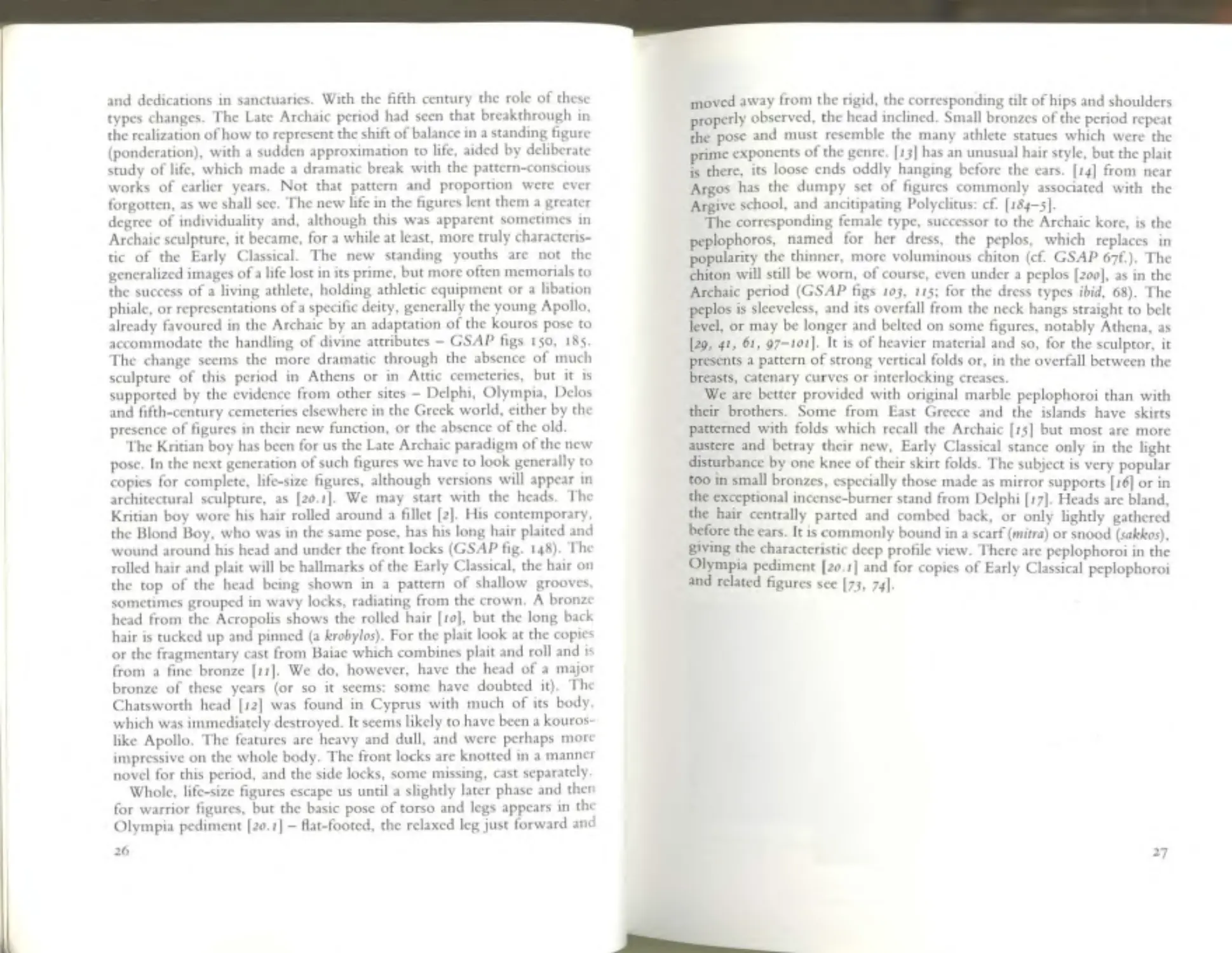

The B atae studio, ~hose significa n ce for our understanding of the

Rom an coptes was dtscussed m Chapter 1, h andled a Tyrannicidcs

group, and we have from it part of Aristogciton's head [4] and scr aps of

thehmbs and dress from both figures. Apart from the technica l details

whtch r eveal the co pyist's technique, we ma y ad mire the h ead's finely

strtated , sh ort tufty beard. Not all m arble copies of the h ead t reat the

beard m JU St tht s way- closest is that shown in [5a ]-and it is unlike the

far free r modelling of other, later Severe heads. So, if we are misled

about the date of the first Tyrannicidc g r oup, and it was in fac t erected

after Marathon, the cast might be from this (it had been restored to

Athe~s from Per sia by Antiochus) and represent the work of Antenor.

~~IS tmpasse ts provoked by a poor text (Piiny) and it is aggravated by

A . qualtty of coptes for, tf [5a) is Antcnor's, could the other

n stogctton h eads known in co py and with the more advanced

treatment ofbca d [ b) b fi

1

d

·

.

.

.

br

.

r 5 , e romt1csccon group?Ithmktttscasterto

a~~c~ t hat later copyist s r evised their c u tting o f beards than that Kriti os

.

.

cstotcs made modestly updated rep li cas (how') of Antcnor's

hmts sbtng group (for w hich yet another copy of a head for the ea rli er date

as ecn prop d GSA

'.

'

away fi

hosc -

P fig. 143). Text and coptes lead us steadily

could ro; t cb r ca lity of the Baiae cast, yet only through text and copies

It avc cen r ecogmzed.

Weturnnowtotbk . dk

.

c ourot an orat. 1 hey had been grave-markers

25

and dedications in sanctuaries. With the ftfth century the role of these

types changes. The Late Archaic period had seen that breakthrough m

the realization of how to represent the shift ofbalance in a standmg figure

(ponderation), w ith a sudden approximation to life, aided by dcltberatc

study of life, which made a dramatic break with the pattern-conscious

works of earlier years. Not that pattern and proportion were ever

forgotten, as we shall sec. The new life in the figures lent them a greater

degree of individuality and, although this was apparent somcnmcs m

Archaic sculpture, it became, for a while at least, more truly charactcns-

tic of the Early C la ssical. The new standing youths arc not the

generalized images of a life lost in its prime, but more often memorials to

the success of a living athlete, holding athletic equipment o r a libation

phialc, o r r epresentations of a specific deity, gen erally the young Apollo,

already favoured in the Archaic by an adaptation of the kouros pose to

accommodate the handling of divine attributes- CSAP figs 150, 185.

The change seems the more dramatic through the absence of much

sculptur e of this period in Athens or in Attic cemeteries, but it is

supported by the evidence fr om other sites- Delphi, Olympia, Dclos

and fifth-century cemet e ri es elsewhere in the Greek world, either by the

presence of figures in their new function, or the absence of the old.

The Kritian boy has been for us the Late Archaic paradigm of the new

pose. In the next generation ofsuch figures we have to look generally to

copies for complete, life-size figures, although versions will appear in

architectural sculpture, as [zo.t]. We may start with the heads. The

Kritian boy wore his hair rolled around a fillet [2]. I Lis contemporary,

the Blond Boy, who was in the same pose, has his long hair plaited and

wound around his head and under the front locks (GSAP fig. 148). The

rolled hatr and plait will be hallmarks of the Early Classical, the hatr on

the top of the head being shown in a pattern of shallow grooves .

sometimes grouped in wavy locks, radiating from the crown. A bronze

head from the Acropolis shows the rolled hair [10], but the long back

hair is tucked up and pinned (a krobylos). For the plait look at the copies

or the fragmentary cas t from Baiac which combines plait and roll and t<,

from a fine bronze [11 ]. We do, however, have the head of a major

bronze of these years (or so it seems: some ha ve doubted it). The

Chatsworth head [12] was found in Cyprus with much of its body,

which was immediately destroyed. lt seems likely to have been a kouros-

likc Apollo. The features arc heavy and dull, and were perhaps more

impressive on the whole body. The front locks are knotted in a manner

novel for this period, and the side locks, some missing, cast separat ely.

Whole, life-size figures escape us until a slightly later phase and then

for warrior figures, but the basic pose of torso and legs appears in the

O lympia pediment [zo.t[- flat-footed, the r elaxed leg just forward an d

26

moved away from the rigid, the corresponding tilt of hips and should ers

properly observed, the head inclined. Small bronzes ofthe period repeat

the pose and must resemble the many athlete statues which were the

prime exponents ofthe genre. (13[ h~s an unusual hair style, but the plaa

is there, tts loose ends oddly hangmg before the ears. (14] from near

Argos has the dumpy set of figures commonly associated with the

Argivc school, and ancitipating Polyclitus: cf. [184-5].

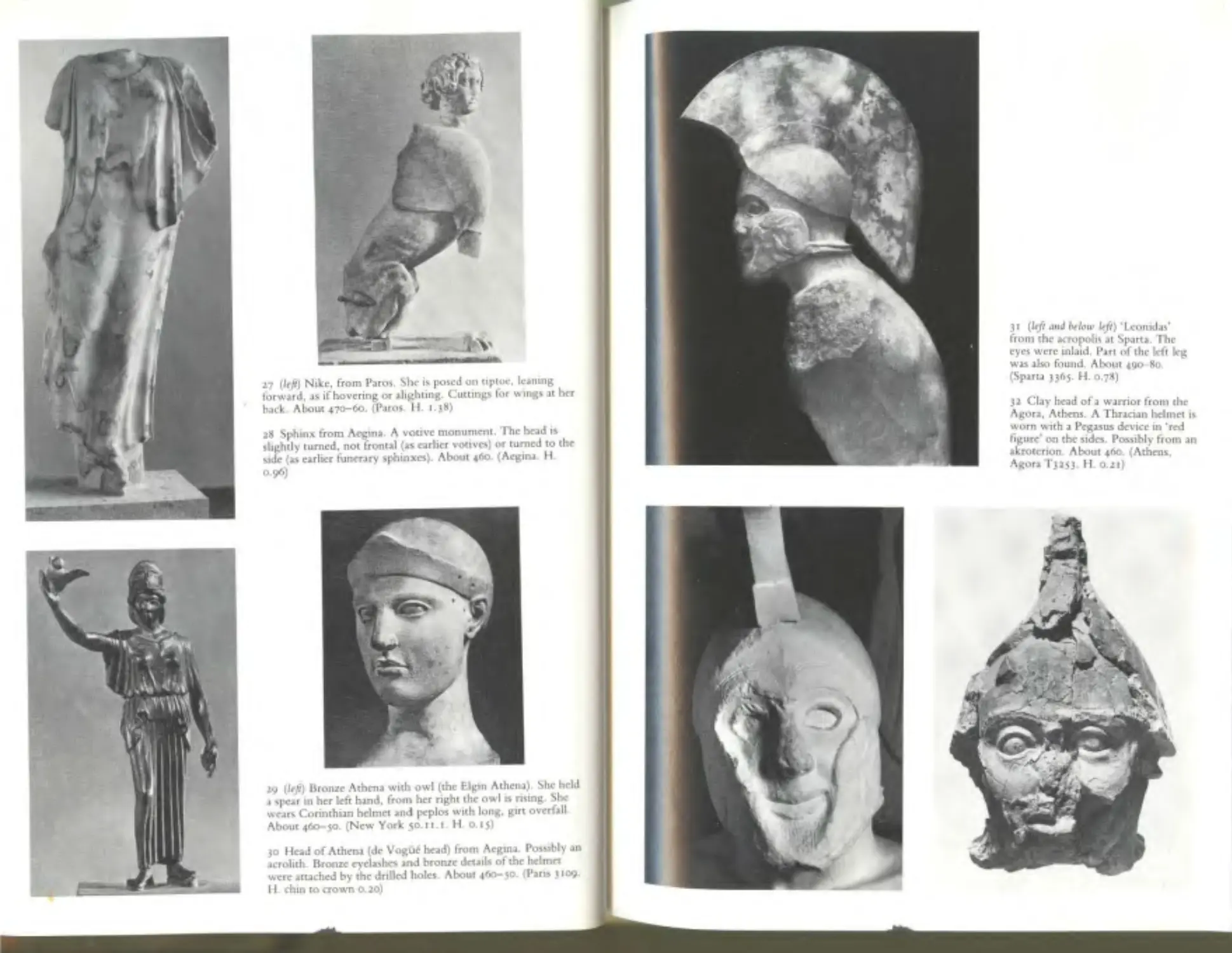

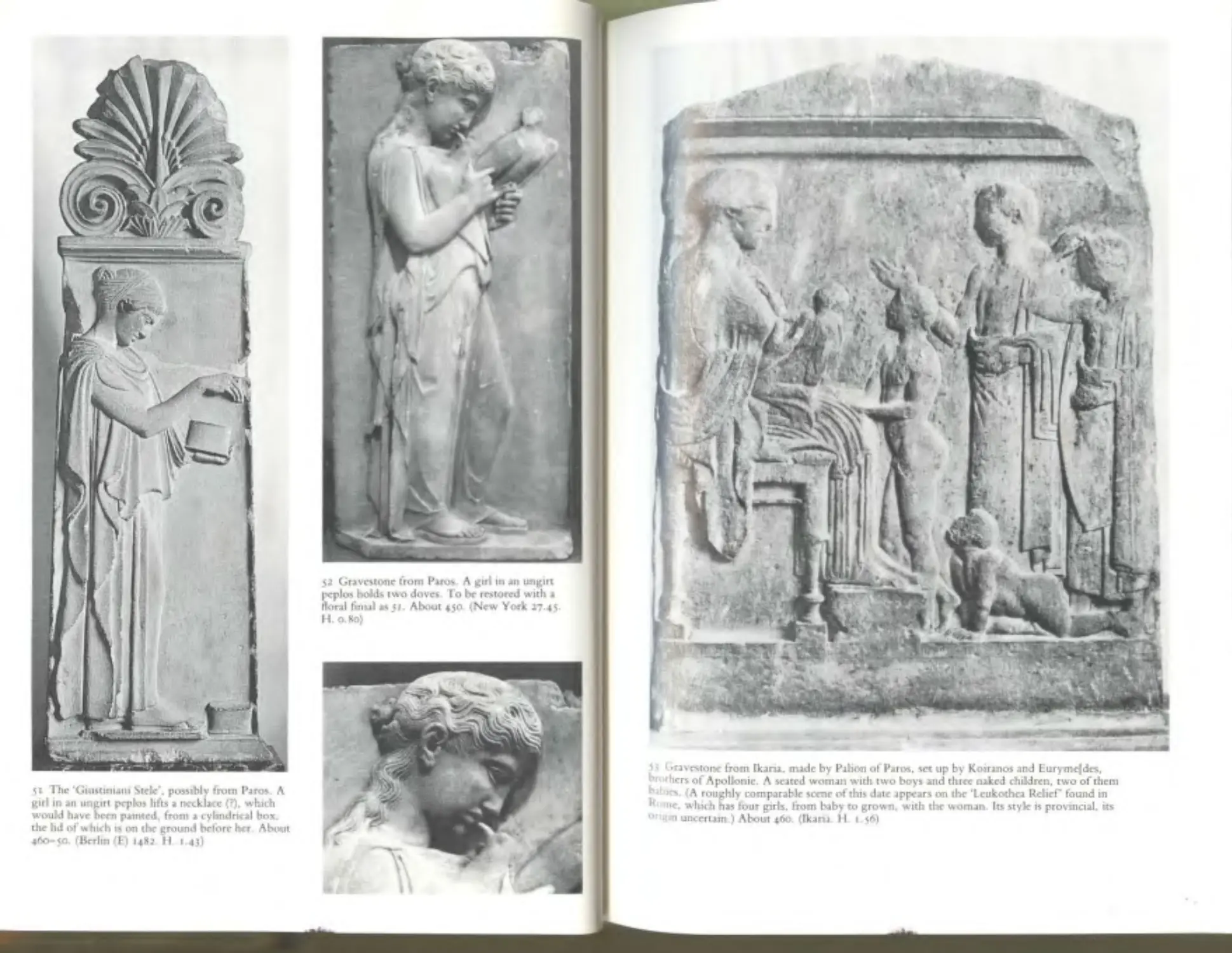

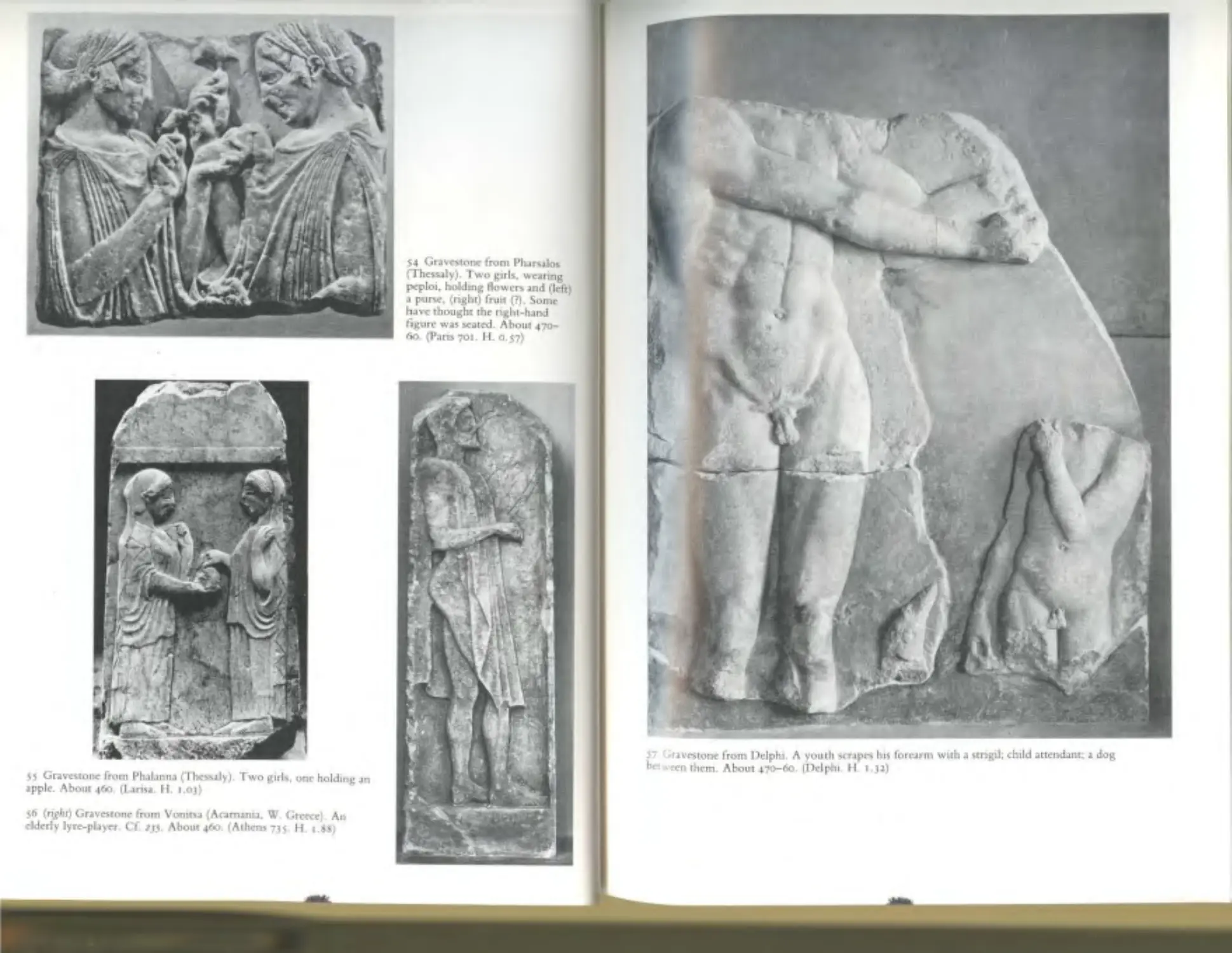

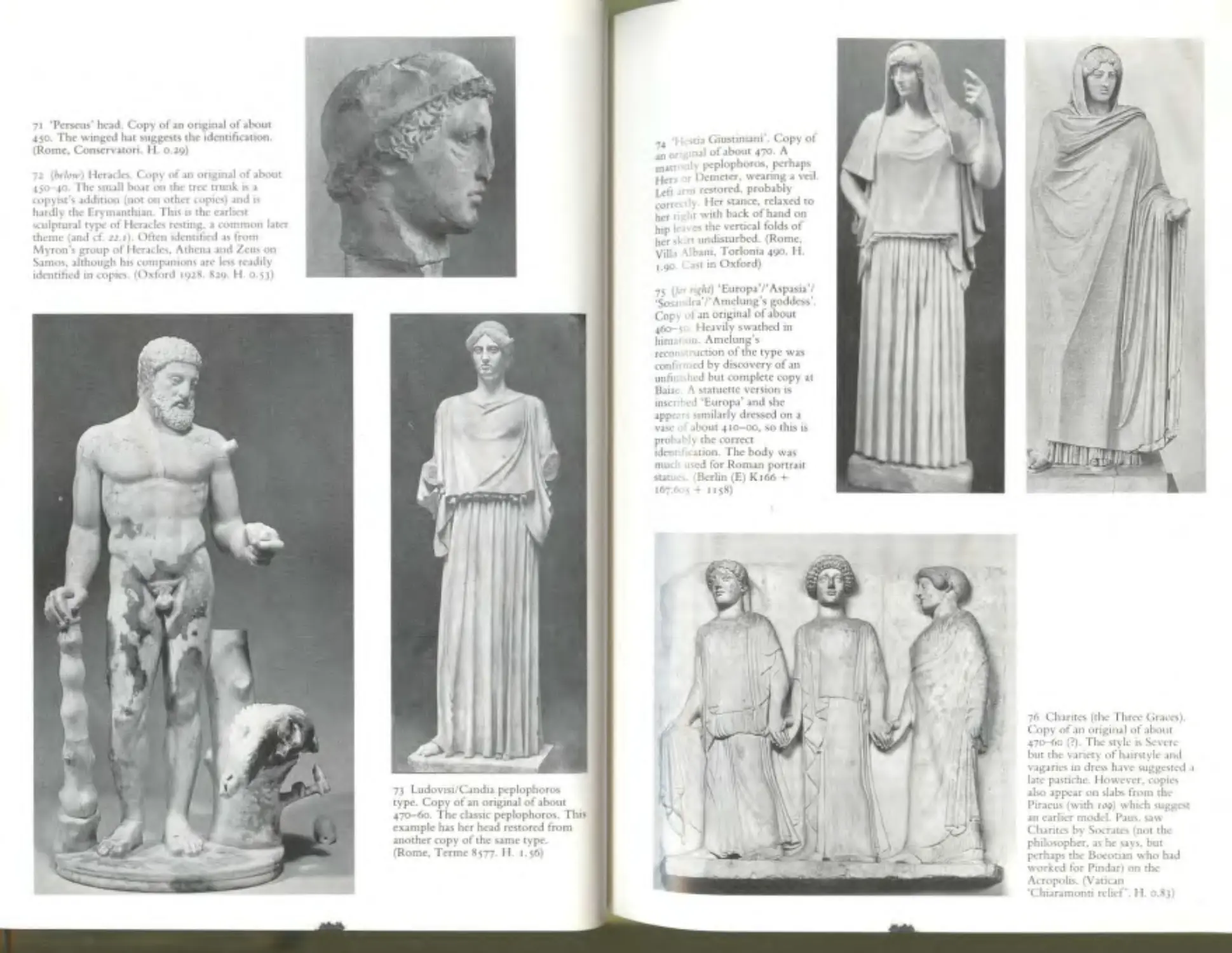

The corresponding female type, successor to the Archaic korc, is the

peplophoros, named for her dress , the peplos, which replaces in

popularity the thinner, more voluminous chiton (cf. GSAP 67f. ) . The

chiton will still be worn, of course, even under a peplos [zoo]. as in the

Archaic period (CSAP figs IOJ, 115; for the dress types ibid, 68). The

pcplos is sleeveless, and its overfall from the neck hangs straight to belt

level, or may be longer and belted on some figures, notably Athena, as

(29, 41, 61, 97-101]. lt is of heavier material and so, for the sculptor, it

presents a pattern of strong vertical folds or, in the overfall between the

breasts, catenary curves or interlocking creases.

We arc better provided with origina l marble pcplophoroi than with

their brothers. Some from East Greece and the islands have skirts

patterned with folds which recall the Archaic (15] but most arc more

austere and betray their new, Early Classical stance only in the light

disturbance by one knee of their skirt folds. The subject is ve r y popular

too in small bronzes, especially those made as mirror supports (16] or in

the exceptional incense-burner stand from Delphi [ 17]. Heads arc bland,

the hair centrally parted and combed back, or only lightly gathered

before the ears. lt is commonly bound in a scarf (mirra) or snood (sakkos),

gtvmg the characteristic deep profile view. There are peplophoroi in the

Olympta pcdtment [zo.t] and for copies of Early Classical peplophoroi

and r elat ed figures see (7J, 74 ].

27

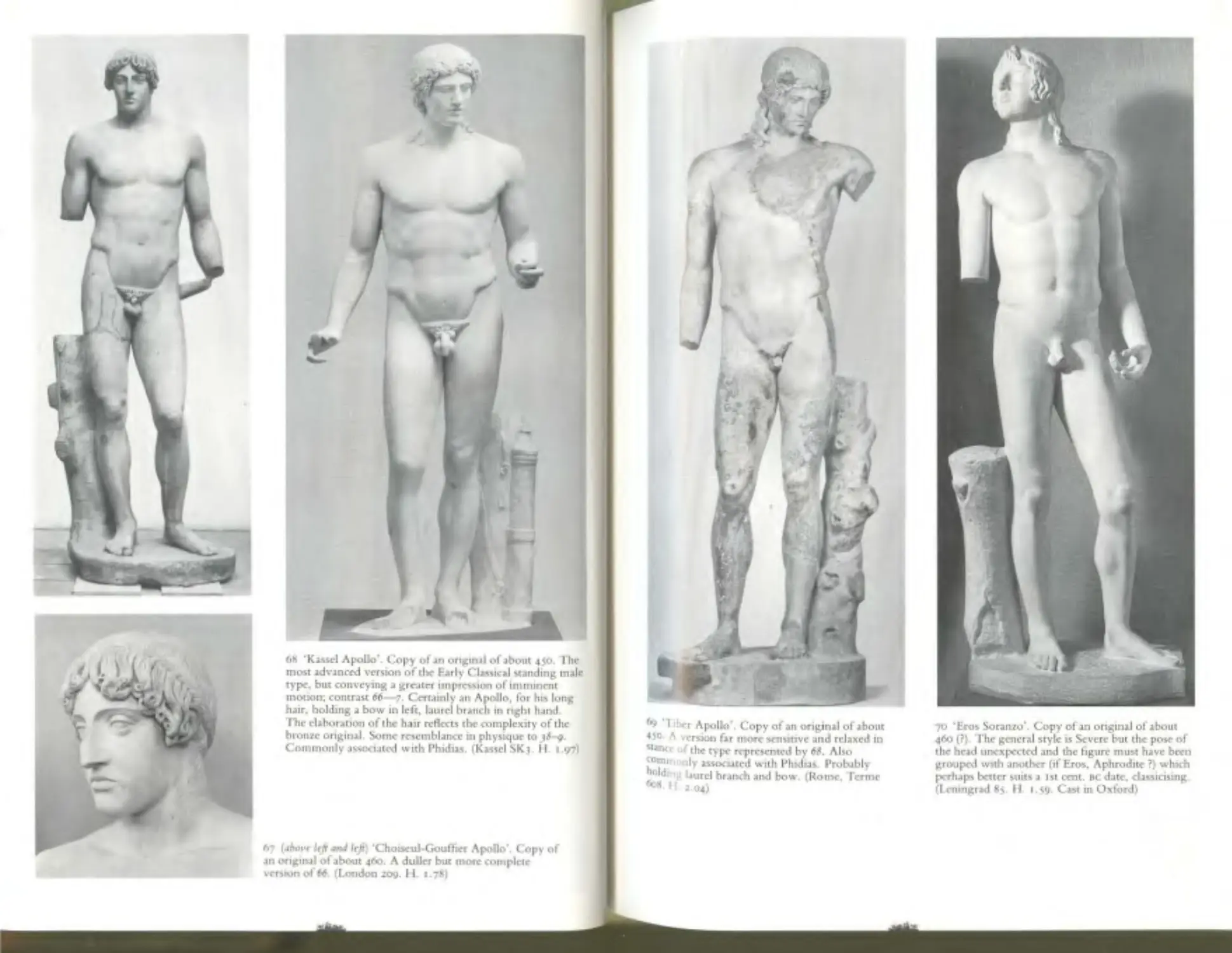

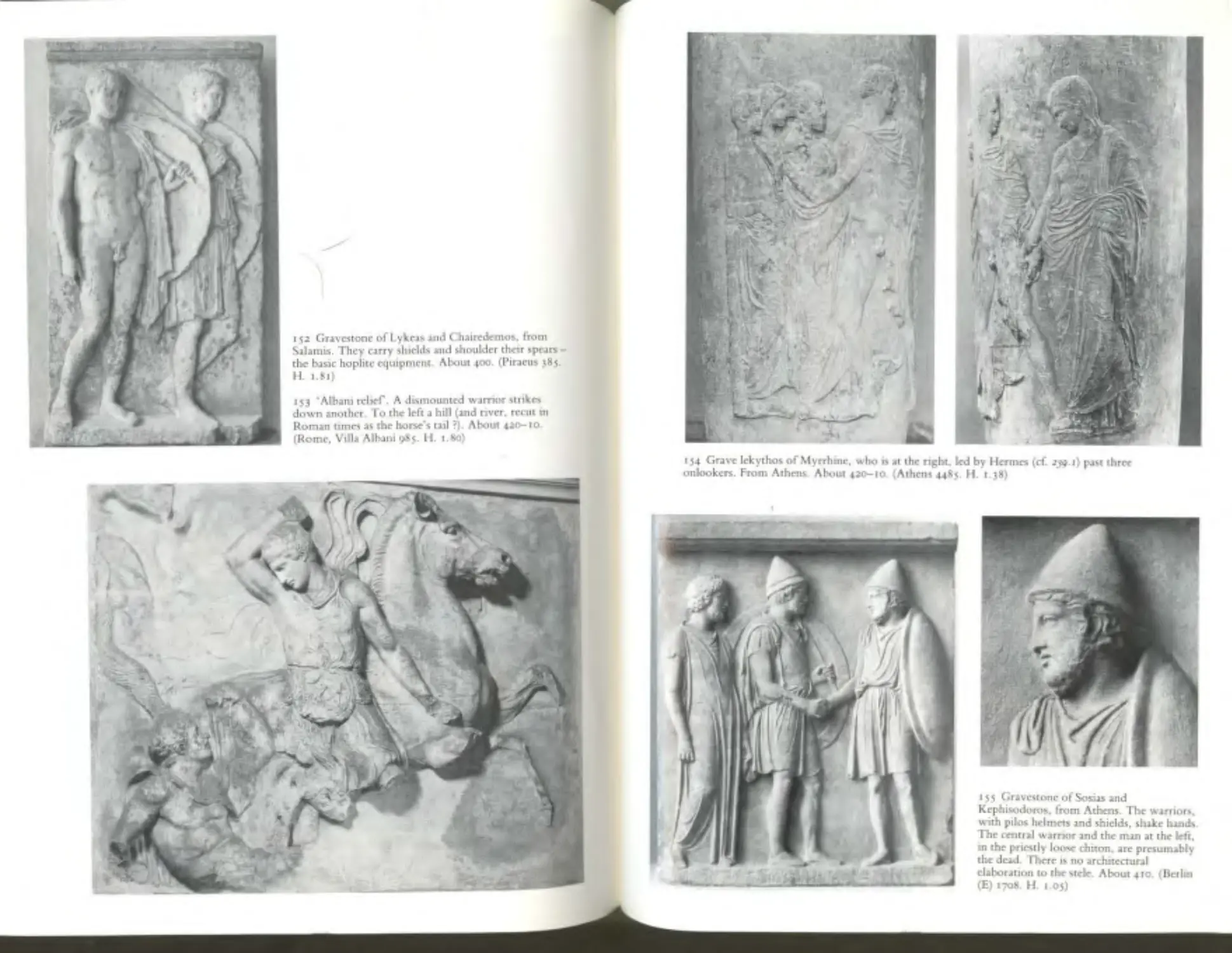

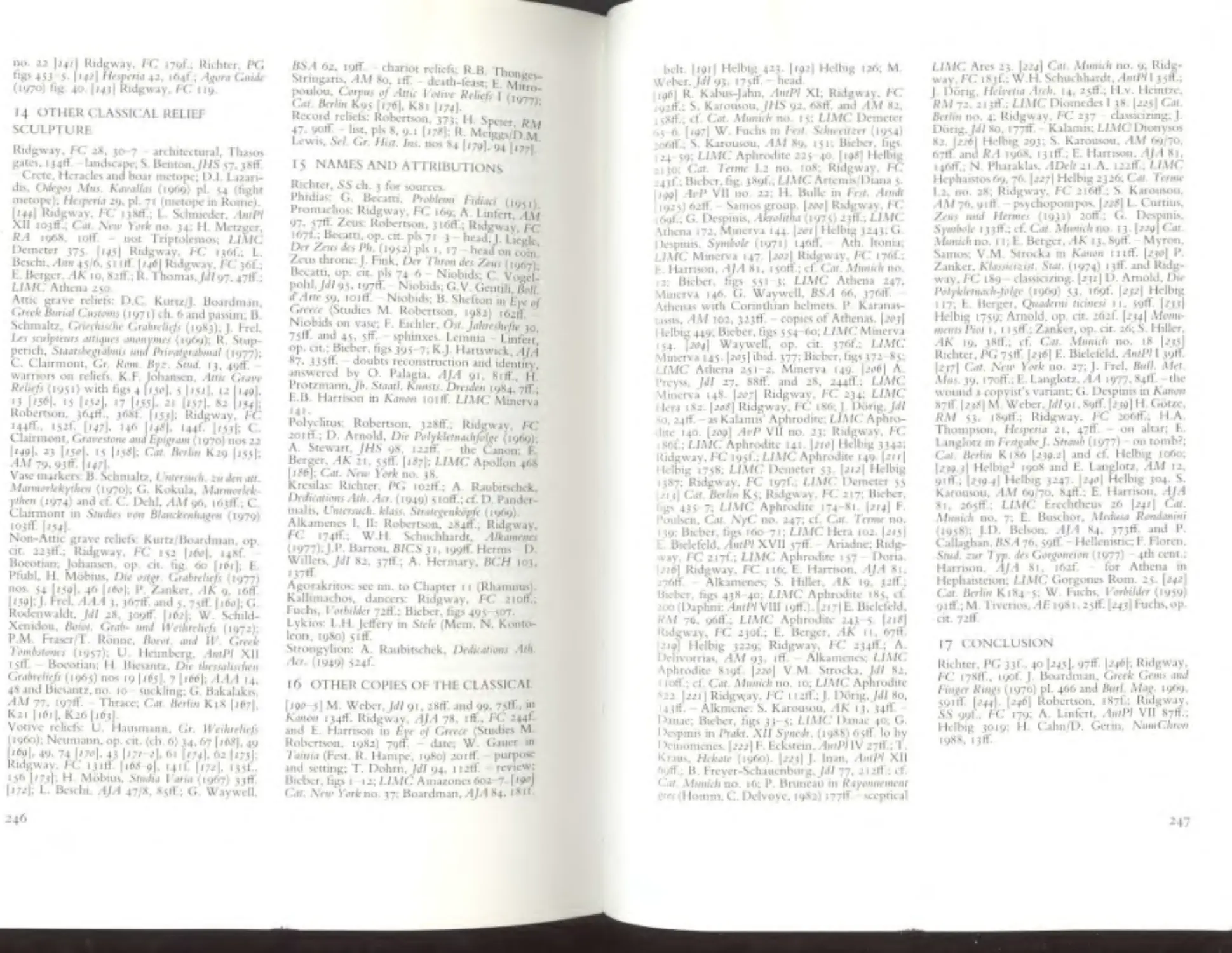

3 Humod1os 01nd Anstogeuon. the TyrOinmcJdes. Copy of an origmal group of1bout -475.

from 1bdrlan's v11la, hvoh. AriSlogeuon's (the older man) head IS nussmg. restored from 1

copy m the Constrvatorl M us ., Rome. (Naples G 103-4· 11 . 1.95)

sa He01d of Aristogciton; sec J. (Rome,

Conservaton; once V01ttcan, then restore

to its torso. Cast in Oxford)

4 _H~ad ofAnSlogenon. Copy ofa c01st uken from the

ongtn.t .l, found 0111 Bata~ (sec Ch. 2). h most closely ma1ches

512. (Ba101e 174 -4 79- H 0 .20. C.tst in Oxford)

•

~ Hc..d of Humochos; sec J (NOiiples

ast m Oxford)

sb He.td of Aristogeuon; see J . (Madru

176. C01st in Oxford)

7 Sh1cld dtvtC<' of Athen.t on 011 P01natheru.1c va<e, \hO"'"'mg th,

l"yunnicides J. Abou1 400. (London ll6o,S. from Tocu;

ABV411, 4; ABFHfig. 304.1)

8 Electrum com of Kyz•kos showmg 1he Tyranmcides J .

About 43o-2o. (London. C•st)

9 Ocloul from a marble throne (the Elgm throne)

showing lhe 1 yranmcides J About JOO. (Mahbu

74 . AA.u)

11 Fragmentary pbster cast from a bronze o rigmal of

about 470-50. Ear, eulocks and ha1r rolled over a

pbn. (Bme 174 482. L . O .lj)

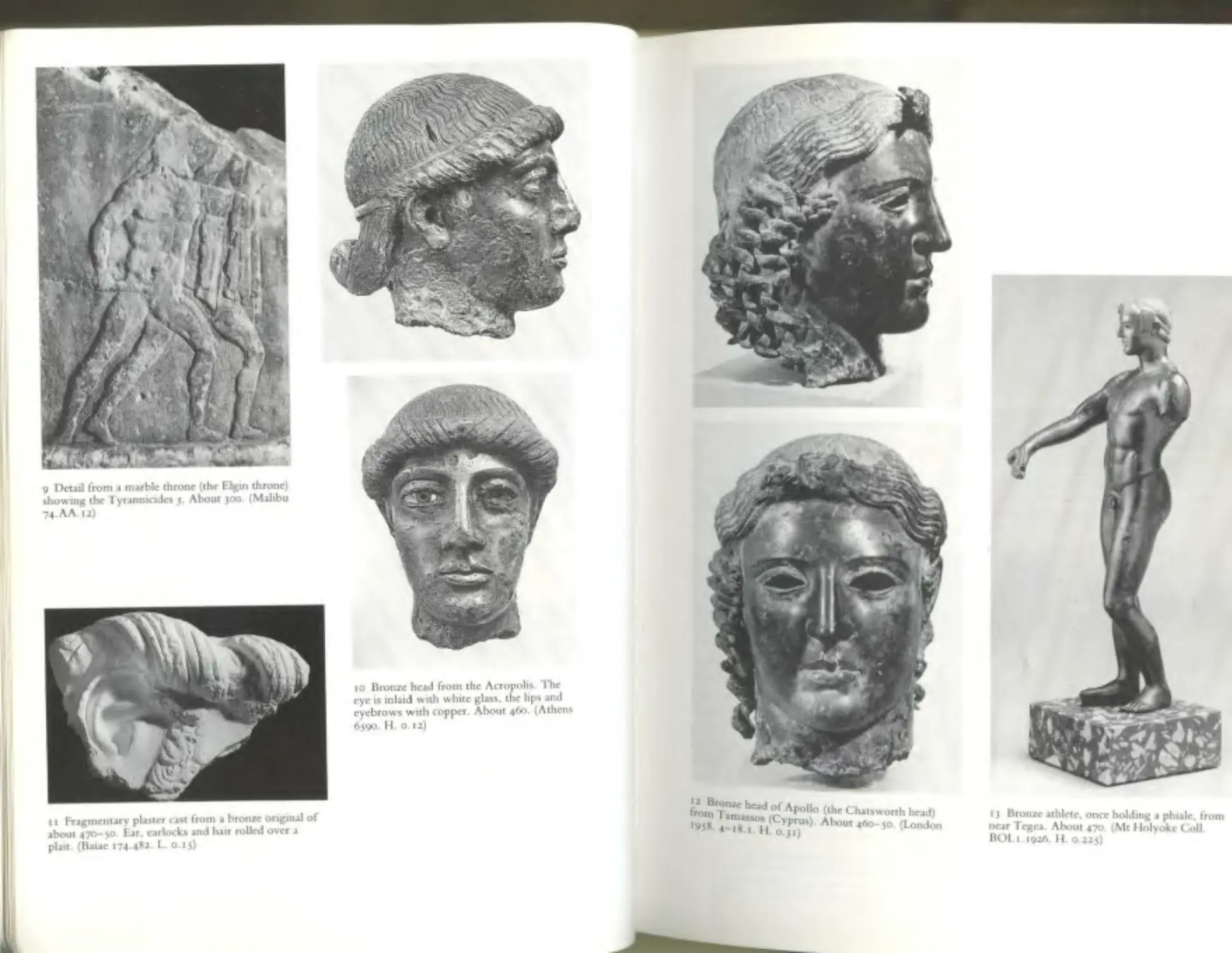

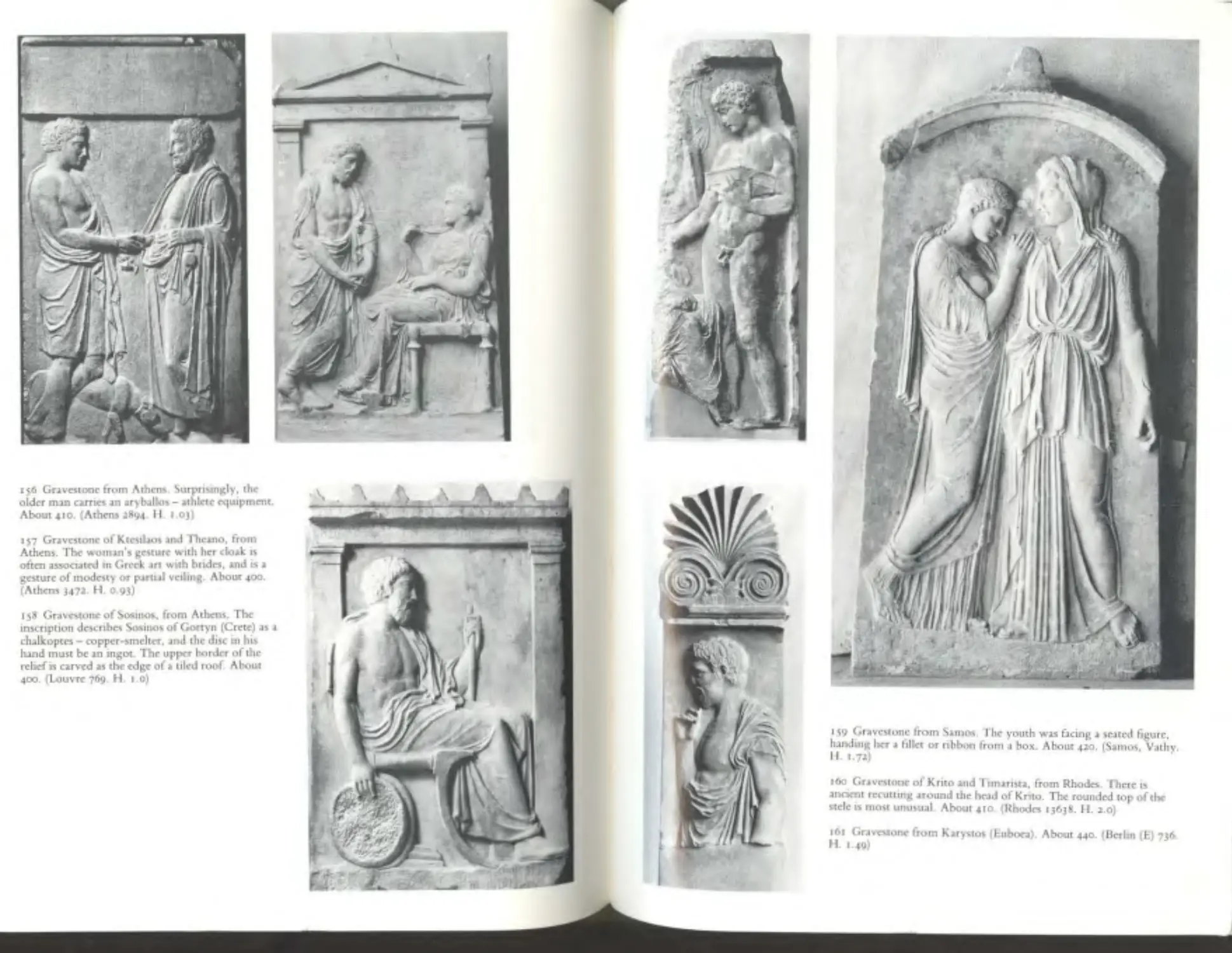

1o Bronze head from the Acropohs. l "he

eye is mlaid wuh white gbss, the lips and

eyebrows w1th copper. About 46o. (Ath en~

6590·H.0.12)

12 Bronze he<J.d fA 11

from T amassos (~ po o {the Ch:uswonh head)

1958 . 4-18.1 11 /j;)us) About 46<>-jo. (London

I J Bronze athlele, once holdmg 1 ph1ale, from

ne>r Tege• . About 470. (Mt Holyokc Coli

BO I. t .1926. H. 0 .225)

'

14 Bronu athlete holdmg a ball. from L1gouno. The

footplate w2s fitted m1o a base by four studs. About 46o.

(Berhn m1Sc.8o89 H 0.147)

15 (nght) Woman from Xanthos (Lycla). A scnes ofthese

figures may h:.tvc deconted chc terrace ofa heroon on the

>cropohs. About 46o. (London B318 H J.2S)

16 Bronze m 1rro r support. She

stands on a foldmg stool and

supports the crescent-shaped

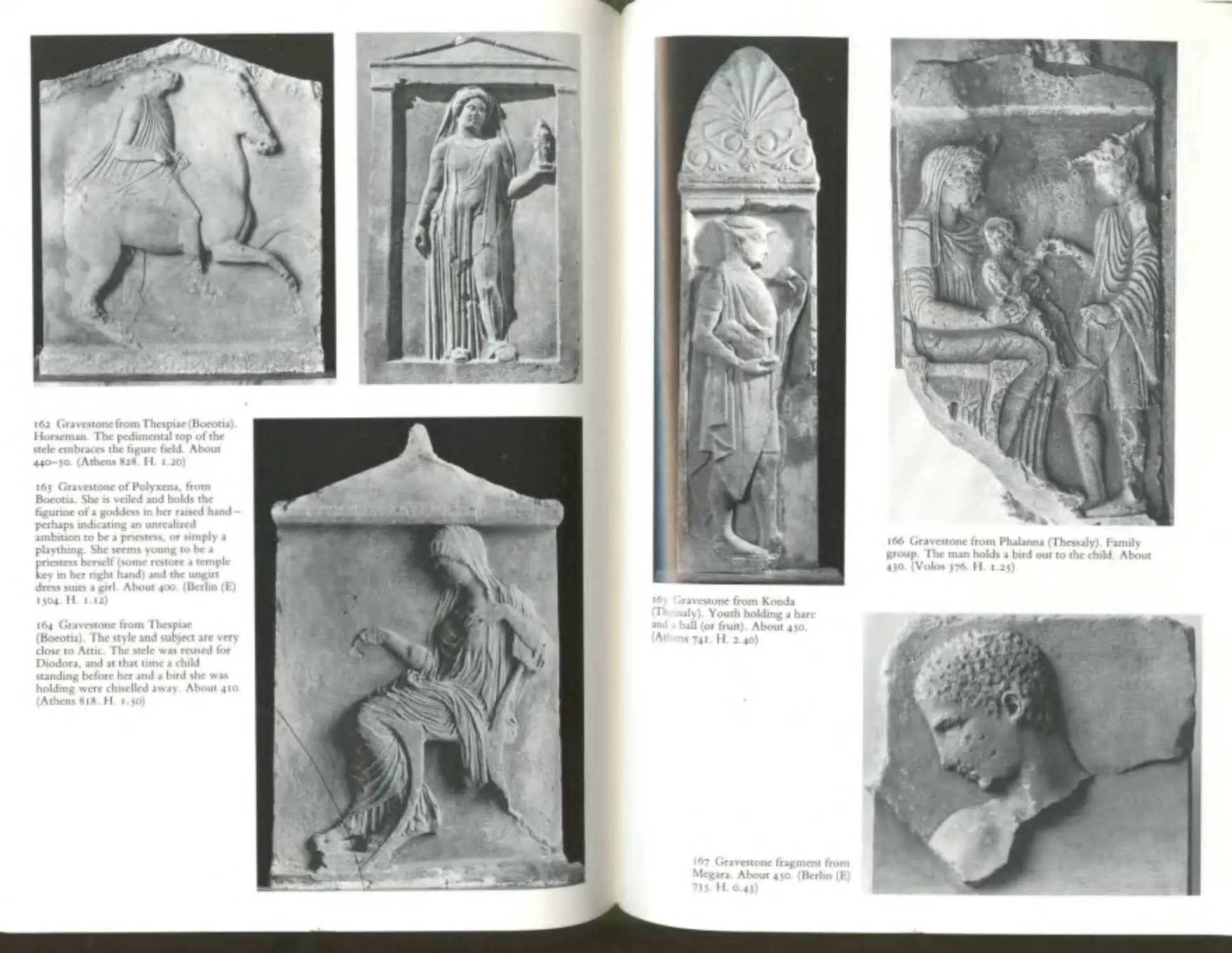

holder of the nurror dt)(. fhe

scheme IS a common one at 1h1~

pcnod About 470. (Boston

017499 11 of figure 0.18)

17 Bronze support of an

mcense-burncr, from Delph1 .

She wears an ungtrt pcplo'

About 470. (Delph1 11 offigur ·

0.16)

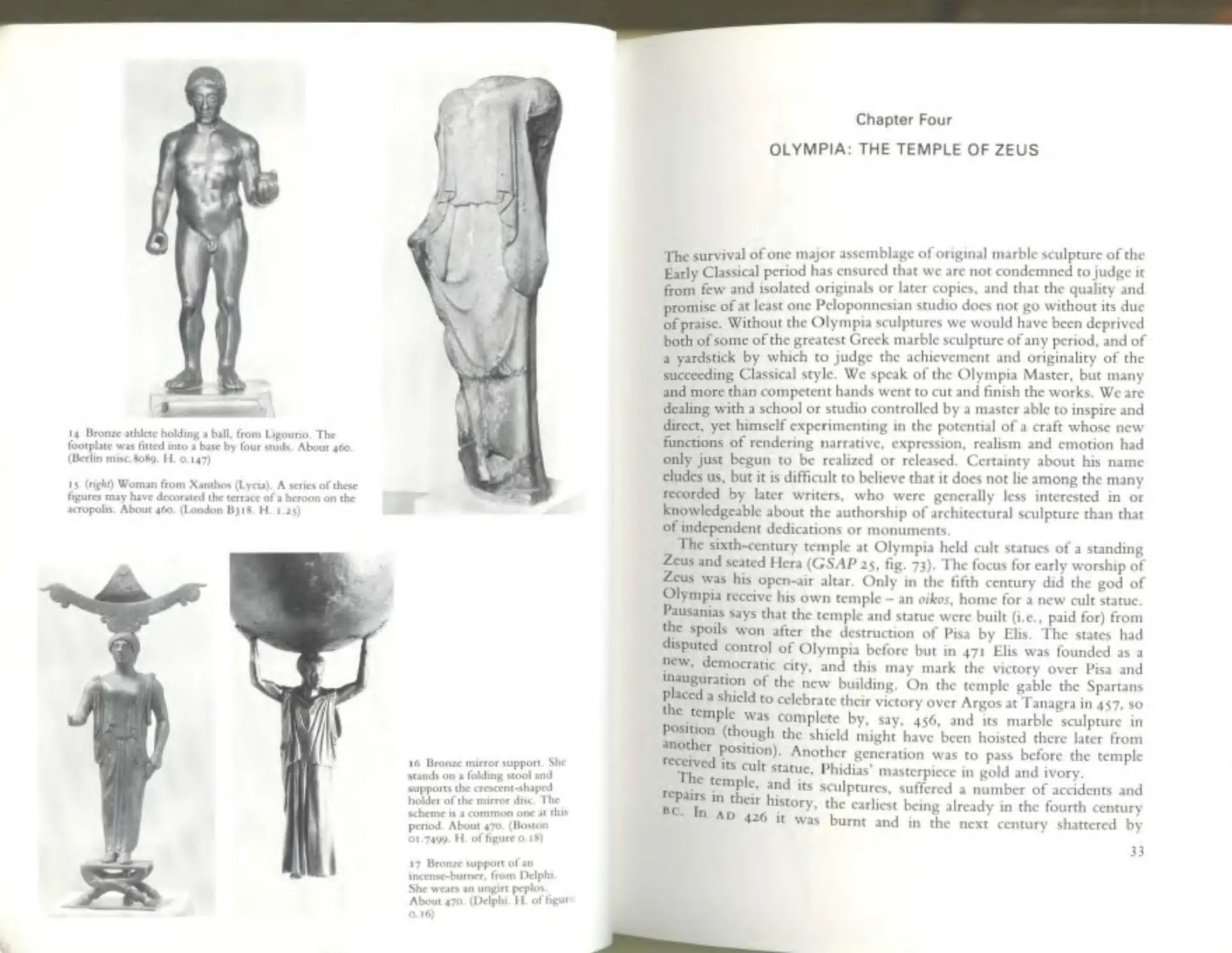

Chapt er Four

OLYMPIA: THE TEMPLE OF ZEUS

The surv i val of o n e major assemblage of original m arble sculpture o f the

Early Classical period has. c? su r cd that we arc not condemned to judge it

from few and isolated o n gmals or la ter coptcs, and that the quaht y and

promise of at least one Pclopo.n ncsia n studio does not go without itsdue

of prai se. With ou t the Olym pta scu lptures we would h ave been d epnvcd

bothofsome ofthe greatest Greek marblesculptureof any period, and of

a yardstick by which to j udge the achievement and originality o f the

succeeding Classical style. We speak of the O lympia M aster, but many

and more than competent hands went to cut and finish the works. We are

dealing with a school or studio con tro lled by a master able to in spire and

direct, yet himself experimenting in the potential of a craft whose new

fu nctions of rende ring narrative, expression, rea lism and emotio n had

only just begun to be realized or rel eased. Certainty about his n ame

eludes us, but it is difficult to believe that it does not lie among the m any

recorded by later w rite rs, who were generally less interes ted in or

knowledgeable about the authorship of architectu ral sculpture than that

of independent d edications o r monumen ts.

The si xth- ce ntury temple at O lympia held cult statues of a standing

Zeus and seated Hcra (GSAP 25, fi g. 73). The focus fo r early worship of

Zeus was his o pen-air alta r. Only in the fifth century did the god of

O lympia receive hi s own temple - an oikos, home fo r a new cult statue.

Pausanias says that the te mple and statue were built (i.e . , paid fo r) from

the sp01ls won after the destruction of Pi sa by Elis. T he stat es had

dtsputcd control of O lympia before but in 471 Elis was founded as a

new, democratic city, and this may m ark the victory over Pi sa an d

tna uguratwn of the new building. On the tem ple gable the Spa rtans

~laced a shtcld to celebrate their victory over Argos at Tanagra in 457, so

t lC. tem ple was com plete by, say, 456, and its marble sculpture in

posm on (though the shield might have been hoisted there la ter from

anotherpo·· )A h

.

.

SltJon . not er gene ration was to pass before the temple

rc:;:~ved tts cu lt st atue, Ph id ias' m asterpiece in gold an d ivory.

. e temple , and its sculptu res, su ffered a number of accide nts and

rcpatrs 111 their h .

hI"b.I

.

8c1

ts tory, t c ca r test emg a ready m the fourth century

·

n A 0 426 1t was burnt and in the next century shattered by

33

A

l

c

D

B

K

G

11

F0

M

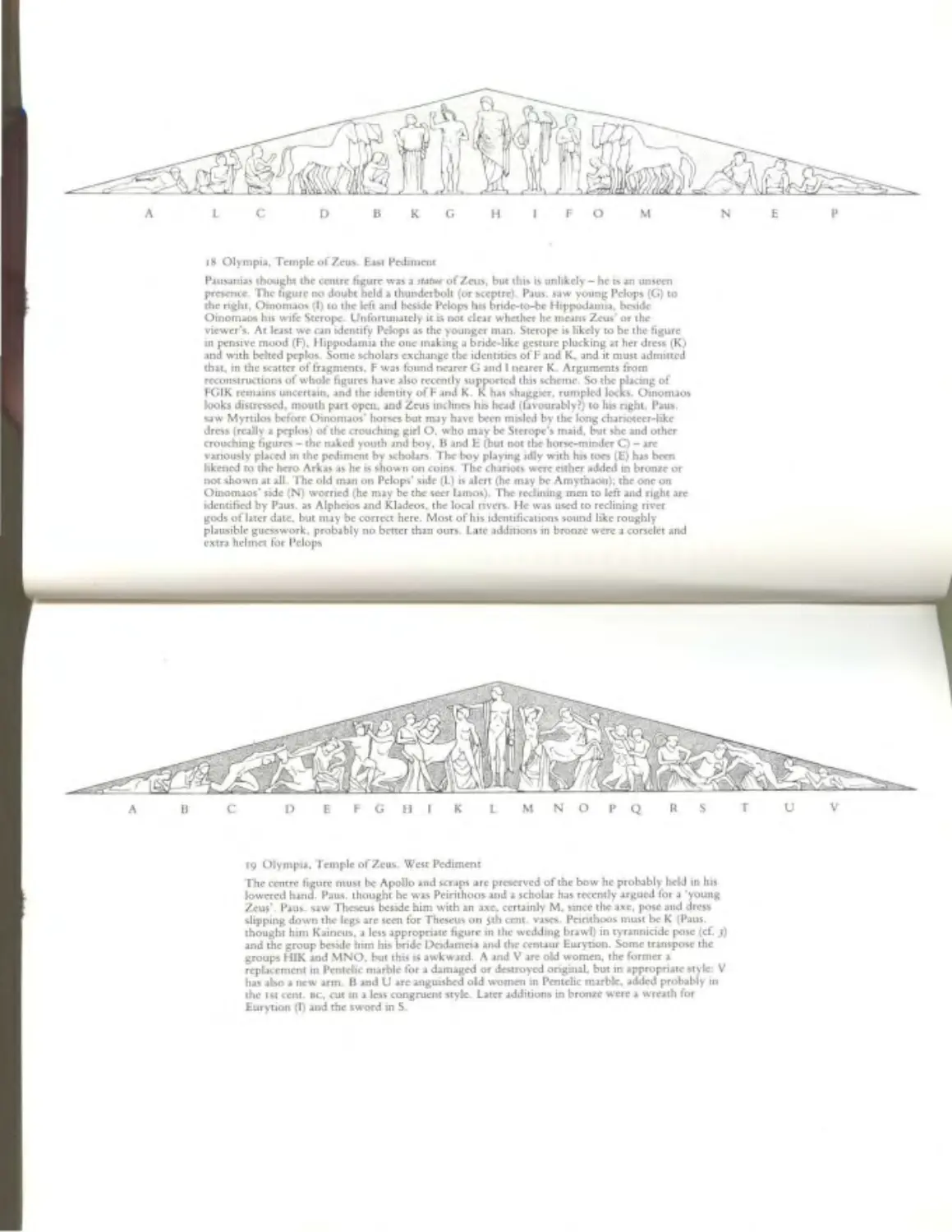

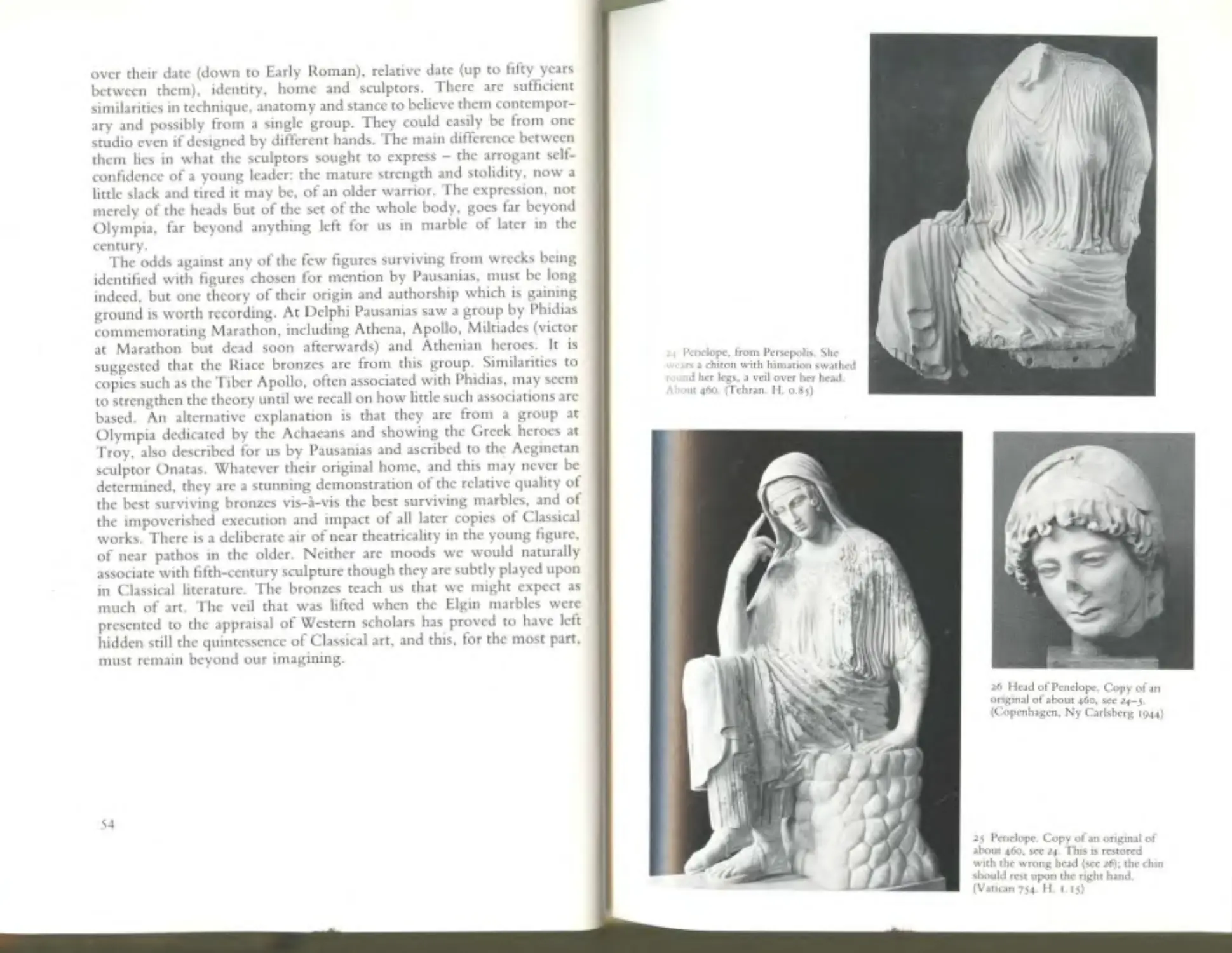

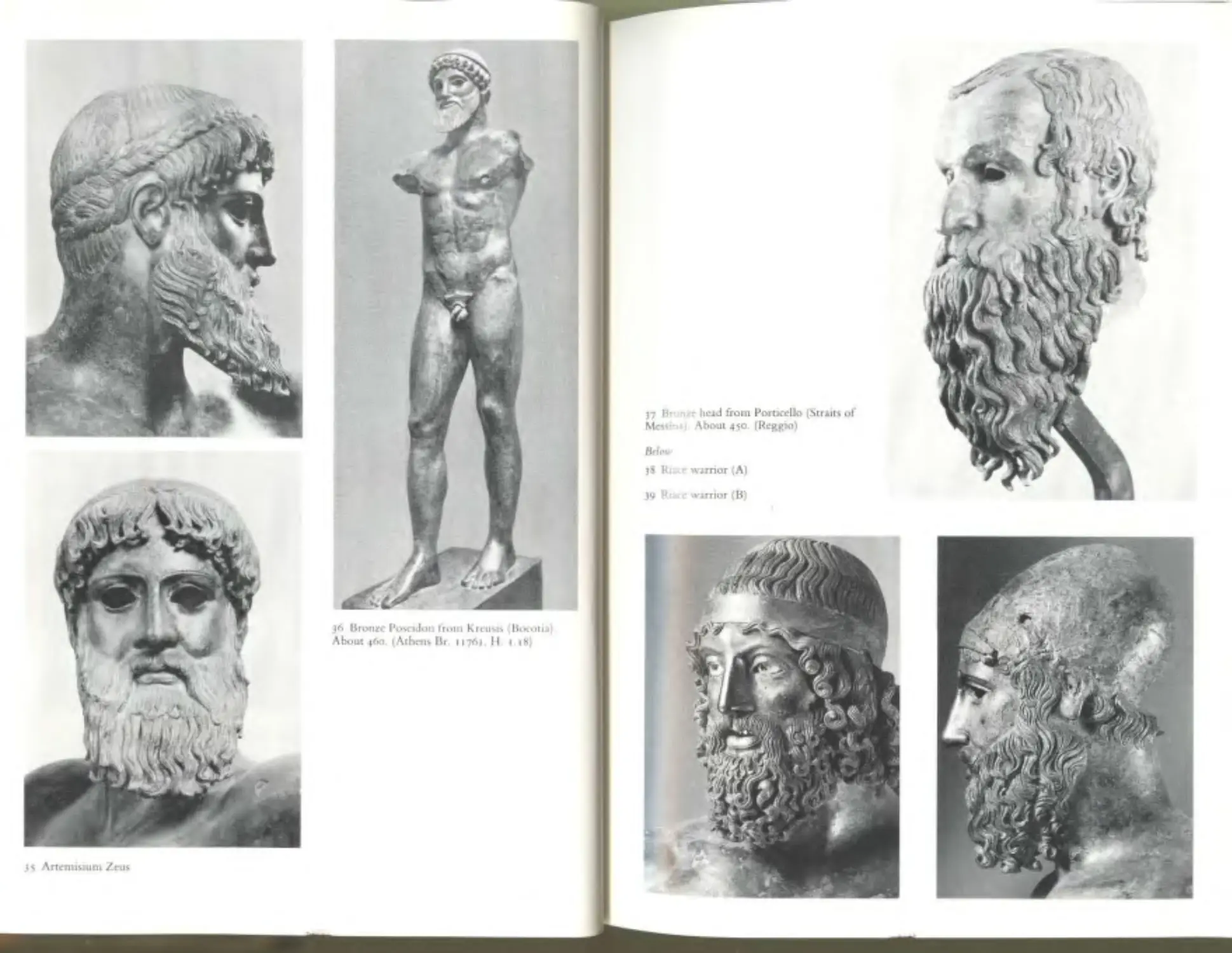

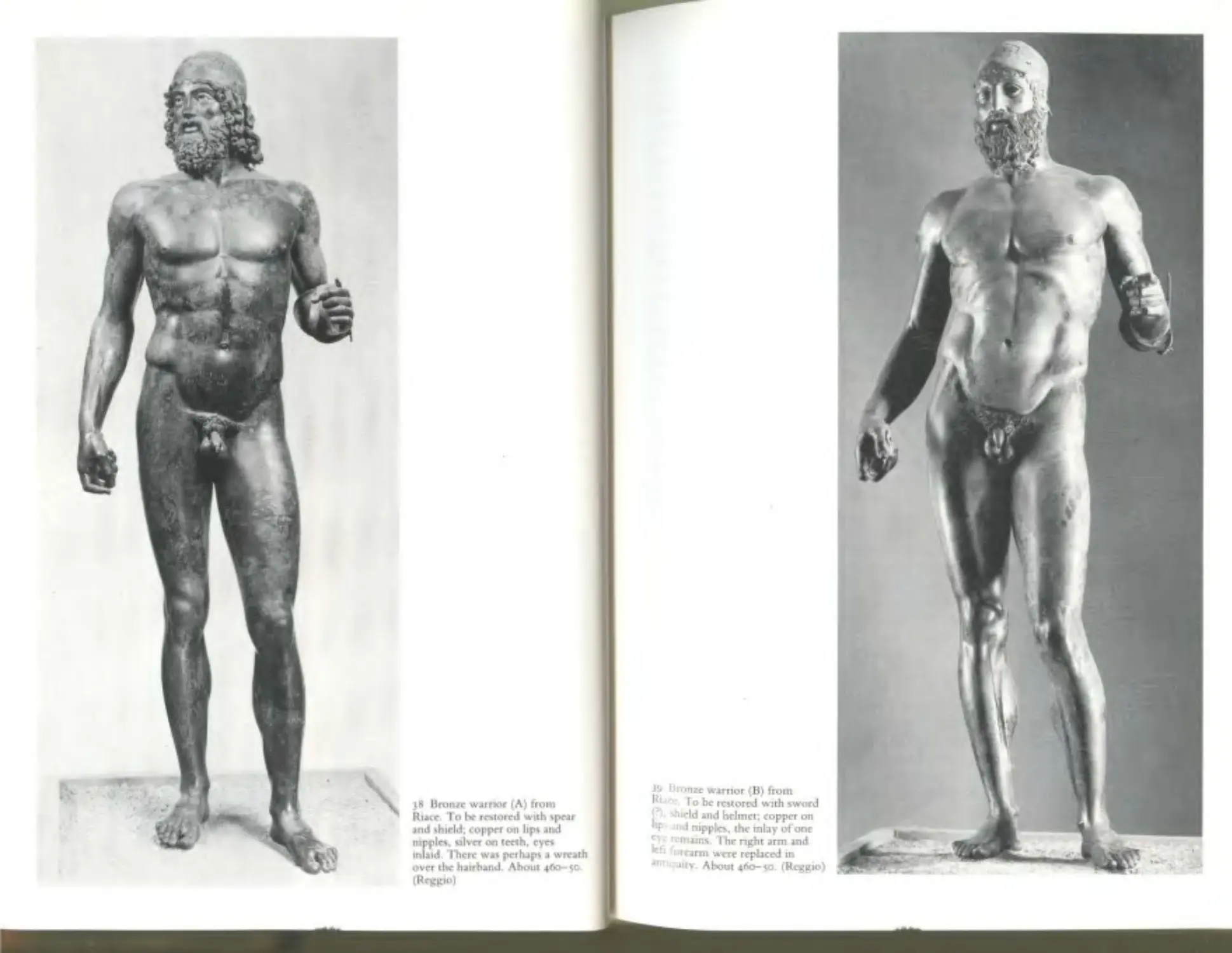

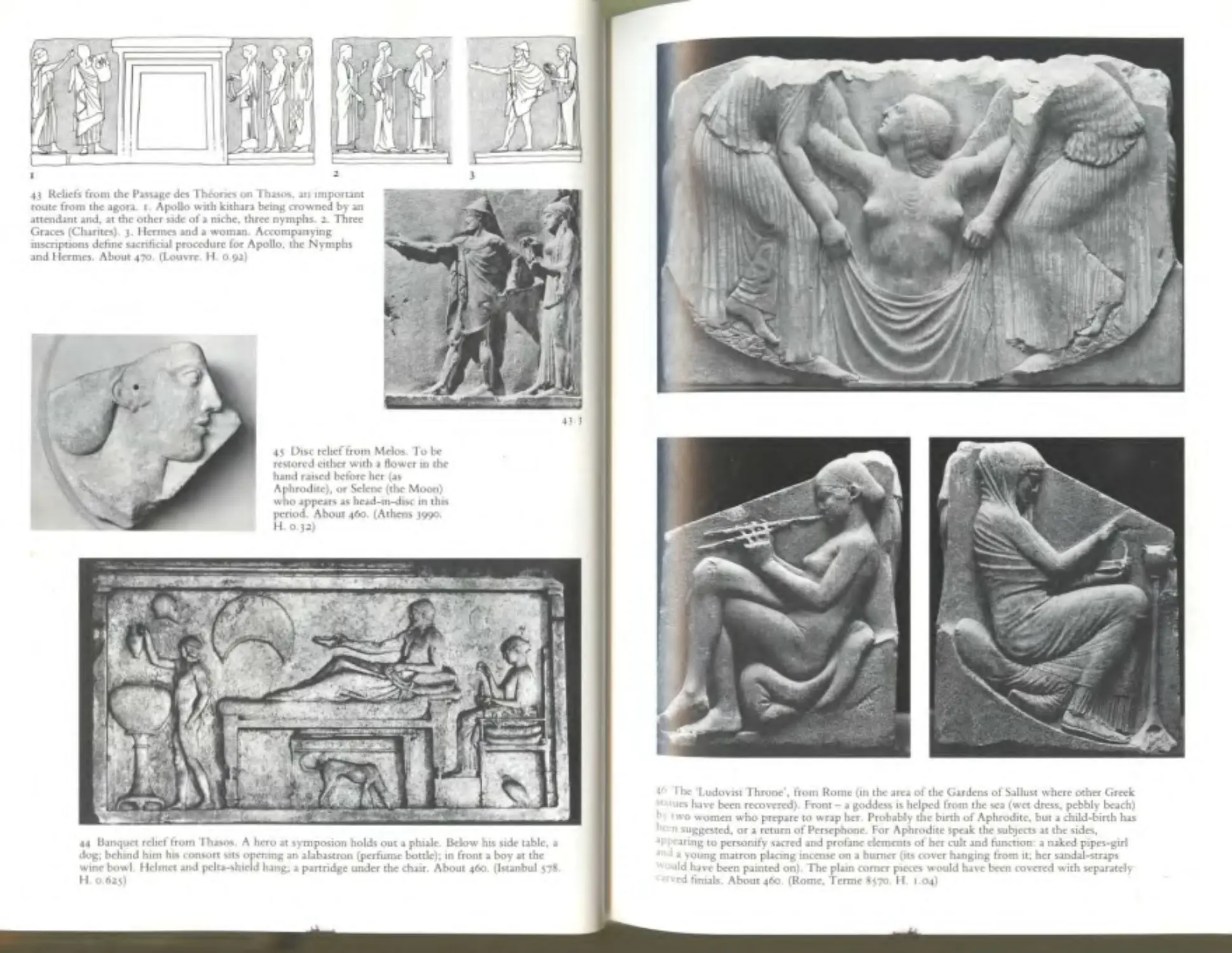

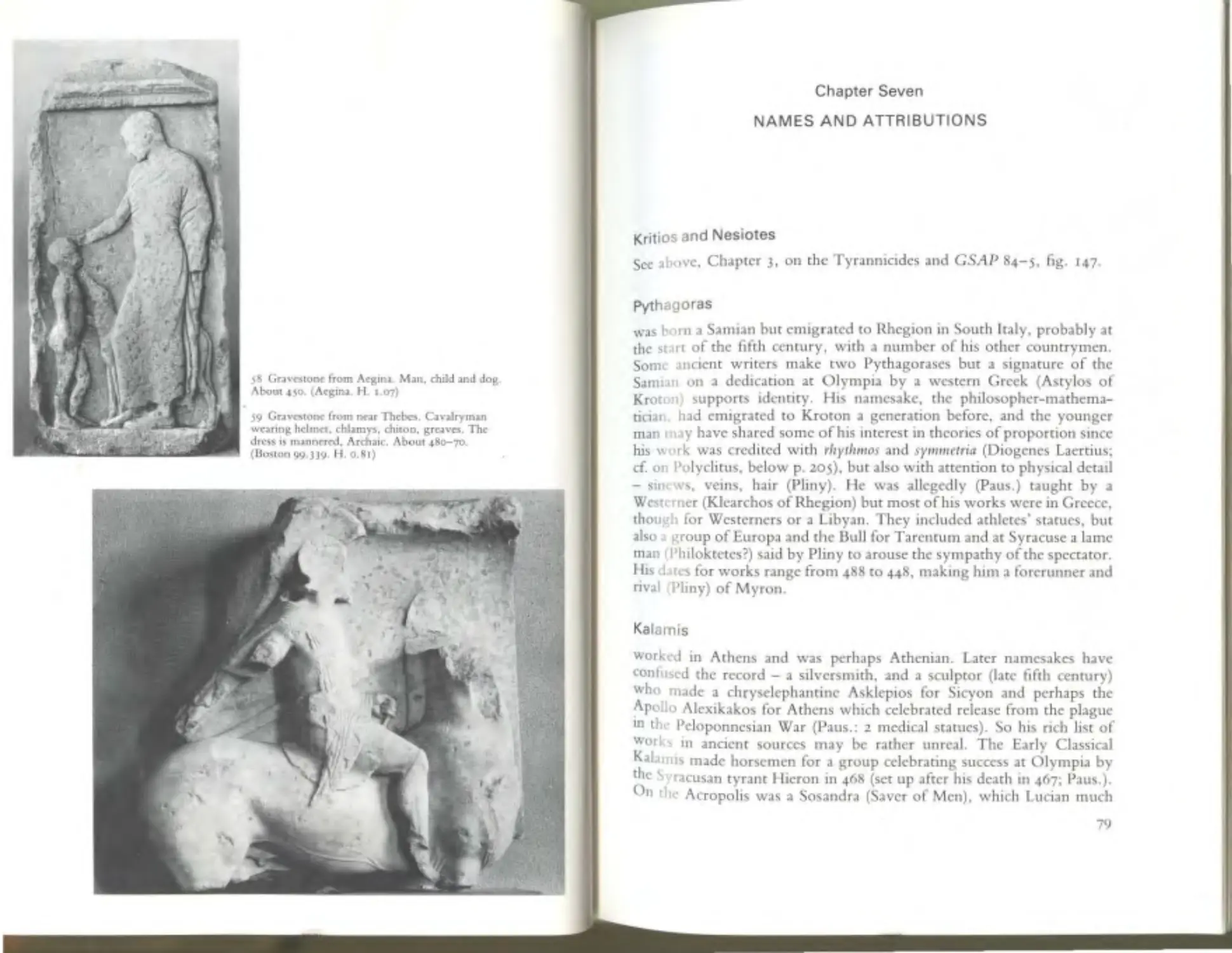

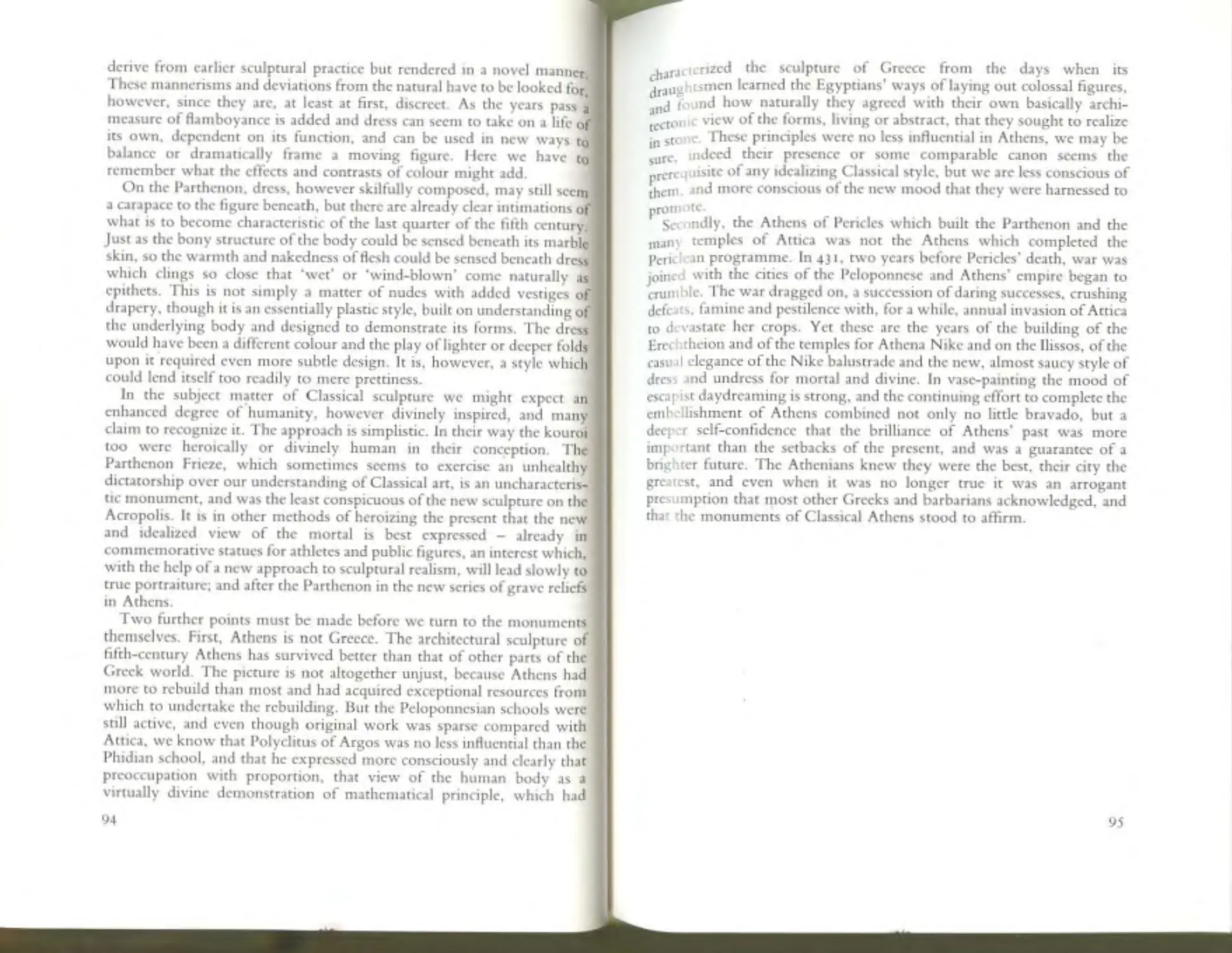

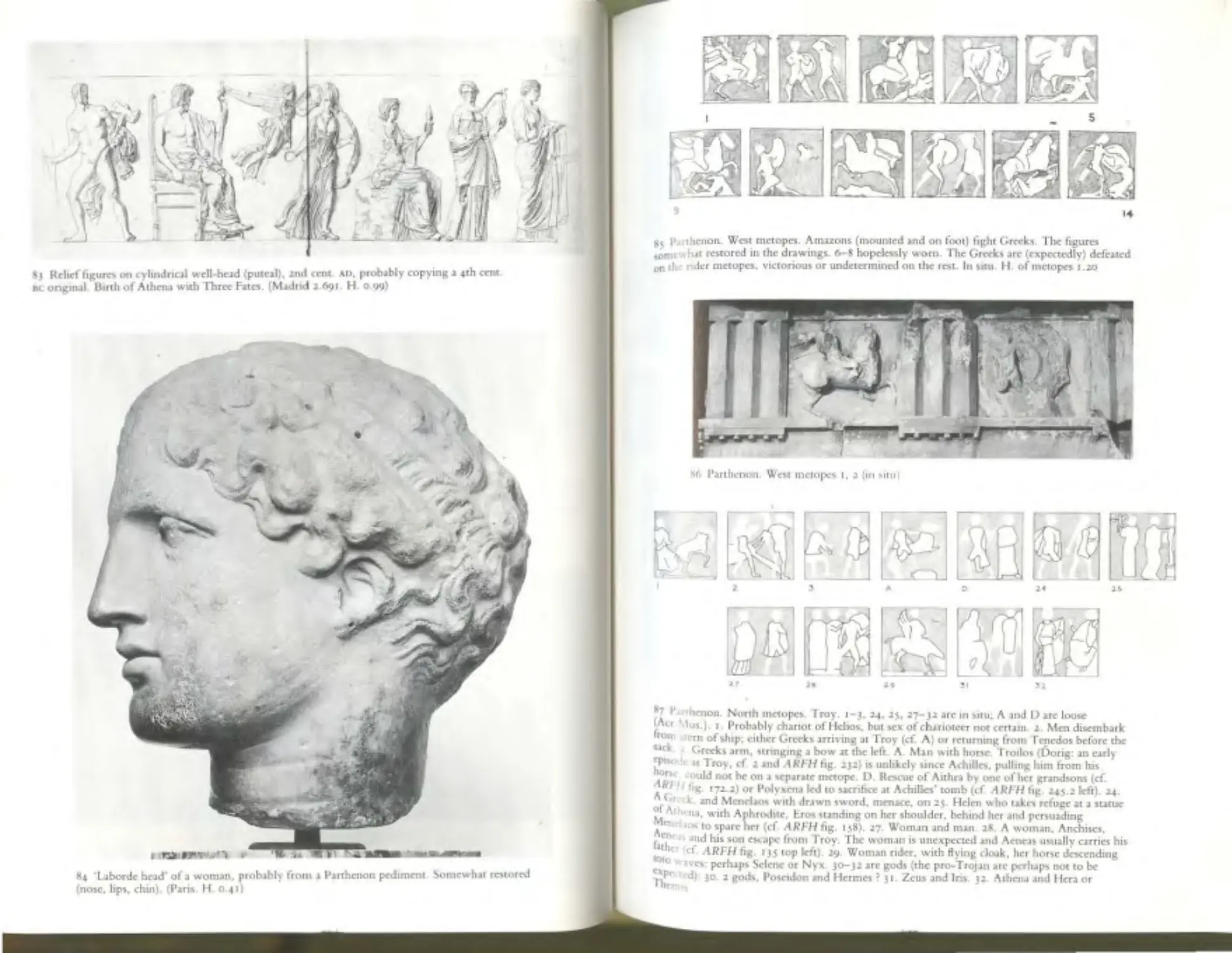

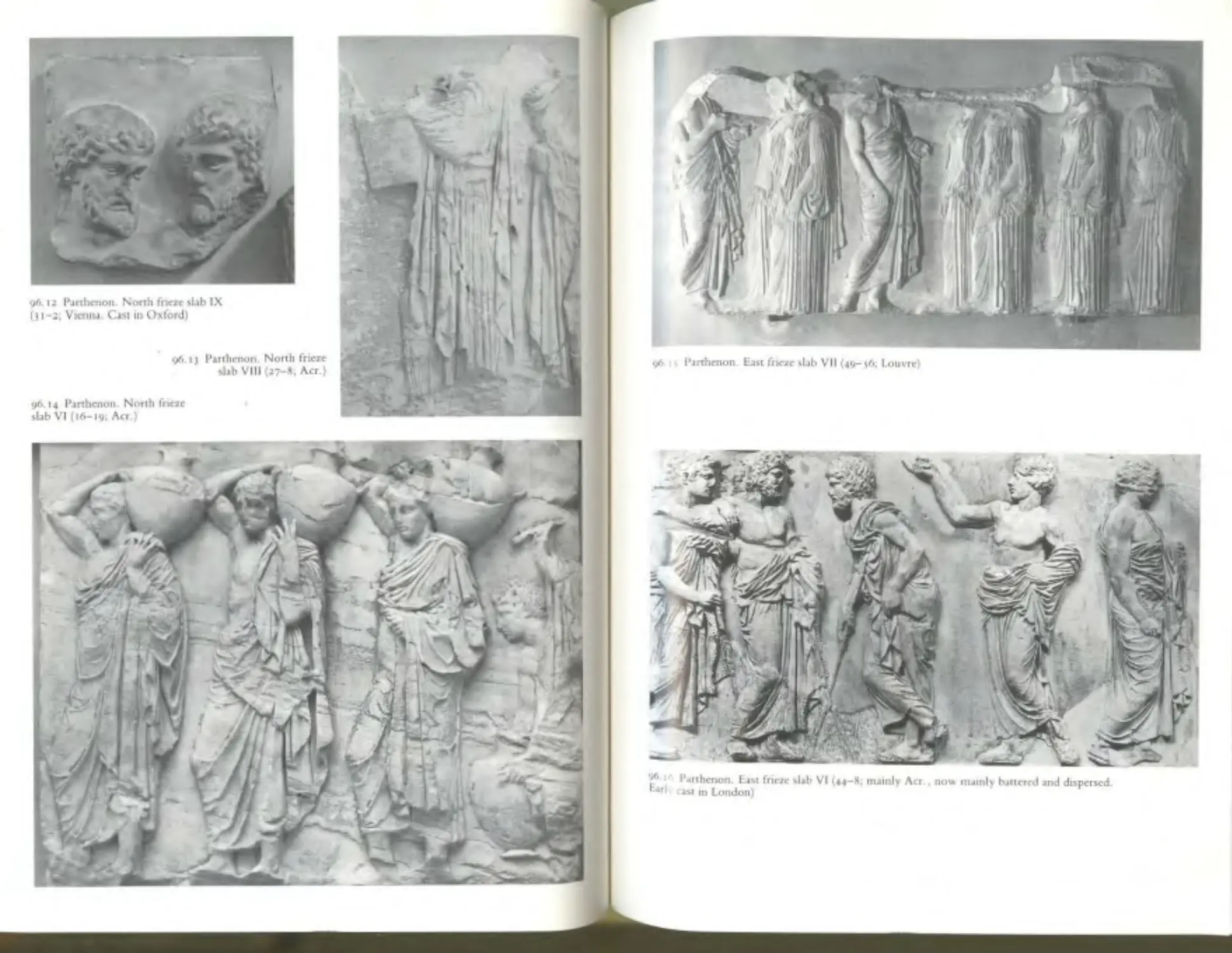

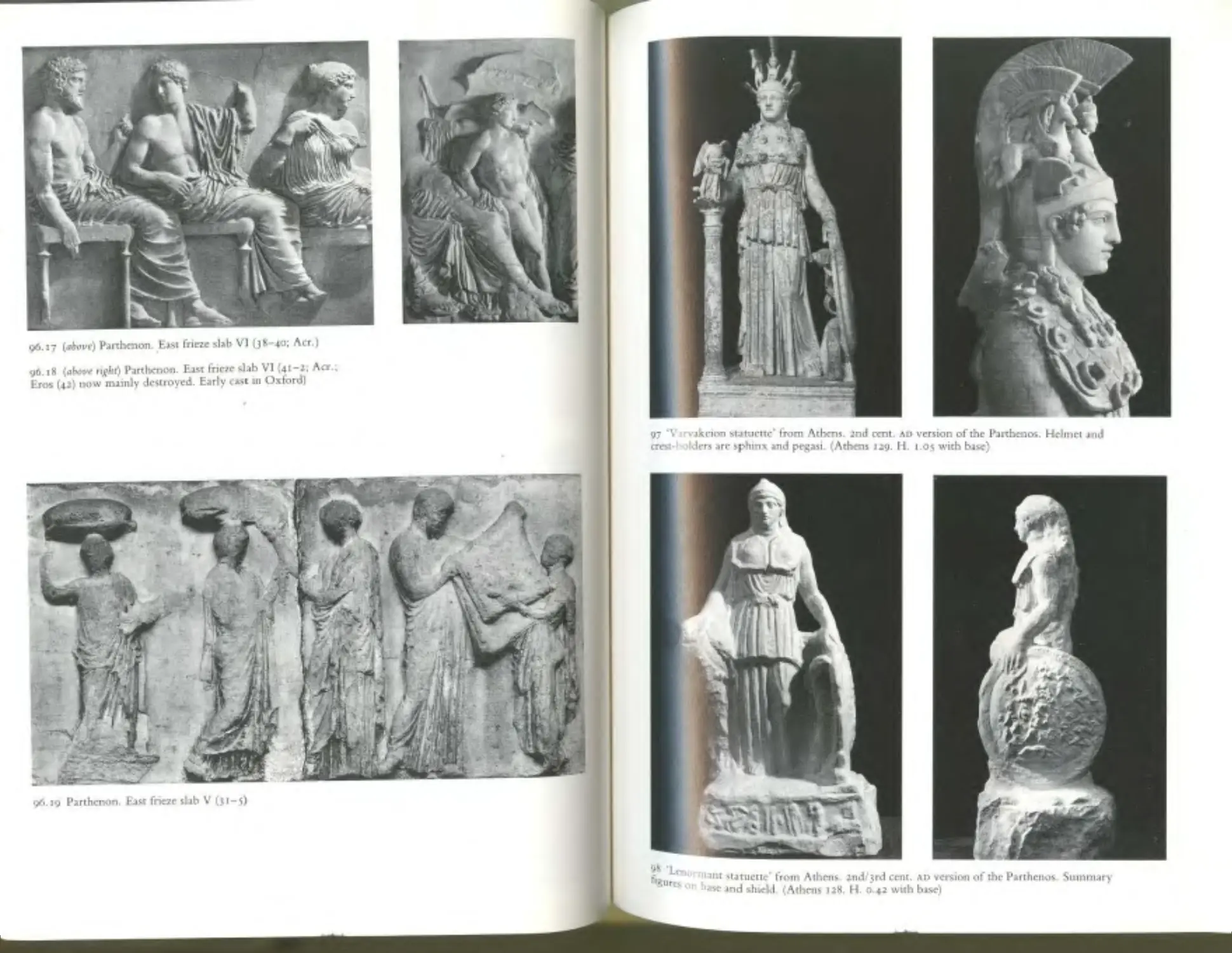

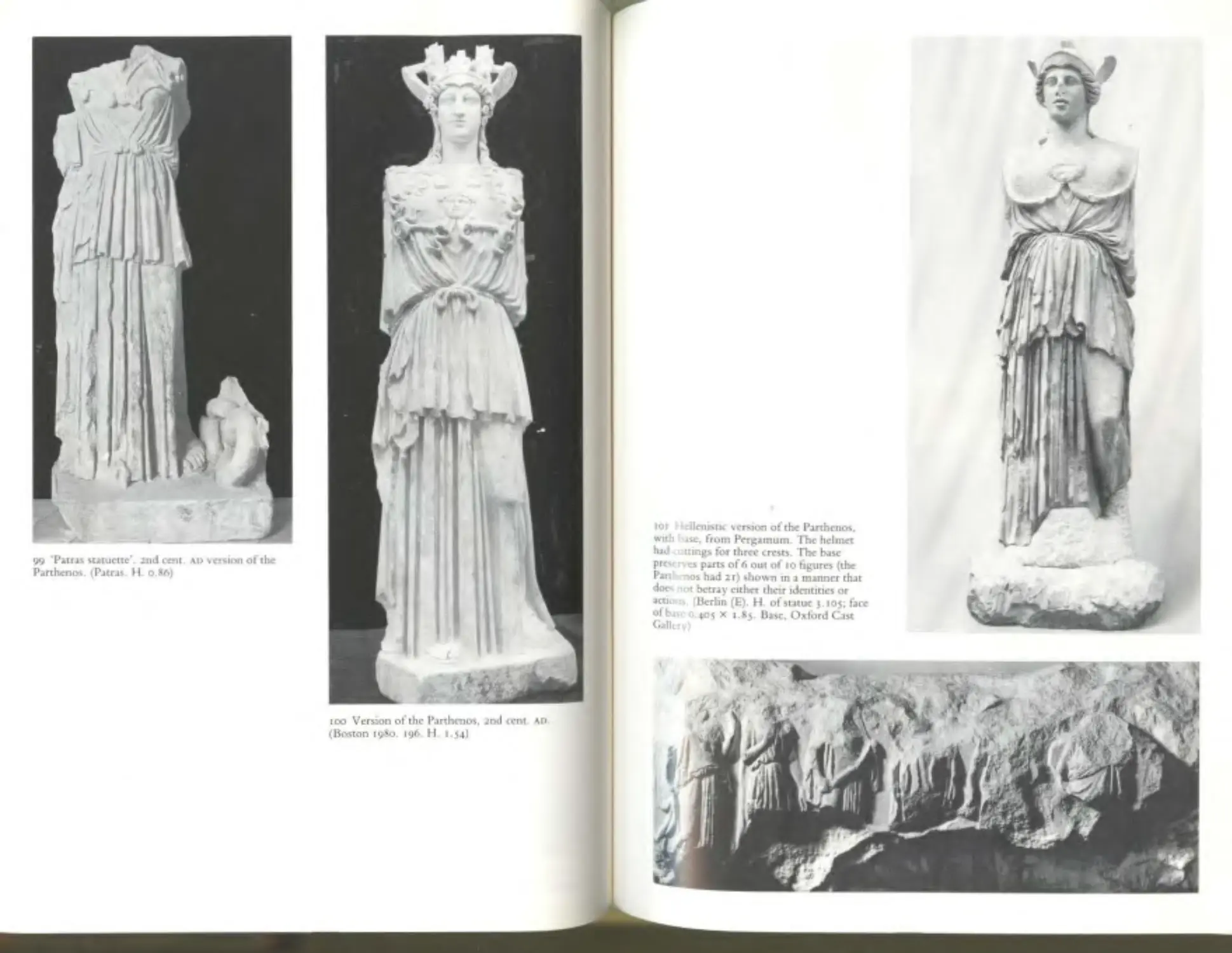

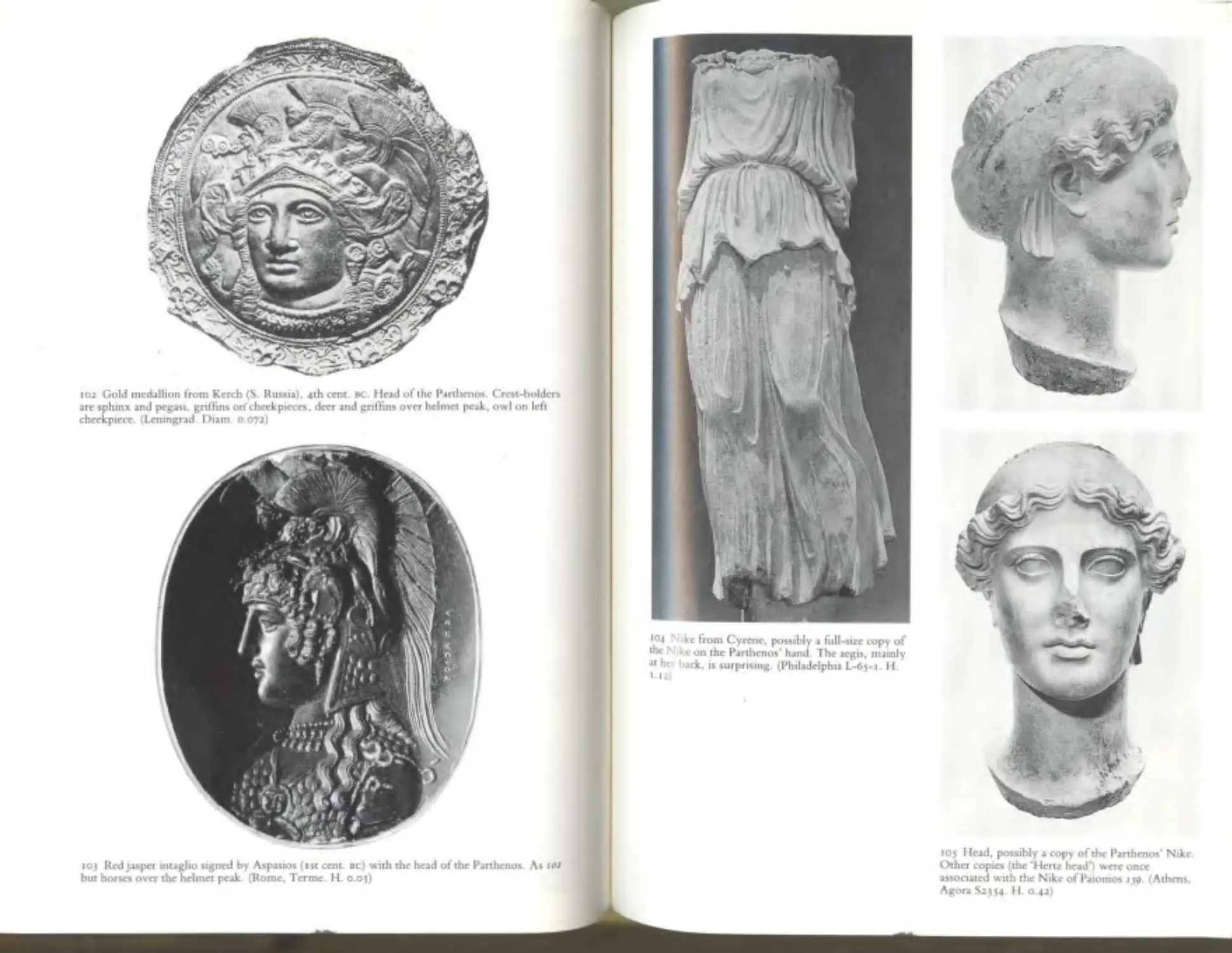

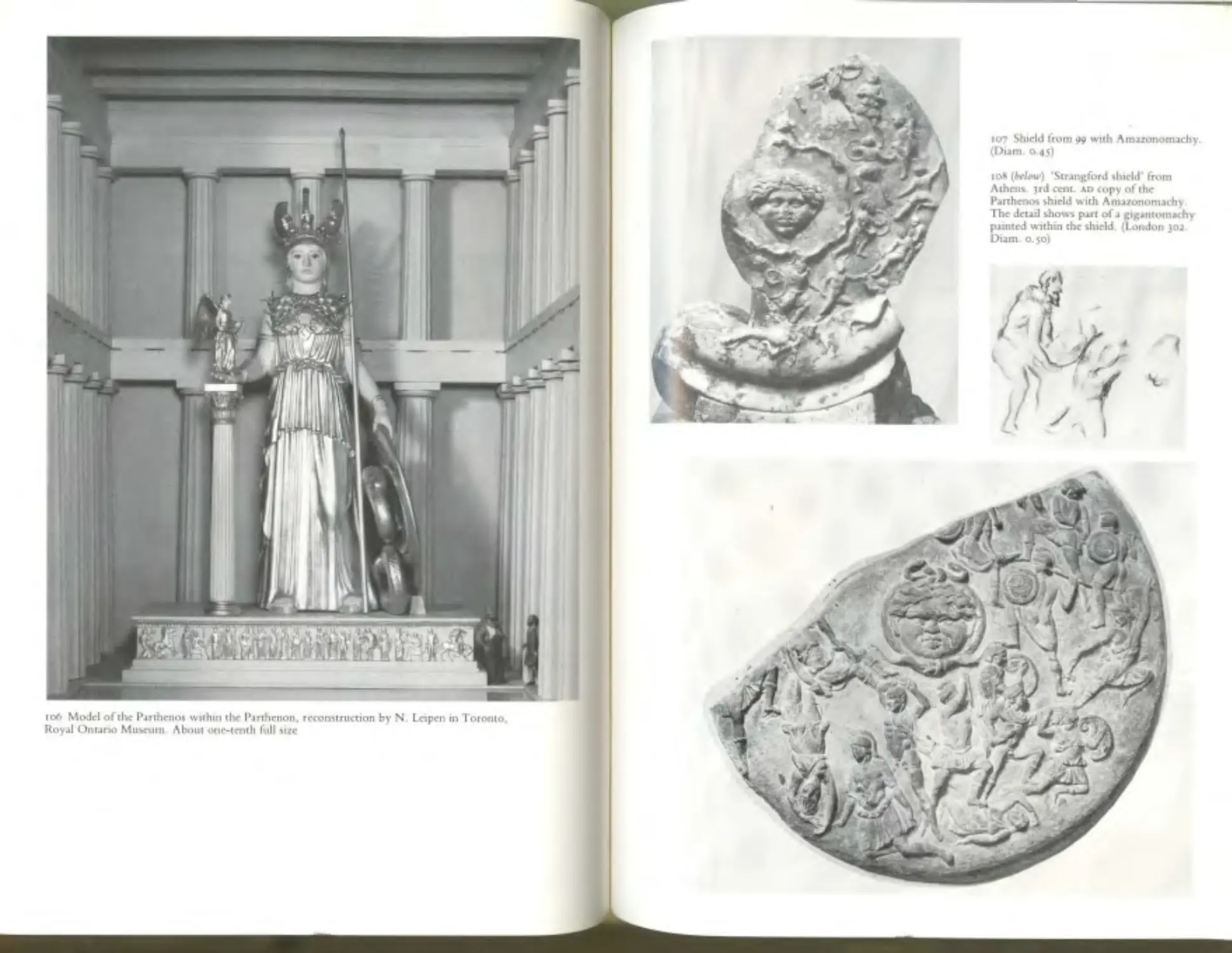

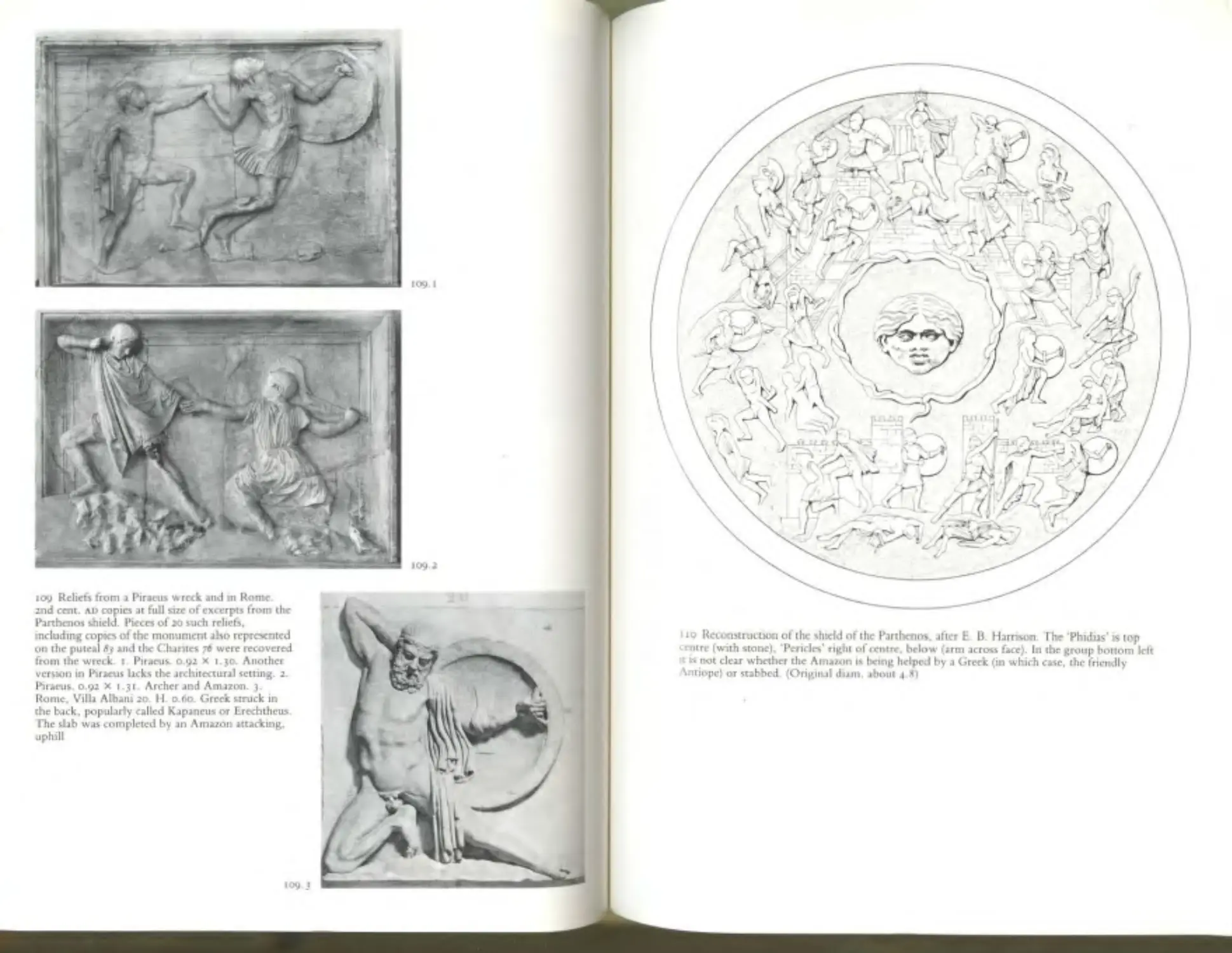

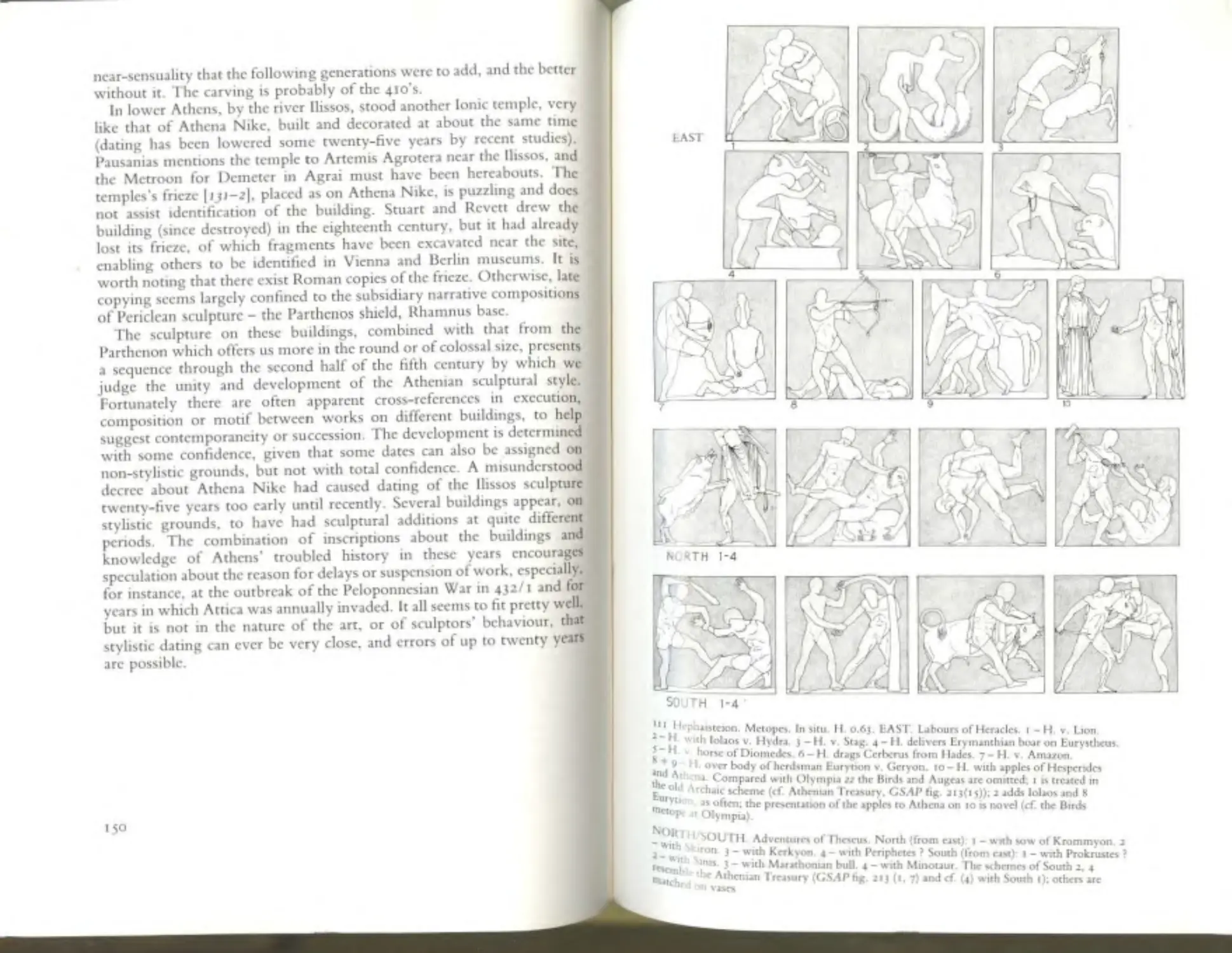

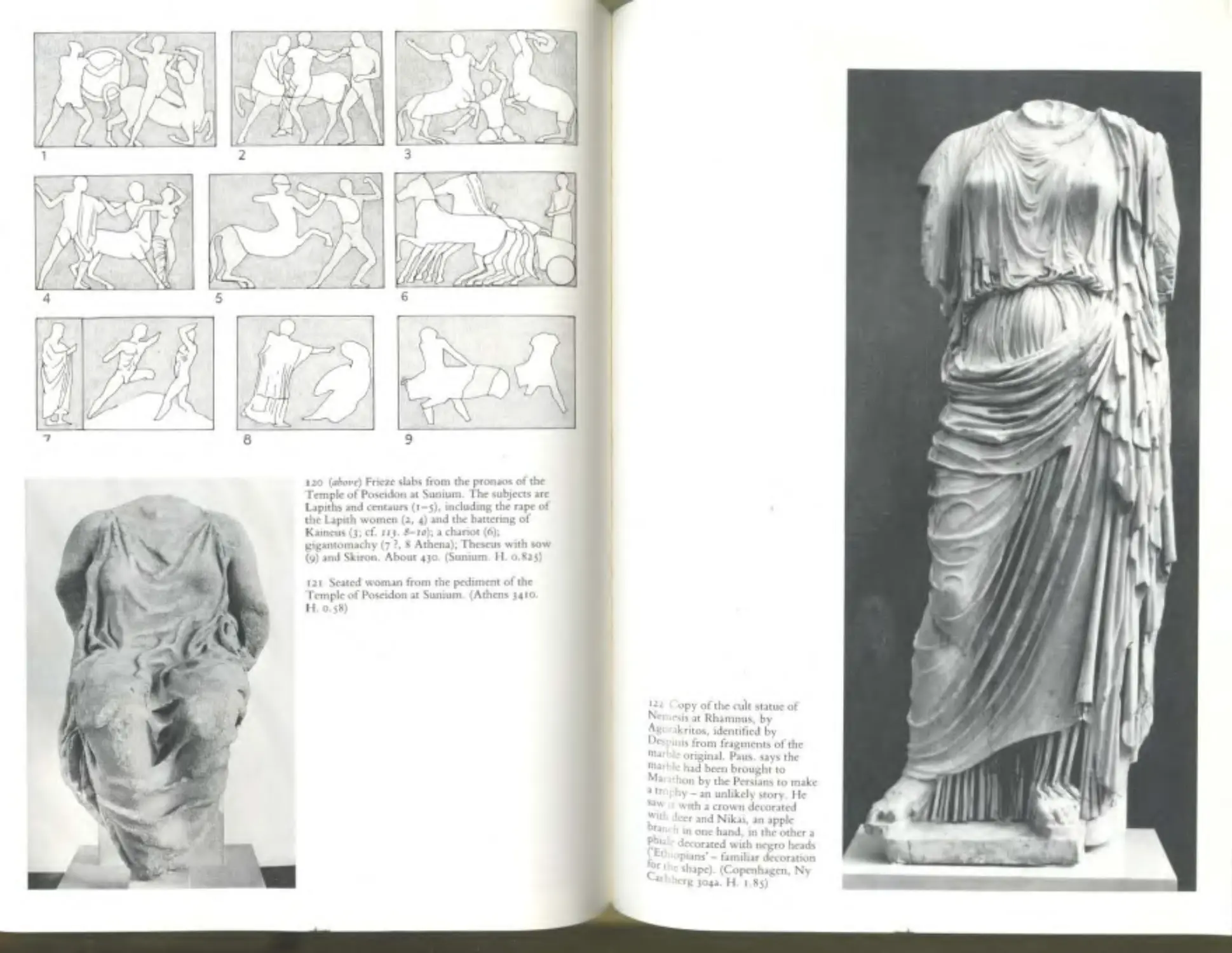

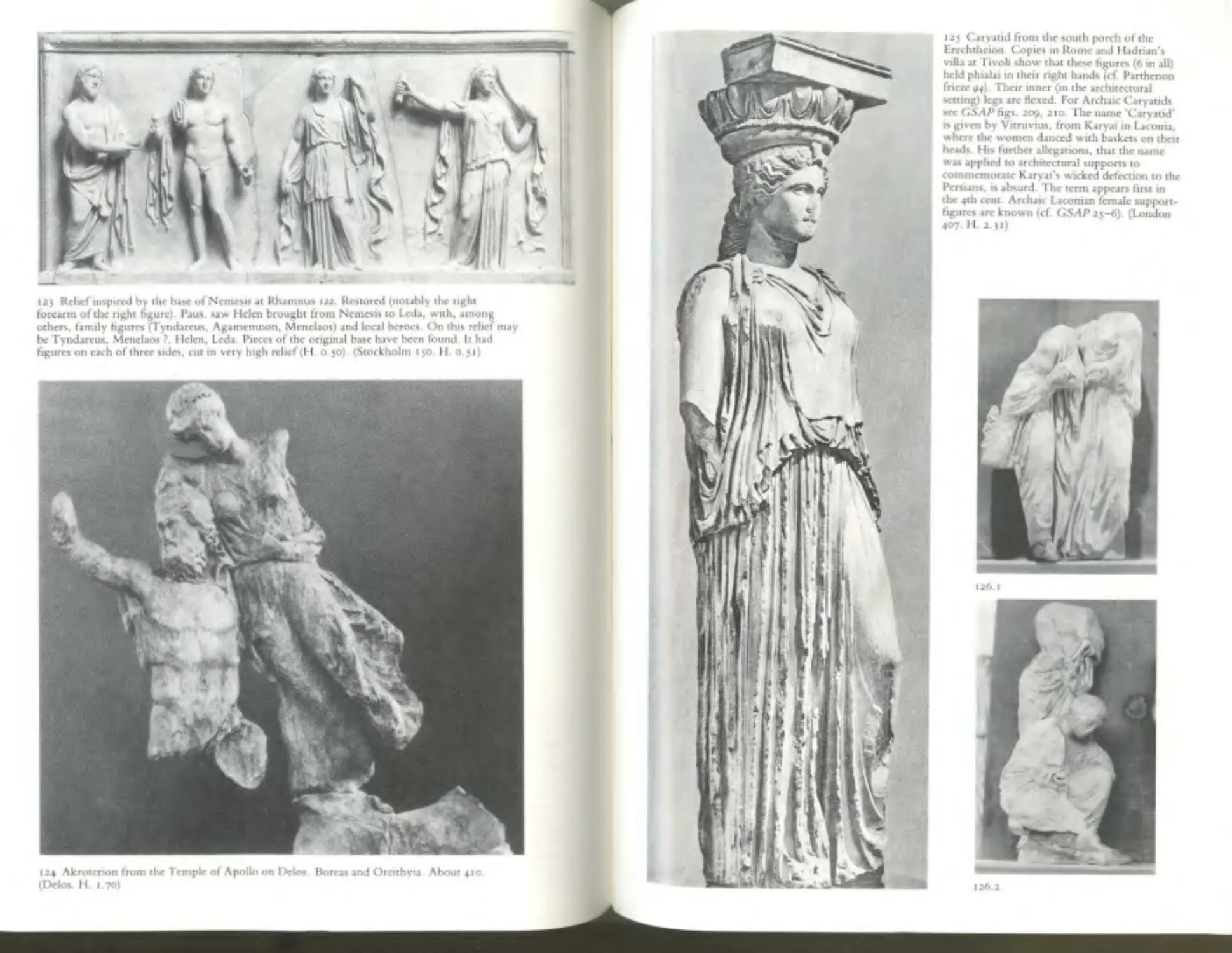

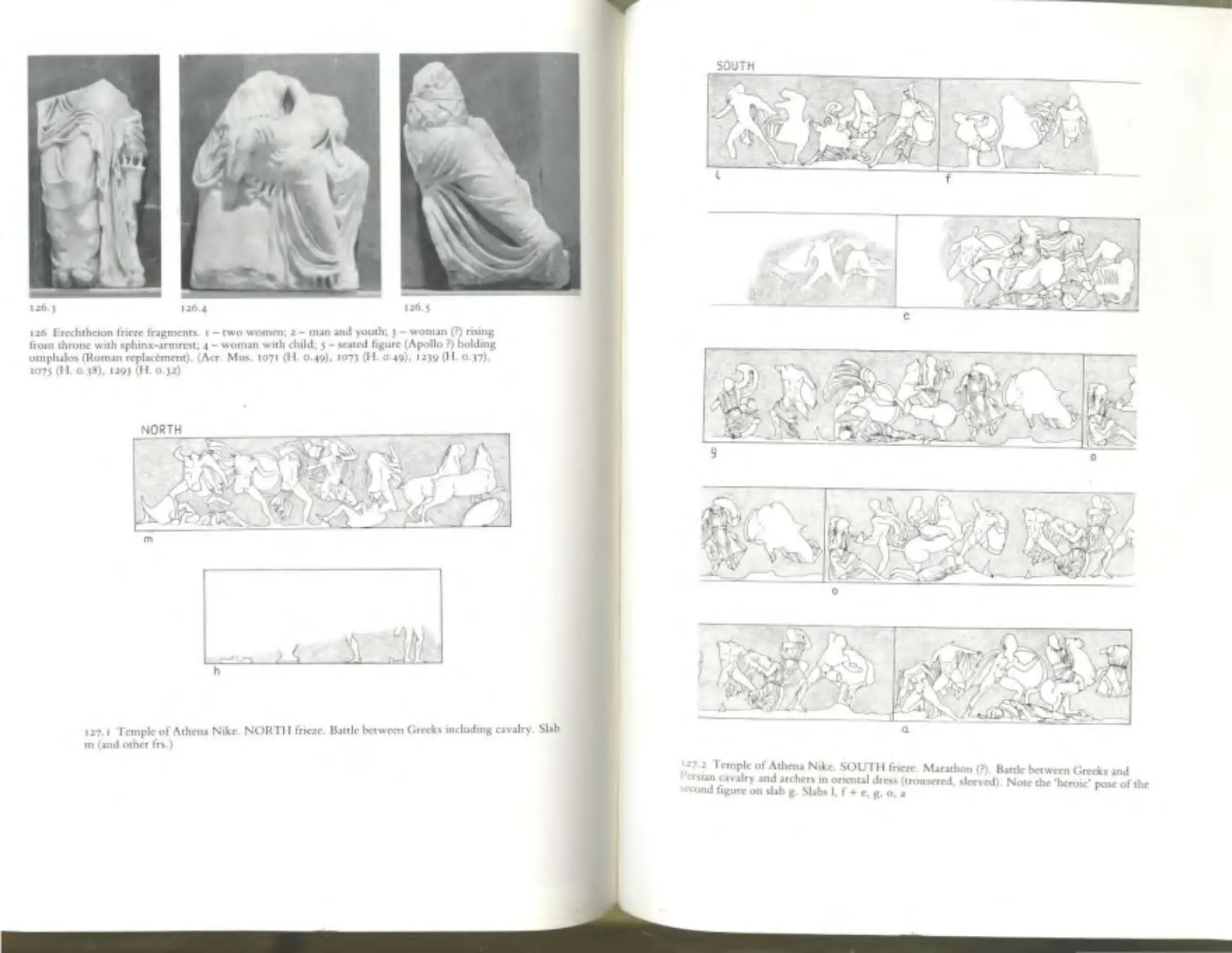

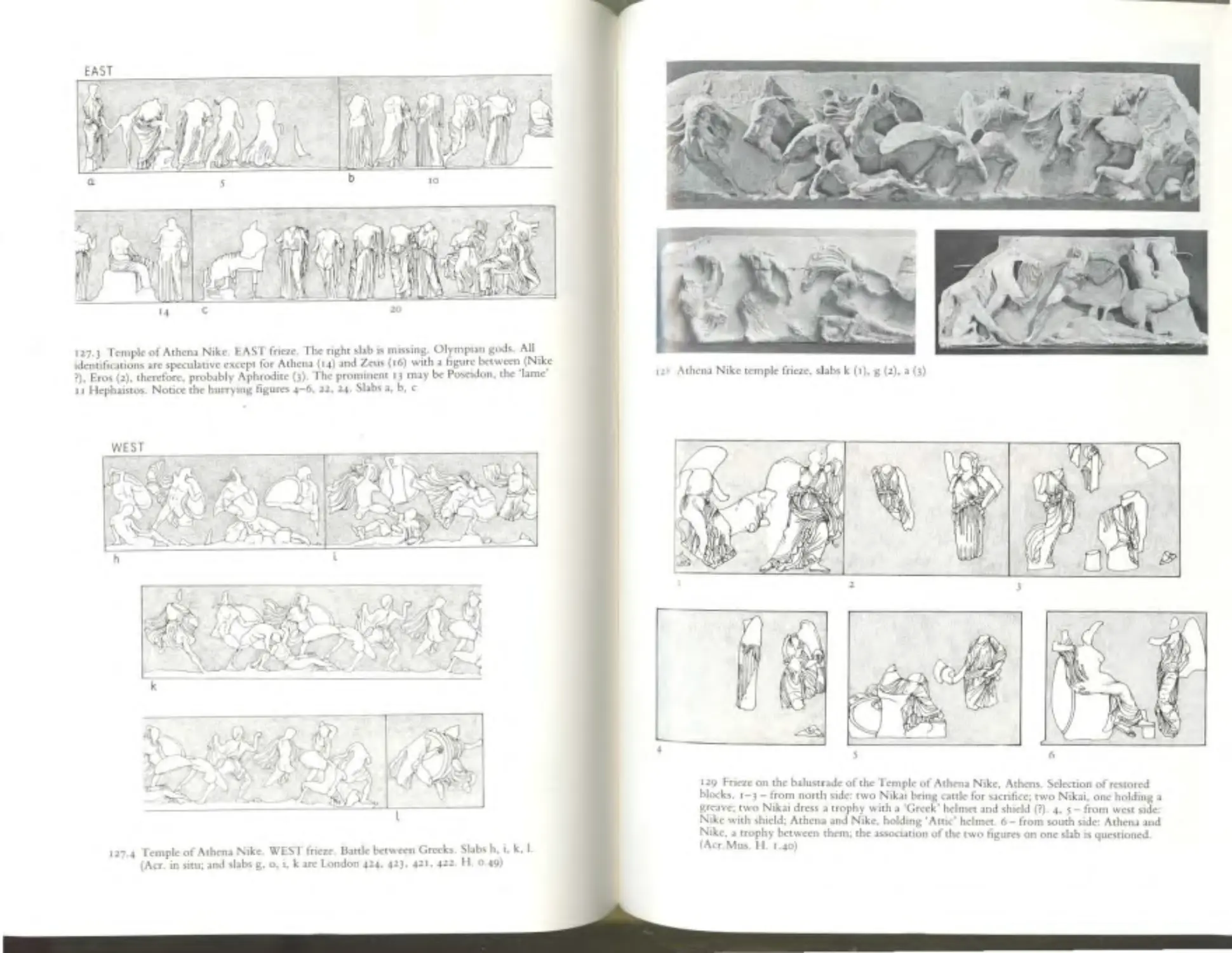

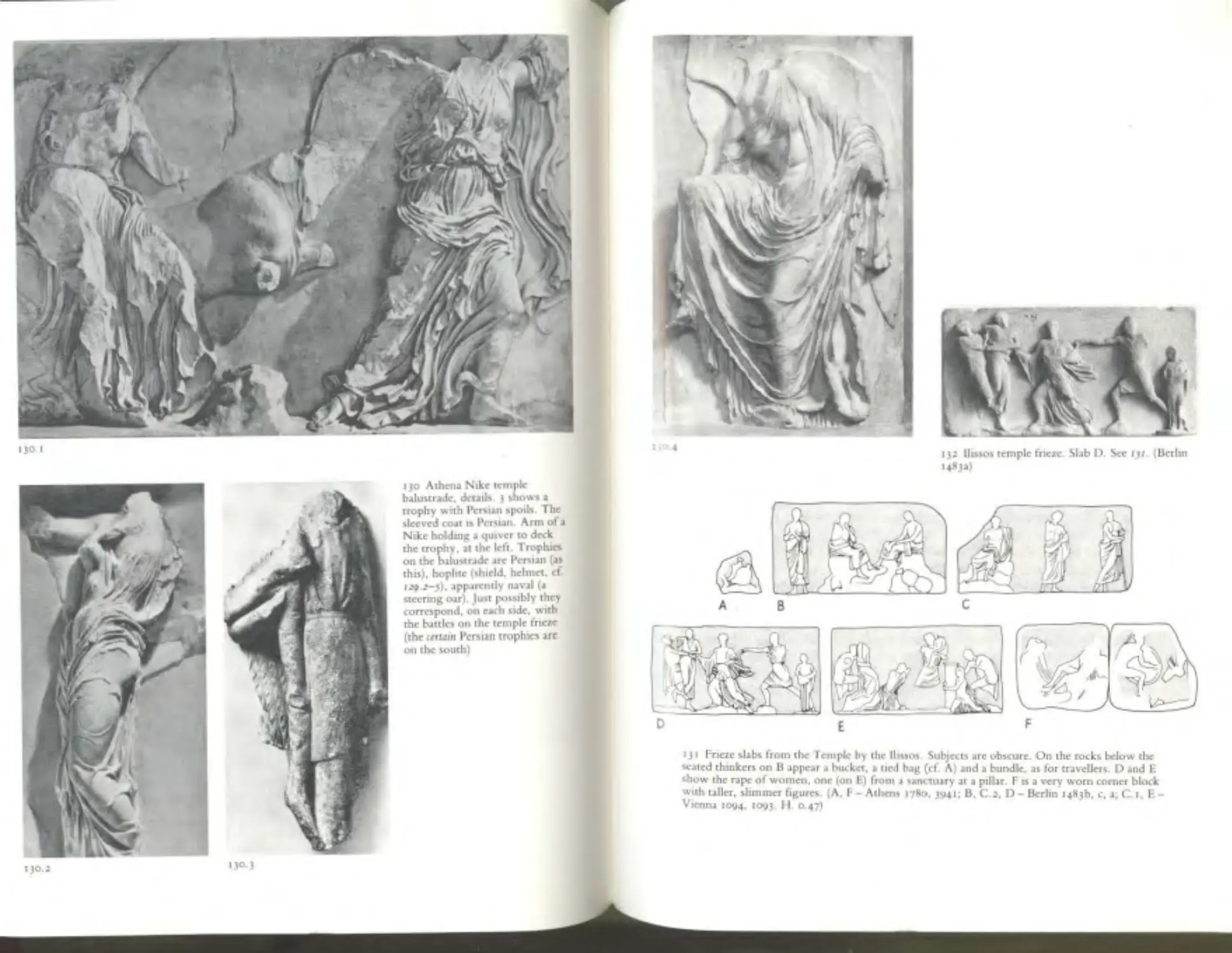

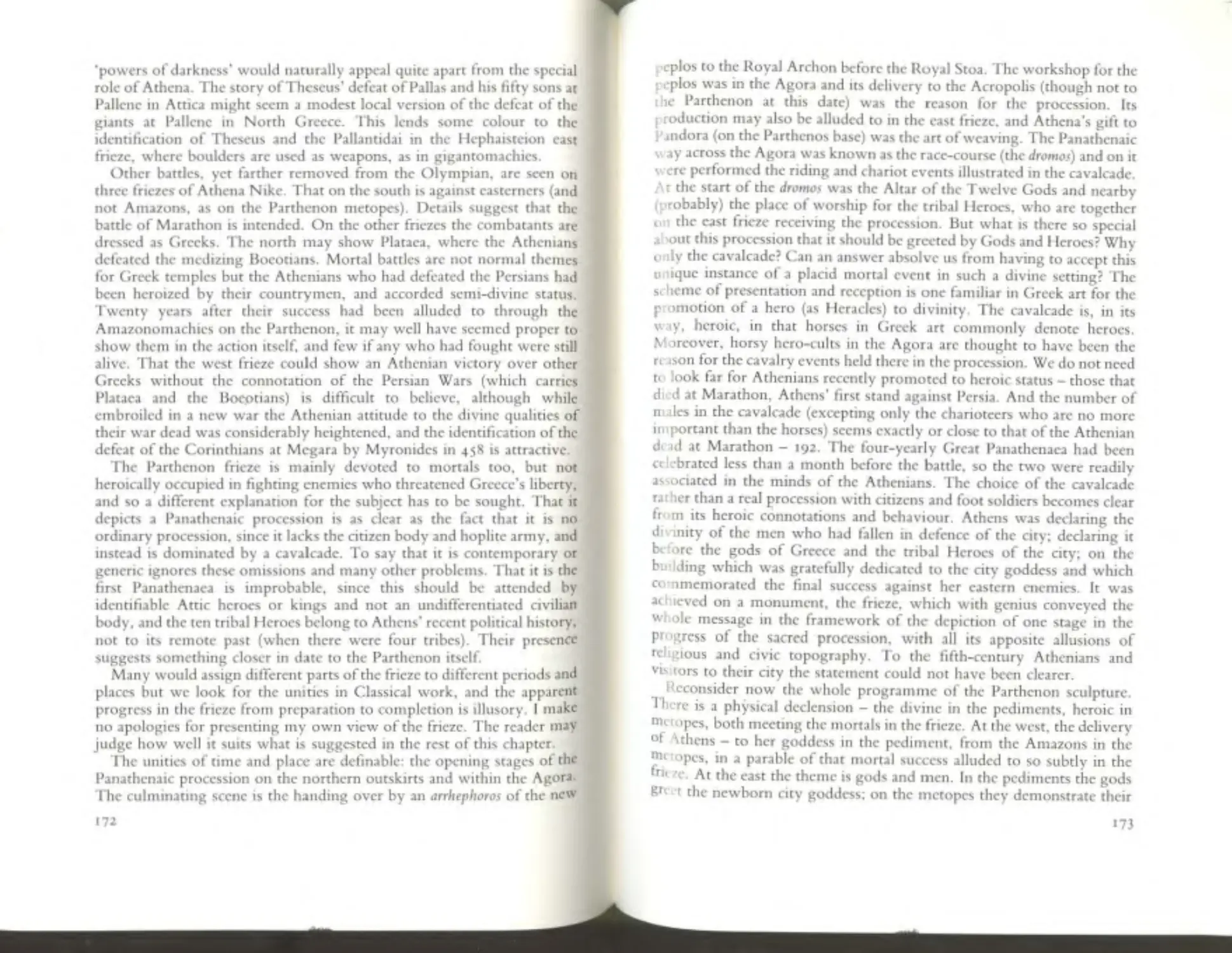

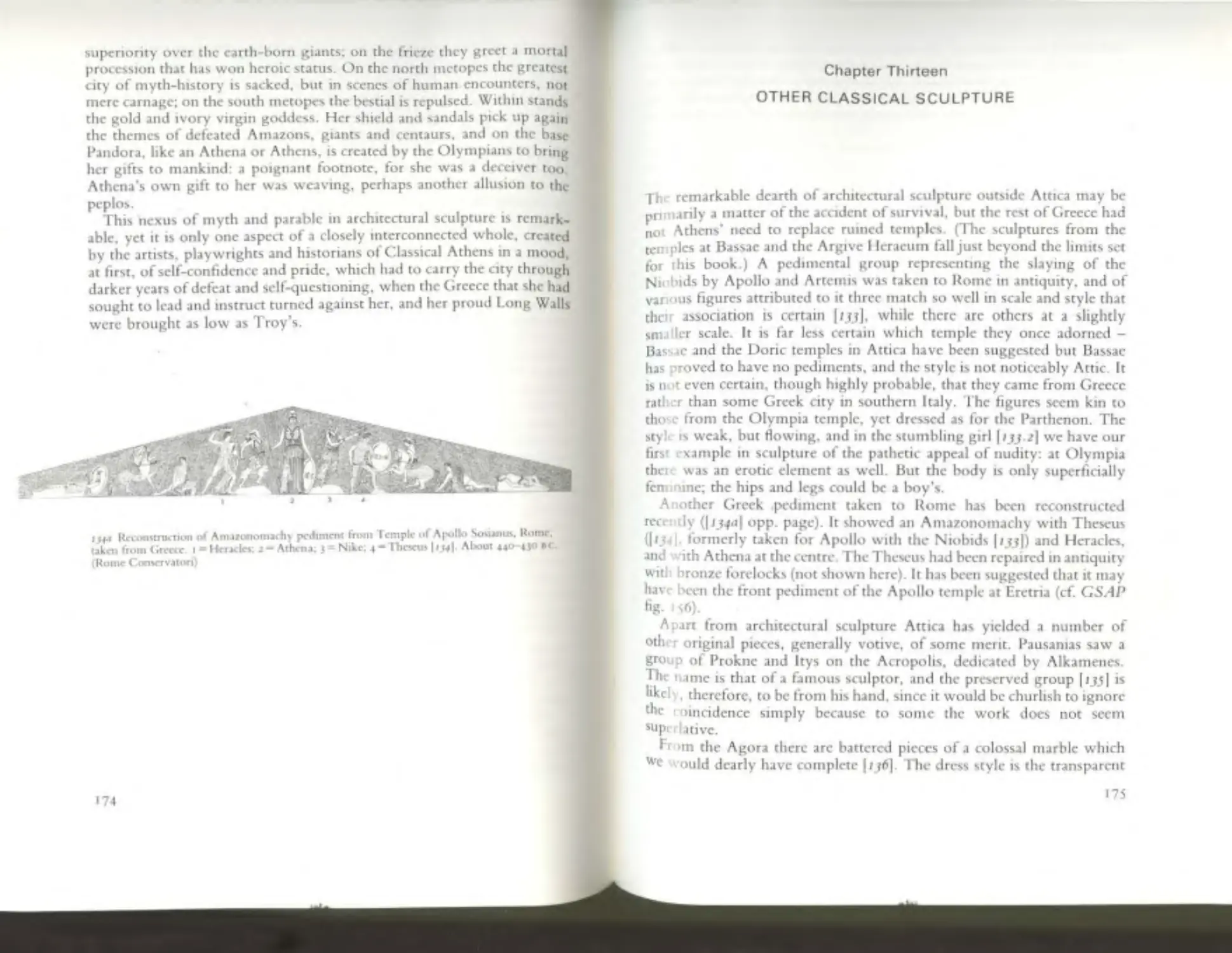

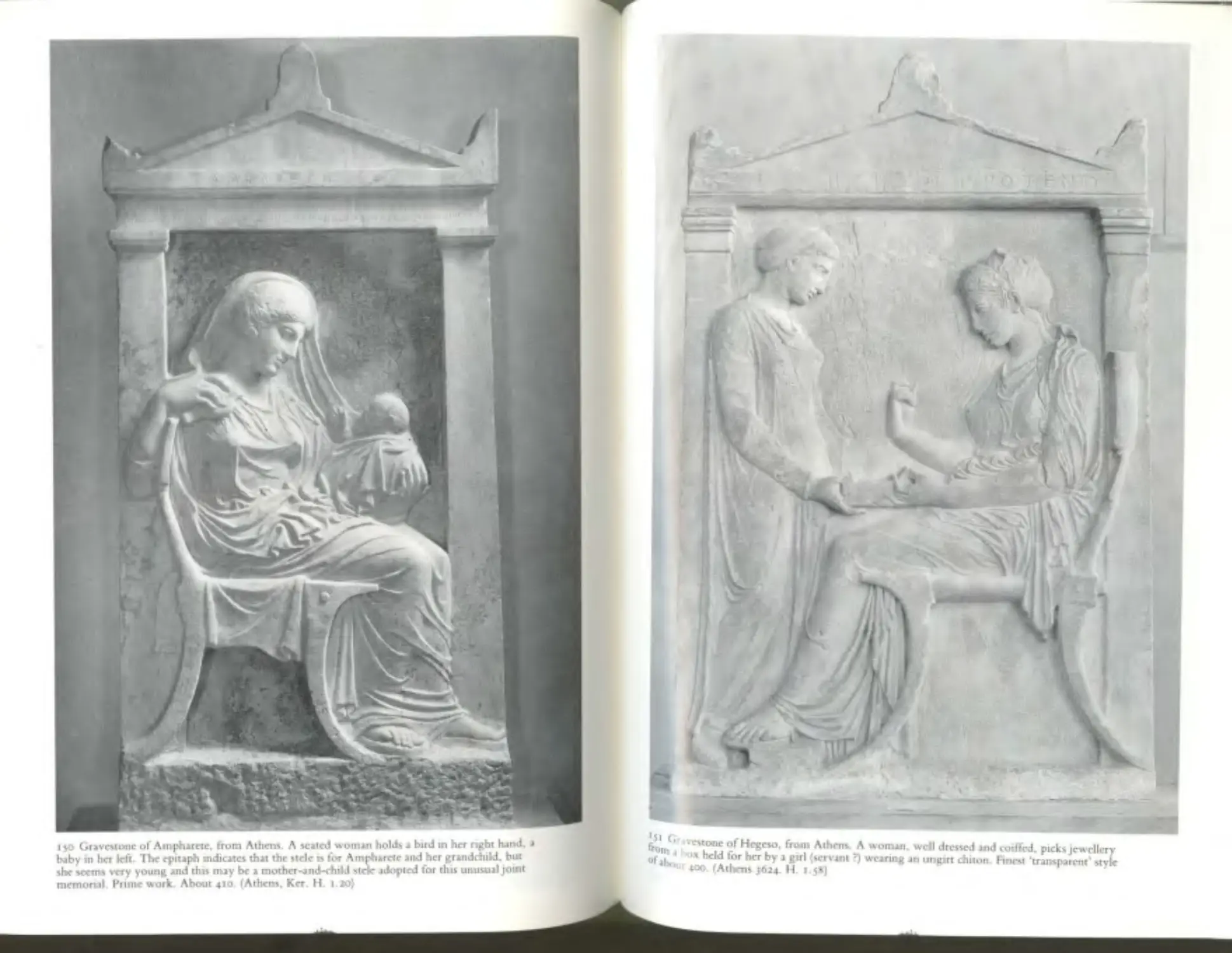

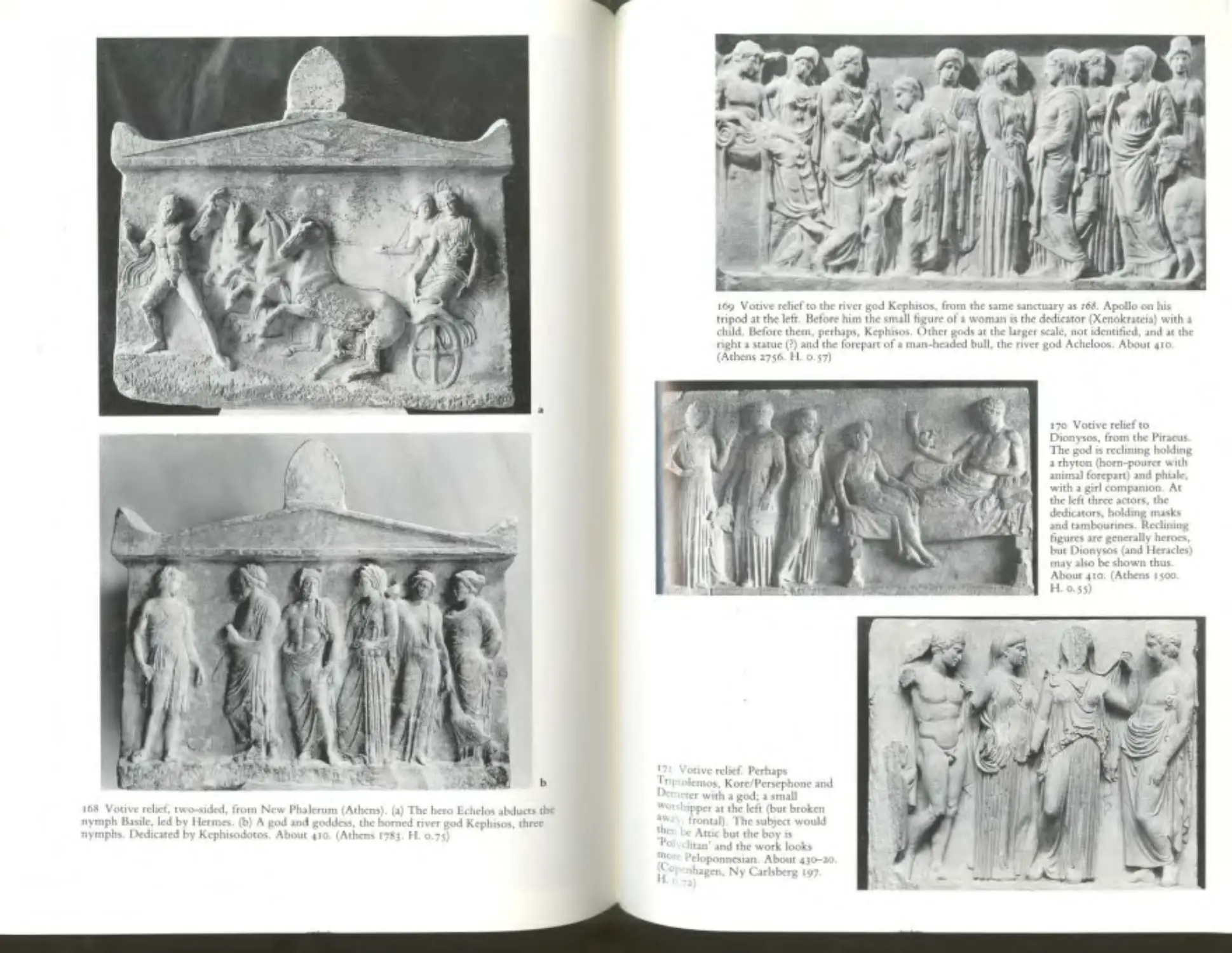

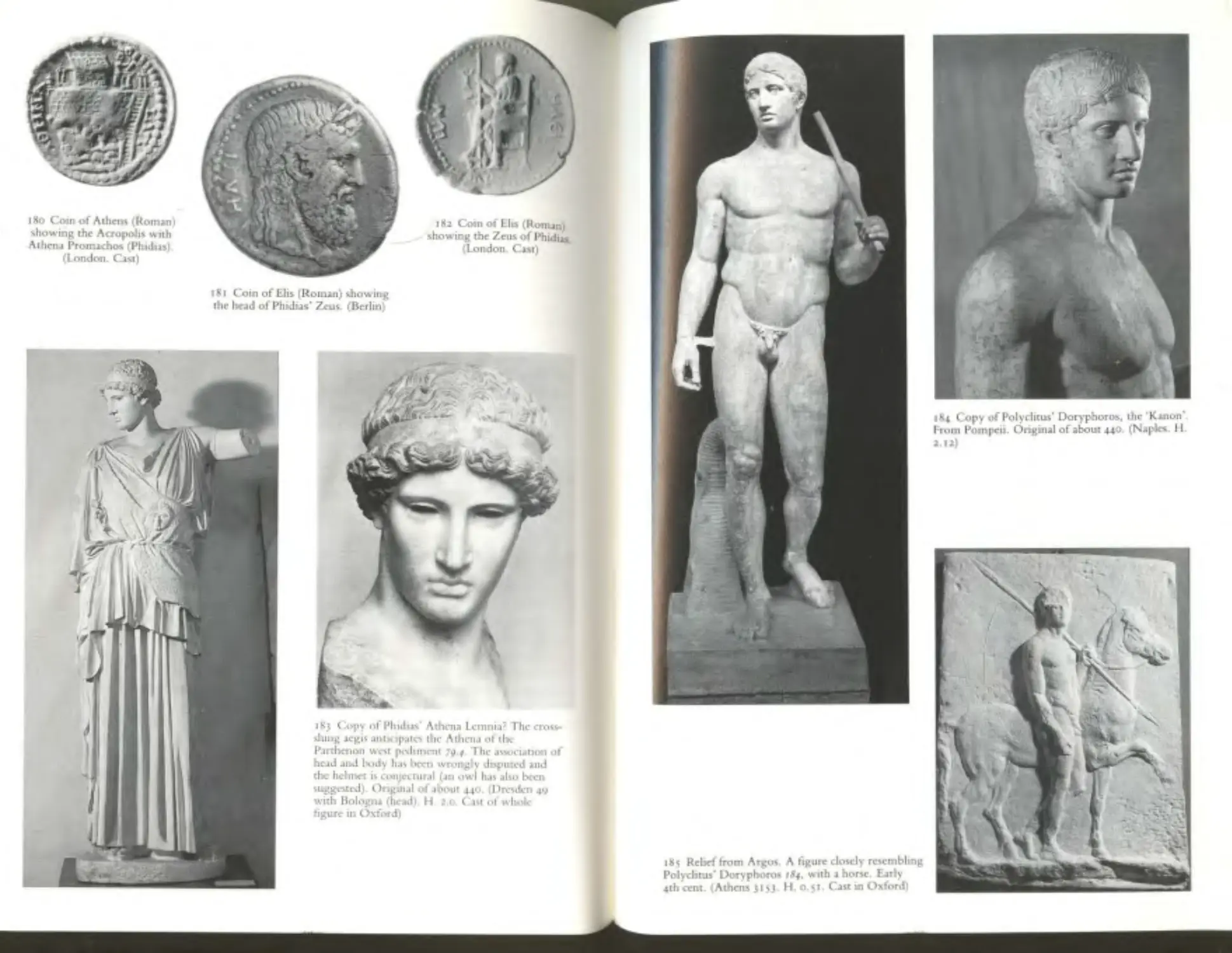

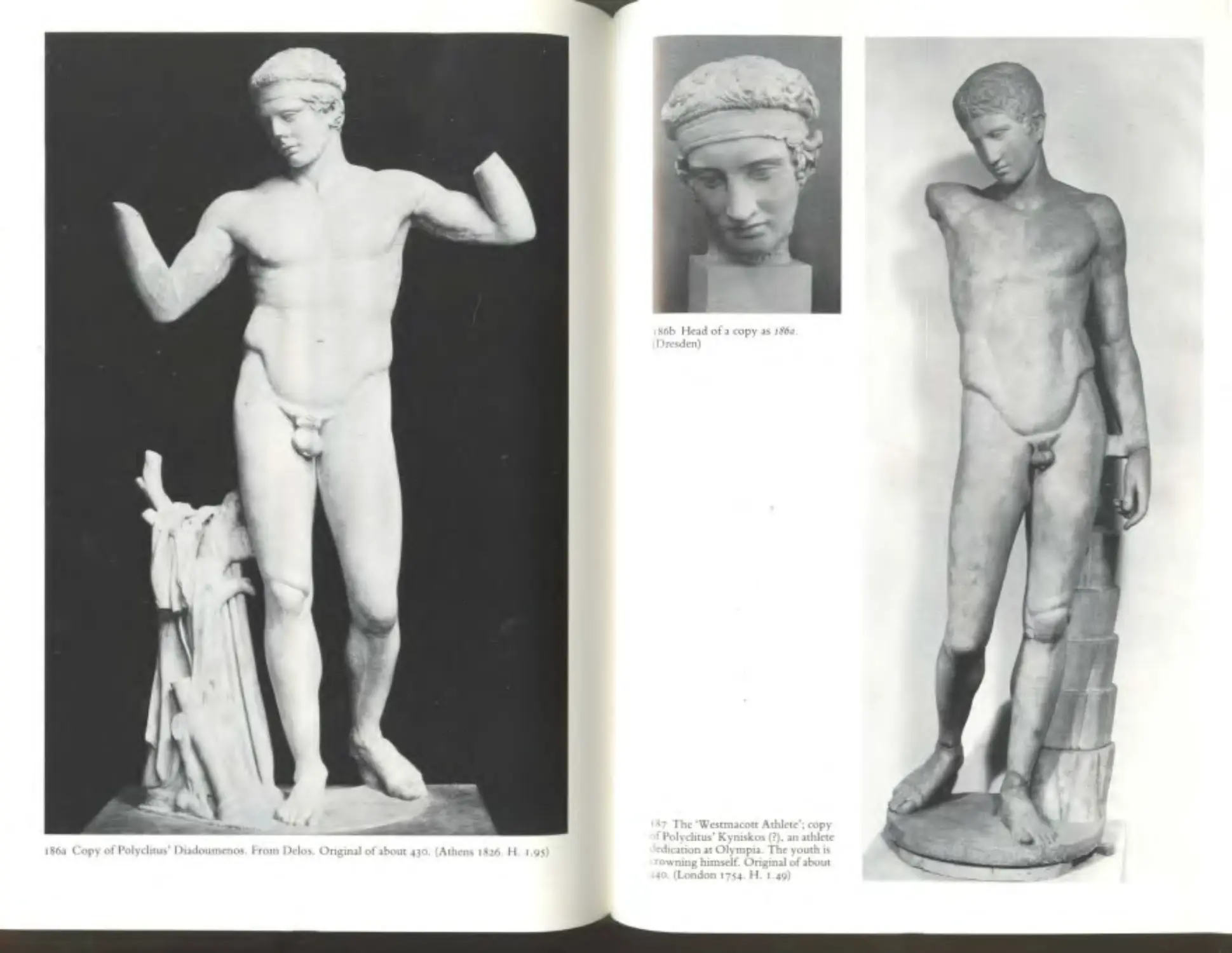

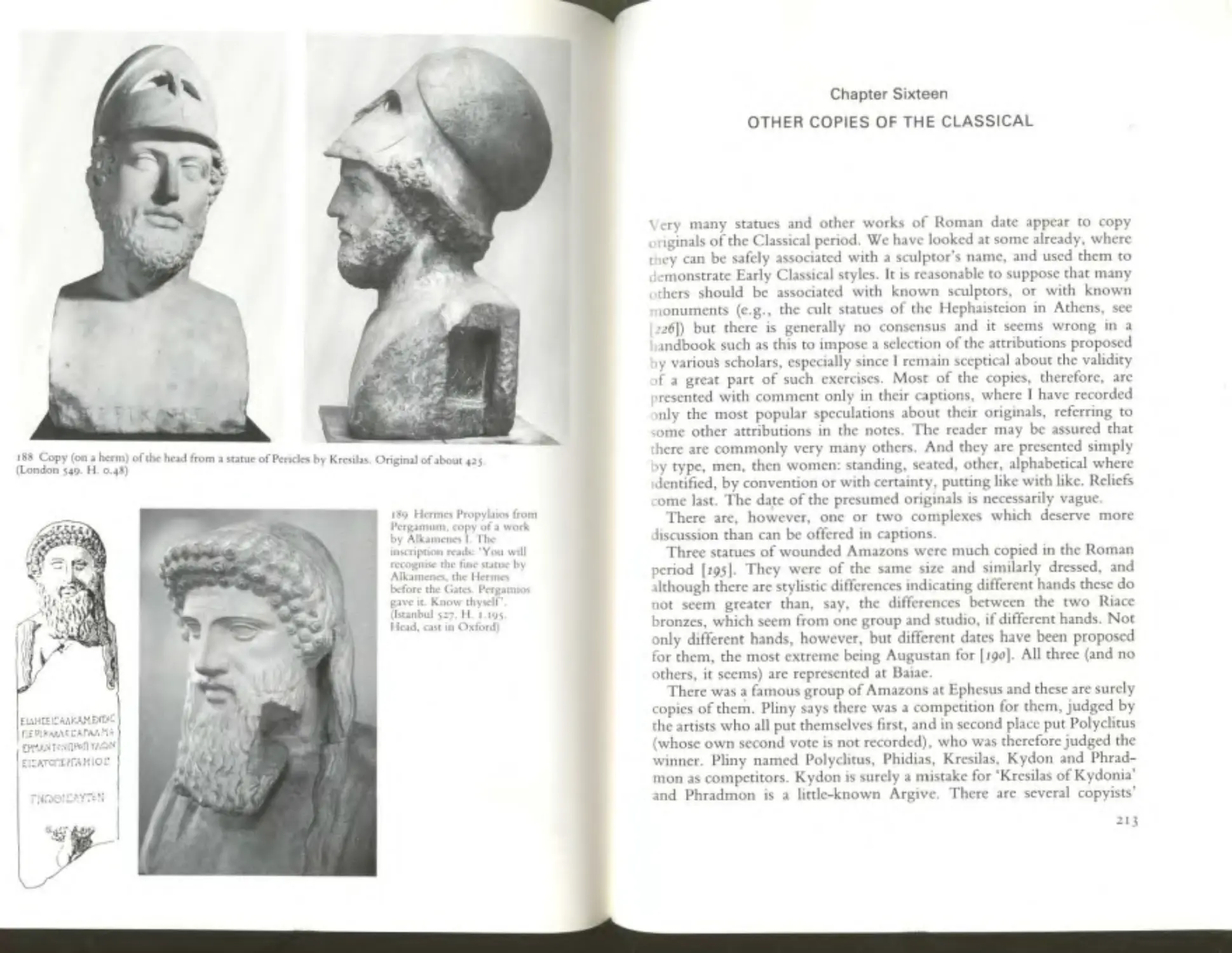

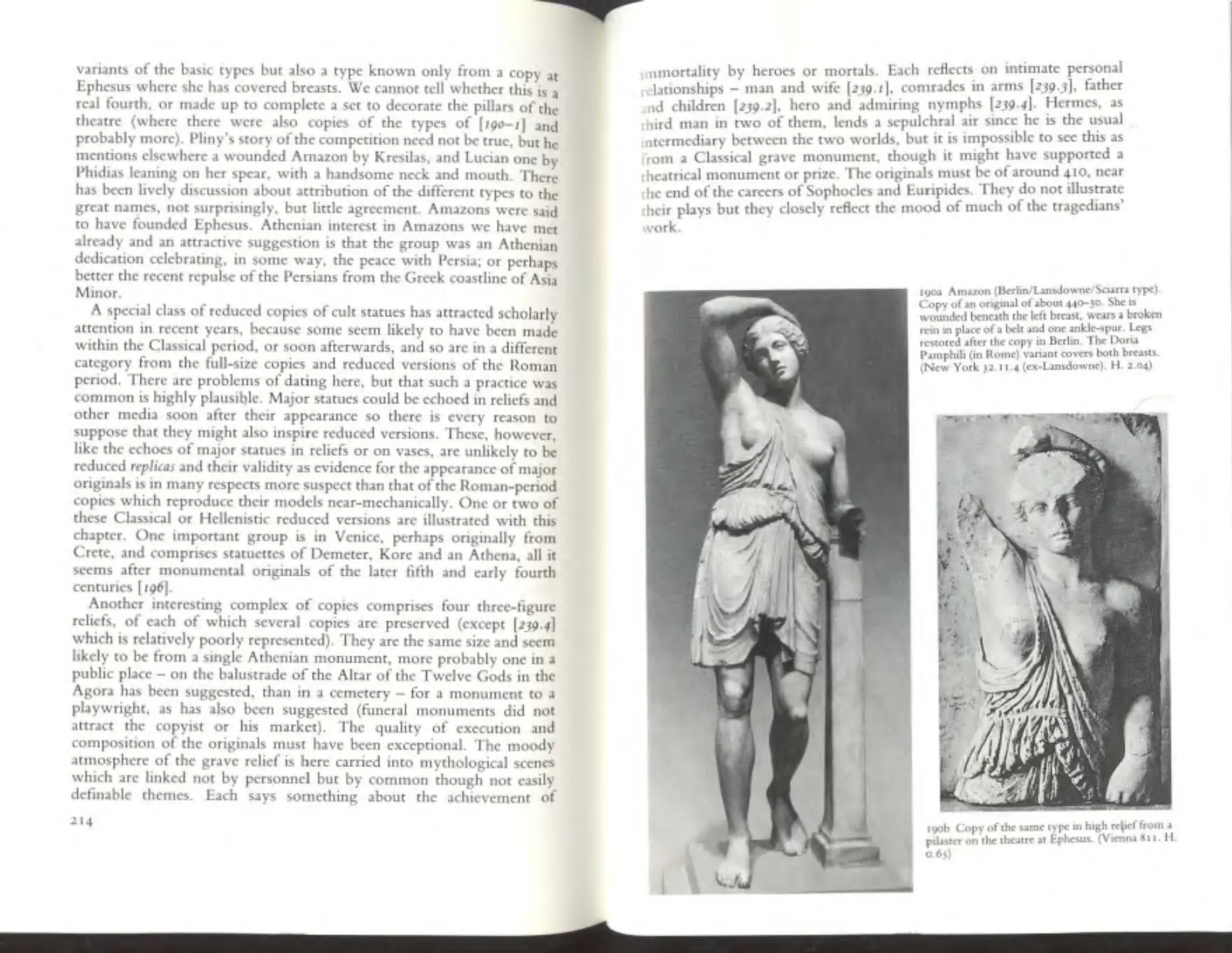

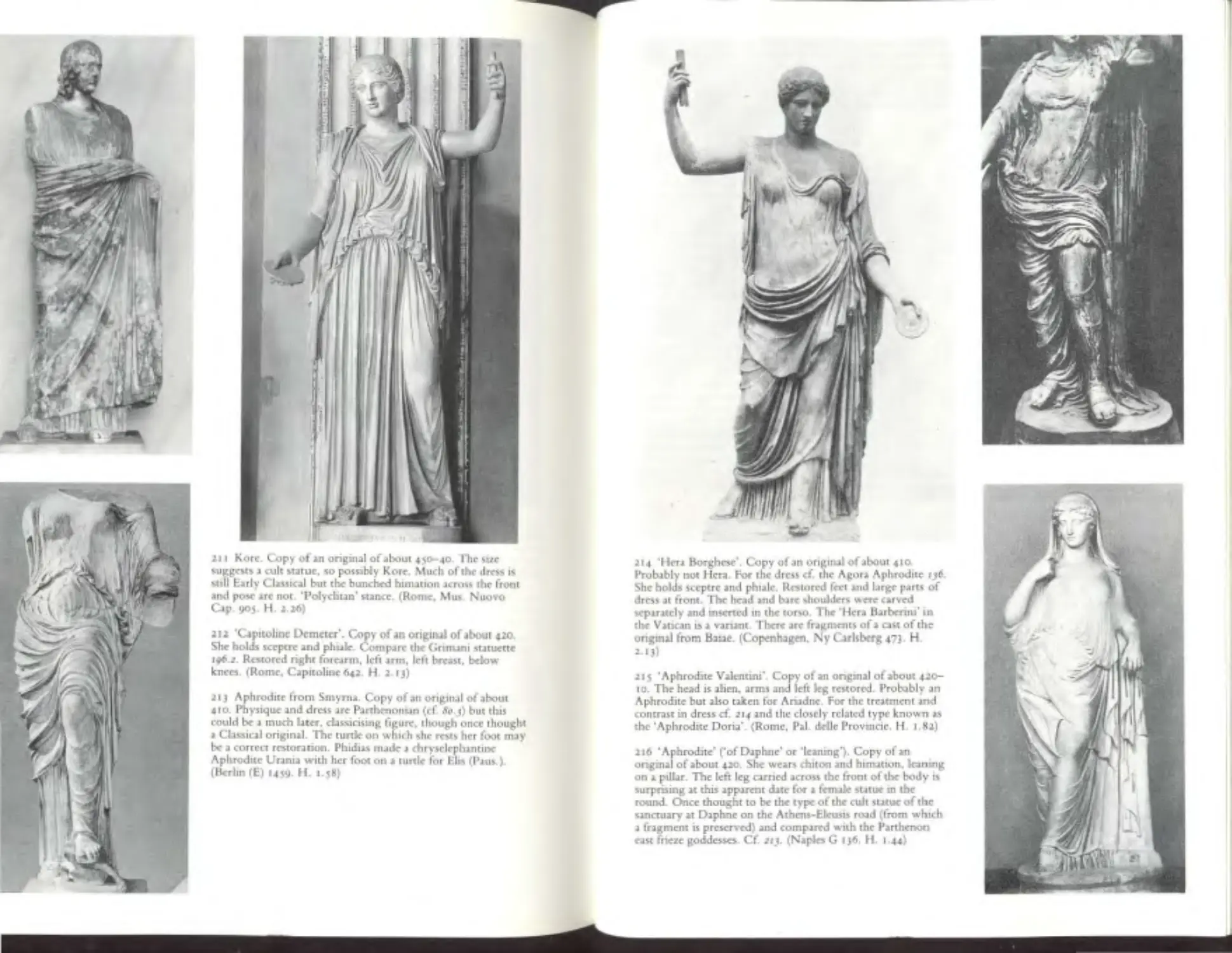

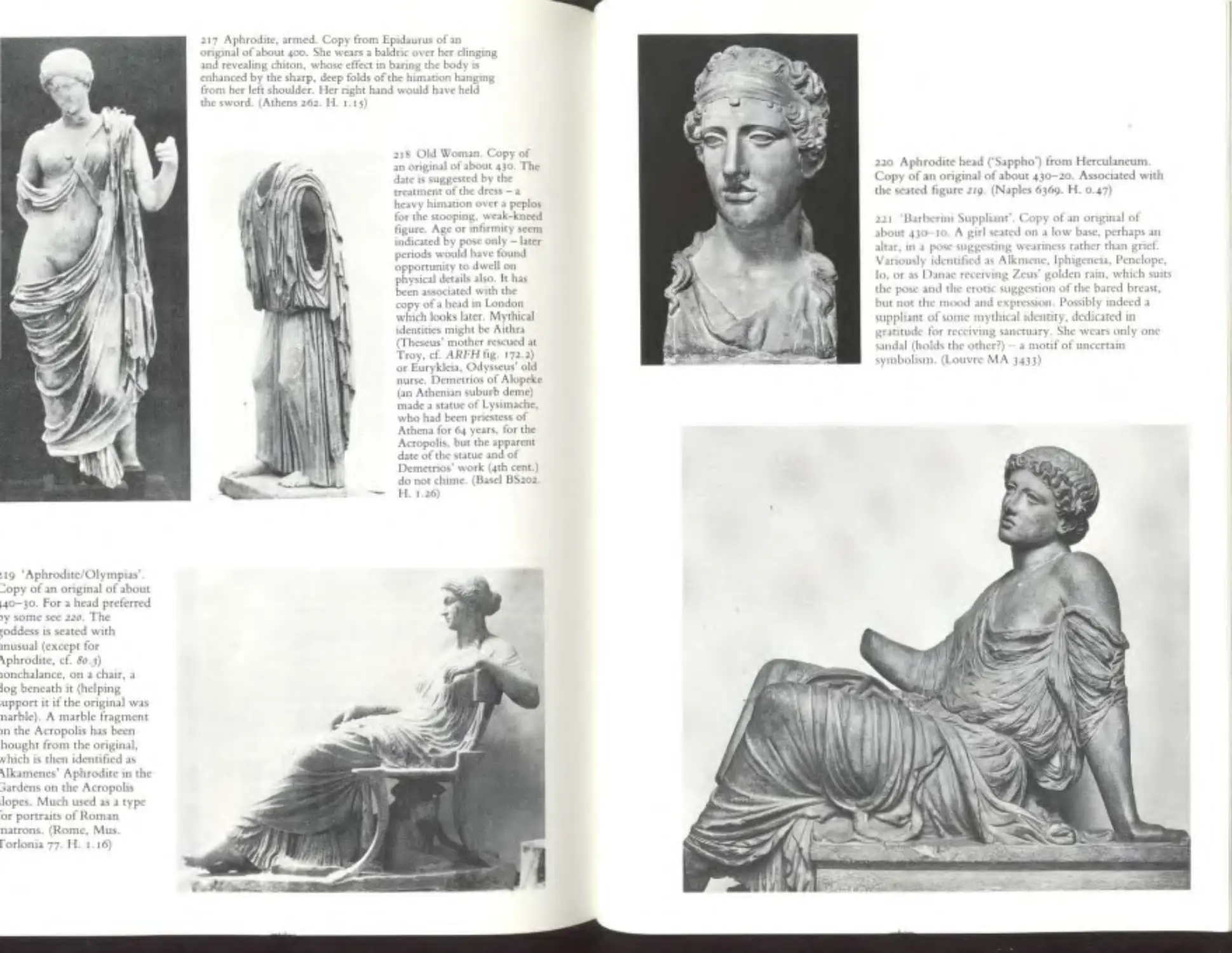

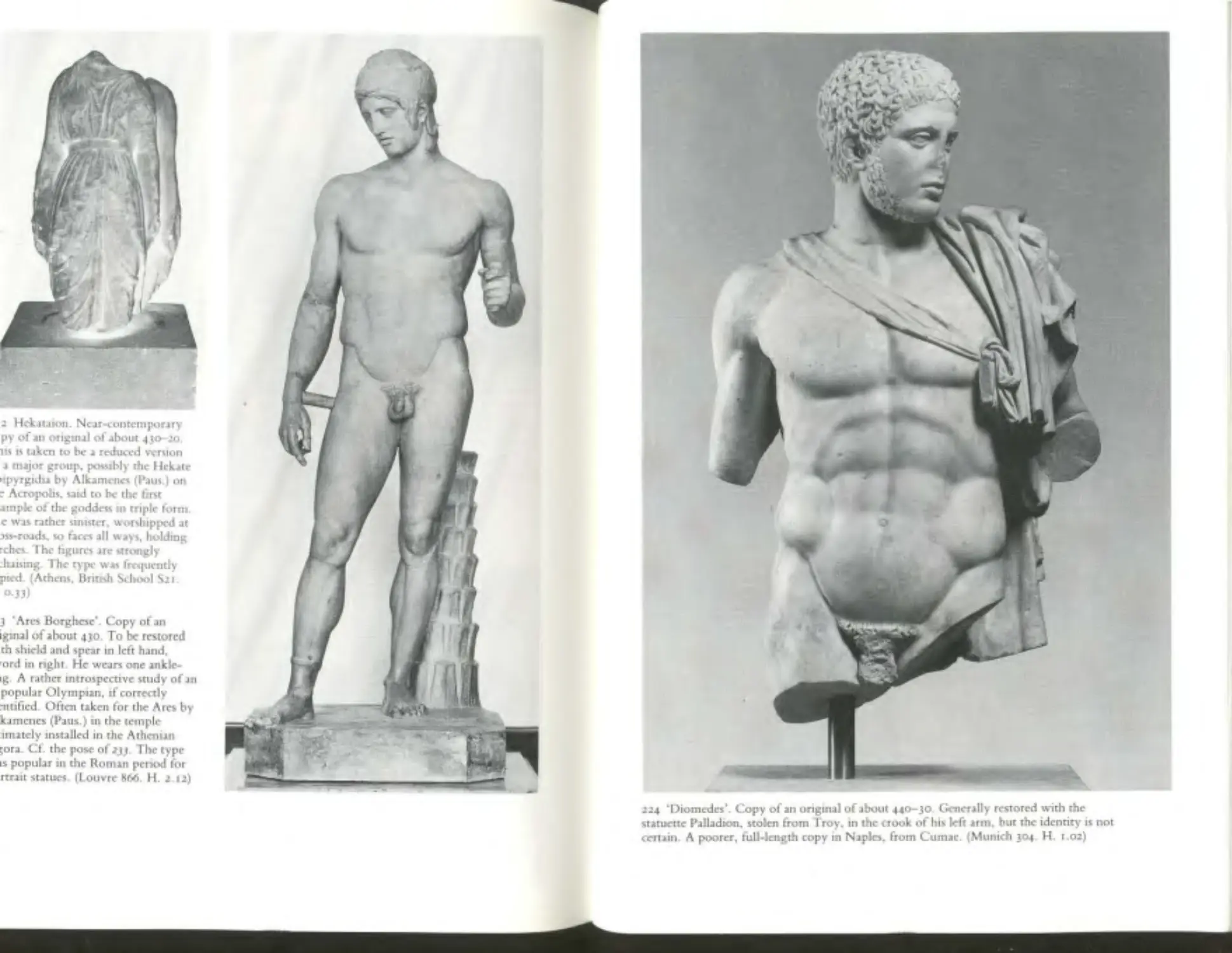

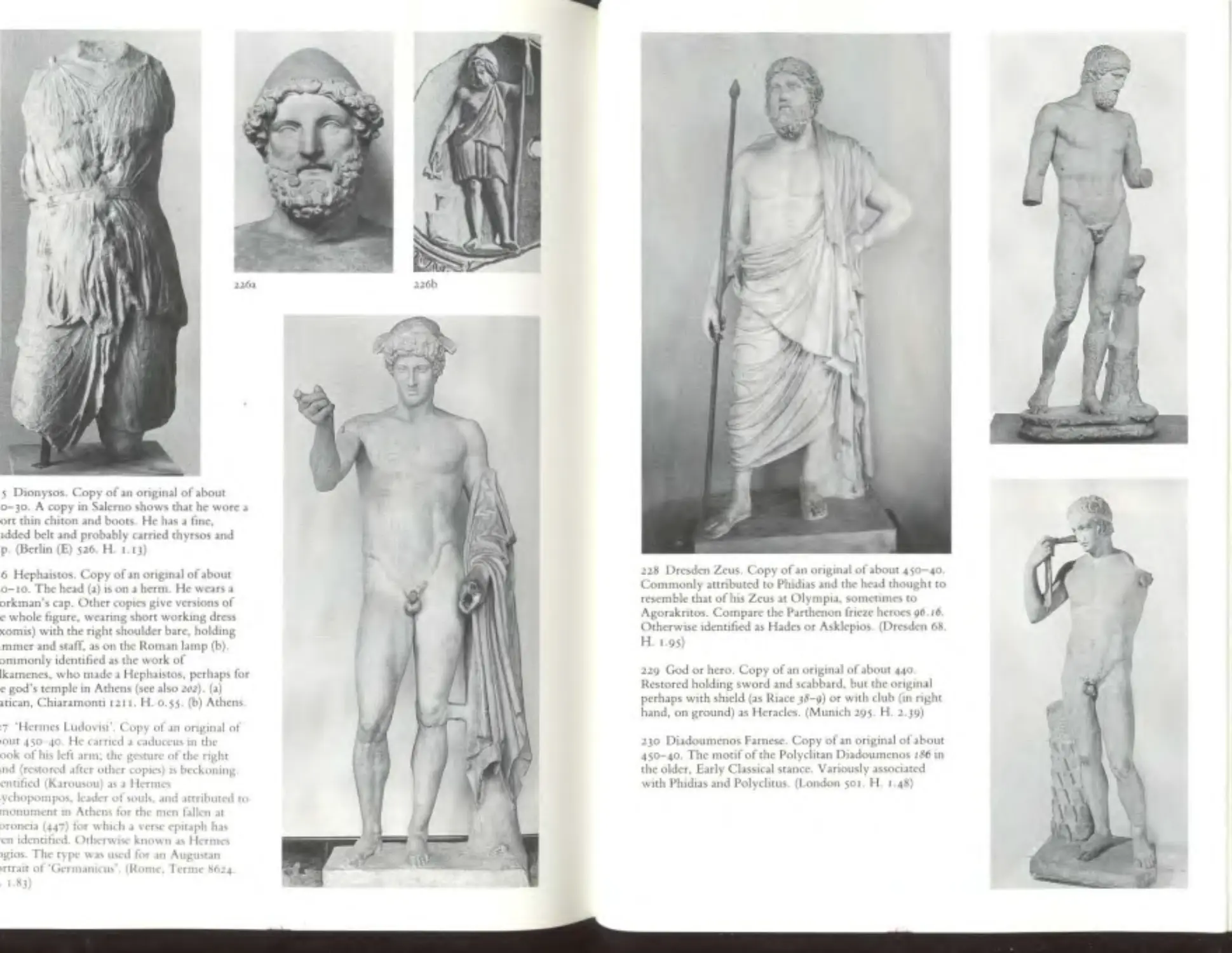

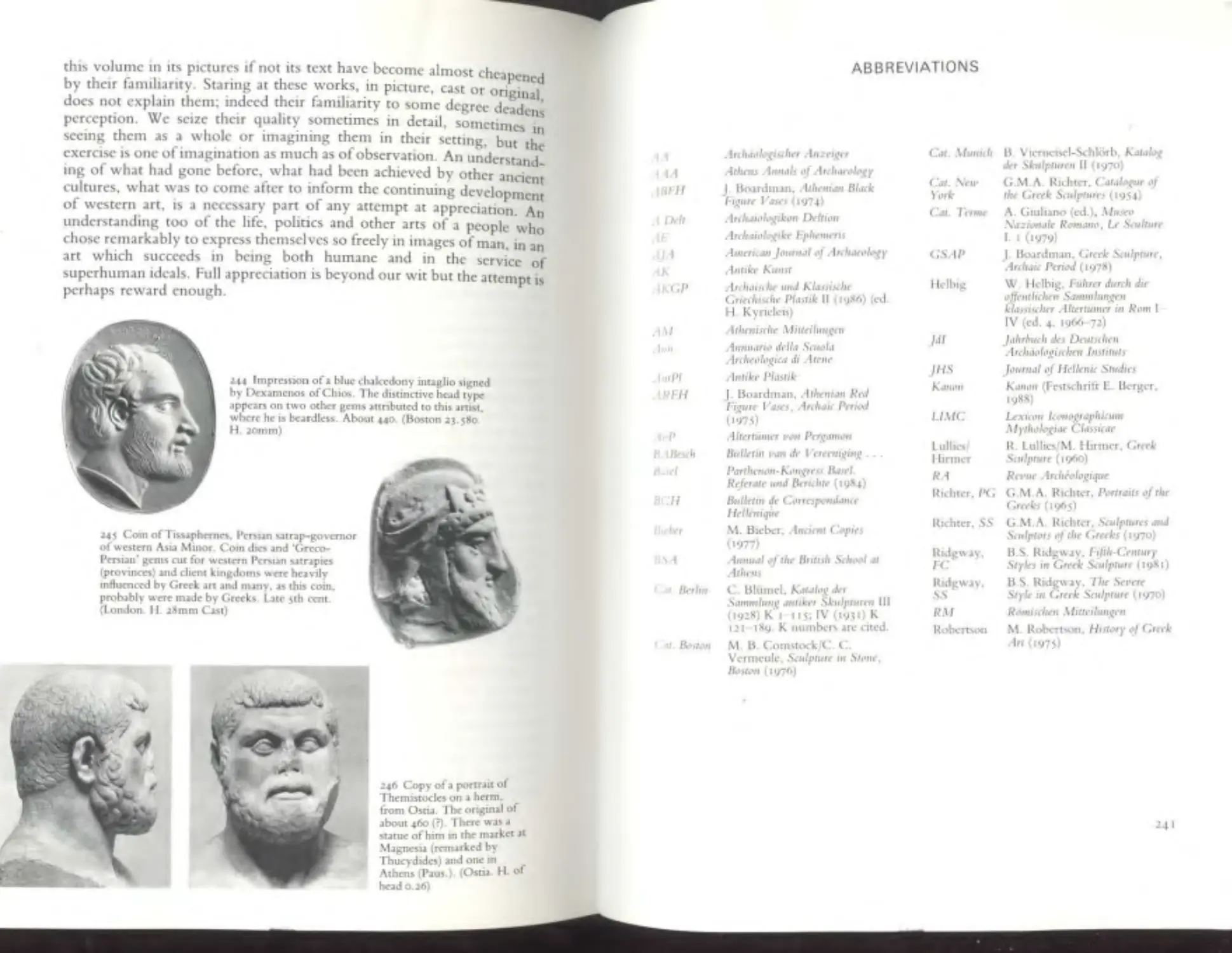

18 Olympia, Temple ofZcus. East Ped1ment

P~usanias thought the centre figure was a statur o f Zeus, but thl\ IS unhkdy - he IS an un\ccn

presence. The f1gure no doubt held a thunder bolt (or sceptre) P;a us. uw young Pdop s (G) to

the nght, Omomaos (I) to the left ;md beside Pdops has bnde-to-bc H 1ppodamia, beside

Omomaos h1s w1fc Sterope. Unfort unately tt is not cll:'n whether he means Zeus' or the

v1ewcr's. At lc;an we can 1dcnufy Pclops as the youn ger man . Sccrope tS likely tO be the figure

m pens1ve mood (F), lllppodami a the one m aking a b ride-like gesture pluckmg at h er drcs'l (K)

an d with beh ed peplos. Some scholars exchange the identuics ofF and K, a nd it must admitted

that, in the scauer offragments. F was found nc.arcr G and I nearer K Arguments from

reconst ruc uons ofwhole figures have also recently supported th1s schem e. So the placmg of

FG IK remams uncerum, ;md t he tdcntity ofF and K. K has shagg1cr, r umpled locks. Omomaos

looks distressed. mouth part open. and Zeus mchncs h1s head (favouubl y?) to his nght. Paus

s.;aw Myrttlos ~fore Omomaos' horses but may havt betn m1slcd by the long chanoteer-likc

d ress (really a peplos) of the crouching g1rl 0. who may bt- Steropc's m.aid, but she and other

crouchmg figures- the naked youth .and boy, 8 and E (bur not the horse-mmder C)- arc

vanously placed m the pedtment by schol.ars. The boy piJymg tdly wnh h1s toes (E) has been

hkcned to the hero Arkas as he 1s shown on coms. The chariou were euher added m bronze or

not shown :1t all. T he o ld man on Pelops' side (L) IS alert (he may be Amyth:~on); the one on

Omomaos' side (N) worrted (he may be t he sur Ja mos). The reclmmg men t o left and nght arc

idenufied by Paus. as Alphc10s and Kladeos, t he local nvers . H e was used to rech nmg nver

gods of later date. but may be correct here. Most oflus tdenllficau ons sound like roughly

p lausible g uesswork, prob ably no be tter than ours. Late addit ions m b ronze were a corselet and

extra helmet for Pelops

N

E

p

AB

CDEFGHIK

LMNOPQ

RS

TU

V

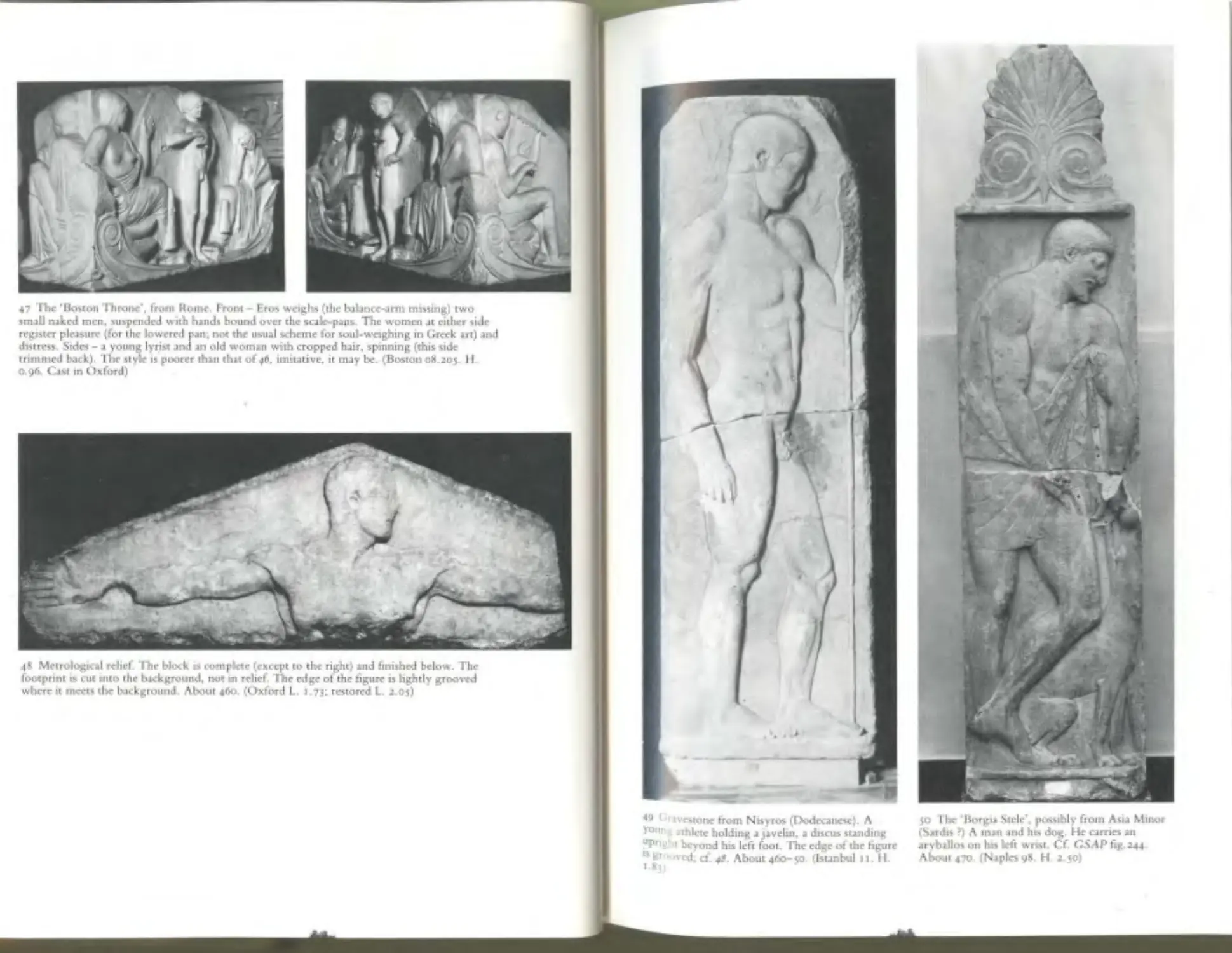

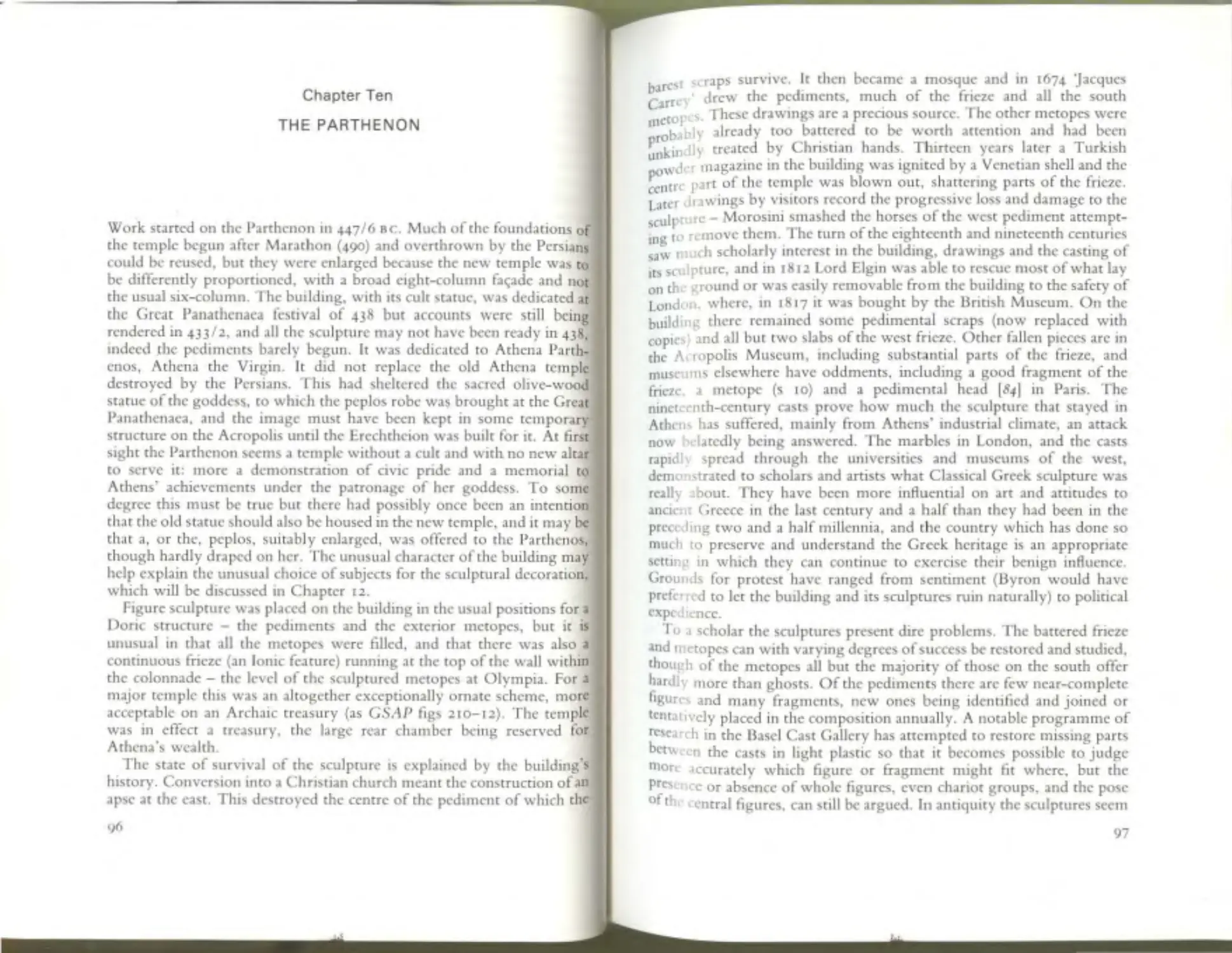

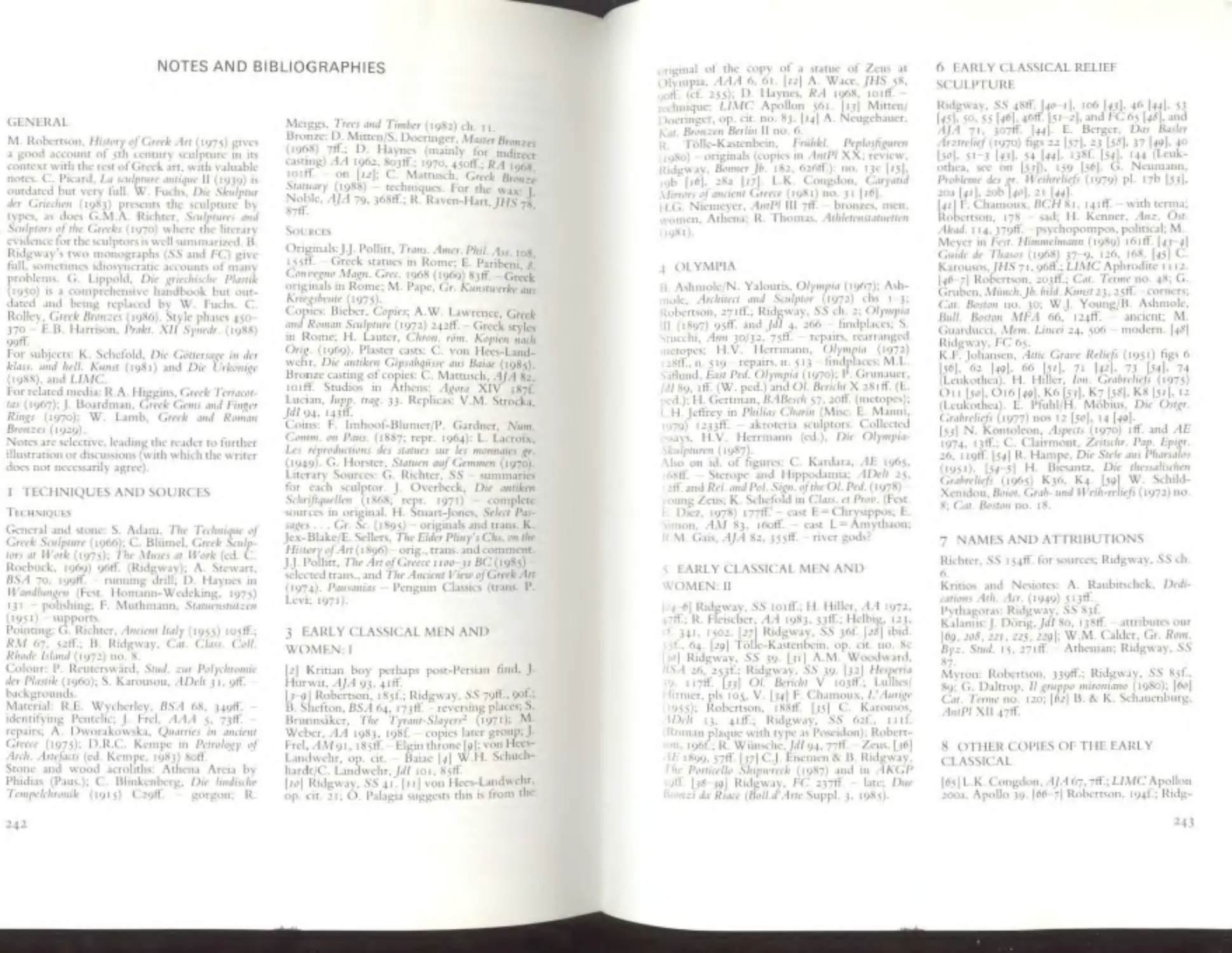

19 Olympia, T emp le ofZeus. West Pediment

The c~n trc fig ure m ust be Apollo and scraps are preser ved ofthe bow he probably held m hts

lowered h and. Paus. t hought h e w as Peinthoos and a scholar has recently arg ued for a 'youn g

Zeus'. Paus. uw Theseus beside him w tth an axe, certainly M , smce the axe, p ose an d dress

shpp mg down the leg~ arc seen for Theseus on .sth cent. vases. Pemthoos must be K (Paus.

thought hun Kameu~. a less app ropriate figure in 1hc wcddmg brawl) in tyrantucide pose (cf. J)

and the group beside htm h1s bride De1dameu, and the cenuur Eurytion. Some transpose the

groups HIK and MNO, buc thts ts awkward A ~nd V are old women, the former a

replacement m Pencchc marble for a danuged or deSlroycd ongmal. but m appropnatc style; V

h1s also a new .urn. Band U arc angutshcd old women in Pcntehc marble. 1dded probably in

the 1St cent IK, C\lt 111 a less congruent style Uter addnions in bronze were a wreath for

Euryt1011 (I) and the sword m S.

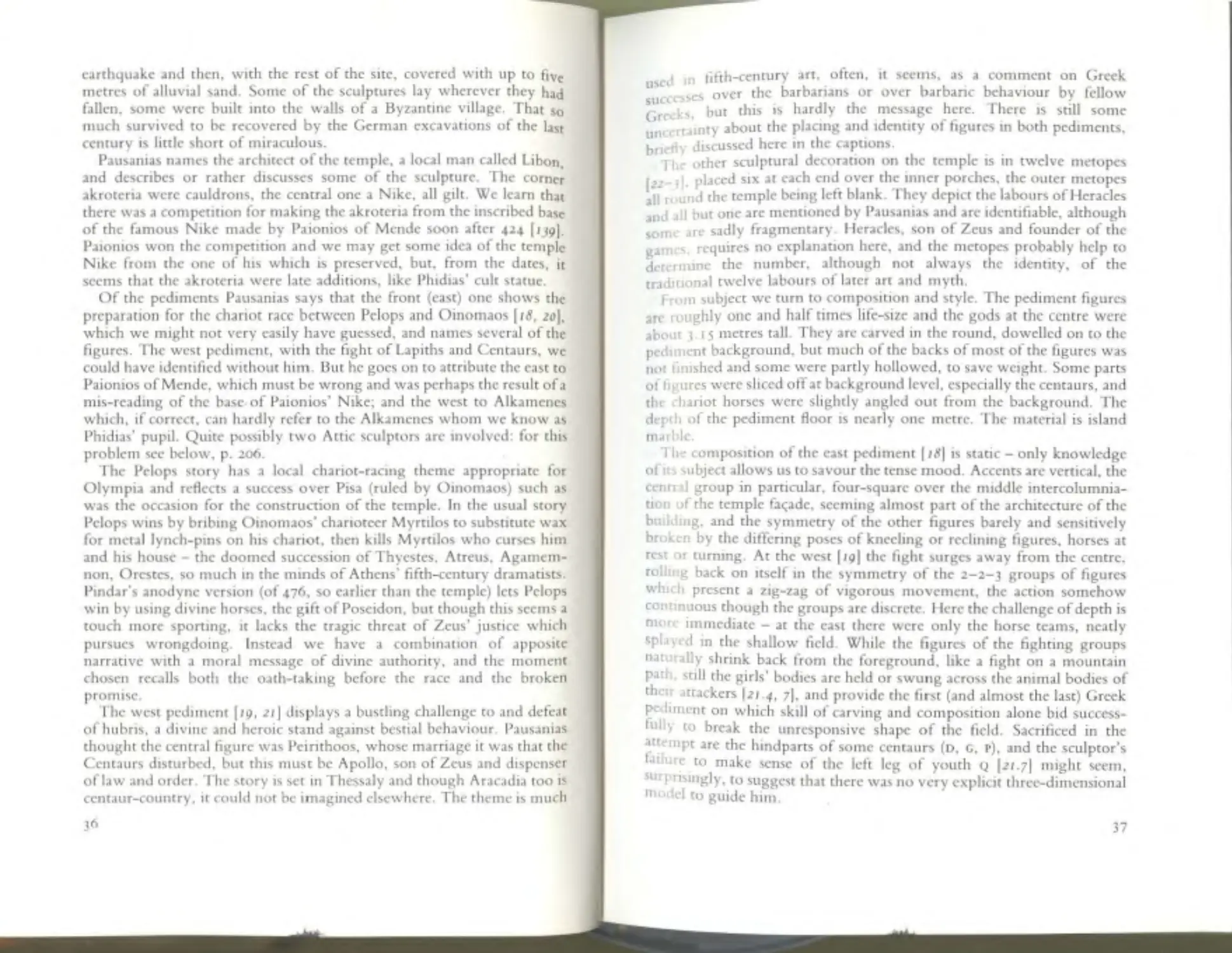

earthquake and then, With the r est of the si t e, covered with up eo five

metres of alluv1al sand. Some of the sculptures lay w h erever they had

fa ll en , some were built into the walls of a Byzantmc v11lagc. That so

much su r vived to be recovered by the German excavations of the last

centur y IS little short of miraculous.

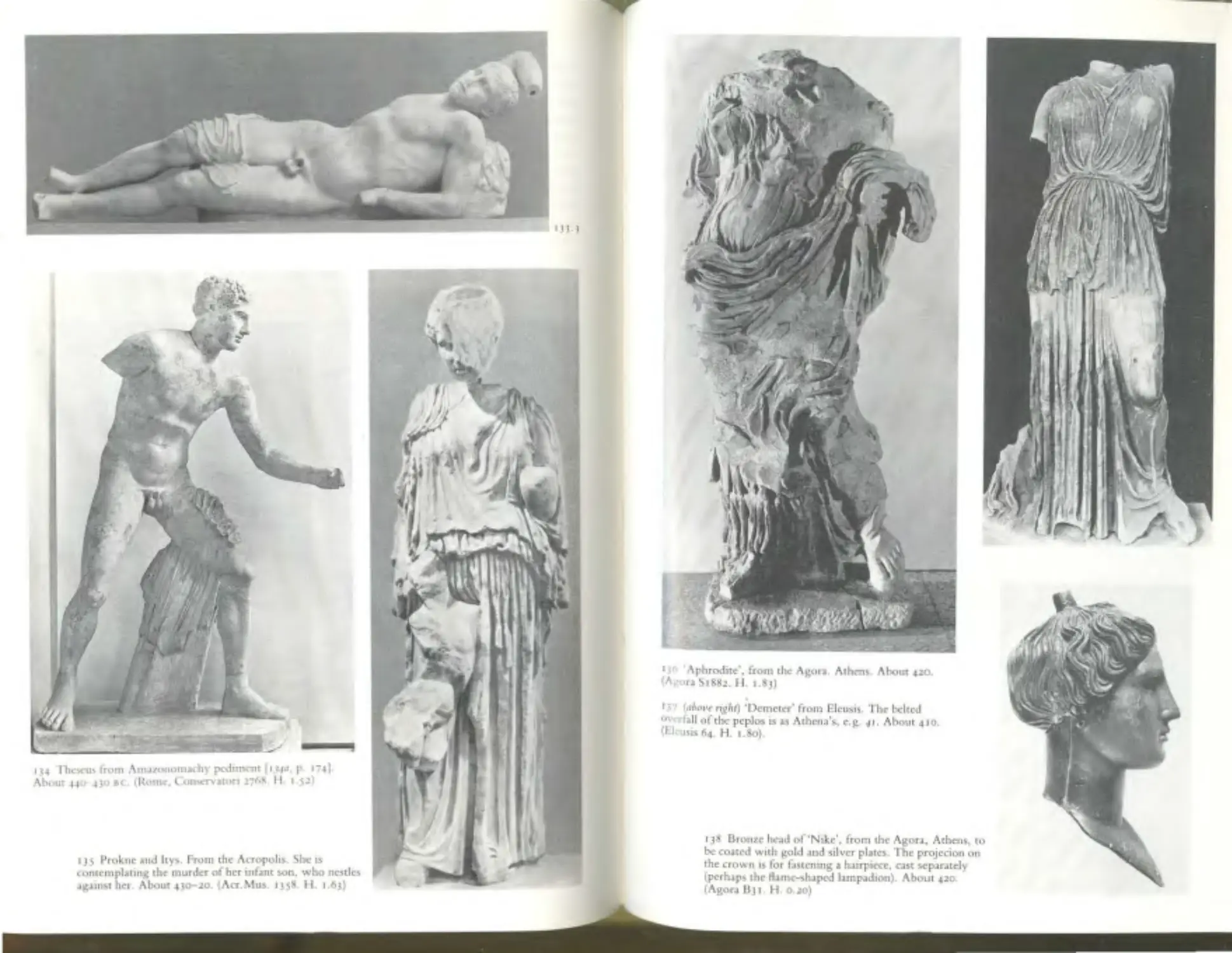

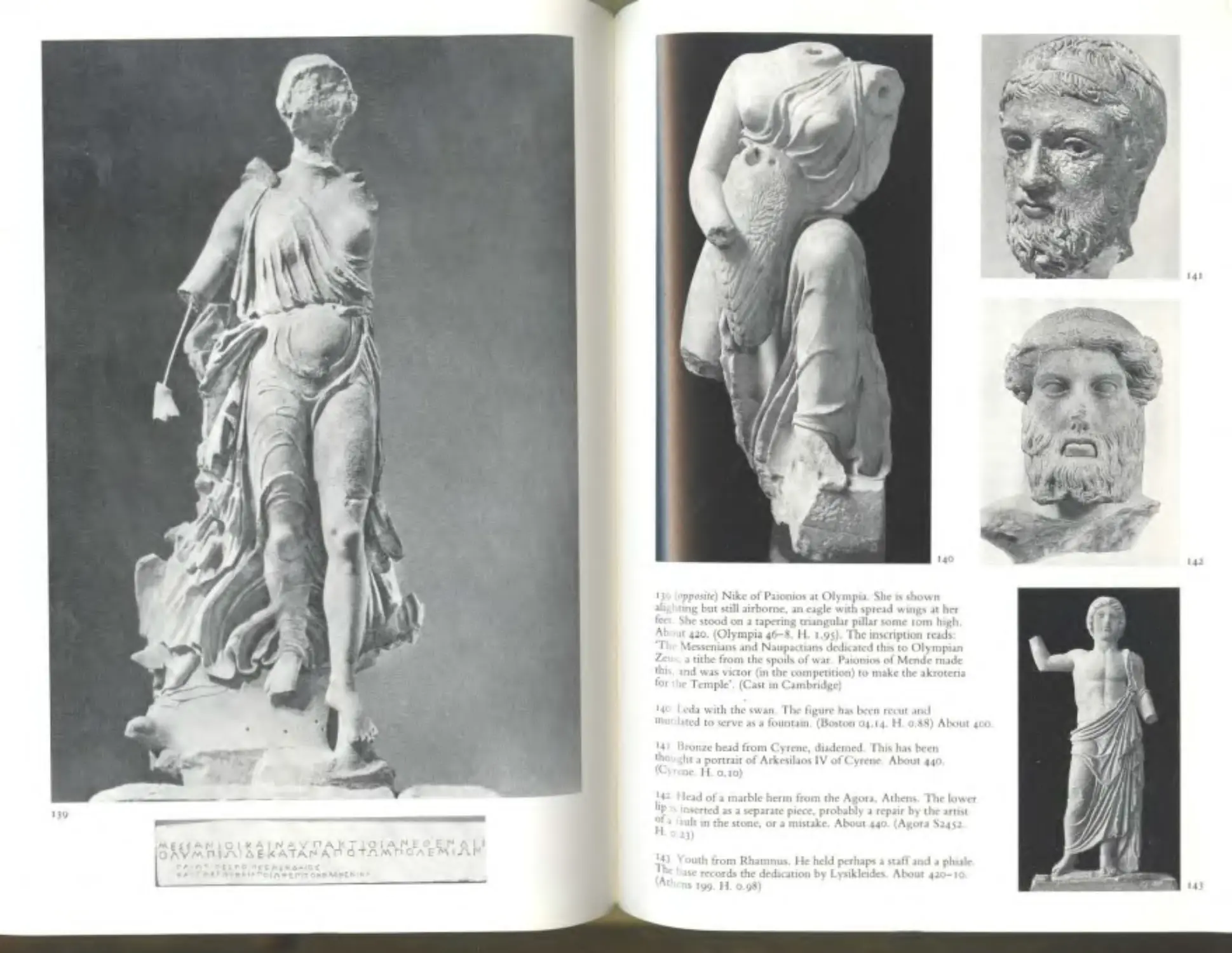

Pausamas names the archuect of the temple, a local man called Libon,

and des cribes or rather d1scusses some of the sculpture. The corner

akroteria were cauldrons, the central one a Nike, all gilt. We learn chat

there was a competitiOn for making the ak roceria from the mscnbed base

of the famous N 1kc made by Paionios of Mende soon after 424 (139 ].

Paionios won the compemion and we may gee some idea of the temple

N1kc from the one of his which is presaved, but, from the dates, tt

seems that the akroteria wer e late additions, like Phidias' cult statue.

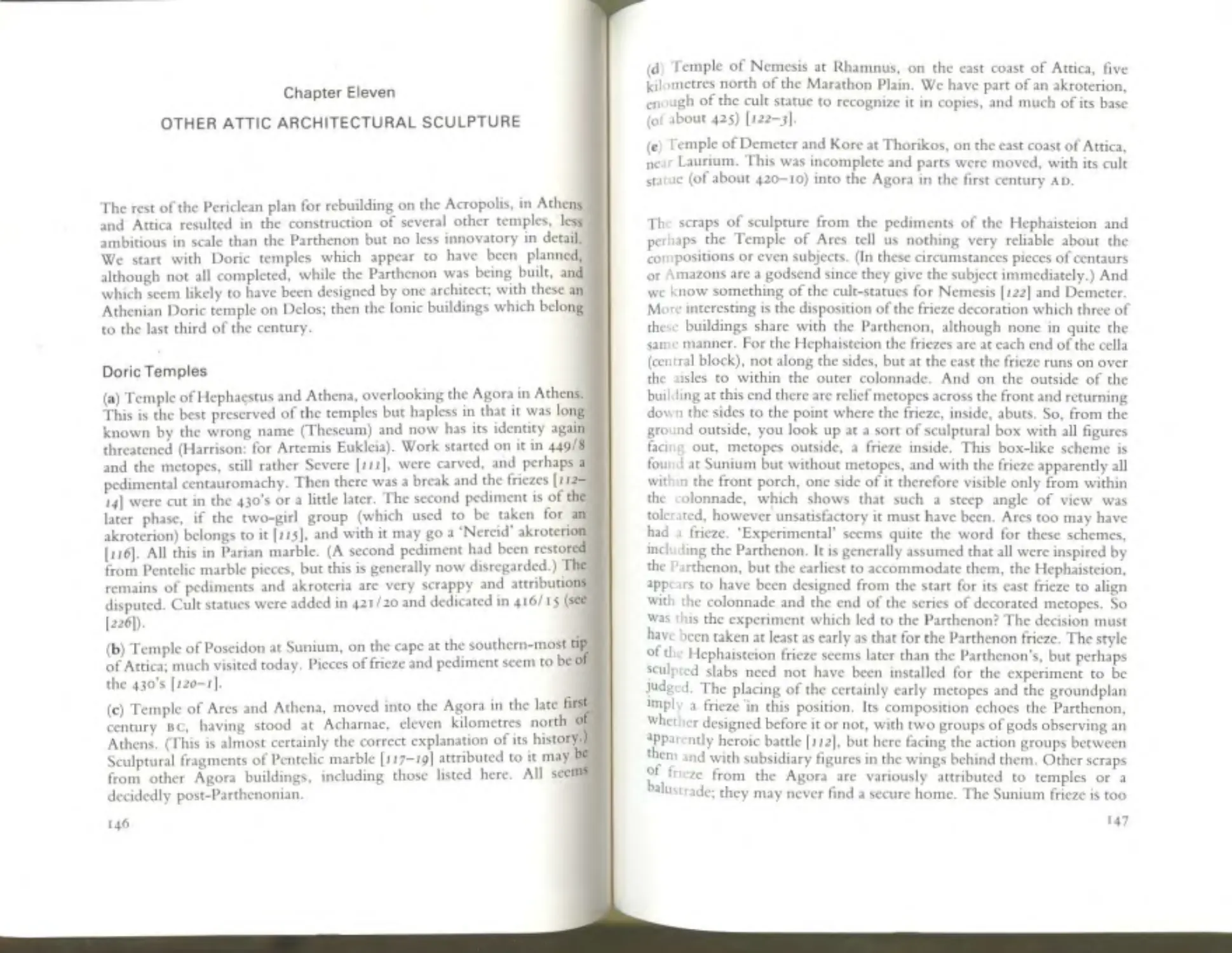

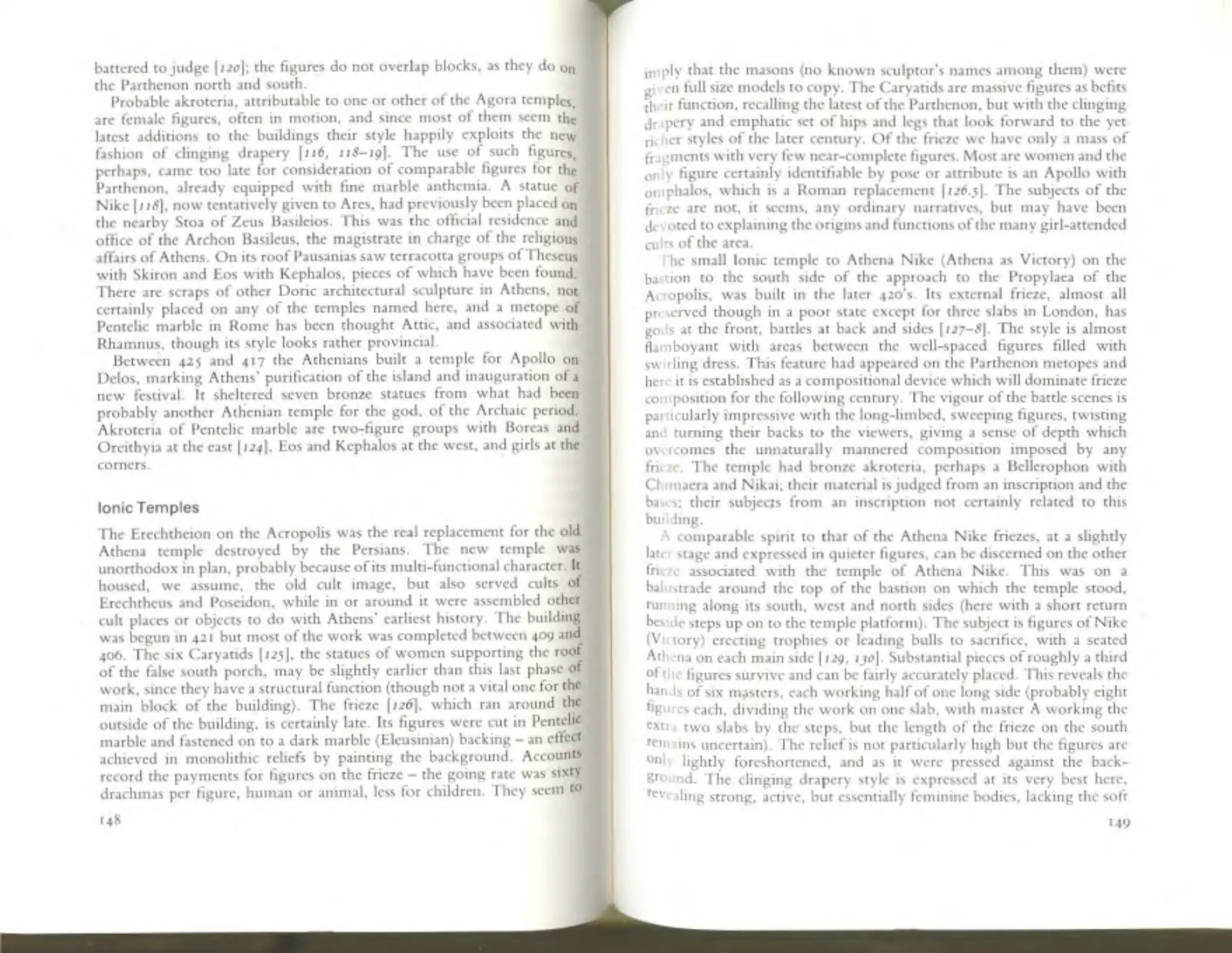

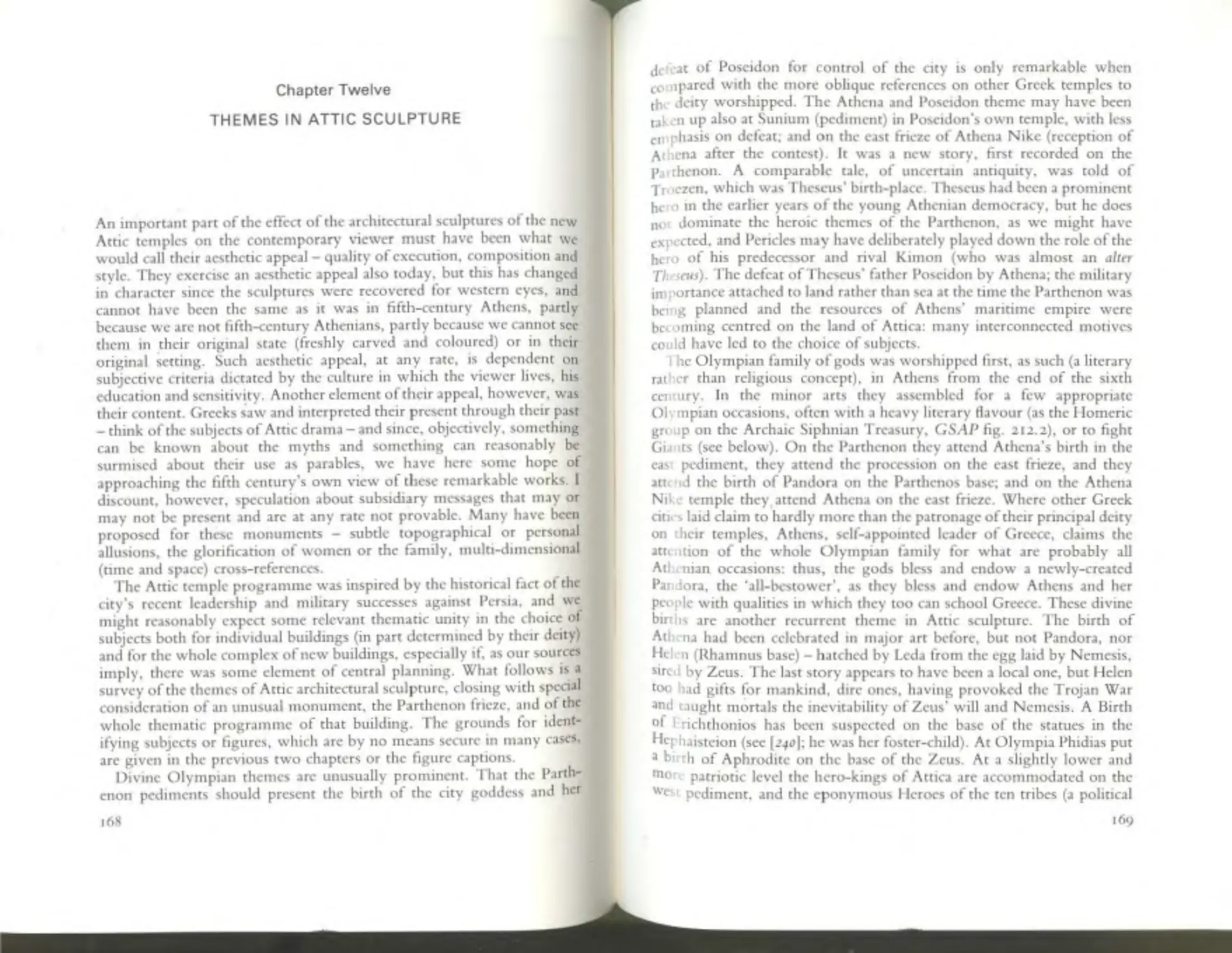

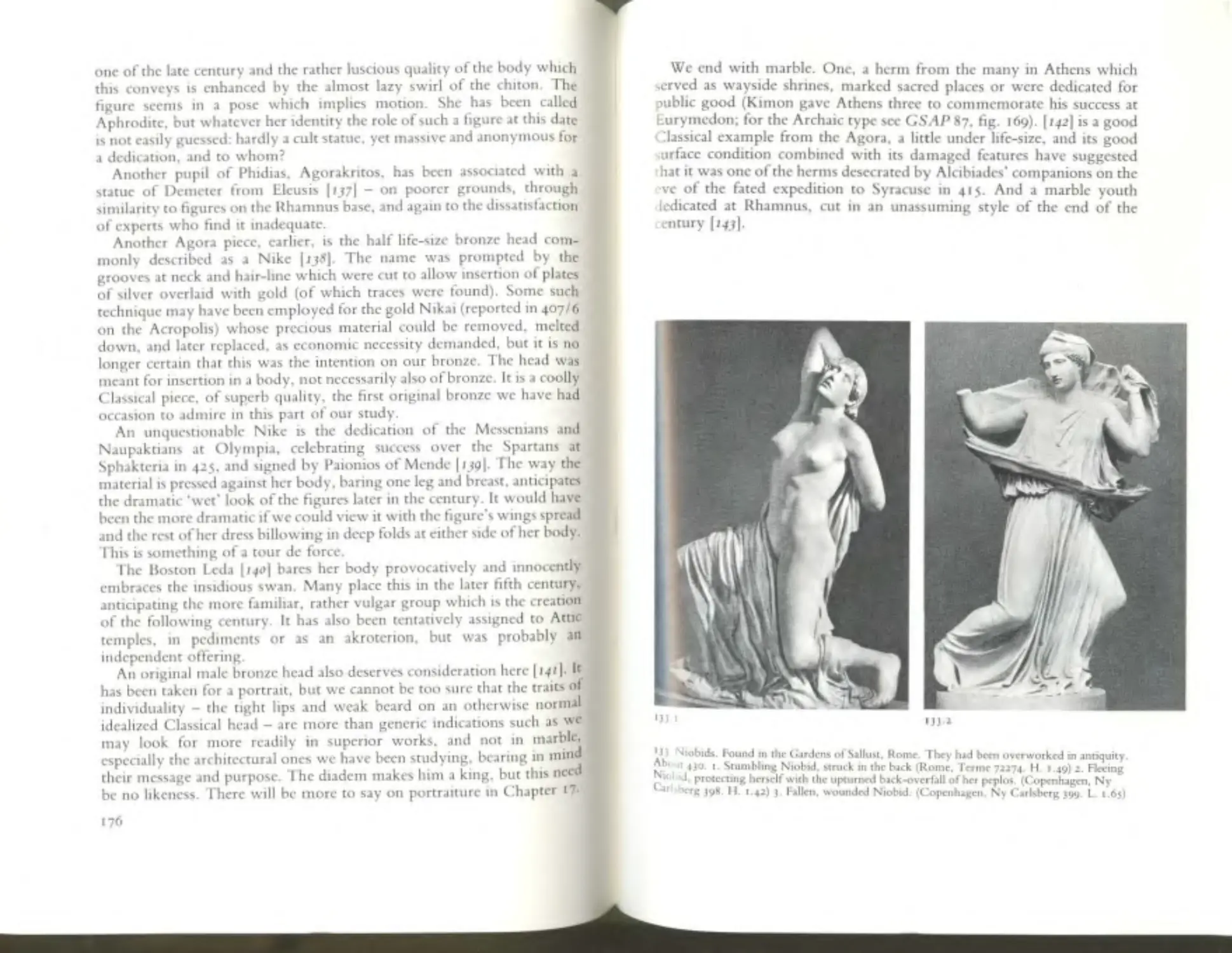

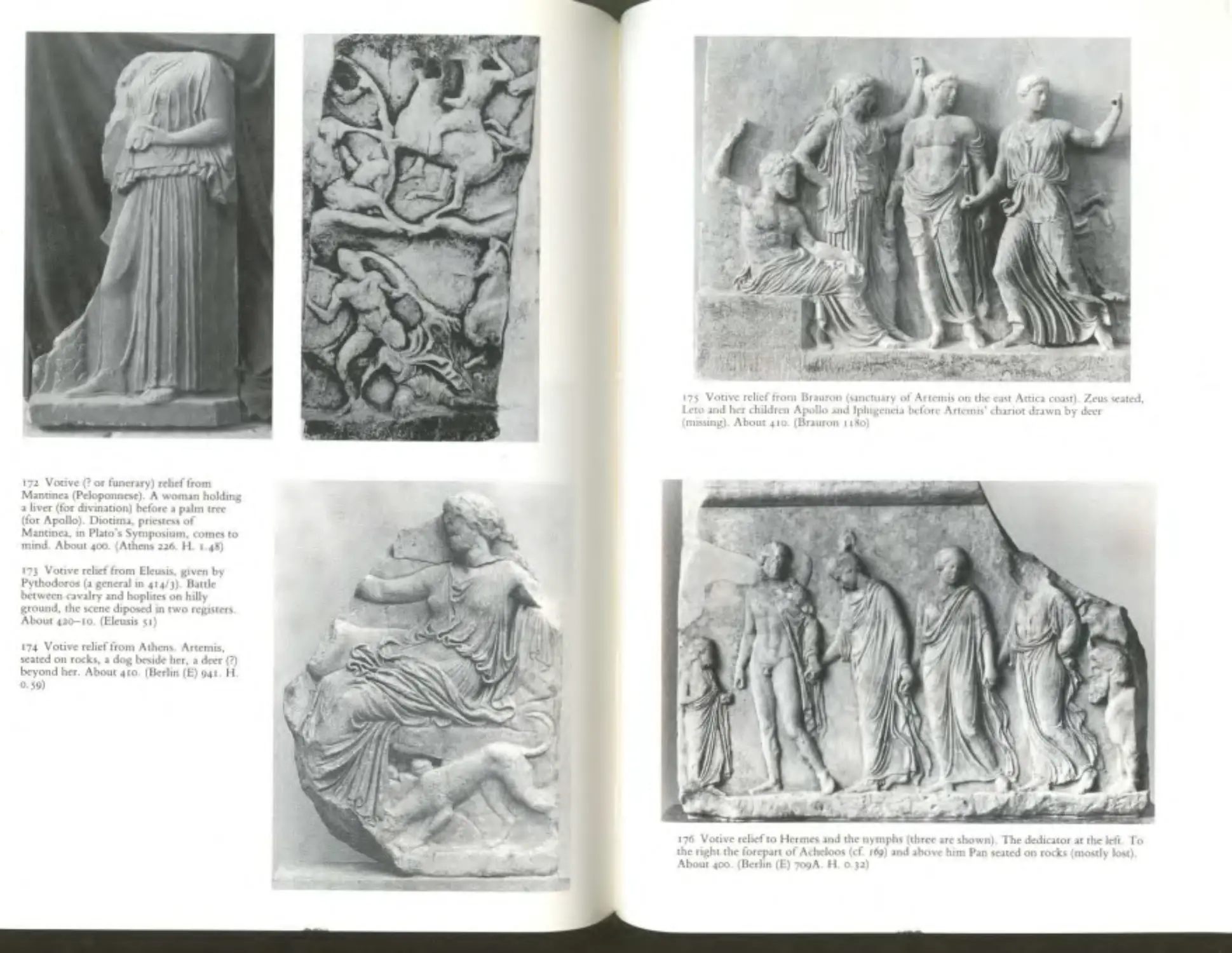

Of che pediments Pausanias says that the from (ease) one sh ows the

prepara tion for th e chariot race between Pelops and Oinomaos [18, zo j,

which we might not ve ry eas ily have guessed, and names several of the

figures. The west ped iment, with the fi ght of Lapiths and Centa urs, we

could have identified without him. But he goes on to attribute the cast to

Paionios of Mende, which muse be wrong and was perhaps the r esu lt of a

mis-reading of the base of Paionios' Nike; and the west eo Alkamenes

which, 1f co r rect, can hardly refer t o the Alkamcnes whom we know as

Phidia~· pupil. Quite poss1bly two Attic sculptors arc involved: for th1s

problem sec below, p. 206.

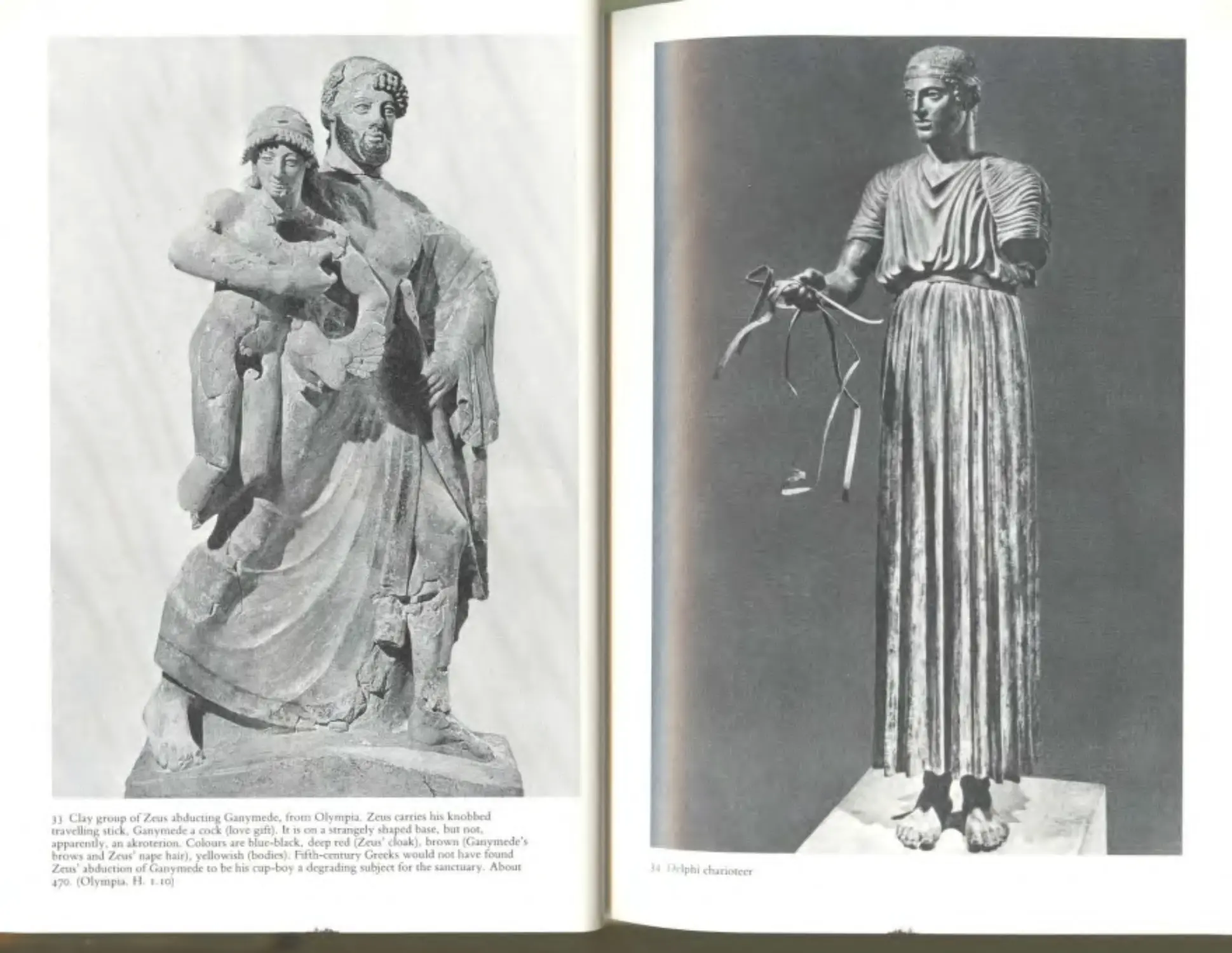

rhc Pelops story has a local chariot-racing theme appropnatc for

Olympia and reflects a success over Pisa (ruled by Oinomaos) such as

was the occasiOn for the construction of the temple. In the usual story

Pclops wms by bnbing Oinomaos' charioteer Myrtilos to substitute wax

for metal lynch-pms on h1s chariot, then kills Myrtilos who cu r ses hm1

and h1s house- the doomed succession of Thyestes. Atreus, Agamem-

non, Orest es, so much m the minds of Athens' fifth-century dramatises.

Pindar's anodyne vers1on (of 476, so earl ier than rhe temple) lets Pclops

win by using d1vine horses, the gift ofPoseidon, but though this seems a

touch more sportmg, 1t lacks the tragic threat of Zcus' justice which

pursues w r ongdom g. Instead we ha ve a combination of apposite

narrative With a moral message of divine authority, and the moment

chosen recalls both the oath-taking before the race and the b r oken

prom1se.

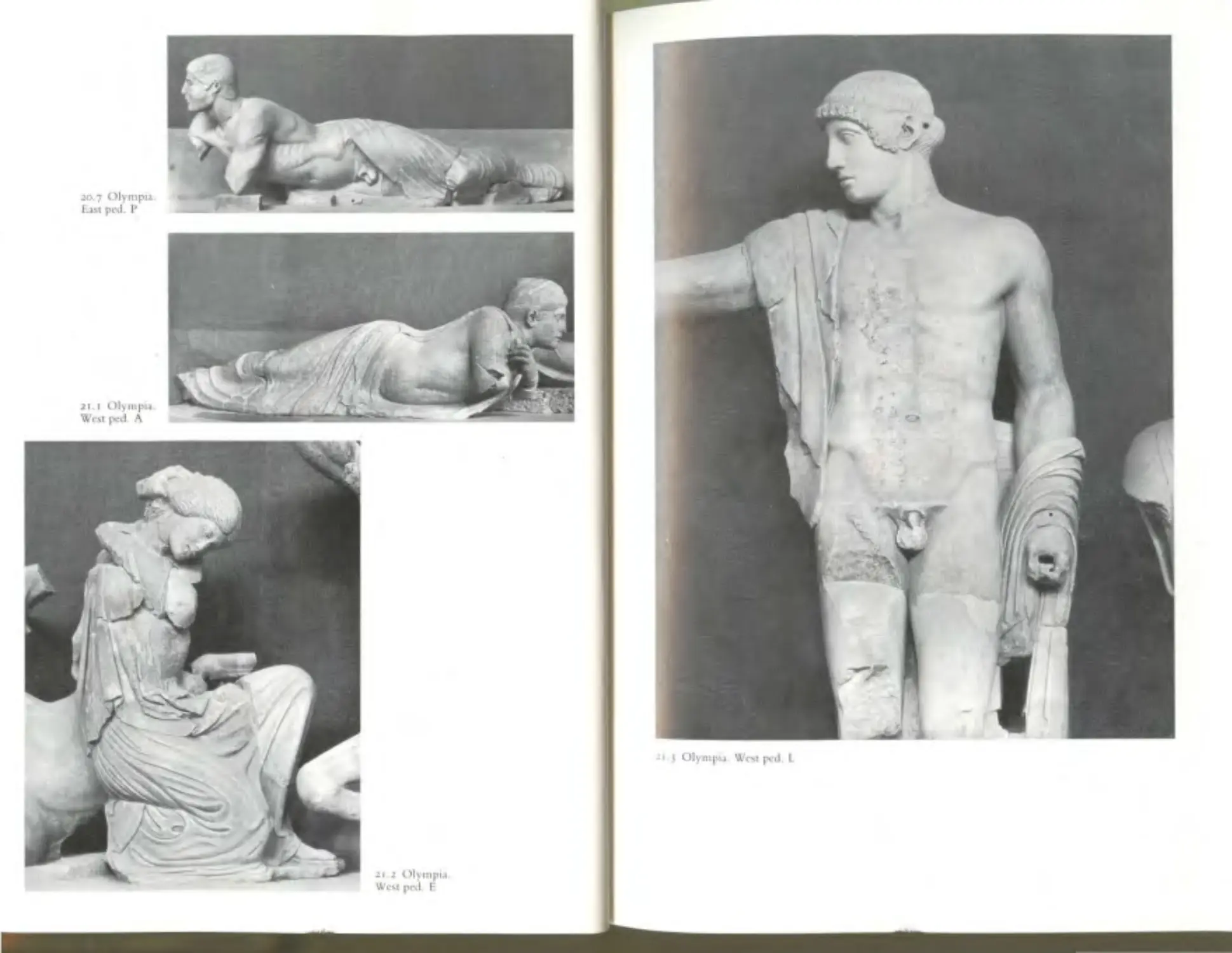

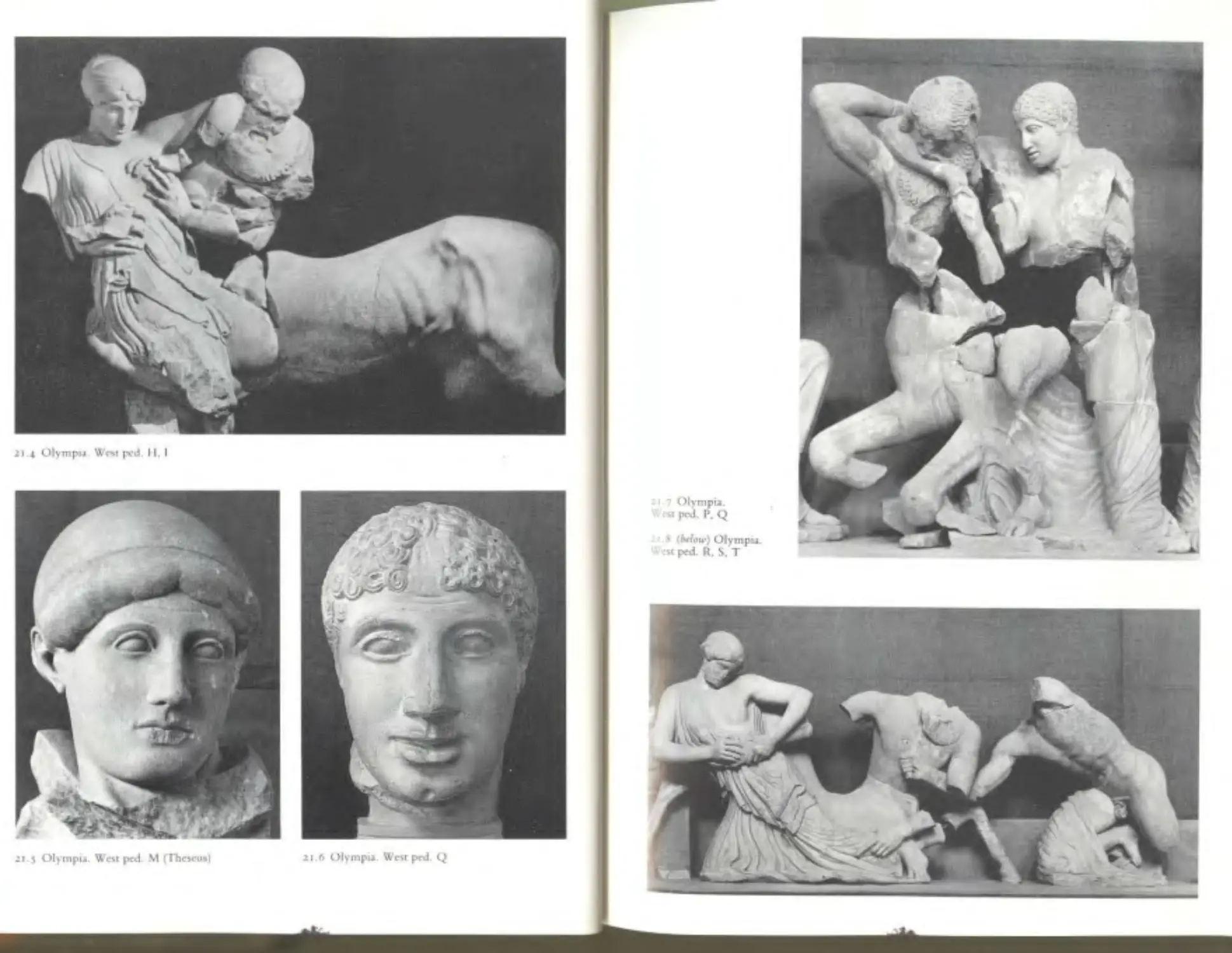

The west pediment [19, 21] displays a bustling challenge to and defeat

of hubns, a divine and heroic stand against bestial beh aviour. Pausanias

thought the central figure was Peirithoos, whose marriage it was that the

C cmaurs di sturbed, but t111S must be Apollo, son of Zeus and d1 spenscr

of law and order. The story is se t in Thessaly and though A racad1a coo 1~

ccntaur-countr y , lt could not be imagined elsewhere. The theme is much

used n fifth-century art, often, lt seems , as a comment on Greek

ccc:,ses over the barbanans or over barbanc bchav10ur by fellow

~reek>. but this is hardly the message here. There is still some

u nccrcaun y about the placmg and tdenttty of figures m both pediments,

bnefly disc ussed here m the captions.

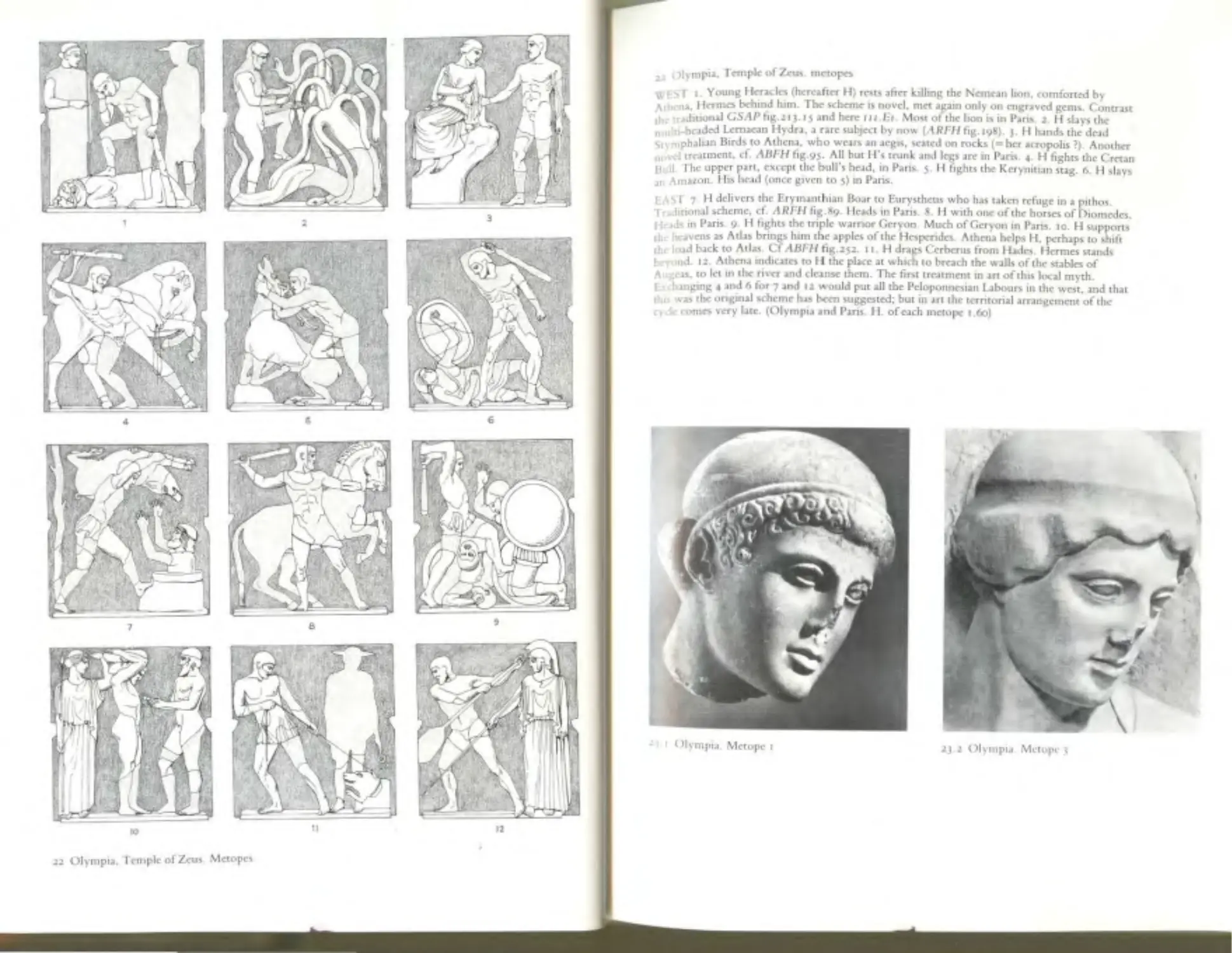

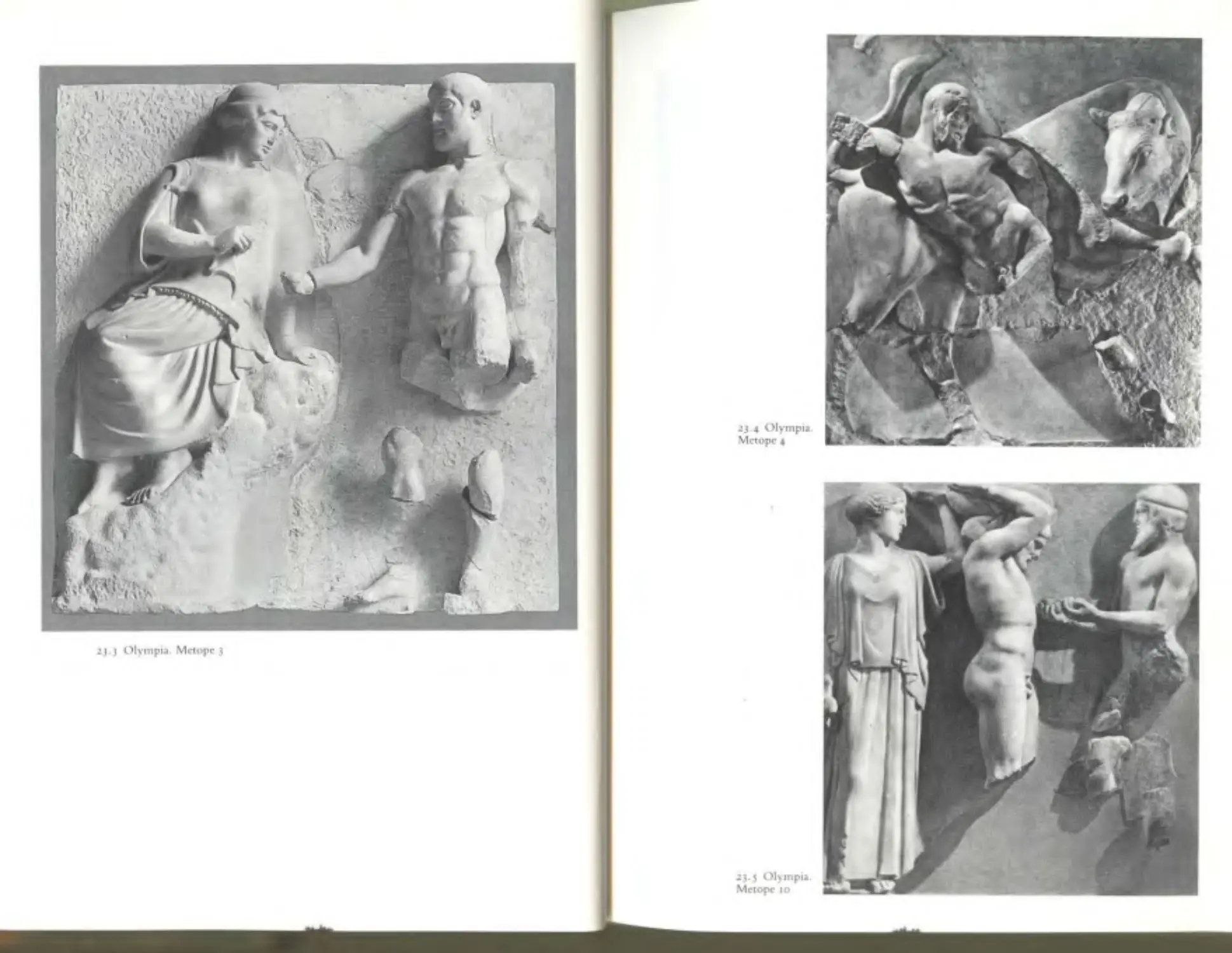

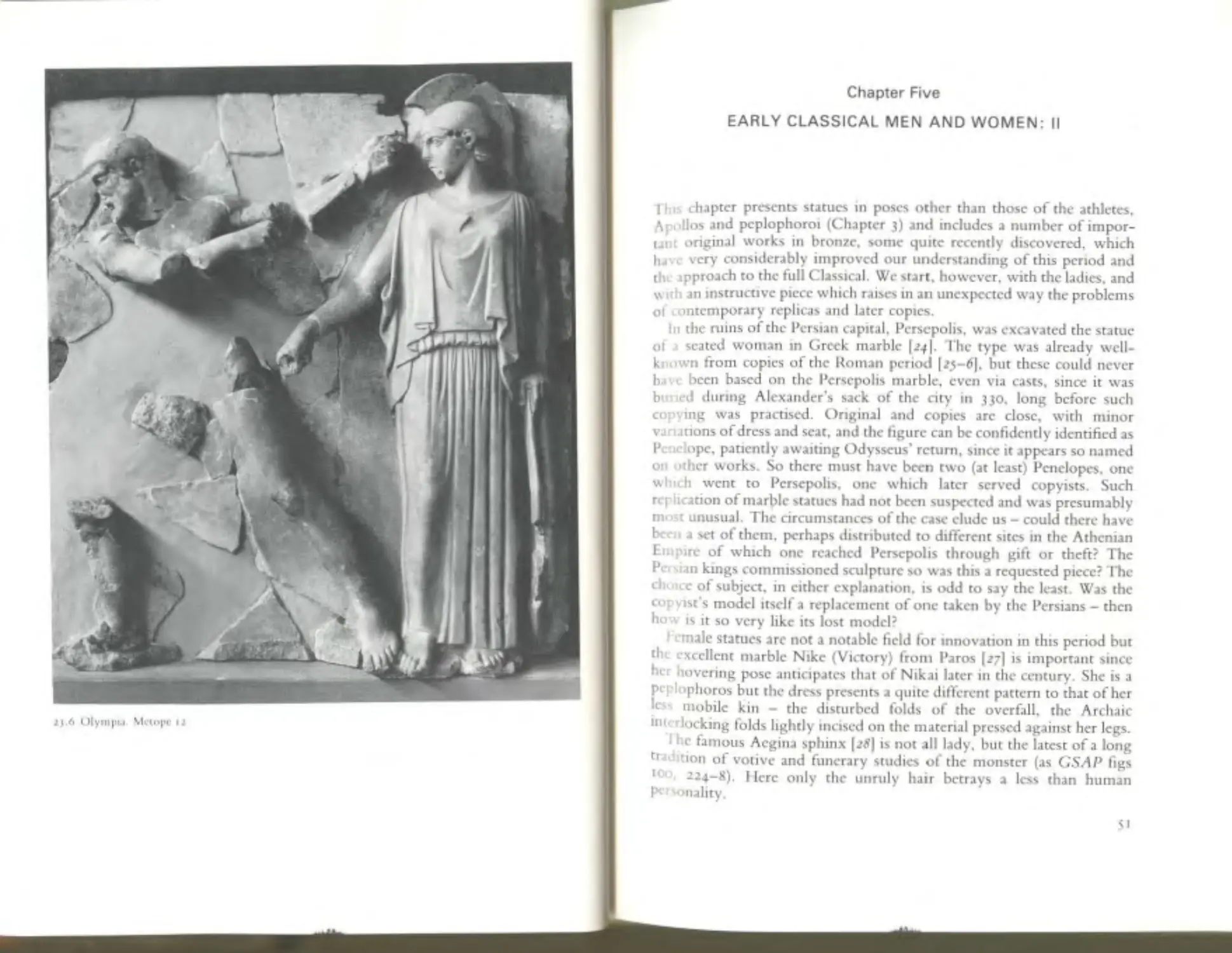

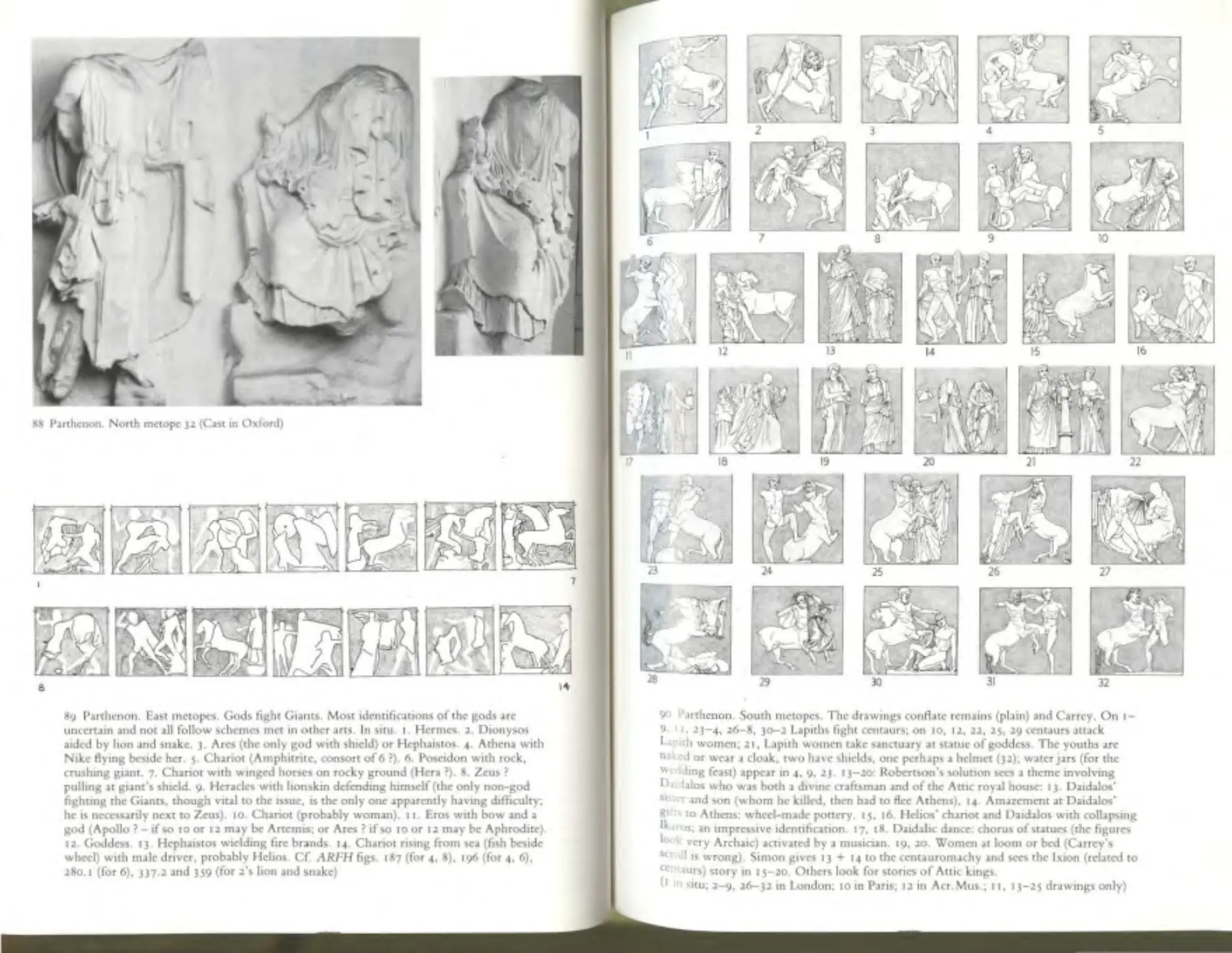

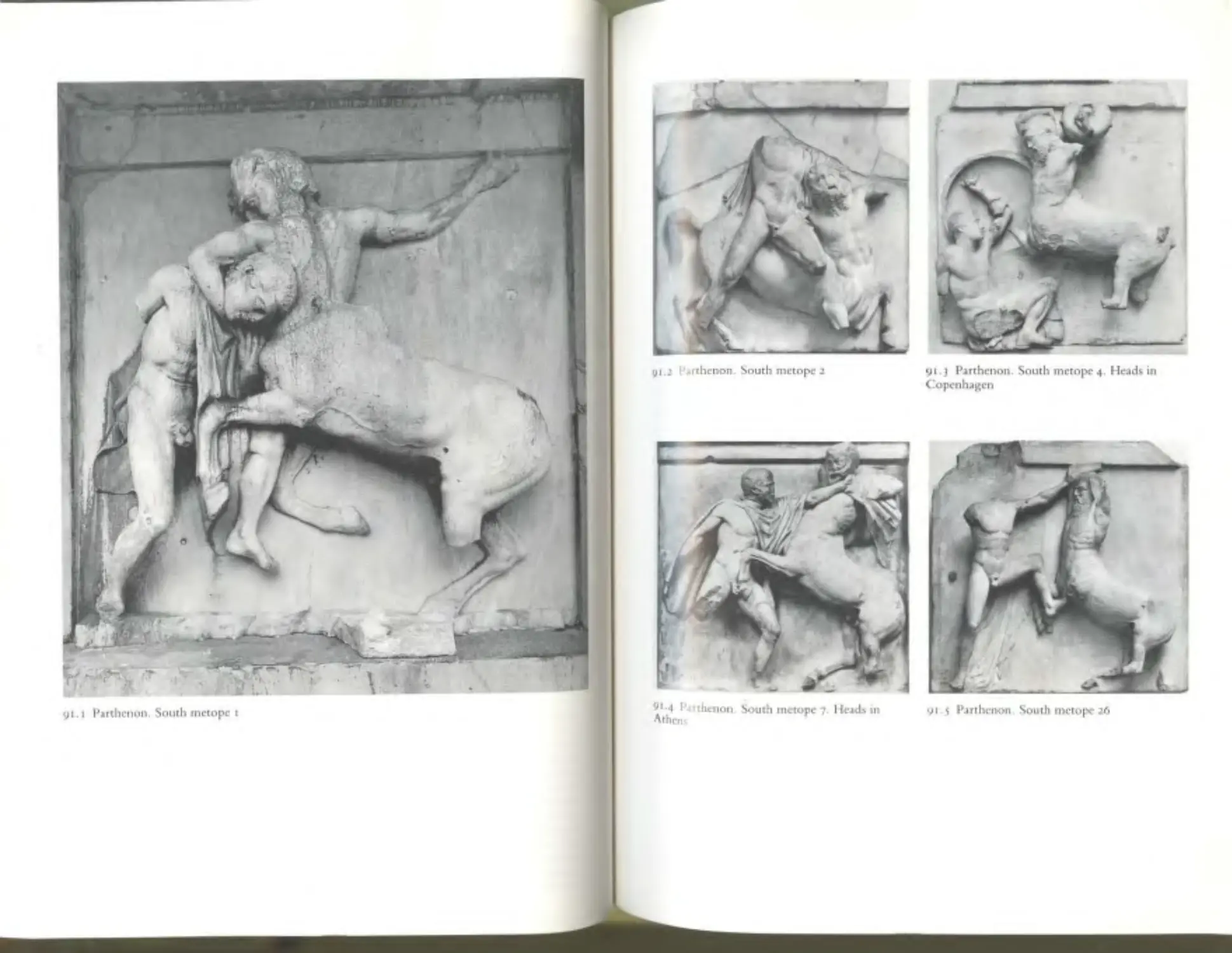

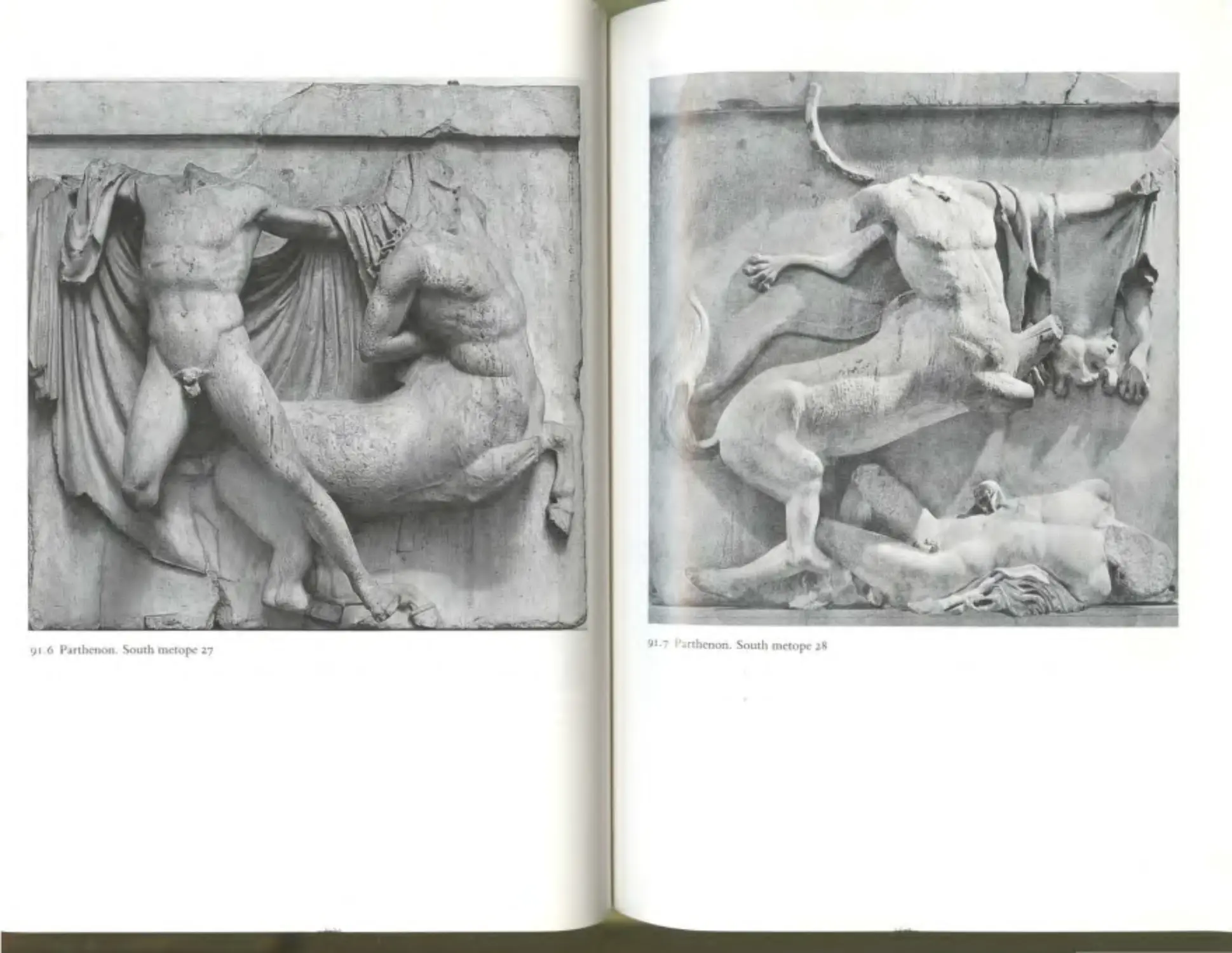

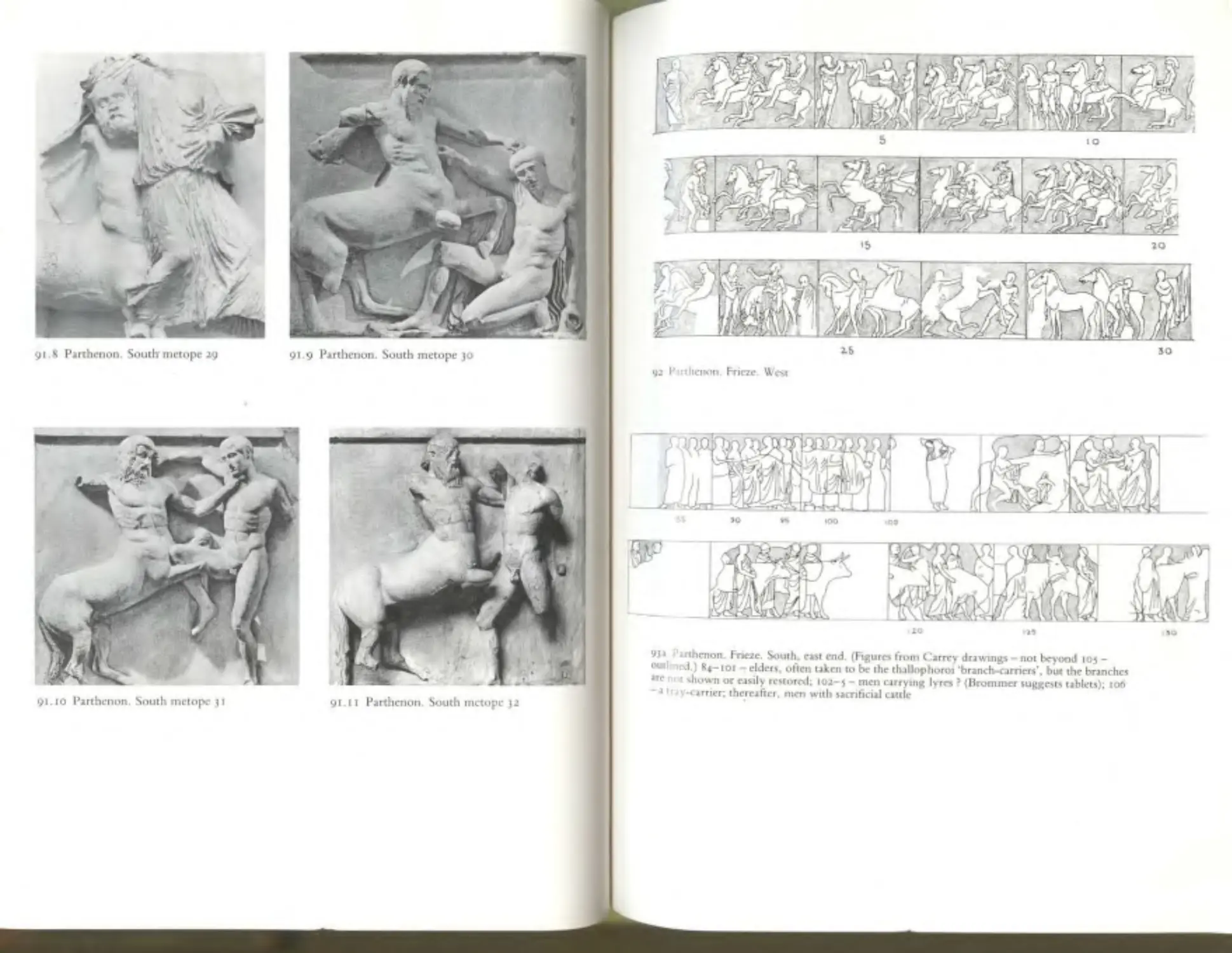

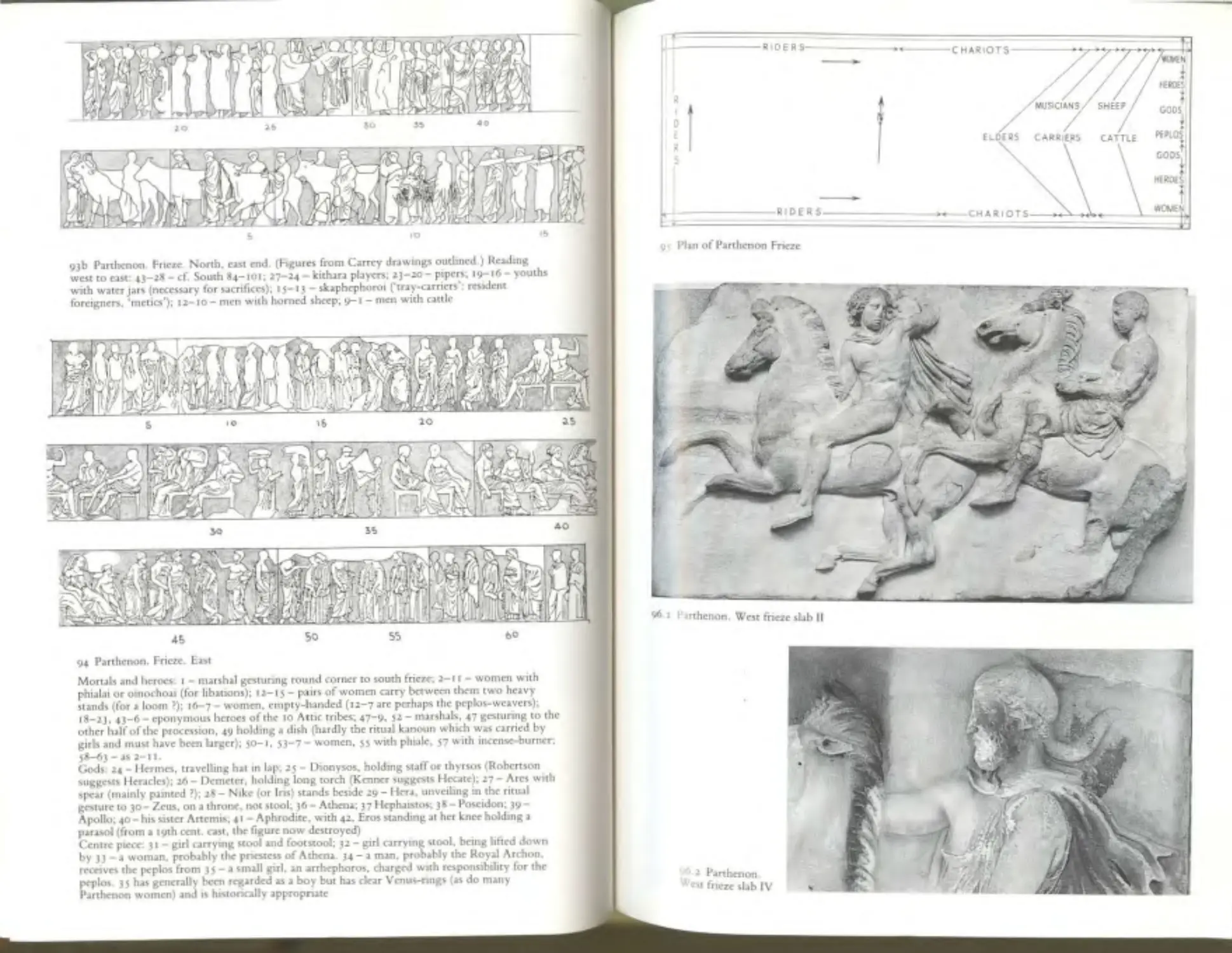

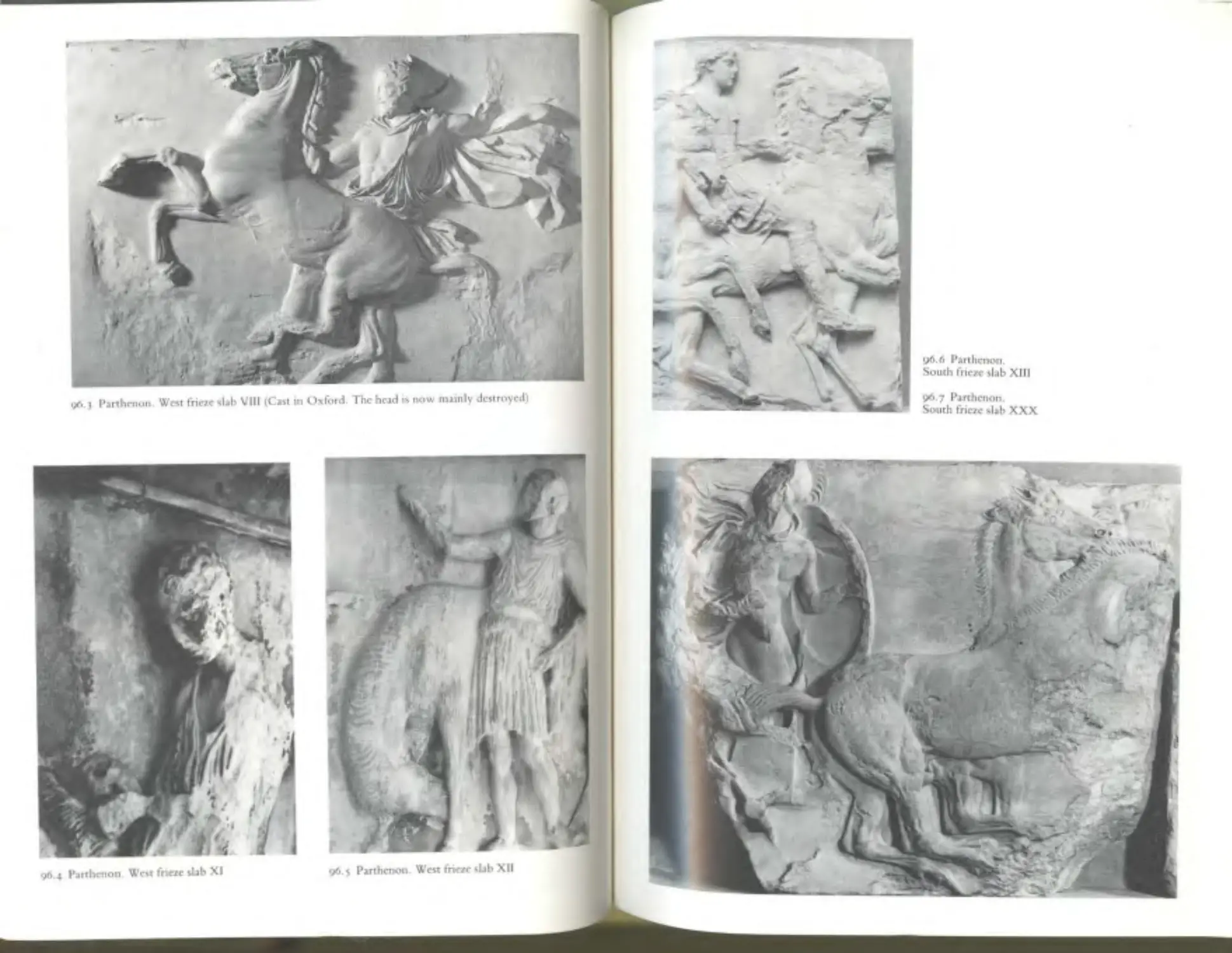

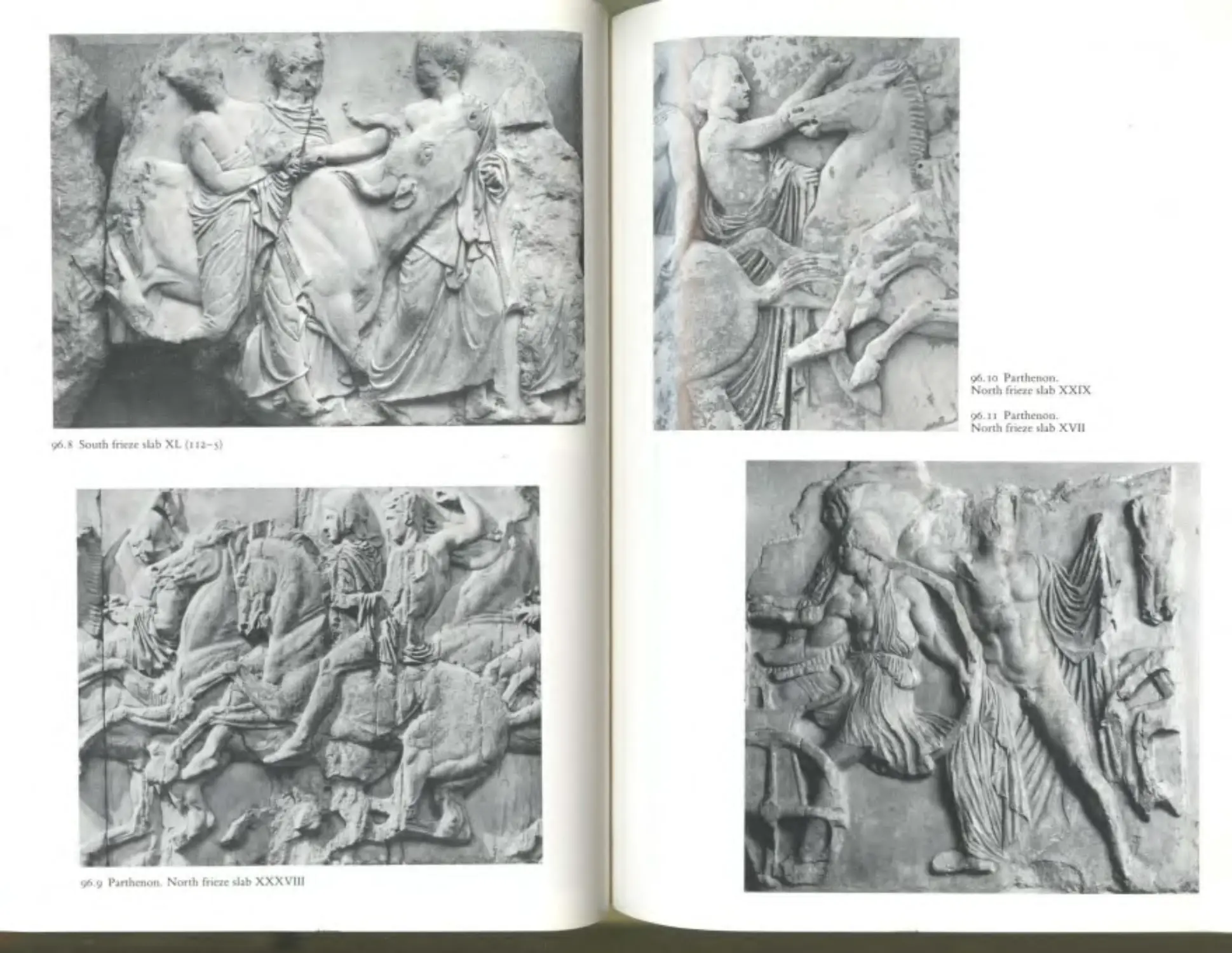

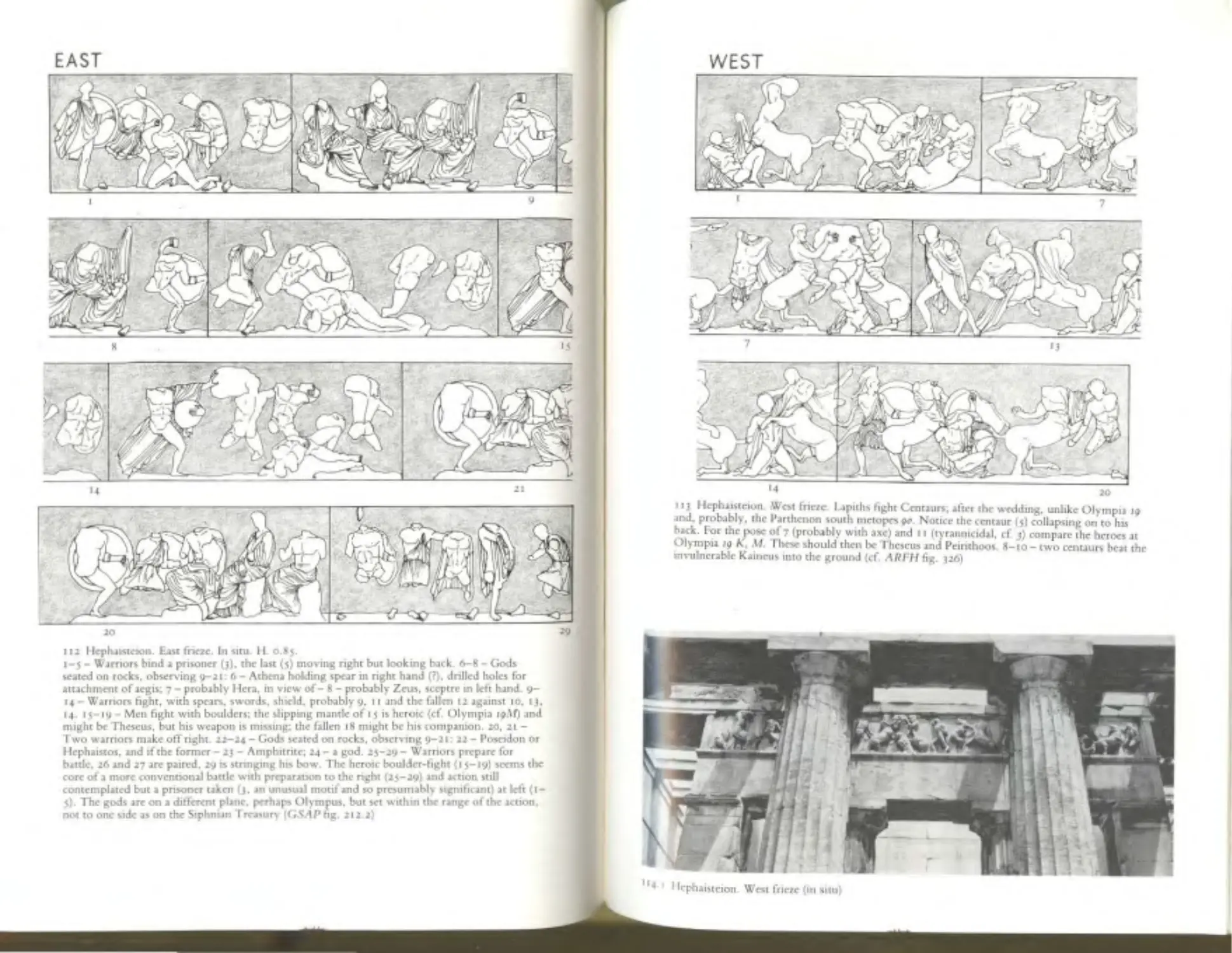

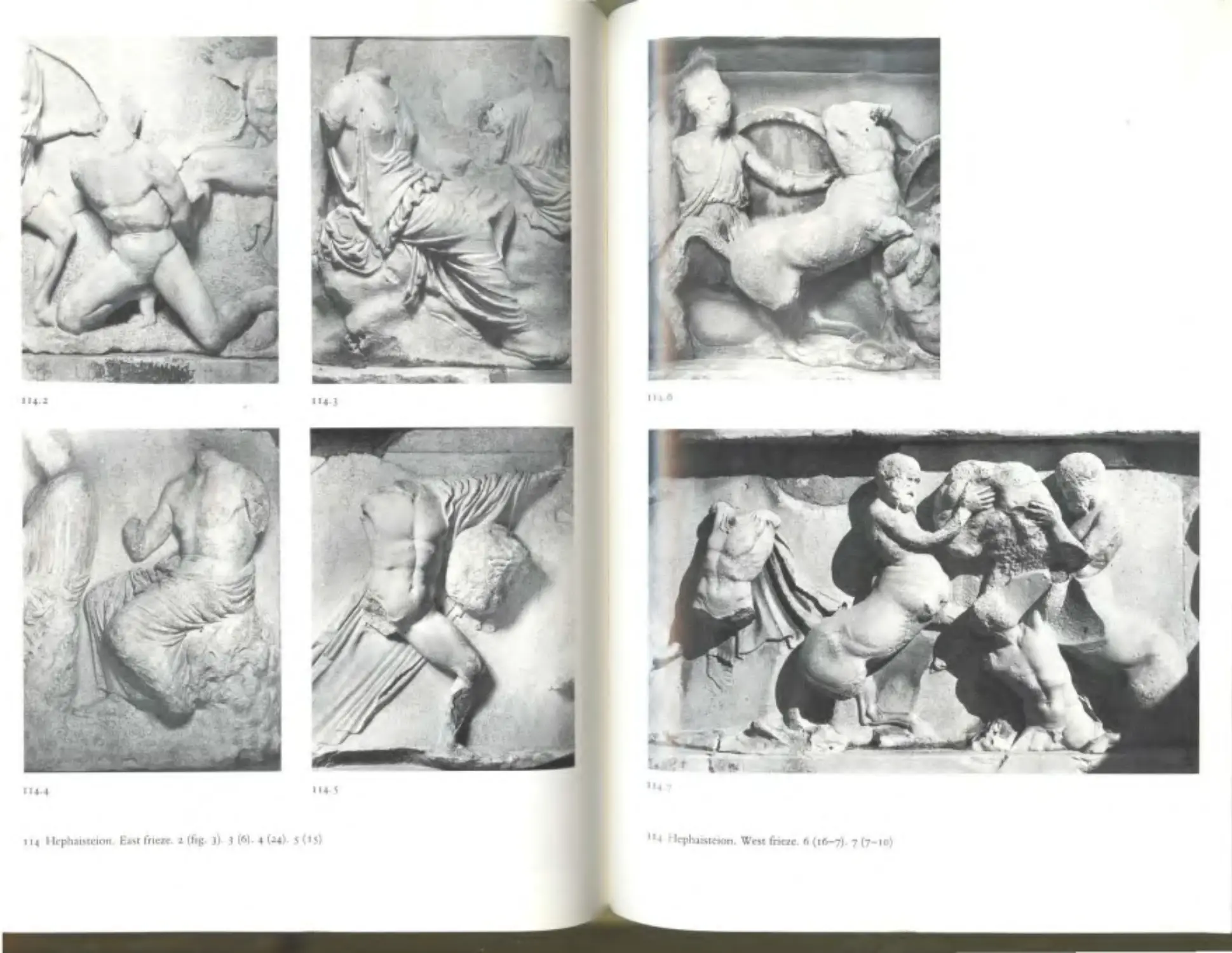

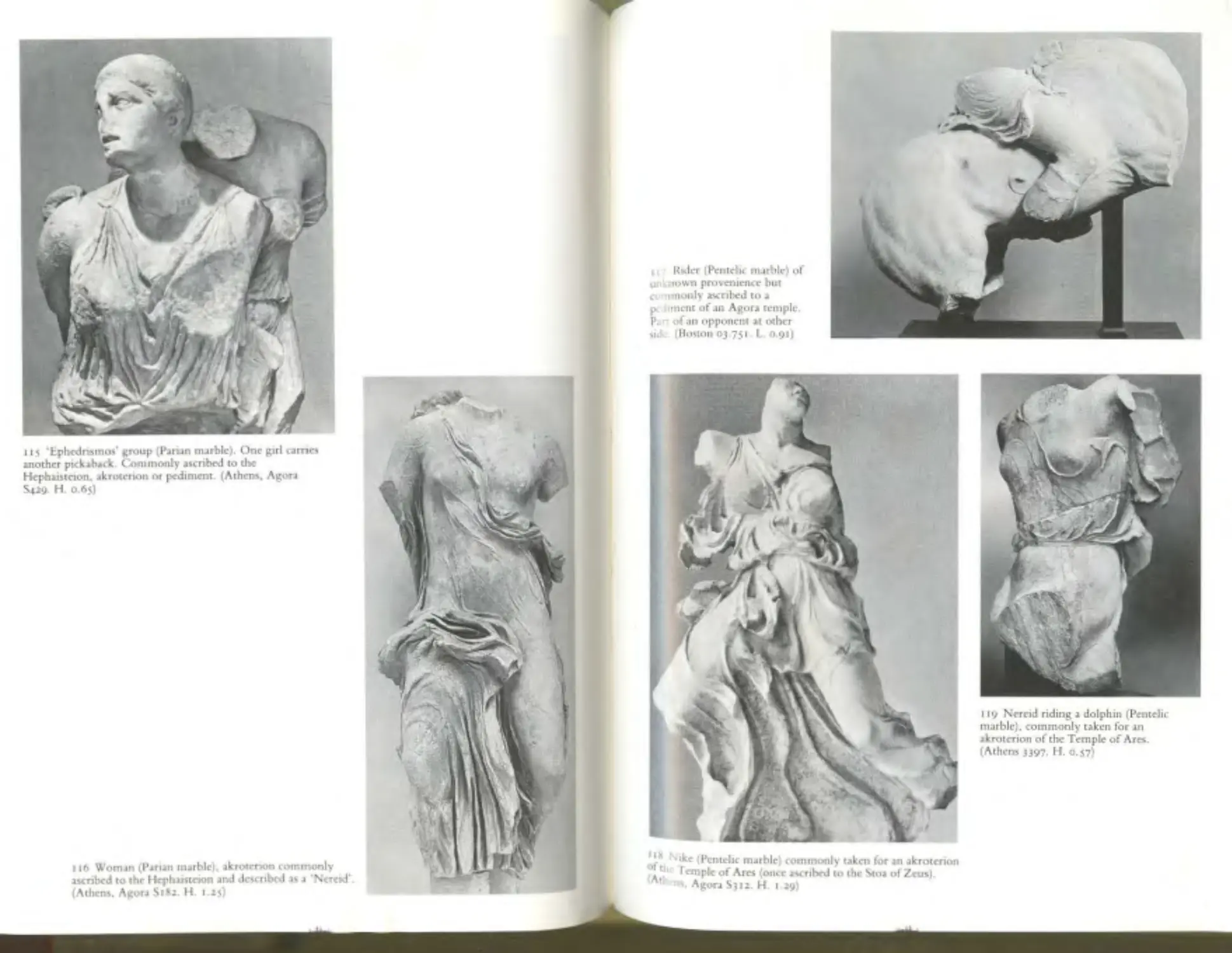

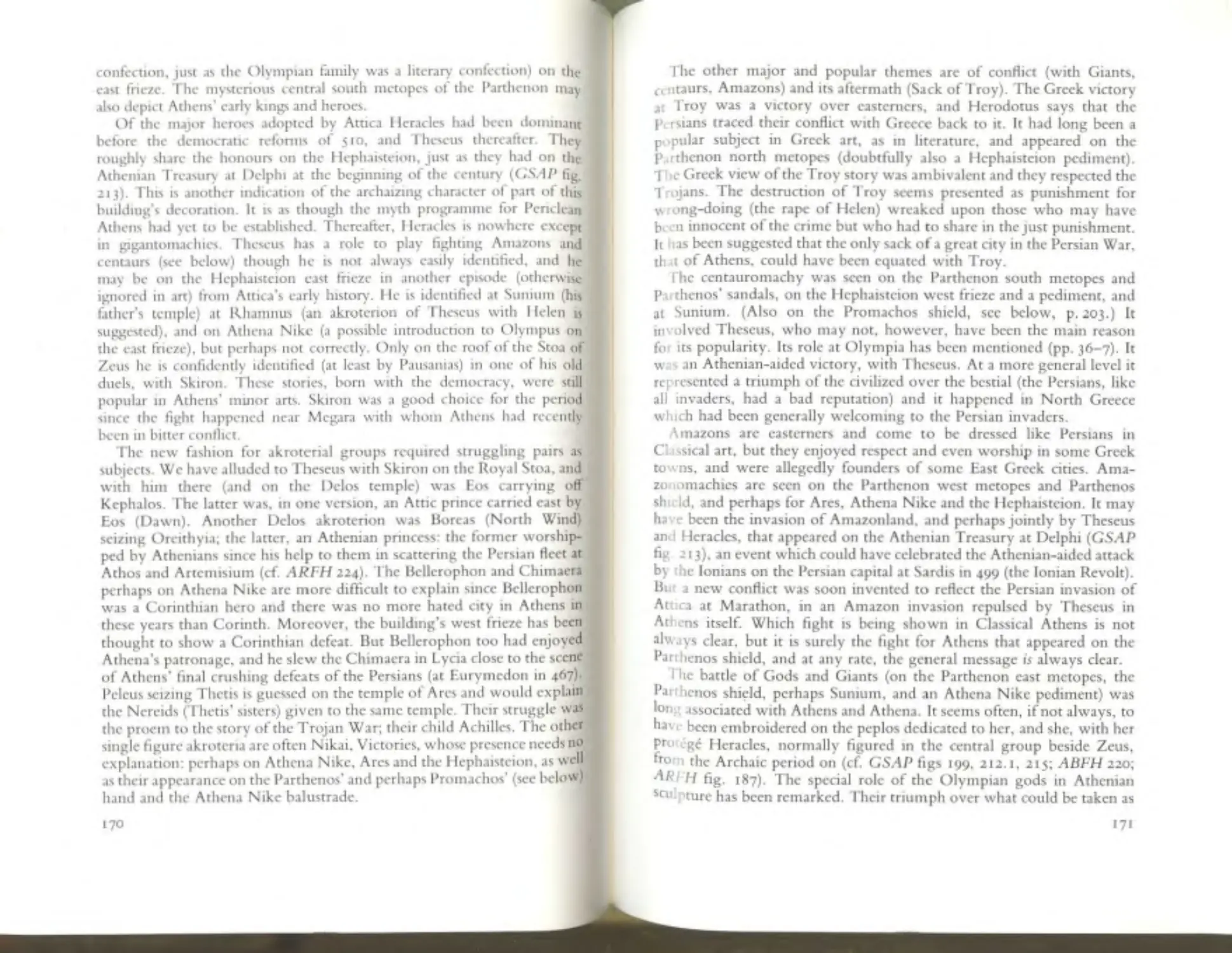

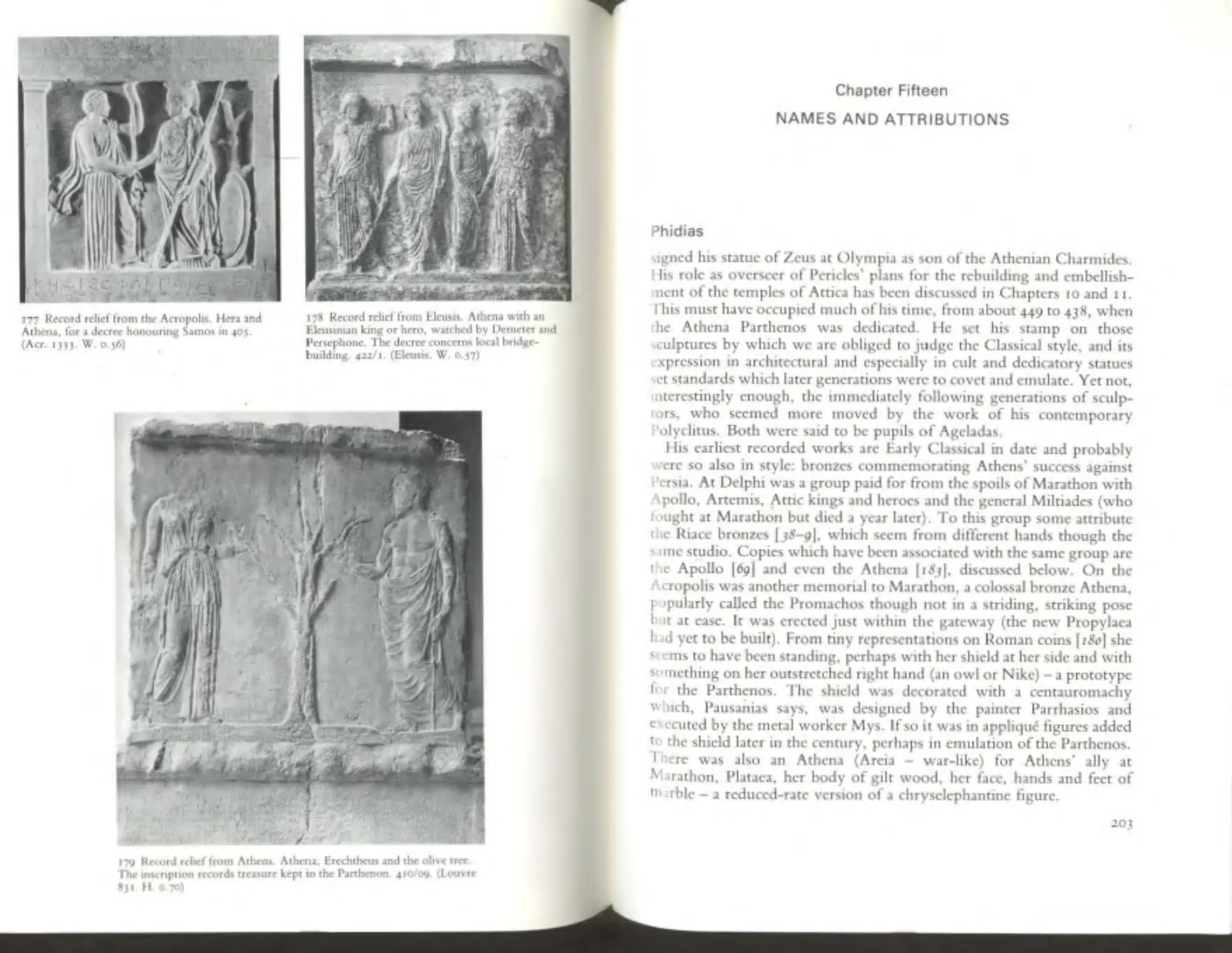

The other sculptural decoranon on the temple IS in twelve metopes

[zz-J), pla ced s1x at each end over the inner porches, the outer mctopes

all round rh e temple being left blank . They dep1ct the labours ofHeracles

an d Jll but o ne are mennoned by Pausanias and arc identifiable, although

some arc sadly fragmentary. Heracles, son of Zeus and founder of the

games, r cqu1res no cxplananon here, and the metopes probably help to

dcternunc the number, although not always the identity, of the

tradmona l twelve labours of later art and myth.

from subject we wrn to composition and style. The pediment figures

are re ~g hly one and half times life-size and the gods at the centre were

about 3 15 metres tall. They arc carved m the round, dowelled on eo the

pediment background, but much o f the backs of most of the figures was

n ot fnished and some were partly ho ll owed, to save weight. Some parts

o fftgmcs were sl ice d off at background lev el , especially the centaurs, and

th e ,t a riot horses were slightl y angled out from the background. The

depth of the pediment floor is nearly one m etre. The material is island

m arble

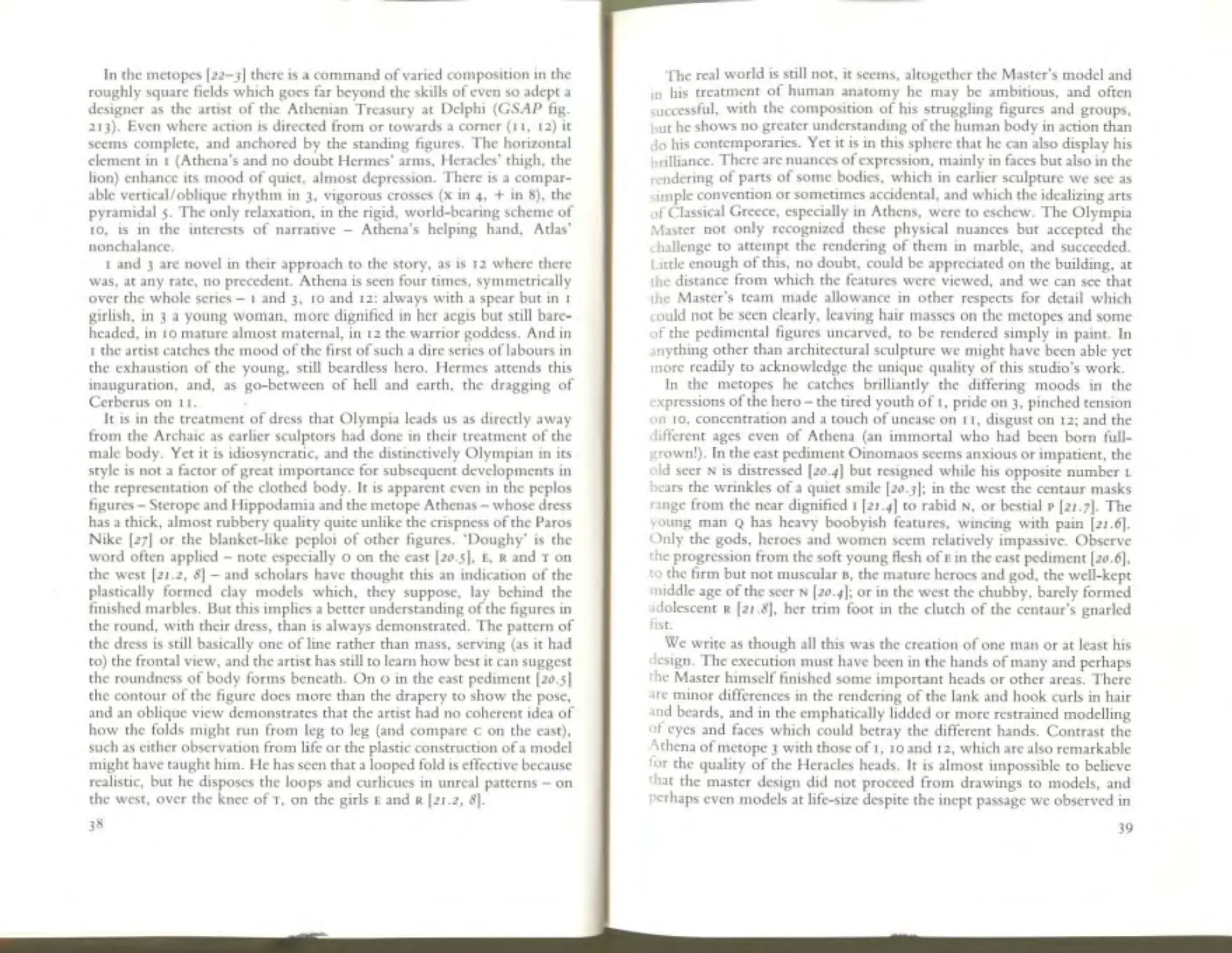

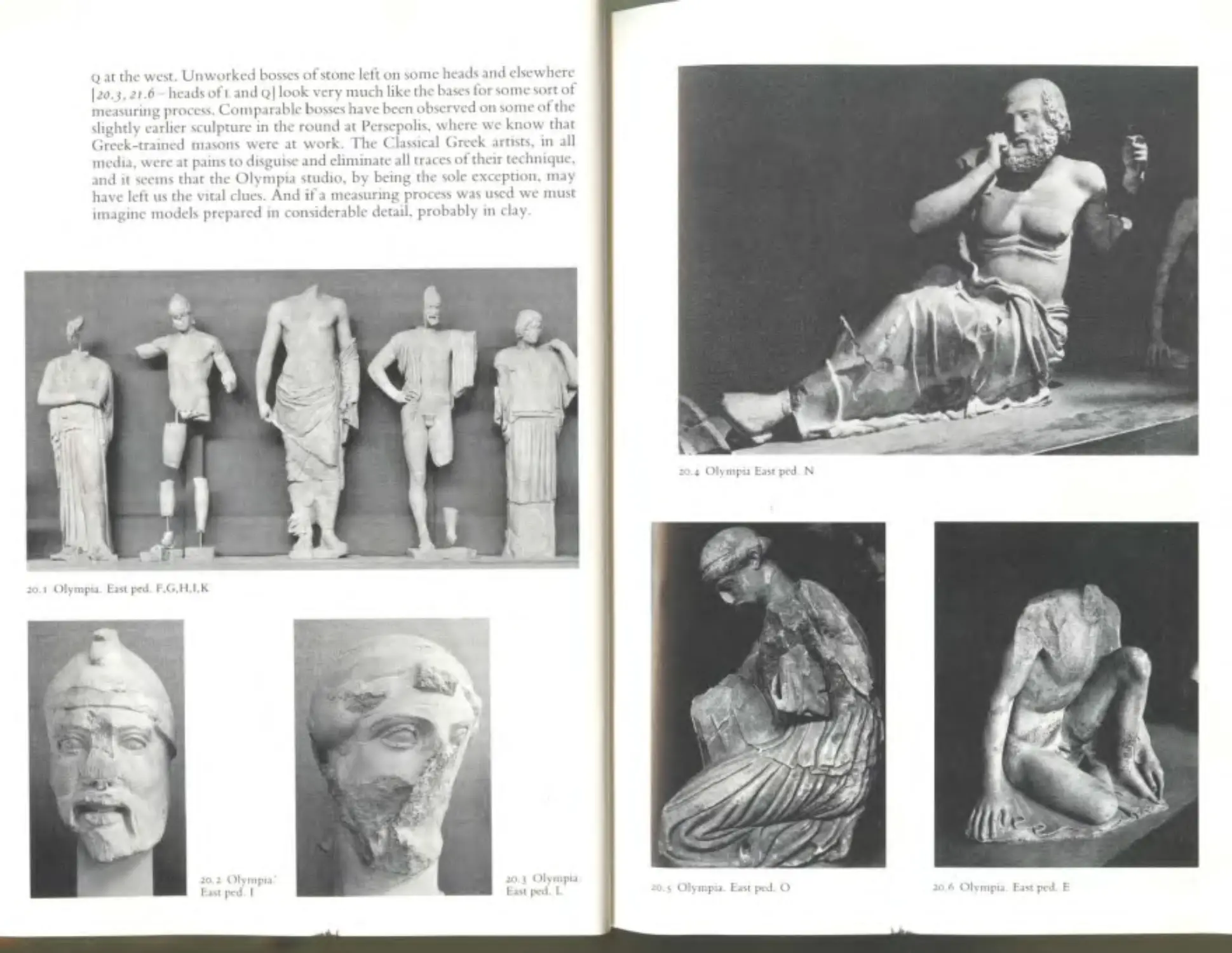

The co mposition of the cast ped1m e nt [1 8] IS statiC- only knowledge

ofits subj ect allows us to savour the tense mood. Accents are vertical, the

central group in particular, four-square over the m1ddlc intercolumnia-

u on of the temple fac;ade, seem m g almost part of the architecture of the

butldmg, and the symmetry of the other figures barely and sensitively

broken b y the diffenng poses of kncchng or reclining figures, horses at

rest 01 tunung. At the west (19) the fig ht surges away from the centre,

ro:Ju-.~ back on itself in the symmetry of the 2-2-3 groups of figures

wh1 present a zig-zag of vigorous movement, the action somehow

coni 1uous though the groups arc d1screte. llere the challenge ofdepth is

mo• Immediate - at the cast there were only the horse teams, neatly

splJycd 111 the shall ow field. While the fig ures of the fighting groups

natur ll y shrink back from the foreg round, like a fight on a mountain

path, still the girls' bodies arc held or swung across the a nimal bodies of

thetr l ttackcrs )21.4 , 7), and provide th e first (a nd al m ost the last) Greek

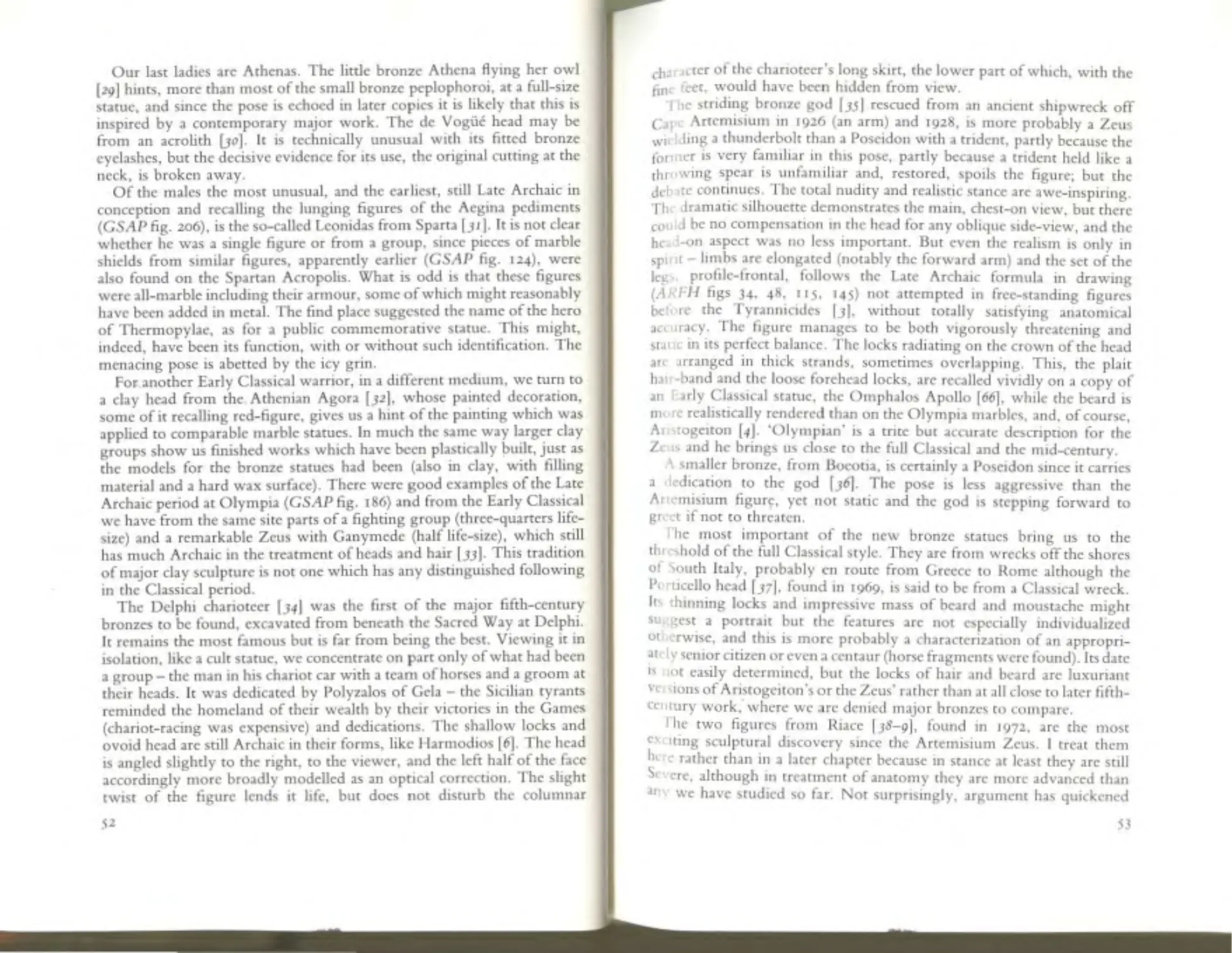

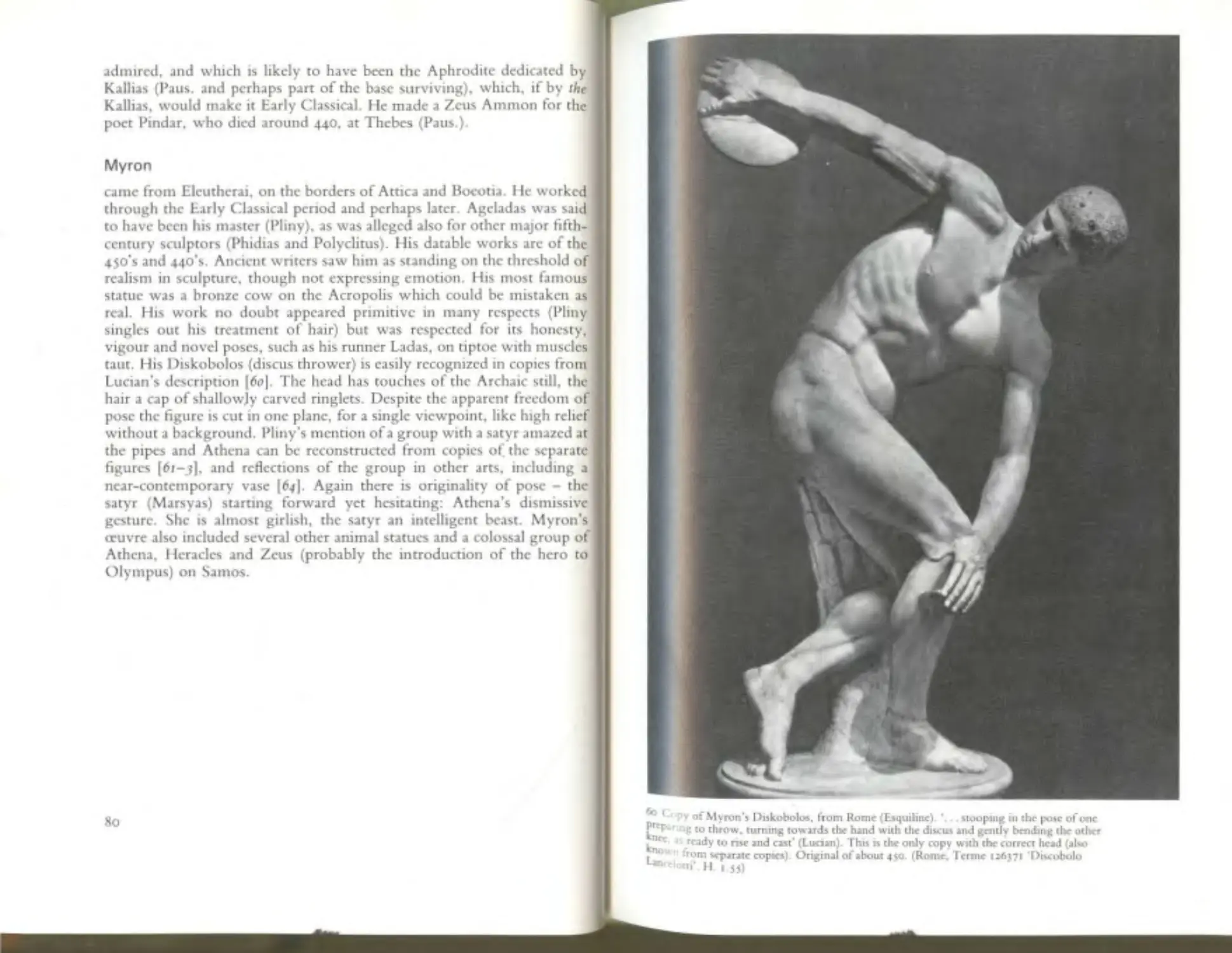

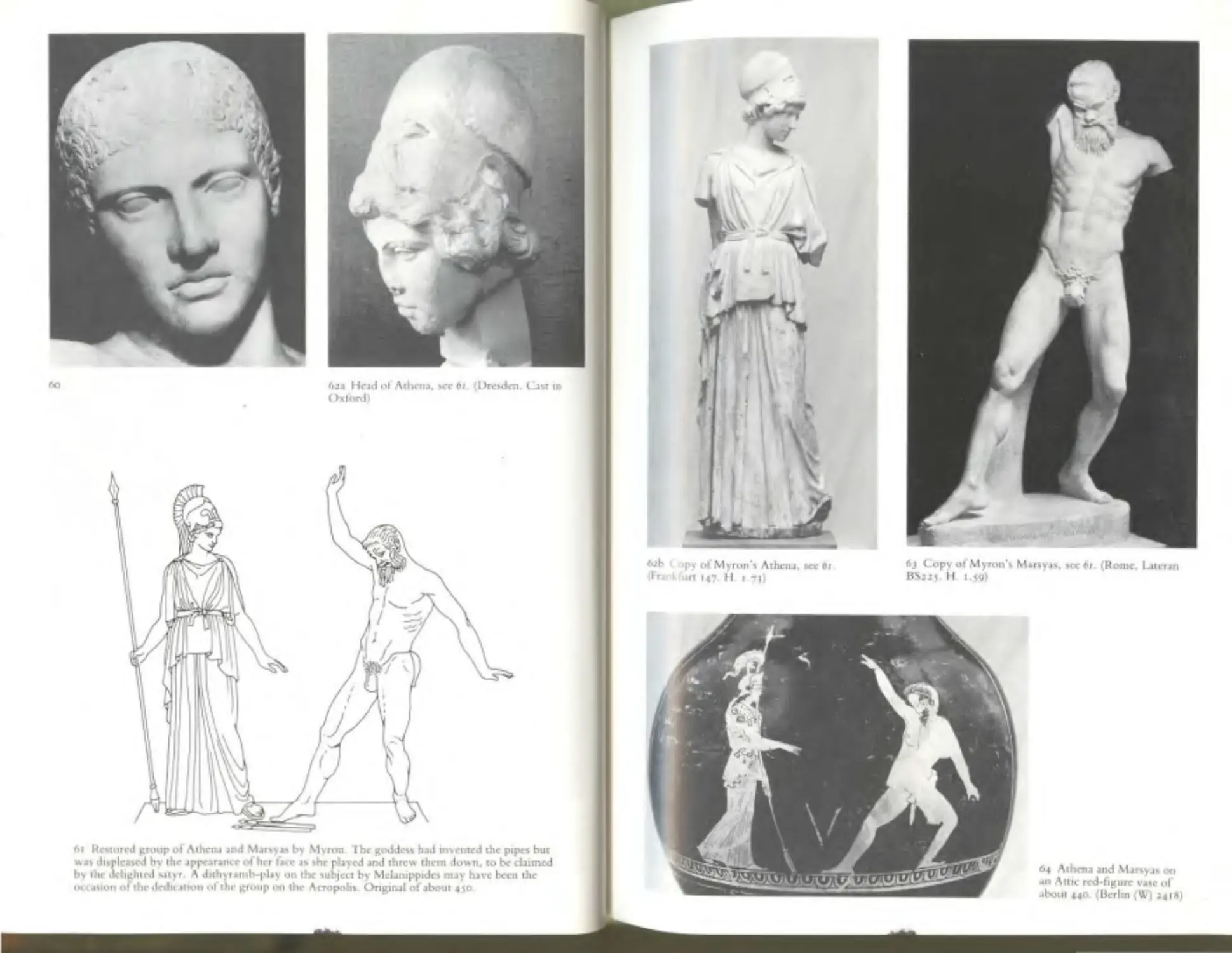

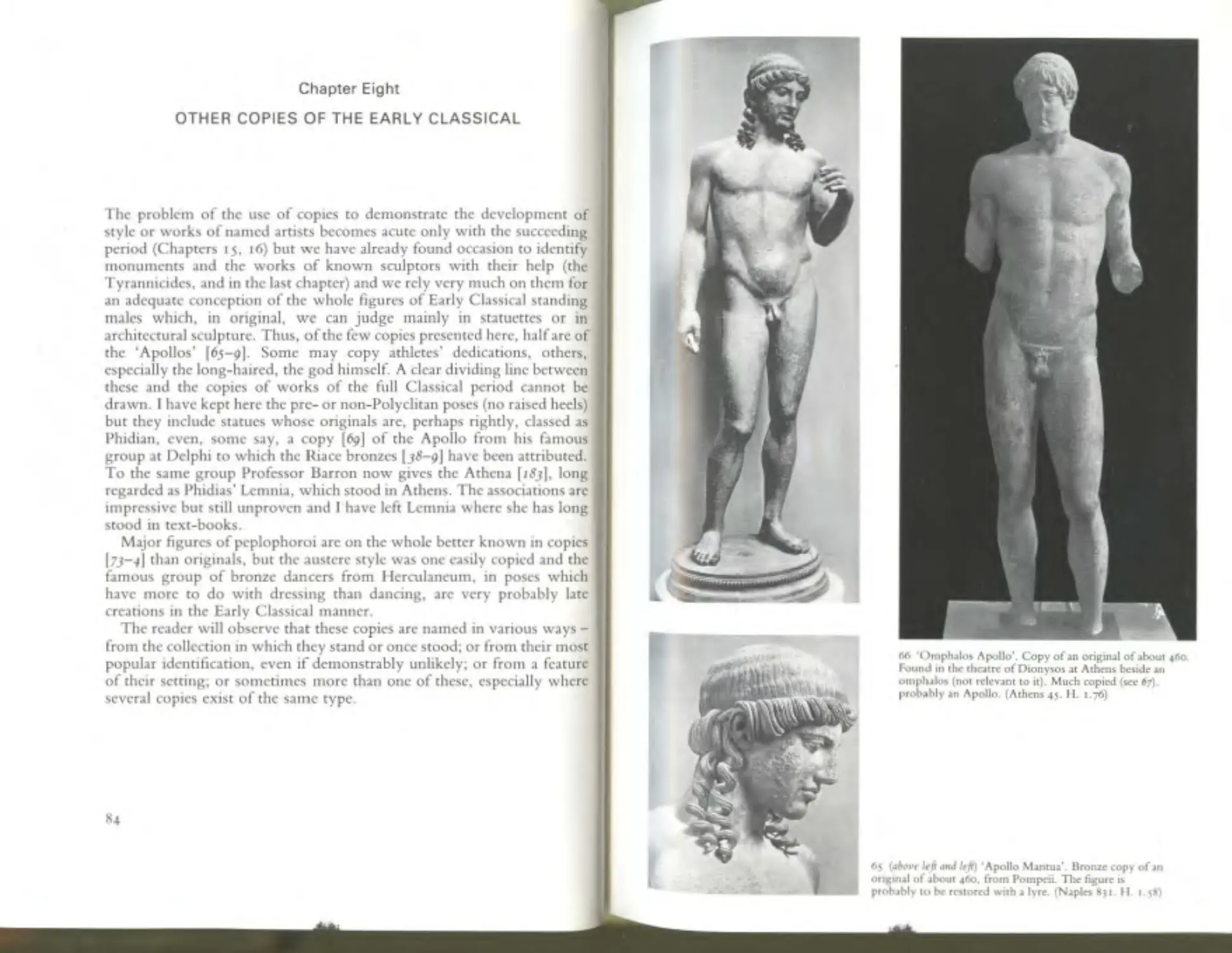

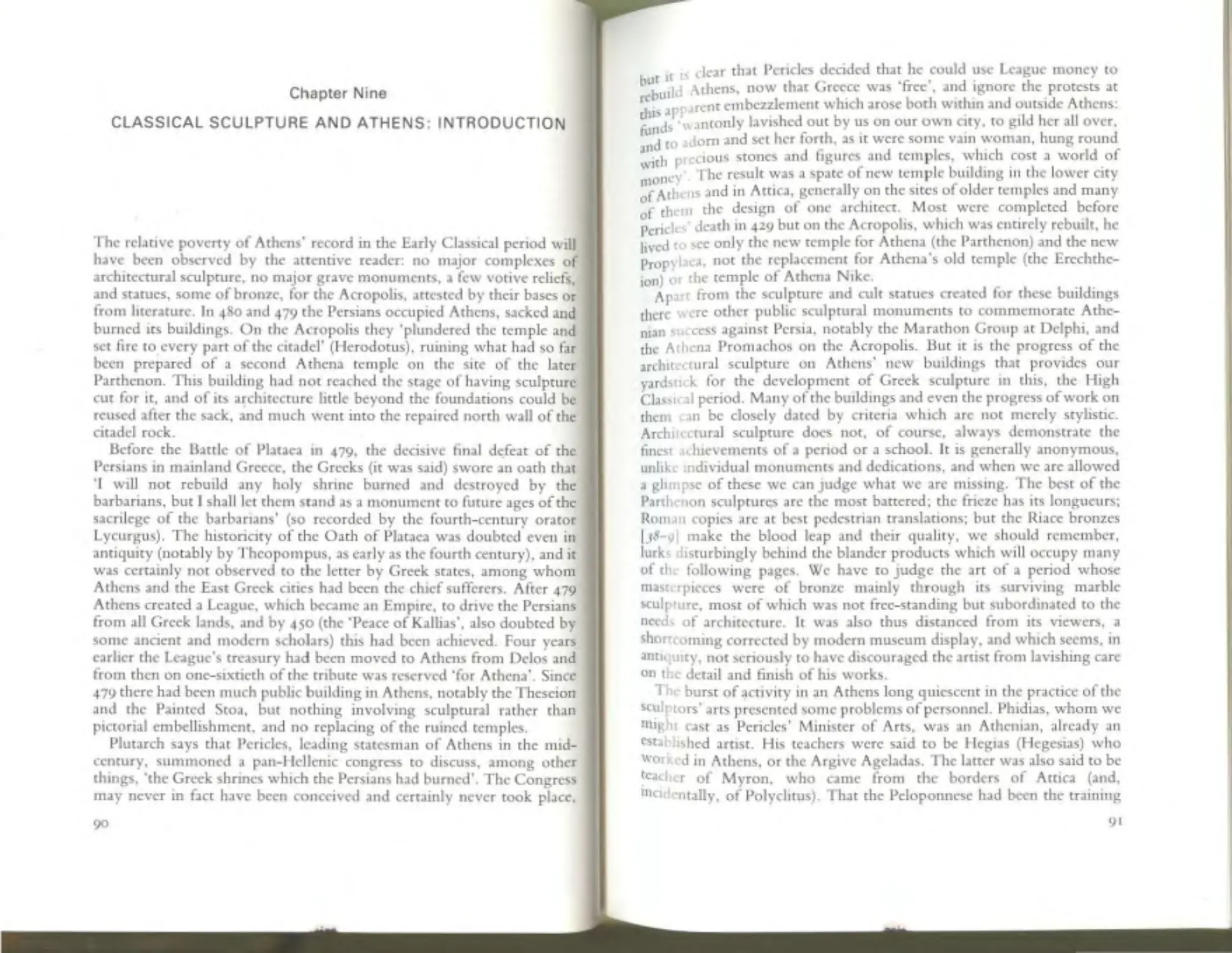

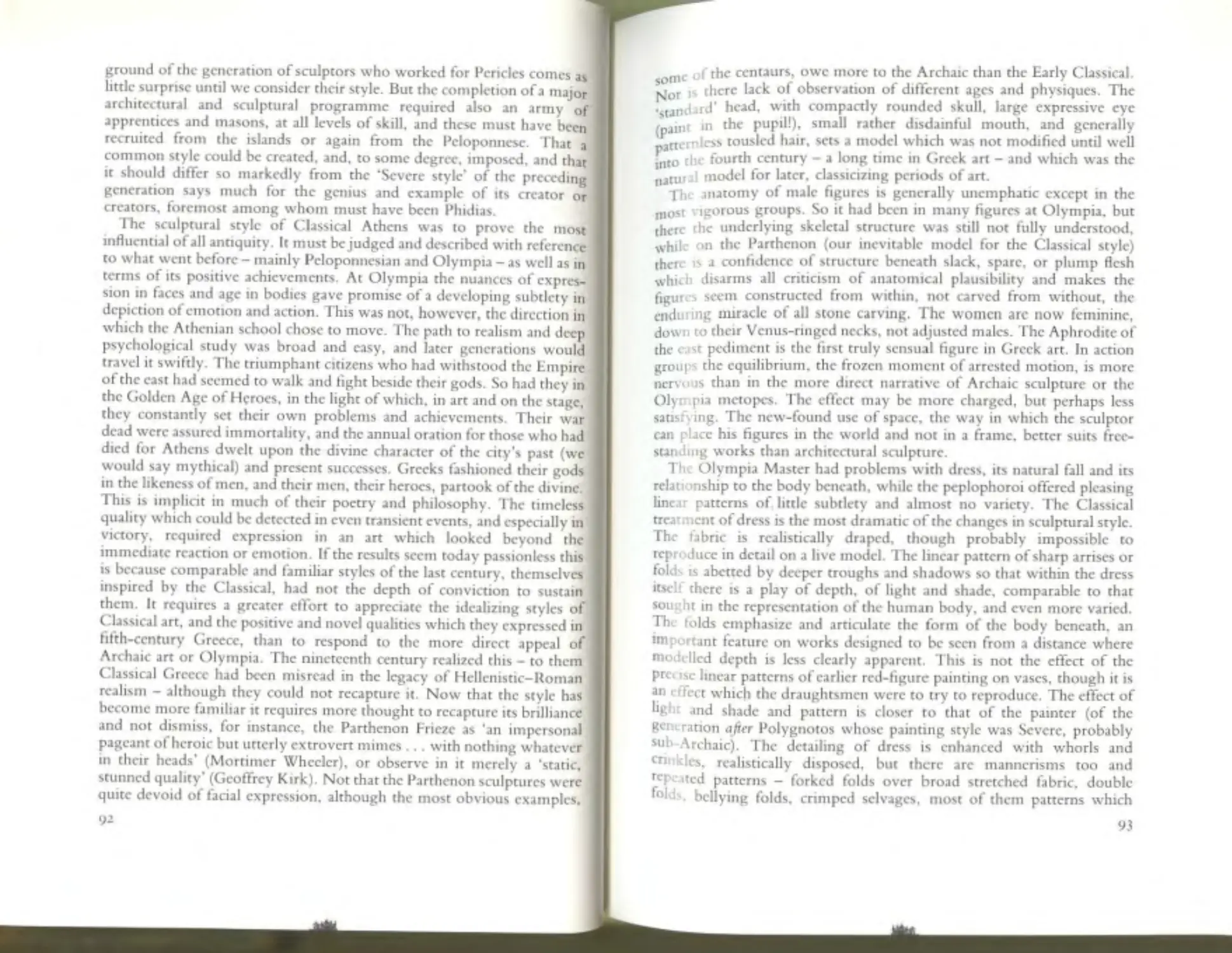

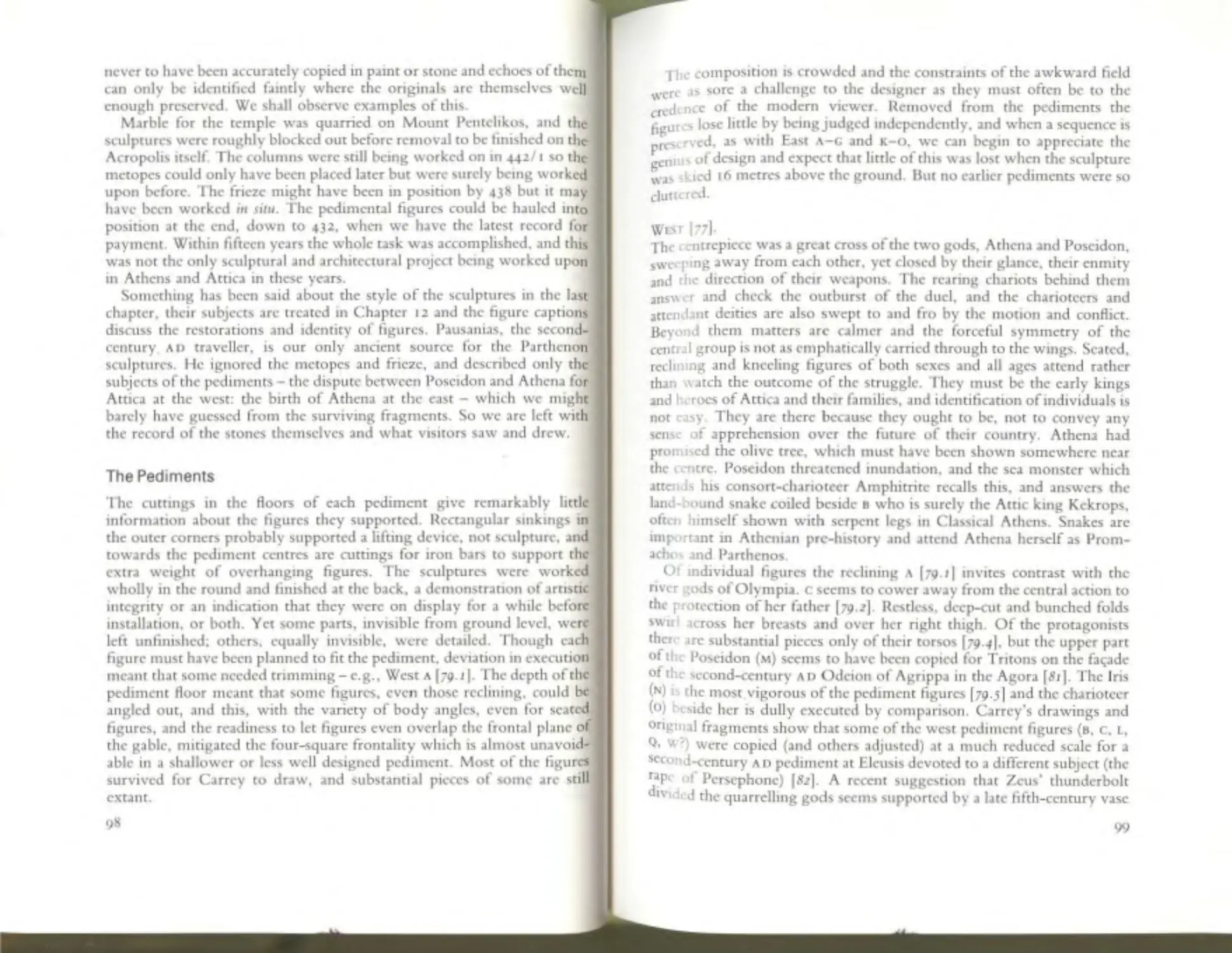

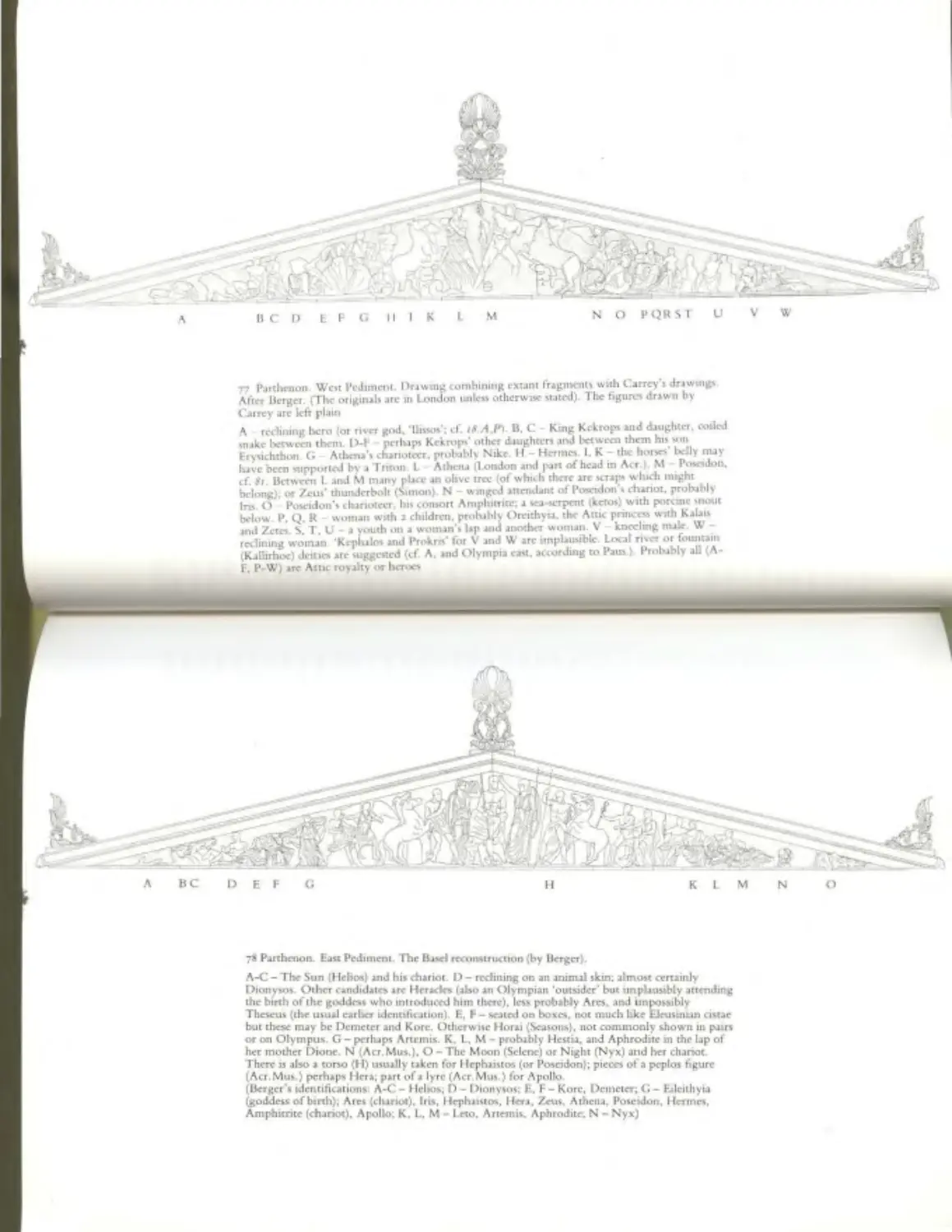

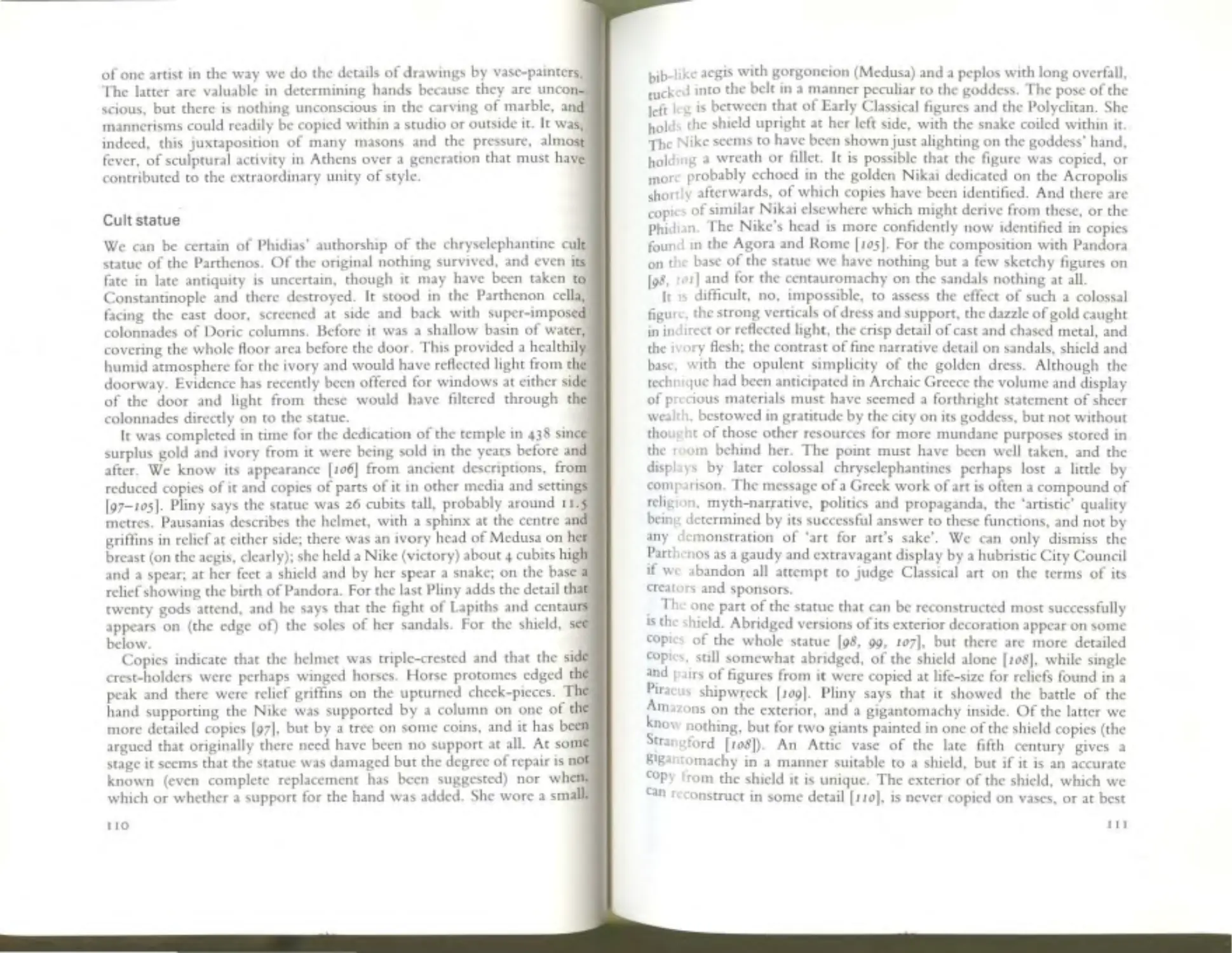

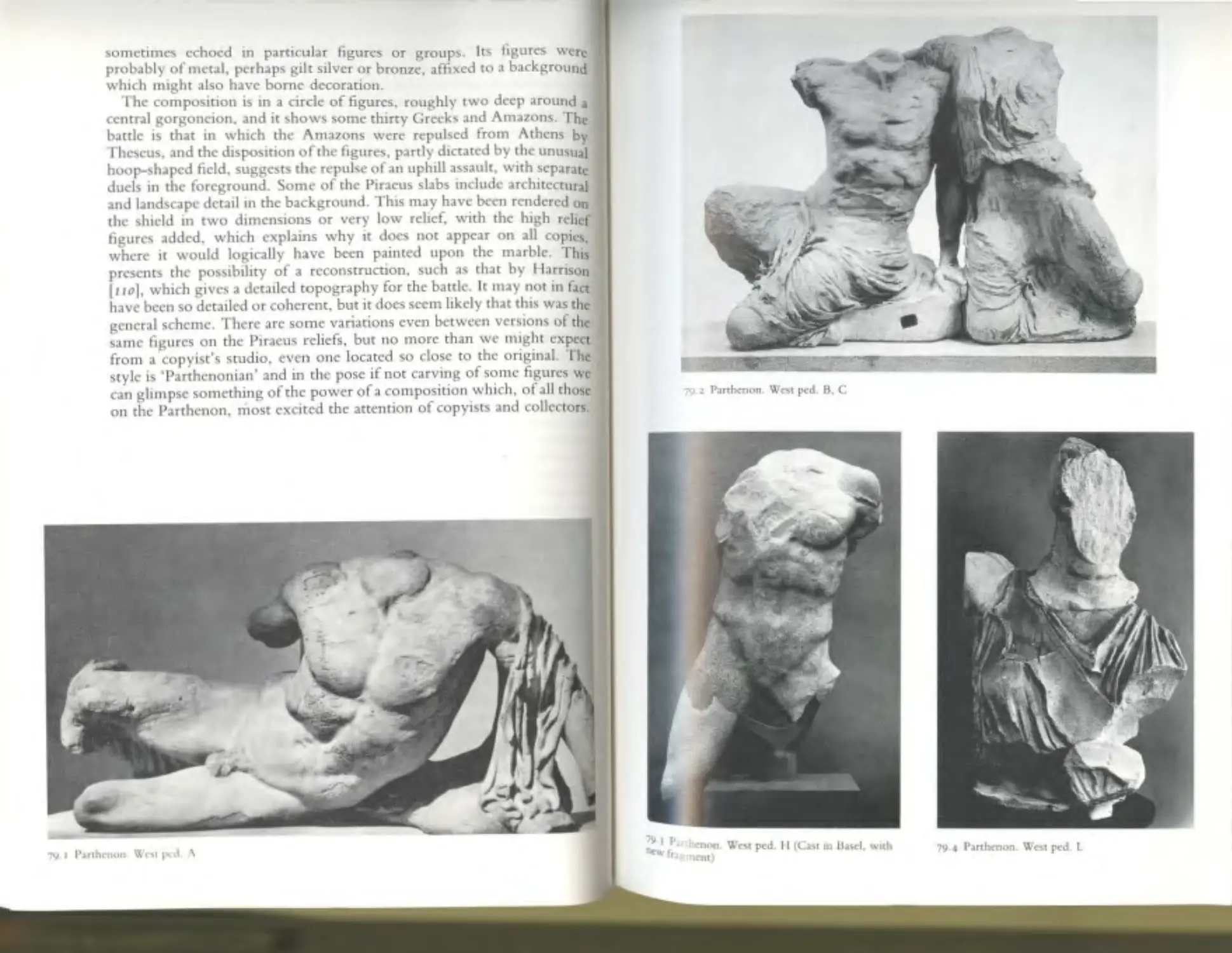

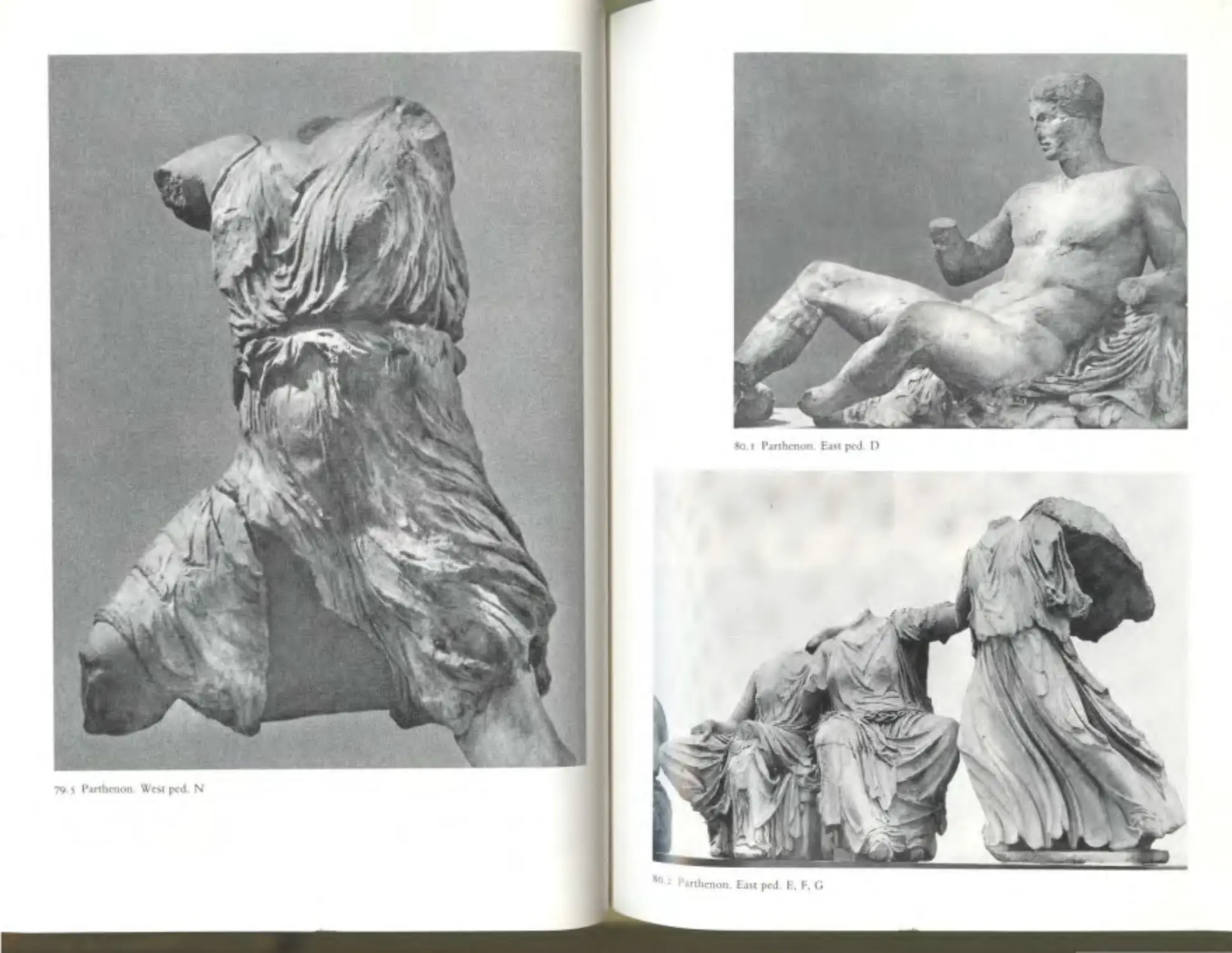

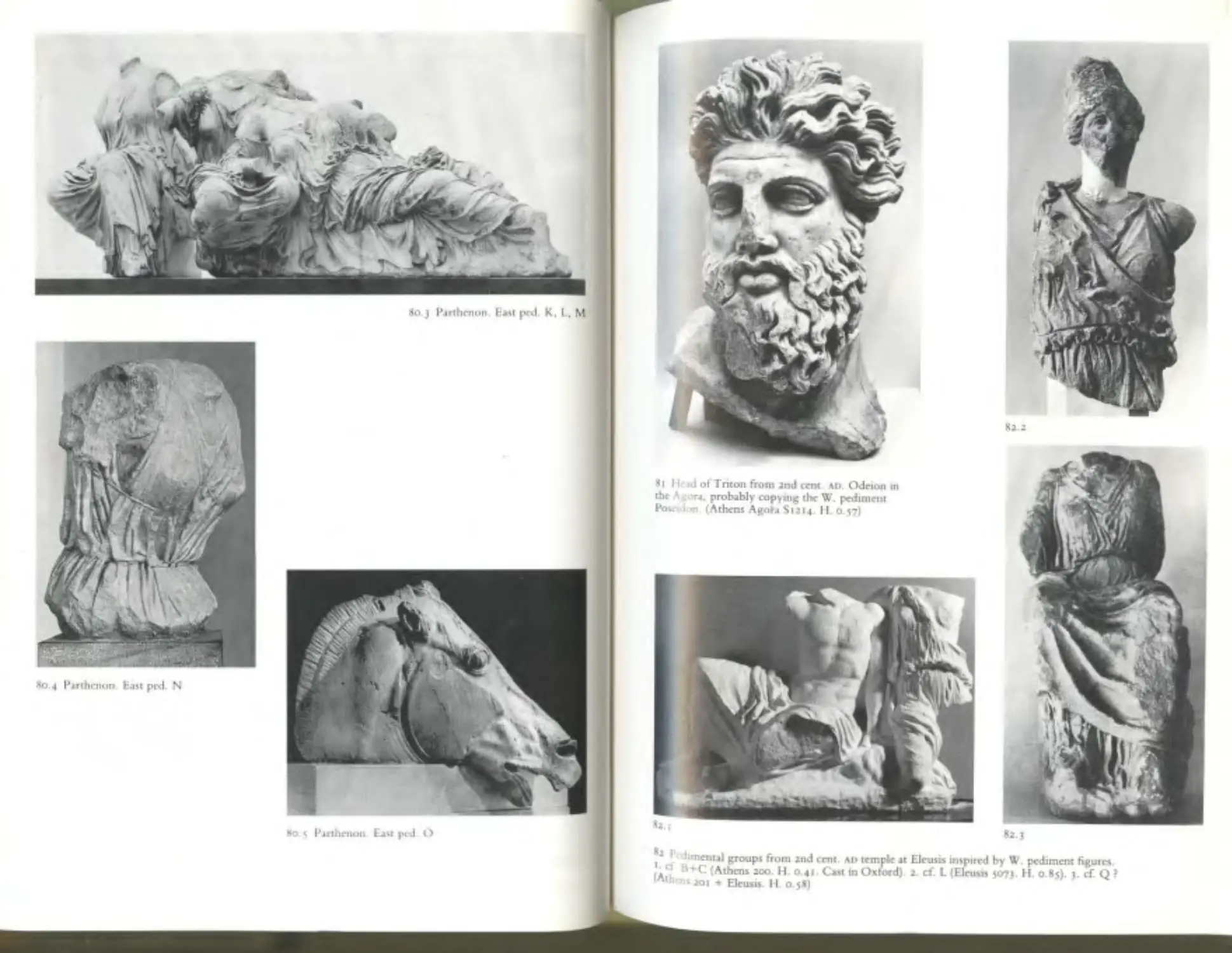

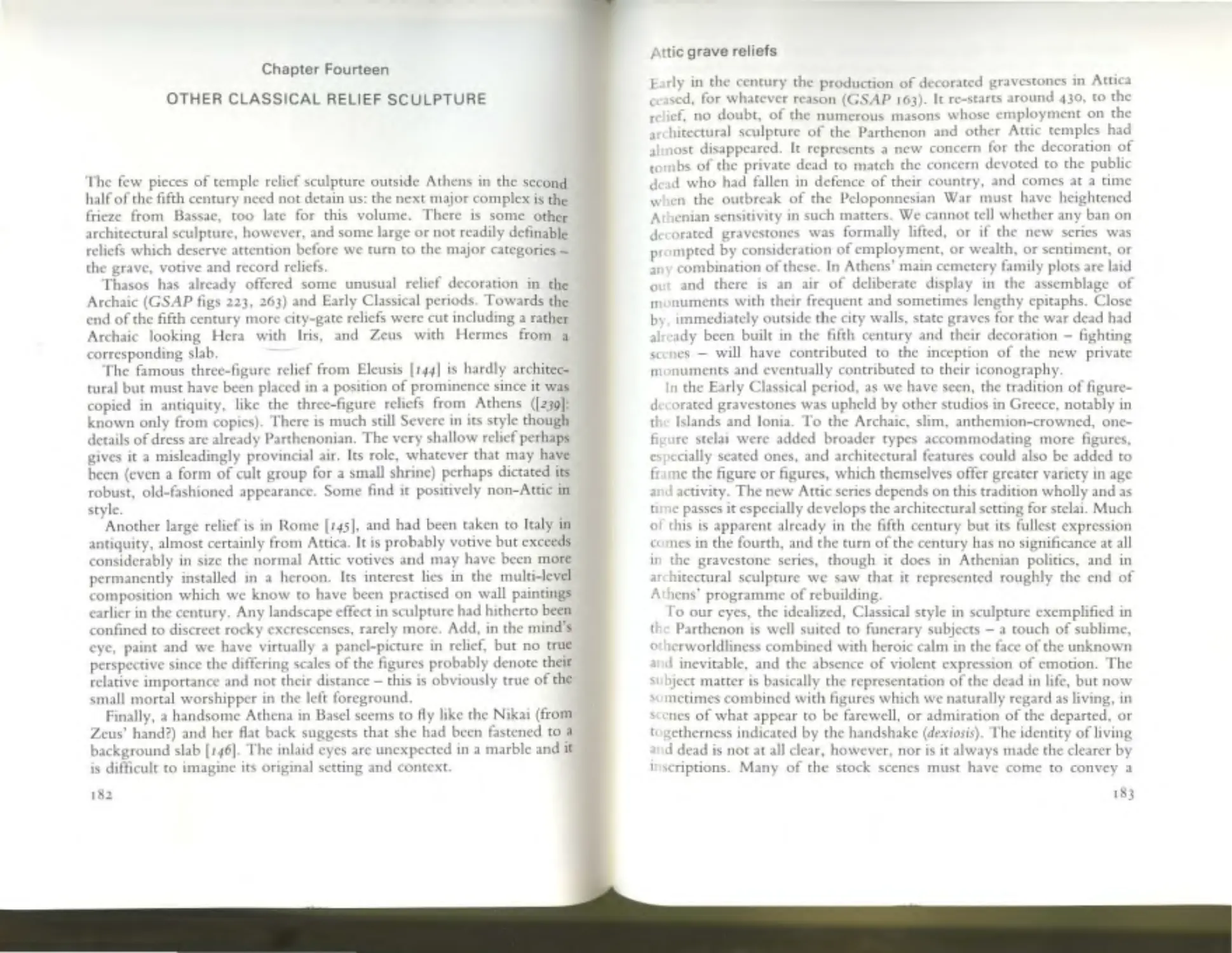

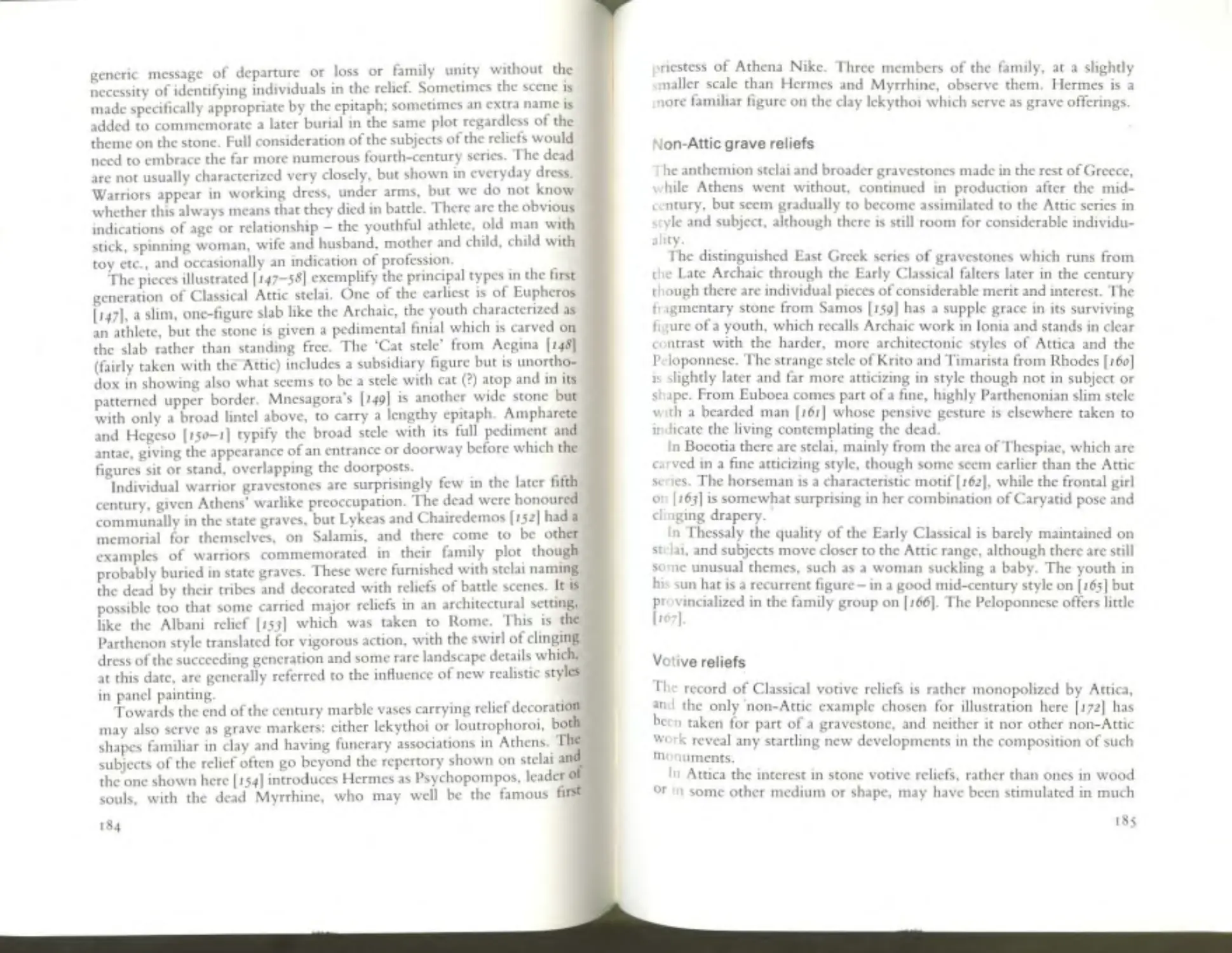

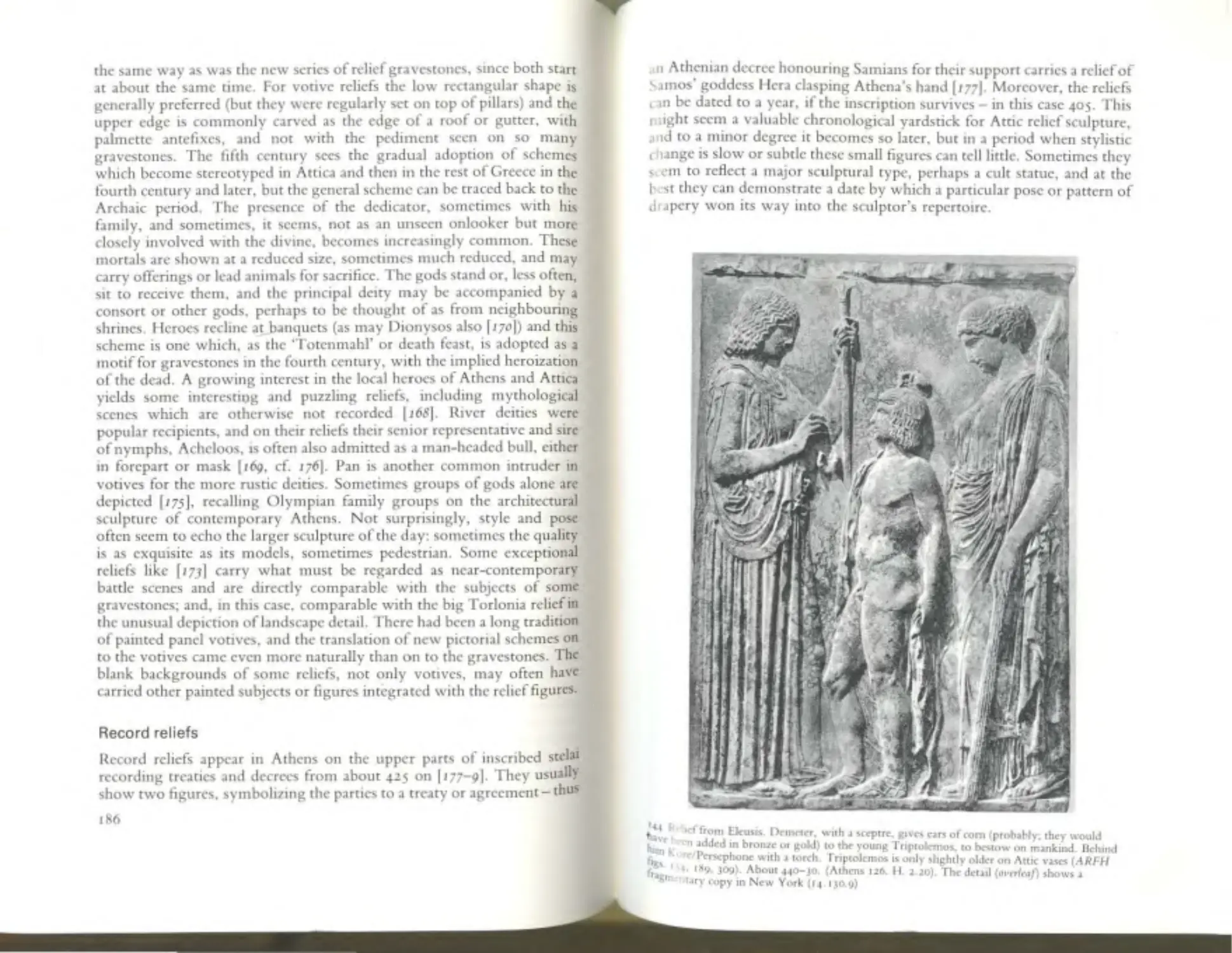

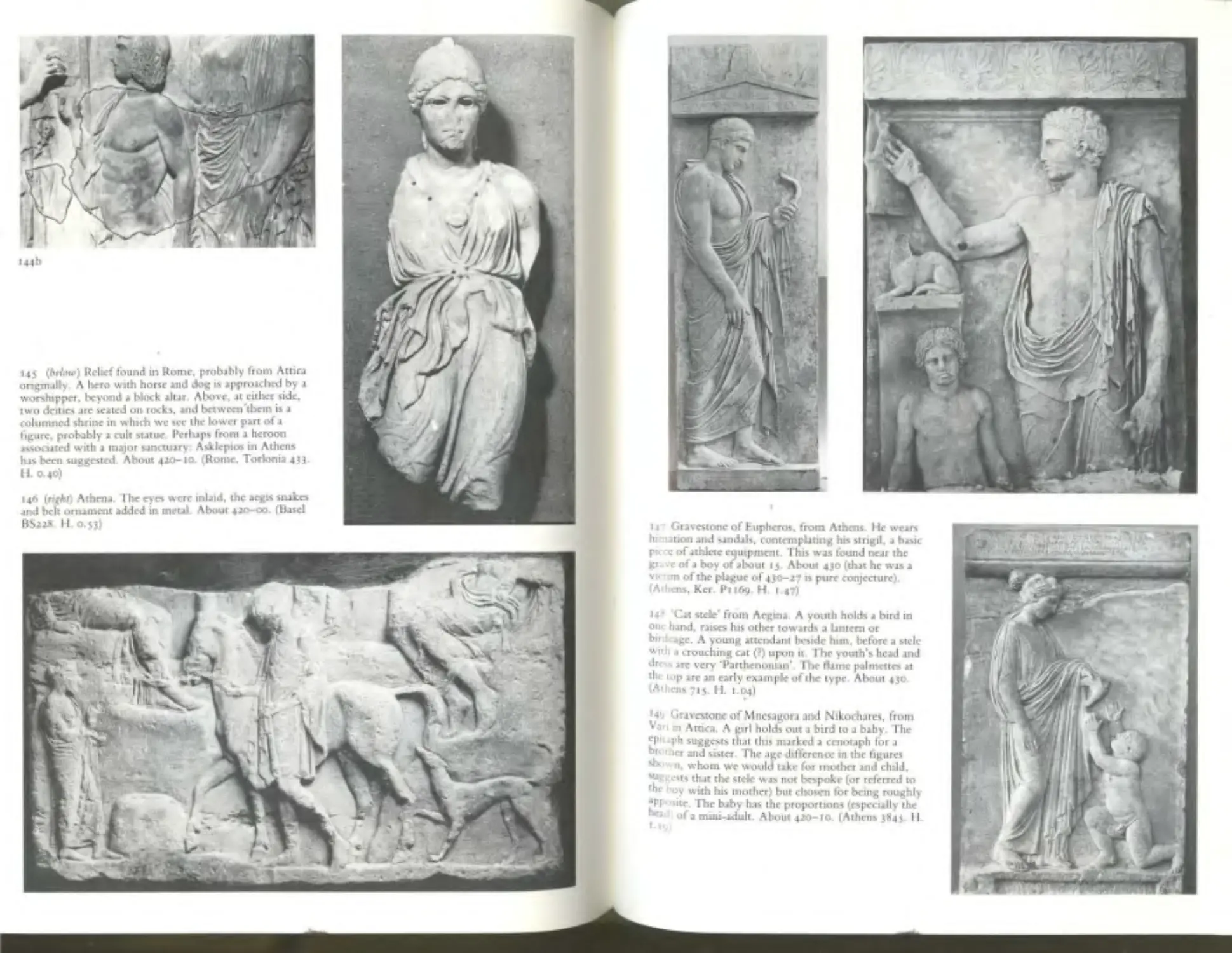

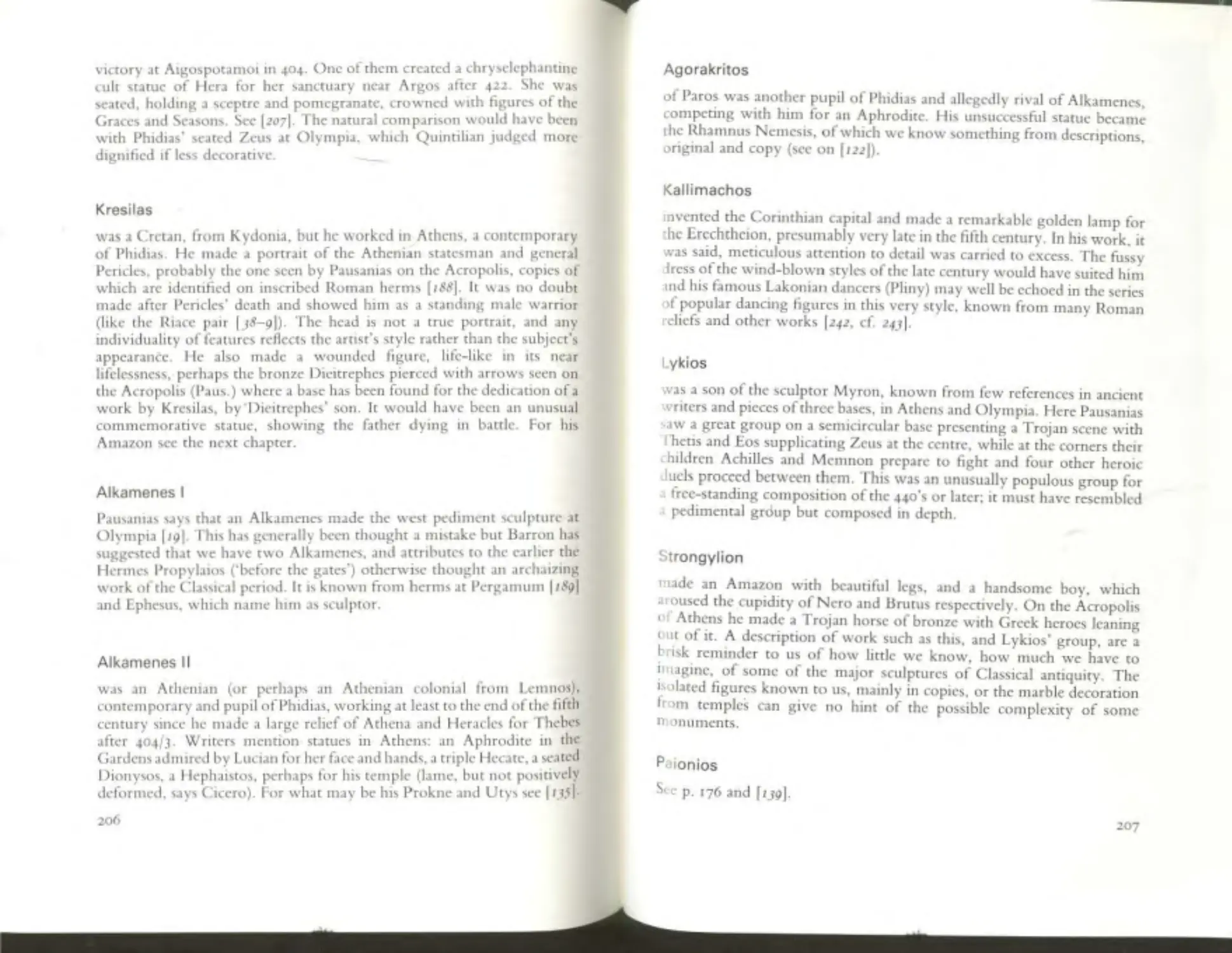

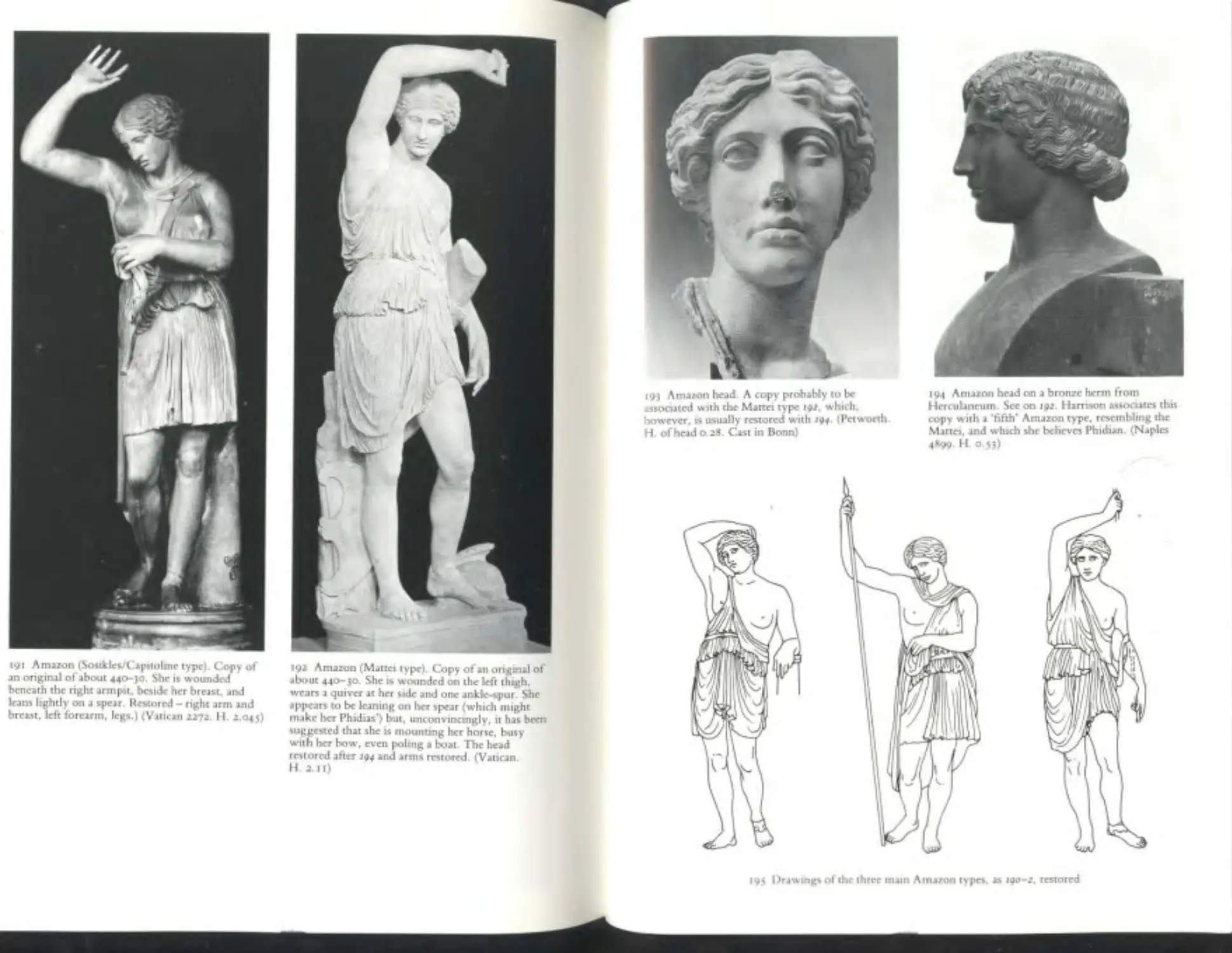

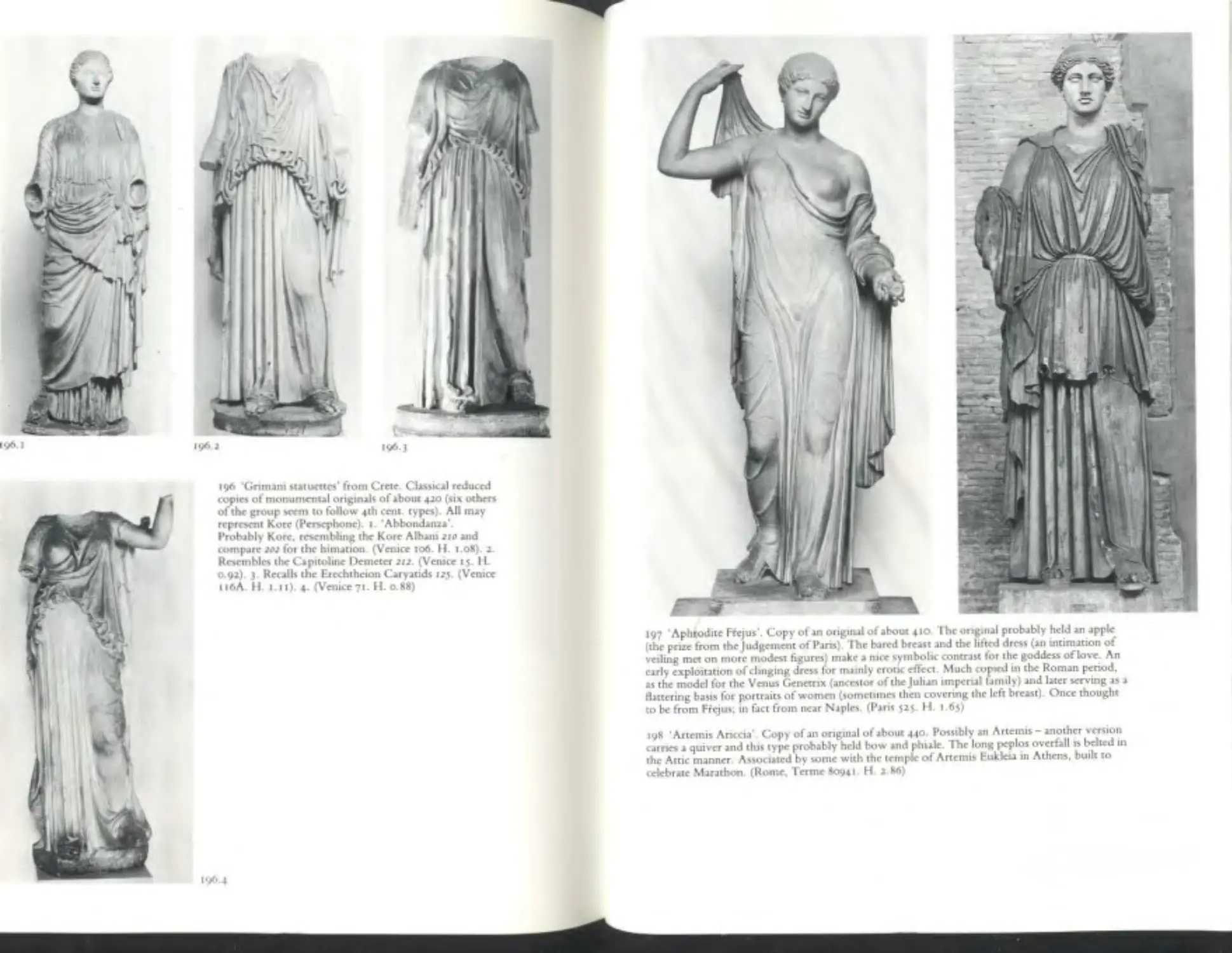

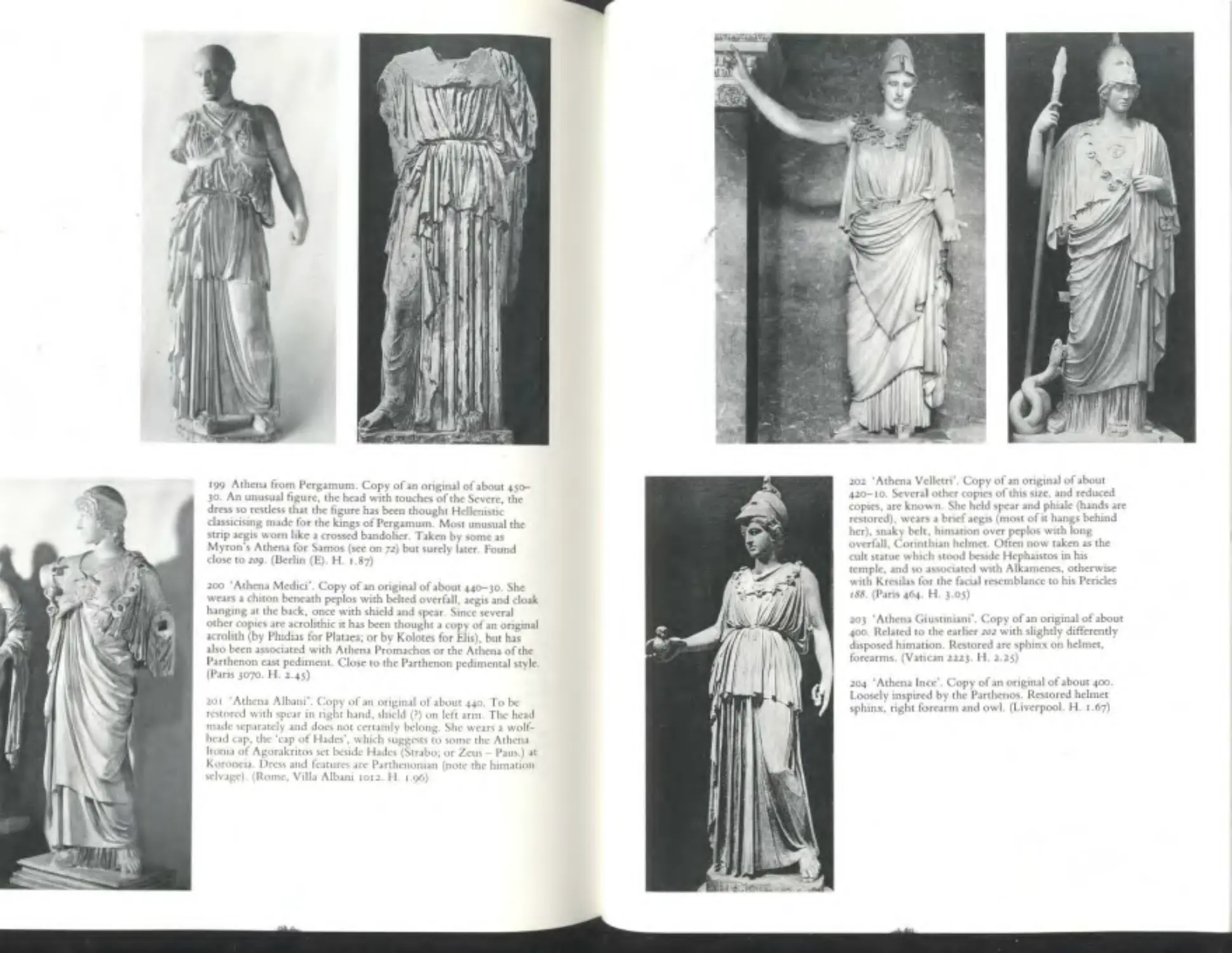

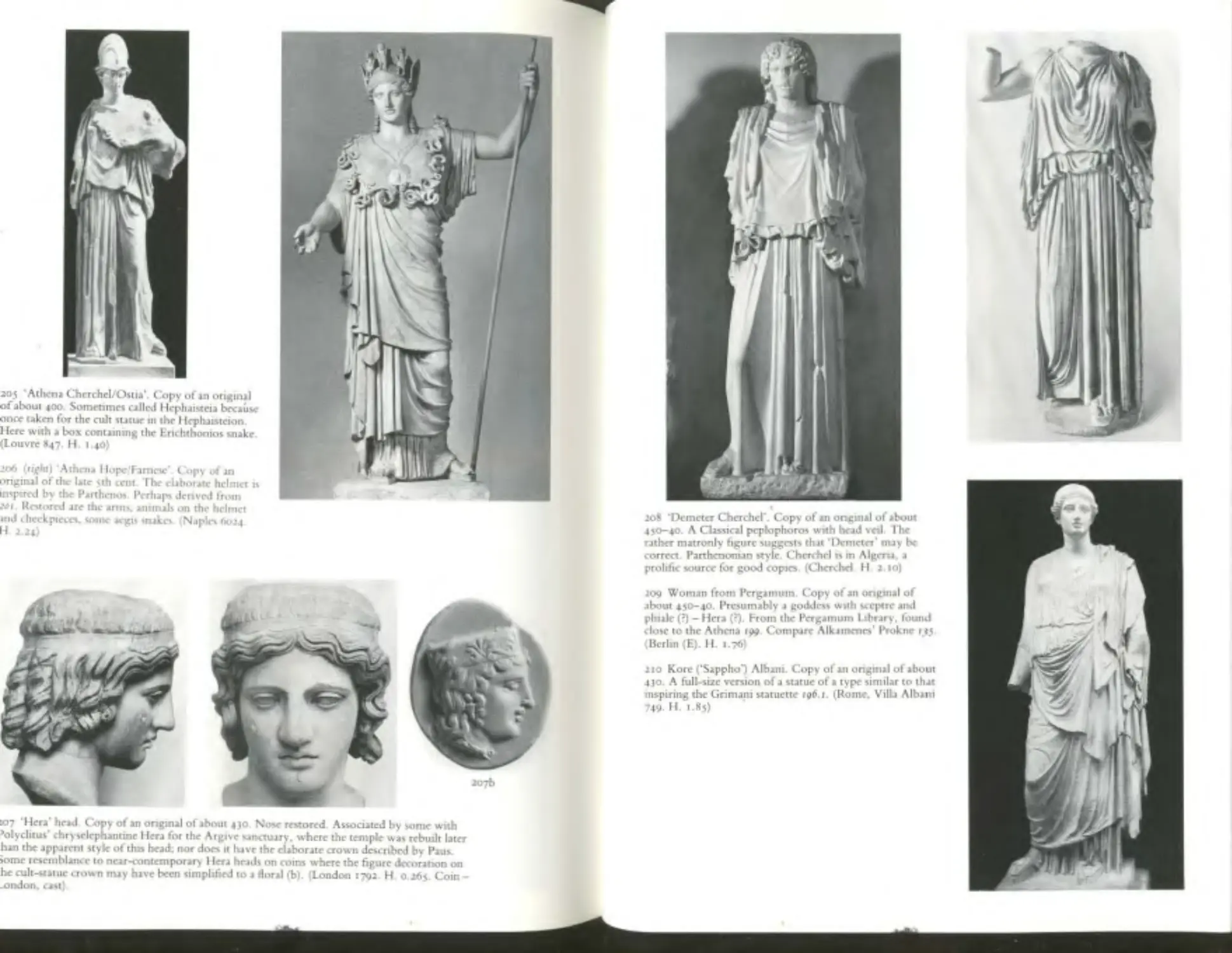

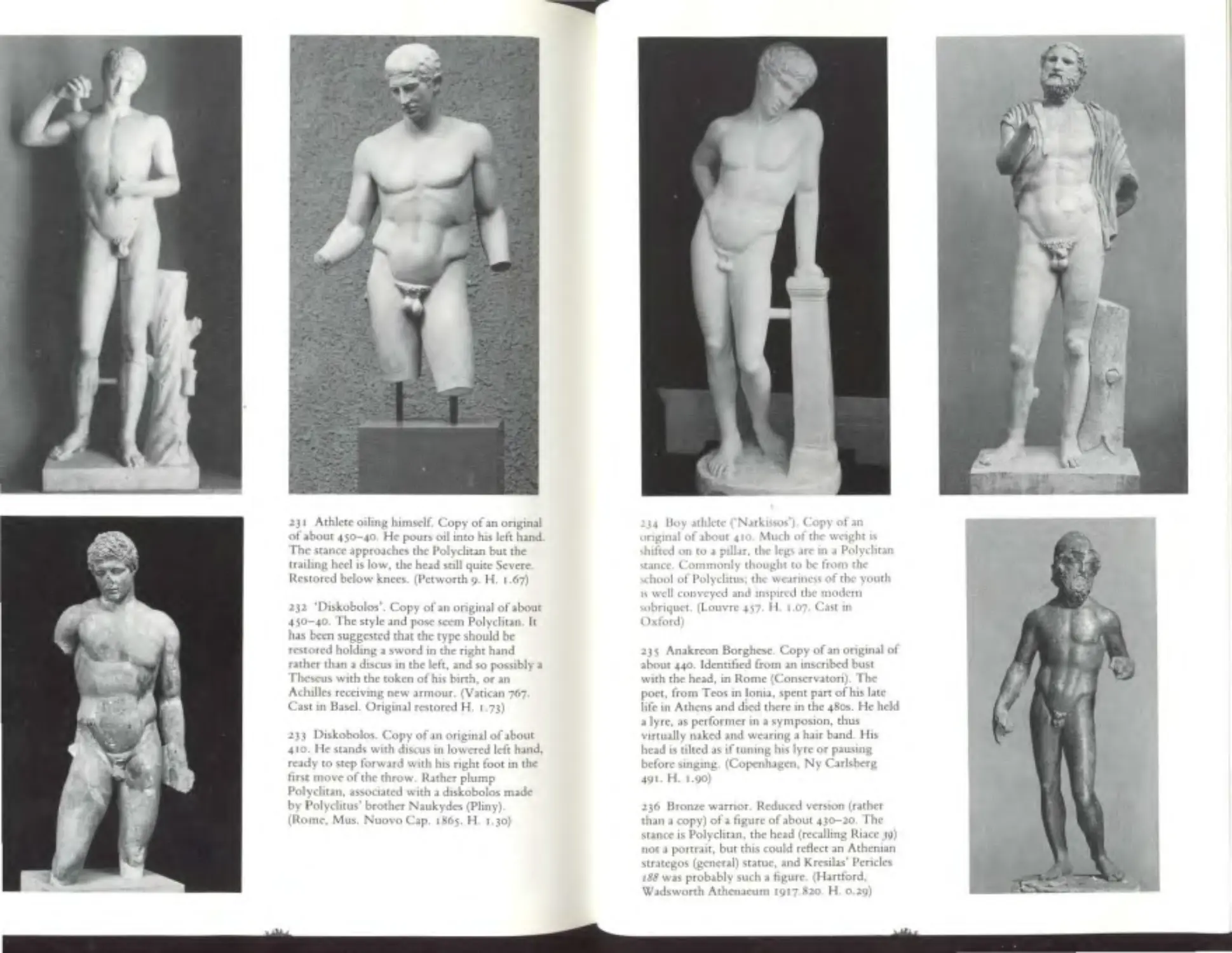

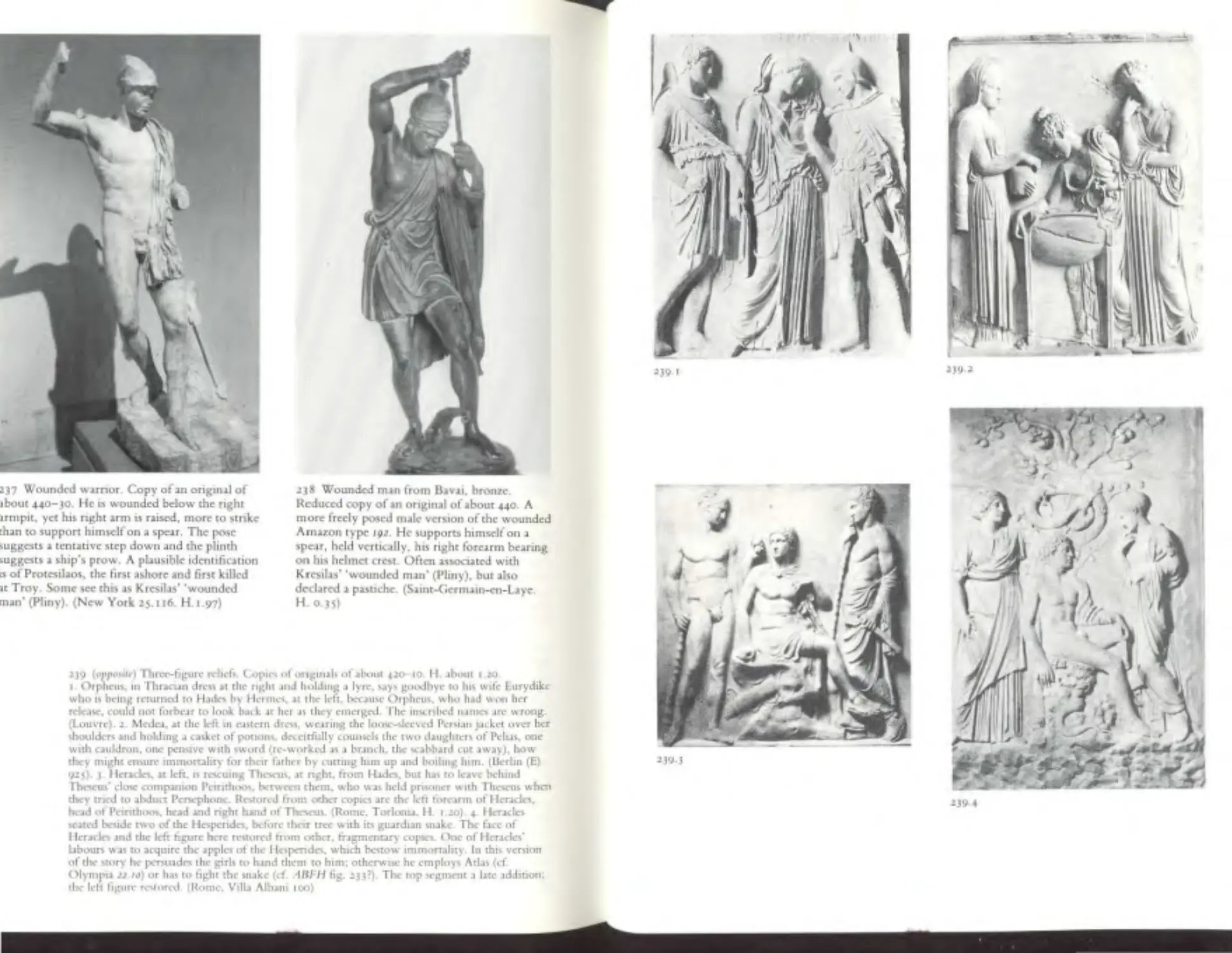

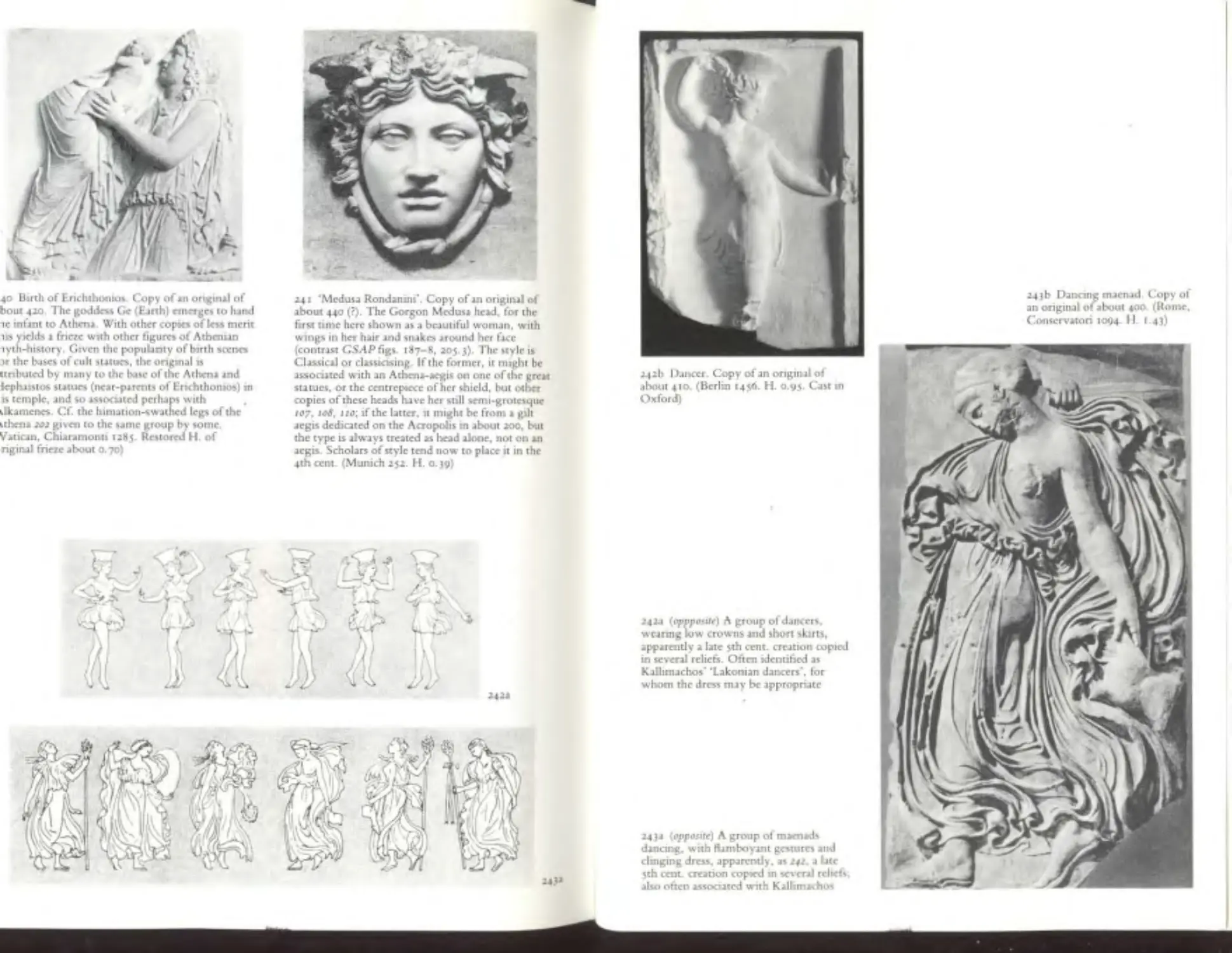

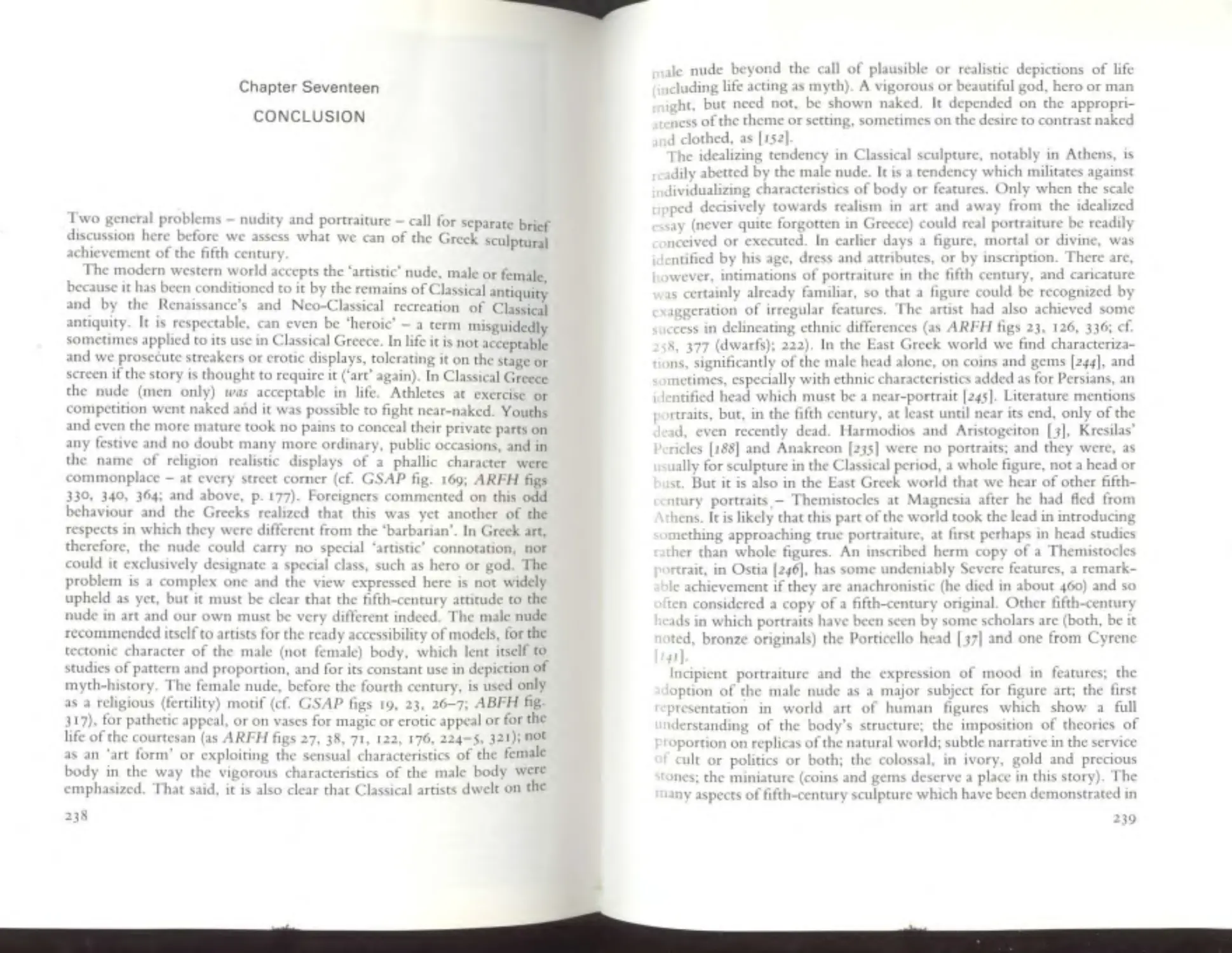

pcdanent on wh ich skill of carv in g and com position alone bid success-